Oxford University Press's Blog, page 414

January 26, 2017

How to be a successful special adviser: five tips

Political advice is the topic of the moment. Added to periodic quarrels about the pay and influence of special advisers, a new US President is putting the final touches to his team of advisers while the British Prime Minister faces an array of conflicting recommendations about Brexit. Advice itself seems to have become politicised. Yet there have been plenty of arguments down the centuries about who appoints advisers and what types of people they should choose, what the role of such counsellors ought to be, and to whom they are accountable if things go wrong. Life as an adviser seems to offer the chance of power and influence, but at the risk of one’s reputation if things go wrong. So what might be the knack of successful counsel? Perhaps history can offer some help to budding advisers. Here are five tips:

Getting noticed

Style matters as much as substance. Good advice has often been associated with frank plain speaking. The oily words of a Wormtongue constitute the type of poisonous flattery—telling rulers what they want to hear—that earns you a bad reputation. But bold bluntness can come just a little too close to brusque impertinence. A touch of deference—public respect (perhaps an apologetic excuse for being thought to speak out of turn)—nicely combines compliment and criticism. Ancient rhetoricians called it “blaming through praising.” It still comes in handy.

Bust of Cicero, Musei Capitolini, Rome, Half of 1st century AD. Photo by Glauco92. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Bust of Cicero, Musei Capitolini, Rome, Half of 1st century AD. Photo by Glauco92. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Policy making or paper pushing?

Access to power has always mattered, but should one seek it by way of informal routes that might not involve much public recognition? Having an official position on a fairly formal council might appear to be the way to wield influence. But is it just a place for routine admin? The formation of policy strategy has often taken place more informally—in the bedchambers and hunting lodges, the corridors and closets of palaces—rather than in the council chamber. Tension between the cabinet table and sofa government is hardly new. Henry VIII’s chief strategist Thomas Cromwell was careful to keep up contacts in the privy chamber as well as in the king’s council. So don’t be fobbed off with an empty title that actually detaches you from the real scene of power.

Keeping a record

Institutions like paper trails. But rulers and advisers find secrecy very useful. Small-group based, informal, fluid ways of giving and receiving advice helpfully allow flexibility. “Secret” and “private” have often been used to condemn “evil counsellors”. But blabbing ideas round the court, or leaking them to the press, isn’t very helpful either. Paper trails do still have their uses. If only William Davison, the secretary blamed by Elizabeth I for dispatching Mary Queen of Scots’ death warrant without royal permission, had had one. She said she told him to keep it secret. He said he thought that meant only telling privy councillors. Don’t be caught out by such ambiguities, even if a spell in the Tower of London is fairly unlikely, these days.

Does friendship come into it?

In the best cases, yes. This might run counter to notions of impartial advice; and it’s true that earlier ages had a sense of conflicts of interest. But for most of history the idea of friendship was associated with giving honest advice for the recipient’s benefit—exactly what a counsellor ought to be doing. Again, the classical world had a lot to say on the subject—ideas still around in the age of the Tudors and the Civil Wars. Cicero’s view of friendship wasn’t quite the same as Facebook’s. Instead it fostered a vital bond of trust between ruler and adviser. Hard to know how much to rely on this, if a scapegoat is needed in an emergency. “Bad” or “evil” advice is still all too easy an excuse for a leader to use in a tight spot. And well-meaning friends or relatives tend to be the ones suspected of meddling, even by rulers. Beware of becoming the Glencora Palliser to your prime ministerial duke.

Don’t despair

All the above probably sounds a bit cynical or—at best—impossible. How can you be courteous and frank, straddle formal and informal power structures, maintain secrecy and keep a record, trust and be cautious? The answer is you can’t do all these things all of the time. The problem is that, down the centuries, governments and citizens have wanted advisers to be able to do just that. But that’s not a reason to give up. Even if you fail to get your policy suggestion adopted, the exchange of advice will probably have been beneficial. Awareness of different views, a sense of inclusion and consultation, renewing the links between governments and citizens — advice not followed still does all these things. Having your advice accepted might better be seen as a bonus extra. If it works, that’s even better. Just don’t expect any credit for it; except, perhaps, from the historians.

Featured image credit: Princes and other statesmen: twenty portraits. (Left to right: Lorenzo de Medici, Sir Thomas More, Cardinal Wolsey, Cromwell Earl of Essex.) Engraving by J.W. Cook, 1825. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How to be a successful special adviser: five tips appeared first on OUPblog.

David Lynch’s dream of dark and troubling things

20th January marks the 71st birthday of American film director David Lynch. At 71 years old, the master of innovative film-making shows no signs of slowing down any time soon. In fact, given his most recent theatrical output, 2006’s Inland Empire, one could say that David Lynch is only growing bolder and more confident as he gets older. In celebration of his unique and highly influential work in the realm of cinema, as well as his return to television for the reboot of Twin Peaks in May 2017, this essay takes a look back at some of the director’s best work and discusses what it is that makes his films so memorable and effective.

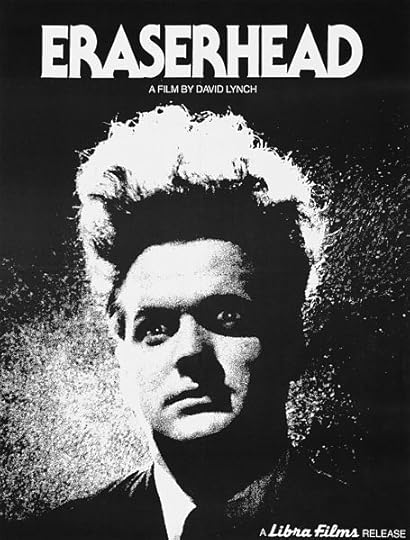

Growing up, he began his life-long affair with the arts as a painter, often depicting dark and/or surreal images that would serve to inform his later work in short and full length films. He later attended art school in Philadelphia, and soon began working on his first feature length film, Eraserhead. Taking cues from legendary directors of the past, such as Federico Fellini, Alfred Hitchcock, and Stanley Kubrick, Lynch set out to create his own unique vision of the human experience. Initially finding a receptive audience with the midnight cult movie crowd following the release of Eraserhead, Lynch went on to refine and perfect his artistic vision with breakout films such as Blue Velvet (1986) and Mulholland Drive (2001), and also co-created the hit television show, Twin Peaks (1990-1991) with Mark Frost. His work, often characterized by non-linear narratives, with dark and frequently violent portrayals of American life, has come to be known by the term “Lynchian.”

Frequently operating within a framework that relies heavily on the logic and power of dreams, Lynch utilizes every tool at his disposal in order to construct scenes that speak directly to an audience’s most basic and primal emotions, particularly fear and love. He is notorious for his meticulous attention to sound design, and his first film beautifully demonstrates just how well this translates on screen. Eraserhead, Lynch’s 1977 debut film, makes extensive use of sound, employing a harsh and unnerving soundscape of industrial machinery to create an atmosphere full of dread and paranoia. The absence of a musical score (with the exception of “In Heaven (Everything is Fine)” sung by the lady in the radiator) adds to the distinct sense of anxiety and desolation that permeates the film. The viewer is left to wander this bleak environment along-side the main character, Henry Spencer, with nothing to accompany the journey except the perpetual grinding of unseen machinery. Adding to the mystique of this film, Lynch (who famously refuses to comment on the meaning behind most of his work) has stated that this is his most spiritual film, and that the inspiration for it was his brief stint spent living in Philadelphia.

Eraserhead poster by Libra Films. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Eraserhead poster by Libra Films. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Lynch’s fascination with music and sound, along with his fondness for dreams and the subconscious, often come together to convey striking portrayals of the human condition and psyche. His 2001 film, Mulholland Drive, explores themes of love, obsession, and uncertainty in contemporary Los Angeles, as filtered through the subconscious. Seemingly drifting in and out of a dark dream, Lynch paints a heart-breaking portrait of a struggling actress who may or may not be constructing her own reality as a means of coping. What makes his films so interesting to watch is his uncanny ability to manipulate a viewer’s emotions at will, even if the events on screen are not wholly understood within the context of a non-linear plot. One particular moment that comes to mind is the now famous scene at Club Silencio in Mulholland Drive. The two main characters find themselves in a fictional LA nightclub, where singer Rebekah Del Rio lip-syncs to a Spanish version of Roy Orbison’s “Crying,” fainting mid-way through as the song continues, revealing that the entire performance was in fact pre-recorded. As this happens, the music continues to play as the singer is dragged off stage and the camera cuts to the two women crying uncontrollably in their seats. This scene (as with the majority of Lynch’s work) is up for interpretation. But the point here is that without any context or understanding, this sequence can stand on its own. The visuals, coupled with the music and visceral reactions from the characters draw the viewer further into this world where meaning exists, but only on the fringes. In Lynch’s capable hands, viewers are swept up in an overwhelming sense of sadness, profoundly aware that something vital may have been lost.

Lynch thrives in these gray areas, often depicting his characters in the midst of psychological and social upheaval which leaves them lost in confusion and isolation. Films such as Lost Highway (1997), Inland Empire (2006), and Blue Velvet (1986) all portray complex characters that exist in a perpetual state of uncertainty. It’s as if his characters can each account for the once-missing pieces of their fractured lives, but have no concept of what the finished product should look like. Lynch leaves them to find their own way, and in doing so becomes a master of walking the line between enlightenment and ignorance.

While there may very well be those who are critical of his work, dismissing it as weird, oppressive, or impossible to follow (and it very well can be), it would be difficult to deny the subtle genius of his work. He is considered to be one of the most ground-breaking and innovative directors in American film. He continues to be very active today in music and film, while also finding the time to promote his very own brand of coffee, and spread the word about the many benefits of Transcendental Meditation. Best wishes to one of the most celebrated directors of our time.

Featured Image credit: David Lynch photographed on 10 August 2007. by Snowmanradio. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post David Lynch’s dream of dark and troubling things appeared first on OUPblog.

Music-based activities for children with autism spectrum disorder: experimenting with vocal sounds

Individuals with autism spectrum disorder respond positively to music. This is due, in part, to their ability to perceive and remember isolated pitches and identify the contour of melodic fragments. As well, a positive relationship exists between a child’s ability to vocalize musically and the ability to speak. These observations support the use of music-based activities for students with ASD as they practice and demonstrate their ability to perceive pitch and to represent melodic contour, syllables, and words with their voices. Teachers may wish to introduce the following activities to their students, derived, in part, from a presentation I gave at the Ideas conference at the University of Calgary.

Activity 1: Birds and Bees

In this activity students demonstrate their ability to perceive and reproduce melodic contours created by the flight patterns of birds and bees. When first implementing this activity, the leader (usually the teacher) stands at one side of the classroom holding a toy bird or bee. The leader flies the bird or bee across the room and the children produce vocal sounds (e.g. hum or bzzz) to show the contour of the flight path. Once children are familiar with this activity, a child can be chosen to fly the bird or bee. Two-part singing is created when two children construct flight paths simultaneously and their peers decide which of the contours to follow with their voices.

Activity 2: In a Hot Air Balloon

This activity provides another way for children to demonstrate melodic contour with their voices. The teacher draws a picture of an out-of-doors perspective on a white board. This could be a cityscape with tall buildings and roads or a rural view with fields and trees. On one corner a hot air balloon is drawn. A contoured line is drawn from the balloon and across the picture. The children use their voices to create sounds that show the contour of the balloon’s flight path. Alternately, the teacher could create a hot air balloon with a basket, some strings, and balloons and then fly the balloons across the illustration.

Activity 3: Picture Books Guiding Vocal Production

Many children’s books contain words that suggest vocal sounds. Using the book Cock-a-doodle-doo, creak, pop-pop, moo, students add vocal sounds to narratives such as Cluck, cluck, cluck. Hens are fed (np) or Sparrows sing, Chirp, chip, chip, chip (np). Depending on each student’s background, sometimes the vocal accompaniments resemble the words spoken by the teacher; sometimes the vocal sounds cannot be distinguished as those in the text. Students who are unable to vocalize may participate by adding sounds with non-pitched percussion instruments by representing clucks with woodblocks and chips with triangles, for example.

Activity 4: Songs with Simple Repeated Texts

Teachers may encourage students with limited verbal skills to vocalize with portions of songs. The song “Bingo” is an ideal vehicle for this process as it contains the repeated motive B-I-N-G-O. Students are encouraged to take part in the singing in whatever way best suits each individual. Some students may be able to sing the words with the teacher and peers; some students may choose to add vocal sounds only for the vowel and consonant sounds contained for the repeated pattern of B-I-N-G-O. Sometimes these vocalizations resemble the expected vowels and consonants; other times the students create personal verbalizations that do not resemble the vowels and consonants in the song. Imprecise vocalizations are encouraged as, with practice, these verbalizations may become more accurate over time.

Activity 5: Kazoos

The teacher may begin by modeling the song “Bingo,” singing most of the lyrics, but playing a kazoo for the B-I-N-G-O motive. Students are then given kazoos. The teacher sings the lyrics and, either alone or along with the teacher, the students play this motive with their kazoos. Following this practice, the teacher encourages the students to sing the B-I-N-G-O portion of the song.

Featured image: “Greece Odyssey 628” by US Department of Education. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Music-based activities for children with autism spectrum disorder: experimenting with vocal sounds appeared first on OUPblog.

Spiritual surgeries: a radical alternative medicine?

Why are so many people in the West, who have access to the best biomedicine, turning to complementary and alternative medicine (CAM)? Naturopathy, homeopathy, Ayurveda, traditional Chinese medicine, meditation, reiki, massage, yoga, all have experienced a surge in the twenty-first century.

Overall, sociologists found that in the past decades more and more people are mistrusting institutions and losing faith in progress, science, and politics. They explained that the prominence of science and knowledge have meant social practices are constantly examined, reflected upon, and changed, as new knowledge comes to the fore. Thus, doubt and instability are everywhere. While in traditional societies individuals deferred to an external authority and their own choices were limited by traditions and customs, now people are able to “work” on their identity rather than inherit it.

This choice of lifestyle and rejection of an external authority also extend to how people relate to biomedicine. Studies have shown that people choose alternative therapies for several reasons: their disillusionment with biomedicine’s ability to deal with illness, particularly chronic illness; a search for a more egalitarian relationship between doctors and patients (i.e., the empowerment of patients); a search for meaning and context for their illness; a feeling that alternative therapies can offer a better medical model for and a different understanding of their illness; and the emergence of “postmodern values,” such as a decline in faith in the ability of science and technology to solve the problems of society and the individual.

Image credit: John of God attending to people at Casa de Dom Inácio by Cristina Rocha. Used with permission.

Image credit: John of God attending to people at Casa de Dom Inácio by Cristina Rocha. Used with permission. Image credit: Follower praying at the triangle at Casa de Dom Inácio by Cristina Rocha. Used with permission.

Image credit: Follower praying at the triangle at Casa de Dom Inácio by Cristina Rocha. Used with permission.Broadly speaking, these were the reasons people I met in my research gave me for seeking healing with the Brazilian faith healer John of God (João de Deus). However, they found in John of God a more radical form of alternative medicine, one that made the healer even more attractive to them and that has made him famous worldwide. While purportedly incorporating spiritual “entities,” John of God performs surgeries in which he cuts people’s skin with a scalpel, scrapes their eyes with a kitchen knife, or inserts surgical scissors deep in their noses, all without asepsis or anesthetics. They have not reported infections after these surgeries. Despite John of God asserting that “invisible” surgeries (based on prayer and without cutting) are equally effective, many Westerners interviewed hoped to undergo the extraordinary experience of “visible” surgery. They wanted to feel the presence of transcendence in their own bodies. In that way, they felt that the “spiritual world” was caring for them. This was particularly so in those cases of chronic or terminal illnesses, where biomedicine could do very little for them. Moreover, I also found that a sense of community was important for them. By sharing their stories of illness with others who were also ill, they recovered hope and a sense of joy. People offered each other social and emotional support while undergoing life crises.

In general, I found that industrialization, modernization, and secularization have created a longing for an (idealized) past when time was slower and nature was not degraded, when there was a connection with the “spiritual,” and a strong sense of community and belonging. The little town of Abadiânia, where John of God’s healing center is based, gave foreigners a place where this nostalgia for a more simple and spiritual life could be found.

Rather than perceiving the rise in CAM and radical alternative medicine as strange and irrational, perhaps we could take some lessons for healthcare in the twenty-first century. For instance, instead of a focus on the disease—“fixing” a part of the body which is malfunctioning—biomedicine could start also attending to illness—the experience of disease from the patients’ and their families’ perspectives (such as discomfort, depression, and frustration of being sick, which also affects patients’ outcomes). Rather than placing patients in large hospitals which may become centers of infectious diseases, healing can also take place in smaller clinics, hopefully containing sunny outdoor spaces, and with others who are undergoing similar experiences so that they can support each other. Given that biomedicine has become so expensive, it is conceivable that low technology can also support the healing process.

Featured image credit: Main Hall at Casa de Dom Inácio, John of God’s Spiritual Hospital in Brazil by Christina Rocha. Used with permission.

The post Spiritual surgeries: a radical alternative medicine? appeared first on OUPblog.

January 25, 2017

Face to face with brash: part 1

Lat week, I discussed the hardships endured by an etymologist who decides to investigate the origin of English br- words, and promised to use that post as an introduction to the story of brash. Today, I’ll try to make good on part of my promise.

There are at least three words spelled and pronounced as brash. One surfaced in Scots in the fifteenth century and meant “attack.” Later, it narrowed its meaning to “a bout of sickness,” and survives in water brash “eructation of liquid from the stomach.” Then there is brash “brittle,” known since the sixteenth century. It’s anybody’s guess whether the best-known brash “rash, impetuous, audacious” is the same word as brash “brittle.” The senses match poorly. Rashness can of course result in being broken, but the connection is tenuous. The late eighteenth-century brash “a mass of fragments” appears to be akin to the obsolete verb brash “to break (a wall)” and goes well with brittle. Regional words, those mentioned in The English Dialect Dictionary by Joseph Wright, add nothing new. Brash “brittle” and “rash, impetuous” are common all over England. Cold, bracing weather could be called brash. In Yorkshire, brashing was (or still is?) the name of a weakling, used of a child or animal. Fern’s runt Wilbur (in E. B. White’s book Charlotte’s Web) was certainly a brashing. In Scotland, according to Jamieson, bread made of a mixture of rye and oats is called brash-bread.

In Yorkshire, this runt would be called a brashing.

In Yorkshire, this runt would be called a brashing.Some of the words, mentioned above, are obviously related, and it comes as a surprise how little etymological dictionaries have to say about the derivation of brash. “Origin unknown” is not an uncommon verdict, while Hensleigh Wedgwood, Eduard Müller, and Walter W. Skeat, whose opinions we naturally consult in such cases, did not even include it. The reason for this invidious reservation is not clear to me. An association of brash with break and brittle comes to mind at once, and the sound-imitating role of br– also suggests itself, but shortcuts are dangerous. Brittle is an adjective, obliquely allied to the Old English verb brēotan “to break.” I said obliquely, because a direct tie from brittle is not to brēotan but to bryttan, a verb formed from the same root but on a different grade of ablaut. One is disappointed to read that the origin of bryttan is also unknown. Doesn’t the onomatopoetic br– give us a clue? It does, but the rest of the word has to be accounted for too. What is worse, brittle is not related to break. The Old English for break was brecan. It shares only the suggestive part br– with bryttan.

Yet the feeling prevails that brash, break, and brittle somehow belong together. This need not mean that they have a common origin. We notice time and again that words derived from the same root part ways, and only an etymologist can detect how the story began, while words coming from different, though similar-sounding roots form a family like so many children from an orphanage: they wear the same uniform, go to the same school, adopt the same manner of speaking, and begin to look like members of one family (in the past, I have more than once used the image of an orphanage and of a cluster of rootless mushrooms growing on a stump). Many br– words illustrate this situation, and it need not surprise us that an ingenious German linguist has written several articles and a book about br– words. However, here we should still concentrate on etymology. The first hypothesis will be familiar to those who read this blog with some regularity. I often refer to Jacob Grimm’s suggestion that a historical linguist should try to find the same etymon of the homonyms occurring in old languages. Several English words sound as or like brash. Are thy offspring of the same parent?

Brash, in at least one of its meanings, sounds very much like French brèche “breach,” but the French word is of Germanic origin, even though Middle English borrowed breach from Old French. Such words as arose in Germanic, traveled to French, and later returned “home” (indeed not to Franconia but to England) are rather numerous. If the original English word for “breach” had survived, it would have sounded, depending on the dialect, as brich (in the Standard), as brech (in Kent), and bruch (in the southwest). However, French brèche could at most be responsible for brash “a mass of fragments; rubbish” (Wright mentions “the valueless clippings of hedge; twigs; small stones, etc.”). Surprisingly, we find Engl. brush “loppings of tress” (compare Wright’s “the valueless clippings of hedges, twigs”!); thicket,” especially well-known from brushwood. The final consonant (sh instead of ch) is again due to the fact that brush is a fourteenth-century borrowing from French, allegedly, a reflex of an old Romance noun. But the similarity is astounding, and one wonders whether the traditional etymology is correct. Couldn’t brash be a variant of brush?

A breach is a breach, whether in the wall or of data, Romance or Germanic.

A breach is a breach, whether in the wall or of data, Romance or Germanic.Such vowel alternations are common in dialects. Even in Standard Modern English we run into amusing cases of vocalic leapfrog. Since we are in the br-room, I may mention brolly for umbrella. This is a piece of British university slang, but slang often serves as a lab of sound change. By contrast, freshman is an American word. Yet someone, obedient to the same incomprehensible impulse, turned it into frosh. Still another “expressive” slangy alternation is the twentieth-century monster wodge for wedge. Perhaps our readers can cite more examples of the same game. Be that as it may, in dialects such alternations, usually called secondary, or false, ablaut, are frequent, and I see no reason why brush and brash, both denoting “tree clippings,” could not be a pair like fresh- and frosh. All of it is mere guessing, to quote Skeat’s favorite pronouncement. Gaelic Irish has bras “hasty, impulsive” and brais “a fit, convulsion,” but, as always, when dealing with similar forms in Irish and English, one cannot be certain which came first. It seems that the English words have safer antecedents than their Irish analogs.

Leapfrog is a favorite game not only of children but also of sounds.

Leapfrog is a favorite game not only of children but also of sounds.Still another complicating factor in the search for the origin of the adjective brash is the existence of its synonym and near homonym rash, a respectable Germanic and English word. Considering that br– is sound-symbolic, couldn’t rash be turned into brash to add vigor to the adjective? In dealing with Indo-European, scholars constantly play such games, but the closer they approach the modern language, the more reluctant they become and try to avoid such “rash” conjectures. Once I dared a similar suggestion about Old Engl. brōga “dread.” Its origin is unknown, but there was ōga (a word with the same meaning, a cousin of Modern Engl. awe: a cousin, because awe is a borrowing from Scandinavian), and I made bold to write that brōga was ōga, with br– added to make the word sound more frightening. Ferdinand Holthausen, a cautious etymologist, stated in the last edition of his etymological dictionary that brash, which he glossed as “to break” (!), is a blend of break and clash or crash. He partly followed the OED.

It appears that the choices facing us are many, and all of them are bad. We’ll see what we can do about the origin of brash in two weeks. Next week’s post will be devoted to the January gleanings.

Images: (1) Cat, Kitten by rebel1965, Public Domain via Pixabay. (2) “Retaining wall breach” by Hefin Richards, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons (3) Stature, PC by succo, Public Domain via Pixabay (4) “Bremerhaven Thiele 3” by Uwe Barghaan, CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons Featured image: Plateau, scrub by 4939, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Face to face with brash: part 1 appeared first on OUPblog.

Thomas Schelling: An unconventional economist

Thomas (Tom) Schelling was one of the best, and most unconventional, economists of his generation. Using simple arithmetic and more common sense than most economists are born with, he could turn problems upside down and inside out, and come up with novel solutions.

Tom liked to tell a story, over a nice glass of wine, about how he would find a friend in Washington DC if they were separated and had no way of easily finding each other. Essentially, he’d do a thought experiment about where the person might go if they were lost to meet with Tom, and then Tom would do the same thought experiment for himself. The end result might be that the two people could meet at a landmark they both knew, such as the post office. They might both go to that place because they knew it was a landmark that the other person might go to. This led to his important idea – focal points or ‘Schelling points’ – in game theory, on which Tom had a big impact.

Tom’s most influential book was The Strategy of Conflict in which he explored how situations which looked as if they would end in conflict could be reconsidered to produce an outcome in which people cooperated. A key area to which this insight was applied was nuclear warfare, where he argued that nuclear warfare was not a zero-sum game. As others have noted, he would use the analogy of a gunfight between two cowboys to argue that as long as one gunfighter knew that if he drew his gun first and fatally wounded his rival, the other fighter would still have enough time to draw his gun and fatally wound him, therefore neither fighter would draw his gun. This was the essence of the concept of ‘mutually assured destruction.’ Tom played an important role in the 1960’s in advising US Presidents on nuclear strategy.

Tom believed that unconventional approaches, such as geoengineering, should be looked at more seriously.

At the end of the 1960’s Tom was one of the founders of the Harvard Kennedy School, which brought together scholars from different disciplinary backgrounds to tackle key policy challenges. In addition, Tom went on to make major contributions to thinking about racial segregation, traffic congestion, and climate change.

It was for his work on climate change that in 2010 we invited Tom to Manchester for a special conference on this subject in his honour. Tom had been involved in the issue of climate change since the early 80s through his membership on two National Academy of Science committees that produced important policy advice for key US decision-makers. In his insightful keynote address to the conference, Tom explained how global warming was a manageable problem from an economic point of view, but that sensible economics would not prevail any time soon. For example, we could not expect countries to adopt a simple carbon tax that was the same across nations, a standard economic policy recommendation. Tom believed that unconventional approaches, such as geoengineering, should be looked at more seriously. An example of geoengineering might be putting particles in the atmosphere to reduce warming.

Tom did not recommend limited testing of these strategies because he thought these approaches were desirable, but rather because if countries failed to get their acts together, these approaches could be necessary as a last resort. He believed strongly that we ought to better understand their risk and benefits by testing how they might work on a small scale. Tom also contributed greatly to the conference through his thoughtful comments on the presentations of other speakers.

As a wonderful friend and mentor to many economists (including ourselves), his presence will be greatly missed.

Featured image credit: Algebra analyse by Meditations. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Thomas Schelling: An unconventional economist appeared first on OUPblog.

Mrs. T and I

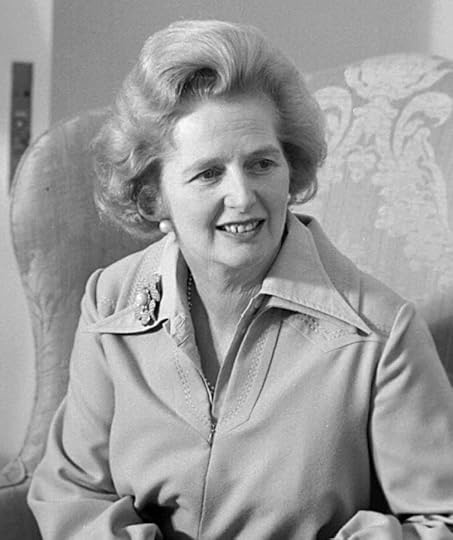

“The full accounting of how my political work affected the lives of others is something we will only know on Judgment Day,” stated Margaret Thatcher in the year 1995. The “Iron Lady” indeed affected the lives of millions, among them historian David Cannadine, whose thoughts turn to two Mrs.Ts: one was “the dominant British public figure of her generation”; the other, a formative influence on his own early life. This article is an extract from his book Margaret Thatcher: A Life and Legacy:

I first encountered what was in retrospect Margaret Thatcher’s avatar and anticipation during the autumn of 1955, when I began my formal education as a pupil at a state-funded, Church of England primary school on the western side of Birmingham. The school’s headmistress was “Mrs Thurman” (or “Mrs. T”), and she was a figure by turns unforgettable, intimidating, charismatic, and inspirational.

She was always impeccably coiffured, she often wore well-cut blue suits, she was tirelessly and overwhelmingly energetic, and when she lost her temper she was utterly terrifying, reducing not only her errant pupils, but also grown men, to quivering jelly and tearful wrecks. She was a brilliant headmistress. Her motto for her school was “Only the best is good enough”, and she constantly urged us all to strive to make the most that we could of ourselves.

It was not until later life that I came to realize just how much I owed her. Unlike many in the teaching profession of her day, Mrs. Thurman was a staunch Conservative; she was also a committed Christian, and a vehement anti-Communist, and I can still recall the speech she gave, at a morning assembly in 1956, denouncing the Soviet invasion of Hungary as an unconscionable act of tyranny and aggression.

So when Margaret Thatcher burst upon the British political scene during the 1970s, initially as Secretary of State for Education, and subsequently as Conservative Party leader and Prime Minister, I thought that I already knew something about this second “Mrs T”: for in her appearance, energy, demeanour, and attitudes she seemed to bear a close resemblance to Mrs. Thurman, albeit multiplied by a hundred.

“Margaret Thatcher” by Marion S. Trikosko. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Margaret Thatcher” by Marion S. Trikosko. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.For most of the 1980s, I lived and worked in Britain, and, like many people, I regarded Thatcher as in some ways admirable, but in others difficult to take. From 1988 to 1998, I taught British history at Columbia University in New York: Thatcher was a marvellous subject on which to lecture, she invested Britain and thus British history with renewed interest and fascination for a transatlantic audience, and she was warmly and widely admired by American Republicans, who could not understand why her own party had turned against her in November 1990.

On returning to work in the United Kingdom, I found myself sitting on a University of London committee that Margaret Thatcher chaired, and the early impressions that I had formed of her were amply confirmed. She was past her prime-ministerial prime, but it did not require much imagination to recognize and appreciate how impressive she must have been at the peak of her powers, both in terms of the extraordinary force of her intimidating personality and her complete mastery of the business in hand.

By the time Thatcher died in 2013, she had been in public life for more than forty years, she had been the dominant figure in Britain during the 1980s, I had seen how she had been regarded on both sides of the Atlantic, and thanks to the earlier encounters with Mrs. Thurman I had, albeit inadvertently, been given more than just an inkling of the remarkable person that she undoubtedly was. So when, two years ago, my colleagues at the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography urged that I should contribute the entry on her, I found the invitation – and the challenge – irresistible. It would be the largest entry for any twentieth-century prime minister since Churchill’s, but with the added complication that while some people regarded her, like him, as having been the saviour of her country, others saw her in a completely different light.

“Divisive” was the word often used to describe Thatcher, by friend and foe alike, during her decade of power and on into her retirement, and it continues to be applied in the years since her death. In writing my entry on her, I sought to be as even-handed as possible, viewing her with what I regard as a necessary and deserving combination of sympathy (she was a major historical figure, with many admirable qualities) and detachment (her critics, both inside the Conservative Party and far beyond, often had a case, although not invariably so).

She was deeply and romantically patriotic, but this was not easily reconciled with her belief in free markets, liberal economics, and globalization. “You and I,” she once told her chief press secretary Bernard Ingham, “are not smooth people.” There are times when nations may need rough treatment. For good and for ill, Thatcher gave Britain plenty of it.

Featured image credit: “Margaret Thatcher visiting Salford” by University of Salford Press Office. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Mrs. T and I appeared first on OUPblog.

How much do you know about the prophets in the Old Testament?

In the Bible, God reveals himself to humanity in a variety of ways, one major way being through the prophets. The ancient prophets were said “to possess an intimate association with God” and spoke on behalf of God as divine messengers. Revealing his divine will as “mouthpieces,” the prophets did not claim to possess special powers in predicting the future, but rather simply relayed a message from the omnipotent, omniscient Being.

Well over 3,000 years since the time of Abraham, scholars are still exploring and uncovering new insights about the ancient prophets in the Hebrew Bible. In a text with over 23,000 verses, there is quite a lot of information to be interpreted and re-examined. Not too long ago, you may have read about how “Miriam, Deborah, Hulda, Noadiah, the unnamed prophetess of Isaiah 8:3, and ‘the daughters … who prophesy’ are all women identified as prophets in the Hebrew Bible,” but do you which prophets worked miracles? Do you all know the prophets named in the Bible before the time of Samuel?

Test how much you know with the quiz below!

Quiz background image credit: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image credit: Hebrew Bible. Public Domain, via Pixabay.

The post How much do you know about the prophets in the Old Testament? appeared first on OUPblog.

January 24, 2017

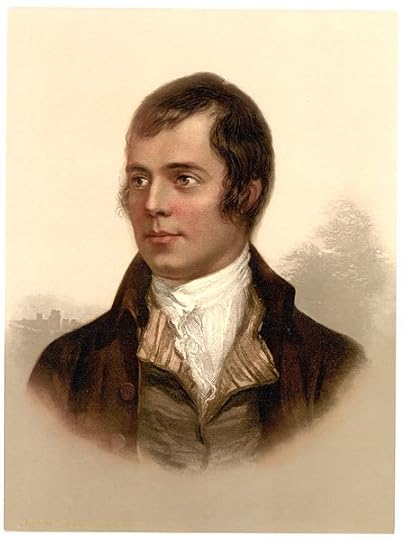

The private life of Robert Burns

It’s almost that time of year again, when families, friends, and acquaintances get together to host a Burns supper, and celebrate the life and poetry of Robert Burns. Variously known as Rabbie Burns, the Bard of Ayrshire or the Ploughman Poet, Burns is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland and indeed celebrated worldwide. At a traditional event, a speaker will recount the life of Robert Burns in an “immortal memory” – often the highlight of the evening.

Despite these speeches occurring all over the globe on 25 January, there are still some lesser-known aspects of Robert Burns’ life. For instance, did you know that he harboured a deep-rooted desire to move to Jamaica, or that he was quite the radical in terms of both international politics and religion? We’ve delved into the personal correspondence of Robert Burns to learn more about his private life and opinions. Just like his poetry, the letters mix thoughtful sentimentality with humour and coarseness, and have the power to inspire and shock in equal measure. For a truly memorable “immortal memory” read on to discover the hidden side of Scotland’s greatest bard…

Although famed as one of Scotland’s greatest patriots, Burns had longstanding ambitions to move to the Caribbean island of Jamaica. Here, he writes of “ungrateful Jean” — a reference to Jean Armour who was one of the great loves of his life:

I have run into all kinds of dissipation and riot, Mason-meetings, drinking matches, and other mischief, to drive her out of my head, but all in vain: and now for a grand cure, the Ship is on her way home that is to take me out to Jamaica, and then, farewel dear old Scotland, and farewel dear, ungrateful Jean, for never, never will I see you more!

Robert Burns was not primarily a poet by trade, but spent a large part of his life farming (at which he was particularly unsuccessful). The agricultural demands frequently took their toll on his creative life: “Portrait of Robert Burns, Ayr Scotland” from United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Portrait of Robert Burns, Ayr Scotland” from United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

I am so harrassed with Care and Anxiety about this farming project of mine, that my Muse has degenerated into the veriest prose-wench that ever picked cinders, or followed a Tinker. When I am fairly got into the routine of business, I shall trouble you with a longer epistle; perhaps with some queries respecting farming: at present, the world sits such a load on my mind that it has effaced almost every trace of the image of God in me.

Burns was not only a radical in his poetic style, but also in his political opinions. Some may be aware that he was an ardent supporter of the French Revolution — but interestingly, Burns changed his mind with the French invasion of Savoy and Holland:

As to France, I was her enthusiastic votary in the beginning of the business.When she came to shew her old avidity for conquest, in annexing Savoy, and to her dominions, and invading the rights of Holland, I altered my sentiments.

As well as politics, Burns was no stranger to scandal in the religious sphere. In his daily life as with religion, Burns was staunchly against any form of hypocrisy and false sentiment – especially what he saw as the over-zealous puritanism of the time:

But of all Nonsense, Religious Nonsense is the most nonsensical; so enough, and more than enough of it—Only, by the bye, will you, or can you tell me, my dear Cunningham, why a religioso turn of mind has always a tendency to narrow and illiberalize the heart?

Although Burns is often referenced as a womanizer (in opposition to his romantic poetry), Burns had an incredibly tender private manner, and wrote many love letters to his numerous paramours. Among these was Mrs. Agnes M’Lehose, who he wrote to as “Clarinda” in case their correspondence was ever discovered:

You are an Angel, Clarinda; you are surely no mortal that “the earth owns.” To kiss your hand, to live on your smile, is to me far more exquisite bliss than the dearest favours that the fairest of the Sex, yourself excepted, can bestow.

Ever the walking (or writing) contradiction however, Burns also held some less than traditional views on romance and marriage. Having fathered at least 12 children by at least 4 different women (and even serving public penance for one relationship), he was particularly keen to impart his wisdom to one friend:

We talk of air and manner, of beauty and wit, and lord knows what unmeaning nonsense; but—there—is solid charms for you—Who would not be in raptures with a woman that will make him £300 richer—And then to have a woman to lye with when one pleases, without running any risk of the cursed expence of bastards and all the other concomitants of that species of Smuggling—These are solid views of matrimony.

Featured image credit: “Scottish Bagpiper at Glen Coe, Scotland” by Diliff. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The private life of Robert Burns appeared first on OUPblog.

Fighting Trump’s populism with pluralist populism

Leaders and influential movements in countries such as the Philippines, Russia, Turkey, Hungary, Italy, France, Spain, Britain, Venezuela, and the United States are being called “populists.”

Sometimes that word (or its equivalent in other languages) is critical. It means that the leader has promised voters impossible or unjustifiable benefits in order to win election. No one calls themselves a “populist” in this sense; it’s an epithet.

Sometimes “populism” means advocacy for majoritarian or directly-democratic procedures, such as referenda or decentralization to local governments. That does not seem to be a major global trend at the beginning of the 21st century.

Jan-Werner Müller uses the word in a third, influential sense in his recent book, What is Populism? For him, “populists are antipluralist. They claim that they and they alone represent the people. All other political competitors are essentially illegitimate, and anyone who does not support them is not properly part of the people. [… ]The people are a moral, homogeneous entity whose will cannot err.” For instance, Donald Trump has said: “the only important thing is the unification of the people – because the other people don’t mean anything.”

I would add that this kind of populism is anti-intellectual, in the tradition that Richard Hofstadter depicted in Anti-Intellectualism in American Life (1963). Anti-intellectual populism rejects advanced, specialized, complicated thought, which is viewed as antithetical to common sense. According to Mark Fisher, Donald Trump is an explicit anti-intellectual:

He said in a series of interviews that he does not need to read extensively because he reaches the right decisions “with very little knowledge other than the knowledge I [already] had, plus the words ‘common sense,’ because I have a lot of common sense and I have a lot of business ability.” Trump said he is skeptical of experts because “they can’t see the forest for the trees.” … “ I want it short. There’s no reason to do hundreds of pages because I know exactly what it is.”

Trump seems to fit Müller’s definition precisely. However, “populism” can have a fourth and much more positive meaning. It can be explicitly and fundamentally pluralist. In her recent book Populism’s Power: Radical Grassroots Democracy in America, Laura Grattan writes:

Radical democratic actors, from grassroots revolutionaries, to insurgent farmers and laborers, to agitators for the New Deal, Civil Rights, and the New Left, have historically drawn on the language and practices of populism. In doing so, they have cultivated peoples’ rebellious aspirations not just to resist power, but to share in power, and to do so in pluralistic, egalitarian ways across social and geographic borders.

In the examples that Grattan explores, populists who celebrate “the people” (in contrast to corrupt elites) do not merely tolerate diversity or accommodate themselves to it. They are actively enthusiastic about pluralism, inventing “alternative” spaces and styles of engagement, inviting disparate actors to join in their festivals and parades, emphasizing freedom of speech and assembly as core values, and usually preferring to retain some distance from the state. In fact, one of their political liabilities is their tendency to splinter because they fear uniformity.

In this form of populism, diverse people create actual power that they use to change the world together.

In this conception, The People are not only heterogeneous; they are defined by being more pluralistic than the straight-laced elites, who promote one way of life as best for all. Furthermore, The People are not interested in surrendering their power to any leader. Their populist activity is all about building direct, grassroots, horizontal, participatory power. They are proud of their democratic innovations, whether those are letters of correspondence, Grange halls, sit-ins, salt marches, or flashmobs.

Eli Rosenberg, Jennifer Medina, and John Eligon began a recent New York Times article about anti-Trump protests: “They came in the thousands — the children of immigrants, transgender individuals, women and men of all different ages and races — to demonstrate against Donald J. Trump on Saturday in New York. Some held handwritten signs like, “Show the world what the popular vote looks like.” The throng chanted, ‘Not our president!’”

Showing the world that the popular vote looks heterogeneous is a traditional populist gambit, familiar from social movements and popular uprisings since time immemorial. It’s a way of demonstrating SPUD (scale, pluralism, unity, depth).

This form of populism is also often quite intellectual. It seeks to give everyone opportunities to study, reflect, and create knowledge. When I interviewed the great community organizer Ernesto Cortés, Jr. (Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF) co-chair and executive director of the West / Southwest IAF regional network), he told me this was his organization’s strategy:

Building talented, committed, enterprising relational organizers through recruitment, training, and mentoring. We develop their capacity to be reciprocal, relational organizers. Ask–what do Aristotle and Aquinas say? Explore the different traditions. Offer all kinds of seminars with a wide range of scholars from left, right, center. Develop their intellectual capacity, which is the capacity to be deliberative. Help them to understand labor, capitalism, the various faith traditions, strategic thinking. We offer what amount to postgraduate-level seminars in how to create effective leaders in an institutional context–not lone celebrity activists–people who build institutions that can then be networked together.

I emphasize populist pluralism because I fear we face three unsatisfactory alternatives:

Trump-style populism, which defines The People as homogeneous, excludes everyone who doesn’t fit, and disempowers the actual people by centralizing political authority in a leader.

Technocratic progressivism, which defers to a highly educated global elite whose norms and range of experiences are actually quite exclusive and narrow.

Thin versions of diversity politics, which celebrate heterogeneity within existing institutions (e.g., racial diversity within a university) but which lack a political vision that can unify broad coalitions in favor of new institutional arrangements.

We need a dose of populism that neither delivers power to a leader nor merely promises fair economic outcomes to citizens as beneficiaries. In this form of populism, diverse people create actual power that they use to change the world together.

Featured image credit: Protest march against Donald Trump by Fibonacci Blue. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Fighting Trump’s populism with pluralist populism appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers