Oxford University Press's Blog, page 420

January 11, 2017

Salafism and the religious significance of physical appearances

There are probably few trends within Islam that are associated as much with “extremism” as Salafism, among the general public. One reason for this is that groups such as al-Qa‘ida and the Islamic State (IS) have used a radical form of Salafism to justify their acts of terrorism. Despite the fact that most Salafis not only refrain from engaging in such acts themselves but also actively condemn them, politicians from various Western countries have called for banning Salafi organisations or even Salafism altogether, such as in the case of France and the Netherlands.

A second reason why many people seem to fear Salafis is their physical appearances, particularly the physical appearances of Salafi women wearing the facial veil (niqab or jilbab). The latter is not just perceived as a potential security threat – because it allows one to hide one’s features – but also as something that hampers everyday conversation and, perhaps most importantly, challenges Western cultural norms. Because of a combination of these reasons, several European countries have adopted laws to partially ban facial veils in public. However, very little has been said about what the niqab or other forms of physical appearances among Salafis actually mean and what their religious origins are.

Salafism can be defined as the trend within Sunni Islam whose adherents claim to emulate the first three generations of Muslims as strictly and in as many spheres of life as possible. (These first three generations are known as al-salaf al-salih (the pious predecessors), hence the name “Salafism.”) For Salafis, the emulation of early Muslims – and particularly the Prophet – is of the utmost importance. This is why they spend much time ‘cleansing’ (tasfiya) Islamic tradition from supposedly false reports (hadiths) about Muhammad and other man-made ‘religious innovations’ (bida‘, sing. bid‘a). The end result of this process is meant to be a form of Islam that is exactly like what the Prophet and his companions themselves did and, as such, a blueprint for modern-day Salafis’ lives.

Emulating the salaf in every detail is only one side of the Salafi coin, however. Strictly following the predecessors also involves distinguishing oneself from others; this shows that one does not belong to other groups, but only to Islam. Two concepts are of great importance in this respect. The first of these is ghuraba’ (strangers), a term used in a hadith ascribed to the Prophet in which he calls on his followers to be strangers in the world. Salafis interpret this as meaning that while they may have many attachments in life, Islam is ultimately their one and only home. The second concept is al-wala’ wa-l-bara’ (loyalty and disavowal), which Salafis use to stress their complete loyalty to God, Islam, and fellow-Muslims and their utter rejection of everything else.

“Bui Bui” by Michał Huniewicz. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

“Bui Bui” by Michał Huniewicz. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.The facial veil or other forms of physical appearances among Salafis should be situated in the ideological context given above. For women, the wearing of a niqab or jilbab is closely related to passages from the Qur’an that mention the need to cover parts of the body (especially Q. 24: 31; 53: 53-55, 59). What parts of the body should be covered, however, is less clear. The Qur’an mentions words like zina (adornment) and scholars label the area that should be covered ‘awra. Although this word can be translated as “genitals”, Salafi scholars often believe – based on hadiths about the wives of the Prophet – that women should cover their entire body. The famous Syrian Salafi scholar Muhammad Nasir al-Din al-Albani (1914-1999), however, argued on the basis of both the Qur’an and hadiths that the face and hands are excluded from the ‘awra and that women may therefore uncover these.

For men, a white tunic (thawb or dishdasha) is often seen as preferable, based on a hadith that states that the best clothing for both the mosque and the grave is white. The length of the tunic is also significant. Salafi men often make a point of wearing garments above their ankles, following Prophetic precedent. With regard to their headdress, Salafi men can often be seen wearing a large white skullcap (qulunsuwa), again based on hadiths mentioning that the Prophet wore this, which is frequently covered by a piece of cloth (shimagh) that is usually not held in place by the circlet of rope (‘iqal) that many other Muslims do wear.

Physical appearances among Salafi men, precisely because they do not cover their faces, involve more than just clothes. This can be seen first and foremost in the beard. According to hadiths, the beards of several prominent early Muslims – including the Prophet himself – were thick and/or long and Salafis therefore often allow their beards to grow in abundance although, again in emulation of the Prophet, they do make sure to keep it clean and looking good. Based on another hadith, Salafi men also often trim or even shave off their moustaches, although the latter is not very common.

The physical appearances of Salafi women and men are thus strongly linked to their general norms and go to the very core of what Salafism is all about: living in full accordance with the example set by the Prophet and his companions, but also distinguishing oneself from others, including non-Salafi Muslims. Particularly the latter aspect of emulating the salaf often causes one to stand out and attract unwanted attention, making it difficult sometimes. Still, distinguishing oneself from others by clinging to one’s beliefs is precisely what the concepts of ghuraba’ and al-wala’ wa-l-bara’ are all about. As such, the appearances of Salafis form a significant part of what being an adherent to Salafism means in daily life and physical features such as a niqab or a long beard are therefore of great religious significance to them. Recognizing Salafis’ beliefs may not help take away fears about their views and practices in general, but it can lead to understanding why Salafis look the way they do at the very least.

Featured image credit: “Group of Women Wearing Burkas” by Nitin Madhav. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Salafism and the religious significance of physical appearances appeared first on OUPblog.

January 10, 2017

How has map reading changed since the 1600s?

Literacy in the United States was never always just about reading, writing, and arithmetic. Remember in the 1980s and 1990s the angst about children becoming “computer literate”? The history of literacy is largely about various types of skills one had to learn depending on the era in which they lived. Some kept their name, but changed in substance. Map literacy is one of those.

When colonists began occupying the North American continent in the 1600s, it soon proved essential to know how to draw a map, such as of the boundaries of one’s farm or town, and to be able to read a map. When Thomas Jefferson completed the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the first thing he did after recovering from sticker shock—the deal had cost 50% more than the annual budget for the entire federal government—was to immediately send a team of soldiers and scouts to map what he had just purchased. His Louis and Clark Expedition developed some of the initial maps of the continent from Virginia to the Pacific Ocean. For the rest of the 1800s when it was not fighting wars or Indians, the US Army mapped in detail the United States.

When the National Park System was developed in the late 1800s and expanded across all of the twentieth century, the Army and park personnel developed the maps we use today when hiking in these areas, including the wilderness that has no roads. After satellites were launched into space, the American government continued to map the United States, beginning in the 1960s.

One of the subjects children learned in school was how to read a map, almost from the 1600s on. By the dawn of the twentieth century, it was common for classrooms at all grades to have a map of the United States hanging on the wall. By the 1940s, children were learning how to draw, recognize, and read maps of their towns and states. One of the core skills taught to all boy scouts, girl scouts, and other children’s national organizations was how to read a map.

When people began to travel by automobile in the 1920s, states built highways. Then in the 1950s, the federal government started creating the national highway system that we have today. To get anywhere they had to be able to read a map. The large gasoline vendors began to produce maps of the American road system in the 1920s and gave them away at gas stations. By the 1940s, it seemed every state government produced richly detailed maps of all the towns and roads in their state. So, just to get around, people needed to know how to read a map as much as they needed to know how to read a book.

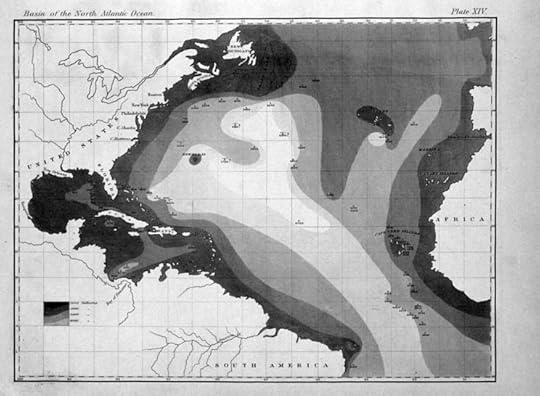

The very earliest rendition of a bathymetric map of an oceanic basin by Matthew Fontaine Maury. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The very earliest rendition of a bathymetric map of an oceanic basin by Matthew Fontaine Maury. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Then came smartphones, beginning with Apple’s in 2007 and a bit earlier, Internet Mapquest functions. Now things shifted from having to read a map, to obtaining directions on how to go from one spot to another. But even with Mapquest pulled down onto your laptop, a map was included, although not always as accurate as earlier ones. Many Americans still keep an old paper Atlas of maps around, just in case. With smartphones, do we still use, or even need maps?

It appears we do. At the moment, the concept of the flat paper map, first developed in the 1500s, is still with us. Even though these maps distort the size of countries—for example making Iceland look like almost the size of Africa when it is in fact pretty tiny—they are still used to teach students where places and countries are on earth. More exciting is the use of mapping to understand the surface of various planets and, of course, our moon. Mars is in the process of being mapped as you read this. High school children who take an introductory astronomy course learn to read maps again. All military personnel are taught map reading as part of their initial training. Since GPS signals often are not available in large wilderness parks in North America, the old fashioned foldout paper map becomes as essential as almost any other survival tool hikers and campers carry with them.

Speaking of GPS—Global Positioning System—it was developed in the United States and launched in 1973. In effect, it is like a digital map that can pinpoint the location of people and things within inches. Satellites using GPS are used to create specialized maps, such as those of the bottom of an ocean, the height of mountains, and changing sea levels, among others. Storms and other weather conditions have been imposed on maps since the 1860s in North America and Western Europe. GPS has made mapping the most precise it has been in human history, automated by satellites, computers, and (increasingly) drones.

Like other types of literacy, the need for map literacy has not gone away. It just keeps changing. Why? Our dependence on map information is greater today than at any time in human history. So, the next time you go on vacation, don’t forget to bring along a map, as you will probably need it.

Featured image credit: The World Showing British Empire in Red (1922) by Eric Fischer. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post How has map reading changed since the 1600s? appeared first on OUPblog.

On not taking Trump literally

Donald Trump has always had a rocky relationship with the truth. The fact that his pronouncements often fail to align with reality has now simply become an accepted fact. In earlier times candidates who spoke this way would have quickly fallen off the map. Why not Trump? One interesting take on this is the claim that his statements should not be taken literally. What exactly does it mean to not take something literally? Is this just an after-the-fact excuse for his impulsive pronouncements? Or is it something else? And if his statements are not to be taken literally, then how should they be taken? What is the alternative to taking something literally?

Nonliteral language is common. Metaphor, hints, hyperbole, sarcasm, irony, politeness, and many others are all instances of nonliteral language; times when a literal reading (taking words in their most basic sense, with little in the way of interpretation) fails to capture the speaker’s intended meaning. Sometimes the intended nonliteral meaning is the exact opposite of the literal meaning, as with sarcasm. People speak nonliterally frequently and usually without communicative difficulty. Although nonliteral language is potentially ambiguous (more on this later), misunderstanding is often minimized because people typically know how to interpret nonliteral language. This is largely a result of the fact that we tend to converse with others who know what we know, that is, with whom we have a degree of shared common knowledge. So when I say to my friend “My job is a jail” he will take me to mean that my job is like a jail; in other words, that I am speaking metaphorically. My friend knows where I work and that it is not literally a jail. If I would say this to a complete stranger there is an increased risk of misunderstanding.

Donald Trump’s most frequent trope is hyperbole, the use of extreme exaggeration that is not intended to be taken literally. For example, during the presidential campaign Trump claimed that President Obama was the founder of ISIS. Many observers assumed that this was not to be taken literally; obviously Obama was not literally the founder of ISIS, although one might argue that he created the conditions for the rise of Isis. When Trump was asked about this the next day by host Hugh Hewitt and given the opportunity to opt for the nonliteral meaning, he refused, confounding almost everyone. Or take his claim that he will build a 50-foot wall along the Mexican border, that Mexico will pay for it, and that it will be a great, great wall. Hyperbolic exaggeration, right? Possibly. We simply don’t know.

US-Mexico border at Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico; and California. Photo by Tomas Castelazo. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

US-Mexico border at Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico; and California. Photo by Tomas Castelazo. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Why so much hyperbole? Why make extreme pronouncements that are clearly not true? Trump himself, in his book The Art of the Deal recommends such a strategy, a strategy that he calls truthful hyperbole (which of course is a logical impossibility). The idea is that hyperbole can be useful in negotiations, a means of staking out an extreme, initial position. Well, he didn’t really mean (literally) that the United States would build a 50-foot wall, or that Mexico would pay for it, but rather that he would take an extreme and firm position on immigration. Also, hyperbole can be used to elicit an emotional reaction in recipients. No doubt this appears to be one of Trump’s goals at his rallies, and it is there that he frequently speaks nonliterally. He also exaggerates frequently when he tweets, possibly for the same reason.

Another advantage of saying things nonliterally is that it gives one the option of deniability. Hence Trump can respond to any criticism of an exaggeration by simply saying he didn’t mean it literally. Who would take literally a claim about building a 50-foot wall along the Mexican border? Or that Obama is the founder of ISIS? The benefits of this move have been described and documented by Steven Pinker. In this way, nonliteral language allows one to have it both ways; if not questioned, the assertion stands, but if questioned he can just claim that he wasn’t speaking literally, a move that Trump has sometimes made.

So what’s the problem? First and foremost, with nonliteral language there is an increased risk of misunderstanding. Certainly literal meaning can be misunderstood, but nonliteral meaning requires an extra layer of interpretation that increases the likelihood of misunderstanding. Also, our beliefs and attitudes often influence how we interpret what others say, especially when they speak nonliterally. For example, when Stephen Colbert played a blow-hard conservative commentator on the Steven Colbert show his satire was fairly obvious, but not to all. Some actually took him quite literally. This of course is partly the reason that die-hard Trump supporters are relatively unbothered by his over-the-top pronouncements.

The likelihood of misunderstanding with nonliteral language is increased when speaking to people from different cultures. This is because the knowledge that underlies how something is to be taken varies over cultures and this can become an obstacle for cross-cultural communication. President Trump’s pronouncements will be heard (and potentially misunderstood) all over the world; those not familiar with his style may be misled.

In the end, no one really knows what Donald Trump means with some of his more extreme pronouncements. His utterances may be strategic, an attempt to manipulate the emotions of a crowd, to create chaos, to establish a particular line for a negotiation. The problem is that being President of the United States is different from doing real estate deals. A president’s words have consequences; they can move markets and start wars. This is not to say that presidents shouldn’t speak metaphorically. They can and have and usually with good effect. When Bill Clinton said he wanted to “build a bridge to the 21st century” everyone knew he was speaking metaphorically. But not everyone knows how to take Donald Trump’s remarks. The relationship between intentions and language is murky at best. In Trump’s case it may be non-existent.

Featured image credit: Donald Trump speaks at a campaign event in Fountain Hills, Arizona, before the March 22 primary. Photo by Gage Skidmore. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post On not taking Trump literally appeared first on OUPblog.

Brexit and the Anglo-German relationship

As Britain embarks on its journey towards the exit from the European Union, the Anglo-German relationship is bound to play a central role. No other country is likely to matter more for the outcome of the negotiations than Germany, one of the UK’s most reliable partners in recent years. So how should we now think of this relationship which has defined modern Europe? In trying to find an answer it makes sense to consider the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in one context. We have grown accustomed to a narrative that uses the period before the First World War as the mere foil against which to narrate the ‘rise of antagonism’, a dramatic shift from friendship to enmity. Yet throughout the Victorian age Britain and Germany were neither joined in comprehensive alliance, nor locked in conflict: politically speaking, they were neither friends nor foes.

Under Bismarck and Salisbury this was a partnership which expressed both dependence and distance: dependence because London and Berlin shared underlying interests and co-operated effectively; distance because they were unable to come to a formal agreement which would have given the Anglo-German relationship a more long-term basis during the second half of the nineteenth century. What took place in the decades before the First World War was not an inevitable shift towards enmity, but an increase in both co-operation and conflict. While the image of two hostile nations facing each other across the North Sea came to dominate in public discourse, Britain and Germany had in fact reached unprecedented levels of mutual dependency. The two nations’ wealth were interlinked: it was by trading with the other country and by co-operating in global markets that Edwardian Britain and Wilhelmine Germany prospered. A dense web of mutual ties linked the two nations not only economically, but also through a myriad of cultural and scientific activities, which included engineering, education, research, publishing, architecture, music, and literature. The naval race and a series of diplomatic blunders established a new language of enmity in the decade before 1914, but it did not alter the two countries’ underlying interdependence. On the contrary: at the height of political conflict the two countries were more closely bound up with one another than ever before.

It is the second half of the nineteenth century, rather than the traumatic period of the two world wars, which is likely to hold clues for our understanding of the latest transformation of the Anglo-German relationship. What characterises both countries today is again a high degree of mutual interdependence. Economically and culturally Britain and Germany are more closely bound up with one another than at any other point in the modern period. Crucially – and this is the main difference to the nineteenth century – this applies also in a geopolitical sense: the two nations are firm partners in a global alliance dominated by the US. The European Union has translated this political partnership into a vast range of structures which have facilitated the entwining of British and German societies. All of this has made co-existence and interdependence so much of an every-day fact that it has become difficult for younger generations to appreciate just how conflict-ridden and violent the Anglo-German past was in the first half of the twentieth century.

It remains to be seen in how far the British exit from the European Union will loosen the ties that bind the two countries together. Crucial to the outcome will be in how far the British government feels compelled to restrict the freedom of movement from which its own citizens and those of the EU have benefitted over the last few decades.

Nothing has shaped the Anglo-German relationship more consistently through the past two centuries than the fact that people never stopped moving between the German and English-speaking parts of Europe. The few periods during which one or both of the two countries tried to put a stop to exchange and movement were periods of unprecedented instability or violent conflict. If there are any lessons to be drawn from this relationship as it has developed over the past two hundred years, it is this: just as Germany is unable to control an increasingly unpredictable Europe, Britain will be unable to escape it.

Featured image credit: “Kultur ist great” – advertising Great Britain in Germany by Richard Allaway. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Brexit and the Anglo-German relationship appeared first on OUPblog.

Rethinking if not resetting

A quiet but intense debate has been going on among the dwindling group of Russian experts in the United States and Europe, who are increasingly disturbed by the hyperbolic rhetoric about Russian leader Vladimir Putin during and since the American presidential campaign, in the media, and from public intellectuals. Putin has been described as Hitler, Stalin, without a soul, and even crazy. Hillary Clinton concluded that as a former KGB agent he had no soul. Angela Merkel famously said that Vladimir Putin lives in a different world. It certainly looks that way from where I was sitting in St. Petersburg, Russia. But not the way the German chancellor meant.

From the Russian side the words and images are equally Manichaean. Almost every problem from the expansion of NATO, global electronic surveillance, the threats of cyber warfare, and the crisis in Ukraine to the price of cheese is blamed primarily on the United States and its perceived global ambitions to render Russia weak and isolated. The discourse on talk shows is so inflated that many ordinary Russians are turned off, even as public statements escalate the fear of war. The palpable material hardship caused by economic sanctions and Russia’s failure to diversify and build infrastructure in the flush years when oil and gas prices were high has combined with fatigue at the lack of effective reform and the meaningless spectacle of elections without a real choice to produce a rumbling discontent. Even the nationalist fall-back position – “Well, at least Crimea is ours!” — has begun to sound hollow. Anxiety is growing both in Russia and in the West, and notably among Russian experts, that the war of words can lead to other kinds of war –cyber, Cold, or worse.

The alternative, of course, is to re-open channels of conversation, deliberation, and negotiation, which requires a clearer understanding of the views, perceptions, and interests of the other side than is currently presented in much of the West. First, Putin is neither Hitler nor Stalin, neither a fascist, as has been claimed on the op-ed page of the New York Times, nor a communist. He does not aim at recreating the Soviet Union or destroying the European Union. He has stated publicly that he is not interested in making Russia a Great Power again, a statement that should be taken with a large grain of salt, but he is certainly interested in making Russia “Great Again.”

Vladimir Putin, by the Kremlin. CC-BY-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Vladimir Putin, by the Kremlin. CC-BY-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.More sober observers, including Henry Kissinger, have concluded that Vladimir Putin is a realist playing a relatively weak economic and military hand vis-à-vis the United States, NATO, and the European Union. Putin and the most savvy of policymakers in Russia want not only to be respected and consulted but to be members in good standing in the global capitalist economy and the security structure of the post-Cold War world. They resent the overweening power of the United States and oppose the unipolar system that replaced the bipolar Cold War system. The West squandered the greatest opportunity the world had to reshape the international security order in the early 1990s, instead taking advantage of Russia’s weakness to move its zone of military influence closer to the borders of Russia (and in the case of the Baltic states, within the boundaries of the former Soviet Union). After violating acceptable international behavior with the ill-advised annexation of Crimea, Russia only increased its pariah status. Its calls for a multipolar international system fall on deaf ears in the West, which interprets the expansion into Ukraine as an imperial drive to destabilize European security.

Vulnerability more than a desire for territorial expansion better explains his ill-considered and precipitous gamble in annexing Crimea. In the panic that followed the replacement of a more pro-Russian government in Kiev with a pro-Western one, Putin’s earlier, more pragmatic policy either to win over Ukraine or render it neutral suddenly, with that one rash move to “return” Crimea to Russia, perhaps to appease Russian nationalists at home, turned Ukraine for generations to come into a more nationalist anti-Russian state. Fearing a NATO takeover of its naval bases on the peninsula, Russia self-destructively propelled itself into an untenable position. Politically Crimea cannot be returned to its earlier status within Ukraine without the Kremlin bosses losing the favor of most Russians. Moscow is stuck with Crimea, an example of imperial overreach that defies easy digestion and serves to confirm the West’s worst suspicions about Putin’s intentions.

Russia spends less than ten percent of what the West spends on defense, and the Russian economy is eight times smaller than that of the United States or the European Union. California’s gross domestic product is almost twice the size of Russia’s, which ranks twelfth among nations. Instead of being able to confront the West directly, Russia resorts to muscle flexing, including both pinprick annoyances like overflights in the Baltic region, more serious threats like placing Iskander-M missiles in the Kaliningrad enclave and deploying what military and diplomatic leverage it has in Syria or Iran to make itself indispensable to the international community. The Kremlin annoys and provokes with its cyber intrusions, the latest weapon of a relatively weak state.

Russians overwhelmingly share Putin’s views that their country has been mistreated by the West, humiliated repeatedly, their interests not taken seriously in Washington and Brussels. While Americans and Europeans, particularly in Eastern Europe, believe American power to be indispensable and NATO expansion a positive contribution to strategic stability, Russians genuinely feel threatened. A young woman in Moscow approached by BBC reacted to the assassination of the Russian ambassador to Turkey by reminding the journalist how Russians feel vulnerable and humiliated. The memories of Poles, Czechs, Estonians, and others of Soviet domination of their countries are mirrored by Russian memories of the colossal destruction they suffered from European invasions in the twentieth century’s two world wars.

Russians overwhelmingly share Putin’s views that their country has been mistreated by the West

It is urgent to move beyond the current impasse, and that requires new thinking and less name-calling. Ironically, the president-elect, who has far less foreign policy experience than the defeated former Secretary of State, has potential advantages in dealing with the Kremlin. Both he and President Putin have indicated that they admire each other and have refrained from the hyperbolic rhetoric of more establishment foreign policy experts in the United States and pundits in Russia. Fresh starts are possible, though they require readjustments on both sides. Most importantly, Washington and Moscow have to consider the interests and insecurities of the other side.

The real story is that at the moment the United States and Russia are both indispensable nations, each in its own way. Both are required to stabilize the international order and solve global problems like the flow of refugees, climate change, and terrorism. A shift from dominance by a single power to a more multilateral and consultative international order is not only an essential first step but is probably inevitable in the near future as the power relations between the most economically prosperous states change. To cool the current overheated tensions between Russia and the West, the stronger player has to make the first move. Washington, convinced that the United States has interests in all parts of the globe, must take seriously Russia’s more immediate and regional perception of its interests.

President Obama once dismissed Russia as a “regional power,” but from such condescension he was forced to recognize Russia as an “important” power. A global hegemon should be able, however uneasily, to inhabit the same world as a relatively weak regional hegemon. Coexistence as unequal rivals and wary partners requires more carefully formulated understanding of the other than the current rancor allows. Differences need not necessarily lead to conflicts, and conflicts need not inevitably lead to violent confrontations. Words matter, however, and shifts in language, and a willingness to listen to your adversary, can ease the way to cautious cooperation.

Featured image credit: Top of the Kremlin. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Rethinking if not resetting appeared first on OUPblog.

January 9, 2017

Three myths about the Electoral College

Since the election, we Americans have engaged in a healthy debate about the Electoral College. My instincts in this debate are those of an institutional conservative: Writing our Constitution from scratch today, we would not have designed the Electoral College as it has evolved. However, institutions become embedded in societies. Apparently compelling reforms, when implemented, often generate undesirable and unforeseen consequences.

Moreover, institutions often adapt to roles different from those anticipated by those who crafted such institutions. During the summer, when I decided that I could vote for neither major party candidate for president, I proposed that, where possible, bi-partisan unpledged slates of presidential electors run to provide an alternative. In the future, such an approach might commend itself if we are again confronted with two major party candidates viewed as unfavorable by the general electorate as were Secretary Clinton and President-elect Trump.

To further this debate, consider these three contentions often heard today about the Electoral College.

1. The Electoral College always favors Republicans. Advocates of this position point to President Bush’s loss of the popular vote in 2000 and to President-elect Trump’s larger loss of the popular vote in 2016. However, in the run up to the 2016 election, Clinton partisans were touting her “blue state firewall” in the Electoral College. I can find no public utterance by any prominent Democrat objecting to the possibility that Secretary Clinton might prevail in the Electoral College even if she lost the popular vote. The editorial board of the New York Times, which now calls for abolition of the Electoral College, was similarly silent about the prospect that Secretary Clinton might prevail in the electoral vote while losing the popular vote.

The narrative that the Electoral College always favors Republicans is wrong in another respect: As careful observers of the 1960 election have demonstrated, it is likely that Richard Nixon, not John Kennedy, won the popular vote in that year. No votes were explicitly cast for Kennedy or Nixon in Alabama since neither of their names appeared on that state’s ballot. Kennedy’s national popular vote total over Nixon rests on the unrealistic allocation to Kennedy of all of the votes cast in Alabama for a Democratic slate of electors, half of whom were pledged to vote against Kennedy in the Electoral College.

Camelot may thus have been a creature of the Electoral College.

2. For the victor in the Electoral College to lose the popular vote is a uniquely American phenomenon. Not so. Under parliamentary systems, it is possible for the victor to lose the popular vote but prevail by winning the most parliamentary seats. This happened twice in Great Britain in the second half of the twentieth century. In 1951, Britain’s Labor Party garnered more total votes in the aggregate, but the Conservative Party, with fewer popular votes, won more seats in the House of Commons. Consequently, Winston Churchill became Prime Minister. In 1974, the reverse occurred: The Labor Party received fewer votes nationwide but won more parliamentary seats. Hence, Harold Wilson, while losing what Americans call the popular vote, was elected Prime Minister.

3. The “winner take all” allocation of states’ respective electoral votes is bad. But the “winner take all” method is not required by the Constitution. Each state decides for itself how to award its electoral votes. Today, two states – Maine and Nebraska – allocate an electoral vote to the presidential candidate who carries a congressional district, even if that candidate loses the statewide popular vote. This happened in 2016 as President-elect Trump received one electoral vote by winning Maine’s second congressional district even as Secretary Clinton received Maine’s other three electoral votes. Other states can emulate Maine and Nebraska and allocate their respective electoral votes by congressional district. Alternatively, a state could also allocate its electoral votes proportionately so that, for example, a presidential candidate winning 40% of the statewide popular vote would receive 40% of the state’s electoral votes.

Those who would abolish the Electoral College bear the heavy burden of overturning a 200 year old institution which has become embedded in our society. The fact that Secretary Clinton prevailed in the popular vote but lost in the Electoral College does not carry that burden. As I suggested last month, the popular vote which occurs under the Electoral College is not necessarily the vote which would have occurred in a direct election for president conducted under uniform national rules.

Featured image credit: white house Washington president by gunthersimmermacher. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Three myths about the Electoral College appeared first on OUPblog.

Heavy-metal subdwarf

An international team of astronomers led by Professor Simon Jeffery at the Armagh Observatory in Northern Ireland has discovered a small, very blue helium-rich, and hot star called UVO 0825+15, which has a surface extremely rich in lead and other heavy metals and varies in brightness by up to 1% every eleven hours. Only the fourth “heavy-metal subdwarf” discovered, and the second to be variable, the new star raises major questions about how these stars form and work.

The overwhelming majority of stars, like the Sun, consist mostly of hydrogen, from the surface through to the core, where nuclear reactions convert hydrogen into helium and keep the star shining for billions of years. When hydrogen in the core is used up, a star starts to burn helium. However, its surface remains almost unchanged, even in rare cases when the surface hydrogen has been stripped away to leave less than 1% of the original star. These stripped helium-burning stars are small, being about half the mass and one tenth the size of the Sun — but having surfaces five times hotter and 25 times brighter than the Sun, are known as “hot subdwarfs” (stars like the Sun are known as dwarfs, to distinguish them from the much larger giants).

The new discovery was made during a search for pulsating hot subdwarfs using NASA’s planet-hunting Kepler spacecraft. Serendipitously, the same star was also observed in a search for chemically peculiar stars using Japan’s 8-m Subaru telescope on Hawaii.

Apart from hydrogen, star surfaces usually consist of about 28% helium and up to 2% other elements (by mass), being mostly oxygen, nitrogen, carbon, and iron. The abundances of exotic heavy elements such as zirconium, strontium, or lead are so small as to be measured in parts per billion. UVO 0825+15 had already been identified as a helium-rich hot subdwarf, having two or three times more surface helium than the Sun, and tens of times more than normal hot subdwarfs.

The new Subaru observations of UVO 0825+15 revealed the signature of triply-ionized lead, implying that the star’s surface contains 5,000 times more lead than the Sun. Yttrium and germanium are also enriched by factors of several thousand. The chemistry is thought to be due to intense ultraviolet light, produced by the high surface temperature and brightness.

These stripped helium-burning stars are small, being about half the mass and one tenth the size of the Sun — but having surfaces five times hotter and 25 times brighter than the Sun, are known as “hot subdwarfs”

The surfaces of hot subdwarfs are quite unlike that of the Sun. In the latter, heat is transported upwards by convection and the surface layers are a bubbling cauldron of hot plasma rising, spreading, cooling, and sinking. These motions give rise to sunspots and flares which occur on timescales of months and days. In contrast, hot subdwarfs have no convection; plasma moves very, very slowly … being heavier than hydrogen, helium can sink out of sight on timescales of 100,000 years.

The ultraviolet light at the surface of UVO 0825+15 reacts with ionised atoms in the star’s atmosphere, producing a very small upward force that changes with temperature and from element to element. The result is a multi-layered atmosphere, with exotic ions concentrated into strata at precise temperatures by light pushing upwards. If an atom sinks beneath its equilibrium position, light pushes it back up; if it floats too high, light pressure weakens and it sinks back down. Thus we find a star where a thin layer of lead may be floating on light.

Observations of UVO 0825+15 made over 75 days with the Kepler spacecraft revealed unusual light variations. Most stars seem not to vary at all, while stars similar to the Sun vary almost imperceptibly by a few parts per million over a timescale of minutes. Stars which vary by a few percent or more are said to be pulsating. The period (or periods) of their pulsations can reveal much about their internal density and structure, through the techniques of asteroseismology. The periods in UVO 0825+15 are between 10 and 14 hours and are much longer than is believed possible for a star of this size. Other explanations, such as surface spots, or reflection from a companion body, cannot explain the complicated light curve. A solution is still wanting.

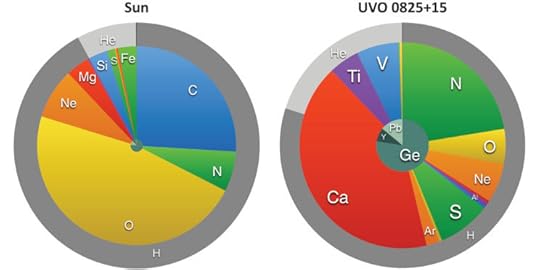

Pie charts comparing the surface chemistry of UVO 0825+15 with that of the Sun.The outer circles represent the relative abundances by number of hydrogen, helium, and all other elements. The middle circles represent the relative abundances of all elements EXCEPT hydrogen and helium. The innermost circles show only strontium, yttrium, germanium, zirconium, and lead. In addition to heavy metals, note the absence of carbon and very high abundance of calcium in UVO 0825+15. Image by Simon Jeffery. Used with permission.

Pie charts comparing the surface chemistry of UVO 0825+15 with that of the Sun.The outer circles represent the relative abundances by number of hydrogen, helium, and all other elements. The middle circles represent the relative abundances of all elements EXCEPT hydrogen and helium. The innermost circles show only strontium, yttrium, germanium, zirconium, and lead. In addition to heavy metals, note the absence of carbon and very high abundance of calcium in UVO 0825+15. Image by Simon Jeffery. Used with permission.The atmospheres of most hot subdwarfs are extremely hydrogen-rich, although their interiors from just below the surface down are mostly helium, which is converted to carbon and oxygen during a lifetime of 100 million years or less. Less than 10% of hot subdwarfs have helium-rich surfaces. With UVO 0825+15, four now show extreme overabundance of heavy elements, including zirconium, strontium, germanium, yttrium, and lead up to 10,000 times more abundant than in the Sun. We call these the “heavy-metal” subdwarfs. These four stars present yet another puzzle. The Sun is a well-behaved star which travels in a nearly circular orbit around the Galactic center, along with most other stars in the Galactic disk. In contrast, the heavy-metal subdwarfs have highly elliptical, high-velocity orbits. This implies that they are either very old, or have been given a kick. This might be a clue as to how, where, and when they were made, but we are still a long way from solving the puzzle.

The discovery of the fourth heavy-metal subdwarf is very exciting, especially because it is variable. It will help explore an important stage in the life-cycle of these very rare stars. But UVO 0825+15 has left astronomers scratching their heads. The surface chemistry – cloud layers of lead and yttrium – is amazing. But there is no clue to what causes the light variations, or why they seem to be so old.

Featured image credit: The author’s impression of the surface of UVO 0825+15, showing a very hot star covered by thin clouds of exotic elements, including lead. Image by Simon Jeffery. Used with permission.

The post Heavy-metal subdwarf appeared first on OUPblog.

The blinders of partisanship and the 2016 US election

America has just experienced what some claim is the most unusual presidential election in our modern history. The Democrats picked the first woman to run as a major-party candidate, while the Republicans selected an alt-right populist who is the first modern candidate never to have held an elected office. With battles in 140-character bursts, the tenor of the campaign was unusual to say the least; the final results surprised almost every election soothsayer and even the candidates themselves. However, was the voting outcome really a major deviation from normal voting results in the United States?

Political scientists describe a “normal election” as occurring when both campaigns are evenly matched in their appeals, and thus voters rely on their long-standing partisan identification to make their voting choice. Scholarship generally sees such partisan identities as a beneficial trait, because they provide voters with a cue on how people like themselves generally vote. Partisanship routinely is among the very strongest predictors of voting choice.

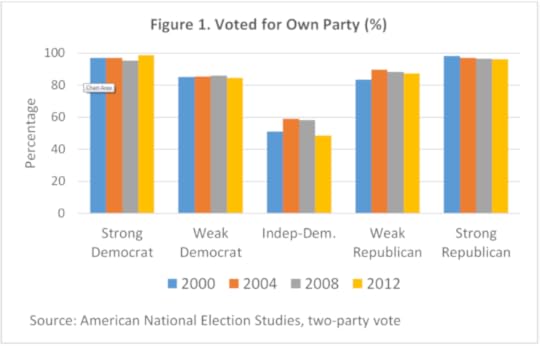

Every presidential election year, the American National Election Studies (ANES) asks Americans about their party loyalties and the strength of their loyalties, arraying them from Strong Democrats to Strong Republicans along a horizontal axis. Figure 1 shows what proportion of each partisan group voted for their own party (and of independents for the Democratic candidate).

The recent pattern of partisan voting by Russell J. Dalton. Used with permission.

The recent pattern of partisan voting by Russell J. Dalton. Used with permission. Hillary Clinton speaking at an event in Des Moines, Iowa by Gage Skidmore. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Hillary Clinton speaking at an event in Des Moines, Iowa by Gage Skidmore. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.From 2000 to 2012, the degree of party loyalty is striking. A full 97% of strong Democrats voted for their party across these elections, and 97% of strong Republicans did the same. It didn’t matter if the Democratic candidate was a white southerner with a long political resume (Gore in 2000), a liberal senator from New England (Kerry in 2004), or an upcoming freshman senator from the Midwest who just happened to be black (Obama in 2008). The same pattern exists among Republicans. Virtually all of the partisan groups voted more than 85% of the time for their own party’s candidate. It should also be noted that the Democratic vote share among independents is shown here. As you can imagine, they are more likely to change their voting preferences across elections.

The 2016 election seemed to challenge this conventional model of partisanship and voting. Hillary Clinton’s campaign targeted women, Hispanics, and gays more explicitly than any Democratic candidate in the past. Donald Trump supposedly appealed to a different type of Republican voter, and swung three major states from the Democrats’ blue Midwestern wall. The rhetoric of the campaign also seemed to test traditional partisan loyalties. In almost every way, this was not a “normal” election. Or was it?

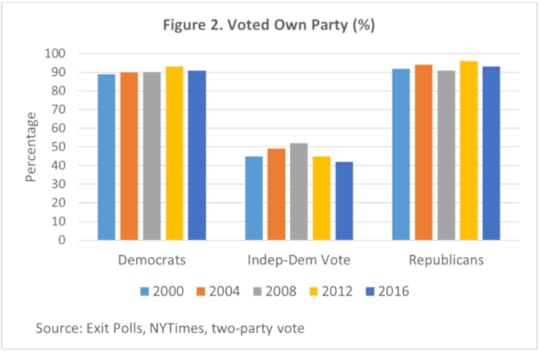

Results from the ANES won’t be available until spring 2017, and they’ll furnish the definitive evidence, but national exit polls from the last five elections provide useful data on the persisting impact of party identification (Figure 2).

Impact of party identification by Russell J. Dalton. Used with permission.

Impact of party identification by Russell J. Dalton. Used with permission.Even combining strong and weak partisans, Democrats and Republicans in the exit polls report virtually the same 90% level of voting loyalty across elections—and 2016 is no exception. Clinton wasn’t noticeably more successful in attracting crossover Republican voters, and Trump didn’t make major inroads in gaining disaffected Democrats. Electoral change occurred at the margins and among independents.

If the 2016 ANES shows these same patterns in its data, what are the implications for the study of elections? An important lesson is that popular interpretations of the 2016 election as a fundamental shift in political alignments—a white backlash, a populist movement for fundamental reform, or other media claims—ignore the more profound stability of voting patterns for most Americans. Pundits and the mass media focus on the unusual, but electoral change occurs at the margins of the major partisan divide. Thus, the president-elect’s claims of a large mandate for change are implausible, especially when Clinton outpolled Trump by nearly three million votes. Most partisans vote for their partisan team, rather than the coach, which dulls the policy mandate of elections.

A second lesson that comes out of all of this is the growing electoral significance of non-partisans. Independent voters have grown from a quarter of the public in the 1950–60s to two-fifths in the past decade. As both figure 1 and figure 2 show, independents are more likely to be swing voters who respond to the candidates and their campaigns. And the exit polls indicate that independents have trended away from the Democratic Party in the last two elections.

Finally, 2016 seems to highlight the limits of partisanship as a cue for reasonable voting choice. At the end of the campaign, most partisans came home to vote for “their party,” virtually regardless of the candidates. This is more impressive since party identities are so stable across elections. In normal times, party identification can be a valuable guide for voters. But partisanship can also become blinders that keep voters from seeing events and the candidates objectively. Effective partisan identities shape perceptions of events, networks of information, and, ultimately, voting choice. Democratic identifiers often ignored Clinton’s limitations, just as most Republicans discounted criticisms of Trump. The downside of relying on these cues is evident when party cues are not an accurate guide to one’s interests. The 2016 election may be a case in point.

Featured image credit: Donald Trump Signs The Pledge by Michael Vadon. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The blinders of partisanship and the 2016 US election appeared first on OUPblog.

A lost opportunity: President Trump and the treaty supremacy rule

Several commentators have noted that the election of Donald Trump poses a significant threat to the established international legal order. Similarly, the Trump election constitutes a missed opportunity to repair a broken feature of the constitutional system that governs the US relationship with the international order: the Constitution’s treaty supremacy rule.

A silent revolution in the 1950s created a novel understanding of the treaty supremacy rule. Article VI of the Constitution specifies that treaties are “the supreme Law of the Land; and the judges in every state shall be bound thereby, anything in the Constitution or laws of any state to the contrary notwithstanding.” The traditional supremacy rule was a mandatory rule consisting of two elements. First, all valid, ratified treaties supersede conflicting state laws. Second, when presented with a conflict between a treaty and state law, courts have a constitutional duty to apply the treaty. From the Founding until World War II, courts applied the treaty supremacy rule in scores of cases, without any exception for non-self-executing treaties.

Before 1945, lawyers distinguished between self-executing (SE) and non-self-executing (NSE) treaties. NSE doctrine arose because the Constitution empowers the President and Senate (the “treaty makers”) to make treaties that have the status of supreme federal law, without participation from the House of Representatives. Under traditional doctrine, NSE treaties required implementing legislation, but SE treaties did not. The doctrine restricted the President’s power to implement NSE treaties and preserved the House of Representatives’ ability to shape treaty-implementing legislation. The treaty supremacy rule governed the relationship between treaties and state law. NSE doctrine governed the division of power over treaty implementation between Congress and the President.

When presented with a conflict between a treaty and state law, courts have a constitutional duty to apply the treaty.

The United States ratified the UN Charter in 1945. Articles 55 and 56 obligate the United States to promote “human rights . . . for all without distinction as to race.” In 1945, racial discrimination was pervasive in the United States. Litigants filed dozens of suits challenging discriminatory state laws by invoking the Charter together with the treaty supremacy rule. In the landmark Fujii case (1950), a state court invalidated a California law that discriminated against Japanese nationals. The court held that state law conflicted with the Charter and the Charter superseded California law under the Supremacy Clause.

Fujii sparked a political firestorm. The decision implied that the United States had abrogated Jim Crow laws throughout the South by ratifying the UN Charter. That conclusion was unacceptable to many Americans at the time. Conservatives lobbied for a constitutional amendment, known as the Bricker Amendment, to abolish the treaty supremacy rule. Liberal internationalists resisted the proposed Amendment. They argued that a constitutional amendment was unnecessary because the Constitution empowers the treaty makers to opt out of the treaty supremacy rule by stipulating that a particular treaty is NSE. In short, they argued that the treaty supremacy rule is optional.

Before World War II, a firm consensus held that the treaty supremacy rule was a mandatory rule that applied to all treaties. Nevertheless, controversy over the Bricker Amendment gave rise to a new constitutional understanding that the treaty supremacy rule is an optional rule that applies only to self-executing treaties. Thus, modern doctrine holds that the treaty makers may opt out of the treaty supremacy rule by deciding—at the time of treaty negotiation or ratification—that a particular treaty provision is NSE.

The optional supremacy rule impairs the President’s ability to conduct foreign policy. For example, in Medellín v. Texas, President Bush ordered Texas to comply with US treaty obligations. The Supreme Court held that the President’s order was not binding on Texas—hence Texas was free to violate the treaty—because the contested treaty provision was NSE. Therefore, although the President and Senate made a binding commitment on behalf of the nation at the time of treaty ratification, and although President Bush attempted to honor that commitment, Texas subverted US compliance with a treaty obligation that binds the entire nation.

The optional supremacy rule is also contrary to the purpose of the Supremacy Clause. The Framers included treaties in the Supremacy Clause to preclude state government officers from engaging in conduct that triggers an inadvertent breach of the nation’s treaty obligations. Yet, as illustrated by Medellín, the optional supremacy rule empowers state governments to subvert US compliance with its treaty obligations—the precise outcome that the Framers thought they averted by adopting the Supremacy Clause.

If Hillary Clinton was nominating the next Supreme Court Justice, a new liberal Supreme Court majority might have repudiated the optional treaty supremacy rule and revived the traditional, mandatory rule. In contrast, the election of Donald Trump means that we are probably stuck with the optional treaty supremacy rule for the foreseeable future. Those who favor positive US engagement with the global legal order must chalk this up as another cost of the recent Presidential election.

Featured image credit: “The Supreme Court” by Tim Sackton. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post A lost opportunity: President Trump and the treaty supremacy rule appeared first on OUPblog.

January 8, 2017

The language of chess

The dust has barely settled on last year’s World Chess Championship match in New York: Norway’s Magnus Carlsen defended his title against the tough challenger Sergei Karjakin, in a close match. The event got me thinking about the language of chess strategy, and tactics, and the curious history, and multicultural origins of chess terminology.

Chess has been around for centuries and The Game and Playe of the Chesse was among the first books printed in English by William Caxton in the late fifteenth century. It is not actually a book of chess instruction in the modern sense. Rather it is an allegory of medieval society with a king, queen, bishops, knights, and rooks, and with pawns representing various trades. Each chess piece has its own moral code, together representing a kingdom bound by duty rather than kinship. Caxton used a French translation as the basis for his book and the English word chess is a borrowing from the Middle French échecs. But the story is older and more complicated than that.

Chess comes from the 6th century Sanskrit game chaturanga, which translates to “four arms.” The arms refer to the elephants, horses, chariots, and foot soldiers of the Indian army, which evolved into the modern bishops, knights, rooks, and pawns. The chaturanga pieces also included the king or rajah and the king’s counselor, which would later be reinvented as the queen. In chaturanga, the game ended when the rajah was removed from the board—when the king was killed.

Chaturanga was introduced to Persia around 600 AD and the rajah became the shah. Persian chatrang became Arabic shatranj and made its way to Morocco and Spain as shaterej. The word check, meaning an attack on the king, was adapted from the Persian shah. A player would say shah to announce an attack on the king. The expression checkmate came from the situation in which the king is attacked and has no defense: shāh māt means “the king is dead” and this connotation of regicide persists in the Russian name for chess: shakmati.

“Carlsen Magnus” by Andreas Kontokanis. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“Carlsen Magnus” by Andreas Kontokanis. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.In Latin, the game was not named after the killing of the king, but after the attacks themselves—the checks. It was called ludis scaccorum (game of checks) or, when shortened, scacchi. The Latin word for check later gave us the Middle French eschec, which became échecs in the plural and chess in English.

Along with the modern name, French is also the source of some of the game’s fine points, such as the en passant rule, which permits the capture of an opponent’s pawn when it moves two squares on its first move passing a pawn of the opposite color. It is the source of the expression j’adoube, used when a player wishes to adjust a piece without moving it. For a time too, players would announce gardez when the queen was under attack or en prise. But the warning is no longer customary.

French also contributes to the confusing noun stalemate. The Middle English word stale is probably from Anglo-French estale which meant “standstill.” When a player did not have a legal move, that counted as a win, so stalemate was a victory by standstill. Today a stalemate in chess counts as a tie, and the word has been extended to a more general description for a deadlock. En passant, j’aboube, gardez, and en prise have been less successful as general terms. The same can be said for the Italian word fianchetto, from the diminutive of fianco which means “flank” and referring to a particular deployment of one’s bishops.

German is the source of a number of chess words, such as Zugzwang, referring to the situation in which players have no moves that will not weaken their position Zugzwang has been extended to refer to situations in which the pressure to do something is counterproductive, as in the following examples from Zugzwang fan Nate Silver (from 2008: “Either way, it is a reminder of the state of zugzwang that McCain campaign finds itself in” and from 2016: “For Clinton, this is a zugzwang election where she’d rather stay out of the way and let Trump make the news”).

German gives us the monosyllabic term luft (“air”) referring to a flight square made by moving a pawn in front of a king’s castled position, which we find in Luftwaffe and Lufthansa, and the derisive patzer, used to describe a poor player (cognate with the verb patzen meaning to bungle). The German verb kiebitzen (“to look on at cards”) makes its way to Yiddish as kibitz and refers meddling in games by spectators.

Many modern tactical terms are of English origin. There are pins (when a piece cannot move because it would expose a more valuable one) and forks (double attacks), both terms dating from the nineteenth century. Twentieth century coinages include the windmill (when a rook and bishop work together to both check the king and capture material) and the x-ray or skewer, where a piece indirectly attacks an opposing piece.

One of my favorites terms though is the smothered checkmate, a term which dates from about 1800. This occurs when the king is surrounded by its own pieces so that it has no flight squares and is checkmated by an opponent’s knight. It is a rare occurrence but when it happens it will take your breath away.

Featured image credit: “Reflected Chess pieces” by Adrian Askew. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The language of chess appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers