Oxford University Press's Blog, page 456

October 8, 2016

How would the ancient Stoics have dealt with hate speech?

Insults have lately been making headline news. Last year, the world witnessed an attack on the offices of the French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo. Eleven people were killed, and another eleven were injured. The attackers felt that some of the cartoons the newspaper had published had insulted the prophet Mohammed, and they were willing to sacrifice their own lives to right that wrong.

In America, political pundits were astonished by the rise of Donald Trump. The rise was fueled in large part by his willingness to insult other Republican candidates, along with a wide array of ordinary citizens. Trump insulted women. He insulted war heroes. He insulted journalists. And this was just the beginning. The New York Times recently published a list of 258 people, places, and things he had insulted—on Twitter alone. There were also many verbal insults.

On America’s college campuses, insults made headlines of a different sort. Students complained that they were being bombarded by insults. As a result, they felt humiliated and even downtrodden.

I was initially puzzled by these last reports. Had college campuses—including places like Yale University—been invaded by louts, bullies, and bigots? Further investigation revealed that what instead had happened is that students—in many cases, with the encouragement of the university faculty and administration—had defined down what counted as an insult. They had, as a result, become hypersensitive to insults, meaning that just about anything could count as one. On one campus, for example, students were cautioned against referring to a mixed group of male and female students as “you guys.” The females in the group might feel left out, and as a result, their feelings might be hurt.

This last “insult” is an example of what have become known as microaggressions. They are such will-o’-the-wisp things that it takes training to spot them, and at many universities, there are people who are quite happy to provide that training. Once you start looking for microaggressions, though, you will find them everywhere, and as a result, you will end up feeling very insulted, which is what had happened on American college campuses.

At the same time as students were learning to spot microaggressions, they were being told that as individuals, there was very little they could do to defend themselves. What they had to do, when insulted, is to turn to the university administration for protection—or maybe even the campus police.

Seneca, part of double-herm in Antikensammlung Berlin. Photo by I, Calidius. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Seneca, part of double-herm in Antikensammlung Berlin. Photo by I, Calidius. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.If we could travel back in time and transport an ancient Stoic philosopher—someone like Epictetus or Seneca—back to the future, he would likely be astonished by efforts to sensitize students to insults. What these students need, he would assert, is to be desensitized! More precisely, they need to learn how to shrug off insults. Furthermore, telling students that they are helpless to deal with insults on their own only makes matters worse. Start thinking of yourself as a helpless victim, and you are likely to have a miserable existence.

The Stoics, after devoting considerable thought to how best to respond to insults, concluded that we would do well to become insult pacifists. When insulted, we should not insult back in return; we should instead carry on as if nothing had happened. It is, I have found, a very effective way to deal with many insults. On failing to provoke a rise in his target, an insulter is likely to feel foolish.

And if we feel that we simply must say something in response to an insult, the Stoics recommend that we engage in self-deprecating humor—that we insult ourselves even worse than the insulter did. I have experimented with this technique. A few years back, a colleague told me that as part of his research for a book he was writing, he was reading some articles I had written. I felt flattered. Then he lowered the boom: he explained that he was trying to decide whether he should characterize me as being evil or merely misguided.

There were many things I could have said at that moment, but I suspect that none of them would have been as effective as what I did say: “Why can’t you characterize me as being both evil and misguided?” It turned out to be a singularly effective reply. If I remember correctly, his only response was to complain that I need to take things more seriously—meaning, I guess, that when insulted, I need to let my feelings be hurt. By turning an insult into a joke, we prevent the insult from taking root in our psyche, where it will cause us to experience needless anguish.

What about hate speech, though? Should we remain silent in the face of a racist insult? It depends on the situation. But the one thing we should not do is take the insult personally. We should instead dismiss hate speech, in much the same way as we should dismiss the barking of an angry dog. We should keep in mind that the dog, not being fully rational, cannot help itself. The Stoics would add that if we let ourselves get angered or upset by a barking dog, we have only ourselves to blame.

The Stoics lived long ago and in a very different world than the one we inhabit. But because human nature has changed little in the last two millennia, their advice regarding insults remains as useful as ever. Has someone insulted you? If you can bring yourself to shrug it off, you will simultaneously reduce the harm it does you and deprive the insulter of the pleasure he might have taken in hurting your feelings. It is a win-win strategy.

Featured image: La muerte de Séneca by Manuel Domínguez Sánchez. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How would the ancient Stoics have dealt with hate speech? appeared first on OUPblog.

October 7, 2016

The transformation of food in America in the 19th century

At the start of the 1800s, American cities had only a few public dining options such as taverns or hotels; by the end of the century, restaurants had become “a central part of the fabric of cities.” In the 19th century, the landscape of food consumption in America greatly changed. The modern concepts of retail food shops, restaurants, industrial food systems, and diverse food options emerged. As commute times increased, urban workers no longer went home for lunch, and instead grabbed hot meals being served by their offices and factories.

Travelers and tourists started to want meals from places other than their hotels, and newly-arrived immigrants sought social places that connected them to their homeland through food. Bringing their cultures with them, the increasing immigrant populations in urban areas greatly influenced American cuisine, which was experiencing a time of great transformation. The below facts illustrate how America became a melting pot for tastes and flavors by the start of the 20th century:

1. In the beginning of the 19th century, street food vendors consisted mainly of poor women selling a single item. As ethnic diversity increased throughout the decades, vendor options became much more diverse. “German vendors offered pretzels and sausages; Chinese salesmen peddled rock candy; Italian peddlers hawked fruits and vegetables.” Mexican immigrants sold tamales—San Francisco’s most famous street food by the 1880s.

2. Although New York City did not pioneer the restaurant (that distinction goes to Paris), New York did create a template for high- and low-end restaurants that other cities replicated. The most famous elite restaurant, Delmonico’s, was opened up by two Swiss-born brothers in 1827. They employed a French chef and “pioneered such dishes as Lobster Newburg and Baked Alaska.”

3. In New Orleans, in 1840, the first French restaurant, Antoine’s, was founded by the French immigrant Antoine Alciatore. Antoine is still run by descendants of Alciatore to this day and continues to serve French Creole food.

4. Chinese entrepreneurs dominated San Francisco’s restaurant business, but they did not serve Chinese food. The restaurants prepared a mostly European menu, and only a few served high-end Chinese food, which “catered exclusively to white patrons.”

5. Washington, DC was the most cosmopolitan city in terms of its food offerings. The city boasted an extremely international array featuring German, Italian, Chinese, and Tex-Mex dishes.

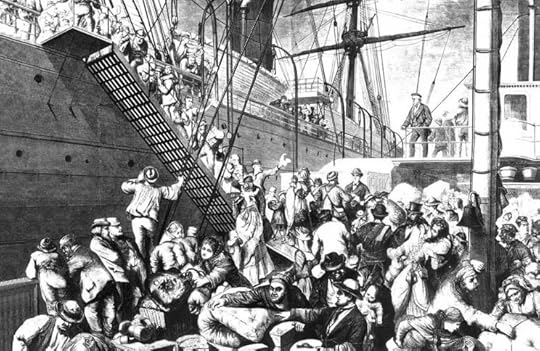

“Germans emigrate 1874” by Harper’s Weekly. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Germans emigrate 1874” by Harper’s Weekly. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.6. The sale of food items—whether it was by way of restaurant, grocery store, or street vending—provided immigrants a means to climb their way up the economic ladder. This contributed to the food landscape in America becoming more cosmopolitan in nature, as urban populations became increasingly foreign-born.

7. German, Chinese, Italian, and Mexican ethnic grocery stores “were important social institutions in immigrant neighborhoods throughout the United States.” The shops sold foods imported from the ‘old country,’ such as sharks’ fins from China and olive oil and pasta from Italy, and became informal gathering spaces for locals. Ethnic groceries also offered news from home and served as informal post offices, banks, and job offices. The stores gave ethnic groups a way to connect with one another and with their countries of origin.

8. In the 19th century, native-born Americans did not eat at ethnic restaurants. Restaurateurs were intolerant in many ways, and very few cosmopolitan diners went to Little Italy or Chinatown as they considered it a “foray into the exotic.”

9. The United States offered an abundant food landscape to late-19th-century immigrants in comparison with that available in their homelands. Foods that were previously accessible only to wealthy landowners in Italy, like pasta and olive oil, became staples of the Italian American pantry. Meanwhile, meat—a treat that Italian peasants might enjoy on an annual basis—was eaten weekly or even daily in the United States. Abundant family meals, once relegated to feast days, became weekly Sunday dinners in the homes of urban Italians and Italian Americans.

10. Sandwiches and spaghetti (Italian); egg creams (Jewish); nachos and chili (Tex-Mex); and hamburger, sausages, pickles, and the lager beer (German) were all introduced into the American diet by urban immigrants in the 19th century.

11. German immigrants are credited with inventing the American beer industry in the 1800s. They opened hundreds of breweries in cities where they settled, some of which—Pabst, Schlitz, Anheuser-Busch, and Piel’s—grew into national brands.

Featured image credit: “Mulberry Street, New York City” by Detroit Publishing Co. Public Domain via the Library of Congress.

The post The transformation of food in America in the 19th century appeared first on OUPblog.

How safe are office-based surgical facilities?

Like many plastic surgeons, and as my aesthetic practice has grown, I prefer to perform most surgeries in my accredited, office-based operating room. By operating in my office, I have access to my own highly qualified team members who are accustomed to working together. In this way, we can create an experience for the patient that is more private, safe, efficient, cost-effective, and highly likely to produce optimal results. Nevertheless, from time to time patients ask me how safe it is to have surgery outside a hospital environment.

There are pros and cons to operating in all types of accredited facilities. In the hospital, all medical and surgical subspecialties are readily available, should the need arise. However, undergoing elective aesthetic surgery in the hospital is often less-than-pleasant for the patient if they encounter hospital personnel who are not oriented towards creating a “concierge experience” for this type of healthy patient. Staff may resent spending their time taking care of someone who isn’t sick and they may even de-prioritize their care due to the nature of elective surgery. Patients often enjoy having their surgery in an office setting, but in the event of a severe complication, transfer to the hospital via ambulance may be necessary. Fortunately, with the advent of mandatory accreditation among board-certified plastic surgeons’ office-based surgical facilities, we now have improved standardization among these facilities, oftentimes meeting or exceeding those available in hospitals. The facility costs of surgery performed in an office-based setting are usually significantly lower than in hospitals, although this can vary by geography. Similarly, anesthesia costs are usually less in the office and patients are not subjected to out-of-network issues or paperwork.

Despite the long history of office-based aesthetic plastic surgery, until now we have lacked appropriate data to compare the safety of aesthetic surgery when done in the office versus ambulatory surgery centers or hospitals. Thankfully, data from CosmetAssure now gives us the answer. The American Association for Accreditation of Ambulatory Surgery Facilities (AAAASF) has previously published data that demonstrated the safety in office based facilities, which is affirmed by these new findings.

What is CosmetAssure?

CosmetAssure is an insurance program introduced in 2003 that offers financial coverage of unanticipated expenses related to major complications when they occur following elective cosmetic surgical procedures. Most everyone is aware that health insurance does not cover cosmetic surgery. However, many people are not aware that their health insurance may elect to not cover complications related to cosmetic surgery. CosmetAssure addresses that gap in insurance coverage for 45 days following an elective cosmetic operation. Plastic surgeons enroll patients into the program prior to their surgery. In this way, data from a large number of practices is collected prospectively in rapid fashion and every complication that occurs is also captured. Using these data, our research team at Vanderbilt University have been able to study the safety of cosmetic surgeries performed in office-based operating facilities compared with ambulatory surgery centers and hospitals.

Doctor by valelopardo. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

Doctor by valelopardo. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.So what did the data show? Between May 2008 and May 2013, of 183,914 total cosmetic surgery procedures performed, 70% of patients were enrolled in the CosmetAssure program. Notably, 57.4% of the procedures were performed at ambulatory surgery centers followed by 26.7% at hospitals and 15.9% in office-based surgical facilities. The utilization of hospitals decreased over the five-year period. We identified was that cosmetic surgery is very safe, no matter where it is performed, with an average complication rate of only 1.9%. Interestingly, there was a lower risk of developing a major complication in an office-based surgical facility compared with an ambulatory surgery center or hospital. This was true for complications including bleeding and infection and there was no significant difference among facilities in terms of the risk of confirmed venous thromboembolisms (VTEs).

Does this mean that office-based surgery is safe? In the hands of board-certified plastic surgeons in accredited office facilities, office-based surgical facilities are a very reasonable alternative to ambulatory surgery centers and hospitals for cosmetic procedures. Accredited offices are a safe environment for board-certified plastic surgeons to conduct single, combined, or complex cosmetic surgical procedures. Additionally, offices may have the benefit of reduced costs and better patient satisfaction without compromising safety. Safety must remain paramount in all of our minds and the facility should be chosen based upon how healthy our patients are.

Featured image credit: office by Redd Angelo. CC0 Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post How safe are office-based surgical facilities? appeared first on OUPblog.

Fiddle parts and sound posts: how objects tell stories

Biography chooses us when there is alchemy between biographer and subject—a perfect fit of interlocking puzzle pieces. In my case, a lifelong fascination with objects and the craftsmen who make them led me to the story of a pioneering violinmaker—American Luthier: Carleen Hutchins—the Art and Science of the Violin. I soon found that the stories of violinmaker and violin were intertwined—and in the process, rediscovered the poetry of the object itself.

Distinctly different from the incident, an object acts like a prism—it reflects, refracts, illuminates a story—and so offers a wide spectrum of possibilities. The object is also not straightforward and is wonderfully chaotic in the way it can be interpreted. Objects carry multiple stories in no particular order, and therein lies the opportunity.

In choosing the cover for my book, I wanted to use “Violin” by Walter Tandy Murch, a luminous painting owned by a celebrity. After a little persistence, I received quick affirmation and obtained permission from the collector due in large part to the fact that collectors love to know the stories behind their artifacts as these stories add new layers of significance and relevance to their collection. On one level, Murch depicted an actual experiment set up by my subject in her basement laboratory. But on another level, by painting an abstract, mystical image of the violin, as if the violin meant more than itself—Murch captured the lifetime obsession of my subject.

Image Credit: Studiolo from the Ducal Palace in Gubbio, Rogers Fund, 1939, Public Domain via OASC and The Met.

Image Credit: Studiolo from the Ducal Palace in Gubbio, Rogers Fund, 1939, Public Domain via OASC and The Met.Beginning a chapter often depends on finding the portal that lets the story unfold. As a Research Fellow at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, I will never forget the moment I stumbled upon the Gubbio Studiolo—the 15th century Italian Renaissance ducal palace studiolo relocated to the heart of the museum.

It took some time to figure out why this room spoke to me. Thousands of tiny pieces of different woods create the illusion of walls lined with cupboards displaying objects reflecting the wide-ranging artistic and scientific interests of Duke Federico da Montrefeltro where musical instruments sit beside scientific instruments—a compass, pendulum, an hourglass. In this room, music was perceived as a science, alongside mathematics, geometry and astronomy—in the same time and place in which Andrea Amati “invented” the violin. As a physical object, the Gubbio merges art, science and music. Metaphorically, in representing the 15th century mindset, this room “birthed” the violin.

Listen to your reaction to an object. As a biographer, you spend a lifetime researching a topic, a person, a world, an era. You are best able to spot an object that will best tell your story. In most cases, the object is already in front of you. You have handled it many times, studied it, stumbled over it, mused about it, but never before embraced it as a tool to tell your story.

Image Credit: Contrepoint pour violoncelles by Armand Fernandez (1928-2005), known commonly as Arman, photo taken by Quincy Whitney

Image Credit: Contrepoint pour violoncelles by Armand Fernandez (1928-2005), known commonly as Arman, photo taken by Quincy WhitneyThe “Messiah” violin sits sequestered in its glass-enclosed throne at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. I had studied it, researched the violin world and the violin market, and written hundreds of drafts about violin history. But it was not until I asked myself how to begin my story that I re-stumbled upon the “Messiah” and suddenly realized that the “Messiah” was my story. The most pristine, most valued and most famous of Stradivarius violins, has, in fact, never been heard—and as such, perfectly summed up the myriad of contradictions that make up the violin world.

Because the object can be interpreted on many levels, it is poetic in its economy—the object speaks volumes, literally. Like the “Messiah,” an object can present irony, add humor, stretch the imagination and embrace contradiction, depicting a life, a world, in all its complexity—the grey areas, not just the black and white.

The violin itself—with its 80 different parts—led me to a new view of my subject’s life. In studying violin anatomy, I embraced the mysterious “magic” of the sound post—a tiny piece of wood sitting inside the violin just under the bridge—the heart of the violin. The more I understood its roles and attributes—it connects top and back plates; holds position through tension not glue; can be moved to maximize sound; and is as invisible as it is essential—the more I saw that my subject had much in common with this invisible piece of wood.

In 2004, I visited Martigny, Switzerland, where I stumbled upon the outdoor sculpture Contrepoint pour violoncelles by Arman. A collage of violin parts, this tower of fiddles became the perfect metaphor for the life of a pioneering female and mother trying to follow her passion—forever taking things apart, and fitting them back together, adapting, fitting her passion around a life that would never allow her the luxury of perfect balance—a reminder of her vulnerability, her foibles, and her humanity.

Headline Image Credit: Violin plates, image supplied by Quincy Whitney, used with permission of Carleen Hutchins

The post Fiddle parts and sound posts: how objects tell stories appeared first on OUPblog.

Solution building for student success

Every year around late August and early September, students around the country prepare to begin a new school year. It’s a time of mixed emotions for many students but a fresh start to an important life experience. Teachers, administrators, and school social workers also prepare for a fresh start with new students and ideas to engage in another year of educational and developmental learning. Unfortunately, as the school year progresses, the new beginning and excitement can give way to complacency, frustration, and sometimes hopelessness. The reality for students who are disengaged from school, as well as those who experience significant academic and behavioral issues, is a season of uncertainty, diminished expectations, and possibly serious life outcomes that are just beginning.

This is especially the case for Hispanic and African American minority students who are more at risk for school failure. Schools with a higher minority student body are more likely to produce dropouts, even after controlling for various students’ attributes like socioeconomic status and academic ability (McNeal, 1997). The research also clearly shows the impact for students failing to complete high school. Research shows that high school dropouts are more likely to abuse drugs, have higher rates of mortality, increase dependence on public assistance, be unemployed, and be in jail (Aloise-Young & Chavez, 2008; Rumberger & Lim, 2008). While national dropout rates for students have decreased from 12.1% in 1990 to 6.5% in 2014, minority high school students continue to be at a higher risk of dropping out than Caucasians. In 2014, 5.2% of Caucasian students dropped out of school, compared to 7.4% for African Americans and 10.6% for Hispanics. Dropout rates were also higher for those in lower-income families. Those students who were in families in the bottom 25% in incomes had a dropout rate of 11.6% compared to 7.6% for those students in middle-low income families, 4.7% for those in middle-high income families, and 2.8% for those in the highest income families (National Center for Education Statistics, 2016).

As the data indicate, youths from diverse cultures and backgrounds are more at risk for school dropout than white students. It is an increasing challenge for school districts to engage youths who leave school prematurely or are currently failing and on the verge of leaving school. While media and academic researchers (ourselves included) bombard parents and educators with these stark statistics, it’s often the school staff and parents that are left wondering what can be done. It’s one thing to know there is a problem, but developing practical solutions is even more challenging. School social workers need interventions that can engage at-risk students and develop quick change in student behaviors and attitudes.

The research and clinical work we have done points to a different approach to helping students remain engaged in schools that shifts away from a punitive way of treating kids, which does not help them grow and learn.

The research and clinical work we have done points to a different approach to helping students remain engaged in schools that shifts away from a punitive way of treating kids, which does not help them grow and learn. Our work in solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT) is one promising intervention used by many school social workers to help students with academic and personal problems (Franklin, Streeter, Kim, & Tripodi, 2007; Kelly, Kim, & Franklin, 2007). A systematic review of SFBT studies conducted in school settings found the strength-based, future-focused approach of SFBT to be a particularly useful approach in working with at-risk students to help reduce the intensity of their negative feelings, manage their conduct problems, and reduce externalizing behavioral problems (Kim & Franklin, 2009).

Orchestrating a positive, solution-focused conversation is often referred to as solution-building and is unique to SFBT. Solution-building aims to create a context for change where hope, competence, and positive expectancies for change increase and a student can co-construct with the social worker workable solutions to their problems. Goals are also important to the change process in SFBT and are co-created by the social worker and student through an open and collaborative working relationship. Formulating answers to solution-focused questions requires students to think about their relationships and talk about their experiences in different ways, turning their problem perceptions and negative emotions into positive formulations for change. For example, students experiencing academic stress and low grades can easily become defeated by their poor performance and give up. Using SFBT allows the school social worker to identify places in the student’s school career that are working, and to break the students’ academic and behavioral goals into smaller, achievable components, thereby increasing hope for the student along the way.

One of the strengths of the SFBT approach is the that it has also proven to be very adaptable and transportable to a variety of therapeutic contexts including behavioral health and counseling clinics, school counseling and mental health services, and community social service agencies. We are hoping schools will move in a new direction that we feel is congruent with the SFBT approach to helping students, an approach that emphasizes confidence in the students and the belief they are more resourceful than we might give them credit for. Solutions abound in school classrooms and we just have to look for them. And when school staff and parents look for those characteristics, they will not see a statistic, but rather a student with unique skills and talents.

Featured image credit: “Education – Creative Commons” by NEC Corporation of America. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Solution building for student success appeared first on OUPblog.

Measuring up

My first degree was in mathematics, where I specialised in mathematical physics. That meant studying notions of mass, weight, length, time, and so on. After that, I took a master’s and a PhD in statistics. Those eventually led to me spending 11 years working at the Institute of Psychiatry in London, where the central disciplines were medicine and psychology. Like physics, both medicine and psychology are based on measurements. In medicine we might measure enzyme levels, blood pressure, heart rate, urinary flow rate, tumour size, and an unlimited number of other characteristics in patients. In psychology we might measure reaction time, pain thresholds, well being, depression, political orientation, food preferences, intelligence, and so on. What is clear about these lists is that while some of them have the same sort of physical directness as measurements in physics, others are very different. We can measure body temperature using a thermometer, but there is no physical instrument which will allow us to measure intelligence or depression. And yet we use the same word, “measurement”, in all cases. This apparent discrepancy intrigued me.

My interest was further aroused by complications arising from the interactions between statistics and the results of different kinds of measurement. Many textbooks say it’s meaningless to calculate the arithmetic mean of ordinal measurements — those where the numbers reflect only the order of the objects being measured — and yet a glance at scientific and medical practice shows that this is commonplace. Clearly, although measurement was ubiquitous throughout the entire world (or, as I have put it elsewhere, we view the world through the lens of measurement), there was more to it than met the eye. Things were not always as simple as they might seem. Indeed, it would not be stretching things to say that occasionally, consideration of measurement issues revealed apparent rips in the fabric of reality.

A simple example arises from the Daily Telegraph report of 8 February 1989, which said that “Temperatures in London were still three times the February average at 55 °F (13 °C) yesterday”, prompting the natural question: what is the average February temperature? The answer is obvious — we just divide the temperature by three. So the February average is a third of 55 °F, equal to 18⅓ °F. Alternatively, it is a third of 13 °C, equal to 4⅓ °C. But this is very odd, because these two results are different. Indeed, the first is below freezing, while the second is above. In fact, in this example a little thought shows where things have done wrong, and which average temperature is right. But things are not always so straightforward, and occasionally deep thought about the nature of measurement is needed to work out what is going on. This reveals that there are different kinds of measurement. At one extreme we have so-called representational measurement, and at the other pragmatic measurement, with most being a mixture of the two extremes.

Tape measure pay by ThomasWolter. Public domain via Pixabay.

Tape measure pay by ThomasWolter. Public domain via Pixabay.The aim of representational measurement is to construct a simplified model of some aspect of the world. In particular, we assign numbers to objects so that the relations between the numbers correspond to the relations between the objects. This rock extends the spring further than that, so we say it is heavier, and assign it a larger weight number. These two rocks together stretch the spring the same distance as a third one alone, so we give them numbers which add up to the number we give the third rock. And so on.

Representational measurement is essentially based on certain symmetries in the mapping from the world to the numbers, and understanding of these symmetries can be very revealing about properties of the world — about the way the world works. A familiar example is through the use of dimensional analysis in physics, engineering, and elsewhere. In contrast, a provocative way of describing pragmatic measurement is that “we don’t know what we are talking about.” What this really means is that we must define the characteristic we aim to measure before we can measure it. Or, more precisely, we define it at the same time as we measure it. The definition is implicit in the measurement procedure, and it is only through the measurement procedure that we know precisely what it is we are talking about. At first this strikes some people as strange. But take the economic example of inflation rate. Inflation can be defined in various different ways. None is “right.” Rather, it depends what properties you want the measurement to have, and what questions you want to answer. It depends on what you want to use the concept and the measured numbers for.

The bottom line to all this is that decisions and understanding are (or at least should be!) based on evidence. Evidence comes from data. And data come from measurements. Given how central measurement is to our understanding of the universe about us, to education, to government, to medicine, to technology, and so on, it is entirely fitting that it should be the topic of the 500th volume in the Very Short Introduction series.

Featured image credit: Scale kitchen measure by Unsplash. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Measuring up appeared first on OUPblog.

October 6, 2016

Becoming better strategic thinkers

A manager at a hotel receives an alarming number of complaints from her guests that they have to wait too long for elevators. So she requests quotes for installing an additional elevator. Turned down by the price tag of that solution, the manager seeks an alternative and decides to give her guests something to do while they wait for the elevator, by installing mirrors or televisions or providing magazines. The price tag of that solution is a lot lower and, upon implementing it, the complaints stop.

So what? Well, sometimes, the obvious solution to a problem isn’t the best, and there is value in searching for alternatives. Also, this search for alternatives might require us to think outside of our disciplines: slow elevators can be fixed with an engineering solution. It can also be fixed with behavioral solution.

People born between 1957 and 1964 averaged 12 jobs during their career, and there are no signs that this trend is going to slow down. How do we prepare—both ourselves and the next generation—for this need for constantly reinventing ourselves and adapting to ever-fast change?

Here’s an answer: develop a skill set that enables us to make sense of new and complex situations. When confronted to a complex problem, we should be comfortable identifying what the actual problem is, understanding why we are facing it, identifying potential solutions, and implementing whichever solution we think is best. We need to complement our specialist skills with generalists ones and actively work on becoming better strategic thinkers.

Complementing specialist skills to become “T-shaped”

In our personal and professional lives, we all solve problems daily. Training our students to be skilled problem solvers is also an essential part of what we do as educators. And this might start by recognizing that, beyond their apparent differences, many of the complex problems we face share some common denominators.

Some people, usually specialists in their discipline, are quick to minimize the importance of common denominators and that, therefore, we shouldn’t waste our time developing an approach that is so generic that it doesn’t really bring any value.

120726-F-QT695-010 by U.S. Air Force/Percy G. Jones. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Arctic Warrior Flickr.

120726-F-QT695-010 by U.S. Air Force/Percy G. Jones. CC BY-ND 2.0 via Arctic Warrior Flickr.Of course, there are obvious differences between, for example, medicine and the military, and those call for specialized training. But there are also similarities. Indeed, problem solving in medicine can be the same as in the military. Such an instance is Duncker’s radiation problem. Imagine having to treat a tumor in the stomach of a patient. Any ray of sufficient intensity would destroy both the tumor and the neighboring healthy tissue. An elegant solution is to simultaneously project rays of low intensity from various points around the patient that all converge at the tumor to amount to a ray of sufficient intensity. When confronted with this problem, subjects who first read a military analogy (attacking a fortress in a countryside protected by minefields that let through small groups but not an entire army) are significantly better at finding this solution, thereby supporting the idea that keeping an eye on how people solve problems in other disciplines is valuable.

Generalizing, there is widespread agreement that an ideal problem solver is “T-shaped,” that is, both a specialist in the relevant discipline(s) and a generalist.

Formal training programs usually focus on the discipline-specific side, the vertical bar of the “T,” but many fall short on the generalist front, and that’s problematical. For instance, a report by the National Academies notes that the problems that students solve in class differ considerably from the ones in the “real world” because the latter are ill-defined and knowledge-intensive. This leads to some students’ inability to translate what they learn on campus to practical situations.

Another drawback of focusing solely on the vertical bar of the T is that it limits innovation as we fall prey to the “not invented here” syndrome. Yet, there is considerable value in “stealing” ideas from other disciplines. Checklists, for instance, first appeared in airplane cockpits. Despite some initial resistance, their adoption in operating rooms has led to significant reductions in postsurgical complications. In this case and in many similar ones, an ability to see value in a field different than one’s own—the horizontal bar of the T—was needed and paid off.

One way to transform this insight into action is to think of strategic thinking as a four-step process.

First, identify the problem that you should solve (the what). Facing a new, unfamiliar situation, you should first understand what the real problem is, and what it isn’t. This is a deceptively difficult task: We often think we have a good idea of what we need to do and quickly begin to look for solutions only to realize later on that we are solving the wrong problem, perhaps a peripheral one or just a symptom of the main problem.

Second, identify why you are having this problem (the why). This starts with identifying a diagnostic key question, formulated with a why root, that encompasses all the other relevant diagnostic questions. There are various types of questions that might apply: why do I face my problem in the first place?, why do I want to solve it?, or why haven’t I solved it yet? can all be insightful. Which one you should elect depends on the specificities of your situation; the point is to elect one and use it to acquire additional insight into your problem.

Next, identify all the possible answers to that why question and then focus on the important one(s). To do that, it may be helpful to build a diagnosis issue map: a graphical representation of the problem that breaks it down into its various dimensions and lays out all the possible causes exactly once. Then, associate formal hypotheses with specific parts of the map, test these hypotheses, and capture your conclusions.

Third, identify alternative ways to solve the problem (the how). Knowing what the problem is and why you have it, you can move on to what people commonly think of as problem solving: actively searching for a solution. But instead of implementing the first solution that comes to mind, you should first consider various options, compare them, and only then decide which one(s) to implement.

You can start this by formulating a solution key question, built with a how root, and framing it. Next, identify all the possible solutions for that question and organize them in a solution issue map, develop formal hypotheses, and test them. This is a time where analogical thinking and looking at how people in other disciplines have solved similar problems can be particularly rewarding.

This will take you to the decision-making stage: selecting the best solution(s) out of all the possible ones.

Fourth, implement the solution (the do). The final step is to implement the solution(s) that you selected, which usually starts by convincing key stakeholders that your conclusions are correct before monitoring the effectiveness of your solution(s) and taking corrective steps as needed.

In summary, our strategic-thinking process comes down to four words: what, why, how, do. And yes, I concede that developing these skills requires an investment. But faced with increased complexity, the question is less and less whether we and our students can afford to think strategically but whether we can afford not to.

Featured image credit: ‘Puzzle’ by Kevin Dooley. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Becoming better strategic thinkers appeared first on OUPblog.

Rihanna and representations of black women – Episode 39 – The Oxford Comment

“Come and put your name on it,” is the first line in Rihanna’s song “Birthday Cake.” She is referring to her female anatomy as she dances in a hip-centered motion, reminiscent of Caribbean movement.

Across the globe, reactions to the song’s connotation and the provocative dancing varied greatly, each individual interpreting the sequence of events based on their own experiences, culture, race and gender. Regardless of the response to the song, the fact that Rihanna’s persona and image are an implication of something greater than herself cannot be denied.

In this episode of the Oxford Comment, Adanna Jones, contributor to the Oxford Handbooks Online, Oneka LaBennett, author of She’s Mad Real: Popular Culture and West Indian Girls in Brooklyn, and Treva Lindsey, author of the forthcoming Colored No More: New Negro Womanhood in the Nation’s Capital, discuss the transnational icon, born in Barbados with Guyanese roots instilled from her upbringing, that challenges the exploitation of the black female body, female empowerment, and what that means in a global space.

Featured Image Credit: Rihanna performing at the Kollen Music Festival 2012 by Jørund F Pedersen. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Rihanna and representations of black women – Episode 39 – The Oxford Comment appeared first on OUPblog.

Brexit and Article 50 negotiations: why the smart money might be on no deal

David Cameron famously got precious little from his pre-referendum attempts to negotiate a special position for the UK in relation to existing EU treaty obligations. This was despite almost certainly having held many more cards back then than UK negotiators will do when Article 50 is eventually invoked. In particular, he was still able to threaten that he would lead the Out campaign if he did not get what he wanted, whereas now that the vote to leave has happened that argument has been entirely neutralised.

Theresa May might nonetheless have taken some confidence from the fact that her whistle-stop tour of EU capitals on becoming Prime Minister did not reveal too much by way of open hostility. It is EU heads of state, acting through the European Council, who after all are required to formally approve the Brexit deal. They know that they will be lobbied domestically to allow the UK to keep something approximating its existing single market membership. Cameron also knew this when he was attempting his pre-referendum renegotiation, which is why he much preferred to be pictured with Donald Tusk, the President of the European Council, than with Jean-Claude Juncker, the President of the European Commission. Tusk’s position was generally to urge compromise on all sides, in the hope that Cameron could be given something that he could sell politically in the UK. Juncker, by contrast, set the tone for what he thought should happen next by reiterating that there could not be different rules for different member states.

We should therefore not expect the Commission to content itself with being merely an idle bystander in the upcoming negotiations. It has the responsibility for choosing the chief EU negotiator, and in Michel Barnier it has already installed one of its own in that role. The Council will only be given a deal to approve that the Commission has previously consented to. There must consequently be short odds on there being no deal at all, because the Article 50 protocols do not say that the two-year negotiating period must produce a result that everyone will happily sign off on. It is entirely plausible that the UK Government will not allow itself to be seen asking for something it thinks the Commission will agree to, and that the Commission will not allow itself to be seen offering something it thinks the UK Government will find acceptable.

Breaking point Euro flag by mortiz320. Public domain via Pixabay.

Breaking point Euro flag by mortiz320. Public domain via Pixabay.All the signs currently emerging from Brussels suggest that the Commission is willing to allow the formal process to descend into an unseemly scrap. This would in part be revenge for Cameron’s perceived recklessness in gambling the integrity of the entire integration process, on what ultimately turned out to be a failed attempt at internal party management. More importantly, though, if the impression takes hold that the UK is being punished for saying that it wants to leave, then this might act as a strong deterrent to stop other countries from offering their populations a chance to vote on overturning their own EU membership. If the Commission really wants to show itself to be inflicting pain on the UK then it knows that, for as long as the clock is ticking on the Article 50 negotiations with no deal yet in sight, it is the UK economy that will suffer most. Investment plans will be pushed further into the future, firms will begin to wonder openly whether moving away is now the right thing to do, and banks will struggle to maintain their business that requires full EU ‘passport’ rights.

In the ‘no deal’ scenario, the Brexiteers who now sit in the May Cabinet would probably go back to their referendum campaign mantra that this makes the UK free once again to trade with the rest of the world. What this means in practice is that the UK would have to rely on making trade deals with other countries on the basis of World Trade Organization rules. This would involve recreating from scratch the deals that it is already a signatory to as a partner in the EU’s collectively negotiated deals. Experience suggests, though, that countries outside the so-called Quad – that is, the WTO’s four-pronged agenda-setting grouping headed by the US and the EU – struggle when trying to ensure that they receive level playing field conditions. The UK has been used to having its interests secured through being part of the EU delegation within the Quad. In future it will find itself outside the EU delegation and often face-to-face with the same people it will have tried and failed to negotiate Brexit with. The reproduction of existing trade deals but within a new non-EU context might thus prove to be far from straightforward.

The ‘no deal’ scenario would also clearly have implications for the way in which the UK was integrated into the structure of global finance. It would almost certainly lead to the loss of a lot of City business if banks located there subsequently had to give up their right to operate in euro-denominated markets. This would not necessarily mean that the financial sector would shrink to bring about a long overdue rebalancing of the UK economy away from an over-reliance on finance. Instead, we should expect to see an internal rebalancing within the City, as some sectors rise to greater prominence, most likely those that provide confidential services to non-residential clients. As Commissioner for Internal Market and Services, Barnier attempted to address broader concerns that emerged from some markets within the single European financial space enjoying offshore status. It would thus be a supreme irony if his actions as chief EU negotiator of Brexit were to push the City further towards specialising in offshore finance, having previously done everything in his power to legislate against this outcome.

There is, of course, an awful lot of guesswork going on here, and we will all have to wait to see what ultimately transpires.

Featured image credit: Houses of Parliament London by skeeze. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Brexit and Article 50 negotiations: why the smart money might be on no deal appeared first on OUPblog.

Skype meetings, coffee, and collaboration: a Q&A with Ariana Milligan

Ariana Milligan recently started working with Oxford University Press’s Global Digital Products Marketing team in New York. She tells us about how working on products such as Grove Art Online and Oxford Music Online creates an inspiring day-to-day life.

What is your typical day like at OUP?

My typical day is filled with skype meetings, coffee, and collaboration. I spend time researching ideas for creative campaigns, brainstorming for videos and podcasts, and learning about data’s role in marketing. My days are varied but in a good way.

What’s the most enjoyable part of your day?

I love walking to Bryant Park during my lunch hour.

What is the strangest thing currently on or in your desk?

I have ten or so postcards of paintings and pieces of art. Some of the pictures are from famous museums and some are not. I have a few poems pinned to my cubicle wall. I also have a lamp with a gold base and kelly green lampshade that I inherited from my team.

Image credit: Ariana Milligan, used with permission of the author.

Image credit: Ariana Milligan, used with permission of the author.What’s your favourite book?

I love John Dewey’s Art as Experience. I picked up a copy at the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia and couldn’t put it down. For inspiration and a sense of connection, I enjoy Jonathan Safran Foer’s Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close.

If you didn’t work in publishing, what would you be doing?

I think something along the lines of film restoration or story development. I love doing marketing for a publishing house because there is potential to create and elevate important stories. I love film for the same reason!

Who inspires you most in the publishing industry and why?

I’m inspired by a company called Deep Vellum Publishing, which is an independent not-for-profit publisher in Dallas, Texas. They’re dedicated to translation and cross-cultural exchange. Their passion for seeking truth and putting out inspiring content is really similar to that which I’ve encountered at Oxford.

What drew you to work for OUP in the first place? What do you think about that now?

I did a year abroad at St. Catherine’s College, which is a college at the University of Oxford. When I graduated from college, I knew I wanted to pursue something along the lines of film or publishing. Oxford University Press made the most sense due to my personal connection. Looking back, I’m lucky to have such an incredible institution play a pivotal role in my life as a student and young professional.

What is your favorite word?

Scintillate. It’s an elevated way to describe glittery things.

Favorite animal?

All of them, but koalas do top my list.

Image Credit: Opening title card for the 1902 Georges Méliès film Le voyage dans la lune, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Skype meetings, coffee, and collaboration: a Q&A with Ariana Milligan appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers