The little known history of Cuba’s intervention in Africa during the Cold War

When Nelson Mandela visited Havana in 1991, he declared: “We come here with a sense of the great debt that is owed the people of Cuba. What other country can point to a record of greater selflessness than Cuba has displayed in its relations to Africa?”

In all the reflections upon the death of Fidel Castro, his contribution to Africa has been neglected–because most Americans are unaware that Castro’s Cuba changed the course of southern African history. While Americans celebrated the peaceful transition of apartheid South Africa to majority rule and the long-delayed independence of Namibia, they had no idea that Cuba–Castro’s Cuba–played an essential role in these historic events.

During the Cold War, thousands of Cuban doctors, teachers, and construction workers went to Africa, while almost 30,000 Africans studied in Cuba on full scholarships funded by the Cuban government.

US officials tolerated Cuba’s humanitarian assistance, but not the dispatch of Cuban soldiers to Africa. There had been small Cuban covert operations in Africa in the 1960s in support of liberation movements, but the trickle became a flood in late 1975, engulfing Angola.

That Portuguese colony was slated for independence in November 1975, but civil war broke out several months earlier among the country’s three liberation movements–the MPLA, the FNLA, and UNITA. American officials were alarmed by the communist proclivities of the MPLA, but even they admitted that it “stood head and shoulders above the other two groups” which were led by corrupt men.

South African officials were also alarmed by the MPLA because of its implacable hostility to apartheid and promise to assist the liberation movements of southern Africa (UNITA and FNLA had proffered Pretoria their friendship).

By September 1975, the MPLA was winning the civil war. Therefore, Pretoria invaded Angola, encouraged by Washington. Secretary of State Kissinger hoped that success in Angola–defeating a pro-communist regime–would boost US prestige and his own reputation, pummeled by the fall of South Vietnam in April 1975.

The South Africans were on the verge of crushing the MPLA when 36,000 Cuban soldiers poured into Angola.

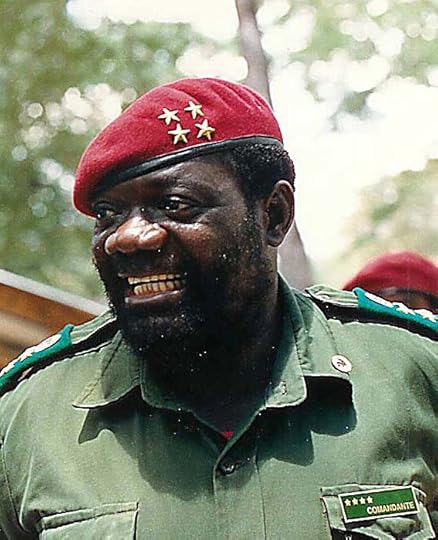

Jonas Savimbi, leader of the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), Eege Foto (1989) vum user ernmuhl. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Jonas Savimbi, leader of the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), Eege Foto (1989) vum user ernmuhl. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The intervention, the CIA concluded years later, had been “a unilateral Cuban operation designed in great haste.” The Agency was correct: Castro dispatched the soldiers without consulting the Kremlin. Soviet General Secretary Brezhnev, who was focused on detente with the United States, opposed Castro’s policy, and refused–for two months–to help transport the Cuban troops.

Castro’s decision also derailed his secret negotiations with Washington to normalize relations. Had Castro been pursuing Cuba’s narrow self-interest, he would not have sent troops to Angola.

What, then, motivated Castro’s bold move? The answer is provided by Kissinger. Castro, he wrote in his memoirs, “was probably the most genuine revolutionary leader then in power.”

The victory of the Pretoria-Washington axis, the installation of a regime in Luanda beholden to the apartheid regime, would have tightened the grip of white domination over the people of Southern Africa. Castro sent his soldiers to join the struggle against apartheid, a fight he deemed “the most beautiful cause.”

The Cuban troops turned the tide of the war, pushing the South Africans back into neighboring Namibia, which Pretoria illegally occupied.

“Black Africa is riding the crest of a wave generated by the Cuban success in Angola,” exulted The World, South Africa’s major black newspaper. “Black Africa is tasting the heady wine of the possibility of realizing the dream of total liberation.”

In Angola, the Cuban-backed MPLA government welcomed guerrillas from Namibia, South Africa, and Rhodesia. It became a tripartite effort: the Cubans provided most of the instructors, the Soviets the weapons, and the Angolans the land.

For apartheid South Africa it was a deadly threat. Therefore, for over a decade, Pretoria continued to battle the MPLA, attempting to install in its place the leader of UNITA, Jonas Savimbi, a man whom the British ambassador in Luanda labeled “a monster.”

The Angolan army was weak. Even the CIA conceded that the Cuban troops were “necessary to preserve Angolan independence,” but for the United States–under Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan–the Cubans were an affront.

Reagan joined Pretoria in supporting Savimbi. He tightened the embargo against Cuba and demanded that the Cuban soldiers leave Angola. Castro refused. It was a stalemate.

Until 1988. It was the Iran-Contra scandal that broke the logjam. Before that imbroglio weakened Reagan, the Cubans had feared a US attack on their island. But in its wake, Castro decided it would be safe to send Cuba’s best planes, pilots, anti-aircraft systems and tanks to Angola to push the South Africans out of the country, once and for all. “We’ll manage without underpants in Cuba if we have to,” Raul Castro told a Soviet general. “We will send everything to Angola.”

Once again, Fidel had defied the Soviet Union. Gorbachev, bent on detente with the United States, opposed escalation in Angola. “The news of Cuba’s decision … was for us, I say it bluntly, a real surprise,” he told Castro. “I find it hard to understand how such decision could be taken without us.”

In early 1988 the Cuban troops gained the upper hand in Angola. They were strong enough to cross the Namibian border, seize South African bases, “and drive South African forces further south,” the Pentagon noted. The situation was “one of the most serious that has ever confronted South Africa,” the country’s president lamented.

Pretoria gave up. In December 1988, it agreed to Castro’s demands: allow UN supervised elections in Namibia and terminate aid to Savimbi. Pretoria’s capitulation reverberated beyond Angola and Namibia.

In Mandela’s words, the Cuban victory over the South African army “destroyed the myth of the invincibility of the white oppressor … [and] inspired the fighting masses of South Africa. [It] was the turning point for the liberation of our continent–and of my people–from the scourge of apartheid.”

Featured Image credit: guards at the tomb of José Marti in Santiago, Cuba by PRA. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The little known history of Cuba’s intervention in Africa during the Cold War appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 237 followers