Oxford University Press's Blog, page 455

October 11, 2016

5 things you always wanted to know about interest groups

Virtually no government policy gets enacted without some organized societal interests trying to shape the outcome. In fact, interest groups – a term that encompasses such diverse actors as business associations, labour unions, professional associations, and citizen groups that defend broad interests such as environmental protection or development aid – are active at each stage of the policy cycle: they try to influence which policies make it onto the political agenda; which ones are adopted at the end of the legislative process; and how the policies adopted get implemented. They even turn to courts to overturn laws or to establish a certain interpretation of laws. Undoubtedly, then, interest groups play an important role in democratic political systems, making research on interest groups highly relevant. Here are five key insights:

Many more business groups than citizen groups are politically active in basically all political systems. In different countries and at different levels of governance (the subnational level, the national level, and the international level) around 50% of the interest groups that engage in political activity represent business interests. This includes not only broad business associations and chambers of commerce, but also sector-specific associations such as those representing firms in the chemical sector or the financial industry. When adding firms that lobby on their own, the dominance of business interests becomes even more pronounced, at least in purely quantitative terms.While at first this business advantage, in terms of mobilization, may appear alarming, its normative implications are actually ambiguous. On the one hand, it can indeed be seen as undermining the democratic principle of one person, one vote. Clearly, not all interests have an equal chance of being heard by policymakers. On the other hand, it may simply be that business interests have to be more active because they have a greater and more direct stake in many policies. The unequal mobilization may even be an indication of a legislative agenda with many policies that run counter to key business interests.

Most interest groups are small and resource-poor, independent of the measure we use to capture size and resources. Clearly, there are some interest groups that violate this rule. The Confederation of British Industry (CBI), for example, has offices in several countries around the world, a considerable number of employees and a large number of members. As such, however, it is a stark outlier in the interest group population. Most interest groups only employ a small number of staff, which makes it impossible for them to focus on several policy debates at a time. They also have a severely limited budget and a relatively small membership. Across several European countries, for example, less than a third of all business associations have more than 100 firms as members. The small size of many interest groups also means that they are constantly threatened in their survival. In fact, there is a steady turn-over in the population of interest groups, with some groups disappearing and others being created.

Mount Yale Board Room by Chris. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Mount Yale Board Room by Chris. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.Given their relatively small size, it is also no wonder that most interest groups are quite specialized. Most groups focus on just a few policy areas, allowing them to develop expertise on the issues that they work on, despite their resource constraints. Specialization in specific niches also enhances the chances of survival of interest groups. A few policy areas, however, see a particularly large amount of interest group activity: key among them are environmental, research, employment, and education policy. Business associations, citizen groups, professional associations, and labour unions all consider these as areas of high importance for their work.

Many interest groups are active beyond the national level. Activity in international organizations – in Europe, and in the European Union in particular – has become essential for most interest groups. Interest groups thus need to interact with groups from other countries and get acquainted with how to do lobbying in different institutional contexts. Again, this applies not only to business associations, which are known for their international linkages, but also to citizen groups, professional associations, and labour unions. The internationalization of business associations, however, exceeds that of other types of interest groups. This internationalization is made possible by a membership that has the capacity to closely monitor the activities of the organization, even if these activities take place abroad, whereas citizen groups often need to focus on issues that are close to the citizens that support them.

Business associations adopt a lobbying style that is quite different from the approach taken by other types of groups, especially citizen groups. They have a relatively greater focus on providing information to decision-makers, whereas citizen groups concentrate relatively more on activities aimed at mobilizing the public. Business interests also enjoy better access to decision-makers (especially the executive) at different levels of governance and in different political systems. There is little evidence, however, that business interest groups can easily translate this advantage in terms of access into greater influence on policy outcomes. In democratic political systems, decision-makers have an incentive to respond to public opinion. And to the extent that citizen groups can shape public opinion, they can exert significant influence on public policies. The success of the campaign against the planned Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) in Europe is an illustration of this point. Business interests have had an advantage in terms of access to decision-makers on this issue; but the public pressure created by citizen groups has led to a considerable shift in the stances of the European Commission, the European Parliament and some national governments.

In short, interest groups play an important role in democratic politics. Nevertheless, they are less powerful than often portrayed in popular accounts. They are relatively small and resource-poor, and even groups that gain access to decision-makers often fail to get their way on policies that are dear to them. Interest group politics thus is neither the main source of, nor the best cure for, the ills of contemporary democracies.

Featured image credit: Modern financial office building by Pawel Pacholec. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post 5 things you always wanted to know about interest groups appeared first on OUPblog.

Ten fun facts about the theremin

Have you ever wanted to control sound waves? Or spook your friends with an eerie melody? Are you a hip electronic music producer, who wants to embrace the ghoulish spirit of vintage electronica? If you answered yes, you might want to invest in a theremin. This instrument is controlled by slight hand movements. The hand always lingers and it never makes contact with the instrument itself. The sound is controlled by movements in space, producing a visual performance and auditory experience sure to send chills up your spine. Here are ten fun facts about the theremin, OUP’s eerie instrument of the month:

Image Credit: Lev Termen playing his instrument, US public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Image Credit: Lev Termen playing his instrument, US public domain via Wikimedia CommonsThe theremin is a ‘space-controlled’ electronic instrument that was invented by Lev Sergeyevich Termen in the early 20th century, which makes it one of the earliest electronic instruments and the first successful one. If you’re into vintage electronica, we suggest looking into Lev’s orchestral demos.

The theremin is monophonic, meaning it only uses one channel of transmission to create sound.

The theremin is similar to a radio receiver. It has two antennae: one on the right that is vertical and one to the left that is loop-shaped.

To play the theremin, you cannot touch it. The single pitch comes from its loudspeaker and depends on how far away the performer keeps their right hand from the instrument’s vertical antenna.

The volume is controlled by a similar process. As the left-hand pulls away from the horizontal loop antenna, the amplitude of sound increases.

The first orchestral work with a solo electronic instrument was Andrey Pashchenko’s Simfonicheskaya misteriya (‘Symphonic Mystery’) for theremin and orchestra, which received its first performance in Leningrad on 2 May 1924. Lev Termen was a soloist.

The theremin was popular in science-fiction films. The first film the instrument appeared in was a Soviet science fiction called Aelita: Queen of Mars (1924).

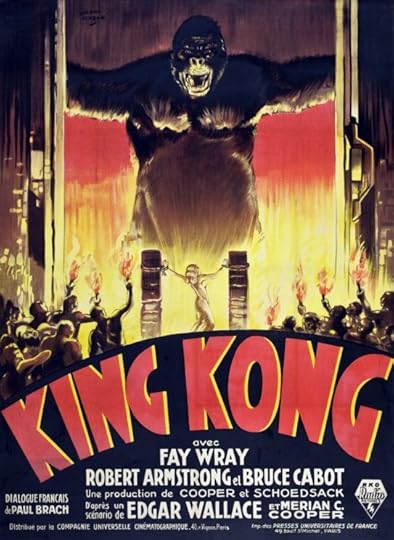

The theremin was quickly picked up by Hollywood film composers, appearing in Max Steiner’s score for King Kong (1933), Franz Waxman’s score for Bride of Frankenstein (1935) and in Bernard Herrmann’s score for The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951).

Image Credit: King Kong French Movie Poster, 1933, RKO Radio Pictures; Roland Coudon, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Image Credit: King Kong French Movie Poster, 1933, RKO Radio Pictures; Roland Coudon, Public Domain via Wikimedia CommonsThe theremin’s pop culture stardom was not limited to science fiction movies. The instrument was used in the Beach Boys’ song Good Vibrations (1966).

The theremin is a close instrumental relative to the terpsitone, which is a dancefloor that responds to dance movement with electronic sound.

Image Credit: Ash Nowak, Dorit Chrysler, Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, taken 18 January 2015, (CC BY-SA 2.0) via Flickr

The post Ten fun facts about the theremin appeared first on OUPblog.

October 10, 2016

Homelessness: issues by the numbers and how you can help

10 October is World Homeless Day. This day is dedicated to increasing awareness of the global issues surrounding homelessness, as well as getting people involved in their community to help meet the needs of homeless people locally. The increased publicity and solidarity of the global platform helps to strengthen grassroots campaigns at the most local level. The problems regarding homelessness are multifaceted, but there has been evidence of some promising interventions, particularly in the realm of social work. This post addresses some of the statistics of the widespread problem of homelessness, presents some possible interventions, and offers ways that you can help take action immediately.

By the numbers:

A study conducted by the National Alliance to End Homelessness reported a point-in-time estimate of 744,313 people experiencing homelessness in January 2005.

Because homelessness counts are taken as a snapshot, they often miss people who experience relatively brief episodes of homelessness. The Philadelphia and New York City homeless management information systems revealed that 4–6 times the number of people homeless on a given day passed through the shelter systems of the two cities in the course of a year.

It has been estimated that between 2.3 million and 3.5 million people experienced homelessness in one year across the United States.

Based on data from a random-digit dialing telephone sample of 1,507 adults living in 48 contiguous states, a lifetime homelessness prevalence rate of 7.4%, or 13.5 million people, has been found by researchers.

About one-quarter of single homeless adults are veterans, twice the rate of the general population.

The National Survey of Homeless Assistance Providers and Clients (NSHAPC) has found that two-thirds of their homeless clients suffered from at least one alcohol, drug, or mental health problem in the past month of their study’s research.

It is estimated that between 1.6 million and 1.7 million youth run away or experience homelessness each year. According to the Runaway and Homeless Youth Act (JJDPA, P.L. 93–415), a “homeless youth” is an individual who is not more than 21 years of age for whom it is not possible to live in a safe environment with a relative, and who has no other safe alternative living arrangement.

The ability of women with children to leave homelessness at a faster rate was found to be related to their greater access to institutional resources, rather than lower incidence of personal problems and difficulties.

In the above study, the gender gap in accessing housing subsidies among sample members was striking: 55% of women with children and 24% of single women, compared to only 13% of men, reported access to subsidized housing.

68% of the homeless population is male.

Some promising interventions

Homeless Veteran in New York by JMSuarez. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Mainstream social service system programs such as mental health, substance treatment, and child welfare are currently inadequate to help fully reintegrate homeless people back into society. Research suggests there are particular socioeconomic and mental health factors to target in prevention efforts, and there are some promising interventions that have been shown to be effective in addressing homelessness among members of special needs populations.

One promising intervention is the “housing first” model, which is a housing and service approach that places homeless tenants directly into affordable housing without requiring “housing readiness” prior to entry (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2005). Housing readiness admission criteria in permanent supportive housing typically include mandated sobriety for an extended period of time, compliance with mental health and substance abuse treatment, and demonstration of basic living skills (Caton et al., 2007). Without requiring housing readiness, the housing first approach has shown to be applicable for persons experiencing chronic homelessness, as these individuals often find it difficult to meet the admission criteria of conventional supportive housing programs (Padgett, Gulcur, & Tsemberis, 2006; Tsemberis & Eisenberg, 2000).

How you can help address societal issues of homelessness today:

1. Educate yourself about the homeless and understand the issues – Stereotypes about homeless people are rampant. It’s important to learn about the many different reasons why people end up homeless, from lost jobs to mental illnesses, to escapes from domestic abuse. Recognize homeless people as individuals in need.

2. Be kind to the homeless people you encounter – Respect them and be courteous to them.

3. Give food to the homeless people you encounter – If you pass someone asking for spare change, offer him or her some food to eat.

4. Donate money – Giving money to nonprofit organizations that serve the homeless can produce a substantial collective impact.

5. Donate clothing – Clothing, particularly during colder months, is vitally important for people living on the streets.

6. Donate groceries to soup kitchens and shelters, not just for Thanksgiving – Nonperishable items are always in need at local shelters and soup kitchens.

7. Donate toys – Though many people give to Toys-for-Tots every year, it’s important to remember to donate all year round.

8. Volunteer at soup kitchens and shelters – Help provide the basic necessities to individuals in need, and learn through first-hand experience about the issues of homelessness.

9. Volunteer for follow-up programs – Follow-up programs help homeless people transition from homelessness to permanent housing by providing them with a variety of interventions to help them achieve stability and retain their housing. Programs offer advice, counseling, education, life skills development, and community resource information.

10. Volunteer at a battered women’s shelter – Many of the women who end up in these shelters were involved in abusive relationships. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2010 found that 35.6% of women in their study had experienced rape, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime (Black et al., 2011). Additionally, they found that an estimated 42 million women experienced at least one of these forms of violence in the past 12 months. Women’s shelters provide a place for women when they have no other place to turn, oftentimes because they are afraid of being found by their abusers.

11. Spread the word about local shelter information – Publishing information about local shelters along with their lists of particular needs would help make it easier to get your community involved. Information on websites, newspapers, or church/synagogue bulletins can help to generate awareness and increase involvement.

Featured image credit: Homeless by Marc Brüneke. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Homelessness: issues by the numbers and how you can help appeared first on OUPblog.

Alternate realities: Brexit and Pokémon

As with many households across the globe – regardless of the age (or existence!) of children – my children became obsessed by the “Pokémon-Go” euphoria that captured mobile apps and social media in July and August this year. To be truthful, I didn’t want to show my naivety as to what I plainly did not understand so I played along as my children ran around searching for these curious-looking Pokémons (or is it Pokémoni?). It was a frenetic period that I did not quite grasp and decided that it was a fad that would soon die down and fade away. On reflection, I was perhaps too traditional in my view that a game so premised upon such an ephemeral proposition would not last. Despite cerebrally knowing what technology could now do, I was perhaps loathed to accept what is simply a further step in how the virtual and my physical existence now interact.

At the same time, many of us were coming to terms with the EU referendum result, seeking to compute the enormity of what had happened on the 23 June, and to reconcile ourselves to the consequences. For many, membership of the EU is as instinctive and fundamental to the UK’s global identity as its membership of NATO, or of the UN. So, just as my head and heart were in tension in understanding Pokémon-Go, I now wonder whether the same was true as regards the European referendum? My head knew that the referendum would be tight, that the campaign had been badly fought and that many in the UK still saw the EU as the institutional zenith of the “other” telling us what to do. “Take back control” was a myth but it was also a very powerful – a very emotive – catchphrase, which (whether we like it or not) resonated with a sizeable proportion of the electorate. Notwithstanding this, my heart hoped for the best… we surely wouldn’t throw it all away? Surely not.

And this tension between head and heart seems to have also clouded how many of us, as environmental lawyers, have prioritised the environment in discussions on Brexit. To do so ignores, however, an invariable fact; namely that the environment has barely mattered. Or, more accurately, that for most who voted Leave (and indeed for many who voted Remain) the environment is a long way down the Brexit agenda. It had scant impact on the campaign, and its relevance in the aftermath remains equally unclear. For sure, some tried to raise the issue of what the EU had done for the environment, but there was an almost inverse relationship between the sincerity and earnestness of the arguments presented, and the likely effect this had on the wider population. There was also the prospective debate as to whether the EU would be able to continue to play a leading role in such critical matters as climate change – and to meet its commitments – without the continuing membership of the UK. Again, valid questions but hardly persuasive in the popular consciousness.

So, just as my head and heart were in tension in understanding Pokémon-Go, I now wonder whether the same was true as regards the European referendum?

Within any discourse on Brexit, there is, of course, a particular paradox; the ecological and economic interdependence facing any State, be it part of a regional grouping or otherwise. Indeed, since the referendum result, the first official steps towards recognising the Anthropocene as the next geological epoch have been taken. And within the UK, the nature and extent of such global interdependence has also become apparent, perhaps most acutely in terms of the UK’s future energy policy. The decision in September to continue with the Hinkley Point C nuclear reactor in conjunction with EDF, a French contractor, and the Chinese government reflects not only the inability of most States to fund themselves such huge energy projects, but also that such endeavours now reflect a synergy – however much in tension – between disparate priorities of energy security, domestic supply, the provision of sustainable energy, and other commercial realities, both for the consumer and the investor. And while the ongoing case brought by Austria and others before the CJEU against the UK for unlawful state aid is very much predicated on EU law, one should not ignore the parallel intergovernmental discussions before the Implementation Committee of the Espoo Convention on Environmental Impact Assessment in a Transboundary Context on the inadequacy of British consultation over environmental concerns. As a convention under the auspices of the UN Economic Commission for Europe, membership will persist post-Brexit, as will many other international treaties. The UK has yet to ratify the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, and has regrettably not been in the vanguard of early ratifications. Nevertheless, there is every expectation that the UK will ratify by the end of this calendar year. As a matter of international law, the UK remains within a network of legal rules and processes – in the environmental field as in many others – that reveals the false premise in any absolutism in “tak[ing] back control”.

So as the UK moves towards trying to discern which model of Brexit is to be preferred, I would argue against fatalism; that as academics and as participants in the political process, we do not simply hark back to what is going to recede gradually from us, namely our membership of the EU and our contribution to EU environmental policy. But that we re-engage (perhaps for the first time) with other regional and international processes and institutions that reflect such ecological interdependence. I may not have understood the allure of capturing Pokémon – I now think the singular is also the plural – but I hope I am not so trenchant as to run around in the hope of spotting something even rarer; UK membership of the EU as it existed prior to 23 June 2016. That truly is becoming an alternate reality.

Featured image credit: Pokémon planet. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Alternate realities: Brexit and Pokémon appeared first on OUPblog.

October 9, 2016

Is elementary school mathematics “real” mathematics?

When people think of elementary school mathematics, they usually bring to mind number facts, calculations, and algorithms. This isn’t surprising, as these topics tend to dominate classroom work in many elementary schools internationally.

There is little doubt that elementary students should know the multiplication tables, be able to do simple calculations mentally, develop fluency in using algorithms to carry out more complex calculations, and so on. Indeed, these topics are fundamental to students’ future learning of mathematics and important for everyday life. Yet, is elementary students’ engagement with these topics in itself engagement with “real” mathematics?

I suggest that classroom discourse in an elementary school classroom where students engage with “real” mathematics should satisfy two major considerations. First, it should be meaningful and important to the students. Elementary students’ engagement with the topics I mentioned earlier can offer a productive context in which to satisfy this first consideration, especially if students’ work is characterized by an emphasis not only on procedural fluency but also on conceptual understanding.

Second, the classroom discourse in an elementary school classroom where students engage with “real” mathematics should be a rudimentary but genuine reflection of the broader mathematical practice. One might interpret the second consideration as asking us to treat elementary students as little mathematicians. That would be a misinterpretation. The point is that some aspects of mathematicians’ work that are fundamental to what it means to do mathematics in the discipline should also be represented, in pedagogically and developmentally appropriate forms, in elementary students’ engagement with the subject matter.

In its typical form, classroom discourse in elementary school classrooms fails to satisfy the second consideration. A main reason for this is the limited attention it pays to issues concerning the epistemic basis of mathematics, including what counts as evidence in mathematics and how new mathematical knowledge is being validated and accepted. The notion of proof lies at the heart of these epistemic issues and is a defining feature of authentic mathematical work. Yet the notion of proof has a marginal place (if any at all) in many elementary school classrooms internationally, thus jeopardizing students’ opportunities to engage with “real” mathematics.

Consider, for example, a class of eight–nine-year-olds who have been writing number sentences for the number ten and have begun to develop the intuitive understanding that there are infinitely many number sentences for ten when subtracting two whole numbers (e.g., 15-5=10). In most elementary school classrooms the activity would finish here, possibly with the teacher ratifying students’ intuitive understanding thus giving it the status of public knowledge in the classroom. However, in a classroom that aspires to engage students with “real” mathematics, new mathematical knowledge isn’t established by appeal to the authority of the teacher, but rather on the basis of the logical structure of mathematics. Thus the teacher of this classroom may help the students think how they can prove their intuitive understanding.

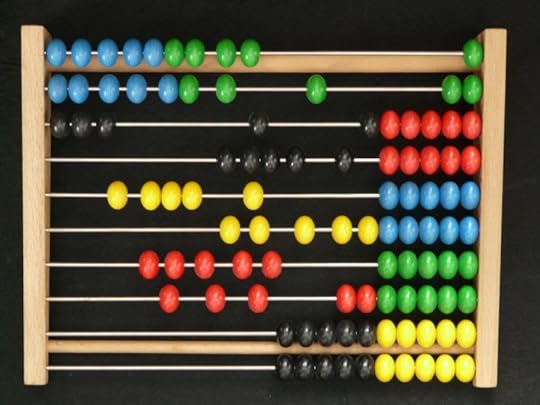

Abacus by Hans. CC0 Public domain via Pixabay.

Abacus by Hans. CC0 Public domain via Pixabay.Given appropriate instructional support, students of this age can prove that there are infinitely many number sentences for ten when subtracting two whole numbers. For example, a student called Andy in a class of eight–nine-year-olds I studied for my research generated an argument along the following lines:

To generate infinitely many subtraction number sentences for ten, you can start with 11-1=10. For each new number sentence you can add one to both terms of the previous subtraction sentence. This looks like this: 12-2=10, 13-3=10, 14-4=10, 15-5=10, and so on. This can go on forever and will maintain a constant difference of ten.

Andy’s argument used mathematically accepted ways of reasoning, which were also accessible to his peers, to establish convincingly the truth of an intuitive understanding. This argument illustrates what a proof can look like in the context of elementary school mathematics. The process of developing this argument contributed also a powerful element of mathematical sense making to Andy’s work with number sentences for ten: As he carried out calculations to write the various number sentences, he thought deeply about key arithmetical properties (e.g., how to maintain a constant difference) and he put everything together in a coherent line of reasoning. Thus an elevated status of proof in elementary students’ work can play a pivotal role in students’ meaningful engagement with mathematics. This presents a connection with the first consideration I discussed earlier.

To conclude, elementary school mathematics as reflected in typical classroom work internationally falls short of being “real.” Yet it has the potential to become “real” if the learning experiences currently offered to elementary students are transformed. A major part of this transformation needs to concern the epistemic basis of mathematics, with more opportunities offered for students to engage with proof in the context of mathematics as a sense-making activity. The teacher has an important role to play as the representative of the discipline of mathematics in the classroom and as the person with the responsibility to induct students into mathematically acceptable ways of reasoning and standards of evidence. This is a complex role that cannot be fully understood without a strong research basis about the kind of teaching practices and curricular materials that can facilitate elementary students’ access to “real” mathematics.

Featured image credit: Math by Pixapopz. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Is elementary school mathematics “real” mathematics? appeared first on OUPblog.

How well do you know your world leaders? [quiz]

In today’s globalised and instantly shareable social-media world, heads of state have to watch what they say, just as much – and perhaps even more so – than what they actually do. The rise of ‘Twiplomacy’ (Twitter now being the social media channel of choice for world leaders to reach large audiences) and the recent war of sound bites between Donald Trump and Hilary Clinton speak to this ever increasing trend. Despite the seeming ubiquity of the one-liner, this is in fact nothing new. World leaders have always harnessed the power of short slogans and memorable statements to capture the popular imagination.

Winston Churchill was famously described as having ‘mobilized the English language and sent it into battle’, whilst Boris Yeltsin memorably quipped ‘You can build a throne with bayonets, but you can’t sit on it for long.’ Foreshadowing the refrains of today’s presidential debates, President Kennedy once jibed ‘Do you realise the responsibility I carry? I’m the only person standing between Nixon and the White House.’ With these witty refrains in mind, test your knowledge of world leaders and their retorts – do you know who said what?

Featured image credit: Earth Globe Antique by PIRO4D. Public Domain via Pixabay.

Quiz image credits, in order of appearance: Earth by PIRO4D. Public domain via Pixabay; Jelly Beans candy by skeeze. Public domain via Pixabay; Phone dial old by 526663. Public domain via Pixabay; Books pages story by Unsplash. Public domain via Pixabay; Spectacles glasses vision by MabelAmber. Public domain via Pixabay; Army boots worn by B_Me. Public domain via Pixabay; Ball glass reflection by FeeLoona. Public domain via Pixabay; Tin Soldiers by Donations_are_appreciated. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post How well do you know your world leaders? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

Twitter and the Enlightenment in early America

A New Yorker once declared that “Twitter” had “struck Terror into a whole Hierarchy.” He had no computer, no cellphone, and no online social media following. He was not a presidential candidate, but he would go on to sign the Constitution of the United States. So who was he? And what did he mean by “Twitter”?

William Livingston was an eighteenth-century lawyer, a colonial intellectual, and a co-founder of the first magazine published in New York. Born in Albany in 1723, he had graduated from Yale University at the age of eighteen and embarked on a legal career in New York City. Simultaneously, he had put himself at the forefront of the provincial literary community by publishing poetry in the 1740s, joining a Manhattan society of learned gentlemen, and planning a colonial magazine modeled on celebrated early-eighteenth-century metropolitan journals such as The Tatler, The Spectator, and The Independent Whig. The first issue of Livingston’s periodical, which took the name of The Independent Reflector, appeared in New York in late 1752. A further 51 issues were printed before the magazine ceased in November 1753. From its outset, The Independent Reflector pledged to expose and denounce all “public Abuses” in New York. Livingston made true on that promise by using his magazine to launch fierce and controversial attacks on the local Anglican establishment.

Inclusion of the phrase “a single Twitter” in the September 1753 issue of The Independent Reflector very likely marked the first usage of the word “twitter” in American political writing. The phrase occurred in an anticlerical piece that defended ridicule as a weapon against the vice and corruption of oppressive rulers and priests. With reference to a London predecessor to The Independent Reflector, Livingston bragged that:

“The Independent Whig has gone farther towards shaming Tyranny and Priestcraft (two dismal Fantoms not over-apt to blush) with downright Banter, than could have been effected by austere Dogmas, or formal Deductions. He has often displayed their Deformity with a Sarcasm, and struck Terror into a whole Hierarchy, by raising a single Twitter.”

Truth, Livingston explained, was immune to ridicule. But falsehoods were not. A simple joke could therefore expose and undermine the lies and ignorance propagated by iron-fisted authorities. Yet, it posed no threat to veracity. William Livingston. Public Domain from The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library.

William Livingston. Public Domain from The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library.

What did “twitter” mean in this context? According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word “twitter” entered the English language as a verb around 1374 when Geoffrey Chancer wrote that a “Iangelynge” or chattering bird “twiterith.” The twenty-first-century social media company that takes Twitter as its name recalls this original definition with its logo of a blue bird in flight and in song. However, “twitter” assumed several other meanings after the fourteenth century and Livingston had one of these in mind when he deployed the word as a noun in 1753. Twitter, as the colonial New Yorker used it, meant a stifled laugh or a giggle.

The word “twitter” entered the lexicon of American politics during the Enlightenment. Eighteenth-century writers commonly considered their times to be a uniquely “enlightened age.” They broadly agreed that ignorance, dogma, irrationality, and tyranny had become vulnerable after centuries of dominance, and that humankind now had the potential to achieve great intellectual and societal improvement. Some protagonists of the Enlightenment equated the eighteenth century with an age of reason, but others did not. Livingston stood in the latter camp. His 1753 essay on ridicule aligned enlightenment with polite wit rather than scientific logic. It stated that dull rational discourse inevitably falls flat. By contrast, mockery and satire provide effective weaponry against tyranny and public untruths. Livingston observed that, “Mankind are willing to be facetiously taught” and “they care not to be dogmatically tutor’d.” In other words, sharp-tongued quips often have more popular influence than dry arguments.

More than 260 years have passed since Livingston identified twitter as a tool of enlightenment. The word now refers overwhelmingly to a platform for online social networking. Presidential candidates vie for office by rapid-firing tweets to their several million online followers. Digital technology impacts our politics and reshapes our public discourse. Even so, Livingston’s essay remains relevant. It reminds us that short, sharp messages often speak loudest and that sometimes the most effective political act is not to reason against but to make fun of the lies of public officials.

Featured image credit: “Washington at Constitutional Convention” by Junius Brutus Stearns, 1856. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (Livingston is depicted standing to the left of the door and behind George Washington.)

The post Twitter and the Enlightenment in early America appeared first on OUPblog.

How to write a grant proposal

Whatever its scale or ambition, a grant proposal aims to do two things: to show that a particular project needs to be supported by a funder and to show why some individual, group, or organization is the right one—the best one—to carry out the project.

Showing the “need” is largely an exercise in argumentative writing. It’s argumentative not in the hostile, red-faced, fist-shaking sense but in the classical sense of establishing a claim, developing and supporting it, and taking into account the concerns of a reasonable but skeptical audience.

In a grant, your claim is that some project is necessary, and you can support this claim by identifying the gap in services or gap in knowledge that the work addresses. The flip side of need is impact, so you’ll usually want to go beyond necessity to showing how things will be different once the work is completed. If your project is supporting dental education for rural populations, you’ll want statistics and quotes that explain why it needs to be done. And you’ll want to explain how this will change the community in the long run, not just in the period of the grant.

If you are writing a grammar of an endangered language, you’ll want to show that the need is urgent because the speakers are dying off. And you’ll want to show that the grammar will have a broader impact, contributing to cultural or scientific projects. If you are writing a biography of a historical figure, the need may arise from new material (letters, manuscripts, unsealed papers) or new ways of interpreting historical documents and events. And you’ll want to let the funder know what significant things the biography will tell us about an era, movement, or culture.

The argument for the need should also be framed with reference to the funder’s values and priorities and how the project relates to them. Often a funder’s values and priorities will be explicit in the grant application questions. Is their focus geographical? Demographic? Disciplinary? Are matching funds a must? A close reading of funder’s mission—and a look at previous projects they have funded—will save you (and them) a lot of time if you are not really a good fit.

“Blogging?” by Anonymous Account. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

“Blogging?” by Anonymous Account. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.The other job of a grant proposal is to show why you are right for the project. This is an exercise in persuasion. The task is to convince the funder that you (or your group or organization) are prepared to organize, track, and complete the project. Highlight your track record with similar proposals and other work that qualifies you for this project. Show that you have thought through the methodology, timeline, budget, audience, and future of the work. Indicate the contingencies in place for getting around potential roadblocks. Document a broad base of support describing the roles and commitment or key collaborators, advisory groups, and partner organizations.

That’s all there is to it. Argue for the need for the project. Persuade the funder that you are the best one to do it.

All grant applications are not identical, of course. Most ask specific questions about audience, access, partnerships, sustainability, evaluation, or more. Some applications will give you 25 pages to make your case; others will give you a box allowing no more than 300 words per answer. But if you have a clear vision of the need for the project and your relationship to it, the writing will go more smoothly whatever the format.

Think of grant writing as business writing that shows some passion: direct and straightforward, a minimum of rhetorical flourishes, abbreviations, undefined technical terms, and no loaded language or slang. Follow the journalistic inverted pyramid style of putting the most important information first and aim for a positive tone that presents a vision not a problem.

Finally, keep in mind that grant applications are read by people. Each reader will have a different specialty and a different set of concerns. Some will question your evidence, some will question your methodology or your evaluation plan, some will comb over your budget or résumé, and some will circle your typos in red. So as you proof your application before hitting the submit button, put yourself in the shoes of these different personalities and try to anticipate what might stand out to them.

If grants seem daunting, remember that grant writing is also a transferable skill—the same rules can be applied to: business plans; book, film, and project proposals; and white papers to address community or national issues. Essentially, it’s just writing that gets things done.

Featured image: “Seems Legit – panel 3 of 6” by Andrew Toskin. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post How to write a grant proposal appeared first on OUPblog.

Darwinism as religion: what literature tells us about evolution

Critics of the New Atheists argue that they are as religious as those whom they excoriate. Their writings show a polemical scorn for their opponents unknown outside those books of the Old Testament devoted to the prophets. It is not purely contingent that the world’s most famous non-believer, Richard Dawkins, author of the God Delusion, is also the world’s most famous evolutionist, Richard Dawkins, author of the Selfish Gene. The New Atheist creed is Darwinism, a secular world picture that dates to 1859, the year of publication of Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species.

The New Atheists deny this charge vehemently, so naturally as a philosopher interested in the relationship between science and religion I am attracted to the issue, and as an evolutionist I am convinced that understanding of the present demands understanding of the past. Hence, Darwinism as Religion: What Literature Tells Us About Evolution. I argue that, from the publication of the Origin, enthusiasts have been building a kind of secular religion based on its ideas, particularly on the dark world without ultimate meaning implied by the central mechanism of natural selection. Thus, I conclude that not only are the New Atheists in the secular-religion business, it would be very peculiar and historically anomalous if they were not.

Although I have been writing now for over forty years on Darwin and the revolution that he brought about, in Darwinism as Religion I use a strategy entirely new to me–and although obviously one familiar to scholars in English Literature basically ignored by full-time historians of science. I turn to British and American literature for insights, working from the great novelists and poets of the nineteenth century–George Eliot, Thomas Hardy, Emily Dickinson, and others–down to the writers of today–ending with the very different perspectives of the British novelist Ian McEwan and the American novelist Marilynne Robinson. By running through the concerns of conventional religions–God, origins, humans, race and class, morality, sex, sin and redemption, the future–I show how people thought (and continue to think) in ways that are as based on Darwin’s insights as they are on rejection of long-established doctrines, Christian doctrines in particular.

Take as an example that of proper behavior, ethics. Even before the Origin people worried about whether one could have morality without the Christian God. In Nemesis of Faith (1849), James Anthony Froude (brother of one of the closest associates of John Henry Newman) has his main character (an Anglican clergyman) lose his beliefs in Christianity and then follow a very morally dicey career entangled with another man’s wife. Even after the Origin, Darwin’s “bulldog” Thomas Henry Huxley–the father of agnosticism–argued for compulsory school bible study for its moral value. Yet the novelists, above all George Eliot, took up the challenge. Especially in her last full-length novel, Daniel Deronda (1876), through the behaviors of her two main characters–the beautiful but selfish Gwendolen Harleth and the conversely truly altruistic Daniel–Eliot shows how good behavior of a kind stressed by Darwin in his Descent of Man (1871) leads to happiness and how bad behavior leads only to misery. Morality is its own justification, a theme picked up by Mrs. Humphrey Ward (the former Julia Arnold, niece of the poet) in her smash-hit best-seller Robert Elsmere (1888). Her hero, another Anglican clergyman, likewise loses his faith (thanks in major part to Darwin) but not only remains loyal to his wife but takes up the satisfying role of a teacher in a kind of proto-YMCA night school for the working classes.

Just as we have the proselytizing Darwinian New Atheists, so we have today a vocal anti-Darwinian party, consisting somewhat surprising not only of the evangelical Christians of the American South but of some of today’s most eminent atheist philosophers, notably Thomas Nagel, OUP author of Mind and Cosmos: Why the Materialist Neo-Darwinian Conception of Nature is Almost Certainly False (2012). As his subtitle reveals, Nagel’s worry is less about the science and more about its supposed religious-cum-metaphysical implications, namely that Darwin plunges us into a hateful world without value and meaning. This kind of worry is shared by many students of the history of evolutionary theory, and–although unlike atheists who deny the existence of Jesus Christ one can hardly deny the existence of Charles Darwin–there is today a veritable cottage industry of writers proving that Darwin was unimportant and that there was no revolution bringing on evolution, certainly no Darwinian Revolution. As Darwin as Religion takes on the New Atheists Darwin idolizers, so also it takes on the Darwin deniers, arguing that there was a revolution, that Darwin was the key figure, and that, as is shown by the discussion of morality in the last paragraph, fears about godless materialism, stripped of meaning and value, are simply without historical foundation.

Featured image: 6 editions of ‘The Origin of Species’ by C. Darwin. CC-BY-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Darwinism as religion: what literature tells us about evolution appeared first on OUPblog.

October 8, 2016

Space travel to improve health on earth

World Space Week has been celebrated for the last 17 years, with events taking place all over the world, making it one of the biggest public events in the world. Highlighting the research conducted and achievements reached, milestones are celebrated in this week. The focus isn’t solely on finding the ‘Final Frontier’ but also on how the research conducted can be used to help humans living on Earth. In honour of this, Lisa Brown explains some advancements in medicine that impact life in space and could influence medical development on Earth.

As our ambition to reach further into outer space increases, it is not only engineering that we need to consider. Long distance space travel poses many human physiological challenges that need to be overcome. No air pressure, below freezing temperature, burning cosmic radiation, and lack of gravity – space is an inviting environment!

Space research benefiting medicine on Earth

The International Space Station (ISS) is pressurized, heated, and contains adequate oxygen which mitigates many factors encountered, however, the lack of gravity is still an enigma. The knowledge that has been gained in sustaining healthy human life in space has provided invaluable advances to the understanding of complex medical conditions experienced by patients on Earth.

One such example is in cardiovascular research. The lack of gravity encountered by astronauts on long duration space missions alters the normal distribution of fluid in the body. There is a shift of fluid from the lower body to the upper body. This shift, in conjunction with other changes seen in the blood vessels, leads to altered fluid flow through the heart and subsequently loss of cardiac muscle strength. Research on both the ISS and bed rest studies have enabled the understanding of this complex process. This has also helped to progress treatment of analogous conditions seen in patients on Earth such as cardiomyopathy.

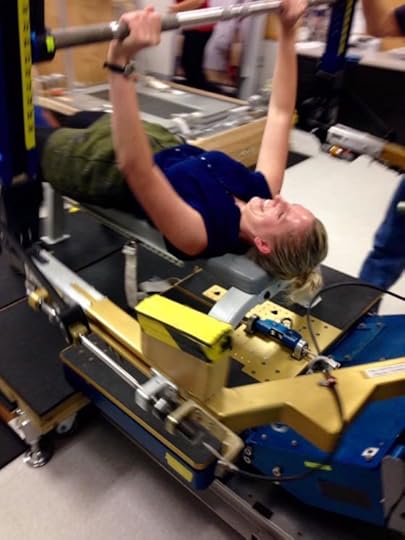

The ARED by Lisa Brown. Image used with permission.

The ARED by Lisa Brown. Image used with permission.Another significant advance has been in the management of bone and skeletal muscle loss that occurs in microgravity, particularly with the use of exercise machines which have been developed to provide resistance. The ARED (Advanced Resistive Exercise Device) has revolutionized this. It utilizes vacuum canisters to provide resistance as a substitute for weight, and can be varied to suit all body shapes and sizes. During missions on the ISS, astronauts exercise for almost two hours a day to reduce their muscle loss.

Human preparation for space travel

In preparation for travel to space, astronauts undergo an extensive training process to help withstand the adverse environment. This can take a minimum of two years. To understand the effects of living in a remote environment, far away from home, many astronauts live for periods of time in similar remote environments available on Earth, such as Antarctica or NEEMO (an underwater station). To begin to condition themselves to the havoc that plays on the vestibular system in space with a lack of gravity, they undergo trips in planes which are capable of parabolic flight – experiencing close to half a minute of weightlessness. During weightlessness, your body is unable to tell which way is up and the normal signals of head position are lost, which can result in severe nausea and disorientation.

Two of the most intense parts, as described, in many trips to space, are that of launch and re-entry. Significant G-forces are absorbed during these phases. Many astronauts are trained pilots who may have experienced this regularly in their careers, but many may have not, and are subsequently instructed on how to reduce the loss of consciousness or G-LOC encountered. This occurs when the G-force distributes blood in the body away from the brain, causing the brain to become hypoxic and lose consciousness. Centrifuges are used to train astronauts to try different straining manoeuvres to prevent the G-LOC occurring.

Ongoing issues for future space travel

There are still several aspects of the space environment which are not concordant with healthy human life and this is part of current research, to ensure that not only could we survive a long duration space journey, but if we were to travel to Mars, we could arrive in a functioning condition. One of the current challenges is that of VIIP (Visual impairment intracranial pressure). This involves trying to understand the mechanism behind visual changes/loss experienced by astronauts after long duration missions, and the relation of this to upper body fluid shifts causing raised intracranial pressure.

Surgery in space is also an idea which may seem more science fiction than science fact, though being able to adequately treat a person who may incidentally develop appendicitis or cholecystitis in space is important. Solving this potential problem is advancing the technology of minimally invasive devices and brings to the forefront new ideas around 3D printing of surgical devices or prostheses on an as-required basis, preserving the precious weight and volume load of a space vehicle.

Exploring the ‘Final Frontier’ pushes the boundaries of human technology and every advance helps not only the astronauts or Space Flight Participants involved, but contributes to the progression of knowledge on Earth.

Featured image: Shuttle Atlantis by Lisa Brown. Image used with permission.

The post Space travel to improve health on earth appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers