Oxford University Press's Blog, page 428

December 16, 2016

(Un)balancing power: What happens when states can pursue or shed military strength?

War is the ultimate “or else” in international relations. Beliefs about what will happen if states fight to the finish shapes the agreements reached in its shadow, their ability to avoid war, as well as its duration and terms of settlement. Yet in many discussions of the link between military power and war, the agents in our theories rarely make decisions over just how powerful to be. Some are strong and some weak, some rise and some decline, yet in most cases the ability to threaten and wage war is given exogenously. We’ve learned a lot from models that assume relative power to be fixed, but it’s worth asking what we can gain from a better understanding of how powerful states choose to become. States have significant choices to make over their ability to say “or else” when negotiating with their adversaries, and students of war and peace can learn from engaging (and then expanding) the basic distinction between internal and external sources of military power.

First, military coalitions are an obviously endogenous form of military power. They have a uniquely strong record of military success in interstate war over the past two centuries, and popular (and maybe apocryphal) grumblings about the difficulties of working with friends and allies notwithstanding. War coalitions allow states to purchase extra military power, and the fact that coalition partners dramatically increase the odds of success in observed wars implies that we should perhaps be careful when calculating strictly dyadic distributions of power in theoretical and empirical models of the onset of war. Some apparent power distributions aren’t what they seem when states can build coalitions. This also suggests (to me, at least) that the prospect of changing alignments might represent a class of shifts in the distribution of power that are consciously chosen by states—and that might prompt their adversaries into preventive war.

Second, the production of a state’s own military power is a domestic-political issue. The record of war finance since 1950 shows that, while democracies cut nonmilitary spending less than dictatorships, the two regime types don’t appear terribly different in their resources to taxation, debt, or inflationary policies. How states can be expected to pay for their wars is undoubtedly key to others’ estimates of their ability to sustain a lengthy fight. This logic also figures into decisions over preventive war, such as Japan’s decision to attack Russia in 1904. Also notable, however, is the importance of another Russian choice over how much power to develop in the region: the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway, which allows it to project power across Manchuria and into Korea. This helped prompt a preventive war, but it also raises another puzzle: why do some states choose to become more powerful in such a public way, when doing so risks a preventive war? Streich and Levy’s answer relies on asymmetric information, but we can imagine that competing incentives from domestic opponents pose a fatal dilemma for national leaders in cases like this.

States have significant choices to make over their ability to say “or else” when negotiating with their adversaries.

Finally, the American rise to global preeminence addresses the question of why the United States adopted the grand strategy of a European great power after the Second World War, but not the First. Preponderance was a feasible goal in 1919, with millions of American troops on the ground in Europe and a tremendous amount of financial leverage over the victorious Entente, for the United States to enter the global fray, and yet it would wait a generation before engaging in more traditional great power politics. Thompson finds the answer in the application of a model of policy change, but there is also an implicit idea that when some countries make choices over how much power to acquire (or to shed), they have a greater impact than others. Further, these decisions are endogenous to the strategic environment, and that’s not trivial. The United States didn’t gain as much in a relative sense after WWI as after WWII, but it still could have embraced a more active role in shaping the European balance of power that Nazi Germany would go on to try to unhinge twenty years later.

The cited research answers important questions about interstate war, and they identify facts that create new puzzles—e.g., why aren’t democracies using their wartime credit advantage? But the common vocabulary in terms of states choosing how much power to acquire, shed, or wield, relates to other major lines of inquiry. How do expectations about war finance influence the outbreak of war? How does the ability to build a coalition influence the escalation of crises to war in the first place? Why do some states engage in public attempts to increase their military power that should, ostensibly, carry a risk of preventive war? Finally, how does one state’s decision to exploit its potential rise to great power status, or to walk away from the commitments it entails, affect the broader currents of great power politics? These questions emerge in different forms throughout the literature on power and war, and offer new ways of thinking about them that should be a boon to researchers working on a wide range of questions.

Featured image credit: military men departing service by skeeze. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post (Un)balancing power: What happens when states can pursue or shed military strength? appeared first on OUPblog.

From Miss Havisham to Ebenezer Scrooge: playlists for Dickens’ characters

Charles Dickens is one of the most famous novelists of all time. The energy which surges through his writing brings the Victorian world to life, and his lively ensemble of characters has seeped from his pages, deep into popular culture. There are roughly two thousand named characters in his novels, and many more unnamed. T.S. Eliot wrote that ‘Dickens excelled in character; in the creation of characters of greater intensity than human beings’. Modern retellings of his tales bring these characters into our contemporary world, from Alfonso Cuarón’s 1998 film Great Expectations to Richard Donner’s Scrooged (1988). In the playlists below, we imagine what some of his most famous characters might listen to if they had access to our modern musical offerings.

Miss Havisham (Great Expectations)

The jilted Miss Havisham is one of the most iconic of all Dickens’ characters. After finding out on the morning of her wedding that her fiancé had defrauded and abandoned her, she suffered a breakdown. At the beginning of the novel she is in her mid-fifties, sat at a table displaying the uneaten wedding breakfast and cake, and still clad in the wedding dress she was wearing when she received the news. As far as bad break-ups go this has got to be one of the worst, so we’ve prepared a playlist for the ultimate post break-up wallow. What would you add? Let us know in the comments below.

Miss Havisham, in art by Harry Furniss from the library edition of Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Miss Havisham, in art by Harry Furniss from the library edition of Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Ebenezer Scrooge (A Christmas Carol)

As Christmas approaches and every high street store, supermarket and overeager colleague plays Christmas songs on repeat, this playlist might appeal to more of us than the original Christmas-hater. Embrace your inner Scrooge with ‘I Don’t Believe in Santa Claus’ by The Vandals and ‘Blue Christmas’ by Elvis Presley. Bah! Humbug!

The Artful Dodger (Oliver Twist)

Although we can’t imagine a more perfect accompanying song than ‘You’ve Got to Pick a Pocket Or Two’ for the Artful Dodger – aka Jack Dawkins – we’ve chosen an eclectic mix for this larger than life cockney character. Despite being a thief and therefore ultimately punished by Dickens, he brings wit and sparkle to his trial, saying ‘my attorney is a-breakfasting this morning with the Wice President of the House of Commons’. He would surely swagger around London, hat on the top of his head, hands stuffed into his corduroy trousers, headphones on, and listening to ‘Been Caught Stealing’ by Jane’s Addiction.

Illustration of Mrs Gamp by Frederick Barnard. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Illustration of Mrs Gamp by Frederick Barnard. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Wilkins Micawber (David Copperfield)

‘Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen pounds nineteen and six, result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds ought and six, result misery.’ I think we can all identify with that logic! Micawber is considered to be a mirror of Dickens’ own father, and the portrait is mostly fond. His relentless optimism in the face of heavy difficulties could be seen as inspirational. He would almost certainly have listened to Journey’s ‘Don’t Stop Believin’ in debtors’ prison.

Mrs Gamp (Martin Chuzzlewit)

The wonderfully vivid character of Mrs Gamp is known to be a lover of drink. Indeed when she appears ‘a peculiar fragrance was bourne upon the breeze, as if a passing fairy had hiccupped, and had previously been to a wine vaults’. Pub classics would likely feature on Mrs Gamps’ playlist of choice, including the festive ‘Fairytale of New York’ by The Pogues and Kirsty MacColl. She also always carries an Umbrella with ‘particular ostentation’.

Featured image credit: Detail of an original George Cruikshank engraving showing the Artful Dodger introducing Oliver to Fagin. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post From Miss Havisham to Ebenezer Scrooge: playlists for Dickens’ characters appeared first on OUPblog.

December 15, 2016

Feeling me, feeling you: link between sensory and social difficulties in individuals with autism?

Altered touch processing in the brain might denote a crucial link between sensory and social difficulties related to the autism spectrum. The work of Eliane Deschrijver and her colleagues, conducted within the novel research centre EXPLORA (Ghent University) shows that individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) may have difficulties to determine which observed tactile sensations belong to the movements of someone else.

Individuals with ASD experience tremendous social difficulties. They often fail to take turns in conversations and have a hard time maintaining and understanding age-appropriate relationships such as being in love, or having a friend. On top of that, many individuals with ASD are over- and/or under-sensitive to sensory information. Some feel overwhelmed by busy environments such as supermarkets; others dislike being touched, or are less sensitive to pain.

Theories trying to understand the core problems in ASD have focused mainly on either social difficulties or on sensory problems related to the spectrum. Social theories have claimed that individuals with ASD may have a ‘broken’ mirror neuron system for instance, suggesting that they don’t process or ‘mirror’ movements of others in brain areas designated for processing own movements. Sensory theories have for example claimed that individuals with ASD primarily focus on details or are more sensitive to the natural variability inherent to sensory information. However, so far our understanding of how sensory difficulties relate to social-cognitive problems is relatively poor. This is remarkable, because in fact everything we know about other people comes through our senses. If sensory processes are altered in the brain of individuals with ASD, it may affect the way they understand others. In this respect, it will not come as a surprise that surveys have found strong associations between the severity of everyday sensory problems experienced by individuals with ASD and their actual social difficulties.

Michelangelo by PublicDomainPictures. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Michelangelo by PublicDomainPictures. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.Yet, of all senses affected in ASD, altered touch processing is the strongest predictor of social difficulties. Why is this the case? Researchers of Ghent University (Belgium) think this may have to do with the important role of touch when distinguishing between self and other. Distinguishing between self and others based on vision or audition proves quite difficult; what you see or hear when someone else is making a movement is quite similar to what you see or hear when making this movement yourself. This stands in contrast with the sense of touch. When performing an action that leads to a tactile sensation, you expect to feel a tactile sensation that corresponds to this observation. If your own touch tells you something else, the tactile sensation you see will probably belong to another person and not to you. The brain can thus understand others by signaling observed tactile sensations that do not correspond to the own sense of touch, the researchers reasoned. If, in contrast, the brain of individuals with ASD would fail to signal observed tactile sensations that do not correspond to felt touch, this may explain at least parts of their social difficulties.

Using electro-encephalography (EEG), they investigated how the human brain uses own touch to understand tactile sensations in observed actions of others. To do so, they developed a computer experiment in which a human or wooden hand touched a surface with the middle or index finger, while the participant received a tactile sensation to either the corresponding or the non-corresponding fingertip. A first study in healthy adults, published last year, showed that the human brain signals within one third of a second when the tactile sensation of a human hand doesn’t correspond to own felt touch, making it most likely that the observed touch isn’t one’s own. While the human brain knows that wooden hands do not feel touch, observed ‘tactile sensations’ of wooden hands that mismatched own touch were not signaled by the brain.

This process was significantly altered in the brain of adults with ASD as compared to that of a matched control group. A second study, published in September 2016, showed that the brain of adults with high functioning autism signaled to a much lesser extent when an observed touch sensation consequent to the action of a human hand did not correspond to own touch. While these individuals did not show diminished processing of others actions per se, the results contrast claims that these individuals had a “broken” mirror system. Rather, the findings suggest that the brain of individuals with ASD may determine less well whether or not observed touch belongs to the movements of someone else, necessary for distinguishing between self and others on the basis of touch. Remarkably, those individuals with high functioning autism that had reported more severe sensory issues showed a stronger disturbance of the neural process, and expressed stronger social struggles in daily life.

It is the first time that a link could be identified between the way individuals with ASD process tactile information in their brain, and their social difficulties. The findings may thus denote a novel and crucial theoretical link between sensory and social difficulties in ASD. It is however, too early to formulate recommendations for the clinical field on the basis of this explorative study. The results should first be replicated in other samples, such as (young) children with ASD. The outcomes primarily lead to a better understanding of the complex disorder, and of associated difficulties: indeed, the sense of touch may play a more crucial role in ASD than previously thought.

Featured image credit: “Hands series” by Marco Michelini. Public domain via Free Images.

The post Feeling me, feeling you: link between sensory and social difficulties in individuals with autism? appeared first on OUPblog.

Quote the quote: how well do you know your Victorian novels?

When the description “Victorian” is brought up, the image of corseted and bustled women in flouncing petticoats comes to the minds of many. Familiarized through film culture and popular imagination, many representations of the era are preserved through the literature of that period. Countless remakes and references to Victorian novels have been made throughout the centuries, making their authors household names. From Jane Eyre, Wuthering Heights, to Sherlock Holmes, these characters represent an age of change; a society where every aspect of conduct underwent rapid transformation: steam engines advanced technological production, urban development demanded coal mining, global exploits encouraged travel writing, and the rising awareness of feminists brought about discussions on gender.

With so much change going on in every dimension of life, it is difficult to truly define what characterizes Victorian literature. With change, however, there must be the struggle to adapt. The period, named after Queen Victoria, who ruled from 1837 to 1901, raises concern over the issues of the time. Many writers sought to appeal to a wider audience than ever before, speaking in a more colloquial fashion about poverty, class, and socio-economic problems to the middle and lower-class, while also helping to shape their taste in literature. This attempt to reach a wider audience was how serialization came to be, most notably used by novelist Charles Dickens, whose serial novels featured in newspapers and magazines brought him immense fame and fortune. It also helped catapult the status of the novel–once considered a lesser form of fiction–into eclipsing the popularity of poetry from the previous Romantic era.

Later Victorian novelists confirmed the initial popularity of novels by not only addressing contemporary problems, but also devising exquisitely-detailed plot lines and well-developed characters that rival the artistry of poetry. Thomas Hardy, George Eliot, and Lewis Carroll all signify the successful transition of the novel’s stardom, a preference that prevails and influences writers till this day. Whether it is intricate conspiracies or tragic love stories, try out our quiz below to see how many of Victorian literature’s most famous lines you can name.

Featured Image Credit: The Poultry Cross, Salisbury, painted by Louise Rayner. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Quote the quote: how well do you know your Victorian novels? appeared first on OUPblog.

December 14, 2016

An ax(e) to grind

That words travel from land to land is no secret. I do not only mean the trivial borrowings of the type known so well from the history of English. For instance, more than a thousand years ago, the Vikings settled in most of Britain, and therefore English is full of Scandinavian words. Some time later, the French conquered the country, and, as a result, two thirds or so of the words one finds in Webster’s dictionary are of French origin. Cultural cross-currents are equally obvious: the language of music is full of Italian terms, and the language of art testifies to the influence of French and Italian on English. All this is trivial information. It is much harder to trace the history of migratory words, for instance such as denote the names of tools. A case in point is the origin of the word ax (or, if you prefer the British spelling of it, then axe: an extra letter at the end of a word never hurts).

A stone ax. This is how the migration of the thing and the word began.

A stone ax. This is how the migration of the thing and the word began.All the Old Germanic languages had cognates of ax, though the forms were not identical: Old Engl. æx ~ eax (æ was pronounced as a in Modern Engl. ax), alongside ex ~ øx, acus ~ akus ~ ackus, and akis elsewhere. Modern German Axt got its final t later. The most dissimilar form is Gothic aqizi. Gothic was recorded in the fourth century, but this does not necessarily mean that aqizi is the oldest Germanic form of our word. At that time, the Goths lived on the shores of the Black Sea and could have had a regional (“peripheral”) form, not current in other Germanic languages. Yet there is no doubt that we are dealing with the same name. The familiar search of etymologists for the so-called protoform will not bother us here. We can skip the details and make do with the conclusion that some word like ak(w)is– was known to all the Germanic speakers but existed in several shapes.

The usual next question is whether our word has non-Germanic cognates. In Latin, we find ascia “ax,” and, if ascia goes back to acsia, the match is perfect. The change from sk to ks is trivial: for example, at one time, half of the English-speaking world pronounced asked as aksed. Many people still do so. But the consonant k in acsia cannot correspond to k in Germanic, unless acsia ~ aksia goes back to agsia, whose root was ag– “sharp,” with g devoiced before s. Greek aksīnē (stress on the second syllable) also had k and also meant “ax; hatchet.”

Here is a hatchet man. Why not an ax-man? It would be nice to be able to sing something like: “All theses axes now pay taxes”

Here is a hatchet man. Why not an ax-man? It would be nice to be able to sing something like: “All theses axes now pay taxes”The double gloss (“ax; hatchet”) is less innocuous than it seems. In order to reconstruct the ancient meaning of a word, it is necessary to have a clear picture of the thing it designated. Thus, an ax is not quite the same as a hatchet, and a root meaning “sharp” is perhaps a better match for a knife than for an ax. (Incidentally, the origin of knife is most unclear.) The idea of sharpness comes up more than once in dealing with ancient tools. For instance, hammer meant “hammer” and occasionally “stone” in Germanic (to be more precise, in Old Icelandic), and Russian kamen’ “stone” is its secure cognate. According to one opinion, the root of the word hammer also meant “sharp.” So we are left with sharp axes and sharp hammers, though, in principle, axes are for hewing, while hammers are for hammering away. This is what the great god Thor’s hammer did: it broke the enemies’ heads to smithereens.

I’ll leave out of discussion the idea that the Indo-European name of the ax is a blend. The hypothesis is too speculative; yet I will soon resort to a version of it in promoting my own etymology of another word. If the Germanic, Latin, and Greek names of “ax” are related, the word in questions must be very old indeed, for axes are among the most ancient tools human beings invented. Surely, some axes were known long before the family we call Indo-European came into being. Hence the idea, promoted by some, that the word we are dealing with was borrowed from some lost pre-Indo-European language. (It may not be entirely inappropriate to observe that the origin of Indo-European and the genesis of its speakers remain matters of involved debate.) In the Indo-European languages, many words for “ax” have been recorded. The ghost of a substrate is ever-present in this area of research.

A parallel to the history of ax is the history of adz (again, if such are your predilections, adze). Unlike ax, it has no cognates, though the word already existed in Old English. Until the seventeenth century, its standard form was addice, very much like Old Engl. adusa ~ adesa. It will now not come as a surprise that some researchers tried to interpret the original root of adz as meaning “sharp.” Also, quite naturally, there have been attempts to connect adz and ax. Those attempts have been unsuccessful and are now forgotten. I will pass by an elaborate discussion of a Hittite word resembling adz. Its meaning and origin are unclear (to say the least), and nothing is less productive than explaining one opaque word by referring to another word, equally or even more opaque (obscurum per obscurius).

At first sight, more promising are Italian azza “battle ax” and Spanish azuela “adz,” but it has been shown that the Romance words were borrowed from Germanic (Franconian, to be precise). Those interested in details will find all the information they need under hatch, hack, hash and hatchet in English etymological dictionaries and under Hacke “hoe, mattock” in dictionaries of German. Unfortunately, today the words hacker and hacking are known only too well, to need an elaborate explanation.

The names of tools were among the most common migratory words in the Middle Ages. Russian topor (stress on the second syllable), Finnish tappara, and Middle Persian tab’ar are among them. They mean “ax.” The Anglo-Saxons did not stay away and had taper-æx “a small ax.” Such words are sometimes borrowed not because speakers lack a name for the object in question but in order to designate a special variety of the otherwise familiar artifact. Surely, the Finns had their own name for the ax but took over tappara, while the English appropriated a compound: a taper-æx was an ax of the kind taper.

A good collection. It all adds up.

A good collection. It all adds up.As mentioned above, I have my own suggestion; it concerns the etymology of adz. It will probably die in the mass grave of equally ingenious and equally hopeless hypotheses. Yet it seems to me that in Old English the word acusa “ax” existed, with d substituted for k under the influence of some continental form like Middle Low German dessele “adz.” If I am right, Old Engl. adusa is a blend. Francis A. Wood, at one time an ingenious, if not always reliable, etymologist at the University of Chicago, had a somewhat similar idea, but he reconstructed pre-Old Engl. a-dehsa, as in OHG dehsala (a southern cognate of dessele, mentioned above). I think my approach is a bit more realistic because it does without relying on the doubtful Old English form with the initial vowel a-. In any case, it is perhaps not entirely improbable that a German word of the same meaning influenced the form we have in English. German dehsala ~ dessele (their Modern English cognate is the little-known thixel) is a word of well-established etymology.

Our migration, ax ~ adz ~ hatchet ~ topor in hand, is over, indeed in the dark, but not entirely without a glimmer of light at the end of the tunnel.

Images: (1) “Stone axes” by Celeste Lindell, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr. (2) Angry man axe cartoon by Clker-Free-Vector-Images, Public Domain via Pixabay. (3) Axe by Sergey Klimkin, Public Domain via Pixabay. (4) Axe hatchet by Alberto Barrionuevo, Public Domain via Pixabay. (5) “Adz and Pick End of Halligan Tool” by Skipatrolkid, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (6) Hammer by Rudy and Peter Skitterians, Public Domain via Pixabay. Featured image: “Indo-European languages” by MapLoader, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post An ax(e) to grind appeared first on OUPblog.

Aging Cheddar: a timeline of the world-famous cheese

In the cheesemaking world, “Cheddar” is a generic term for cheeses that fall into a wide range of flavor, color, and texture. According to the US Code of Federal Regulations, any cheese with a moisture content of up to 39% and at least 50% fat in dry matter is legally considered a form of Cheddar. The varying processes involved in production have allowed regions around the world to create their own take on this globally consumed cheese. Based on research found in The Oxford Companion to Cheese, the timeline below marks key dates in the history of Cheddar.

Featured image credit: “Cheese!” by Roxanne Ready. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Aging Cheddar: a timeline of the world-famous cheese appeared first on OUPblog.

Academy schools and the transformation of the English education system

Increasing the quality and quantity of an individual’s education is seen by many as a panacea to many social ills: stagnating wages, increases in inequality, and declines in technological progress might be countered by policies aimed at increasing the skills of those who are in danger of falling behind in the modern labour market.

Whether or not education is the cure-all that its advocates suggest, it is widely acknowledged that there is a clear mismatch between the social and private returns to education. Economic theory suggests that on these grounds, education should be subsidised and indeed, in the vast majority of countries, the state plays a major role in funding the education system. What is less obvious is the extent to which the state should manage the system: should teachers be hired, and have their performance managed, by the state? Should the curriculum be set at a national level? Should schools have no say in how their admissions are managed?

In a bid to answer such questions, the United States and Sweden have both moved towards more decentralised school systems through the introduction of more autonomous schools that remain centrally funded; namely, charter schools and free schools. In England, an even more dramatic change has taken place.

Until recently all of England’s schools were to become, or be in the process of becoming, academies by 2022. While the government’s focus has shifted somewhat towards the expansion of grammar schools, it is still the case that academies are a focal point of the government’s education policy, with Education Secretary Justine Greening now encouraging, rather than compelling, schools to gain academy status.

Historically, education in England has been a centralised process: local educational authorities (LEAs) responsible for state education received funding from the central government, which they then distributed to schools under their control, typically according to school size. Community schools, which until recently made up the bulk of the state sector, have all of their staff employed by the LEA, and the LEA owns the school premises and determines the admission criteria.

In the early 2000s this changed when the Labour government began the academies programme that gave control of some secondary schools, which were perceived to be failing, to private sector ‘sponsors.’ These sponsored academies were state funded schools, but had little restrictions on how they spent their money; furthermore, the school’s governing body, which was appointed by the sponsor running the school, had much greater autonomy from local authority control than the governing bodies of other state-funded schools. By January 2010 there were 203 sponsored academies in existence, all of whom were free to exercise a large number of freedoms – these include hiring and firing of staff, being able to diverge from the national curriculum, set their own performance management system for their teachers, and outsource services previously provided by their LEA.

It is widely acknowledged that there is a clear mismatch between the social and private returns to education.

Using a quasi-experimental research design, we estimate the causal effect of attending one of 94 sponsored academies that opened prior to September 2008 on pupil performance. To account for the fact that schools that became sponsored academies were below the national average in terms of test score performance prior to conversion, we compare outcomes for pupils attending academies that converted between September 2003 and September 2008 with those attending schools that would later convert between September 2009 and September 2010. Looking at the characteristics of these two sets of schools before the start of the programme, we find that they are balanced in terms of test score performance and the demographic make-up of their students. As well as comparing outcomes of students who attend similar schools, we limit our analysis to pupils who were already enrolled in the schools before the schools gained academy status to avoid problems of non-random selection into academies.

Our results suggests that on average, a student attending a sponsored academy between 2002 and 2009, scored 0.10 of a standard deviation higher in their end of school (Key Stage 4 exams) than a comparable pupil attending a school that would later gain academy status. The results are more pronounced the longer a pupil spent in an academy: pupils who spent four years in an academy gained 0.3 standard deviations on their peers who attended similar schools. To give some indication of the size of these effects, the key stage 4 achievement gap between girls and boys is around 0.2 of a standard deviation; similarly, the gap between those who are eligible for free school meals and those who aren’t is approximately 0.75 of a standard deviation. In addition to short term gains, we also find positive effects of academy attendance on the probability of staying on in education, beyond what is compulsory, and entering a degree programme.

An important point is that the sample of schools that we study is a small fraction of the total number of secondary schools in England. Since 2010, the academies programme has expanded at a rapid rate with well over 60% of secondary schools having gained academy status. The extent of the decentralisation of a previously centralised education system is unprecedented amongst advanced economies. Not only has the pace of expansion been rapid, but it has also grown to cover a wide variety of schools: primary schools are also now being ‘academised’ and high performing schools, known as ‘converter’ academies, have been able to get greater freedoms without the need for a private sector sponsor. The bulk of these new academies are very different from the low performing schools converting prior to 2010; indeed, the growth of secondary academies has largely been due to ‘converters’, who, in their predecessor state, are drawn disproportionately from the high end of the performance distribution. This, combined with evidence from the US suggesting that autonomous schools primarily benefit disadvantaged schools in urban areas, limits the applicability of our findings to the new wave of academies.

Given the results highlighted above, it is natural to ask to whether full ‘academisation’ is a wise idea?

Currently we have no firm answer. While we have evidence of the effectiveness of academy conversion for disadvantaged schools in the secondary sector, there is little reason to think that this is applicable to either high performing schools in the same sector or schools serving younger pupils. Because any expansion of the programme will be concentrated in the primary sector, where there are relatively few academies operating, this latter point is a pertinent and important area for future research.

Featured image credit: Wood pencil education by Monoar. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Academy schools and the transformation of the English education system appeared first on OUPblog.

Nat Turner’s legacy

Nate Parker’s movie The Birth of a Nation, which opens in Europe this month, tells the semi-fictionalized story of Nat Turner, an enslaved man who led a short-lived rebellion in rural southeast Virginia in August 1831. The movie focuses on Turner’s life before the rebellion; demonstrating one man’s breaking point sparked by the witnessing of extraordinary brutality. In the movie version, Nat Turner was a baptist minister, hired out to plantation owners to preach sermons of obedience to the enslaved communities. The Birth of a Nation showcases the roots of Black revolutionary thought at a time when the Black Lives Matter movement is in full force. It also begs acknowledgement to the legacy of the rebellion as it relates to the eventual abolition of slavery. Taking the long view, was the rebellion successful? What questions does the film raise, and how can we use the film as a catalyst for honest reflection and progress?

The movie invites timeless questions such as why did most enslaved people obey their owners instead of rebelling? What legitimate options did slaves have given that they had no say in the laws holding them in brutal bondage? Was Turner a Freedom Fighter like those heroes of the American Revolution whom we venerate? What is the history and legacy of Black freedom fighting? Yet, we do not hear Turner say much about this. For the movie depicts the defeat of the Turner rebels and then–after some weeks in hiding–it has Turner surrendering and being executed. The movie leaves out what has come to be known as his Confessions and his trial. That is, Turner has an important legacy in the debate he sparked. That legacy of debates about the morality and expediency of slavery is not explored in the powerful movie.

Much of what we know about the rebellion and Nat Turner himself comes from the pamphlet called The Confessions of Nat Turner, which was published by a local lawyer, Thomas Gray. The Confessions purport to be a statement made by Turner to Gray, but for decades scholars have debated how much of it is Turner’s thoughts and how much Gray’s. The Confessions suggest that Turner was unrepentant and believed himself divinely inspired and justified. There are sections that sound unmistakably different from the main narrative, which leads many scholars to believe that Turner’s voice is indeed there–but edited–by Gray.

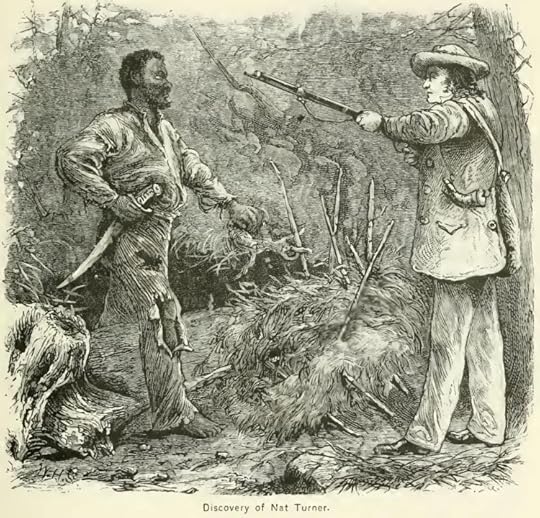

Discovery of Nat Turner: wood engraving illustrating Benjamin Phipps’s capture of w:Nat Turner (1800-1831) on October 30, 1831 by William Henry Shelton. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Discovery of Nat Turner: wood engraving illustrating Benjamin Phipps’s capture of w:Nat Turner (1800-1831) on October 30, 1831 by William Henry Shelton. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.There is another, longer story of the rebellion’s aftermath, too. For the rebellion inspired Quakers to petition the Virginia legislature to end slavery. Some legislators from western Virginia, where slaves were relatively few, took up the cause. They looked back to enlightenment ideas of freedom that circulated in Virginia during the days of the American Revolution and urged the adoption of a gradual abolition scheme. But the ideas that property and slavery were twin pillars of civilization, that Virginians could not afford to give up slavery, and that slavery was a key ligament of society were more popular.

After the debates ended Thomas Dew, a young William and Mary professor, summarized the arguments in a pamphlet called Review of the Debates in the Virginia Legislature. Dew’s pamphlet covered well the pro-slavery case, from the near ubiquity of slavery in history, to the impracticality of deporting freed slaves, to the centrality of slavery to the southern, indeed American, economy. Turner, thus inspired one of the most important pro-slavery treatises ever written. And Dew silently responded to other African Americans as well. Where David Walker’s Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World proclaimed that “we Coloured People of these United States, are, the most wretched, degraded, and abject set of beings that over lived since the world began,” Dew responded, without deigning to mention Walker, “A merrier being does not exist on the face of the globe than the negro slave of the United States.” Others built out Dew’s ideas. For instance, Georgia lawyer Thomas Cobb wrote An Inquiry into the Law of Negro Slavery in 1858, which contained pro-slavery arguments drawn from history, economics, and ethnography. But subsequent authors worked within the arguments Dew first used. They say a lot about why southerners would not give up slavery without a fight and a big one.

Though only a few dozen slaves participated in the rebellion and it was largely over in two days, the rebellion marked a turning in proslavery thought and set the nation on the road towards Civil War–and the extinction of slavery through that war. Black revolutionary thought is a long established ideology throughout the African Diaspora, and Turner’s rebellion is without question one of the pillars of this tradition.

Featured Image Credit: “Black chain” by lalesh aldarwish. Public Domain via Pexels.

The post Nat Turner’s legacy appeared first on OUPblog.

Preventing the next flight from Bethlehem

A part of the Christmas story tells how the Holy Family fled Bethlehem, warned in a dream of the vengeful plans of a mad monarch. In recent years, Christians have once again found cause to flee the town of his birth. The case study of Palestinian Christians is emblematic of the larger problems faced by Christian populations in the Middle East. Considering the dramatic and often horrific challenges faced by Christian Arabs in the Middle East, how can the small community of Christians survive and continue to maintain a foothold in the region?

Over the past two decades, the accelerating decline of Christian communities in the Middle East has become a growing crisis for Christians and for the future of pluralism in that part of the world. In 2010, the Vatican hosted a Special Assembly of the Synod of Bishops for the Middle East, reflecting Benedict XVI’s particular concern “to confirm and strengthen Christians in their identity” and to encourage them to renew their commitment to the region. In September 2014, a citizen-led initiative convened a conference of Middle Eastern and Western leaders in Washington, DC, aimed at mobilizing public policy in defense of Christians in the region. Palestinian Christians post enticements to their coreligionists to remain in the land. Nevertheless, the plight of Christians throughout the region has only grown increasingly dire, highlighted most dramatically in the genocidal acts of the so-called Islamic State driving the greater majority of Iraq’s remaining Christians into internal and external exile.

A focal point of the concern over Christian emigration is the small and dwindling community of Christians among the Palestinians living in the West Bank and Israel. Christians have remained in the Biblical Holy Land since the days of Jesus Christ himself. Their relative numbers have declined gradually over the centuries, a decline that accelerated significantly after the end of the colonial period and the wars that followed the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948. As the Oslo Peace Process fell apart amid the failure of the Camp David II negotiations in 2000 and the descent into the second intifada, Christians began to leave en masse. Today, the remnant lives clustered around the most important Christian holy sites in Nazareth, Jerusalem, and Bethlehem.

A continuing Christian presence in this region remains a high priority for many Christian groups. However, the politicization of the Arab Christian minority, caught between the reflexive pro-Israel perspective of many Western (and increasingly, many African and Asian) Christians and their own desire to speak truth to Israeli power, has made it next to impossible to find a unified political voice.

Tourists continue to flock to the Christian shrines in the Holy Land (as here at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre). But how long will there remain indigenous Christians to maintain them? Photo credit: Paul Rowe. Used with permission.

Tourists continue to flock to the Christian shrines in the Holy Land (as here at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre). But how long will there remain indigenous Christians to maintain them? Photo credit: Paul Rowe. Used with permission. Palestinian Christian communities in Israel face many of the same challenges as their Muslim counterparts. But for Christians these challenges are complicated by their status as a minority within a minority. Several years ago, a controversy over the proposed construction of a mosque in the area of the Church of the Annunciation in Nazareth pitted the Islamist movement against the Christians. More recently, the Israeli Defense Forces have actively sought to recruit soldiers among the Christian population, an effort that threatens to isolate Christians from their Muslim compatriots who wouldn’t volunteer to serve in the military. In Jerusalem, a large proportion of the Christian community faces the uncertainty of their status as residents without citizenship. These Palestinians must remain residents of the city or lose their ability to travel back and forth between Israel and the occupied territories.

In the West Bank and Gaza Strip, the plight of Christians is even more dramatic, as the economic and social oppression of living under occupation has made life very difficult. Gaza has only a very small population of Christians, marginalized by the Hamas-led administration and victimized by violent Israeli incursions. The ruin of the Palestinian economy in the West Bank disproportionately affects the more prosperous Christian community. The construction of the so-called security barrier has a direct impact on the small but vital Christian community of Bethlehem, where the barrier takes the form of an eight-metre high concrete wall that casts a shadow on numerous Christian homes and businesses. The limitation and reduction of international tourism that arose after the second intifada brings fewer foreigners to the shops, inns, and restaurants of Bethlehem. The isolation of the Palestinians within Areas A and B of the West Bank has led to internal migration of Muslim communities to the city, increasing the tensions between “native” Bethlehemites and other Palestinians.

Though the plight of Palestinian Christians is an international concern, the resilience of their community in the region must ultimately depend on their own survival strategies. Over the past decade, Palestinian Christians have met the challenge through a renaissance in civil activism and social concern for the community. In spite of the dramatic decline in the population, Christian civil society organizations (CSOs) are “punching above their weight.” They join a large community of other non-governmental organizations in filling in some of the gaps left by the dysfunctional Palestinian Authority. Nazareth’s Christians are central players in the continuation of civil society activism based in the city. Christian-led organizations in Bethlehem have spearheaded efforts to bring international tourism back to the city. In Jerusalem, Christians are building bridges with the Messianic Jewish community in an effort to bring seeds of reconciliation to a divided society.

The civil activism of the Palestinian Christian community forms a model for Christian survival throughout the Middle East. As a small minority, Arab Christians are typically unable to effect direct change through democratization. In both more and less democratic societies, their churches and parachurch organizations form the sanctuary of the Christian community, a sanctuary often opened wide to care for non-Christians as well. Civil initiatives have provided a feeling of efficacy and purpose, and so contribute to the survival of the Christian minority amid severe challenges.

Featured image credit: ‘Bethlehem’. Photo by geralt. CC0 Public Domain by Pixabay.

The post Preventing the next flight from Bethlehem appeared first on OUPblog.

December 13, 2016

The Cuban Revolution and resistance to the United States

The origins of the antagonism are not difficult to discern. The endurance of the antagonism, however, well–that is a bit more complicated.

The Cuban revolution came out of the very history that it was determined to redress, a history profoundly shaped by the United States and into which the Americans had deeply inscribed themselves with pretensions to preponderant power. For vast numbers of Cubans, the revolution was about a people determined to reintegrate themselves into their history as subjects and enact historical narratives as protagonists, to make good on a historic claim to national sovereignty–a claim possessed of a proper history, advanced first in the nineteenth century against Spain, and subsequently in the twentieth against the United States.

Fidel Castro transformed Cuban historical aspirations into a means of political mobilization, given to the proposition that the sources of Cuban discontent–social, economic, political–could be addressed only through the realization of sovereign nationhood: sovereignty not as an end but as a means, to establish the primacy of Cuban interests as the principal purpose to which public policy would be given.

But the affirmation of the primacy of Cuban interests could not but challenge the privileged American presence, for the structural responses around which the purpose of Cuban self-government had been conditioned since the founding of the republic in 1902 had incorporated as a matter of default deference the prerogative of US interests. Former ambassador Earl E. T. Smith was unabashed in his assertion that the United States “was so overwhelmingly influential in Cuba that […] the American Ambassador was the second most important man in Cuba; sometimes even more important than the President.”

The most visible exponent of Cuban historic aspirations was Fidel: defiant, strident, at times virulent denunciations, hours at a time, day after day, stretching into weeks and then months, with an unambiguous message, and an unequivocal moral: Cuba for Cubans. The genius of Fidel Castro was his ability to inscribe himself into the past and reemerge as its proponent, to propound a version of the history of Cuba-US relations familiar in Cuba but wholly unknown– indeed, incomprehensible–in the United States.

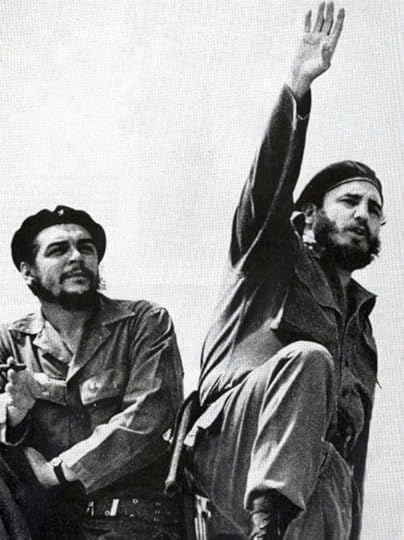

Revolutionaries Che Guevara and Fidel Castro in 1961. Photo: Alberto Korda from the Museo Che Guevara, Havana, Cuba. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Revolutionaries Che Guevara and Fidel Castro in 1961. Photo: Alberto Korda from the Museo Che Guevara, Havana, Cuba. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The incoherence with which the United States initially responded to the Cuban Revolution must be understood as a condition of cognitive dissonance: the inability of the Americans to order into coherent narrative form developments so profoundly counter-intuitive and utterly inconceivable as a Cuban challenge to US power. As the United States worked to fashion a usable narrative to make sense of Cuban developments, the Cubans proceeded with the nationalization of US property, beginning with the sugar corporations and cattle ranches, and expanding to oil refineries, utilities, mines, railroads, and banks. And when it was all over, everything–absolutely everything–previously owned by the Americans, all $1.5 billion of US property, had been nationalized.

But the worst was yet to come. If it is difficult to underestimate the incomprehension with which Americans viewed Cuban domestic policies, it is nearly impossible to overstate the horror with which they reacted to Cuban foreign policy, specifically the expanding ties with the Soviet Union.

And yes: the missiles…

Former Secretary of State Dean Rusk later wrote of the missiles as having “a devastating psychological impact on the American people.” That Cuba had provided the Soviet Union with entree into the “backyard” of the United States simultaneously stunned and sickened US officials. Fidel Castro had made the Americans feel vulnerable. “Castro’s Cuba formed an overhanging cloud of public shame and obsession,” former Under-Secretary of State George Ball bristled as late as 1992. “Many Americans felt outraged and vulnerable that a Communist outpost should exist so close to their country. Castro’s Soviet ties seemed an affront to our history.”

The United States directed its ire to the person of Fidel Castro, to attribute to the Cuban leader mischievous intent and malevolent purpose, to whom all evil doings would henceforth be attributed. Thus began the American obsession with Fidel Castro, whereupon the personal did indeed become the political. Fidel Castro traumatized the United States. He deeply offended American sensibilities. Castro would not be forgiven–ever. Fidel and the Cubans had to be punished and taught a lesson for the trauma to which they had subjected the United States. New York Times foreign affairs editor Thomas Friedman was entirely correct to suggest in 1999 that the US position on Cuba was “not really a policy. It’s an attitude–a blind hunger for revenge against Mr. Castro.” It was to this punitive purpose to which scores of assassination plots, years of covert operations, and decades of withering economic sanctions have been given. Not a few commentaries in the days following Castro’s death hinted at disappointment that Fidel died in his sleep, unrepentant and unpunished .

Featured Image Credit: Soviet poster depicting friendship between Cuba’s Fidel Castro and USSR’s Nikita Khrushchev. Photo by Keizers. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The Cuban Revolution and resistance to the United States appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers