Oxford University Press's Blog, page 410

February 5, 2017

Democracy for losers

Democracy is under threat everywhere. Growing numbers of citizens prefer authoritarian ideas, and politicians nurturing those wishes are on the rise in Hungary, Poland, France, Turkey, Germany, and the United States—to mention only the most salient examples. By now pundits everywhere have expressed concern about “populism” and the cementation of “illiberal” or “defected” democracies. Populist politicians all stress that they speak for the “people” and articulate demands that are “suppressed” by a dominating elite—that is, by a minority. Whereas Viktor Orbán and Recep Erdoğan mobilize large majorities, this is certainly not true for Marine Le Pen or Donald Trump. While these distinctions are important, they do not affect the main point at issue.

What makes the discussions complicated is the fact that democracy is threatened by democratic means: When citizens prefer authoritarian ideas, shouldn’t democracy meet these demands?

Equating democracy and majority rule is unproblematic only in societies without permanent social conflicts and rifts. If the chances of belonging to a majority are more or less evenly distributed across the population, supporting majority decisions makes sense because, in the long run, we will all belong to majorities more often than we will find ourselves among minorities. But in reality, these chances are not evenly distributed. Seven decades of empirical research on political involvement show that participation is always biased against the less privileged.

Each major expansion of the ways citizens try to influence politics—protests in the 1970s, social movements in the 1980s, voluntarism in the 1990s, political consumerism and new social media in the 2000s—has been accompanied by the claim of improving equality. None of these movements have accomplished this. Political activism remains relatively low among lower socio-economic groups. Men are still politically more engaged than women (with the dubious exception of political consumerism). Young people, especially, avoid institutionalized modes of participation. Not even the spread of social media has changed these continuous distortions of democracy’s ideal of equal voices. Those who could gain the most from political participation are the least active—permanent losers don’t like democracy.

To be frank, the empirical record of participation research is depressing. Hardly any program, project, or policy has been able to mobilize less politically active populations effectively.

If the weather vanes of political change are read correctly, we are approaching the end of a long period of biased participation.

More than twenty years ago, Sidney Verba and his colleagues succinctly enumerated the main reasons why people do not participate politically: “because they can’t, because they don’t want to; or because nobody asked.”

Much has changed since, but not the relevance of these three causes. Only recently did the first signs of what might be a changing political climate become visible: growing dissatisfaction with the causes and consequences of socio-economic hardship (financial crises, austerity politics, globalization, migration) seems to counteract Verba’s second reason. The rise of populist politicians and parties effectively takes care of the third. Theoretically, grievance theories gain renewed relevance mainly through their explanation of protest against austerity politics. For the first time since democracy started to encourage mass-participation, voices of the ‘losers’ can be heard more clearly. Not all these voices support liberal democracy unconditionally. This can only be a surprise for people who are content with the extended participation of privileged groups in existing democracies.

If the weather vanes of political change are read correctly, we are approaching the end of a long period of biased participation. But neither the vanes nor their popular readings seem to be unproblematic. First, a “crisis” of democracy requires more than the election of some populist politician or the surprising outcome of a referendum. What seems to be refuted is the optimistic but rather naïve idea that all political development is a long march towards democracy.

The second issue is that even in established democracies, parts of the population have always supported authoritarian ideas. Empirical political science scrutinized this phenomenon as early as the 1950s. Recent populism largely overlaps with this old-fashioned authoritarianism.

Third, democratic participation is not disappearing but remains increasingly popular, especially among “critical citizens.” By now, the repertoire of participation is virtually infinite and includes actions ranging from voting, to posting blogs, and buying fair-trade products.

So might we conclude, there is nothing new under the sun and defenders of democracy can sleep well tonight? Curing the most serious failure of liberal democracy—its enduring inability to involve permanent losers—is a reason for contentment. Yet the often xenophobic, intolerant, and ignorant nature of the present remedies can’t be neglected.

This brings us back to the equation of democracy and majority rule as the cardinal sin. Under majority rule, it is stupid for permanent losers to plea for democracy. But it is perhaps even more stupid for defenders of democracy to advocate their case when dealing with people who want to change the rules of the game only because they are long-time, politically absent losers. Democracy—understood as a value in and for itself—is open for both winners and losers, and not for picky authoritarians who want majority rule only.

Featured image credit: Meeting 1er mai 2012 Front National by Blandine Le Cain. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Democracy for losers appeared first on OUPblog.

Philosopher of the month: Friedrich Nietzsche

This February, the OUP Philosophy team honors Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (1844-1900) as their Philosopher of the Month. The son of a Lutheran minister who died when Nietzsche was four years old, Nietzsche’s philosophical work was largely ignored during his lifetime. When Walter Kaufmann’s 1950’s translations of Nietzsche’s key works gave the world a more accurate representation of his thought, Nietzsche became one of the most influential philosophers of the modern era.

Nietzsche was greatly concerned with basic problems in contemporary Western culture and society, which he believed were growing more acute, and for which he considered it imperative to try to find new solutions. His examination of unconscious drives found “will to power” to be a fundamental element of human nature, and metaphysically, in all of nature. The one who escapes all this, Nietzsche’s “Übermensch,” describes a person who has mastered passion, risen above irrational flux, and endowed her or his character with creative style. One of Nietzsche’s best-known ideas, “the death of God,” speaks to the unfeasibility of belief in God in late modernity, and the resulting consequences. The fundamental problem of how to overcome nihilism and affirm life without illusions was central to Nietzsche’s thought, and his skepticism of the notions of truth and fact anticipated many of the central tenets of postmodernism.

For more on Nietzsche’s life and work, browse our interactive timeline below.

Featured image: A monument to Nietzsche in the middle of Naumburg (Germany). Photo by Giorno2. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Philosopher of the month: Friedrich Nietzsche appeared first on OUPblog.

February 4, 2017

Fingering choices for musical gain in eighteenth-century piano performance

The proper use of fingering to perform accurately is of concern to all instrumentalists. However, there is a dangerous pitfall awaiting keyboard players that does not exist for other instrumentalists. Simply put, for non-keyboardists, wrong fingering usually equals wrong note. But for the pianist, we can stumble along, playing the right pitches, while all the while making a complete mess of the musical message because of inept fingering. As C. P. E. Bach cautions: “Today, much more than in the past, no one can hope to play well who does not use his fingers correctly.” Therefore, it is not surprising that C. P. E. Bach devotes 37 pages to proper scale fingerings of all stripes and colors for good execution in chapter 1 of Versuch, and Türk devotes 60 pages to the same in Klavierstücke.

What is distinctive to eighteenth-century performance practice is the acknowledgment of the important role fingering plays in musicality; how it is completely interconnected. It is inseparable from interpretation. It serves a vital musical function so much so that Bach believed the musical function of fingering was more important than its technical role.

Clementi puts it succinctly: “To produce the best effect, by the easiest means, is the great basis of the art of fingering.” The best fingering is achieved by the easiest means, which is not always a 1-2-3-4-5 legato approach. Instead, this suggests choosing fingering that supports a hand shape and execution which will facilitate a reliable technical and musical outcome. Türk demonstrates the concept well in Klavierstücke. As suggested in Discoveries from the Fortepiano (2015, OUP), try the excerpt below using consecutive fingering (1-2, 2-3, 3-4…) while at the same time following the slur indications. Now, play it with Türk’s suggestions which require one gesture, one muscle movement, gliding up and down the keyboard – the best effect by the easiest means.

Türk, Klavierstücke. 158.[3]

Türk, Klavierstücke. 158.[3]Oftentimes today, scores are interpreted with a fully-connected, legato execution. The Mozart example below is a case in point. The fingering choice suggested by the editor in the right hand on beat one of measure 33 is 2-1-2-4-5. This proposed fingering implies connecting the line through the slur which contradicts the articulation subtleties Mozart notated. If we are to play the score as directed by Mozart, this “easiest” fingering approach, in reality, becomes more difficult to execute musically and the following interpretation usually results.

Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 309/II, mm. 33-36 (Henle)

Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 309/II, mm. 33-36 (Henle)http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Audio-Example-1-Mzrt-K.-309-II-Gunn-online-audio-converter.com_.mp3

Instead, using 1-2-4-5-3 on beat one of measure 33 produces Mozart’s notated articulation by using the natural inclination of the fingers: starting with a heavier gesture with naturally heavier fingers, breaking the legato after finger 5, and landing with a rich, thick finger 3. A natural gesture followed by a newly articulated stroke. The best effect by the easiest means. Listen to the difference that is demonstrated on the fortepiano:

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Audio-Example-2-Mzrt-K.-309-II-Gunn.mp3

By following these principles on the modern piano the same nuanced interpretation is readily achieved:

http://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Audio-Example-3-Mzrt-K.-309-II-Gunn-online-audio-converter.com_.mp3

The conscious employment of this technical approach provides rational solutions to the perceived “problems” of executing eighteenth-century repertoire. The added bonus? A style that is easier to execute, that offers a variety of articulation, that contains new palettes of color, and that provides unimagined sound energy through intentionally executed technical paths.

Featured image: “Playing piano” by Nayuki. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Fingering choices for musical gain in eighteenth-century piano performance appeared first on OUPblog.

Super Bowl madness

Every year we worship at the altar of the Super Bowl. It’s the Big Game with the Big Halftime Show and the Big-Name Advertisers.

That we do this, explains why Donald Trump is now president. I’ll get to that shortly. But for now, back to the show.

From an advertising perspective, the Super Bowl is the most expensive commercial on television. This year, Fox charged upwards of $5 million per 30-second spot according to Sports Illustrated and that’s almost double what it was only ten years ago. The next closest program is the Academy Awards which gets about $2 million per commercial. Even the World Series—this year with the exciting inclusion of the Chicago Cubs—sold ads for $500,000, and that was for game seven. Advertisers are willing to pay those high prices for the Super Bowl because there is no other event when more than 110 million people of every demographic—moms, dads, kids, millennials, baby boomers—are watching in real time.

So who forked over the big bucks this year? There are many of the usual suspects, such as Anheuser-Busch (maker of Budweiser), GoDaddy (which traditionally runs a salacious ad but will tone it down this year), Pepsi, and Avocados from Mexico (which I suspect might pull out at the last minute if they can). New companies or companies trying to revive their brands, such as A 10 Haircare or Yellow Tail wine, advertise using a vast majority of their marketing budgets because they are hoping to make a big splash in a small amount of time.

Not all ads have been “leaked” prior to the game, so it is difficult to give you a best and worst. Of the ads I’ve seen, the John Malkovich ad for Squarespace is funny and entertaining, TurboTax using Humpty Dumpty to promote the ease of its services got me to laugh, and the Coen brothers do a tribute to “Easy Rider” for Mercedes which should easily appeal to its target of upscale boomers. My vote for worst thus far is a Mr. Clean ad, which shows the man in white sexily cleaning the house, a spot which has already created a lot of buzz but frankly left me flat because trying to make cleaning the house sexy is plain pushing it.

So what does all of this have to do with Donald Trump?

Since the 1930s, Americans have been framed as consumers rather than citizens according to historian Lizabeth Cohen in her book, A Consumers’ Republic. Buying products and services fueled the economy for decades, and simply going to the store was tantamount to fulfilling our civic duty. No more. As technology advanced and Silicon Valley disrupted more and more business sectors, our economy has become driven by Wall Street, not Main Street.

In her book, Strangers in Their Own Land, Arlie Hochschild explains the impact of this on our society. Middle class Americans—and particularly white, male, middle-class Americans—feel like they have been standing in line waiting for their due and everyone else is getting to jump ahead. Women got more rights, the government is helping African Americans through Affirmative Action, even endangered species are protected by environmental legislation while no one helps them. I’m not saying this is necessarily true. I’m saying this is what they perceive.

Watch TV by Pavlofox. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

Watch TV by Pavlofox. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.Integral to that perception—and something Hochschild does not address in the book—is the influence that media and advertising have on that perception. (I am not talking here about Fox News, which would take an article of its own.) Advertising and the programming in which it appears cannot but help make people feel like they are getting further and further behind. Advertisers are most interested in people with money to spend—particularly young people with money to spend—and their commercials reflect this. Imagine knowing that you can barely make a living, your home is not paid for, you didn’t go to college because you expected to work in a coal mine or a factory that didn’t require you to do so. You come home to relax and watch TV, and what is on? Shows about fabulously rich African Americans, overly educated white coastal intellectuals, and zombies. There’s no getting away from the idea that the American Dream is fundamentally broken.

A respite has been football, long the highest-rated programming on television. Unfortunately, that will likely be gone soon too. Television rights for football come up for renewal in 2021. As Barry Lowenthal, president of media buying firm The Media Kitchen states in an article on MediaPost, “Given the dominance of the streaming companies and the war chests being amassed by Amazon, Apple, Google and Facebook (FB is 14x the size of CBS), we should not assume that the broadcast and cable networks will win the next auction.” Four years down the road even this small relief will be a memory.

Businesses and celebrities have replaced government and gods. Malls have become vacation destinations. Companies implement cradle-to-grave marketing strategies. Mobile technologies enable advertisers to track us and sell to us 24 hours a day.

It makes perfect sense, then, that millions of Americans would buy into a come-on from a TV pitch man. Americans have been groomed to see advertising and business as the solution to our problems. A seemingly rich, seemingly successful businessman claimed he was going to “Make America Great Again” and more than 60 million people bought the brand.

But reality TV is far from real, and this Big Game is likely one of the last big events for advertisers. What we are seeing now is the price we pay for having paid more attention to capitalism and commerce than democracy and diplomacy.

Featured image credit: “American Football” by filterssofly. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Super Bowl madness appeared first on OUPblog.

Why is it legal to bet on the stock market but not the Super Bowl?

The upcoming Super Bowl will be the most wagered-on event of the year in the United States, just like it is every year. In most of the country, these bets are unenforceable. That is, if the loser doesn’t pay the winner, there’s nothing legal the winner can do about it. Agreements to risk money on the outcome of a sporting event, an election, or most other events are not enforceable contracts.

But some agreements to risk money on the outcome of events are enforceable contracts. The day after the Super Bowl, speculators will place bets that stock prices will go up or down, that interest rates will rise or fall, that currency exchange rates will move in one direction or another. If the loser doesn’t pay the winner, the winner can go to court and force the loser to pay.

How can we explain the difference?

This is one facet of a broader question that has been with us for centuries. There has always been a consensus that investing is necessary and should be encouraged. There has likewise been a near-consensus (one that is weaker now than it once was) that gambling is dangerous and should be discouraged. But where precisely is the line between the two? And what about speculating, which lies somewhere between investing and gambling? To answer these questions, we have always had to distinguish between two kinds of risky transactions, a good kind the law should promote and a bad kind the law should deter.

“Speculation in trade made society richer, even if it made half the speculators poorer.”

We have drawn that line differently in different eras. In the late 1700s, courts enforced wagers on horse races and presidential elections, but refused to enforce stock sales judges deemed too risky. By the mid-1800s, courts had switched positions on both issues. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there was an intense political and legal controversy over whether people should be allowed to risk money on the prices of things they do not own, such as by buying and selling grain futures without owning any grain. Today such transactions are routine.

So why did the American legal system, at a very early date, differentiate between betting on sports and betting on the stock market? It wasn’t because one is luck and one is skill. Both have always involved a mixture of luck and skill, and it’s hard to say which involves more of which. It wasn’t because of concerns about corruption. Sports gambling can give athletes an incentive to play poorly and bet on their opponents (or receive payments from gamblers who are betting on their opponents), but stock gambling can likewise give the managers of corporations an incentive to manage poorly and sell the stock short. This was perceived as a serious problem in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and it was handled not by banning stock speculation, but by prohibiting insider trading.

The difference between betting on sports and betting on the stock market—and more broadly the distinction between unlawful gambling and lawful speculation—was based primarily on the idea that risk is tolerable as a means to some greater end, but that it is not a worthwhile end in itself. In the transactions proscribed as wagers, such as bets on horse races and card games, there was no purpose beyond the participants’ enjoyment of the risk itself. The transactions approved as speculation, on the other hand, involved some other useful societal end, even if the risks associated with speculation were indistinguishable from the risks associated with gambling. Speculation in trade made society richer, even if it made half the speculators poorer. Speculation in corporate shares gave rise to valuable new enterprises, even if it beggared some of the shareholders. The line between speculation and gambling was often difficult to draw with precision, but this was the intuition behind the widespread view that some such line had to be drawn.

Such lines have never been permanent, however, and this one is showing signs of weakening. As gambling has lost some of its moral stigma over the past few decades, the enjoyment of risk for its own sake has increasingly come to be understood as little different from other forms of entertainment. If this slow change in conventional thought continues, it may not be long before wagers on the Super Bowl become just as enforceable as wagers on the stock exchange.

Featured image credit: “American-Football” by filterssofly. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Why is it legal to bet on the stock market but not the Super Bowl? appeared first on OUPblog.

How much do you know about cancer?

One of the defining battles of modern medicine has been the ongoing fight against cancer, a disease that has no doubt affected many of you either directly or indirectly. Whilst there have been huge advances in detection and treatment, cancer remains a major global health problem, with 8.2 million people dying from the disease every year.

World Cancer Day aims to save millions of preventable deaths each year by raising awareness and education about cancer. We wanted to help out too, so we reached out to some of our authors and put together a short quiz to test your knowledge of the disease. Give it a go, and let us know how you do!

Featured image credit: Cancer cells by Dr Cecil Fox. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How much do you know about cancer? appeared first on OUPblog.

Gender, medicine, and society in colonial India

The growth of hospital medicine in 19th century India created a space–albeit a very small one–for providing Western-style healthcare to female patients. The earliest institutions devoted to women’s health were lock hospitals that treated prostitutes suffering from venereal diseases. In 1840, a large lying-in hospital was constructed in the grounds of the Calcutta Medical College in Bengal. However, the overall number of female patients attending medical institutions remained very low and it was argued by both the British and Indians that women were averse to treatment by male physicians. The real need to organise healthcare for these female patients made it comparatively easy for the administration to form a moral consensus on women’s medical education.

In Calcutta, the Director of Public Instruction supported the demand for women’s entry into Calcutta Medical College (CMC) and, in the face of opposition from the College Council, pushed the measure through with the support of the Lieutenant Governor. The first beneficiary of this new ruling was Kadambini Basu (Ganguli) who was admitted to the CMC in 1883. In 1886, she became the first female medical practitioner to practice in India.

In 1885, the Dufferin Fund was inaugurated to promote Western medicine for Indian women and proceeded to open many hospitals and dispensaries that provided employment for female doctors. Newfound medical education and employment as doctors gave women financial security and were an important to step in the recognition of women’s right to better health. They also exposed the policy of racial discrimination practised by the colonisers and the prevalence of sexism in society.

Discourses on sexuality and domestic practices that emerged in 19th century Bengal focused on remodelling women’s role as health-conscious wives and mothers. Medical and quasi-medical literature of this period contained guidelines for an ideal housewife that included proper home management, scientific nurturing of children, the regulation of dietary habits, and the creation of hygienic environments. Women were expected to have some knowledge of all available forms of treatment including folk medicine, allopathy, homeopathy, kabiraji, and hakimi.

Throughout the colonial period, attempts were made to modernise reproductive health by reforming birthing practices. Traditional birthing practices were under the scrutiny of both Bengali and British reformers. Missionaries and British doctors believed that the practices promoted by the midwives or birth attendants or dhais–who were generally lower caste Hindus or poor Muslims–were some of the main causes of the appallingly high rates of maternal mortality. In an attempt to rectify the situation, books were published to educate women in reproductive health practices and midwifery training courses were introduced; however, these failed to attract many practitioners.

…the reform of reproductive healthcare and the spread of women’s medical education, benefitted a privileged minority belonging to urban, higher-caste groups.

Late colonial India saw the emergence of preventive healthcare. A greater focus was placed on disseminating and popularising health education among women through different agencies. There was also growth of voluntary associations devoted to maternal and child healthcare. Under the influence of eugenics movements, the health of nations such as India became associated with increasing the physical strength and purity of the ‘race’, scientifically brought up by hygienically enlightened mothers.

One notable feature of 20th-century health reforms for women was the role played by women’s organisations that conducted training programmes, participated in baby shows and health week celebrations, and other projects intended to improve maternal health. Despite these efforts, women died in large numbers during the famine of 1943. This was partly due to famine induced epidemics but also because of abandonment and destitution leading to the adoption of survival strategies that negatively affected health. The famine exposed how poor health status among women and children made them extremely vulnerable, particularly when faced with the inefficiency of public health administration and dietary deficiencies.

As conditions improved, some female patients were offered more choice in their healthcare practitioners. However, these diverse forms of healthcare were mostly available to a handful of women residing in urban and semi-urban areas. Female healers who had existed in the pre-colonial period were gradually marginalised in the growing sphere of bio-medicine and ‘reformed’ indigenous medicine.

If one looks at the evolution of public healthcare administration and female mortality figures in the colonial period, it becomes clear that women’s health received less official attention than men’s health. Many of the changes, including the reform of reproductive healthcare and the spread of women’s medical education, benefitted a privileged minority belonging to urban, higher-caste groups. While voluntary agencies and women’s organisations continued to improve the health conditions of underprivileged women, disparate health outcomes remained a significant aspect of the history of women and medicine in colonial India.

The changes that took place in women’s healthcare in colonial India constitute a significant chapter of the country’s social history and laid an irrevocable foundation for medicine in the post-independence period.

Featured image credit: Calcutta Medical College and Hospital by Diptanshu.D. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Gender, medicine, and society in colonial India appeared first on OUPblog.

Guaranteeing free speech

In a blog post heard ’round the oral history world, Zachary Schrag broke the news that the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects was finally amended to deregulate oral history. This new regulation, the result of decades of work by a determined group of scholars, is as exciting as it is complicated, so today on the blog we’re offering a meta-summary of some reflections on this change.

A post on the Oral History Association’s blog succinctly clarified the rule change.

The most critical component of the new protocols for oral historians explicitly removes oral history and journalism from the regulations…The new protocols will take effect on January 19, 2018.

Schrag’s blog post offered a detailed explanation of the technical language, and the differences between the early Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) and the final regulation.

The final rule preserves and clarifies the NPRM’s deregulation of oral history. This is a great victory for freedom of speech and for historical research.

The NPRM somewhat confusingly listed a number of activities “deemed not to be research” in §__.101, then presented the definition of research itself in §__.102. The final policy more logically defines research, then lists “activities…deemed not to be research.”

Whereas the NPRM excluded “Oral history, journalism, biography, and historical scholarship activities that focus directly on the specific individuals about whom the information is collected,” the final rule offers a broader exclusion:

For purposes of this part, the following activities are deemed not to be research: (1) Scholarly and journalistic activities (e.g., oral history, journalism, biography, literary criticism, legal research, and historical scholarship), including the collection and use of information, that focus directly on the specific individuals about whom the information is collected. [§__.102(l)(1)]

So freedom depends on the activity, not the discipline, with literary critics, law professors, and others who interview individuals benefiting. Another section of the announcement notes that this provision will also apply to political scientists and others who hope “to hold specific elected or appointed officials up for public scrutiny, and not keep the information confidential.”

The post went on to explain the reasoning, and another post on the blog details the consequences of the change for social scientists.

The National Coalition for History weighed in with some background on both the change and the contentious relationship between historians and IRB procedures.

[The regulation] was originally promulgated as the “Common Rule” in 1991. The historical community, collaborating through the National Coalition for History, has long argued that scholarly history projects should not be subject to standard IRB procedures since they are designed for the research practices of the sciences…

Beginning in the mid-1990s, college and university students, faculty, and staff who conducted oral history interviews increasingly found their interviewing protocols subject to review by their local Institutional Review Board (IRB), a body formed at every research institution, and charged by the federal government with the protection of human subjects in research. Human subject risk regulation had its roots in the explosion of government-funded medical research after World War II as well as with the revelation of glaring medical abuses, including Nazi doctors’ experiments on Holocaust victims and the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. History and other humanities disciplines were never originally intended to fall within the purview of the regulation, generally known as the “Common Rule,” which addressed biomedical and behavioral research.

The growing inclusion of oral history under IRB review began an often contentious, confusing, and chaotic process. Was oral history—or historical studies more generally—the type of “generalizable” research covered by the Common Rule?

The post drew on an article written by Linda Shopes that clarified the process and what was at stake before the rule had passed.

Finally, Mary Marshall Clark, Director of the Columbia Center for Oral History Research, offered some perspective for the change, focusing on the motivation driving those who sought it.

The technical arguments we made will not stand out in the historical record; the spirit that actually motivated so many arguments regarding the application of the policy was our resolute determination to remind the board that oral history is part of protecting the right to free speech and free inquiry.

In that sense, we were not thinking of protecting narrators as potential victims, but protecting their right to speak freely and openly as citizens and agents in a democracy that guarantees free speech.

While the change will not take effect until 2018, we are excited at the opportunities this change will create for recording and preserving the voices of people who might otherwise be denied a space to speak. We welcome additional analysis, summaries, and guides, so please add to this collection in the comments below or on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, or Google+.

Featured image: “Liberty” by Mobilus In Mobili, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Guaranteeing free speech appeared first on OUPblog.

February 3, 2017

Physical therapy and rehabilitation research – looking forward

Almost everyone has been treated—or knows someone who has been treated—by a physical therapist. The field of physical therapy encompasses not only rehabilitation after injury and surgery but also a wide range of preventive health services and vital lines of research. Dr. Alan Jette, PT, PhD, Editor-in-Chief of Physical Therapy (PTJ), the scientific journal of the American Physical Therapy Association, shares his vision for PTJ and his take on opportunities and challenges for the physical therapy profession.

What led you to the field of physical therapy?

Like many, my first exposure to physical therapy was as a patient. As an 11-year-old boy, I fell from a high tree house and fractured my right femur and both wrists. After weeks in traction, I needed considerable rehabilitation to help in my recovery. Subsequently, as an undergraduate student in western New York, I worked as an orderly in a local nursing home and rehabilitation center where I was first introduced to the emerging field of geriatric rehabilitation. That experience led me to change my major from sociology to physical therapy.

How and when did you get involved with Physical Therapy (PTJ)?

Dr. Jules Rothstein, former editor-in-chief of PTJ, first encouraged me to get involved in PTJ. At the time, we were both fellows of the rheumatology association and doing similar research in scientific measurement. Through his encouragement and support, I served on the PTJ editorial board from 1990–1996 and as deputy editor from 1993–1996. I also served as acting editor-in-chief of PTJ in 2005 after the untimely passing of Dr. Rothstein. Involvement with PTJ has been the major way in which I have tried to give back to the profession of physical therapy.

Describe what you think PTJ will look like in 20 years and the type of articles it will publish.

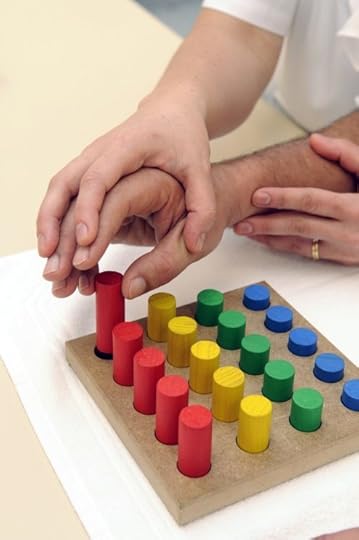

Physical therapy by hamiltonpaviana. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

Physical therapy by hamiltonpaviana. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.I see PTJ becoming the top international rehabilitation science journal that focuses not only on publishing the best in rehabilitation science, but on using various forms of social media to help move new evidence into rehabilitation practice worldwide.

What is the most important issue in the field of physical therapy right now?

In my opinion, in the United States, the major challenge for the profession is to expand its role as a key member of the health care team. Fulfilling our potential there will be difficult without also overcoming other significant challenges, such as patient access barriers and narrow and restrictive payment policies.

Are there any areas you think are overlooked?

Due to payment barriers, physical therapists are not involved enough in population health and prevention of disease and disability.

How would you describe PTJ in three words?

Science, Scholarship, Global.

Tell us about your work outside the journal.

The focus of my research is on the science around disability: its definition, measurement, epidemiology, prevention, and treatment. As a physical therapist who is a professor of health policy and management in a school of public health, I work on the boundary between population health and rehabilitation. My current research involves preventing disability among adults with spinal cord injury, helping create a center devoted to active aging, and implementing a major project aimed at helping the US Social Security Administration develop and use standardized approaches to examine human functioning that relates to an individual’s ability to work. Each year, I teach a doctoral level course on scientific measurement at the MGH Institute of Health Professions in Boston. I also serve on several panels of the National Academy of Medicine related to disability and population science and policy.

Feature image credit: “Senior Male Patient Working With Physiotherapist In Hospital” by monkeybusinessimages via iStockphoto.

The post Physical therapy and rehabilitation research – looking forward appeared first on OUPblog.

An introduction to the life of Frederick Douglass

In honor of Black History Month in the US and Canada, we’ve put together an introduction to Frederick Douglass. Known for his work as an abolitionist and women’s rights supporter, Douglass remains one of American History’s most influential figures.

But who was Frederick Douglass? Read below to find out.

He was born into slavery.

Born in 1818, Douglass was separated from his mother Harriet Bailey at birth, although she would visit him at night when she could. Douglass lived with his maternal grandmother until the age of seven, when he moved to the Wye House plantation run by Aaron Anthony, whom Douglass suspected could be his father. When Anthony died, Douglass was sent to Hugh and Sophia Auld in Baltimore.

Sophia Auld began Douglass’s initial education, teaching him the alphabet. Her husband Hugh discouraged this relationship, believing that education and slavery were incompatible. Douglass, however, continued to teach himself to read, later writing: “The very decided manner with which he spoke, and strove to impress his wife with the evil consequences of giving me instruction, served to convince me that he was deeply sensible of the truths he was uttering.”

Anna Murray, married to Frederick Douglass for 44 years. “Photograph of Anna Murray Douglass” first published in Rosetta Douglass Sprague, “My Mother As I Recall Her”, 1900. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Anna Murray, married to Frederick Douglass for 44 years. “Photograph of Anna Murray Douglass” first published in Rosetta Douglass Sprague, “My Mother As I Recall Her”, 1900. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.He escaped from slavery with the help of his first wife

Douglass successfully escaped slavery by boarding a train to Maryland in 1838. Anna Murray, a free black woman whom Douglass had met the previous year, assisted Douglass by providing him with part of her savings to cover his travel costs. She also gave him a sailor’s uniform she obtained from her work as a laundress, which Douglass wore as he journeyed through Delaware. Douglass travelled by steamboat to the free state of Pennsylvania, and continued on to a safe house in New York City. His entire trip took him only 24 hours. Once he arrived at the safe house, Douglass sent for Murray to meet him in New York. They were married eleven days later, on 15 September 1838.

He was an abolitionist.

In 1845, Douglass began printing The North Star, a weekly anti-slavery newspaper named in reference to runaway slaves, who were taught to follow the North Star. As he became more involved in the abolitionist movement, Douglass continued to believe in nonviolent means of resistance and the importance of education. The Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society hired Douglass as a speaker, and he toured and lectured on his experiences as a slave. During the years leading up to the Civil War, Douglass became one of the most renowned speakers on abolition in the country.

He supported women’s rights.

Douglass was the only African American to attend the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848. While there, suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton proposed a motion to pass a resolution asking for women’s suffrage, which many of the attending assembly members rejected. Douglass spoke in favor of Stanton’s resolution, stating the importance of women’s involvement in politics. After his speech, the attendees voted to pass the resolution.

Douglass and Stanton later had a falling out over the Fifteenth Amendment, which declared that the right to vote could no longer be denied on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. Stanton feared that the amendment would cause the women’s movement to lose support, but Douglass recognized that attaching women’s suffrage to the rights of black men would likely cause the amendment to fail. Despite his support for the Fifteenth Amendment, however, Douglass remained a supporter of women’s rights.

He captured his life in Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave.

In 1845, Douglass published Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, a memoir that portrayed his life as a slave and his journey to becoming a free man. Its publication heavily influenced the abolitionist movement.

Featured image credit: “Front page of The North Star newspaper, Rochester, New York” via Library of Congress. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post An introduction to the life of Frederick Douglass appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers