Oxford University Press's Blog, page 459

September 30, 2016

Whole grains for cancer prevention? Take the evidence with a grain…

Nutrition ranks high among the modifiable predictors of cancer— partially, due to its impact on obesity and diabetes, which are established risk factors for the most commonly occurring cancers. Diet is particularly important because unlike family history and genetic factors, it can be modifiable, potentially altering our cancer risk. In theory, changing our diet should give us greater control over our health and help us avoid the physical, emotional, and psychosocial consequences of a cancer diagnosis. However, the general public, clinicians, and public health professionals face challenges in accurately understanding the role of nutrition in predicting cancer risk due to perceived and real (conflicting findings in the scientific literature) inconsistencies.

An emerging field in the area of nutrition and cancer is the role of whole grains in cancer prevention. In a world where carbohydrates, particularly refined sources, are increasingly viewed as the culprit for obesity and associated chronic disease, are whole grains the safest carbohydrate to recommend for cancer prevention? Currently, consuming a plant-based diet containing whole grain foods such as whole-grain bread, pasta, breakfast cereals, and oats is part of the American Cancer Society and the American Institute for Cancer Research’s recommendations for cancer prevention. These recommendations are primarily based on a comprehensive review of existing studies on diet and nutrition in relation to cancer. Interestingly, these recommendations are similar to those for the prevention of other chronic diseases such as diabetes and heart disease, yet cancer prevention guidelines are more qualitative in nature with no quantitative guidelines currently in place, such as consuming half of grains as whole grains, as we see in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans or the DASH eating pattern recommended by the American Heart Association for improved heart health. Furthermore, these cancer prevention guidelines are not well integrated into preventive-care practice.

One main challenge in providing nutritional guidance to cancer patients is the inconsistencies in study findings. For whole grains, while most existing evidence points to a protective impact of whole grains on obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease and even mortality, most studies are suggestive of no association with cancer. However, there is some suggestion of a potential protective impact on the risk of gastrointestinal cancers, suggesting that the impact of whole grains may be more pronounced for certain cancer sites but this requires further investigation. Conflicting evidence can be attributed to methodological challenges inherent to nutritional epidemiology studies in oncology. For instance, traditional dietary assessment tools where not designed to measure whole grain intake, and therefore tend to underestimate intake. This, coupled with the low, narrow range of whole grain intake within the US population makes associations between whole grain and cancer difficult to assess. Another important issue to consider is the regulation of whole grain labeling. While significant progress has been made in the recent years in quantifying the whole grain content of food for food and nutrient databases, the labels of many products can be misleading. For instance, products that are labeled “made with whole grain” or even “multigrain” may in reality contain minuscule amounts of whole grains. This makes it challenging to quantify whole grain intake in research studies, and also makes it more difficult for consumers, who are advised to increase their whole grain intake for chronic disease prevention, to identify and consume whole grain products.

Bread, roll by TiBine. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Bread, roll by TiBine. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.Another important challenge is the absence of evidence on the potential differential impact of dietary exposures, particularly whole grains, on cancer across the life-course (in utero, childhood, adolescence, early-, mid-, and late-adulthood). This issue could potentially be of great relevance to tailoring dietary advice to life stage and intervening to advise individuals at critical periods during which dietary modification may be of importance to combat a future cancer diagnosis. In addition, there is a dearth of literature on the issue of potential racial differences in the associations between nutrition and cancer. Most studies on whole grains, for instance, have been conducted in primarily Caucasian populations. This necessitates additional research in other racial and ethnic groups to tailor public health guidance and individual-level counseling to these population groups that may experience unique social, economic, and cultural barriers that influence the adoption and maintenance of healthy behaviours such as consuming more whole grains.

Finally, it is important to keep in mind that diet is only one factor, albeit an important one, in the multitude of exposures such as hormones, body composition, physical activity, stress, aging, and broader psychosocial and environmental factors that impact cancer risk. Furthermore, the effect of a particular food or nutrient on cancer in most studies is mild to modest at best. Therefore, dietary advice on cancer should emphasize the importance of a comprehensive lifestyle approach that involves consuming a healthy diet, in the context of which whole grain consumption may be of benefit. Despite these challenges in providing nutritional guidance to cancer patients, in general, and on the issue of whole grains, in particular, the future of a clearer understanding of the role nutrition and diet in cancer risk is promising. The evolution of dietary assessment tools, identification of biomarkers, genetic information, diverse study cohorts, and refinement of data analysis techniques will enable us to develop an increasingly clearer understanding of the complexities of the relationships between diet, nutrition, and cancer. Furthermore, these advances are moving the field towards personalized nutrition, which will enable the tailoring of food and nutrient intake to individuals based on their genetic make-up, microbial environment, and metabolic response to foods.

The field of nutrition and cancer is ever-evolving, yet dietary guidance has not significantly changed over the years and continues to be in line with guidance for prevention of other chronic diseases, despite the inconsistencies in study findings on diet–cancer relationships. Although certain nutrients may be more beneficial or more detrimental to the risk of developing one chronic disease compared to others, ultimately, there is only one “good” diet. A healthy diet continues to be one that provides a variety of plant foods such as fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains and restricts energy-dense and processed foods and drinks. On the issue of how to best communicate the status of the evolving science on whole grains and cancer to the public, it is important to note that evidence-based recommendations for cancer are constantly evolving, but for the time being, the dietary advice is this: whole grains are good to eat and it doesn’t hurt that their food sources can be tasty too.

Featured image credit: Breads, cereals, oats. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Whole grains for cancer prevention? Take the evidence with a grain… appeared first on OUPblog.

Racing towards OHA2016 in Long Beach, the “International City”

As has become OHR tradition, we have enlisted the help of a local to serve as a guide to the upcoming OHA Annual meeting in beautiful Long Beach, California. Below, Mark Garcia shares some of the city’s fascinating history, as well as his personal recommendations for oral historians who want to venture out and see some of what the city has to offer. Mark will be milling around the conference to keep you up to date on social media about what’s happening on the ground. Make sure to follow the OHR on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, and Google+ for the latest from the annual meeting, and follow Mark at @HistoryBuffMark.

The official motto of the City of Long Beach is the “International City,” welcoming visitors from around the world to the port city. From humble beginnings, the city has grown to become the second busiest port in the United States, after Los Angeles. In 1880 William Ervin Willmore, an Englishman, laid out Willmore City along the Pacific Coast. He was unable to attract settlers and the city failed after a few years. The city was renamed Long Beach after its long wide coastal beach and the city was incorporated in 1888. In 1911 the Port of Long Beach was established and by 1919 portions of the United States Pacific Fleet were stationed off the coast. A major economic boom came to Long Beach with the discovery of oil in the Signal Hill area and it brought prosperity to the region.

“Long Beach, California” by Brian Roberts, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

“Long Beach, California” by Brian Roberts, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.To learn more about the local history, I recommend visiting the Historical Society of Long Beach’s current exhibition, Black Gold: Oil in the Neighborhood detailing the oil boom in the 1920s. The oil industry brought many new jobs and residents to Long Beach, as well as a million dollar a month building boom resulting in downtown skyscrapers. After years of growth, a 1933 earthquake rattled Southern California and killed 120 people. Many of the downtown buildings were lost or damaged, but the New Deal helped save the city and funded the rebuilding of the damaged buildings. You have the opportunity to view some of the buildings on the Downtown Long Beach Art Deco Walking Tour offered at the Annual Meeting.

Those interested in arts and culture will find a rich history and a city full of dynamic events. Long Beach is host to the longest running major “street” race, the third largest LGBTQ Pride parade, and the only art museum dedicated to modern and contemporary Latin American Art in the United States. The Annual Meeting offers a tour of the Museum of Latin American Art (MOLAA), which is currently celebrating its twentieth anniversary. Long Beach’s largest event, bringing up to 200,000 visitors, is the Toyota Grand Prix of Long Beach. Just two blocks south of the Renaissance Long Beach Hotel, host of the Annual Meeting, is the Long Beach Motorsports Walk of Fame. Take a short stroll and view the 22-inch medallions that honor key contributors and race winners in Long Beach Motorsports. Of course the main attraction this October is the OHA Annual Meeting, which includes panels on an incredible diversity of subjects.

Long Beach’s vibrant past and warm California weather make it a great location for the Annual Meeting, celebrating the theme of OHA@50: Traditions, Transitions and Technologies from the Field. We hope to see you at the annual meeting in two weeks, from October 12-16 – and don’t forget to bring your sunglasses!

Chime into the discussion in the comments below or on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, or Google+.

Featured image by Mark T. Garcia, used with permission.

The post Racing towards OHA2016 in Long Beach, the “International City” appeared first on OUPblog.

A Q&A with Lauren Jackson: Morrissey, MMA, and Megan Abbott

We sat down with Lauren Jackson – an Assistant Marketing Manager based in our New York office – to quiz her on her favourite words, her favourite books, and her favourite UFC fighter. We are delighted to welcome Lauren to the marketing team and are jealous of what she keeps in her desk drawer… You can find out more about Lauren below.

When did you start working at OUP?

I just started working here in August, and it’s marvelous.

What is the most important lesson you learned during your first month on the job?

There’s a few lessons I learned that all kind of roll together into one sentence: you don’t know as much as you think you know. I find it’s helpful to remind myself of that every day so I can open myself up to ask questions, experience new/strange ideas (and sometimes people), and, most importantly, constantly learn how to be better.

What was your first job in publishing?

My first official job in publishing was working as a publicity assistant over at Penguin Random House (then just the bird without the entropy). Before that I held various internships at magazines and independent presses.

Lauren at NY ComicCon (with Brent Spiner). Image used with permission.

Lauren at NY ComicCon (with Brent Spiner). Image used with permission.What are you reading right now?

Megan Abbott’s new novel, You Will Know Me, just landed on my desk today and I cannot wait to crack it open.

What’s your favourite book?

I have a dog-eared, well-worn copy of Play It As It Lays by Joan Didion on my bookshelf. I turn to it whenever I find myself in a period of change and uncertainty.

If you didn’t work in publishing, what would you be doing?

I’d probably be a professional MMA fighter… or at least I hope I’d be.

What’s the first thing you do when you get to work in the morning?

Turn on NPR and eat breakfast. Eating is the priority, though, considering I’m about a quarter hobbit. Second breakfast follows shortly after.

If you could change one thing about working for OUP, what would you change and why?

I’d add a gluten-free option to Bagel Fridays.

What’s the most surprising thing you’ve found about working at OUP?

Perhaps not surprising so much as humbling: how smart everyone is!

If you could trade places with any one person for a week, who would it be and why?

Probably my favourite UFC fighter, Joanna Jedrzejczyk, to know what it feels like to work out, fight, and train for a living. Or Morrissey (do I need to explain this one?).

What is your favourite word?

Mischievous. Or bananas.

What is in your desk drawer?

Snacks. (See my answer to question 7 for more details).

Featured image credit: Lauren before her first fight. Image used with permission.

The post A Q&A with Lauren Jackson: Morrissey, MMA, and Megan Abbott appeared first on OUPblog.

Very short facts about theVery Short Introductions

This week we are celebrating the 500th title in the Very Short Introductions series, Measurement: A Very Short Introduction, which will publish on 6th October 2016. they have proven to be extremely popular with general readers, as well as students and their lecturers. They are the perfect way to get ahead in a new subject quickly. Our expert authors combine facts, analysis, new ideas, and enthusiasm to make often challenging topics highly readable. To mark its publication editors Andrea Keegan and Jenny Nugee have put together a list of Very Short Facts about the series.

Between them the VSI titles cover every letter of the alphabet, with the letter ‘e’ appearing over 600 times.

The latest VSI was delivered 9 years later than the contract date.

VSIs have been translated into 50 languages, including Gujarati (an Indo-Aryan language) and Belarusian. Arabic is the most popular translated language.

Certain words, such as ‘discourse’ and ‘normative’, are banned from all new VSIs but the occasional one slips through.

When their VSIs published, the oldest VSI author was Stanely Wells at age 85, author of William Shakespeare: A Very Short Introduction .

There are no duplicate covers (yet!).

The first VSI, Classics , was published 21 years ago, in 1995 and remains in its first edition.

The highest selling VSI is Globalization , which will soon be on its fourth edition! When it was first proposed people were worried it might not be a success.

Someone once wrote in suggesting we needed a VSI to Olivia Newton John. Other suggestions have included coconuts and Harry Potter.

One VSI author had a tie made to match his cover. Unfortunately his cover then needed to be flipped around, so his tie is now upside down.

There are 84 VSI titles starting with “The”.

Discounting the word “The”, the most common initial letter of a VSI is ‘A’ (55 titles), followed closely by ‘C’ and ‘M’ (52 titles each).

So, where’s the gap in your knowledge? …

Image credit: Very Short Introductions © Jack Campbell-Smith, taken for Oxford University Press.

The post Very short facts about theVery Short Introductions appeared first on OUPblog.

September 29, 2016

Is happiness in our genes?

It is easy to observe that some people are happier than others. But trying to explain why people differ in their happiness is quite a different story. Is our happiness the result of how well things are going for us or does it simply reflect our personality? Of course, the discussion on the exact roles of nature (gene) versus nurture (experience) is not new at all. When it comes to how we feel, however, most of us may think that our happiness must be more strongly influenced by situational factors than our genes. But could it be that some people are happier than others simply because they inherited genes that make them generally feel better regardless of whether they had a good or a bad day? In other words, could being lucky in the genetic lottery be more important for our happiness than whether we get to travel to exotic places or enjoy the company of loving friends? Fortunately, we are now able to consider this age-old debate from a scientific rather than a merely philosophical perspective. So what does science tell us about the origins of individual differences in happiness?

Much of classic research on the role of genes is based on twin studies. Rather than looking at actual molecular differences in the DNA, these studies compare similarities between identical and fraternal twins. Given that identical twin siblings are genetically more similar to each other than fraternal twins, it is possible to statistically estimate how much of the differences between people can be explained by heritable (i.e. genetic) versus environmental factors.

The first twin study that focused on people’s positive feelings reported a genetic contribution of about 40%, which means that 40% of the differences in positive emotionality between people is explained by heritable factors (i.e. differences in the degree of relatedness between people). Recently all available twin studies on happiness have been combined into one single study. The results support the original finding that on average about 40% of the differences in happiness between people is explained by genetic factors while the remaining 60% are accounted for by the environment. However, while twin studies indicate how much of the difference in happiness is explained by genetic factors, they don’t inform us about the specific genes that are involved.

DNA Microbiology Analysis by PublicDomainPictures. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

DNA Microbiology Analysis by PublicDomainPictures. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.Due to twin study findings, we have known for many years that happiness has a significant genetic component, but it is only recently that technological progress enabled scientists to investigate happiness on the molecular level. Many of these new studies apply a genome-wide approach. This usually includes the measurement of up to several millions of genetic differences across the whole genome. This vast molecular data can then be used to estimate the average total genetic contribution to a specific trait. When applied to well-being, it has been found that 12-18% of differences in well-being between unrelated people is explained by the combined effect of more than 500,000 common genetic variants. The identification of the specific gene variants that make up this genetic component requires very large samples which have not been available until very recently.

Earlier this year, the hitherto largest study on the genetics of happiness has been conducted with a sample of almost 300,000 people. The study was successful in identifying three different genetic variants, two in chromosome 5 and one in chromosome 20. However, these happiness-related gene variants explained less than 1% of happiness differences between people. This is a lot less than the 40% twin studies suggested. How can we explain this difference? Besides a range of methodological and technical reasons, the conflicting results between twin and molecular studies suggest that although happiness has a genetic component, it is made up of many gene variants with very small effects on happiness. In other words, there is no “happiness gene” but many thousands of gene variants that contribute to observed stable differences in happiness. The individual contribution of these variants is so small that it is extremely difficult to measure.

In other words, could being lucky in the genetic lottery be more important for our happiness than whether we get to travel to exotic places or enjoy the company of loving friends?

It is important to clarify that genes and experiences are intertwined in complex ways. For example, our genes make certain experiences more likely and experience, on the other hand, can influence the function of our genes through epigenetic mechanisms. Recent studies also suggest that our genes may influence how strongly we respond to the experiences we make. In other words, some people are characterised by a genetic sensitivity which makes them more likely to feel happy when they experience something positive compared to other people who are genetically less sensitive.

In conclusion, while experience is certainly important for our well-being, some of our happiness is indeed in our genes. However, there is no magic “happy gene” but rather thousands of gene variants, each making a tiny contribution to our happiness. Although the complex interplay between genes and experience is likely to play a central role for our happiness, this has not been investigated in great detail yet. More research is required to help us better understand the role genes play for our happiness.

Featured image credit: Joy of Life by ludi. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Is happiness in our genes? appeared first on OUPblog.

Rebuilding and restoring the Houses of Parliament [timeline]

The Houses of Parliament in London is one of the most famous buildings in the world, and one of the capital’s most photographed landmarks. A masterpiece of Victorian Gothic architecture which incorporates survivals from the medieval Palace of Westminster (destroyed by a fire in 1834), it was made a World Heritage Site by UNESCO along with Westminster Abbey, and St Margaret’s Church, in 1987. With its restoration and renewal in the news, find out more about the background of the Houses of Parliament in this interactive timeline.

Featured image credit: The Palace of Westminster at night as seen from the opposite side of the River Thames by David Iliff. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Rebuilding and restoring the Houses of Parliament [timeline] appeared first on OUPblog.

Secrets and trivia from the Broadway stage

Why do some great Broadway shows fail, and mediocre ones thrive? How does the cast onstage manage to keep tabs on the audience without missing a beat or a line? Ken Bloom, author of Show and Tell: The New Book of Broadway Audiences, delves into the inner workings of the Broadway stage and the culture surrounding Broadway hits and flops. In the Youtube videos below, learn how the actors on stage interact with the audiences (sometimes without them even realizing it) and even toy with them, and why some less-than-great plays or musicals still manage to become beloved hits.

Ken Bloom on Broadway audiences

Ken Bloom on Broadway flops

Featured image: part of the cover of Show and Tell: The New Book of Broadway Anecdotes.

The post Secrets and trivia from the Broadway stage appeared first on OUPblog.

Into the unknown: professional development for future educators

One of the greatest challenges faced by schools and universities today is preparing students for an unknown future. Our graduates will likely have multiple careers, work in new and emerging industries, grapple with technologies we can’t even imagine yet. And so we’re asking our staff to equip students with the skills they need to thrive in a potentially very different world to the one we live in now.

A decade ago, when I was at university, I don’t remember anyone talking about ‘graduate attributes’. Today there’s a much greater emphasis on transferable skills, rather than just subject knowledge. Working as an Educational Designer at the University of Canberra (UC), I have the opportunity to engage in initiatives around authentic assessment, scenario-based learning, students as partners/generators, work-integrated learning… These will help us to support our students in developing the skills that they need, not just to secure a job in the short term, but to enjoy a fulfilling and varied career in the longer term.

Earlier this year, students taking a course in Artificial Intelligence at Georgia Institute of Technology discovered that Jill Watson, one of their Teaching Assistants, was an AI creation. ‘Watson’ was able to participate in online forum discussions, answering students’ routine questions, posting reminders about deadlines, and introducing mid-week conversation topics to encourage students to share their thoughts. It’s exciting to think of the potential benefits of this kind of technology, but it also leads us to question the role of the (human!) educator and for some the concept of technology-enhanced learning can seem threatening, encroaching on their professional identity as a teacher.

Today there’s a much greater emphasis on transferable skills, rather than just subject knowledge.

So how can we support our staff in this time of uncertainty and disruption in the sector?

On 5 July 2016, the University of Canberra’s Teaching and Learning team launched a new Graduate Certificate in Tertiary Education (GCTE). In one of the first activities in the course, we invite participants to engage with the Australian Higher Education Industrial Association’s Australian Higher Education Workforce of the Future Report, released earlier this year. The report examines the changes universities will need to make in order to thrive in an increasingly globalised and competitive space and highlighted the need for an “agile workforce” which would be “sufficiently flexible, specialised and self-renewing to be properly responsive for changing stakeholder expectations”. We invite our staff to engage with this report, to take stock of their experience, identify development needs, and articulate their future trajectory.

In other words, we want our staff to reflect on where they are now, where they see themselves in ten or fifteen years’ time, and how they’re going to get there.

We need our staff to be lifelong learners, to reflect on their practice, collaborate with colleagues, students and the broader community, experiment with new tools and technologies, act as advocates and promote best practice. We hope that the new GCTE will help them to do this, as well as providing formal recognition of the amazing work our staff do at UC.

A version of this blog post first appeared on Epigeum Insights.

Featured image credit: Student-typing-keyboard, by StartupStockPhotos. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Into the unknown: professional development for future educators appeared first on OUPblog.

September 28, 2016

The origin of the word SLANG is known!

Caution is a virtue, but, like every other virtue, it can be practiced with excessive zeal and become a vice (like parsimony turning into stinginess). The negative extreme of caution is cowardice. Although in dealing with historical linguistics, one should beware of jumping to conclusions, sometimes explorers succeed in revealing the truth, and then the time comes for accepting it.

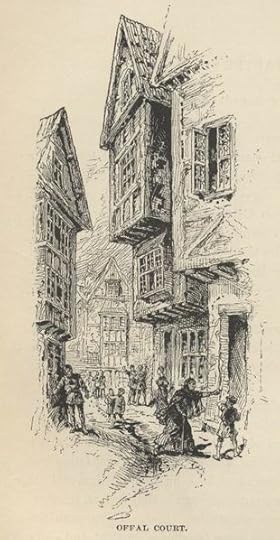

Slang, an overlay on standard language, has always existed, but the English word slang, as we know it, is recent: the earliest citations in the OED go back to the second half of the eighteenth century. That the very name of slang may emerge as a slang word need not surprise us (the origin of argot and cant provides a good parallel), and this makes its source even harder to discover, for slang tends to be born in places like Offal Court and disguise its shabby pedigree. Only a hundred years ago, slang was castigated as something unseemly and vulgar, but the war declared on it had as little chance of success as the war waged against John Barleycorn. However, today my subject is not the history of mores or usage but etymology.

This is Offal Court. Not only Mark Twain’s Tom Canty and his sisters but tons of slang were born there.

This is Offal Court. Not only Mark Twain’s Tom Canty and his sisters but tons of slang were born there.Rather many people have tried to discover the origin of slang, and in 1898 the puzzle was all but solved. The relevant note by John Sampson appeared in a local periodical called Chester Courant and later reprinted in The Cheshire Sheaf. I would probably never have discovered it, even though I did screen dozens of local magazines for my database, if John M. Dodgson had not referred to it in his tiny 1968 article in Notes and Queries. Dodgson did not pay much attention to the word slang, for his topic was Cheshire place name elements, but, when I read Sampson’s explanation, I realized that the mystery was no more. All I had to do was to add a few finishing touches.

Cheshire is famous not only for its cat and cheese.

Cheshire is famous not only for its cat and cheese.In my 2008 dictionary, I devoted an entry to slang and gave my predecessor (actually, two of them: see below) full credit for their discovery. On several websites I now find mentions of the etymology ascribed to me (though I am not its discoverer), but they are brief and noncommittal. At this rate of going, we’ll never make progress. Inspired by the belief that the explanation I defend is not just one of many to be considered but the true one, I decided to return to the question that no longer interests me but may interest some other people. And I’d like to ask: “Why are people so cautious? Why do they hedge instead of celebrating a small victory?” Perhaps because sitting on the fence (or on the hedge, or wherever) is safe, while defending an opinion that has not yet become common property is risky. I would not have fought with such vigor for my own conclusion, but it is not mine, and I feel obliged to break a lance for those who can no longer do so themselves.

In Murray’s OED, in addition to slang having the sense today known to everybody, we find slang “a narrow strip of land,” alternating with sling, slanget, slanket, slinget, and slinket, all of them meaning “a long narrow strip of land.” We should use a more precise definition of slang, namely “a narrow piece of land running up between other and larger divisions of ground.” It is the idea of delimiting a certain territory that should not escape us, especially because Slang is a common field name in northern England. The regional verb slanger means “linger, go slowly.” That verb is of Scandinavian origin. Its cognates are Norwegian slenge “hang loose, sling, sway, dangle” (gå og slenge “to loaf”), Danish slænge “to throw, sling; wave one’s arms, etc.,” and Swedish slänga. Their common denominator seems to be “to move freely in any direction.” German Schlange “snake” confirms that idea, for snakes writhe.

Of special interest is the form slanget, cited above. To any unprejudiced observer it looks like a noun of some Scandinavian language with the postposed definite article (slang-et), the slang. Danish slænget and Norwegian slenget mean “gang, band,” that is, “a group of strollers.” Old Icelandic slangi “tramp” and slangr “going astray” (said about sheep) are close enough. It is not uncommon to associate the place designated for a certain group and those who live there with that group’s language. John Fielding and the early writers who knew the noun slang used the phrase slang patter, as though that patter were a kind of talk belonging to some territory. One of Tony Lumpkin’s companions (in Goldsmith’s She Stoops to Conquer), a horse doctor, has the name Jack Slang. Much to our regret, he does not appear in the play, but he was probably a jack of all trades and a tramp. Tony was not evil but disreputable.

James Platt (who was unaware of Sampson’s ideas) offered the following reconstruction: from slang “a piece of delimited territory” to “the territory used by tramps for their wandering,” “their camping ground,” and finally to “the language used there.” If we tried to add a classificatory label to that slang, it would end up with words like “turf” and “policeman’s beat.” (As regards the sense development, think of how turf “grass” came to mean “horse race,” that is, an activity happening on the grass.) Quite possibly, speakers of northern English heard the phrase på slanget (or slænget) “out on the slang” and replaced the preposition. Those who travelled “on the slang” (hawkers, hucksters) were themselves called “slang” (compare Icelandic slangi “tramp” and Norwegian slenget ~ Danish slænget “gang,” cited above). Traveling actors too were “on the slang.”

A salesman out on the slang.

A salesman out on the slang.“Slangs” were competitive, the way gangs’ territories always are, with different groups of strolling actors, itinerant mendicants, “badgers,” and thieves fighting for the spheres of influence. Hence slang “hawker’s license, a permit that guaranteed the person’s right to sell within a given “precinct” (or slang!), and slang “humbug,” which is a predictable development of peddlers’ activities, for mountebanks cannot be trusted. Both senses appear in the OED. Hawkers use a special vocabulary and a special intonation when advertising their wares (think of modern auctioneers), and many disparaging, derisive names characterize their speech; charlatan and quack are among them.

Such then is the history of the noun slang. It is a dialectal word that reached London from the north and for a long time retained the traces of its low origin. The route was from “territory; turf” to “those who advertise and sell their wares on such a territory,” to “the patter used in advertising the wares,” and to “vulgar language” (later to “any colorful, informal way of expression”). Few English words of disputable origin have been explained so convincingly, and it grieves me to see that some dictionaries still try to derive slang from Norwegian regional slengja “fling, cast” or the phrase slengja kjeften “make insulting allusions” (literarally “sling the jaw”), or from the old past tense of sling (that is, from the same grade of ablaut as the past tense of sling), or from language with s– appended to it (even if the amazing similarity between slang and language helped slang stay in Standard English, for many people must have thought of some hybrid like s-language). All those hypotheses lack foundation. The origin of slang is known, and the discovery made long ago should not be mentioned politely or condescendingly among a few others that stimulated the research but now belong to the museum of etymology.

Image credits: (1) “The Prince and the pauper 02-028” by Merrill, Frank Thayer Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons (2) “Cheshire Cheese” by Y6y6y6, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons (3) “Arthur Rackham Cheshire Cat” by Arthur Rackham, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons (4) “An old itinerant salesman offering the repair of defect umbrellas” by J.T. Smith, CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons Featured image: Texting, mobile by Dean Moriarty, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The origin of the word SLANG is known! appeared first on OUPblog.

New York City’s housing crisis

New York City is the midst of a housing affordability crisis. Over the last decade, average rents have climbed 15% while the income of renters has increased only 2%. The city’s renaissance since the 1990’s has drawn thousands of new residents; today, the population of 8.5 million people is the highest it has ever been. But New Yorkers are finding that the benefits of city living are not without its costs. The demand for housing has outstripped the real estate community’s ability to supply it; as a result, prices have been rising.

Mayor Bill de Blasio, upon taking office in 2014, has made expanding affordable housing a key part of his policy agenda. The objective is to preserve or build 200,000 units for those in the lowest income brackets over the next 10 years. At the end of July, de Blasio announced that the plan was ahead of schedule, having supported the creation or preservation of 53,000 affordable apartments. The Wall Street Journal ran the glowing headline, “Affordable Housing Surges in New York City”.

Unfortunately, de Blasio’s plan ignores the economic realities in favor of more politically palpable and piecemeal solutions. First is the increased reliance on the city’s rent stabilization program, and the second is tinkering with zoning rules to incentivize the construction of low income units in specific neighborhoods. His plan does little to promote housing affordability citywide, and, as long as the population keeps growing, rents will keep rising.

Rent stabilization and the current zoning laws were enacted as post-World War II programs. They were responses to the problems that the city was facing in the middle of the 20th century. But over a half-century later, well into the 21st, the city is still relying on outdated policies because it is the path of least resistance for policy makers. But the future of New York and the affordability of its housing depends on resident’s willingness to rethink these policies and engage in a dialogue about broader plans to carry New York forward.

As part of his plan, de Blasio has made deals with large landlords to keep their units rent stabilized for years to come. The rent stabilization program, dating from 1969, was an outgrowth of the city’s rent control program, which was an expedient enacted during World War II to address the city’s housing shortage. Today, about half of the city’s renters are in rent stabilized units, which offers two key benefits. First is that these apartments are not subject to market rate rent changes. Rather, each year, the Rent Guidelines Board meets and chooses the maximum rent increase that landlords can charge. For the past two years, the Board has prohibited landlords from raising their rents for one-year leases. Second is that renters have the statutory right to renew their leases; which means that only they, but not landlords, can decide when to terminate a lease.

While rent stabilization is good for those who have it, it contributes to the affordability problem. By restricting prices in half in the rental market, it makes prices in the non-regulated sector higher than they would be otherwise, driving developers to focus on luxury highrises, at the expense of middle-income housing. Higher prices in the non-regulated sector makes a rent stabilized unit that much more of a better deal. This contributes to lower turnover in these units and essentially ensures that landlords will be unable to empty their building to tear them down to construct more housing in the city—housing that they would otherwise be happy to provide given the demand for it. This is one of the reasons that today, 75% of the city’s apartment buildings were built before 1932.

The second problem with de Blasio’s plan is that it tinkers on the margins with the zoning rules. Today’s regulations were enacted in 1961, and were a major re-writing of the first set of zoning rules enacted 45 years previously, in 1916. The rules don’t limit building height per se, but rather limit a building’s bulk; each neighborhood is effectively placed under a kind of “bubble” that restricts how much housing could be provided in that neighborhood. De Blasio’s plan includes rezoning (called upzoning) a handful of neighborhoods so that developers can build taller buildings; in exchange for this right, they must, in turn, set aside a certain fraction of units for those in the lower income brackets.

As the map below shows, large swaths of the city have rather extreme zoning limits. The map shows by zip code how much housing can be built, on average, per square foot of lot; this is called the Floor Area Ratio (FAR). A neighborhood with an average FAR value less than one, for example, means that builders can only be expected to construct one family house with ample backyards. Relatively modest changes in the zoning restrictiveness across the entire city will likely have a much greater impact on housing affordability than adjustments in a few a selected neighborhoods, which residents are increasingly resenting as what they see as unfair treatment by the government.

Zoning Restrictions by Jason M. Barr. Used with Permission.

Zoning Restrictions by Jason M. Barr. Used with Permission.Given the high cost of construction (and demolition) and zoning restrictiveness, landlords will not tear down older structures, since they cannot replace them with more housing that would recoup the costs of providing it. The only meaningful way to incentivize more housing construction is to allow landlords the chance to earn an income from buildings that can accommodate more families. Once this happens, housing costs in the city will become more affordable, at all income brackets. In short, real affordability will emerge when government policies are designed to promote housing construction in all neighborhoods across the city, rather than simply focusing on a magic number.

Featured image credit: New York Skyline by Mark Ittleman. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post New York City’s housing crisis appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers