Oxford University Press's Blog, page 418

January 16, 2017

The life and work of J.B.S. Haldane

John Burdon Sanderson (JBS) Haldane (1892-1964) was a leading science popularizer of the twentieth century. Sir Arthur C. Clarke described him as the most brilliant scientific popularizer of his generation. Haldane was a great scientist and polymath who contributed significantly to several sciences although he did not possess an academic degree in any branch of science. He was also a daring experimenter who was his own guinea pig in painful physiological experiments in diving physiology and in testing the effects of inhaling poisonous gases.

JBS was the son of John Scott Haldane, Oxford University physiologist, who trained JBS from childhood in the fundamentals of science. He was educated at Eton and Oxford University, graduating in classics in 1915. His early research was in the physiology of respiration in collaboration with his father. The research career of younger Haldane was interrupted when he joined the Black Watch in the First World War. He was wounded and was sent to India for recuperation at which point he became fascinated by the country and its culture, leading him to spend the last seven years of his life there.

Haldane led a turbulent life. His first marriage to Charlotte Franken, a journalist, involved a sensational divorce and dismissal from Cambridge University, although he was reinstated later. Later he married his young student Helen Spurway. He loved controversies. Some did not serve him well, as in the case involving T. D. Lysenko. Under the influence of Lysenko (and his friend Stalin), the science of genetics was suppressed in the Soviet Union, and Haldane was caught in a dilemma, as a Marxist and as a distinguished geneticist. Haldane’s prevarication highlighted the controversy, which eventually led to Haldane’s decision to move to India.

Before the war, JBS and his sister Naomi bred guinea pigs and mice, leading to the discovery of first case of linkage in vertebrates. After the war, Haldane continued his research in genetics, making important discoveries related to gene mapping, including the first mapping function which led to a more accurate method of gene mapping. His genetic contributions laid the foundation for what came to be known as the Human Genome project.

Marcello Siniscalco (standing) and J.B.S. Haldane in Andra Pradesh, India, 1964 by Dsiniscalco. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Marcello Siniscalco (standing) and J.B.S. Haldane in Andra Pradesh, India, 1964 by Dsiniscalco. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Haldane’s great skill in popularization first became evident with his highly successful Daedalus; or, Science and the Future (1923) which influenced his friend Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. The scientific predictions of Daedalus ranged from production of ectogenic children (‘test-tube’ babies) to possible uses of nuclear energy. Haldane’s Daedalus raised ethical and moral dilemmas resulting from a biological revolution which occupied our attention for decades to come.

From 1924 onwards, Haldane published a series of mathematical papers on Darwinian evolution. This was an evaluation of the process of natural selection in terms of Mendelian genetics. This was considered Haldane’s most outstanding contribution to science. Haldane continued to publish papers in population genetics until his death in 1964. His early work was summarized in his book The Causes of Evolution (1932) which is considered to be one of the foundations of population genetics. Among Haldane’s notable contributions to population genetics are methods for estimating human mutation rates (in relation to hemophilia), and methods for estimating genetic damage resulting from radiation. His work, as well as that of others, has contributed eventually to the banning of open-air testing of nuclear weapons.

Observing the co-occurrence of malaria and the hemoglobin disorders such as sickle cell anemia (as well as thalassemia) in the Mediterranean region, Haldane deduced that this may be due to an interrelationship between malaria and these diseases, quite possibly the carriers of certain forms of these diseases may be more resistant to malarial infection. Later this was shown to be correct by other investigators. Individuals with the heterozygous form of sickle cell anemia were found to be resistant to malarial infection. This work has been extended to the study of genes for immunity in the genome project.

Haldane’s self-experimentation involved the testing of the toxic effects of carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide, and later the diving and inhalation of various gaseous mixtures to escape from submarines under water, which he undertook for the British Navy during World War II. Haldane’s work on the effects of extremes of temperature and pressure while inhaling poisonous gases continued to play an important role in diving and space research.

His legacy is an oeuvre of documents written for academics and for the public. He continued to make significant contributions to scientific research until his death in 1964 in India.

Featured image: Panorama St Mary the Virgin tower by Laemq. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The life and work of J.B.S. Haldane appeared first on OUPblog.

The making of Wells: from Bertie to H. G.

Youthful Bertie Wells was understandably depressed in the depths of winter in early 1888. He had escaped the drudgery of being a draper’s apprentice with a scholarship, only to flunk his second-year university exams and lose his funding to the Normal School of Science in Kensington. He had started to teach science in a provincial school only to suffer another collapse of his health. The diagnosis was suspected tuberculosis, which promised him the prospect of prolonged invalidism at best or an early death at worst. His exasperated mother, the head servant at the large house at Uppark, made it clear that her employer would not always tolerate giving free lodgings to the three feckless Wells brothers. Bertie had nowhere to go.

It is a classic London story: he decided on a last throw of the dice and travelled to the Big Smoke with only £5 from his mother in his pocket. He took an attic room in Theobalds Road, struggled to find work, and was down to his last shilling when he began to pick up piecework in the newspapers, writing paragraphs first for A. V. Jennings, then others. He found a job teaching in Kilburn, crammed for his university re-sits (aiming at the cash prizes for top marks—he won £20), marked piles of essays for the University extension programme, and wrote for the Educational Times. He finally gained his University of London degree from that newfangled college of science.

Within a few months, Wells was set for a life as a London science teacher – a new, strange breed, distrusted by school boards so often stuffed with priests anxious to keep the alarming un-Biblical facts of biology and physics off the curriculum. As a new professional man, pulled up by his own boot-straps, he appeared to fit into the category of one of those precarious petit-bourgeois clerks clamouring for respectability that were so brilliantly lampooned in George and Weedon Grossmith’s The Diary of a Nobody (1892).

We owe Wells’s writing career to another haemorrhage in the lungs, and a long bout of influenza. It was clear he could not survive the physical rigours of being a teacher. While recovering, back with his mother again, he polished an essay and sent it speculatively to a leading monthly journal, far above his station in life. Amazingly, the Fortnightly Review published Wells’s first major essay in 1891, “The Rediscovery of the Unique.” It contained one of Wells’s first wonderfully crystalline images of science, which was also an indication of his early, somewhat impish relationship with the enlightenment it promised:

“Science is a match that man has just got alight. He thought he was in a room—in moments of devotion, a temple—and that his light would be reflected from and display walls inscribed with wonderful secrets and pillars carved with philosophical systems wrought into harmony. It is a curious sensation, now that the preliminary splutter is over and the flame burns up clear, to see his hands lit and just a glimpse of himself and the patch he stands on visible, and around him, in place of all that human comfort and beauty he anticipated—darkness still.”

It reads like a manifesto for the fiction to come, which would use the patterning of light and dark to conjure a melodramatic chiaroscuro. However, when Bertie was invited up to town to meet the editor of the Fortnightly, Frank Harris, it was only to be told his second submission was utterly incomprehensible and could never be published in the journal. He had stumbled again.

The complexity of his personal life was also starting to cause problems. He had married his cousin, Isabel, but found her sexually unresponsive and intellectually incompatible. They agreed to separate when Bertie started a relationship with Amy Robbins (a relationship he lightly fictionalized in his later novel Ann Veronica, much to the disgust of that pathological defender of the private life, Henry James). Wells was living in London but also “living in sin,” with an ex-wife and a mistress to support. They could keep up the veneer of petit-bourgeois respectability for landladies, but it was a precarious business. This was now too risqué to appear in Diary of a Nobody; he had the bohemian life of a somebody, but without much work to show for it.

By 1893, however, Wells was writing regular filler pieces for the Pall Mall Gazette, a liberal evening newspaper, and soon picked up other journalistic work. He stomped the streets like Dickens, looking for inspiration. 1894 was his breakthrough year: he sold seventy-five articles, five stories, and had a serial commissioned by the famous poet and editor, W. E. Henley, who plainly saw something of the coming man in the young author. This serial, tried out in loosely connected pieces for the National Observer in the spring of 1894, turned into The Time Machine, serialized (again by Henley) in the New Review in 1895. It would be the first of four books he published in 1895. W. T. Stead, in the influential Review of Reviews, declared Wells a “man of genius.” Wells earned nearly £800 that year, riches beyond the imagining of a draper’s boy. Bertie Wells had finally become the author “H. G. Wells” at the age of 28.

I am always struck by the disjunction between the cramped, restricted details of Wells’s lower middle-class early life, the son of a useless shop-keeper in Bromley and a harsh Puritan working mother, and the scale of the imaginative leaps he made in the emergent genre he called the “scientific romance” in the 1890s. In a few short years, he consolidated some of the key tropes of the genre that would eventually be called Science Fiction.

Cover, Two Complete Science Adventure Books, Winter 1951. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Cover, Two Complete Science Adventure Books, Winter 1951. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.First, he messed with scale. As Wells revised The Time Machine over seven years, each time he pushed the traveller further into the future, until it was set over eight hundred thousand years ahead, with a further vision of the heat death of the solar system thirty million years hence. A time scale opened by his education in biology under the Darwinian ‘bulldog’ T. H. Huxley in Kensington was combined with a geological and then a truly cosmic temporal schema.

Then, he disturbed perspective. The War of the Worlds (1898) turns on a simple, breathtaking inversion of the telescopic gaze, imagining not us staring out over the solar system, but instead as the meager objects of the ‘envious eyes’ of ‘intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic’ gazing back at us murderously from Mars. The book sets out to dethrone arrogant English mastery at the height of empire. The power of alien swarms was also there in the encounter with the Selenites in The First Men in the Moon (1899).

Here is scale and reversed perspective, but even so the kernel is still in that suburban childhood on the very edges of London. Wells recalled in his autobiography: “I used to walk about Bromley, a small rather undernourished boy, meanly clad and whistling detestably between his teeth, and no one suspected that a phantom staff pranced about me and phantom orderlies galloped at my command, to shift the guns and concentrate the fire on those houses below, to launch the final attack upon yonder distant ridge.” He was blowing up the suburbs and slaughtering his neighbors from a very early age.

He also exploited anxieties about scientific advances. With The Invisible Man (1897) and The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896), Wells updated the secretive, amoral figure of the “mad” man of science, unhinged by ambition. The dreams of Mary Shelley’s Victor Frankenstein, however misguided, partake of the Romantic sublime; they have Promethean grandeur. Wells replaces it with something far grubbier and more compromised: Griffin, the man who discovers invisibility, is a petty surburban moral weakling, irrationally angry, unable to cope, driven by meager vision. The vivisectionist Moreau arrogantly dismisses social niceties to carry on splicing his beasts together in a moral vaccum. Here is the interplay of dark and light represented in his image of the match struck in a darkened temple.

Of course, Wells came to be associated in the twentieth century with writing technocratic utopian visions (as in A Modern Utopia or much later in Things to Come), where the problems of democracy can be overcome by an elite of rational engineers—ideas that have had an ambiguous legacy in the last one hundred years to say the least. But in his first five years as a writer of scientific romances, Wells positively relished exploring the cultural disruptions of science, the delight and terror of ideas that put the category of the human continually into question.

It is Wells’s great strength, but also his limit, that he was always bound by the petit-bourgeois world of his upbringing. For many of his literary contemporaries, the hatred of Wells’s journalistic style and the accusation that he embraced anti-humanistic ideas of “efficiency” and “progress” were also expressions of class disdain. You’d expect the Bloomsbury elite to hate him (Forster and Woolf certainly did). Aldous Huxley called Wells a “horrid vulgar little man.” Even the Communists disliked him for his lack of consistent ideological position: in the 1930s, Christopher Caudwell suggested this was a result of Wells’s petit-bourgeois status, caught between the true agents of history, the workers and the capitalists.

Wells acted for a long time as a punch-bag, a straw man of dreary Edwardianism, against whom the cosmopolitan wonders of Modernism came into sharper focus. Leavis, who did so much to define the idea of the Great Tradition, also routinely dismissed Wells. This was a wrong turn, an unhelpful narrowing of literary taste, done explicitly to preserve an elite. At the seventieth anniversary of his death, in another moment of technoscientific revolution and ideological turbulence, overcoming this erasure and re-discovering Wells has never felt more useful or more urgent.

Featured image credit: “Architecture” by Pexels. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The making of Wells: from Bertie to H. G. appeared first on OUPblog.

Human Trafficking Prevention Month: There are no “teen prostitutes”

January is Human Trafficking Prevention Month, declared each year since 2010 by presidential decree. However, there is still confusion as to what exactly human trafficking is. Despite seven years of raising awareness, on 21st November, the Washington Post published a story with the headline “Two teen prostitutes escaped through a bathroom window, and a sex ring began to unravel.” As noted in a number of comments on the story, as well as pieces afterwards, the girls are not prostitutes. Under the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA), anyone under the age of 18 who exchanges sexual services for anything of value is considered to have been trafficked. Minors are not able to legally consent to selling themselves, meaning there is no such thing as a “teen prostitute” under US law. States have increasingly been passing their own laws to protect children who are sold or traded for sex. Known as “Safe Harbor” laws, these laws prohibit a youth from being charged with prostitution. As of Spring 2016, 19 states and the District of Columbia had these laws in place.

In the TVPA, adults who are survivors of trafficking need to establish that specific means were used to gain control of them – force, fraud, and/or coercion. These means are not necessary to establish trafficking of those under 18. As recognized in the Supreme Court decision related to criminal culpability of those under 18, science is establishing a growing understanding of the decision-making ability of youth. Their brain structure is still evolving and they do not make decisions in the same way as adults. They have more difficulty predicting negative consequences and more difficulty seeing more than one option in a situation. Our collective understanding of this can be seen in state laws that prohibit or limit the number of peers a teenage driver can have in the car.

While there has been an increasing recognition that US residents and citizens can be trafficked, media stories, such as this one, have tended to focus on a single angle: girls who are controlled forcibly by a pimp. This ignores a number of realities related to Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking. Children are sold not only by pimps, but also by gangs or their family. Additionally, a third-party facilitator is not required under the TVPA, and thus when youth trade their bodies for things they want or need, such as shelter or food, this is also trafficking. As noted above, force, fraud, and coercion are not needed for trafficking of children and many of those who are trafficked do not see themselves as experiencing any of these. They often believe they are financially contributing to their boyfriend, gang, or family. If an attempt is made to “rescue” them, they will rebuff it because they do not believe they need to be rescued.

So what can be done to fight this crime? Raising awareness is necessary, but not sufficient. As well as a number of events that will be occurring around the country to raise awareness, there are a number of things that the everyday citizen can do. You can work to support existing organizations that are already doing good work. Activists urge you not to start your own agency as that creates competition for resources. Rather, focus on your skill set to do such things as serve as a mentor to an at-risk youth, tutor at a school, raise money for an organization, or be a foster parent. These groups of youth are at particular risk for being trafficked and knowing that someone cares about them can be the critical factor to helping to prevent trafficking.

Featured image credit: sad depressed by Unsplash. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Human Trafficking Prevention Month: There are no “teen prostitutes” appeared first on OUPblog.

The Fourth Communique: How President Reagan’s six assurances continue to shape US-Taiwan relations

When asked to describe the foundations of, many experts dutifully point to the three Joint Communiques of 1972, 1978, and 1982 and the Taiwan Relations Act of 1979 (TRA). Often overlooked are President Reagan’s Six Assurances to Taiwan, which were issued to the Republic of China (ROC) on Taiwan shortly after the Third Communique with China became public in 1982.

More than a diplomatic side note, the Six Assurances have proven to be an enduring and authoritative feature of US policy over the past 34 years. Under the Trump administration, they are likely to play a starring role in the triangular US-Taiwan-China relationship.

The Third Communique of 17 August, 1982 stated, among other things, that the United States did not seek to carry out a long-term policy of arms sales to Taiwan. The purpose was to appease Chinese leaders who complained the TRA had undermined the first two Communiques of 1972 and 1978.

The Third Communique met with instant condemnation from the ROC and members of Congress who feared Reagan was walking away from the TRA’s policy of safeguarding Taiwan’s security. The Senate immediately called hearings to investigate the constitutionality of the Third Communique. The TRA, as the law of the land, prevails over the Joint Communiques as a matter of US constitutional law. President Reagan receiving the tower commission report in the Cabinet Room, 1987 via Wikipedia.

President Reagan receiving the tower commission report in the Cabinet Room, 1987 via Wikipedia.

To assuage these concerns, President Reagan issued an unsigned memorandum to President Chiang Ching-kuo of Taiwan which stated:

“In negotiating the third Joint Communiqué with the PRC, the United States:

Has not agreed to set a date for ending arms sales to Taiwan;

Has not agreed to hold prior consultations with the PRC on arms sales to Taiwan;

Will not play any mediation role between Taipei and Beijing;

Has not agreed to revise the Taiwan Relations Act;

Has not altered its position regarding sovereignty over Taiwan;

Will not exert pressure on Taiwan to negotiate with the PRC.”

In a separate, secret memorandum, President Reagan wrote that “it is essential that the quantity and quality of the arms provided Taiwan be conditioned entirely on the threat posed by the PRC.”

As I explained on the OUPblog recently, Taiwan’s statehood has evolved through four distinctive stages from 1895 to the present, the most important and recent of which began in 1988. Under President Lee Teng-hui, a native born Taiwanese, Taiwan embarked on a profound political transformation and a process of democratization—and Taiwanization. As a result, Taiwan’s status under international law has evolved from that of a militarily occupied territory to an independent, democratic, peace-loving, and sovereign state.

From 1949 to 1987, Taiwan was living under authoritarian rule of martial law by the Kuomintang (KMT). Taiwan’s democracy movement did not take wing until six years after the issuance of the Third Communique and the Six Assurances, nine years after the adoption of the TRA and the de-recognition of the ROC, and 16 years after President Nixon articulated the One China Policy, under which the United States acknowledged, but did not recognize or endorse, China’s claim that Taiwan was a part of China.

Taiwan flag by Etereuti. CC0 Public Domain by Pixabay.

Taiwan flag by Etereuti. CC0 Public Domain by Pixabay.The foundations of the US-Taiwan-China relationship were laid before the end of the Cold War, before the Tiananmen Square massacre, before Taiwan’s Sunflower Movement of 2014, and before the historic landslide election of President Tsai Ing-wen of the pro-Taiwan independence Democratic Progressive Party (DPP).

To say that the One China Policy is outdated is a gross understatement.

The Six Assurances have been reaffirmed by each successive presidential administration and were reaffirmed by Congress as recently as May 2016. The Republican Party platform also reaffirms the Six Assurances and the TRA as the basis for US-Taiwan relations.

President-elect Trump made headlines on 2 December when he received a congratulatory telephone call from Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen. In response to his critics, Mr. Trump tweeted that he saw nothing wrong with accepting a call from the leader of a nation that purchases U.S. arms and that he would not seek China’s permission to do so.

The Trump-Tsai phone raised eyebrows. But in some respects, Mr. Trump is simply echoing the fundamental message of Regan’s Six Assurances: the United States is free to conduct its relations with Taiwan by its own terms and cannot be dictated to by China.

This common sense approach may finally open the door to reappraising the outmoded One China Policy or other aspects of US policy toward Taiwan and China.

Featured image credit: Taiwan by Falco. CCO Public Domain by Pixabay.

The post The Fourth Communique: How President Reagan’s six assurances continue to shape US-Taiwan relations appeared first on OUPblog.

January 15, 2017

Bugs in space! Using microgravity to understand how bacteria can cause disease

Space may be the final frontier, but it’s not beyond the reach of today’s biologists. Scientists in all areas of biology, from tissue engineering to infectious diseases, have been using the extreme environment of space to investigate phenomena not seen on Earth. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) has conducted research in the life sciences for almost 50 years. Some of this research relates directly to human space exploration, while other projects investigate broader scientific questions related to human health and disease.

In the early 1990s, NASA started flying living cells on their space shuttles to investigate how cells respond to the rigors of spaceflight. Several different types of human cells were flown in space, with each showing various changes in size, shape, growth rate, and other behaviors. At the same time, NASA built a vessel capable of mimicking the microgravity environment of space. While not able to fully recapitulate all the environmental changes brought on by spaceflight, the rotating wall vessel (RWV) provides an environment of low-shear modelled microgravity (LSMMG), which is sufficient to induce many of the changes seen in space.

The RWV was originally designed to help researchers grow cells in three-dimensions. When human cells are grown in the laboratory under normal conditions, they form a flat sheet, with no overt structure. In contrast, cells grown in the RWV come together to form mini-organs or organoids, with similarities to normal human tissue. Organoids have been created for several human tissues, including lung and bladder, although gut organoids are the most advanced. Organoid models have many uses in research, from understanding basic cellular interactions to investigating drug toxicity and infection.

The techniques and equipment developed for the study of human cells in space have been used by microbiologists to study the impact of spaceflight and microgravity on bacteria and fungi. In early spaceflight experiments, researchers examined the effect of low gravity on common laboratory bacteria. Surprisingly, there was a trend towards increased growth rate and resistance to stress in bacteria grown in space. While researchers couldn’t determine how the bacteria were able to sense gravity, their ability to do so opened up a new field of bacterial research.

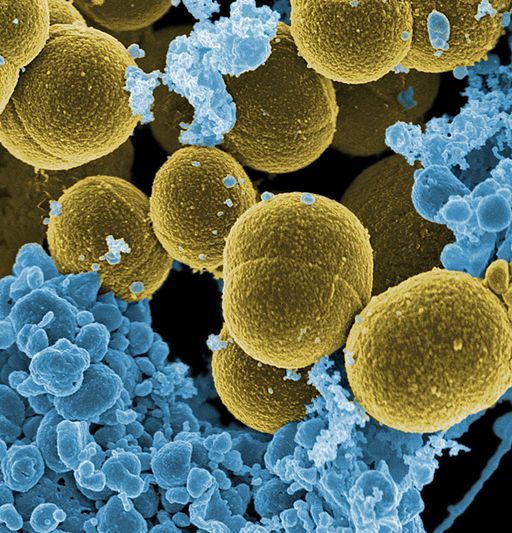

Stapylococcus aureus bacteria escape by National Institutes of Health. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Stapylococcus aureus bacteria escape by National Institutes of Health. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Over the following years, these experiments were repeated with some important findings. Two different bacterial species often associated with hospital-acquired infections, Staphylococcus aureus (Golden Staph) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, showed an increased ability to persist as a biofilm after growth in LSMMG. Biofilms are slime-like masses of bacteria that adhere to surfaces and protect the bacteria from external pressures such as disinfectants, manual cleaning, and desiccation. Biofilms are especially important in the hospital setting, where bacterial persistence can be problematic. S. aureus grown in LSMMG also showed increased resistance to antibiotics.

Even more intriguing were the spaceflight experiments completed using the gastroenteritis-causing bacterium Salmonella. In two separate experiments, researchers showed Salmonella grown in LSMMG or in space were more deadly in mice than bacteria grown on Earth. These bacteria were not only able to sense the change in gravity, but changed their behavior to become more lethal. It’s unclear why bacteria have evolved this mechanism. However, some researchers have suggested that within the intestines, there is an area close to the microvilli that displays microgravity-like low shear. As this is also where Salmonella likes to invade their host, it is possible the bacteria use this microgravity-sensing ability to determine the correct moment to attack.

Various studies have shown the utility of spaceflight research in understanding the world we live in, and the unforeseen advances that can be made by utilizing space technology in biological research. While on the face of it, this research may seem obtuse, learning how and why cells respond to microgravity may lead to better therapeutics and preventatives for important diseases.

Featured image credit: Cosmos by insspirito. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Bugs in space! Using microgravity to understand how bacteria can cause disease appeared first on OUPblog.

Has India seen a foreign policy reset under Narendra Modi?

In late 2016 and early 2017, as policymakers and analysts have scrambled to predict the great unknown of Donald Trump’s foreign policy pathway for the United States, it is worth remembering that some 20 months ago, India too confronted a seismic shift in leadership, and a faced a future of significant foreign policy uncertainty.

Narendra Modi rose to the Indian premiership in May 2014. Like Trump, Modi fits within an emerging global trend of ‘strong’ leaders with hyper-nationalist agendas, including Xi Jinping, Vladimir Putin, and Recep Erdoğan. Upon election, Modi’s image was one of an unpredictable and controversial premier who many thought would substantially change the direction of India’s foreign policy.

Modi’s ascent to power also saw the first parliamentary majority achieved by a single party in India since 1984. That party—the Bharatiya Janata Party—was the same Hindu nationalist party that led the country in a multi-party alliance from 1998 to 2004, and presided both over India’s highly controversial nuclear tests, and two significant crises between India and Pakistan.

In the same way that analysts and politicians have sought to compute what a Trump presidency will mean for the future of world politics, from 2014 India watchers have wondered how Modi and his party’s leadership will impact the direction of India’s foreign policy in Asia and beyond. It seemed that the mandate bestowed by Modi’s party majority would position him as a powerful national leader with both the authority and the public support to instigate far-reaching foreign policy changes.

One prominent line of thinking in the Indian media was that Modi would emerge as a foreign policy pragmatist, discarding India’s principled policies of the past as well as his own Hindutva or Hindu nationalist beliefs. His ‘single-mindedness’ and ‘CEO persona’, which led to the rapid economic transformation of the state of Gujarat during his tenure as chief minister, would likely transform India. India under Modi would take a tougher stance against its long-time regional rivals Pakistan and China. At the same time, his Hindu nationalist beliefs would not substantially, if at all, affect his governance, particularly in matters of foreign policy.

Twenty months on from such predictions, what has become clear is that entrenched foreign policy ideas and ideologies within India limit what an individual leader—even a leader as driven, willful, and influential as Narendra Modi—can achieve in seeking to transform India’s foreign policy.

A number of factors constrain Modi’s ability to bring about drastic shifts in Indian foreign policy. Some of these operate at the domestic level: the obduracy India’s foreign policy establishment, plodding political decision-making processes, and unresolved state weaknesses that stem from India’s internal political challenges. Others operate at the international level: India’s troubled neighbourhood, a long-standing rivalry with China, and the need to retain and enhance India’s soft power.

But there is also a constraint that has been a constant in Indian foreign policy—enduring sets of ideas. Defying the prediction that his pragmatism would lead him to dispense with the ideas of the past, instead, like other Indian leaders, Modi has had to take entrenched frameworks of foreign policy ideas seriously, even in policy initiatives that seem to break with the past.

The Prime Minister, Shri Narendra Modi addressing the 12th ASEAN-India Summit, in Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar on November 12, 2014 by narendramodiofficial. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The Prime Minister, Shri Narendra Modi addressing the 12th ASEAN-India Summit, in Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar on November 12, 2014 by narendramodiofficial. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Two cases of apparently ‘transformational’ policy stand out. First, the settlement of the India-Bangladesh territorial dispute through the swapping of enclaves with Bangladesh in August 2015 was seen as a major break with the past. Indian leaders have long held firm to a strict concept of the inviolability of India’s borders. However, they did not suddenly become receptive to the loss of territory or cease to have emotive ideas about the ceding of territory through the exchange of enclaves.

Instead, to deflect from criticism that India was ceding territory and to win over opponents to the settlement, Modi focused political attention on the strengthening of the border that his government argued would result from the land boundary agreement, ironically, because of the physical loss of the haphazard pockets of land that Bangladesh and India have each held within one another’s territories. In doing so, Modi accepted the longstanding principle that India’s territory should be inviolable, but also appealed to the Hindu religious nationalism of his domestic political base by linking the border settlement to a crackdown on illegal Muslim immigration.

Second, in establishing an International Day of Yoga (IDY) through the United Nations, and then creating a national and international public spectacle out of the first ever such celebration in June 2015, the Modi government again appeared to have made a break from the past. While past Indian premiers are no strangers to the endorsement of yoga, Modi switched gear to champion yoga as one of India’s signature cultural exports. In doing so, he appeared, to some, to be promoting a version of yoga that privileged a narrow, ‘Hinduised’ interpretation of India’s cultural traditions. This move appeared to disregard longstanding, institutionalised ideas about the value and appeal of India’s syncretic cultural heritage. Yet when the Modi government faced accusations that its aggressive and narrow brand of yoga promotion was belying India’s longstanding secular and pluralist identity, it was forced to re-calibrate its approach. India’s ministry for yoga and traditional medicines attempted to avoid—if not include—explicitly excluding India’s religious minorities from India’s first celebration of the IDY.

Far from being a leader who could dispense entirely with frameworks of foreign policy ideas, in both cases, Modi’s innovative policy successes were dependent on taking institutionalised policy frameworks seriously, but also on appealing to his Hindu nationalist base of political support.

Overall, India’s supposed ‘foreign policy transformation’ under Modi has a narrow space in which to operate. While Modi may have the personal drive to effect changes, and while these changes may lead to some transformative policy successes, his role at the helm of India’s foreign policy is less original and ground breaking than some commentators have supposed.

Ultimately, Modi must bring some change to please his domestic political supporters, but the degree or extent of change is limited by India’s institutionalised foreign policy ideas. Those fearful of, or hopeful for, the rise of strong leaders around the globe today and their capacity for radical shifts may find that ideas matter, and that change will be more muted than many suppose.

Featured image credit: Delhi India Government by Laurie Jones. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Has India seen a foreign policy reset under Narendra Modi? appeared first on OUPblog.

January 14, 2017

International scientific collaboration in an ever-changing world

It is a widely held perception that the United States and United Kingdom, leading nations in the field of science, synergistically combine scientific excellence with ready entry into international networks of scientific collaboration. However, both nations experienced important changes in 2016: the United Kingdom voted to separate from the European Union and the United States elected a controversial president. In this context, an important question about scientific mobility and international collaboration arises: how do fundamental changes in the essence of the two most important scientific players affect international science?

Brexit

UK-based researchers collaborate with partners all over the world. In the United Kingdom, 28% of academics are from other countries, with 16% from other EU countries. In a statement on international collaboration post-EU referendum, the Research Councils of the United Kingdom affirmed that they are “working with their research communities and with Government to ensure that the UK is well placed to maintain its place as a leading research nation”. It is unlikely that Brexit will significantly impact non-EU collaborations. As for the UK-EU collaborations, Brexit has implications on two main fronts, as elucidated by Eleanor Beal, senior policy advisor of the Royal Society. First, she points out that any changes to immigration policies will determine who can visit or work in the United Kingdom as well as how easily UK researchers can travel to the rest of the EU. Second, the mechanisms by which the United Kingdom engages with EU research programmes will determine whether scientists based there can access the support for collaboration and mobility that the EU provides. Immigration has in fact emerged as a central issue in the wider debate about what Brexit will look like in practice. For instance, it will clearly be more difficult for principal investigators to hire staff members from other EU countries without having to sponsor their visas. In this scenario, it is unclear to what extent Brexit will impact the UK profile of international collaboration, but it seems unquestionable that some negative impact will be observed.

Lab students at Saint Petersberg State Polytechnic University by A.I. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Lab students at Saint Petersberg State Polytechnic University by A.I. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.United States presidential election

Donald Trump’s election as president of the United States can have a broader impact on international mobility and scientific collaborations. In a recent interview to Scientific American, Trump declared that if the United States “allow individuals in this country legally to get their educations, we should let them stay if they want to contribute to our economy. It makes no sense to kick them out of the country right after they achieve such extraordinary goals”. However, Trump’s constant demonstration of xenophobia will likely give foreign scientists pause for thought before they consider a move to the United States, as written by Mark Peplow for Chemistry World. It is important to remind us all that the scientific work force in the United States is greatly dependent on the recruitment of international personnel and, as stated by Cassidy Sugimoto, US Nobel prizes and other great discoveries made in the United States are largely attributed to scientists both born and educated in other nations. If US policies inhibit the country’s connectivity at the global level, the scientific strength of the United States will likely decline.

Underdeveloped nations

What about the impact of restricting international mobility on developing and underdeveloped nations? Using the Brazilian scientific system as an example, it is predictable that the negative impact could be substantial. Recently, Brazil launched a huge program to send scientists to be trained abroad. The impact of this initiative on Brazilian science still has not been determined, but the current local perception is that international experiences and/or collaborations are indispensable for young scientists to succeed even in job applications within the Brazilian academic system. Brexit will likely have little impact on the collaborative actions between Brazilian and British scientists, but restrictive immigration policies could profoundly affect training of Brazilian researchers in the United States and, consequently, limit the establishment of intercontinental collaborations. The Brazilian case is an example that can be extrapolated to other countries with a long history of sending scientists to be trained abroad, including India and China.

In an integrated and ever-changing world, policies of leading nations directly affect multiple countries in many aspects. However, it is important that the scientific community stands together to constantly make sure that country boundary lines cannot limit science.

Featured image credit: Handshake by viganhajdari. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post International scientific collaboration in an ever-changing world appeared first on OUPblog.

India: a work in progress

Every country that is on the ascendant feels the need for a “coming out” party. In the last half century, that need has been met most often by hosting the Olympic Games. Japan did it in 1964, South Korea followed in 1988, and China in 2008. The Olympic itch seems to come in the wake of economic growth that takes per capita income to the vicinity of $6,000—as was the case with Japan and China when they played host, and not far off the mark for Korea. It was true for the Soviet Union (which hosted the 1980 Games) as well. Only Mexico among the emerging markets was ahead of the curve; its per capita income at the time of the 1968 Games was barely $4,000. Sometimes, the Olympics were not a stand-alone showpiece project. Japan timed the launch of its Shinkansen bullet trains for the Tokyo Olympics and China started its high-speed trains a year ahead of the Beijing Olympics.

India’s per capita income, calculated on the same basis, was $3,372 in 2009–2010 and can be expected to get to the $6,000 mark before too long. The itch for showpiece projects like high-speed trains is already evident in India; one has been proposed, to link Mumbai and Ahmedabad. It’s a fair bet that if the economy fares well over the next few years, whichever government is in office in 2019 will feel compelled to bid for the Olympic Games of 2028; by then some high-speed trains should be up and running. That will be presented as a statement of India’s “arrival”—and serve also to bury memories of the scandal-scarred Commonwealth Games of 2010 in Delhi.

It’s a fair bet that if the economy fares well over the next few years, whichever government is in office in 2019 will feel compelled to bid for the Olympic Games of 2028

But long before any Olympics, a country on the ascendant should see a hundred flowers bloom—entrepreneurs flourish; audiences and markets grow for film and music, sports, art, and books; and the country attempt a more ambitious external outreach. The Jaipur Literary Festival began in 2006 and now attracts audiences from across the country and authors from around the world. At least a dozen other cities now hold annual literary festivals. The print runs for books are small by global standards, but their growth has been explosive. The popular storyteller Chetan Bhagat has reportedly sold 2 million copies of his latest novel, Half Girlfriend. Self-help books and romance novels have sustained sales in the hundreds of thousands, while non-fiction “bestsellers” are expected to sell not 10,000 copies as of old, but multiples of that number. India is now the third-largest market for books in English; by one estimate, 90,000 titles are published annually.

The art market is thinner but also buoyant, with sales by art galleries and auction houses reflecting growing interest and fetching much better prices than in the past. The highest price at a Mumbai art auction in the late 1980s was a record Rs 1 million for an M. F. Husain (about $65,000 at the time); against that, Christie’s two auctions in Mumbai in 2013 and 2014 fetched $2.8 million for a Tyeb Mehta and $3.7 million for a V.S. Gaitonde, with combined sales of all works sold topping $27 million. The growth of professional sports is another marker. Indian cricket’s governing board has become the game’s financial powerhouse; domestic professional leagues exist now in hockey and football (soccer) as well as the homegrown kabaddi, once a strictly rural sport with no urban following. Private ownership of newly formed clubs and teams and the support of satellite television have made the difference. The inaugural year of the kabaddi league delivered a viewership of over 400 million, not too far behind that for the mega-sports event, the Indian Premier League (involving privately owned teams that play 20-over cricket).

Then there is the flowering of entrepreneurial talent—not just the emergence of e-commerce poster boys like Flipkart (touted as India’s answer to Amazon), its rival Snapdeal, the mobile ad player InMobi (funded by SoftBank and others), and online furniture businesses like Urban Ladder (supported by Ratan Tata) and Pepperfry, but also scores of others. The rush of investor money into these and other firms has produced instant wealth for the founders, but with suggestions of a pricing bubble; the homegrown cell phone marketer Micromax promised extra-long battery backup and quickly became the second-largest vendor in a booming market. The company, dependent on imports from China and Taiwan, has started local assembly and exports to Russia. Business newspapers devote special pages to start-ups, and one has announced a set of annual awards in the category. Bengaluru’s residents used to take pride in being a tech city; they now talk of its start-up culture—the city is said to attract 30% of the total angel investment in the country.

A confident indigenous ethos shows in films and popular music groups too—though the money outside of mainstream commercial cinema is still very limited. Citizen engagement reflects in the growth of civil society activism as large numbers of youngsters commit to careers in non-profit, public-interest activities. The millennial generation’s attitudes are noticeably different and more freewheeling, compared to the safety-first approach of the country’s post-colonial generation, with its focus on conventional careers and traditional family values. Nielsen’s consumer confidence surveys (which track the mood with regard to jobs, spending intentions, and changing habits) consistently show that Indians with access to the Internet are the most optimistic in the world; except for the first quarter of 2009, the country has never ceased to be optimistic since the tracking began in 2005. The optimism rides high even when half the respondents think the economy is in a recession!

The problem with defining the emerging India by using these parameters, however indicative they may be of the direction of change, is that the country does not offer a neat narrative about bullet trains and the Olympics

The problem with defining the emerging India by using these parameters, however indicative they may be of the direction of change, is that the country does not offer a neat narrative about bullet trains and the Olympics—not when large numbers of people travel by train in Bihar by squatting on the roofs of overcrowded coaches; and not when the average speed of a goods train has remained static at 25 kilometers per hour for decades. The fact is that you can still approach the India story from fifteen different angles and get multiples of that many different narratives.

Markets for consumer goods are expanding in breadth and depth, but half the country is still outside the pavilion in which consumers have voice and choice. Rural land prices in some states have gone through the roof, but in many parts of the country farming remains essentially unviable—with newspaper reports of farmer suicides almost routine. Agricultural growth rates have risen, but the yield per hectare of some crops is barely half of what it is in other countries.

India takes pride in its premier institutes of technology and management, which have been expanding even as they mentor new ones. Seventeen IITs now turn out 10,000 engineers every year. But one Technion in tiny Israel has 10,000 undergraduates, and is partnering Cornell to set up an applied science and engineering campus on Roosevelt Island in New York—something that no IIT could hope to do (if it wanted to, that is). In any case, the IITs account for less than 1% of the total number of fresh engineering graduates in the country, and leading companies say that the majority of people emerging with engineering degrees and diplomas are in effect unemployable. Three-quarters of the 1,000 officially certified business schools would not pass muster in any proper certification process; their alumni can hope at best to find work as frontline sales staff. And lest one forget, the ground-level fact is that the average number of years of schooling in India was just 5.4 (for China it was 7.5), so claims of the country being an intellectual powerhouse are strictly for the home crowd.

India has taken belatedly to building a navy, with almost all new fighting ships now being built in domestic shipyards. But China builds a guided-missile destroyer in two years, less than a third of the time it takes for Mazagon Dock in Mumbai. India’s 2013 law on land acquisitions stipulates processes that could require up to four years to release land for an infrastructure project. That’s more than the two and a half years that it took China took to finish building its 1,318-kilometer Beijing–Shanghai high-speed railway line.

The defense could be that India is a democracy and that the state cannot ride roughshod over people; indeed, the country has been an early exemplar among poor countries for sustaining governance by consent. While democratic processes can be slow, to many citizens the state seems predatory enough, being a systematic violator of basic human rights. Torture is routinely used during police interrogation, and at least half of those in jail should never have been put there.

New Internet entrepreneurs grab the headlines, but old-style conglomerates still subvert the rule-making system; their mishandled projects in steel, power, and road-building have left the country’s banks in a mess. India’s share of world trade has been rising, but the country remains defensive in world trade talks (a reflection of internal weaknesses) and unprepared for the next round of rule changes through supra-regional trading arrangements. It is seen as an emerging power, but the grittiness of everyday Indian reality and the extent of open defecation cast a bad odor over any comforting narrative.

Joan Robinson, the British economist, is frequently quoted for her pithy comment, “whatever you can rightly say about India, the opposite is also true.” So you can spin a hopeful narrative about the delayed blooming of India while someone else spins a depressing story about all the things that are still wrong. In almost every way that you can think of, India is very much a “work in progress.”

Featured image credit: Rupees by geralt. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post India: a work in progress appeared first on OUPblog.

Rethinking innovation and career in the new year

January is a time for resolutions and change. In the excerpt below, the authors of An Intelligent Career: Taking Ownership of Your Work and Your Life explore the role of change in how we start projects, finish projects, and do work.

Thirty years ago, Jean-Luc Brès took an entry-level advertising position in Polydor records (now part of Universal Music group) in Paris, France. Since then, he has watched music sales shift from vinyl, to tape, CD, videodisc, Web downloads, and cloud storage. Meanwhile, he has progressed through roles as advertising representative, advertising manager, marketer, marketing director, and more recently “development manager,” all within the same company.

He describes his present job as “developing new business forms around the music.” That means not only selling the music but also tying in related activities such as the sale of T-shirts, promotion of concerts, and licensing arrangements. one recent project involved working with mobile phone providers on personalized music opportunities for their customers. This opened up both new markets for the music and new ties to show business. Another project involved partnering with retail banks to develop a “music card” to merchandise credit cards to a new generation of cardholders.

He likes to make ideas work, and laughs when he also says he likes making money. He likes to convince people about new projects by sharing his ideas. He argues that you have to tell your bosses what you’re thinking without too many details, so that they see you as the only person for the job. Then you need to make your project succeed by using your relation- ships, and your marketing and product knowledge. You cannot simply transfer all your knowledge to other workers, since you need to have the creativity to face unforeseen situations. That creativity, he insists, belongs to people, not to companies.

He believes that innovation is essential. However, innovation is more than simply hatching a new idea. The difficult part is to make an idea work and to think about and act on all the elements involved. He likes change, and likes to promote it in his company. neither he nor his company can afford to stand still. He says making a mistake is only a problem if you don’t react to it. It’s like cycling. If you stop cycling, you fall. If you keep cycling, and looking for a new direction—whether it’s in a good or bad direction is another question—at least you continue.

His choice of projects has been driven by a mix of the money he can earn, his interest in the work, and the people he can work with. The money enables him to live and to enjoy a comfortable lifestyle. The work feeds his appetite for new learning, about changes in recording and distribution and incorporating them into the company. That means collaborating with newspaper publishers, media outlets, telecommunications companies, retail banks, and performing artists. His relationships with performing artists are “human, rather than economic.” He values working with a good team. “You get money once a month, but you have to work with people every day.”

Despite his thirty years at the same company, his advice to others is to have no set career plan. He acknowledges that some companies, like Procter and Gamble, have proposed a company career model. However, he asks, “How many people are there in Procter and gamble who have had 20 years in the same group? Maybe the system did work out for some of them, but I suspect for many it did not. You need to set yourself a target to take on a new position every three years, and you always need to be mobile. You can use your three years’ experience with Procter and gamble to ask for a better position in another company.”

…imagine yourself in a room with four doors, the one you came in and three more. If you have become familiar with the room, you are ready to look beyond it, so you go through one of the other three doors. Then after you become familiar with the next room, you have the choice of a different set of doors. The change you undergo in each room influences which room you choose next.

Since the interview for his story was conducted, Jean-Luc Brès has taken on another position, this time as CEO of Universal Music and Brands, France, which represents contracted artists to partnering corporate brands. He has persistently changed what he does as his industry has changed. How about you? When will you change? once more, let us explore our opening question through a series of alternative responses, this time covering your experiences with employment contracts, learning, losing a job, starting a project, finishing a project, taking your time, managing risk, breaking free, or diagnosing your current situation.

If “innovation is essential,” as Jean-Luc Brès suggests, how can you contribute to it? Science writer Steven Johnson has borrowed biologist Stuart Kauffman’s idea of the “adjacent possible” to help us understand and make the most of the opportunities available to us. an example is the video-sharing website YouTube, launched with immediate success in 2005. YouTube relied on users having the necessary graphical and video-sharing software and a high-speed Internet connection. The founders of YouTube recognized that their idea had become possible, and the number of potential users could rapidly grow. In Johnson’s words, the adjacent possible is “a kind of shadow future, hovering on the edges of the present state of things, a map of all the ways in which the present can reinvent itself.” YouTube’s founders got their timing right, and their innovation caught on.

Johnson invites you to imagine yourself in a room with four doors, the one you came in and three more. If you have become familiar with the room, you are ready to look beyond it, so you go through one of the other three doors. Then after you become familiar with the next room, you have the choice of a different set of doors. The change you undergo in each room influences which room you choose next. Johnson is writing about innovation, but he could just as well be writing about Brès’s career. If a room represents one of his three-year projects, then he has gone in and out of ten or more rooms. as he completed each project he saw a new door to further opportunity—a key to why he worked. In the new room he would both apply his expertise and seek new learning—keys to how he worked. He would also draw on existing relationships and build new ones—a key to with whom he worked.

Projects are everywhere. All employers—including public sector employers—need to innovate to remain relevant. Brès’s projects in developing new products have their parallels in a wide range of industries—automobiles, biotechnology, consumer goods, financial services, healthcare, information technology, pharmaceuticals, and many more. Many industries have an explicit project-based approach to organizing—such as accounting (audits), construction (roads and buildings), filmmaking (movies), law (cases), software (programs), and so on. Even where those projects are led by large established firms, the underlying employment arrangements rely on a continual f low of new projects. Where are your projects?

Let us look more closely at filmmaking. Typically, a new production company is established for each new film. Then the producer, director, screenwriter, financial backers, and lead actors are secured. The process goes on through the rest of the cast, camera operators, set designers, wardrobe specialists, special effects people, stand-ins, grips, personal assistants, accountants, and—not least—runners, whose lowly positions often provide privileged learning opportunities at the heart of the action. You get invited to join a new project based on the commitment you’ve shown before, the skills you’ve demonstrated, and the people you’ve come to know. Each project requires change.

For each of the film crew’s participants, their objectives are two-fold: First, play your part and do what you can to help the project succeed; second, learn something new, both for its own sake (it keeps work interesting) and to better position yourself for future projects. Regarding the first objective, the film industry is already organized to celebrate the separate contributions people can make. A movie can fail to win critical acclaim and still earn “Oscars” or similar awards for its actors, screenwriters, cinematographers, and so on. The range of awards means that reputation is built largely in the specialization for which each person was invited to join up. Regarding the second objective, filmmaking may offer a relatively privileged environment. There is regular “down time” between shoots in which people can get to know each other better, gain a wider perspective, and trade experiences. Learning happens on the set as well, when actors, crew, and directors hone their complementary talents.

Not everyone in filmmaking gets the same opportunity for down time, and not everyone takes the same advantage of it. However, people in filmmaking have it better than people in many other kinds of projects. Mainstream guidelines about project management focus on using people efficiently and completing the project both on time and under budget. Project managers’ performance is typically measured on these criteria, and the notion of projects providing fresh learning opportunities for their participants is largely absent. The guidelines may suggest that you reflect back on the project after its completion, but that advice comes too little, too late, for the intelligent career owner’s purpose.

The solution is to seek out fresh experiences for yourself and on your own terms. You can bring parallel objectives to (1) make a contribution to the project and (2) learn as you go. You can see the two objectives as synergistic with one another, since demonstrable commitment to project success is more likely to earn learning opportunities from others. To paraphrase Denise Rousseau’s message from earlier in the chapter, the end of a project means a return to free society and the opportunity to take on something new. The renewed motivation, enhanced skills, and additional contacts you have made are yours to bring with you.

Featured image: Electricity by oadtz, via Pixabay (CC0 Public Domain)

The post Rethinking innovation and career in the new year appeared first on OUPblog.

Labeling right in the age of Trump

Steve Bannon is a white nationalist. That was the first media characterization I heard of the former Breitbart executive after his appointment as chief strategist and senior counselor to President-elect Donald Trump on 13 November 2016. During the month that followed, center-left commentators also described Bannon as a “racist,” a “white supremacist,” a “white separatist,” a “neo-Nazi,” a “fascist,” a “neofascist,” a “right-wing extremist,” a “right-wing populist,” a “far-right ideologue,” an “ultraconservative,” and an “ultra-rightist demagogue.” Further, and in step with Bannon’s own statements, many linked him with the so-called “alt-right”—a movement that Hillary Clinton described in a speech as nothing but the latest version of “white supremacy” and “white nationalism.”

Labels matter to me. Much of my life since 2010 has focused on studying movements in the Nordic countries that are often described in the same terms as Bannon. I followed these groups as they transformed from a music-based, hooliganistic youth subculture to a dynamic political and cultural force poised to shatter the foundations of progressive liberalism. Yet I almost never describe them with words like “racist,” “fascist,” or “extremist.” Instead, I label them as they label themselves: “nationalists.” I’m often criticized for this choice, with some alleging that my language euphemizes and normalizes dangerous causes. Though such concerns are valid, I have nonetheless come to think that deescalating the tone of our language is vital if we want to better understand the political earthquakes reshaping our world today.

I study nationalists through face-to-face ethnographic fieldwork; by observing, interviewing, corresponding, and spending time with them informally, and this impacts the way I think and talk. Like the surface of an oil painting, people too appear more complicated and chaotic when you view them at a close distance. After years of interacting with nationalists, I found I could no longer subscribe to commentary that glossed their internal differences or simplified their motivations and aspirations. The individuals I followed share an opposition to immigration and multiculturalism, as well as affiliations with obscure nationalist subcultures, but their thinking is in other respects diverse. They disagree over issues as fundamental as the nature of national identity, their ideal relationship with minority groups, who their past and present allies are, and how to achieve political change. Their stances on these topics, further, have real consequences for how they organize themselves and what agendas they choose to pursue.

If we know someone is a “fascist,” we need know no more. Thus a cycle is born, one where ignorance informs our language, and our language breeds further ignorance.

If we want to describe these people as a whole, in other words, our language must be encompassing. And if we approach them as outsiders, as I assume most readers of this blog do, our language ought to feed rather than starve curiosity. That is one additional reason why I favor the relatively undescriptive term “nationalism” as a scholar: I don’t want anybody—including myself—getting the idea that we actually understand what’s going on right now. Contemporary nationalists are not reincarnations of 1930s fascists, nor can their causes be generalized with any meaningful degree of specificity. It is not self-righteousness or elitism, but intellectual laziness that lets us claim otherwise.

Which brings us back to Steve Bannon. The way he and others like him are portrayed in our public conversation—the labels themselves and their uncanny multitude—is a product of that laziness. Center-left commentators appear united in their belief that Bannon represents a profound threat to core liberal values, but they disagree as to what kind of threat it is and how to describe it. What I find relevant is not the disagreement itself so much as the lack of reaction to it. “Right-wing populism,” it seems, can as well be called “neo-Nazism” and vice versa. Perhaps that’s because journalists have some explanation as to why those labels are synonymous, but I doubt it. Instead, we don’t really know what to make of the movements and figures on the rise today, and some respond to that uncertainty with verbal spasms made of the most familiar incendiary language they can find. And when new terms emerge in public conversation, like “alt-right” in the US or “identitarianism” in Europe, we neutralize their potential to stir our thinking by reducing them to recognizable nomenclature (e.g. Clinton’s speech).

Though commentators may not know what defines and distinguishes “neofascism,” “neo-Nazism,” or “ultra-rightist demagoguery,” they send an unmistakable signal with those terms nonetheless. They suggest that someone or some cause rests beyond the pale of our political spectrum and is therefore undeserving of serious consideration. Maybe that’s an appropriate, if hopeless, response in this case. However, one of its negative consequences is that it allows us to excuse ourselves from further inquiry. If we know someone is a “fascist,” we need know no more. Thus a cycle is born, one where ignorance informs our language, and our language breeds further ignorance.

No doubt, we owe it to ourselves to examine carefully and critically the changes that are occurring around us. Remaining aware of historical precedent is always important, but so too is spotting the novelty of what is happening now. Let’s hope that our language allows us to do that.

Featured image: New Yorkers protest Donald Trump and media racism by Joe Catron. CC-BY-NC-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Labeling right in the age of Trump appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers