Oxford University Press's Blog, page 450

October 24, 2016

The ultimate reading list, created by librarians

There are only a few weeks left until the UKSG Forum 2016, and to get into the spirit, we’re reflecting fondly on the UKSG conference that took place in Bournemouth earlier this year, and the OUP prize draw that had everyone talking.

We asked our librarian delegates to help us build the perfect library by answering one simple question: which one book couldn’t you live without?

Whilst the instructions were straightforward – write your chosen title on one of our book stickers and stick it on the bookshelf – the question itself proved challenging for the majority of our exceptionally well-read participants. Reactions ranged from pondering for a few minutes, and ‘going away to think about it’, to attempting to sneak more than one title into the library. One passer-by observed that the competition was a trickier, literary version of ‘Desert Island Discs’.

Over the two days of the conference, we saw our library grow to incorporate fact and fiction, brand new titles, and the classics, across a full range of genres.

#shelfies from the OUP stand at the UKSG conference. Photos taken by Sally Bittiner.

#shelfies from the OUP stand at the UKSG conference. Photos taken by Sally Bittiner.What do librarians like to read?

Of a grand total of ninety entries, seven titles appeared twice in our perfect library, including The Master and Margarita, A Prayer for Owen Meany, and the Norwegian classic Hunger (Sult).

We were pleased to see many librarians keeping in touch with their inner child, with the kids’ classics of The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe, The Hobbit, The Wind in the Willows, and The Magic Faraway Tree each occurring twice. Speaking to the participants, we learnt that many felt compelled to choose a title that had made an impression on them in childhood.

Our competition also paid testament to the enduring popularity of the classics. Indeed, a mighty seventeen Oxford World’s Classics appeared on our shelves, including Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (added by a participant who had visited Shelley’s grave at St Peter’s Church in Bournemouth earlier that very day), Pride and Prejudice (added by an enthusiastic Colin Firth fan), Middlemarch, Little Women, and The Count of Monte Cristo.

Though no single author dominated the bookshelf, we did see some authors cropping up more than once. Popular novelists included J. K. Rowling, Roald Dahl, Haruki Murakami, Virginia Woolf, and John Williams, each with two different titles in our perfect library.

So, here it is, our ultimate reading list as chosen by some of the most qualified and enthusiastic bibliophiles we know. How many have you read?

A Brief History of Time by Stephen Hawking

A Passage to India by E. M. Forster

A Prayer for Owen Meany by John Irving

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

Alone in Berlin by Hans Fallada

Brodeck’s Report by Philippe Claudel

Butcher’s Crossing by John Williams

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory by Roald Dahl

Circle of Friends by Maeve Binchy

Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell

Dangerous Liaisons by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos

Dark Fire by C. J. Sansom

Dead Souls by Nikolai Gogol

Death and the Penguin by Andrey Kurkov

Dune by Frank Herbert

Emotional Intelligence by Daniel Goleman

Engleby by Sebastian Faulks

Fantastic Mr Fox by Roald Dahl

Flambards by K. M. Peyton

Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

Game of Thrones by George R. R. Martin

Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell

Good Omens: The Nice and Accurate Prophecies of Agnes Nutter, Witch by Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman

Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone by J. K. Rowling

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban by J. K. Rowling

Hunger (Sult) by Knut Hamsun

Into Thin Air: A Personal Account of the Mt. Everest Disaster by Jon Krakauer

It by Stephen King

Juniper by Monica Furlong

Kafka on the Shore by Haruki Murakami

Les Miserables by Victor Hugo

Little Women by Louisa May Alcott

Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov

Lord of the Flies by William Golding

Middlemarch by George Eliot

Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck

Orange (author unknown)

Our Man in Havana by Graham Greene

Perfume: The Story of a Murderer by Patrick Süskind

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

Rich Dad Poor Dad by Robert Kiyosaki and Sharon Lechter

Room by Emma Donoghue

Stoner by John Williams

Tess of D’Urbervilles by Thomas Hardy

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer by Mark Twain

The Bees by Laline Paull

The Bible

The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas

The Girl with all the Gifts by M. R. Carey

The Giving Tree by Shel Silverstein

The Godfather by Mario Puzo

The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

The Hobbit by J. R. R. Tolkien

The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe by C. S. Lewis

The Magic Faraway Tree by Enid Blyton

The Martian by Andy Weir

The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov

The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco

The Pillars of the Earth by Ken Follett

The Prodigal Summer by Barbara Kingsolver

The River of Lost Footsteps: A Personal History of Burma by Thant Myint-U

The Roman Republic: A Very Short Introduction by David M. Gwynn

The Third Wave by Alvin Toffler

The Thorn Birds by Colleen McCullough

The Time Traveler’s Wife by Audrey Niffenegger

The Waves by Virginia Woolf

The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame

The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle by Haruki Murakami

Tiden Second Hand by Svetlana Aleksijevitj

To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf

Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson

Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackeray

Veden Peili by Joseph Brodsky

War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy

Watership Down by Richard Adams

We Need to Talk About Kevin by Lionel Shriver

Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys

Written on the Body by Jeanette Winterson

Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë

Featured image credit: CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The ultimate reading list, created by librarians appeared first on OUPblog.

Discussing Open Access in action

The 24 October marks the beginning of International Open Access Week 2016. This year, the theme is “Open in Action” which attempts to encourage all stakeholders to take further steps to make their work more openly available and encourages others to do the same.

In celebration of this event, we asked some of our Journal Editors to discuss their commitments to Open Access (OA) and how they support their colleagues in making research more accessible.

* * * * *

“Open Access benefits those based in developing countries to be able to access, download, and disseminate research in the field and in their countries. Health Policy and Planning is committed to continue working with OA and continuing to collaborate with organisations in support of OA in the future.”

— Sandra Mouiner-Jack, Editor-in-Chief of Health Policy and Planning

* * * * *

“My laboratory and I believe that all published papers eventually gather the attention (or notoriety) that they deserve, especially from the people who are most interested in a paper’s particular field of study. For that reason, we think much more about the quality and reliability of our results than about the ultimate publication destination for any particular manuscript. When we do decide to write up and publish, we strongly favour Open Access solutions and corresponding open release and access to our primary data. Following a policy of openness at all times has never failed to reward us after publication through the interest and feedback from colleagues and competitors in our chosen field.”

— Barry Stoddard, Senior Executive Editor of Nucleic Acids Research

* * * * *

“In my experience Open Access papers are more widely read, shared, and cited than those behind paywalls, particularly in poor or middle-income countries. And OA is of particular importance during viral outbreaks, such as Zika and Ebola, which is a topic that Virus Evolution covers.”

— Oliver Pybus, Editor-in-Chief of Virus Evolution

* * * * *

“It is official, we now live on an urban planet. Urban dwellers everywhere are experiencing unprecedented social and ecological changes as a result of urban population growth. Over the last 25 years there has been an emergence of what I refer to as ‘urban practitioners’ which includes architects, engineers, landscape architects, urban planners, park and land managers, urban ecologists, social scientists, and policy makers to name few. In an effort to create more liveable cities they are employing evidence based research and information into their work. Much of this information is published in peer reviewed journals that are not accessible to many of these ‘urban practitioners’ who function outside academic institutions. Providing Open Access of this critical information would facilitate the creation of more liveable cities in the future.

“In addition, as new cities are created, especially in developing countries, they also face formidable challenges regarding energy, water, waste management, pollution, and food production. Fortunately, there is a vast knowledge base that exists within our libraries and electronic databases created by engineers, designers, planners, ecologists, social scientists and educators who built, manage, and study our well established cities which are primarily located in the developed northern temperate regions of our planet. Unfortunately, much of this information is unavailable to ‘urban practitioners’ in developing countries because they cannot afford access to these resources. Providing Open Access to the information published on existing cities would greatly assist developing countries in addressing their future challenges resulting from their growing urban population.”

— Mark J. McDonnell, Editor-in-Chief, Journal of Urban Ecology

* * * * *

“The benefits of scholarship in general, and research funded by society in particular should be freely available. I believe that the world of scientific publishing needs to respond to this challenge and I am delighted to take on the role of editor in chief of an Open Access journal with a clear focus on making medicine accessible – not just to the medical community – but also to patients. We plan to encourage our colleagues to submit to Open Access journals where their work can reach beyond an elite group of professionals who can afford to pay access charges. We believe that this will allow both lay and professional readers across the world to share the excitement of scientific discovery. The question is not whether Open Access publication has a future – the question is how we, as a community, work together to shape it.”

— Siladitya Bhattacharya, Editor-in-Chief, Human Reproduction Open

* * * * *

“Open Access journals are the future for scientific publishing, it is only a matter of time until all journals will be Open Access. Access through print is disappearing and scientists today access nearly everything online. The traditional selection of specific journals due to subscription rates and impact is gone, as citations and simply access by all scientists has no limitations in Open Access journals. Although you may disagree with the shift in publishing, the paradigm shift has occurred.”

— Michael Skinner, Editor-in-Chief, Environmental Epigenetics

* * * * *

“One of the most compelling things about the Open Access movement is how it continues to inspire people into taking action and how it compels all parties to change our established ideas of scholarly communication. The call to action has seen responses from the entire spectrum of scholarly research, from individuals such as Joseph McArthur and David Carroll (inventors of the Open Access Button), to funders and political entities like the EU Competitiveness Council calling for immediate open access for scientific papers by 2020, and publishers having to develop new platforms to meet an increasing demand for more access to research and data. Amongst all of this action we are finding ever more interesting and novel innovations that are helping make scholarly communication an increasingly open process.”

— Nikul Patel, OUP Open Access Publisher

Featured image: Open Book library by lil_foot_. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Discussing Open Access in action appeared first on OUPblog.

What is the future of human rights in the UK following Brexit?

Imminent departure from the European Union has delayed but not dimmed the British government’s determination to have done with domestic human rights law. Enacted in the early years of the Blair administration, the Human Rights Act 1998 has long irritated the Conservative Party and its influential friends. The right-wing media hate it for equipping celebrities (and of course everyone else) with a right to respect for their privacy with which to fight press intrusion. The senior military deplore it because it insists on proper inquiry into bad behaviour in a way that they say diminishes the country’s capacity to fight. And it has been a perennial punch bag at Tory party conference, for standing in the way of tough action on terrorism and immigration, by the current Prime Minister in the past, and the current Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Defence in the present. It is the recent attack on immigration launched by the Home Secretary Amber Rudd at the most recent Tory conference that makes the Act particularly vulnerable in the context of the move to Brexit.

The Government has been clear that resident European citizens have no right to regard the UK as their guaranteed home in the aftermath of the UK’s exit from the EU. Of course there is a hope that they will be able to stay in the country, an expectation even, but this depends on the outcome of discussions between Britain and the rest of the EU. In the cold words of the Secretary of State for International Trade, Liam Fox, such persons are one of the “main cards” available to him and his colleagues in the months of negotiation that lie ahead. To make this threat real, the Government will need either to repeal or sharply to modify the Human Rights Act, or indicate in an unequivocal way that any rulings issued under it that seek to inhibit the forced deportation of Europeans will be disregarded.

The Government has been clear that resident European citizens have no right to regard the UK as their guaranteed home in the aftermath of the UK’s exit from the EU

Article 8(1) of the European Convention on Human Rights guarantees among other things respect for family life and this was one of the rights made part of UK law by the Human Rights Act. The case-law under the Act (and at the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg) makes clear that forced expulsion of residents attracts the protection of this provision, and in the drastic example of Brexit there would be little doubt that the courts would not be willing to save such actions by reference to the reasonably tightly drawn exceptions to the right that are set out in Article 8(2). The explicit discrimination on the basis of nationality would also most certainly attract the attentions of Article 14, on non-discrimination in the enjoyment of these Convention rights.

The Human Rights Act would stop all government discretionary power designed to make a reality of such deportations and would also lead the courts quickly to declare primary legislation designed with these expulsions in mind to be incompatible with the Convention. These later declarations are not binding on the government (an important concession to parliamentary sovereignty in the Human Rights Act) but that would not stop the Strasbourg Court finding a breach when the matter came before it. So to be free to talk tough, to make the millions of Irish, French, Poles and so on living in Europe, effective bargaining chips, Mr Fox and his friends will need to escalate the bluff by creating conditions on the ground for it to be carried out if it has to be, not only repeal/modification of the Human Rights Act but – contra the Prime Minister’s promise during her brief campaign for the leadership – withdrawal from the Convention system as well. European residents will become like nuclear warheads, primed to be fired at any moment in the hope that they never will be.

This may seem a dark scenario, too awful to be taken seriously, like a hard border returning in Ireland or (starved of foreign students) the collapse of the UK’s universities as major intellectual resources. But such conversations are inevitable if the logic of Brexit is to be taken seriously. Whether that logic can triumph against market power, the global rights movement, and basic human decency remains to be seen.

Featured image credit: EU United Kingdom by Elionas2. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post What is the future of human rights in the UK following Brexit? appeared first on OUPblog.

October 23, 2016

Nuclear arms control in a globalized world

We live in a dangerous and uncertain world. While terrorism is the most immediate contemporary threat, the dangers of nuclear weapons remain an ever present concern. During the Cold War a series of nuclear arms control agreements helped to mitigate the worst excesses of the arms race and contributed to the easing of tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union, and their respective alliances. Since 1985, however, the salience of nuclear weapons in international relations has declined, even though the nine nuclear weapons states continue to possess in excess of 10,000 nuclear weapons between them. Many other states have the potential to develop nuclear arms, and fears exist that terrorist groups might acquire some form of nuclear capability. A key question in global security is whether nuclear arms control still has a future?

In 2010 the United States and Russia signed the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) which involved significant cuts to be made in strategic delivery vehicles (SDVs) and in nuclear warheads in the period up to February 2018. SDVs were to be cut to 700 and nuclear warheads to 1500. Despite the problems over the Ukraine and deteriorating US-Russian relations, both countries by 2016 are very close to these targets, and key provisions of the Treaty including data exchanges, notifications, and on-site inspections have all been met.

As well as New START, the Nuclear Security Summit (NSS) Process, initiated by President Obama has also resulted in some important improvements. Starting in 2010, 53 countries have participated in a series of meetings designed to reduce the amount of dangerous nuclear materials (enriched uranium and plutonium) and to improve security of these materials. 12 of 22 NSS participating states are now free of enriched uranium, and 35 states have signed up to a joint statement binding them to strengthen their nuclear security. These summits have helped to set the foundations for a global nuclear security regime.

Nuclear Submarine Normandy cherbourg by jackmac34. Public domain via Pixabay.

Nuclear Submarine Normandy cherbourg by jackmac34. Public domain via Pixabay.Another major advance has come with the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in July 2015. As result of this agreement Iran made a series of commitments to reduce its stockpile of low-enriched uranium for 15 years; to accept an enrichment cap of 5060 centrifuges; and to modify its Arak Reactor so that it could not produce plutonium. In return international sanctions were suspended. The result, according to many commentators, is that Iran has been prevented from becoming a nuclear armed state for at least 15 years.

These are important agreements, but major hurdles remain in controlling weapons of mass destruction. North Korea has flouted the non-proliferation regime and continues to test both nuclear weapons and the means to deliver them. Nuclear modernisation by the main nuclear powers, especially the United States and Russia, also continue to threaten the bargain at the heart of the Non-proliferation Treaty of 1968. Non-nuclear states signed up to the treaty on the understanding that the nuclear states would work towards the elimination of their nuclear weapons. Reductions have been made, but the modernisation process and the time involved since the treaty was signed has left many of the non-nuclear weapon states to argue that the goal of elimination is not being treated seriously by the nuclear states.

The United States has suggested a further one third cut below the New START levels, but Russia continues to link such cuts to the resolution of other issues including US missile defences in Europe, US non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe; and advanced conventional forces. These disagreements, together with a continuing dispute between the United States and Russia over the Ukraine, as well as compliance issues relating to the 1987 INF Treaty, is seen by many as an indication that future arms control agreements between them, is, for the time being, unlikely.

This pessimism is reinforced by a continuing problem over the ratification of the 1996 Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty. The Treaty requires 44 nuclear capable countries to ratify it before it can be implemented. So far only 36 of these countries have undertaken ratification, leaving 8 countries, including the United States and China, to do so. There seems to be no sign at present that the US Congress is willing to ratify the Treaty because of concerns about verification and the continuing reliability of the US nuclear stockpile.

Despite these problems, the answer to the question: ‘Does nuclear arms control have a future?’, must be ‘yes.’ The New START Treaty continues to cut the numbers of US and Russian nuclear weapons. The NSS framework has helped to control dangerous nuclear materials and the JCPOS has prevented Iran from becoming a nuclear power for the next 15 years at least. Clearly there are many hurdles to overcome, exemplified by the North Korean nuclear programme, the dangers of terrorist groups acquiring weapons of mass destruction, and the continuing difficulties over ratifying the CTBT. The continuing distrust between the nuclear powers themselves, and between the nuclear powers and many non-nuclear states, as well as the effects of globalization on the continuing availability of nuclear materials and knowledge, means that arms control can only have a limited effect on reducing tensions and preventing the further proliferation of nuclear weapons in the years ahead. Rather than highlighting these difficulties, however, and adopting a fatalistic approach, it is important for the international community to focus on nuclear arms control measures and renew its efforts to work towards improving the various regimes designed to control all weapons of mass destruction.

Featured image credit: Nuclear Weapons Test by WikiImages. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Nuclear arms control in a globalized world appeared first on OUPblog.

Are God and chance compatible?

It has long been the unquestioned assumption of many religious believers that the God who created the world also acts in it. Until recent scientific discoveries, few challenged the idea of how exactly God interacts with the world. With the introduction of Newtonian science and quantum theory, we now know much more about how the world works, and the mode of God’s action has become a serious question for believers.

Many may believe God and chance must be seen as mutually exclusive. It is not uncommon to hear that “ascribing anything to ‘chance’ rules out God’s action.” This does not mean, of course, that believers constitute a homogeneous group whose views can be neatly summarized. There is a good deal of variety in their thinking, which has surrounded this topic in the past and there is a considerable overlap. Some very ancient views persist to this day, and new theological arguments have emerged to explain how God interacts in a world in which chance seems to exist. Nevertheless, it is possible to roughly trace a progression by which believers have struggled to accept the existence of both God and chance.

The first challenge occurred with the rise of Newtonian science. This made it appear that the world was a lawful place in which things happened in a predictable way. Rocks fell back to the ground when raised and the heavens changed in a predictable way – not at the whim of fate or fortune. It was certainly true that many things appeared to happen outside this regular regime and hence ideas of magic, luck and such things continued to thrive.

At this point, believers faced a fork in the road. The first fork provided no challenge to orthodoxy. It supposed that God acted alongside the laws of nature. This posed no problem to the believer because a God who had created and maintained the world could surely modify it by special acts as circumstances required. The second fork became what is called deism. This gave priority to regularity and supposed that the world was, indeed, a grand machine with which God did not or chose not to interfere.

One has to question: does that leave any space for God to act? How then, can he exert any influence on it at all? How can evil exist in a world created by an all loving God?

The second challenge to the Christian conception of God came when science moved into the world of very small things at the quantum level. It then became possible to account for what happened on the macro scale by referring to minute and apparently random happenings on a scale so small that it defied imagination. If our appearance on the scene was an accident, then God appeared to have been squeezed out, leaving the field to chance. Chance seemed to set God in opposition to nature. Faced with this dilemma, Christians, in particular, have taken three lines of argument.

One was to maintain the traditional line by arguing that God is, indeed, in control of everything – including quantum events. That means that he directs the path of every single sub-atomic particle with a view to achieving his will. This is obviously a gargantuan task involving trillions upon trillions of events. However, if God is viewed as being far larger and more complex that we can imagine – as he is in this context – this task seems feasible. From this traditional Christian viewpoint, the fact that many happenings are apparently contrary to the intention of God poses no problem. This issue can be circumnavigated by the idea that the appearances can be misleading. If we were only able to see things from God’s perspective, on a grand scale, things might look different. Short term problems can vanish when seen through God’s eye, from a broad enough perspective.

A second approach to addressing the theological dilemma of God and chance is to accept most of the scientific picture of the world, and suppose that God acts in a sophisticated way, by only directly changing certain critical events. Thus, for example, he might have kept evolution on course by intervening only at the crucial points necessary to ensure that humans appeared as the end-product.

A third approach is to take the evidence of science at face-value and accept that chance is not apparent but real. This obviously means that God created the world as we find it, and evil and suffering are an integral part of it. One has to question: does that leave any space for God to act? How then can he exert any influence on it at all? How can evil exist in a world created by an all loving God? The obvious, and perhaps the only, answer is through people – either individually or collectively. This view gives to humans a key role, assuming that they are not deterministic robots but agents in the creative process. Agents in the creative process have the option to choose between good and evil; good being God, and evil which can be viewed be the absence of God, as some scholars have argued.

As mentioned in a previous article, unpredictability is an all-pervasive part of life, and it contributes much to the excitement and interest of living. From games of chance, where the outcomes depend on the throw of a die or the shuffling of a pack of cards, to the choice of ends in a football match, chance contributes much to the richness and enjoyment of life. This may well be a mimicking of God’s ongoing creative activity on the cosmic scale.

Featured image credit: “Tiffany Education” by Louis Comfort Tiffany and Tiffany Studios. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Are God and chance compatible? appeared first on OUPblog.

Accessible and inaccessible disciplines: why philosophy and science are similar but are treated differently

Amongst my books is a late nineteenth century edition of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. Purchased from a used bookshop many years ago, it contains the previous owner’s signature on the flyleaf together with a commentary: “Started Boston 1883. Began again in Salt Lake City February 1891. Began again 698 East Capitol St. Oct. 1911. Finished Nov. 1911.” I feel a bond with that reader, almost certainly not a professional philosopher, who persevered with difficult material, convinced that what was within was worth understanding. The commentary illustrates a striking difference between types of academic discipline. In some, the material, at least superficially, is accessible. In others, the door is firmly closed. Many of the creative arts fall into the first kind. Allen Ginsburg’s Howl can be appreciated by a teenager for its dark dynamics, despite the multitude of scholarly texts that deepen our understanding of that poem. In many sciences, the primary sources–journal articles–are impenetrable to nonexperts.

What of my own field, philosophy? Historically, some important philosophers, David Hume and René Descartes amongst them, combined sophisticated ideas with an elegant and accessible style. Unassisted readers struggle with other historical figures, such as Leibniz. But philosophy of the last fifty years has faced a special dilemma. Many outsiders, while recognizing that philosophy is difficult, become hostile and resentful when reading contemporary authors. Those same readers have a different reaction when faced with a journal article or even a textbook in molecular biology, acknowledging that the subject matter does not easily yield to amateurs, and rightly so. The reasons for the difficulties in both cases are straightforward–technical vocabularies, the assumption of much previous knowledge, subject matter that is remote from ordinary experience. What is puzzling is the difference in attitude by nonexperts. My Boston reader of a century ago thought that Kant was worth twenty eight years of effort and stuck with it.

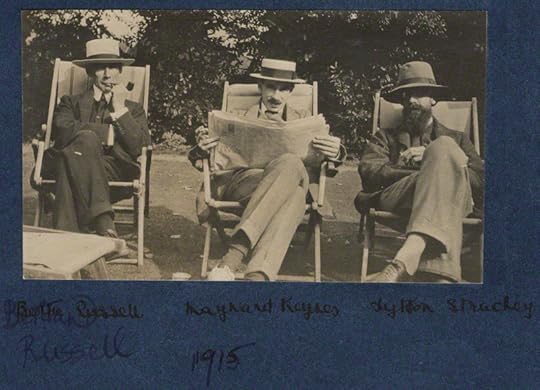

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell; John Maynard Keynes, Baron Keynes; Lytton Strachey, by Lady Ottoline Morrell, 1915 – NPG Ax140438. © National Portrait Gallery, London. Used with permission.

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell; John Maynard Keynes, Baron Keynes; Lytton Strachey, by Lady Ottoline Morrell, 1915 – NPG Ax140438. © National Portrait Gallery, London. Used with permission. [/pull]

Behind this antipathy to philosophy lies a peculiar psychological attitude, one that I have encountered many times. It is exhibited by a wide range of readers, from Nobel prize winners to Amazon reviewers. An individual, let’s call him Horace, has been successful in some area of intellectual activity such as physics, law, or engineering. Horace then infers from this success that he is equally adept in all other intellectual domains, including philosophy. Difficulties ensue, Horace does not understand why the author is arguing for X, or even what the argument for X is, but what Horace does know is that it’s the author’s fault or the fault of philosophy in general.

Not far from Kant on my bookshelves is Bertrand Russell’s The Problems of Philosophy. Originally published in 1912, it was part of the Home University Library series–later acquired by Oxford University Press–and its intended audience included working men and women with only a rudimentary formal education. Over a century later, Russell’s book remains a model of clarity and creativity. It was successful in part because thousands of readers who had never been to university, including miners, steelworkers, and other industrial laborers, were willing to come to grips with difficult ideas presented by a master of English style. They lacked hubris; they knew that this was going to be hard work and stuck with it. That attitude is rarer than it used to be, hence we now have a Sparknotes version of Russell’s book, complete with a “Plot Overview.” On our side, we philosophers should stop writing notes to one another. Some have done so; there are volumes in Oxford’s Very Short Introductions series that provide lucid, occasionally brilliant, expositions of contemporary philosophical ideas that challenge the reader.

What I fear is being lost, and it results from multiple influences, is the willingness to move from being a consumer of information to being an internal participant in philosophy. In mathematics, computer packages that solve differential equations are magnificently powerful but they can easily reduce you to a willing spectator. To understand mathematics, you have to work, really work, with the material. In many areas, Wikipedia is a wonderful source of information but it rarely jolts your mind. Contrariwise, information loss can force you to think, hence the old mathematical joke that to write an advanced textbook you just remove every other line from an intermediate textbook. To gain access to the realm of philosophy, you have to struggle with ideas, many of them weird and unappealing, few of them easy. That is what my Kantian book owner was willing to do. Those who are not willing will be left permanently on the outside, staring with puzzlement at their own reflections in the philosophical window.

Featured image: Scenography of the Copernican world system by Andreas Cellarius. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Accessible and inaccessible disciplines: why philosophy and science are similar but are treated differently appeared first on OUPblog.

October 22, 2016

Is there a war on Christmas?

Is there a War on Christmas? Of course there is. Donald Trump is sure of it, Bill O’Reilly says so, and John Gibson agrees. The Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights declares it to be true and the American Family Association does too. It is a calculated and pernicious attack not only on the holiday but on Christianity itself.

Is there a War on Christmas? Of course not. Michelle Goldberg says it is a canard and The New Yorker agrees. Jon Stewart mocks the notion, and The Guardian calls it nonsense. To claim there is such a war is an example of “Christonormativity,” a right-wing plot to bolster the ratings of Fox News and to disguise the drive for Christian theocracy.

Is there a War on Christmas? Yes, indeed. In fact, there is a history of almost two thousand years of opposing, controlling, reforming, criticizing, suppressing, resurrecting, reshaping, appropriating, debating, replacing and abolishing the world’s most popular festival.

Let’s start at the very beginning, in the days of the early Christian Church. It may be surprising to learn that it took several centuries for the faithful to begin to celebrate the nativity of their Saviour. This was a natural response to a belief in the imminent return of Christ—why pay attention to His humble earthly origins when he was soon to return in glory to judge the living and the dead? When Jesus seemed to tarry and Christians were forced to deal with those Gnostics who denied that God had taken on a solid human form, the Church began to emphasize the stories of the Bethlehem birth. There were those Christians, however, who opposed any celebration of the event, saying that birthdays were only for pagans, emperors and pharaohs and the like.

Nativity scenes, which we’ve grown accustomed to seeing during the holiday season, were seldom found in early Christian celebrations. Image credit: “Nativity” by Jeff Weese. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Nativity scenes, which we’ve grown accustomed to seeing during the holiday season, were seldom found in early Christian celebrations. Image credit: “Nativity” by Jeff Weese. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.These objections were overcome and by the early 300s the Nativity was being openly marked in the western part of the Roman Empire on December 25. This led to over a century of struggle between those supporting that date and those in the great cities of the east, such as Alexandria and Jerusalem, who would prefer to celebrate both the Nativity and various other sacred moments on January 6. While this argument was being waged, Christian leaders were engaged in another fight, this one against believers who were assimilating the festive practices of pagan Roman holidays like Saturnalia and the Kalends. This argument was going to be waged for centuries and you will still find Christians today who are uneasy about the Christmas tree, gifts, and feasting.

The Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century dealt a strong blow against Christmas celebrations when it attacked the cult of saints; out went St. Nicholas and other saintly gift-bringers, to be replaced by the figure of the Christ Child and assorted shaggy, monstrous helpers. As the Reformation gained strength, there were calls for Christmas itself to be abolished; the holiday was called popish, pagan, Saturnalian, and debauched. In the 1600s Christmas disappeared from Scotland, England (for a time), parts of the Netherlands and New England colonies, and even when it was restored it had lost the support of the elites—in England and America it had become an alcohol-centered season of low-class rowdiness. During the French Revolution Christmas was derided as part of the worship of that “Jew slave” and dispensed with until the rise of Napoleon.

The act of gift-giving at Christmas has been criticized as a means of promoting secular traditions over religious celebrations. Image credit: “Christmas presents under the tree” by Alan Cleaver. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The act of gift-giving at Christmas has been criticized as a means of promoting secular traditions over religious celebrations. Image credit: “Christmas presents under the tree” by Alan Cleaver. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.In the early nineteenth century Christmas was reinvented in England and the United States, becoming more domestic, child-centered and middle-class. Charles Dickens reconnected the holiday with charity and forgiveness while New York poets and artists invented Santa Claus. This was not enough to redeem the celebration in the eyes of fundamental Protestants who fought a rear-guard action to the holiday which continues in the 21st century. The rise of the radical left saw a number of atheist and socialist attempts to replace Christmas with a more secular and socially-progressive December festivity. This was not successful until the 1900s when revolutionary governments in Mexico, China and the Soviet Union succeeded in wiping Christmas off the calendar.

The war around Christmas reached its peak in the 20th century. In Nazi Germany, Hitler’s government realized popular attachment to the holiday was too great for it to be done way with and sought to bend it to their own ends. Christmas became paganized and militarized—St. Nicholas and the Christ Child were replaced by figures from Teutonic folklore while the swastika and solstice sun became suitable ornaments on the Yule tree. After the Second World War, the fight against Christmas was waged on two main fronts—the drive to eliminate it and other religious symbols from public spaces, and the resistance around the world to an Americanized “Coca-Cola” version of the season. Decades of litigation, decrees and legislation has pushed Christmas out of many areas such as schools, hospitals and government property, giving rise to massive resentment against the political correctness that has produced such neologisms as “Sparkle Season,” “The Twelve Days of Giving” and the “Holiday Tree.” In Europe and Latin America, anti-Santa Claus movements have been opposing the American-bred gift-bringer and reviving the claims of the Three Kings, the Christ Child, St. Nicholas and (in a bizarre nationalistic moment in Mexico), the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl.

Christmas plays too large a part in the global economy and the social life of nations and families for it ever to be without controversy. We may expect it to be celebrated and attacked for centuries to come.

Featured image credit: “Santa Christmas ornament” by m01229. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Is there a war on Christmas? appeared first on OUPblog.

Developing the virtues

Helicopter parenting is denounced by onlookers (e.g., David Brooks) as babying children who should be self-reliant, a highly valued characteristic in the USA. Children should not need parents but should use their own capacities to get through the day. The notion of a good person is intertwined with this individualistic view of persons and relationships. Good people know how to behave. They stand on their own, with little dependency on others. They are given rules and obey them. Bad people don’t–they are whiny and weak.

It should be noted that when one applies this view to babies, to make them “independent,” one not only misunderstands baby development but creates the opposite result—a less confident, regulated and capable child (see Contexts for Young Child Flourishing).

This machine-like view of persons and relationships contrasts, not only with what we know about child development (kids’ biology is constructed by their social experience) but with longstanding theories of virtue and virtue development. A virtue-theory approach to persons and relationships emphasizes their intertwining. One always needs mentors as one cultivates virtues throughout life. Relationships matter for moral virtue. One must be careful about the relationships one engages in or they can lead one astray.

What does it mean to be virtuous? Virtue is a holistic look at goodness and, for individuals, involves reasoning, feeling, intuition, and behavior that are appropriate for each particular situation. Who the person is—their feelings, habits, thinking, perceptions—matters for coordinating internally-harmonious action that matches the needs of the situation. This holistic approach contrasts with theories of morality that emphasize one thing or another—doing one’s duty by acting on good reasoning and good will (deontology) or attending to short-term consequences (utilitarianism). (Most moral systems pay attention to all three aspects but emphasize one over the others.)

The high-demand definition of goodness in virtue theory suggests that few of us are truly good. Instead, most of us most of the time act against our feeling, behave in ways that counter our best reasoning, or completely miss noticing the need for moral action. In other words, our feelings/emotions, reasoning, inclinations are not harmonious but in conflict.

Some philosophers are particularly concerned with the inconsistencies in people’s behavior—for example, a person might be honest on taxes, but dishonest in business dealings or interpersonal situations.

However, among social-cognitive psychologists inconsistency is not a surprise. Each person has habitual patterns of acting one way in certain types of situations and a different way in another type of situation. Traits like honesty don’t adhere to a person like eye color but vary from situation to situation, e.g., outgoing with friends but shy with strangers. Individuals show consistent patterns of behavior for particular types of situations (person by context interaction). Thus, a person may have learned to be honest on taxes but not yet have learned how to be honest in business or has other priorities when with family. Expertise also plays a role in that when someone is new to a domain: behavior will be inconsistent as one learns the ins and outs of best behavior. All of us need mentors to help us learn good behavior for particular situations. Virtue is a lifelong endeavor.

Featured image: Charity by Anthony van Dyck . Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Developing the virtues appeared first on OUPblog.

October 21, 2016

The Cuban missile crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis was a six-day public confrontation in October 1962 between the United States and the Soviet Union over the presence of Soviet strategic nuclear missiles in Cuba. It ended when the Soviets agreed to remove the weapons in return for a US agreement not to invade Cuba and a secret assurance that American missiles in Turkey would be withdrawn. The confrontation stemmed from the ideological rivalries of the Cold War. It raised a real threat of nuclear war but was a turning point given that, in its wake, American and Soviet leaders adopted more sober attitudes to East-West relations. The crisis accelerated the development of a more complicated, polycentric world, with some of Washington and Moscow’s respective allies, charting a more independent path after 1962 – partly because of a lack of consultation during the missile confrontation.

Practically every minute of the missile crisis has been scrutinized intensely. Crisis participants and journalists dominated the literature in the first few years, tending to laud Kennedy’s response to the Soviet challenge. Presidential aide Arthur Schlesinger described his leadership as a “combination of toughness and restraint, of will, nerve and wisdom, so brilliantly controlled, so matchlessly calibrated, that dazzled the world.” Thus, the cool, heroic Kennedy, exhibiting immaculate judgment, forced the impulsive and blustering Khrushchev to concede. Such accounts neglect to point out that Kennedy compromised by agreeing to remove US missiles from Turkey.

The 1970s and the 1980s saw a growing number of scholarly publications, including criticisms of the US administration, with questions being raised about how Kennedy appeared to obstruct quiet diplomacy in favour of public muscle-flexing. The greater openness that accompanied the end of the Cold War in the late 1980s led to growing acceptance that Khrushchev placed missiles in Cuba in part to defend the island from American aggression, which had been demonstrated by the US-sponsored attack by Cuban émigrés at the Bay of Pigs in April 1961. Several conferences in the late 1980s and early 1990s involving missile crisis veterans brought the long-overlooked Cuban perspective more to the fore. This included accounting for why Cuba’s leader, Fidel Castro, chose to accept Soviet missiles – he wanted to protect the island and to strengthen the international socialist camp. Furthermore, in the late 1980s, suspicions about the reason for the removal of the US Jupiter missiles in Turkey in 1963 were confirmed.

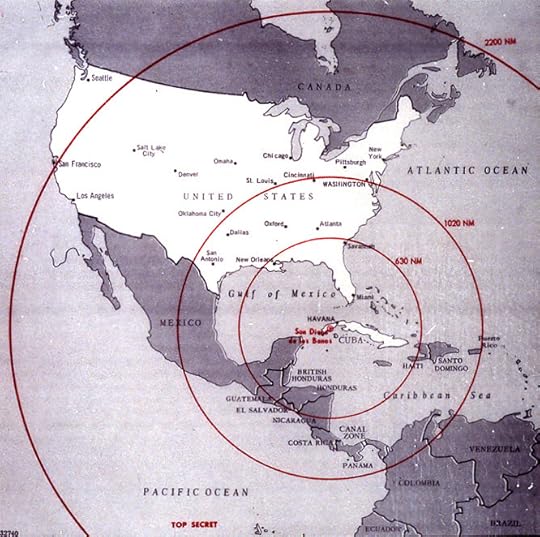

Cuban crisis map missile range by CIA. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Cuban crisis map missile range by CIA. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The 1990s saw the accelerated declassification of material from the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library, the US National Archives, and the Central Intelligence Agency. The Kennedy Library released 22 hours of secret recordings of missile crisis conversations between the President and his ‘ExComm’ colleagues. The recordings provide important insight into White House policy-making and into the views of individual advisers, revealing some to be less ‘dovish’ than was previously assumed. There are no signs of the literature of the missile crisis drying up, as shown by a fresh wave of publications on the 50th anniversary of the crisis. Why, then, decades on, does the missile crisis still merit interest?

There are at least three reasons. First, nuclear weapons were involved in both the origins and the resolution of the confrontation. Khrushchev stationed nuclear missiles on Cuba in part to boost the position of the Soviet Union in the nuclear arms race as well as to protect his ally, but both him and Kennedy resolved the confrontation peacefully in large part due to fear of how matters might escalate. The literature has emphasized in recent years how easily the missile crisis could have escalated, not least because of Soviet nuclear-armed submarines in the Caribbean. Questions about the value of nuclear weapons are particularly germane today in Britain, where Parliament has agreed recently to renew the nuclear ‘deterrent.’ Critics argue that deploying nuclear weapons is against international law because it is disproportionately destructive. Certainly, Kennedy had been sobered by a briefing in 1961 that indicated that within the first few hours of a full-scale nuclear exchange hundreds of millions of people would be dead.

Second, there are significant gaps in knowledge about the missile crisis. While there is a great deal of US documentation available, the picture is far from complete. Many military records remain classified. The quantity of Soviet material available remains relatively modest. The Cuban government has released few documents, but the recent thaw in Cuban-American relations, with President Obama’s visit to Havana in 2016, may lead to improvements in this regard. There is still much to be learned about the contributions and perceptions of countries beyond the United States, the Soviet Union and Cuba, not least from Latin American and former ‘Iron Curtain’ states. At the same time, the fact that certain areas of the missile crisis, such as the deliberations in the White House, are so well documented, provides continued opportunities to construct theoretical models to explain state behaviour and top-level decision-making.

Finally, there has long been a tendency among historians to play down the contributions of individuals, but the missile crisis suggests that this approach can be misplaced. Kennedy’s admirers were right to point out that he remained remarkably cool and composed throughout the confrontation, despite his appreciation of the danger of global nuclear war. He was willing to listen to a range of options from his ‘ExComm’ advisers, without surrendering his willingness to take decisions. Khrushchev showed more strain, but he too was gravely aware of the danger and kept open the channels of communication with his adversary. Both Kennedy and Khrushchev were willing to compromise, even at considerable political cost to themselves, and both demonstrated empathy. The question of personality and fitness for high office has been prominent recently in relation to the US presidential contest. It seems doubtful that there will be a crisis as grave as that of October 1962, but if one occurs, then one hopes that the next White House incumbent has the qualities required to navigate it safely.

Feature Image Credit: Nikita Khrushchev and Zoya Mironova at the United Nations, September 1960 by Warren K. Leffler. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The Cuban missile crisis appeared first on OUPblog.

What if they are innocent? Justice for people accused of sexual and child abuse

Many people watching the UK television drama National Treasure will have made their minds up about the guilt or innocence of the protagonist well before the end of the series. In episode one we learn that this aging celebrity has ‘slept around’ throughout his long marriage but when an allegation of non-recent sexual assault is made he strenuously denies it. His wife knows about his infidelities and chooses to believe him, but his daughter, who for years has struggled with mental ill-health, substance abuse problems and fractured relationships, seems to be troubled by memories from her childhood. As the episodes unfold, the series gives the audience chance to be judge and jury, employing whatever bits of information are available to them and, not least, their own prior assumptions about such cases.

Reporting of sexual abuse has soared in recent years, boosted by encouragement to ‘come forward’ with assurances of anonymity, developments towards mandatory reporting, and by publicity given to shocking cases. National Treasure is reminiscent of several celebrities pursued under Operation Yewtree from which there have been varied outcomes, and trials of former staff in children’s homes and residential schools for juvenile offenders, as well as of priests, doctors and others whose work has given them access to children and positions of authority. The respectability of their roles is now taken as an extra indicator that allegations are true because they have had the power to exploit those under their authority and to deceive others.

Cases of sexual abuse, especially non-recent cases, are particularly difficult because there is no crime scene or physical trace. In the absence of definitive evidence, the verdict is more likely to be influenced by the impressions made by the accused and the complainants, the relative persuasiveness of the prosecution and defence barristers, and the views that jury members already hold about what typically occurs in such cases. Individual jury members may be more emotionally predisposed to believe one party over the other, following personal experience or empathy with victims of abuse or with victims of wrongful allegations, supported by cultural narratives that they find persuasive, and depending on which form of injustice most enrages them and that they want addressed.

Cases of sexual abuse, especially non-recent cases, are particularly difficult because there is no crime scene or physical trace.

Jimmy Savile too had been described as a ‘national treasure’, as had Rolf Harris, now serving a prison sentence. The case against Savile became the exception to prove the rule that allegations of historical abuse should be believed at the expense of the ‘presumption of innocence until proven guilty’. The avalanche of complaints against Savile was quickly followed by further claims of uncovered historical institutional abuse, implicating senior politicians. True or not, these have served as signal crimes, galvanising moral panics and a political will to address them. Theresa May, then Home Secretary, announced in Parliament,

“I believe the whole House will also be united in sending this message to victims of child abuse. If you have suffered and you go to the police about what you have been through, those of us in positions of authority and responsibility will not shirk our duty to support you. We must do everything in our power to do everything we can to help you…”

Sir Keir Starmer, then the Director of Public Prosecutions, was critical of an ‘overcautious approach’ in the policing and prosecution of reported sexual offences. Explaining that ‘We cannot afford another Savile moment’ he called for a collective approach and national consensus that

“a clear line now needs to be drawn in the sand and we need to redouble our efforts to improve the criminal justice response to sexual offending.”

The collective remorse for failing to report suspicions or to believe claims of abuse in the past and wanting to recognise and learn from past mistakes has, many argue, led to over-correction and confirmation bias. Believing the victim has become a moral imperative; this includes accepting people as victims on face-value and carrying forward that implication in the treatment of them as witnesses, and as vulnerable, in need of protection. In real life, the celebrity in a National Treasure is more likely to be found guilty given the climate of public opinion. His accusers would be referred to as victim, and as the subject of police enquiries he would certainly experience huge damage to his professional and personal life. If found guilty, such serious offences would warrant a long custodial sentence.

To some extent, raising the spectre of false allegations has become contentious because it involves questioning the credibility and honesty of complainants, and requires them to give evidence that can be experienced as ‘re-victimising’. Cases in which the defendant is found ‘not guilty’ can create cognitive dissonance for victims’ advocates because it requires them to entertain the possibilities that: people may be motivated to ‘come forward’ for various reasons, such as persuasion by others, the prospect of a new identity as a survivor, and praise for being a brave person whose past failures can be attributed to abuse, or the prospect of financial compensation. Without acknowledging those and other possibilities false allegations can safely be dismissed as rare.

Maybe we also need to make more room for doubt and middle ground in some cases, instead of zealous certainty.

I’m writing this before the final episode of the television drama. Some viewers have suggested that an ambiguous ending would be the brave option, and I agree. Maybe we also need to make more room for doubt and middle ground in some cases, instead of zealous certainty. Researching this subject, I have met many people who claim they have been falsely accused, and while one can make an informed hunch based on detailed facts, narrative and getting to know the character of the person concerned, there are others where one has no idea whether the individual is innocent or guilty. If there is no physical evidence how can we know for sure? There are people who, because they live alone or are non-conformist, like Christopher Jefferies, may become suspects and be wrongly arrested and charged, but unlike the more fortunate Mr Jeffries, they cannot hope for DNA evidence to absolve them.

That black hole for proof of guilt or innocence is central to the tragedy in such cases: that we can never know for sure and the individuals are left under a cloud of suspicion, that they lied, that they did something wicked. There are other cases where we may feel much more confident but can be shown to be wrong: apparent villains may have a heart of gold; respected people in public office may have a private life that is reprehensible or shows hypocrisy. The recent revelations about the private pursuits of Keith Vaz MP and his wife’s unawareness validates arguments that people can have a side to their life or have predilections that those closest to them know nothing about. I’m acutely aware that even acknowledging such instances lays more people open to suspicion if they are accused of such behaviour, making it even more difficult for ‘actually innocent’ people to ever be believed if they are wrongly accused.

It should always be remembered that one case does not fit all. There is also a need for more public recognition of wide differences in types of sexual offences and in the degree of suffering caused, and the folly of lumping all sex offenders together as evil predators who always subject their victims to catastrophic, life-long damage.

Featured image credit: ‘Paparazzi’ by Yahoo. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post What if they are innocent? Justice for people accused of sexual and child abuse appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers