Oxford University Press's Blog, page 454

October 13, 2016

How much choice is there in addiction?

There is much that we agree about in our understanding of addiction and what can be done about the harm it causes. However, unusually perhaps for collaborators, we disagree about some important implications of suggesting a rethink of the relationship between addiction and choice.

First, what do we agree on? We agree that the relationship between addiction and choice needs rethinking. More specifically, we both reject two polarised views of this relationship – one, that addiction involves no choice on the addict’s part whatsoever, and the other, that it involves a completely free choice, just like any other choice that humans normally make. We believe that the truth lies between these unhelpful extremes and that disputes between adherents of these positions have hampered theory, research and practice in the addiction field for too long. Addicts are clearly not the automata depicted in some “disease” accounts of addiction, neither are they the free agents depicted in traditional “moral” accounts. Rather, addicts’ choice-making is disordered in some way and addiction is therefore a disorder of choice.

Gabriel:

Studies of addiction are best approached with the questions ‘What is the nature of the impairment?’ and ‘How is it acquired?’ in the lead. Questions about management, treatment, law, and social and philosophical matters follow. All of these matters can be dealt with without first deciding whether addiction is a disease, except perhaps those relating to public health expenditure and insurance.

Addicts normally use because they choose to, but the disease affects how choices are made and acted on.

I do believe that addiction is a disease. It consists in a particular type of impairment to the choice-making systems in the addict’s mind and brain. It is specific to an addict’s relationship with their substance, and cannot be accounted for in terms of any other psychological, social, or further condition. It is like a software bug in a chess-playing computer, which causes the computer to sacrifice all other goals to that of taking its opponent’s pawns. And the more successful it becomes at this, the higher it values that goal and the more its computational resources become dedicated to it.

Addicts normally use because they choose to, but the disease affects how choices are made and acted on. Addicts choose to use even when they believe that using is against their own best interests. Even when they know they are, without any sensible justification, breaking their own prior firm and thoroughly justified resolutions and even when they have a strong desire not to use, they still use. In these ways addicts often use against their own wills. And, often, either by sheer force in the moment or by relentless persistence over time, the urge to use breaks the will as easily as a wrecking ball might break a brick wall.

Nick:

There is much to agree with in what Gabriel has just said. I agree that the problem in addiction is to understand why addicts behave in ways that they are fully aware are against their best interests and why they repeatedly break prior resolutions to desist from the addictive behaviour. If we identify “will” as the resolutions made under conditions of cool and rational reflection and judgement, it is in this sense that in breaking their resolutions they act against their “will”.

Diseases are things that happen to people, over which they have little or no control and for which medical treatment is usually seen as the only resource.

However, I don’t agree that addiction is best viewed as a disease. Diseases are things that happen to people, over which they have little or no control and for which medical treatment is usually seen as the only resource. By contrast, addictive behaviour is what people do and over which they can have control. There is a huge amount of research to show that, while addiction involves involuntary, automatic urges and desires to use substances or engage in addictive behaviours, volition can always be exercised to decide whether or not those desires are complied with or resisted, however difficult this may be. Although professional or mutual aid assistance is often helpful, the public needs to be clearly informed that breaking free from addiction is possible and told how it can best be accomplished. This is less likely within a language of compulsion and disease. This is not an argument for blaming people for addictive behaviour; blame can be withheld without resorting to the language of disease. It is, however, an argument for a more enlightened societal response to addiction.

Both:

Disease or not, compulsion or not, addicts’ cognitive and emotional responses to events in their own minds and in the external world, and their consequent choices, are disordered and, typically, detrimental to their well-being. A better and more nuanced understanding of the nature of the disorder is well overdue.

Featured image credit: Cube game by blickpixel. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post How much choice is there in addiction? appeared first on OUPblog.

Presidential birthday cakes: the Ike Day recipe

On this day, sixty years ago, Republicans celebrated President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s upcoming birthday with a star-studded televised tribute on CBS. As part of his re-election campaign, Ike Day was a nationwide celebration of Ike: communities held dinners and parades, there were special halftime shows at college football games, and volunteers collected thousands of signatures from citizens pledging to vote.

A key part of the Ike Day activities involved the baking of cakes according to Mrs. Eisenhower’s special recipe. Volunteers baked thousands of cakes and delivered them to VA and Children’s hospitals around the country. And, later that evening, these cakes were served at pro-Eisenhower events in every state.

In honor of President Eisenhower’s birthday (and the campaign event it inspired), here is President Eisenhower’s Favorite Cake Recipe, as Mamie distributed it to the nation’s newspapers in October 1956.

President Eisenhower’s Favorite Cake Recipe

The Cake

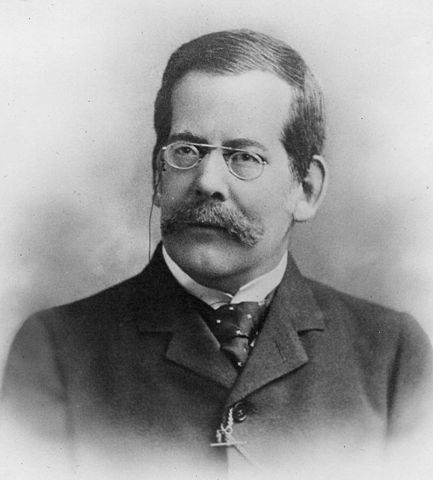

Portrait of President Eisenhower, age 65 (1956) by White House – Eisenhower Library File No. 62-53-2. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of President Eisenhower, age 65 (1956) by White House – Eisenhower Library File No. 62-53-2. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.½ cup of butter

2 cups of sugar

3 eggs

1 cup of sour milk

2 ½ cups sifted flour

1 teaspoon baking soda

1 teaspoon baking powder (rounded)

2/3s cup cocoa (dissolved in half cup of boiling water)

¼ teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon vanilla

Directions: Sift the flour, baking soda, baking powder, and salt; cream the shortening, and slowly beat in sugar, add egg yolks and vanilla. Add cocoa, add flour mixture alternately with the milk. Fold in stiffly between egg whites. Pour into two greased layer cake tins. Bake 25 minutes in 375 degree F. over.

OR: Use greased 9-inch square tin and bake 45 minutes in a 350 degree F. oven.

The Seven Minute Frosting

2 egg whites unbeaten

1 ½ cups sugar finely sifted

5 tablespoons of cold water

½ half teaspoon cream or tartar or two teaspoons light corn syrup

Few grains of salt

One teaspoon vanilla

Directions: Combine ingredients in top of double boiler; stir until sugar dissolves. Then place over briskly boiling water. Beat with egg beater until stiff enough to stand in peaks – six to ten minutes. Add vanilla, beat until thick enough to spread. During cooling, keep sides of double boiler cleaned down with spatula. With an electric beater, the process may take as little as four minutes.

Featured image credit: IMG_6311.jpg by Ryan and Sarah Deeds. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Presidential birthday cakes: the Ike Day recipe appeared first on OUPblog.

A Q&A with Kate Farquhar-Thomson, Head of publicity

From time to time, we try to give you a glimpse into our offices around the globe. Kate Farquhar-Thomson came to Oxford University Press in 1999 in search of a country life – and found it! Today finds her heading up an almost (apart from the Americas) global PR team for the Oxford University Press’s academic division, incorporating history, science, literature, music, law, medicine, politics and economics and cheese (yes really). We sat down with Kate to talk about her publishing career and what it’s like to work for OUP.

What’s the most enjoyable part of your day?

The morning which is when I get most done (and which starts with over an hour walking my dog!)

What’s the least enjoyable part of your day?

The afternoon – it is always too short!

What was your first job in publishing?

Working at Foyles Bookshop back in the Christina Foyle and Victor Stimac days, before entering publishing proper at John Calder Publishers who were then publishing William Burroughs, Sam Beckett, and Henry Miller!

Who inspires you most in the publishing industry and why?

Peter Florence, Director of The Hay Festival, who has got his work life balance just right!

What will you be doing once you’ve completed this Q&A?

Going into a meeting.

Kate Farquhar-Thomson. Used with permission of the author.

Kate Farquhar-Thomson. Used with permission of the author.Tell us about one of your proudest moments at work.

Getting Peter Atkins’ Galileo’s Finger into the Top Ten Sunday Time Best Seller list – a rare thing at OUP.

What drew you to work for OUP in the first place?

As a publicity director in London and having worked there for 13 years I wanted to move back out to the countryside for quality of life and less partying! It worked!

What is the most exciting project you have been part of while working at OUP?

Because it was different – liaising with Buckingham Palace on the visit by HRH The Queen a few years ago to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

How would you sum your job up in 3 words?

Lots of talking, and lots of schmoozing….

What is your most obscure talent or hobby?

I go beating with a pheasant shoot every week during the shooting season over winter with my spaniel Alfie.

What is the longest book you’ve ever read?

American Tabloid trilogy by James Ellroy as I used to be his publicist.

What is your favorite animal?

Donkey, I grew up with one called Neddy.

Featured image credit: Books by Mikhail Pavstyuk. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post A Q&A with Kate Farquhar-Thomson, Head of publicity appeared first on OUPblog.

What do the classics do for you?

This week, Oxford University Press (OUP) and The Reader announced an exciting new partnership, working together to build a core classics library and to get great literature into the hands of people who need it most, with the Oxford World’s Classics series becoming The Reader’s “house brand” for use in their pioneering Shared Reading initiatives.

To celebrate the new partnership between Oxford University Press and The Reader, the team based at The Reader’s headquarters in Liverpool’s Calderstones Park is shouting about classics they’ve either just discovered for the first time or love from growing up, education, or from a Shared Reading group.

Meanwhile, the team at OUP have taken a look at their treasured classics, whether they’re re-reading or finding a classic they love for the first time.

“One definition of a classic is that it is a book you can read again—or even, that it is a book that is worth reading partly so that you can re-read it. A great book, as the critic Lionel Trilling once said, is not only something you read, but also something that reads you. Sometimes you can come to a book too early, and then the book tells you ‘not just yet’; but when you return to it later it may say ‘now’s the time’. I think many people feel that way about George Eliot’s Middlemarch—described by Virginia Woolf as ‘a novel for grown-ups’. It is part of George Eliot’s conception that any person may be the moral centre of a story, and as you return to Middlemarch its different characters move in and out of the centre-ground — what felt like a story revolving around Dorothea becomes a story about Casaubon, or Bulstrode, or Mary Garth. It has something of the complex multiplicity of life itself—which must be a good definition of a classic.” – Jaqueline Norton, Senior Commissioning Editor for Literature at Oxford University Press

Jane Davis, The Reader’s Founder and Director, has chosen Cousin Phillis by Elizabeth Gaskell because of its tender, humane intelligence about the deer currents in family life.

“Over the summer I decided to fill in some ‘gaps’ in my reading—books that as an English literature graduate I was embarrassed to not have read—and decided to visit the OWC range in the very useful OUP library. After some searching I settled on the novels of Charlotte Brontë: I had never read any of her novels, and she has a relatively small body of work that I felt I could work my way through in a reasonable amount of time. A few months later, I’ve been pleasantly surprised by her lesser-known novels, The Professor and Shirley, and have been taken aback by the power of Jane Eyre and Villette. Now I have to decide who to read next!” – Ryan Kidd, Editorial Manager at Oxford University Press

Ailsa Horne, Specialist Development Manager at The Reader, has chosen Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale, as it was the first Shared Reading text she experienced.

“I’ve just enjoyed Ford Maddox Ford’s The Good Soldier. Its world is very different from mine, and I will never meet people like these. But like any book that grabs me, it has made me think about how people respond to dilemmas and challenges (and other people) that life serves up to them. In fact the distance from my world seem to sharpen my thinking, and that’s one of the beauties of reading a classic.” – Phil Henderson, Senior Marketing Manager at Oxford University Press

Alex Joynes, Project Worker at The Reader picked The Great Gatsby, by F. Scott Fitzgerald because it’s a stunning dismantling of the American Dream.

“Classics are something I re-read as a ritual. Jane Austen when I am ill (in bed with chocolates, obviously); The Turn of the Screw when under some kind of mental duress (it haunts me, and takes me away from whatever else is occupying my mind); Dubliners at Christmas (to replace different, lost rituals); previously unread classics in the summer; and new translations of old favourites in the spring. They measure out the year.” – Luciana O’Flaherty, Publisher at Oxford University Press

Andrew Parkinson, Membership Marketing Assistant at The Reader, has chosen Songs of Innocence and of Experience because he sees Blake as a visionary free of the ‘mind forged manacles’.

“At the moment, I’m rereading childhood classics with my eldest child, a daughter who is as precocious a reader as her mother once was. We tried Alice in Wonderland and The Wizard of Oz, at about two, far too soon for her which was frustrating for me. But now she’s 8, going on 9, and we started Oz again, together, and she has continued reading the Oz books on her own. We devoured The Secret Garden and The Little Princess together, cried through Black Beauty together, and were bored by Anne of Green Gables together (don’t holler, I loved them as a child and she probably will too when she’s a bit older).

I don’t know if my daughter and I will continue to read aloud together as she grows older, but if the time we have to read together is growing shorter the classics feel all the more relevant to the education of a modern child. I’m looking forward to Emma, Wuthering Heights, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, and Treasure Island and all of the questions about history and time that they bring to the forefront of our conversations from day to day.” – Sarah Russo, Head of Publicity and Trade Marketing at Oxford University Press

Eamee Boden, Calderstones and People Assistant at The Reader, sees herself and Jane Eyre’s character as having lives that are parallel to each other.

“I love it when I have time to sit down with a classic book, because they remind me of what a rich history of Literature there is out there, and how fortunate we are to be able to immerse ourselves in it, or dip in and out, at will. Two longstanding favourites of mine are Madame Bovary and (quite different) the extraordinary Moby Dick.” – Ellie Collins, Senior Assistant Commissioning Editor for Literature at Oxford University Press

Chris Lynn, Volunteer Coordinator at The Reader, has chosen The Tempest because it’s his favourite play, and because it made Shakespeare’s works feel accessible to him.

“I read classic literature because it enriches my understanding of my favourite contemporary novels—if I wasn’t familiar with the mythology of 1001 Nights (and its Orientalist interpretations/“translations” e.g. Arabian Night’s Entertainments), I wouldn’t love Salman Rushdie’s Two Years, Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights nearly as much as I do. (Hint: the allusions begin with the title.) Reading Donna Tartt’s The Secret History without having read Homer and Plato just wouldn’t be as much fun, and how can you read The Sound and the Fury if you haven’t read Macbeth? Classic literature helps me make sense of my favourite books, and my favourite books help me make sense of the world.” – Lucie Taylor, Publicity Assistant at Oxford University Press USA

Communications Intern at The Reader Lauren Holland has picked the The Yellow Wall-Paper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman as an essential feminist text concerning women’s mental and physical health.

“In school I was a reluctant classics reader, and the seemingly never-ending discussion of Goethe’s Faust (though only Part One) didn’t particularly help that matter. Growing up in Germany and learning English, Shakespeare was a compelling, if largely confusing, teacher but he opened doors to other English writers, and soon I was willingly reading the usual suspects (Austen, the Brontës, and a little Dickens). Over the years and the course of an English literature degree I’ve branched out to other writers and shores, and Kafka’s stories and Ibsen’s plays have become favourites. While their stories were created in different centuries, they still feel relevant and help create an understanding of the past.” – Kim Behrens, Associate Marketing Manager at Oxford University Press

Martin Gallagher-Mitchell, The Reader’s Marketing and Communications Coordinator, has chosen The Woman In White by Wilkie Collins as the first novel he read with his Shared Reading group.

A haiku from Niko Pfund, President of Oxford University Press USA:

Why classics, you ask?

Commune. Enlighten. Learn. “On-

ly connect”— E.M. Forster

Featured image: Book Read Relax by condesign, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post What do the classics do for you? appeared first on OUPblog.

October 12, 2016

Blessing and cursing

Strangely, both bless and curse are rather hard etymological riddles, though bless seems to pose less trouble, which makes sense: words live up to their meaning and history, and bless, as everybody will agree, has more pleasant connotations than curse. The root of the riddle consists in the fact that both verbs, even though their ties with the Christian ritual arouse no doubt, are isolated or almost isolated in English. One could have expected such words to have obvious Latin roots, like German segnen, Dutch zegenen, and so forth (all going back to Latin signāre “to make a sign”). Yet a short note on the isolation of bless is perhaps due here: Old Icelandic had blessa and bleza (the latter pronounced as bletsa; Modern Icelandic blessa), but this verb was borrowed from Old English. More suggestive is perhaps the existence of Westphalian (that is, Low German) blessen “to put a mark on one’s forehead” (for instance, on Ash Wednesday), but it is unclear whether the verb is native there.

God bless you!

God bless you!Minsheu, our earliest English etymologist, cited Latin benedictare “to bless” (literally, “to speak well”), but the entries in Minsheu’s dictionary (1617) are a mixture of possible congeners and synonyms in several languages, so that one often wonders what to do with them. After benedictare, he listed German begehren “to covet, long for,” and there is no way of knowing whether he glossed bless as benedictare and begehren or looked upon both as related to bless. This fact would not have been worth mentioning if about three centuries later, in 1923, Friedrich Kluge, who had no access to Minsheu and who would hardly have consulted such a source even if he had known about its existence, derived Old Engl. bledsian directly from Latin benedictare (he opened his note with the following statement: “No etymologist has probably made bold to equate Engl. bless and benedictare”). The phonetic part of Kluge’s equation is weak. He uncovered a few cases of n becoming l in Germanic and elsewhere, but the difference between the sound shape of benedict(are) and bledsian is too great to support his hypothesis.

Apart from the probably nonexistent benedictare—bless connection, for many years lexicographers attempted to trace bless to blithe and bliss. Blithe “joyous,” when not a woman’s name (then it is spelled Blythe), is a rare, but hardly obsolete, word in Present Day English. Its cognate in Gothic meant “kind-hearted”; in Old Norse “pleasant,” and in Old High German “friendly.” Possibly, the initial meaning of the adjective referred to some color (pale?). The origin of several other old words beginning with bl– is also unknown. We don’t have enough evidence for ascribing an obvious sound symbolic value to them (for some ideas on initial bl– see my second post on the origin of the English adjective blunt: surprisingly many bl-words denote bad things). However, blessing and bliss are not bad, so that in this case sound symbolism provides no help.

Does bless go back to the sacrifice of such an innocent creature? Not bloody likely, as Eliza Doolittle would put it.

Does bless go back to the sacrifice of such an innocent creature? Not bloody likely, as Eliza Doolittle would put it.The Old English forms of blithe and bliss were blīþe and bliss ~ blīþs respectively, while bless appeared in our earliest texts in the forms blētsian, blēdsian, and blœdsian (also with a long vowel in the root; þ had the value of th in Modern Engl. thin). The similarity between, let us say, blēdsian and blīþs is significant, though the change of ī to ē in the root cannot be accounted for. Yet even Skeat accepted this derivation. Let it be remembered that Skeat’s etymological dictionary appeared in fascicles (installments), and bless was, naturally, in the first one, dated 1879; the date on the bound volume of the first edition is 1882 (Skeat worked fast). As ill (or good?) luck would have it, in 1880 Henry Sweet, a great English philologist, published his etymology of bless. He derived the word from the form that, according to him, sounded like blōdisōn and had the root of the noun blood (Old Engl. blōd). “The original meaning of bless,” he explained, “was therefore ‘to redden with blood’, and in heathen time it was no doubt primarily used in the sense of consecrating the altar by sprinkling it with the blood of the sacrifice. Compare the Old Icelandic rjóða stalla í blóði ‘to redden the altar with blood’.”

This is an excellent etymology, though such an experienced man as Sweet should not have added, seemingly for good measure, the parenthetical phrase no doubt. In the corrections to the first edition, Skeat wrote about his own entry: “The etymology is entirely wrong.” He accepted Sweet’s idea, and so did almost everyone else. But from early on (beginning with Minsheu!), bless has been compared with the Germanic verb blōtan “to sacrifice.” Jacob Grimm, in his book on Germanic mythology, was not sure whether bless is related to this verb or to the cognates of blithe, and from time to time notes and even full-fledged articles appeared in defense of blōtan as the etymon of bliss. Murray knew both views but preferred Sweet’s solution. The post-Sweet publications were in German and Swedish, and in the English-speaking world they made no stir, especially because of the authority of the OED. Yet I would like to quote an enigmatic statement from the anonymous 1914 review of Henry Sweet’s Collected Works (Athenæum, July 18, 1914, p 70). Sweet died in 1912, and Henry Cecil Wyld brought out a volume of his papers in 1913. Among other things, the reviewer wrote: “On p. 217 we find an excellent example of Sweet’s phonetic method in his derivation of bless from blood, which, odd as it seems, is everywhere accepted as correct.” Odd as it seems! Apparently, the reviewer found the “excellent example” all wrong.

Henry Sweet (1845-1912). The founder of English philology in England, he was one of the prototypes of Eliza’s Henry Higgins. The other one was the famous phonetician Daniel Jones. Sweet was described as a rather dour man.

Henry Sweet (1845-1912). The founder of English philology in England, he was one of the prototypes of Eliza’s Henry Higgins. The other one was the famous phonetician Daniel Jones. Sweet was described as a rather dour man.In 1958, Hermann Flasdieck, an outstanding Germanic and English scholar of the twentieth century, published an article in which he supported the derivation of bless from blōtan. Of necessity, I have to skip the numerous phonetic details that Flasdieck discussed and will confine myself to saying that his analysis is fully persuasive. Several leading German etymologists accepted it without any reservations, and so did Jan de Vries in his Old Icelandic dictionary, but the authors and editors of our “thick” dictionaries, including The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology, copied their entries from the OED and Sweet.

One small hitch remains in Flasdieck’s exemplary essay. The origin of blōtan is highly disputable. Is this verb related to blood? If it is, Sweet will emerge partly vindicated. But for the etymology of bless the early history of blōtan is of secondary importance. The real trouble was clear to Kluge, though no one seems to have paid attention to his statement. Whether from blood or from blōtan, bless ends up in our scholarship as a relic of pagan practices. Christian missionaries usually made great efforts to coin names for the new religion that evoked no associations with traditional rites. Since they had the verb benedictare at their disposal, why did they stick so stubbornly to one of the most pagan words of the old ritual (and it meant “sacrifice,” not “bless”!). Did the proximity of bliss in all the Germanic languages save blōtan from extinction? Whatever the answer, since the missionaries tolerated this verb, we will too and conclude that in Anglo-Saxon England bless was derived from it rather than from blood.

Images: (1) “sneeze” by Tina Franklin, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr. (2) “The Sacrificial Lamb” by Josefa de Óbidos, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) “Picture of linguist Henry Sweet” Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. Featured image: Female Pastor by Andrys Stienstra, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Blessing and cursing appeared first on OUPblog.

The power of volunteering: you make me happy and I make you happy

Millions of people across the world work for voluntary organisations and invest their abundant energies into helping their communities. Historically, establishments of voluntary organisations date back to at least the nineteenth century, when some of the world’s largest voluntary organisations, such as the Red Cross, were established to help people in need for free. To date, volunteer work remains a popular activity among the public worldwide. The World Giving Index indicates that, globally, 21% of individuals volunteered in 2013, with Americans recording the highest volunteer participation rate of 44% in developed countries.

Why do people work for free in the first place?

Some argue that people volunteer because they enjoy an increase in the well-being of others, while others argue that people volunteer because the act of giving in itself makes them happy, among others. In fact, statistical evidence shows that, relative to non-volunteers, volunteers are on average happier, more satisfied with their lives, less depressed, and report better health. However, this evidence doesn’t necessarily imply that volunteer work “causes” to improve the well-being of volunteers. It could be the case that those who are happier and healthier may be participating in volunteer work in the first place. To address this point and investigate whether volunteer work causes an increase in the well-being of volunteers, Meier and Stutzer studied the effects on well-being of an abrupt decline in volunteer opportunities in the East Germany. After the German reunification, many organisations, such as sports clubs and publicly owned firms, which used to provide volunteer opportunities collapsed, and a large number of people were forced to stop volunteering. Based on a comparison of people who lost their volunteer opportunities and those who didn’t, the former was found to experience a decline in life satisfaction.

What about the benefits to the recipients of volunteer service?

An attempt is made to answer this question by studying the consequences of an unexpected increase in the number of volunteers following an earthquake in Japan. In 1995, the city of Kobe was hit by an earthquake of a magnitude of 7.3 which took away the lives of over 6,400 people. Shortly after the earthquake, a large number of volunteers gathered in the disaster area to provide emergency support. Roughly 1.4 million people volunteered over the year following the earthquake, approximately 70% of whom were volunteering for the first time. The large-scale volunteer activities following the earthquake were broadcast as a new social phenomenon in Japan, and subsequently served to popularise volunteer activity, as is demonstrated by the fact that the year 1995 is called “volunteer gannen”, meaning “the starting year of volunteerism.”

Volunteers are on average happier, more satisfied with their lives, less depressed, and report better health.

Focusing on volunteers who provide the elderly with informal care, such as visits to homes for a chat and assistance with daily tasks, it was found that the number of volunteers considerably increased in the municipalities hit by the earthquake. In contrast, other municipalities which were not damaged didn’t experience such a sharp increase. Based on a comparison of elderly mortality between the municipalities that recorded no or little loss of life because of the earthquake but experienced a sharp increase in the number of volunteers, and the nearby municipalities that weren’t hit by the earthquake, the voluntary provision of informal care was found to reduce elderly mortality. Supplementary analysis suggests that the reduction in mortality was likely caused by an improvement in general health conditions of the elderly.

These findings have important policy implications for societies facing growing needs of healthcare for their ageing population. Europe, where the percentage of population aged 65 or older is projected to almost double to approximately 30% from 2010 to 2050, is a case in point. These findings suggest that governments facing ageing populations can consider encouraging volunteer work as a way to provide the elderly with support. To the extent that volunteering for the elderly improves health conditions of care recipients, it potentially helps mitigate an increase in public health spending. In addition, aside from helping the elderly, volunteers may improve the efficiency of the healthcare sector. Volunteers potentially help free up the time of more formally-trained (paid) workers, who can then reallocate their time to perform tasks requiring their special skills. For example, by leaving tasks that don’t need specialised health-care skills to volunteers, such as visiting the elderly and providing them with daily support, more trained workers, such as social workers, may be able to devote their time to counsel the elderly who lost independence because of ill health, for instance.

King’s College Hospital in London is an example of hospitals that work closely with volunteer workers, each of them devoting at least three hours a week for six months. Volunteers visit wards for a chat, run errands for patients, and help patients settle in at home after a hospital stay to help patients feel comfortable in their difficult times. Ward visitor, Chris Baldwin, who has been volunteering for the hospital over 25 years says, “I meet the most amazing people and I feel it is a privilege to be able to help them. I can’t recommend being a volunteer at King’s highly enough – it makes me get up in the morning as it is so rewarding!”

There appears to be a huge potential of volunteering still to be used in society to make both who give and receive happier.

Featured image credit: Hands aged elderly by Gaertringen. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The power of volunteering: you make me happy and I make you happy appeared first on OUPblog.

Sex, Pope Francis, and empire

Pope Francis has missed the Good News, the gospel, of sex.

Pope Francis recently said in the former Soviet Republic of Georgia, and on several occasions over the last year, that Western nations are exporting an idea that gender is a choice. Pope Francis asserts that this “gender ideology” is the enemy of the family.

Here, the pope disappoints many in America and Europe, who hoped that he might free Catholics from the heritage of homophobia and repression of women that has been protected and promoted for millennia by the Roman Catholic Church.

But as Western cultures have revealed in the last few decades, those who choose their genders are not enemies of the family. Gay and transgendered men and women now raise children in great numbers, sometimes through medical insemination and sometimes through adoption, often in better circumstances than children raised by straight couples. There is no reason for anyone to think that any real God disapproves of these families.

Christian leaders in the Anglican tradition, in the United Church of Christ, and other churches around the world have stood with Christians who want to have families free from Bronze Age laws. Those laws, which first appeared in the biblical book of Leviticus, prescribe death by stoning for homosexual men, “stubborn rebellious sons,” and those who perform worship before statues (as Pope Francis and other Roman Catholics do).

Pope Francis in a meeting with President Christina Fernandez de Kirchner of Argentina in the Casa Rosada. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Pope Francis in a meeting with President Christina Fernandez de Kirchner of Argentina in the Casa Rosada. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Pope Francis argues that tolerance of gender choice results from a Western imperial ideology, exported to nations that would otherwise follow natural law. Here, he joins forces with Russian nationalists like Vladimir Putin, Islamist thinkers like Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the former president of Iran, and some African evangelicals.

No doubt, the West has exported many bad ideas. But in sex, the West has achieved a synthesis that is sweeping the world.

Sex began as good, with the rest of creation, according to Genesis 1. Sex fell into corruption with human culture, in original sin, which also appears in patriarchy and oppression (Genesis 3). Sex can be redeemed through ecstatic experience, as in the Hebrew prophets and the New Testament experience of God’s spirit. Evangelical Christians, especially African-Americans, helped to redeem sex in the United States. Now, American culture embodies an ethic of sexual pleasure in which sexual and religious experience have become one. This is the fulfillment of natural law, which looks beyond gross anatomy to the union of body and spirit.

Many in the United States, Europe, India, China, Africa, and the Middle East are realizing this insight today, and reacting for and against it.

Pope Francis needs to recognize it as well.

Featured image credit: Main facade of Saint Peter’s Basilica, Rome, by Alvesgaspar. CC BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Sex, Pope Francis, and empire appeared first on OUPblog.

October 11, 2016

Virginia Woolf: author, publisher, feminist

As a young woman, Virginia Woolf toured London’s National Portrait Gallery and grieved to find that almost all the portraits in the collection were of men. Woolf was so resentful that she later refused to sit for a drawing commissioned by the gallery, seemingly renouncing an opportunity to add her own portrait to its walls. One hundred years later, in the summer of 2014, I found myself at the museum touring “Virginia Woolf: Art, Life and Vision,” a special exhibition devoted entirely to the woman who renounced this very same gallery because of her feminist beliefs.

As the United States prepares for its very first presidential election featuring a woman on a major party’s ticket, I am especially reminded of Woolf, a feminist decades ahead of her time. Through both her writing and her social beliefs, Virginia Woolf gave voice to women’s experiences long before “the wage gap” was common jargon. While Woolf’s feminist ideals are frequently remembered through her essays, especially the definitive A Room of One’s Own, her progressive aims subtly permeate even her earliest fiction.

Jacob’s Room, Woolf’s third novel and her first definitively experimental body of writing, explores the coming of age of protagonist Jacob Flanders during the early twentieth century. Woolf’s decision to tell Jacob’s story predominantly through the perspectives of the women who know him, rather than Jacob’s own narration, transforms a traditional character study into a commentary on the predominance of women in the life of a male character. The looming advent of the First World War features heavily throughout the story, and Woolf’s focus on the war’s effect on the private domestic home front was at that time so rare that other authors — even women— criticized her for not covering the action and politics of war more overtly. The novel further elaborates on the impact of the war at home by commenting on ties between patriarchal society and militarism, never directly blaming a chauvinistic culture for the war but still subtly laying the foundation for examining the potential connection. These themes later served as partial inspiration for Three Guineas, Woolf’s essay on war and the role of women in a war-torn patriarchy, and The Years, the last Woolf novel released in her lifetime.

The publication of Jacob’s Room in October of 1922 was especially significant to Woolf as it was the first of her own novels to be released by her very own Hogarth Press. Both Virginia and her husband Leonard Woolf enjoying book printing as a hobby, and when they bought their own printing press to keep in the dining room of their residence at Hogarth House, they simultaneously founded their own publishing house in 1917. Female business owners were few and far between in early and mid-century England, but Woolf vigorously sought printing success and Hogarth Press went on to publish works by T.S. Eliot, Dostoyevsky and Sigmund Freud. Woolf even commissioned her sister, Vanessa Bell, to create the cover artwork for numerous Hogarth Press publications; Woolf herself remained a co-owner of the press for most of her life, as well as its most widely published female author.

At the National Gallery’s exhibit I viewed several Hogarth Press first editions of Woolf’s books, and I remember feeling awed by this woman’s commitment to the pursuit of her art and her ethics — even as she lived in a time with few fundamental rights, and fewer critical accolades, for women. As the long fight for gender equality continues, I am grateful for all the barriers Virginia Woolf conquered, as a writer and as a woman, over one hundred years ago.

Featured image: “Portrait of Virginia Woolf” by George Charles Beresford, Public Domain via Wikimedia.

The post Virginia Woolf: author, publisher, feminist appeared first on OUPblog.

10 things Birth of a Nation got right about Nat Turner

On Sixty Minutes, when filmmaker Nate Parker was asked if Birth of a Nation was historically accurate, he noted, “There’s never been a film that was 100% historically accurate. That’s why they say based on a true story and doesn’t say, ‘A true story.’” Hollywood may not be the best place to learn one’s history, but here are ten things that the new movie Birth of a Nation got right about Nat Turner’s revolt:

Nat Turner was a literate slave. While most slaves were illiterate, Nat Turner could read. We do not know exactly how he learned to read. When he was recounting the story of his life, he saw it as a miracle that he learned to read without being taught, but Thomas R. Gray, the man who transcribed Turner’s confession, explained his literacy in the same way that Nate Parker did: he had been taught by his owners.

Nat Turner had a family, including parents, a wife, and a child. As Turner told his story to whites, he even recalled a “very religious” grandmother, to whom “I was much attached.” Unfortunately, we do not know as much about his family as we would like. We do not even know Turner’s wife’s name: some historians think that her name was Cherry while others think that her name was Mariah or even possibly Fanny. He also had a child, although that child was not a girl, as Parker imagined him, but a boy named Redic.

Nat Turner’s father escaped slavery. In a dramatic moment in Birth of a Nation, Turner’s father is forced to run away and is never seen again. We actually know nothing about the circumstance of Turner’s father’s escape, but Turner believed his father had escaped “to some other part of the country.”

Nat Turner was a religious man. According to the Confessions, Nat Turner recalled “devoting my time to fasting and prayer.” He believed that “The Spirit that spoke to the prophets in former days” spoke to him as well.

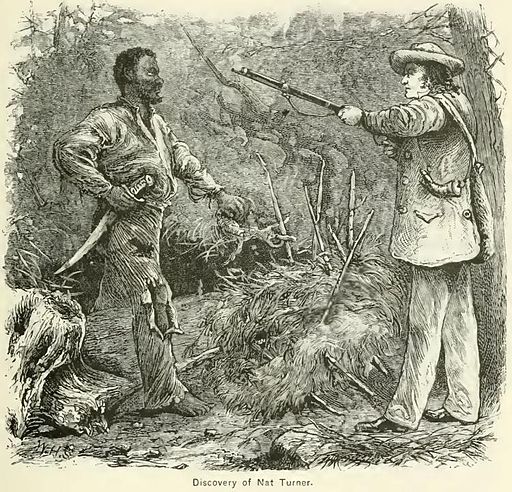

Image Credit: Discovery of Nat Turner: wood engraving illustrating Benjamin Phipps’s capture of w:Nat Turner (1800-1831) by William Henry Shelton. Public domain via Wikimeda Commons.

Image Credit: Discovery of Nat Turner: wood engraving illustrating Benjamin Phipps’s capture of w:Nat Turner (1800-1831) by William Henry Shelton. Public domain via Wikimeda Commons.Nat Turner baptized a white man. Turner’s confessions describe him baptizing a white man, Ethledred T. Brantley. Brantley and Turner requested that a church baptize them both, but “the white people would not let us be baptised by the church.” So both Turner and Brantley were baptized together “in the sight of many who reviled us.”

Nat Turner believed that God spoke to him through prodigies including the eclipse of the sun. Turner interpreted unusual appearances in the natural world as signs from God. As portrayed in Birth of a Nation, Turner “discovered drops of blood on the corn as though it were dew from heaven”. He also saw signs in the sky and hieroglyphs on leaves. Birth of a Nation suggests that an eclipse of the sun was the sign that set the revolt in motion. Actually, the eclipse, which happened in February, was the sign that led Turner to begin telling others about the revolt. The plan itself was set in motion by a different sign, a strange appearance of the sun. Turner never described this second sign, but on August 13 people up and down the East Coast of the United States described the sun’s unusual appearance, a woman in Richmond describing it “as blue as any cloud you ever saw.”

Nat Turner called his master a kind master. Unlike the movie, Turner had multiple masters. When the revolt began, Turner was owned by Putnam Moore, a nine-year old, but since January of 1830, he and Moore both lived with Moore’s stepfather Joseph Travis. Turner described Travis, the first victim of the revolt, as “a kind master.” He then added, “in fact, I had no cause to complain of his treatment to me.” Turner believed that the fight for freedom was righteous independent of the master’s behavior.

The rebels were on their way to Jerusalem. While the name of the town toward which the rebels headed, Jerusalem, sounds like it came out of central casting, the county seat for Southampton was actually called Jerusalem. You won’t find Jerusalem on a map if you look. The town changed its name to Courtland in 1888. While the moviemakers are right about the rebels’ goal, they incorrectly suggest that the rebel army made it to Jerusalem. The rebels were defeated in a battle at James Parker’s place about 3 miles southwest of the town.

Nat Turner remained at large for a significant amount of time after the revolt. The revolt was suppressed quickly. The rebel army was dispersed by Tuesday 23 August 1831 and most of the rebels were killed or captured at that time. But Turner himself disappeared for more than two months and some whites began to think that he had escaped. Eventually the governor issued a reward for his capture and he was spotted first by a slave then by a white near where the revolt began. Although Birth of a Nation portrays Turner’s ultimate surrender differently, Turner was captured by Benjamin Phipps on 30 October 1831 near where the revolt began.

Nat Turner kept his cool on the day that he was hanged. There are only two accounts of Turner’s death on 11 November and they do not always agree about what happened. (One report described an “immense crowd” but the other noted that “there were but few people.”) But they do agree that Turner kept his cool. One reported that Turner “exhibited the utmost composure during the whole ceremony;” the other noted that Turner “even hurried the executioner in the performance of his duty.”

Featured Image Credit: annual solar eclipse by Takeshi Kuboki. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post 10 things Birth of a Nation got right about Nat Turner appeared first on OUPblog.

High-fructose honey and the diet of urban bees

Mysterious red honey began to appear in the hives of New York City bees in the summer of 2010. At first, beekeepers thought their bees were foraging on some strange plant, possibly sumac. But after more beekeepers began to find red honey in their hives, they decided to get their honey tested. As it turned out, the honey was filled with Red Dye No. 40, and instead of foraging on flowers, the bees had been collecting sugar syrup from a Maraschino cherry factory in Brooklyn.

The story of New York’s red honey struck a chord with those already concerned about honey bee health. Bees have been hit hard by a host of challenges ranging from parasitic mites to neonicotenoid pesticides—but could red honey be another sign of bee decline? Could artificial flavors and chemicals in human foods be toxic to bees? Could we be at risk if we eat “local honey”?

Rooftop hive at the American Tobacco Campus in Durham, NC, managed by Bee Downtown. Photo by Lauren Nichols and used with permission.

Rooftop hive at the American Tobacco Campus in Durham, NC, managed by Bee Downtown. Photo by Lauren Nichols and used with permission.As people were asking questions about New York’s bees, my lab group was studying another insect in New York—ants. Over 8.9 million people live in New York, but there are at least 16 billion ants. That means for each person living in New York there are nearly 2,000 ants. In an area that is almost 90% concrete, how could so many ants survive? The secret, we thought, might lie in what was happening with New York’s bees. Rather than feeding on dead insects and other “natural” foods, we guessed ants might be switching to human foods.

The average person living in a city produces 1,000 pounds of garbage each year, and of that, 15% is food waste. With over half the world’s population now living in cities, this amounts to 250 million tons of food thrown out in cities each year, which represents a massive potential resource for urban animals. We found that much of this food in New York was making it into urban ant colonies. This was especially true in the most urban areas of the city, like the sidewalks running down Broadway. A follow-up study found that ants living on Broadway alone consumed the equivalent of 60,000 hotdogs per year—more than city rats or birds consumed in the same area.

Clint Penick. Photograph by Lauren Nichols and used with permission.

Clint Penick. Photograph by Lauren Nichols and used with permission.But what about urban bees? Anecdotes about red honey aside, no serious investigation had been carried out on the diet of urban bees. Over the last decade, cities began to change local ordinances that had previously outlawed beekeeping inside city limits, and urban beekeeping has become increasingly popular. Along with backyard chickens and rooftop gardens, urban beekeeping has become a major part of the local food movement. In fact, the red honey discovered in New York was intended for a local restaurant until it turned out to be recycled sugar syrup. Despite growing interests in urban bees, there was still no clear answer as to whether bees were sticking to flower nectar or finding new sugar sources in cities.

Using the same techniques we used to study ants in New York, we began studying the diet of bees in Raleigh, North Carolina. Human-produced sugars, like sugarcane and high-fructose corn syrup, have a characteristic carbon isotope signature that can be used to determine if bees are feeding on flower nectar or, say, someone’s leftover soda. Bees in rural areas should only have access to flower nectar, but if city bees are feeding on human food sources, then their carbon isotope signature should show it.

To our surprise, we found no difference in carbon isotopes between bees living in downtown Raleigh and those living outside the city. In both habitats, bees were sticking to flower nectar and largely avoiding human sugar sources. This is good news for urban beekeepers and people who buy local honey, and it also shows that urban flowers play a major role in maintaining healthy pollinator populations in cities.

In the future, we plan to partner with urban beekeepers in larger cities, like New York and Tokyo, to see if bees are still able to sustain their colonies on local flowers. Will we find bees similar to those in Raleigh, or will we uncover new mysterious shades of honey inside the hives of big-city bees?

Featured image credit: “Bee foraging on flowers outside lab at NC State” by Lauren Nichols. Used with permission.

The post High-fructose honey and the diet of urban bees appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers