Oxford University Press's Blog, page 460

September 28, 2016

Profiling schoolmasters in early modern England

In 2015 the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography introduced an annual research bursary scheme for scholars in the humanities. The scheme encourages researchers to use the Oxford DNB’s rich content and data to inform their work, and to investigate new ways of representing the Dictionary to audiences outside of academia. As the first year of the scheme comes to a close, we ask the second of the 2015-16 recipients—the early modern historian, Dr Emily Hansen—about her research project, and how it’s developed through her association with the Oxford DNB.

Can you introduce your research to a non-specialist audience and explain why it’s important?

My research is on the topic of schoolmasters working in England between the end of the fifteenth century and the middle of the seventeenth century. This project developed out of my PhD thesis, which was about grammar school education more generally in England during the same period. Focusing on schoolmasters who taught in grammar schools, my current project uses the Oxford DNB to build up a detailed picture of the biographical attributes of members of this profession. These include schoolmasters’ education levels, social background, how long they spent teaching, and whether they did anything else either before, during, or after their time as a schoolmaster—as well as how teaching was viewed and regulated during this time. This can tell us more about the occupation of teaching during a crucial period in the development of education in England, as well as increase our understanding of how wider religious, intellectual, and cultural changes during this period impacted on the lives of schoolmasters and the working of grammar schools.

The subject of education history, and by extension of teaching, is often under-studied; a very popular subject of study back in the 1970s, it has fallen under the radar somewhat, and current research on early modern education tends to focus more on the humanist curriculum of English grammar schools, looking at what was being taught; by focusing on the people who were doing the teaching (and there nearly 100 with entries in the ODNB), I’m to fill a gap in our knowledge of early modern education, as well as broaden our understanding of the history of teaching.

You’re undertaking a prosopographical approach to early modern schoolmasters: what is prosopography and what are its uses for understanding the past?

Prosopography is the study of individual members of a particular group of people, examining elements of their lives in order to better understand that group—in this case, those who worked in a teaching capacity. It is somewhat related to biography (and biographies can be a valuable source in prosopography), but differs in that the focus is on understanding the group collectively rather than on one specific person or select network of individuals.

How have you used the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography for your research?

The Oxford DNB contains close to one hundred entries for men who are classified as ‘schoolmaster’, or as schoolmaster and something else (most commonly ‘writer’ or ‘clergyman’); a search by occupation will yield these results. The detailed nature of these entries provides information that’s helped me to build up a profile of the profession, based on this sample of notable practitioners.

The subject of education history, and by extension of teaching, is often under-studied

In addition, the Dictionary includes over a thousand entries which can be viewed through a full text search for ‘schoolmaster’ or ‘headmaster’. I have had to comb through these to some extent, as sometimes the search term will appear in an unrelated context; but in many other cases, it will bring up an entry for a man who might be better known as a writer, a clergyman, or something besides schoolmaster, but who in fact spent some length of time teaching at a grammar school.

What new information, or new lines of inquiry, has the Oxford DNB provided?

One of the strongest themes to emerge from these ODNB biographies is the sometimes transient nature of a teaching career during the early modern period. It was so often the case that one might spend only a short time teaching before opting for another profession—typically the clergy—and the ODNB entries have certainly demonstrated this: biographies for those who are classified by the Dictionary as ‘schoolmasters’ will often, though not always, show that the schoolmaster in question left to do other things besides teach; this typically involved writing or publishing, entering the church, or sometimes taking up medicine or becoming involved in local politics.

Those with entries in the ODNB who are principally classified as writer, clergyman, or some other profession, often spent time teaching during the first part of their adult lives. This is often an aspect of their biography that’s overshadowed by their later careers, but which tells us a great deal about where a teaching position might sit in relation to the development of their career. Reading these entries in an approximately chronological order gives some sense of change over time as well. In addition, ancillary references in ODNB entries, for example to wills held at the National Archives, have allowed me to expand on an individual master’s career—with reference to his family, material possessions and wealth at the end of his life.

What are the next steps for your research?

There is a great deal of scope for comparative work with a study like this, and I would like to compare English schoolmasters to those who taught elsewhere in Europe and in Scotland, focusing on the same questions: educational and social background, the ‘shape’ of a teaching career, and contemporary attitudes towards teaching.

I would also like to set this research in a wider chronological context, examining how early modern English schoolmasters compare to those working in medieval England, and to those of later seventeenth- and eighteenth-century England. The role of the assistant schoolmaster, the usher, is also an area I have begun to explore further.

While this project could stand on its own as a substantial article about early modern English schoolmasters, and will, I hope, contribute eventually to a monograph based on my PhD, I also envision it becoming a book chapter considering either the history of the teaching profession, or perhaps the professions more widely—with a focus on the biographical attributes, and life choices and trajectories, revealed in the Oxford DNB and other sources.

Featured image credit: School chalkboard. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Profiling schoolmasters in early modern England appeared first on OUPblog.

September 27, 2016

How fertility patients can make informed decisions on treatment

Media coverage of health news can seem to consist of a steady diet of research-based stories, but making sense of what may be relevant or important and what is not can be a tall order for most patients. Headlines may shout about dramatic breakthroughs, exciting new advances, revolutions, and even cures but there may be scant details of the evidence base of the research. Has it been the subject of a double-blinded randomized controlled trial or is it based on case reports? How does the lay reader assess its significance? Is the new advance ready for use, or is this just a first step on a research path which may come to an early dead end?

For the fertility patient, effectiveness is judged by success and an effective treatment is one which results in a positive pregnancy test. They want to be sure that they are not missing out on anything which might make a difference, which is why many choose to opt for a cocktail of conventional treatment with add-ons and complementary therapies. What isn’t always clear is the level of “difference” they expect this to bring. For patients, a treatment which makes a difference suggests a difference between success and failure, while the scientist developing a new technique may be thinking of an increase in single figures. Hyped headlines bring new hope, but may not make it clear that there are still many hoops to jump through before anyone can be certain that a treatment is either safe or effective.

Patients often spend considerable time researching their condition and possible treatments, which means scouring the Internet for anything and everything relevant that they can find, but making value judgments about the relative merits of different sources of information is not always easy. Newspaper headlines are not always treated with the skepticism they may deserve, and the impact of patient-to-patient advice given through online fertility networks should not be underestimated. Anecdotal evidence about others who have been successful after making use of new techniques can have a more powerful effect than experts questioning the scientific evidence base. Clinic success rates are also often seen as a reliable assessment of any particular techniques they may be using.

Kate Brian (Author’s own photo, used with permission)

Kate Brian (Author’s own photo, used with permission)Going back to the original research paper may seem the obvious suggestion for anyone wanting to assess the truth behind the anecdotal success story or hyped headline, but patients with no experience of reading scientific papers may not be clear about the relative merits of different types of research. The world of scientific research can also present a linguistic challenge as a relatively straightforward theory may appear incomprehensible to a lay reader who would not struggle with the concept, but is hindered by the scientific terminology which works against their understanding.

This is why lay summaries of new research papers are a necessary development for fertility patients. Patients should be able to have open access not only to the papers themselves but also to a compact précis of what the new research means and why it may be relevant to them. This is hugely empowering to those who may feel they have lost control of what is happening to them as they have progressed through fertility tests and treatments. It offers them the opportunity to regain control as they will be able to assess for themselves the relevance of research papers in a way that they can easily understand.

There may be wider benefits to encouraging patients to engage with research. A clearer appreciation of the importance and impact of research may prove to be beneficial when it comes to recruitment of participants for clinical trials. If, in turn, the research community becomes more engaged with those they are researching, it can help the work they are doing to become more patient-centred and more relevant to patient needs and to what they consider to be most important. Patients may also bring their own views about what is right or wrong about research and how it is carried out, responded to, and implemented.

Fertility patients are hungry for knowledge about their condition and how it can be treated, yet it is clear that finding reliable information can be a challenge – and that’s where open access lay summaries on reproductive research should come in.

Featured image credit: ‘Pregnant woman talking to her doctor in a room’ designed by ©Pressfoto via Freepik.

The post How fertility patients can make informed decisions on treatment appeared first on OUPblog.

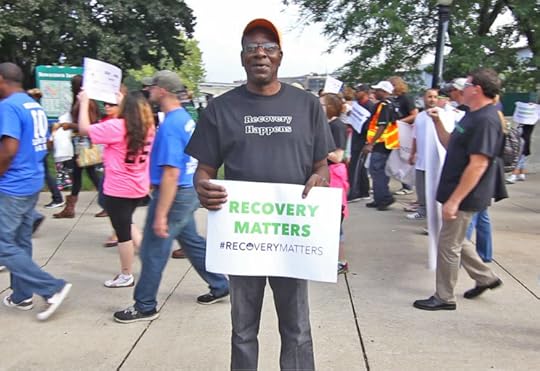

The impact of addictions and means of prevention, treatment, & recovery

September is National Recovery Month in the US. National Recovery Month is a time dedicated to increasing awareness and understanding of substance use and mental disorders. It’s also a time to celebrate those who are in recovery and those who do recover. The goal of the observance month is to educate others that addiction treatment and mental health services are effective, and that people can recover. With respect for this time, we compiled some statistics on addiction disorders to support awareness of these issues and show that individuals are not alone. Recovery is possible.

1. In the US, according to 2005 data, an estimated 22.2 million persons (9.1% of the population aged 12 or older) were classified as abusing or dependent on a substance.

2. Substance abuse causes more deaths, illnesses, accidents, and disabilities than any other preventable health problem.

3. Tobacco use is the leading preventable cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States, accounting for approximately 443,000 deaths, or 1 of every 5 deaths each year. An additional

8.6 million people will have at least one serious illness caused by smoking.

4. Tobacco use is also related to approximately 5.1 million years of potential life lost (YPLL), consisting of 3.1 million YPLL for males and approximately 2.0 million YPLL for females annually.

5. Alcohol annually contributes close to 100,000 US deaths from drunk driving, stroke, cancer, cirrhosis of the liver, falls, and other adverse effects.

6. Nearly half of all violent deaths (accidents, suicides, and homicides), particularly of men below age 34, are alcohol related.

7. As many as 29% of all children in the United States are exposed to familial drug or alcohol abuse, according to some statistical data.

8. About 5 million adults and 3 million youths in the United States meet clinical criteria for a gambling disorder. Yet, there is currently no designated federal funding for prevention, intervention, treatment, or research for gambling disorders, and states are left to adopt varying standards on an ad hoc basis.

Michigan Celebrate Recovery Palooza by Sacred Heart. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Michigan Celebrate Recovery Palooza by Sacred Heart. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.9. The standardized rate of problem gambling in 2012 ranges from 0.5% to 7.6%, with a mean of 2.3%, according to a comprehensive worldwide review of prevalence studies, (Williams, Volberg, and Stevens, 2012). Above-average rates were found in Belgium and Northern Ireland, with the highest prevalence rates observed in Singapore, Macau, Hong Kong, and South Africa.

10. In a national study in the United States, more than 73% of disordered gamblers met criteria for an alcohol use disorder, 38% for a drug use disorder, 60% for nicotine dependence, 50% for a mood disorder, 41% for an anxiety disorder, and 61% for a personality disorder.

11. High rates of gambling pathology have been identified among prisoners, probationers, and parolees. One study reported that 34% of non-imprisoned participants who were on remand, probation, or parole at the time of the study met criteria for disordered gambling, and 38% did so for problem gambling. About 25% of those surveyed endorsed gambling as a key contributor to their offense, and nearly 50% of respondents reported obtaining money illegally to gamble. Another study reported that about 20% of newly sentenced inmates claimed their crime was gambling-related, 21% met criteria for gambling disorder at the time of assessment,

and 16% did so in the six months before going to prison.

Less than one-fourth of all individuals who need help for their abuse or dependence on alcohol or other drugs receive treatment. Nonetheless, studies indicate that for those who do obtain treatment, treatment does work. Gambling disorder is an addiction that is often not sufficiently included in discussions about addictions. Gambling is seldom included in routine screenings in schools, mental health centers, health settings, child welfare agencies, senior centers, or other areas.

More information about prevention, treatment, and recovery can also be found in:

– “Alcohol and Drug Problems: Practice Interventions” by Maryann Amodeo and Luz Marilis López

– “Alcohol and Drug Problems: Prevention” by Flavio F. Marsiglia, David Becerra, and Jaime M. Booth

– “Solution-Focused Brief Therapy” by Mo Yee Lee

– “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy” by Claudia J. Dewane

Featured image credit: Michigan Celebrate Recovery Palooza by Sacred Heart. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post The impact of addictions and means of prevention, treatment, & recovery appeared first on OUPblog.

So not a form: Structure evolves from dramatic ideas

The sonata concept served some of the greatest imaginations in the history of music, but seriously it is, as I like to say to students, “so not a form.” Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Brahms were not in need of a standardized template, and in essence what has come to be called sonata form is more like courtroom procedure: a process that allows for an infinite variety of stories to be unfold, from a fender bender to vandalism to murder.

Musical form is the result of content, not the other way around. Teaching and understanding composition should be about the use of musical vocabulary to communicate a drama: the drama comes first, the form evolves.

Students who have been taught to think of music as a series of forms into which composers pour their ideas, will have difficulty composing. Instead of bringing the “form” to life, as they desire to do, they build a scaffold and hang a motif by the neck till dead. The remedy for this is to teach the process rather than emphasize the blueprint: dramatic narrative grows the structure.

The way we teach composition can inspire creativity or dull it. For example, here are three ways to give a composition assignment:

Imagine you are in the audience at a concert hall. A pianist comes on stage and plays a violent opening phrase. Then, the music builds in unpredictable thrilling rhythms and suddenly stops. This is followed by a quiet, reflective passage based on the opening, which then swiftly builds to an electrifying climax. You love the music! Write down what you can.

Imagine you are waiting for a train and suddenly a man violently pushes people around on the platform and then runs off and cannot be found. Someone who was hurt cries softly and then the violent man returns! Use this scenario to write a piano solo.

Write an ABA structure for piano solo that begins with a unison theme in forte; continue it with varied dynamics and shifting rhythmic patterns. Follow this with a piano contrasting B section and then a return of the A music with an appropriate coda.

Composer, author, and performer Bruce Adolphe. Photo courtesy of Barbara Luisi Photography, used with permission.

Composer, author, and performer Bruce Adolphe. Photo courtesy of Barbara Luisi Photography, used with permission.The three assignments above all describe ABA forms. The first is about imagining music as if you are an excited listener, a perspective that can set your imagination free.

The second version is dramatic scenario to be portrayed musically. The scenario happens to be in a form we could call ABA, but it is described only as a human drama.

The third version is a typical assignment, and rather dull — and is actually hard to do because one does not feel inspired or motivated. And, worst of all, it feels like a test. Learning about form is dull and meaningless if the way content drives form is missing from the method.

To make a personal statement about form, I will write here about my recently premiered piano concerto. In this work, which I composed in 2013 and which was first performed this past summer (10 July 2016) by the Italian pianist Carlo Grante with maestro Fabio Luisi conducting the Zürich Philharmonia, all my decisions about form were the result of one dramatic idea: the emotional conflicts and struggles that people who suffer from bipolar disorder must endure. It seemed to me that a piano concerto could embody opposing states of mind, with the solo piano representing the sufferer, and the orchestra taking a variety of roles: an amplification of the piano personality in the first movement; a sympathetic psychiatrist in the second movement; and in the third movement, society itself — fast-paced, indifferent, anonymous.

At no time in the process of composing this work, did I consider form as separate from the message of the drama. Certainly, this has been true for much of the music we love and study, and our teaching should reflect this reality. The slow movement of Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 4, for example, famously sets the powerful unison rhetoric of the string orchestra against the poetic, harmonically expressive piano soloist. As the soloist’s music unfolds, it tames the fury of the orchestra phrase by phrase. We could analyze the form, but it is the dramatic scenario that matters most. A clue that form evolves from ideas is that no two sonata “forms” by Haydn, Mozart, or Beethoven are actually the same. Each has its own way of subverting normative expectations, of challenging the very idea of conventionality. That’s because they are telling stories — wordless scenarios, but stories nonetheless.

In teaching sonata form or any supposedly fixed form — even from an historical perspective — it is essential to examine how form evolves from ideas, how music is driven by a unique narrative. Compositional technique is the ability to convey a drama or message in musical vocabulary and syntax. Music is the resonance of our lived experiences, the sonic shapes of our imagination; it is born of our personal histories and dreams, and then articulated as a drama played out in abstract architecture, awaiting performance by and for those who are ready to hear the message.

Featured image credit: “Music sheet” by Toshiyuki IMAI. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post So not a form: Structure evolves from dramatic ideas appeared first on OUPblog.

The earnest faith of a storyteller

Ang Lee, the two-time Academy Award-winning director, has noted that we should never underestimate the power of storytelling. Indeed, as a storyteller, Lee has shown through his films the potential of stories to connect people, to heal wounds, to drive change, and to reveal more about ourselves and the world. In particular, Lee has harnessed new technology for storytelling in movies such as Life of Pi (2012) and his upcoming feature film Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk (to be released on 11 November, 2016). It is therefore not surprising that Lee received the International Honor for Excellence Award—the highest honor given by the International Broadcasting Convention (IBC)—during the IBC Awards ceremony in Amsterdam this September. According to IBC CEO Michael Crimp, the award “goes to an individual who has made a significant and valuable contribution to the movie industry, combining technology with creativity to achieve remarkable ends.” Previous winners of this honor include James Cameron, who directed Avatar, and Peter Jackson, director of The Lord of the Rings series and The Hobbit films.

Lee’s 3-D, high-frame rate (HFR) film Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk premiered at the 2016 New York Film Festival and will be released by Sony in November. The film, adapted from Ben Fountain’s novel, is about an American war hero who embarks on a victory tour with his squad that includes a halftime show at a Thanksgiving Day football game. In this film, Lee and cinematographer John Toll used a 120-frame rate in an attempt to capture the soldier’s memories of his wartime experiences. The standard frame rate for movies is 24-frame rate per second or “FPS,” but directors sometimes depart from the standard for special purposes. However, this practice will change the nature of the image. For example, Peter Jackson previously experimented with a 48-frame rate, a technique known as “high frame rate,” in The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey (2012).

Nevertheless, critics such as Richard Corliss (Time magazine) and Scott Foundas (Village Voice) complained that the look of The Hobbit resembled that of video games or high-definition television. This dissatisfaction is mostly due to the fact that the sterile hyperrealism and deadly coldness of HFR’s high definition image disrupts the diegetic realism of normal cinematography. Although ultra-realism has aroused criticism among The Hobbit’s fans and critics, in Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk, Ang Lee appears to have delved deep into this technology in order to show the intensity of war and its emotional impact on his characters. As New York Film Festival Director, Kent Jones, said in a statement that, “Ang Lee has always gone deep into the nuances of the emotions between his characters, and that’s exactly what drove him to push cinema technology to new levels. It’s all about the faces, the smallest emotional shifts.”

The suspension of disbelief is often considered as an essential part of storytelling.

In this regard, one cannot help thinking of Lee’s earlier war film, Ride With The Devil (1999). By going beyond the dualisms associated with the American South, the film was an exception to the Civil War genre. This time, Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk can be considered as another exception to customary procedure, as Lee uses digital technology to experiment and play with “suspension of disbelief” of his viewers. Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk will allow us to see whether Lee is able to successfully engage his audiences in the “suspension of disbelief” with this new technology. The suspension of disbelief is often considered as an essential part of storytelling. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, the poet and literary critic, described the implicit contract in storytelling and aesthetic illusion as “that willing suspension of disbelief for the moment, which constitutes poetic faith.”

Like any creative endeavor, film is only successful to the extent that the audience offers this willing suspension. It is part of an unspoken agreement between a filmmaker and his/her viewers. Over the course of time, however, the adoption of digital technology has somewhat destabilized the “indexical” faith that spectators invested in the credibility of the image in relation to an imagined referent.

By presenting in ultra-realistic ways the realities of war and peace through a war hero’s eyes, Lee has put the issue of “faith,” the implicit contract between filmmaker and viewers, into question. Lee is likely to continue to use technological developments to push the limits of viewers’ deep-rooted knowledge about photographic image as well as cinematic language for larger purposes. Will Lee use this ultra-realistic technology to endorse or question the type of nationalist belief and storytelling that a drama of courage and heroism generally entails?

The film will give us a unique platform to understand and evaluate Lee’s earnest faith in creativity and storytelling.

Featured image credit: Screenshot of a scene from Ang Lee’s ‘Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk’. Fair Use via Sony/Tristar.

The post The earnest faith of a storyteller appeared first on OUPblog.

September 26, 2016

Putin and beyond: a Q&A on Russian politics

A version of this article originally appeared in the Manchester University Press Blog.

Russian politics has always been a fascinating subject around the globe. Exactly how politics works there, along with Putin’s vision for the country and the world at large is the source of constant debate. How does the country fit in with Europe? Everywhere else? Andrew Monaghan, author of The new politics of Russia explains just how the system works and what it means for Russia as well as the rest of the world.

How does Russian politics work?

Russian politics is characterized by long term continuity – many of the wider leadership team have held senior positions since the late 1990s. Within this continuity, there are two main elements. First is the importance of teamwork, a collective leadership built on networks that bring together the core leadership team with regional and administrative elites. This emphasizes loyalty and effectiveness, but also provides a degree of conformity and solidarity, submerging individual interests into the collective unit and binding individuals together. This also emphasizes burden sharing but also mutual obligation and protection. It also means that there are very few real reshuffles – senior figures are rarely fired. Second is the vertical of power, the “chain of command” through which power is created and plans implemented. This is often problematic, however, and is often somewhat dysfunctional – with the result that plans are not implemented, or are done so only partially or tardily, and responses to crises are slower and less effective than ideal. As a result, the leadership is obliged to resort to what is called “manual control” – in effect micro management – to ensure implementation.

How does Putin see Europe?

The Russian leadership’s view of Europe is ambiguous. On one hand, there are substantial cultural, political and economic ties between Russia and Europe. On the other, Putin has often criticized European liberal values, as espoused by the EU, suggesting that the Euro-Atlantic countries are rejecting their civilizational roots, and denying moral principles and all traditional entities. In 2013, for instance, he stated that the Euro-Atlantic path was taking a ‘direct path to degradation and primitivism resulting in a profound demographic and moral crisis’. Worse, he sees them to be trying to export this model, including to Russia – and thus he asserted that he would seek to protect Russia from this influence.

Who are Putin’s Allies?

When he came to power in 1999, Vladimir Putin was asked whom he trusted, and whose advice he took. He named Sergei Ivanov, Dmitri Medvedev, Nikolai Patrushev and Alexei Kudrin. Fifteen years later, these people still form Putin’s core group and dominate the strategic heights of Russian policy making, occupying respectively the key posts in the presidential administration, government and Russian national security council. There are other important figures, too, who can be considered to be allies, such as Igor Sechin, Gennadiy Timchenko, and Arkadiy Rotenberg, who are trusted to implement major projects.

What are Putin’s Goals?

Putin’s goals are two-fold. The first set of goals is to modernize Russia – in a hurry. These goals have been laid out in his May Decrees of 2012, in which he set out plans for modernizing many aspects of Russian life, from administration to health and from housing and utilities to military service conditions. This is an extensive, ambitious agenda with an implementation horizon of 2020. But it is essential, given the poor state of much Russian infrastructure and outdated administrative methods. The second set of goals is to ensure that Russia is an indispensable partner on the international stage, involved in all the major decisions about world affairs. An important aspect of this is to reinforce Russia’s position by building it up as an economic, security and political hub in Eurasia, particularly through creating and strengthening organisations such as the Collective Security Treaty Organisation and the Eurasian Economic Union.

What are the top five books on Russian politics?

Two of the most interesting books that provide detailed insight into Russian domestic politics while remaining accessible are Alena Ledeneva’s Can Russia Modernise? Sistema, Power Networks and Informal Governance, and Richard Sakwa’s The Crisis of Russian Democracy: The Dual State, Factionalism and the Medvedev Succession. One of the best new books about the history of Russian politics is Sheila Fitzpatrick’s On Stalin’s Team. The Years of Living Dangerously in Soviet Politics. Two of my favourite books about Russian political life come from an earlier era, however, and are Edward Crankshaw’s Russia and the Russians, and Peter Vigor’s The Soviet View of War, Peace and Neutrality, both of which contain much wisdom for understanding Russia, particularly about how different the world looks for Moscow – a crucially important aspect of understanding Russia today.

Image Credit: Moscow by Peggy und Marco Lachmann-Anke, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Putin and beyond: a Q&A on Russian politics appeared first on OUPblog.

Five questions for Oxford World’s Classics cover designer Alex Walker

Judging a book by its cover has turned out to be a necessity in life. We’ve all perused book shops and been seduced by a particularly intriguing cover–perhaps we have even been convinced to buy a book because of its cover. And, truly, there is no shame in that. It takes skill and artistry to craft a successful book cover, and that should be acknowledged. We sat down with one of Oxford University Press’ designers, Alex Walker, and asked him about the process that we often take for granted–or even deride in an idiom.

Where do you get your ideas for the images you use on the covers?

The design team considers a broad array of possible images, including paintings, photographs, and artwork: everything from intricate close-up photographs of period jewelry to patterns and fabric supplied by the V&A. When designing covers for books by prolific authors such as H.G. Wells and Jane Austen, we also try to link all titles by the same author together visually, so we draw inspiration from past books in the series. On the flip side, we also look at other books in the same area, previous titles, and competing titles, so that we can be sure to set each book apart from what has come before.

Can you take us through the process of designing a cover for a book in the Oxford World’s Classics (OWC) series?

Sure—to understand this process as easily as possible, imagine a pyramid. Our ethos, which is to make each design the best it can be, is the gravity that will hold our pyramid to the ground. With that in mind, let’s get some building blocks and lay out the first row in our pyramid by compiling as many possible cover images as we can think of. Working with editorial and picture research teams, we propose ways to represent the book in a single image; at this stage, there is no such thing as too many options.

The Way We Live Now

by Anthony Trollope

The Way We Live Now

by Anthony TrollopeTo move onto the second row of our pyramid, we need to begin to narrow down our choices. Our designers will compile all the relevant visuals into a single document that can be presented to multiple teams for review: editorial, production, and marketing all get a chance to express their opinions. There can never be too much feedback as we work together to reach a unified resolution. After initial thoughts and suggestions, any changes will be made or other avenues will be explored. Sometimes a certain design will already be favoured, e.g. artistic over photographic, so the photographic options will fall away as more artistic images get introduced to the fold and we investigate the initial idea further. As the pyramid grows, each row is shorter: possible designs fall away, leaving only our best options.

When we get down to a handful of visuals, anywhere between five and seven, we begin to play with the images a bit more, doing colour correction, making minor edits, and experimenting with interesting crops and layouts. At this stage, we might return to our colleagues in other departments for more feedback, to see what the group’s favourite is. Eventually, a single visual will be selected and we’ll have our cover, the triumphant capstone upon our pyramid.

Is it hard to design OWC covers? What difficulties do you encounter?

The OWC covers are often relatively straightforward to design. There is usually a wealth of visual material to consider over the brainstorming process, so if there’s a problem, it’s usually that we have too many ideas, not too few. We might also encounter obstacles to using some images: some will fall outside of our budget, some will take too long to arrive from the supplier in time for our schedules, and others look great on their own but don’t work well when on a front cover.

Do you have a favourite OWC cover that you’ve worked on?

War of the Worlds for the upcoming series of H. G. Wells titles is a personal favourite of mine. The picture research was really striking, and it was difficult selecting a favourite.

How did you become a book jacket designer? Do you have any for aspiring designers?

I chose to focus on design a lot at school so I have an A-level in Graphic Design and a degree in Illustration, and I chose to top that off with an MA in Publishing as well, so naturally I was drawn to book cover design. I would say a command of the software, a well of ideas and originality, and a platform to display these is worth a lot more though. To help myself get experience I would redesign my favourite book covers for my portfolio—I’m currently working on redesigns for the recently announced Man Booker Prize shortlist.

The post Five questions for Oxford World’s Classics cover designer Alex Walker appeared first on OUPblog.

Genome editing’s brave new world

“O wonder!/How many goodly creatures are there here!/ How beauteous mankind is!/ O brave new world,/ That has such people in’t!”

Shakespeare’s lines in The Tempest famously inspired Aldous Huxley’s novel Brave New World, first published in 1932. Huxley’s vision of the future has become a byword for the idea that attempts at genetic (and social) engineering are bound to go wrong. With its crude partitioning of society, by stunting human development before birth, and with its use of a drug – soma – to induce a false sense of happiness and suppress dissent, this was the opposite of a ‘beauteous’ world.

Brave New World was set in the year 2540, yet science in our own time has in many ways already progressed far beyond anything Huxley imagined. Genome editing now makes it possible to precisely modify the DNA of living cells of practically any species. Indeed, last year scientists in China genetically ‘corrected’ a mutated gene in a human embryo. Although there was no intention of implanting the modified embryos in a woman, this achievement ignited a debate about whether this was the start of a ‘slippery slope’ to use such an approach for clinical purposes, or even to enhance particular characteristics.

We still lack the ability described in Brave New World to nurture human foetuses outside the womb. But new advances in stem cell technology are making it possible to grow ‘organoids’ with similarities to human intestines, livers, eyes and even brains in culture; a viable artificial womb is not as far-fetched an idea as it might once have seemed.

There is no current pharmacological equivalent of Huxley’s soma. But optogenetics – which involves activating brain cells using laser light – has recently been used to erase memories or implant fresh ones, and even cure depression, at least in a genetically engineered mouse model. It is fair to speculate that optogenetics might one day be used to treat mental disorders such as depression, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder.

If gene editing, optogenetics, or generation of human organs from stem cells, are becoming much closer to scientific feasibility, is this a new world that we should be trying to avoid at all costs, given the possibility for misuse? Could gene editing be used to create a future world of genetically ‘perfection’, but only amongst the select few who can afford such an option for their children? And might optogenetics be used for sinister purposes such as brainwashing?

Pig and piglets on Black Knowl heath, New Forest by Jim Champion. CC-BY-SA 2.0 via geograph.

Pig and piglets on Black Knowl heath, New Forest by Jim Champion. CC-BY-SA 2.0 via geograph.In fact, compared to other branches of science such as mechanics, chemistry, or nuclear physics, which has given humanity such objects of destruction as the machine gun or the atom bomb, biotechnology remains a benign science. It is true that such a state of affairs could change given the relative ease and precision with which it is now possible to modify organisms. But it is important not to underestimate the challenges faced by anyone seeking to engineer a new, deadly pathogen for the purposes of terrorism. There would be major logistical challenges for anyone who would seek to create and use these as biological weapons without killing themselves in the process.

For agriculture, genome editing offers the possibility of making subtle modifications to the genetic make-up of crops or farm animals in a far more sophisticated fashion than was possible with past GM approaches. This could be used to introduce resistance to infection by viruses or boost nutritional content of resulting foodstuffs. But it also raises the question of whether such technology will be employed in a sustainable way to address the needs of ordinary people across the world or merely be used to boost the profits of giant corporations and ignore potential adverse effects on the environment.

In medicine, genome editing may soon be used to ‘correct’ genetic defects underlying disorders such as cystic fibrosis or muscular dystrophy, or to eliminate viruses like HIV from the cells of infected individuals. For the first time they offer the possibility of truly personalized medicine tailored to the individual. Yet as well as the many technical obstacles to be overcome to make this dream a reality, there are also many other issues to consider. Such medical intervention will be expensive, so how will we ensure that it is available to all who need it? We could potentially re-engineer wild mosquito populations so that they can no longer carry the deadly malaria parasite, but what are the possible unintended consequences to natural ecosystems of altering a wild species in this way?

Optogenetics might one day be used to treat disorders of the human mind. But could it also be employed for more sinister purposes, for instance to brainwash political opponents, or render a population sympathetic to a dictator’s will?

Is it realistic to think that genome editing might be used to ‘enhance’ human capability? Possibly not. The more we learn about genetic links to characteristics such as intelligence, the more complex this link appears. In addition, there is increasing evidence of similarities in brain processes involved in intellectual creativity and mental instability, so trying to engineer ‘genius’ could easily backfire. Finally, there is ample evidence that a whole host of different human talents, ranging from Einstein’s intellectual insights to Ronaldo’s footballing skills, are as much a product of nurture as of nature. So focusing on genetic transformation rather than improving the social environment that can nurture such talent may be misguided.

All of these are social as much as scientific questions. And such is the potential scope of the transformation of society that these new technologies makes possible that we need a society-wide debate about these issues. Yet if such a wider debate is to become a reality, it will need to overcome both the fear and distrust many people have about science, and of political elites and ‘experts’ in general. It will require a wider awareness of the science and the technologies and it will only happen when ordinary people feel they have a stake in the future applications of these technologies.

Featured image credit: Genetic resources12 by CIAT. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Genome editing’s brave new world appeared first on OUPblog.

A former child soldier prosecuted at the International Criminal Court

It’s easy to assume that only ‘evil’ people commit atrocity. And it’s equally easy to imagine the victims as ‘good’ or ‘innocent’. But the reality is far more complex. Many perpetrators are tragic. They may begin as victims. Victims, too, may victimize others. These victims are imperfect. Some victims survive – and some even thrive – because of harm they inflict.

The lines among victims and perpetrators tend to blur in the cataclysm of atrocity. What, then, to say about judgment, condemnation, punishment, and mercy?

When someone is harmed by another victim, how should that someone speak of the harm? Does the tragic nature of the perpetrator dull the pain? Or might it worsen it?

In recent research, I explore how to approach the pain that victims inflict upon themselves and on other victims. I begin historically with one of the most insidious aspects of the Nazi Final Solution – the deployment of members of the persecuted group to further genocide: Jewish Kapos (heads of barracks and work groups) in the concentration camps and Jewish police and councils in the ghettos. I end with the current work of the International Criminal Court (ICC).

The ICC entered into force in 2002 to prosecute those enemies of humankind who bear the greatest responsibility for the most serious crimes of concern to us all. The ICC channels the outrage of the international community. Its point is retribution and, also, deterrence; its goal is to end impunity.

The ICC – in its solemnity, set in The Hague, the epicenter of global justice – is about to further its mandate by prosecuting a former child soldier from northern Uganda, now a 40-something year old man, named Dominic Ongwen.

Ongwen was abducted into the rebel Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) at the age of nine. Headed then and now by Joseph Kony, the LRA – largely depleted by Uganda’s policy to amnesty its membership – is implicated in decades of systemic atrocities in northern Uganda. Ongwen was abducted by LRA fighters while walking home from school. Unlike some of his other classmates, he was not wiry or wily enough to avoid the kidnappers.

The ICC channels the outrage of the international community. Its point is retribution and, also, deterrence; its goal is to end impunity.

Ongwen was brutalized. He came of age in the LRA. He however proved – in his own words – to be ‘a very sharp recruit’. He demonstrated his wiriness and wiliness. He rose through the ranks. He became a Brigadier Commander. While it is unclear exactly what ‘rank’ means in the LRA, what is clear is that Ongwen was frequently promoted. He was feared. He lorded over others.

Kony’s relationship with Ongwen was edgy. Kony was suspicious of Ongwen. And Ongwen feared for his own life. Ongwen wanted out of the LRA. Kony suspected as much. Kony had Ongwen imprisoned and tortured in Sudan. Ongwen escaped barefoot in January 2015. He surrendered to U.S. Special Forces and was promptly transferred to the ICC.

In March 2016, an ICC Pre-Trial Chamber confirmed charges against Ongwen. He is the only LRA accused in custody. The rest are dead or – like Kony – at large. The charges against Ongwen are many in number and horrific in content, including recently added allegations of gruesome sexual and gender-based violence.

Ongwen is also charged with crimes that he himself suffered: unlawful recruitment of children into armed groups and cruel treatment (both war crimes), and enslavement as a crime against humanity. On this note, then, Ongwen is unique among ICC defendants.

Does it matter that Ongwen’s point of entry into the LRA began as an abducted tormented boy? Should it? It is relevant that Ongwen came of age in the LRA? That Kony nearly executed him on several occasions, but didn’t only because Ongwen’s sister was among Kony’s favorite wives?

Criminal trials are angular and austere. They play an adversarial zero-sum game. Prosecutors seek to convict. The Defense pushes to acquit. Both sides thereby present contrasting narratives. It is their job to do so.

Great pain can be caused by morally ambiguous people.

So the Defense emphasizes that Ongwen should be entitled to a full duress defense that would void the charges against him. For the defense, then, Ongwen is forever a child in mind, spirit, and agency. His victims have to accept that, regardless of how bitter a pill that is to swallow.

For the Prosecution, Ongwen seems never to have been a child, let alone a child socialized in the LRA. He is taken up as an adult, since the ICC only has jurisdiction over adults, as if he were born as an adult. On 6 September 2016, the ICC Chief Prosecutor submitted her Pre-Trial Brief, which details all the charges and Ongwen’s position of authority. This 285 page long document makes no mention whatsoever of Ongwen’s background. While it extensively unpacks hardships endured by child soldiers in Ongwen’s brigade, and the brutally coercive nature of the LRA, it is totally (and ironically) silent with regards to the brutalities and coercion that Ongwen himself had endured.

So far, the Prosecution has had the better of it. The Pre-Trial Chamber rejected the duress arguments at the confirmation of charges hearing. The Pre-Trial Chamber elided Ongwen’s status as former child soldier. It’s as if he ceded that status, or forfeited it. Ongwen’s victimhood is contingent. He lost it because of what he went on to do.

To be sure, these arguments will reappear, under different evidentiary standards and for different purposes (including sentencing), at trial.

The accuracy of the historical record is not well-served by these dueling essentialisms. Any comfort they achieve is anodyne. Many child soldiers demonstrate mercy and kindness. Other child soldiers can do wretched things as children. Former child soldiers can do horrific things as adults. And adults who do horrific things may begin on that path when they are abducted and tortured as a shy child. Reductionist zero-sum games do not do justice to the realities of child soldiering.

Great pain can be caused by morally ambiguous people.

Some Kapos – much lower down on the chain of authority than Ongwen – caused great pain. Some of the most powerful literature of the Holocaust – the work of Primo Levi, Imre Kertéesz, and Viktor Frankl – is animated by stories of connivance, betrayal, and injury as inflicted by and among the prisoners. Israel prosecuted forty Kapos as collaborators in the 1950s and 1960s. These trials however struggled to narrate these stories. Criminal law lacked the vocabulary or finesse. To acquit was as unfulfilling, and incomplete, as to convict and, certainly, as to sentence.

So instead of casting Ongwen as monstrously evil – the prosecutor’s impetus – or as innocently helpless – the defense’s impulse – another narrative goal could be to uncork the conundrum that mass atrocity involves the handiwork of people who are neither too purposeful not too purposeless. Without this handiwork, after all, atrocity would never become massive in scope or reach.

Is a criminal trial up to this challenge?

Featured image credit: Courtroom One Gavel. Public Domain via Flickr.

The post A former child soldier prosecuted at the International Criminal Court appeared first on OUPblog.

September 25, 2016

Brexit and Article 50 negotiations: What it would take to strike a deal

In the end, the decision for the UK to formally withdraw its membership of the European Union passed with a reasonably comfortable majority in excess of 1¼ million votes. Every one of the 17.4 million people who voted Leave would have had their own reason for wanting to break with the status quo. However, not one of them had any idea as to what they were voting for next. It is one of the idiosyncrasies of an all-or-nothing referendum that you can campaign wholeheartedly against the reproduction of existing conditions whilst sidestepping altogether the responsibility of saying what you would put in their place.

And so we arrive at where we are now, but where that is precisely is anyone’s guess. The full implications of Brexit will not be known until after Article 50 has been formally triggered, the UK announces the role it envisions the EU playing in its new mode of insertion into economic globalisation, and the European Commission and European Council of Ministers confirm whether they find that role acceptable.

In the meantime Theresa May and her economic ministers have tried to govern through reassurance. They have been repeatedly signalling to the rest of the world that the UK remains open for business and that the existing outward-facing orientation of the economy will not change. Indeed, on strictly economic matters they are hinting that they will be asking for something approaching the status quo mark two. This is what the Government thinks powerful economic interests want to hear. British businesses that trade overseas certainly do not want to relinquish their current priority access to the EU’s half a billion consumers; many foreign direct investors only set up in the UK in the first place because of the right of free entry into the European single market; and UK-based banks want to retain the ‘passport’ rights that allow them to operate without restriction across the EU. If they are all to get what they want out of the Article 50 negotiations, then the globalisation of the UK economy in the post-EU era will need to look remarkably similar to the globalisation of the UK economy prior to 23rd June. Yet this would come as a mighty disappointment to many Brexit voters who have felt let down by the preceding elite consensus in favour of a globalisation that they have experienced as accelerating economic insecurity.

It therefore appears that the route to a deal passes through something that proved impossible during the referendum campaign itself. The May Government needs to know what it wants to ask for before invoking Article 50, but irrespective of what that turns out to be it seems to require reconciling fundamentally irreconcilable positions. The UK is currently economically divided to such an extent that the image of a gaping chasm is hard to dismiss. There are those who do so badly out of the current mode of insertion of the UK economy into globalisation that the EU referendum became their sole means of crying, ‘Enough!’ There are also those who do so well out of the existing state of affairs that they are likely to simply walk away from the UK if things change too much. The choice for the May Government is either to ignore the claims of the former group, which would leave it vulnerable to the accusation of acting as if the referendum had never happened, or to ignore the claims of the latter group, to which it is closely aligned politically and otherwise lionises as the country’s indispensable ‘wealth-creators.’

EU United Kingdom problem by Elionas2. Public domain via Pixabay.

EU United Kingdom problem by Elionas2. Public domain via Pixabay.It is therefore highly unlikely that everyone will receive the outcome that they think reflects what they voted for on 23rd June. Perhaps this is merely the nature of an all-or-nothing referendum, but it does back the May Government into a corner. It is inconceivable that it will present as its favoured negotiating position something that does not feel like a definitive Brexit, because the Prime Minister will be eager to keep off her back the unholy trinity of UKIP nativists, her own rowdily anti-European backbenchers, and the country’s right-wing media tycoons. In relation to continued access to the European single market, though, she will hope that she can pull off the smoke-and-mirrors trick of negotiating something that feels like a definitive Brexit but in practice does not act like it.

However, the omens are not promising. Access to the single market that replicates an EU member’s terms of entry comes with significant costs attached.

In the most straightforward sense it is necessary to pay what might be seen as a subscription fee for those terms. Current precedent suggests that the fee will be almost as high in per capita terms as the contributions that the UK has recently been making to the EU budget as a full member state that has a guaranteed seat at every decision-making table. As so much fuss was made during the referendum campaign about how much money Brussels siphons off from London, the subscription fee for full access to the single market is likely to be a deal breaker on its own. This is before anyone from the UK Government begins to talk to Commission officials about finding a common ground on single market access, which the latter have already made clear will entail accepting the existing treaty obligation to respect the free movement of people. They have appointed to the role of chief EU negotiator Michel Barnier, a two-time Commissioner with the reputation throughout Whitehall as a hard-core federalist. This will ensure that treaty obligations will not be up for discussion from the Commission’s side. At the same time, however, May has already signalled that she is interpreting the referendum result as a decisive rejection of the principle of the free movement of people.

It thus becomes prudent to contemplate that there might be no available compromise between competing visions about the preferred way ahead.

Featured image credit: Chess king match by SteenJepsen. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Brexit and Article 50 negotiations: What it would take to strike a deal appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers