Oxford University Press's Blog, page 434

December 2, 2016

Can dancing help with mental illness?

In 2015 the Alchemy Project delivered a pioneering ‘treatment’ for mental illness. It was modelled on contemporary dance training and was a different way of engaging with people and supporting their recovery. It was based on the work of Dance United and its proven, award-winning methodology. The premise was ambitious: that in just four weeks, participants would go from a place of no experience to a high-end artistic professional dance performance. There was daily practice working towards the performance in front of an audience of a 20-minute choreographed piece, ‘El Camino’ (‘The Way’ in Spanish). The mission was for dance to be a catalyst for radical change, helping to realise the potential of individuals. The teaching methodology is all about engaging and inspiring people struggling in their lives and it is innovative, holistic, and focuses on wellbeing rather than deficits.

There’s an idea that this kind of intervention is taking away from the traditional medical model. As doctors and psychiatrists, that is what we’re used to; we work in clinics, see patients, diagnose illnesses, and prescribe and treat with medication. Yes, there is psychotherapy, but treatment is predominantly about medication. But you can bring the arts into health, and it shouldn’t just be an add-on. It can be an integral part of what we do, and I absolutely believe that we should be prescribing projects like this.

In a way, the project was about moving away from diagnoses. No patient in the project was labelled, no one knew each other’s diagnosis or background, and in fact, I didn’t know the patients in the project. For me, as a doctor, it was incredible to be in a space where patients were just people and, more than that, they were dancers.

Reproduced and used by permission from Dance United. Copyright © 2015 Dance United.

Reproduced and used by permission from Dance United. Copyright © 2015 Dance United.What were the challenges?

When we started in 2013 there hadn’t been a contemporary dance intervention in the NHS service before, this was totally new territory. We were asking that people were referred intensively, on a full time basis, for four weeks. As you can imagine it was a very different way of working, not only for clients but also for the service. While developing the pilot, ‘Seabreeze’, so many questions arose: would clients turn up? Would they be able to engage intensively? Would they cope with an intervention like this? Would it be too stressful to perform on stage? Would it be possible to recruit young adults? Would they stay for the duration of the project?

What problems did it address?

Three key problems were identified, that conventional treatments were having a limited impact on.

Patients felt isolated and they struggled with interpersonal relationships.

Patients struggled with their body awareness and physical fitness, and this has a negative impact on overall levels of confidence.

Patients found it hard to get up in the morning, and maintain energy and optimism, and often over-focused on their condition.

From our experience, we knew that dance could have a big impact on these issues. Building evidence for this was crucial, and so we started to develop a theory of change right from the beginning.

During the project, participants were learning what it means to be in physical contact with people. When you have a mental illness, life can be very isolating. This is particularly so for people with psychosis, who may be hearing voices, be very confused, and paranoid about the world around them. It was a massive step for the young people to take. They were finding out what it means to be on a stage, in front of other people and in front of an audience.

What were the results?

Sixteen individuals were recruited and completed the pilot, and we started to find answers to our questions.

Reproduced and used by permission from Dance United. Copyright © 2015 Dance United.

Reproduced and used by permission from Dance United. Copyright © 2015 Dance United.They were able to engage and work intensively. They turned up every day and committed to it. They particularly flourished being called a ‘dancer’ and working together as a dance company, towards a shared goal. We saw clinically significant results in their wellbeing.

After the pilot we knew we needed to test the project further. The Alchemy Project has proved that it can be repeated, and last year there were two further interventions. We have been testing the impact of the methodology and building the evidence base, so we can support offering similar interventions in the future.

Participant’s wellbeing improved undoubtedly, but we also have the numbers to back it up. The Warwick-Edinburgh scale is used to measure mental health. As context, interventions in the NHS settings were seeing +1.2 points improvements. The pilot study saw an increase of 6.7 points, so very significant numbers, and in the Alchemy Project it was up 7.9 points.

We also looked at other measures – resilience, ability to trust others, concentration and focus. For me, the project is amazing because it taps into and improves all of these skills. It isn’t just about a four week project, and then ‘brilliant you’ve improved, and now we’re going to leave you’. The project had another arm which continued, and the participants went on to attend a dance college, they continued to meet each week, and did another performance.

What does this mean more broadly for arts and health?

We’ve built the evidence base. The big questions now are how do we do future projects and how do we break that commissioning barrier? But we hope the Alchemy Project doesn’t stop here.

Featured image credit: Reproduced and used by permission from Dance United. Copyright © 2015 Dance United.

The post Can dancing help with mental illness? appeared first on OUPblog.

The language of Christmas [quiz]

Christmas carols–a celebratory tradition spanning language and culture–were originally derived from the songs sung during the Winter Solstice. Christian lyrics were set to the tune of popular pagan carols, giving way to the festive music still played today. Take the quiz below to see if you can recognize the English translations of Christmas carols from around the world.

Featured image credit: “Santa Claus” by PublicDomainPictures. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The language of Christmas [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

To be a refugee in one’s own country

If there is a figure that has truly come to define the human condition over the last few years, it is the refugee. From the battlefields of Syria, to the water crossings from North Africa to Europe and the boats of Rohingyas escaping the Myanmarese state, to camps in Calais or Nauru, the refugee is not far from our sight. To claim the refugee as the figure of the 21st century is to forget that Hannah Arendt made a similar claim about the modern world, writing in the aftermath of the Second World War and decolonisation, and the flows of displaced people in Europe and Asia.

In popular and legal imaginations, the refugee is someone who has crossed an international border and had to flee the nation-state of their origin due to persecution and fear of threat to life. They become stateless as they are caught between their home lands and states, and other places they flee too. And as the news reports about Syrian refugees making their way desperately to Europe show, they are feared by receiving states and populations. To be a refugee is to be truly neither here nor there.

But does the refugee category capture the full experience of displacement? Since 1990 the valley of Kashmir has been marked by a conflict between an insurgency and a movement demanding the right of self-determination from the Indian state. Consequently life in Jammu and Kashmir has been marked by an extreme militarisation of the landscape, the violation of human rights, the loss of life, curfews, and strikes. However, amidst the different casualties of this conflict are the Hindu Minority of the Kashmir valley, better known as the Kashmiri Pandits. Between 1989 to 1991, an overwhelming majority of the community had fled to areas in southern Jammu and Kashmir and different Indian cities. The Pandit exodus remains controversial. Some argue that the Indian Government initiated the exodus to discredit the movement for Azaadi in Kashmir. Others insist that the Pandits were targeted as a Hindu minority and were supportive of the Indian state in Kashmir. The truth of the exodus is yet to be established.

Do the Pandits qualify as refugees? Many of them remain within India and even within their home state of Jammu and Kashmir. A prominent section of the population had been accommodated in camp colonies and townships, and have slowly rebuilt their lives over the years. While some return to visit Kashmir from time to time, barely have any Pandits returned to resettle in Kashmir.

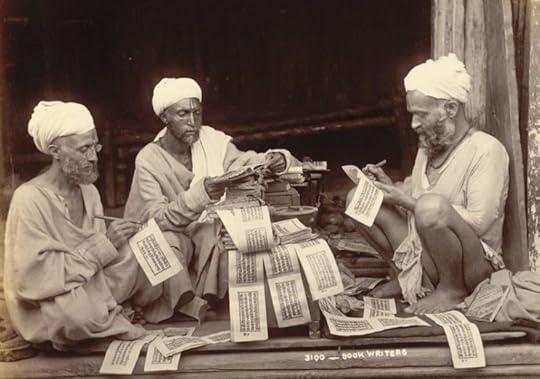

Three Hindu priests writing religious texts in the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir by Fowler&fowler. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Three Hindu priests writing religious texts in the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir by Fowler&fowler. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.But if we look at areas marked by conflict, past and ongoing, across the world, the phenomenon of Internal Displacement is far from uncommon. In conflicts such as the Sri Lankan Civil War, to South Sudan and Iraq, there have not only been flows of refugees but also large populations of people who have lost their homes, but remain within or close to conflict zones or within their own states. While the refugee is a legally recognised identity with rights and entitlements on paper, the Internally Displaced Person (IDP) is only a working definition. In some cases IDPs often have to look to the same state authorities whose policies and actions may have displaced them in the first place. Most IDPs also find themselves in the company of peoples displaced from their homes due to natural disasters, or large masses of migrants who travel to escape poverty. This contributes to the imagination of IDPs as an unclear mass of people, seemingly unrecognisable.

The Kashmiri Pandits especially face this problem. They are internally displaced and cannot claim refugee status. In turn the Indian state labels them as ‘migrants’, which is used to refer to all displaced persons in Indian administered Jammu and Kashmir. While the Pandits have been beneficiaries of a relief programme which provides limited financial and food aid, shelter in special camps and colonies for some, they remain uncomfortable with the label migrant. I was often told during my fieldwork in a migrant/Pandit camp in Jammu; ‘anyone is a migrant. You are a migrant!’ Hence the Pandits are acutely aware of a lack of recognition of their experience. The relief programme also locates them in a difficult position in relation to local communities. While there is sympathy for Pandits as a displaced people and as beneficiaries of relief, they are also seen to be privileged by the Indian state at the expense of other socio-economically and politically marginalised people in the region.

The Pandits share many of the problems faced by refugees. They have lost their homes, lives, and livelihoods. They express nostalgia for the lives they left behind in Kashmir and worry for an uncertain future in Jammu and Kashmir, in India and elsewhere. They are also dependent on the support of the state which offers very few solutions of any final form of resettlement or rehabilitation. In the early days of their displacement, many locals helped the Pandits while others were resentful and fearful of the arrival of potential squatters in their territories. However, the Pandits are fellow citizens and subjects. Like other IDPs the Pandits face the struggle of seeking legal and political recognition of their condition. It is from the struggle for recognition that we should begin a discussion about what it means to be a refugee in one’s own country.

Featured image credit: Sharda Peeth by Yasirali26. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post To be a refugee in one’s own country appeared first on OUPblog.

Italy, and the UK decision to expand Heathrow

The Italian public has decisively turned against major infrastructure projects. Will the UK follow in Italy’s footsteps after the decision to expand Heathrow airport?

As Graham Ruddick put it in the Guardian on 26 October, ‘One by one, Theresa May’s government is giving the go-ahead to major infrastructure projects that will cost taxpayers billions of pounds.’ By doing so, she signalled her determination to promote growth and the creation of new jobs, as well as to offset the oft predicted economic downturn following Brexit. According to The Independent, the business case for the expansion of Heathrow airport was ‘overwhelming.’ Admittedly, there were strong objections on environmental grounds, yet ‘if the green argument is judged to be paramount, then we would not build new capacity at all, and that would have very serious consequences for economic growth.’

Until recently in the UK, the case for economic growth appeared to be fairly uncontroversial. This was in stark contrast to Italy where economic modernization has for some time been contested and opposed, effectively thwarting successive Prime Ministers’ attempts to relaunch major public works. Disaffection with the myth of material progress and well-being has spread through society, hence the critique of economic growth and modernization is not restricted to intellectuals or ‘loony greens.’ In 1986 the country saw the birth of the Slow Food Movement, whose Manifesto proclaimed that ‘In the name of productivity, the “fast life” has changed our lifestyle and now threatens our environment and our land (and city) scapes.’ Its founder, Carlo Petrini, later developed it into a global organization. This was followed by the Movement for Happy Degrowth, founded at the beginning of the 2000s and inspired by the philosophy of Serge Latouche, a radical opponent of the idea that economic growth equals progress.

Similar ideas have been at the roots of sustained opposition to grandiose public works projects like the construction of a high-speed railway line in the Susa Valley near Turin, or the much publicized bridge linking Sicily to the mainland. In the Susa valley, the NO TAV movement against high-speed trains developed in the 1990s and has since been able to gather widespread popular support among local residents and public administrators. As their website states: ‘The locals’ concerns and proposals are being completely ignored in the name of the only Modern God: money.’

While the mainstream political parties, primarily Forza Italia under Silvio Berlusconi, and the Democratic Party under Matteo Renzi, endeavoured to popularize bold narratives of innovation and growth, the 5-Star Movement led by ex-comedian Beppe Grillo embraced the protest movements, rapidly becoming the second largest party in Italy. In June 2016, two candidates of the Movement were elected mayors of Rome and Turin, Virginia Raggi in the capital city and Chiara Appendino in Turin. Both have since clearly demonstrated their determined opposition to major public works and events. The former scuppered Italy’s bid to hold the 2024 Olympic Games in Rome and the latter reiterated her disapproval of the high-speed railway project, appointing prominent leaders of the NO TAV movement to positions of responsibility in her local government.

Will the opposition to the expansion of Heathrow airport spearhead comparable popular movements such as the ones in Italy in the UK? Has the vote in favour of Brexit already signalled that a majority of people no longer prioritise economic growth if it is perceived to threaten their lifestyle? While Theresa May’s clear-cut commitment to major new public works post-Brexit indicates that for her material expansion and progress remain overriding concerns and are non-negotiable, she may soon discover, as Italian prime ministers already have, that the public appetite’s for growth has greatly diminished, if it is deemed to come at the expense of their quality of life.

Featured image credit: London Heathrow airport by graceful. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Italy, and the UK decision to expand Heathrow appeared first on OUPblog.

December 1, 2016

Fighting the stigma of HIV and AIDS

World AIDS Day is held on the 1 December each year, uniting people in the fight against HIV and promoting the prevention and treatment of HIV. This year’s theme is ‘HIV Stigma: Not Retro, Just Wrong’ which is focused around ending the stigma surrounding HIV which makes the lives of those living with this disease extremely difficult.

To mark World AIDS Day 2016 we asked people working and researching in the field how they think views on HIV and AIDS have change over the past ten years, focusing in particular on outdated stereotypes, challenging myths, and the developing positivity towards finding a cure. In addition, we have provided a series of articles from a selection of journals on the topic of HIV – freely available to read until 1 March 2017.

“Second-line HIV Treatment in Ugandan Children: Favorable Outcomes and No Protease Inhibitor Resistance” by Ragna S. Boerma, Cissy Kityo, T. Sonia Boender, et al. in the Journal of Tropical Pediatrics

“Exclusive Breast-feeding Protects against Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV-1 through 12 Months of Age in Tanzania” by Karim Manji, Christopher Duggan, Enju Liu, et al. in the Journal of Tropical Pediatrics

Over ten years ago, it was thought that the HIV/AIDS epidemic could never be controlled without a vaccine. Since then, enormous progress has been achieved in increasing access to antiretroviral therapy, pre exposure prophylaxis, and reducing mother to child transmission of HIV. Although a vaccine would still be the most effective way to tackle the HIV/AIDS epidemic, the absence of a vaccine is no longer an insurmountable obstacle to controlling HIV.

In 2015, UNAIDS set the ultimate goal of eliminating HIV transmission by 2030 using existing tools and evidence-based interventions. The UNAIDS 90-90-90 initiative calling for 90% diagnosed, 90% treated, and 90% virally suppressed by 2020 was a turning point in how we approach HIV prevention. Although we do need a vaccine against HIV, working towards the 90-90-90 targets will bring us closer to eliminating HIV transmission.

– Quique Bassat, Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Tropical Pediatrics

“Impact of Cigarette Smoking and Smoking Cessation on Life Expectancy Among People With HIV: A US-Based Modeling Study” by Krishna P Reddy, Robert A Parker, Elena Losina, et al. in The Journal of Infectious Diseases

“Incidence of AIDS-Defining Opportunistic Infections in a Multicohort Analysis of HIV-infected Persons in the United States and Canada, 2000–2010” by Kate Buchacz, Bryan Lau, Yuezhou Jing, et al. in The Journal of Infectious Diseases

Over the past decade, our emphasis regarding HIV infections has changed enormously. We now attempt to treat all persons with HIV, not just a select few. As a result, life spans of individuals treated with antiretroviral combination regimens approach those who are not infected, and outdated stereotypes about persons with HIV are disappearing. We are also becoming more concerned with other non-infectious factors that may be problematic for HIV-infected individuals, such as excessive smoking. Greater efforts are being directed to preventing HIV infections with approaches such as pre-exposure prophylaxis. Finally, investment in cure research is also considerable, so that the goal of reducing and possibly eliminating HIV infection may become a reality in the decades ahead.

– Martin Hirsch, Editor-in-Chief of The Journal of Infectious Diseases

Releasing heart shaped ballons to commemorate those that are lost from HIV and AIDS globally on world aids day december 1st. Photographer Linda Rehlin. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Releasing heart shaped ballons to commemorate those that are lost from HIV and AIDS globally on world aids day december 1st. Photographer Linda Rehlin. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.“Using observational data to emulate a randomized trial of dynamic treatment-switching strategies: an application to antiretroviral therapy” by Lauren E Cain, Michael S Saag, Maya Petersen, et al. in the International Journal of Epidemiology

“CD4+ T cell recovery during suppression of HIV replication: an international comparison of the immunological efficacy of antiretroviral therapy in North America, Asia and Africa” by Elvin H Geng, Torsten B Neilands, Rondolphe T Thièbaut, et al. in the International Journal of Epidemiology

“Data Resource Profile: Network for Analysing Longitudinal Population-based HIV/AIDS data on Africa (ALPHA Network)” by George Reniers, Marylene Wamukoya, Mark Urassa, et al. in the International Journal of Epidemiology

One of the massive shifts over the last ten years has been in viewing HIV/AIDS as a unique, unprecedented epidemic – which it once was in many respects – to a condition that can be successfully managed for decades with effective antiretroviral therapy. This realisation has been driven by state-of-the-art epidemiologic research. This includes sophisticated observational analyses that allow researchers to approximate complex treatment strategies (Cain, et al), comparisons of treatment responses showing comparable treatment outcomes across the globe (Geng, et al,) and research platforms for population-based HIV research from across sub-Saharan Africa (Reniers, et al). These examples from the last 12 months are just a few examples of the epidemiological research that has helped to propel our understandings of HIV/AIDS forward at a remarkable rate.

– Landon Myer, International Journal of Epidemiology

“HIV-related stigma and universal testing and treatment for HIV prevention and care: design of an implementation science evaluation nested in the HPTN 071 (PopART) cluster-randomized trial in Zambia and South Africa” by James R Hargreaves, Anne Stangl, Virginia Bond et al. in Health, Policy and Planning

“Resource needs and gap analysis in achieving universal access to HIV/AIDS services: a data envelopment analysis of 45 countries” by Wu Zeng, Donald S Shephard, Carlos Avila-Figueroa, and Haksoon Ahn in Health, Policy and Planning

“Did PEPFAR investments result in health system strengthening? A retrospective longitudinal study measuring non-HIV health service utilization at the district level” by Samuel Abimerech Luboga, Bert Stover, Travis W Lim, et al. in Health, Policy and Planning

Over the last decade, we’ve seen more people with HIV living as long, healthy lives as their HIV-negative peers. Though HIV is thankfully no longer an automatic death sentence, myths, stereotypes, and gaps in the public’s understanding of HIV/AIDS persist, even in the United Kingdom. Meanwhile in other parts of the world where human rights and social protection for populations at risk are virtually non-existent, stigma and discrimination are much more deeply rooted, hindering prevention and treatment efforts. In Russia for example, new HIV infections continue to increase especially rapidly among injecting drug users, but the government still prohibits opioid substitution therapy, and prefers to blame and criminalise drug users. So despite real progress in recent decades, it’s crucial to push governments further to fight stigma, heed scientific evidence, and respond to the epidemic by respecting, not violating, human rights.

– Professor Peter Piot, Health, Policy and Planning

“HIV-associated lymphoma in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: shifting the immunological landscape” by Virginia Carroll and Alfredo Garzino-Demo in Pathogens and Disease

The response to the global HIV epidemic has been unprecedented. It has changed much of the way in which the world approaches health financing. Over the last 10–15 years, high-income countries have transferred large sums of money so that lower-income countries are provided with emergency HIV prevention and treatment programmes. Through highly successful programmes such as the Global Fund and PEPFAR, over $8 billion is made available each year to over 100 countries. The volume and rapid scale-up of this investment has undoubtedly resulted in tremendous health and economic savings around the world. So much so that the WHO and United Nations now seemingly see the end of AIDS in sight over the next 15 years. However, it is important to realize that whilst great gains have been achieved and the present is much better than the past, the future of HIV is still troubling. There is no vaccine or a cure. Furthermore, the cycle of HIV infection has not been broken: recent data from Southern Africa shows that young women are acquiring HIV from adult men, while men acquire HIV later in life, and continue the cycle of new infections; in Eastern Europe and Central Asia HIV prevalence is still increasing overall; and generally in other regions of the world there is no clear decline in HIV epidemics among men who have sex with men. Paradoxically, the lack of progress in some instance might be due to the success of therapeutic programs, which has decreased the sense of emergency once associated with HIV infection, and generated some degree of complacency and a false sense of security. The large international funding for HIV is not sustainable in the medium term and lower income countries are unlikely to be able to cover shortfalls and cover needed increases in resources. Therefore, without the needed research, medical technologies, political commitment to human rights and people-centered actions, and financial gaps mean that unfortunately HIV will be with us for decades to come.

– David Wilson, Pathogens and Disease

Featured image credit: Support For International AIDS Memorial Day by Sham Hardy. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Fighting the stigma of HIV and AIDS appeared first on OUPblog.

Winnicott: the ‘good-enough mother’ radio broadcasts

Our appetite for books on baby care seems unquenchable. The combination of the natural curiosity and uncertainty of the expectant mother, the unknowable mind of the infant, and the expectations of society creates a void filled with all kinds of manuals and confessionals offering advice, theory, reassurance, anecdotes, schedules… and inevitably, inconsistency, disagreement, and further anxiety.

One figure who has remained relevant through the passing generations, very much due to his resistance to giving practical advice which inevitably becomes faddish over time, is the English paediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott (1896-1971). While many of his ideas persist 70 years on in the form of frozen, if familiar, sound bites: the ‘good-enough mother’; the ‘ordinary devoted mother’; that ‘there is no such thing as a baby, only a baby and a mother’; and the ‘transitional object’ (the security blanket) to name a few, his message remains timeless.

The core of Winnicott’s work on parenting was given through nearly 60 radio broadcast talks on the BBC, many on Women’s Hour, across the two decades from the middle of the Second World War. The subject – expressions of psychoanalytic concepts for mothers – was potentially risky to the corporation, culturally progressive, and to Winnicott and his producers at a time of seismic social change, vitally important. While he was a natural communicator who had earned his spurs in the crowded children’s wards of London hospitals, Winnicott needed to be moulded into a broadcaster capable of expressing complex and sensitive issues without scandalising his audience of unsuspecting ordinary mothers: a task which required a series of astute, sensitive, and firm producers. Reinforcing the emerging role of women after the war as cultural consumers and cultural commissioners, all Winnicott’s producers and collaborators at the BBC were women.

What Irks the Ordinary Mother? [CW 6:1:7] From “The Ordinary Devoted Mother and Her Baby” BBC Broadcast series.

Winnicott’s speaking style, lacking the demotic rhythm of his contemporary, the ‘radio doctor’ Charles Hill, was straightforwardly relatable and reassuring, as he told mothers “You will be able to see that really I am saying quite ordinary obvious things”, or, to take a topical example: “by devoted, I simply mean devoted”. Winnicott’s broadcast voice has a relaxed, almost murmuring, quality and his relatively high pitch was frequently mistaken for the voice of a woman. His thoughtful manner, his extensive use of pre-recorded documentary conversation between mothers, and his vocal hermaphroditism, allowed him to completely relinquish the role of an educated male expert talking to the uneducated female public. He was instead beside the listener, speaking on behalf of the infant, putting into words what the mother already knew.

Winnicott’s career emerged during a period of wartime where it was only too easy for state propaganda, regarding physical care, to supersede all else. Truby King was campaigning for food hygiene while proposing rigid scheduled feeding on the basis that regular infantile hunger built strength of character. Many United Kingdom maternity wards employed practices of shocking insensitivity to the mother-baby relationship, in which the physically-orientated ‘expertise’ of the nurses countermanded the new mother’s basic instincts.

Winnicott, on the contrary, argued that the mother herself is the specialist in her own baby, and that professionals must not take away the mother’s confidence in her instincts and natural knowledge. He professed himself “allergic to propaganda”, telling mothers “you will be relieved that I am not going to tell you what to do,” “but,” he continued, “I can talk about what it all means.” He was later accused of de-intellectualising mothers, by his insistence that intelligence – as compared to love – was both unnecessary and insufficient for mothering, but I think rather he would sympathise with the current trend of expressing this attitude as: mothers have had enough of experts.

D. W. Winnicott for The Collected Works of D. W. Winnicott. Reproduced with permission.

D. W. Winnicott for The Collected Works of D. W. Winnicott. Reproduced with permission.He was not afraid of what he called “the seamy side of home life”, and wanted mothers to hear that he knew about the role of non-loving feelings in infant care. He imagined the mother who allows herself to say “Damn you, you little bugger” to her baby, and in another broadcast gave airtime to reasons a mother might hate – as well as love – her child.

Winnicott’s own work was soon overshadowed by Benjamin Spock, who acknowledged his debt to Winnicott by crediting him as the underlying theoretical model of his childcare guidance manual; that is, while giving the very kind of advice Winnicott had expressly avoided and even dismissed as unhelpful.

Spock said of Winnicott that his contribution “all adds up to reliability and love”, but this only tells the first half of the story. Winnicott’s most enduring mothering idea is of the ‘good-enough mother’, a phrase intended to liberate parents from the millstone of aspirational perfection. Once the infant knows the mother can reliably provide during the baby’s early state of complete dependence, it is through the bust-ups and bungles of being good-enough rather than perfect that the infant finds out about his own developing needs. The child discovers he is not within the suffocating realm of parental omniscience, nor are the parents within the tyranny of the baby’s omnipotent control. He finds that rage and phantasies of destruction do not magically destroy the world, except in his creative imagination. Beyond this lies a widening horizon of emotional development: anger, disappointment, reparation, and eventually, independence, and gratitude.

Featured image credit: Radio by ArtmoGraphicDesigner. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Winnicott: the ‘good-enough mother’ radio broadcasts appeared first on OUPblog.

Lessons from the global response to HIV/AIDS

Since 2001, the response to HIV/AIDS has evolved into an unprecedented global health effort, extending access to treatment to 17 million people living with HIV across the developing world, some considerable successes in HIV prevention (especially regarding mother-to-child transmission), and becoming a very significant aspect of global development assistance. The present is characterized by a shift in the global health and development agenda (giving HIV/AIDS much less weight), a declining outlook on HIV/AIDS funding, and a prospect of ending AIDS as a major global health challenge through renewed investments in the HIV/AIDS response. To motivate such investments against competing objectives, but also to inform policy responses to future health shocks, it is important to understand the health and development impacts of HIV/AIDS, and the extent to which they have been reversed by the response to it.

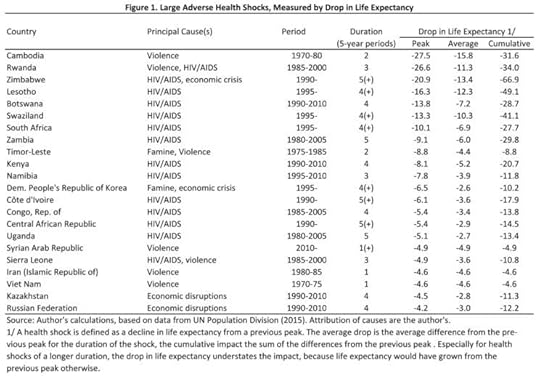

Large Adverse Health Shocks, Measured by Drop in Life Expectancy by Markus Haacker. Used with permission.

Large Adverse Health Shocks, Measured by Drop in Life Expectancy by Markus Haacker. Used with permission.While the global HIV/AIDS response has in part been motivated by development and security concerns, the direct and obvious impacts arise in the sphere of health. Indeed, the magnitude of the health shock caused by HIV/AIDS has been staggering – the only examples of catastrophic declines in life expectancy surpassing the impact of HIV/AIDS in the worst affected countries are two examples of extreme genocidal violence, and HIV/AIDS has been the sole or partial cause of 15 of the 20 worst examples of declines in national-level life expectancy, with drops in life expectancy of between 5 years and 21 years, according to data from the United Nations Population Division. On top of this, HIV/AIDS-related health shocks have been much more persistent than those caused by violence, famine, or economic crises.

While the global response to HIV/AIDS has been framed as an economic development (as well as health) challenge, HIV/AIDS is not a disease generally associated with low levels of economic development. Similar to TB and malaria, HIV/AIDS contributes very little to the burden of disease across high-income countries. The burden of disease from TB and malaria, however, is more geared towards low–and lower-middle–income countries. HIV/AIDS stands out as its impacts are highly concentrated – largely in Southern and Eastern Africa – where the disease and response to it have been the dominant drivers of health outcomes over the last decades.

One of the biggest achievements of the global response to HIV/AIDS is the comprehensive scaling-up of treatment, reversing much of the steep declines in life expectancy. In Kenya, the loss in life expectancy owing to HIV/AIDS peaked at 8 years, which has now fallen to around 2 years. Remarkably, treatment coverage (as of 2014) has been uncorrelated with GDP per capita, and has generally been high in the countries worst-affected by HIV/AIDS. The HIV/AIDS response has been successful in overcoming capacity constraints associated with a low level of economic development, or caused by a steep increase in demand for health services. While the global effort at scaling up treatment for people living with HIV started out with projects providing proof of the concept that antiretroviral treatment could (and should) be delivered in resource-limited settings, the global HIV/AIDS response has proven that effective large-scale delivery of specific health services is possible in almost any setting.

Apart from the health impacts of HIV/AIDS, the global response to HIV/AIDS was in part motivated by concerns about the socio-economic consequences, and potential reversals of gains in economic development owing to HIV/AIDS. However, the evidence on such economic consequences of HIV/AIDS is thin, and the apparent impacts small. Growth of GDP per capita in countries with the highest prevalence of HIV has not been noticeably lower than in other countries, and empirical studies including a measure of the impacts of HIV/AIDS in a growth regression tend to find a statistically or substantially insignificant effect.

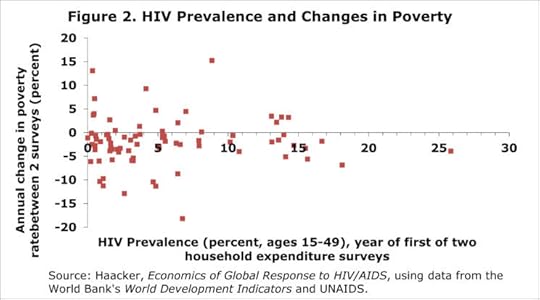

HIV Prevalence and Changes in Poverty by Markus Haacker. Used with permission.

HIV Prevalence and Changes in Poverty by Markus Haacker. Used with permission.Perhaps more surprisingly, HIV/AIDS also did not have an obvious impact on poverty rates. While the adverse impacts of HIV/AIDS or deaths overall on affected households are well-documented, nation-wide poverty rates did not increase in countries with high HIV prevalence. This could suggest that surviving household members recover economically following a death and its immediate adverse consequences, or that some members of a community gain (e.g., from employment opportunities) as others lose from illness and deaths.

In conclusion, the global response to HIV/AIDS has delivered in terms of reversing a catastrophic health shock, and extending access to treatment across developing countries, and has created a template for advocacy and the planning of large health interventions. Much of the feared broader development consequences of HIV/AIDS have not materialized, raising questions on the form or magnitude of economic returns to investments in health, and the linkages from health events to economic outcomes.

Featured Image Credit: World Healthcare map pill by Jnittymaa0. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Lessons from the global response to HIV/AIDS appeared first on OUPblog.

Elimination of violence against women reading list

The World Health Organization estimates that “about 1 in 3 (35%) women worldwide have experienced either physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence in their lifetime.” Few data exists and measurements can vary substantially across cultures, but evidence suggests that even more women face psychological violence: 43% of women in the European Union have encountered “some form of psychological violence by an intimate partner in their lifetime.”

Violence against women is a global pandemic and has resulted in immense costs to society. Medical, judicial, and lost productivity bills accumulate in the billions. According to the UN, “violence against women impacts on, and impedes, progress in many areas, including poverty eradication, combating HIV/AIDS, and peace and security.” With discrimination and institutionalized inequalities between men and women still existing, much societal progress still needs to be made. To highlight issues pertaining to violence against women and to encourage deeper reflection, we compiled a reading list that explores various international issues of gender-based violence.

Intimate Partner Violence and Abuse by Jill Theresa Messing

Intimate partner violence—the continual and systematic exercise of power and control within an intimate relationship that often also includes physical and sexual violence—has emerged as a significant and complex social problem warranting the attention of social workers. Jill Theresa Messing examines the prevalence, risk factors, protective factors, consequences, interventions, and challenges in facing intimate partner violence. Risk and protective factors have been identified at the individual, family, community, and societal levels. Some of these risk factors for repeat and lethal violence have been organized into risk assessment instruments that can be used by social workers to educate and empower survivors.

From Global to Grassroots by Celeste Montoya

How can transnational activism aimed at combating violence against women be used to instigate changes on the local level? Focusing on the case of the European Union, Celeste Montoya provides empirical and intersectional feminist analysis of the transnational processes that connect global and grassroots advocacy efforts, with a particular emphasis placed on the roles played by regional organizations and networks. She provides extensive data and contributes to theory on transnational politics, social movements, international organizations, public policy, and intersectional gender politics.

The Political Economy of Violence Against Women by Jacqui True

Violence against women is a major problem in all countries, affecting women in every socio-economic group and at every life stage. Nowhere in the world do women share equal social and economic rights with men or the same access as men to productive resources. Jacqui True develops a feminist political economy approach to identify the linkages between different forms of violence against women and macro structural processes in strategic local and global sites – from the household to the transnational level. In doing so, it seeks to account for the globally increasing scale and brutality of violence against women. She provides strong evidence that increasing women’s access to productive resources and social and economic rights lessens their vulnerability to violence across all societies.

“Ellison Sau, Project Manager for the Men Against Violence Against Women (MAVAW) program at Live and Learn, holding a ‘Stop! Violence against women!’ sign” by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

“Ellison Sau, Project Manager for the Men Against Violence Against Women (MAVAW) program at Live and Learn, holding a ‘Stop! Violence against women!’ sign” by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr. Domestic Violence in the LGBT Community by Betty Jo Barrett

Since the mid 1980s, a growing body of theoretical and empirical literature has examined the existence of intimate partner violence (IPV) in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) communities. Collectively, this research has highlighted myriad ways in which the social and structural marginalization of gender and sexual minority populations create unique vulnerabilities for IPV that are not shared by cissexual and heterosexual individuals. Betty Jo Barrett provides an overview of this scholarship to inform strength-based social work practice with and for LGBT survivors of domestic violence at the macro, mezzo, and micro levels.

The Unsafe Sex by Nalini Natarajan

Not too long ago, India woke up to the heart-rending horror of the “Nirbhaya” rape case. While the brutal violence against the victim sent shockwaves throughout the country, the rapists (as well as other men on the streets) caused further moral outrage by blaming the victim for being out at night and holding her responsible for her rape. What does this signify? Is there an ongoing visceral war waged by men against women? Nalini Natarajan addresses this phenomenon and provides a socio-historical and cultural context to explain why public violence against women is rooted in the binary within which they are viewed—women as, ideally, a source of dignity within the home, while being a source of shame outside it. Probing the intensification of this war on women’s bodies, it delves into issues about their safety and security in an increasingly unpredictable world.

Earning Your Ally Badge: Men, Feminism, and Accountability by Michael A. Messner, Max A. Greenberg, and Tal Peretz

What does it mean for men to join with women as allies in preventing rape and domestic violence? Drawing from interviews with all three cohorts of men and women, Michael A. Messner

Max A. Greenberg, and Tal Peretz probe the promise and contradictions of men’s work as allies. Men who do feminist work are frequently treated as “rare men” who benefit from a “pedestal effect.” Some men have ridden this “glass escalator” to “rock star” status in the antiviolence field. On the other hand, men are also subjected to critical scrutiny and sometimes distrust from women. Men of color sometimes experience an especially rapid escalation in status in the field, but they also are often subjected to acute sorts of racialized scrutiny. The chapter examines the ways that differently situated men—often with women’s mentorship and guidance—define accountability as they strategically navigate the pedestal effect and critical scrutiny.

Violence edited by Bonnie G. Smith

Violence against women has been argued within feminist circles as the exercise of power over women by men in the name of preserving male honor and manhood in general. Feminist scholars have argued that violence committed against women is socially, culturally, and geographically specific, and, most importantly, gendered. This entry contains an overview and a comparative history of violence against women.

Domestic Violence in the LGBT Community by Rebecca Jane Hall

Feminist struggles since the 1970s have made important gains in how American state and interstate organizations respond to gender-based violence, challenging structural inequalities that increase vulnerability to gendered, racialized, geographic, and socioeconomic violence. Rebecca Jane Hall outlines three feminist antiviolence frameworks, exploring their intersections, contradictions, gains, and shortcomings. She then discusses current challenges in the antiviolence landscape, assessing the potential of those frameworks for transformative change. Canada is used as a case study, drawing on comparisons with countries from both the global North and South. Feminist action through international forums is also examined.

Featured image credit: “We Can Put a Stop to Violence against Women – Billboard – Sydney – Australia” by Adam Jones. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Elimination of violence against women reading list appeared first on OUPblog.

What Burton’s ‘Anatomy of Melancholy’ tells us about modern day mood disorders

Coming to us through the great illustrative tradition, as well as medical and literary works, Melancholy is a perennially alluring idea. Still, the thought that a seventeenth-century work on melancholy by neither a doctor nor a philosopher could illuminate twenty-first-century concerns about mood disorders–my contention about Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy–may seem a bit far-fetched.

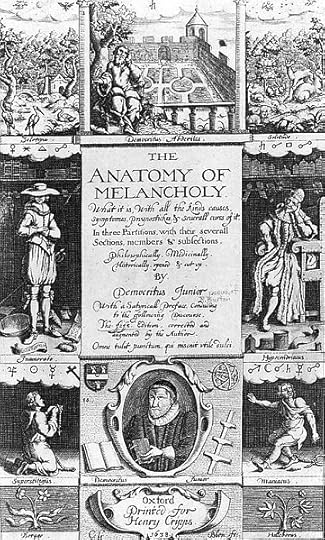

Whatever its genre (and Burton’s 1621 book has been seen as a literary work, an encyclopedia, a satire, a political tract, a health manual and much besides), and despite Burton’s identification with the pre-Socratic philosopher Democritus who sought the seat of melancholy by dissecting animals, shown below by Rosa in 1650, we don’t usually assign The Anatomy of Melancholy a place alongside the great Early Modern philosophical treatises.

Notably extra-philosophical, and undoubtedly less incisively systematic or original than that by such as Hobbes, Locke, Descartes, or Spinoza, Burton’s writing is nonetheless worth our philosophical attention. By placing feelings and emotions at its heart, it avoids the ratio-centric emphasis of so much Western theorizing, for example. Addressing abnormal moods understood as disease, it begins with what can go wrong with feelings and attitudes, and why, rather than offering an account dominated by the normal case with pathology an ill-fitting afterthought. Then, wrapped in a broadly Aristotelian dualism that gracefully, if obscurely, avoids the mind-body “problem”, it is able to side-step implications of the Cartesianism that dominated psychology until almost our present century.

Frontispiece for the 1638 edition of Robert Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Frontispiece for the 1638 edition of Robert Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. Democritus in Meditation by Salvator Rosa. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Democritus in Meditation by Salvator Rosa. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.So, some reasons to read the Anatomy for its philosophical psychology lie in the omissions and misapprehensions we now recognize in the past writing of Early Modern and Modern times. But there is more. Those omissions and misapprehensions have had far-reaching sequelae that affect our present understanding of mood and emotion in present times, also (and this quite apart from the contested relationship between melancholy of old and today’s depression). The Modern period spawned the mind-body problem, but also psychiatry as we know it, as well as the rigid, ontologically-freighted categorical classification that gives us entities like Depressive Disorder, and the nineteenth-century conception of disease framing psychic complaints as analogous to other medical ones in every respect.

Many of these consequences in how orthodox psychiatry views mood disorder today are coming undone. Newer, critical assessments are challenging such legacies from the Modern era, leaving knowledge about affective disorder, long thought part of settled science, in growing disarray. What disordered moods are, how they come about, and their relation to social norms, as well as how to treat and respond to them – these all seem increasingly, and unsettlingly, uncertain. And particularly if there can be found congruence linking theoretical tenets and practical recommendations, as there seems to be in Burton’s Anatomy, such a context of uncertainty invites us to look again at works from past times.

Burton saw melancholy as a growing and alarming epidemic, a response to the unsettled political and religious world of his era as much as a question of imbalanced humors. And in this respect, too, the Anatomy seems a fit text for our contemporary times, where the symptoms of depression are associated with most mental disorders; “depression” is recognized as the common cold of psychological medicine (just as melancholy was in Burton’s day); and epidemiological language is increasingly employed.

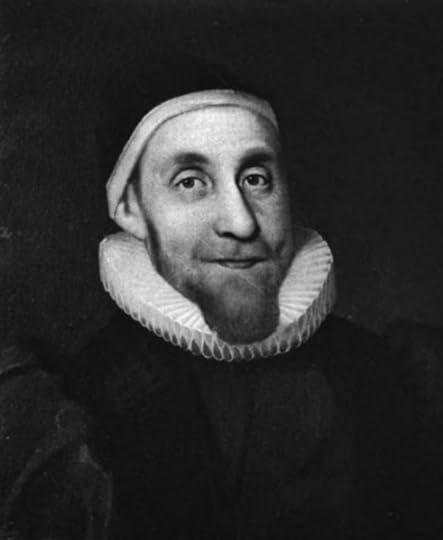

Robert Burton, English scholar and vicar at Oxford University. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Robert Burton, English scholar and vicar at Oxford University. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. At the center of these changes, recognition of the economic and social costs of mood disorders such as depression has since the beginning of the twenty-first century directed attention towards public health methods and approaches, with their emphasis on prevention. In addition, forms of cognitive therapy for depression have emerged as the main treatment alternative to psychopharmacology. To me, these trends seem a kind of real-world, present-day manifestation of the ideas Burton espoused about early prevention as the practice of a Stoic-inspired care of the soul, itself a recognizable antecedent of cognitive therapy. Paired with new ideas about the nature of mental disorders, such very Burtonian preventives and “cures” encourage a focus on the implicative connections between underlying theoretical conceptions of disorder, and these practical prescriptions. With its attention to symptoms, and to the effect of habituation brought about by repetitive, negative “melancholizing,” the picture of disease depicted by Burton resembles nothing so much as the network models of depression described (by Kendler and colleagues) today. And the connection between disease model and preventive principles found in the Anatomy offers us guidance on one way, at least, to think about issues involving depression in contemporary times.

Featured image: The melancholic figure of a poet leaning on an inscribed block of stone. Engraving by J. de Ribera. CC-BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What Burton’s ‘Anatomy of Melancholy’ tells us about modern day mood disorders appeared first on OUPblog.

Calcutta roads

Arterial roads in cities have peculiar ways of acquiring distinct identities. The character of each main road, the lifestyle of its residents, their occupations, their social habits, the architecture of their houses and shops, their cultural tastes (even their mannerisms and ways of speaking) – all these shape every road in different ways.

The three roads that criss-cross the city of Calcutta (Bagbazar, Theatre Road, and Rashbehari Avenue) from the east to the west still retain the distinct signatures from the times when they were born – while also accommodating the changes that are taking place now. A tradition of collective memory has reinforced the continuity of such distinctiveness – which is usually reduced in the minds of Calcutta citizens into three stereotypes:

(i) Bagbazar, as representing the legacy of Bengali Hindu aristocracy, their middle class descendants and orthodox living style of north Calcutta, as well as the birth of the Bengali theatre; (ii) Theatre Road (renamed as Shakespeare Sarani), in the centre of Calcutta, regarded as an Anglicized part of the city – a descendant of the White Town of the early colonial era, when it was carved out by the British bureaucrats and European traders as their exclusive domain. The road still remains alienated from the Bengali socio-cultural mainstream psyche. It is identified in the Bengali public mind today with the cosmopolitan elite, who have replaced the earlier colonial elite, with their new corporate business house offices in multi-storied buildings; (iii) Rashbehari Avenue, on the contrary, continues to be symptomatic of a Bengali middle class living style that reconciles its traditional cultural tastes with those of modern cosmopolitan requirements – the foundations of which were laid by the Bengali residents (lawyers, college teachers, among others) who started settling here back in the early decades of the 20th century.

The three roads that criss-cross the city of Calcutta from the east to the west still retain the distinct signatures from the times when they were born.

The separate identity of each road is captured in the popular sayings and beliefs. One humorous rhyme in early 19th century Calcutta describes Bagbazar as `ganjar adda’ (centre of hemp smoking) – thanks to the peculiar whim of a local grandee Shibchandra Mukhopadhyay who, in his palatial ancestral house, set up a hemp-smoking club. The floor was carpeted with tobacco leaves and the walls were made from hemp leaves! Similarly, Theatre Road was known among the indigenous populace as `Purana Nautchghar-ka-rasta’ (meaning ‘old road of dance-drama performances’), since it was associated in their minds with the entertainments of the British inhabitants who built a hall called the Chowringhee Theatre in 1818, but which was destroyed in a fire in 1839.

Rashbehari Avenue began its journey with a rather disreputable identity. In the early 20th century, the municipal authorities dug an underground sewerage system in the surrounding fields to carry human waste to be disposed of into the Hooghly river. The road which gradually emerged on its surface, was used to be known for many years as Main Sewer Road, both in official records and popular usage, even after respectable middle class Bengali professionals had built houses there. It was under their pressure that this malodorous association was obliterated with the renaming of the road after a well-known Bengali advocate.

But behind such singularly distinct main roads, there are streets, lanes, and by-lanes, where one can come across denizens who may not fit into the socio-cultural model that dominates the thoroughfares in the front. They are the laboring classes who manually serve the civic requirements of the urban municipalities, as well as the daily needs of the upper and middle class citizens. Behind every main road therefore, we find slums or ‘bustees’, built by these laboring classes in fallow lands. The less fortunate live on pavements – setting up temporary shacks every night, after coming back from work. It is this underbelly of the urban system which really keeps Calcutta’s roads going.

Featured image credit: Rashbehari Avenue – Kolkata, 2011, by Biswarup Ganguly. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Calcutta roads appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers