Oxford University Press's Blog, page 440

November 17, 2016

How many famous philosophy quotes do you know? [quiz]

This November, the OUP Philosophy team celebrates UNESCO’s World Philosophy Day! We’ve highlighted a selection of some of our most popular philosophy research across various disciplines, and created a quiz to test your knowledge of some of the world’s best known thinkers. Can you tell the difference between a Bertrand Russell quote and a quote by Mary Wollstonecraft? Match the quotes below to the correct philosopher and find out!

Quiz image: The Radcliffe Camera in Oxford, England as viewed from the tower of the Church of St Mary the Virgin. Photo by DAVID ILIFF. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image: Rodin’s “The Thinker” in the Rodin Museum in Paris. Public domain via Flickr.

The post How many famous philosophy quotes do you know? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

November 16, 2016

2016 US presidential election reading list

Following the recent US Presidential election, we have curated a reading list with resources that provide insight into the politics behind the 2016 election, and look at the key topics that stimulated some of the major debates from the election season. We have selected books and other resources that detail American politics in the context of this election and investigate the issues that influenced the campaigns.

Elections and Electoral Politics

We explore content that relates to American political parties, voting history in the US, and election trends:

American Political Parties and Elections, by L. Sandy Maisel

Toward Democracy, by James T. Kloppenberg

Cosmic Constitutional Theory, by J. Harvie Wilkinson, III

Ballot Battles, by Edward Foley

The Inevitable Party, by Seth Masket

“The Decision to Vote or Abstain”, by Elisabeth Gidengil

“Election Forecasting”, by Mary Stegmaier and Helmut Norpoth

“How to Increase Participation”, from The Politics of Voter Suppression by Tova Andrea Wang

Labor, Activism and Organizing

These titles grapple with topics including issues with democracy, activist groups, and organized political movements:

Democracy against Itself , by Daniel DiSalvo

No Shortcuts , by Jane F. McAlevey

How Organizations Develop Activists , by Hahrie Han

Rich People’s Movements , by Isaac Martin

Populism’s Power , by Laura Grattan

News Media and Social Media

Digital media has a powerful influence on elections and campaigns. Investigate the relationship between campaigns and the internet, how civic involvement has changed, and the effect media have on voting and identity:

Analytic Activism , by David Karpf

Prototype Politics , by Daniel Kriess

Using Technology, Building Democracy , by Jessica Baldwin-Philippi

The Civic Organization and the Digital Citizen , by Chris Wells

Expect Us , by Jessica Beyer

Presidential Campaigning in the Internet Age , by Jennifer Stromer-Galley

Tweeting to Power , by Jason Gainous and Kevin M. Wagner

The Hybrid Media System , by Andrew Chadwick

Affective Publics , by Zizi Papacharissi

The Outrage Industry , by Jeffrey M. Berry and Sarah Sobieraj

Disruptive Power , by Taylor Owen

The News Media , by C.W. Anderson, Leonard Downie, and Michael Schudson

American Politics

Here are titles dedicated to American politics specifically, from American political parties to the recent transformations in American democracy:

Four Crises of American Democrac y, by Alasdair Roberts

“Party Movements”, by Mildred A. Schwartz

Building a Business of Politics , by Adam Sheingate

The Business of America is Lobbying , by Lee Drutman

Voter Behavior and Public Opinion

Are voters generally uninformed? What factors influence our decisions when voting? These titles deal with questions relating to voting influences on the individual and questions where to go from here:

Uninformed , by Arthur Lupia

The Fat Tail , by Ian Bremmer

Honor Bound , by Ryan P. Brown

Running from Office , by Jennifer L. Lawless and Richard L. Fox

We Are the Ones We Have Been Waiting For , by Peter Levine

“The Ideological Pull of Siblings” from Families’ Values by R. Urbatsch

Voter Demographics

What are voting trends and how are they formed? Below are titles that investigate group identities throughout America and how voting is impacted:

The New Minority , by Justin Gest

Dog Whistle Politics , by Ian Haney López

Social Democratic America , by Lane Kenworthy

Asymmetric Politics , by Matt Grossmann and David A. Hopkins

Altered States , by Thomas M. Holbrook

Boom, Bust, Exodus , by Chad Broughton

Coming Up Short , by Jennifer M. Silva

Featured image credit: President Obama, by The White House. CC US Government Works via Flickr.

The post 2016 US presidential election reading list appeared first on OUPblog.

Coming out of the fog

This is a postscript to last week’s post on fog. To get my point across, as they say, let me begin with a few short remarks on word origins, according to the picture emerging from our best dictionaries. My remarks pertain to Indo-European. We are told that once upon a time many roots existed, for example, digh-, ger-, and the like. They were allegedly endowed with certain meanings. Thus, digh– meant “nanny goat.” By contrast, there were presumably six different ger’s: “to gather,” “to grow old,” “curving, crooked,” “to cry hoarsely,” and “to awaken.” Those roots were abstracted from the words in various languages that are obviously or supposedly (sic) related. The units in question can be even shorter: for instance, leu– is said to coexist with its “extended” offspring or cousins leud-, leug-, leuk-, and leup-, among others. At some time, etymologists seem to have believed that such roots floated around before words. I think Skeat, if I understand him correctly, held this view. The problem with it is that, except perhaps digh, the complexes ger-, leu-, and so forth have never been attested as separate words, unlike, for instance, Engl. work vis-à-vis worker, workman, workable, and the forms works, worked, and working. Therefore, the status of the reconstructed Indo-European roots, as I presented them above, remains unclear.

A root presupposes a tree, doesn’t it?

A root presupposes a tree, doesn’t it?Those who have followed this blog for some time may remember my conclusions about the origin of the words bed, bad, and dog, among others. The complexes I set up resemble ger-, leud-, and their kin, but they were real words with equally real variants. For instance, when we discover (in English) the complex big, we can expect the existence of pig, pug, bug, bog, bag, and pod, with vague reference to “swollen.” None of them has to be older than another, whatever the date of their attestation in texts (though, of course, they are not contemporaneous), and whether they really belong together is open to discussion. Researchers have only two fears: to be the first in launching a great discovery (because if in so many years a brilliant conjecture has not occurred to anyone else, it is probably wrong) and not to be the first (for fear of making a lot of noise and being told that one’s pet idea was put forward quite some time ago and has already been refuted). I am hastening to say that doubts about reconstructed Indo-European roots are more than a hundred years old and that the existence of roots like big ~ bug ~ bag ~ pig ~ pug—not only in Indo-European but in all languages—has also been suspected for more than a century, especially by those who work with onomatopoeia (sound imitation), sound symbolism, and baby language. The danger is to let the idea that all words are either imitative or symbolic run away with an enthusiastic linguist.

Indo-European roots make sense only if there are several similar words in several languages. But bed, bad, dog, and, let us say, fog are partly isolated. An obscure cognate in a Low German dialect or Middle Dutch does not go too far. Bed has ancient cognates elsewhere in Germanic, but all of them mean the same (“bed”). Fog is possibly a borrowing from Scandinavian. The existence of the sound complex fok-, fuk-, and so on designating blowing does not look like an over-bold hypothesis. With regard to Engl. fog, the story, we sometimes hear, began with fog “grass” and the adjective foggy “damp.” According to this etymology, fog is a so-called back formation from foggy, but there is no evidence for this way of development.

Last week, I wrote about an association of fog ~ feg ~ fug with dampness and moisture, but cited no examples of fug. The words that follow are from The English Dialect Dictionary by Joseph Wright: fug and its synonym fogo “a strong smell,” fuggy “stuffy, closed,” foggy1 “stupid, muddled; half-tipsy,” foggy2 “fat, corpulent” (foggy2 was already known to Randle Cotgrave, the author of A Dictionary of the French and English Tongue, 1611), and fogey “passionate.” They look like being more or less related to the idea of fog. Some are closer to fog (“a strong smell,” “stuffy, “fat”), the others are perhaps the figurative meanings of the same (“stupid,” “passionate”). But there is no certainty. Fogey “passionate” may belong to an entirely different group. Since the verb fog “cover with fog” is known in Standard English, the metaphorical meaning “to puzzle, bewilder” sounds quite natural (Wright included to fog off: of plants “to damp off”; cf. foggy “dewy”). Some such coinages hint (but no more than hint) at the existence of the meaning of fug– “mist,” for example, fugle “a term to which an indefinite meaning is allotted, and which is applied under the circumstances where manners or actions are in any way objectionable”; thus, a word belonging, from a semantic point of view, with gizmo with thingamajig. Again we cannot be sure that we have not gone too far afield. Fag ~ fug has been recorded as “a term used by boys in playing; first in order,” and, surely, no connection with fog can be made out here. I needed this digression because there may be a path, however tortuous, from fog to fogey, pettifogger, and the F-word.

Here is a picture of fug or fogo.

Here is a picture of fug or fogo.Fogy (or fogey), usually an old fogey, a late eighteenth-century coinage (or borrowing?), if we can trust our records, seems to have originated as a derisive term for an invalid or garrison soldier. The word is and has always been insulting. Comparison with fugle, a word that means nothing, and foggy “stupid” may suggest a remote tie between them and fogey. At first sight, an association of fogey with disabled soldiers makes such ideas unappealing, but there is a strong cruel tradition going back to at least the days of Ancient Rome to mock the infirm, including veterans. We can perhaps say that, if the word is of dialectal origin, the fog- ~ fug environment contributed to its meaning, but we don’t know even that much.

Those who are interested in the origin of the English F-word will find all the information they need (and much more) in An Analytic Dictionary of English Etymology: An Introduction (2008). The initial meaning of very many f-k ~ f-g, f-d, and f-b words is “move back and forth.” Along with fidget, one finds many formations like fig about, fig (an obscene gesture), fiddle–faddle, fuddle, and fogger “hustler.” Pettifogger must be simply petty fogger. If we return to the beginning of our journey, that is, fog “dampness” and remember Icelandic fjúka “to be driven by the wind,” we may agree that the idea of the verb to fog is not wholly incompatible with the idea of movement (back and forth), fidgeting, fiddling, and the rest.

She failed a math exam. Here is the aftermath.

She failed a math exam. Here is the aftermath.The words discussed above form an extremely loose group in which the idea of cognates is almost irrelevant. Therefore, I am able to make only a most cautious suggestion. It seems that fog is a syllable (a root, if a more solid term is required) that could be used for denoting many things with the sense “movement back and forth.” Figurative meanings developed in several ways and can usually be reconstructed. It is hard to wade through a swamp. My goal was to point to what seems to be such a swamp, with fog “thick mist” growing in it like a single piece of grass, also called fog. I can only hope that the aftermath of my cautious essays will result in a better understanding of the origin of fog.

Image credits: (1) Ecuador, Virgin Forest by Albert Dezetter, Public Domain via Pixabay. (2) “bad smell” by Jeremy Tarling, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr. (3) Book, bored by PublicDomainPictures, Public Domain via Pixabay. Featured image: “Patio del palacio de Los Inválidos, París” by Alonso de Mendoza, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Coming out of the fog appeared first on OUPblog.

What is a good job?

Most people would say a good job is one that comes with a nice paycheck, reasonable hours, a healthy and safe work environment, and benefits such as social insurance. While this profile makes a lot of sense from an individual perspective, it does not necessarily tell policy-makers what the priorities should be for their national jobs strategies. Those priorities should be jobs that add the most social value – that contribute most to a country’s economic and social development. These “good jobs for development” may look like the jobs profiled above. But in some cases, a good job for the individual may not be good for the development of society. Think about some of the well-paying but redundant jobs in government or a protected sector, or in activities that contribute to environmental damage.

Defining a good job for development depends on the context of the country and the development challenges it faces. Take the case of societies with large youth bulges and high levels of youth unemployment. Tunisia and several other countries in the Middle East and North Africa fit this description. The price of this youth unemployment has obviously been high in both economic and social terms, and it is hard to imagine anything that would benefit these countries more than suitable jobs for these young people. These are certainly good jobs for development in this context.

Or think about poor countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, like Mozambique, where subsistence agriculture still dominates the economy, and poverty reduction is the number one challenge. Good jobs in such settings are those that enable farmers to access technology and markets that will increase their productivity and incomes. Or they may be non-farming jobs elsewhere on the value chain in agriculture, or low-skilled jobs in urban sectors that will trigger structural upgrading in the economy.

Good jobs that drive development look very different still in other contexts. For example, resource-rich economies can generate a lot of wealth but need to use this wealth wisely to achieve inclusive growth. Too few countries with abundant resources have been successful in doing this. But for Papua New Guinea, and many other resource-rich developing countries, investing some of the resource revenues in jobs in education and health would result in the creation of good jobs of a sort that would contribute to sustainable development.

A farmer at work by Neil Palmer. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

A farmer at work by Neil Palmer. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.To take another example, small-island nations, such as St Lucia, need to overcome obstacles related to remoteness and scale, so jobs that strengthen connections with large offshore markets will have positive development spillovers. Other countries face specific challenges of very different natures, such as dealing with conflict, rapid urbanization, or population aging. Jobs that will contribute to development in these settings will look very different as a result.

But sometimes our conventional notion of a good job is appropriate, not only from an individual perspective but from a societal one as well. Mexico offers a good example. There, and in other emerging economies that face the challenges of formalization, people are seeking the voice, benefits, and social protection that describe the vast majority of jobs in advanced, high-income economies. The creation of jobs with these features will benefit those who hold them, but it will also have positive spillovers for society through the reduction of labor market and social policy dualism, and through the economic gains that will result from improved social risk management.

As we can see, good jobs can vary hugely depending on the country. But as these cases underline, this is only the first step in designing a jobs strategy that drives development. The next is to address the constraints that are getting in the way of the creation of enough good jobs for development, and then to alleviate these constraints through policy actions.

Economic growth is fundamental in almost any setting, and in some cases, the best job strategy is simply a growth strategy. But in other situations, the best job strategy may involve actions that move well beyond conventional approaches. To take the high youth unemployment example of Tunisia, the solution lies not with more growth or better education, but with governance reforms and more competitive product markets that open up opportunities for the young. Job strategies in agrarian societies like Mozambique should include sector policies in agriculture that raise productivity and basic education to prepare workers for jobs in other sectors. Job strategies in other contexts may involve the management of sovereign wealth funds, migration, social protection policies, urban policy, and gender policy, and so on.

In the end, jobs deserve to be more central in our thinking about economic and social development. It is through jobs that households improve their living standards, that workers and firms become more productive, and that people gain much of their identity. And it is through the creation of good jobs in a particular country context that important social and economic spillovers occur.

Featured image credit: Workbench by m0851. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post What is a good job? appeared first on OUPblog.

Word of the Year 2016 is… post-truth

After much discussion, debate, and research, the Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year 2016 is post-truth – an adjective defined as ‘relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.’

Why was this chosen?

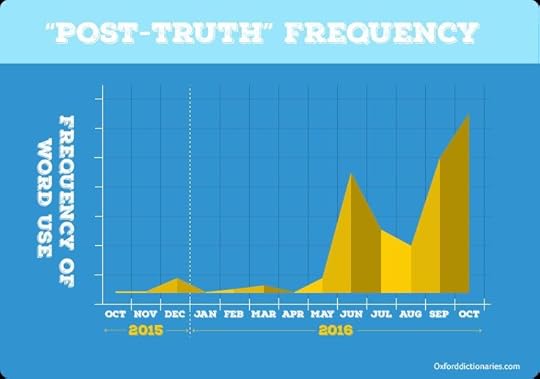

The concept of post-truth has been in existence for the past decade, but Oxford Dictionaries has seen a spike in frequency this year in the context of the EU referendum in the United Kingdom and the presidential election in the United States. It has also become associated with a particular noun, in the phrase post-truth politics.

Post-truth in 2016

Post-truth has gone from being a peripheral term to being a mainstay in political commentary, now often being used by major publications without the need for clarification or definition in their headlines.

Obama founded ISIS. George Bush was behind 9/11. Welcome to post-truth politics https://t.co/QYrx76krF0

— The Economist (@TheEconomist) November 1, 2016

Donald Trump understands a basic tenet of for-profit media: the only “truth” is that you can’t be boring https://t.co/r6BNhEhpRx

— The Wire (@thewire_in) November 1, 2016

How the “post-truth” election has put a strain on the world’s fact-checkers https://t.co/H7YDMss6Vc pic.twitter.com/xKwxLzF1PV

— VICE News (@vicenews) October 24, 2016

The term has moved from being relatively new to being widely understood in the course of a year – demonstrating its impact on the national and international consciousness. The concept of post-truth has been simmering for the past decade, but Oxford shows the word spiking in frequency this year in the context of the Brexit referendum in the UK and the presidential election in the US, and becoming associated overwhelmingly with a particular noun, in the phrase post-truth politics.

A brief history of post-truth

The compound word post-truth exemplifies an expansion in the meaning of the prefix post- that has become increasingly prominent in recent years. Rather than simply referring to the time after a specified situation or event – as in post-war or post-match – the prefix in post-truthhas a meaning more like ‘belonging to a time in which the specified concept has become unimportant or irrelevant’. This nuance seems to have originated in the mid-20th century, in formations such as post-national (1945) and post-racial (1971).

Post-truth seems to have been first used in this meaning in a 1992 essay by the late Serbian-American playwright Steve Tesich in The Nation magazine. Reflecting on the Iran-Contra scandal and the Persian Gulf War, Tesich lamented that ‘we, as a free people, have freely decided that we want to live in some post-truth world’. There is evidence of the phrase ‘post-truth’ being used before Tesich’s article, but apparently with the transparent meaning ‘after the truth was known’, and not with the new implication that truth itself has become irrelevant.

A book, The Post-truth Era, by Ralph Keyes appeared in 2004, and in 2005 American comedian Stephen Colbert popularized an informal word relating to the same concept: truthiness, defined by Oxford Dictionaries as ‘the quality of seeming or being felt to be true, even if not necessarily true’. Post-truth extends that notion from an isolated quality of particular assertions to a general characteristic of our age.

The Word of the Year 2016 shortlist:

Here are the Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year shortlist choices, and definitions:

adulting, n. [mass noun] informal the practice of behaving in a way characteristic of a responsible adult, especially the accomplishment of mundane but necessary tasks.

alt-right, n. (in the US) an ideological grouping associated with extreme conservative or reactionary viewpoints, characterized by a rejection of mainstream politics and by the use of online media to disseminate deliberately controversial content.

Brexiteer, n. British informal a person who is in favour of the United Kingdom withdrawing from the European Union.

chatbot, n. a computer program designed to simulate conversation with human users, especially over the Internet.

coulrophobia, n. [mass noun] rare extreme or irrational fear of clowns.

glass cliff, n. used with reference to a situation in which a woman or member of a minority group ascends to a leadership position in challenging circumstances where the risk of failure is high.

hygge, n. [mass noun] a quality of cosiness and comfortable conviviality that engenders a feeling of contentment or well-being (regarded as a defining characteristic of Danish culture):

Latinx, n. (plural Latinxs or same) and adj. a person of Latin American origin or descent (used as a gender-neutral or non-binary alternative to Latino or Latina); relating to people of Latin American origin or descent (used as a gender-neutral or non-binary alternative to Latino or Latina).

woke, adj. (woker, wokest) US informal alert to injustice in society, especially racism.

A version of this article originally appeared on the Oxford Dictionaries site.

Featured image credit: Image created for Oxford University Press. Used with permission.

The post Word of the Year 2016 is… post-truth appeared first on OUPblog.

10 representations of Psalm 137 throughout history [slideshow]

Psalm 137 is the only one out of the 150 biblical psalms set in a particular time and place. The vivid tableau sketched by the opening lines has lent itself to visual representations over the millennia.

By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept,

when we remembered Zion.

We hanged our harps upon the willows in the midst thereof.

For there they that carried us away captive required of us a song; and they that wasted us required of us mirth, saying, Sing us one of the songs of Zion.

How shall we sing the Lord ‘s song in a strange land?

From bas-reliefs in Assyria to brush strokes in Germany, these vivid lines have been envisioned by artists and musicians across millennia. Each interpretation brings something different to the story and shows the cultures which this psalm has touched.

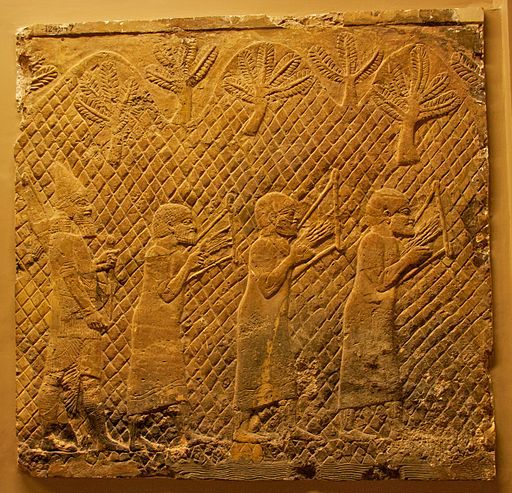

BAS RELIEF, CAPTIVES PLAYING LYRES (Ninevah/Assyria, 700 BCE)

This Assyrian bas relief, from Ninevah, actually slightly predates the forced migration of Judeans to Babylonia by more than a century, although it depicts captives carrying harps as is suggested in the psalm.

Image Credit: “Lachish Relief, British Museum 13” by Mike Peel. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

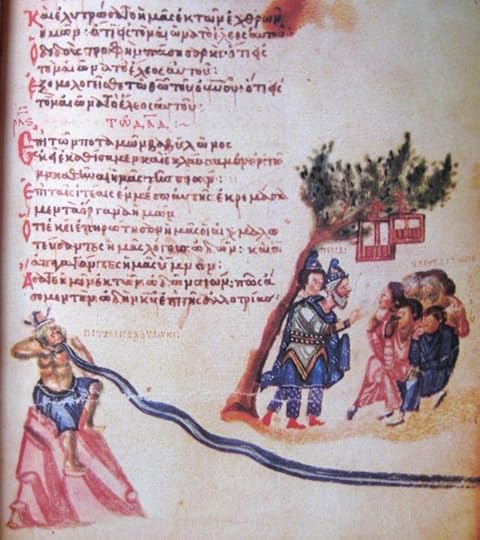

CHLUDOV PSALTER (Russia, c. 900 CE)

Some of the earliest visual representations of Psalm 137 are found in illuminated psalm books and manuscripts, from England to Russia.

Image Credit: “Psalm By the rivers of Babylon from Chludov Psalter.” Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Psalm_136_Initial_S (1)

ST. ALBANS PSALTER (England, 1130)

Some of the earliest visual representations of Psalm 137 are found in illuminated psalm books and manuscripts, from England to Russia.

Image Credit: “Psalm 136 (137), Initial S. In: Albani-Psalter.” Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

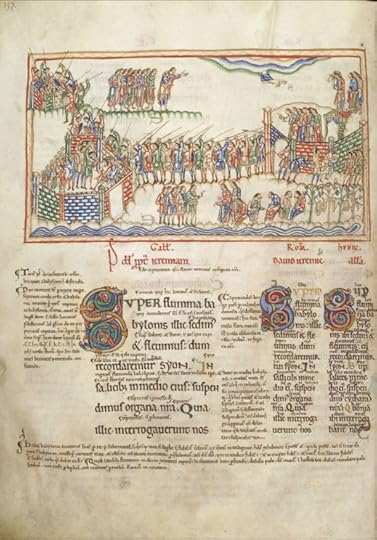

EADWINE PSALTER (England, c. 1155)

Some of the earliest visual representations of Psalm 137 are found in illuminated psalm books and manuscripts, from England to Russia.

Image Credit: “Eadwine psalter : Psalm 137 (136), Super flumina Babylonis.” Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

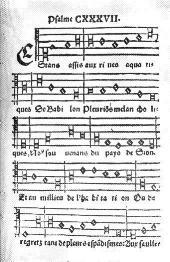

Psautier_huguenot_ps137_1539

JOHN CALVIN’S HUEGENOT PSALTER (France, 1539)

Psalm singing without accompaniment, harmony or embellishment became a crucial part of worship for Protestant Christians, especially in the Calvinist tradition that eventually dominated the religious culture of New England.

Image Credit: “Calvins Psautier Huguenot (ed. 1539) – Psalm 137” Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

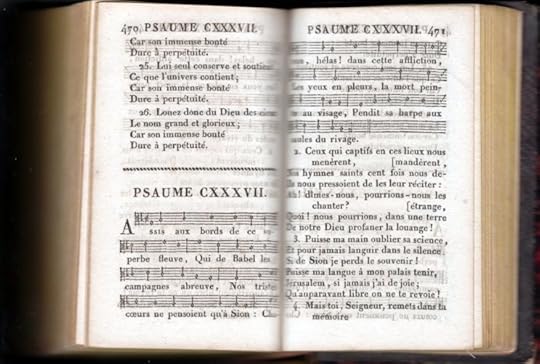

Psaume_137_1817

PROTESTANT PSAULTER (France, 1817)

Psalm singing without accompaniment, harmony or embellishment became a crucial part of worship for Protestant Christians, especially in the Calvinist tradition that eventually dominated the religious culture of New England.

Image Credit: “Psalm 137 in a French protestant psalm book of 1817” Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Ferdinand_Olivier_001

FERDINAND VON OLIVIER (Germany, c.1830)

With its undercurrent of nostalgic longing for a lost homeland, Psalm 137 was an attractive inspiration for Romantic painters and composers. The 1830s and 1840s witnessed a number of depictions by French and German painters. The German artist Ferdinand von Olivier was associated with the Nazarene movement, a group of Romantic painters who took inspiration from artists of the late Middle Ages and sought to restore a more direct and honest form of painting Christian subjects.

Image Credit: “Die Juden in der Babylonischen Gefangenschaft” Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

bendemann

“LAMENTING JEWS IN EXILE” BY EDUARD BENDEMANN (Cologne, 1831-32)

Born in Berlin to a Jewish banking family, Eduard Bendemann’s 1832 painting, Lamenting Jews in Exile, helped launch his career. Later he became professor at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts and served as director of the Dusseldorf Academy.

Image Credit: “Eduard Bendemann, Lamenting Jews in Exile, 1831–32.” Public domain via Wallraf-Richartz Museum & Fondation Corboud.

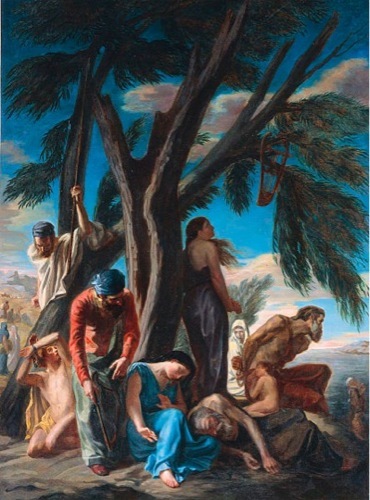

Eugène_Ferdinand_Victor_Delacroix_039

EUGENE DELACROIX (Palais Bourbon, France, c.1837-1848)

Ferdinand Victor Eugène Delacroix was the leading French Romantic artist, best known for his 1830 painting, Liberty Leading the People, with its unforgettable image of the bare-breasted woman rallying forces behind the French tricolor. His depiction of Psalm 137 was commissioned for the library of the Palais-Bourbon in Paris: “A weeping family, seated on the bank of a river, sadly contemplates the water while thinking of the distant fatherland.”

Image Credit: “Palais Bourbon, Malerei in der Kuppel der Theologie, Szene: Babylonische Gefangenschaft.” Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“THE LAST STOP OF THE JEWS LED INTO CAPTIVITY IN BABYLON” BY LOUIS DE PLANET (France, 1842-43)

A student of Delacroix, Louis de Planet was born into a wealthy family from Toulouse and completed a law degree before taking up painting.

Image Credit: “The Last Stop of the Jews Led into Captivity in Babylon” by Louis de Planet. Public domain via Musee des Augustins, Toulouse/Daniel Martin.

Featured image credit: Your Word, by Rachel Titiriga. CC BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post 10 representations of Psalm 137 throughout history [slideshow] appeared first on OUPblog.

November 15, 2016

Were farmers America’s first high tech information workers?

Settlers in North America during the 1600s and 1700s grew and raised all their own food, with tiny exceptions, such as importing tea. In the nineteenth century, well over 80% of the American public either lived at one time on a farm or made their living farming. Today, just over 1% does that in the United States, even though there is a surge going on in small organic family farming. The majority of American food is still grown or raised in the US, although much is also imported. So, any understanding about the role of information in any century involves farmers, in the beginning because almost everyone was involved, and later because they had figured out how to industrialize its massive production so that farming only required a tiny number of people. Information made that profound switch possible.

Farmers didn’t just use machinery that was invented over the past two hundred years, including the tractor in the twentieth century, which massively reduced the number of workers and animals needed to operate a farm. They also utilized data. By the 1870s, the US Government began collecting and disseminating scientific information to farmers. Beginning a decade earlier, Congress passed legislation that funded the creation of state universities for the purpose of doing research on agriculture and sharing the results with farmers. That is how the US acquired massive state universities like the University of Minnesota or the University of Wisconsin.

In 1862, Congress established the US Department of Agriculture and began a continuous program of publishing literature for use by farmers to improve their productivity and to address specific problems, such as curing animal and crop diseases. By the 1880s, state universities and the Department of Agriculture began hiring agricultural agents stationed in almost every agricultural county in the country to transfer research findings and best practices created at the state universities to individual farmers, one-by-one. They also disseminated information through training programs for future farmers, similar to programs like 4-H today. By the early 1900s female home economists, also funded by the US Department of Agriculture and managed by the state universities, were educating children and women about farming best practices.

Scientific research in the 1920s and 1930s expanded knowledge about plant and animal diseases, development of fertilizers, and hybrid seeds that led to higher yields of such crops as beans, corn, potatoes, and wheat. The US rapidly became one of the world’s largest exporters of agricultural products.

Image credit: Farm by G123E123E123K123. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: Farm by G123E123E123K123. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.In the years following World War I, farmers also extended their formal education from roughly the eighth grade through to completion of high school. High schools offered courses in agriculture and home economics. By the end of the 1960s, it was not uncommon for young farmers to have completed a college education with a major in agriculture. During the post-World War II years, the volume of literature on agricultural practices expanded massively and was used by college-educated farmers. They began attending seminars on agricultural practices sponsored by their state universities and county “ag” agents, while manufacturers of fertilizers and other products hosted these too.

Farmers gained access to the Internet in the 1990s, but largely on a wide-scale basis in the 2000s, when they accessed growing amounts of information about all manner of farming issues. They did more than use the Internet. Farmers installed micro weather stations on their properties and subscribed to aerial crop surveillance surveys, including accessing weather reports of their region from satellite-based services. Many communicated data through the Internet.

By the 2010s, wireless communications involving smart phones, laptops, and PCs had enabled farmers to build an extensive information ecosystem in support of their work. Their communications back and forth with agricultural experts, local universities, and vendors became more frequent and increased in volume.

By the 2010s, young farmers had taken to social media. If you subscribe to a CSA (Community Supported Agriculture) providing you with vegetables every week, then you probably also are receiving e-mails from your farmer reporting on the status of this week’s crops, also sending along recipes for cooking kohlrabi, and links to other food topics, such as recipes and about the “pros” and “cons” of genetically modified seeds, food, and animals. Go to a food market on a Saturday morning and invariably you will see a few tables with literature about agricultural issues.

The answer to our question is a resounding yes. Farmers used a combination of new tools, science-based information, innovations in fertilizers, seeds, and medicines, and every form of information and its technologies from the 1600s to the present. In each century, they were as “high-tech” and as advanced in the use of information as any other segment of society. And there is no sign that their appetite for big data, use of artificial intelligence, robotics, or digital sensors is going to decline. They continue to use these more than many other professions.

Featured image credit: Farm by Michael Pereckas. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Were farmers America’s first high tech information workers? appeared first on OUPblog.

Pathogen contamination in a clinical laundry facility: a Q&A with Karen E. Michael

The cleanliness of hospital environments, including bed sheets and patient gowns, plays a large role in the prevention of the spread of disease to hospital workers and other patients. To learn more about how bacterial pathogens are kept in check and the effectiveness of clinical laundry services in removing these bacteria, we asked Karen E. Michael, PhD candidate and an author of FEMS Microbiology Letters article “Clostridium difficile Environmental Contamination within a Clinical Laundry Facility in the USA”, to answer some pressing queries.

What is Clostridium difficile?

C. difficile is a bacterial pathogen that is the number one cause of hospital-acquired diarrhea. If a person has a C. difficile infection (CDI), they may not show any symptoms or outward signs of infection but are able to shed the bacteria. People with C. difficile-associated diarrhea can shed up to one billion bacteria in each gram of stool. The symptoms of CDI are varied, with diarrhea as the most common symptom. CDI can result in fatal blood infections and the enlargement of the large intestine, a condition called toxic megacolon.

What puts you at risk of acquiring C. difficile?

The risks of acquiring CDI include, but are not limited to, the use of antibiotics, medication for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease, antacids, hospitalizations, and being very young or very old. Another risk factor for contracting the bacteria is proximity to someone who sheds the bacteria.

The C. difficile bacteria have the ability to form spores. These spores have a tough outer structure that allow them to remain “alive” for years and to resist acidic conditions, high temperature environments (≥ 71°C, 160°F), radiation, drying, chemicals, and oxygen. This environmental hardiness means that people can develop CDI after coming into contact with spores months to years after they were shed. Anything that an infected person comes into contact with can be contaminated with these spores. This can include bed sheets, toilets, medical devices, and their environment.

Karen Michael, PhD candidate in the Department of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences at the University of Washington School of Public Health. Photo used with permission.

Karen Michael, PhD candidate in the Department of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences at the University of Washington School of Public Health. Photo used with permission.Why should we care about C. difficile?

In 2013, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classified C. difficile as an “immediate public health threat that requires urgent and aggressive action” because of the high cost of treatment and increased morbidity and mortality. In the United States in 2011, C. difficile was estimated to cost in excess of $1 billion for treatment and care. In addition, about 14,000 deaths are attributed to CDI each year. Often, more than one type of treatment is required to clear CDI. The combination of the bacteria’s ability to form spores and the extent to which infected patients shed the bacteria allows for extensive environmental contamination.

The environment can impact human health because it is a known reservoir for bacterial pathogens able to cause disease. C. difficile is primarily a hospital-associated bacteria, and healthcare workers, such as nurses and doctors, are at greater risk of exposure to hospital pathogens than the general population. While numerous studies have attempted to estimate illnesses among the healthcare workers from C. difficile exposures and recommend strategies to reduce or prevent disease, most of these studies do not include data on environmental contamination. Because the environment is such an important reservoir, these studies may be missing an important piece of the overall picture.

What do linens have to do with C. difficile?

Hospitals and clinics need to be kept clean, and fresh linens play an important role. When linens, such as bed sheets or patient gowns, are removed from a patient’s room, they are sent off to be cleaned. One offsite laundry facility in Seattle, Washington, USA, processes approximately 300,000 lb. (136,000 kg) of soiled linens each week from six local hospitals and more than 30 clinics. This facility cleans the linens and delivers fresh, laundry to the hospitals and clinics.

In our study, we wanted to know how dirty linens from the hospitals and clinics impacted the laundry’s environment.

What is the evidence of contamination in a clinical laundry facility?

Karen Michael tests high-touch surfaces for three types of pathogens at an industrial hospital laundry facility in Seattle, WA. Photo used with permission.

Karen Michael tests high-touch surfaces for three types of pathogens at an industrial hospital laundry facility in Seattle, WA. Photo used with permission.We found that 23% (25/120 samples) of sampled surfaces from the “dirty side” of the laundry facility surfaces had C. difficile contamination. The dirty side of the laundry facility is where the linens are handled prior to being washed and dried.

Only 2% (2/120 samples) of sampled surfaces from the “clean side,” or where the linens are handled after being washed, were positive for C. difficile. The two surfaces that were positive for C. difficile both came from a small area where soiled linen is handled in small batches. While the area is distinct from where clean linen is dried, ironed, and folded, it is on the same floor as the “clean side.” All of the samples that tested positive were in areas where dirty linens are handled; no C. difficile contamination was found in areas with clean laundry. This indicates that the dirty linens were the likely source of the environmental contamination in the laundry.

Based on this study, what is the take-home message?

The environment is an important source and reservoir of pathogenic bacteria like C. difficile. The C. difficile we found on the surfaces of the laundry facility likely came from dirty linens. The environment should be considered in infection control and environmental hygiene.

Featured image credit: Hospital corridor by cezjaw. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Pathogen contamination in a clinical laundry facility: a Q&A with Karen E. Michael appeared first on OUPblog.

ISIS is only a symptom– underneath lies a much deeper threat

“I learn a science from the soul’s aggressions.”

— Saint-John Perse

Amid all current debate about the best way to defeat ISIS, one easily forgets that this Jihadist adversary is merely the most visible expression of a much wider and much deeper pathology. Failing to understand this vital hierarchy of importance will be very costly, no matter what one’s own subjective position on counter-terrorism strategy and tactics may be. After all, an inevitable consequence of any such failure would be to strike vainly against symptoms, and not meaningfully against actual “disease.”

The epidemic violence we continue to witness in Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, and elsewhere, is only microcosm. It is, more precisely, just the most visible reflection of far more pervasive determinants. They are,: (1) the relentlessly malignant tribalism of our world order system; and (2) the fusion of derivative and broadly sectarian violence with reinforcing claims of “sacredness.” The philosopher Hegel once commented: “The State is the march of God in the world.” This crucial nineteenth-century observation now applies equally well to an expansive amalgam of twenty-first century Arab/Islamic terrorist groups, and not merely to ISIS.

Looking ahead, we must consider yet another ominous fusion. This is the prospective coming together of atomic capability with decisional irrationality. Such a fearful prospect should come to mind, not only in such “front page” venues as Iran and Pakistan, but also North Korea. As earlier instructed by the Prussian strategist, Carl von Clausewitz (On War), world politics are eternally and relentlessly systemic. It follows, we must finally understand, that what happens in north Asia, just as an example, could also substantially impact Europe and/or North America.

We can never really hope to fix the “ISIS problem” until we have first understood the more underlying human bases and expected rewards of Jihadist-engineered insurgent conflicts. It is important, therefore, that we soon learn to look seriously and continuously behind the news.

Always, it must be recalled, the conspicuously grinding threat from ISIS is more a visible symptom, than an actual disease.

If we should mistakenly focus too much on ridding ourselves of this singular symptom, and not the underlying disease, we could then find ourselves exacerbating the ultimately more fundamental and more insidiously “metastatic” pathology. To wit, if American policy should wrongly focus upon the “War Against ISIS” as consuming and overriding, we would then simultaneously strengthen other foes in Syria, Iran, Russia, and Hezbollah.

For other examples, focusing too much on ISIS could undermine our counter-terrorist regime allies in Egypt and Saudi Arabia, who are presently engaged in combat operations against Shiite Houthi rebels in Yemen, and also strengthen assorted Muslim Brotherhood forces, including Palestinian Hamas — the Islamic Resistance Movement — which is effectively the “Son of Muslim Brotherhood.” Of course, a too-consuming counter-terrorist focus on ISIS would correspondingly embolden a variety of core al-Qaeda organizations, groups from which ISIS itself had originally been spawned.

Image credit: Tercer premi en la categoria Individual de Notícies d’Actualitat al World Press Photo. BULENT KILIC / AFP by Jordi Bernabeu Farrús. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Image credit: Tercer premi en la categoria Individual de Notícies d’Actualitat al World Press Photo. BULENT KILIC / AFP by Jordi Bernabeu Farrús. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.In essence, any disproportionate harms that are consciously directed toward eliminating a particular terror group could at the same time benefit different terrorist adversaries, both Sunni and Shia. We must never lose sight of the fact that our enemy is not ISIS per se, but rather a flagrantly sweeping Jihadist ideology with multiple, disparate, and sometimes reciprocally related terror offshoots.

Always, it is this underlying ideology that we must “defeat,” not just ISIS.

It is, therefore, a war of “mind over mind” that we must now learn to wage, and not just the more familiar and more orthodox war of “mind over matter.” In this connection, it goes without saying, such a cerebral conflict is much more difficult to conduct successfully, and is also more operationally challenging.

Although we might prefer an adversary against which we could somehow appeal to reason, it is never for us to decide any pertinent enemy’s degree of attachment to the presumptively comforting fogs of irrationality. In response, we ought not flee from reason ourselves, but must nonetheless learn to deal effectively with those Jihadist enemies who might still yearn for the incomparably seductive whisperings of personal immortality.

From the beginning, all principal violence in world politics has been driven by contrived tribal conflicts, both between and within nations, and by a conveniently “sacred” promise to reward the abundantly faithful with freedom from death. A related promise has always offered to include each believer in a uniquely privileged community of them “elect.” Significantly, this always lethal promise is not unique to the present religious moment in history. In one sense, at least, it was as evident in the expressly anti-religious policies of the Third Reich, as it is today in easily recognizable parts of the ‘dar al Islam.’

On this persistently omnivorous planet, we humans often remain dedicated to virtually all varieties of ritual violence, and, accordingly, to various sacrificial practices that are readily disguised as either war or terrorism. Ironically, however, this markedly convenient dedication is not necessarily an example of immorality, or even of plain foolishness.

Here, history takes pride of place. Our entire system of international relations, first shaped at the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, is itself rooted in a seemingly immutable pattern of institutionalized horror. In this worldwide “state of nature,” as we already learned from the seventeenth century English philosopher, Thomas Hobbes (Leviathan), the life of man is necessarily “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short.” No doubt, many of us may still manage to live well in this murderous condition of nature, but only because we stubbornly refuse to believe what terrors must still lie ahead.

Preoccupied with reality television, and with every other conceivable form of distracting and demeaning political entertainments, we in the West are not just tactically vulnerable to impending paroxysms of mega-terror. We are also and more importantly unprepared. To change this, to meaningfully improve our national and global security prospects, we must first learn to carefully distinguish between symptoms from disease, and then, to thoughtfully combat the substantially broader and connective ideology of our collective Jihadist enemy.

In this way, now engaged in a more purposeful war of “mind over mind,” we could finally fashion a useful “science” from the Jihadist soul’s still-planned aggression.

Featured image credit: Rubble at Quneitra by watchsmart. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post ISIS is only a symptom– underneath lies a much deeper threat appeared first on OUPblog.

Vermeer and violins: science and art—strange bedfellows or partners in crime?

When Einstein claimed his theory of relativity came from a musical insight, no one blinked twice. Of course music could inspire scientific insight. But the reverse idea is often fraught with baggage. Artistic circles often feel that science is more threat than ally.

In the case of 17th century Dutch Master painter Johannes Vermeer and 20th century violinmaker Carleen Hutchins, science aided art but upset the apple cart of public opinion in the process.

The film Tim’s Vermeer chronicles the story of how engineer and inventor Tim Jenison set out to uncover the mystery behind the mystical photographic realism of Vermeer—down to grinding his own lenses, mixing his pigments following 17th century methods and building an exact replica of the room depicted in Vermeer’s painting The Music Lesson. Jenison demonstrates how Vermeer might have used a lens and two mirrors to aid his own sight.

Image credit: “The Music Lesson” by Johannes Vermeer. Circa 1662–1665. Public Domain in the United States via Wikimedia Commons

Image credit: “The Music Lesson” by Johannes Vermeer. Circa 1662–1665. Public Domain in the United States via Wikimedia Commons While art critic Jonathan Jones does not dispute the fact that Vermeer may have used optical devices in his studio, he indicts Jenison for missing the point of Vermeer’s genius–for confusing replicating art with creating it. “It is arrogant to deny the enigmatic nature of Vermeer’s art. If this art looks ‘optical,’ it can also look abstract. It is an act of seeing nature, not a work of copying it. Whether or not he made use of optical instruments, Vermeer looked at the world with a uniquely penetrating eye. He was able to paint what he saw with a delicate hand.”

Modern violin makers criticized Carleen Hutchins, the 20th century American female who applied acoustical physics to violinmaking and then invented a new family of violins, for “bringing science into the workshop”—even though it was already there. To separate acoustics from music is akin to separating the colors of the rainbow from the air itself.

Among her most celebrated scientific experiments, Hutchins applied Chladni patterns to “tune” violin plates. When a plate, sprinkled with sand or glitter, is vibrated, granules fall away from vibrating places and fall on to nodal lines, places where the plate is not vibrating, revealing different wildly beautiful geometric patterns at different frequencies—the reverse image of vibrating plate, like an old photographic negative. Hutchins used these patterns to guide her in carving archings and thicknesses of her top and back plates.

By comparing old violins with her new ones, Hutchins overturned centuries-old beliefs that violins made by old masters were inherently better. By using science to make more resonant, dynamic sounding instruments, Hutchins re-introduced acoustics into a violin dealing world that had focused on labels, (often fraudulent), provenance (who owned or played an instrument) and “expert” dealers who dictated value—rather than on how an instrument sounded.

The results of Hutchins’ use of science in violinmaking cannot be denied. She created a new violin family with more acoustical power, resonance and dynamics than the traditional quartet instruments—not to mention creating a whole new palette of sound from eight graduated-sized violins spanning the tonal range of a piano—a sound palette including colors and timbres never heard before in stringed instruments.

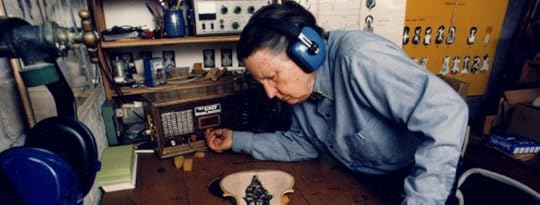

Image Credit: “Hutchins tuning fiddle plates using Chladni patterns, circa 1990.” Courtesy Hutchins estate.

Image Credit: “Hutchins tuning fiddle plates using Chladni patterns, circa 1990.” Courtesy Hutchins estate. In much the same manner that Jones dismissed Jenison for missing the inner genius and penetrating eye of Vermeer, luthiers, dealers, and musicians missed the point with Hutchins, dismissing her—and her revolutionary violin octet—as arrogance flying in the face of the genius of the Old Italian Masters. Instead if listening to her violins with open minds, critics were only too ready to reject her work out of some irrational fear that science might somehow pollute art.

Hutchins never implied that a Chladni pattern—or any scientific method—would automatically replicate the sound of an exquisite Stradivari. She suggested that her scientific experiments showed her another way to understand just one aspect of violin acoustics that the Old Masters must have found through “feel”—intuition born of thousands of hours spent carving and testing violin plates—organic wisdom learned through the repetition and perfection of craft.

Image Credit: “The first Hutchins violin octet. 1965. Taken by Arthur Montzka. Courtesy Hutchins estate.

Image Credit: “The first Hutchins violin octet. 1965. Taken by Arthur Montzka. Courtesy Hutchins estate. Vermeer’s inner eye produced his timeless art that continues to teach us to see with every moment we gaze at The Music Lesson. In much the same way, sand patterns could never replace what a luthier learns and comes to know intuitively through trial and error. But like the lens and the mirror for Vermeer, sand patterns served as a guide, a stepping-off point to create something totally new made possible through the tools of science. Vermeer and Hutchins—a new palette of color and a new palette of sound—are science and art strange bedfellows or partners in crime?

Image credit: “A series of Chladni pattern results tested on Hutchins fiddle plates at different frequencies.” Courtesy Hutchins estate.

The post Vermeer and violins: science and art—strange bedfellows or partners in crime? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers