Oxford University Press's Blog, page 461

September 25, 2016

Brexit and article 50 negotiations: What it would take to strike a deal

In the end, the decision for the UK to formally withdraw its membership of the European Union passed with a reasonably comfortable majority in excess of 1¼ million votes. Every one of the 17.4 million people who voted Leave would have had their own reason for wanting to break with the status quo. However, not one of them had any idea as to what they were voting for next. It is one of the idiosyncrasies of an all-or-nothing referendum that you can campaign wholeheartedly against the reproduction of existing conditions whilst sidestepping altogether the responsibility of saying what you would put in their place.

And so we arrive at where we are now, but where that is precisely is anyone’s guess. The full implications of Brexit will not be known until after Article 50 has been formally triggered, the UK announces the role it envisions the EU playing in its new mode of insertion into economic globalisation, and the European Commission and European Council of Ministers confirm whether they find that role acceptable.

In the meantime Theresa May and her economic ministers have tried to govern through reassurance. They have been repeatedly signalling to the rest of the world that the UK remains open for business and that the existing outward-facing orientation of the economy will not change. Indeed, on strictly economic matters they are hinting that they will be asking for something approaching the status quo mark two. This is what the Government thinks powerful economic interests want to hear. British businesses that trade overseas certainly do not want to relinquish their current priority access to the EU’s half a billion consumers; many foreign direct investors only set up in the UK in the first place because of the right of free entry into the European single market; and UK-based banks want to retain the ‘passport’ rights that allow them to operate without restriction across the EU. If they are all to get want they want out of the Article 50 negotiations, then the globalisation of the UK economy in the post-EU era will need to look remarkably similar to the globalisation of the UK economy prior to 23rd June. Yet this would come as a mighty disappointment to many Brexit voters who have felt let down by the preceding elite consensus in favour of a globalisation that they have experienced as accelerating economic insecurity.

It therefore appears that the route to a deal passes through something that proved impossible during the referendum campaign itself. The May Government needs to know what it wants to ask for before invoking Article 50, but irrespective of what that turns out to be it seems to require reconciling fundamentally irreconcilable positions. The UK is currently economically divided to such an extent that the image of a gaping chasm is hard to dismiss. There are those who do so badly out of the current mode of insertion of the UK economy into globalisation that the EU referendum became their sole means of crying, ‘Enough!’ There are also those who do so well out of the existing state of affairs that they are likely to simply walk away from the UK if things change too much. The choice for the May Government is either to ignore the claims of the former group, which would leave it vulnerable to the accusation of acting as if the referendum had never happened, or to ignore the claims of the latter group, to which it is closely aligned politically and otherwise lionises as the country’s indispensable ‘wealth-creators.’

EU United Kingdom problem by Elionas2. Public domain via Pixabay.

EU United Kingdom problem by Elionas2. Public domain via Pixabay.It is therefore highly unlikely that everyone will receive the outcome that they think reflects what they voted for on 23rd June. Perhaps this is merely the nature of an all-or-nothing referendum, but it does back the May Government into a corner. It is inconceivable that it will present as its favoured negotiating position something that does not feel like a definitive Brexit, because the Prime Minister will be eager to keep off her back the unholy trinity of UKIP nativists, her own rowdily anti-European backbenchers, and the country’s right-wing media tycoons. In relation to continued access to the European single market, though, she will hope that she can pull off the smoke-and-mirrors trick of negotiating something that feels like a definitive Brexit but in practice does not act like it.

However, the omens are not promising. Access to the single market that replicates an EU member’s terms of entry comes with significant costs attached.

In the most straightforward sense it is necessary to pay what might be seen as a subscription fee for those terms. Current precedent suggests that the fee will be almost as high in per capita terms as the contributions that the UK has recently been making to the EU budget as a full member state that has a guaranteed seat at every decision-making table. As so much fuss was made during the referendum campaign about how much money Brussels siphons off from London, the subscription fee for full access to the single market is likely to be a deal breaker on its own. This is before anyone from the UK Government begins to talk to Commission officials about finding a common ground on single market access, which the latter have already made clear will entail accepting the existing treaty obligation to respect the free movement of people. They have appointed to the role of chief EU negotiator Michel Barnier, a two-time Commissioner with the reputation throughout Whitehall as a hard-core federalist. This will ensure that treaty obligations will not be up for discussion from the Commission’s side. At the same time, however, May has already signalled that she is interpreting the referendum result as a decisive rejection of the principle of the free movement of people.

It thus becomes prudent to contemplate that there might be no available compromise between competing visions about the preferred way ahead.

Featured image credit: Chess king match by SteenJepsen. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Brexit and article 50 negotiations: What it would take to strike a deal appeared first on OUPblog.

The development of urban nightlife, 1940s hipsters, & the rise of dating

Cities in the early days of the United States were mostly quiet at night. People who left the comfort of their own homes at night could often be found walking into puddles, tripping over uneven terrain, or colliding into posts because virtually no street lighting existed. Urban areas had established curfew times that “were signaled by the ringing of bells, the beating of drums, or the firing of cannons” at an early hour in the evening. With the advent of gas lighting, culture transformed in fascinating ways. Here are 12 interesting facts about urban nightlife from Peter C. Baldwin’s article for the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History, which shows how times have greatly changed and, remarkably, how some things have remained the same.

Before 1830

1. The Christmas season was an especially popular time for drunken rowdiness at night. Somewhat like 20th-century trick-or-treaters, young men in early 19th-century Philadelphia and New York knocked on doors demanding drinks or small gifts.

2. Plays were banned in New England cities, forcing traveling troupes to bill their performances as “moral dialogues.”

3. Theater audiences used to talk amongst themselves much of the time during performances. With the house lights kept up, audiences paid as much attention to socializing and people-watching as to the performance.

1830–1880

4. With the rise of industrialization, workers could no longer take unscheduled breaks, but had to work steadily. As a result, leisure activities like going for a round of drinks began to be pushed out of the day and into the night.

“9:30 P.M. A common case of ‘team work.’ Smaller boy (Joseph Bishop) goes into [one of the?] saloons and sells his last papers. Then comes out and his brother gives him more. Joseph said, ‘Drunks are me best customers.’ ‘I sell more’n me brudder does.’ ‘Dey buy me out so I kin go home.’ He sells every afternoon and night. Extra late Saturda[y. At] it again at 6 A.M. Sunday, Hartford, Conn.” by Lewis Hine. Public Domain via the Library of Congress.

“9:30 P.M. A common case of ‘team work.’ Smaller boy (Joseph Bishop) goes into [one of the?] saloons and sells his last papers. Then comes out and his brother gives him more. Joseph said, ‘Drunks are me best customers.’ ‘I sell more’n me brudder does.’ ‘Dey buy me out so I kin go home.’ He sells every afternoon and night. Extra late Saturda[y. At] it again at 6 A.M. Sunday, Hartford, Conn.” by Lewis Hine. Public Domain via the Library of Congress.5. With gas lights in commercial districts and professional police forces replacing poorly-trained and unmotivated night watchmen, growing safety was a key factor in encouraging evening street activity. Restaurants, ice cream parlors, and oyster saloons clustered in the well-lit commercial streets.

1880–1920

6. Hours of work and leisure grew less distinct in the late 19th century. The number of night workers greatly expanded, partly because of the adoption of new processes of continuous production in the iron, glass, paper, and petrochemical industries. These processes were facilitated by the availability of electric power after about 1880, and by the superiority of electric lighting. Better lighting also encouraged additional night work on the docks, and in the manufacturing of textiles and books.

7. A gradual decline in labor hours, slow increases in income, and dwindling moral opposition to commercial entertainment also contributed to the expansion of nightlife. Electric lighting further encouraged the growth of commercial nightlife. In the “bright-light districts” of Chicago, Minneapolis, and many smaller cities, brilliant illumination made downtown streets seem safer and more

exciting. Advertising signs, theater marquees, and glowing store windows added to the flood of light from arc and incandescent street lamps.

8. Nightlife at the very end of the 19th century began to shift decisively away from a male dominated scene. Alternative nightlife options to the all-male “homosocial”

saloons developed. Mixed-gender restaurants and increasingly lavish hotel dining rooms

opened for business, and vaudeville houses succeeded in attracting a mixed-gendered mass audience.

9. Changes in patterns of courtship encouraged mixed-gender nightlife as well. Instead of courting young women in private, men in the 20th century began taking them out on “dates” to public entertainment places such as restaurants, theaters, and dance halls. Dating freed young couples from parental supervision, a development assisted greatly by the advent of the automobile.

1933–1965

10. The invention of television decreased the number of people who went out in urban areas. Watching TV with one’s family became a popular alternative to going out at night. Total movie admissions plummeted from 4.1 billion in 1946 to 1.1 billion in 1962.

11. In the late 1940s and 1950s, bebop jazz performances flourished in smaller nightclubs filled with hipsters. Young hipsters at the time listened to bebop jazz, which offered innovative but less danceable music. They sneered at the conventionality of mainstream society, welcomed the sexuality that they associated with black culture, and, in many cases, supplemented their listening experience by using marijuana and heroin. As the dance culture of young whites came to focus on rock, bop fans preferred just to listen to this increasingly intellectualized art form.

12. Rock concerts in Boston were banned at one point. After a minor riot took place outside the Boston Arena on 3 May 1958, Boston police arrested concert promoter and disc jockey Alan Freed, and then Boston Mayor John B. Hynes briefly called off similar musical performances.

Featured image credit: “52nd Street, New York, N.Y., ca. July 1948” by William Gottlieb. Public Domain via The Library of Congress.

The post The development of urban nightlife, 1940s hipsters, & the rise of dating appeared first on OUPblog.

Back to philosophy: A reading list

Are you taking any philosophy courses as part of your degree this year? Or are you continuing with a second degree in philosophy? Then look no further for the best in philosophy research. We’ve brought together some of our most popular textbooks to help you prepare for the new academic year. From Plato to Descartes, ancient wisdom to modern philosophical issues, this list provides a great first stop for under-graduate and post-graduate students alike.

Under-graduate:

Context and Communication by Herman Cappelen and Josh Dever

Does the meaning of a question change dependent on how it’s asked? Is the meaning of a thought changed by how we think about that thought? Students of linguistics and philosophy of language will benefit from this introduction to literature, theories, and discussions surrounding the concept of “context” in communication.

Philosophy of Social Science: A New Introduction edited by Nancy Cartwright and Eleonora Montuschi

Social science and philosophy students will benefit from this guide to some of the more complex topics currently discussed in this dynamic field. Covering hot-button issues such as climate change and social well-being, questions about objectivity including feminist theory, and methodological perspectives including interdisciplinarity, each expert explores each topic presenting the groundwork for further study in the field.

Philosophical Devices

Philosophical DevicesDescartes: An Analytic and Historical Introduction, Second Edition by Georges Dicker

Cogito ergo sum – I think therefore I am – is arguably René Descartes most memorable conclusion from his masterpiece Meditation on First Philosophy. Any philosophy course is sure to cover Descartes and the profound impact he had on philosophical inquiry. Including improved treatments of the cogito and the problem of the Cartesian Circle, this commentary introduces undergraduates to the famous “father of Western philosophy”.

On Loyalty and Loyalties: The Contours of a Problematic Virtue by John Kleinig

Loyalty is often thought of as the most important virtue on which all relationships are based. Friends, family, work, country, and God all demand absolute and unquestioning loyalty. As one of the few full-length studies on this virtue, this volume will present students of moral theory with an alternative view to the common perception that loyalty is an ever-positive virtue.

Philosophical Devices: Proofs, Probabilities, Possibilities, and Sets by David Papineau

Plato: Laws 1 & 2

Plato: Laws 1 & 2Beginning a course in philosophy this year? Then this is a must-have title to get started. Designed for all students of philosophy from introductory levels, Papineau explains key technical ideas whose meanings are often taken for granted in contemporary writing. Dispensing with long explanations, Philosophical Devices covers the basics in a way that’s accessible to all.

Post-graduate:

The Equality of the Sexes: Three Feminist Texts of the Seventeenth Century by Desmond M. Clarke

Move over Beyoncé, the seventeenth century witnessed the first publications that argued for the equality of men and women. Post-graduate students in early modern philosophy, history, and literature alike can learn from Marie le Jars de Gournay, Anna Maria van Schurman, and François Poulain de la Barre, whose three feminist tracts transformed the language and conceptual framework in which questions about women’s equality or otherwise were subsequently discussed.

Plato: Laws 1 and 2 Translated with an introduction and commentary by Susan Sauvé Meyer

Plato. Is there a figure in more philosophy with greater renown? Advanced students in ancient philosophy and classics will appreciate this new translation of Plato’s Laws, 1 and 2. The commentary lays bare the structure of the argumentation, illuminates the philosophical issues, and explains difficult passages, making accessible this complex and intricate work.

The Multiple Realization Book

The Multiple Realization BookCausation: A User’s Guide by L. A. Paul and Ned Hall

Neither common sense nor extensive philosophical debate has led us to anything like agreement on the correct analysis of the concept of causation, or an account of the metaphysical nature of the causal relation. Until now. Causation: A User’s Guide guides students of metaphysics and the philosophy of science through the most important philosophical treatments of causation, negotiating the terrain by taking a set of examples as landmarks.

The Multiple Realization Book by Thomas W. Polger and Lawrence A. Shapiro

Philosophy of mind students will benefit from the first book-length investigation of multiple realization. Sophisticated and empirically informed arguments cast doubt on the generality of multiple realization in the cognitive sciences. Meanwhile, the authors offer an alternative framework for understanding explanations in the cognitive sciences, as well as in chemistry, biology, and other non-basic sciences.

Aristotle: De Anima by Christopher Shields

Lastly, but certainly not least, this translation and commentary of Aristotle’s De Anima, will be of interest to philosophers at all levels. The commentary addresses itself to the reader who wishes to understand and assess Aristotle’s accounts of the soul and body; perception; thinking; action; and the character of living systems. Presenting controversial aspects of the text in a neutral, fair-minded manner, readers can form their own judgments.

Featured image: Statue Herodot by morhamedufmg, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Back to philosophy: A reading list appeared first on OUPblog.

September 24, 2016

The quest for order in modern society

Opening the morning paper or browsing the web, routine actions for us all, rarely if ever shake our fundamental beliefs about the world. If we assume a naïve, reflective state of mind, however, reading newspapers and surfing the web offer us quite a different experience: they provide us with a glimpse into the kaleidoscopic nature of the modern era that can be quite irritating. What, after all, are we to make of the fact that a report on shark attacks figures next to news about recent elections, that stock exchange rates follow a feature on pollution in China — and that the horoscope, weather forecast, cat pictures, and news on scientific discoveries are all part of the same paper or social media feed?

Exposing oneself to the ever accelerating, dispersed flow of information is like moving too close to a pointillist painting. Inadvertently, we feel the need for form, structure, and meaning — for distance to create the ‘bigger picture’. Indeed, the search for unity, cohesion, and some underlying principle or ‘meaning’ is perhaps the single most fundamental challenge of modern societies. In a sense, we could write the history of the past two centuries as a history of bringing order to an exploding complexity.

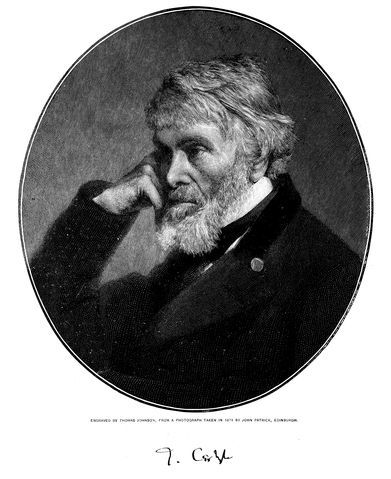

Not just to understand the past but also to understand where we stand today, it is worth discussing how past generations have addressed the issue of ordering and finding meaning in a modern era that is “sick and out of joint,” as British author Thomas Carlyle put it in an essay in 1829.

In fact, the gaze into the depths of modernity was much more dizzying in the ‘long’ nineteenth century — the years between 1789 and 1914 — when humans were first catapulted into a restless age of energy and acceleration. Skeptics like Friedrich Nietzsche perceived of modernity as penetrating the eyes of people with “too much light,” causing ignorance in the more simple minds and disgust in the more subtle ones. Others like James Joyce or Marcel Proust attempted to come to terms with modernity by exploring its myriad aspects and contradictions. They produced beautiful prose, leaving their contemporaries in awe but with little sense of direction. In turn, urban planners and state bureaucrats, themselves modern creatures, increasingly used science and modern technology to reshape modern society along more coherent or ‘rational’ lines. Reconstructing cities, building up armies, and ‘inventing’ nations, they sought to press the conundrum of modern society into the rigid structures of grid plans, battalions, and perennial human cultures, civilizations, or races.

Engraving of Thomas Carlyle by Thomas Johnson, from an 1874 photograph (Century Magazine). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Engraving of Thomas Carlyle by Thomas Johnson, from an 1874 photograph (Century Magazine). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.In the political history of Europe, the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 constitutes the apex of this quest to a coherent, unified, and meaningful modern world: leagues of experts compiling data on ethnographic settlement patterns, geographical features, and social structures in order to create a coherent set of borders and nation-states. Their gospel was the principle of national self-determination, according to which every ‘nation’ was entitled to choose its own form of government and statehood. The idea was to re-order Europe in a coherent way, but complexity struck back. Self-determination had to adapt not simply to the diverse local contexts, but also to the varying political coalitions and geostrategic interests of the great powers. Most often, it was reduced to statistics of language and religion. Having started with high hopes for bringing order and coherence to modern Europe, many diplomats, statesmen, and experts considered the result utterly disappointing. As this disappointment took hold in the coming years, it would soon provoke new quests for re-ordering — in the less sophisticated and significantly more violent fashion of the 1930s and 1940s.

Almost a century after the Paris Peace Conference, modern society has still not given up on the quest for the great synthesis of modernity. ‘Big Data’ represents the new spiritual principle of our time, merging science with the belief in algorithms and aggregates. We expect nothing less from the accumulation of huge masses of information than answers to how we should understand and order modern society, and what the meaning of all of this is.

Most recently, British writer Tom McCarthy has transposed the quest for meaning and order to a twenty-first century setting. In his novel Satin Island, the narrator, called ‘U’ — perhaps an allusion to James Joyce’s Ulysses or Robert Musil’s Man Without Qualities Ulrich — is an ethnographer employed by a global corporate group to write the ‘Great Report.’ That report is supposed to lay bare, systematize, and explain all the intricate and hidden ways on which our modern age is based. Tellingly, the highly self-aware, post-modern narrator dreams and fantasizes about, but never actually starts writing or even outlining the ‘Great Report.’

As the examples of Big Data and Satin Island indicate, our own age is not simply post-ideological and pragmatic, with reason, democracy, and liberalism gradually taking over the globe. We may have become better in ignoring complexity and avoiding ideological commitment, but we have not yet succeeded in leaving behind the spiritual quest for order that plagued Nietzsche, Joyce, and the experts at the Paris Peace Conference. Recent phenomena like Donald Trump, nationalist backlashes in Europe, and the rise of global terrorism indicate that it is not only futile but dangerous to shy away from finding answers to what people still care about: social cohesion, collective identity, and ‘meaning.’ If we pass over the discrepancies of our own age in an act of misguided pragmatism, we risk the ghosts of the past, ideology and fanaticism, returning with a vengeance.

In a time plagued by multiple international crises, global warming, and mass migration, we should certainly not copy past attempts to ‘restore order.’ But past enthusiasm for principles and meaning should encourage us to re-consider the non-committal skepticism of our age.

Featured image credit: ‘Order, chaos’ by Brisbane Taylor, © Brisbane Taylor (artwork) and Helen Birch (photograph) via DrawDrawDraw. Used with permission.

The post The quest for order in modern society appeared first on OUPblog.

Shakespeare and performance: the 16th century to today [infographic]

In the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, Shakespeare’s plays were performed at professional playhouses such as the Globe and the Rose, as well as at the Inns of Court, the houses of noblemen, and at the Queen’s palace. In fact, the playing company The Queen’s Men was formed at the express command of Elizabeth I to provide entertainment for the Court and ended up dominating the English stage during the 1580s. As later playing companies, such as the Admiral’s Men and the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, rose to notoriety, the repertory system aided in appeasing the demand from audiences and provided players with the opportunity to perform in a diverse selection of plays. Other innovations, such as enhanced special effects and explorations into different styles of plays, ultimately enabled English theatre to evolve and expand into what we recognize it as today.

You can download the infographic as a PDF or JPG.

Image: “The Plays of William Shakespeare” by John Gilbert. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The post Shakespeare and performance: the 16th century to today [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

The strange case of the missing non-existent objects

Let me tell you—briefly—about strange case from the history of philosophy.

Alexius Meinong (1853-1920) was an Austrian psychologist and systematic philosopher working in Graz around the turn of the 20th century. Part of his work was to put forward a sophisticated analysis of the content of thought. A notable aspect of this was as follows. If you are thinking of the Taj Mahal, you are thinking of something, and that something exists. Similarly, if you are thinking of Father Christmas, you are thinking of something—but that something does not exist. (Sorry.) Similarly, you can fear something, worship something, admire something; and that something may or may not exist. A very commonsense view, you might think—and so it is.

It was a view shared by Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) in 1903; but in 1905 something interesting happened. Russell proposed a theory (known now as his theory of definite descriptions), according to which names like “Father Christmas” were shorthand for descriptions, such as “the old man who comes down the chimney at Christmas bringing presents”. And to say that Father Christmas does not exist, is not to attribute non-existence to an non-existent (obviously) object; it is just to say that nothing (or, to be precise, no unique thing) satisfies that description. Russell, then, came to reject Meinong’s view. It wasn’t so much that Russell’s theory did a good job of handling examples such as the above: when you apply Russell’s theory to claims such as “I am thinking of Father Christmas”, it patently gives the wrong result. Rather, said Russell, Meinong’s view offended against a “robust sense of reality”.

Alexius von Meinong. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Alexius von Meinong. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Russell’s influence on the 20th century logic and the philosophy of language was, of course, substantial, and his view about Meinong persuaded many. In 1948 the American logician Willard van Orman Quine (1908-2000) wrote a paper entitled “On What There Is”, in which he caricatured Meinong as the fictional character McX—not that there is any evidence to suggest that Quine had actually read Meinong. But the paper sealed Meinong’s fate. As Gilbert Ryle (1900-1976) put it in 1973, Meinong’s theory is “dead and buried, and not going to be resurrected”.

The victors, as the saying goes, get to write the history. Meinongianism became a term of abuse. He was a fruitcake, a momentary aberration in the history of Western philosophy, which was soon righted by Russell and Quine. The history, I note, is completely wrong: most of the great medieval logicians, like Jean Buridan and Paul of Venice, invoked non-existent objects in contexts of the kind in which Meinong was interested—not to mention Aristotle himself. Still, most contemporary logicians don’t know much about the history of logic. And for better or worse, the view about Meinong became unquestioned orthodoxy. It was certainly the view that I myself held when I was a young philosopher in the early 1970s.

Now to the strange thing. In the last 30 years, Meinong’s view has been making a comeback. Several philosophers have been involved in this, but the most important for me was the late Australasian philosopher, Richard Routley (or Sylvan, as he became). It was arguing with Richard for many years that persuaded me that the arguments against Meinong’s view were poor, and that it had a simplicity and common sense, in contrast to which other views limp. So I changed my mind, and became a Meinongian—or noneist, as Richard called it.

Why has this change taken place? A hard question. Undoubtedly many factors are involved. Certainly, one important one is that the arguments against noneism are, indeed, bad. Another is that Russell’s theory of descriptions, as applied to names, is now itself history, despatched by Saul Kripke’s onslaught in the 1970s.

Russell in 1938. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Russell in 1938. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.But there is, I think, more to the matter than this. Philosophers (myself included) like to pride themselves as rational—driven simply by the force of reason and argument. But fashion plays more of a role in the discipline than we might like to admit. Often, old philosophical views are not refuted; people simply get bored with them, and want to strike out in new directions. Conversely, a discarded view can make a comeback, because these new directions are more congenial to the view—and it cannot be denied that developments in modern logic have helped the Meinong-revival.

Then there is power and prestige. The English-speaking philosophers I have mentioned were all in centres of academic power: Cambridge, Harvard, Oxford. Their students themselves often came to hold positions of influence in English-speaking universities, and carried the doctrines of their mentors with them. But then there is generation-change. Just as young people want to assert their independence from their parents by rejecting their views, so a new generation of philosophers wants to stamp their authority on the subject, and you can’t do that simply by reproducing the past.

Anyway, whether the explanations I proffer are right or wrong, noneism is certainly making a comeback—and the advances in the techniques of formal logic are making it possible to articulate and investigate the view with a sophistication unavailable to Meinong himself. My own preference is to use the employ semantics using possible and impossible worlds.

It must be said, in fairness, however, that anti-noneism is still the orthodox view amongst English-speaking philosophers. But, in my view, what we are witnessing is something of a sea-change on the matter. And when it has taken place, it will not be Meinong’s views which appear to be a momentary aberration in the history of Western philosophy, but those of Russell and Quine.

Featured image: House by vargazs. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The strange case of the missing non-existent objects appeared first on OUPblog.

September 23, 2016

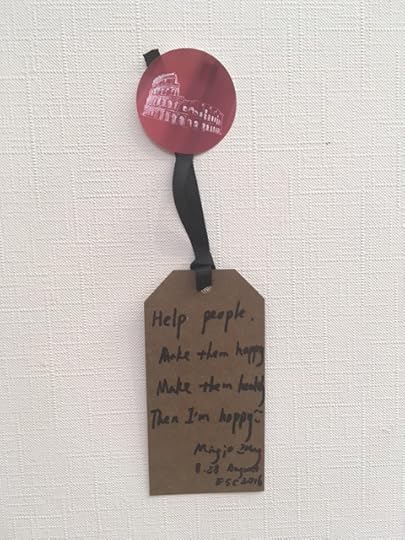

What inspires the people who save lives?

The ability to improve the health of another person or to save their life requires great skill, knowledge, and dedication. The impact that this work has goes above and beyond your average career, extending to the families and friends of patients. We were interested to discover what motivates the people who play a vital role in the health and quality of life of hundreds of people every year. At this year’s European Society of Cardiology Congress in sunny Rome, we welcomed over 30,000 cardiologists and displayed our portfolio of works across the field of cardiology. Even Pope Francis stopped by and paid the Congress a visit! So we took this opportunity to ask cardiologists from around the globe what inspires them in their work and handpicked a selection of our favourites below.

“Changing my patients’ lives be it with a treatment or a smile.”

“Help people. Make them happy. Make them healthy. Then I’m happy.”

“Patients’ smiles when they get out of hospital feeling better”

“What inspires my work? Seeing my patients doing well! That’s what pushes me to try and be my best self everyday…”

“The patients who smiles me back”

“Money”

Other responses included the “possibility to make life better” and “healthy beating in stethoscope”. What inspires your work in healthcare? Let us know with a comment!

Images by Ellie Gregory for Oxford University Press. Used with permission.

The post What inspires the people who save lives? appeared first on OUPblog.

Why peer review is so important

As part of Peer Review Week 2016, running from 19-25 September, we are celebrating the essential role that peer review plays in maintaining scientific quality. We asked some of our journal’s editorial teams to tell us why peer review is so important to them and their journals. Why do you think peer review is so important? Comment at the end of the article and share your thoughts.

Catherine Cotton

Around 90% of microbiologists see peer review as improving scientific knowledge and as a contribution to the scientific community.

Dr Catherine Cotton is the CEO Federation of European Microbiological Societies (FEMS) on whose behalf Oxford University Press publish five journals.

J Peter Donnelly

I regard it as a duty and privilege to be asked to be a peer reviewer of my fellow scientists’ work so consider it essential to clearly indicate any major concerns I may have then follow this with a list of minor points to help the author improve the paper so that the end result is a concise clear and credible piece of work which adds to the existing body of knowledge.

Dr J Peter Donnelly is the Editor-in-Chief of Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy and work for the Radboud University Medical Centre in Nijmegen.

James Galloway

As a researcher I have come to expect the sometimes harsh feedback that peer review entails. However, as an associate editor, my appreciation for scientific critique has evolved. To create a well-crafted commentary on a submitted manuscript is a true skill, and when done well, satisfying to read. Obtaining high quality peer review is core to research publication: journals rely upon the dedication of the academic community.

Dr James Galloway is a clinical lecturer at King’s College London, an honorary consultant in rheumatology at King’s College Hospital and an Associate Editor of Rheumatology .

Katsumi Isono

Peer reviews that are conducted by timely, reliable individuals are indispensable for an editor to judge whether a manuscript submitted is worthwhile to publish in a journal or not.

Dr Katsumi Isono is Prof.-emeritus of Kobe University and the Executive Editor of DNA Research .

Dimitri M. Kullmann

The role of academic journals as I see it is to bring the most important discoveries to the attention of other researchers and interested readers, and to frame these advances in an appropriate scientific, clinical, cultural or historical context. Inevitably, in order to select among competing claims for attention, we have to take into account the opinions of experts who may be closer to the actual topic of the submitted work. In my opinion, anonymous peer review is the worst way of evaluating the importance, novelty and veracity of manuscripts, apart from every other method that has been tried. The role of reviewers, however, is not to dictate but to advise, and with relatively rare exceptions, I think they do a good job. I will therefore continue to rely on this system for the journal that I edit.

Professor Dimitri M. Kullmann is a Consultant Neurologist at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, a Professor of Neurology at the UCL Institute of Neurology, and the Editor of Brain .

Richard Watts

Peer review underpins the academic publication process, but has been much criticised. It is one of the main methods by which journals try to maintain quality control over the material that is published… Journals such as Oxford Medical Case Reports (OMCR) are dependent on our peer reviewers and are grateful to them of the time that they give up.

Dr Richard Watts is the Editor-in-Chief Oxford Medical Case Reports , as well as a Consultant Rheumatologist at Ipswich Hospital NHS Trust and Senior Lecturer at the University of East Anglia.

Allison Worden

Peer review is one of the most critical means by which journal editors safeguard the integrity of the scientific literature. Calling attention to details as seemingly minor as misplaced punctuation to those as grave as plagiarism and data fabrication, careful peer reviewers improve manuscripts in countless ways. The editors of Nutrition Reviews encourage all reviewers to approach the task of reviewing with as much care as they would hope a reviewer of their own work would provide. Feedback that is substantive, constructive, polite, and well considered is essential for the process to work effectively and is deeply appreciated.

Allison Worden is the Managing Editor of Nutrition Reviews .

Featured image credit: Correcting Papers, by Quinntheislander. CCO Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Why peer review is so important appeared first on OUPblog.

Nebuchadnezzar to Saddam Hussein: The history of the myth of Babylon

‘Babylon’ is a name which throughout the centuries has evoked an image of power, wealth, and splendour – and decadence. Indeed, in the biblical Book of Revelation, Rome is damned as the ‘Whore of Babylon’ – and thus identified with a city whose image of lust and debauchery persisted and flourished long after the city itself had crumbled into dust. Powerful visual images in later ages, like Bruegel’s Tower of Babel and Rembrandt’s Belshazzar’s Feast perpetuate the negative image Babylon acquired in biblical tradition. The latter found musical expression in William Walton’s composition Belshazzar’s Feast, and the reign of Babylon’s most famous – and infamous – king Nebuchadnezzar in Verdi’s opera Nabucco, best known for its ‘Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves.’ In recent years, the representation of Nebuchadnezzar as a ruthless, despotic tyrant was given a fresh airing in the political propaganda of Saddam Hussein who claimed to be the ancient king reincarnated – and sometimes had himself depicted on posters riding a chariot and decked out in Nebuchadnezzar’s military gear.

Babylon lies near the political centre of gravity of modern Iraq, close to its capital, Baghdad. It was the royal seat of the southern part of Iraq (also known as Mesopotamia or southern Mesopotamia), stretching southwards to the Persian Gulf. When referring to its ancient history and civilization, scholars often call this region Babylonia. Its natural environment is harsh. Large desert tracts of land occupied much of its flat arid plain, barely moistened by the region’s meager rainfall which frequently failed altogether. Drought was an ever-present threat to human survival, and natural resources, including metals and timber, were extremely scarce. Yet human determination and ingenuity, which found expression in the construction of a complex system of irrigation canals and the undertaking of wide-ranging trade and military expeditions, enabled the peoples of the region to survive and flourish. Already during the 3rd millennium, several major civilizations, like the Sumerian and Akkadian civilizations, had arisen in southern Mesopotamia. Babylon’s rise to prominence came in the early 2nd millennium, in the reign of Hammurabi, its first great ruler. Hammurabi built the first of three great Babylonian kingdoms, all of them major powers within the Near Eastern world. Though a highly successful war-leader, Hammurabi is best remembered as a great builder, social reformer, and guardian of justice. Many cities in his kingdom, and especially their religious sanctuaries, were restored and redeveloped under his rule, and many of his successors maintained his building and restoration programmes, and his responsibilities for ensuring justice throughout the land over which they held sway.

‘Belshazzar’s Feast’ by Rembrandt, purchased by the National Gallery with support of The Art Fund. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

‘Belshazzar’s Feast’ by Rembrandt, purchased by the National Gallery with support of The Art Fund. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.This brings us back to Nebuchadnezzar. Babylon was some 2,000 years old when in 605 BC Nebuchadnezzar succeeded his father on its throne as the second ruler of the short-lived Neo-Babylonian empire, which ended with the Persian conquest of it in 539 BC. Was the Babylon of that period the city of wantonness and depravity, and was its king Nebuchadnezzar the monster of cruelty and oppression, as depicted in our biblical sources and later artistic tradition? This image of the city and its most famous ruler has now been largely countered by the recovery of Babylon’s own history and civilization, through the decipherment of the language of its tablets, and the sifting of its archaeological remains. Both sets of sources reveal to us a city that became the centre of one of the most culturally and intellectually vibrant civilizations of the ancient world, exercising a profound influence on its Near Eastern contemporaries, and contributing in many respects to the religious, scientific, and literary traditions of the Classical civilizations of Greece and Rome. In keeping with a legacy that goes back at least as far as Hammurabi, Nebuchadnezzar devoted himself to building and restoration projects throughout his land, and proclaimed his responsibilities in ensuring justice and protection for all his subjects, especially those who were most vulnerable – as Hammurabi had done in his famous (and still extant) set of laws. Under Nebuchadnezzar, Babylon became the largest and most sophisticated city of the ancient world. The so-called ‘Tower of Babel’ was one of its defining landmarks. It was a multi-platformed building, of a kind found in many Babylonian cities as well as Babylon itself, and was known as a ziggurat. Though it was certainly a religious building, its precise function remains unknown. (One suggestion is that it served as a substitute for the mountains in which the gods originally lived.)

Babylonian contributions to the arts and social and physical sciences remain among the most important achievements of all ancient civilizations, as the decipherment of the ancient Near Eastern languages and the excavation of the Babylonian cities have so amply demonstrated. Yet the image of Babylon itself as the archetypal city of decadence, profligacy, and unrestrained vice is the one that remains paramount in modern perceptions. Thanks to the influence of the Judaeo-Christian view of this city, strongly reinforced by the lurid depictions of it and its rulers in western art, this image continues to dominate all others, despite all that modern Mesopotamian scholars have done to provide a more balanced view of this the centre of one of the world’s greatest civilizations.

Featured image credit: The Tower of Babel by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Nebuchadnezzar to Saddam Hussein: The history of the myth of Babylon appeared first on OUPblog.

September 22, 2016

Where is Mexico going? The obstacles in its rocky road to democracy

In a recently released poll this month, 22% of Mexicans approved of President Enrique Peña Nieto’s performance in office. Data released in the same survey revealed that 55 %, more than twice the percentage of those who viewed the president in a positive light, strongly disapproved of his performance. No president since Vicente Fox, who was elected in 2000 and moved Mexico significantly along the path to electoral democracy, has ever received such weak support. When ordinary citizens were asked to identify those policy areas where Peña Nieto’s administration was perceived as performing least effectively, they identified the following: a mere seven percent viewed the government’s approach to drug trafficking in positive terms; between 10% to 12% of Mexicans ranked the administration’s efforts in reducing crime, hunger, and poverty as successful; and only 13% to 14% viewed its foreign policy, environmental, and anti-corruption efforts as successful.

Mexico achieved a major change in its political structure at the end of the 20th century, shifting from a semi-authoritarian model dominated by a single political organization, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), to a competitive, functional three party system in the 2000 presidential election, when, for the first time since the 1920s, an opposition candidate from the National Action Party (PAN) won the election. The next two elections reinforced the growth and legitimacy of electoral competition, when in 2006 a second PAN candidate, Felipe Calderón, defeated the candidate of the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), Andrés Manuel López Obrador, with PRI’s candidate finishing third in the race. To the surprise of many observers, PRI made a significant comeback in the 2012 race to defeat López Obrador, while the PAN candidate finished a distant third.

No president in the past three elections has won a majority of the votes. Unbeknownst to the public, the presidents of these three leading parties, along with the current president of Mexico, negotiated and signed an innovative policy agreement known as the Pact for Mexico, which identified all of the major policy issues and the legislative changes necessary to address them. Each of the party leaders acknowledged that none had a clear governing mandate. The Pact was an extraordinary attempt to decrease partisanship in the legislative branch, and to create an imaginative yet practical collaboration among the three major political organizations. It allowed all parties simultaneously to take credit for the policies passed by the Chamber of Deputies and implemented by the federal government.

“Marcha #RenunciaYa” by ProtoplasmaKid. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

“Marcha #RenunciaYa” by ProtoplasmaKid. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.Given this extraordinary achievement, many observers believed early on that Peña Nieto might be able to create the necessary changes to push Mexico further on its path toward a consolidated democracy: that is, a democratic political model that, among other characteristics—including competitive elections and turnover among the incumbent political parties—would strengthen transparency, accountability, and the rule of law. Although this agreement lasted only 14 months, the administration was able to introduce and actually implement a number of significant policies. Some of those policies are linked to the three qualities that are necessary for a functional democratic system. For example, the government has made a number of alterations to the legal system, the most important of which was to shift a trial system based on a Napoleonic legal approach, relying heavily on confessions supplied by the prosecution, to a system more comparable to that found in the United States, where oral testimony and forensic evidenced are essential to a fair trial.

Despite these on-going changes, crime and corruption—both real and perceived—remain serious issues in Mexico. The federal government’s own data from the National Public Security System reveals that homicides, many of them drug related,

increased significantly in 17 states since Peña Nieto was inaugurated in December 2012.

Among the multitude of victims, two professions stand out: journalists and mayors. In 2016 alone, between January 1 and July 20, more journalists were murdered in Mexico than in any other country in the world. Most of these murders remain unsolved. Journalists themselves identify the impunity that is characteristic of these crimes as a “failure of the rule of law.” In the state of Tamaulipas alone, since 2010, fifteen journalists have been killed. Since 2006, 79 sitting or former mayors also have been murdered. Regardless of the crime, fewer than 2% of criminals are arrested and prosecuted nationally.

Another significant achievement of the Peña Nieto administration has been the passage and implementation of numerous reforms related to the public education system, long controlled by a corrupt national teachers union, whose leader was arrested after the passage of these reforms. In essence, they address issues of transparency, accountability, and following the law, removing control of hiring, firing, evaluation, and other criteria from the hands of local and national union officials. Two-thirds of Mexicans believe that classroom practices need to be changed.

Ordinary citizens, and Mexican leaders from all professions, are in agreement that two of the most important issues facing Mexico today are crime and corruption. The extraordinary decline in support for the present administration is clearly linked to their perceptions of the presence of these two issues in Mexico. The apparent inability of public institutions at all levels to generate confidence in their integrity and effectiveness, especially as it relates to human rights, has impacted dramatically on the lack of confidence in those institutions, on trust in each other, and on Mexican perceptions of the efficacy of democratic institutions to solve their problems.

Featured image credit: “Obama, Peña y Harper. IX Cumbre de Líderes de América del Norte” by PresidenciaMX 2012-2018. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Where is Mexico going? The obstacles in its rocky road to democracy appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers