Oxford University Press's Blog, page 463

September 20, 2016

Hourly rates becoming more and more mainstream in German arbitration

What has long been standard market practice in many jurisdictions is becoming more and more mainstream in Germany too: compensating counsel in arbitration cases on an hourly basis, and being entitled to have the defeated party pay for it.

There is a traditional view in Germany that at least as far as domestic arbitration goes, cost awards dealing with attorneys’ fees should be limited to the statutory fee scales applicable in state court litigation. Over the last few years, more and more tribunals, courts and legal scholars have adopted a more flexible approach, which has now been endorsed in a recent decision by the Munich Court of Appeals (Oberlandesgericht München, 4 July 2016, file no. 34 Sch 29/15).

In this case, the court had to deal with an application to set aside an arbitral award in which the arbitral tribunal had done just that. The winner had spent several hundred thousand Euros for its lawyers to conduct the case, and asked the tribunal to make the defeated opponent pay for it on the basis of the German arbitration law. The unhappy loser in the arbitration also lost the set aside application. The Munich Court of Appeals was clear that German arbitration law gave the arbitral tribunal discretion on this issue and that the nature of the case clearly allowed the hiring of specialized counsel. Among other things, the case raised complex issues of antitrust laws in connection with long-term energy supply contracts. In these circumstances, both the arbitral tribunal and the Munich court found it reasonable to hire a lawyer who would accept the assignment only against an hourly fee arrangement and not on the basis of the – much lower – statutory fee scales for attorneys-at-law under German law.

More often than not, increased costs in arbitration are the result of unnecessary or even obstructive manoeuvres

The court decision does not spell out the rate itself. Based on figures contained in the reasoning of the decision dealing with the amount of hours worked and the overall amount requested by the winner, it appears that the hourly rate was somewhere between EUR 300 and 400.

The decision is a welcome reminder of a number of themes:

First, arbitration in Germany – be it domestic or international – is separate from domestic state court litigation. Even though practitioners less familiar with the arbitral process tend to transfer concepts known from state court litigation to the conduct of an arbitration matter, this approach is often flawed both as a matter of law and practice. German law conceives arbitration as a dispute-resolution mechanism separate and apart from state court litigation. As can be seen from the legislative materials, arbitration is meant to render legal protection to the parties which is “in principle equivalent” to state court litigation (grundsätzlich gleichwertig), but the rules are far from identical.

Second, rules in arbitration are generally more flexible than the more rigid rules governing German state court litigation. Specifically, whereas German state courts see themselves principally bound to the attorney fee scales provided for by German law, an arbitral tribunal has more discretion as to what expenses it considers reasonable for pursuing a case. The Munich decision is a welcome encouragement to arbitral tribunals to make use of their discretion.

Third, more remains to be seen on the details. The court did not go into the issue of when hourly rates might be too high to be reasonable. The case did not necessitate such a discussion. As a general matter, arbitral tribunals and courts should be reluctant to second-guess a party’s agreement with its lawyers on hourly rates, or attorney compensation more generally. After all, high rates do not necessarily equal excessive overall costs, just as lower rates are not a guarantee for a more reasonable outcome. Much depends on the skill-set of the lawyers employed, their experience, the efficiency of their work-style, and last but not least, the parties’ approaches to the conduct of the case. More often than not, increased costs in arbitration are the result of unnecessary or even obstructive manoeuvres, such as doubtful procedural moves or excessive document production, and not so much the result of the amount of hourly rates.

Featured image credit: Untitled, by Wil Stewart. CC0 Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post Hourly rates becoming more and more mainstream in German arbitration appeared first on OUPblog.

September 19, 2016

11 facts you may not have known about Roman gladiators

About two thousand years ago, fifty thousand people filled the Colosseum in Rome to participate in one of the most fascinating and violent events to ever take place in the ancient world. Gladiator fights were the phenomenon of their day – a celebration of courage, endurance, bravery, and violence against a backdrop of fame, fortune, and social scrutiny. Today, over 6 million people flock every year to admire the Colosseum, but what took place within those ancient walls has long been a matter of both scholarly debate and general interest.

The murderous fights were a form of popular entertainment for the masses, both poor and rich alike. The ancient Romans had a morbid fascination with the gladiator, and still to this day, the gladiator remains an intriguing subject in academia and popular culture. To help separate popular myth from reality, we’ve assembled some of the most interesting facts about one of the most iconic figures of the Roman empire, drawn from Garrett G. Fagan’s Oxford Classical Dictionary article “gladiators, combatants at games.” Read ahead to see how much you know about Roman gladiators!

1. According to modern scholarly interpretations, the gladiatorial games were perhaps vehicles of social control and functioned to distract the populus from recognizing their diminished autonomy under imperial rule. Gladiatorial games were a phenomenon in the Roman world, and both ancient and modern scholars have held different interpretations of the games and their place in Roman history. Some would argue that the games reflect typical Roman virtues, such as courage, endurance, and martial skill, while others, like Roman satirist Juvenal, thought that the games preyed on the Roman’s unhealthy obsessions with “bread and circuses” (Sat. 10.78–81). Modern interpretations consider the games distractions that kept the people subdued and unable to realize the real loss of power under the empire.

“Bestiarii,” before 80 AD. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Bestiarii,” before 80 AD. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.2. The educated elite opposed the gladiatorial events and saw them as mass entertainment for the lower classes. Their opposition, however, was never motivated by altruism. In fact, they were far less concerned about the lives of those participating in gladiatorial combat, who they viewed as worthless and deserving of their fate. Their opposition stemmed from what they saw as moral indolence and the indignities of indulgence.

3. Jews and Christians were likewise seemingly unconcerned about the victims of arena violence. Their arguments in opposition to the games focused on what they viewed as inherent idolatry, as gladiatorial show often occurred during pagan religious festivals, which featured idols and images of pagan gods.

4. Gladiators were regarded as infames (people of bad reputation). Most gladiators were slaves, ex-slaves, or freeborn individuals who fought under contract to a manager. They were often ranked below prostitutes, actors, and pimps, and generally regarded as both moral and social outcasts.

5. Despite this, gladiators were the sex symbols of their day. Gladiators enjoyed quite a bit of popularity, especially from women – so much so that a name was coined for these ancient fan-girls (ludiae, or “training-school girls,” a term coined by Juvenal (Sat. 6.104)).

6. Some gladiators were honored with monuments. Not all gladiators were simply killed and cast off. The more popular gladiators had gravestones and inscriptions that revealed their origins, careers, and views of their profession. Gravestones were quite expensive, and even more so if they were engraved. While the question remains if the sentiments left behind were their own, these epitaphs were often the only window into the personality of these warriors.

7. Not all gladiators were men. It is not clear if women ever fought in the arena, but there is evidence that suggests female gladiators did exist. Roman emperor Domitian was said to stage fights between female gladiators and dwarves. Another notice suggests the ancient city of Halicarnassus hosted a fight between two female warriors named “Amazon” and “Achillia”. But while these fights may have very well taken place, they were likely spectacles put on for the emperor and were probably just a novelty.

8. Gladiatorial bouts were originally part of funeral ceremonies. Gladiatorial exhibitions were originally associated with funerary commemoration. As the games’ popularity grew, so did their scale and finesse. One notable exhibition took place in 216 BCE, when 22 fights were held over three days to mark the death of a prominent senator.

9. Gladiators were (mostly) recruited and trained, much like athletes are today. Gladiators were lived and trained in schools (ludi gladiatorum) under the watchful eye of their managers (lanistae). Willing gladiators worked under contract, while unwilling gladiators (usually slaves) were either bought by a ludus gladiatorum or condemned by the Roman courts to fight in the arena.

10. Death was an acceptable outcome, but not an inevitable result, of gladiatorial

shows. Most depictions of gladiatorial combat often portray fights as a bloody free-for-all that usually ends with one participant brutally maiming the other, but that was not always the case. Since gladiators were skilled professionals, it would be a devastating economic blow to managers if they lost a member of their gladiatorial stock.

11. The gladiatorial games were officially banned by Constantine in 325 CE. Constantine, considered the first “Christian” emperor, banned the games on the vague grounds that they had no place “in a time of civil and domestic peace” (Cod. Theod. 15.12.1). However, there is no evidence to suggest that the ban was implemented for humanitarian reasons. In fact, the would-be gladiators were sent instead to the mines to ensure a steady stream of labor. Further evidence suggests that the games had simply become too expensive and that the recent “Christianizing” of the empire had resulted in fewer combatants.

Featured image credit: “Colloseum” by Björn Fritz. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post 11 facts you may not have known about Roman gladiators appeared first on OUPblog.

How well do you know Aristotle? [quiz]

This September, the OUP Philosophy team honors Aristotle as their Philosopher of the Month. Among the world’s most widely studied thinkers, Aristotle established systematic logic and helped to progress scientific investigation in fields as diverse as biology and political theory. His thought became dominant during the medieval period in both the Islamic and the Christian worlds, and has continued to play an important role in fields such as philosophical psychology, aesthetics, and rhetoric.

How much do you know about Aristotle? Test your knowledge with our quiz below!

Featured image: Parthenon from the west. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Quiz image: Bust of Aristotle. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How well do you know Aristotle? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

The UN Summit for refugees and migrants: A global response includes empowering one refugee at a time

This year marks the 65th anniversary of the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, which was adopted by the United Nations in the aftermath of the Holocaust. The Convention was built upon the Universal Declaration of Human Rights — itself a direct repudiation of the atrocities of the Holocaust — particularly Article 14, which recognizes the right to asylum in other countries from persecution. Initially, the Convention was limited to protecting those European refugees, and it was anticipated that the refugee problem would abate with time. Yet today, the world faces the largest refugee crisis since World War II, with 65 million persons forcibly displaced, including 21 million refugees.

Refugees have become so pervasive in human consciousness that the Oxford Dictionaries for Children identified “refugee” as the 2016 Oxford Children’s Word of the Year, based on findings from the 500 Words global children’s writing competition sponsored by BBC Radio 2. According to the BBC, “refugee” was selected “due to a significant increase in usage by entrants writing in this year’s competition combined with the sophisticated context that children were using it in and the rise in emotive and descriptive language around it.”

It is in this setting of massive global displacement that the UN General Assembly has decided to hold a high-level Summit for Refugees and Migrants on 19 September, with the aim of coordinating the world’s humanitarian response to these victimized and vulnerable populations. Ahead of the Summit, the UN Member States have developed a Draft Political Declaration for adoption at the Summit. Included in the broad scope of this statement are commitments to treat all refugees and migrants in a “people-centred, sensitive, humane, [and] dignified manner;” to “take measures to enable refugees … to make the best use of their skills and capacities, recognising that empowered refugees are better able to contribute to their own and their communities’ well-being;” and to “commit to share best practices [and] provide refugees with sufficient information to make informed decisions.”

During the past two years, colleagues and I have been undertaking research and training that addresses these very objectives. Project MIRACLE (Motivational Interviewing for Refugee Adaptation, Coping, and Life Empowerment) is an innovative approach to casework with refugees. Motivational Interviewing (MI) is an evidence-based, person-centered counseling style that aims to help clients explore and resolve ambivalence about behavior change. This is particularly relevant for refugees because they must adapt to their new lives in many ways – from language, to customs, to foods, to learning new work skills, new transportation systems, sometimes even things such as learning to operate a stove. However, although refugees may see the necessity for adaptation, they are sometimes reluctant to change, given that they have not freely chosen to do so, but have been forced into making a move that requires such change. This adaptation process creates what is known as acculturative stress.

Today, the world faces the largest refugee crisis since World War II, with 65 million persons forcibly displaced, including 21 million refugees.

MI entails client collaboration, evocation, and autonomy. The method was originally developed in the field of substance abuse treatment; however, it has since been expanded to numerous areas of health, mental health, and social work. Although refugee service providers have used MI on an ad-hoc basis, Project MIRACLE is the first time that MI has been applied in a conceptual and systematic manner specifically to this population.

A cornerstone of MI is empathy. To this end, the first phase of Project MIRACLE was the development and validation of the Helpful Responses to Refugees Questionnaire (HRRQ), which measures refugee caseworkers’ empathetic responses to hypothetical refugee statements. Subsequently, 34 US caseworkers were trained in MI in a three-hour webinar format using a randomized controlled trial; outcome was measured using the HRRQ. Training group participants’ responses significantly improved from before to after training compared to the control group which received no training; these results were replicated in the control group after those participants received training. These initial studies were supported by the Lois and Samuel Silberman Grant Fund in The New York Community Trust and conducted with colleague Kristen L. Guskovict. Manuscripts are currently under submission to peer-reviewed journals.

In a case of serendipitous synergy, recently I was contacted by the Client Support Services Program (CSS), which provides intensive case management to Government-Assisted Refugees throughout six cities in Ontario, and is coordinated by of the YMCA of Greater Toronto. The CSS program has been actively involved in implementing client empowerment approaches since the program’s inception several years ago, and had likewise identified MI as having significant potential for application with refugees. We are now collaborating to provide a live MI training to CSS staff, and to solicit staff feedback in a debriefing session. This will add to our knowledge base about the utility of MI not only for caseworkers and the refugee clients they work with, but across countries that have differing resettlement policies and programs as well as sociopolitical contexts. Further, the CSS program has developed a comprehensive client outcome assessment system that may allow for a pilot impact evaluation of the training on client outcomes.

Project MIRACLE is also expanding beyond resettlement countries to host countries. Currently Kristen is in Greece with the Danish Refugee Council, training protection workers in refugee camps on basic underpinnings of MI such as empathy and active listening, within the context of a larger training on refugee trauma. These protection workers are also completing the HRRQ, which will allow us to assess its relevance to camp settings.

MI clearly is not a panacea for all the tremendous challenges facing the UN Summit. However, it is a potentially powerful tool for advancing the person-centered empowerment aims formulated in the draft declaration. And MI’s focus on empathy certainly promotes the commitment to treat refugees with sensitivity, humanity, and dignity. In the words of Henry David Thoreau, “Could a greater miracle take place than for us to look through each other’s eyes for an instant?”

Featured image credit: united nations world flag by Etereuti. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The UN Summit for refugees and migrants: A global response includes empowering one refugee at a time appeared first on OUPblog.

Beyond the binary: Brexit, environmental law, and an interconnected world

What are the narratives we can tell about the future of UK environmental law in light of the result of the EU referendum? Any answer is not just important for the UK, but will also directly shape our understanding of what nationhood means in an era of globalisation. That sounds a rather grandiose statement to make, but let us explain.

One narrative about UK environmental law’s future is appealing in its simplicity. The EU, with its Treaty commitment to ‘a high level of environmental protection’, has been a major source of environmental law in the UK. Clean water, clean beaches, waste regulation, and habitat protection are just a few things that EU directives have set as legislative goals. Leaving the EU can thus be seen as an abandonment of these goals. This is particularly when a number of Leave advocates were promoting a deregulatory agenda of reducing red tape. Linked to this notion of deregulation is the oft-repeated demand from the Leave campaign to return power to the UK. Vote Leave was promoted as a vote for sovereignty and ‘taking back control’ – voting remain was understood as the opposite of those things.

Yet, this binary narrative ignores the fact that EU environmental law is a product of the interplay between different Member States’ legal cultures and the forces of harmonisation. The EU has evolved into one of the most sophisticated multi-level governance systems of the contemporary age and EU environmental law reflects this fact. Its main legal forms are directives that are required to be in integrated into national legal orders and are primarily enforced in national courts. Its operation involves a multitude of legal actors at all levels of government and the end result is a dynamic set of legal regimes with novel processes, remedies, rights and duties, which cut across public and private orders and are not just EU in nature. For example, environmental impact assessment has given rise to a rich body of UK case law concerning its legal nature. The EU air quality regime has similarly required UK courts to reflect on their remedial powers.

This narrative also ignores that the EU is just one emanation of the European order. The Council of Europe and the UN Economic Commission for Europe also generate norms that become binding on the UK, including in the environmental sphere. It follows that a ‘sovereign’ UK will continue to be embedded in a broader governance framework, which may constrain its choices in a post-EU world.

The global lessons of the last thirty years have been that environmental law is inherently multi-level, polycentric and requires interstate co-ordination.

None of this is surprising. The global lessons of the last thirty years have been that environmental law is inherently multi-level, polycentric and requires interstate co-ordination. Legal cultures are unique but environmental problems are universal. Moreover, addressing environmental problems requires all levels of government, as well as co-operation between the public and private at different levels in nuanced ways. Nor is this simply a tension between the state and the supranational. As the aftermath of the Brexit referendum clearly shows, differences within countries must also be reconciled in the governance process.

Practice and scholarship has evolved, often in quite sophisticated ways, to address this state of affairs. Scholars talk of ‘uploading’ and ‘downloading’ regulatory regimes, ‘regulatory transplants’, ‘regulatory capitalism’ and ‘regulatory competition’. Moreover, concepts of ‘transnational environmental law’, ‘global environmental law’ and ‘a human rights approach to environmental protection’ also try to capture the complexities of regulation in this sphere. Behind all this jargon exists a simple reality – nation states are interconnected by markets, by politics, and by geography.

None of that is easy to express however, particularly in the context of a referendum that by its nature required citizens to make a choice between ‘Leave’ or ‘Remain’. But in the post-referendum era, the problems of this duality and the need to understand the ways in which polities are interconnected become even more pressing. While no one doubts the importance of ideas of sovereignty, its rhetoric should not be seen as an answer to the challenges of the post-Brexit world. We find ourselves in uncharted political, intellectual and legal territory. The challenge for practitioners and scholars moving forward is how to evolve an inherently multi-level subject in light of these circumstances in a robust and legitimate way. While Brexit is a distinct UK phenomenon, the issues it raises for environmental law are not. How much room is there in environmental law for sovereignty and control? How will existing structures of cooperation be reshaped in light of this paradigm shift? Does theory need to adapt in order to accommodate changes to the political and legal realities? In short, how do we reimagine environmental law in light of shifting political discourses?

What can be seen from above is that narratives matter because they shape how we see the world and the questions we ask about it. Seeing the future of UK environmental law as a binary choice ignores the rich complexity of this area of law and thus discourages the asking of constructive questions. Seeing it in more multi-level terms does not dismiss ideas of national self-definition, and has far greater potential to foster a more sophisticated and constructive narrative about the future of environmental law. Not just for the UK but for other legal cultures as well.

Featured image credit: Brexit referendum. CC0 Public Domain via Public Domain Pictures.

The post Beyond the binary: Brexit, environmental law, and an interconnected world appeared first on OUPblog.

September 18, 2016

The Catholic Church and the visions of Fátima

Outbursts of popular interest in apparitions and miracles often lead to new devotional movements which can be uncomfortable for the Roman Catholic Church hierarchy, contrary to the belief that they encourage them. Visionaries represent alternative sources of authority within the Catholic community; they claim to have encountered supernatural figures and understood divine imperatives in a way that is commonly thought to transcend the theological expertise of the Church magisterium. They present a prophetic challenge to the Church at all levels and call for renewed teachings and practices. For this reason, the Church has adopted at least three pastoral approaches depending on the nature and content of the visions and their following: (a) accepting the phenomenon and channeling it within the bounds of official oversight; (b) reaching a compromise with the movement, for example, accepting pilgrimage and new devotions at a particular sacred site but not the visionary messages themselves; (c) rejection and suppression where the popular movement has not reached a critical mass.

Fátima in Portugal is the most famous twentieth century Catholic apparition site and a prime example of approach (a). Fátima’s visionary, Sister Lúcia (as she was popularly known), was the only one of the three child seers of 1917 to survive the post-First World War influenza epidemic, and she lived until 2005. In 1917, various messages of the Virgin Mary were revealed by the children and became the accepted narrative. However, during the 1930s and 1940s, encouraged by the local bishop after Fátima had been formally approved by the Church, Lúcia – who spent her adult life in the cloister – began to expand on the original messages in a way that captured the attention of the Catholic public. The so-called ‘third secret of Fátima,’ that part of her revelations that the Vatican held back for forty years, provoked intense speculation as to whether it heralded some catastrophic disaster for Church and world.

Our Lady of Fatima. Image on an outside wall, next to the church of Fontecada, Santa Comba, Galicia (Spain). Photo by Luis Miguel Bugallo Sánchez. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Our Lady of Fatima. Image on an outside wall, next to the church of Fontecada, Santa Comba, Galicia (Spain). Photo by Luis Miguel Bugallo Sánchez. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia CommonsThe text was finally unveiled in the year 2000 by Pope John Paul II, and can be found on the Vatican website under the title The Message of Fatima. The ‘third secret’ was a prophetic vision that Lúcia claimed had been experienced by the children in 1917: a bishop in white ascended a mountain with other bishops, priests, members of religious orders, and various lay people; when he reached the Cross at the summit, he was executed along with the other Catholics by soldiers and angels gathered up the martyrs’ blood. Lúcia added in the text that the child visionaries “had the impression that (the bishop in white) was the Holy Father,” i.e. the pope. So John Paul II interpreted the prophecy as referring to the attempt on his life on 13 May 1981, the 64th anniversary of the first apparition at Fátima. Clearly, he accepted that the vision was symbolically rather than literally fulfilled, as he was in St Peter’s Square and not on a mountain when shot, and he was not killed (which he attributed to the intervention of the Virgin Mary). The other Catholics killed in the vision he saw as representing martyrs on a global scale, particularly victims of ‘atheistic systems’ in the twentieth century.

Several writers, including Catholic priests and journalists, have articulated a conspiracy theory about the publication of the text; indeed they have debated whether this is truly the ‘third secret’ either in full or at all. This is a complex issue and cannot be examined in detail here. Nevertheless, to generalise: what these commentators question is the way in which the Vatican has – apparently with the blessing of the elderly Lúcia – domesticated a potentially controversial piece of popular prophecy by first suppressing it for many years and then interpreting it in a way that sees the crisis as belonging to the past and therefore presenting no great challenge to the hierarchy.

However, the conspiracy theory misses something more ironic about the prophecy. The messages of Fátima revealed in the 1930s and 1940s gave great impetus to Catholic anti-communism. In some countries, notably in Catholic Spain and Portugal and their former colonies in Latin America, this anti-communist crusade was a key ideological tool in the policies of authoritarian dictators. In Latin America, many Catholics – priests, members of religious orders, and laypeople – joined the liberation theology movement protesting against these regimes, were branded as communist sympathisers, and a good number were killed. At their head was the iconic archbishop Romero of San Salvador. He was shot by agents of the government on 24 March 1980 and killed while celebrating Mass. He would make a better match for the prophetic vision than John Paul II.

This way of looking at the prophecy is pure speculation; it cannot be substantiated any more than any other. But yet it is a plausible explanation (if one is to interpret prophecy at all). In the Vatican, the prophecy was interpreted in a way that represented John Paul II, now a canonised saint, as a martyr witnessing against communism; there was no reference to Archbishop Romero, a martyr of right-wing oppression and largely overlooked by the Vatican until the present papacy which has beatified him. This shows how important it is for the Church to channel the most popular visionary phenomena in ways that accord with the official hagiography. In the Roman Catholic Church, since the ultramontane movement of the nineteenth century, the pope has been idolised and regarded as the last bastion of infallibility in a Catholic Church which understands too well that priesthood is no guarantee of sanctity. Thus John Paul II became the hero of Lúcia’s vision and the Polish pope, the icon of a Catholic community resisting communism, took his place in the history of an apparition movement that was at the centre of the campaign against communism.

Featured image credit: The Immaculata with six saints by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The Catholic Church and the visions of Fátima appeared first on OUPblog.

Scaling the UN Refugee Summit: A reading list

The United Nations Summit for Refugees and Migrants will be held on 19 September 2016 at the UNHQ in New York. The high-level meeting to address large movements of refugees and migrants is expected to endorse an Outcome Document that commits states to negotiating a ‘Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework’ and separately a ‘Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration,’ for adoption in 2018.

Albeit implicitly, the Outcome Document acknowledges that the international protection regime is faltering. On one hand it reaffirms the centrality of the legal and normative framework that underpins the regime. On the other, it acknowledges that not enough has been done to reduce the need for people to flee in the first place, that many fall into the hands of people smugglers, that responsibility for protecting and assisting refugees is not being shared fairly, that too many refugees spend too long in camps, that they often face discrimination in the countries where they arrive; and that overall the protection regime is chronically underfunded.

The document also lays the foundations for significant reform. It recognizes that the distinction between migrants and refugees may not be as clear today as it once was. It envisages better protection for refugees closer to their homes. It links the protection regime with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and it is explicit about the roles and responsibilities of the private sector and civil society, and acknowledges the need for more effective global governance on migration and refugees.

While the Outcome Document refers to periodic assessments to maintain momentum towards 2018, the risk will be that some states will retreat from some of the commitments made. What will be required quickly is realistic options based on credible research to help states scale the refugee summit.

This reading list is comprised of articles from Journal of Refugee Studies that may help inform changes to some of the most fundamental failings of the international protection regime.

Focus on the Forest, Not the Trees: A Changepoint Model of Forced Displacement by Justin Schon in Journal of Refugee Studies.

A criticism that is often levelled at the international protection regime is that it is reactive: it offers protection and assistance to people who have fled their countries, but does little to reduce the need to flee in the first place. Part of the reason why it has proved so difficult to address the root causes of displacement is that there is not enough research understanding the decision whether or not to flee. Justin Schon analyses data on daily violence levels in Somalia, to understand when and how violence results in displacement. Besides illustrating that the relationship between violence and displacement is by no means linear or causal, he also emphasizes the importance of understanding structural aspects of conflict, including its geographical scope. He concludes that we now have the data and methodology to zoom in on the details of conflict, to understand when it results in displacement, and to try to break this vicious cycle.

Refugee Health and Wellbeing: Differences between Urban and Camp-Based Environments in Sub-Saharan Africa by Thomas M. Crea, Rocío Calvo, and Maryanne Loughry in Journal of Refugee Studies.

Despite recent attention to Europe’s refugee crisis, about 85% of the world’s refugees live in poor and developing countries. Without underestimating the efforts of national governments or the international community, conditions for many of these refugees are deteriorating, especially in refugee camps, and as a result more are moving to urban areas. This article uses health as a lens on the wellbeing of refugees in Sub-Saharan Africa. On the one hand it demonstrates that refugees in urban environments report significantly higher satisfaction with health than refugees placed in camps. On the other it concludes that whether in cities or camps, the physical health of refugees is generally poor. The specific challenge for the international protection regime is to improve conditions in refugee camps, or promote new non-camp based solutions. The general challenge is a chronic lack of funding to facilitate such innovation.

Searching for Directions: Conceptual and Methodological Challenges in Researching Refugee Journeys by Gadi BenEzer and Roger Zetter in Journal of Refugee Studies.

At least in part as a result of poor conditions, increasing numbers of refugees leave the countries where they first arrive after fleeing their homes, and undertake the often perilous journey towards richer countries. An inability to protect and assist people in their regions is a major weakness of the current international protection regime, which is benefiting people smugglers who capitalize on the desire to move onwards. Here, the authors provide a conceptual and methodological framework for understanding the refugee journey; a fundamental first step to inform policy interventions to address the causes of onward movement, protect and assist refugees on the move, and ameliorate the often traumatic effects of the journey.

Stuck in Transit: Secondary Migration of Asylum Seekers in Europe, National Differences, and the Dublin Regulation by Jan-Paul Brekke and Grete Brochmann in Journal of Refugee Studies.

Another criticism of the international protection regime is its failure to achieve responsibility-sharing between states – this is an important goal for the ‘Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework.’ This article illustrates the problem, demonstrating how even within the European Union with its harmonized asylum and migration systems, asylum seekers move between countries. National differences in reception systems, welfare policies, and labour market opportunities are found to be the main motivations for secondary migration.

Riotous Refugees or Systemic Injustice? A Sociological Examination of Riots in Australian Immigration Detention Centres by Lucy Fiske in Journal of Refugee Studies.

In the absence of any formal mechanism for responsibility-sharing, it is asylum seekers and people-smugglers who select their destinations. In response, it is often asserted that there may be a risk of a ‘race to the bottom’ among industrialized states seeking to deter asylum seekers, for example by detaining asylum seekers and limiting their access to welfare and the labour market. Particularly strong criticism has been levelled at the Australian government in recent years. This article draws on testimonies of refugees detained in Australian immigration detention centres where they either participated in or witnessed riots. It concludes that conditions in these centres, such as solitary confinement, the excessive use of force, and the daily regimen of detention, almost guarantees that riots will take place.

Introduction: Accountability and Redress for the Injustices of Displacement by Megan Bradley and Roger Duthie in Journal of Refugee Studies.

A particularly intractable problem for the international protection regime has been to find enduring solutions for refugees. None of the traditional durable solutions – voluntary repatriation, local integration, and third country resettlement – is no longer providing options at the appropriate scale. This Introduction to ‘Accountability and Redress for the Injustices of Displacement’ emphasizes that effective voluntary repatriation depends on establishing mechanisms to achieve transitional justice, address grievances, and provide reparations. Repatriation is not simply a technical exercise of moving people across a border back to their homes; it depends on fully integrating returning refugees into politics and society, and realizing their potential to contribute to post-conflict reconstruction.

Introduction: Understanding Global Refugee Policy by James Milner in Journal of Refugee Studies.

Short overviews of a small selection of articles published by the Journal of Refugee Studies illustrate the challenges that lie ahead for states to negotiate a meaningful ‘Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework,’ from addressing root causes through to better protection and assistance within their regions to unlocking new solutions. Solid evidence widely disseminated is an important first step. But what happens next depends on negotiations within and between states, and at the level of the international community. James Milner helps lifts the veil on the rather opaque process of global refugee policy-making. It provides specific recommendations to ensure that the process is legitimate and transparent, to lead the international protection regime towards a meaningful response to one of the greatest contemporary global challenges.

Featured image credit: UN building USA by jensjunge. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Scaling the UN Refugee Summit: A reading list appeared first on OUPblog.

The old age of the world

At the home of the world’s most authoritative dictionary, perhaps it is not inappropriate to play a word association game. If I say the word “modern,” what comes into your mind? The chances are, it will be some variation of “new,” “recent,” or “contemporary.” This understanding of modernity is so ingrained that we rarely pause to reflect on its historical implications. Yet there is another way of conceiving the term, one that brings with it a whole different set of associations. What if we were to turn the telescope around, like Copernicus, and view modernity not as a new beginning, but as an end, as a period that is defined by the fact that it comes after everything else? What, in short, if we were to understand modernity as the old age of the world?

This simple inversion opens up a new approach to a whole range of assumptions about modern culture, history, and politics. If modernity emerges in this sense as a kind of historical late style, then the ways in which we understand late style – not only as it relates to major artistic figures such as Goethe, Beethoven, or Picasso, but also in terms of how it has been retrospectively constructed by critical tradition – become of central relevance to how we understand modernity. Much of modern literature, to take just one example, can be defined as an attempt to engage with, and ultimately to overcome, its belated historical status. Already in the Early Modern period, Francis Bacon argued that the old “age of the world … is the attribute of our own times,” a sentiment that Descartes reduced to the pithy claim “C’est nous qui sommes les anciens.” By the end of the seventeenth century, the Quarrel of the Ancients and Moderns placed the question of historical self-understanding at the center of debates about the legitimacy of modernity: in the words of Charles Perrault, “should our forefathers not be regarded as the children & we as the Elders and true Ancients of the world?” Perrault maps the development of cultural history onto the life of man not in order to describe the late seventeenth century as an era of virility, but as one of senescence: after the childhood of Antiquity and the adulthood of the Renaissance, mankind has now entered upon the old age of modernity. Seen from this perspective, modern literature from the eighteenth century onward emerges as what Thomas Hardy, in his description of Little Jude, calls “Age masquerading as Juvenility.”

Much of modern literature, to take just one example, can be defined as an attempt to engage with, and ultimately to overcome, its belated historical status.

Such a vision of modernity amounts to the flip-side of “progress,” that great god of post-Enlightenment secularity. It suggests that modern culture is shaped by the sense of an ending – to quote Frank Kermode’s influential phrase – as much as by the hope of beginning. Yet this is not as unremittingly negative as it may sound. For late style, in the traditional understanding of the term, is also great style, a way of conferring elite, timeless stature on a chosen canon of artists. As such, when applied to modernity as a whole it becomes a way of smuggling in the grandeur of culmination – a way of suggesting, to paraphrase Nietzsche’s joke about Hegel, that history culminates in your own house. To live in the old age of the world is to live in its climax.

That there is also an alternative, more muted model of lateness – the coda to the crescendo, so to speak – suggests the richness of the term: the idea of late style as predicated on illness or infirmity (Beethoven’s deafness, Paul Klee’s sclerosis) offers a model of increased productivity under the shadow of death. To trace the ways in which modernity has been understood as “late” is to realize, then, that it can have both regressive and progressive implications; every end implies a new beginning. If late style is like a Rorschach test, where the observer sees what she wants to see in the inkblot, then so is our view of late modernity, composed as it is of competing claims to historical superiority.

This is not to say, however, that lateness does not offer a concept of real substance; in an era obsessed with interdisciplinary, one of the reasons for the recent revival of lateness studies is surely its broad applicability across a range of subjects and cultures. Strategic expediency aside, perhaps the most compelling intellectual model for the universal resonance of lateness is offered by Theodor Adorno, the high priest of the discipline. Writing to Thomas Mann in 1951 about the latter’s novel The Holy Sinner, Adorno claims that lateness represents the very culmination of European identity: “It often sounds as though, at a certain decayed level of language, … you had somehow disclosed the latent possibility of a truly European language, one which was formerly obstructed by national divisions but now, at the end, shines forth as a primordial stratum precisely by virtue of its latest character.” Already for Adorno a term of aesthetic praise, lateness here literally becomes its own superlative. Modernism is understood not just as the late, but as the latest, as a category that collapses divisions both geographically (as a European meta-language) and historically (as a ‘primordial stratum’ now finally uncovered ‘at the end’). With all the pathos of the post-war yearning for reconciliation, Adorno offers lateness as something like the Esperanto of intellectual history – in theory comprehensible by all, but in practice understood by very few.

Returning to our word association game, then, perhaps we would do well to understand “modern” not just as new, but also as old; not just as innovation, but also as culmination; not just as a beginning, but also as an ending. In an ageing society, it may yet prove productive to conceive an ageing world.

Featured image credit: “Double Word and Triple Letter Score” by Dustin Gaffke. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post The old age of the world appeared first on OUPblog.

Periphrastic puzzles

Let us say that a sentence is periphrastic if and only if there is a single word in that sentence such that we can remove the word and the result (i) is grammatical, and (ii) has the same truth value as the original sentence. For example:

[1] Roy murdered someone.

is periphrastic, since it is equivalent to:

[2] Roy murdered.

Thus, a sentence is not periphrastic if, for any word in the sentence, the result of removing the word is not grammatical, or the result of removing that word has a different truth value.

It should be noted that I am introducing “periphrastic” as a technical term here, and its use as defined above is different from (but connected to) its meaning in everyday English (further, the meaning here is significantly different from its technical meaning in grammar).

The notion of a sentence being periphrastic in this sense is simple, and at first glance we might think that we will always be able to determine whether a sentence is periphrastic merely by checking all of the sentences that can be obtained by removing one word. But like many other simple notions such as truth and knowability, it leads to puzzles – in this case, puzzles very similar to the truth-teller:

This sentence is true.

Consider the following sentence:

[3] I am periphrastic.

(We assume here that “I” is an informal way for a sentence to refer to itself).

Now, [3] is either periphrastic or not. But there seems to be no way to determine which it is.

If [3] is periphrastic, then there must be some word that we can remove from [3] such that the result is grammatical and true (since if [3] is periphrastic then, since that is what it says, it is true). The only way to remove a single word from [3] and obtain a grammatical result is:

[4] I am.

This sentence states that [4] exists, and is clearly true. Thus, the claim that [3] is periphrastic (and hence true) is completely consistent.

If [3] is not periphrastic, however, then the result of removing any word must either be ungrammatical or true (since [3] says that it is periphrastic, and thus in this case [3] is false). But, again, the only way to remove a single word from [3] and obtain a grammatical result is again [4], which is true. Thus, the claim that [3] is not periphrastic (and hence false) is completely consistent.

There would seem to be no other evidence that could settle the matter. Thus, even though it is obvious that [3] is either periphrastic or it is not, determining which seems impossible.

Interestingly, although most notions that allow for the construction of a truth-teller type puzzle also admit of a Liar-like paradoxical construction, I have failed to find an example of a paradoxical sentence that involves the idea of sentences being periphrastic. The obvious candidate to look at is:

[5] I am not periphrastic.

But there is nothing paradoxical about [5] – it is perfectly consistent to assume that [5] is false, and hence (contrary to what it says) periphrastic, since:

[6] I am not.

is a sentence obtained from [5] via the deletion of a single word that then has the same truth value as [5] – they are both false.

Perhaps my readers can do better. Is there a clearly paradoxical sentence that can be constructed using the notion of a sentence being periphrastic?

Featured image: Pieces Of The Puzzle by Hans. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Periphrastic puzzles appeared first on OUPblog.

September 17, 2016

Protests, pigskin, and patriotism: Colin Kaepernick and America’s civil religions

When civil religion meets football, you get … Colin Kaepernick. Just in case the rock you live under doesn’t have Wi-Fi, Kaepernick is a quarterback for the San Francisco 49ers who has drawn widespread attention for his decision to kneel in protest during the national anthem.

“When there’s significant change and I feel like that flag represents what it’s supposed to represent in this country, I’ll stand,” he announced.

The response from critics has been entirely predictable. Sarah Palin called him an “ungrateful punk.” Boomer Esiason labeled the quarterback “a complete and utter distraction and a disgrace.” And Donald Trump—the same Donald Trump who ironically enough doesn’t seem to think America is all that great right now—advised that Kaepernick “should find a country that works better for him.”

But for every detractor, there is an ally. More and more professional football players are joining in the protest, as are collegiate athletes and high schoolers. And prominent voices like Kareem Abdul-Jabbar are calling Kaepernick’s actions “very admirable.”

Thus, the embodied protest of one athlete has rippled out into a debate over racial injustice, patriotism, and the appropriateness of certain types of protest. It’s a story that has gained traction precisely because of its setting. The football field is America’s “new cathedral,” a sacred place where thousands gather to celebrate their team and their collective identity. Chargers, Jets, Ravens, Steelers. These are not just mascots or team names, but rather deeply meaningful markers of . “The Steelers are the heart and soul of Pittsburgh,” remarked one fan.

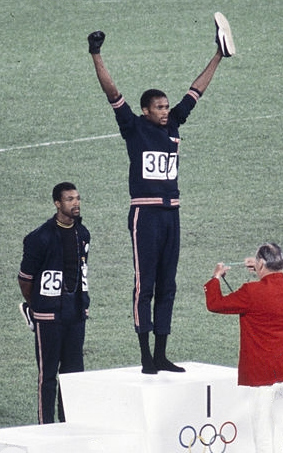

“John Carlos, Tommie Smith 1968” by Angelo Cozzi. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“John Carlos, Tommie Smith 1968” by Angelo Cozzi. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Add to this the fact that the protests are happening during a pregame ritual, which is supposed to unite “Us” as Americans. The Star Spangled Banner first played during the seventh inning of the 1918 World Series between the Boston Red Sox and Chicago Cubs. It was intended as a tribute to those fighting in the Great War, and it did indeed unite both opposing fans and players. “First the song was taken up by a few, then others joined, and when the final notes came, a great volume of melody rolled across the field,” reported the New York Times. “It was at the very end that the onlookers exploded into thunderous applause and rent the air with a cheer that marked the highest point of the day’s enthusiasm.”

While the French sociologist Émile Durkheim died one year earlier, it is entirely possible that his corpse twitched at this display of “collective effervescence.” In Durkheim’s formulation, religion has its very foundation in moments like these, when individuals feel “swept up into a world quite different from the one they see.” Here is where groups form a cohesive sense of “Us,” as well as a contrary “Them”—outsiders who do not share the same values and beliefs.

Scholars of civil religion have leaned heavily on Durkheim to think through how a pluralistic and diverse American nation can maintain a sense of unity. So it’s tempting to see Kaepernick and his ideological kin as a civil religious “Them,” profaning the sacred places of football and American patriotism. But as church historian Martin Marty observed, civil religion acts in both a priestly and prophetic mode. The former defends the status quo, while the latter resists it. We can think of Martin Luther King, Jr., who challenged white America to deliver on its promises of freedom and liberty to everyone. The protest of Kaepernick, then, is its own civil religious discourse. By kneeling, he and others are seeking to contrast and critique an America that is, with an America that ought to be. For this reason, many observers have been quick to identify parallels to the 1968 protest of American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos at the Mexico City Olympics. Like Kaepernick, their bodily gestures went off script, challenging a sacred convention. This led to outrage, as many echoed Brent Musberger who dubbed Smith and Carlos, “black-skinned storm troopers.”

For audiences in 2016 hearing this story, the critics are the ones who seem tragically out-of-place, holders of views contrary to how “We” define ourselves. But at the time, the prophetic stance of Smith and Carlos were equal parts shrill to some and inspiring to others. As the years passed, though, hostility faded while the image of their raised fists became iconic. Their decision to risk everything did the work of revealing an American blind spot on race and inequality.

Will Kaepernick become the new Smith and Carlos? Only time will tell. For now, at least, his protest has revealed the complexities of American civil religion—or, should I say, civil religions. Race, gender, class, ethnicity, region, and a host of other factors fuel an ongoing back-and-forth over the values that people believe transcend individual interests and contribute to the common good. The civil religious character of America is fundamentally unstable, with a center and periphery that changes alongside the topic, speaker, and time. But by viewing civil religion as an ongoing debate, we can better understand and contextualize those who stand, those who kneel, and those who can’t decide.

Featured image credit: “Colin Kaeperick During Super Bowl XLVII” by Austin Kirk. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Protests, pigskin, and patriotism: Colin Kaepernick and America’s civil religions appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers