Oxford University Press's Blog, page 464

September 17, 2016

Britain, Ireland, and their Union 1800-1921

Historians of both Britain and Ireland have too often adopted a blinkered approach in which their countries have been envisaged as somehow divorced from the continent in which they are geographically placed. If America and the Empire get an occasional mention, Europe as a whole has largely been ignored. Of course the British-Irish relationship had (and has) its peculiarities. For one thing its long history going back to the Norman invasion of Ireland in 1169 has generated influences and feelings of a distinct and unique kind: long familiarity underpinned by both antagonism and (at times) a type of weary and indeed wary acceptance. The word most commonly employed in analyzing the relationship is that of ‘colonialism’ which — rightly or wrongly — tends to carry with it intimations not only of cultural and political but also of geographical distance when in fact Dublin is only some 68 miles across the Irish Sea from Holyhead in Wales. Thus, when in 1800 — after the bitter Irish Rebellion of 1798 — the Act of Union between Britain and Ireland was enacted, this marked not only the introduction of a closer relationship but the culmination of centuries of conflict and accommodation on both sides.

What might shed greater light upon the Anglo-Irish relationship is an examination of similar situations elsewhere in Europe itself. Indeed, the oscillations under the Union on the part of British ministers between, on the one hand, policies designed to integrate and assimilate Ireland more closely into British political and cultural norms and, on the other, to acknowledge (within certain limits) Irish distinctiveness, parallel actions taken elsewhere in Europe by politicians similarly obliged to deal with complex relationship between dominant economic and political ‘cores’ and outlying peripheries. Indeed, in this matter the Anglo-Irish relationship was — in international terms — very far from unique, something which few British or Irish leaders seem to have realized.

William Gladstone, 1861. Photo by John Jabez Edwin Mayall. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

William Gladstone, 1861. Photo by John Jabez Edwin Mayall. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Gladstone was one of the few exceptions, having experienced a kind of foreshadowing of his later Irish involvement when acting in 1858-9 as Special Commissioner to the Ionian Islands off the west coast of Greece and since 1815 a British protectorate. In 1885, he lectured cabinet colleagues about the relevance for the Irish case of “the prolonged experience of Norway (I might perhaps mention Finland) and the altogether new experiencer of Austria-Hungary” — all of them examples of core-periphery relations with strong Irish parallels.

Finland, which had come under Russian rule in 1809, was, like Ireland, generating strong narratives about history, landscape, and people that together helped to transform abstract concepts of the nation into concrete visual, textual, and polemical articulations of national consciousness. Tsarist Russia, though at first supportive of Finnish cultural and linguistic particularism as furnishing a wedge between the Finns and their former Swedish overlords, shifted to a policy of coercive Russification towards the end of the nineteenth century, something with clear resonances so far as Britain and Ireland were concerned. Norway, however, after experiencing early attempts by Sweden to tighten central control, began to outrun Finland in the matter of autonomy before achieving full independence in 1905, while the broadly analogous case of Denmark and Iceland — inevitably shaped by the enormous distances involved — also witnessed movement from assimilation to greater autonomy as time went on. Indeed, Iceland’s progress did not go unnoticed among supporters of Irish nationalism, some of whom looked to its successes as providing Ireland with encouragement and Britain with a pattern to follow.

If the Nordic cases cast revealing light upon the governmental situation created by the Irish Act of Union of 1800, developments elsewhere in Europe — in Austro-Hungary, in Italy, in Spain, in Switzerland, in the creation of an independent Belgium, and in the unification of Germany — also possess much greater relevance to the Anglo-Irish case than has generally been acknowledged. Thus Cavour’s lordly attitude to Sicily (whose inhabitants, he claimed, spoke “Arabic”) echoed views commonly held in Whitehall’s corridors of power so far as Ireland was concerned. Indeed Cavour never seems to have traveled further south than Florence, just as Disraeli, for example, never crossed the Irish Sea.

Because a common feature to many of these core-periphery relationships is to be found in the fact that ideas of assimilation and differentiation underlay much of the thinking involved a more conscious ‘placing’ of the Anglo-Irish connection into a wider European framework might well prove illuminating in new and exciting ways.

Featured image credit: “Connemara” by Fred Bigio. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Britain, Ireland, and their Union 1800-1921 appeared first on OUPblog.

America’s nuclear strategy: core obligations for our next president

Plainly, whoever is elected president in November, his or her most urgent obligations will center on American national security. In turn, this will mean an utterly primary emphasis on nuclear strategy. Moreover, concerning such specific primacy, there can be no plausible or compelling counter-arguments.

In world politics, some truths are clearly unassailable. For one, nuclear strategy is a “game” that pertinent world leaders must play, whether they like it, or not. The next US president can choose to learn this inherently complex game purposefully and skillfully, or inattentively and inexpertly. Either way, he or she will have to take part.

Should our next president opt for the more patently sensible choice of learning, he or she will then need to move significantly beyond their predecessor’s earlier search for global denuclearization (President Barack Obama’s expressly preferred “world free of nuclear weapons”), and move instead toward a meaningfully realistic plan to (1) control nuclear proliferation; and (2) improve America’s nuclear posture. Under no circumstances, should any sane and sensible US president ever recommend the further proliferation of nuclear weapons, a starkly confused endorsement that would, on its face, represent the reductio ad absurdum of all possible presidential misjudgments.

Intellectually, the proliferation issue has already been dealt with by competent nuclear strategists for decades, authentic thinkers who well understand that any alleged benefits of nuclear spread must generally be overridden by expectedly staggering costs. There is a single prominent exception to the anti-proliferation argument. Israel, an already nuclear power that is “ambiguous” or undeclared, requires its national nuclear deterrent merely to survive.

At the start of the Cold War, the United States first began to codify vital orientations to nuclear deterrence and nuclear war. At that time, the world was tightly bipolar, and the obvious enemy was the Soviet Union. Tempered by a shared knowledge of the horror that had finally ceased in 1945, each superpower had then understood a conspicuously core need for cooperation (or at least technical and diplomatic coordination), as well as conflict preparedness.

With the start of the nuclear age, American national security was premised on seemingly primal threats of “massive retaliation.” Over time, especially during the Kennedy years, this meticulously calculated policy was softened by more subtle and nuanced threats of “flexible response.” Along the way, moreover, a coherent and generalized American strategic doctrine was crafted to accommodate every conceivable kind of adversary and enemy encounter.

Systematic and historically grounded, this doctrine was developed self-consciously to evolve prudently, and usually in carefully considered increments. We are now witnessing the start of a second cold war. This time, however, there will likely be more points of convergent interest and cooperation between Washington and Moscow. For example, in view of our mutual concern for controlling Jihadist terrorism, “Cold War II” could eventually represent an improved context for identifying overlapping strategic interests.

At this moment, both Mrs. Clinton and Mr. Trump should be thinking about already-nuclear North Korea and Pakistan, and about a still prospectively nuclear Iran. However well-intentioned, the July 2015 Vienna Pact on Iranian nuclear weapons can never reasonably be expected to succeed. Jurisprudentially, it even subverts the pre-existing Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (1968), and still earlier expectations of the Genocide Convention (1948). According to the latter, no state that encourages “incitement to genocide” can ever be allowed to go unsanctioned.

Nuclear strategy is a “game” that pertinent world leaders must play, whether they like it, or not. The next US president can choose to learn this inherently complex game purposefully and skillfully, or inattentively and inexpertly. Either way, he or she will have to take part.

Also important for Mrs. Clinton and Mr. Trump to understand will be various possible interactions or synergies between our major adversaries. North Korea and Iran, for example, both with documented ties to China, Syria, and Russia, have maintained a long-term and consequential strategic relationship. In managing such strategic threats, will Cold War II help us or hurt us? These will represent fundamentally intellectual questions, not political ones, and will therefore need to be addressed at suitably analytic levels.

Of course, for our next president, strategic policy will also have to deal with an assortment of sub-national threats of WMD terrorism. Until now, certain insurgent enemies were able to confront the United States with serious threats in assorted theatres of conflict, but they were also never really capable of posing a catastrophic and correlative hazard to the American homeland. Now, however, with the steadily expanding prospect of WMD-equipped terrorist enemies – possibly, in the future, even well-armed nuclear terrorists – we could sometime have to face a strategic situation that is both prospectively dire, and historically sui generis.

To face such an unprecedented and portentous situation, our next president will need to be suitably “armed” with antecedent nuclear doctrine and policies. By definition, such doctrine and policies should never be “seat of the pants” reactions to singular or ad hoc threats. Rather, because, in science, generality is a trait of all serious meaning, they will have to be shaped according to broad categories of strategic threat to the United States. In the absence of such previously worked-out categories, American responses are almost sure to be inadequate or worse.

From the start, all US strategic policy has be founded upon an underlying assumption of rationality. In other words, we have always presumed that our enemies, both states and terrorists, will inevitably value their own continued survival more highly than any other preference, or combination of preferences. But, as our next president must be made to understand, this core assumption can no longer be taken for granted.

Ultimately, US nuclear doctrine must also recognize certain critical connections between law and strategy. From the standpoint of international law, certain expressions of preemption or defensive first strikes are known formally as anticipatory self-defense. Anticipating possible enemy irrationality, when would such protective military actions be required to safeguard the American homeland from diverse forms of WMD attack? This is an important question to be considered by our next president.

Recalling, also, that international law is part of the law of the United States – a recollection that has thus far eluded Mr. Trump – most notably at Article 6 of the Constitution (the “Supremacy Clause”), and at a 1900 Supreme Court case (the Pacquete Habana) how could anticipatory military defense actions be rendered compatible with both conventional and customary legal obligations? This is another question that will have to be raised.

Our next president must understand that any proposed American strategic doctrine will need to consider and reconsider certain key issues of nuclear targeting. The relevant operational issues here will concern vital differences between the targeting of enemy civilians and cities (so-called “counter value” targeting), and targeting of enemy military assets and infrastructures (so-called “counterforce” targeting).

At first glance, any such partially-resurrected targeting doctrine could sound barbarous or inhumane, but if the alternative were less credible US nuclear deterrence, certain explicit codifications of counter value might still become the best way to prevent millions of American deaths from nuclear war and/or nuclear terrorism. Of course, neither preemption nor counter value targeting could ever guarantee absolute security for the United States and its allies, but it is nonetheless imperative that our candidates put serious strategic thinkers to work on these and other critically-related nuclear issues.

The very first time that our next president will have to face a nuclear crisis, our national response should flow seamlessly from a broader and previously calibrated US strategic doctrine. It follows that both Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton should already be thinking carefully about how this complex doctrine can best be shaped and employed.

Featured image credit: White house president USA by christoph-mueller. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post America’s nuclear strategy: core obligations for our next president appeared first on OUPblog.

Publish and be cited! Impact Factors, Open Access, and the plight of peer review

This coming week (19-25 September) is Peer Review Week 2016, an international initiative that celebrates the essential and often undervalued activity of academic peer review. Launched last year by Sense about Science, ORCID, ScienceOpen and Wiley, Peer Review Week follows in the wake of two open letters from the academic community on the issue of peer review recognition. The first was from early career researchers in the UK to the Higher Education Funding Council for England in July, and the second from Australian academics to the Australian Research Council two years later.

Now in its second year, Peer Review Week is focusing on the issue of Peer Review recognition, its current coordinating committee including additional organisations such as AAAS, COPE, eLife, and the Royal Society and the Federation of European Microbiological Societies (FEMS). This focus stems from the fact that while perceived as important, peer review is often regarded as a secondary activity to publication by decision makers across the Higher Education and funding sectors. This is something that David Colquhoun, Professor of Pharmacology at the UK’s University College London, firmly attributed to the ‘publish or perish’ culture imposed by “research funders and senior people in universities” some years ago.

It’s a view echoed in the preliminary findings of one of two new surveys on peer review, the first released by FEMS as part of this week’s activities, which reveals that, at least among the global microbiology community, authors subject to peer review perceive greater professional development benefits from the process than do the people carrying out the reviews. And what lies at the heart of this – and is clear from Colquhoun’s comments – is the influence of Eugene Garfield’s infamous journal “Impact Factor”. For in practice it is not so much publications, as citations, that are held in such high regard. Indeed without citations, says Nature blog’s Richard van Noorden, a publication may be regarded as “practically useless”.

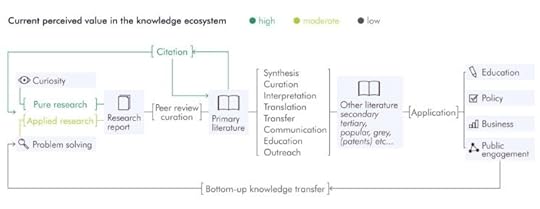

Perceived values in the knowledge ecosystem. Cath Cotton, Laura Bowater, Richard Bowater. Image used with authors’ permission.

Perceived values in the knowledge ecosystem. Cath Cotton, Laura Bowater, Richard Bowater. Image used with authors’ permission.This view that work must be cited by scientific authors in order to be of social or economic value is at odds with the thinking of the UK and Dutch governments, the European Union, Max Planck and other proponents of Open Access publishing who are keen to ensure that primary literature reaches “the taxpayer”, entrepreneurs, and innovators. The anticipation is that wider access will lead to greater innovation – specifically in relation to the creation of jobs and services, and the provision of solutions to problems. This conflicts with the traditional model of attributing academic value to citations in that while these newly targeted end-users might derive benefit from accessing the primary literature, they do not engage in the activity of writing – and therefore citing – scientific articles.

But whether you’re trying to attract citation by academics or translation by innovators, scientific quality control is key. Indeed, Peder Olesen Larsen and Markus von Ins would argue that what makes a scientific publication a serious one, is not citation but peer review. This latter can have several functions, including assessing “sound science” as practiced by Open Access mega journals like PLOS One and Springer Plus, established to publish the findings of any research that adheres to given methodological standards. The thinking behind this is several-fold, but includes avoiding duplicating unproductive lines of inquiry, and cascading “out of scope” articles from specialist to broad-scope journals, to circumvent multiple time-consuming rounds of review. In other forms of peer review, scientific content – not just science per se – may be assessed for a particular function, including the likelihood of getting cited.

Given that increasing investment in science globally means ever greater scientific outputs (particularly across the fast-growing knowledge economies of Asia and Latin America), all forms of peer review are currently facing limited capacity. Seeking practical solutions to some of these concerns, a second survey published this week, this time conducted by PRE (Peer Review Evaluation), a programme of the AAAS, looks at how new developments in peer review might be delivered. For example, an earlier survey from Wiley-Blackwell showed that 77% of researchers expressed an interest in peer review training. The PRE survey takes this a step further, exploring how such training might be implemented. What would it consist of? Who would pay for it? And how would it be delivered?

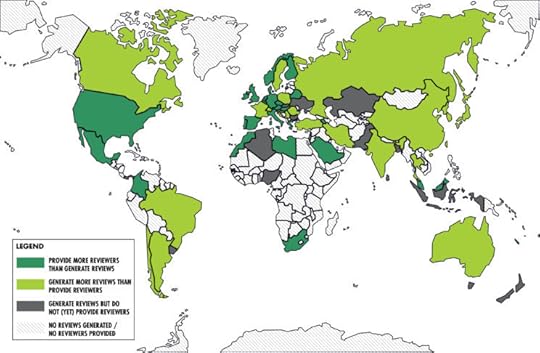

Countries from which peer reviewers originate. Cath Cotton, Laura Bowater, Richard Bowater. Image used with authors’ permission.

Countries from which peer reviewers originate. Cath Cotton, Laura Bowater, Richard Bowater. Image used with authors’ permission.Such training would certainly have the potential to increase the international reviewer pool, effectively spreading the load. But institutions that do not recognize peer review as a “core” academic activity might be reluctant to invest in training their staff or have them provide reviews, as part of their job. Australian researchers had a good answer to this back in 2014, as expressed in their open letter to the Australian Research Council requesting that peer review targets be set alongside existing publication targets (see Meadows 2015b). It’s a simple enough ask in principle, and would have the immediate effect of addressing the balance between peer review and publication. And while it might sound ambitious in practice, this – led by leading research funders and a handful of national governments – is exactly what happened with Open Access.

Our hope is that by building on the events and discussion around Peer Review Week, this critical issue will equally start to get more meaningful attention, and to push peer review up the science policy agenda.

You can join in the conversation about Peer Review Week 2016 via the hashtags #PeerRevWk16 and #RecognizeReview, and by following @OxfordJournals and @FEMSTweets on Twitter.

Featured image credit: Writing-hands by Senlay. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Publish and be cited! Impact Factors, Open Access, and the plight of peer review appeared first on OUPblog.

Moral responsibilities when waging war

In his long-awaited report on the circumstances surrounding the United Kingdom’s decision to join forces with the United States and invade Iraq in 2003, Sir John Chilcot lists a number of failings on the part of the then-British leadership. In particular, he pays close attention to the aftermath of the war and, more specifically, to the absence of proper post-invasion planning. With devastatingly forensic precision, he notes that Prime Minister Tony Blair, the relevant Cabinet Ministers and senior officials (a) were fully aware of the likelihood of post-invasion internecine violence, of the need to reconstruct the country, and of the importance of a properly constituted interim civil administration; (b) were aware of the deficiencies in the USA’s post invasion plans; (c) did not undertake proper risk assessments or consider various post-invasion options.

The claim that the Coalition failed to prepare for a post-Saddam Hussein Iraq, and that its failure is a moral failure as much as a political failure, is not new. It has its roots in the deeper thought that a political actor is not morally entitled to wage war unless it does so for the sake of securing peace. If it goes to war without that ultimate aim in mind, and thus without due consideration to the aftermath of the conflict, it is guilty of waging an unjust war.

The claim that war is morally justified only if it delivers peace elicits a number of difficult questions, not least of which what counts as peace. The mere absence of violence will not do, of course, for this would justify going to war with the aim of wholly annihilating or subjugating the enemy to the point where it simply could no longer react with violence. Rather, the aim of war must be a just peace.

But what, then, counts as a just peace? In the just war tradition, the norms which regulate peace — or just post bellum — are the following: victorious belligerents must aim to restore the political sovereignty and territorial integrity of their defeated enemy; some form of reparation for war-time wrongdoings should be paid to victims; assistance should be given to the defeated enemy and its civilian population towards the reconstruction of their country; and war criminals should be put on trial.

Once unpacked, however, those norms raise more problems for, than offer solutions to, the conundrum of peace after war. Thus, restoring political sovereignty and territorial integrity might require the deployment of peacekeeping forces in the short term; indeed it might require a military occupation, followed by regime change under the auspices of international organisations, in order for the vanquished people to be properly sovereign. Yet the presence of foreign troops on that people’s soil, together with invasive modes of top-down governance, stand in tension with the value of political self-determination which they aim to foster.

Saddam Statue by unknown U.S. military or Department of Defense employee. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Saddam Statue by unknown U.S. military or Department of Defense employee. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Consider next the requirement to offer reparations to victims of war crimes. Who should pay? War criminals, presumably, and those who supported them in their endeavours. Except that, more often than not, they are dead, or cannot be identified in the chaos of war, or are too impoverished to pay up. The easiest solution would be for a belligerent community collectively to take responsibility for the crimes which its citizens and soldiers did, on its behalf, during the war. Except that, more often than not, war crimes are committed by both sides — which further complicates the calculation by which the reparations bill is settled.

The requirement to assist in the reconstruction of destroyed communities, for its part, is not devoid of complications either. The Marshall Plan, whereby the United States disgorged billions of dollars towards the reconstruction of Europe after the Second World War, is the best known example of this policy. Of course, it was in the interest of the United States that European Western democracies should be strong enough to act as a bulwark against Communism. Would we want to say, however, that the United States were under a moral duty towards the Germans who had supported or at least acquiesced in Nazism and its horrors in their millions, to reconstruct their cities, renew their industry, rebuild their bridges? And even if we would want to say that, were the United States under a moral duty to prioritise helping those Germans over, for example, providing material help to the wretchedly destitute populations of sub-Saharan Africa? There is a sense of course in which the contrast between the Marshall Plan and overseas development avant l’heure is anachronistic. The main point remains, however: it is not obvious that reconstruction duties are owed to those who are in large part responsible for their suffering; and even if they are, it may not be possible to fulfill both post-war duties and duties to those who were not in any way connected to the conflict in the first instance.

Consider now the requirement that war criminals be punished. What if they threaten to derail the peace process? Should we, in this case, accede to giving them an amnesty, at the cost of honoring their victims? What if there simply are too many war criminals for the judicial system to handle? Should we, in this case, resort to less formal, less Western, punitive institutions and give greater role to more traditional fora, as was done in Rwanda after the genocide? In fact, in the aftermath of civil conflicts in particular, when erstwhile enemies have no choice but to live side by side, reconciliation rather than, or at least alongside, punishment might be morally preferable — to the extent that its constitutive institutions and practices, such as truth commissions and official apologies help to foster trust and rekindle hope.

Finally, there is an important dimension to peace after war which we tend to overlook, at least in the relevant philosophical writings, and yet which is crucial, it seems to me, to the restoration, or instauration, of good relationships between belligerents —namely, the commemoration of the conflict and of those who suffered and died in it. When we erect monuments and crosses for combatants who died in war, lay wreaths in their memory, put up commemorative plaques for murdered civilians, turn battlefields into places to visit and build military museums, we typically mean to remember something about ‘us’, as distinct from ‘them’, our erstwhile enemy. In so doing, we run the risk of aggrandising our suffering and minimising theirs. Therein perhaps lies the greatest danger for peace.

Featured image: Stone monument by MichaelGaida. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Moral responsibilities when waging war appeared first on OUPblog.

September 16, 2016

A reading list of Mexican history and culture

On 16 September 1810, a priest named Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla delivered a proclamation in the small town of Dolores that urged the Mexican people to challenge Spanish imperial rule, marking the start of the Mexican War of Independence. To commemorate Mexican Independence Day and the “Grito de Dolores,” we’ve compiled a reading list of articles from the that explores the rich history, culture, and traditions of the Mexican people.

1. by Jeffrey M. Pilcher

Mexican cuisine is often considered to be a mestizo fusion of indigenous and Spanish foods, but this mixture did not simply happen by accident; it required the labor, imagination, and sensory appreciation of both native and immigrant cooks. Jeffrey Pilcher examines the fusion that defines Mexican national identity. He explores how the tastes of the culture changed with the rise of industrial agriculture, from bitterness toward sweetness as the predominant sensory experience.

2. by María Teresa Fernández Aceves

From the War of Independence until the recognition of female suffrage in Mexico in 1953, the women of Guadalajara witnessed different forms of activism that touched upon national and local issues, causing them to take to the streets in order to defend their families, their neighborhoods, and their communities – which were their political and religious ideals. Fernández Aceves’ article looks at how the women of Guadalajara upended traditional notions of femininity within the Catholic Church, the liberal state of the 19th century, and the public square after the revolution (1920–1940).

3. by Christoph Rosenmüller

How did indigenous cultures in colonial Mexico change with the introduction of Spanish missionaries and Spanish rule? How did such communities continue their traditions and adapt to coexist with the Spaniards? Christoph Rosenmüller explores these questions in this article addressing the period after the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs.

“Mexico City” by Blok 70. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

“Mexico City” by Blok 70. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.4. by Jürgen Buchenau

The Mexican Revolution was the first major social revolution of the 20th century. Its causes included the authoritarian rule of Dictator Porfirio Díaz, the seizure of millions of acres of indigenous village lands by wealthy hacendados and foreign investors, and the growing divide between the rich and the poor. Jürgen Buchenau explores the effects of the revolution from the insurrection and civil war (1910–1917); reconstruction (1917–1929); and institutionalization (1929–1946).

5. by Susie S. Porter

From la Adelita to the suffragette, from la chica moderna to the factory girl dressed in red shirt and black skirt—the colors of the anarchist—women’s mobilization in the midst of the Mexican Revolution was, to a large degree, rooted in their workforce participation. Susie S. Porter examines how women changed the conversation about the rights of women—single or married, mothers or not, and regardless of personal beliefs or sexual morality—to involve issues of dignity at work, and

the right to combine a working life with other activities that informed women’s lives and

fulfilled their passions.

6. by Elena Jackson Albarrán

The family structure, both nuclear and extended, often functions as a microcosm of the institutional organization of power. Historian Soledad Loaeza has noted that this comparison goes beyond a facile metaphorical observation; within the family, individuals experience their first contact with authority, and they first begin to construct their social and political identities within the context of this power rubric. Elena Jackson Albarrán examines how the shape, function, and social meaning of the Mexican family changed alongside its relationship to the state, the Catholic Church, and popularly held beliefs and customs over the past 140 years and more.

7. by Roderic Ai Camp

Public opinion polls played a critical role in Mexico’s democratic political transition during the 1980s and 1990s. It informed ordinary Mexicans about how their peers viewed candidates and important policy issues, while simultaneously allowing citizens, for the first time, to assess a potential candidate’s likelihood of winning an election before the vote and also confirm actual election outcomes through exit polls. Roderic Ai Camp discusses how polling data reveal changing social, religious, economic, and political attitudes among Mexicans over time—revealing the importance of both traditional and contemporary values in explaining citizen behavior.

Featured image credit: “Mexico, Puebla, Cuetzalan” by CrismarPerez. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post A reading list of Mexican history and culture appeared first on OUPblog.

Medical specialties rotations – an illustrated guide

Starting your clinical rotations can be a daunting prospect, and with each new medical specialty you are asked to master new skills, knowledge, and ways of working. To help guide you through your rotations we have illustrated some of the different specialties, with brief introductions on how to not just survive, but also thrive in each.

Emergency Medicine

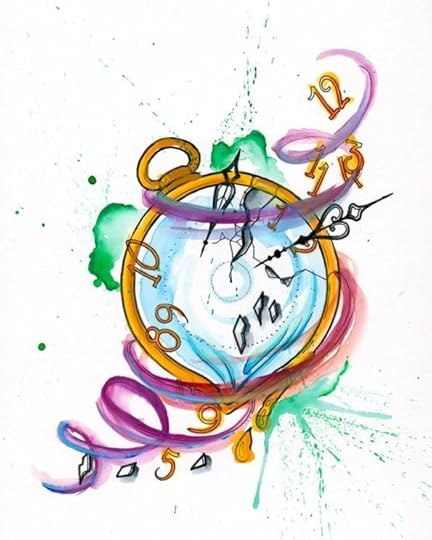

Emergency medicine feels the pressure of time; patients are waiting for you, targets need to be met, and life-saving decisions need to be made. Salvador Dali’s melting clocks, however, remind us that time is neither relative nor fixed; attempting to forcibly manipulate time beyond your abilities can disrupt the natural progression. The department will always seem chaotic. Take the time you need to ensure that neither you nor the patient spirals out of control.

Image from the Oxford Handbook of Clinical Specialties. Used with permission © Gillian Turner

Gynaecology

The spiral is a pagan fertility symbol. In gynaecology, the major milestones are marked by the beginning (menarche) and end (menopause) of a woman’s fertile period. Treatment is balanced between improving symptoms and fertility wishes.

“It is more important to know what sort of patient has the disease than what kind of disease the patient has.” -Caleb Parry (1755-1822)

Parry was fascinated between the connection between events in his patients’ lives and their diseases. His aphorism is particularly relevant to gynaecology because many of the diseases are chronic, and the choices of treatment are many. Take endometriosis for example – what is the right treatment? Well, this depends on who has got it – where they are in their lives, how much the pain matters, what the plans are for future pregnancies etc.

Image from the Oxford Handbook of Clinical Specialties. Used with permission © Charlotte Goumalatsou

Paediatrics

Helter skelters should be fun – as should our childhood. Pushing off at the top requires bravery and boldness, and so do many new adventures and experiences in childhood. These years are about finding our way in life. In order to do this we need the boundaries, love, and protection that allow us to flourish in a positive and safe way (helter skelters would not be fun without the protective side wall). Good health allows us to grow and develop, yet there should be access to healthcare and treatment when required. Not all children have good health, access to healthcare, or a safe and loving home. It is our job to try and ensure we identify those in need and put in place what is needed to help them climb back up to the top of the slide and continue on their journey.

Image from the Oxford Handbook of Clinical Specialties. Used with permission © Carolyn Pavey

Orthopaedics

“To thrive in life you need three bones; a wish bone, a back bone, and a funny bone.” -Reba Mcentire.

It is easy to look at a single joint in isolation, yet the masters of this specialty are able to take a step back and optimize the entire body structure. Orthopaedic surgery embraces the entire patient journey from diagnostic assessment, operative interventions, and rehabilitation. Knowledge of anatomy is therefore key; you won’t be able to identify the abnormal if you don’t know what normal is!

Image from the Oxford Handbook of Clinical Specialties. Used with permission © Gillian Turner

Psychiatry

If you stare at the image, you will start to see the spiral spin. Your brain is tricking you into believing that this two-dimensional image has genuine depth and movement. This optical illusion causes your brain to confuse the subjective experience with an objective reality and this is happening because your brain is working as it should.

But what happens if odd experiences like this start to intrude on your life? When living with a mental illness, it isn’t so easy to filter things and find the objective. And mental illness can define who you are in a way that physical illness do not.

In psychiatry you will develop the ability to understand, recognize, and treat people who are having experiences which are stopping them living their lives the way they would like.

To be a good psychiatrist (or doctor, friend, or human) you need to listen to the person telling you about their experience. So listen… if you listen, you may be able to help.

Image from the Oxford Handbook of Clinical Specialties. © Baldwin, Hjelde, Goumalatsou, and Myers. Used with permission.

Obstetrics

The uterine spiral arteries sustain life in utero, bathing the placenta with nutrients which twist and wind their way down the umbilical vein to the baby, to be returned to the placenta by coiling umbilical arteries.

Pregnancy is a risky affair for babies and mothers. There are many direct causes of maternal mortality in the United Kingdom, but if an obstetrician could be granted one wish, it would not be to abolish these; rather, it would be to make every pregnancy planned and desired by the mother. Worldwide, a woman dies every minute from the effects of pregnancy, and most of these women never wanted to be pregnant – but either had no means of contraception or were raped. So the real killers are poverty, ignorance, and non-consensual sex, and the real solutions entail education, economic growth, and an equality of dialogue between the sexes.

Image from the Oxford Handbook of Clinical Specialties. © Baldwin, Hjelde, Goumalatsou, and Myers. Used with permission.

Primary Care

GPs may feel the weight of the universe as they navigate the seemingly infinite workload and resist collapsing into a black hole. However, the spiral shape of our own galaxy, the Milky Way, is a reminder to think about the opportunities for holistic and integrative care on an individual level; to pick up cues as to what is really important to our patients, and to make a real difference to their well-being, mental health, and social functioning.

Image from the Oxford Handbook of Clinical Specialties. © Baldwin, Hjelde, Goumalatsou, and Myers. Used with permission.

Trauma

The Koru is frequently used in Maori art as a symbol of perpetual movement and creation. It is based on the unfurling fern frond which eventually points inward to indicate an eventual return to the beginning. As the fern unfurls, the people of New Zealand view the Koru as a new beginning. Each of your patients is a new opportunity to do your best. Don’t let the tough shifts pull you down, instead touch them into your Koru so that your return to equilibrium is hastened. Those experiences will stay with you but it’s your choice how you let them affect your next patient. Victims of trauma, no matter how trivial, have suddenly been ripped out of their comfort zone. It’s our job to guide their Koru back to harmony and facilitate their new beginning.

Image from the Oxford Handbook of Clinical Specialties. Used with permission © Gillian Turner

Ophthalmology

Doctors assume that our eyes are passive organs whose sole job is receiving and organizing photons. Philosophers and physiologists are less sure. Ludwig Wittgenstein once said:

“When you see the eye, you see something going out from it. You see the look in the eye. If you only shake free from your physiological prejudices, you will find nothing queer about the fact that the glance of the eye can be seen too. For I also say that I can see the look you cast at someone”

If you were Wittgenstein’s pupil and he cast you one of his notorious glances in a tutorial, would you meet his gaze? Choosing where to look can be perplexing. You might toy with the idea of looking in the eye, but then back off. MRI shows different parts of the medial frontal cortex are active when we choose to make eye movements of our own free will, compared to when we face duress and conflicting choices.

So studying eye movements teaches us about the seat of the soul, if we accept that appreciating and resolving ambiguities is the essence of consciousness.

Image from the Oxford Handbook of Clinical Specialties. Used with permission © Ken Banks

Anaesthesia

Staring at the centre of this spiral for long enough might just trick your mind into a hypnotic stupor, yet we suspect you would snap back to reality should a needle venture your way.

The full triad of muscle relaxation, hypnosis, and analgesia is required for effective anaesthesia to take place. Should one component be misplaced, situations such as awareness, agitation, and pain arise. Anaesthetists are masters at balancing and manipulating this triad to ensure the necessary surgical procedure can take place. The role of the anaesthetist has expanded to encompass not only the provision of ideal operating conditions for surgery, but also intensive care, resuscitation, alleviation of acute and chronic pain, obstetric anaesthesia and anaesthesia for diagnostic procedures. A detailed knowledge of general medicine, physiology, pharmacology, the physical properties of gases, and the working of the vast array of anaesthetic equipment are essential in order to practise well.

Image from the Oxford Handbook of Clinical Specialties. © Baldwin, Hjelde, Goumalatsou, and Myers. Used with permission.

Featured image credit: Hospital by OpenClipart-Vectors. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Medical specialties rotations – an illustrated guide appeared first on OUPblog.

In the oral history toolbox

Throughout 2016 we’ve featured oral history #OriginStories – tales of how people from all walks of life found their way into the world of oral history and what keeps them going. Most recently, Steven Sielaff explained how oral history has enabled him to connect his love of technology and his desire to create history. Today we launch a new series we’re calling #HowToOralHistory, where we invite you to explain some small aspect of your oral history practice. Our goal is both to promote best practices and to appreciate the detailed work that goes in to producing high quality oral history – from researching and recording, to transcribing, reviewing, editing, producing, publishing, and public presentation.

To kick off our #HowToOralHistory series, we invited Steven Sielaff to come back and explain some of how he estimates the costs – both in time and money – to produce a single well researched interview.

Question: How much time should a small project budget to create a single oral history interview?

I have developed a general hourly cost schedule for use in the Baylor University Institute for Oral History, and I’ve tried to adapt it a bit for a one-person shop. I’m sure other people will have a variety of estimates depending on the composition of each oral history center and their policies regarding transcripts. Here are my results:

Calculations are in man-hours, and standardized for a one-hour interview:

Pre-Interview Research: 4-8 hours

Interview: 2-4 hours for onsite, 8 for local travel, 16 for longer

Audio Processing/Transcription: 15-20 hours

Review: 2-3 month wait

Post-Review Edits: 5 hours

Final Editing: 5 hours

Total: 30-60 hours, over 3-4 months

A few notes here:

I use one hour of audio as a control – obviously if your interviews are longer it will require more time for certain tasks such as transcribing/editing etc., so you can apply a multiplier based on your average length if you’d like.

The prep work and actual interview time can vary wildly depending on your topic and if you need to travel, so I provided a range there. For instance, I recently completed a long interview series I conducted in my office, so my prep involved listening to the previous interview while researching the two or three topics I planned to cover next. I usually would set aside half a day for this. If you are starting a project from scratch, obviously you will want to do more research.

I typically tell people it will take five to ten hours to transcribe one hour of audio. The low end represents an experienced listener and fast typist, the high end a novice. I also built into this transcription category the time it will take for you to audit check and initially edit your work. Remember, you want to represent yourself favorably when you send any produced materials to your narrators for the first time.

I included a review phase merely to point out how long we give our interviewees to correct their transcripts. Obviously you can not move forward until you receive the reviewed transcript back, so you will need to factor that into the overall consideration of what you can accomplish in a year, even though it might not directly be reflected in your own hours. For us, transcription review also serves as an additional ethical layer during processing, confirming the comfort level and willingness of the interviewee when it comes to presenting their interview to the world.

The final two categories are for adding corrections and final editing, which for us means making the final product “pretty” when it comes to overall amount of content included (updated information and/or editor notations) and style of the document. We will currently place what we call draft transcripts online that do not include the “Final Editing” steps, so you may or may not be interested in including this final category in your calculation.

In short: it varies. Every interview is different, but this guide can help to budget time when planning out an oral history project.

This guide was adapted from an answer Steven Sielaff provided on H-OralHist.

We are accepting proposals for both our #OriginStories and #HowToOralHistory articles for the next few months and look forward to hearing from you. We ask that finished articles be between 500-800 words or 15-20 minutes of audio or video. These are rough guidelines, however, so we are open to negotiation in terms of media and format. We should also stress that while we welcome posts that showcase a particular project, we can’t serve as landing page for kickstarter or similar funding sites. Please direct any questions, pitches, or submissions to the social media coordinator, Andrew Shaffer, at ohreview[at]gmail[dot]com.

Image: “Measuring Tape” by Jamie, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post In the oral history toolbox appeared first on OUPblog.

The transformative era in Sikh history

The ideology of ‘Raj Karegā Khalsa’ was enunciated in the time of Guru Gobind Singh. It provided the background for political struggle and conquests of the Sikhs after him. The roots of doctrinal developments and institutional practices of the eighteenth-century Sikhs can be traced to the earlier Sikh tradition. The basic Sikh beliefs like the unity of God and the ten Gurus and the doctrines of Guru Panth and Guru Granth continued to figure as the foremost tenets. The sanctity of the dharamsal was enhanced as the locus of the Granth and the Panth as the Guru. The term Gurdwara came to be increasingly used, particularly for the dharamsals associated with the Gurus and the Sikh martyrs. With its sacred tank (amrit sarovar), the Harmandar, and the Akal Bunga, Ramdaspur (now called Amritsar) became the premier centre of Sikh pilgrimage. Rejection of Brahmanical, Islamic, and some popular practices was a logical corollary of the exclusive concern with individual and congregational worship.

Repudiation of non-Sikh, especially Brahmanical, practices was built into the evolving Sikh rites and ceremonies. Before the institution of the Khalsa, compositions of Guru Granth had come to be seen as relevant for different stages in a Sikh’s life: the Anand for birth; the Anand, Sohila, Ghoṛiān, and the Lāvān for ceremonies related to marriage; and the Japujī, Alahṇiān, Anand, and the Sadd for death. Replacing the charan amrit, Guru Gobind Singh had introduced initiation of the double-edged sword (khande kī pahul). A person from any caste, creed, or gender could be initiated into the Sikh fold. Integral to all ceremonies was the collective prayer (ardās), followed by the partaking of kaṛāh parsād (sacred food), and often also the langar. The obligations and proscriptions attending the new initiation rite transformed the initiate in a fundamental way and strengthened the Kesdhārī vis-à-vis the Sahajdhārī identity.

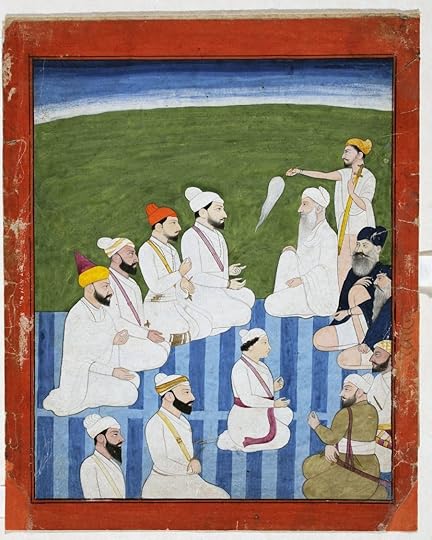

Sardar Jai Singh Kanhaiya as Suzerain of the Hill Chiefs. Source: Government Museum and Art Gallery, Chandigarh (India). Image used with permission.

Sardar Jai Singh Kanhaiya as Suzerain of the Hill Chiefs. Source: Government Museum and Art Gallery, Chandigarh (India). Image used with permission.Built into this situation was the conscious creation of a social order with serious ethical concerns, touching all aspects of a Sikh’s personal, communitarian, and social life: culinary and domestic matters; abstinence from intoxicants, tobacco, sensuality, and illicit relations; preference for honest living, good conduct, soft speech, and service of others (par-upkār), particularly of the poor, the hungry and the naked. War ethics of the Khalsa required them not to attack a fugitive and a non-combatant, nor to molest and enslave women.

Initially, the term Khalsa denoted both Sikh and Singh directly linked to the Gurus, unlike the Masandiās, Miṇās, Dhīrmalliās, and Rāmrāiyās. As the Khalsa gained power, they became synonymous with Singhs who came to constitute the mainstream in the Sikh social order. The ideal of equality enabled the lowly Jats, Tarkhāns, and Kalāls to acquire power. The traditional patterns of matrimony re-surfaced under Sikh rule, but only the erstwhile untouchables were excluded for commensality, creating thus a large space for the low-castes. However, social interactions and gender relations were not free from tension between an egalitarian ideology and conservative social practice; the inegalitarian patriarchal family too was taken for granted.

Historical change and needs of the new community led to the emergence of new literary forms: the Rahitnāmā, the Gurbilās, the Shahīd Bilās, and the Ustat. The Vār and the Sākhī forms came down from the seventeenth century. Much of this literature was produced to instruct and inspire. An evolving historical consciousness is evident in the expanding scope of Sikh literature. Apart from the life and message of Guru Nanak, it came to include episodes concerning the successor Gurus, narratives of the life of Guru Gobind Singh, institution of the Khalsa, the Khalsa rahit, the Khalsa warriors and martyrs, glory of Amritsar and other places associated with the Gurus, besides the lives of the eminent Sikhs.

A new spirit was reflected also in Sikh painting and architecture. There are signs of an emerging ‘Sikh’ style in painting. Barring the portraits of Sikh rulers produced in the late eighteenth century, the Sikh works of art were directly linked to Sikh faith. A distinct ‘Sikh’ style of architecture was developing at Amritsar towards the end of the century, with resources coming largely from the emergent Sikh rulers.

The political revolution underpinned by the ideal of ‘Rāj Karegā Khalsa’ had raised the erstwhile plebeians to the status of rulers and jagirdars who derived inspiration from Khalsa ideology. The Sikh identity emphatically became the Khalsa identity as ‘the third (tīsar) panth’. The eighteenth century in Sikh history became a bridge between what had gone before and what came afterwards. Thus, the period which started with the ideology of ‘Rāj Karegā Khalsa’ ended with the fact of ‘Khalsa Rāj’ when Sikh sovereignty was declared at Amritsar in 1765.

The post The transformative era in Sikh history appeared first on OUPblog.

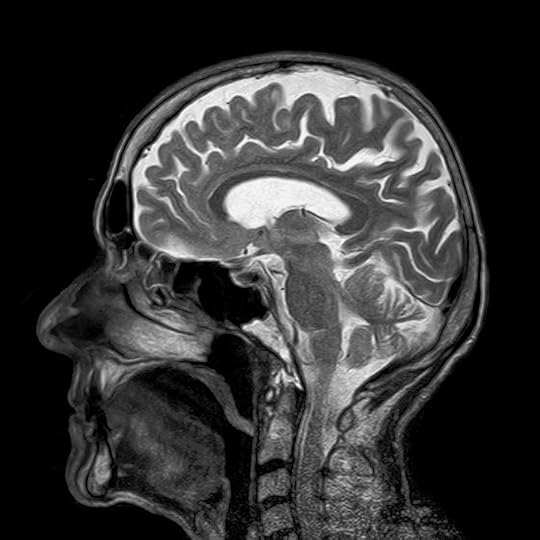

What has functional brain imaging discovered?

Functional magnetic brain imaging (fMRI) is a method that allows us to study the workings of the human brain while people perceive, reason, and make decisions. The principle on which it’s based is that, when nerve cells or neurons in a particular region become active, there is an increase in the blood supply to that brain area. This can be visualized because the scanner can be sensitized to the changes in the blood oxygen level that occur when the nerve cells become active.

The initial demonstration where this was possible was made in 1990 and we are now 26 years on, so it is reasonable to ask what fMRI has discovered in that time. A fair comparison is with another imaging technique, the electron microscope. The first such microscope with a high resolution was built in 1938, and within 30 years it revealed vesicles at the end of the nerve terminals. These contain the transmitters that are released when the nerve cells become active, and it is these transmitters that then influence the activity of the cell with which they are connected.

So what has fMRI discovered? The answer is that, of course, there is a whole list of detailed things that we did not know about the human brain before the advent of fMRI. After all, people can speak, do arithmetic, and evaluate syllogisms and animals can’t. Before the invention of functional brain imaging the only way we had of studying the neural basis for these and other abilities was to see how they are affected when people suffer from strokes or brain tumours or undergo operations on the brain. The problem is that, though studies of this sort can identify the brain areas that are critical, they cannot tell us how those brain areas work.

MRI x-ray by toubibe. Public domain via Pixabay.

MRI x-ray by toubibe. Public domain via Pixabay.By using fMRI to identify which areas of the brain are active when people do these things, we can now produce a much more accurate and detailed map of the different functional areas. And indeed this year Matthew Glasser, David Van Essen, and their colleagues have delineated 180 different areas in each human cerebral hemisphere that are distinct in their anatomy and connections and that are also likely to be distinct in their exact function. This is a very major achievement.

But can fMRI do more than ‘mapping’? In other words can it tell us about mechanisms, that is how the different areas do what they do? Well, one clear advantage of fMRI is that, when people perform cognitive tasks in the scanner, the brain images shows us the activity of all the areas that are involved in that task. To use the technical term in the literature, fMRI is a ‘whole brain method.’ This means that we can study how the different areas interact.

This has led to two fundamental discoveries. One is that brain area A interacts with area B in task or context 1 but with area C in task or context 2. We owe this finding to Karl Friston and Anthony Mcintosh. The second is that it is possible to identify different functional networks that operate dynamically, meaning that network A is active during operation 1 whereas network 2 is active during operation 2. We owe this finding to Marcus Raichle and his colleagues.

Recently I have been wondering what other questions fMRI has answered where the answer cannot be given by simply pointing to the location or locations in which activity occurs. In a book with James Rowe called A Short Guide to Brain Imaging, we ended by taking six issues in normal and abnormal psychology and trying to show how fMRI and related methods could be used to provide such answers. And this set me thinking whether I should challenge myself to provide a more extended treatment on the same topic. The result was my Very Short Introduction to the topic, and this blog post!

Featured image credit: Abstract hi-tech cyber by Activedia. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post What has functional brain imaging discovered? appeared first on OUPblog.

September 15, 2016

Influencing social policy in the public interest

How can psychologists and other social scientists interested in making a difference become more fully and effectively engaged in the policy world? To address this question, in-depth interviews were conducted with 79 psychologists who were asked to describe their policy experiences over the course of their careers, with particular focus on a major policy success. They described varied vantage points through which to influence policy, key policy methods, a core set of policy influence skills, and important guiding principles honed through years of policy influence activity.

Vantage points for policy influence

Three important vantage points provide settings and roles by which psychologists and other social scientists can influence policy.

Researchers in academia, both in traditional departments and in interdisciplinary policy centers.

Administrators and staff in a variety of intermediary organizations, including professional membership organizations, national academies, consulting and evaluation firms, and foundations.

Policy insiders, including staffers for legislators or legislative committees, elected officials, and executive branch officials or civil servants.

Policy methods

Use of varied methods are central to effective policy work. These include:

Serving on policy advisory groups

Direct communication with policymakers

Courtroom-focused activities

Consultation and technical assistance

Generation of policy-relevant documents

External advocacy

Use of the media

Conference, microphone by fill. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

Conference, microphone by fill. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.Some of these methods constitute a direct policy pathway, involving direct communication with policymakers and their staff. Other methods involve an indirect policy pathway, relying on communication with others (e.g., advocacy groups, media, citizens) who in turn exert influence on policymakers. Furthermore, the methods vary in the extent to which the underlying mechanism of influence relies on education, guidance, persuasion, or pressure.

Policy skills

Four sets of skills appear essential to effective policy work.

Relationship building skills contribute to productive engagement with key legislative and/or executive branch policymakers (or their staff members), individuals in intermediary organizations, media, practitioner groups, and/or researchers in multiple disciplines.

Research skills are critical both for scholars conducting original research and for those in “translational” roles in intermediary organizations and government. For the latter, the capacity for critical analysis (differentiate stronger from weaker research) and to generate research syntheses (integrative research reviews) are especially important.

Communication skills, though related to relationship building, stand in their own right as another critical policy-influence skill. Both oral and written communication skills are important, as is the ability to generate and communicate a compelling policy narrative.

Strategic analysis encompasses both policy analysis and strategy development. Knowledge of the political and policy process is a necessary precondition for effective strategy development.

Guiding principles

Collectively, the personal experiences of those interviewed underscore a number of guiding principles related to psychologists’ involvement in policy-influence work in the public interest. These guiding principles represent what our field can learn from seasoned psychologists who work to enhance our country’s social policies, and include:

Being strategic in every aspect of the research-to-policy endeavor

Getting the message out

Developing relationships and partnerships with policy players

Developing or evaluating innovative programs and establishing cost-effectiveness

Being resilient, persevering, and staying on the lookout for opportunities

Psychologists consider the policy arena and their work within it to be exciting, unpredictable, frustrating, rewarding, and challenging, but also essential. Although extremely important, this work is not easy. Respondents were forthright about the barriers to success and the difficulty of achieving policy change, their policy-influence victories notwithstanding. Indeed, the challenges facing all of us as we strive to influence social policy are legion. Vested interests, partisan politics, and tight budgets are some of the external barriers to transforming innovative ideas into tangible forms of policy change. Lack of policy knowledge, limited immersion in policy networks, and the absence of professional incentives for this work are some of the internal challenges. Nonetheless, those interviewed have succeeded in contributing in important ways to policy change in the public interest.

Featured image credit: ‘London Underground train station’ by Unsplash. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Influencing social policy in the public interest appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers