Oxford University Press's Blog, page 421

January 8, 2017

A. R. Wallace on progress and its discontents

Celebrated for his co-discovery of the principle of natural selection and other major contributions to evolutionary biology, Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913) also wrote widely on the social, political, and environmental aspects of scientific and technological advance. These latter, if far less familiar, ideas constitute an astute critique of the Victorian concept of progress. Wallace was hardly alone among nineteenth-century thinkers in regarding scientific advances as ambivalent in terms of human progress. But most critics of scientific progress saw its problems in religious or aesthetic terms. Wallace’s critique was atypical in two respects. First, almost alone among the major scientists of the nineteenth, and very early twentieth, century, Wallace had profound misgivings about techno-scientific progress as an end in itself. Second, he embedded science deeply within both a sociopolitical and an environmental context and viewed science as a real and/or potential exacerbation of tensions in both of those settings. Today, on the occasion of Wallace’s birthday, I would like to highlight briefly some major facets of his critique of the ‘cult of progress’. His increasingly acerbic jeremiads against unregulated ‘progress’ resonate significantly with similar concerns in our own day.

Wallace’s prolonged residences in indigenous communities in South America and the Malay Archipelago during the periods 1848-1852 and 1854-1862 compelled him to question whether Europe had attained that pinnacle of social and moral development that its undoubted scientific and material progress rendered axiomatic to many Victorians. Similarly, a lecture tour of North America during 1886-1887 provided him with abundant evidence of the baleful effects of rapid industrial expansion in many regions of the United States. In North America, Wallace believed he had witnessed evolution run amuck: the cult of progress had triumphantly obliterated any constraints, ethical as well as socioeconomic. In response to these and similar experiences, Wallace developed a framework—from the seemingly disparate fields of evolutionary biology, geology, economics (especially land reform measures), socialism, and spiritualism—for analysing the socio-political and environmental consequences of techno-scientific change. Importantly, Wallace never sought merely a return to some imagined halcyon rural paradise of old. He “wanted to foster a thoroughly ‘modern’ ecological connection between man, nature, and the land”.

Title page of Wallace’s The Wonderful Century: Its Successes and Its Failures. Biodiversity Heritage Library. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Title page of Wallace’s The Wonderful Century: Its Successes and Its Failures. Biodiversity Heritage Library. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.In 1898, Wallace published the ironically titled The Wonderful Century: Its Successes and Failures. Here, he provided a sophisticated deconstruction of many of the icons of late nineteenth-century materialism. Wallace singled out nineteenth-century militarism as a first main target, especially as it has been augmented “by the application to war purposes of those mechanical inventions and scientific discoveries which, properly used, should bring peace and plenty to all, but which, when seized upon by the spirit of militarism, directly tend to enmity among nations and to the misery of the people”. But it is ‘the demon of greed’ that poses in Wallace’s mind a more immediate threat: the enormous and continuous growth of wealth in the Victorian era, without any corresponding increase in the well-being of the general population. For Wallace, it was not science itself but rather capitalism’s myopic deployment of scientific discovery and technology that distorted the industrializing world of the nineteenth century and gave the enormous increase of material productive power almost entirely to the “capitalists, leaving the actual producers of it—the industrial workers and inventors—little, if any, better off than before”. When to this cauldron of inequity is added “the enormous injury to health and shortening of life due to unhealthy and dangerous trades, almost all of which could be made healthy and safe if human life were estimated as of equal value with the acquisition of wealth by individuals,” it becomes clear why Wallace’s critique was so unpalatable to many late Victorian leaders and would be similarly disparaged by many in power today. One need think only of such climate change skeptics as President-elect Donald Trump and many corporate leaders to see the modern parallels.

In the final chapter of Wonderful Century, starkly entitled “The Plunder of the Earth”, Wallace ties environmental concerns directly to the bulk of social, political, and moral deficits of the nineteenth century. His arguments here are reflective of those other thinkers and activists who articulated a set of environmental concerns—including the decrease in natural resources, the fate of “sublime” wilderness, and increasing pollution—in Britain and the United States during the second half of the nineteenth century. But most such arguments proved feeble against the onslaught of the powerful forces of Victorian industrialism. Hopefully, Wallace’s critique of progress will find a larger, more receptive audience in our own day when the baleful cultural and environmental consequences of Victorian progress that Wallace perceived—especially the frenzied global attempt to adapt industry and agriculture to the demands of quick and ever-increasing profitability—are magnified enormously.

His belief that industry should be “restricted within the narrowest limits consistent with our own well-being” seemed subversive to many of his contemporaries who were not yet prepared to implement environmental legislation if it was politically or economically inexpedient. The problem was global: in “California, Australia, South Africa, and elsewhere … this rush for wealth has led to deterioration of land and of natural beauty, by covering up the surface with refuse heaps, by flooding rich lowlands with the barren mud produced by hydraulic mining; and by the great demand for animal food by the mining populations leading to the destruction of natural pastures…and their replacement often by weeds and plants neither beautiful nor good for fodder”. Moreover, according to Wallace, all “the labor-saving machinery and…command over the forces of nature that Victorian industrial capitalism” possessed had only made “the struggle for existence [in human society] more fierce than ever before”. Wallace’s critique of ‘progress’ is as—possibly more—potent today than it was at the close of the ‘wonderful century.’

Featured Image credit: Portrait of Alfred Russel Wallace published in Borderland Magazine, April 1896 by London Stereoscopic & Photographic Company. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A. R. Wallace on progress and its discontents appeared first on OUPblog.

Welcome to the year of living dangerously – 2017

I am not usually a worried man but today – New Year’s Day 2017 – I am a worried man. Gripped by an existential fear, my mind is restless, alert, and tired. The problem? A sense of foreboding that the impact of the political events of 2016 will shortly come home to roost on a world that is already short on collective good will or trust. There is also a sense that games are being played by a new uber-elite of political non-politicians who thrive on the vulnerabilities and fears of the masses – the great non-uber-elite (if that is not too many hyphens and too few umlauts).

And yet to suggest that this new elite thrives on vulnerability and fear is not quite correct. I am doing them a disservice. They do not just thrive on vulnerability and fear: they create and manufacture it.

Don’t believe me? Think I’m wrong?

Haven’t you noticed the new statecraft of ‘divide and rule’ that has arisen across large parts of the world? Have you not noticed the rise of national populism with its simple rhetoric of ‘us’ against ‘them’? When Trump says ‘Let’s make America great again!’ he isn’t just acknowledging the decline of a superpower but he is also implicitly blaming certain parts of society for that decline. When the Brexiteers campaigned for the UK to leave the European Union the debate was viciously polarized to the extent that anyone who dared to even question the benefits of a British departure risked being hung, drawn, and quartered as a traitor. I exaggerate for effect…but only slightly. Across the world there is a more of a hint and a kink of a psychological warfare in which sections of the precariat are pitted against other sections of exactly the same broad body of people who exist in a socio-economic state of uncertainty. These are the workers of the ‘gig economy’ – the apex of Bauman’s liquid modernity – who exist in a hinterland of self-employed temporary employment. Employment protection, workers rights, unions…little more than quaint phrases from a long-forgotten phase of economic development.

I don’t want to be told that foreigners, immigrants, and ‘others’ are the problem when I know that the problem is really one of ‘us’ not ‘them.’

It is the precariat – a phrase and focus of analysis originally developed by Guy Standing – who are living dangerously and their numbers are growing. As this slice of society grows from a thin seam to a major layer of the social structure, then so too do the opportunities for abusing the existence of obvious social fears and frustrations. It is easy to divide a vulnerable class, a hopeless class, a hopeful class, and for false prophets to promise the world in return for a vote. Too easy, and this is the problem with democracy that has now emerged.

I don’t want a red cap or a Union Jack. I don’t want to be told there are simple solutions to complex problems. I don’t want to be told that foreigners, immigrants, and ‘others’ – those demonized souls – are the problem when I know that the problem is really one of ‘us’ not ‘them.’ My foreboding is therefore based on a sense that the public (or really ‘the publics’ of the modern world) have been manipulated by false fears that will only generate new fears and isolationism at a historical moment when the fears and risks that really matter can only be confronted through united collective action.

I may be completely wrong. The year 2017 may go down as one defined by a move towards broad sunlit uplands; or one defined by a new dark age made more sinister by the perils of populism unconstrained and misunderstood. So let us brace ourselves for a rough ride and tough times that will go far beyond Trump and Brexit. General elections this year in the Netherlands, Germany, and Italy may lead to significant gains for the Party for Freedom, the Alternative for Germany, and the Five Star Movement, respectively. But it is in France where the real test will come. This is a country where the standard of living has not fallen and where levels of social inequality have generally been kept in check, and yet where the right-wing National Front may also gain significant support in the presidential elections. How? Through the manufacture and manipulation of fears and vulnerabilities.

During 2016 complacent governments around the world created a political void that was quickly filled by populist parties. In 2017 war and poverty will continue to drive displaced peoples towards Europe – the most precarious of the precariat – but national populism will splinter and fragment the shores upon which the tired and hungry collapse. Sand and blood, such an ugly phrase that captures my sense of foreboding….

Listen to my chronicle of a death foretold. Welcome to the year of living dangerously.

Featured image credit: leaping ocean jump by skeeze. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Welcome to the year of living dangerously – 2017 appeared first on OUPblog.

January 7, 2017

Reimagining equity in public schools

Fifteen years ago bipartisan support for No Child Left Behind (NCLB) served as a watershed moment in federal support for public education in the United States. The law emphasized standardized testing and consequences for states and schools that performed poorly. The law was particularly important because NCLB’s focus on accountability also meant that states and local school districts were required to report on the achievement of different groups of students by race, socio-economic background, and disability. Assessments also focused on the achievement of English Language Learners. Many would argue that the law is credited with helping to expose achievement gaps between different groups of students, and it has been more difficult to ignore the education of underserved students across the nation. Thus, it has been argued that all students should have the resources necessary for a high-quality education. But the truth remains that some students need more in order to flourish, and race should not determine school funding. As Alan Singer (2016) recently observed in a blog post, “Kids and schools that need more would get more.”

The assumptions underlying NCLB and now the Every Child Succeeds Act (ESSA) remain open as does the question of whether equal educational opportunity (as opposed to equal educational outcomes based on test scores) remains the civil rights issue of our time. One cannot ignore that president-elect Trump has called school choice the civil rights issue of our time and has chosen a school-choice advocate as his Secretary of Education whose approach to education threatens to erode funding for public schools. Similarly, it is hard to overlook an Appellate Court ruling in Michigan stating that the law does not require an equitable distribution of resources to public schools. This ruling echoes San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez, which in 1973 found that there is no constitutional requirement to ensure schoolchildren actually learn fundamental skills of literacy. As in the case in Michigan, the court ruled in 1973 that the state is only obligated to establish and finance a public education system, regardless of quality.

It is more urgent than ever before to revisit the nature of school reform and equity in poor communities where multiple social and economic factors have a detrimental effect on student life and performance. Fortunately, the Connecticut Supreme Court in Connecticut Coalition for Justice in Education Funding v. Rell has challenged the formula for funding public schools, but the State is challenging a ruling that has the potential to bring about equitable funding in schools. There have been dozens of school funding lawsuits across the country that represent an ongoing debate about who is responsible for funding public education, whether it should be equitable, and the legal mandate to ensure that all kids have access to the kind of literacy instruction that would enable them to be active participants in a democracy.

The 8 January, 2017 is the fifteenth anniversary of NCLB, so it is worth revisiting NCLB’s promise to address the needs of historically underserved students. Schools are resegregating, (e.g. Kozol, 2005), students living in poverty are socially isolated in schools located in the nation’s poorest neighborhoods, and funding is inadequate. The reality is that many students are left behind and do not have access to the kinds of opportunities to participate in a democracy as citizens who might be better positioned to navigate the very policies and laws that have historically marginalized students of color.

President George W. Bush discusses NCLB at an elementary school in Washington, D.C., October 2006. White House photo by Paul Morse, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

President George W. Bush discusses NCLB at an elementary school in Washington, D.C., October 2006. White House photo by Paul Morse, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Ladson-Billings (2006) has usefully reframed the perceived gaps in educational achievement for black, Latinx and other underserved students as an education debt. Such a view calls attention to the historical circumstances that left many young people without the resources they needed to flourish as educated citizens in an era of Jim Crow and that still has a considerable impact on underserved students in segregated, underfunded schools. This debt also manifests itself in the lack of power and voice in families’ ability to participate in the governance of schools that determine policies, curriculum, class assignment, and discipline. Unfortunately, NCLB placed responsibility for achievement in under-resourced schools and, in doing so, shifted attention away from social, political, and economic problems surrounding, outlining, and running through such schools. The same holds true for those who embrace school choice, which fails to address the devastating effects of neo-liberal policies on inner cities throughout the United States. It is not trivial to observe that race matters in discussing policies that affect children’s life chances. And this means confronting what the authors of the Schott Foundation for Public Education report (2015) describe as an “insurmountable chasm of denied educational opportunities” for youth of color who find themselves mired in a school-to-prison pipeline.

Altogether, disproportionality in suspensions and drop-out rates are at odds with the accountability principle in NCLB based on the concept of ensuring the adequacy, progress, and educational outcomes for all students. Indeed, the promise of NCLB in 2002 was to ensure that all racial and ethnic groups achieve 100% proficiency in reading and math. But researchers have found that there has been little oversight to ensure that all racial and ethnic groups have reached the benchmarks set out by NCLB, and these benchmarks vary from state to state. Such a finding again brings to light the question of whether or not education is a civil right and if ESSA—linked philosophically to NCLB as it is—can adequately address the unequal distribution of resources (e.g., highly-qualified teachers, curriculum) that mark the educational experiences of different students.

To reinvigorate the notion of equity and re-imagine schools, it is important to underscore (a) the equitable distribution of material, emotional, and economic resources to ensure that children have the capacity to direct the course of their own lives in healthy, safe environments in and out of school; (b) the value of inclusion in making critical decisions about the processes underlying the distribution of these resources; (c) the importance of developing measures of assessment that account for what it means to teach for social justice and challenges the limits of assessment rooted in the nation’s economic well being; and (d) the need to leverage the law to center justice as a value in education.

In the end, education as a civil right acknowledges the power inherent in education, promotes inclusion, and values an asset-based approach to education that acknowledge the worth of all children.

Featured image credit: Atlantic Express school bus in New York City, 2009. Photo by flickr user mickamroch, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Reimagining equity in public schools appeared first on OUPblog.

Learning from each other

Here on the blog we have talked about the value of oral history in preserving spaces and memories, its importance in social change, and the work that goes into producing and presenting quality oral history projects. Throughout January we are focusing on educators who are using oral history in the classroom, and its transformative potential. Below we hear from our own Troy Reeves and students from his First-Year Interest Group (FIG) class on oral history and food production in Wisconsin. Make sure to check back in two weeks when Abigail Perkiss will join us to talk about her article in the most recent OHR and the profound changes she saw in students. If you are interested in contributing your own pedagogical experiences and insights email our blog editor, Andrew Shaffer, or Abigail Perkiss, Pedagogy Editor at the Review.

Fate intervened this summer, giving me the opportunity to teach a History 201 class this fall at UW-Madison. Over the course of fifteen weeks I instructed 15 first-year undergraduates about oral history. They all conducted a recorded audio interview and wrote a “Labor Portrait” – think Studs Terkel’s Working. In the end, as I hoped, I learned as much from them as they did from me.

At the end of the class I asked the students to think back on what they had learned. Below are a handful of excerpts from their reflections that give a glimpse into the transformative potential of oral history. They are as diverse and distinct as the students themselves, and I am grateful for the opportunity to have met and worked with such a fantastic group of human beings.

For one student, the class helped to forge connections between his disparate identities, connecting his childhood to his life as a college student.

It’s tough to say who I am, because I have always been constantly changing as a person. I have different accents, mannerisms, and even beliefs based on who I am surrounded by. Sometimes I am Mario Carrillo, the goofy nerd who enjoys reading old political books and drawing cartoons. Sometimes I am “Mah-yo Carreeyo,” a strong-willed Mexican kid who would rather see change out in the streets rather than in a classroom. I found that my time here at UW-Madison has challenged these two identities of mine. I am from the Illinois Rust Belt, a place where the atmosphere tastes like aluminum and ash. A place where hard work was valued more than your brain, which is something I’ve always struggled with.

I was a little afraid of what my parents would say about my choice of this FIG. After all, I was here to learn skills necessary to never again experience poverty, and a political science degree itself isn’t exactly a competitive degree. But taking this class reminded me of issues I faced as a kid. Even the narrator I chose reminded me of my own father: they both were Mexican immigrants who got their first jobs as low paid restaurant workers. I feel he has a story that is more common than it should, but it is the cultural barrier that stops American society from truly empathizing.

– Mario Carrillo

Students from Troy’s History 201 class along with guest speaker Paul Ortiz. Not pictured: Mario Carrillo, Annika Hendrickson, and Troy Reeves. Used with permission.

Students from Troy’s History 201 class along with guest speaker Paul Ortiz. Not pictured: Mario Carrillo, Annika Hendrickson, and Troy Reeves. Used with permission.Some students latched onto the ability of oral history to amplify voices that rarely get an audience.

The woman I chose to interview is a type of worker that doesn’t often get a lot of credit. She works in the dining hall and is a student so her position is often overlooked and gone un-thanked. So I thought it would be nice to give her a voice.

– Annika Hendrickson

I chose my narrator because we had previously had conversations about work, and he seemed very opinionated on issues of workplace climate and the tipped wage. I also knew a bit about his life before coming to Madison and thought he had a story worth telling.

– AJ Hirschboeck

For some students, the class helped them see how history is constructed, and to see their own lives as a part of history.

The class certainly expanded my perspectives on a variety of topics, from destroying any misconceptions about history to all the social movements occurring today and the complicated commodity chains that put food on shelves.

– David Chen

I want to get more involved on campus to be a part of something and I hope that one day, a student will interview me and I will be in the UW Archives.

I wanted to have some information before choosing a person to interview so I went to the UW Archives to look at materials. I kept stumbling upon one person’s name over and over again, so I shot him an email and he was very willing to meet with me. At the time of the interview, I was in my first semester as a freshman at UW Madison. I absolutely love this school and I am very excited for next semester, next year, and all of the education I will get until I graduate. I want to get more involved on campus to be a part of something and I hope that one day, a student will interview me and I will be in the UW Archives.

– Stephanie Hoff

I never realized how much more there was to history besides multiple choice tests on wars. Although the interview was stressful, it was easily my most fun assignment that I had all semester. This class has even made me consider working for my local newspaper over the summer where I could conduct interviews with people and write articles.

– Madeline Kallgren

Some students saw the potential of the interview to make and improve relationships, building meaningful connections with people inside and outside of their communities.

I chose my narrator because Slow Food was a place that I really wanted to visit, but I could never muster up the courage to go alone and volunteer. So, I used this project as a way to get to know the people of slow food. I’m glad I did that because I was able to meet some really awesome and welcoming people. I’m also glad that I chose to be a part of this FIG because I got to meet some really cool people out of it.

– Yesha Shah

I chose my narrator because I had developed a good rapport with him before I even knew I was going to interview him. We are from the same country originally and I was interested in his story about his life in Madison as a fellow Indian. Oral history was the best to find out.

– Tanvi Tilloo

I may be a bit biased, but I agree – oral history is the best way for us to find out about each other, and to build connections. Teaching is exhausting, and grueling, and occasionally monotonous, and so damn worth it because it has allowed me to connect with some incredible people and to continue preaching the good word of oral history.

Want to contribute your own pedagogical insights or inquiries? Contact our social media coordinator, Andrew Shaffer, at ohreview@gmail.com to talk about writing for the blog. Add your voice to the conversation in the comments below or on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, or Google+.

Featured image: “Classroom.” by MIKI Yoshihito, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Learning from each other appeared first on OUPblog.

January 6, 2017

Zika virus: a New Year update

The Zika virus (ZIKV) is a mosquito-borne virus originally discovered in the Zika Forest area in Uganda in 1947. It was not considered a relevant pathogen for humans until the outbreaks of fever illness that occurred in the Pacific area in 2007, and later in 2013-14. However, it was its arrival and dramatic spread in Brazil and other Latin American and Caribbean countries that alarmed public health authorities and the scientific community. Increasing evidence pointed to a link between the Zika virus and foetal microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome, a rare condition in which the immune system attacks the nerves. This prompted the World Health Organisation (WHO) to declare ZIKV a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on 1 February 2016. In response to this emergency, research on ZIKV was intensified, and within a few months, large amounts of data and outstanding results have been produced.

Zika virus belongs to the genus Flavivirus, which includes other vector-borne viruses, like dengue virus and West Nile virus. Phylogenetic analysis has shown a close genetic similarity of ZIKV with dengue virus and has identified viral strains of the Asian lineage as responsible for the current epidemics. The virus is predominantly transmitted between humans through the bite of an infected mosquito, mostly of the species Aedes aegypti, but other modes of transmission have been identified, including trans-placental transmission between expectant mothers and their babies. Prolonged shedding of infectious virus in semen and in vaginal fluids and efficient viral replication in vaginal mucosa explain the ability of ZIKV to be transmitted sexually, a unique feature among flaviviruses. Recent experimental infection in mice also showed that the virus persistently infects peritubular cells and spermatogonia, induces inflammation in the testis and epididymis that leads to male infertility. Moreover, the virus was detected by immunohistochemistry in spermatozoa from a patient with acute infection.

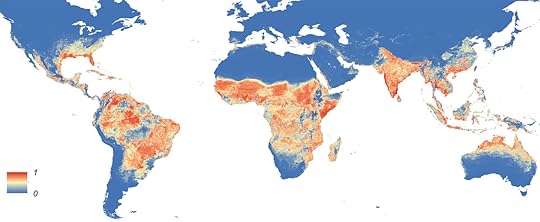

Global Aedes aegypti distribution. CC0 1.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Global Aedes aegypti distribution. CC0 1.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Guillain-Barré syndrome was identified to be a very rare neurological complication, reported in about 1-3 out of 10,000 infections. The incidence of foetal demise, microcephaly, or other congenital anomalies is still unknown, and has been estimated to range from 1% to 20%, higher during the first trimester of pregnancy.

The structure of key ZIKV proteins has been characterized and could be exploited for the design of vaccines, therapeutic antibodies, and antiviral drugs. In vitro models and in vivo mouse and non-human primate models of ZIKV infection have been set up and used to investigate virus transmission, tropism, neural damage and teratogenicity, and to test the immunogenicity and efficacy of vaccines. These studies allowed us to clarify important mechanisms of ZIKV neuro-pathogenesis, such as the identification of neural progenitor cells and placental macrophages as targets for ZIKV infection in the human brain and in the placenta, and the demonstration that ZIKV efficiently counteracts the innate antiviral response in humans.

Similarly to other mosquito-borne viral infections, like West Nile fever and dengue fever, ZIKV disease is characterized by a mild fever, rash, and arthralgia, making it almost undistinguishable. Because of this, during the acute phase of infection, diagnosis must rely on molecular testing from blood, urine, or saliva, while serology testing may be inconclusive due to the cross-reactivity of antibodies with other flaviviruses. This represents a serious problem for the diagnosis of infection in people who reside in ZIKV endemic areas, where other flaviviruses, like dengue virus and yellow fever virus, generally co-circulate.

The strong genetic and structural similarities of ZIKV to other flaviviruses poses a challenge not only to the differential diagnosis, but also to vaccine development, because antibodies induced by a previous flavivirus infection or vaccination may worsen a subsequent infection with a heterologous flavivirus through a mechanism of antibody-mediated enhancement.

Nonetheless, some vaccines against ZIKV have been developed and are in the process of clinical trial evaluation. In addition, drug repositioning screenings have identified some molecules that inhibit ZIKV infection and replication, while genome-wide screenings have identified certain human genes that are essential for ZIKV to replicate in the body, which could hold answers for finding effective antiviral therapies.

Several questions still remain open, such as how the virus infects and interacts with mosquito and human cells; which are the key genetic and molecular determinants of pathogenesis; how long the virus persists in human blood and tissues and its transmissibility; and how the innate and adaptive immune responses can counteract the virus and protect from reinfection. The responses to these questions are crucial, in this New Year and the future, to developing new antiviral medicines and improved protocols for ZIKV control.

Featured image credit: Zika virus 3D by Manuel Almagro Rivas. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Zika virus: a New Year update appeared first on OUPblog.

Do you have what it takes to lead a community choir?

Community choirs bring people of all ages together, uniting through song and shared purpose. People have different motives for singing in a group: to try something different, to explore a new skill, to find company and a sense of belonging, to improve health and well-being, to make a contribution, to feel valued. The motivation might be musical, personal, both, or more. A good community singing group will welcome everyone and take them all forward together, matching the musical activity to the expectations of its members. The priorities are enjoyment, learning together, being inclusive, and achieving success — culminating in a performance, if desirable.

Running a community choir requires good leadership. A community choir leader should win trust, demonstrate empathy, have a clear purpose, set expected behaviours, and teach skills that everyone can develop. Expectations should be high but achievable, and leaders must inspire with passion and confidence to create a team spirit. An open mind is essential; everyone has something to offer. A leader’s approach to challenges must always be positive.

A community choir leader has to engage people quickly, and every session needs to help members feel fulfilled and successful. Physical activity is always a good icebreaker and establishes the social bonding that is essential to good group singing, so action songs and warm up games are invaluable. Once the atmosphere is comfortable and singers are focused, then it’s time to step things up and start the singing.

Community choir members bring different expectations and abilities to a session, so work has to be paced carefully to keep everyone on board, challenging them to improve without demoralizing or frustrating anyone. It’s a delicate balance, and a good leader with the right singing material will achieve this, using praise and positive responses to keep spirits high. A ‘can do’ attitude is essential!

I recently led a workshop with singers who mostly belonged to a choral society (which gives formal performances of major choral works, with most members reading music), and a few who didn’t usually sing at all. Participants had little or no experience of singing gospel music or learning by ear (i.e. without music). As with all singers new to singing in a community choir, some things I asked them to do were outside their comfort zone; moving and singing with actions, learning a round – encouraging greater vocal independence – and tackling a gospel song. Many community choirs meet regularly and develop skills and confidence over time; this group managed a fairly secure ‘performance’ in just one session.

Watch this short video of excerpts from the workshop.

The success of this approach is down to good pacing via small steps and the choice of very accessible simple repertoire that has the potential to develop over time. Suitable pieces are ones which are flexible enough to cater for any type of group. Community choir leaders need to find repertoire with adaptable parts which is accessible to all – hence African welcome songs, silly rounds, gospel songs, and spirituals, all of which feature few words, simple harmonies, and much repetition in the melody lines.

Singing is one of the quickest routes to social bonding and a feeling of shared endeavour. This explains why community groups are immensely popular and provide invaluable support (and even health benefits) to so many people. Leading such a group is exciting and rewarding. You’ll learn a huge amount about how best to communicate your enthusiasm and passion, and how to motivate others. Get passionate, be an advocate – try it!

Featured image credit: St Christopher’s Community Choir. By Garry Knight. CC-by-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Do you have what it takes to lead a community choir? appeared first on OUPblog.

How much capital?

Almost a decade after the global financial crisis, most regulators and commentators would agree that the banking industry is far more strongly capitalized than it was in the run-up to the crisis. Looking forward, there is less consensus as to how much capital banks should hold. Neel Kashkari, head of the Minneapolis Federal Reserve, attracted attention recently by calling for huge increases in minimum capital requirements for banks. At the other extreme, the election victory of Donald Trump has raised hopes on Wall Street of a significant relaxation of financial regulation.

A bank’s capital is the difference between the value of its assets and its liabilities. Capital acts as a buffer, enabling banks to absorb unforeseen losses in the value of their assets. Examples of unforeseen losses include a borrower defaulting on a loan, or a sudden decline in the value of an investment. The more capital a bank holds relative to its assets, the lower the risk of the bank becoming insolvent because its assets have dipped in value below its liabilities. However, the need to maintain a target ratio of capital to assets constrains the bank’s ability to write new profit-earning business, through additional lending or investment. A bank’s senior management team faces a conflict between profitability and minimizing the risk of becoming insolvent.

Over the past 30 years regulators have cooperated to develop a set of rules to ensure that banks hold sufficient capital, under the auspices of the Basel Committee at the Bank of International Settlements in Basel, Switzerland. Capital regulation for banks was introduced in 1988 under the Basel I Accord, which required internationally-active banks to maintain a capital ratio of at least 8% of assets adjusted for risk. Basel I was easy to understand and transparent, but focused solely on credit risk: the risk associated with borrowers defaulting on loan repayments. Several other sources of risk to the solvency of banks were completely ignored.

The assessment of risk was extended by Basel II, launched in 2006, to include market risk: the risk of losses on bank’s investments in securities and other assets; and operational risk: the risk of losses arising from failure on the part of a bank’s staff (‘rogue trader’ syndrome) or internal processes and systems. The focus was on capital as a proportion of risk-weighted assets, where different classes of asset used in the denominator of the capital-to-assets ratio would be weighted in accordance with the risk they carried. Basel II was overtaken by the global financial crisis and was never fully implemented. In response to the crisis Basel III introduced further modifications, including new capital and liquidity standards to be phased in between 2013 and 2019. Definitions of capital have been overhauled, to strengthen the banks’ loss-absorbing capacities. Banks and other financial institutions deemed to be ‘systemically important’ are required to hold additional capital.

Pound coins currency by stux. Public Domain via Pixabay.

Pound coins currency by stux. Public Domain via Pixabay.During the phase-in period of Basel III, all major banks have significantly increased their risk-weighted capital-to-assets ratios. However, regulators worry that the current framework allows banks too much discretion in measuring the riskiness of their own assets. A number of proposals for change have emerged, dubbed unofficially by some commentators as ‘Basel IV’. These proposals suggest revisions to the measurement and management of risk, and restrictions on the use of banks’ internal models to quantify risk. For example, internal models might be required to adopt minimum default probabilities for loans. Standardized risk-weightings might be applied to assets in a given category, such as mortgages, regardless of local market conditions.

European and Japanese banks, among the heaviest users of internal models for risk assessment, have been among the most vocal in lobbying against these proposals. It has been argued that, perversely, by increasing the risk weightings attached to lower-risk assets such as mortgages, and thereby reducing the sensitivity of capital requirements to risk, the proposals may encourage banks to shift towards riskier lending in search of higher returns.

If implemented, the impact of the proposals may differ widely between banks in different countries. In the US mortgage defaults are common, but many residential mortgages are sold by the banks to the government-sponsored enterprises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. This suggests US banks would not be greatly affected by the proposed changes to risk weightings. In any case, US banks argue that they were faster on their feet than others in putting their house in order after the global financial crisis, by recapitalizing, reducing lending, and eliminating non-performing loans from their books.

In many European countries, by contrast, residential mortgage defaults are rare, and the adoption of standardized risk weightings in the calculation of risk-weighted assets may increase significantly the amounts of capital some European banks would need to hold. The prospect is alarming for several banks, such as RBS, already struggling to pass stress tests conducted by national or international supervisors to demonstrate their resilience in the face of hypothetical unforeseen losses. Negotiations around the proposals have been tough and seem likely to continue throughout the year, missing a self-imposed target of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision to sign off on the new standards by the end of 2016.

Featured image credit: rainbow of credit by frankleleon. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post How much capital? appeared first on OUPblog.

January 5, 2017

Comprehensive affordable solutions to a major health problem

Alcohol and drug abuse costs Americans approximately $428 billion annually. Despite this enormous cost—which, we must remember, is just the economic face of a community, family, and individually life-shattering problem—the vast majority of those with an alcohol or substance use problem do not receive treatment, and even fewer are likely to achieve long-term sobriety. In short, the existing system is characterized by inadequate access, high recidivism, and recurring treatment—at best, an ineffective and expensive revolving door. It has become increasingly clear that detoxification and treatment programs are insufficient to ensure abstinence from drugs and alcohol; for most people with substance use disorders, continued longer-term support following treatment is necessary.

When people leave formal treatment, ranging from a few days of detoxification up to perhaps several weeks at a specialized facility, they need a safe place to live and a job or someone willing to support them. Many of them have social networks of friends and family members who are abusing substances and may also be involved in illegal activities, and not surprisingly, such influences are harmful. Most will return to the same patterns that brought them into jail or treatment. What is needed is low cost but effective ways of changing the persons, places, and things that once surrounded users, replacing them with individuals who do not abuse alcohol and drugs, and who are employed in legal activities. Yet, how to affect this transformation in our substance use field is our greatest challenge, particularly in an era characterized by limited resources from local, state, and federal government.

Substance abuse treatment programs, perhaps recognizing their own limits in terms of both objectives and cost, have gradually moved to ever briefer formal programs, to be followed by “aftercare”. This kind of model arguably makes a good deal of sense: experts are indeed needed to provide the intensive medical and psychological services required in early recovery. Unfortunately, without aftercare, the majority of treatment recipients relapse; yet little or no attention is given to aftercare systems which actually meet the needs of individuals coming out of treatment. More typically, one receives little more than a referral to Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) or Narcotics Anonymous (NA). Participation in such groups can be beneficial for some, but cannot begin to address the range of issues faced by the newly sober, including employment and residence difficulties, broken social relationships, and the inevitable temptation of one’s pre-treatment associations and activities. It is thus not especially surprising that so many individuals soon return to previous habits. The revolving door keeps on revolving.

Alcohol Warning, Cape Town, South Africa by Victorgrigas. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Alcohol Warning, Cape Town, South Africa by Victorgrigas. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.In the continuum from initial problematic behaviors to substance use disorder recovery, several key transition points appear to have significant overall leverage on outcomes. Assuming a treatment seeker is able to get into a program—no mean feat—he or she is still unlikely to end up on a path that leads to recovery. The lack of well thought-out, effective, and affordable aftercare represents both an enormous opportunity cost (especially in light of the difficulty of obtaining any kind of treatment to begin with) and a real cost to the service system. Available research (some of it conducted by our research team) has found that, indeed, effective aftercare is a a critical leverage point for improving individual recovery outcomes and reducing costs.

Community-based solutions include recovery homes, where individuals can support each other in creating new, sober lifestyles. Mutual help systems can facilitate the increase of supportive network density by affording individuals access to like-minded others who all know each other and interact regularly and intimately, and for whom personal transformation is an ongoing objective. Environmental factors are key contributors to maintaining abstinence after treatment, and the broader goal of a fundamentally different lifestyle. These factors include the amount and type of support one receives for abstinence. For example, we can learn from those settings like self-run Oxford House recovery homes, with a network of over 2,000 houses across the country. There are no professional staff in Oxford Houses; these self-help settings are thus inexpensive to develop and affordable for residents, who only need to pay about one hundred dollars a week to live in them, providing former substance abusers places to live for unlimited amounts of time, surrounded by new peer networks that do not use alcohol or illicit substances. Studies by our group and others have consistently found that individuals who participate in these types of aftercare services sustain abstinence for longer periods of time.

We need to find more systematic ways to help individuals in dealing with substance use disorders, whether they are in corporate America, in jails or prisons, or living on the streets. The answers to such questions all lie in a the comprehensive study of systems that attempt to refashion personal networks to support better opportunities for recovery. Changing social networks that are dominated by users and those engaging in illicit activities to ones that involve abstinence and legal activities is our challenge. There are multiple community-based organizations, like Oxford House, that represent system-level evolutions, and approaches could contribute to reducing health care costs by improving the effectiveness of our substance use treatment system in the United States, which could help us creatively think of ways to restructure and improve other health-oriented settings.

Featured image credit: Ismerős gyilkos: Paul at an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting by Lwp Kommunikáció. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Comprehensive affordable solutions to a major health problem appeared first on OUPblog.

From Willie Horton to Donald Trump

He is stupid and lazy. He has the attention span of a child. He caters to racism and he does not respect women. His patriotism is juvenile and belligerent. He claims to have the common touch, but he truly cares only for the rich.

Is this the standard bill of indictment against Donald J. Trump, circa 2016—or against Ronald Reagan, circa 1980? Of course, these charges were made by liberal opponents of each. Many were made of George W. Bush as well: they form a well-worn package of accusations that have stuck to almost every successful Republican presidential aspirant since the Watergate crisis of the 1970s. To Democrats and progressives, this is what popular Republican politicians are like. This is not just a potentially devastating set of charges, but also, ironically, a conservative formula for winning.

Some of the claims about each man were supported in fact, while others were merely self-serving liberal insults. Trump’s harsh anti-Mexican nativism and his Islamophobia, like his alarming relationship with the neofascists who call themselves the “alt-right,” represent a true break from anything purveyed by Reagan or the second President Bush (although each of those men had things to answer for in their appeals to white resentment, their preferential treatment of the rich, their callousness toward the poor, and their scant concern for the human cost of war).

Yet of all recent Republican standard-bearers, the one whose presidential campaign stands out as the most shockingly exploitative and hateful is the one who figures least of all in liberal narratives of Republican moral decline. That is the first President George Bush.

George H. W. Bush, rejected in his bid for a second term in 1992, is the only post-Watergate GOP president who did not excite the full list of outraged condescensions provided above. In a way, Bush I is the key to understanding the steady recipe for Republican presidents in our age, precisely because his fractured popularity makes him stand out from the rest. The elder Bush’s greatest political success was the grossly race-tinged campaign that he ran in 1988, which elevated him to the Oval Office. Battling the “third-term curse” that inhibits one party from holding the White House for twelve years running, Bush, after Reagan’s two terms, knocked the political system on its side—and knocked his Democratic opponent, Michael Dukakis, to the canvas.

Chief Justice William Rehnquist administering the oath of office to President George H. W. Bush on 20 January 1989 at the United States Capitol. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Chief Justice William Rehnquist administering the oath of office to President George H. W. Bush on 20 January 1989 at the United States Capitol. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Bush set new terms for the contest. Instead of debating the mixed economic legacy of Reaganomics and the increase in poverty, homelessness, and inequality that the policies of the 1980s produced, the candidates in 1988 jousted over who was a more determined foe of rapists and murderers, and whose patriotism was purer.

Bush made “Willie” Horton—who fled a prison furlough and raped a Maryland woman while serving time in Massachusetts for murder—the centerpiece of his presidential bid. Widely circulated photographs insured that all Americans were reminded Horton was black. The fact that the woman he assaulted was white was, it seemed, universally understood. Far from shying from this particular case because of the incendiary potential that lay in these details, the Bush campaign appeared drawn to the story, partly for this reason.

The other major campaign issue for Bush was his charge that Dukakis was unpatriotic because, as Massachusetts governor, Dukakis had vetoed a rather plainly unconstitutional bill that would have required public school teachers to lead children in the Pledge of Allegiance (members of minority churches were the teachers likeliest to object; Bush was not greatly concerned over their religious liberty). Dukakis—nearly struck dumb by Bush’s tenacious and successful effort to make the Democrat the candidate of rapists and flag-burners—became political road-kill.

Surely we also should remember that Bush’s record of governance as president was more moderate, in many areas, than Reagan’s had been. Bush was less hostile to environmental regulation than Reagan had been, and he signed the Americans with Disabilities Act. Most of all, his willingness to tack toward the center on tax policy, in order to close a gaping public debt, cost him greatly in Republican support. When he appealed to the voters, Bush’s main political vulnerability lay in his image as an effete aristocrat. His elitist persona was linked to his uncertain conservative credentials. To conservatives, Bush’s policy equivocations reflected his poor connections to the salt-of-the-earth taxpayers whose hostility to the welfare state welded them to the political right. Bush escaped his upper-crust identity briefly with his coarse 1988 campaign, but it lingered, and was turned against him skillfully by Bill Clinton four years later. Because Bush lacked the common touch, he gravitated toward harsh campaign themes and tactics in 1988, in order to compensate for this deficit—as if to prove that he was a true conservative who could touch the movement’s heartstrings. In a way, Bush provided the strongest validation of the liberal claim that the secret of conservative popularity was an appeal to primal fear and base prejudice.

One point of information that reveals George H. W. Bush’s importance as a transit point on the Republican journey from the Nixon era to the Trump moment is the role of media guru Roger Ailes in the campaigns of all three men. Ailes, who led Fox News in its meteoric rise in between 1988 and 2016, was always the maestro of hot-button appeals that divided the electorate in ways that redounded to Republican advantage. He was Nixon’s main media adviser in 1968, when he effectively used the issue of law and order in a time of turmoil, and he played the same role for Bush in 1988, pressing the crime issue into newly charged territory. In 2016, Ailes had a less certain role in Trump’s campaign, but Trump’s bold statements of sympathy with Americans who fear Mexicans and Muslims were in the Ailes tradition. That tradition runs like a bright thread through Republican politics from Nixon to Bush I to Trump.

The Republican Party’s old guard, including members of the Bush family and their circle, were repelled by Trump in 2016. But this was not a last stand in defense of decency. It was the expression of a will to class dominance against an arriviste who, in his hostile takeover bid, used some of the establishment’s own political tools against it.

Featured image credit: “Donald Trump” by Gage Skidmore. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post From Willie Horton to Donald Trump appeared first on OUPblog.

ASSA 2017: a city and conference guide

The 2017 Allied Social Sciences Association meeting kicks off the new year, taking place 6-8 January in Chicago, IL. The American Economic Association, in conjunction with 56 associations, will hold the three-day meeting to present and discuss general economics topics in wide array of disciplines.

ASSA has plenty going on throughout the weekend. These are some particular events we’re looking forward to:

Thursday, 5 January 5:30-7:00pm Hyatt Regency Chicago, Crystal B

The Econometric Society gives its Presidential Address from Eddie Dekel.

Friday, 6 January 10:15am-12:15pm Sheraton Grand Chicago, Sheraton Ballroom V

Panel discussion: The American Finance Association (AFA) hosts a panel discussing public pension funds featuring panelists Edwin D. Cass, James Poterba, Joshua D. Rauh, and Theresa J. Whitmarsh.

Friday, 6 January 2:30-4:30pm Swissotel Chicago, St Gallen 3

Paper session: Paper presenters, including Sabina Alkire and Jose Manuel Roche, will discuss poverty and shared prosperity as well as multidimensional poverty around the world.

Saturday, 7 January 8:00-10:00am Sheraton Grand Chicago, Grant Park

Paper discussion: Hosted by the Society of Government Economists, presenters will discuss policy challenges of migration.

Saturday, 7 January 10:15am-12:15pm Swissotel Chicago, Vevey 3 & 4

Panel discussion: The Association for Evolutionary Economics hosts the panel discussion “The Vested Interests Versus Rational Public Policy: Economists as Public Intellectuals” with panelists Joseph E. Stiglitz, James K. Galbraith, Stephanie A. Kelton, Lawrence Mishel, and Dean Baker.

Saturday, 8 January 2:30-4:30pm Hyatt Regency Chicago, Regency C

Paper discussion: Presenters discuss papers regarding growth and welfare, from technology and the labor market, to the costs and benefits of leaving the European Union.

Sunday, 8 January 8:00-10:00am Hyatt Regency Chicago, Regency B

The CSWEP Mentoring Breakfast for Junior Economists is hosted by the Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession.

In addition to the programs, panels, and speakers at ASSA, the city of Chicago has a vast range of activities to offer from sight-seeing to theater to top notch cuisine. Here are a few things you should explore during your time in Chicago:

A visit to Millenium Park is necessary whether in Chicago for the first time or returning. Take a photo in front of Cloud Gate, ice skate on the seasonal McCormick Tribune Ice Rink (if you can withstand the cold!), and maybe even stroll along a snow-covered park before ducking into a café to warm up. If you want a twist on typical ice skating, visit the ice “ribbon” in Maggie Daley Park.

Soak up famous art while warding off the cold at the Art Institute of Chicago. See George Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon, Vincent van Gogh’s The Bedroom, and Grant Wood’s American Gothic among countless other works of art and exhibitions. Additionally, the Richard H. Driehaus Museum offers an alternative museum experience by giving you the chance to explore a mansion from the Gilded Age.

Another great way to avoid the chill is to visit the 360 Chicago Observation Deck for the best views of the city and Lake Michigan or, if you’re more daring, visit the Willis Tower Skydeck.

While at the convention, stop by the Oxford University Press booths, 309, 311, and 313, to look at new and featured titles with a conference discount, and follow @OUPEconomics for conference updates. We look forward to seeing you there!

Featured image credit: Chicago USA by Unsplash. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post ASSA 2017: a city and conference guide appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers