Oxford University Press's Blog, page 448

October 29, 2016

World Internet Day: A reading list on older adults’ internet use

The internet is arguably the most important invention in recent history. To recognize its importance, World Internet Day is celebrated each year on 29 October, the date on which the first electronic message was transferred from one computer to another in 1969. At that time, a UCLA student programmer named Charley Kline was working under the supervision of his professor Leonard Klinerock, and transferred a message from a computer housed at UCLA to one at Stanford. The ARAPNET (Advanced Research Projects Agency Network), as it was called, provided the foundation for the contemporary internet.

From that first electronic exchange between Kline and message recipient Bill Duvall, the number of people using the internet has exploded from 738 million in 2000 to an estimated 3.2 billion worldwide in 2015, according to data from the International Telecommunication Union. In the US, young people went online earlier than older people, but today an estimated 60% of adults ages 65+ use the internet (compared to 86% of all Americans). The internet is an important source of information and social engagement for older adults, yet the most vulnerable older adults are least likely to go online. In celebration of this year’s World Internet Day, we have created a reading list of articles from Gerontological Society of America journals that reveal the ways that the internet has enriched the lives of older adults in the United States.

Has the Digital Health Divide Widened? Trends of Health-Related Internet Use Among Older Adults From 2003 to 2011, by Y. Alicia Hong and Jimmyoung Cho in Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences

This study explores how older adults use the internet to engage in four health-related behaviors: seeking health information, buying medications, connecting with people who have similar health problems, and communicating with doctors. They use data from the 2003, 2005, and 2011–2012 Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS). Health-related internet use (HRIU) among older adults increased 2003 to 2011, with the steepest increases in seeking health information and communicating with doctors online. By 2011, 80% of internet users ages 55+ sought health information online, 22% communicated with doctors, 21% bought medicine, and 3% communicated with others who shared their health concerns. These rates declined with age, and were higher among whites than ethnic minorities, higher income versus lower income older adults, and high school graduates versus dropouts, although disparities declined between 2003-11. The authors call for more senior-friendly online resources to bridge the digital health divide for vulnerable older adults.

Internet Use and Depression Among Retired Older Adults in the United States: A Longitudinal Analysis, by Shelia R. Cotton, George Ford, Sherry Ford and Timothy M. Hale in Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences.

The research team tracks whether Internet use among retired older adults in the United States is linked to changes in depressive symptoms, and whether this linkage is accounted for by reductions in older adults’ loneliness. They examined four waves of data (2002-08) from the Health and Retirement Survey. Internet use reduced older adults’ risk of depression by roughly one-third, and part of this reduction likely reflected the fact that internet use reduced feelings of loneliness. Internet use was particularly protective for older adults who lived alone. The authors conclude that encouraging older adults to use the Internet may help decrease isolation and depression.

Information and Communication Technology Use Is Related to Higher Well-Being Among the Oldest-Old, by Tamara Sims, Andrew E. Reed, and Dawn C. Carr in Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences

This study explores whether using the internet for socially meaningful versus informational goals had different effects on the well-being of 445 older adults ages 80+. They considered multiple dimensions of well-being, including life satisfaction, loneliness, goal attainment, subjective health, and functional limitations. The older adults used technology more to connect with friends and family than to learn information. On closer inspection, the researchers found that social motivations for using the internet were linked with better psychological health, whereas informational motivations were linked with better physical health. The results suggest that it’s never too late to use the internet, as adults even in their 80s and 90s benefit from its use.

Digital Dating: Online Profile Content of Older and Younger Adults, by Eden M. Davis and Karen L. Fingerman in Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences.

Older adults are among the most rapidly growing group of online daters. But how do they present themselves online? Do their presentations differ from younger adults? The researchers examined 4,000 dating profiles from two popular websites. They examined the ads of men and women ages 18 to 95, and detected age differences in self-presentation that reflected the realities of older versus younger adults lives. Younger adults are more likely to enhance the “self” when seeking romantic partnerships, referring to “I” and their personal and work achievements. Older adults are more positive in their profiles and focus more on health, connectedness, and relationships to others, referring to “we.”

Technology Access and Use, and Their Associations With Social Engagement Among Older Adults: Do Women and Men Differ? by Jeehoon Kim, Hee Yun Lee, M. Candace Christensen, and Joseph R. Merighi in Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences.

Do older men and women use technology in the same ways? This study uses data from the 2011 National Health and Aging Trends Study to examine whether the use of email and the internet by men and women affects the frequency with which they visit friends and relatives (informal social participation) and volunteer or engage in community activities (formal social participation). The researchers found that men are more likely to use technology for all different purposes, including communication, completing personal tasks, and handling health matters. However, women’s technology use was associated with increased levels of all forms of social engagement, yet just one form of men’s engagement: going out for enjoyment. The authors conclude that technology use may help to reduce older adults’ social isolation and improve their overall psychosocial well-being.

Featured image credit: laptop mobile sunglasses by 27707. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post World Internet Day: A reading list on older adults’ internet use appeared first on OUPblog.

Halloween’s killer cereals

For many of us, the prospect of Halloween is scary enough without the presence of roaming spirits. Those with children must weigh the risks of letting them trick-or-treat unsupervised—the familiar danger of “sugar overload”. Those with teenagers must consider the damage their brood are capable of doing, whether with eggs, toilet paper, or worse. Horror film goers will struggle with the walk home through darkened streets after back-to-back screenings. Those of the party-going persuasion must balance the demands of the cooling season with the fear of being inadequately costumed. And of course, there are those who dislike Halloween and its roving gangs of children and costumed horrors, who will be huddled at home, bracing themselves for a late night knock on the door.

But there is another silent spectre at this time of year and one that is often overlooked—gluten. Anybody who suffers from coeliac disease, or knows someone who does, will tell you how debilitating the cereal protein can be.

The very real fear of an accidental encounter with gluten can be magnified by the abundance of anonymous sugary loot distributed be well-meaning strangers. Once a sweet or chocolate bar is separated from its nutritional information, it can be very hard to determine if it is gluten-free, particularly since it is often the gluten-contaminated machinery the confectionery is processed on, rather than its actual ingredients, that make it unfit for consumption. Of course, there’s always the option of abstinence, yet with as many 50% of us sharing a partially hereditary craving for sugar, one that is rewarded by morphine-like chemicals in the brain, the temptation can prove very hard to resist.

Sugar will not be the only addictive substance going door-to-door this All Saints’ Eve.

But sugar will not be the only addictive substance going door-to-door this All Saints’ Eve. Alcohol will also be doing the rounds for those who prefer their carbohydrates in liquid form. The worst variant for gluten-averse drinkers is, of course, beer. Keep in mind that gluten is a generic term for the storage proteins found in plant seeds, the same proteins which are found in the wheat and barley that form the basis of most beers.

But serial swillers need not be cereal ones. Gluten-free beers made entirely from non-gluten ingredients such as sorghum, buckwheat, and common millet are a safer option.

For those pursuing gluten-free treats, Halloween’s Celtic roots may provide some ideas. Because of its autumnal place in the calendar, the festival has always been associated with harvest and food—particularly apples. These seasonal fruits have been used for games and fortune-telling, even throughout the twentieth century—and best of all, no gluten. And while corn does contain a form of gluten called zein, it’s usually well tolerated by those with coeliac disease and is popular in the US Halloween tradition.

Although the half of the population with a sweet tooth might like to update these treats to be more in line with twenty-first century norms by the addition of honey, toffee or taffy, perhaps the scariest thing of all is a Halloween without gluten or added sugar. Now that really is too scary.

Featured image credit: Halloween dessert. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Halloween’s killer cereals appeared first on OUPblog.

October 28, 2016

Why we love horror (and Halloween)

It’s dark and warm and chaotic. The people in my group are screaming and scrambling to get away from the maniac who’s lumbering toward us with a roaring, smoke-belching chainsaw. I’ve been expecting him, but still, my heart skips a few beats when he emerges in a cloud of smoke and deafening noise. The science journalist next to me looks like he wants to run off and to hell with his assignment. We’re in Dystopia Haunted House, a commercial horror venue open to the horror-hungry public. I’m scientific advisor to the haunt, and the journalist is doing a feature on the psychology of horror. We’re accompanied by regular guests who, incredibly, are paying good money to be terrified by chainsaw-wielding Mr. Piggy and his fellow scare actors. Why do they do it? How does it work, and what’s the appeal of horror?

The horror genre is a paradoxical one. Horror entertainment aims to evoke fear, anxiety, disgust, and dread in its audience. Those emotions don’t feel good, yet horror is extremely popular. And now that Halloween—the festival of horror—is rolling around again, people seek out horror films, dress up in spooky costumes, decorate their yards with the paraphernalia of dread and death, get together to do the zombie dance, and flock to the hair-raising haunts that have proliferated across the United States over the last several decades. The appetite for horror springs from human nature, and our desire to stare into the abyss finds satisfaction in pretty much all cultural domains—from religion over literature, films, and video games to the visual arts, art photography, and heavy metal music.

Photo of Mr. Piggy, a character in Dystopia Haunted House, by Andrés Baldursson/Baldursson Photography. Used with permission.

Photo of Mr. Piggy, a character in Dystopia Haunted House, by Andrés Baldursson/Baldursson Photography. Used with permission.Horror is crucially dependent on our biological constitution. We evolved to be fearful, to be keenly attuned to—and curious about—dangers around us. Like any other species on the planet, ours evolved in an adaptive relationship with its environments. For most of human evolutionary history, those environments teemed with danger. Our ancestors faced the perils of predators, the danger of infectious germs and bugs, the hazards of weather and landscape, the threat of attack from hostile members of their own species. In such a dangerous world, the fearsome were better equipped to survive and reproduce than those who were born fearless. Eventually, fearfulness became a universal trait. All normally-developing humans are born with a fear system that, like a smoke detector, is designed to be hypersensitive. We jump at shadows and presume the scratching of a branch on the bedroom window to be a blood-thirsty predator clawing for a way in. We’re very easy to spook, and horror exploits that fact of human psychology.

Horror works by showing us characters responding to nasty things, such as restless and decomposing corpses aching for human flesh, say, or giant predatory spiders. Those nasty things tend to reflect ancestral dangers. People easily acquire phobia of spiders because spiders over evolutionary time posed a very real danger to our ancestors, leaving an eight-legged imprint on our nervous system. We evolved to find rotting flesh disgusting—even more so when that rotten flesh moves around and wants to eat you. In interactive media, such as horror video games, we become protagonists in a fictional world that teems with danger. In haunted attractions, likewise, we’re in the middle of horror stories that unfold around us in real-time. Horror uses stimuli—often exaggerated for effect—that reliably target our evolved fear system, and we love it.

Zombies from George A. Romero’s groundbreaking 1968 horror film Night of the Living Dead (Image Ten/Laurel Group). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Zombies from George A. Romero’s groundbreaking 1968 horror film Night of the Living Dead (Image Ten/Laurel Group). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Horror entertainment serves important psychological and social functions. It allows us to get risk-free and low-cost experience with threat scenarios. When we visit a haunted house and come face-to-face with chainsaw-wielding maniacs and decomposing zombies, we’re expanding our experiential horizon to encompass genuine negative emotion. We learn what it feels like to be really, truly afraid. We fine-tune coping mechanisms that help us get through the horrors thrown up by the real world. When we watch a horror film with friends, we demonstrate our mastery to ourselves and our buddies, perhaps strengthening our bonds as we brave the horrifying experience together. When we play hide-and-seek with our children—essentially enacting an ancient pattern of predator-prey interaction—we’re letting them play with fear and anxiety, helping them to handle those emotions in the process.

Sometimes, of course, horror becomes too much. Upwards of 5% of visitors to Dystopia Haunted House are overwhelmed by the horrors and abort the tour voluntarily. Media psychologists have demonstrated traumatic effects of exposure to horror. In the right dosage, though, horror is an important means by which we become equipped to handle a world that is sometimes dangerous and often unpredictable. That’s all the more reason to embrace the fun of fear this Halloween.

Featured image: Vincent Price in House on Haunted Hill (1959). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Why we love horror (and Halloween) appeared first on OUPblog.

Aurality and the opening of oral archives

The most recent issue of the OHR includes an article about the Australian Generations Oral History Project and the importance of “aurality” to oral history. To learn more, we exchanged emails with Anisa Puri, a member of the project and President of Oral History NSW.

OHR: The article highlights the importance of the aurality of oral histories – of actually listening to the words as opposed to just seeing them printed on the page. In your work, how do you see this emerging awareness changing the field of oral history in general?

Anisa Puri: I think this is a really important shift. As oral historians, we know how essential it is to listen to an interview in order to interpret it. By listening, we observe and interpret meanings that are often lost in an interview transcript or summary. Speech carries meaning—whether it’s the quickening of the pace, the softening of a tone, or a pregnant pause. The cadence and emotional qualities of a voice offer important aural clues for us to interpret. Appreciating the importance of aurality extends into how we present oral history in creative and immersive ways too, whether it’s via a website, podcast, digital story, art installation, audio walking tour, museum exhibition or heritage interpretation.

In terms of my work, I recently finished writing Australian Lives: An Intimate History (with Professor Alistair Thomson), which will be published as a paperback and ebook in early 2017. The book illuminates the everyday experiences of Australians over the last century, and highlights change, continuity and diversity of experience. It is organised by life stages and themes, and features fifty interviews from the Australian Generations Oral History Project, which are available online through the National Library of Australia’s catalogue.

In the ebook version, readers can read and hear interview extracts. By hyperlinking each extract featured in the book to the correlating interview audio, we encourage readers to listen to the excerpts. Readers will be able to hear meanings, read emotions and observe other aural clues that our edited transcripts can’t convey. This piece, from an interview with Kathleen Golder, who was interviewed in Hobart, Tasmania in 2012, is a poignant example. Here, Kathleen, who was born in 1920, recalls leaving London for sunny Queensland in 1953, in fear of the Cold War. Like many other British migrants who became known as Ten Pound Poms, Kathleen took up the Australian Commonwealth government’s subsidised ten pound passage to Australia. The edited transcript below also showcases the differences, and dissonance, between reading an edited transcript and listening to unedited audio. (You will need to accept the National Library’s End User License Agreement and wait a few seconds to hear the audio. The interview will continue playing after the extract ends.)

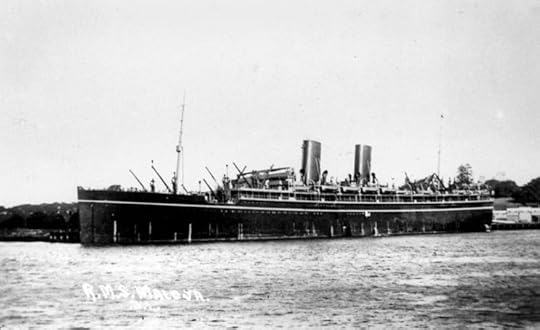

Maloja Ship, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Maloja Ship, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.It was on the Maloja. It was an old troop ship. It was a merchant ship coming out from Tilbury docks. It was on November 5th. There again, I was on the ship. It was dark. It was evening. I’d said goodbye to my mother and Maureen—my first daughter—because she stayed with my mother because of schooling and one thing and another, to come out later. But I was on the Maloja and it was slowly going down the estuary from Tilbury docks and I had this new baby in my arms. It was two weeks old. He was born on 22nd October and this was 5th November. I just bundled him up and he wasn’t, he wasn’t registered to come. So I had a bag. I popped him in a bag and hid him and got on the boat. And said nothing to anybody because they did not like you to travel with new babies or if you were past six months pregnant. The date for our departure did not come as early as it could have done and I was getting onto six months pregnant and I said, ‘I’ll get on that boat if it’s the last damn thing I’ll do. I’ll get on. I don’t care if I’m in labour, I’ll get on that boat.’ But I happened to have had the baby two weeks before we got on the boat. So I got on the boat with this new baby. And I was, stood—it was raining, as it would be in London in November—with this baby and I was crying, crying, ‘Oh dear me’.

I didn’t want to leave really. You know, it was my home. It was my family. My brothers and every—all my family were there. I didn’t want to leave but it was the best thing I ever did. But I didn’t know it then. One of the emigrants said to me later on that journey, ‘Were you that person crying on the boat at the back of that vessel?’ I said ‘It was, yes.’ He said, ‘I often, I did see you crying and I knew you had a new baby, it was you.’ I said, ‘Yes.’ So there was one witness to that very moment of my leaving.

By offering readers easy access to our primary sources, they can interpret the interviews for themselves. They can question our interpretation of the interview material, build on our analyses, or pursue different directions and develop new readings. This challenges standard roles—of what it means to be an author, or an audience—as readers can click to listen to our evidence. Perhaps this approach makes authors more accountable for how they interpret their sources too.

In a sense, the e-book will function as a curated entry point into the archive. It will encourage students, researchers, and the public to go beyond the contents of the book and engage directly with the interview collection—whether it’s delving deeper into an individual interview, using the keyword search facility to explore topics of interest, or exploring ideas for new research. By enabling readers to read and hear the contents of the e-book, we hope to spark their interest in the wider collection.

More generally, I think that focusing on aurality—and access to the actual interview—is helping to get oral history out of the archives and back into communities. As digital technologies offer new ways to connect with wider audiences, oral historians seem to be using more creative, immersive and engaging methods of using interview audio in how they present and share oral histories. It’s a dynamic space and I can’t wait to see how it develops.

You can find out more about Puri’s work on her Twitter account, or by checking out Oral History NSW. Chime into the discussion about aurality in oral history in the comments below or on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, or Google+.

Featured image: Australia by Angelo Giordano, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Aurality and the opening of oral archives appeared first on OUPblog.

Learning about lexicography: A Q&A with Peter Gilliver (Part 2)

Peter Gilliver has been an editor of the Oxford English Dictionary since 1987, and is now one of the Dictionary’s most experienced lexicographers; he has also contributed to several other dictionaries published by Oxford University Press. In addition to his lexicographical work, he has been writing and speaking about the history of the OED for over fifteen years. In this second part of his Q&A, we learn more about how his passion for lexicography inspired him to write a book on the development of the Oxford English Dictionary.

What got you interested in the history of the OED?

Working on the OED it’s hard not to develop an awareness of its history. We may be making use of all the modern tools that has to offer the 21st-century lexicographer, but we’re also surrounded by evidence of that history—not least the slips of paper on which people have been collecting quotations for the Dictionary for over a century and a half now, some of which we continue to consult alongside more high-tech resources. But I guess I became particularly interested in the history of the project thanks to J. R. R. Tolkien. Soon after starting work as a lexicographer I became aware that Tolkien was one of my predecessors—he joined the editorial staff for a year or so just after the First World War—and soon after that I realized that there might be unexamined material in the OED’s (extensive) archives that might shed light on this period of his life. (I knew that it was a formative period: Tolkien later said that he learned more while working on the OED ‘than in any other equal period of [his] life’.) Sure enough, there was some fascinating material in the archives. I eventually ended up writing a book about it (with my fellow OED lexicographers Jeremy Marshall and Edmund Weiner), called The Ring of Words.

When and why did you decide to write an entire book about the subject?

By the early 1990s I knew that there was a lot of material in the OED archives that hadn’t been made use of in any of the available books about its history. (The best of these was probably Elisabeth Murray’s Caught in the Web of Words, a superb biography of the Dictionary’s first editor James Murray…but that was published in 1977, which was beginning to be quite a long time ago, and of course it didn’t go into much detail about the period after Murray’s death in 1915.) So it was becoming clear to me that a new, scholarly history of the OED would be highly desirable. But I wasn’t sure that this was something I could really tackle…not until Martin Maw, the OUP archivist, persuaded me that it might be. Soon after that, I put together a book proposal, which OUP accepted.

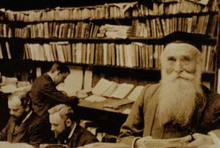

“The Professor and the Madman” by Manchester City Library. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

“The Professor and the Madman” by Manchester City Library. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.Sir James Murray arguably remains the most famous ‘personality’ attached to the story of the Dictionary. How did you come to see him?

The image that comes down to us through those well-known photographs of him, in his ‘Scriptorium’ surrounded by the working materials of the Dictionary, is certainly a rather formidable one. And he’s portrayed as just as formidable, if not more so, in Caught in the Web of Words—which of course was written by his granddaughter. So I did wonder, as I started on my research, whether I might find him to have…well, if not exactly feet of clay, then at least to be not quite the figure he had been cracked up to be. But the more I’ve studied, the more I’ve come to know him, the more I become convinced that he does truly live up to the hype. He was unquestionably the right man at the right time: it’s hard to think of anyone else with a comparable combination of abilities who was available in the 1870s to undertake the editorship of the Dictionary. And hard to imagine that anyone else would have managed to carry it through as he did, with his extraordinary capacity of hard work and his unshakable sense that this was the job he had been placed on this earth to do. OK, so he was notoriously touchy, and almost entirely lacking in the ability to delegate things; but even though I know how much he was actually a part of a team—and he was always at pains to emphasize that the OED was the work of many hands—he really does tower over the first edition of the Dictionary. And rightly so.

What other characters in the story of the OED stand out for you?

Oh, but there are so many! In fact this is one of the things I’ve tried to get across in my book: despite what I’ve just said about James Murray, the Dictionary really is the work of many people, and a great many of these people made an impressive or unique contribution to it, or were simply extraordinary in themselves. Just about all of the other people who have been Editors (with a capital E) of the OED have been outstanding in one way or another, from James Murray right through to John Simpson who retired three years ago. (I happen to think that Michael Proffitt, who took over from him, is pretty outstanding too; but he’s not history yet!)

And of course the story doesn’t begin with James Murray: he was really preceded as Editor by the amazing Frederick Furnivall, who in his own way had just as much energy as Murray—he used to row up the river Thames every Sunday well into his eighties, and founded half a dozen literary societies—but who had such unconventional ways that he drove many of his Victorian contemporaries up the wall. But I can hardly leave out Henry Hucks Gibbs, who simply saved the Dictionary from collapse on numerous occasions, either by lending Murray money when he was desperately short (Gibbs belonged to one of the richest families in England), or by talking him out of resigning as Editor. Or Fitzedward Hall, a recluse who would spend four hours a day, every day, reading the proofs of the Dictionary for something like twenty years. Or Walter Worrall, who was arguably ‘just one of the staff’—he worked as an assistant, first for Murray, then for the Dictionary’s other Editors—but who carried on compiling entries for nearly fifty years, longer than almost anyone else (although there are several other assistants who run him close). Or George Watson, another ‘mere’ assistant who was so devoted to his Dictionary work that, even after signing up to fight in the First World War, carried on correcting proofs—on one occasion in a captured German dugout, by candlelight. Or—more tragically—James Wyllie, who was only prevented from becoming editor of the Supplement to the Dictionary in 1953 by a catastrophic nervous breakdown (in the course of which he believed himself to have been given a divine revelation, as a result of which he knew how to eliminate war, disease, and pain from the world). Or Marghanita Laski, who from the 1950s to the 1980s sent in over a quarter of a million quotations for the use of the Dictionary. You see, the story isn’t short of remarkable people! And all of these are in the book, along with as many others as I could find room for.

Are there any unsolved mysteries in the story of the Dictionary?

How about this one? In the spring of 1899 Charles Onions—another member of the editorial staff, who would eventually become its fourth Editor—suddenly left Oxford, and his position as Murray’s assistant, for reasons which aren’t stated anywhere, but which Murray says in one enigmatic letter (referring to ‘something queer’) makes it unlikely that he would, or could, return to employment on the Dictionary…and yet, before the end of the year Onions was back at work, though now working for Bradley rather than Murray. What had Onions done? Try as I might, I’ve been unable to find out.

What sections of the history were the hardest to write?

I think I found it particularly difficult to write about the period from the 1930s to the 1950s. This was when the OED itself was in ‘suspended animation’: after the first Supplement to the Dictionary was published in 1933, all the remaining staff left or retired, or moved onto other projects, and it wasn’t until the 1950s that serious efforts to restart work. This is not to say, however, that there is no lexicographical activity to write about. On the contrary, there were several projects going on during this time—several different dictionaries, all related to the OED in some way—and it was quite a challenge keeping all these different narratives going, while at the same time keeping the OED itself in focus.

Even trickier, though, was the last chapter of all. This begins in 1989, just after the publication of the second edition of the OED; so the period which it covers falls entirely within my own time as a member of the Dictionary’s staff—and it’s difficult to write ‘history’ about a time which you can remember. It can also be difficult to write about events in which people who are still alive, and in some cases still at work on the Dictionary, were involved. No doubt a later historian, writing from the perspective of (say) a couple of decades in the future, will be able to be more objective—and may be able to draw on documentation that I haven’t been able to consult. Of course I could have decided to end the book with the publication of the second edition. But so much has happened in that quarter-century that I felt I really had to write something about it, even if it’s more of a simple chronicle of events than a history. After all, even that chronicle of events will make interesting reading for many readers.

Featured image credit: Oxford English Dictionary by mrpolyonymous. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Learning about lexicography: A Q&A with Peter Gilliver (Part 2) appeared first on OUPblog.

Military justice: will the arc continue to bend in a progressive direction?

Rarely has there been a time in which military justice has loomed so large, or in such diverse ways. Certainly at any given time there are likely to be one or two high profile cases around the world, but lately it has seemed that the subject is never long out of the public eye. Consider the following kinds of issues:

A Russian soldier stationed in Armenia murders a local family. Who should prosecute him for the murder, Russia or Armenia?

Peacekeepers in the Central African Republic prey on children for sexual favors. The UN has no judicial system to try such cases, and it needs to rely on troop contributing countries for military personnel. What if the troop contributing country is reluctant to investigate or prosecute? How aggressive can the UN realistically be in responding? Cancel the troop contingent’s participation in the peacekeeping mission? Insist on prosecution in open courts? Simply “name and shame”?

Countries with little or no commitment to democratic values insist on prosecuting civilians in military courts, sometimes using “terrorism” as the justification. (Egypt is the primary example, but has no shortage of company. Pakistan’s supreme court in 2015 upheld a temporary constitutional amendment allowing military courts to try civilians for two years.) Is this ever justified? What should other countries say or do in response?

Surprising levels of sex offenses by military personnel, often committed against other soldiers, have prompted serious concern by legislators in the United States, and a variety of strong remedial measures. This in turn has prompted fears that the pendulum has swung too far and that victims’ rights are being given higher priority than traditional rights of criminal defendants. How great a role should victims play in the criminal process? Should they have a veto over plea bargains, for example?

As fallout of that same concern over sex offenses, attention has also come to focus on whether a shift in the basic structure of military justice in the United States is called for: should commanders continue to have the power to decide who is court-martialed for what and who will serve as military jurors, or should those critical powers be shifted to lawyers and jury administrators independent of the chain of command?

The inexorable growth of social media and other kinds of widely available personal tech continues to present challenges to military tradition and, in the eyes of some, to “good order and discipline.” In a Facebook, crowdsourcing, or Pokemon era, can dissension in the ranks grow virally, and what, if anything, can military leaders do about it?

What are the new challenges presented by the growing diversity of military forces — ethnically, religiously, politically, and sexually. In tradition-bound societies – and what society isn’t? – what is to be done when, for example, political leadership, responding to shifting social expectations, take on issues like the integration and welcoming of sexual minorities? And in an era of heightened political discourse, how tolerant may we be of dissenting opinion in the barracks, below decks, or in the wardroom, on political issues. Think: racial intolerance, white-supremacist views, ill- or unconcealed contempt for political leaders? Might civilian control of the armed forces be at risk? Realizing that much more information is classified than needs to be, what is the proper response where soldiers, civilian government employees, or members of the public flout the rules for the protection of national secrets?

Soldiers military salute by skeeze. Public Domain via Pixabay.

Soldiers military salute by skeeze. Public Domain via Pixabay.Novel issues of accountability present themselves with increasing frequency. Modern high-tech warfare presents challenges to national disciplinary and legal systems that are unlike those faced in earlier eras. Who is to blame – and liable to be punished criminally – when a drone strike hits a wedding, a funeral, or a schoolyard? Joint operations add further complications. What if one part of a military operation is necessarily reliant on personnel from another country for identification or verification of targets?

As nation states continue to struggle with non-state entities such as ISIS that have only contempt for the law of armed conflict, will pressure increase to sweep mishaps and misconduct by one’s own forces under the rug, as if “the fog of war” meant all bets are off? Will electorates (and serving personnel) grow impatient with a persistent asymmetry in respect for law?

Finally, will the application of human rights to military personnel and operations continue to play an increasing role, or will that impulse lose force? Especially if, as in the UK, adherence to human rights standards brings with it potentially serious financial consequences. Countries may either find themselves opting out of human rights regimes that prove to be inconvenient or unexpectedly costly or being more reluctant than they have in the past to join in theoretically deserving foreign missions of one kind or another.

Plainly, the historic struggle for the rule of law both between and within armed forces is moving into a new battle space. What seemed tidy and appropriate half a century ago now seems contingent and debatable. National and international institutions are going to be tested repeatedly as this struggle plays out. In the process, we will learn whether the past few decades of progress reflect merely a temporary phase or whether, to borrow a phrase from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the arc will continue to bend in a progressive direction.

Featured image credit: Military decorations medal by jackmac34. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Military justice: will the arc continue to bend in a progressive direction? appeared first on OUPblog.

October 27, 2016

11 things about women in Ancient Israel you probably didn’t know

In a book mostly written by men and about men, what is the role of women? Over 90% of the people named in the Hebrew Bible are men. Finding out about women’s experiences is not an easy task, but scholars have been able to figure out a lot by carefully combing through the text. While women were largely confined to the household, they also were a critical part of a society’s social, political, and economic well-being, since the sustainment of the household was so vitally important to ancient life. To better illustrate this, we complied some interesting facts about what life was like for women in ancient times:

1. Hard work wasn’t just for the men in the ancient Israelite household. Women were responsible for transforming raw materials into food and clothing. It’s been estimated that every day it took women two or more hours just to grind grain to make flour alone.

2. Women may have had a significant amount of control of the household’s material resources.

3. Mothers were more likely to name their children than fathers.

4. In ancient Israel, women functioned as medical specialists, primarily as midwives. Child birthing was dangerous and midwives had to possess considerable skill.

5. Many of the social, political and especially religious institutions excluded women. For example, women had to perform their morning rituals significantly farther away from Yahweh’s temple proper than the men. In Ezekiel 8:14, women pray by the temple’s northern gate; while men participate in the service in the temple’s inner court between the temple’s front porch (dĕbîr) and its courtyard altar (Ezek. 8:16). The Leviticus purity laws restricted women’s access to the temple during their menses and postpartum discharges.

“Queen Esther,” by Edwin Long, 1878. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Queen Esther,” by Edwin Long, 1878. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.6. Women nonetheless found a place in the ritual life of ancient Israel. They were responsible for preparing many of the customary, religious offerings. They prepared grain and foodstuff offerings, libation offerings, and incense offerings.

7. Women were responsible for the musical performances during rituals and celebrations. Moses’ sister Miriam led women of Israel in celebration of the Israelites’ successful crossing of the Red Sea; other similar celebrations can be found in Judges, Samuel, and Psalms. Women were also portrayed numerous times being in charge of musical festivities during the autumn harvest festival of Ingathering, or Sukkot.

8. Women had better religious opportunity in less bureaucratic institutions. Regional sanctuaries did not constrain women’s potential to practice their religion as much. Hannah is depicted in the Bible going to Shiloh to engage in complex rituals to ask God for a child and is invited to join in the sacrificial meal of Sukkot with the other women of her household at Shiloh. Moreover, Hannah was likely involved in the sacrificial offerings that preceded the meal.

9. Miriam, Deborah, Hulda, Noadiah, the unnamed prophetess of Isaiah 8:3, and “the daughters … who prophesy” are all women identified as prophets in the Hebrew Bible.

10. Female prophets portrayed as coming into conflict with male authorities are depicted negatively. Miriam, Noadiah, and “the daughters … who prophesy” were all examples of this in the Hebrew bible. Though Noadiah is named a prophet, virtually all we know about her is that she opposed the rebuilding Jerusalem’s walls that was being championed by Nehemiah and disparaged for this stance in Nehemiah 6:14.

11. Women held important leadership positions as queen mothers. Israel’s queen mothers “seem to have served as official functionaries within their sons’ courts.” They also played an important role in naming their husbands’ heirs to the throne. When David was on his deathbed, Bathsheba persuaded him to appoint Solomon as the next king of Israel, instead of having his oldest living son, Adonijah, inherit the throne.

Featured image credit: “Isaac’s servant tying the bracelet on Rebecca’s arm” by Benjamin West (1738-1820) . Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post 11 things about women in Ancient Israel you probably didn’t know appeared first on OUPblog.

Homer’s The Odyssey: challenges for the 21st century translator

Homeric word-order is unusually accommodating towards its English equivalent. Verbs usually come where you expect them, adjectives sit near their nouns. Compared to, say, the complex structures of a Pindaric ode, or the elliptical one-line exchanges of dramatic dialogue, Homer’s largely paratactic progression of ‘…and…but…when…then…’ presents his translator with few immediate problems. I found this particularly helpful, as I had set myself a discipline of keeping as closely as possible to a version where the English line corresponded to the Greek. As well as offering easy reference to those studying the poem closely, I found it helped sustain the onward drive of the narrative.

The toughest challenge for the 21st century translator is undoubtedly that of register. As we all know, no one ever spoke Homeric Greek. It is an amalgam of different dialects, predominantly Ionic, whose effect is to set the story apart from the everyday, and to lend it a dignity appropriate to a tale of long ago heroic deeds. That said, Homer does often go remarkably well into current English. ‘Tell me, Muse, of the man of many turns, who was driven/far and wide after he had sacked the sacred city of Troy’ is a near-literal rendering of the Odyssey’s first two lines. Compare the task of producing an acceptable version of ‘His sweet spirit surpasses the perforated labour of bees’ (Pindar, Pythian 6.52-4).

Still, there are times when one yearns for a modern epic poetic, to capture something of Homer’s heroic loftiness, at the same time as satisfying the two classes of notional classics readers: staying close to the Greek and offering a good read to the casual bookshop/internet buyer. It can’t be done consistently, of course. We can no longer draw on the poetic diction available to English writers in the 300-odd years from Shakespeare to the Georgians. T.S. Eliot saw to that, and in any case no one these days – with the possible exception of Derek Walcott – writes epic.

Matthew Arnold saw the problem clearly 150 years ago, in his first Oxford poetry lecture ‘On Translating Homer.’ He accurately observed that ‘the translator of Homer should be above all penetrated by a sense of the four qualities of his author: that he is eminently rapid…eminently plain and direct…and eminently noble.’ Much of his entertaining diatribe was directed at the quaint inversions of an Iliad translation by Francis Newman (brother of John Henry), which relied heavily on an elaborate quasi-poetic diction that was reaching the end of its useful life. Arnold’s own quoted version of Iliad 19.400-24 is a brave effort (in hexameters!) to purge his English of Newmanisms, though it does to our ears verge on the fusty:

‘Why dost thou prophesy so my death to me, Xanthus? It needs not.

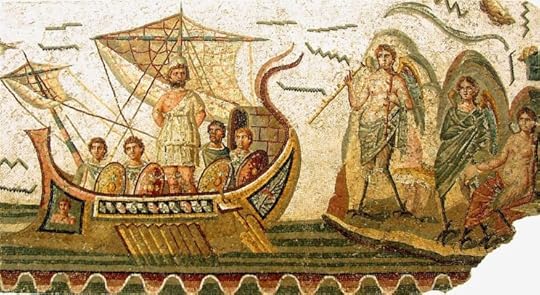

Mosaïque d’Ulysse et les sirènes by Habib M’henni. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Mosaïque d’Ulysse et les sirènes by Habib M’henni. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.I of myself know well, that here I am destined to perish,

Far from my father and mother dear: for all that. I will not

Stay this hand from the fight, till the Trojans be utterly routed.’ (419-23)

I suppose there is here an attempt to convey nobility, or elevation (the passage comes after all at a crucial point in the poem).

Arnold dealt only with the Iliad, whose tragic theme lends itself to his idea of nobility. Peopled almost entirely by battling heroes, the poem has a kind of relentless grandeur; even the contemporary translator finds that once he has chosen his medium and scrambled on to a certain level, as it were, it is not all that difficult to soar now and then (Richmond Lattimore’s 1951 version and Martin Hammond’s 1987 do this pretty well).

The Odyssey is quite different. Unlike the earlier poem, with its focus on aristocratic champions seeking honour and fame on the battlefield, the Odyssey’s eponymous character is a different kind of hero – patient, enduring, resourceful, tough and inventive, reliant on cunning for survival in a hostile environment. Moreover, the people he encounters are drawn from a much wider social range than the Iliad’s narrow warrior-world. The Iliad’s action is confined to Troy and the plain outside its walls; by contrast, the Odyssey carries us over much of the know Greek world: royal palaces in the Peloponnese, Crete, Odysseus’ Ithacan home and household in the far west, not to mention his forays into fairyland, where anyone can turn up and anything happen. Much is told in a rapid, plain, and direct way; and there is nobility too.

All this means is that the translator has to find a number of separate voices, to describe strange places and happenings and to bring out the tone of exchanges between different kinds of people: Telemachus’ journey in Books 1-4 to adulthood, Odysseus’ adventures with monsters, his trip to the edge of Hades, his stay among the Phaeacians, his time in the swineherd Eumaeus’ hut, the episode with his old dog, the slaying of the suitors, his reunion with Penelope, and much more. It all sounds a big challenge, but I found I was helped in this by a notable piece of Homeric alchemy: the formal language that so exactly suited the Iliad’s high tragic seriousness turned out to be supple enough to convey the domestic and the bizarre – though never at the cost of dignity. Whether the result avoids the opposing pitfalls of banality and pomposity is up to the reader to decide.

The post Homer’s The Odyssey: challenges for the 21st century translator appeared first on OUPblog.

Place of the Year 2016: behind the longlist

We continue our reflection on 2016 with a more in-depth look at the nominees for Place of the Year. Previously, we introduced our readers to the nominees simply as a list. This slideshow guides you through the tumultuous year that is currently coming to a close. While some of our nominees are a bit obvious–Aleppo, the UK, and Colombia, for example–we also wanted to shine a spotlight on the nominees that may be seen as less influential. After all, Sweden being named the best place in the world to raise a girl and the remotest island in the world starting to become entirely self-sufficient are achievements that deserve our attention. Take a look at the nominees and don’t forget to vote in the poll below.

Aleppo

News from Aleppo in 2016 has been consistently tragic with the Syrian Civil War still raging on. Civilians in Aleppo have been living under a blockade and lack access to basic needs such as electricity and food. The city has been bombarded by Russia and Syria in an effort to quash the Islamic State, though it has been estimated that around half the casualties have been children. A photograph of a young boy in Aleppo, bleeding and covered in ash brought the horror of the Syrian Civil War to the world’s attention. As one candidate for President of the United States demonstrated publicly, many people still are unaware of the situation in Aleppo.

“Aleppo 03” by Bernard Gagnon, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Tristan da Cunha

Tristan da Cunha represents so much of what is most fascinating about planet Earth. The most remote inhabited island in the world, Tristan da Cunha is interesting enough with that fact alone. This year, the community of the remotest island began to take steps towards becoming entirely self-sufficient.

“Tristan da Cunha, British overseas territory-20March2012” by Brian Gratwicke, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Colombia

The world directed its attention to Colombia earlier this year when voting was opened up to the public on a referendum that would end the country’s conflict and bring about lasting peace. The Colombian civil war has been ongoing for over 50 years, making it the oldest armed conflict of the Americas. At least 220,000 lives have been lost and close to six million people have been displaced. Though this year’s referendum was ultimately voted down by the Colombian people, the hope for peace is not lost. President Juan Manuel Santos was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts and the Nobel Committee also noted that the prize should be “be seen as a tribute to the Colombian people who, despite great hardships and abuses, have not given up hope of a just peace…”

“Juan Manuel Santos 2” by Jfbeltranr, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The UK

The UK made its biggest splash in international news with its vote for the Brexit—the colloquial term for Britain parting ways with the European Union. The results of the vote were something of a shock to the world political and economic stage. David Cameron stepped down as Prime Minister of Great Britain shortly after the decision was made final. The effects of Brexit are felt far beyond European borders.

London by Adam Derewecki, Public Domain via Pixabay

The Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea embodies the migrant crisis—record-breaking numbers of people, primarily from Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq, have risked or lost their lives this year while crossing this sea. According to the UN, 3,800 migrants have died in the Mediterranean Sea so far this year, making 2016 already the deadliest year on record, with two months still to go.

Refugee escape by Gerd Altmann, Public Domain via Pixabay

Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro hosted this year’s Olympics, and in spite of some early setbacks, it is generally agreed that the competition was a success. However, Rio was back in the news later this summer when Brazilian president Dilma Rousseff was impeached on charges of corruption and removed from office, and the political and economic crisis in Rio and the rest of Brazil is ongoing.

“Rio de Janeiro” by Poswiecie, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The White House

With the contentious US presidential race nearing a close, it seems clear that the country will go in one of two very different directions, depending on who moves into this residence next. This potential place of the year also made the news when Michelle Obama reminded us at the Democratic National Convention that the White House was built by slaves.

The White House by David Mark, Public Domain via Pixabay

Sweden

Sweden consistently comes in near the top of rankings of the world’s best and happiest countries. This year, for example, Sweden was rated the best country to grow up in as a girl according to Save the Children, ranked #1 in the Good Country Index, and was chosen as the best country to raise children in according to the HSBC Expat Explorer Survey. Based on Sweden’s astoundingly high quality of life and especially the country’s focus on gender equality, Sweden is a strong contender for Place of the Year.

Sweden by Сергей Бузилкин, Public Domain via Pixabay

South Africa

The #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall protest movements earned South Africa its place on this longlist. Since 2015, South African students have been protesting tuition raises and unequal access to education and have demanded the decolonization of their education system. In 2016, the protests revived and led to clashes with police and university closures, attracting widespread media coverage and sparking solidarity protests around the world.

“Jameson Hall – University of Cape Town” by Julien Carnot, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Featured image: Globe by Unsplash, Public Domain via Pixabay.

Place of the Year 2016

The post Place of the Year 2016: behind the longlist appeared first on OUPblog.

Open in Action

Over a decade has passed since the Budapest Open Access Initiative and the Berlin Declaration on Open Access. A bystander could be forgiven for thinking that the level of discussion and the apparent differences in position across higher education institutions, publishing houses, laboratories, conference halls, funder headquarters, and government buildings must mean that progress has been limited. As such this year’s International Open Access Week (OA Week), with a theme of ‘Open in Action’, is a good time to reflect on what is happening with open access; what is being developed, the changes which are being introduced, and the systems which are being implemented to help open content up. Progress has been more significant than is often appreciated and there continues to be practical and constructive engagement with options, policies, and infrastructure. For Oxford University Press (OUP) OA Week coincides with another development in our support for open access. At the end of September 2016 OUP started to register DOIs (Digital Object Identifiers) on article acceptance, rather than on publication, and began to provide authors with enhanced metadata to facilitate compliance with open access mandates, notably the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) open access policy.

HEFCE’s policy requires authors to deposit their Accepted Manuscript in an institutional repository within three months of their article being accepted by a journal, on the understanding that the article will remain closed until a specified embargo period has elapsed. From 1 April 2016, authors from UK Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) need to comply with the policy’s terms in order to make their research outputs eligible for the next Research Excellence Framework (REF), making easy compliance crucial.

The HEFCE policy aligns itself with standard embargo periods of 12 months for STM subjects and 24 months for HSS areas, however the need for authors to deposit their articles on acceptance introduces a new layer of compliance requirements and a new layer of complexity given most other policies have focused on the date of publication. Institutions have grappled with the need to develop workflows which will allow them to accommodate a future ‘deposit on acceptance’ requirement, and although HEFCE did respond to institutional feedback and subsequently allow for a grace period of one year during which authors can move to compliance by depositing on article publication, some UK HEIs (such as Oxford and Cambridge for example) have already launched campaigns to encourage their authors to deposit articles into their repositories on acceptance.

This year’s International Open Access Week, with a theme of ‘Open in Action’, is a good time to reflect on what is happening with open access

At OUP we have looked at how we can help with these new requirements and whether there are options to reduce institutional and individual pain points for compliance. We have amended internal and external systems to ensure that authors have the information they require when looking to comply with the HEFCE policy. And we’ve done so in a way which we hope will be transferable to many other funder requirements worldwide.

OUP believe that registering DOIs on acceptance and encouraging authors to deposit this with their repository record will improve linking between their Accepted Manuscript and the Version of Record, ensuring that readers will be able to locate the source publication of content they discover in a repository. The early registered DOI will be issued to authors in an email on acceptance, along with other bibliographic information including self-archiving information, any applicable embargo period, and the official acceptance date of the article. We understand that whilst many of our UK based authors will be looking to comply with the HEFCE policy, many of our non-UK based authors will need to comply with other OA requirements. We believe this additional metadata will provide all of our authors with the tools required to successfully deposit their article when and where necessary.

In order to enable early registration of DOIs it was important for us to be clear on what constitutes the point of acceptance. HEFCE guidance states that the date of acceptance is the point at which “the article is ready to be taken through the final steps toward publication (normally copy-editing and typesetting)”. We have therefore classified the acceptance date as the date upon which an author signs a licence to publish in the journal; this being the date from which the journal has the necessary rights to publish the content. At this stage a DOI will be registered for the article and this will link out to a holding page until the article has been published online.

This is an exciting development and we are confident it will make the compliance process easier, clearer, and quicker for our authors. Ben Johnson, Policy Advisor at HEFCE, said “I’m delighted OUP are implementing early registration of DOIs. I thank OUP for their leadership on this and on the author information which will be great for HEIs”. It’s positive to see that these changes have been gratefully received by the community, and we look forward to seeing the benefits transpire for our authors, to seeing these developments ‘in action’.

Featured image credit: Startup by StartupStockPhotos. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Open in Action appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers