Oxford University Press's Blog, page 469

September 5, 2016

Israel and the offensive military use of cyber-space

When discussions arise about the utility of cyber-attacks in supporting conventional military operations, the conversation often moves quickly to the use of cyber-attacks during Russia’s invasion of Georgia in 2008, the US decision not to use cyber-attacks in the 2003 invasion of Iraq, or Russia’s behavior in cyber-space surrounding the conflict with Ukraine that began in 2014. These, however, may not really be the most useful cases to examine. In these battles a world power faced a vastly weaker foe, and the outcome was never really in doubt as to who would triumph. By comparison, Israel, while militarily stronger than its individual neighbors, may be a far more valuable case to examine to assess how cyber-attacks can help support conventional military forces.

Israel has explicitly stated that it is ready and able to use cyber-weapons, though Israel did not make clear exactly what those weapons are or under what conditions they would be used. Nor has Israel confirmed or denied any particular actions it has taken or would take to decrease the chances of attacks or reprisals by others. Despite this, the evidence strongly suggests that Israel has cyber-weapons and has used them.

One particularly useful example is the Israeli strike on a Syrian nuclear reactor in 2007. (Israel, unsurprisingly, has not confirmed it took this action, but the evidence points to Israel). The Israeli Air Force was able to enter Syrian airspace, bomb the reactor, and leave Syria without ever being detected. A traditional way to accomplish such a mission would be to blind the air defense radars or shut them down, but this alerts guards that there is a problem, which would have likely led Syria to scramble jets, increasing the danger to Israeli pilots. Instead, Israel reportedly used a cyber-attack to trick the air defense system into thinking nothing unusual was happening while the attack was underway, while also ensuring guards were not alerted to the system’s capture. Their screens showed all was well. In doing this, Israel increased the chance its mission would succeed, and its pilots would emerge unharmed. Such a strategy could also be useful during a protracted war, as a means to conduct sneak attacks and ambushes.

Beyond targeting military facilities, cyber-attacks could support traditional military maneuvers by targeting critical infrastructure systems. If transportation systems, such a rail lines or airport control towers, are disabled it becomes more difficult to move soldiers and equipment to where they are needed. Taking down an electrical or communications grid could tilt the battlefield towards the attacker. These types of attacks appear to be ones Israel is pursuing.

Israel can potentially use cyber-attacks to its advantage, as it has the strongest cyber-capabilities in the Middle East.

In a case where two nations are facing each other and their militaries are of similar strength, cyber-attacks may provide one side with an edge. There is debate over the effectiveness of cyber-weapons, but between equally matched states, even a small effect might be enough to turn the course of the war. In fact, if used early on, a successful cyber-attack could signal the opposing state that it would lose in combat, perhaps leading to a negotiated solution or preventing hostilities. (The reverse danger exists in this scenario as the attack could escalate hostilities further.)

Israel can potentially use cyber-attacks to its advantage, as it has the strongest cyber-capabilities in the Middle East. The Stuxnet attack on Iran’s nuclear weapons program, allegedly by Israel and the United States, can be viewed as an attempt to use a cyber-attack in place of conventional military means. There are numerous advantages to using a cyber-attack instead of a conventional one. A cyber-attack can spread to previously unknown facilities linked to the original target. A physical strike would have been highly difficult to pull off and risky to Israeli military personnel. A cyber-attack is easier to deny, decreasing the dangers of a reprisal. This was a unique opportunity to achieve a military goal with minimal risk. How much damage the attack did is uncertain, but it was apparently enough to make Israel feel it did not need to launch a physical attack.

The geography of a nation may impact the importance a cyber-attack can play. In a large country like the US, Russia, China, or even larger European nations, a cyber-attack that has an impact on communications or defense systems for a day or two may be something the military can accommodate. In a geographically small state such as Israel (roughly the size of Wales or New Jersey), and which is also a state that relies on a reservist military, an attack that cripples such systems may be one that the state would struggle to recover from in the face of a full scale invasion.

There is ongoing debate regarding the potential of cyber-attacks to alter the balance of power in conventional military engagements. An examination of Israel’s experience provides useful insights. Israel has successfully used a cyber-attack in support of one military mission, and has used cyber-weapons in place of a military mission. There are dangers that cyber-attacks can pose, but also real opportunities for states willing and able to invest the resources.

Feature image credit: code by Ilya Pavlov. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Israel and the offensive military use of cyber-space appeared first on OUPblog.

How does international law work in times of crisis?

In preparation for the European Society of International Law (ESIL) 12th Annual Conference, we asked some of our authors to reflect on this year’s conference theme ‘How International Law Works in Times of Crisis’. What are the major challenges facing the field, and is international law effective in addressing these issues? What role do international lawyers play in confronting crises, both old and new? Ultimately, is international law itself in crisis?

* * * * *

When confronted with international problems, international lawyers instinctively look for multilateral solutions. In case of international crises, whether of the immediate or persistent variety, the multilateral process may not work well, however. Consent may not timely be obtained, or some states may unjustifiably drag their feet in the quest for a solution. Faced with these collective action problems, unilateral action may have to be taken by states, individually or collectively. Unilateralism may be frowned upon, but it may derive both its legality and legitimacy from the substantive goal which the acting state strives for – the elimination or mitigation of an internationally recognized crisis – in combination with proof that this crises somehow affects the acting state. Thus, when it is established that multilateral cooperation does not deliver in the face of crisis, states may for instance take unilateral trade restrictions to counter climate change or environmental degradation, they may extend their courts’ civil and criminal jurisdiction to hear cases of foreign human rights violations, or they may deny port access to vessels engaging in unsustainable fishing or marine pollution.

Cedric Ryngaert, Professor of Public International Law, Utrecht University, and editor (with Ige F Dekker, Ramses A Wessel, and Jan Wouters) of Judicial Decisions on the Law of International Organizations (OUP 2016).

* * * * *

International environmental law is, in many respects, born from crisis. In the absence of a standing and permanent international regulatory authority that has the power to promulgate laws that preserve, protect, or enhance the global environment, history repeatedly demonstrates that the global community convenes on an ad hoc crisis-by-crisis basis to confront those issues that garner the requisite level of political or popular attention. It seems to me that the international community’s ability to effect change via legally binding regulatory action turns on the immediacy of the environmental threat, the strength of the human health nexus, or the charismatic/sympathetic nature of the regulatory target. One example of a crisis that satisfied these criteria and led to an effective legal response is the depletion of atmospheric ozone. A second example is the legal moratorium on commercial whaling that was implemented in 1982.

Moving forward, the international community faces the daunting challenge of adapting this ad hoc approach to the many pervasive and multifaceted environmental threats of the twenty-first century. A group of scientists recently called for the International Commission on Stratigraphy to formally proclaim that we have entered a new geological epoch—the Anthropocene. The appropriateness of officially labeling the present moment in the geological timescale after human-induced change is debatable; however, the rapid and dramatic alteration to the atmosphere, the oceans, the Earth, life-giving ecosystem-services, and biodiversity is not. The seemingly intractable climate change dilemma may very well be international environmental law’s canary in the coalmine for the Anthropocene, signalling the inability of the traditional approach to international lawmaking to effectively confront current environmental crises. And, if so, it is apparent to me that we must meet this challenge with innovation, flexibility, and unprecedented commitment.

Dr. Cameron Jefferies, Assistant Professor and Borden Ladner Gervais Energy Law Fellow at the University of Alberta, Faculty of Law and author of Marine Mammal Conservation and the Law of the Sea (OUP 2016).

* * * * *

Demagogic leaders in two countries, Turkey and the Philippines, have recently spoken about introducing the death penalty. Both States are parties to the Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. The treaty does not allow denunciation. International law provides a big obstacle to them. In order to proceed, these States will have to openly defy international obligations that they have accepted. That they will do so cannot be ruled out. But will the Philippines – after its glorious victory in the South China Sea decision – really want to suggest that international law is insignificant or meaningless? Were Erdoğan and Duterte to proceed with their plans, it is unlikely that they would end up in an international court for defiance of the Second Optional Protocol. But international legal obligations will help frame the political debate inside the country. They will be an important and, hopefully, irresistible factor.

William A. Schabas, Professor of International Law, Middlesex University, and author of The International Criminal Court: A Commentary on the Rome Statute, Second Edition (OUP 2016).

* * * * *

International law and crises have a difficult relationship. Indeed, many of the long-standing changes in the regulation of international relations were born to respond to crises. The 1945 regime on the use of force, international human rights law and international refugee law are three of the most prominent examples. These changes, however, only emerged due to devastating, widespread and immediate crises on a global scale. Of concern is that this remains true today. The consequences of the Syrian conflict and the ensuing flight of its peoples, for example, are truly devastating and immediate. But they do not have widespread effects on a global scale. This has seriously undermined effective international law responses to the Syrian conflict by key players of international relations. The Syrian conflict shows us the relationship between international law and crises in its worst light. Responses to crises that do not have a truly transformative edge may undermine international law. Yet, we do not wish for a global crisis in order to better develop international law.

Başak Çali, Professor of International Law at Hertie School of Governance, Berlin and Director of Center for Global Public Law, Koç University, Istanbul, and author of The Authority of International Law: Obedience, Respect and Rebuttal (OUP, 2015).

* * * * *

The ability of international criminal law to meet the challenges of contemporary crises has been, and continues to be, mixed. In Kenya, the only option for accountability for the 2007-08 post-election violence was from the International Criminal Court. But due to a lethal combination of poor case construction by prosecutors and political interference in Kenya, all of the ICC cases have broken down. In Syria, international criminal justice has ran into a wall. Due primarily to geopolitical tensions, the ICC has no jurisdiction there and won’t be granted it any time soon. In the situations, modest successes in bringing perpetrators to account have been achieved. A hybrid tribunal has been set up to investigate and prosecute Kosovo Liberation Army leaders, the first time that the victors of a war will be the specific focus of a court. After years living freely in Senegal, Chadian dictator Hissène Habré was finally brought to justice this year. Former President of Côte d’Ivoire Laurent Gbagbo is on trial for crimes against humanity at The Hague, while his wife and former first lady Simone Gbagbo faces similar charges in Abidjan.

What is crystal clear is that the justice on offer today isn’t enough. The demand for accountability for international crimes far outweighs its supply. International criminal justice continues to be pursued on an ad hoc basis. What has been achieved thus far pales in comparison to what needs to be done if international criminal law is to effectively meet the crises we face today — as well as the expectations of victims around the world.

Mark Kersten, Researcher, Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto, and author of Justice in Conflict: The Effects of the International Criminal Court’s Interventions on Ending Wars and Building Peace (OUP 2016).

* * * * *

For more articles on this year’s ESIL conference theme, please explore our Journals Collection. We have worked with editorial teams of more than ten international law journals to draw together a collection of recent papers addressing this theme. The papers are free to read online in advance of the discussions, or after the close of the conference, until 15 October, 2016.

To stay connected throughout the conference, you can follow us on Twitter @OUPIntLaw and like our Oxford International Law Facebook page.

See you in Riga!

Featured image: 32473-Riga by xiquinhosilva. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post How does international law work in times of crisis? appeared first on OUPblog.

September 4, 2016

Identity, foreign policy, and the post-Arab uprising struggle for power in the Middle East

In recent years, there has been a greater emphasis put on understanding the international relations of the post-Arab uprising in the Middle East. An unprecedented combination of widespread state failure, competitive interference, and instrumentalization of sectarianism by three rival would-be regional hegemons (Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and Iran) in failing states has produced a spiral of sectarianism at the grassroots level.

According to May Darwish, Saudi Arabia’s policy reflects ontological insecurity, as well as perceived threats to its distinctive identity as leader of the Islamic umma from Iran and from the trans-state Muslim Brotherhood Movement, particularly when the latter briefly came to power in Egypt and Tunisia. In regard to Pan-Arabism, rivalry for leadership within an identity community can be as intense as inter-communal conflicts, and this is currently the case within Islam. Against Iran’s revolutionary and republican Islam, which denied the legitimacy of Saudi conservative “American” and monarchic Islam, the Saudis responded with sectarian discourse depicting Shias as unbelievers, aimed at making Iran unentitled to leadership of the Muslim world. The threat of the Muslim Brotherhood, a mass-based Islam, to the legitimacy of the Saudi family-state’s top-down Islam, was countered by propagation of a Salafist Islam submissive to authority.

William Anthony Rivera shows how Iran’s political identity centres on resistance to US imperialism, seen by Iranian political elites as a matter of honour. External sanctions and threats seeking to raise the costs of defiance over the nuclear program were less effective than a rational choice perspective would anticipate because the US attempt to single out and deprive Iran of its rights under the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) struck at Iran’s sense of honour. Since success in intra-elite competition depended on defending the honour of the country, Iranian elites who made any concessions in the nuclear negotiations were vulnerable to charges of selling out the national honour. Once a standard of honour is constructed, even if done purely instrumentally, it becomes a constraint on policy innovation.

At the regional level, Iran was a contender for regional hegemony as leader of a “resistance axis,” including Syria, Hamas, and Hezbollah, against the United States and its regional allies, led by Saudi Arabia. Riyadh saw the power balance shifting toward Iran, first by the US invasion of Iraq which opened the door for Iran’s Shia clients to assume power in Baghdad, then by the 2013 nuclear deal that allowed Iran out of international isolation. Yet, the outbreak of the uprising against Iran’s Syrian ally, Bashar al-Asad, gave the Saudis the chance to replace him with a Sunni regime and thereby break the Resistance axis. The instrumentalization of Sunni sectarianism in Syria by Iran’s rivals empowered Sunni jihadists against whom Iran mobilized its own Shia non-state clients, above all Lebanon’s Hezbollah.

Middle East Map by ErikaWittlieb. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

Middle East Map by ErikaWittlieb. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.Turkey, the third aspirant hegemon was the initial main beneficiary of the Arab uprising as Muslim Brotherhood branches having ideological affinity with Ankara’s ruling AKP, empowered by their electoral prowess and grassroots social infrastructure, formed the government in Tunisia, Egypt, and Morocco. Turkey projected soft power among the newly democratizing Arab states as an economically successful democracy that accommodated Islam. However, Turkey’s regional standing was damaged by its involvement in the conflict in Syria, where it’s backing of the Muslim Brotherhood as a replacement for Asad in Damascus stood to advance its regional hegemony. Then, as Asad proved resilient, Turkey supported the more militarily effective jihadi movements, including the al-Qaida avatar, Jabha al-Nusra and what became ISIS. Its discourse and image were transformed from that of a democratic to a Sunni sectarian power.

Kose et al. and Ciftci et al. analyze 2012 opinion surveys to measure the outcome of the ideational battle for regional hegemony—the comparative “soft power” of the rival states. Before the uprising, the Iran-led resistance bloc had put the US-aligned Sunni powers, notably Egypt and Saudi Arabia, on the defensive in Arab public opinion as anti-Americanism was inflamed by the invasion of Iraq and anti-Israeli sentiment was stoked by the Lebanon and Gaza wars. They responded with sectarian discourses depicting Iran as Shia and anti-Arab but this found little resonance at the grassroots level. However, the post Arab uprising conflicts made people far more receptive to rival powers’ instrumentalization of sectarianism, encouraging a big surge in sectarian animosity at the grassroots level. Surveys found that, with some exceptions, religious identities predicted foreign policy attitudes: Sunnis backed Saudi Arabia and Turkey and opposed Iran while Shias supported Iran’s but not Saudi or Turkish roles in the region. Dramatically, Shia Hezbollah lost much of its soft power in Sunni regional opinion owing to its defense of the Syrian regime’s repression of mostly-Sunni protestors. Since Sunnis were the numerical majority, this shifted the ideational power balance against Iran.

These studies underline the importance of identities in the IR of the Middle East in shaping behaviour and as instruments in the power struggle. The three rival regional powers posed little military threat to each other and their conflict was waged by proxy wars in failed states. While hard power—guns and money—mattered in these conflicts, recruitment to armed movements like ISIS and Hezbollah depended to a considerable extent on sectarian ideology. And the outcome of proxy wars mattered because it was seen to shift the ideational more than the material balance of power. This balance was intimately linked to the legitimacy, hence the survival, not of states, but of rival regimes. Thus, in defending identity, regimes also defended their interests—and identity discourse was as powerful as guns and money in the Middle East and North Africa regional power struggle.

Featured image credit: City-traffic-Iran-tourism-cityscape-sky by hashem. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Identity, foreign policy, and the post-Arab uprising struggle for power in the Middle East appeared first on OUPblog.

The body politic: art, pain, and Putin

The phrase ‘scrotum artist’ was never going to be easy to ignore when it appeared in a newspaper headline. It is also a phrase that has made me reflect upon the nature of politics, the issue of public expectations, and even the role of a university professor of politics. In a previous blog post I reflected on the experience of running a citizens’ assembly and how the emotional demands and rewards of the experience had been quite unexpected. ‘Raw politics’ was the ‘headline’ phrase but now I cannot help but wince with embarrassment when I think about this phrase. ‘Wince’ being the apposite word given the manner in which the Russian political artist and protestor, Pyotr Pavlensky, nailed his scrotum to the cobblestones of Red Square and sat there naked until the authorities arrested him.

This, it appears, was just the latest in a series of art installations by Pavlensky in which he uses his body to symbolise not only the abuses committed by the Russian state, but also as a symbolic sign of taking back control, in light of the authorities’ constant attempts to impose restrictions on personal freedom. Not surprisingly Pavlensky’s mother is somewhat bewildered by her son’s disturbing artistic interventions; while others praise him for pushing the boundaries of political protest in an attempt to expose the state of oppression under Putin. The intervention with the nails and his scrotum were just the latest in a series of subversive acts. In 2012 a project entitled ‘Seam’ saw Pavlensky sewing his lips shut with garden twine in order to protest at the jailing of Pussy Riot. In May 2013 a project called ‘Carcass’ saw Pavlensky naked, wrapped in layers of barbed wire, and dumped motionless and powerless at the main entrance to the Legislative Assembly of Saint Petersburg. The more the confused policemen attempted to untangle and remove him, first by putting a blanket to hide the horror then attacking him with wire cutters, the more Pavlensky was gashed and cut by the self-imposed net. If this were not enough, in October 2014 he sat naked on the perimeter wall of the Serbsky Centre, a psychiatric hospital used in Soviet times to imprison dissidents, and cut off his right ear lobe with a kitchen knife, in order to protest at the political abuse of psychiatry in Russia.

‘I’m perfectly sane and that’s been widely proven’ Pavlensky responds to anyone who questions his mental health. ‘To seek to dismiss me as a madman is exactly what would suit the state’. And yet the power of his art to shame and harass, to expose and discredit, cannot be so easily dismissed. His performances are filmed, photographed, and receive growing global attention. ‘Art has the power to send a message other mediums like the media have long lost’, Pavlensky states, ‘It’s my way of resisting and I have no intention at all of giving it up’. Now that’s what you really call raw politics!

Featured image credit: Red Square, Moscow by flowcomm. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post The body politic: art, pain, and Putin appeared first on OUPblog.

A look at historical multiracial families through the House of Medici

The Medici, rulers of Renaissance Florence, are not the most obvious example of a multiracial family. They’ve always been part of the historical canon of “western civilization,” the world of dead white men. Perhaps we should think again. A tradition dating back to the sixteenth century suggests that Alessandro de’ Medici, an illegitimate child of the Florentine banking family who in 1532 became duke of Florence, was the son of an Afro-European woman. Sometimes called Simunetta, she may have been a slave in the household of his grandmother Alfonsina Orsini de’ Medici. The historical sources are elusive, but by pursuing them we can learn much about the history of race.

It’s easy to get the impression that mixed-race families are a new phenomenon. Pew Research Center reported last year that 6.9% of US adults are multiracial, and that the numbers are growing. In Britain the numbers are also growing, though smaller overall (2%) and one in 10 UK couples is of mixed ethnicity.*

Historical and archaeological research, however, shows that mixed-race families have been around very much longer. For example, there was a significant presence of first-generation migrants from North Africa in Roman Britain. Medieval records explored by the England’s Immigrants 1350-1550 project are largely “colour-blind,” but there is other evidence for both black Africans and North African “Moors” in medieval England. It would be surprising indeed if none of these people had had children. Elsewhere in Europe, African migration—both voluntary and forced—was significant too. The retinue of Emperor Frederick II, thirteenth-century ruler of Germany and Sicily, included black Africans. Ethiopian Christians travelled to Europe: some became monks at Santo Stefano in Rome. From the fourteenth century, St Maurice was often depicted as black in German art.

Although many details regarding the birth of Alessandro de’ Medici remain uncertain, it is believed that his mother may have been a slave in the household of his grandmother. Image by Art Gallery ErgsArt. Public Domain via Flikr.

Although many details regarding the birth of Alessandro de’ Medici remain uncertain, it is believed that his mother may have been a slave in the household of his grandmother. Image by Art Gallery ErgsArt. Public Domain via Flikr.In the fifteenth century, the beginning of the Portuguese trade in enslaved Africans gave a new and traumatic dynamic to this world. Slavery was already a part of the social fabric in Mediterranean societies, but in early fifteenth century Italy, many slaves came not from Africa, but from the East. Cosimo “the Elder” de’ Medici (1389-1464), had an enslaved Circassian mistress named Maddalena. Their son, Carlo, was born around 1428. Brought up with Cosimo’s legitimate heirs, he had a career in the Church and helped pave the way for later Medici sons to become cardinals.

In the frescos painted in the middle of the fifteenth century for the chapel in Palazzo Medici, a black African archer is shown prominently alongside a procession of Florentine dignitaries. By the beginning of the sixteenth century, Africans were a much larger proportion of the enslaved population in Italy, particularly in Naples, hometown of Alessandro de’ Medici’s grandmother Alfonsina.

There is still a battle, though, to bring this European history to the public. It took an American museum, the Walters, to put together the first major exhibition on the African Presence in Renaissance Europe. Race is almost absent as an issue from the museums of Florence (and indeed Italy), whether the period is the Roman Empire, the Renaissance or the twentieth-century imperialism of Mussolini.

A part of the difficulty here is the way the Renaissance is packaged and sold. This is a glamorous world of art and luxury—and, yes, of violence, but of the dramatic Borgia-style vendetta not the institutionalised systems of oppression. You might say the same of British country houses, where the Downton Abbey image leaves little space for their connection to the profits of slavery or Empire. There has been some positive work on this front recently, for example at Kenwood House, which in the eighteenth century was home to a biracial woman, Dido Elizabeth Belle (subject of a recent film by Amma Asante, which deserves wider public attention). Such developments are largely thanks to the efforts of community activists and the provision of public funding to engage a wider range of audiences. There is a long way to go, particularly in the privately-owned heritage sector.

But everyone wants a history, and perhaps one consequence of the growing number of mixed-race families in the twenty-first century will be a growing interest in such families in the past. This is far from an easy issue. All too often these family histories are entangled with enslavement and Empire, with violence and with deep inequalities of power. In my own family tree I find twelfth-century Jewish migrants to England on one side, and twentieth-century British missionaries in India on another. I always knew they were there, but writing The Black Prince of Florence has made me think anew about questions of race and ethnicity in my own past, as well as in the lives of others.

* The UK research differentiates between certain white ethnicities.

Featured image credit: “Medici Chapel roof” by virtusincertus. CC BY 2.0 via Flikr.

The post A look at historical multiracial families through the House of Medici appeared first on OUPblog.

Philosopher of the month: Aristotle

This September, the OUP Philosophy team honors Aristotle (384–322 BC) as their Philosopher of the Month. Among the world’s most widely studied thinkers, Aristotle established systematic logic and helped to progress scientific investigation in fields as diverse as biology and political theory. His thought became dominant during the medieval period in both the Islamic and the Christian worlds, and has continued to play an important role in fields such as philosophical psychology, aesthetics, and rhetoric.

More is known about Aristotle’s life than many other ancient philosophers. Born in 384 BC, Aristotle’s parents were both members of traditionally medical families. His father died when Aristotle was fairly young, and Aristotle probably grew up at the family home in Stagira, in the Chalcidice region of northern Greece. At the age of about seventeen or eighteen, Aristotle was sent to school in Athens at Plato’s Academy, where he quickly made a name for himself as a student of great intellect, acumen, and originality. Aristotle remained at the Academy nearly twenty years, until Plato’s death in 348 or 347. He then relocated to Asia Minor, where he spent some years devoted principally to the study of biology and zoology. In 343 he moved to Pella, where he served as tutor to King Philip’s son, the future Alexander the Great. Aristotle returned to Athens, where for the next decade he engaged in teaching and research at his own school in the Lyceum. He fled from Athens to Chalcis on the death of Alexander, and died a year later in 332.

Aristotle was a tireless collector and organizer of observations and opinions, and analyzed his data with a critical eye. He introduced innovative technical terms, and proposed highly original philosophical theses, and was strongly committed to rational argument. Building his case step by step, Aristotle’s writings often proceed dialectically, presenting the positions of those that he disagrees with as clearly as he can, then refuting them point by point in detail. Always careful to survey the views of reputable thinkers who had approached a problem, Aristotle was the first Greek thinker to make engagement with the books of others a central part of his method. The extant works that comprise the Aristotelian corpus address a broad range of subjects, including logic, epistemology metaphysics, nature, life, mind, ethics, politics, and art.

Aristotle was concerned with the preservation of knowledge of the diverse world we live in. His ethics, which he regarded as a branch of the natural history of human beings, demonstrates an appreciation of complex human motivations. Aristotle, like Kant, had an interest in categories, setting forth both the division of the sciences we continue to use, and the categories that have organized almost all subsequent philosophical thought. He avoids all extremes, and typically does justice to each side of the divisions that split philosophers into warring camps. Many of Aristotle’s works became staples of instruction during the Roman imperial period, and again in the Byzantine period. Translated into Arabic and Latin, they were the intellectual focus of the late medieval period in western Europe, and an inspiration to the great period of Islamic philosophy. Even in the twenty-first century, Aristotle’s organization of what is known and his approach to adding to knowledge are major parts of the intellectual universe.

Featured image: Reconstruction of the Acropolis and Areus Pagus in Athens (1846) by Leo von Klenze. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Philosopher of the month: Aristotle appeared first on OUPblog.

September 3, 2016

When to talk and when to walk

In the spring of 2014, after Russia annexed the Crimea, the German chancellor Angela Merkel took to the air. She jetted some 20,000 km around the globe, visiting nine cities in seven days – from Washington to Moscow, from Paris to Kiev – holding one meeting after another with key world leaders in the hope of brokering a peace-deal. Haunted by the centenary of 1914, Merkel saw summitry as the only way to stop Europe from “sleepwalking” into another great war.

Face to-face encounters at the highest level clearly still matter, even in our age of email and Skype, cellphones and video-conferencing. The word ‘summit’ came from Churchill in 1950. But arguably the desire of leaders to meet is almost innate. Having made it to the top of their own political system, they yearn for new challenges and relish the chance to compete on the world stage. Tired of the dank foothills of domestic politics, these new statesmen and women now set their sights on the peaks of global affairs where the air seems clear and heady.

The classic decades for Cold War summitry were the 1970s and 1980s. In 1972, Richard Nixon made pioneering visits to the capitals of the communist world, Beijing and Moscow, ushering in an era of détente between ideological antagonists who had previously treated the Cold War as a zero-sum game: ‘I win only if you lose.’ In Europe, the encounters between Willy Brandt of West Germany and Willi Stoph of East Germany in 1970 were similarly path-breaking, opening the way to ‘de facto’ mutual recognition. These summits were not only matters of policy and deals; they were journeys of reconnaissance in cross-cultural relations. Ideological foes often seem like alien forces but summitry can help in what we call “de-othering” the “other” and thereby initiate a process of rapprochement.

President Reagan’s first meeting with Soviet General Secretary Gorbachev at Fleur D’Eau during the Geneva Summit in Switzerland, 19 November 1985. Photo by White House Photo Office. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

President Reagan’s first meeting with Soviet General Secretary Gorbachev at Fleur D’Eau during the Geneva Summit in Switzerland, 19 November 1985. Photo by White House Photo Office. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Once bridges have been built, they need constant maintenance through regular communication. In the late 1970s, the West German chancellor Helmut Schmidt was an avid practitioner of what he called ‘Dialogpolitik.’ Schmidt argued that a leader must always try to put himself in the other guy’s shoes in order to understand their perspective on the world and construct compromises that are viable. For this reason he favoured informal summit meetings to exchange views privately and candidly, rather than grand choreographed occasions that played to the media gallery. In our own day US Vice-President Joe Biden has adopted a similar approach to diplomacy, stressing the need to gauge the other guy’s “bandwidth” by building personal relationships, so that you can “make more informed judgments about what they are likely to do or what you can likely get them to agree not to do.”

Sometimes summitry can be truly transformative. After the ‘New Cold War’ of the early 1980s, the four superpower summits between Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev in 1985-8 generated a chain-reaction that cut nuclear arsenals, helped defuse the Cold War, and inaugurated an era of genuine cooperation between USA and the USSR. This culminated in their unprecedented partnership during the first Gulf War of 1991, when President George H.W. Bush spoke headily about ‘A World New Order.’ Meanwhile, the European Cold War was transcended not merely by the East European revolutions of 1989 but through the peaceful unification of the two Germanies in 1990. This historically incredible feat can be attributed in large measure to the cooperation between Bush, Gorbachev, and Helmut Kohl, the West German chancellor, who used summitry to settle the ‘German Question’ via international agreement.

The ‘transformative summitry’ of 1985-91 depended on a creative tension between change and stability. Americans and Russians were no longer ideological antagonists – the Bush-Gorbachev summit at Malta in 1989 reflected a new spirit of entente based on what they called shared ‘democratic’ and ‘universal’ values – yet the USA and USSR were still the pre-eminent superpowers and, as such, the two pillars of global order. But after the Soviet Union broke apart at the end of 1991 and the bipolar framework collapsed, this essential stability had gone.

In the 1990s, Americans luxuriated in their status as ‘sole superpower’ – expressed in their unique capacity for military power-projection worldwide and in a ‘New Europe’ built around an enlarged EU and NATO reaching right up to the borders of Russia. This is the edifice the Kremlin has sought to challenge in recent years. Indeed, after the economic implosion and political chaos of the Yeltsin years, Moscow’s sense of marginalization in world affairs generated a widespread desire to revive Russia as a great power. Since Vladimir Putin took command, this has been his prime objective – with Syria, Ukraine, and Crimea as today’s flash-points. Many pundits now ask whether the Cold War has returned, especially after the June 2016 Warsaw summit when NATO committed itself to the unprecedented deployment of Allied forces in Poland and the Baltic states.

And here’s where we return to Merkel and summit diplomacy. The German Chancellor’s approach has been carefully balanced: insistent on maintaining a strong NATO military posture while also emphasizing the need to keep open lines of communication with Putin. Merkel is surely right. The history of the 1970s and 1980s shows that there is always a delicate balance to be struck between dialogue and defense – deciding when to reach out and when to stand tall, when to talk and when to walk.

So summitry involves nerve-wracking judgement-calls for leaders: it requires hard calculations about opportunity, timing and personality – as challenging in the era of Merkel and Putin as in the days of Nixon and Brezhnev or Reagan and Gorbachev. Parleying at the summit is a matter of vision and skill, nerve and guts. Yet for those who are successful there is, perhaps, the chance to become a Maker of History. Here lies the perennial and fateful attraction of summitry.

Feature image credit: German Chancellor Angela Merkel points to a badge on Russian President Vladimir Putin’s lapel in Heiligendamm, G8 Summit 2007. Photo REGIERUNGonline / Kühler via The Press and Information Office of the Federal Government of Germany.

The post When to talk and when to walk appeared first on OUPblog.

Two Williams go to trial: judges, juries, and liberty of conscience

On this day in 1670: a trial gets underway:

“The question is not whether I am guilty of this indictment, but whether this indictment be legal.” (William Penn, 3 September 1670)

The two defendants had been arrested several weeks earlier while preaching to a crowd in the street, and charged with unlawful assembly and creating a riot. Their trial, slated to begin on 1 September, had been pushed back to 3 September after preliminary wrangling between the judge and the defendants. And so on this date – 246 years ago today – the defendants were called before the bench. They were an unlikely pair, in some ways: the firstborn son of an English knight and naval hero, a month shy of his twenty-sixth birthday, who had studied at (and been ejected from) the most prestigious college in England; and a wealthy London merchant, sixteen years his senior. But by the end of the year, due in large part to the events of the next two days, William Penn and William Mead would become leading spokesmen for the Society of Friends (Quakers) and nationally-known figures in the movement for liberty of conscience, representative institutions, and the rule of law.

The trial was contentious before it even began: as they approached the bench on the morning of 3 September, Penn and Mead found themselves fined for refusing to remove their hats before they had even spoken a word. (Quakers considered doffing the hat to mere humans inappropriate, a gesture that deprived God of the ultimate honor due Him.) During the proceedings, Penn continually objected that the charges were unjust and contrary to English law; he was eventually ejected from the courtroom altogether. Mead continued to object until he, too, was ejected. Despite repeated threats from the judge, and despite being denied food and a toilet all night (at least according to the defendants), the jury found Penn and Mead not guilty, whereon its members were fined for refusing to convict. Penn and Mead, though acquitted, were returned to jail on contempt charges stemming from their refusal to remove their hats at the outset of the trial. Penn’s release came a week later, his fines paid by family or friends so that he could be home with his dying father.

Admiral Sir William Penn by Peter Lely (1618-1680). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Admiral Sir William Penn by Peter Lely (1618-1680). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.What followed after the trial is arguably as important as what happened during the trial. A purported transcript – entitled The Peoples Ancient and Just Liberties Asserted – appeared shortly after the conclusion of the trial and went through nine printings in the last three months of 1670 alone (with additional printings in 1682, 1696, 1710, and 1725). Though it is a transcript of sorts, Peoples’s presentation of Penn and Mead is clearly a stylized and heroic construction, a morality play in dramatic form, complete with stage directions and narrative insertions, aimed at presenting the defendants as courageous Dissenters railroaded by a persecuting state-church system. It is a work of political theory and political theater that articulates a politics of dissent against arbitrary authority, of clear written law against prosecutions built on vague charges, and of juries as defenders of popular liberties against power-hungry judges. Its publication and ensuing popularity marked William Penn’s emergence as a new voice in the world of English Dissent.

The early modern courtroom was a far cry from our contemporary version of that institution, and it lacked many modern “hallmarks” like the presumption of innocence, exclusion of hearsay evidence, guarantees of defense counsel, the burden of proof on the prosecution, defendants’ right to silence. The judge in the case was none other than Sir Samuel Starling, the Lord Mayor of London. Verbal abuse was part and parcel of the court’s interactions with the defendants. “You are a saucy fellow,” the court Recorder told Penn, at other times calling him “impertinent,” “pestilent,” and “troublesome.” Mead too was berated by the court, with the Lord Mayor insisting, “You deserve to have your tongue cut out.” On the other hand, the guarantee of jury trials was a key element of British common law, dating back to Magna Carta. Although the charge against Penn and Mead was not explicitly religious in nature, the two made the fact that their “riot” was actually a religious assembly a central theme of their defense. In the end, the defendants turned a common law indictment for disturbing the peace into a wholesale attack on the persecuting English church-state, which violated the rights of conscience and branded pious believers as criminals.

Although they lost in the courtroom in September 1670, Penn and Mead emerged as leading figures in English politics over the next three decades: Mead as a prominent Quaker spokesman, Penn as the founder of an American colony dedicated to the principles of religious toleration. The Penn-Mead trial is commonly cited as among the most significant in the Anglo-American tradition, although many of these accounts admit that the significance of the case was due less to the two 1670 defendants than to what is widely known as ‘Bushel’s Case.’ In that case, named for one of the fined Penn-Mead jurors, Chief Justice Sir John Vaughn voided the fines that the court had imposed on the jurors, and defended their autonomy to arrive at their own verdicts based on the evidence presented to them. That was all in the future, of course, on 3 September, 1670, as the Penn-Mead trial prepared to begin in earnest.

Featured image credit: William Penn & William Mead plaque at the Old Bailey by Paul Clarke. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Two Williams go to trial: judges, juries, and liberty of conscience appeared first on OUPblog.

What academia owes Jane Addams

Jane Addams is perhaps best known as Hull House activist, recipient of the 1931 Nobel Peace Prize, and forbearer of modern social work, as well as being a founding member of both the NAACP and the ACLU. Underappreciated, however, is her central role in the development of American Pragmatism and contemporary social inquiry methodology. Until the 1990s, when feminist philosophers and historians began working to recover her role in the development of pragmatist thought, her philosophical work was primarily mapped onto traditional nineteenth century gender role stereotypes and ignored. Male philosophers including Dewey, Williams, James, and Mead were seen as providing the original thought, while Addams brilliantly administered their theories. As contemporaries they reflected classic archetypes of gender: male as mind, thinking and leading; and female as body, experiencing, caring, and doing. Yet Addams was far more than a competent technician following the lead of male intellectuals. Dewey and Addams, in particular, were close colleagues and lifelong friends. Addams published a dozen books and more than 500 articles: essays on ethics, social philosophy, pacifism, and social issues concerning women, industrialization, immigration, urban youth, and international mediation. This body of work exemplifies the hallmarks of American Pragmatism: an interplay of experience, reflection, and action for the common good.

American social reformer, Jane Addams (1860-1935) by Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

American social reformer, Jane Addams (1860-1935) by Library of Congress. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Addams’ influence on American Pragmatism is clearly reflected in contemporary social work scholarship and practice. Addams shared with Dewey and other pragmatists an action-oriented approach to knowledge acquisition and theory building that became the bedrock of contemporary social work scholarship. From a pragmatist’s perspective, we come to know the world through our experiences and actions in the world. Overt action in combination with reflection is necessary for acquiring knowledge. In short, we can test our ideas, concepts, and theories only by carrying out rational actions that follow from them and observing whether these actions result in expected outcomes. Yet Addams not only philosophized, she lived an action-oriented approach to knowledge in the pursuit of social justice. Likewise, contemporary social workers focus their practice and scholarship on addressing complex social issues such as poverty, disability, and oppression. A central tenet of pragmatism is that philosophy should address problems of the current social situation. Addams shared with other pragmatists commitments to democracy, freedom, and equality. Addams’ pragmatism, however, was arguably more radical than that of her male counterparts. Pragmatist tenets support critiques of gender, race, and class oppression, but it was Jane Addams who consistently brought oppression to the fore. From the outset, Addams theorized about her Hull House experiences addressing topics not typical of philosophical discussions such as garbage collection, immigrant folk stories, and prostitution; eventually extending her analyses to issues of race, education, and world peace.

The intellectual legacy of Jane Addams is also reflected in contemporary social science research methodology, especially mixed methods approaches increasingly used in nursing, public health, education, and social work, among other fields. Mixed methods inquiry is the intentional integration of qualitative and quantitative approaches to research in order to enhance the understanding of complex social phenomena. It combines the depth and contextualization of qualitative with the breadth of quantitative approaches. Fundamental to mixed methods research is the respectful engagement with differences including bringing to the fore voices that have been silenced, such as those of individuals living in poverty or with disabilities, or scholars pioneering alternative social inquiry methods. Contemporary mixed methods researchers address complex issues of human struggle with racism, poverty, illness, disability, and oppression through a back-and-forth conversation between micro and macro levels of analysis. The issues that concern us, like those that concerned Jane Addams, often involve specific individuals, groups, or communities embedded within macro level sociopolitical, economic, and cultural contexts. Indeed, the problems confronted by contemporary helping professionals are excellent candidates for mixed methods inquiry, the philosophical foundations of which were laid in the 19th century by Jane Addams and her colleagues.

Featured image credit: Hull House at the University of Illinois at Chicago by Zagalejo. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What academia owes Jane Addams appeared first on OUPblog.

September 2, 2016

Esperanto, chocolate, and biplanes in Braille: the interests of Arthur Maling

The Oxford English Dictionary is the work of people: many thousands of them. In my work on the history of the Dictionary I have found the stories of many of those people endlessly fascinating. Very often an individual will enter the story who cries out to be made the subject of a biography in his or her own right; others, while not quite fascinating enough for that, are still sufficiently interesting that they could be a dangerous distraction to me when I was trying to concentrate on the main task of telling the story of the project itself. If I had included pen-portraits of them all, the book would have become hopelessly unwieldy; I have said as much as I can about many of them, but in many cases there is more to be said. One of those about whom I would have liked to say more is Arthur Thomas Maling, who worked as one of James Murray’s assistants for nearly thirty years, and who went on working on the Dictionary for another dozen years or so after Murray’s death in 1915.

I have rather a soft spot for Maling, probably because of the various things we have in common, in addition to the simple fact of both having worked in-house on the OED for many years. Like me, he studied mathematics at Cambridge; like me, he worked on some of the largest entries in the Dictionary—including the verb “put,” on which he spent several months in 1909, just as I did when revising the same entry nearly a century later—and, like me, he was both a keen pianist and a lover of chocolate: two facts for which we have unexpectedly clear documentary proof, as we shall see. He was one of the longest-serving of all the lexicographers who worked on the first edition of the OED; and, as the work seems to have left him little time or energy for other things that might have made his name, he remains a very little-known figure. But I have become fond of him: fond enough to want to find out what I could about him.

Maling and the OED

There have been Malings in the Hertfordshire town of Royston since the 17th century. Arthur was born there in 1858, the son of a corn and seed merchant, who it seems fell on hard times soon afterwards—he is described as “out of business” in the 1861 census—and who in fact died in 1862, leaving a widow to bring up Arthur and his little sister Fanny. Further misfortune followed in 1870 when their mother died. Despite these difficult circumstances, Arthur managed to be admitted to Cambridge in 1878, and obtained his BA in mathematics five years later.

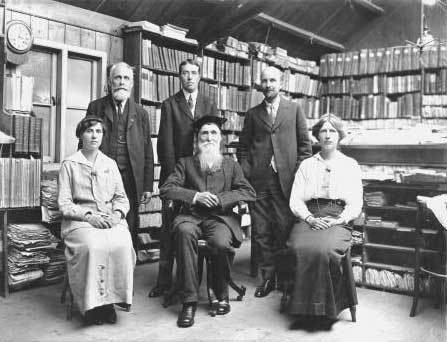

James Murray photographed in the Scriptorium on 10 July 1915 with his assistants: (back row) Arthur Maling, Frederick Sweatman, F. A. Yockney, (seated) Elsie Murray, Rosfrith Murray. Used with permission.

James Murray photographed in the Scriptorium on 10 July 1915 with his assistants: (back row) Arthur Maling, Frederick Sweatman, F. A. Yockney, (seated) Elsie Murray, Rosfrith Murray. Used with permission.In 1885 the OED’s first Editor, James Murray, moved to Oxford with his large family, as did some of the rather smaller group of assistants who worked at the Dictionary alongside him. For the first six years of his Editorship, Murray had been based at Mill Hill, then a village just outside London, where he somehow managed to combine the work with a position as a schoolmaster. The move to Oxford was followed by a search for new assistants, and Maling was one of those who expressed interest in the work. He joined Murray’s team early in 1886, and soon proved a valuable addition to the staff. His studies at Cambridge made him well qualified to deal with the vocabulary of that subject; and his musical knowledge—although he was no more than an amateur—seems to have been a valuable contribution to the pool of skills that the Dictionary’s compilers could share with one another (just as we do today). He certainly drafted the text of more than his fair share of mathematical and musical terms. He was also keen to recruit others to help with musical vocabulary: the Musical Times of July 1896 reproduced a letter from him—which must have been written with the approval of James Murray—appealing for “Musical Contributors to the English Dictionary,” who could “do their part in […] making the Dictionary as complete and accurate as possible” by supplying quotations illustrating musical words in use.

In addition to his knowledge of these subject areas, Maling seems to have had a particular flair for words that pose the most formidable challenges for a lexicographer. His work on “put” in 1909 has already been mentioned, but before this he also tackled verbs like “have” and “know,” which have a claim to be even more difficult to analyse and describe. And then there are the “function words”: words whose main function is to express grammatical or structural relationships between other words, rather than conveying meaning. Among the function words which Maling tackled were “that” and “the.” The word which James Murray once singled out as the most difficult in the entire Dictionary was “of”; and for the editing of this entry he was able to draw on a detailed preliminary analysis—covering several sheets of foolscap—prepared for him by Maling. Following Murray’s death in 1915 Maling transferred to the staff working under Charles Onions, the Dictionary’s fourth Editor; this led to his working on another challenging group of function words—the various pronouns and interrogatives beginning with “wh-“. He also did some work for Henry Bradley in relation to musical and mathematical words.

Uncovering Maling’s varied interests

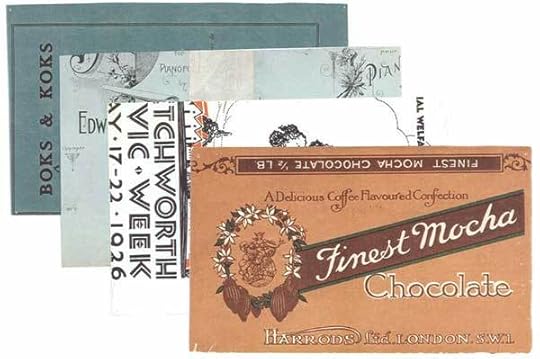

Our knowledge of Arthur Maling’s varied interests beyond his Dictionary work is mainly due to his practice of using waste paper of his own as slips on which to write his definitions and quotations: a practice which seems to have been generally encouraged during the First World War, when paper was scarce, but which Maling continued during the remainder of his employment on the Dictionary. It is through this habit of recycling that we know about Maling’s fondness for chocolate: among the slips of paper used for his work in W are the wrappers for at least five different varieties. He also enjoyed Horlick’s Malted Milk Tablets (or at least had a plentiful supply of wrappers). Other slips have been cut up from the covers of piano music scores, from which it seems reasonable to infer that he was a keen pianist.

Mailing enjoyed Horlick’s Malted Milk Tablets, as suggested from the plentiful supply of wrappers he recycled. Photo used with permission.

Mailing enjoyed Horlick’s Malted Milk Tablets, as suggested from the plentiful supply of wrappers he recycled. Photo used with permission.A glimpse of one of Maling’s other interests may be seen in one of the few known photographs of him. In the last photographs of James Murray, taken in July 1915 in the “Scriptorium” where most of the Dictionary had been compiled, Maling appears as one of his assistants—and he can be seen to be wearing a small star in his lapel. Taken in isolation, this doesn’t say much; but in fact we know that it must have been a green star—the symbol of Esperanto, which we know from other recycled slips to have been one of his particular enthusiasms. This enthusiasm extended to making translations of contemporary writers: his translation of five speeches by the Scottish evangelist Henry Drummond was published in 1935, and his Esperanto version of the hymn “God is my strong salvation” has appeared in several hymnals. He was also the recipient of other published translations, whose covers and dust jackets were added to his recycling pile and are preserved in the archives as the versos of slips.

We can also tell that Maling was probably a man of means. Many of the recycled slips are taken from correspondence with his stockbroker or with the companies whose shares he owned. One of his investments was in the company that became Welwyn Garden City Limited; he also had some interest in another early garden city, Letchworth, as we can see from a scrap of a leaflet advertising “Letchworth Civic Week” in May 1926.

There is some evidence among the slips—in the form of literature from charities—to suggest that Maling had a particular concern for the blind; perhaps he had a close relative who lost his or her sight. In any case, he was interested enough in the issue to acquire some kind of device for making Braille. Not content with writing regularly in Braille by this means, he was also quite happy to create pictures with his machine, which he captioned—in Esperanto. Some of these were recycled as slips, including a remarkable series of images of a biplane landing (or possibly taking off).

An unsung hero?

Maling continued working on the Dictionary to the very end of the first edition. In late 1927, he was assigned to some preliminary work on the Supplement to the Dictionary that would eventually be published in 1933, but in January 1928 his health finally gave way—he had long been troubled by rheumatism—and in June he was pensioned off, only just before the grand dinner held in Goldsmiths’ Hall to celebrate the completion of the first edition. Later in 1928 he was awarded an honorary MA by Oxford University, in recognition of his work on the OED. He died in 1939.

“The beauty of history”—as I heard the comedian and history enthusiast Paul Sinha say as I sat down to write this article—”is that it is packed with untold stories and unsung heroes.” For me, in a small way, Arthur Maling is a bit of a hero; and I’m pleased to have the chance to tell at least part of his story.

A version of this article originally appeared on the OxfordWords Blog.

Featured image credit: Used with permission.

The post Esperanto, chocolate, and biplanes in Braille: the interests of Arthur Maling appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers