Oxford University Press's Blog, page 449

October 26, 2016

Etymology gleanings for October 2016

Mr. Madhukar Gogate, a retired engineer from India, has written me several times, and I want to comment on some of his observations. He notes that there is no interest in the reform in Great Britain and the United States. I have to agree. Nothing we are doing in this area seems to be of much practical use. The horse is dead, and I am almost sorry for beating the carcass. I stick to my opinion that the only way to arouse the public would be to recruit a few people whose voice will be heard everywhere and at once. A letter signed by two Nobel Prize winners (let us say, Toni Morrison and Bob Dylan) or a song by Bob Dylan (rhymed, as in, for instance: “I keep yellin’! Something should be done about spellin’,” or unrhymed) would do more good than all our impotent meetings and blogs. Those few people who know something about the history of Spelling Reform remember only that G. B. Shaw was its avid advocate. And that’s how it should be: Shaw was world famous. Should I accost them? Will they respond? Can I break through the fence of their secretaries and agents?

This innocent child does not know what she is up to. Poor child! Spelling Reform has failed her.

This innocent child does not know what she is up to. Poor child! Spelling Reform has failed her.Mr. Gogate adds that now the time for the reform has passed: too many people in the world use English. I can add to it comments from some other of my correspondents to the effect that the spellchecker has made all attempts to reform English spelling redundant, among other reasons because changing the system would be too expensive. Perhaps so. But when I see how millions are wasted on something labeled “visions,” “initiatives,” “innovative methods,” and their likes (with no results except improved statistics, and even that is usually disproved some time later), I think that our society is ready to spend inordinate sums of money as long as it believes in “initiatives.” Spelling Reform may cost a lot, but it will save much, much more in teaching people (both natives and foreigners) to read and write English. It is silly to write committee, with almost every letter doubled, gnaw with initial g, whore with initial w (which has never designated any sound), build and bury instead of bild and bery, and choir for what everybody pronounces as kwire. Details are irrelevant. The main thing is to get things going. I don’t expect progress in my lifetime. Only ghouls will triumph.

Slang

This is the question I received: “How does slang vary across languages? Is there one culture or language that has more slang words?” I know too few languages to be able to answer such a question. My impression is that all the modern European languages employ slang very widely, though in this matter it is important to have a precise definition of slang and not to confuse slang (understood as an expressive, colorful language) with professional jargons, thieves’ cant, criminals’ lingo, and swear words. Informal language must have been a universal phenomenon at all times. For example, racy words for copulation seem to exist and to have existed everywhere. However, it appears that English has beaten all records in producing slang. British (American, Canadian, Australian, New Zealand) slang has become a competitor of the Standard. Thousands of words have acquired odd synonyms, very often known only to a relatively small group of people. Urban Dictionary gives numerous examples of such coinages. Outside the English- speaking world, so many people hardly feel like foreigners at home when it comes to language. The extreme volatility of English slang contributes to the same effect. Those who are now around fifty don’t understand the slang used in the movies released soon after the end of World War II, and their parents are sometimes lost while watching modern movies.

Blessing and cursing

It seems to be a widespread phenomenon that the same word means “bless” and “curse.” Possibly this phenomenon is due to the uneasiness produced by cursing. (Those interested in why curse has the synonym cuss may read my post of 5 September 2012 “Do you ‘cuss’ your stars when you go ‘bust’?”) A euphemism makes sense here: people would use a word of the opposite meaning and imply grim irony, as in blessed out, that is, cursed out. Old Icelandic blóta meant “to worship,” but the sense “to curse, swear” has also been attested. The same holds for the noun blót “worship.” Guðbrandur Vigfússon, the author of the great Icelandic dictionary of Old Icelandic (known as Cleasby-Vigfusson), wrote the following at blót: “Metaphorically in Christian times the name of the heathen worship became odious, and blót came to mean ‘swearing, cursing’.” It is doubtful whether this explanation is correct. One might suggest that, since Old Germanic blotan meant “to sacrifice,” people asked the deity either to send them what they were asking for (that is, a blessing) or to punish their enemies and thus curse them. If so, the ambiguity was inherent in the process. Incidentally, Guðbrandur was among those who thought that Engl. bless had been derived from blotan.

I see no problem with German würgen. It is true that its Old English cognate developed only figurative senses (“to condemn, proscribe, etc.”), but in German it has always referred to strangulation; hence Würgengel “the angel of death.” The non-Germanic congeners of würgen also refer to the rope, tangled bushes (hedges), and so forth. Apparently, the activities of this demon were not always associated with a kiss. The creatures known as incubus and succubus also strangle or choke their victims.

A most singular message

The language police are marching in serried ranks.

The language police are marching in serried ranks.I received a letter from a colleague who wondered at my daring. How could I risk raising my voice against the use of they for a singular object? In my previous “gleanings,” I mentioned the case of criminals, all of whom were males, but the policeman kept referring to each of them as they. At my colleague’s institution, a rule prohibited the use of he or she in such contexts. There are severe reprisals for transgressing the will of the superiors there. It seems that our language police feel as free to act as the criminals I mentioned. Long live democracy!

Like a thief in the night

An image of language change.

An image of language change.Language change is sometimes almost imperceptible. In the nineteenth century, everybody wrote: “I am of opinion that….” Then the article appeared before opinion, and now we say: “I am of the opinion that….” Dickens wrote: “Under cover of the darkness.” The articles still jump all over the place in this phrase. I remember people saying: “He is legend” (compare the name of the rock band bearing this name and the phrase according to legend). Now I hear only: “He is a legend,” which I don’t like (we need reference to legend, not a legend). At any given moment, people believe that only the version to which they are accustomed is correct, but this is an illusion. Every student of language history knows this.

Images: (1) To Write by Raphaël Jeanneret, Public Domain via Pixabay. (2) “Police Marching During Remembrance Day” by Richard Eriksson, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr. (3) Thief Cartoon by K Whiteford, Public Domain via Public Domain Pictures. Featured image: “Tamara and Demon. Ill to Lermontov’s poem” by Mikhail Vrubel, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Etymology gleanings for October 2016 appeared first on OUPblog.

Which Founding Father are you? [quiz]

The interests of the Founding Fathers heavily influenced the framing of the Constitution. Much like representatives today, each came to the convention prepared to defend their right to conflicting benefits.

Take this quiz to see which Founding Father you most align with. For more on the Founding Fathers and the history behind the Constitutional Convention, check out The Framers’ Coup: The Making of the United States Constitution by Michael J. Klarman.

Featured image credit: Washington at Constitutional Convention of 1787, signing of U.S. Constitution by Junius Brutus Stearns. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Which Founding Father are you? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

What exactly is ‘contract theory’?

At first glance, it may seem a dizzyingly impenetrable subject matter, but Oliver Hart and Bengt Holmström’s contributions to ‘contract theory’ have revolutionized the study of economics. They have recently been awarded the 2016 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences, with the presentation committee noting how their pioneering analysis laid the “intellectual foundation for designing policies and institutions in many areas, from bankruptcy legislation to political constitutions.” But what does this mean in practice? The Nobel committee went on to state that:

“Modern economies are held together by innumerable contracts. The new theoretical tools created by Hart and Holmström are valuable to the understanding of real-life contracts and institutions, as well as potential pitfalls in contract design…”

Essentially, Hart and Holmström have developed tools for critically thinking about some of the biggest political issues we face. For instance, Holmström has dealt with executive pay – and argued that when creating contracts there must be an adequate balance between risk and incentive. This is particularly pertinent to sectors such as banking, where companies would like to encourage innovation wherever possible, whilst avoiding any reckless behaviour. In a similar vein, Hart has focused on ‘incomplete contracts’, informing current debates concerning privatisation of state services. To give just one example, if there are no contract clauses dealing with ‘how’ services should be carried out (i.e. trains, prisons, postal services) then private companies may have too much of an incentive to cut costs, and thus lower quality to unacceptable levels.

Congratulations to both Hart and Holmström on their amazing achievement. To celebrate, we’ve compiled a collection of chapters and journal articles, either written by or about Hart and Holmström, to help you gain a better understanding of these two Nobel Laureates and their work.

‘Introduction’ in Firms, Contracts, and Financial Structure by Oliver Hart

The introduction to Oliver Hart’s classic 1995 text, in which he provides a framework for thinking about firms and other kinds of economic institutions. Hart discusses the problems creating contracts which satisfactorily deal with every single real-life eventuality, and argues that this concept, of ‘contractual incompleteness and power’ can be used to understand many economic institutions and arrangements.

‘Grossman-Hart (1986) as a Theory of Markets’ by Bengt Holmström in The Impact of Incomplete Contracts on Economics

Part of a book titled The Impact of Incomplete Contracts on Economics, Bengt Holmström argues that Hart’s theory (outlined above) could actually be construed as ‘a theory of markets rather than a theory of the firm.’ Holmström opens by asking what exactly is meant by a ‘firm’ – and opines that a firm should not be understood via transactions, but through its owner’s decision-making rights.

Agree English Consent by Catkin. Public Domain via Pixabay.

Agree English Consent by Catkin. Public Domain via Pixabay.‘Foundations of incomplete contracts’ by Oliver Hart and John Moore in Review of Economic Studies

In the last ten to fifteen years, a new area has emerged in economic theory, which goes under the heading of “incomplete contracting.” This approach has been useful for understanding topics such as the meaning of ownership and the nature and financial structure of the firm. Yet almost since its inception, the theory has been under attack for its lack of rigorous foundations. In this article, Hart and Moore evaluate some of the criticisms that have been made of incomplete contracting theory, and develop a model providing a rigorous foundation for the idea that contracts are incomplete.

‘Contracts as reference points’ by Oliver Hart and John Moore in the Quarterly Journal of Economics

Hart and Moore argue that a contract provides a reference point for trading parties’ feelings of entitlement. The authors present an alternative and complementary view by developing a model in which “a party’s ex post performance depends on whether the party gets what he is entitled to relative to the outcomes permitted by the contract.” Their analysis provides a basis for long-term contracts in the absence of noncontractible investments and elucidates why “employment” contracts, which fix wages in advance and allow the employer to choose the task, can be optimal.

‘The governance of exchanges: members’ cooperatives versus outside ownership’ by Oliver Hart and John Moore in the Oxford Review of Economic Policy

“Rapid and fundamental changes in the economics of exchanges suggest that it is important to consider whether the governance structures that have evolved in the past are likely to remain appropriate for the future.” Hart and Moore argue that the crucial distinction between a cooperative structure and outside ownership concerns who has residual rights or control over the non-human assets. They believe that both forms of governance are inefficient – but for different reasons, and in different ways.

‘Managerial incentive problems: a dynamic perspective’ by Bengt Holmström in Review of Economic Studies

Holmström’s paper investigates the idea that career concerns induce efficient managerial behaviour, and considers the implications of reputation on managerial risk-taking. “The fundamental incongruity in preferences is between the individual’s concern for human capital returns and the firm’s concern for financial returns. The two need be only weakly related. It is shown that career motives can be beneficial as well as detrimental, depending on how well the two kinds of capital returns are aligned.”

‘The internal economics of the firm – evidence from personnel data’ by George Baker, Michael Gibbs, and Bengt Holmström in the Quarterly Journal of Economics

Through analysing 20 years of personnel data from one firm, this study aims to reveal the nature of the internal labour market and the wage policy of the firm. In doing so, Baker, Gibbs, and Holmström provide organisation theorists with a descriptive paper on the internal economics of the firm.

‘The wage policy of a firm’ by George Baker, Michael Gibbs, and Bengt Holmström in the Quarterly Journal of Economics

Baker, Gibbs, and Holmström analyse salary data from a single firm in an effort to identify the firm’s wage policy. Among their findings is evidence that employees are partly shielded against changes in external market conditions, and that promotions and wage growth are strongly related, even though promotion premiums are small relative to the large wage differences between job levels.

‘Oliver Hart’s Contributions to the Understanding of Strategic Alliances and Technology Licensing’ by Josh Lerner in The Impact of Incomplete Contracts on Economics

Also appearing in The Impact of Incomplete Contracts on Economics, Josh Lerner highlights how Hart’s theory is especially relevant to analysing strategic alliances. In it, older case-studies are considered, but it is argued that Hart’s work brings forth new issues which are not yet fully understood. This is particularly the case when looking at terms of trade among partners, and the complex relationships between contracting and the market itself.

Featured image credit: Storage Papers Office by Unsplash. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post What exactly is ‘contract theory’? appeared first on OUPblog.

Why is the Bible so much like a horror movie?

What does the Hebrew Bible have in common with horror movies? This question is not as strange as it might seem. It only takes a few minutes with the biblical texts to begin to realize that the Bible is filled with all kinds of horror. There are strange figures dripping blood (Isa. 63) and mysterious objects that kill upon touch (2 Sam. 6:7). Women are threatened, pursued, and even dismembered (Judges 19). The “scream queens” of horror are well matched by the screaming women of the Bible, especially in the prophetic literature, where women weep, cry, and howl in pain. (Even when it is men who are crying, their sound is compared to the sound of screaming women, as in Isa. 26:17-18). Even the repetitions of horror—the endless sequels, the killers returned from the (near) grave to haunt another day, the perky college students who just can’t stop going into the basement to find out what’s making that noise—have their parallels in the repetitions of the Hebrew Bible—the people who can’t stop sinning, the God who can’t stop finding new and appalling ways to punish them (in the book of Numbers: miserable food, disease, poisonous snakes, and strange fire, to name but a few). A better question might be not ‘What does the Bible have in common with horror movies?’ but ‘Why is the Bible so much like a horror movie?’.

I first became interested in reading the Bible in dialogue with horror because I was frustrated with the ways biblical scholarship repeated the same explanations about the prophetic literature, often without exploring how else we might understand the texts in all their bloody intensity. Intentionally framing the Bible as a work of horror destabilizes our sense of the familiar, while also opening new possibilities for reading—many of them inspired by new readings of horror films by critics, feminist and otherwise.

Scary image by Simon Wijers. CC0 1.0 via Unsplash.

Scary image by Simon Wijers. CC0 1.0 via Unsplash.What does approaching the Bible like a horror film do for us as readers?

Classifying the Bible as horror lets us identify and address the parts of the text that are truly horrible, without trying to make excuses or sweep them under the interpretive rug. Instead, this approach shows that we might find continuity with other texts and scenes of horror. Isa. 63, the passage I have alluded to above, describes God’s appearance on the horizon, dripping with the blood of those he has trampled. This immediately brings to mind iconic scenes from The Shining and Carrie. In Hosea 2, God, terrorizing Israel (here represented as a woman), threatens to “hedge her up with thorns” and torture her, an image I have long associated with the barbed-wire death scene in Dario Argento’s Suspiria.

Horror also makes us think about gender, and what it means to have a female body. While both male and female bodies are subjected to outrageous violence and sadism, these bodies are not treated equally. In the Hebrew Bible, and in the prophets in particular, female bodies are disproportionately subjected to violence; rarely do they appear without being threatened. A common trope in horror films is that women who have sex are punished with violence, pain, or death; this is the case in Ezekiel 16 and 23 as well. On the other hand, death isn’t always a consequence of sex; God kills Ezekiel’s wife for no reason a few chapters later, in Ezek. 24:15-25. Lowbrow horror films, especially slasher films, are often criticized for their undermotivated violence; characters die “for no good reason.” The same is true, of course, of the Bible as well.

All this leads to another question, one often asked of horror films: What sort of person would want to watch that?—or, in the case of the Bible, What sort of person would read—or believe—that? If the Bible is truly as gruesome as a horror film, wouldn’t it be better simply to reject it? As a Bible scholar and (easily frightened) horror fan, I suggest the answer is no. The pleasure we take in watching Psycho or The Babadook—or I Know What You Did Last Summer or Child’s Play—is not simply sadism or misogyny. Instead, horror lets us complicate our experiences and play with categories. Ezekiel’s vision of the valley of the dry bones, in which the bones are brought back to life, takes on new (and more ominous) implications in light of zombie fictions as well as older films like Re-Animator. Horror also lets us play with gender. Here, one famous example in horror film is the “Final Girl,” the feisty, androgynous, female character who is the slasher film’s sole survivor (the term was coined by Carol Clover in Men, Women, and Chain Saws). The Final Girl helps us to understand a figure like Jael, the Kenite woman in Judges 4 and 5 who stabs the Canaanite general Sisera to death and lives to tell the tale. Like the Final Girls of horror films, Jael is self-directed, independent, vaguely masculinized – Sisera addresses her with a masculine grammatical form – and more than willing to stab a killer to death using a phallic weapon (in her case, a tent peg). Reading Judges 4 and 5 while watching Halloween or Scream draws out unexpected connections of all sorts.

As every horror fan knows, the call is coming from inside the house. So too: The call is coming from inside the Bible. The only question is whether to answer.

Headline image credit: Image by tertia van renseberg. CC0 1.0 via Unsplash.

The post Why is the Bible so much like a horror movie? appeared first on OUPblog.

October 25, 2016

A question of public influence: the case of Einstein

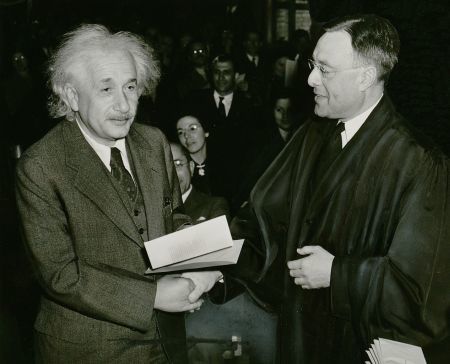

Einstein’s scientific achievements are well known even if not widely understood by non-scientists. He bestrode the twentieth century like a colossus and physicists are still working through his legacy. Besides, the theory of relativity penetrated far beyond science into many areas of literature and the arts. If hard to measure, evidence of his cultural influence is unmistakable. Even Mao Zedong described himself as an Einsteinian. It’s much more difficult to account for the influence of Einstein’s political opinions about which he was vocal from the moment he announced his opposition to the First World War, till his signature on the Russell-Einstein Manifesto in 1955, the year of his death.

There’s no question that Einstein’s political views — on war, peace, the bomb, Zionism, world government, socialism, freedom and human rights — were listened to because of his fame as a scientist. That much he conceded himself. His opinions were expressed in highly individual and arresting ways but they were not in themselves original. Beyond the status his scientific genius gave him, what are the sources of his influence on political debate? How can we assess the impact of his ideas on the public life of the twentieth century?

There is no doubt that Einstein’s visit to America in 1921 and his emigration there in 1933 had a massive impact on his visibility as a public figure. The great image factory and publicity machine which is America worked its magic on Einstein, pushing him on to the global stage. Intensely private an individual as he was, he also had an instinct for publicity and a desire to be heard on causes he favored. He was eminently quotable as well as photogenic.

Albert Einstein receives his certificate of American citizenship from Judge Phillip Forman, 1 October 1940. Photo by New York World-Telegram and the Sun staff photographer: Al Aumuller. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Albert Einstein receives his certificate of American citizenship from Judge Phillip Forman, 1 October 1940. Photo by New York World-Telegram and the Sun staff photographer: Al Aumuller. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.There is a danger, however, in pressing this line too far. It’s common to place Einstein on a pedestal and assess him in isolation from his contemporaries, and to be fair, his often pithy and profound utterances lend themselves to brief quotation. His writings are a gift to the sound-bite culture. But the truth is that Einstein was more often than not in company in his journey through the great crises of the twentieth century. He was in regular communication with an array of global intellectuals who can be broadly termed a ‘liberal international’ along the lines of the socialist internationals. They included Gandhi, Albert Schweitzer, Freud, Thomas Mann, Bertrand Russell, H.G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw, Romain, Rolland, and John Dewey.

They did not form a group and they did not always agree but they were often to be found signing manifestos, joint letters, attending conferences supporting campaigns on behalf of peace and comparable causes. Einstein knew or corresponded with all of them. In his more optimistic moments he believed intellectuals could and should institutionalize such activity through the establishment of some permanent organization to exert a ‘salutary moral influence’ on public affairs. It never happened but the aspiration was always there.

There is another equally important reason for the power and visibility of Einstein’s radical liberalism — and this was the essentially moral tenor of his message. His was a peculiarly non- or apolitical stance which stayed clear of party and generally remained above the day-to-day battle of politics. Einstein was often accused of idealism and impracticality, but it’s more accurate to say that his impact was to redirect attention to fundamentals and thereby present a challenge to current practice. We are inured now to a profound cynicism about the motives and actions of politicians which affects our views, not only of the politicians but of their critics too. We trust neither, especially open expressions of idealism. Everyone, we are sure, has their self-interested motives in the merciless free-for-all which is modern politics. The political culture in which Einstein operated was markedly more open to expression of moral values.

Another vital feature of Einstein’s message is his genuinely global vision. From an early age, Einstein rebelled against nations and nationalism. At 16, he left Germany for Switzerland and renounced German citizenship. He was required to take it up later when he worked there, only to lose it again when Hitler came to power. He became a US citizen in 1940 but always retained Swiss citizenship since he felt Switzerland was most free of the attitudes which led other nations into war. When Bertrand Russell listed the scientists who signed the Russell-Einstein Manifesto he did not place Einstein among the Americans, but described his citizenship as ‘somewhat universal.’ Einstein thus seemed free of narrow nationalistic motives which had helped to make the twentieth century the most destructive in history. In short, Einstein was a universal figure who stood for something larger than national life.

Einstein was a controversial figure in his time — hated as much as he was loved. The battlegrounds he chose are still current, not least in the tension between nationalism (or localism) and globalism, which ensures his continued relevance in our time.

Featured image credit: Albert Einstein in his office at the University of Berlin, c.1920. Unknown photographer. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A question of public influence: the case of Einstein appeared first on OUPblog.

Pinpointing the beginnings of audiology

There is little agreement on when the particular branch of science known as ‘audiology’ really begins. Much depends upon one’s view of what constitutes audiology. Definitions vary slightly but basically all agree that audiology is the science, study, measurement, or treatment of hearing, hearing loss, and associated disorders. Although the word ‘audiology’ itself seems not to have come into use until after World War II, the study of hearing and hearing defects began many centuries before.

The earliest written sources of information that we have, concerning diseases of the ear, come from ancient Egypt and they describe symptoms of deafness, ear discharge, tinnitus, and earache, i.e. the same problems as we have today. The Ebers papyrus (1550 BC) is the most interesting with regards to ear disorders and contains ‘cures’ for various symptoms. Some of the cures from this early papyrus seem rather odd to us, for example using head of shrewmouse, stomach of goat, and shell of tortoise (presumably ground) dusted into the ear canal. Others are easier to understand, such as the use of willow for pain (willow contains salicylic acid, still used as the basis for aspirin), and honey, which is antibacterial. Other ideas described in this papyrus also seem far-fetched, such as that the breath of life enters the right ear and the breath of death enters the left!

Greek medicine played a major part in the development of hearing science. Hippocrates (460–375 BC), the famous doctor and philosopher, attempted to account for the causes of disease and, although he believed deafness was mainly related to the prevailing winds and weather, he also reported deafness due to head trauma. Around 500 years later, Aulus Cornelius Celsus (25–50 AD) made use of a wide range of earlier Greek medical texts to write about various ear cures (amongst much wider writings). He tended to avoid the more outlandish folk remedies recommended by his contemporaries (for example veal suet with wild cumin to cure tinnitus, as suggested by Pliny the Elder) and some of Celsus’ ideas are not so far from our own, although not all of his cures would go down well today. His suggested cures for tinnitus, for example, included inserting castoreum mixed with iris oil or laurel oil into the ear. We might not wish to try this as it must have smelled terrible (castoreum is the strongly smelling oily yellow secretion that the beaver uses to mark its territory). Yet his suggestions are quite sensible as the contents of castoreum varies according to the animals’ diet but includes salicylic acid from eating willow twigs, and the oils he suggests for mixing with castoreum all have anti-microbial or anti-inflammatory properties.

‘Vintage Eckstein Bros., Inc. Screening Audiometer, Tetra-Tone Model EB-46, Circa 1975’ by Joe Haupt. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

‘Vintage Eckstein Bros., Inc. Screening Audiometer, Tetra-Tone Model EB-46, Circa 1975’ by Joe Haupt. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.However, let’s move on to more modern times where testing and measuring hearing started to develop. In 1834 Weber described a tuning fork test still used today, in conjunction with the Rinne test (1855), to differentiate conductive hearing loss from sensorineural loss. The first commercially available audiometer to measure hearing appeared in 1922 – the Fowler & Wegel Western Electric 1A – which measured across 20 octaves from 32Hz to 16384Hz. The next version, 2A, included bone conduction testing and was calibrated to the range 64 to 8192Hz, which is nearer to the range most commonly used today.

The original creator of the term ‘audiology’ is uncertain although it has been suggested (Newby, 1958) that it was first used as early as 1939. In any case the term was certainly not widely used before it was popularized by Raymond Carhart (1912–1975), an army speech pathologist, and Norton Canfield, an army otologist, when thousands of servicemen returned from WWII with noise-induced hearing loss due to the explosions and machinery of war. The earliest use of the term reported in the Oxford English Dictionary is 1946, when it was announced that a ‘specialist in the care of the deaf’ was ‘appointed senior consultant in audiology’ in the Ada (Oklahoma) Evening News. The profession continues to emerge and develop. Developments such as the immittance bridge by Otto Metz in 1946 (leading to the practice of tympanometry), and of masking to provide a recognized way of obtaining accurate audiometric results (Hood 1960), and discoveries such as otoacoustic emissions by David Kemp in 1977 (now used in universal neonatal screening) are some of the many great scientific and clinical advances that have led to changes in the discipline and a broadening of scope of practice.

Featured image credit: ‘Traditional hearing aids’ by Ike Valdez. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Pinpointing the beginnings of audiology appeared first on OUPblog.

“The Brazilian Cat” – an extract from Arthur Conan Doyle’s Gothic Tales

We’re eagerly preparing for Halloween this month by reading all of our creepy classics and spine-chilling tales. Below is an extract from “The Brazilian Cat”, one of many short stories from master of the Gothic from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Known primarily for his Sherlock Holmes character, Conan Doyle also drew on his own medical background, his travels, and his increasing interest in spiritualism and the occult for his Gothic Tales. Read on if you dare…

We passed quietly down the lamp-lit Persian-rugged hall, and through the door at the farther end. All was dark in the stone corridor, but a stable lantern hung on a hook, and my host took it down and lit it. There was no grating visible in the passage, so I knew that the beast was in its cage.

‘Come in!’ said my relative, and opened the door.

A deep growling as we entered showed that the storm had really excited the creature. In the flickering light of the lantern, we saw it, a huge black mass coiled in the corner of its den and throwing a squat, uncouth shadow upon the whitewashed wall. Its tail switched angrily among the straw.

‘Poor Tommy is not in the best of tempers,’ said Everard King, holding up the lantern and looking in at him. ‘What a black devil he looks, doesn’t he? I must give him a little supper to put him in a better humour. Would you mind holding the lantern for a moment?’

I took it from his hand and he stepped to the door.

‘His larder is just outside here,’ said he. ‘You will excuse me for an instant, won’t you?’ He passed out, and the door shut with a sharp metallic click behind him.

That hard crisp sound made my heart stand still. A sudden wave of terror passed over me. A vague perception of some monstrous treachery turned me cold. I sprang to the door, but there was no handle upon the inner side.

‘Here!’ I cried. ‘Let me out!’

‘All right! Don’t make a row!’ said my host from the passage. ‘You’ve got the light all right.’

‘Yes, but I don’t care about being locked in alone like this.’

‘Don’t you?’ I heard his hearty, chuckling laugh. ‘You won’t be alone long.’

‘Let me out, sir!’ I repeated angrily. ‘I tell you I don’t allow practical jokes of this sort.’

‘Practical is the word,’ said he, with another hateful chuckle. And then suddenly I heard, amidst the roar of the storm, the creak and whine of the winch-handle turning, and the rattle of the grating as it passed through the slot. Great God, he was letting loose the Brazilian cat! In the light of the lantern I saw the bars sliding slowly before me.

Already there was an opening a foot wide at the farther end. With a scream I seized the last bar with my hands and pulled with the strength of a madman. I was a madman with rage and horror. For a minute or more I held the thing motionless.

I knew that he was straining with all his force upon the handle, and that the leverage was sure to overcome me. I gave inch by inch, my feet sliding along the stones, and all the time I begged and prayed this inhuman monster to save me from this horrible death. I conjured him by his kinship. I reminded him that I was his guest; I begged to know what harm I had ever done him. His only answers were the tugs and jerks upon the handle, each of which, in spite of all my struggles, pulled another bar through the opening. Clinging and clutching, I was dragged across the whole front of the cage, until at last, with aching wrists and lacerated fingers, I gave up the hopeless struggle. The grating clanged back as I released it, and an instant later I heard the shuffle of the Turkish slippers in the passage, and the slam of the distant door. Then everything was silent.

The creature had never moved during this time. He lay still in the corner, and his tail had ceased switching. This apparition of a man adhering to his bars and dragged screaming across him had apparently filled him with amazement. I saw his great eyes staring steadily at me. I had dropped the lantern when I seized the bars, but it still burned upon the floor, and I made a movement to grasp it, with some idea that its light might protect me. But the instant I moved, the beast gave a deep and menacing growl. I stopped and stood still, quivering with fear in every limb. The cat (if one may call so fearful a creature by so homely a name) was not more than ten feet from me. The eyes glimmered like two disks of phosphorus in the darkness. They appalled and yet fascinated me. I could not take my own eyes from them. Nature plays strange tricks with us at such moments of intensity, and those glimmering lights waxed and waned with a steady rise and fall. Sometimes they seemed to be tiny points of extreme brilliancy — little electric sparks in the black obscurity — then they would widen and widen until all that corner of the room was filled with their shifting and sinister light. And then suddenly they went out altogether.

Featured image credit: Dungeon by Tine Steiss. CC-BY SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post “The Brazilian Cat” – an extract from Arthur Conan Doyle’s Gothic Tales appeared first on OUPblog.

Nine most thought-provoking moments in Radiohead

Radiohead is clearly a thinking-person’s music, but which of their songs are the most thought-provoking, and why? How do we make sense of their often surprising, even shocking music? If you’ve ever found yourself pondering Radiohead way too much, here are some clues, a few answers, and even more questions.

9. Chord substitution in “Motion Picture Soundtrack” (2000-10, 2:44)

This Kid A finale couldn’t be any more in G major. Why then, when Yorke sings his final high G (“I will see you in the next LIFE”), is the G chord we expect replaced by a crunchy C-sharp half-diminished seventh? This dissonant uncertainty regarding our “next life” (C# half diminished) creates tension until the “Amen” cadence (C major–G major) alleviates our anxieties about the afterlife.

8. Displaced Guitar Rhythm in “Let Down” (1997-5, 2:11)

In the first chorus the lead guitar plays a three-note melody starting on a high A (A–G#–E). It happens right on beat 1, but in the second chorus, it gets moved back a beat early, beginning on beat 4 of the previous bar. Why? To my ears, the misplaced high A actually foreshadows the song’s climax: Yorke’s heroic ascent to that same high A in the third verse (“one DAY”).

7. Deformed Timbre(s) in “Daydreaming” (2016-2, 5:51)

Jonny and Nigel are both geniuses at taking normal sounds and deforming them into something spooky. After hearing both cello and Thom’s voice throughout this track, which is making that spooky sound at the very end? Voice, cello, or some sort of voice-cello Chimera? What’s being spoken is one thing, but how they slowed, reversed, and processed Yorke’s voice to sound like an aggressively bowed cello is even more fascinating.

6. 5-against-4 handclaps in “Lotus Flower” (2011-5, 0:01–0:14)

The drum and bass groove of this song is clearly in 4/4, but what’s up with that repeating 5-note handclap pattern? [clap-clap-rest-rest-rest]. Like so many anomalies in Radiohead’s music, this one has a clear mathematical explanation. Because 5 and 8 are co-prime—no smaller number other than 1 divides both evenly—those 5-count hand claps will actually complete the cycle of all possible eighth notes in 4/4 [34…12…78…56…] before starting over again.

5. Minor-major 7th chord, “Life as a Glass House” (2001-11, throughout)

According to classical music theory, seventh chords come in 5 flavors. This isn’t one of them. It’s a minor triad (A-C-E) with a MAJOR seventh (G#). Still, it’s oddly familiar. Where have we heard that chord before? Really just one place: Bond films. After we hear this association with spy/espionage, Yorke’s lyrics “but someone’s listening in” at the end of the first chorus make a lot more sense.

4. Runaway drum machine, “Idioteque” (2000-8, 1:52–2:34)

This song begins with a 6-count drum machine. But how is that 6-count drum part supposed to work in a song with a 20-count chord progression? Verse 1 is easy: the drums just fill in the remaining 14 beats with hi-hat and snare. But in verse 2, which has 100 total beats, the drums run out of control, playing the 6-count beat over and over. What’s weirder? There are a few 4s and 2s thrown in just to mess with you. See if you can count all the 6s, 4s, and 2s to make 100 beats (hint: the answer is at the end of Chapter Three!)

3. Quarter-step detuning, “No Surprises” (1997-10, throughout)

As if they knew that every sappy singer-songwriter would be trying to learn this for their next coffee shop gig, Radiohead basically made it impossible to play along to. It’s not in F, it’s not in E, it’s actually halfway between the two. Whether you call it “E quarter-sharp” or “F quarter-flat”, your tuner doesn’t have that note. So, should you just start on 4th fret and bend everything up? (please don’t). Want a hack? Offset your tuner’s calibration down 50 cents and tune to F.

2. Creepy backwards singing, “Like Spinning Plates” (2001-10, throughout)

What’s Yorke saying, and why does it sound so weird? Believe it or not, this trick was taken from an early Twin Peaks episode. Agent Cooper meets a dwarf voiced by an actor who recorded his speech, played it backwards, learned his backwards-speech phonetically, recorded that, and then the sound engineers reversed the reverse, creating a simulacrum of regular speech. Because the backing track for “Like Spinning Plates” is an ill-fated circa-1997 “I Will” demo reversed (!), Yorke’s strategy actually makes perfect sense.

1. Euclidean rhythms in “Pyramid Song” (2001-2, throughout)

Why has more ink been spilled on this rhythm than any other moment in Radiohead’s catalog? Like the Golden Ratio in music, it’s because of a special geometry. The five chords are arranged unevenly over 16 beats as 3+3+4+3+3. It’s longer in the middle than the ends, just like a pyramid, and, just like a pyramid has four sides of 3 angles and one side with 4 angles, this rhythm has four chords lasting 3 beats and one lasting 4 beats. Coincidence? Maybe not: both of these pyramid shapes can be explained through the Euclidean algorithm—a mathematical formulation nearly as ancient as the pyramids themselves.

Listen to the full playlist below.

Featured image: “Radiohead” by swimfinfan. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Nine most thought-provoking moments in Radiohead appeared first on OUPblog.

October 24, 2016

Lovecraft resurgent

In the summer of 2016, there was lots of buzz around the TV series Stranger Things. Newspapers and websites rushed to provide cheat sheets for millennials on all the echoes and references to the 1980s embedded in the show, from Steven Spielberg and John Hughes movies, to Nightmare on Elm Street or Stand By Me, or the way the whole plot hinged on Stephen King’s key theme of kids navigating the fallout from flawed fathers, figured in supernatural terms.

Not many, however, noted that Stranger Things, with its murderous, tentacled creature unleashed through a trans-dimensional portal into a small town by the experiments of a mad professor, owed virtually everything to the imagination of H. P. Lovecraft. He composed these scenarios over eighty years ago in classic stories like ‘The Dunwich Horror’ and ‘The Shadow over Innsmouth’.

Lovecraft’s influence stands behind many of the key cultural icons of modern Gothic and horror. There would be no Alien series without him, no Species, none of those David Cronenberg body horrors, no Clive Barker, and no Pan’s Labyrinth. (Director Guillermo del Toro has long harboured ambitions to make a block-buster film of At the Mountains of Madness, the last attempt pipped at the post by Ridley Scott’s awful Prometheus.) There is also a whole post-millennial style of fiction, called ‘The New Weird’, which would be impossible without Lovecraft, although major contemporary writers in the mode, like China Miéville and Jeff VanderMeer, have an ambiguous and vexed relationship to the Old Weird.

It’s now pretty hard to imagine our monsters outside the squishy, tentacular paradigm conjured by Lovecraft. Amazingly, Lovecraft’s horrors have burst out of the chest of a small subculture and rapidly evolved into a creature that has transformed the very shape of our nightmares.

Lovecraft’s ancient god, Cthulhu, has risen from the South Seas as an awful menace that threatens humanity’s existence – but he is also a cuddly toy you can buy on the internet. In the 2016 American presidential race, you could even get a ‘CTHULHU FOR PRESIDENT’ T-shirt, which seemed entirely appropriate.

Lovecraft lost … and found

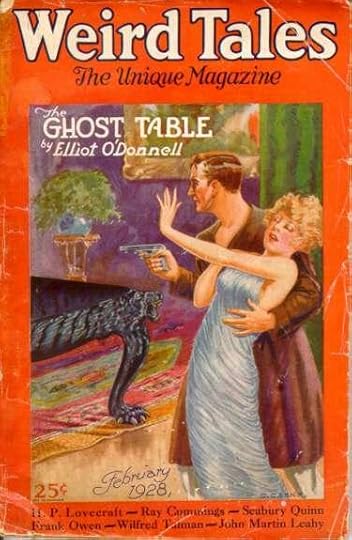

Cover of the pulp magazine Weird Tales (Feb 1928, vol. 11, no. 2) featuring The Ghost-Table by Elliot O’Donnell. Cover Art by C. C. Senf. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Cover of the pulp magazine Weird Tales (Feb 1928, vol. 11, no. 2) featuring The Ghost-Table by Elliot O’Donnell. Cover Art by C. C. Senf. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.When Lovecraft died in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1937, he was destined for literary oblivion. He had published only in small-circulation amateur journals and struggled to get his stories into the pulp magazines, cheap literature for a mass readership of millions but that paid very poorly. He ought to have found a home in Weird Tales, established in 1923, but his stories were often turned down there. He also wrote in pulps that were just beginning to stabilize around a newly coined term, ‘science fiction’. Lovecraft’s cosmic perspective, placing a fragile human race in the merciless context of astronomical space and time and the murderous competition for survival between biological species, sometimes chimed with editors in new journals like Astounding Science Fiction.

Yet Lovecraft made only a few hundred dollars here and there, his magazine work crumbling into dust, and he only ever published one limited edition book during his lifetime. He was considered a master of horror only amongst a small group of friends and fans, to whom he wrote voluminously throughout his life.

After his death, a number of these dedicated friends tried to interest New York publishing houses in collections of stories, but none were prepared to publish. This rejection prompted the establishment of the Arkham House press, which from 1939 published three volumes of his stories (hang on to those first editions if you happen to have one: they are now worth thousands). Yet when the esteemed American literary critic Edmund Wilson deigned to notice these volumes, he acidly declared that ‘the only real horror of most of these fictions is the horror of bad taste and bad art.’ This effectively condemned Lovecraft to a place entirely outside the literary sphere.

That outer darkness was where he stayed even when a mass paperback edition in the 1960s began to sell in the thousands, and then the hundreds of thousands, and even after horror hit the mainstream after the breakthrough of Rosemary’s Baby in 1968 and Stephen King began to publish in the early 1970s. Just as Gothic fictions were condemned as ‘terror novels’ that endangered public virtue in the eighteenth century, so horror fiction into the 1970s and 1980s was considered the outré, adolescent preserve of moody teens, a disordered sensation fiction that was certainly not literature. Even now, some might question Lovecraft’s appearance in a ‘Classics’ list.

A style for the times

As a writer of the 1920s and 30s, Lovecraft was decidedly not in the Modernist mode that dominates the literary history of that era. He fulminated against Futurism and particularly vented his scorn on T. S. Eliot’s poetry (although he shared his very conservative politics). Lovecraft’s tortured style, with sentences that pile up adjectives in tottering heaps in hilarious violation of every creative writing tutorial ever conducted, is about as far from Hemingway, or Raymond Carver’s minimalism, as you could imagine. It is not tasteful.

And yet there is something extremely powerful and evocative that crawls out of Lovecraft’s sentences, which often evoke horrors so effectively precisely because they are so broken and strange. He is pushing to imagine forces that exist beyond human capacities, embodied in the pressure he exerts on the order of literary prose. At his best, Lovecraft’s dime-store pulp sublime really can shatter the niceties of beautiful literary prose in extraordinary ways.

My sense is that in conceiving malignant ancient creatures that stir underground or that arrive from the cold dark of interstellar space, Lovecraft is also speaking anew to a world that feels on the brink of catastrophic change. The sense that humans have irreversibly broken the planet, and that Nature is coming back to exact a terrible revenge, is at the heart of many recent ‘weird’ fictions. Perhaps by now we should have elected H. P. Lovecraft as the Poet Laureate of the Anthropocene. He would get my vote, assuming I hadn’t had my head pulled off by Cthulhu already.

Featured image credit: “Dirt Road” by shrutikhanna. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Lovecraft resurgent appeared first on OUPblog.

Treatment of depression in autism spectrum disorder

Mood disorders, including major depressive disorder, appear to be more common in those with developmental disorders, including autism spectrum disorder (ASD) than in the general population. However, diagnosing depression in ASD represents a challenge that dates back to Leo Kanner’s original description of “infantile autism” in 1943. Kanner described a disturbance of “affective contact” in those with autism. Clinicians use the term “affect” to describe how someone’s emotional state appears to others. In other words, does the person look depressed or anxious? This is different from “mood.” Mood refers to how someone actually feels inside. Affect and mood are not always aligned. For example, someone’s expression may appear flat and they may show little emotional reactivity. However, that person may say that he or she feels fine. Alternatively, someone may present with laughter and giddiness and say they feel anxious or upset. Clinicians refer to this as an “incongruence of affect and mood.”

Many individuals with ASD show little facial emotion or reactivity. This does not necessarily mean they’re depressed. In other words, their affect doesn’t necessarily match how they feel. This mismatch between affect and mood, however, does make it more difficult to recognize and diagnose depression in someone with ASD. Limited verbal output or lack of speech can be an issue for up to 25% of person with ASD making it challenging for the clinician to assess the individual’s mood state. When clinicians are conducting a diagnostic evaluation on a neurotypical patient, especially an adult, they place a great deal of significance on the words the patient uses to describe their mood or how they feel. Not having access to this information can make it more difficult for the clinician to make an accurate diagnosis of a mood or anxiety disorder. It is important that clinicians not make assumptions about how a person with ASD with minimal to no speech feels. As discussed above, this can lead to an inaccurate interpretation because the person’s mood and affect my not be congruent. Even those individuals with ASD that have communicative language may not be able to identify or label their feelings accurately. They may not fully comprehend what the term “mood” means when we ask them; they may truly not know how they feel.

These factors can make it challenging to accurately diagnose depression in those with ASD. There are other strategies a clinician can use, however, to gather the information necessary to make a diagnosis of depression in these patients. We can ask about other symptoms that commonly occur in depression. These include changes in appetite or sleep, which can be either increased or decreased. There may be a significant drop in energy or lost ability to experience pleasure in activities that had been enjoyable. This may come with an overall decrease in interests and motivation. We can measure changes in weight and ask caregivers to monitor the hours of sleep and type of sleep the individual is getting. Still, it’s difficult to confidently diagnose depression in those who may not be able to convey how they feel verbally or non-verbally. A very important question to ask the patient, caregivers, and treatment team is “Has there been a significant change in the individual’s overall daily function compared to the recent past, that has persisted in a consistent pattern over the past few weeks or longer?” If the answer to this question is “Yes,” then the onset of a major psychiatric event or episode or an underlying medical problem “presenting” like depression should be strongly considered and investigated.

Another challenge in diagnosing depression in someone with ASD is the overlap in symptoms between the two conditions. The symptoms of depression include a flat or depressed affect (facial expression), reduced or increased appetite, sleep disturbance, low energy, reduced motivation, social withdrawal, and reduced desire to communicate with others. Many of these same symptoms can be present in ASD rather than depression.

Happy kids by White77. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

Happy kids by White77. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.When discussing the diagnosis and treatment of depression, it is always important to address the possibility of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. In medical training, psychiatrists learn to assess every patient for the risk of suicide, especially those with depression. We should not make assumptions about the thoughts or feelings of another individual. We can’t know if a person is having thoughts about suicide unless we ask them and they tell us. This includes those with developmental disorders like ASD, including individuals with minimal to no speech. In a recent study published in the journal Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, Angela Gorman et al. identified a number of risk factors associated with thinking about suicide and suicide attempts in children with ASD. Through parent interviews, the researchers inquired about 791 children with ASD, 186 typically developing children and 35 non-autistic children with diagnosed depression. The percentage of children rated by their parents as “sometimes” to “very often” contemplating or attempting suicide was 28 times greater for those with ASD than those with typical development. It was three times less among those with ASD than among the non-autistic children who had depression. Depression was also the strongest single predictor of suicidal thoughts or attempts among the children with ASD. Fortunately, suicidal tendencies were uncommon among children under age 10 years.

These findings underscore how important it is for clinicians to assess the potential for suicide whenever evaluating children, adolescents or adults with ASD. Yes, we are challenged in making an accurate diagnosis of depression and assessing suicide risks in individuals with ASD, but it is imperative that we use all the information available to us for this purpose. This should include direct interaction with and observation of our patients, as well as gathering collateral information from family members, teachers, job coaches, group home staff, and so on.

Despite the fact that depression is more common in individuals with ASD and other developmental disorders, very little research has been conducted to investigate the causes and precipitants of depression in this population or to identify effective treatments. In fact, to date, there has not been even one systematic clinical trial of an antidepressant medication for treating depression in individuals with ASD of any age, cognitive level of functioning, or diagnostic subtype published in the worldwide medical literature! We urgently need more research to develop better tools and techniques for diagnosing mood disorders, like major depressive disorder, in individuals in ASD. This is particularly important for those who have significant communication difficulties. It is possible that the use of augmentative and alternative communication devices may help in this regard. Moreover, we critically need research that advances the development of effective medications and behavioral treatments for depression in ASD. It may be that the challenges of accurately diagnosing depression in persons with ASD have contributed, in part, to this lack of progress. However, this is not a valid or acceptable reason for the lack of pursuing the development of effective treatment interventions for our patients. We must address the challenges of diagnosing depression in persons with ASD and redouble our efforts to identify effective treatment interventions and preventative strategies.

Featured image credit: Woman and Child by George Hodan. Public Domain Via publicdomainpictures.

The post Treatment of depression in autism spectrum disorder appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers