Oxford University Press's Blog, page 430

December 11, 2016

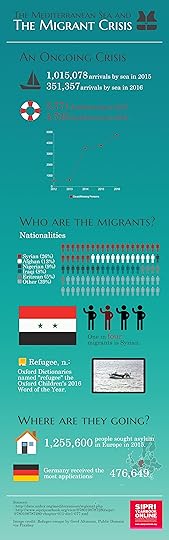

The Mediterranean Sea and the migrant crisis [infographic]

With the Oxford Place of the Year competition drawing to a close, we’ve put together an infographic to explain why the Mediterranean Sea, geographic epicenter of the migrant crisis, earned a place on the shortlist alongside Aleppo, the U.K., and Tristan da Cunha. Vote for the Mediterranean Sea or any of the other nominees in our Twitter poll.

Now is your chance to vote for the Oxford University Press Place of the Year for 2016 https://t.co/IqGhpMifyU

— Oxford Academic (@OUPAcademic) December 5, 2016

Download this infographic as a PDF or JPG.

Featured image credit: “Coastal Landscape” by Cocoparisienne. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The Mediterranean Sea and the migrant crisis [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

December 10, 2016

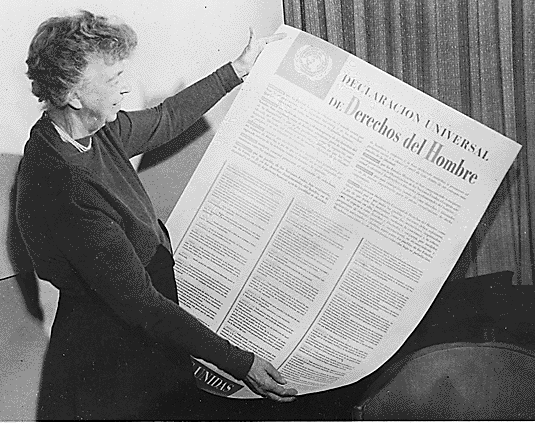

International Human Rights Day resources

December 10 is International Human Rights Day, as recognized by the United Nations. Human dignity, freedom from discrimination, civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights for all should go without question. Whether it be from “the Hindu Vedas; the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi; the Bible; the Quran (Koran); the Analects of Confucius; the codes of conduct of the Inca, Aztec, or the Iroquois Constitution, there is evidence that most societies had systems in place to care for the needs of their members.”

The necessity of human rights for all and the value of individual human life should be unquestionable. In recognition and respect for International Human Rights Day, we compiled together this list of recommended resources to encourage deeper reflection on the issues.

Human Needs: Overview by Michael A. Dover

Human need and related concepts such as basic needs have long been part of the implicit conceptual foundation for social work theory, practice, and research. Michael A. Dover examines how human need has long been both a neglected and contested concept. In recent years, the explicit use of human needs theory has begun to have a significant influence on the literature in social work.

Human Rights and US Foreign Policy by Sarah B. Snyder

In its formulation of foreign policy, the United States takes account of many priorities and factors, including national security concerns, economic interests, and alliance relationships. An additional factor with significance that has risen and fallen over time is human rights, or more specifically violations of human rights. Sarah B. Snyder analyzes the historical debate around the extent to which the United States should consider such abuses or seek to moderate them.

The Human Rights of Migrants and Refugees in European Law by Cathryn Costello

Focussing on access to territory and authorization of presence and residence for third-country nationals, The Human Rights of Migrants and Refugees in European Law examines the EU law on immigration and asylum, addressing related questions of security of residence. Concentrating on the key measures concerning both the rights of third-country nationals to enter and stay in the EU, and the EU’s construction of illegal immigration, it provides a detailed and critical discussion of EU and ECHR migration and refugee law.

Islamic Law and Human Rights by Shannon Dunn

Shannon Dunn explores the question of whether Islamic law and universal human rights are compatible. She begins with an overview of human rights discourse after the Second World War before discussing Islamic human rights declarations and the claims of Muslim apologists regarding human rights, along with challenges to Muslim apologetics in human rights discourse. She then considers the issues of gender and gender equality, feminism, and freedom of religion in relation to human rights.

“Eleanor Roosevelt and United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Spanish text.” Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Eleanor Roosevelt and United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Spanish text.” Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Are Refugee Rights Human Rights? An Unorthodox Questioning of the Relations between Refugee Law and Human Rights Law by Vincent Chetail

In this chapter, Vincent Chetail provides a critical assessment of the interactions between international refugee law and human rights law. Although refugee law and human rights law were initially conceived as two distinct branches of public international law, their multifaceted interaction is now well acknowledged in both state practice and the scholarly literature. However, the normative impact of their relationships has been rarely considered via a systemic perspective. Vincent Chetail explores the relations between refugee law and human rights law from a holistic and critical angle.

Bioethics and Basic Rights: Persons, Humans, and Boundaries of Life by Judit Sándor

Judit Sándor examines the connections between bioethics and basic rights partly by analyzing the basic legal norms of bioethics, and partly by comparing thematic cases from the jurisdictions of the European Court of Human Rights and the US Supreme Court, as well as some cases from other jurisdictions. She focuses on two major lines of thought in contemporary bioethics: the first is concerned with the boundaries of life (e.g., issues of embryo research, assisted reproduction, and end of life decisions) and the second is related to the contemporary exploration of the frontiers of the human body (issues such as the use of human tissues and human DNA for research and other purposes).

Human Rights and Social Work in Historical and Contemporary Perspectives by Obie Clayton and June Gary Hopps

At the heart of social work, human rights are a set of guiding principles that are interdependent and have implications for macro, mezzo, and micro policy, and practice. They can be best-understood vis-à-vis the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, increasingly referred to as customary international law; the covenants and declarations following it, such as the conventions on the Rights of the Child (CRC), Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD), and Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW); and reporting procedures, such as the filing of country reports on compliance. Obie Clayton and June Gary Hopps address how this powerful idea, which emerged from the ashes of World War II, emphasizes human dignity; non-discrimination; civil and political rights; economic, social, and cultural rights; and rights to solidarity. The challenge is the creation of a human rights culture, which is a “lived awareness” of these principles in one’s mind, heart, and body. Doing so will require vision, courage hope, humility, and everlasting love, as the spiritual sage Crazy Horse reminds us.

The Sovereignty of Human Rights by Cathryn Costello

The Sovereignty of Human Rights advances a legal theory of international human rights that defines their nature and purpose in relation to the structure and operation of international law. Professor Macklem argues that the mission of international human rights law is to mitigate adverse consequences produced by the international legal deployment of sovereignty to structure global politics into an international legal order. The book contrasts this legal conception of international human rights with moral conceptions that conceive of human rights as instruments that protect universal features of what it means to be a human being.

Featured Image Credit: “Palais des Nations (Geneve)” by Eferrante. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post International Human Rights Day resources appeared first on OUPblog.

“I am rushing”…a mantra of love and memory

Grief memory enters in such strange ways. I can see him and hear my late husband Gene saying, “I am rushing.”

At the time he said this, Gene was going through chemotherapy for metastatic prostate cancer which had been lying dormant for the prior 13 years, or perhaps better said, had been “in check” with his hormone therapy. This particular morning, he was seated at the kitchen table, a mere hour before a meeting he had. His head was bent low. He was quiet. He had eaten and was now sitting still, digesting maybe, thinking maybe, moving in his mind maybe. I wrote:

I can see Gene sitting at the table…..I am running around at a different pace, getting Eliana’s breakfast, lunch, taking her to carpool to get to school on time. When I return and sit across him with my coffee, it is almost 8:10 in the morning. I know he has to leave at 9 for a meeting.

“Don’t you have an appointment this morning?”

“Yes,” he answers, “I am rushing.” Silence. No movement.

It took me a very long time to understand what was going on for him. For such a long time, I have heard, “I am rushing” in my mind. He was rushing by trying to move at some recognizable speed that we do when we don’t have to pay attention to our health. He was rushing, in his head, but his body was not moving. I was all motion. I really was rushing.

Now, I am rushing at the internal speed that he had. Illness takes time away from you that life fills with its time that moves in a cycle of speed that takes up time. We are all rushing somewhere.

Rushing seems to be about speed. But is it?

Rushing seems to be about speed. But is it? There is the juxtaposition of what we see on the outside and what is going on in the inside, the movement over time of our understanding of another person’s experience, the various ways in which we grow into our own existential understanding, the ways in which we learn how we age into illness or into health, the ways in which we come to see how we move.

Is rushing about speed or is it about thought? Is it about our health or our loss? Is the experience coming at us or moving away from us? Are we going somewhere, and if so where are we going? And frankly, will it matter where and when we are going there? Will I ever be able to sit at my kitchen table and not be going in my mind or in my body where he was going? I must now question, do we feel the slow motion of time or speed or thought when we ourselves are in it? Is slow motion a form of consciousness or a rhythm of time?

I have just returned from spending time with a dear friend and her husband. They are living in what I have come to call “Illness Time” – not a period of time spent ill, but time itself defined by illness. He has Parkinson’s disease and has been living with it for the past seven years. Like Gene, he is not only a doctor now, but also a patient. Like Gene, he is very much still himself – a wonderful, kind, bright man. In his stillness, I can see both his fading and his ongoing presence. He can do everything he needs to do, just slower, safer, less rushed. And when or if he needs to rush, everything takes not only more time, but it seems to take a circuitous path as well. So rushing can’t only be about speed because it doesn’t move things any faster than his slow shuffle walks. Rushing is moving towards the goal, doing it somehow as to make it there, and thus, being there. Rushing is not time; rushing is the life force of Self, reminding us over and over again: I am here.

For Gene, getting up off the kitchen chair was no longer an unexamined physical move. Everything in his mind-body had to coordinate through the forces of will, effort and action, rushing as a plan of how to go about making such a move. Unconscious effort is a gift of health; in illness time, rushing is how we will ourselves into physical action.

“I am rushing” is a thought, a speed, and an action. For me, it has become a mantra of love and memory.

Featured image credit: Sunset by PublicDomainPictures. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post “I am rushing”…a mantra of love and memory appeared first on OUPblog.

Somewhere in an attic: the Emily Dickinson publishing dilemma

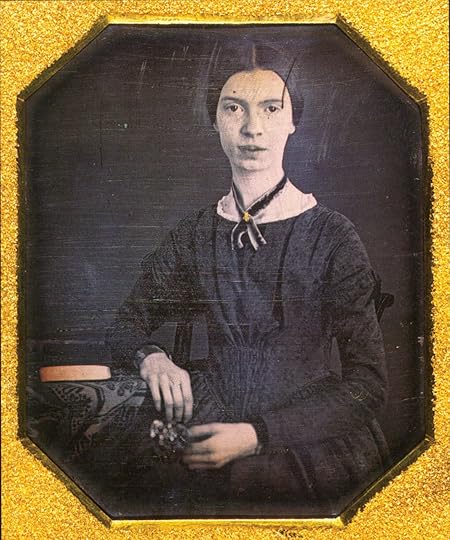

She’s been called “the myth of Amherst,” “the woman in white,” and a “recluse,” but the truth about Emily Dickinson and her writings is still being revealed, 130 years after her death. It’s an intriguing story of love, betrayal, and unlikely collaborations, and one that provokes several questions about the role that special collections and archives play in revealing important literary, historical, and biographical information to the public.

This story begins, rather oddly, at the end. Emily Dickinson’s death in 1886 marked the start of the generations-long debacle of publishing her wealth of poems. Emily’s sister, Lavinia Dickinson, was instructed to destroy Emily’s poems after her death, but decided to work on publishing them instead. She noticed Emily sent a large number of her poems—about 250—to her sister-in-law, Susan Dickinson, who was married to Emily and Lavinia’s brother, Austin Dickinson. Lavinia attempted to enlist Susan to help her in editing and publishing Emily’s poems. Susan shared no avid interest in the project, so Lavinia retrieved the poems and turned to an unexpected and controversial woman to aid her in this process: Mabel Loomis Todd, the woman with whom Austin Dickinson was having an extensive and very public affair. An even more salacious detail: Lavinia and Emily actually invited Mabel over to their home to meet Austin, some years prior, and Lavinia and Mable kept regular correspondence during her brother’s affair.

Emily Dickinson daguerreotype. Photo “emilydickinsondaguerreotype-high-res” by Michael Medeiros/Emily Dickinson Museum. Used with permission.

Emily Dickinson daguerreotype. Photo “emilydickinsondaguerreotype-high-res” by Michael Medeiros/Emily Dickinson Museum. Used with permission.Todd, unlike Susan Dickinson, was a “new woman in the late 19th, early 20th century: an intellectual, a writer, well-traveled, active in society, and very capable of getting something like this done,” explains Michael Kelly, Head of the Archives and Special Collections department at the Amherst College Library in Amherst, Massachusetts. She was willing and able to take on this project, but there was just one problem: she was the mistress of Emily Dickinson’s brother and was therefore not well liked by Susan and Susan’s descendants.

In 1890, Lavinia Dickinson and Todd enlisted the assistance of Thomas Wentworth Higginson, a major literary critic and champion of women’s writing at the time, to edit a volume of Emily Dickinson’s poems still in Todd’s possession. Together between 1890 and 1891, they published two volumes of Dickinson’s poetry, Poems of Emily Dickinson (1890) and Poems of Emily Dickinson, Second Series (1891) both of which sold well. They intended to publish more of her work, but when Austin Dickinson died in 1895, their plan disintegrated, as a feud between the Dickinson and Todd families erupted.

Austin Dickinson, to reward Todd for her editorial work in publishing his late sister’s poems, left her a plot of land in his will. Susan and Lavinia wanted the land instead, and the two women sued Todd for it, claiming that her lack of upstanding character should deny her the right to the property. In her rage, Todd took the poems she still possessed and locked them away.

“For more than thirty years she refused to raise the lid of her camphorwood chest filled with the Dickinson poems in her possession,” explains Michael Medeiros, the Public Relations Coordinator at the Emily Dickinson Museum in Amherst, Massachusetts.

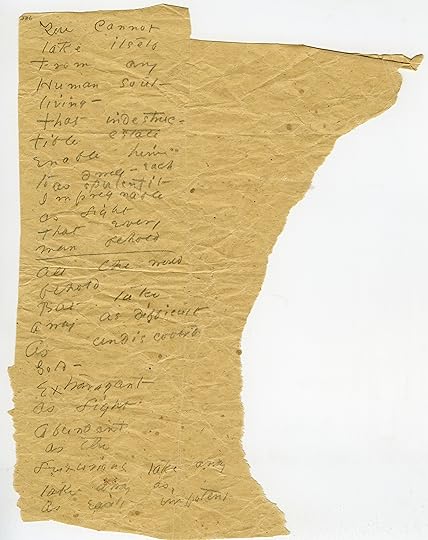

Eventually, the feud passed down to the younger generations of the Dickinson and Todd families, leaving Susan’s daughter Martha Dickinson Bianchi and Mabel’s daughter Millicent Todd Bingham to publish the remaining poems left in their respective collections. Martha donated her manuscripts to Harvard University in 1950, and Millicent relinquished hers to Amherst University in 1956, splitting the collection in two. A new exhibit at the Morgan Library and Museum in New York, running from 20 January 2017 until 21 May 2017 will showcase 100 rarely seen items, including manuscripts, letters, hand-cut silhouettes, photographs and daguerreotypes, and contemporary illustrations. Some of these items are entirely new to the public, suggesting that there may be more poems still to uncover, somewhere…

Photo of an Emily Dickinson poem, original manuscript. Photo “You cannot take itself” by Amherst College Digital Collections, courtesy of Michael Kelly. Used with permission.

Photo of an Emily Dickinson poem, original manuscript. Photo “You cannot take itself” by Amherst College Digital Collections, courtesy of Michael Kelly. Used with permission.“You don’t know what’s still sitting in somebody’s attic in New England,” says Michael Kelly. “The exhibit at Morgan will include things no one knew existed 10 years ago, and we are completely open to the fact that someone might turn up more Dickinson material, someday.”

The story keeps evolving, and Kelly stresses the important role of the Special Collections and Archive departments within libraries to continue to update and retell it. “Archives have to keep telling history over and over and over,” he remarks. “The more I get into it, the more fascinating it is.”

This story raises many questions for me, an insatiable reader and lover of literature, regarding the ethics of retaining literary content from the public eye, while also maintaining the right of the author or owner to keep possessions private. How could Mabel keep those poems for 30 years, locked away, unable to be read? Was she denying the public access to an entire literary collection, or simply exercising her right to keep her private property private? I spoke to Cynthia Harbeson, Head of Special Collections at The Jones Library in Amherst, Massachusetts about this dilemma from a librarian’s perspective.

“It’s not necessarily the role of the librarian to determine what materials survive,” Harbeson informs me, “but we do have a role in protecting and making available the materials in our care–and in advocating for records of cultural and historical value to be preserved. And what is considered to be of value changes over time.”

Technically, the Todd and Dickinson families had every legal right to keep Emily’s poems to themselves, forever. Thankfully, the families went in the other direction, but I still wonder: what if the Todd and Dickinson families never published Emily’s poetry, or if they destroyed all of it?

“Emily Dickinson actually wanted all her manuscripts destroyed after her death,” Kelly explains. “So many things survive only by chance—it’s madness, and that’s kind of the thing about it. We need to be defenders of people’s actual rights—they (the family members) had the right to keep them locked away forever.”

Despite Mabel Loomis Todd’s character and the Dickinson family’s sometimes questionable behavior, one could argue that the Dickinson and Todd families did the world of literature a great service by editing and publishing Emily Dickinson’s poems. Who knows, maybe there are still more out there, somewhere in an attic, waiting to be uncovered—or so I like to think.

Featured image credit: “emilycalendar45” photo by Michael Medeiros/Emily Dickinson Museum. Used with permission.

The post Somewhere in an attic: the Emily Dickinson publishing dilemma appeared first on OUPblog.

Does globalizing capitalism violate human rights?

Although philosophers have sought to claim that human rights is an idea that transcends time and place, critics have often noted that the history of the idea, from the Stoics to the present day, suggests processes of change associated with social and political revolution. For a growing body of critics, far from being a natural characteristic of humankind, all definitions of human rights are epochal.

In the present day, the human rights regime reflects individualism, the free market, private property, minimum government, and deregulation: the central characteristics of globalizing capitalism. Civil and political rights provide the foundational values for sustaining these characteristics. While the global human rights regime does include economic, social, and cultural rights, this set of rights are relegated to the status of aspirations, to be fulfilled once a country has achieved a sufficient level of economic development. To treat economic, social, and cultural rights on an equal basis as civil and political rights, challenges the liberal idea of the individual, who must be freed from all barriers to wealth creation. Poverty, hunger, and social disintegration may be a consequence of economic globalization, but those exercising their liberal, free market rights cannot be held responsible.

According to many critics, while the development of international law and institutions for human rights offer protection for the full range of human rights, globalization provides a socioeconomic context in which the protection of these rights is no more secure than in the past. This is because globalization structures the transfer of wealth from the poor to the rich, exacerbating existing inequalities within and between states, rewarding capital at the expense of labour, and creating far more losers than winners. It is commonly assumed that state leaders are responsible for gross violations of human rights. However, today the actions of transnational corporations, financial institutions, and international organizations, operating within the accepted boundaries of international law, are implicated. The cause of poverty and hunger are found in these structures of globalized capitalism.

Consequently, the economic dimensions of globalization are built upon a new orthodoxy that exalts production, finance, and trade above all else, including the protection of human rights. The spread, depth, and strength of the new ethos masks the cause of human rights violations, which is found primarily in economic restructuring, trade, and financial liberalization. Existing international institutions were created to promote and legitimate the positive advantages of economic globalization, but give little attention to the negative effects these actions bring. For example, the founding instruments of the World Trade Organization (WTO) make only oblique reference to human rights. Noting this, a report by the UN Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights argued that the rules of the WTO are not just unfair, but prejudiced against the poor, who have no voice or bargaining power.

In the age of globalization, the popularity of the idea of human rights has not been matched by a commitment to act

Accordingly, the measures pursued by the WTO, and other organizations central to the global economy, such as the World Bank and the IMF, undermine the efforts of global human rights institutions, international human rights law, and the work of progressive advocates of socioeconomic rights. It is also why the relationship between trade liberalization and human rights is frequently overlooked. On the rare occasions when the linkage is made to civil and political rights, the interests of global markets prevail.

To minimize the danger of the destabilizing revolution fermenting within, what Robert Cox has referred to as ‘superfluous workers’, the institutions of global governance have formulated a twin track policy: poor relief and riot control. The first of these takes the form of humanitarian intervention, providing food, shelter, and health care where mass poverty would disrupt the move towards integration within the global economy. Should this fail to quell the danger of social unrest, the riot control track is activated in the form of police and military action, both national and international. Much of the work of the United Nations and many nongovernmental organizations is devoted to one or both of these tracks.

Poverty, hunger, overpopulation, pandemics, child labour, terrorism, and urban violence are just some of the threats for which the troublesome superfluous are stigmatized. For those who enjoy a comfortable life of full employment, the unfortunate consequences of the modernizing world order must not be allowed to stand in the way of progress. Although toleration is promoted as a central principle of liberalism, it has its limits. Exercising civil and political rights to protest against liberalism itself, goes beyond that limit.

Some might see the argument that poverty, hunger, and the violation of human rights can only be understood within the context of the global economic order as a fringe view. However, a 2008 Amnesty International report accepts that while legal and organizational developments at the international, regional, and local level provide some evidence to support those who claim progress in protecting human rights, inequality, injustice, and impunity remain the hallmarks of today’s world order. While national and international leaders continue with their rhetoric, and rarely hesitate to put their names to declarations and international law on human rights, narrower political and economic interests continue to dominant global agendas. In the age of globalization, Amnesty argues, the popularity of the idea of human rights has not been matched by a commitment to act. In short, the Universal Declaration remains an unfulfilled promise.

Featured image credit: Human Rights Day – chalking of the steps by University of Essex. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Does globalizing capitalism violate human rights? appeared first on OUPblog.

Human rights under siege

Every year on 10 December, the international community comes together to honour Human Rights Day and commemorate when the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted in 1948. Reaffirming its commitment to the realisation of basic human rights, this year the United Nations are calling on everyone to stand up for someone else’s rights.

International human rights law has come to face compound challenges in the recent two decades. Long gone the optimism that followed the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action of 1993 which confirmed that the major changes in the international political scene at the time, and the aspirations of all the peoples around the world were finally moving in the same direction. Since then, political support for human rights globally has suffered a significant decline. Sovereignty–as a catch all phrase to assert supremacy of preferences of domestic governments–is back in fashion undermining the very premise of international human rights law: to collectively set and standards to ensure that the sovereignty is exercised for the protection and promotion of human rights of all.

Current scholarship identifies a key trigger of the declining political support for human rights as the rise of a newly populist politics in particular in Europe and the US, which vilifies human rights as an elitist and anti-democratic discourse, acting as the enemy of underdog masses. Many populist political movements around the world are in open retreat from upholding human rights obligations as specified by international human rights law of the last five decades. Significantly, the rise of anti-human rights populist politics unites a heterogeneous terrain bringing weak democratic regimes and authoritarian states together with constitutional democratic regimes of the West under pro-sovereignty, giving power back to people arguments. This has significant repercussions across the world as it revives the nihilist argument there can be no legal and universal core content to human rights.

Many populist political movements around the world are in open retreat from upholding human rights obligations

The reappearance of sovereignty as the primary reference for the interpretation, application and recognition of (domestic) human rights rings important alarm bells both for well-established norms of human rights law, for example, that of the right to life, the prohibition against torture, inhuman and degrading treatment, protection of freedom of expression, and for the future development of international human rights law standards in pursuit of protection of the most vulnerable in the light constantly changing social, political and economic conditions.

The negative effects of the declining support for human rights law and the anti-human rights rhetoric that accompanies it have already started to show its devastating effects on the most vulnerable groups. Asylum seekers, refugees and minority groups, in particular, have taken heavy hits. The failure of the European Union to distribute the burdens of incoming asylum seekers to Europe, in particular from Syria, has led to a paralysis of European refugee protection regime and threatens to undermine respect for principle of non-refoulement. Vulnerable minority groups, be they incoming asylum seekers or migrant religious communities have been vilified by populist politics undermining the recognition and respect for identities as the foundation of the principle of equality as developed under international human rights law.

The development of human rights law standards, for example, pertaining to specification of the rights of individuals who are caught up in conflict, are also bound to be effected by the decline of overall political support to human rights law. The fine-tuning of the application of human rights law in situations of conflict foremost requires an overall commitment to the relevance of human rights law, when military necessity and security concerns are heightened.

Scholars of international human rights law have time and again showed that the law of human rights is capable of taking into account the diversity of national and contextual circumstances

The political support for human rights, as grim as it may look, however, does not mean that the very purpose for the existence of international human rights law is mute. International human rights law is foremost a project based on the premise that there is a significant value in collectively identifying legal and universally applicable fine-grained human rights standards and holding all states into account based on these standards. Scholars of international human rights law have time and again showed that the law of human rights is capable of taking into account the diversity of national and contextual circumstances, whilst holding on to the universalist ideal that informs this collective enterprise. In the last fifty years or so, with trial and error as well as comparative learning, we have created an identifiable corpus of international human rights law standards that does not only exist in academic books, but that also flourishes in court rooms and public imagination and on the streets. Whilst political support for human rights is in retreat in the name of populist politics, international human rights law will remain a central normative and legal source for challenging the retreat of that support.

Featured image credit: ‘Roosevelt’s “Four Freedoms'”, by David. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Human rights under siege appeared first on OUPblog.

The Who’s Who of diplomacy and human rights

Today is Human Rights Day. This holiday commemorates when the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. In 1950, the Assembly passed resolution 423 (V), which invited all States and interested organizations to observe 10 December of each year as Human Rights Day.

Image by Ariana Milligan for OUP.

Image by Ariana Milligan for OUP.There are countless individuals who’ve dedicated their lives to improving international affairs and a call for human rights for all people. Including information from the 2017 edition of Who’s Who, we’re examining the movers, shakers, dreamers, and policy makers striving to create effective governance structures, equality, and a better world for individuals of all origins, nationalities, and identities. Celebrate human rights by reading more about the most recent additions to Who’s Who UK, updated on 7 December 2016 with diplomats, advocates, policy-makers, and world changers:

Mary “Mo” Flynn: Chief Executive, Rehab Group, since 2015

Mary Flynn currently serves at the Chief Executive of Ireland’s Rehab Group. She began her career in 1982 as a social worker in Ireland. From that first job, she moved throughout different job titles in social services, hospice, and other social aspects of health. Mary Flynn’s dedication to improving social conditions speaks to the heart of Human Rights Day, as her work has and continues to make strides in improving the health and wellbeing of countless individuals.

Joanne “Jo” Adamson: Deputy Head of EU Delegation to the United Nations in New York since 2016

Jo Adamson’s educational prowess is evident in her time at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, University of Oxford’s Saïd Business School, and Girton College, Cambridge. Ambassador Adamson has served as UK Ambassador to Mali (2014-2016) and non-resident Ambassador to Niger (2015-2016). Her diplomatic work has included striving to lessen water-related tensions and conflict in order to manage effects of climate change, population growth and economic development on individuals and the environment. She began her career as a social worker and this tone is reflected in the work she has devoted her life to since 1981.

Image created by Ariana Milligan for OUP.

Image created by Ariana Milligan for OUP. Kathryn Stone: Cheif Legal Ombudsman

Kathryn Stone was recently appointed Chief Ombudsman for the Legal Ombudsman. Before this position, Kathryn dedicated time to being theCommissionerr for Victims and Survivors in Northern Ireland. Additionally, Kathryn spent 11 years as Chief Executive of Voice UK, a national charity supporting people with learning disabilities and vulnerable people within the criminal justice system.

Dr. Carole Mary Crofts: Ambassador to the Republic of Azerbaijan since 2016

Dr. Carole Crofts has worked in the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office and within the realm of international affairs since 1987. Her career has spanned work in policy making and government. She previously held titles such as Second Secretary in Bonn & East Berlin to UK Trade & Investment’s Director for Energy, Transport & Construction. Most recently, Dr. Crofts was appointed Ambassador to Azerbaijan.

Featured image credit: Unisphere, May 25, 2009, Public Domain image via Flickr.

The post The Who’s Who of diplomacy and human rights appeared first on OUPblog.

December 9, 2016

Ten tips on how to succeed as a woman: lessons from the past

An unexpected figure lurks in the pages of Wonder Woman (no. 48) from 1951 — the 17th century French Classicist Anne Dacier. She’s there as part of the “Wonder Women of History” feature which promoted historical figures as positive role models for its readership. Her inspirational story tells of her success in overcoming gender prejudice to become a respected translator of Classical texts. Three hundred years after the publication of Dacier’s final translation, Homer’s Odyssey (1716), we too can learn from this figure. Looking back across her career, I can reveal ten tips for women today.

1. Be proactive

The keystone to Dacier’s success was the level of education she gained from her father, the scholar Tanneguy Le Fèvre. She was apparently proactive about securing this opportunity, secretly listening to her brother’s lessons and one day revealing how much she had learnt. This prompted her father to offer her the same education as her brothers.

2. Take risks

After Dacier’s father died unexpectedly, she made the bold decision to travel the 200-mile journey from Saumur to Paris and try to establish a career there. Later in her career, she took another risk when she translated the vulgar comedy of Aristophanes which was completely out of fashion. This daring undertaking is now recognized as a major part of her legacy to Classics.

3. Learn from mistakes

In two letters from 1681, Dacier begs her father’s friend, Daniel Huet, to intervene for her at Court so that she would get paid for the work which they had commissioned, as otherwise she was going to be left out of pocket. In fact, she never managed to resolve this issue, and in another letter, from later in that year, she notes that in future she would be more cautious! We all make mistakes, but it’s learning from them which can be our making.

Anne Le Fèvre, épouse Dacier by Pierre Bonnefont. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Anne Le Fèvre, épouse Dacier by Pierre Bonnefont. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.4. Find your voice

Dacier was working in the shadow of her father who had been a famous scholar, but this didn’t stop her from carving her own path. In part she managed to do this by making her own voice heard — by respectfully disagreeing with some of his views in print. She was also ready to challenge other male scholars of her day, demonstrating that she was equal to them.

5. Make female solidarity work for you

Women were the cultural arbiters of Dacier’s day and could confirm the success of a publication, Dacier therefore wooed the female readership in her first French translation. In the preface, she says she hopes that her translation will delight women (and of course it’s no coincidence that one of her chosen authors to translate was Sappho the famous ancient Greek female poet).

6. Transgress smart

Achieving your goals despite society’s gender boundaries can mean playing the boundary — enforcers at their own game. Dacier offers a textbook example of this when she negotiates her transgression into the exclusively male domain of the King’s Library to consult a manuscript. She gets away with her invasion into male territory by describing her reluctance and timidity in going there. This reassuring assertion of modesty allays any alarm felt at the incursion.

7. Network

A swift perusal of Dacier’s book dedications shows a skilled operator at work. These are not sentimental choices of parents and partners, but rather key figures whose support Dacier needed. She ensures that she’s noticed by the right people through these dedications. They are the equivalent of modern networking.

8. Pick a supportive partner

One of the mistakes which Dacier learnt from was her first marriage (to a printer, Jean Lesnier, in the Loire region). The marriage broke down after the death of their first child. Her second marriage, however, was to last until her own death. Her second husband André Dacier had studied with her father and was also a scholar. He respected her intelligence, collaborating with her on some publications, and supported her career.

9. Work-life balance

It seems impossible, from the stack of publications which Dacier produced, to believe that she could have also managed to have a life outside her books, but that’s exactly what the evidence suggests. Her contemporaries write that she was a wonderful conversationalist and praise her ability to socialise, setting the books aside to talk about hairstyles. Meanwhile her devotion to her family life is vividly recorded through her heartfelt words of grief after the death of her daughter.

10. Attract trumpet blowers

Self-publicity is a treacherous enterprise (and perhaps even more so now than in Dacier’s day). The elegant solution to the trumpet-blowing dilemma is to find someone else to do it for you. Dacier’s friend, who also happened to be a champion of women, Gilles Ménage did that brilliantly for her in his History of Women Philosophers.

The 21st century can seem a world apart from the 17th century: we’ve made significant gender progress over the intervening centuries. Yet gender inequality continues to be an issue. Looking back to the success of Dacier, and other historical female figures, at overcoming barriers is not only uplifting, but can also prove surprisingly instructive. It seems that we need our “Wonder Women of History” as much in 2016 as they did in 1951.

Featured image credit: Minerva and the Nine Muses. Painting by Hendrick van Balen the Elder. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Ten tips on how to succeed as a woman: lessons from the past appeared first on OUPblog.

Helping surgeons save lives and limbs

Surgeons have been facing an ever increasing crisis in finding a suitable material that can replace failing organs and blocked vessels safely and effectively. The worldwide shortage of organs causes almost 30% of patients who need replacement organs to die on the waiting list. Certain procedures such as bypass surgery and certain types of large incisional hernia repairs have a high success rate when performed using natural material such as the patient’s own veins. However, where this option is unavailable (due to already diseased veins for example), the success rate drops significantly as a plastic material is used instead. Pooled weighted data for primary patency rates for femoro-distal bypass are reported as 85%, 80%, and 70% for femoro-distal bypass with vein and 70%, 35%, and 25% for femoro-distal bypass with prosthetic material at one, three, and five years respectively.

Human xenotransplantation, the transplantation of partial or complete living tissues/organs from non-human species to humans, offers a potential alternative to plastic material for failed organs and blocked vessels in humans, while also raising many novel medical, legal, and ethical issues. A more advanced methodology of using xenografts is the creation of acellular scaffolding material from animal tissue that avoids the immune rejection while maintaining the strength and original natural structure of the living body. XenMatrix™ Grafts, for example, are created using a process which effectively removes cells from porcine (pig) collagen while maintaining the structure and strength of the graft. The resulting open collagen scaffold allows early cellular infiltration and revascularization without a significant loss of strength during the early healing process.

The worldwide shortage of organs causes almost 30% of patients who need replacement organs to die on the waiting list.

Omniflow II biosynthetic vascular graft, on the other hand, is a composite of cross-linked ovine (sheep) collagen with a polyester fine plastic mesh endoskeleton. The polyester mesh provides strength and durability, with resistance to aneurysm formation, while the collagen is stabilized, non-antigenic, and remains structurally intact for years after implantation. The wall revascularization improves resistance to infection.

Finally, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved earlier this year a new indication for the Integra Omnigraft Dermal Regeneration Matrix to treat diabetic foot ulcers. The matrix, which is made of silicone, cow collagen, and shark cartilage, is placed over the ulcer and provides an environment for new skin and tissue to regenerate and heal the wound.

In our centre, the Ashford and St Peter’s Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, the vascular surgeons have been using the above mentioned technologies on selected patients where all other alternatives have been deemed inappropriate by the multidisciplinary team. We have used XenMatrix™ Grafts recently on a large incisional hernia repair where the bowel was exposed under the skin, making the use of plastic material too dangerous and risking bowel erosion with subsequent contamination. The patient did very well and has regained her quality of life successfully. We have also used Omniflow II biosynthetic vascular graft in many other patients where the risk of infection was substantive and the options for using veins were limited. Those patients recovered well and regained excellent blood flow to their legs. Finally, the Surrey Tissue Viability Board will be soon considering Dermal Regeneration Matrix obtained from fish skin to treat difficult to heal wounds in selected cases where all other methods have failed to achieve acceptable level of wound healing.

We strongly believe that the technology of xenografts is here to stay, and is certainly the way forward if we are to win the continuous battle against resistant infection, shortage of organs, and increasing need for creative but naturally-driven solutions in disease management.

Featured image credit: Surgery by sasint. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Helping surgeons save lives and limbs appeared first on OUPblog.

Oral History Annual Meeting: an enriching experience

Before we give up on 2016, we’re taking one last look back at one of our favorite events from the year – the OHA Annual Meeting. We’ve already talked about why oral historians love the connections they make at the Annual Meeting, and how it serves as a yearly dose of sanity. Today we bring you some final reflections from Mark Garcia, who served as our local guide during the meeting and managed social media throughout the conference. Enjoy his summary, and make sure to get your proposal for #OHA2017 in soon. The conference, entitled “Engaging Audiences: Oral History and the Public” will be held in Minneapolis, and the deadline for submissions is 31 January. We look forward to seeing you there.

This past October the Oral History Association conducted the Fiftieth Annual Meeting in Long Beach, California. The theme of the annual meeting was OHA@50: Traditions, Transitions and Technologies from the Field. Many of my fellow classmates and I attended the Annual Meeting. I had a unique role as the Oral History Review Editorial Assistant roaming the floor, attending panel discussions, providing updates via the Oral History Reviews social media accounts, and writing on the Oxford University Press’s blog about local Long Beach insights for the Annual Meeting. In addition, I attended the Oral History Review editorial meeting and took meeting notes. The meeting was an enriching experience as I was able to sit among the editorial staff while they strategized on topics for future issues, book and peer review updates, article submissions, and upcoming projects.

The heart of the Annual Meeting was the many panel discussions. One of the of panels I attended was Centennial Voices: Using Oral history to Document Traditions and Guide Transitions where National Park Service Staff Historian Lu Ann Jones discussed the various Oral History projects of the National Park Service. Another powerful panel was Activist Women Within: Re-thinking Red, Yellow, Brown and Black Power through Oral History. Special guest and commentator of the Warrior Women’s Film Project Madonna Thunder Hawk provided oral history accounts of the Standing Rock protest in North Dakota. Our very own Dr. Natalie Fousekis, Director of the Center for Oral and Public History, was a speaker for the Oral History, Now (and Tomorrow) plenary session. Dr. Fousekis provided insights on the current status of oral history, plus ideas, opinions, and discussion for future oral history projects. These are just a few highlights of the many engaging panels from fellow oral historians.

This enriching experience provided me affirmation on why I am studying to be an oral historian. It was exciting to hear and discuss many of the same practice’s I have learned at Cal State Fullerton and beneficial too learn new innovative ways to conduct oral histories. For more insight on the Oral History Association Annual Meeting listen to Outspoken: A COPH Podcast Episode Five and hear from other conference participant’s experiences.

Let us know what you loved about #OHA2016, or what you’re looking forward to about #OHA2017 in the comments below or on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, or Google+.

Featured image courtesy of the Oral History Association.

The post Oral History Annual Meeting: an enriching experience appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers