Accessible and inaccessible disciplines: why philosophy and science are similar but are treated differently

Amongst my books is a late nineteenth century edition of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. Purchased from a used bookshop many years ago, it contains the previous owner’s signature on the flyleaf together with a commentary: “Started Boston 1883. Began again in Salt Lake City February 1891. Began again 698 East Capitol St. Oct. 1911. Finished Nov. 1911.” I feel a bond with that reader, almost certainly not a professional philosopher, who persevered with difficult material, convinced that what was within was worth understanding. The commentary illustrates a striking difference between types of academic discipline. In some, the material, at least superficially, is accessible. In others, the door is firmly closed. Many of the creative arts fall into the first kind. Allen Ginsburg’s Howl can be appreciated by a teenager for its dark dynamics, despite the multitude of scholarly texts that deepen our understanding of that poem. In many sciences, the primary sources–journal articles–are impenetrable to nonexperts.

What of my own field, philosophy? Historically, some important philosophers, David Hume and René Descartes amongst them, combined sophisticated ideas with an elegant and accessible style. Unassisted readers struggle with other historical figures, such as Leibniz. But philosophy of the last fifty years has faced a special dilemma. Many outsiders, while recognizing that philosophy is difficult, become hostile and resentful when reading contemporary authors. Those same readers have a different reaction when faced with a journal article or even a textbook in molecular biology, acknowledging that the subject matter does not easily yield to amateurs, and rightly so. The reasons for the difficulties in both cases are straightforward–technical vocabularies, the assumption of much previous knowledge, subject matter that is remote from ordinary experience. What is puzzling is the difference in attitude by nonexperts. My Boston reader of a century ago thought that Kant was worth twenty eight years of effort and stuck with it.

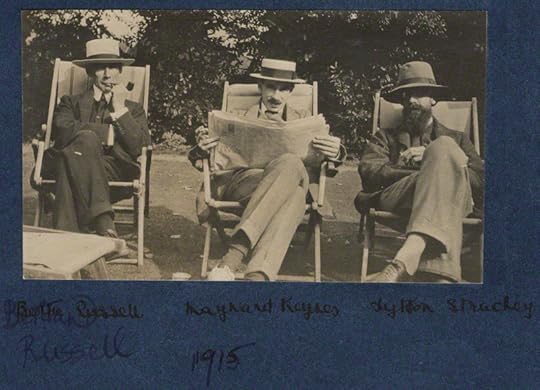

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell; John Maynard Keynes, Baron Keynes; Lytton Strachey, by Lady Ottoline Morrell, 1915 – NPG Ax140438. © National Portrait Gallery, London. Used with permission.

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell; John Maynard Keynes, Baron Keynes; Lytton Strachey, by Lady Ottoline Morrell, 1915 – NPG Ax140438. © National Portrait Gallery, London. Used with permission. [/pull]

Behind this antipathy to philosophy lies a peculiar psychological attitude, one that I have encountered many times. It is exhibited by a wide range of readers, from Nobel prize winners to Amazon reviewers. An individual, let’s call him Horace, has been successful in some area of intellectual activity such as physics, law, or engineering. Horace then infers from this success that he is equally adept in all other intellectual domains, including philosophy. Difficulties ensue, Horace does not understand why the author is arguing for X, or even what the argument for X is, but what Horace does know is that it’s the author’s fault or the fault of philosophy in general.

Not far from Kant on my bookshelves is Bertrand Russell’s The Problems of Philosophy. Originally published in 1912, it was part of the Home University Library series–later acquired by Oxford University Press–and its intended audience included working men and women with only a rudimentary formal education. Over a century later, Russell’s book remains a model of clarity and creativity. It was successful in part because thousands of readers who had never been to university, including miners, steelworkers, and other industrial laborers, were willing to come to grips with difficult ideas presented by a master of English style. They lacked hubris; they knew that this was going to be hard work and stuck with it. That attitude is rarer than it used to be, hence we now have a Sparknotes version of Russell’s book, complete with a “Plot Overview.” On our side, we philosophers should stop writing notes to one another. Some have done so; there are volumes in Oxford’s Very Short Introductions series that provide lucid, occasionally brilliant, expositions of contemporary philosophical ideas that challenge the reader.

What I fear is being lost, and it results from multiple influences, is the willingness to move from being a consumer of information to being an internal participant in philosophy. In mathematics, computer packages that solve differential equations are magnificently powerful but they can easily reduce you to a willing spectator. To understand mathematics, you have to work, really work, with the material. In many areas, Wikipedia is a wonderful source of information but it rarely jolts your mind. Contrariwise, information loss can force you to think, hence the old mathematical joke that to write an advanced textbook you just remove every other line from an intermediate textbook. To gain access to the realm of philosophy, you have to struggle with ideas, many of them weird and unappealing, few of them easy. That is what my Kantian book owner was willing to do. Those who are not willing will be left permanently on the outside, staring with puzzlement at their own reflections in the philosophical window.

Featured image: Scenography of the Copernican world system by Andreas Cellarius. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Accessible and inaccessible disciplines: why philosophy and science are similar but are treated differently appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers