Oxford University Press's Blog, page 462

September 22, 2016

Group work with school-aged children [infographic]

From student presentations, to lectures, to reading assignments, and so much more, teachers today have a wide variety of methods at their disposal to facilitate learning in the classroom. For elementary school children, group work has been shown to be one strategy that is particularly effective. The peer-to-peer intervention supports children in developing cognitively, emotionally, behaviorally, and socially. Group work encourages children to expand their perspectives on the world and understand that they are not alone in facing their problems. Group membership helps end children’s feeling of isolation, and demonstrates to them that others share similar experiences and emotions.

To better demonstrate some of the benefits of group work, we created an infographic based on a compilation of research by Craig Winston LeCroy and Jenny McCullough Cosgrove in the Encyclopedia of Social Work.

You can download the the infographic as a PDF or as a JPG.

Featured image credit: Syrian primary school children attending catch-up learning classes in Lebanon, by Russell Watkins for the Department for International Development. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Group work with school-aged children [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

Group work with school-aged children [Infographic]

From student presentations, to lectures, to reading assignments, and so much more, teachers today have a wide variety of methods at their disposal to facilitate learning in the classroom. For elementary school children, group work has been shown to be one strategy that is particularly effective. The peer-to-peer intervention supports children in developing cognitively, emotionally, behaviorally, and socially. Group work encourages children to expand their perspectives on the world and understand that they are not alone in facing their problems. Group membership helps end children’s feeling of isolation, and demonstrates to them that others share similar experiences and emotions.

To better demonstrate some of the benefits of group work, we created an infographic based on a compilation of research by Craig Winston LeCroy and Jenny McCullough Cosgrove in the Encyclopedia of Social Work.

You can download the the infographic as a PDF or as a JPG.

Featured image credit: Syrian primary school children attending catch-up learning classes in Lebanon, by Russell Watkins for the Department for International Development. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Group work with school-aged children [Infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

The targeted killing of American citizens

On 5 August, the Obama administration released a redacted version of its so-called “playbook” for making decisions about the capture or targeted killing of terrorists. Most of the commentary on Procedures for Approving Direct Action Against Terrorist Targets Located Outside the United States and Areas of Active Hostilities (22 May, 2013), has focused on section 3.E.2, which stipulates that “Nominations shall be presented to the President for decision … when (1) the proposed individual is a U.S. person.” Translated out of the bureaucratese: at least off the battlefield the President makes the final decision, personally, about the targeted killing of American citizens and permanent residents. Many people find this fact about the administration’s decisional process momentous.

But is it?

Reserving this decision for the President himself makes good political sense in light of the public uproar over the September 2011 drone strike that killed Anwar al-Awlaki, a high-ranking al-Qaeda planner and US citizen. It is understandable that the President might prefer to make the final call about reigniting that controversy. But there’s nothing very interesting about 3.E.2 if that is all it rests on, a prudential judgment about who should weigh the conflicting demands of strategy and public relations.

More interesting is whether Mr. Obama and his advisors share the belief of many commentators that there is something fitting in a deeper sense about the President shouldering personal responsibility for using deadly force against a fellow-citizen. Doesn’t the law, or the Constitution, require that “nominations” for death be “presented to the President for decision” when the nominee is a “US person?” Isn’t 3.E.2, underneath the antiseptic and obnoxious wording, a demonstration of our government’s fidelity to constitutional principle? The answer is no, if fidelity involves understanding our principles.

The Obama administration claims that its targeted killing policy is lawful under the Authorization for the Use of Military Force (the AUMF) that Congress enacted shortly after 9/11. Procedures for Approving Direct Action, in other words, describes the process for making certain military decisions in the conflict authorized and thus defined by Congress: the President may use “all necessary and appropriate force” against the perpetrators of 9/11 and their associates, but not against just anyone the executive perceives to be a “terrorist” or a threat. The administration’s own argument, then, is that its targeted killing policy is one means of conducting a congressionally authorized conflict against persons who are the 21st century, war-against-terror equivalent of uniformed Axis military personnel in the congressionally authorized Second World War.

The Obama administration claims that its targeted killing policy is lawful

The AUMF does not require that the President personally make the sort of targeting decision addressed by the “playbook.” This is hardly surprising: if the administration’s policy is lawful under the AUMF and international law, then as in the World War it is lawful to target specific enemy combatants, Admiral Yamamoto rather than some less skillful and dangerous Axis commander, to cite a famous example. Such an enemy combatant, then or now, is no more immune to the use of deadly force by the United States while drinking coffee or driving a car than he would be on the battlefield shooting at American soldiers. Neither the AUMF nor the Constitution requires that the President personally decide to target a specific enemy combatant, any more than such a decision is necessary on the battlefield, or against an enemy whose personal identity is unknown although his combatant status is clear.

By the administration’s own argument for the lawfulness of its targeted killing policy, the “playbook’s” insistence that this military decision be made by the Commander in Chief – unlike all the other command decisions about the use of force that the Constitution contemplates, and the AUMF authorizes – is legally superfluous. The fact that 3.E.2 concerns enemy combatants who are also US “persons” changes nothing. As the Supreme Court reaffirmed in the 2004 Hamdi decision, long-standing American practice and precedent reject the idea that citizenship somehow shields a person in arms against the United States from the use of military force. General Lee’s army, after all, was made up almost entirely of US citizens. (To question their citizenship is to say that Jefferson Davis was right, and Abraham Lincoln wrong, about the Civil War.)

What worries me is the suspicion that 3.E.2 reflects a belief, on the part of someone, that the targeted killing policy is something more (or is it less?) than an act of war, and that for this reason something beyond the ordinary processes of military decision is needed. If the Constitution gave the President a roving commission to kill dangerous people (whether citizens or not), then having the President take personal responsibility for doing so would make sense. But our Constitution neither grants the President, nor permits him to issue, an 007-style license to rid the world of anyone the executive branch suspects of being a threat.

Mr. Obama, admirably, has not claimed the authority to act in this manner. But the special role 3.E.2 reserves for the President in certain military targeting decisions is hard to understand otherwise, and the distinction it draws between “US persons” and others is pernicious. American citizenship is a high honor, but the foundation of the American Republic draws no ultimate distinction along that line: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all… are created equal.”

By affording citizen-enemies a procedural safeguard that it denies to others, Procedures for Approving Direct Action creates a precedent for treating foreign lives as less meaningful, less worthy of concern on the part of American decisionmakers, in a situation where neither law nor constitutional principle makes such a distinction. A future president, one less committed to Mr. Obama to respect for human life, may find this a useful precedent in claiming a free hand to deal summarily with “terrorists” as long as they owe no allegiance to this country. And history should give us little confidence that a legal category such as citizenship would long constrain a presidential James Bond, empowered to deal out death as he or she finds necessary.

Featured image credit: ‘Barack Obama,’ by Fort Bragg. CC BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post The targeted killing of American citizens appeared first on OUPblog.

September 21, 2016

In defence of moral experts

I’m no expert. Still, I reckon the notorious claim made by Michael Gove, a leading campaigner for Britain to leave the European Union, that the nation had had enough of experts, will dog him for the rest of his career. In fact, he wasn’t alone. Other Brexit leaders also sneered at the pretensions of experts, the majority of whom warned about the risks – political, economic, social – of a Britain outside the EU.

Those who dismiss experts have a habit of using the prefix “so-called”. Time will tell (probably not much time) whether Gove was right to dismiss the anxieties of “so-called experts”. Still, despite the beating he received in sections of the press, his was on politically safe ground. There is a suspicion of experts in Britain, part of a more general suspicion of elites and of the establishment.

The world of philosophy suffers from a similar malaise. There are few philosophers who can claim to be public intellectuals, at least in the Anglo-American world. As we know, the French are willing to embrace and celebrate their philosophers in a way that the British find uncomfortable. We have one or two philosophers with the flowing locks of Bernard-Henri Lévy but none with his profile or standing. It’s not just that the British public has a strain of anti-intellectualism, and a weaker appetite than the French for philosophical input to the national debate. It’s also that the few philosophers who do attempt to contribute to the world beyond the Academy risk ridicule within the profession. No doubt this is driven in part by an unworthy, if natural, envy. “They’re not serious” is the sotto voce (and sometime not so sotto voce) verdict of colleagues who appear in print or on TV or radio.

Within my sub-genre of philosophy – practical ethics – the suspicion of public engagement has a more specific cause. It’s often asserted that moral philosophers can’t claim expertize in ethics in the same way a chemist, for example, can be an expert on a molecule.

That’s a concern that puzzles me. Certainly there’s some evidence – from the UC Riverside philosopher Eric Schwitzgebel – that those who write about and teach courses in ethics are no more ethical than anybody else. And it’s true that specializing and so commanding authority in trichloro-2-methyl-2-propanol is disanalogous in various ways to being an authority in some corner of practical ethics – not least in how this expertize can be tested.

Michael Gove at Policy Exchange delivering his keynote speech ‘The Importance of Teaching’. Perhaps he should follow his own expert advice and learn from the experts. Image CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Michael Gove at Policy Exchange delivering his keynote speech ‘The Importance of Teaching’. Perhaps he should follow his own expert advice and learn from the experts. Image CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Still, I want to defend the expertize of moral philosophers, to maintain that their views in their chosen field merit respect and at least a degree of deference. We should heed attention because they have mastered the relevant information on their topic and brought to bear the philosopher’s chief tools, depth and clarity of thought. They have marshalled arguments and ironed out inconsistencies. And practical ethics is tough. To take just one example – trying to work through the metaphysics of what gives human beings moral status, and the implications of this for a variety of non-standard cases, is hugely complex. I endorse what the White’s Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Oxford, Jeff McMahan, says: “Questions about abortion and termination of life support, and euthanasia, and so on, are really very difficult. We are right to be puzzled about these issues, and people who think that they know the answers and have very strong views about these matters, without having addressed these issues in metaphysics and moral theory are making a mistake. They should be much more sceptical about their own beliefs.”

Sometimes the philosopher’s arguments about an issue merely shores up common-sense. But the role of the philosopher cannot merely be to describe the standard position. That would reduce philosophy to a branch of psychology, or anthropology, or sociology. The moral philosopher does not just ask how much people give to charity, or want to give to charity, relevant though these questions are, but how much should they give to charity. But whether it be John Stuart Mill on women’s rights, or Peter Singer on animal rights, philosophical reasoning can produce results that the then majority find objectionable, even repugnant. My appeal is that in such cases we should pay close attention to the philosophy, to how conclusions are reached. Our prima facie position should be that the philosopher has a good case.

There is some evidence that in their quiet way, British philosophers are beginning to assert themselves. I was delighted to see that in a recent week of five BBC essays devoted to post-Brexit Britain – three of the authors, John Gray, Onora O’Neill and Roger Scruton – were philosophers. In the book I’ve just edited, Philosophers Take On the World, over forty philosophers address stories in the news and argue for often counter-intuitive positions. Counter-intuitive perhaps, but my starting position is that we should take ethics experts seriously. Who knows, Mr Gove, they may even be right.

David Edmonds and other contributors from Philosophers Take On the World will be taking part in the OUP Philosophy Festival from 7th-12th November 2016. Click here for more information and to book your tickets.

Image Credit: Library, CC BY 2.0 via Pixabay.

The post In defence of moral experts appeared first on OUPblog.

Sticking my oar in, or catching and letting go of the crab

Last week some space was devoted to the crawling, scratching crab, so that perhaps enlarging on the topic “Crab in Idioms” may not be quite out of place. The plural in the previous sentence is an overstatement, for I have only one idiom in view. The rest is not worthy of mention: no certain meaning and no explanation. But my database is omnivorous and absorbs a lot of rubbish. Bibliographers cannot be choosers.

The topic of this post is the phrase to catch a crab. Those who are active rowers or rowed in the past must have heard it more than once. A century and a half ago, a lively exchange on the origin of this expression entertained the readers of the indispensable Notes and Queries. Especially interesting was a long article by Frank Chance, who started the discussion and whom I try to promote at every opportunity, because it is a shame how few people know his contributions and how seldom they are referred to, especially in comparison to the achievements of his namesake, the baseball player.

Catching a crab: A celebration.

Catching a crab: A celebration.The 1876 edition of Webster’s dictionary (the most recent at that time) explained that to catch a crab means “to fall backwards by missing a stroke in rowing.” Obviously, this definition is insufficient (even partly misleading), for catching a crab in rowing refers to the result of a faulty stroke in which the oar is under water too long (that is, when it becomes jammed under water) or misses the water. (However, the part I italicized seems, according to James Murray’s OED, to have been added by the uninitiated; see below.) Additionally, the rower who catches a crab often ends up with the oar getting stuck toward his or her stomach in the hara-kiri (seppuku) position and falls backwards, waving arms and legs. This detail will play some role in the subsequent discussion.

If we start our etymological search with a jammed oar, then the metaphor sounds obvious: the impression is that a malicious crab has seized the blade and won’t let it go. But why just a crab? And where did the idiom originate? It was Frank Chance who noted that “a man, when he has thus fallen backwards, and lies sprawling on the bottom of the boat, with his legs and arms in the air, does bear some likeness to a crab upon its back, but the use of the verb to catch shows that this cannot be the origin of the phrase” (yet he returns to the image later in his publication). I wonder whether he was the first to liken the prostrate man in a boat to a crab and the first to cite the Italian phrase pigliare un granchio (a secco), that is, “to catch a crab on dry ground,” figuratively “to make a blunder,” and to connect it with its English analog. Murray mentioned the Italian phrase but gave no references to Chance (whose opinions he respected).He read Notes and Queries quite regularly and must have been aware of the discussion. Whatever the origin of the idiom, the figurative meaning came after the direct one, as always happens in such cases. From the Italian point of view, catching a crab is a bad thing, and, indeed, seizing a crab on dry ground (a secco) or in the water without precautions should not be recommended. F. Chance wondered under what circumstances the crab came in. Perhaps he made a rather obvious thing look too complicated.

Crabs walk sideways (“crabwise”!), so that the inspiration for the idiom might have come from associating crabs with erratic behavior; such was the hypothesis in the Italian dictionary on whose authority Chance relied. But the same dictionary pointed out that the Italian phrase refers to the situation in which a finger is pinched severely, so that blood shows. Frank Chance concluded: “Most people who have walked upon the sands when the tide is out… have seen crabs lying about, and it has no doubt happened to some of them… to take hold of one of these crabs incautiously, and to get a finger pinched.” It is not clear whether he thought that the English phrase is a borrowing of the Italian one or whether, in his opinion, both languages coined it independently of one another, but he believed that in English the idiom had at one time had a broader meaning and was only later confined to rowing.

Catching a crab, the Italian way.

Catching a crab, the Italian way.Several experienced oarsmen offered their comments on the idiom. Thus, in Cambridge, as it turned out, the reference was to catching the water when it ought to be cleared, while on the Thames, “certainly about London,” the opposite was understood: to catch a crab meant to miss the water in the stroke and fall backwards over the thwarts, probably with the heels in the air. Other correspondents confirmed the latter definition. Since all of them were talking about the things they knew very well, it appears that the idea of missing a stroke did not originate with the uninitiated.

Chance, quite reasonably, retorted that all those niceties neither proved nor disproved his conclusion. Yet his etymology has an easily visible defect: he derived the idiom from a situation that could not have been important to too many people. One would have expected the phrase catch a crab to have originated among fishermen (who were probably pinched by crabs more than once). From them it would have become widely known as professional slang, first, in a community in which fishing for crabs was an important occupation. Later it would have spread to the rest of the population, the way sports metaphors, like bet on the wrong horse, too close to call, down the wire (to stay with the jargon of horse racing), and dozens of others do. Still later it would have been adopted by oarsmen, again as slang and a facetious statement.

The fact that the unlucky person “lies on the bottom of the boat, with his legs and arms in the air” probably contributed to the idiom’s move from fishermen to oarsmen, but the details remain hidden. To repeat what has been said above, the figurative meaning grew out of the direct one: pigliare un granchio still means almost what it must have meant to begin with, that is, “to pinch one’s finger.” Although the reference to the crab is lost, it means “to make a mistake.”

Catching a crab: Ignominy.

Catching a crab: Ignominy.It is rather improbable that exactly the same expression was coined in England. A phrase like to drop the ball, to give a random example, can originate anywhere at any time among those who try to catch the ball and fail, because ball games are universal. But being pinched by a crab is too specific for the same kind of treatment. I suggest that the phrase made its way to English (the written records of the idiom to catch a crab are late, none antedating the last quarter of the eighteenth century), retained its meaning “to make a mistake,” and was appropriated by oarsmen for whatever reason: partly because the oar that was jammed made the impression of being caught by a creature with strong claws, or because of the posture of the person who ended up lying on the bottom of the boat like a crab, or because crabs have in general a bad press, as evidenced by the adjective crabbed, the STD crabs, and perhaps by the noun crabapple. The other languages must have borrowed the phrase from English: fangen eine Krabbe in German, attratper une crab in French, poimat’ kraba in Russian, and probably elsewhere. Given my reconstruction, one wonders why and where the English heard the Italian phrase and what contributed to its popularity. Some boat race in Venice?

Images: (1) IMG_1377b2S by Phuket@photographer.net, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr. (2) P5060343.JPG by Allen DeWitt, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr (3) “Catching a Crab” by Anthony Volante, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image: Fishing, nets, crabbing by JamesDeMers, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Sticking my oar in, or catching and letting go of the crab appeared first on OUPblog.

Why the science of happiness can trump GDP as a guide for policy

For centuries, happiness was exclusively a concern of the humanities; a matter for philosophers, novelists and artists. In the past five decades, however, it has moved into the domain of science and given us a substantial body of research. This wellspring of knowledge now offers us an enticing opportunity: to consider happiness as the leading measure of well-being, supplanting the current favourite, real gross domestic product per capita, or GDP.

In the social sciences, data on individuals’ happiness are obtained from nationally representative surveys in which a question such as the following is asked:

“Taken all together, how would you say things are these days, would you say that you are very happy, pretty happy, or not too happy?”

There are many variants of this question. Instead of happiness, the question may be about your overall satisfaction with life, you might be asked to place yourself on a “ladder of life”. The common objective is to deliver an evaluation of the respondent’s life at the time of the survey. We can use the term “happiness” as a convenient proxy for this set of measures.

Meaning

In measuring happiness each respondent is free to conceive happiness as he or she sees it. You might think, then, that combining responses to obtain an average value would be pointless. In fact, there is now a substantial consensus that such averages are meaningful. A major reason for this is that most people respond quite similarly when asked about things important for their happiness.

In countries worldwide – rich or poor, democratic or autocratic – happiness for most is success in doing the things of everyday life. That might be making a living, raising a family, maintaining good health, and working in an interesting and secure job. These are the things that dominate daily lives everywhere; the things that people care about and which they think they have some ability to control. It means that comparisons among groups of people are possible.

Psychologists have investigated the reliability and validity of the measures and economists have studied the nature and robustness of the results. The data has withstood a thorough vetting. More support comes from the fact that many countries now officially collect happiness data. The same relationships are found between happiness and a variety of life circumstances in country after country. Those who are significantly less happy are typically the unemployed, those not living with a partner, people in poor health, members of a minority, and the less-educated.

Smile by LawPrieR. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Smile by LawPrieR. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.A personal paradox

I have to hold my hands up for one finding that has raised some doubts about the data’s meaningfulness. My work on happiness and income, published in an article more than 40 years ago, looked at the links between happiness and income. It found that surveys conducted at a point in time (so-called cross section studies) discover the expected positive relation – happiness increasing with income. However, in studies of happiness and income over the longer term (the time series relationship) the correlation is not there.

This might seem contradictory, but the difference in the cross-section and time-series results turn out to be explicable once we recognise that there are psychological mechanisms which significantly affect feelings of well-being. This might be social comparison or the tendency for people to adapt, at least partially, to major positive or negative events.

Some recent critics of this so-called Easterlin Paradox report a longer-term relationship between happiness and income that is positive. These results, however are based on data spanning a relatively small number of years, usually a decade or less, and pick up the short-term relationship – the ups and downs of happiness (and indeed GDP) that accompany economic booms and busts.

Preferences

So we can see that happiness and GDP can give quite different pictures of the trend in societal well-being. But why prefer happiness to GDP? There are several reasons.

Happiness is a more comprehensive measure of well-being. It takes account of a range of concerns while GDP is limited to one aspect of the economic side of life, the output of good and services. Perhaps the most vivid illustration of this can be seen in China where, in the two decades from 1990, GDP per capita doubled and then redoubled. Happiness, however, followed a U-shaped trajectory, declining to around the year 2002 before recovering to a mean value somewhat less than that in 1990. Economic restructuring had led to a collapse of the labour market and dissolution of the social safety net, prompting urgent concerns about jobs, income security, family, and health – concerns not captured in GDP, but which significantly affect well-being.

The evaluation of happiness is made by the people whose well-being is being assessed. For GDP, the judgement on well-being is made by outsiders, so-called “experts.” There are some who think of GDP as an objective measure of the economy’s output. In fact the numerous judgements involved in measuring GDP have long been recognised. Should the unpaid services of homemakers be included? What about revenues from drug trade or prostitution? Should the scope of GDP be the same for the US and Afghanistan? For the US in 1815 and 2015? In short, GDP is not a simple or “objective” measure of well-being.

Happiness is a measure with which people can personally identify. GDP is an abstraction that has little personal meaning for individuals.

Happiness is a measure in which each person has a vote, but only one vote, whether rich or poor, sick or well, old or young. Everyone in the adult population counts equally in the measure of society’s well-being.

Happiness tells us how well a society satisfies the major concerns of people’s everyday life. GDP is a measure limited to one aspect of economic life, the production of material goods. The aphorism that money isn’t everything in life, applies here. If happiness were to supplant GDP as a leading measure of societal well-being, public policy might perhaps be moved in a direction more meaningful to people’s lives.

A version of this post originally appeared on The Conversation.

Featured image credit: Jumping for joy, by Kilgarron. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Why the science of happiness can trump GDP as a guide for policy appeared first on OUPblog.

International Peace Day reading list

Today, September 21st, is the International Day of Peace. Established in 1981 by a unanimous United Nations resolution, International Peace Day “provides a globally shared date for all humanity to commit to Peace above all differences and to contribute to building a Culture of Peace.” The theme this year is sustainable development goals to improve living standards across the globe. These goals include: ending poverty, achieving gender equality, promoting sustainable economic development, and ensuring quality education for all. To commemorate Peace Day and encourage deeper thoughts about these issues, we’ve compiled a reading list of articles from the , the Oxford Encyclopedia of American History, and the Encyclopedia of Social Work that explore peace movements, policies, strategies, and global issues.

1. Sustainable Development by Dorothy N. Gamble

The viability of long-term human social systems is inextricably linked to human behavior, environmental resources, the health of the biosphere, and human relationships with all living species. Dorothy N. Gamble explores new ways of thinking and acting in our engagement with the biosphere, with attention to new ways of measuring well-being to understand the global relationships among human settlements, food security, human population growth, and especially alternative economic efforts based on prosperity rather than on growth.

2. Global Gender Inequality by Melissa B. Littlefield, Denise McLane-Davison, and Halaevalu F. O. Vakalahi

Mechanisms of oppression that serve to subordinate the strengths, knowledge, experiences, and needs of women in families, communities, and societies to those of men are at the root of gender inequality. At the core of gender equality is the value of womanhood and the need to ensure the health and well-being of women and girls. Littlefield, McLane-Davison, and Vakalahi examine how challenging traditional notions of gender is the basis for achieving gender equality. This process attends to the way in which the behavioral, cultural, and social characteristics that are linked to womanhood or manhood govern the relationship between women and men, as well as the power differences that impact choices and agency to choose. Although progress has been made toward gender equality for many women, lower income women—as well as women who face social exclusion stemming from their caste, disability, location, ethnicity, and sexual orientation––have not experienced improvements in gender equality to the same extent as other women.

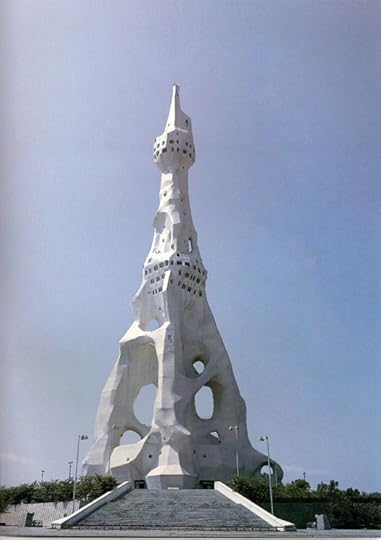

“Torre de Paz” by Silvio Vicente, Igreja Bela Vista, São Paulo, Brasil. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Torre de Paz” by Silvio Vicente, Igreja Bela Vista, São Paulo, Brasil. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.3. The Peace Movement since 1945 by Leilah Danielson

Peace activists pioneered the use of Gandhian nonviolence in the United States and provided critical assistance to the African American civil rights movement; led the postwar antinuclear campaign; played a major role in the movement against the war in Vietnam; helped to move the liberal establishment (briefly) toward a more dovish foreign policy in the early 1970s; and contributed to the political culture of American radicalism. Leilah Danielson examines how peace activism in the United States evolved in dynamic ways and influenced domestic politics and international relations between 1945 and the present.

4. The American Antinuclear Movement by Paul Rubinson

Spanning countries across the globe, the antinuclear movement was the combined effort of millions of people to challenge the superpowers’ reliance on nuclear weapons during the Cold War. Encompassing an array of tactics, from radical dissent to public protest to opposition within the government, this movement succeeded in constraining the arms race and helping to make the use of nuclear weapons politically unacceptable. Paul Rubinson explores how antinuclear activists were critical to the establishment of arms control treaties, even as anticommunists, national security officials, and proponents of nuclear deterrence within the United States and the Soviet Union actively opposed the movement.

5. by Gisela Mateos and Edna Suárez-Díaz

On December 8, 1953, in the midst of increasing nuclear weapons testing and geopolitical polarization, United States President Dwight D. Eisenhower launched the Atoms for Peace initiative. Gisela Mateos and Edna Suárez-Díaz look at how the implementation of atomic energy for peaceful purposes was reinterpreted in different ways in each Latin American country. This produced different outcomes depending on the political, economic, and techno-scientific expectations and interventions of the actors involved, and it provided an opportunity to create local scientific elites and infrastructure. The peaceful uses of atomic energy allowed the countries in the region to develop national and international political discourses framing the Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in Latin America and the Caribbean, signed in Tlatelolco, Mexico City, in 1967, and which made Latin America the first atomic weapons-free populated zone in the world.

6. Peace by Charles D. Cowger

Jane Addams helped us to understand the connection between bread and peace, and peace and social justice. Contrary to the citation often attributed to Pope Paul VI, “If you want peace, work for justice,” this phrase can actually be found in Addams’s book Newer ideals of peace (1906, p. 36). Charles D. Cowger’s article discusses the relationship of war and peace to social work practice, the historic and current mandate for social workers to work for peace, and the relationship between social justice and peace.

Featured image credit: “Miera Pagoda” by Agnese. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post International Peace Day reading list appeared first on OUPblog.

Financial networks and the South Sea Bubble

In 2015 the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography introduced an annual research bursary scheme for scholars in the humanities. The scheme encourages researchers to use the Oxford DNB’s rich content and data to inform their work, and to investigate new ways of representing the Dictionary to new audiences. As the first year of the scheme comes to a close, we ask the first of the 2015-16 recipients—the economic historian, Dr Helen Paul of Southampton University—about her research project, and how it’s developed through her association with the Oxford DNB.

What was the South Sea Bubble and what’s its importance for a history of early eighteenth-century Britain?

The South Sea Bubble was a financial bubble on the London stock market in 1720. The South Sea Company’s shares reached very high prices before the bubble burst. The event was widely considered to be a disaster and the result of folly and fraud. The whig politician, Robert Walpole, took charge and established his political dominance, becoming prime minister in the following year. Economic historians doubt that the Bubble caused as much economic damage as contemporaries seem to have believed. The political scandal was real enough and there was a public enquiry. The Chancellor of the Exchequer, John Aislabie, was even put into the Tower of London for a short time. The Bubble was reflected in popular culture and prints, plays and all sorts of ephemera appeared as critiques. Daniel Defoe wrote about the Bubble and William Hogarth created a print depicting it. The Bubble was often used as an excuse to criticize financiers as a class, and also to blame particular groups such as Jewish people, foreigners and women.

Your research focuses on people involved in the Bubble and their associates. How has the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography added to your knowledge of these networks?

The Oxford DNB entries highlight connections between people and locations which are not easy to discover in any other way. I’ve been able to link people as individuals but also to see how they formed groups (both informally and formally) which connect back to the Bubble. Family networks or political allegiances were so important in the crisis and its aftermath. The Oxford DNB is rich in its coverage of early eighteenth-century political actors. Simple word searches in Full Text identify, and provide more detail about, minor players who might otherwise be overlooked as they were not central to the event. It can become quite addictive to read up on these people as their biographies are only a click away.

You’ve chosen to represent these networks visually: what value can visualization bring to our understanding of Hanoverian political and financial networks?

Visualizations help make complex networks easier to understand. They also show just how many different people were involved in each network and how closely they were connected to major players. It is possible to highlight connections which may have not been noted before. Digital humanities technologies allow a very simple diagram to be used to show connections between nodes (representing individual ODNB entries), and the interconnection of people via sub-networks we might not previously have identified as sharing a political or financial association. By clicking on the node, you can read about the person on the ODNB site. Thanks to a visual representation, it’s easy to see the overall network or to focus in on specific details. Ultimately, the visualization is just a digital version of drawing out a network on a piece of paper, though online it’s much more manipulable and extensible. It is highly intuitive.

I had no idea that the ODNB had so many features beyond the biographies themselves.

You’re also working with the National Trust: why is the South Sea Bubble, and its legacy, of interest here?

The National Trust manages Studley Royal (a world heritage site) and its adjoining property of Fountains Abbey in North Yorkshire. Studley Royal was owned by John Aislabie who was Chancellor of the Exchequer at the time of the Bubble. Aislabie fell from power and retired to Yorkshire to build his famous water gardens, so there a close connection between Hanoverian high politics and finance and this country house and grounds. Visitors and guides are still reliant on the old ‘gambling mania plus fraud’ explanation for the existence of the Bubble. This story implies that investors were all fools or gambling mad and that many lost fortunes in the South Sea. It ignores the rational reasons to invest in the South Sea Company itself. The Company helped the government service part of the National Debt, for which it received a fee, and it also engaged in the trade of enslaved people. Popular histories tend to exclude these details which make it difficult to understand why anyone would invest money. In addition, people who made money or who only lost a small amount are not focused on. Economic historians believe that the traditional version is an oversimplified story. It also tends to leave out the importance of slavery in the South Sea Company’s history.

What are uses of the Oxford DNB for historical research that you’ve come across during your bursary year?

The same visualization process can be applied to many other topics. The ODNB’s editors have suggested other eighteenth-century groups and networks which could benefit from the same treatment. They have also suggested linking in other ODNB resources such as their podcast collection. I had no idea that the ODNB had so many features beyond the biographies themselves. You can discover more about what is possible by having old-fashioned face-to-face meetings. Even though this is a digital project, it’s been really beneficial to come to Oxford and to meet the Dictionary’s editorial team. Networks of historical actors are important, but so are networks of historians themselves. I’ve learned a lot about the ODNB from doing this project, but I’m sure that there is more to discover.

What are the next steps for your research?

I would like to provide more online material for guides and visitors at Studley Royal using a new technology called Blupoint. This is designed to work at sites with little or no Wifi coverage. It was developed at the University of Southampton for use in remote parts of Africa. However, it would be ideal for the Studley Royal site which has problems with coverage. I’m also undertaking some more traditional archival research involving a group of investors based outside of London. They granted power of attorney documents to their representatives and some of the documents remain. I came across these records by a lucky accident—they were kept because a local antiquarian liked the signatures on the documents. I have not come across anything similar, so they were a real find. In the longer term, I would like to write a book about John Aislabie and the South Sea Bubble. It is useful to use the visualization to see how he fits in with the many other participants in the event, and how these relationships developed, taking in new people, after the Bubble.

Featured image credit: “South Sea Bubble”, by Edward Matthew Ward. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Financial networks and the South Sea Bubble appeared first on OUPblog.

September 20, 2016

100 years of the X-ray powder diffraction method

X-ray diffraction by crystalline powders is one of the most powerful and most widely used methods for analyzing matter. It was discovered just 100 years ago, independently, by Paul Scherrer and Peter Debye in Göttingen, Germany; and by Albert Hull at the General Electric Laboratories, Schenectady, USA.

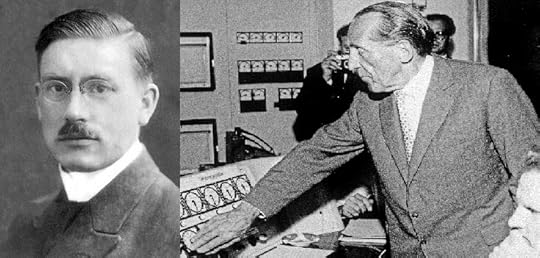

Figure 1. Right: Peter Debye in 1912. Image Credit: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. Left: Paul Scherrer. Image Credit: Courtesy of Paul Scherrer Institut, Vilingen, Switzerland. Used with permission.

Figure 1. Right: Peter Debye in 1912. Image Credit: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. Left: Paul Scherrer. Image Credit: Courtesy of Paul Scherrer Institut, Vilingen, Switzerland. Used with permission.Debye, born in Maastricht, the Netherlands, was at first assistant to A. Sommerfed in Munich, then successively Professor at the Universities of Zürich, Utrecht, and Gronigen. In 1912, he published a paper on specific heat and lattice dynamics which made Sommerfeld fear Max von Laue’s planned experiment might fail, which it didn’t, as we know. In a series of papers published in 1913, Debye calculated the influence of lattice vibrations on the diffracted intensity (the Debye factor), and, in February 1915, he expressed the intensity diffracted by a random distribution of molecules. This prompted him to incite his student Paul Scherrer to try and observe the diffraction of X-rays by a crystalline powder.

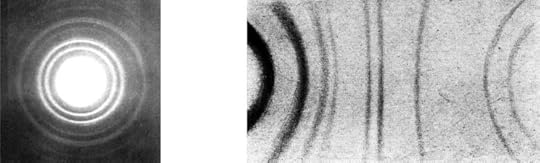

Figure 2. Powder diffraction diagrams: Left: aluminium filings. ©1917 by the American Physical Society, used with permission. Right: graphite filings by Debye and Scherrer, 1917. Used with permission.

Figure 2. Powder diffraction diagrams: Left: aluminium filings. ©1917 by the American Physical Society, used with permission. Right: graphite filings by Debye and Scherrer, 1917. Used with permission.Scherrer, who was preparing his thesis under Debye, first tried charcoal as a sample, with no result. He then constructed a cylindrical diffraction camera, of 57 mm diameter, with a centering head for the sample, a very fine crystalline powder of lithium fluoride (LiF). They were happily surprised by the sharpness of the lines of the first diagram, which they correctly interpreted as that of a face-centered cubic crystal. The work was presented to the Göttingen Science Society on 4 December 1915 and submitted to Physikalische Zeitschrift on 28 May 1916. A second work, also published in 1916, was devoted to diffraction by liquids, in particular benzene, and a third one, published in 1917, on the structure of graphite (Fig. 2, right). In 1918, Scherrer published a seminal paper on the relation between grain size and line broadening (the Scherrer formula). This formula, modified by N. Seljakov in 1925 and generalized, first by Max von Laue in in 1926, then by A. L. Patterson in 1928, plays a major role in the applications of powder diffraction. The same year, Debye and Scherrer deduced from the analysis of the intensity of the diffraction lines that, in LiF, one valence electron is shifted from the lithium ion to the fluorine ion, a first step towards the study of electron density with X-ray diffraction.

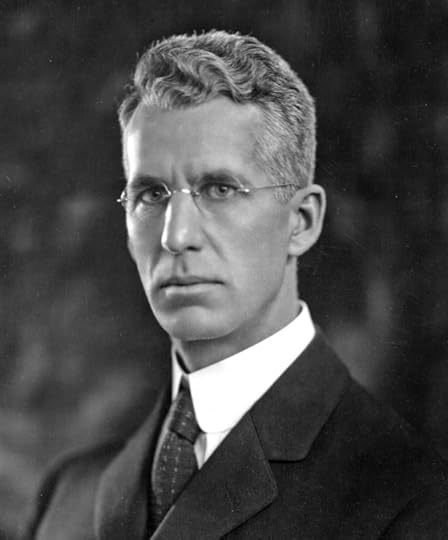

Albert Wallace Hull. Image Credit: AIP Emilio Segre Visual Archives, used with permission. Physics Today Collection. Used with permission.

Albert Wallace Hull. Image Credit: AIP Emilio Segre Visual Archives, used with permission. Physics Today Collection. Used with permission.Albert Hull was at first a professor at the Worcester Polytechnic Institute, MA before joining General Electric Laboratories in 1914. At the occasion of a visit by Sir W. H. Bragg, Hull had asked the “big man” whether the structure of iron was known. Upon the answer that it wasn’t yet, Hull saw there a challenge and he decided to try to find the structure of crystalline iron. Since he didn’t have a single crystal of iron available, he used iron filings instead. He rapidly obtained good diffraction patterns and found a 3% Si iron crystal, showing that its diffraction pattern was that of a body-centered cubic crystal. He then went back to the powder diffraction pattern and correctly interpreted it. These results were presented on 27 October 1916 at a meeting of the American Physical Society and published at the beginning of 1917. At that time, in the middle of the First World War, the echo of the researchers in Germany had not come to him. Observing the decrease in intensity with increasing Bragg angle, Hull concluded that the X-rays were diffracted by the electron cloud around the nucleus, and not by point diffraction centers. Diffraction by powders thus led both Debye and Scherrer and Hull to make observations of a fundamental nature. Hull then undertook an impressive series of 26 structure determinations of elements including Al (Fig. 2, left), Ni, Li, Na, and graphite. Debye and Scherrer had concluded that graphite was trigonal, but Hull showed that it is hexagonal.

Powder diffraction spread rapidly and easily since it didn’t require specimens of a good crystalline quality. Its fields of applications are very wide in mineralogy, petrology, metallurgy, and materials science. One of the difficulties of the method lies in the indexation of the diffraction lines for non-cubic samples, particularly if there are no crystallographic data available. A systematic mathematical analysis scheme was proposed by C. Runge as early as 1917, but it is cumbersome, and it was only applied when computer programs were developed. Another scheme was proposed by Hull himself and his co-worker W. P. Davey in 1921. It makes use of d-spacing plots of all possible diffracting planes, and is particularly suitable for crystals belonging to the trigonal, tetragonal, or hexagonal systems.

The first of the applications of powder diffraction is the determination of crystal structures and lattice parameters. The method was improved by W. H. Bragg in 1921 by using a flat powder sample and an ionization chamber to measure intensities. H. Seeman, in 1919, and H. Bohlin, in 1920, used a curved sample and focalizing spectrometer, a set-up further ameliorated by J. C. M. Brentano in 1924. A great many structures of alloys were determined in the 1920s, both in Europe and in the United States. Accurate phase diagrams could now be established and phase transformations such as order-disorder transformations were observed. The determination of more complex structures was, however, difficult and had to wait for the development of new refinement techniques by Hugo Rietveld in 1966. This led to a complete renewal of the powder diffraction method, with applications to the study of different classes of new materials in chemistry, materials science, and biology.

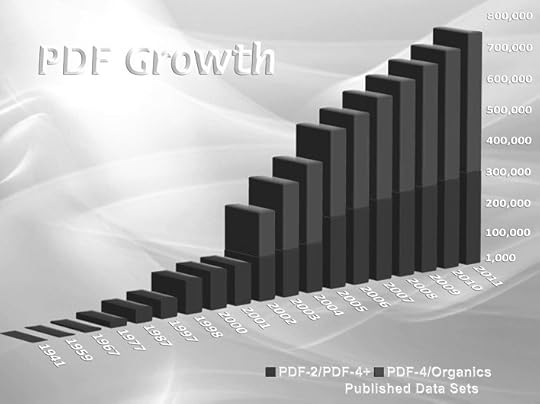

Growth of the Powder Diffraction File (PDF) since 1941. Image Credit: Courtesy of the International Centre for Diffraction Data. Used with permission.

Growth of the Powder Diffraction File (PDF) since 1941. Image Credit: Courtesy of the International Centre for Diffraction Data. Used with permission.The diffraction lines in a powder diagram are also very sensitive to the degree of perfection of the crystal. A general analysis, taking distortions within the grains into account, was given by A. R. Stokes and A. J. C. Wilson (1942, 1944). The profile of the lines depends both on the size of grains, as mentioned above, and on the distribution of defects. B. E. Warren and his school studied in the 1950s the influence on line shape of micro-twins and stacking faults such as those introduced during cold-work of metals and alloys. During annealing of these materials, the grains recrystallize along preferred orientations, their size increases, and the diffraction lines become discontinuous.

Another major application of powder diffraction is the identification of crystalline phases and unknown substances. It was introduced as early as 1919 by Hull as a new method of “X-ray chemical analysis”. The powder diagram of a given substance is indeed unique and specific of that substance, like a fingerprint. It is therefore possible to identify a material by comparison of its diagram to those of known substances sorted in databases. J. D. Hanawalt and H. M. Rinn of the Dow Chemical Company proposed in 1936 a search scheme. In 1937, the “Powder Diffraction File” was established by a committee set up by the American Society for Testing and Materials. This file is maintained since 1969 by the Joint Committee on Powder Diffraction standards, which became in 1978 the International Centre for Diffraction Data. There are now more than 700,000 substances included in the file.

Feature image credit: X-ray diffraction pattern of crystallized 3Clpro, a SARS protease. (2.1 Angstrom resolution) by Jeff Dahl. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post 100 years of the X-ray powder diffraction method appeared first on OUPblog.

What should “misundertrusted” Hillary do?

Using his now famous malaprop, the 2000 GOP presidential candidate George W. Bush declared that his opponents had “misunderestimated” him. All politicians suffer from real or perceived weaknesses. For Bush, his propensity to mangle the English language caused some to question his intellectual qualifications to hold the nation’s highest office. Yet his unpretentiousness and authenticity made him the candidate Americans said they would like to have a beer with. And he twice won the presidency, a feat his more patrician father failed to achieve.

The 2016 Democratic candidate faces two deficits that threaten her decade-long quest to become the first woman president of the United States. More than half of those polled do not find her honest or trustworthy. Her unfavorability ratings are equally high. What is it about Hillary Clinton that prompts such visceral hatred among her opponents?

In October 2009, a year after her close and searing defeat to Obama, Hillary declared that she would not run again for president and looked forward to retirement. But much like Richard Nixon, Hillary Clinton keeps coming back. When I saw her campaigning for Alison Lundergan Grimes in the 2014 Kentucky Senate race against Mitch McConnell, I knew that she would toss her cap into the 2016 presidential race. That October day, Hillary Clinton was on fire. To the strains of Katy Perry’s feminist anthem, “You’re gonna hear me roar,” she appeared before a Louisville convention hall filled with rapturous Democratic faithful. McConnell won the reelection, but with her 65% approval rating while secretary of state, Clinton seemed certain to be the next Democratic presidential nominee.

Also like Nixon, Clinton is now an unpopular, untrusted candidate. But once she enters office, Hillary has proved herself each time: as First Lady, as senator, as secretary of state. Whenever Nixon faced an electoral obstacle, he reinvented himself. He was the loving husband and father in his 1952 Checkers Speech, the dutiful vice president to Ike in 1960, the knowledgeable statesman in 1968. “He’s tanned, he’s rested, he’s ready,” was the waggish description of how the enigmatic Nixon could resurrect himself at any moment to run for office.

Hillary Clinton has recreated herself throughout her historic public life. In Arkansas, when her husband was running for governor, she took his surname to seem less feminist. When the healthcare initiative failed under her leadership as First Lady, Mrs. Clinton realized that Americans didn’t want an unaccountable presidential spouse running a policy shop, so she reverted to a more traditional model of White House wife. Viewed as a hyper-partisan by some, she reached across the political abyss as a senator from New York and earned bipartisan praise for her legislative skills.

92% of Americans polled say they would vote for a qualified woman for president. That’s up from 75% who responded similarly when I first began studying the question forty years ago. Still, Hillary finds herself caught in a dilemma. The presidency has only been viewed through the lens of male leadership models that reward toughness and aggression. What is a female candidate for that office to do when voters view her gender as compassionate and sensitive? Appear too “soft” and the commander-in-chief role seems unattainable, especially in an era of worldwide terrorism. Yet, if she follows a masculine leadership paradigm, she risks appearing threateningly unfeminine to some.

Hillary’s State Department e-mail fiasco has exacerbated doubts about her fitness for office. FBI Director James Comey declined to recommend indicting her, but she faces damning charges of carelessness. Can she rise up one more time by presenting herself as a competent, knowledgeable, sane, mature leader, in contrast to the persistently erratic and defamatory Donald Trump?

What would George W. Bush do? When I spent more than an hour with him and a small group of students at the University of Louisville in 2007, I observed how personable, witty, accessible, and, yes, eloquent he was. That experience helped me understand how he had defeated charismatic Texas governor Ann Richards in 1994, earned his party’s 2000 presidential nomination, and won two terms in the White House. In retail politics, he was himself, comfortable in his own skin.

And therein lies another lesson for Hillary Clinton. She may not be able to reverse the trust deficit, but, rather than creating yet another persona, causing voters to question her authenticity, the former First Lady, senator, and Cabinet secretary should be herself. Those who have met her one-to-one or in small groups describe her as warm, engaging, genuine, caring.

Of course, Mrs. Clinton runs the risk of seeming too feminine, indeed maternal, as she runs for the office dominated for more than two centuries by father figures. If her opponent disparages her gender, she should borrow a page from John F. Kennedy’s successful 1960 presidential campaign playbook. When he realized that his Catholicism would not fade as an issue, he eloquently defended his free exercise of religion, while noting that his public policies would not be shaped by it, in a landmark speech to Protestant ministers in Houston. JFK breached the religious barrier to Catholics serving as president and overcame decades of discrimination against Irish immigrants. Barack Obama addressed the burden of race in his 2008 breakthrough speech after the dustup over his controversial pastor Jeremiah Wright.

Hillary Clinton has fewer than two months left, after three decades in the public arena, to define herself and her vision for the American people. She now seems at peace with describing herself “as her mother’s daughter and her daughter’s mother.” But the Democratic candidate also relates the story of how her mother, born on the day Congress passed the women’s suffrage amendment in 1919, taught her to stand up to bullies. Combining strength with compassion, much as Bush 43 promoted “compassionate conservatism,” to address societal ills, may be Hillary’s winning strategy.

Featured image credit: Hillary Clinton by Gage Skidmore. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post What should “misundertrusted” Hillary do? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers