Oxford University Press's Blog, page 439

November 18, 2016

Word of the Year 2016: a ‘post-truth’, ‘alt-right’, ‘Brexiteer’ing’ explanation of political chaos

The lexicographers at Oxford Dictionaries have been at it again with their choice of Word of the Year 2016 – ‘post-truth’. Now call me a pedant but I’d have thought ‘post-truth’ is two words, or at the very least a phrase, (‘Pedant!’ I hear you all shout) but I’m assured that the insertion of a hyphen creates a compound word that is not to be sniffed at. And yet sniffing, I can assure you, is not what I am interested in unless its sniffing out how many of the words that made it to the WOTY 2016 shortlist actually combine to create a rather worrying account of a changing political world.

How then do words such as ‘post-truth’, ‘alt-right’, and ‘Brexiteer’ combine to explain the current situation of global political chaos?

The rise of ‘post-fact’ or ‘post-truth’ politics was a core element of the election of Donald Trump in the United States and the referendum decision in the UK to leave the European Union. To some extent it would be too simple to say that the problem was that politicians lied – politicians have and to some extent always will lie for the simple reason that politics is a worldly art – something more subtle and possibly far more dangerous has happened within democratic dialogue. Experts were rejected, fairy tales and fig leaves were promulgated, the public was undoubtedly duped but the deeper shift was undoubtedly the dominance of emotions above rationality.

Nigel Farage, by ‘Euro Realist’. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Nigel Farage, by ‘Euro Realist’. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.“Drain the swamp”, “Take back power”, “Blame foreigners”… are all nonsense terms that actually possess the substantive content of Word of the Year 2014 – ‘vape’. That’s it! In many ways democratic politics has been vaporized into a misty intangible nothingness that electing Donald and exiting the EU will for the US and UK (respectively) sort out.

The problem is that it won’t sort it out.

Loud and increasingly aggressive appeals to emotional and positive thinking may form the basis of ‘post-truth’ politics and be successful in the short-term but my sense is that in the long-term we are all going to be losers. Politics is boring. It grates and it grinds, it is complex and cumbersome, it really is “the slow boring of hard woods” to paraphrase Max Weber. The problem is that the Brexiteers and the ‘alt-right’ have all engaged in an orgy of strangely anti-democratic, anti-political sentiment raising. The paradox of the ‘post-truth’, ‘alt-right’, ‘Brexiteer’ triumvirate is that we now have a new class of elected ‘anti-politicians’ who have created and then surfed upon a wave of popular frustration with traditional democratic politics. The answer to every question below is the same:

“If we could only get rid of those bums in Washington!”

“If we could just release ourselves from those parasites in Brussels!”

“If we could just find some way of buttressing our borders!”

“If we could just remove those democratic safeguards and do what we know needs to be done!”

And that’s the problem. Did you notice it?

Within both the ‘belch of the Brexiteer’ and ‘the trump of alt-right’ lies a political subtext. That is, a political ideology that is arguably elitist, misogynist, nationalist, xenophobic, anti-this, anti-that, accusation-heavy, policy-lite, aggression-heavy, evidence-lite. I’m not saying that the ‘alt-left’, if there is such a term, are playing any less fast-and-loose with this precious and incredibly fragile thing called ‘democracy’; but I am saying that whether they meant to or not those loquacious lexicographers at the Oxford Dictionaries have provided an explanation of the contemporary political chaos.

‘Brexit’ and the ‘alt-right’ are overlapping terms fuelled by a particular form of ‘post-truth’ politics that in the long-term is likely to deepen the crisis of democracy.

All I can say is that in a climate of ‘post-truth’+‘alt-right’+‘brexiteer’ politics then we’d all better stay wide awake.

Featured image credit: Donald Trump, thumbs up. By Transition 2017. CC-BY-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

You can learn more about the Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year 2016.

The post Word of the Year 2016: a ‘post-truth’, ‘alt-right’, ‘Brexiteer’ing’ explanation of political chaos appeared first on OUPblog.

The life of Guglielmo Marconi [infographic]

Guglielmo Marconi was the man who networked the world. He was the first global figure in modern communications, popularizing as well as patenting the use of radio waves. Decorated by the Czar of Russia, named an Italian Senator, knighted by King George V, and awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics, Marconi accomplished more before the age of forty than many people do in a lifetime. This stateless “master of the electric waves” changed the world with his achievements in ways that resonate to this day.

A version of this article originally appeared on CBCbooks.

Featured image credit: Transmission Lines by Chris Hunkeler. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The life of Guglielmo Marconi [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

Disease prevention: helping health professionals

A new controversy about “how to stay well” hits the media at least once a week. Recent examples include: disease prevention claims made for various “healthy foods;” proposed policies to tackle the obesity pandemic, such as sugar or soda taxes; the benefits versus risks of long-term statins in healthy persons; the value of prostate cancer screening; and the accuracy of new genetic tests to predict future disease. In all these debates, the bottom line is much the same: the controversy is scientifically complicated, and senior medical experts take both sides — leaving the average health professional and patient confused.

Notably, the controversies which affect the largest number of persons, who are clinically well – including all the examples above – are about prevention: undergoing some medical or lifestyle intervention now, for promised health benefits later, in the long run. Scientific methods of analysis of the pros and cons of such preventive interventions are well developed but poorly understood by most practising health professionals, in both the clinical and public health communities.

Particularly badly taught in most health professional training is the principle that all preventive measures have the potential to do more harm than good. Preventive measures, virtually never “cost-free,” also have the potential to be a non-competitive use of scarce healthcare, public health, or personal resources. An important ethical issue thus presents itself: how does one rein in the promotion of scientifically unsupported preventive measures for well individuals, and for entire healthy populations? One thing is certain: this dubious practice is remarkably common in the annals of recent medical and public health history. That does not have to be the case.

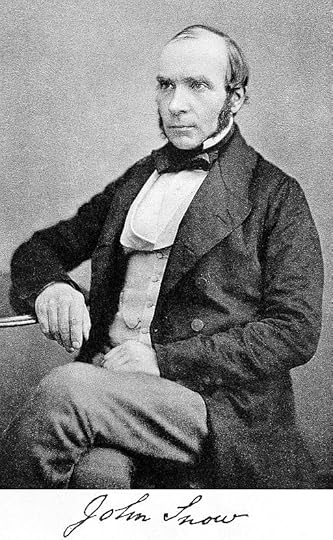

Dr. John Snow (1813-1858), British physician. Image by Rsabbatini at English Wikipedia. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Dr. John Snow (1813-1858), British physician. Image by Rsabbatini at English Wikipedia. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The basic science with the best credentials for evaluating the worth of disease prevention is epidemiology – the quantitative study of who becomes ill (or dies), who does not, why, and what can be done about it. Over a century ago, two of epidemiology’s most famous early investigators, John Snow and Joseph Goldberger, developed statistical methods for investigating the causes of two lethal epidemic diseases for which the cause was then unknown: cholera (in London) and pellagra (in the American South). The Snow and Goldberger stories still shed light on how modern epidemiologists assess a body of scientific studies to know whether a particular exposure credibly causes a given disease. (Exposure here can mean environmental hazards; potentially harmful or beneficial diets; aspects of lifestyle such as physical activity; or use of a recreational substance such as tobacco, alcohol, or illicit drugs.) These pioneers began the process of providing us with the epidemiological tools we have today for analysing modern scientific evidence about the pros and cons of proposed new preventive treatments or policies.

The core tool kit for such analyses is a distinct sub-set of Critical Appraisal checklists developed by epidemiologists over the last few decades to assess scientific studies’ quality. The epidemiological categories of scientific study most relevant to assessing any preventive intervention are:

Causation

Efficacy and effectiveness

Health economic (e.g. cost-effectiveness) appraisals

Systematic reviews/meta-analyses

Health inequalities impact assessments

These analytic tools, had they been robustly applied to preventive medical interventions that later turned out to have “done more harm than good,” might well have prevented major recent episodes of iatrogenic (doctor-caused) disease. Examples (many rejected only after widespread but premature use led to clear-cut health problems) include: routine hormone replacement therapy for menopausal women; an early rotavirus vaccine that occasionally caused intussusception, an acute surgical emergency in infants; prostate cancer screening with the PSA blood test; and oral beta-carotene (a Vitamin A pre-cursor) for cancer prevention — all within the last 30 years.

Preventive measures, virtually never “cost-free,” also have the potential to be a non-competitive use of scarce healthcare, public health or personal resources.

Claims made in recent years for the benefits of newly developed, but not yet thoroughly evaluated, medical preventive interventions have thankfully become more contentious. Witness the ongoing controversy around what sorts of evidence are scientifically required to justify lifelong daily statin treatment for a third of healthy US middle-aged and elderly adults, as recommended by American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association national guidelines in 2013 (or about 25% of that population in the UK, according to more conservative 2014 NICE Guidelines). Future generations of health professionals will need strong critical appraisal skills in order to sort out sound versus bogus interpretations of the complex science behind such controversies — thereby defending, as professional ethics require, their patients and local communities from potentially harmful or resource-inefficient prevention proposals.

Our experience is that every health professional is capable of mastering these analytic techniques, which are increasingly being included in undergraduate training worldwide. We call on those responsible for both basic and continuing health professional training to increase the content, in those educational programmes, of critical appraisal skills for evaluating prevention specifically. We are not suggesting that critical appraisal skills for the rest of clinical practice — diagnosis, prognostication, and assessing treatment effectiveness and efficiency — are not important. However, we humbly submit that the average practitioner has the potential to harm many more persons — and waste many more resources — with widely recommended, but scientifically unjustified, preventive interventions, compared to treatments for active disease. This is simply because preventive guidelines tend to apply, for many years at a time, to the much larger number of well persons in the general population, compared to the rather small number of patients who are acutely ill at any one time.

To conclude, knowing how to tell useful from harmful or wasteful prevention is a core competency for both clinical and public health professionals; more should be done to ensure that they all acquire that competency.

Featured image credit: Photo by Jesse Oricho. CC0 public domain via Unsplash.

The post Disease prevention: helping health professionals appeared first on OUPblog.

What are the unexpected consequences of shorter work hours?

For many, work is increasingly interfering with their home life. Because of this, some countries are proposing shorter work weeks. But does this mean more productivity? Do shorter work weeks result in less work done? Social Forces Editor Arne L. Kalleberg caught up with Leah Ruppanner and David J. Maume to examine and discuss current debates arguing for shorter work hours and their latest research.

The findings suggest that directly legislating weekly work hours may have adverse and unexpected consequences. How might governments more effectively regulate hours worked, as we move towards a “24/7 global economy”?

The first question is whether legislating shorter work weeks actually results in a reduction of work. Or, are people feeling more compressed, strained, and vulnerable to work-to-family conflict. Existing research on implementing shorter work weeks (e.g. Sweden’s 6 hour day) suggest that employees are happier with their work lives and more productive.

Our study suggests that shorter work weeks may also make employees more sensitive to work-to-family conflict. We argue that this is the legacy of raising public consciousness about work-family issues. This should not dissuade governments from legislating shorter work weeks as other evidence indicates that it is associated with better employee outcomes. But, it does suggest that policy outcomes are complicated.

Are there any alternative legislative policies that appear to alleviate perceived work-family interference better than work hour regulations?

There is growing evidence that policy packages, rather than singular policies, are most effective in promoting a healthy workforce. The goal of governments should be to pair shorter work weeks with other resources. This may include expansive childcare provisions, sick and aged care provisions, and supplementing housework. This is a work-family problem and legislation should address both work and family demands, focusing on this problem holistically rather than focusing on one dimension exclusively.

Your findings present no significant gender differences in the effects of normative and legislated work hours on perceived work-family interference. Could you elaborate on the implications of these findings for countries where women still bear the majority of responsibility for childcare and other family matters?

We argue that this indicates a cultural shift in ideology in our sampled countries. We expected these effects to be highly gendered, with shorter work hours alleviating women’s work-to-family strain at higher rates than men’s. We would expect this to be especially the case for women in countries with highest domestic burdens. But, this was not what we found.

Rather, we found that all respondents (not just women, or mothers or parents) reported more work-to-family interference in countries with shorter work weeks. This suggests that there was a real ideological shift in how people viewed work and family in countries that legislated shorter work weeks. To explain this, we looked at trends from 1989 to 2005 and found that the percentage of respondents reporting preferences for less time at work increased in many countries over this time period. This suggests that a cultural shift for all workers rather than being isolated to one group.

Your findings show that collectivist societies report lower work-family interference despite longer work hours. Do you think this pattern can be explained by stronger multi-generational support systems among families in collectivist societies, or is this a matter of lower cultural awareness of work-time issues?

We cannot speak definitively to this claim as we did not empirically test these relationships. However, it seems reasonable that a combination of these processes is occurring simultaneously. It is also possible that these relationships can be explained by broader patterns of economic inequality, immigration, and domestic work. Specifically, employees in some of the long work hour countries hire in domestic (e.g. live-in) help to perform the domestic work. These processes are likely happening simultaneously and are clearly divided by class. Additional inquiry with appropriate data would test these arguments.

Workers in professional positions have high levels of resources but also highly permeable boundaries between work and family. This stress of higher status means professional workers are never off the clock.

Despite the fact that work hour regulations appear to have no significant effect on perceived work-family interference, does this type of legislation appear to have any other significant benefits for families and workers?

This is beyond the scope of this work. However, we are not arguing that shortening work weeks is negative for workers.

You suggest that changes due to the global financial crisis may have altered some of your present findings. Although the data are not yet available, do you have any intuition as to what sort of changes might be occurring?

We argue (and provide descriptive evidence) that this captures a cultural shift in changing ideologies – preferences for less time at work. However, the global financial crisis may have resulted in workers preferring more time at work because, in many countries, jobs are increasingly scarce.

However, this may not be the case as many citizens (in Europe in particular) challenged their governments’ move towards austerity. It is likely that shorter work hours are characteristics of countries with greater welfare provisions. If these provisions raise expectations, then the likelihood that citizens would “go back” seems highly unlikely. But, the GFC may have further polarized views about work by class with those who experience chronic unemployment or precarious work increasing their perceptions of work-centrality post GFC.

Telework and work-at-home are increasing in the United States. What impacts do you think these trends will have on the relationship between work hours and work-family interference?

I think the bigger question is about digital connectedness, because many professionals are expected to be available to work at all times, even those who are not telecommuting. Scott Schieman argues that workers in professional positions have high levels of resources but also highly permeable boundaries between work and family. This stress of higher status means professional workers are never off the clock. Pragmatically, this would increase work-to-family and family-to-work conflict as this is the definition of telework, blurring boundaries between work and family. However, questions about burn-out, stress, depression, and sleep associated with the 24/7 economy are perhaps more pressing, experienced by wider swaths of workers.

One of the surprising findings in your analysis is that there is no difference between families with and without kids in how average work hours in a country relates to work-family interference. Why might this be the case? Wouldn’t we expect a greater impact on families with kids?

This is about the direction of conflict. We expect workers with children to have more family-to-work conflict and, Matt Huffman and I confirm this. However, for questions of work-to-family conflict it is unclear why mothers should have more. In fact, we may expect childless men to have the highest tendency to bring work home with them. While some studies combine work-to-family and family-to-work conflict into a single measure of work-family conflict, we argue disaggregating these measures are important as these really are different experiences for men, women, mothers, and fathers.

Headline image credit: Laptop woman coffee breakfast by moleshko. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post What are the unexpected consequences of shorter work hours? appeared first on OUPblog.

Combatting antibiotic resistance

Antibiotic resistance continues to pose a major threat to public health. Wrong or incorrect use of antibiotics may cause bacteria to become resistant to future antibiotic treatments, leading to the growing problem of antimicrobial resistance in European hospitals and communities.

European Antibiotic Awareness Day is held on the 18 November each year and aims to promote research on finding new antibiotic drugs as well as encouraging prudent antibiotic use. To raise awareness of this threat, we have put together a reading list of chapters and articles from our medical books and journals, freely available to read until 18 February 2017.

“Antibiotic action – general principles” in OIDL Antibacterial Chemotherapy: Theory, Problems, and Practice by Sebastian Amyes

“Antibiotic action – general principles” in OIDL Antibacterial Chemotherapy: Theory, Problems, and Practice by Sebastian Amyes

“Strictly speaking, an antibiotic is an antimicrobial drug that is derived from natural products. Thus penicillin is a true antibiotic, whereas synthetic compounds such as sulphonamides and trimethoprim are not. However, there is general usage of the term to cover all systemic antibacterial drugs and thus the term antibiotic will be used in the modern sense.”

Designed to help medical trainees, general prescribers, healthcare workers, and students understand how antibiotics work, this article also helps to demonstrate where they might be most appropriate.

“Implementation of antimicrobial stewardship interventions recommended by national toolkits in primary and secondary healthcare sectors in England: TARGET and Start Smart Then Focus” in the Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy by D. Ashiru-Oredope, E. L. Budd, A. Bhattacharya, et al

This study aims to assess and compare the implementation of antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) interventions recommended by national AMS toolkits in English primary and secondary care settings, to determine the prevalence of cross-sector engagement to drive AMS interventions, and to propose next steps to improve implementation of AMS.

“Keeping it simple: lessons from the golden era of antibiotic discovery“ in FEMS Microbiology Letters by Dane Lyddiard, Graham L Jones, and Ben W Greatrex

As bacteria become increasingly resistant to current antibiotics, this article puts forward the question of whether we should return to the basics, such as simple, systematic screening of natural products against bacteria, in order to recreate the ‘golden era’ of antibiotics in the early 1900’s.

“Mechanisms of action and resistance to modern antibacterials, with a history of their development” in Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (7 ed.) by Peter Davey, Mark H Wilcox, William Irving, and Guy Thwaites

“Mechanisms of action and resistance to modern antibacterials, with a history of their development” in Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (7 ed.) by Peter Davey, Mark H Wilcox, William Irving, and Guy Thwaites

This article provides an introduction to the principles of antimicrobial chemotherapy, the problem of resistance and its control through policies, antimicrobial stewardship, and surveillance.

“Non-susceptibility of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., Pseudomonas spp., Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus in the UK: temporal trends in England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales” in the Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy by Rebecca Guy, Lourda Geoghegan, Maggie Heginbothom, et al

In 2013, the UK published a national five-year strategic plan to combat antimicrobial resistance. The main focuses of the plan included improving the surveillance of resistance, and focusing on better international collaboration. This study provides a geographical analysis showing the trends in antimicrobial resistance in each of the four countries in the UK as well as providing an update to the current data on pathogen trends in the UK.

“Pneumoccal meningitis: antibiotic options for restraint mechanisms” in Challenging Concepts in Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology:  Cases with Expert Commentary, edited by Amber Arnold and George Griffin

Cases with Expert Commentary, edited by Amber Arnold and George Griffin

Advances such as vaccination, introduced routinely for children and at-risk adults, has reduced the risk of invasive pneumococcal infections (including the reduction of some resistant strains) for both children and adults. However, antibiotic choices for resistant isolates continue to pose a challenge. This case study focuses on the treatment of 55-year old man with a presumed case of meningitis and the process of deciding which antibiotics to administer.

“The Innovative Medicines Initiative’s New Drugs for Bad Bugs programme: European public-private partnerships for the development of new strategies to tackle antibiotic resistance“ in the Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy by T. Kostyanev, M. J. M. Bonten, S. O’Brien, et al

Antibiotic resistance (ABR) is a global public health threat. Despite the emergence of highly resistant organisms and the huge medical need for new drugs, the development of antibacterials has slowed to an unacceptable level worldwide. To respond to this public health crisis, the Innovative Medicines Initiative Joint Undertaking programme has invested more than €660 million and this article describes the research initiatives launched to address the crisis.

“The international and national challenges faced in ensuing prudent use of antibiotics” in Antimicrobial Stewardship, edited by Matthew Laundy, Mark Gilchrist, and Laura Whitney

“The international and national challenges faced in ensuing prudent use of antibiotics” in Antimicrobial Stewardship, edited by Matthew Laundy, Mark Gilchrist, and Laura Whitney

The problem of antimicrobial-resistant organisms and untreatable infections is of global concern. The aim of antimicrobial stewardship is to control antimicrobial use in order to reduce the development of resistance, avoid the side effects associated with antimicrobial use, and optimize clinical outcomes. This chapter article and its associated book provides a very practical approach to antimicrobial stewardship: a ‘how to’ guide supported by a review of the available evidence.

“The ‘liaisons dangereuses’ between iron and antibiotics” by Benjamin Ezraty and Frédéric Barras, in FEMS Microbiology Reviews

This review brings together research in two fields – metals in biology and antibiotics – in the hope that collaboration between them will lead to advances in our understanding, and the development of new approaches to tackling microbial pathogens.

“Transferable resistance to colistin: a new but old threat” in the Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy by Stefan Schwarz and Alan P. Johnson Schwarz S, Johnson AP

Based on the widespread use of colistin in pigs and poultry in several countries and the higher number of mcr-1-carrying isolates of animal origin than of human origin, it is tempting to assume that this resistance may have emerged in the animal sector. Whatever its origin, interventions to reduce its further spread will require an integrated global one-health approach, comprising robust antibiotic stewardship to reduce unnecessary colistin use, improved infection prevention, and control and surveillance of colistin usage and resistance in both veterinary and human medicine.

“Understanding the culture of antimicrobial prescribing in agriculture: a qualitative study of UK pig veterinary surgeons” in the Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy by L. A. Coyne, S. M. Latham, N. J. Williams, et al

The use of antimicrobials in food-producing animals has been linked with the emergence of antimicrobial resistance in bacterial populations, with consequences for animal and public health. This study explored the underpinning drivers, motivators, and reasoning behind prescribing decisions made by veterinary surgeons working in the UK pig industry.

“Use your antibiotics wisely. Consequences to the intestinal microbiome” in FEMS Microbiology Letters by Jorge Cervantes

This article presents an analysis of recent literature on how the intestinal microbiome is altered by antibiotic therapy, including potential long term consequences of antibiotic therapy.

The FEMS journals have also curated a collection to mark Antibiotic Awareness Week 2016, which aims to raise awareness of the threat to public health of antibiotic resistance through increasing the knowledge available to health care professionals.

Featured image credit: Medications 2 by Joanna M. Foto. CC0 Public Domain via Freestocks.org.

The post Combatting antibiotic resistance appeared first on OUPblog.

Trump: An (im)probable victory

As Americans adjust to the idea of President Donald Trump, many are looking at the electoral process to ask how this result came about. The 2016 American presidential election has been characterized as like none other in the nation’s history. In some senses the election was unique; for instance, Donald Trump will be the first President to assume office without ever having held a public office or having served in the military. His style is like none other in the modern era, with historians claiming that Andrew Jackson’s election of 1828 was the only close parallel to a President thumbing his nose at conventional mores and manners. But in other ways, the election of 2016 repeats some themes that are common in the American electoral process.

First, let’s review the results. Donald Trump won an improbable victory over Hillary Clinton, defying the predictions of virtually every political pundit. He won a clear majority in the Electoral College. The final result will probably be 306-232 in the Electoral College, though some recounts remain possible. Secretary Clinton, however, won a plurality of the popular vote, leading Mr. Trump by approximately 400,000 votes out of more than 120,000,000 cast, approximately 0.2%. This election marked the fifth in American history—and the second in the last five presidential elections—in which the popular vote winner lost the election. The Electoral College gives more power to smaller states than larger states, and it gives more relative power to voters in states with competitive results than it does to those in states dominated by one party. To illustrate, Mr. Trump won Wisconsin by 30,000 votes, while Secretary Clinton won Maryland by 400,000 votes; yet each won 10 Electoral Votes, which are determined by the size of the states’ congressional delegations, not their vote total.

While Democrats picked up two seats in the United States Senate and about 10 (some races are still under recount) in the House of Representatives, the Republicans remain in solid control of both chambers of the legislature. Early expectations are that they will push through proposals by President-elect Trump with which they agree, e.g. repealing or at least fundamentally reforming the Affordable Care Act, while they may spend more time finding a common position on other items, e.g. tax reform.

Like most American elections, this one was determined in the so-called swing or battleground states, the roughly ten to fifteen states that are most hotly contested. Like most American elections in recent years, citizens tended to vote along party lines. Mr. Trump received 90% of the votes of Republican citizens; Secretary Clinton, 89% of the votes of the Democrats. Most citizens supported congressional candidates of their party. All of this follows the familiar pattern.

Why then the surprise? What was different? When political scientists predicted the result of this election before the nominees were known last April, using familiar models based on the state of the economy and presidential popularity, they predicted that the Republican candidate would win. Americans tend not to elect the candidate of the party of an incumbent President, unless the economy is robust and citizens are optimistic. But then Mr. Trump was nominated—and these same political scientists changed their predictions. How could the citizens vote for someone who was saying and doing things so out of line with the norm?

Donald Trump, thumbs up by Transition 2017.CC-BY-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Donald Trump, thumbs up by Transition 2017.CC-BY-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The answer is that they could. They could because the driving force in the vote was a desire for change, a desire expressed most strongly by white, non-college-educated voters (males more than females, but women as well) who have felt that the government has not been paying attention to them. These are the voters whose jobs have been compromised by NAFTA; these are the voters who see that the Democratic Party seems to care more for African-Americans, Hispanics, and immigrants than for them. They were mad; Mr. Trump spoke to their anger. And they supported him.

At the same time, the voters who had twice elected President Obama did support Secretary Clinton, but not as strongly. She won the African-American vote, but by 5% less than he did. She won the Hispanic vote, but by 3% less than he did. Neither of these groups turned out in as large numbers as they had four and eight years ago. Secretary Clinton won the women’s vote, but only by 1% more than President Obama had. In short, those groups supporting her did not vote as strongly for her, nor did they turn out in as great numbers, as did the groups supporting Mr. Trump.

What does this mean for the future? Frankly it is too early to tell. If Mr. Trump governs as he ran for office, the United States may be in for a rough ride—and many citizens fear that. But if he moderates his tone, acts presidential, works with respected leaders in Congress, we may be in for a period of changing policies, but not fundamental changes in how we are governed.

One final thought: Secretary Clinton demonstrated the strength of American democracy for all of the nation and the world to see in her concession speech on 9 November. She acknowledged disappointment but stated that she would support President-elect Trump, and called on her supporters to wish him luck and hope for his success. That acceptance of the result of an election—even an unexpected loss in which the popular vote winner did not emerge with the prize—demonstrates a recognition of the importance of our process, a recognition that gave legitimacy to American elections in 1800 and has continued to do so every four years since.

Featured image credit: American Flag by Etereuti. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Trump: An (im)probable victory appeared first on OUPblog.

November 17, 2016

Brain network of psychopathic criminals functions differently

Many criminal offenders display psychopathic traits, such as antisocial and impulsive behaviour. And yet some individuals with psychopathic traits do not commit offences for which they are convicted. As with any other form of behaviour, psychopathic behaviour has a neurobiological basis. To find out whether the way a psychopath’s brain is functionally, visibly different from that of non-criminal controls with and without psychopathic traits, we talked to Dirk Geurts and Robbert-Jan Verkes: researchers from the Donders Institute, the Department of Psychiatry at the Radboud University Medical Centre.

How are the brains of people with psychopathic traits different from those without psychopathic traits?

Dirk Geurts: We carried out tests on 14 convicted psychopathic individuals (all patients at the Pompe Clinic for Forensic Psychiatry), and 20 non-criminal individuals, half of whom had a high score on the psychopathy scale. The participants performed tests while their brain activity was measured in an MRI scanner. We saw that the reward centre in the brains of people with many psychopathic traits (both criminal and non-criminal) were more strongly activated than those in people without psychopathic traits. It has already been proved that the brains of non-criminal individuals with psychopathic traits are triggered by the expectation of reward. This research shows that this is also the case for criminal individuals with psychopathic traits.

Among those with psychopathic traits, were there any differences observed between non-criminals and criminals?

Afghan National Police with handcuff training by NATO Training Mission-Afghanistan. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Afghan National Police with handcuff training by NATO Training Mission-Afghanistan. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Dirk Geurts: Another interesting difference was discovered between non-criminal people with multiple psychopathic traits and criminal people with psychopathic traits. There is a difference in the communication between the reward centre and an area in the middle of the forebrain. Good communication between these areas would appear to be a condition for self-control. Our results seem to indicate that the tendency to commit an offence arises from a combination of a strong focus on reward and a lack of self-control. This is the first research project in which convicted criminals were actually examined in this way.

Are there any potential traits or predictors of criminal behavior?

Robbert-Jan Verkes: Psychopathy consists of several elements. On the one hand, there is a lack of empathy and emotional involvement. On the other hand, we see impulsive and seriously antisocial, egocentric behaviour. Especially the latter character traits seem to be connected with an excessively sensitive reward centre. The presence of these impulsive and antisocial traits predicts criminal behaviour more accurately than a lack of empathy. The next relevant question would be: what causes these brain abnormalities? It is probably partly hereditary, but abuse and severe stress during formative years also play a significant role. Follow-up studies will provide more information.

Should there be brain scans in courtrooms?

Robbert-Jan Verkes: So what do these findings mean for the free will? If the brain plays such an important role, to what extent can an individual be held responsible for his/her crimes? Will we be seeing brain scans in the courtroom? For the time being, these findings are only important at group level as they concern variations within the range of normal results. Of course if we can refine these and other types of examinations, we may well see brain scans being used in forensic psychiatric examinations of diminished responsibility in the future.

Featured image credit: Brain by sbtlneet. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Brain network of psychopathic criminals functions differently appeared first on OUPblog.

What does research say about electronic cigarettes?

To mark the Great American Smokeout, a day where smokers across the country – with support from family and friends – take steps to quit the habit, we got in touch with the Editor-in-Chief of Nicotine & Tobacco Research, published on behalf of the Society for Research on Nicotine & Tobacco, to learn more about the potential pros and cons of electronic cigarettes.

Scientific journals are more than simply vehicles for the dissemination of the latest research; they also provide an overview of the state of a field and the breadth of opinions about certain topics, as well as a forum for debate and disagreement (in the form of letters, commentaries, and editorials). In my opinion, as a journal editor, it is important to provide fair and balanced coverage, rather than preferring articles that reach one conclusion over another. In practice, though, this can be challenging.

A good example of this is electronic cigarette (e-cigarette) research. E-cigarettes heat liquid that usually (but not always) contains nicotine, and the aerosol generated (usually called “vapour”) is inhaled to deliver nicotine to the lungs. These devices have grown dramatically in popularity in recent years, and the research community is working hard to understand the epidemiology of their use, particularly their potential benefits and harms.

If e-cigarettes help people to stop smoking, and relatively few young people who would not have otherwise started smoking start using them, then they are likely to offer a substantial public health benefit. The adverse health consequences of smoking (such as the increased risk of cardiovascular disease and a range of cancers) are so great that anything that reduces smoking will improve public health.

On the other hand, if e-cigarettes don’t help people stop smoking, carry greater long-term harms than anticipated, or act as a route into smoking for young people who would not otherwise have smoked, they may be detrimental to public health. For example, although propylene glycol is regarded as a safe food product, the impact of long-term inhalation is unknown and unlikely to be entirely benign.

An example of a commercial e-liquid and an advanced personal vaporizer. Photo by AesirVanirJotnar. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

An example of a commercial e-liquid and an advanced personal vaporizer. Photo by AesirVanirJotnar. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.What is unfortunate is that tobacco researchers are now deeply divided over this issue, with researchers who previously worked closely towards reducing the harms of tobacco use now holding highly polarized opinions. The challenge as a journal editor is to reflect this plurality of opinions, whatever one’s personal opinion is. One way to achieve this is to include commentaries, key articles, and responses to those commentaries. This provides readers with a sense of the ongoing debate.

A recent article illustrates this well. David Levy and colleagues at Georgetown University Medical Center have published an analysis looking into the likelihood of individuals influenced by e-cigarettes to start smoking cigarettes; they refuted this hypothesis and have suggested that e-cigarettes are likely to have a positive public health impact and highlighted the information we need to collect to monitor this. In response, two groups published commentaries highlighting what they perceived to be shortcoming of this analysis, to which Levy and colleagues responded. The disagreement turns on how best to model e-cigarette trends in the population, and in particular, how to distinguish between those who have experimented a few times with e-cigarettes and those who become regular users.

Another question is how to model the rapidly changing e-cigarette landscape, where the relationship between experimentation and regular e-cigarette use may differ across different age cohorts. These are complex questions, and the subject of considerable ongoing debate within the research community. Highlighting this debate in the pages of academic journals is an important way of engaging the wider community.

We live in an era where social media and a variety of platforms offer opportunities for post-publication peer review. I think this is a positive development that allows for more rapid and democratic critique of published research. Nevertheless, I still see an important place for more formal, peer-reviewed commentary and response in the pages of a scientific journal not only to capture ongoing debate but also to highlight that while scientists often agree on much, they typically disagree on just as much.

Featured image credit: E cigarette by Horwin. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post What does research say about electronic cigarettes? appeared first on OUPblog.

When white men rule the world

If Hillary Rodham Clinton had triumphed in Tuesday’s presidential election, it would have been a milestone for women’s political representation: a shattering of the hardest glass ceiling, as her supporters liked to say. Clinton’s defeat in the electoral college (but not the popular vote) is also the failure of a certain feminist stratagem: the cultivation of a highly qualified, centrist, establishment (and comparatively hawkish) female candidate, measured in speech and reassuringly moderate in her politics. But the victory of Donald Trump tells us just as much about the global politics of gender, and how it is being remade.

The election itself was predicted to be the most divided by sex in US history. Polls from a few weeks before the election had Clinton’s lead among women at the highest level for a presidential candidate since records began in 1952. A widely shared meme celebrated the trend and declared that “women’s suffrage is saving the world”. Activists from the alt-right trolled in response that the 19th amendment should be repealed. Time called the election a ‘referendum on gender’; The New Yorker a question of ‘manifest misogyny.’

In the end, the politics of race mediated the politics of gender: white women were by many leagues more comfortable with Trump’s candidacy than women of colour. As Kimberlé Crenshaw pointed out on Wednesday morning, the claim for a singular female worldview that could be mobilised to ordain Clinton ‘Madame President’ collapses under the pressure of other cross-cutting histories, interests, and ideologies. NBC exit polls reported a 10% lead for Trump among white women, and an almost 20% lead amongst white women between the ages of 45 and 64. By contrast, CNN data indicated that 94% of black women voted for Clinton. Opinions now vary on how much blame to apportion suburban white women, or what have been called ‘Ivanka voters.’

And yet the power of race and racism in deciding the election should not be taken to mean that gender is irrelevant after all. As predicted, white men voted for Trump in the greatest numbers. And although the collapse in the predicted female vote for Clinton is surprising, it is at the same time no novelty to observe that women may also disqualify a politician on the basis of her sex — for example, in setting higher standards for female than male candidates, in believing that only men are aggressive enough for politics, or in judging women more harshly on their appearance and demeanour.

Instead of seeing gender as simply subordinate to ethnopolitics, we may instead ask how different versions of masculinity and femininity are deployed in the creation of political community. If the representative Trump voter is reacting to a sense of decay in the American system — defined variously as excessive ‘political correctness’; a condescending cultural elite; the decline of the US economy; the presence, success, and sometimes mere existence of immigrant and minority ethnic communities; and the weakening of evangelical and fundamentalist Christian morals as enforced by government — then their preferred solution is to resuscitate a highly masculine version of American power.

Donald Trump speaking at CPAC 2011 in Washington, D.C. by Gage Skidmore. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

Donald Trump speaking at CPAC 2011 in Washington, D.C. by Gage Skidmore. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.This projected return to ‘greatness’ — which allocates a special place to security measures to be taken against foreign and otherwise ‘un-American’ bodies — is also thoroughly white, as is indicated by alt-right renderings of Trump as a Spartan king (borrowing from Frank Miller’s graphic novel 300 and the later film, both of which contrasted the whiteness of the heroic Greeks with the exaggerated blackness of Persian invaders). No mystery is posed by the endorsement of the Ku Klux Klan in this regard. And Trump’s infamous reference to Mexican rapists further reveals how the immigrant invader is already presumed male. To experience the loss of American greatness is to be emasculated; to achieve its return is to reassert privilege, status, and exceptionalism (liberals are exceptionalists too, if in a less crudely masculine fashion).

And yet in this act of reassertion gender itself functions in complex ways. As Jenny Mathers points out, many of the traits celebrated in Trump — impulsiveness, over-sensitivity, emotionality — are traditionally coded as feminine, while voters’ collective immunity to Trump’s gaffes and insults can in turn be read as the rejection of a mode of leadership — logical, calculating, authoritative — usually attributed to men, and which Hillary Clinton spent decades working to inhabit in conformity with the expectations for properly ‘presidential’ behaviour.

One explanation for Trump’s support amongst suburban and affluent women might indeed be his defence of a parochial sense of ‘home.’ Home not just in the sense of traditional domesticity, with basically heterosexual arrangements and women as stay-at-home mothers (as Trump voters prefer), but also in the adoption of isolationist foreign policy, and in his campaign-defining promise to build a wall to protect the ‘domestic’ space of the nation. Homeland security, in other words, is analogical to the safety of the family in its household. Trump’s electoral coalition represents a major reconfiguration of ideas about the body politic, and the reassertion of a nationalist idea of greatness that liberals had hoped dead, in which the terms of gender as well as race and political economy announce a kind of updated, authoritarian 1950s: stable and well-paid middle class jobs, in ethnically homogeneous and white Christian communities, but without full reproductive rights, trans bathrooms, trigger warnings or equal gender representation in political, military, economic and cultural life.

However divided the country, this is the posture that now commands the right to rule, within the republic and beyond it. Far from only elevating white men, this ideological configuration will also, as Jacqui True and Aida Hozić have argued, have to strike a new patriarchal bargain with its female supporters. It may, for example, lead to a settlement that accommodates some women’s economic self-interest, but which also further legitimises the entitled attitudes of ‘toxic masculinity.’ To the extent that a Trump presidency seeks to push back against the dislocating tendencies of globalisation (themselves gendered — just think of the feminisation of irregular labour), it will also be forced to navigate between a distinctly un-Republican policy of government support (the matriarchal ‘nanny’ state) and a more conventional escalation of military spending (to reassert America’s masculine prowess, as has been promised). Militarism itself can accommodate ‘the woman question’ by taking on the mantle of protector, reinforcing patriarchal authority as a solution to women’s vulnerability. Such an ideological thread will be most easily constructed not as a response to rape culture within the United States, but on the designation of foreign others as smugglers of an alien gender ideology and/or as rapists-in-waiting.

The ramifications of a Trump presidency will obviously be global. In the meantime, gender will shape multiple domains of world politics just as it always has. The spectacle of the election has concentrated minds on the politics of gender, framed as kind of battle of the sexes, but it operates far in excess of that frenzy. Politics as currently constituted is indeed everywhere a referendum on gender, not as a master conflict but articulated with, atop and sometimes inside other global contests of power and freedom.

Featured image credit: Donald Trump speaking with supporters at a campaign rally at the Phoenix Convention Center in Phoenix, Arizona by Gage Skidmore. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post When white men rule the world appeared first on OUPblog.

Introducing Elanor from the sheet music marketing team

We are delighted to introduce Elanor Caunt who joined OUP’s sheet music marketing department in September 2016 and is based in the Oxford offices. We sat down to talk to her about what a typical day marketing sheet music looks like, what life on a desert island should involve, and the ‘interesting’ wildlife of Oxford.

When did you start working at OUP?

I joined the OUP sheet music department as Marketing Manager at the start of September 2016. This was not my first foray into the world of OUP, because I also spent some time working with OUP’s English Language Teaching (ELT) Division in 2015/16.

What is your typical day like at OUP?

A typical day always starts with a cup of tea and a quick email check. Then it might include attending a meeting about social media, writing the copy for an advert, putting together a marketing plan for a new publication, briefing a designer on a flier and updating the budget with the latest figures. I always try to fit lunch in and can’t work late due to family commitments, so I am usually pretty focused when I am at my desk.

Elanor, herself

Elanor, herselfWhat’s the most enjoyable part of your day?

Something I always enjoy is my walk to work every morning along a nice stretch of the Oxford canal. Whatever the time of year, it’s always peaceful. The canal boats change every day and you see all kinds of wildlife – squirrels, ducks, geese, swans, birds. It’s a good time to think.

What is the strangest thing currently on or in your desk?

Probably my large bottle of intensive skin moisturiser. Is it marshmallow? Is it jelly? Is it foam? People just really aren’t sure what to make of it, but it makes a great noise when you shake it around in the bottle…

What was your first job in publishing?

My first publishing job many moons ago was with the Institute of Chartered Secretaries & Administrators (ICSA) in London. I loved the wide variety of tasks I got to work on, and learnt a lot about the real practicalities of publishing.

If you didn’t work in publishing, what would you be doing?

Probably working in the music industry somewhere, somehow. After completing a music degree, my first job was working in the box office of the Wigmore Hall in London, which was an absolutely wonderful environment full of talented people. It was a hard decision to leave to complete my publishing diploma although I don’t really have any regrets.

If you could trade places with any one person for a week, who would it be and why?

I think I often fail to really appreciate the good things I have in life. So I would probably want to trade places with someone that would help me learn how to be more grateful for these.

If you were stranded on a desert island, what three items would you take with you?

If I am allowed people, I would take my little boy, but I doubt that is allowed. So in that case I would say… a lifetime supply of teabags, a large mug and a cow (for the milk, obviously). A cup of tea solves (almost) all things in my world.

What drew you to work for OUP in the first place?

I was drawn to work for OUP because the mission and purpose of the organisation fits nicely with my own view that education and learning has the infinite capacity to change the world for the better.

What is your favourite word?

Interesting… I sometimes use this word to buy me thinking time when I can’t work out how to respond immediately; someone would need to know me very well to tell whether I am genuinely interested in what they are saying or not.

Featured image: Piano keys and manuscript. CC0 via Pixabay.

The post Introducing Elanor from the sheet music marketing team appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers