Oxford University Press's Blog, page 415

January 24, 2017

Should auld acquaintance be forgot: Robert Burns in quotations

Only a few years after the death of Robert Burns in 1796, local enthusiasts began to hold celebrations on or about his birthday, on 25 January, called Burn’s Night. These have continued ever since, spreading from Scotland across the world. From the earliest occasions, a focal point of the Burns supper was, of course, the haggis:

Fair fa’ your honest, sonsie face,

Great chieftain o’ the puddin’-race!

Although its origins have been disputed, and even attributed to the Romans, haggis is the quintessential Scottish dish, and Burns is famous as the poet of Scotland, both of its history and of its landscape. Once heard, few can forget the triumphalism of “Robert Bruce‘s March to Bannockburn:”

Scots, wha hae wi’ Wallace bled,

Scots, wham Bruce has aften led,

Welcome to your gory bed,—

Or to victorie.

But Burns also has a more lyrical side, making him a great favourite with Scottish tourist boards and advertisers:

My heart’s in the Highlands, my heart is not here;

My heart’s in the Highlands a-chasing the deer.

Those lines, as can be easily seen, are in standard English, but Burns wrote most of his verse in Scots, the Scottish dialect, which has become commonly associated with his name. He not only wrote of his love for the Scottish highlands, and is also particularly remembered for his love poetry, often adapting old Scottish songs in his own style:

O, my Luve’s like a red, red rose

That’s newly sprung in June;

O my Luve’s like the melodie

That’s sweetly play’d in tune.

“My love is like a red red rose?” Image: “Garden, Rose, Red” by Joergelman, CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

“My love is like a red red rose?” Image: “Garden, Rose, Red” by Joergelman, CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.A few years ago, Jeremy Paxman caused a storm by describing Burns as “the king of sentimental doggerel,” but his scope is much wider than that suggests. Some of his lines have even entered the common language. “The best laid schemes o’ mice an’ men Gang aft a-gley,” “Man’s inhumanity to man,” “O wad some Pow’r the giftie gie us To see oursels as others see us!,” and “A man’s a man for a” that’ are all so frequently quoted as to have become clichés.

One thing all of these sayings have in common is their political and humanitarian aspect, reflecting Burns’ own revolutionary interests – he supported the aims of the American Revolution, and in his poems he debates the excesses and inequalities by an aristocracy and an unrepresentative Parliament. However, his fellow Scot Hugh MacDiarmid thought that Burns had been called upon in support of too many causes:

Mair nonsense has been uttered in his name

Than in ony’s barrin’ liberty and Christ.

But the American writer Ralph Waldo Emerson found him more truly influential: “The Confession of Augsburg, the Declaration of Independence, the French Rights of Man, and the ‘Marseillaise’ are not more weighty documents in the history of freedom than the songs of Burns.”

Burns himself took a less serious view of his vocation:

Some rhyme a neebor’s name to lash;

Some rhyme (vain thought!) for needfu’ cash;

Some rhyme to court the countra clash,

An’ raise a din;

For me, an aim I never fash;

I rhyme for fun.

Certainly, one of the folk songs he worked on remains a favourite both internationally and in Scotland at the turn of the new year.

Should auld acquaintance be forgot

And never brought to mind?

We’ll tak a cup o’ kindness yet,

For auld lang syne.

Featured Image Credit: ‘Eilean Donan, Castle, Fortress’ by tpsdave, CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Should auld acquaintance be forgot: Robert Burns in quotations appeared first on OUPblog.

January 23, 2017

Frida Kahlo’s life of chronic pain

Mexican artist, Frida Kahlo, is arguably one of the most well-known painters of the 20th century. Her intimate and personal self-portraits are evocative, generating a deep, almost visceral response. Through her paintings, Frida opens a door and invites the viewer to witness something that is both frightening and profound: her lifelong experience with chronic pain. With more than 40% of American adults experiencing chronic pain, her work is particularly relevant in our contemporary society. The consequences of chronic pain are staggering—individuals with this disease often struggle with depression, disability, social isolation, and poverty. However in Frida, one perceives a courage, a Mexicanisimo, in the face of a disease that has affected the quality of life of so many. While many art historians have analyzed the work of Frida Kahlo, less considered are the neurophysiologic mechanisms underlying her pain and disability. Through her story, her narrative, we learn, perhaps implicitly, how to respond to the adversity of chronic disease.

Frida was born during the Mexican Revolution, a time of political tumult and rebirth of Mexican identity which allowed her to develop into a liberated and independent young woman. Several events in her life, however, would predispose her to chronic pain, a disease that would ultimately claim her life. Early in her life, Frida contracted polio, a devastating infectious disease that attacks the anterior horn cells of the spinal cord. The six-year-old was left with paralysis and atrophy of the muscles of her right lower limb, and ultimately a limb length discrepancy. A sequelae to this terrible disease is post-polio syndrome, characterized by extreme fatigue, new onset of muscle weakness, and severe pain. While Frida experienced many of these symptoms in later life, an accident in her teenage years would overshadow concerns over post-polio syndrome.

At age 17, Frida sustained significant trauma during a streetcar accident, including multiple fractures of clavicle, ribs, spine, elbow, pelvis, leg, and foot. Her right foot was crushed and both ankle and shoulder were dislocated. An iron handrail from the streetcar pierced her left hip and exited through her pelvic floor. Infection ensued and she was not expected to survive. Over the long months of convalescence, Frida faced significant pain and social isolation. She did survive however, and with encouragement from her father she turned to painting. As she made her way back into society, Frida reached out to the famous and charismatic painter, Diego Rivera for encouragement. They would eventually marry.

Frida’s relationship with Diego was alternately passionate and emotionally devastating. She vacillated in her desire for a child and her fear that a child would affect her relationship with Diego. Early in their marriage, Frida experienced a miscarriage that plunged her into despair. At the same time, Frida began to experience a cascade of serious physical ailments, including low back pain, neuropathic leg pain, and vascular insufficiency in her right lower limb. She would be advised to undergo numerous surgeries as treatment, with some disastrously unsuccessful. Many of these life events would be portrayed in her paintings. Frida would become addicted to alcohol and both prescription and non-prescription medications. She died young of a reported pulmonary embolism, however some sources have suggested that it may have been suicide.

This compilation of experiences is characteristic of chronic pain. Emotional, psychological, and physical inputs can facilitate pain mechanisms, promoting worsening symptoms and widespread pain. If Frida lived in our contemporary society, would her health care be better? The answer to this is not clear. Health care providers and scientists are beginning to recognize the underlying mechanisms and clinical characteristics of this disease, although proper management is far from being fully understood. What is compelling about the life of Frida Kahlo is that she rejected the role of ‘afflicted’ and chose to engage fully in society with dignity. Without a doubt, she suffered from tremendous pain throughout her adulthood, yet it is how she chose to live life, not her chronic pain, for which she is remembered. Frida used her painting as a way to separate from the pain and emotional stressors of her life and create representations of her experiences of pain and trauma. This visual narrative provides insight into her life experience and may provide healthcare providers and patients alike a better understanding of chronic pain.

Featured Image Credit: Frida Kahlo House, Mexico City by Rod Waddington. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Frida Kahlo’s life of chronic pain appeared first on OUPblog.

Trump’s Twitter coliseum of torture

President-elect Donald Trump promised on multiple occasions during the campaign to bring back torture in order to “fight fire with fire.” As with some of his other campaign promises (draining the swamp of lobbyists, getting rid of Obamacare in its entirety), Trump may pivot away from torture as well. His meeting with General James Mattis prior to appointing the retired Marine to Defense Secretary seemed to suggest just that, with much of the press emphasizing that Trump was “surprised” and “impressed” to learn that a tough guy like “Mad Dog Mattis” preferred beers and cigarettes over torture for interrogations.

What received less emphasis was Trump’s caveat that “[i]f it’s so important to the American people, I would go for it. I would be guided by that.” It is often unclear whether we should take Trump at his word. If Trump does what he says, however, we are entering a new chapter in the history of torture – or perhaps opening one that has been closed for a long, long time.

Justifications for interrogational torture have been of two kinds since 9/11; explicit and implicit. The explicit justification, from speeches by former President Bush to the steady stream of apologias for the CIA’s torture program from top Bush administration officials down to (some) CIA officers, has been that torture (not called that) was effective in eliciting life-saving information on plots against the homeland. The implicit justification has been revenge, as illustrated in, for example, political cartoons. Locutions such as former Vice President Dick Cheney’s defense of torture in order to go “after the bastards that killed 3,000 Americans on 9/11” indicate that effectiveness and revenge are not mutually exclusive. Trump made this explicit when he said “[b]elieve me, it works. And you know what? If it doesn’t work, they deserve it anyway, for what they’re doing.”

As seductive as an appeal to simple-minded symmetry and jus talionis may be, “fighting fire with fire” often makes for bad practice outside of wilderness fire-fighting. There is a reason ordinary fire engines are stocked with water and not flame-throwers. Torturous executions may be optimal for getting media attention, but that does not mean torture is optimal for getting good information. And whatever sweet pleasure is taken from revenge comes at great cost: failing to get life saving information from methods that work, alienating allies and reducing the cooperation we need from them to catch bad guys, and compromising long standing and deeply held American values.

If Trump does what he says, however, we are entering a new chapter in the history of torture – or perhaps opening one that has been closed for a long, long time.

While there is no evidence Trump has recognized these problems, he has nevertheless introduced a new, plebiscitary, justification for torture by saying he would be “guided” by the American people “if it’s so important” to them. This, in conjunction with other moves such as the involvement of his family, evokes the personalistic populism, patriarchal familialism, and demagoguery of a Latin American “caudillo” or an African “big man” (gated). His penchant for asking the people for their assent to violence, whether at his rallies or now about torture, also invokes the stereotype of a much older model: the Roman emperor before the coliseum, working the crowd for a thumbs up or a thumbs down.

Trump’s crowd is now all Americans and just how he will work them is unclear. Given his preference for Twitter, the modern arena may be much larger, if virtual. Would Trump ask for a thumbs up or thumbs down on the policy as a whole, or, in keeping with his tendency to react to day to day events, on a case-by-case basis? What would Americans do if he really did seek their guidance? A Red Cross survey released in early December is not encouraging, with a near absolute majority (46%) saying “a captured enemy combatant can be tortured to obtain important military information.” Only three in ten said no and nearly one in four replied they didn’t know or preferred not to answer.

Assuming Trump has some respect for the law, even a Twittered thumbs up will be a problem given the 2016 National Defense Authorization Act passed last year. Section 1045 of that spending bill enshrined into law President Obama’s executive order limiting interrogation techniques to those in the Army Field Manual. There are two ways Trump could try to bring back torture given this constraint: work within it by changing the manual or changing the law itself.

Trying the former is likely to meet both legal and political obstacles. The legal obstacle is a provision requiring that the manual be thoroughly reviewed and updated every three years (the first review and update is due in November 2018) “to ensure that Army Field Manual 2–22.3 complies with the legal obligations of the United States and the practices for interrogation described therein do not involve the use or threat of force.” It is difficult to see how waterboarding “or worse” could be seen as not violating the prohibition on force. The political opposition will come not only from Democrats and prominent Republican members of Congress such as Senator John McCain who have promised to fight any attempt by Trump to bring back waterboarding or other torture, but also from the military itself, starting with Defense Secretary Mattis. Of course, this political opposition would also make the second strategy of changing the law itself more difficult.

Trump may nevertheless push for it, especially if there were a terrorist attack in the United States and an attacker were caught alive. In that environment, most of the Congressional opposition which exists is likely to melt away, leaving only principled opponents like McCain, Diane Feinstein, Ron Wyden, and a few others. Within the cabinet and the military, history provides few examples of secretaries and generals who have tendered resignations in protest of Presidential policy. General Mattis may oppose torture, but Trump’s National Security Advisor General Michael Flynn’s position is squishier, and if he goes down far enough, Trump will eventually find someone to sign off. If that happens, Trump can torture by Twitter. After all, there’s an app for that.

Image credit: Pollice Verso (1872) by Jean-Léon Gérôme, Phoenix Art Museum. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Trump’s Twitter coliseum of torture appeared first on OUPblog.

President Trump and American constitutionalism

Citizens of the United States may be witnessing a constitutional crisis, a normal constitutional revolution or normal constitutional politics. Prominent commentators bemoan Donald Trump’s victory in the 2016 presidential election as the consequence of a breakdown of vital constitutional norms that augurs the destruction of constitutional governance in the United States. Other portends suggest that Americans are experiencing a normal constitutional revolution in which a particular political faction gains sufficient control of the national government to make that coalition’s constitutional vision the official constitutional law of the land. Evidence also supports the proposition that the national election of 2016 was only part of a normal political cycle in which Democrats and Republicans alternate control of the White House every eight years.

Trump may or may not be a narcissistic personality, as suggested by several leading psychiatrists, but he is a serial liar, almost certainly a sexual predator, proudly uneducated, notoriously thin-skinned, and a bigot. His utter lack of support among conservative intellectuals, journalists, and others with expertise in American politics speaks to his complete lack of the characteristics traditionally thought vital for the president. If, as Publius repeated in numerous Federalist Papers, the one primary purpose of American constitutional institutions was to privilege to the extent humanly possible the election of the “best people” to public office, then Americans in 2016 apparently experienced a constitutional failure of alarming perspectives. Constitutional democracy in the United States is under siege both because Americans elected a president spectacularly unqualified to govern who has no particular commitment to constitutional democracy, and because the forces responsible for the Trump presidency are likely to rage unabated for the foreseeable future. Being like “the Donald” is likely to be central to candidate handbooks in the 2018 midterms and future presidential elections.

Trump by MIH83. CC0 Public Domain by Pixabay.

Trump by MIH83. CC0 Public Domain by Pixabay.The 2016 national election will have different consequences if Trump governs closer to a contemporary Republican than a chief executive with no ties to any governing institution. Should this occur, the United States may experience a more normal constitutional revolution. Throughout American history, new regimes have come to power and have made their constitutional vision the constitutional law of the land. Republicans during the 1860s rewrote the constitutional text to abolish slavery and promote greater equality. Democrats during the 1930s rewrote the reigning interpretations of the constitutional text when empowering the national government to regulate all facets of economic life. Lincoln’s Republican Party, Roosevelt’s Democratic Party, and, for that matter, Jacksonian Democrats and Reagan Republicans also altered the way constitutional government operated when realizing their constitutional revolution. From this perspective, unified Republican Party government is the most important consequence of the 2016 national election. By more effectively mobilizing lower-middle-class white voters through a combination of ethno-nationalist rhetoric and promises to alter American trade policy, Trump may have forged a relatively enduring Republican Party majority. The combination of gerrymandering and voting restrictions in the states may well result in an electorate even more biased in favor of the Republican Party in the near future. The end result is that something like the constitutional vision of Antonin Scalia may govern Americans for a generation.

The 2016 election also fits a different pattern, one which lacks the drama of a full scale constitutional crisis or normal constitutional revolution. Donald Trump’s victory in 2016 is consistent with the pattern of 18 of the last 19 national elections. Had Democrats won the 1980 presidential election, the presidency from 1944 to 2016 would have changed partisan hands on every eight years without fail. Trump won, on this view, not because constitutional institutions failed or because Americans are not committed to the Republican Party but because the pattern that best explains the Democrats’ victory in the 2008 and 2012 elections best explains Republican success in 2016. Apparent permanent majorities in American politics prove evanescent. Conservativism, dead in 1964, rebounded in 1968.

Sparkler by Unsplash. CC0 Public Domain by Pixabay.

Sparkler by Unsplash. CC0 Public Domain by Pixabay.Democrats, within four years of losing control of all three branches of the national government in 2002, regained the House and Senate, then regained the presidency in 2008. Victory seems to breed failure. President Clinton gained office promising healthcare reform, Republicans took over in the wake of the failed Clinton health care initiative, Obama campaigned on the Republican failure to reform health care, then Republicans rebounded on public dissatisfaction with the Affordable Care Act. Perhaps the Trump election teaches only that the best road to political success is not to be responsible for governing in the recent past.

Over the next few years, Americans and constitutional observers are likely to learn whether the Framers in 1787 did indeed contrive a “machine that would go of itself” or whether human intervention is necessary both to operate the constitution and compensate for systemic constitutional failures. Given the numerous twists and turns of recent constitutional politics, American constitutional development for the next few years may mostly likely confirm the wisdom of the great sage Lawrence Peter (Yogi) Berra, who reminds us, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.”

Featured image credit: Constitution by wynpnt. CCO Public Domain by Pixabay.

The post President Trump and American constitutionalism appeared first on OUPblog.

January 22, 2017

The best medical advice from ancient Greece and Rome

As a highly revered and extensively-studied field, medicine today has certainly evolved from its origins in ancient times. However, to fully appreciate how far we’ve come since then, we’ve compiled some of the best medical advice the ancient Greeks and Romans had to offer back in the day.

Disclaimer: We at Oxford University Press do not condone or encourage heeding the advice below. For medical issues, please (please!) seek the advice of a medical professional (preferably not one from antiquity).

People born when Mars and Saturn are in opposition to each other have a tendency to vomit blood. As for those born when Mars is in opposition to the Moon while he is in Scorpio, Capricorn, Pisces, or Cancer, he will cause them to suffer from impetigo, jaundice, and leprosy. If Saturn is in opposition to the Moon when she is not in her own house nor in the house of Saturn, those born then will have hemorrhoids or be susceptible to boils (Firmicus Maternus Astrology 7.20.11).

Human teeth contain a sort of poison; baring one’s teeth in front of a mirror dulls its brightness, and it also kills fledgling pigeons (Pliny Natural History 11.170).

Such influential physicians as Praxagoras and Phylotimus of Cos could maintain that, whereas the soul is located in the heart, the brain is just some sort of superfluous growth, an offshoot from the marrow in the spine (Galen The Function of the Parts of the Body 3.671K).

Red- haired people are very devious, like foxes (Pseudo- Aristotle Physiognomonica 812a).

Sexual intercourse is good for lower back pain, for weakness of the eyes, for derangement, and for depression (Pliny Natural History 28.58).

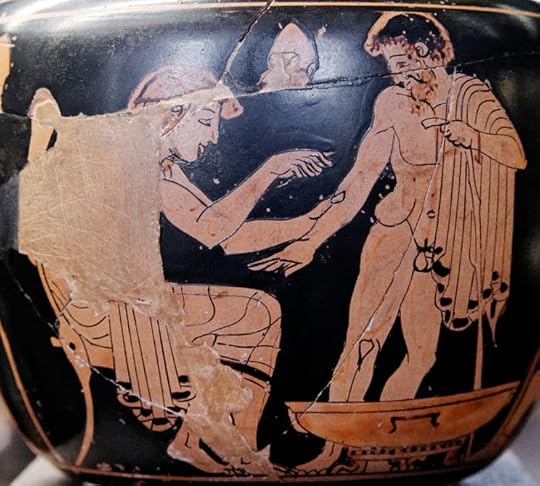

Physician treating a patient. Red-figure Attic aryballos by Clinic Painter. Photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Physician treating a patient. Red-figure Attic aryballos by Clinic Painter. Photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Men have more sutures in their skulls than do women, because their bigger brains need more ventilation (Aristotle Parts of Animals 653b).

Pork is more nourishing than any other food derived from four-footed animals, since it is the meat that tastes and smells most like human flesh, as some people have discovered when they tasted human flesh unawares (Paul of Aegina Medical Compendium 1.84).

People with small faces have small souls, like cats and monkeys (Pseudo-Aristotle Physiognomonica 811b).

People with large faces are slow-witted, like cows and donkeys (Pseudo-Aristotle Physiognomonica 811b).

A cure for severe insomnia: you should tie the patient’s arms and legs at the time when he usually goes to bed, and order him to stay awake. If he closes his eyes, force him to open them. Do this till he is sufficiently exhausted, then suddenly untie him, remove the lamp, and ensure that he is left undisturbed (Oribasius Synopsis to Eustathius, His Son 6.31, drawing on a lost work by Galen).

The human bite is one of the most dangerous. It can be cured with earwax. This need cause no surprise, given that earwax, especially that obtained from an executed person and applied while still fresh, cures even scorpion stings and snakebites. Earwax is also effective against hangnails, as is a human tooth against snakebites, if ground to a powder (Pliny Natural History 28.40).

Bald people tend not to suffer from varicose veins. If a bald person does get varicose veins, his hair grows again (Hippocrates Aphorisms 6.34).

Sneezing occurs when the brain is heated or the cranial cavity fills with moisture. The air inside overflows, and makes a noise because it has to escape through a narrow passage (Hippocrates Aphorisms 7.51).

Featured image credit: Colosseum by martieda. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post The best medical advice from ancient Greece and Rome appeared first on OUPblog.

A new globalization; borders and the role of the state

When people started talking about globalization in the seventies, there was a kind of messianic view that it would change everything; that globalization would sweep the state away, making it no longer the main actor on the global stage. When I taught international relations thirty years ago, and discussion of globalization was taking off, people were predicting the end of the state. There was this vision of global power like a continuum through history; the state was a temporary phase, existing from 1648 through to the late part of the 20th century – at which point it would be swept away. In its place, multinational companies, terrorist organizations, and international organizations would take over the landscape, and the state would be relegated to a position of much less importance. However, that is not what happened. Because what has actually happened is that globalization has, simultaneously, strengthened some forces in society and weakened others. What this has done is create a resistance to the ideas and practices of globalization, which attempts to buffer against its sweep.

This has created a paradox in the state. Because just as the state is less able, now, to control what happens to it – in particular, to control its borders – its populations are more acutely aware of what is happening, and therefore call on the state to manage particular aspects of society even more. Thus, the paradox: as globalization is seen to sweep the state away, this very perception, in some ways, strengthens the state. People demand a reaction to globalization from the state; to “control our borders,” to “stop these cheap goods coming in,” to “disallow these people to come into our country without the right visas,” to “stop letting terrorism in.” People are looking to the state, and needing it more. And yet the paradox is, just as people are saying “protect us from terrorism,” it’s actually more difficult to do precisely that, because globalization makes it easier for all these international, transnational forces to operate. Therefore the state is at the same time more needed, yet less autonomous, and the result is that globalization transforms the state into one that has to operate under an inherent contradiction.

The contradiction that states have to bear affects, most notably, the public discourse regarding the control of their borders. The subject of borders and control is a critical one in politics today. Populations now want their states to control their borders as much as ever, and elections around the world – particularly in North America, Europe, and Australia – have been fought, won, and lost on this worry about migration. Populations say to their governments, “you are our government; we elect you, so control our borders.” The difficulty is, it is now almost impossible for states to control them in the way they used to. There are two main reasons for this: one, international travel is a lot easier. Governments cannot build walls in an age of relatively easy global travel, whatever some politicians think. A state cannot isolate itself. Governments therefore find it more difficult to physically control their borders. The other issue is that, of course, large parts of the world are involved in arrangements whereby control of borders simply does not operate on a national level anymore. The classic case is the Schengen Area, which allows for free movement.

So what does it mean, in Europe, to control the border? It is not easy, once someone enters the EU, to control where they end up. So governments are being called upon by their publics to control the borders, but it is more difficult than ever for them to do so. Globalization has made that happen.

How does globalization respond to this challenge? Well, I don’t think globalization is reversible. Rather, globalization will change and adapt, almost like a virus. At first, people thought globalization meant that actors other than the state – multinationals, international organizations and so on – would become more and more important. But as globalization has developed, what we see is a much more complex network of interests, like a cobweb. The rich in poor countries have the same interests as the rich in rich countries, but the poor in the poor countries may not have the same interests as the poor in the rich countries. Globalization adapts to this complex interplay of interests as they themselves continually shift. After researching over many years, we’ve observed the way in which it has altered. Now, it is not about the domination of organizations like multinationals; it is about forces that represent certain interests, such as capitalism and international violence, which are working through the state, companies, and other organizations to affect world politics.

With this in mind, I still believe that the future of world politics involves more interdependence and more interconnectedness. But it is not the same as what was originally envisaged. It is not reversible, but that does not mean it stays the same.

Featured image credit: English Defence League march in Newcastle by Gavin Lynn. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post A new globalization; borders and the role of the state appeared first on OUPblog.

Direct democracy and the 2016 election cycle

In US general elections a great deal of attention, and much of the money, focuses on events at the national level. But a very great deal of electoral activity also occurs at the sub-national level, with elections for statehouses, governorships, and also initiatives and referendums. In the November 2016 election voters in 35 states were given the opportunity to vote on 154 statewide ballot measures. Roughly $600 million was spent on these campaigns – about half of that in California. This was not an exceptionally busy year. If anything, total numbers of ballot (referendums and initiatives combined) were down by roughly 50 from their turn of the century heights.

As is usually the case, analysts try to identify patterns and trends among the topics on the ballot in a given year. Two points, however, would seem to hold no matter what the year. First, while citizen initiated ballot proposals often attract a great deal of scholarly and media attention (think California’s Proposition 13) fully half – 75 – of these ballot measures were referendum measures put on the ballot by legislators themselves. Many of the latter are bond issues but others have substantive policy goals. In 2016, Alabama’s legislature put on the ballot an anti-union “right to work” measure (Measure 8), legislators in Indiana and Kansas put on the ballot a measure to amended their state constitutions to guarantee the right to hunt and fish, and Missouri’s legislature put on the ballot a photo ID measure (Amendment 6).

Second, as the referendum examples show, each election cycle sees a wide variety of issues being voted on across the US. Multiple proposals on the same or similar topic are often used to identify trends. This year, saw nine ballot propositions that extend the legal use of marijuana, eight of which passed (AR, CA, FL, ME, MA, MT, NV, ND) and one of which failed (AZ). Four proposals increased the minimum wage (AZ, CO, ME, WA) and one proposal – South Dakota’s referred law 20 that sought to lower the minimum wage – was defeated. Three proposals to toughen the regulation of guns and ammunition (CA, ME, WA) passed and a further one failed (NV). Several states saw tax increases: four on cigarettes (CA, CO, MO, ND) and several others increasing corporate or income taxes (CA, LA, ME, OR).

At first blush these proposals can be interpreted as a liberal or ‘blue’ trend that ran counter to the national trend that saw the GOP gain or solidify control of the Presidency, Congress, the Senate, 32 state legislatures, and 33 governorships.

There are, however, two points to bear in mind. First, these more liberal proposals largely won in coastal states. The US political map is red (Republican) in much of the interior but blue (Democratic) on the coasts. In part this also reflects the geography of the initiative process which is predominantly Western, and especially used on the Pacific Coast states, states which voted Democratic in the last several presidential elections.

California State Capitol by PeteBobb. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

California State Capitol by PeteBobb. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.A second point underscores the difficulty of finding trends and patterns when it comes to the policy output of direct democracy. On the one hand, yes, these liberal policy victories do show how voter-initiated measures can put in place specific policies that run against national tides. The examples of marijuana, gun control, and the minimum wage highlight how consequential direct democracy may be in policy terms. Furthermore, because many of these proposals cover multiple states, and also because one of those states is California, then millions of people are affected by these laws. Over 80 million people are affected by the initiated laws on marijuana, over 50 million by citizen-initiated laws on gun control.

On the other hand, however, ballot proposition elections also point up the nuances of public opinion. California’s ballot helps to illustrate this point. In November 2016, Californians had a choice over 17 statewide measures. While this number raised concerns about too many proposals being on the ballot it was not an all-time high number. In November of 1990 there were 28 measures on the California ballot. Among measures on the 2016 ballot, voters did approve the liberal ones noted above and several others, including one upholding a ban on plastic grocery bags (Proposition 67), passed $9 billion in bonds for education, and voted down a measure that would have made bond financing of infrastructure projects harder in future. So far so liberal. But Californians also rejected an attempt to ban the death penalty and in fact passed a measure (Proposition 66) that would limit appeals in death penalty cases.

Alongside the liberal measures, then, we also see conservative ones succeeding at the polls, even within the same state at the same election. That kind of mixing of liberal and conservative measures, as well as the wide range of topics means that when thinking of ballot propositions, finding patterns is something of a Rorschach test in that a great deal of the patterns lies in the eye of the beholder. In that sense this election cycle had some similarities to past cycles in providing a mix of issues that help underscore the importance of ballot proposition elections.

Featured image credit: I Voted sticker from 2016 election by Dwight Burdette. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Direct democracy and the 2016 election cycle appeared first on OUPblog.

Really big numbers

What is the biggest whole number that you can write down or describe uniquely? Well, there isn’t one, if we allow ourselves to idealize a bit. Just write down “1”, then “2”, then… you’ll never find a last one.

Of course, in real life you’ll die before you get to any really big numbers that way. So here’s a more interesting way of asking the question: what is the biggest whole number that you can uniquely describe on a standard sheet of paper (single spaced, 12 point type, etc.) or, more fitting, perhaps, in a single blog post?

In 2007 two philosophy professors – Adam Elga (Princeton) and Agustin Rayo (MIT) – asked essentially this question when they competed against each other in the Big Number Duel. The contest consisted of Elga and Rayo taking turns describing a whole number, where each number had to be larger than the number described previously. There were three additional rules:

Any unusual notation had to be explained.

No primitive semantic vocabulary was allowed (i.e. “the smallest number not mentioned up to now.”)

Each new answer had to involve some new notion – it couldn’t be reachable in principle using methods that appeared in previous answers (hence after the second turn you can’t just add 1 to the previous answer)

Elga began with “1”, Rayo countered with a string of “1”s, Elga then erased bits of some of those “1”s to turn them into factorials, and they raced off into land of large whole numbers. Rayo eventually won with this description:

The least number that cannot be uniquely described by an expression of first-order set theory that contains no more than a googol (10100) symbols.

A more detailed description of the Duel, along with some technical details about Rayo’s description, can be found here.

Fans of paradox will recognize that Rayo’s winning move was inspired by the Berry paradox:

The least number that cannot be described in less than twenty syllables.

This expression leads to paradox since it seems to name the least number that cannot be described in less than twenty syllables, and to do so using less than twenty syllables! Rayo’s description, however, is not paradoxical, since although it uses far fewer than a googol symbols to describe the number in English, this doesn’t contradict the fact that, in the expressively much less efficient language of set theory, the number cannot be described in fewer than a googol symbols.

The number picked out by Rayo’s description has come to be called, appropriately enough, Rayo’s number. And it is big – really big. But can we come up with short descriptions of even bigger numbers?

Notice that Rayo’s construction implicitly provides us with a description of a function:

F(n) = The least number that cannot be uniquely described by an expression of first-order set theory that contains no more than n symbols.

Rayo’s number is then just F(10100). So one way to answer the question would be to construct a function G(n) such that G(n) grows more quickly than F(n). Here’s one way to do it.

First, we’ll define a two place function H(m, n) as follows. We’ll just let H(0, 0) be 0. Now:

H(0, n) = The least number that cannot be uniquely described by an expression of first-order set theory that contains no more than n symbols.

So H(0, n) is just the Rayo function, and H(0, 10100) is Rayo’s number. But now we let:

H(m, n) = The least number that cannot be uniquely described by an expression of first-order set theory supplemented with constant symbols for:

H(m-1, n), H(m-2, n),… H(1, n), H(0, n)

that contains no more than n symbols.

In other words, H(1, 10100) is the least number that cannot be described in first-order set theory supplemented with a constant symbol that picks out Rayo’s number. Note that, in this new theory, Rayo’s number can now be described very briefly, in terms of this new constant! So H(1, 10100) will be much larger than Rayo’s number.

But then we can consider H(2, 10100), which is the least the least number that cannot be described in first-order set theory supplemented with a constant symbol that picks out Rayo’s number and a second constant symbol that picks out H(1, 10100). This number is much, much bigger than H(1, 10100)!

And then we have H(3, 10100), which is the least the least number that cannot be described in first-order set theory supplemented with a constant symbol that picks out H(0, 10100), a second constant symbol that picks out H(1, 10100) and a third constant symbol that picks out H(2, 10100). This number is much, much, much bigger than H(2, 10100)!

And so on…

We can now get our quickly growing unary function G(n) by just identifying m and n:

G(n) = H(n, n).

And finally, our big, huge, enormous, number is:

G(10100)

G(10100) is the least number that cannot be described in first-order set theory supplemented with googol-many constant symbols – one for each of H(0, 10100), H(1, 10100), … H(10100-1, 10100).

This number really is big. Can you come up with a bigger one?

Featured image: “Infant Stars in Orion” Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Really big numbers appeared first on OUPblog.

January 21, 2017

What happens if we ignore climate change?

What are the arguments for ignoring climate change?

The simplest is to deny such a thing exists. President Trump’s tweets on the topic, for instance, mostly run along the lines of “It’s record cold all over the country and world – where the hell is global warming, we need some fast!” But this is plainly at odds with the evidence, given what we know now about rising temperatures and accumulation of heat in the oceans.

The next-level argument accepts that the world is warming, but claims that humans are not responsible. However the recent climate record is difficult to explain any other way. For example, while the lower levels of the Earth’s atmosphere are warming, the stratosphere is cooling. This is contrary to what would be expected if warming was caused by increased solar activity, or changes in the Earth’s spin and tilt that expose the planet to more incoming radiation, which would heat the atmosphere all the way through. But it fits if the predominant cause is a thickening blanket of heat-trapping greenhouse gases close to the surface of the planet.

One might argue that climate change is underway, and yes, humans are responsible by and large, but it is not such a bad thing. Under this banner a variety of positions are taken. It may be (and is, sometimes) claimed that the benefits of climate change outweigh the disadvantages. More common is a nuanced argument along the lines of “it is not such a bad thing compared with other problems we now face” and therefore it makes sense to push climate change down the list of priorities. In effect, the problem is ignored.

The “not such a bad thing” world-view minimizes the risks of climate change to human health and well-being. One way of testing this position is to examine the impacts of past changes in the climate (which, it must be noted, are relatively minor compared with what is projected to lie ahead if present trends in greenhouse emissions continue).

Climate change has played an important part in the long course of human history. Indeed the emergence and success of our species were climate-related. Environmental conditions were the motor that drove evolution – stature, mobility, skin colouring, brain size are just some of the consequences of intermittent drying, heating, and cooling, and it is not drawing too long a bow, perhaps, to say that in some respects climate change made us human.

Bearing in mind this legacy, it is not so surprising that our physiology is very sensitive to ambient temperature and humidity. Humans operate, as tuned machines, in the “Goldilocks zone”, with just enough but not too much warmth or rainfall. Pre-requisites for health such as a nutritious diet and a secure supply of safe drinking water are affected by climate; disease vectors (mosquitoes and ticks for example) may be suppressed or promoted by climate shifts. Extreme weather leading to floods, fires, and heatwaves causes death, disease, and displacement, even in high-income countries – and the effects are amplified by poverty.

High water by Hans. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

High water by Hans. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.If we want to understand the sensitivity of human societies to heating, cooling, drought, and excessive rainfall, then there is ample material in the historical record. Crises stand tallest – there are many examples of dramatic peaks in mortality associated with droughts, migration, warfare, and plagues. Rapid cooling and unusual variability in the climate at the end of the so-called “Classical Optimum” (around 400 CE) promoted the arrival and spread of new infections in failing Rome. Hunger and violent disorder following crop failures in drought-ridden Central America accelerated the fall of the Mayans. When Mt Tambora erupted in 1815, it threw so much ash into the atmosphere that temperatures fell around the world by as much as three degrees Centigrade on average, leading to a decade of food crises, epidemics, and social unrest.

The spread of farming, the Bronze Age, the rise and fall of American civilizations, and the impacts of the Little Ice Age in Europe and China all present direct connections between death, disease, de-population, and climate changes in both the regional and global sense.

So the argument here is: if we look back, we see the ways in which climate bears down on human health. If we look forward, we face changes that greatly exceed, in scale and speed, what happened in the past. The Holocene, the past 11,000 years during which human culture flourished and the nation state emerged, was a relatively stable time. Rises and falls in decadal-average temperatures rarely exceeded two degrees Centigrade. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projected that global average temperatures may rise by four degrees Centigrade by 2100, with heating occurring much more rapidly in some parts of the world (most spectacularly and dangerously, in the Arctic).

In short, we ignore climate change at our peril. What puts humans at risk is the combination of culpability (we have the capacity now to put a serious spoke in the wheel of global systems) and vulnerability. To those who cannot or will not engage, we might say “watch out – humans may be clever enough to cause the problem, but not clever enough to escape the consequences, short of mass migration to a new and better planet”.

Featured image: Tree by katja. CC0 Public domain via Pixabay.

The post What happens if we ignore climate change? appeared first on OUPblog.

Remembering Kevin Starr

The only thing that gave me some comfort learning about Kevin Starr’s sudden passing is knowing that he has left behind something as lively and monumental as the man himself: his Americans and the California Dream series. I had the weighty task of editing the last of the books in this series, Golden Dreams, which Kevin felt to be his favorite and most personal because it was about the 1950s, when he met his wife Sheila. The editing had been left unfinished when Sheldon Meyer, Kevin’s longtime editor, died. Sheldon had read many chapters individually, raving about parts of each–but especially the jazz chapter (naturally)–and cheering Kevin on to finish, while noting that of course the chapters were all too long.

When I got the full manuscript, it was sprawling—in breadth and length. When I sent off my heavy edit, it was with some trepidation, knowing that Sheldon and Kevin had enjoyed a close working relationship for four decades. What a relief with I received a gracious and grateful message from Kevin, who said that he was getting down to work on his revisions.

Golden Dreams published at a moment when many of the abundance of the postwar years and its creations—the public university system, affordable housing, a booming economy, an ambitious physical infrastructure, an enviable environment, and more—were being publicly mourned. In retrospect, the book was perfectly timed but the timing only highlighted how distant this golden age a half-century before seemed.

Although Kevin had written his last volume of the series and turned to work on another multivolume series on Catholics in America, he will forever be synonymous with California. His exuberant and exhaustive Americans and the California Dream series has given the state its definitive and enduring narrative. I’d like to think Kevin and Sheldon are somewhere listening to jazz and toasting the Dream and lives well lived.

Featured image credit: ‘Pacific Coast Highway’, by Lars0001. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Remembering Kevin Starr appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 237 followers