Oxford University Press's Blog, page 468

September 8, 2016

Rethinking human-elephant relations in South Asia

Throughout history and across cultures elephants have amazed and perplexed us, acquiring a plethora of meanings and purposes as our interactions have developed. They have been feared and hunted as wild animals, attacked and killed as dangerous pests, while also laboring for humans as vehicles, engineering devices, and weapons of war. Elephants have also been exploited for the luxury commodity of ivory, laughed at as objects of entertainment, and venerated as subjects of myth and symbolism. Throughout history humans have forged deeply effective connections with elephants, both as intimate companions and as spectacles of wonder.

Clearly, we do not wish to see the elephant disappear from the world, and conversations about elephant welfare and conservation are also conversations about what it is to be humans in relations with elephants. Even as the compartmentalizing character of Western knowledge systems have achieved dominance, it has become increasingly difficult to treat the elephant merely as an animal occupying its own habitat. It strays into our own both spatially and conceptually. Our lives have intersected and our worlds have been forged through reciprocal influence, both direct and indirect. Elementary as this observation may seem, the impossibility of sustaining the elephant as an animal-other occupying a separate spatial and categorical domain presents us with some very profound challenges, not just for how we live with elephants, but also for how we think with them. Neither their nature, nor our culture can be explained without the other, whether it is the distribution of tusked males in regions with histories of selective hunting and capture, or warring kingdoms in which the elephant represented a crucial battlefield technology.

“Milk time for a juvenile orphan at the Uda Walewe Elephant Rehabilitation Center, Sri Lanka, 2013”. Image by Piers Locke, used with permission.

“Milk time for a juvenile orphan at the Uda Walewe Elephant Rehabilitation Center, Sri Lanka, 2013”. Image by Piers Locke, used with permission.Indeed, elephants problematize the distinguishing coordinates of natural animals and cultural humans around which our expert disciplinary knowledges have been elaborated. This reaches its apogee in specializations that variously understand the elephant through the lens of the sciences and the humanities, typically producing distinct practices and isolated conversations conducted in expert languages with limited commensurability.

Consequently, while we have described myriad forms of inter-species encounter involving humans, elephants, and their environments, we have also produced multiple forms of expert knowledge which we struggle to integrate. Furthermore, these forms of knowledge, or at least the academically dominant ones, until recently rarely treated elephants in anything but generic terms, tending to ignore their varied dispositions negotiating relationships with creatures like ourselves. If we admit that understanding human-elephant relations across space and through time requires combined consideration of their social, historical, and ecological aspects, then how might we expect the literary expert on Sanskrit elephant lore to meaningfully communicate with the biological expert on elephant behaviour or the anthropological expert on captive elephant management? How might we bring the voice of local expert practitioners into the conversation? And if we admit that elephants have cognitive, communicative, and social capacities for exercising agency in individually distinctive ways (as other knowledge traditions remind us), then how might we better understand how particular elephants and particular humans engage each other?

With an agenda that is inextricably practical and conceptual, this concern with using the figure of the elephant and the problems our relations with it present in order to rethink how humans live with other life forms in shared environments, is but one example of a much broader shift that some are calling ‘The Multispecies Turn’. Taking the human off its pedestal of ontological singularity and reasserting its interdependent agency among the social and ecological activity of other life forms, it is significant that this attempt to think beyond the human and with the nonhuman is occurring in a period of planetary change marked by human influence that many are now calling ‘The Anthropocene’.

“The mighty Erawat Gaj and his handler Bishnu Chaudhury, Khorsor Elephant Breeding Center, Chitwan, Nepal, 2004”. Image by Piers Locke, used with permission.

“The mighty Erawat Gaj and his handler Bishnu Chaudhury, Khorsor Elephant Breeding Center, Chitwan, Nepal, 2004”. Image by Piers Locke, used with permission.Somewhat ironically then, it is just as we are finding cause to designate a geological ‘age of man’ that we are rediscovering the need to undo our conceits of conceptual segregation, to assess all life together, and to attend to the life-ways through which human and nonhuman species encounter and influence each other. Crucially, this is occurring in the humanities as well as the natural sciences, through attempts to make different forms of knowledge articulate with each other. Such a move to reconfigure our fundamental intellectual coordinates is already proving productive.

For elephants this means acknowledging their historically emergent life-ways, their individual and group biographies, and their entangled role in our social and environmental ordering processes, just as we do for humans as social beings making their world in the course of experiencing and inhabiting it with others. By attempting to combine the perspectives of the social and the natural sciences, and by attending to the actual experiences of humans and elephants in relation with each other, we are beginning to do away with our species-centric prejudices, recognizing that humans are not the only thinking, feeling, and decisive agents at play in our world.

The implications of this kind of rethinking of human-elephant relations are potentially radical, and an attempt to create an intellectual space that breaches disciplinary silos, that encourages interdisciplinary collaboration, and that better attends to the world-making subjectivities of humans and elephants is emerging under the rubric of ‘ethnoelephantology’.

Might a less anthropocentric perspective enable us to begin transforming those values and convictions that seem so implicated in the anthropogenic crises we have brought upon the planet and its life-support systems? Might greater attention to the generative complexities of humans’ and elephants’ intersecting life-ways direct us toward new ways of thinking about an inter-species relationship that has become increasingly problematic? And might this help us learn to live well with a charismatic herbivore that is so valued in the cultures of South Asia?

Featured image credit: “The elephants and their drivers depart for a day of grazing and bathing, Khorsor Elephant Breeding Center, Chitwan, Nepal, 2011”. Image by Piers Locke, used with permission.

The post Rethinking human-elephant relations in South Asia appeared first on OUPblog.

September 7, 2016

Our habitat: booth

This post has been written in response to a query from our correspondent. An answer would have taken up the entire space of my next “gleanings,” and I decided not to wait a whole month.

Although we speak about telephone booths, in Modern English, booth more often refers to a temporary structure, and so it has always been. The word came to English from Scandinavia. In its northern shape it is most familiar to those who have read Icelandic sagas. Medieval Iceland was settled by colonists from Norway (mainly) and had no royalty. To settle legislative issues, free farmers from the entire country met at the general assembly (“parliament”) called Alþingi (þ = th); there also were local “things.” People naturally traveled on horseback, and, to reach the field where the assembly was held, some participants needed many days. There they set up “booths.” The annual meeting lasted two weeks, so that booths remained empty for most of the year. They could be called temporary only because they were not occupied the whole time. Sentences like: “So-and-so arrived at the Alþingi and set up a booth” should probably be understood as meaning that the owner furnished the abode anew. Such abodes varied greatly, depending on the farmer’s wealth and pretensions. In any case, they were certainly not mere tents, for a common scene describes guests entering a booth and being entertained there.

This is a modern view of the place where in the Middle Ages the Icelandic General Assembly was held.

This is a modern view of the place where in the Middle Ages the Icelandic General Assembly was held.The word first surfaced in English in the thirteenth century in a poem called Ormulum, about which something was said in the post of 9 December 2015 (it dealt with the adjective blunt, another item of the English vocabulary that surfaced first in that work). The author of the poem, Orm or Ormin, spoke a dialect that was full of northern words. The origin of the noun booth poses no questions. Its root is bū-, as in the Old Icelandic verb búa “to live,” while –th is a suffix, as in Engl. death, birth, dearth, and others, in which it is no longer felt to be an independent element. Originally, the word must have meant “dwelling,” the most neutral name for a human habitat imaginable. The same root can be seen in the English verb build, from Old Engl. byldan “to construct a house” (its modern spelling was discussed on May 2, 2008, in one of my oldest contributions to the series “The Oddest English Spellings”). Old English had bold “dwelling, house”; its cognates—Old Frisian bōdel, Old Saxon bodl, and Old Icelandic ból—meant the same. In principle, the Icelandic word had to be bóþ, but it took over its vowel from the verb búa.

Also Engl. bower, from būr, has the same root. Like its Germanic cognates, it once meant simply “dwelling.” This word is a delight of the students of Old High German, for it occurs in the famous poem (song) about the hero Hildebrand, who went into exile with his lord and left his wife and small son in such a būr (in modern editions, vowel length in Old High German words is usually designated by the circumflex: ū = û). This būr corresponds to Engl. bower “a lady’s boudoir.” It is as though some words are destined to move up or down. English būr has narrowed and ameliorated its meaning (not just a dwelling but a lady’s apartment), while its German cognate Bauer deteriorated and fell from “dwelling” to “birdcage.” (And here is a small excursus on gender studies. Old High German būr was masculine, while Old Engl. būr was neuter. English has providentially lost gender distinctions, contrary to German, which still has the masculine, the feminine, and the neuter, so that Engl. bower is just bower. But German Bauer is now predominantly neuter, as was its Old English cognate! The neuter must have been chosen to distinguish Bauer “cage” from Bauer “farmer.”)

Yes, Bauer “farmer,” a word rather well-known outside the German-speaking area, is historically just “a settler.” It once had a prefix and had the form gibūr but lost it; hence the later homonymy with Bauer “birdcage.” English speakers are well aware of the Dutch/Low German cognate of Bauer, namely boor, and, of course, many people still remember that the military history of the bloody twentieth century began with the Anglo-Boer War, by 1900 already in full swing. Engl. boor and boorish have strong negative connotations, which is not surprising. In the usage of feudal Europe, the source of gentility was towns (compare urban and urbane), while coarseness was associated with rough and uncultivated peasants (compare village and villain, both from French, and rustic, ultimately from Latin rūs “village”). Modern Dutch distinguishes boer “peasant, farmer,” bouwer “builder,” and buur “neighbor.” It is buur that interests us most, because Engl. neighbor, from nēah-ge-būr, meant someone who lives near, literally, “nigh.” We have seen Old High German gi-būr and recognize its analog in the Old English form.

Here is one of the sad scenes from the Anglo-Boor War.

Here is one of the sad scenes from the Anglo-Boor War.And now we should return to our booths. English had no cognate of Old Icelandic búþ, for booth, as noted, is a loan from Scandinavian. But German Bude “hut” is a regular congener of the Scandinavian noun. Although it surfaced late, it seems to be old. Those who have read my post on the etymology of house (21 January 2015; it was followed by a post on the unrelated home) will remember that this Germanic word made its way into Old Slavic. Once upon a time, hūs seems to have meant “shed” or “hut.” The most general word designating a human dwelling has a lower chance of being borrowed than the name of a special structure: shieling, booth, shanty, shack, hovel, and their likes. Words pertaining to shepherds’ culture are especially prone to migrate; see also below. German Bude (or its earlier form buode) has penetrated all Slavic languages. Russian has budka; k is a diminutive suffix. Elsewhere in Slavic the forms are also buda, budka, bouda (note this Czech word), and so forth. The senses differ little: “hut,” “stall (at a fair),” and often “a little house made of tree branches.” In Old Russian, buda occurred once and meant something like “a plaited coffin.” One can ask how we know that the word was borrowed by Slavic from German and not the other way around. The answer is obvious: buda is opaque and has no Slavic etymology, while Germanic booth is transparent. By the way, Engl. abode has nothing to do with this story. It is related to the verb abide, from which we have bide and which meant “to wait,” as in bide one’s time. An original abode was a place for waiting rather than living.

This is a picture of a shieling. Such primitive abodes have names that travel easily from land to land.

This is a picture of a shieling. Such primitive abodes have names that travel easily from land to land.Curiously, in German we also find the word Baude “a shepherd’s mountain hut,” which turned up in texts only in 1725. If it were a regular continuation of buode, it would have had a different phonetic shape. That is why there is a consensus (a rare thing in etymological studies) that Baude is a borrowing from Czech—a curious but not too rare case of a word moving back and forth from language to language. Students of English know how very often Old Romance borrowed words from Old Germanic (the intermediaries were usually the Franks), and how much later the French reflexes of those words resurfaced in Middle English and thus returned to their Germanic, even if not quite their original, home.

Certain quotations have been trodden to dust, and no author with a grain of self-respect should use them. One of them is habent sua fata libelli “books have their fates.” Never mind books. My point is that words also have their fates (habent sua fata verba). They are born, flourish, fight, disappear, and travel from land to land. They did not have to wait for the term globalization to cross tribal and national borders.

Image credits: (1) Iceland, Thingvellir by jemue, Public Domain via Pixabay. (2) Anglo-Boer War by Skeoch Cumming W, Public Domain via Wikipedia (3) “Lone shieling” by Tim Bryson, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Featured image: Rustic Cabin by Unsplash, Public Domain via Pixabay

The post Our habitat: booth appeared first on OUPblog.

The Battle of Britain and the Blitz

On 7 September 1940, German bombers raided the east London docks area in two waves of devastating attacks. The date has always been taken as the start of the so-called ‘Blitz’ (from the German ‘Blitzkrieg’ or lightning war),when for nine months German bombers raided Britain’s major cities. But the 7 September attack also came at the height of the Battle of Britain, the defence by RAF Fighter Command against the efforts of the German Air Force to win air superiority over southern England as a preparation for Operation Sea Lion, the German invasion of Britain.

In reality the Battle of Britain and the Blitz were closely related. The raid on London was supposed to signal the last stage of the ‘softening up’ of southern England prior to a landing planned for 15 September. By disrupting trade, transport, and services the German side hoped to create panic in the capital and hamper the government’s efforts to counter the invasion. The failure to win air superiority, made clear on the very day that Hitler had hoped to invade, 15 September (now celebrated as Battle of Britain Day), meant that the bombing of London, if it continued, would have to serve a different strategy. The Blitz, despite its reputation as an example of pure terror bombing, became part of a combined air-sea effort to blockade Britain by sinking ships, destroying port facilities, warehouse storage, milling plants, and oil and food stocks. To prevent the RAF from contesting the blockade, vital aero-engine and component firms were targeted, most famously in the raid against Coventry on 14 November. No effort was made to avoid human casualties, though Hitler rejected simple terror bombing, and the German Air Force regarded attacks on residential areas as a waste of strategic resources.

The raid on 7 September also had another purpose. It was defined as a ‘vengeance attack’ in German propaganda against RAF bombing of Germany. One of the persistent myths of 1940 is the belief that Germany started the bombing war, but from the night of 11/12 May, when bombers raided the west German city of Mönchengladbach, the RAF struck at targets in or near German towns for every night when the conditions permitted. By early September, after weeks of sheltering every night, the population of western Germany demanded reprisals. Since they had already ordered the final pre-invasion raids on the capital, it was a simple thing to define the first major raid (bombs had been dropping in and around London since mid-August) as a vengeance operation in order to still domestic complaint.

The start of the Blitz and the end of the Battle of Britain overlapped. By the time the Battle petered out, with high losses to the German side for little strategic gain, Operation Sea Lion had been postponed to the spring or, if necessary, even later. The blockade campaign followed over the winter months, imposing high losses on the German bomber fleets, chiefly from accidents caused by poor flying conditions and growing combat fatigue. Hitler had little faith in independent air power, and did not think in the end that the blockade would work, or that the British people would be sufficiently demoralized by its effects to abandon the war. But by the time it was evident that the Blitz was not going to be effective, it was too late to suspend it, partly from the political backlash at home if it was halted, partly because of the boost it would give to Britain’s wartime image, but also because the bombing would persuade Stalin that Britain was Hitler’s priority, when in fact German leaders were now planning a massive assault on the Soviet Union in the early summer of 1941.

Berlin, Adolf Hitler und Hermann Göring by German Federal Archives. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Berlin, Adolf Hitler und Hermann Göring by German Federal Archives. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.In its own term, the German Blitz was very ineffective. Only 0.5% of oil stocks were destroyed, around 5% of potential war production was lost, and food stocks remained more or less intact. Aircraft production was not hit seriously, and though German intelligence speculated that Britain could only produce 7,000 aircraft in 1941, some 20,000 were produced, almost double German output. What the Blitz did achieve was a very high level of civilian casualty. By the time it ended 43,000 people had been killed, 28,000 of them in London. It is this large total that has always supported the idea that the Blitz was simply a terror attack to undermine civilian morale. The truth is more complicated. High casualties reflected the nature of the targets chosen, mostly port cities, or inland ports like Manchester, where there was much low-quality working-class housing crowded around the dock areas. The concentrated working-class areas were also the ones least likely to have been provided with secure shelter. A survey in London showed that 50% of people had no access to shelter at all and made do with local railway bridges, or the cupboard under the stairs. Research also found that shelter discipline was poor, and became more so as populations became habituated to bombing, as in London. Thousands of those killed abandoned the idea of finding a shelter; contemporary evidence shows that thousands chose in the end to sleep in their own beds and run their luck. There was no legal obligation to shelter, as there was in Germany, and shelter discipline was lax. In the early months of the Blitz, when casualty rates were at their highest, the government had also failed to anticipate what would be needed. A massive volunteer effort of men and women in civil defence and first aid prevented the disaster from being much worse than it was.

British bombing of Germany continued across the period of the Blitz, but the small size of the force, combined with poor navigation and inaccurate bombing, produced little effect. Although presented in popular memory as revenge for the Blitz, it was not intended as such, nor did much of the population favour meting out to the Germans what was happening in Britain. An early opinion poll in London showed 46% in favour of bombing German civilians, but 46% against. But once the cycle had started, it was as difficult for the RAF to abandon as it was for the Germans. In British popular memory of the war the Blitz has a central part to play as the moment when British society was tested to the brink and survived. It is perhaps for this reason that so many myths still surround the experience. The Blitz is no longer merely historical fact, but a metaphor of endurance against the odds.

Featured image: Children of an eastern suburb in Britain made homeless by the Blitz by Sue Wallace. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The Battle of Britain and the Blitz appeared first on OUPblog.

Hamilton’s descendants

Inspired by the 11 Tony awards won by the smash Broadway hit Hamilton, last month I wrote about Alexander Hamilton as the father of the US national debt and discussed the huge benefit the United States derives from having paid its debts promptly for more than two hundred years. Despite that post, no complementary tickets to Hamilton have arrived in my mailbox. And so this month, I will discuss Hamilton’s role as the founding father of American central banking and the vital importance central banking has played — and continues to play — in supporting America’s economic health. Hope springs eternal.

Hamilton had first proposed the formation of a government bank as early as 1779. He detailed his plan in the Second Report on Public Credit, submitted to Congress in December 1790. Hamilton’s arguments in favor of a government bank were prescient, stating that it would contribute to monetary stability, encourage credit creation, and help the government raise money.

Hamilton envisioned a banking system in which private banks issued paper currency that was backed by gold and silver, rather than a circulation consisting solely of the gold and silver. This way, the currency supply could expand and contract with the needs of trade. By allowing the expansion of credit beyond the precise quantity of gold and silver in circulation, Hamilton argued that a government bank could provide credit and stimulate commerce, noting that banks “have proved to be the happiest engines that ever were invented for advancing trade.” By making the currency redeemable in gold and silver, the plan ensured that banks would be cautious in how much currency they issued, since they could not issue more than they could redeem in gold and silver. Finally, Hamilton argued that a bank would afford “[g]reater facility to the government, in obtaining pecuniary aids, especially in sudden emergencies”—in other words, it would help the government to borrow money.

Hamilton’s plan for the Bank of the United States (BUS) was supported by the (largely northern) commercial and moneyed classes who liked the idea of providing more credit to support trade. It was opposed by farmers and those who mistrusted expansive central authority, particularly southerners who thought that a powerful federal government might one day outlaw slavery. The bill passed Congress and was signed into law by President Washington, over the objection of Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and Attorney General Edmund Randolph, who argued that the bank represented an unconstitutional expansion of federal power.

The Bank of the United States was established in 1791 with headquarters in Philadelphia. It soon established branches around the country. The only way of preventing private banks from over-issuing currency was to make sure that bank notes were promptly returned to the issuing bank for redemption in gold or silver. Because the BUS was the only bank chartered by the federal government, it was the only bank that could operate nationwide and was therefore uniquely qualified to restrain the excessive growth of the money supply by finding notes that had spread far and wide from their issuing bank and returning them in exchange for gold or silver.

Marriner S. Eccles Federal Reserve Board Building by AgnosticPreachersKid. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Marriner S. Eccles Federal Reserve Board Building by AgnosticPreachersKid. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The Bank’s 20-year charter was set to expire in 1811; however, the political landscape had change since the Bank’s establishment, making a renewal difficult. Bankers and business interests resented the BUS’s restraining influence on the banks’ ability to issues notes, and congressmen and senators from states that had supported the Bank’s establishment now voted against renewing its charter. Despite the support of former opponents Jefferson and Madison, who by now saw the wisdom of having a government bank, the effort to renew the charter failed.

Five years later, sobered by a financial panic in the intervening years, Congress chartered the Second Bank of the United States (2BUS). Led from 1822 by the innovative Nicholas Biddle, the Second Bank began to take on even more functions of a modern central bank (e.g., macroeconomic management, lender of last resort) and became a stabilizing force in the American economy. A charter renewal of the 2BUS was passed by Congress in 1832, but vetoed by President Andrew Jackson. Jackson, a frontiersman and brawler, had a deep mistrust of entrenched and educated elites — in short, he was the polar opposite of Biddle and, arguably, Hamilton. Jackson was an avowed foe of the bank for several reasons, not the least of which was that he believed it had supported John Quincy Adams, his opponent in the presidential election of 1828. Congress’ inability to override Jackson’s veto was the final shot in the “Bank War.” The United States would remain without a central bank until the establishment of the Federal Reserve in 1914.

The failure to renew the charters of Hamilton’s bank and its successor appears to have led to some remorse on the part of Congress. Shortly after the closure of each bank, Congress moved to charter a successor institution. The First Bank of the United States was succeeded five years after its closing by the Second Bank of the United States. Five years after the demise of the Second Bank, Congress voted to charter a third national bank, but the legislation was vetoed by President John Tyler and never became law.

The demise of the first two central banks increased economic and financial instability. Although causality is difficult to prove with certainty, it is undeniable that the United States experienced about one financial crisis per decade between the passing of the Second Bank in 1836 and the establishment of the Federal Reserve in 1914. With Nicholas Biddle at the helm, the 2BUS had begun to master many of the tools that Hamilton envisioned, and that are now successfully employed by modern central bankers. And although central banks frequently come in for harsh criticism by politicians, it is certain that prompt and effective action by the Federal Reserve during the subprime meltdown — and by other central banks subsequently — kept that crisis from developing into something much worse.

Alexander Hamilton recognized the benefits of a central bank 135 years before the United States permanently established such an institution. Although he could not have foreseen how important the successor of his brainchild would become, he was clearly far ahead of his time.

Featured image credit: First Bank of the United States (1797-1811) by Davidt8. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Hamilton’s descendants appeared first on OUPblog.

Christmas in Nazi Germany

Christmas is the most widely celebrated festival in the world but in few countries is it valued as deeply as in Germany. The country has given the world a number of important elements of the season, including the Christmas tree, the Advent calendar and wreath, gingerbread cookies, and Bach’s Christmas Oratorio, “Es ist ein Ros` entsprungen,” or “Vom Himmel Hoch.” Christmas became inextricably linked to feelings of national identity, so it is no surprise that the holiday became part of Germany’s ideological wars in the turbulent first half of the 20th century.

For the country’s large Social Democratic Party, Christmas was a time to point out bourgeois hypocrisy, contrasting pious sentiments of the middle class with the reality of working-class poverty. For the Communist Party of Germany, Christmas was the season to attack religion and capitalism. Party newspapers called Christmas a fantasy that should be abolished, while party militia took to the streets to tear down community Christmas trees, bully church-goers or throw tear gas into department stores. This left Adolf Hitler’s National Socialists to pose as the defenders of this sacred German season—their brown-shirted goon squads battling it out in public December brawls with Communist Red Front fighters. Nazis also used Christmas to promote their anti-Semitic policies, blaming Jewish businesses for rapacious practices, vandalizing these shops, and urging consumer boycotts.

German soldiers celebrating Christmas circa 1939. Image credit: “Soldatenweihnacht mit Weihnachtsbaum” from the German Federal Archives. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

German soldiers celebrating Christmas circa 1939. Image credit: “Soldatenweihnacht mit Weihnachtsbaum” from the German Federal Archives. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia CommonsIn 1933 when Hitler achieved power, Nazis at first simply tried to co-opt Christmas; party officials sponsored seasonal celebrations and appeared alongside Mary and Joseph in re-enactments of the Nativity, singing familiar carols along with their marching song, the “Horst Wessel Lied.” To further identify National Socialism with Christmas in the public mind, the new government undertook a vast program of winter welfare every December. Thousands of Nazi youth members and party volunteers collected money in Winterhilfwerke campaigns to be distributed to those families hardest hit by the Great Depression. But, at its heart, Nazism was incompatible with the traditional German approach to Christmas; like the Jacobins of the French Revolution and the Bolsheviks of the Russian Revolution, National Socialists wanted to reshape the calendar and the annual cycle of celebrations. There would be new holidays such as Hitler’s birthday, new rites of passage for youth and families, and an attempt to alter Christmas, by replacing its Christian core with secular and neopagan elements. The peaceful sentiments of Christmas had no place in a nation of racial warriors; thus the Berlin banners that proclaimed “Down with a Christ who allows himself to be crucified! The German God cannot be a suffering God! He is a God of power and strength!”

With the Nazi takeover of the school system and the national Protestant church, new hymns and carol replaced familiar favourites. Hebrew terms such as “Hosanna” or “Hallelujah” were edited out. The first verse of “Stille Nacht” was now a song of praise to Hitler:

“Silent night, Holy night,

All is calm, all is bright.

Only the Chancellor stays on guard

Germany’s future to watch and to ward,

Guiding our nation aright.”

There were those in the black-shirted S.S. elite who were genuine pagans, believers in the power of the old Teutonic gods and ancient symbols and relics. From these men came efforts to move celebrations from 25 December to the date of the winter solstice, to replace St Nicholas as the seasonal gift-bringer with Wotan, and to decorate the Christmas tree with pagan runes, swastikas or sun-wheels. On the winter solstice, S.S. men could be seen mountain tops lighting fires and performing “manly dances” with torches while in town the community were to gather around a massive bonfire from which children would ignite their candles to “bring home the light” to place on their own Yule tree.

With the beginning of the Second World War it became even more important for the Nazi state to control Christmas sentiment. To maintain morale during the holiday season Reichsmarschall Herman Göring supplied shops with plenty of extra food and consumer goods looted from occupied countries. Since the German people had too much emotional investment in the holiday for it to be directly attacked—however much National Socialists disliked its emphasis on peace and forgiveness—the Christian content was to be watered down in public celebrations and national publications. In the Advent calendar sent out by the Nazi party to families to help with its holiday celebrations the emphasis was on the solstice, decorating with pagan symbols and celebrating military successes.

However, as the war dragged on and Germany began to suffer defeats on the battlefield, government agents noted how the population continued to flock to church and how religion was sought for its comfort in the face of mounting casualties. The Nazi attitude to Christmas now turned macabre. For the 1944 edition of the official Advent calendar, the page for Christmas Eve was given over to a chilling “Poem of the Dead Soldiers” wherein readers were told “Einmal im Jahr, in der heiligen Nacht, verlassen die toten Soldaten die Wacht”: yearly on this date the ghosts of fallen soldiers rise to visit their homes and silently bless the living for whom they died. Within a few months the Nazi regime and its pagan Christmas were dead in the rubble.

Featured image credit: “Polen, Bormann, Hitler, Rommel, v. Reichenau” by Kliem, German Federal Archives. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Christmas in Nazi Germany appeared first on OUPblog.

Shakespeare’s clowns and fools [infographic]

Fools, or jesters, would have been known by many of those in Shakespeare’s contemporary audience, as they were often kept by the royal court, and some rich households, to act as entertainers. They were male, as were the actors, and would wear flamboyant clothing and carry a ‘bauble’ or carved stick, to use in their jokes. They were often allowed to get away with satirical comments that others in the court could not, but they would still have to be careful (as we see in King Lear, when the fool is whipped for going too far).

Shakespeare utilizes these characters of fools, also sometimes equated with the word ‘clown‘, throughout his plays to a variety of differing ends, but in general terms he most often portrays two distinct types of fool: those that were wise and intelligent, and those that were ‘natural fools’ (idiots that were there for light entertainment). You can see some of Shakespeare’s wise fools in Touchstone (from As You Like It, who was Shakespeare’s first use of a fool), Feste (from Twelfth Night), and Lear’s Fool (from King Lear), whereas some of his ‘natural fools’ include Lance (from The Two Gentlemen of Verona), Bottom (from A Midsummer Night’s Dream), and Dogberry (from Much Ado About Nothing).

From song and dance on stage to the costumes they wore, discover some facts about fools, and quotes from Shakespeare’s plays, via the graphic below. If you’re interested in finding out more, then download the graphic as a PDF to click through to some extended content.

Download the graphic as a PDF or as a JPG.

Featured image credit: ‘Fool’s Cap Map of the World’ by Epichtonius Cosmopolites. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Shakespeare’s clowns and fools [infographic] appeared first on OUPblog.

September 6, 2016

Why are Americans addicted to polls?

Before going into battle, Roman generals would donate a goat to their favorite god and ask their neighborhood temple priest to interpret a pile of pigeon poop to predict if they would take down the Greeks over on the next island. Americans in the nineteenth century had fortune tellers read their hands and phrenologists check out the bumps on their heads. Statistics came along by the late 1800s, then “scientific polls,” which did something similar. Nancy Reagan turned to star gazers. By 2010, the corporate world was falling in love with Big Data. Today, IBM touts the value of analytics and assigns thousands of experts to the topic, giving them the latest tool in artificial intelligence: a computer named Watson. Whether pigeon poop, private polls, or powerful processors, people have long shared one common wish: to know the future.

But in our Age of Science and our reliance on quantification, the pigeons were not going to cut it. We needed something more accurate, and that was the poll. What does the American experience teach us about polls? Are the statisticians really better at what they do than the temple priests of old?

Image Credit: Arch of Titus, Nero’s Temple, Coliseum & Arch of Constantine. Public Domain via Library of Congress.

Image Credit: Arch of Titus, Nero’s Temple, Coliseum & Arch of Constantine. Public Domain via Library of Congress.It did not start out well. Back in the 1820s, with rough-and-tumble frontiersman General Andrew Jackson running for president, the East Coast Establishment media did not know what to make of him. Reporters started going to bars, hotel lobbies, and even on trains to ask people what they thought of him. They then wrote up the results. That was the birth of polling in America. As large corporations emerged after the 1870s, retailers and manufacturing companies applied the new field of statistics to surveying (polling) in order to understand their customers’ views so as to feed their advertising and marketing campaigns. It worked pretty well, and so polling came into being by the end of the century. It was only going to be a matter of seconds before someone figured out that these tactics could be applied to politics.

In 1916, the Literary Digest emerged as one of the most highly respected public opinion surveyors, correctly predicting one presidential election after another. But then its expert political pollsters predicted in the fall of 1936 that Alf Landon, Republican governor from Kansas, would beat incumbent Franklin D. Roosevelt for the presidency. The voters did the unthinkable: 27 million voted for Roosevelt and 16.7 for Landon, who only carried two states. Roosevelt won by a landslide, earning 523 electoral votes versus Landon’s paltry eight.

What happened? The pollsters had sent out surveys to 10 million people, all of them subscribers to the Literary Digest. All drove cars and had home telephones. In hindsight, the problem was obvious: they polled well-off Republicans who, of course, supported Landon. Blue collar workers and poor people did not subscribe to the magazine, own a car, or have a phone. The latter group outnumbered the former, and they voted for Roosevelt since he promised to fix the economy. The magazine apologized with an article entitled “Is Our Face Red!” The Literary Digest went out of business a few years later.

Meanwhile, a young pollster named George H. Gallup did a better job at sampling voters, and so was able to predict the results with greater accuracy. Gallup polls went on to be highly respected across the century. But even he was not perfect. When Harry S. Truman ran for the presidency in 1948, Gallup predicted he would lose spectacularly. He ended up winning.

As recently as 2016, the polls in the United Kingdom consistently predicted that the voters would decide to remain part of the European Union. Brexit turned out to be a disaster for the government. Older voters voted to leave the EU, young voters to stay. Pollsters had failed to poll enough anti-EU voters.

But in each case, pollsters went back to work. Within days they were publishing new statistics which citizens in both countries kept reading, academics and media pundits kept discussing, and politicians kept consulting. It did not matter that there had been spectacular failures. Why?

The history of American polls suggests several reasons. The first is that by the early 1900s polls were more often correct than wrong. Second, as the number of polls increased, they were published in newspapers, later reviewed on radio and television, becoming an ongoing staple of American discourse. Put another way, Americans were increasingly exposed to this type of information during an era in history when statistics were seen as scientific, modern, and accurate. By the 1960s, they could read polling results on all manner of topics: health, sports, eating habits, education, and the odds of living a long life, among others. Most were accurate enough.

But ultimately it was a third reason that made them polling junkies: they wanted to know the future that polls either promised or hinted at. A poll that described your lifestyle and then connected it to statistics on life expectancy told you whether you had a chance to live into your 80s or longer. A poll predicting that “if the election were held today” so-and-so would win the presidency again spoke to the future, as would a series of polls defining a trend.

In the end, Americans were like the Roman general and the Rothschild family: both knew that information conveyed power and opportunity.

Featured image credit: VOTE! by AngelaCrocker. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Why are Americans addicted to polls? appeared first on OUPblog.

Misinterpretation and misuse of P values

In 2011, the US Supreme Court unanimously ruled in Matrixx Initiatives Inc. v. Siracusano that investors could sue a drug company for failing to report adverse drug effects—even though they were not statistically significant.

Describing the case in the Wall Street Journal, Carl Bialik wrote, “A group of mathematicians has been trying for years to have a core statistical concept debunked. Now the Supreme Court might have done it for them.” That conclusion may have been overly optimistic, since misguided use of the P value continued unabated. However, in 2014 concerns about misinterpretation and misuse of P values led the American Statistical Association (ASA) Board to convene a panel of statisticians and experts from a variety of disciplines to draft a policy statement on the use of P values and hypothesis testing. After a year of discussion, ASA published a consensus statement in American Statistician.

The statement consists of six principles in nontechnical language on the proper interpretation of P values, hypothesis testing, science and policy decision-making, and the necessity for full reporting and transparency of research studies. However, assembling a short, clear statement by such a diverse group took longer and was more contentious than expected. Participants wrote supplementary commentaries, available online with the published statement.

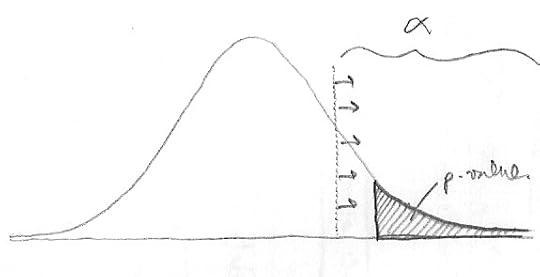

The panel discussed many misconceptions about P values. Test your knowledge: which of the following is true?

P > 0.05 is the probability that the null hypothesis is true.

1 minus the P value is the probability that the alternative hypothesis is true.

A statistically significant test result (P ≤ 0.05) means that the test hypothesis is false or should be rejected.

A P value greater than 0.05 means that no effect was observed.

If you answered “none of the above,” you may understand this slippery concept better than many researchers. The ASA panel defined the P value as “the probability under a specified statistical model that a statistical summary of the data (for example, the sample mean difference between two compared groups) would be equal to or more extreme than its observed value.”

Why is the exact definition so important? Many authors use statistical software that presumably is based on the correct definition. “It’s very easy for researchers to get papers published and survive based on knowledge of what statistical packages are out there but not necessarily how to avoid the problems that statistical packages can create for you if you don’t understand their appropriate use,” said Barnett S. Kramer, M.D., M.P.H.

STATS1_P-VALUE by fickleandfreckled. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

STATS1_P-VALUE by fickleandfreckled. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.Part of the problem lies in how people interpret P values. According to the ASA statement, “A conclusion does not immediately become ‘true’ on one side of the divide and ‘false’ on the other.” Valuable information may be lost because researchers may not pursue “insignificant” results. Conversely, small effects with “significant” P values may be biologically or clinically unimportant. At best, such practices may slow scientific progress and waste resources. At worst, they may cause grievous harm when adverse effects go unreported. The Supreme Court case involved the drug Zicam, which caused permanent hearing loss in some users. Another drug, rofecoxib (Vioxx), was taken off the market because of adverse cardiovascular effects. The drug companies involved did not report those adverse effects because of lack of statistical significance in the original drug tests.

ASA panelists encouraged using alternative methods “that emphasize estimation over testing, such as confidence, credibility, or prediction intervals; Bayesian methods; alternative measures of evidence, such as likelihood ratios or Bayes Factors; and other approaches such as decision-theoretic modeling and false discovery rates.” However, any method can be used invalidly. “If success is defined based on passing some magic threshold, biases may continue to exert their influence regardless of whether the threshold is defined by a P value, Bayes factor, false-discovery rate, or anything else,” wrote panelist John Ioannidis, Ph.D., professor of medicine and of health research and policy at Stanford University School of Medicine in Stanford , Calif.

Some panelists argued that the P value per se is not the problem and that it has its proper uses. A P value can sometimes be “more informative than an interval”—such as when “the predictor of interest is a multicategorical variable,” said Clarice Weinberg, Ph.D., who was not on the panel. “While it is true that P values are imperfect measures of the extent of evidence against the null hypothesis, confidence intervals have a host of problems of their own,” said Weinberg. “If success is defined based on passing some magic threshold, biases may continue to exert their influence regardless of whether the threshold is defined by a P value, Bayes factor, false-discovery rate, or anything else.”

Beyond simple misinterpretation of the P value and the associated loss of information, authors consciously or unconsciously but routinely engage in data dredging (aka fishing, P-hacking) and selective reporting. “Any statistical technique can be misused and it can be manipulated especially after you see the data generated from the study,” Kramer said. “You can fish through a sea of data and find one positive finding and then convince yourself that even before you started your study that would have been the key hypothesis and it has a lot of plausibility to the investigator.”

In response to those practices and concerns about replicability in science, some journals have banned the P value and inferential statistics. Others require confidence intervals and effect sizes, which “convey what a P value does not: the magnitude and relative importance of an effect,” wrote panel member Regina Nuzzo, Ph.D.

How can practice improve? Panel members emphasized the need for full reporting and transparency by authors as well as changes in statistics education. In his commentary, Don Berry, Ph.D., professor of biostatistics at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, urged researchers to report every aspect of the study. “The specifics of data collection and curation and even your intentions and motivation are critical for inference. What have you not told the statistician? Have you deleted some data points or experimental units, possibly because they seemed to be outliers?” he wrote.

Kramer advised researchers to “consult a statistician when writing a grant application rather than after the study is finished; limit the number of hypotheses to be tested to a realistic number that doesn’t increase the false discovery rate; be conservative in interpreting the data; don’t consider P = 0.05 as a magic number; and whenever possible, provide confidence intervals.” He also suggested, “Webinars and symposia on this issue will be useful to clinical scientists and bench researchers because they’re often not trained in these principles.” As the ASA statement concludes, “No single index should substitute for scientific reasoning.”

A version of this article originally appeared in the Journal of the Nation Cancer Institute.

Featured image credit: Medical research by PublicDomainPicture. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Misinterpretation and misuse of P values appeared first on OUPblog.

September 5, 2016

Why does the Democratic Party want the Cadillac tax abolished?

The Democratic Party platform for 2016 repudiates a major provision of Obamacare – but no one has said this out loud. In particular, the Democratic Party has now officially called for abolition of the “Cadillac tax,” the Obamacare levy designed to control health care costs by taxing expensive employer health plans.

Tucked away on page 35 of the Democratic platform is this enigmatic sentence: “We will repeal the excise tax on high-cost health insurance and find revenue to offset it because we need to contain the long-term growth of health care costs, but should not risk passing on too much of the burden to workers.”

Even by the problematic standards of current political rhetoric, this statement is equivocal. This sentence avoids the popular term for the levy imposed by Internal Revenue Code 4980I, the excise tax on “Cadillac” health plans. This sentence does not disclose that President Obama advocated the Cadillac tax “on high-cost health insurance” as an important provision to control health care costs. This sentence promises to replace the revenue to be raised by repeal of the tax without specifying how that replacement will happen. This sentence pays nominal obeisance to the need to control health care costs even as it calls for repeal of the provision of Obamacare most directly designed to control such costs.

The only unambiguous thought expressed in this sentence is that the Cadillac tax on high cost health plans must go.

Since the Republican Party opposed the tax all along (and managed to delay implementation of the tax until 2020), the Democratic platform makes clear that there is now a bi-partisan consensus to abolish the Cadillac tax.

What neither party wants to admit is the larger implication of their opposition to the Cadillac tax: Neither party is willing to adopt serious, practical measures to confront the problem of our nation’s continually rising health care costs.

The background to the Cadillac tax is now well-known. Section 106 of the Internal Revenue Code excludes from employees’ gross incomes the value of their employer-provided health care insurance. Section 106 was adopted in an earlier age, before health care costs became a major national problem.

What neither party wants to admit is the larger implication of their opposition to the Cadillac tax.

Conservative and liberal commentators alike agree that Section 106 stimulates health care outlays by sheltering employees from the costs of their employer-provided health care coverage. These commentators generally acknowledge that the correct solution is to repeal Section 106, so that employees will report as income the health care premiums paid by their respective employers. This would sensitize employees to the costs of employer-provided health care coverage and thus force employees and employers to confront and control those costs.

Repealing or limiting Section 106 is a political nonstarter, the classic case of good policy which no elected official is willing to embrace. The Cadillac tax was adopted as an attenuated alternative to the repeal of Section 106. The tax (now delayed until 2020) will be triggered when an employer-provided health care plan costs more than $10,200 annually for individual coverage and $27,500 annually for family coverage.

The theory behind this tax is that employers will seek to avoid it by reducing their health care outlays below the levels triggering the tax.

The underlying political reality is that in theory most of us nominally favor reducing health care outlays, but few of us are willing to make the sacrifices necessary to do this. Reducing health care costs entails depriving someone of medical services they would otherwise receive or decreasing the compensation of medical care providers for the services they perform. Few politicians are willing to do undertake such unpleasant tasks.

Hence, our elected officials proclaim in the abstract their concern about health care costs but are unwilling to take practical steps to control those costs.

Given the bi-partisan opposition to the Cadillac tax as expressed in the Democratic Party platform, the tax will not go into effect. If our elected officials lack the courage to implement this modest measure to control health care costs, there is little prospect of more serious measures being adopted.

Featured image credit: medical appointment doctor by DarkoStojanovic. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Why does the Democratic Party want the Cadillac tax abolished? appeared first on OUPblog.

How much do you know about ancient Greek education?

It’s back-to-school time again – time for getting back into the swing of things and adapting to busy schedules. Summer vacation is over, and for many, it’s back to structured days of homework and exam prep. If we look back to ancient Greece, we see that life for schoolchildren did not always follow such set plans day-to-day. Greek education was less formal, and parents chose whether or not to send their children to particular educational programs.

While memorizing by heart the works of poets may no longer be a standard academic practice in modern Western society, key elements of Classical Greek education endure. Aristotelian logic, the Socratic method, and Plato’s academic skepticism are all still relevant in the classroom today.

Test how much you know about the ancient Greek education system that developed the minds of Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Archimedes, Pythagoras, Herodotus, and Hippocrates.

Quiz background image credit: “Akropolis” by Leo von Klenze. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image credit: “The School of Athens” by Raphael. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How much do you know about ancient Greek education? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers