A new philosophy of science? Surely that’s been outlawed

The main thing that drew me to the history and philosophy of science was the simple desire to understand the nature of science. I was introduced to the exciting ideas of Popper, Kuhn, Lakatos, and Feyerabend, but it soon became clear that there were serious problems with each of these views and that those heydays were long gone.

Professionals in the field would no longer presume to generalize as boldly as the famous quartet had done. For the past 40 years or so the field has seen increasing levels of specialization. These days, philosophers of science tend to work on specific topics such as reduction, emergence, causation, the realism-anti-realism debate, or the latest band-wagon—mechanism. Meanwhile many other historians and philosophers have gone off at the deep end by concentrating almost exclusively on the context of discovery rather than on the actual science at stake. As we all know this development led to the nefarious Science Wars, which are only now finally starting to recede into the background.

As for my own work I have specialized in the history and philosophy of chemistry and in particular on the periodic table, including the question of the extent to which this system of classification reduces to quantum mechanics. More recently I have worked on the discovery of the elements and on scientific discovery in general. I have pondered over the question of scientific priority and multiple discovery. I seem to have now arrived, or maybe have stumbled into, a general approach to the philosophy of science of the form that one is no longer supposed to indulge in. Let me share a little of this view with you in case you have not now decided to switch off.

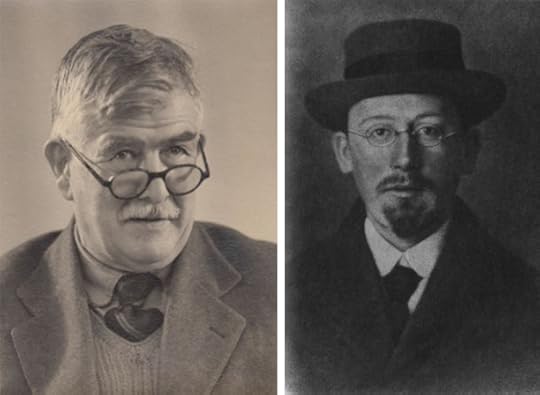

From left to right: 1) Charles Bury, chemist. Used with permission. 2) Dutch amateur scientist Antonius van den Broek (1870-1926). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

From left to right: 1) Charles Bury, chemist. Used with permission. 2) Dutch amateur scientist Antonius van den Broek (1870-1926). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.My work has focused on several minor figures in the history of modern chemistry and physics. They include such virtually unknown scientists as John Nicholson, Anton van den Broek, Edmund Stoner, Charles Bury, John Main Smith, Richard Abegg, and Charles Janet, none of whom are exactly household scientific names. What I see convinces me that these ‘little people’ represent the missing links in the evolution of scientific knowledge. I take the evolutionary approach quite literally as I will try to explain. Rather than concentrating on the heroic figures like Bohr, Pauli, and G.N. Lewis, in the period that interests me, I see an organic whole, the body scientific that is continually putting out random mutations in the form of hunches, guesses, speculations. No doubt the recognized giants of the field are those that seize upon these half-baked ideas most effectively. But in trying to understand the nature of science, we need to stand back and view the whole process from a distance.

What I see when I do that is something like a living, fully unified, and evolving organism that I have called SciGaia by analogy to James Lovelock’s Gaia theory, whereby the earth is one big living organism. But I reject any notion of teleology in my version. Science is not heading towards some objective “Truth” and here I agree with Thomas Kuhn who always insisted on this point.

But I disagree with the venerable Kuhn over the question of scientific revolutions. To focus on revolutions is to miss the essential inter-relationship and underlying unity between the work of all scientists whether it be the little or the big people. Talk of revolutions unwittingly perpetuates the notion that science advances through a series of leaps conducted by the heroes of science.

I also part company with most analytical philosophers of science by not placing any special premium on the analysis of the logical and linguistic aspects of science. I regard logic and language as being literally “superficial,” by which I mean that they enter into the picture after discoveries are made, for the purposes of communication and presentation. Discovery itself lies deeper than logic and language and has more to do with human urges and instincts, or so I believe.

Of course I do not claim to have invented the notion of evolutionary epistemology. I just seem to have arrived in somewhere in that camp by examining the grubby details in the development of early twentieth century atomic chemistry and physics such as the introduction of the quantization of angular momentum, the discovery of atomic number, the emergence of the octet rule, the use of a third quantum number to specify the electronic configurations of atoms, and so on.

What I find rather curious is that Kuhn more or less disavowed his early insistence on scientific revolutions in later life and turned to talk of changing lexicons. Indeed, in his final interview, he went as far as to say that the Darwinian analogy, that he had briefly mentioned in his famous book, had been his most important contribution and that he wished it had been taken more seriously.

Featured image by vladimir salman via Shutterstock. Used with permission.

The post A new philosophy of science? Surely that’s been outlawed appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers