Oxford University Press's Blog, page 386

March 29, 2017

Etymology gleanings for March 2017

Many thanks for the comments. One of the questions was about the dialect that could be used for the foundation of a new norm. No spelling can reflect the pronunciation of all English speakers. An ideal system, that is, phonetic transcription ([nou] or [neu], or [nöu] for no; [faiv], [foiv], or [fahv/ fa:v] for five) is out of the question. The hope is to retain what we have but rid it of the most obvious silliness and redundancies (mute and double letters, among others). There is no consensus about how far the reform should go, but all English speakers pronounce give, you, and done in approximately the same way, so that, if we respell such words as giv, u, and dun, no one will be “marginalized.” At this stage, reformers should only try to persuade the public that they are doing something beneficial to the world. Judging by the experience of other countries, I, for one, see no harm in abolishing the letters q and x (siks, kwite), leaving them, if necessary, in Quentin and Xerxes; replacing sc with sk, and so forth.

Truly instructive is Mr. Jevgēnij Kuktiņš’s story of the Latvian spelling reform. As an outsider, I am not a fan of the Latvian alphabet, because all diacritics are a nuisance. French children have a hard time even learning their é’s and è’s, while Latvian offers a veritable feast of special signs. This, however, is not my point. It appears that in recent history, Latvians agreed to introduce radical changes and are now “kwite” happy with what they have. To be sure, there is a difference: English is spoken by many million people all over the world, so that the odds are long, but Webster had his way with the changes of –ise to –ize, mould to mold, and colour to color. Perhaps the battle is not yet lost. The main thing is to begin it.

(By the way, Ouida’s name is pronounced wee-dah!)

Two ways of shutting up

I do know the history of u in words like but and put. When the Great Vowel Shift turned long u (that is, ū or [u:]) into the diphthong most modern speakers have in how, now, vow, short u followed suit and changed to an a-like vowel (a, as in Italian or German), because in the history of the Germanic languages, short vowels usually take their cue from their long partners. The change was not consistent, especially after the labial consonants b, p, f; hence bulb versus bull and fun versus full. The north of England did not participate in the change of short u. When our family lived in Cambridge (England), the science teacher in our son’s school began every lesson with the words SHOOT OOP. He was obviously a northerner. The famous philologist Joseph Wright grew up in Yorkshire, and his son used to mock him gently for his accent. There is a two-volume biography of Wright, written by his wife. Personal touches are few in it, but it is still a good book to read. And, yes, I also know about the present-day administrative division of Yorkshire, but thank you for the remarks: all comments are appreciated.

Cheshire cat and chessie/chessy

I was happy to read the comments on the impenetrable grin. After years of working with the origin of idioms, I have come to the conclusion that the beginning of our proverbial sayings, unless they go back to so-called familiar quotations, is beyond recovery. This may surprise even historical linguists: no phonetic laws or grammatical classes, no shaky semantic bridges, no protolanguage, and yet complete obscurity. Just try to explain why we should mind our p’s and q’s! Even more surprising is the circumstance that words are often extremely old, while idioms are usually not, and still their etymology is unknown.

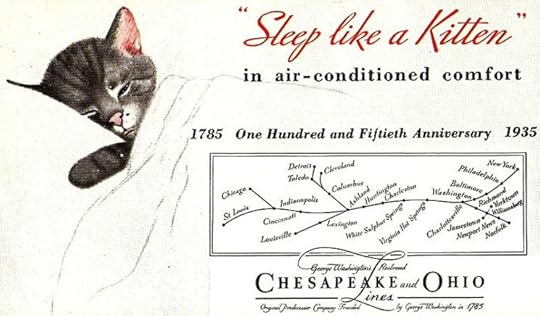

This is the famous Chessie kitten, unsmiling but cute.

This is the famous Chessie kitten, unsmiling but cute.Peter Maher reminded me of Chesapeake & Ohio Railway and of Chessie Systems in connection with the chessy cat, mentioned in my post. My search for the chessy cat immediately yielded C&O Railway, but the famous label (a cute kitten) is too late for explaining the origin of chessy. However, it does prove that the word chessy was known far away from Philadelphia, where it may have originated. Other than that, cat folklore is rich, and the grin of the Cheshire cat surely reminds one of a chain. But where do we go from this indubitable fact? To smile like a basket of chips, mentioned in the comment by Stephen Goranson, is a well-known idiom. I once heard it from an American speaker, and, if I remember correctly, he used it without reference to smiling (the meaning was “on a grand scale”), more or less synonymous with like a house on fire. I can imagine chips lying in two rows and resembling a mouth full of teeth—a captivating smile. But a grinning cat from Cheshire? Perhaps one of the explanations I quoted is correct after all. By the way, one can also smile like a brewer’s horse. Is the brewer’s horse always drunk?

A basket of chips: it will make you and your dentist smile.

A basket of chips: it will make you and your dentist smile.Odds and ends

To dine with Duke Humphrey “to stay without dinner.” Yes, indeed, the usual form of the idiom is to dine with Duke (not Earl) Humphrey, but in my database, the phrase turned up in its rare form, and I decided to quote it. I am sure many people share my experience and remember where they first encountered a rare word or an exotic idiom. In the introductory chapter to Martin Chuzzlewit, Dickens relates the glorious history of Martin’s ancestors. According to the extant records, one of them was especially distinguished, for he often dined with Duke Humphrey. But for a footnote, I, at that time a student, would not have understood the joke, which goes a long way toward repeating the truth, worn-out almost threadbare: “Don’t reprint classics without comments!”

Gerhard, the Devil’s name. Thank you for the reference to Geeraard de Duivelsteen, a 13th-century castle. Nothing is said about Geeraard’s reputation: he was swarthy, rather than evil. If Gerhard had already been known as one of the Devil’s many names, the dark-complexioned knight sheds no light on the idiom, and, if the name is more recent, it hardly refers to the castle’s owner.

Geerard de Duivelsteen, a 13th-century building, named after the knight Geerard Vilain. The owner was neither a devil nor a villain.

Geerard de Duivelsteen, a 13th-century building, named after the knight Geerard Vilain. The owner was neither a devil nor a villain.Bother and copacetic. I did try to find a Dutch etymon for bother! Nothing turned up. And the information on copacetic warms the cockles of my heart, for I am busy working on the letter C of my etymological dictionary, which shows what remarkable progress I am making toward the end of the alphabet.

Apostrophizing the overkill. One of the things Spelling Reform should fix is the use of the apostrophe. It is almost impossible to teach undergraduates the use of this nefarious sign. In my course “German Folklore,” I spend a whole semester imploring the students to write the Grimms’ Tales rather than the Grimm’s Tales (though they know that there were two brothers and agree that the Grimm is nonsense, they keep writing the phrase their way). But lo and behold! A correspondent sent me a text with the words y’all’re. He wonders whether there is not too much of muchness in it. I am afraid there is.

More answers in April, after its sweet showers have pierced March.

Image credits: (1) “Chesapeake and Ohio 150th anniversary 1935” by Chesapeake and Ohio Railway, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) “handful of biomass” by Oregon Department of Forestry, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr. (3)”Geeraard de Duivelsteen” by Paul Hermans, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Featured image credit: “Latvia 1998 CIA map” Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Etymology gleanings for March 2017 appeared first on OUPblog.

State of the union for Social Work Month 2017

We face a host of intertwined issues of social justice today, most of which are not new but deeply embedded historically. Poverty is ubiquitous, and economic inequality has increased both nationally and globally. Children continue to bear the brunt of poverty, especially children of color. Struggles for women’s rights continue around the world in the face of persistent gender inequality, oppression, and violence. The reality of racism in the US context is revealed in what Ta-Nehisi Coates refers to as the “carceral” state, in which prison and jail populations have increased exponentially over the past forty years, and in which one in four black men born since the 1970s has spent time in prison. It is revealed in increasingly hostile anti-immigration policies, practices, and rhetoric. It is revealed in the continued disregard for the sovereignty, histories, lands, and rights of American Indian and First Nation peoples, as evidenced most recently in the approval process for the Dakota Access Pipeline. Discrimination against sexual and gender minorities, and the oppression of individuals and groups marked as “other” by virtue of ability, age, or citizenship status, persist in our societal structures, institutional policies and practices, and everyday social relations.

These issues of social justice are fundamentally linked to basic human rights. Even though the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is nearly sixty-nine years old, violations of human rights and struggles to recognize and realize basic human rights continue on many fronts. One of the pressing social justice issues within contemporary social work in the US is our profession’s overall lack of human rights literacy, or a critical understanding of rights, to inform both direct practice and advocacy with individuals, families, and communities. A directly related issue is the limited attention to critical historical consciousness within social work. Michael Reisch in 1988 warned that social work is becoming an ahistorical profession, disconnected from its roots. We lose our sense of historical consciousness at our own peril.

A critical grasp of history in and of the profession is imperative for effective social justice work. As we engage with histories of policies and practices that have denied basic human dignity and with the myriad struggles through which individuals and groups have made claims for voice, rights, and survival, we find insight and inspiration to transform our practice in the present. Through sustained critical engagement with the history of social work we come to appreciate the possibilities of social movements, collective resistance and action, and the human potential for healing, growth, and transformation. We also bear witness to the consequences of blinkered views of what is “good” and “true,” and wherein one group’s certainties about what is “best” for those less powerful have produced damaging and denigrating effects.

History reminds us that change is possible and that “ordinary” people, often in the face of tremendous adversity, can be powerful agents of change.

Eduardo Galeano writes, “History never really says goodbye. History says see you later.” Galeano reminds us of the many ways in which history continues to reverberate in the present. A critical understanding of history can also help us see where flawed assumptions about the nature of personal or social struggles and about human difference have led to ineffective and often harmful practices in the name of “helping.” A historical perspective helps us see patterns and threads of connection across time. History permeates the present. As we begin to trace the lineages of thought and practice we find history everywhere and always intruding in the present. Within our arenas of social work practice, we are continually building on and responding to the ideas and practices that came before us. At times we may do this intentionally with a critical and appreciative eye to what we are building on and what we are challenging. Oftentimes, however, history permeates the present stealthily. It does so through the implicit logic built into the operations of our organizations, the patterned ways of speaking about and relating to clients, and the everyday ways in which values and assumptions are translated into the action of social work. Jane Addams referred to this as “circles of habit,” and warned us in 1899 that “we are continually obliged to act in circles of habit based upon convictions we no longer hold.” History grooves our practice of the present with routines, with ways of being and doing through which we “naturalize” the arbitrary. When we take history seriously, we ask questions. How did we get here? What are we doing? Why are we doing it? Are there other possibilities?

History helps us understand how power works. A historical perspective provides us the opportunity to see who has the power to name and frame what counts as a problem and to develop strategies and mobilize resources for action. History inspires us to act. History reminds us that change is possible and that “ordinary” people, often in the face of tremendous adversity, can be powerful agents of change. It is through the stories of survivors and activists and the organizations and movements they have built and nurtured that we can not only find inspiration, but also concrete lessons for practice. It is through a critical embrace of history that we deepen understanding, identify patterns, and find courage to champion human dignity and rights in our everyday practice of social work.

Featured image credit: We are the people by Alyssa Kibiloski. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post State of the union for Social Work Month 2017 appeared first on OUPblog.

The significance of the Russian Revolution for the 21st century

The year 2017 marks the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, one of seminal events of the 20th century. The Russian Revolution “shook the world,” as the radical American journalist John Reed so aptly put it, because it led to the establishment of the Soviet Union, the world’s first socialist and totalitarian society. The Soviet regime’s example and its commitment to a world socialist revolution aroused passionate hope and enthusiasm and equally intense fear and loathing worldwide, depending on the audience, for seven decades, and those passions drove or had an impact on innumerable major global events.

There is, however, a neglected aspect of Russia’s 1917 upheaval that in the 21st century is more important than the Marxist socialist vision it once promoted. It is that the Russian Revolution marked, first, the high tide of Western influence in Russia and, second, the sharp reversal of that tide, a turnabout that began within months and continued unabated, despite a few weak countercurrents, for almost seven decades. Between 1985 and 1999, Mikhail Gorbachev and then Boris Yeltsin attempted to lead Russia back toward the West. But neither leader could overcome the Russian Revolution’s unrelenting undertow. Both Gorbachev and Yeltsin ultimately were swamped, and in 1999, with Vladimir Putin‘s rise to power, Russia’s anti-Western tide resumed its flow.

To understand why Western influence peaked and then quickly receded in Russia in 1917, it’s important to understand that what is known as the Russian Revolution consisted of three distinct but interlocked events. The first was the February Revolution of 1917 (according to Russia’s Julian calendar, which trailed the modern Gregorian calendar by 13 days) when Russia’s autocratic political system collapsed and was replaced by a democratic republic. The autocracy met its end primarily because of Russia’s involvement in World War I, which had produced almost three years of crushing military defeats and severe suffering for the country’s civilian population. The second event was the Bolshevik Revolution of October 1917 (again, according to the Julian calendar), when Russia’s fledging and fragile republic was overthrown in a military coup and replaced by a one-party dictatorship. The third was the three-year civil war the Bolshevik coup provoked. During that savage struggle, which was far more destructive to Russia than even World War I had been, the Bolsheviks retained power by defeating a loose coalition ranging across the political spectrum from monarchists to non-Bolshevik socialists.

“The Church’s Enemies” – an extract from Luther’s Jews

Set against the backdrop of Europe in turmoil, Thomas Kaufmann illustrates the vexed and sometimes shocking story of Martin Luther’s increasingly venomous attitudes towards the Jews over the course of his lifetime. The following extract looks at Luther’s early position on the Jews in both his writing and lectures.

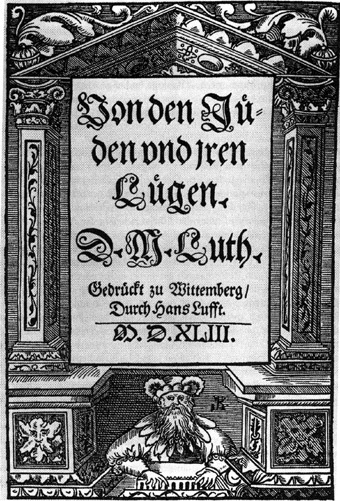

The topic ‘Luther and the Jews’ involves considering the important question of continuities between his earliest pronouncements, the programmatic text That Jesus Christ was born a Jew (1523), and his later texts, in particular Concerning the Jews and Their Lies (1543), which are extraordinarily polemical and hostile to the Jews. It is incontrovertible that the recommendations Luther makes regarding the Jews in the two texts named above differ fundamentally: If at first he advocated unconditional toleration of Jews within Christian society, later he advocated the expulsion of the Jews from the Christian countries of Europe, although this practical change in approach does not necessarily indicate a fundamental alteration of his theological position. Explaining this change will involve offering a complex of interrelated answers.

As far as theological continuities in his view of the Jews are concerned, Luther’s earliest comments are revealing, though it is important to take note of which statements Luther delivered from the pulpit or the university lectern to a Wittenberg audience and which occur in texts he wrote for a reading public spread over the whole German-speaking world, not to mention a readership educated in Latin. From the summer of 1520—in other words at the start of the phase of his life marked by the conclusion of his trial as a heretic in Rome and the promulgation of the Papal Bull Exurge Domine (15.6.1520) threatening him with excommunication—his writings clearly support a gentle, kind, and accommodating attitude towards the Jews. In this period in particular he was acutely aware of the sins and shortcomings of Christendom.

Frontispiece: On the Jews and Their Lies by Martin Luther, 1543. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Frontispiece: On the Jews and Their Lies by Martin Luther, 1543. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Luther’s earliest statements on this topic come from the context of the Reuchlin controversy. The Saxon court preacher and secretary Georg Spalatin had asked him via Johannes Lang, Luther’s friend and fellow member of his order, for a comment on this dispute and on the issue of whether the Hebrew scholar, Johannes Reuchlin, was, as the Cologne theologians accused him of being, a heretic. Luther’s verdict is undated but must belong to the period of his first lecture on the Psalms (1513/14), the Dictata super psalterium. He did not attempt to conceal his sympathy for Reuchlin and his position, decisively rejecting the suspicion of heresy. In response to the bigoted zeal of the Cologne theologians directed at ‘driving out Beelzebub’, in other words at making it impossible for the Jews to blaspheme, Luther pointed out that the blasphemies that issued from Christendom were a hundred times worse. All Biblical prophets, he wrote, had foretold ‘that the Jews will vilify and blaspheme against God and their King Jesus’ (maledicturos et blasphematuros). But the Scriptures had to be fulfilled; to prevent the blasphemies of the Jews was the same as claiming that the Bible was telling lies:

[F]or through the wrath of God they [the Jews] are condemned to being incapable of improvement, as the Preacher says (Ecclesiastes 1, 15), and any attempt at improving those who are incapable of improvement only makes them worse and never better.

From 1518 onwards Luther in various published writings had identified a closer connection between himself and Reuchlin and occasionally compared his own fate with his, although in the summer of 1521 he made a comment that dispelled any doubt that he considered the ‘Jewish books’ Reuchlin had tried to defend to be utterly base; he even confessed that he had been ashamed ‘that so much has been made of these worthless things [. . .] in the name of Christianity’. Luther’s firm theological convictions regarding the Jews, namely that they were the objects of God’s wrath, were corrupt, blasphemers of Christ, and followed worthless rabbinical interpretations that confirmed them in their errors, did not prevent him from making a stand in support of the great Hebrew scholar and advocate of Jewish rights.

In his first lecture on the Psalms Luther repeatedly returned to the topic of the Jews. They spurned Christ as mediator, he said, knowing nothing of God’s mercy and grace, and were trapped in the logic of their own notion of justice, in other words set on the idea that they could be justified in God’s sight by their own works. Their obduracy prevented them from understanding anything of the foretelling of Christ in the Old Testament. Their hopes for a Messiah and their complete devotion to the Law, in which they appeared to love God, were ‘of the flesh’, for they hoped only for temporal riches and their own good standing. The Talmud, he continued, had diverted them from a correct understanding of the Bible and confirmed them in the arrogant and mistaken claim to be the children of Abraham. They were an exemplar of God’s wrath, guilty of Christ’s death and thus dishonoured among all nations. The overall picture of Judaism painted by Luther in this lecture was strongly negative, though the lecture was not disseminated at that time.

Featured image credit: Martin Luther Pray Church of Our Lady by sharonang. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post “The Church’s Enemies” – an extract from Luther’s Jews appeared first on OUPblog.

March 28, 2017

Supporting and managing global health

Around the world, health is among the most important issue facing individuals, communities, governments, and countries as a whole. While there are increases in policy debates and developments in medical research, there are still many actions that can be taken to improve the picture of health at a global level. Following an event at Columbia University, we sat down with Chelsea Clinton and Devi Sridhar, authors of Governing Global Health: Who Runs the World and Why, for a video series to discuss the current public health landscape regarding inequalities, new innovation, philanthropy, and financing.

Are there rich countries that fail and poor countries that succeed in managing health?

What are some exciting innovations in global health happening today that should be better known by the general public?

How will the next generation of philanthropists effect meaningful change on a global level?

Are there organizations or microlenders that individuals can feel good about supporting?

Featured image credit: Cambodian boy receiving measles vaccine by CDC Global. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Supporting and managing global health appeared first on OUPblog.

Combating gendered violence in the face of right-wing populism

In my 2013 book, I noted a troubling trend in the trajectory of European Union policy. The 1990s and early 2000s had been characterized by important victories for a dynamic network of transnational feminists. Advocates from a wide array of countries utilized the various political opportunities of multilevel governance to push for European legislation framing gendered violence as a widespread problem in Europe. Furthermore, the network was able to secure invaluable resources aimed at facilitating the growth and capacity of advocacy organizations. A significant shift began, however, with the conservative turn of the Commission in 2004. In Commission documents, gendered violence was reframed in more narrow terms and focused on “cultural” forms of violence such as “honor killings” and “female genital mutilation.” In this new framing, less emphasis was placed on gendered violence as a “European” problem impacting women from all social locations, and more as something “foreign” or “imported.” The strongest and most comprehensive actions and initiatives addressing violence against women by the Commission during this time period were those aimed at addressing the issue in countries outside of the European Union, including prospective member states as well as developing countries receiving European foreign aid. Programming that had previously focused on building capacity throughout existing European member states was quietly defunded and/or folded into other initiatives.

This reframing of violence using simplistic and essentialist understandings of “culture” is harmful in several ways. First and foremost, this reframing is rooted in and reinforces xenophobic and racist discourses. The culturalization of violence serves to justify and further the marginalization of already vulnerable groups, positing “other” women as perennial victims and men as the “barbaric other” (a tendency noted in the seminal piece by Spivak 1988). Here, women’s rights and human rights discourse are co-opted to construct and racialize others as being apart from and less than. European culture is characterized as upholding women’s rights and “other” cultures are seen as violating them. If the concern is for women in immigrant and minority communities, feeding into these oppressive discourses is not making them safer. Using one axis of oppression to justify oppression along another dimension does not reduce, but increases the precarity of their societal positioning. Furthermore, it increases the precarity of all women. This shift to focusing on specific culturalized forms of violence is a shift away from the gendered violence broadly experienced by all groups of women. It is a reactionary unraveling of efforts to make gendered violence visible and denormalize the most common manifestations of it. Culturalized framing incorrectly locates gendered violence as occurring outside of “European” communities in direct contradiction to the plentiful evidence that gendered violence is indeed prevalent in even the most gender egalitarian of European countries. When gendered violence is no longer visible as a salient problem within European society, then it is easier to take away the necessary resources to combat it.

Fighting for women’s rights but ignoring or even allowing other forms of oppression to exist means that the movement is not truly fighting for all women’s rights.

Several years later, this toxic trend has continued, exacerbated by the growing resurgence of nationalistic populism and its accompanying xenophobia and racism. The economic crisis, followed by the refugee crisis have facilitated a rise in right-wing nationalism not only in Europe, but also in the United States. On both sides of the Atlantic we see the co-option and reframing of feminist and human rights discourses about gendered violence to further exclusionary agendas. During his campaign, then presidential candidate Donald Trump characterized Mexicans as rapists and then repeatedly called for building a wall to keep them out of the United States. After the shooting in a gay night club in Miami, he characterized Islam as incompatible with Western values and institutions, stating “Radical Islam is anti-woman, anti-gay, and Anti-American” before calling for a broad ban on Muslims coming into the United States. This rhetoric has continued since he has taken office, and has even utilized the unsubstantiated propaganda circulated by right wing groups in Europe, associating refugees with rising rates of rape in Sweden and Germany. At the same time Trump has been touting women’s rights and LGBTQ rights against immigrant groups, his administration has been swiftly undermining legislation and programs aimed at upholding these rights. One of his first executive actions cut the funding for the Violence against Women Act’s grant program. A month later his administration rescinded an important regulatory document establishing transgender protections under education policy. While seemingly inconsistent, these types of contradictions are characteristic of the culturalizing trend, as is the disconnect regarding the politician’s own alleged actions and attitudes towards women. The violence of the constructed other is pathologized, thus justifying their othering, while the violence of the dominant group is normalized and excused.

The seriousness of this trend and its detrimental impact on efforts to combat gendered violence should not be underestimated. It is imperative that advocates resist these exclusionary narratives. That resistance starts by reviewing the strategies, tactics, and discourse within social movements seeking to combat gender violence. Efforts that only focus on a the single-axis of gender oppression, miss the multitude of ways that gendered violence is experienced in concert with racism, xenophobia, homophobia, classism, and other forms of oppression. Prioritizing one dimension of oppression over others leaves a movement more vulnerable to having its message and cause co-opted. Fighting for women’s rights but ignoring or even allowing other forms of oppression to exist means that the movement is not truly fighting for all women’s rights. This not only undermines potential solidarities necessary for a strong movement, but it can become the basis for undermining the goal of combating gender violence altogether. Resisting this trend is imperative to effectively combating gendered violence.

Featured image credit: Protest Against DSK at the Cambridge Union Society by Devon Buchanan. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Combating gendered violence in the face of right-wing populism appeared first on OUPblog.

Abortion: conflict and compromise

A few years ago, when I told a colleague that I was working primarily on abortion rights, he looked at me quizzically and replied, “But I thought they had sorted all of that out in the seventies”. Needless to say, he was a scientist. Still, while the idea that the ethical questions implicated in abortion were somehow put to bed in the last century is humorous, I knew what he meant. The end of the ‘sixties and beginning of the ‘seventies marked watershed developments for reproductive freedom in both Britain and the U.S. – developments which have (with some non-negligible push and pull at the boundaries) continued to set the basic terms of abortion regulation ever since.

In Britain, the 1967 Abortion Act widely legalised termination of pregnancy for the first time and codified the grounds upon which abortions could be legally carried out. Shortly after, the 1973 Supreme Court decision Roe v Wade famously declared that there was a constitutionally protected right to abortion in the United States, albeit with some qualifications. Since those events, there have been no revolutionary changes to the system of abortion regulation on either side of the Atlantic, although there have been many meaningful ones.

Of course, legal resolution by no means signalled the end of moral disagreement about abortion. A significant minority voice has continued to vehemently oppose abortion practice. What was settled back then secured far more of a grudging détente than a happy compromise. (Like so much legislation, the Abortion Act was a product of political expediencies; I once heard one of its drafters describe the pandemonium of last-minute back-room deals in the Houses of Parliament, and the hotchpotch of provisions that emerged from all of the bargaining necessary to get it through.) As such, the political resolutions, whilst enduring, have always been intensely fragile, especially in the US where Christian conservatism and the anti-abortion lobby overlap so much. Of late, that fragility has become increasingly apparent. Recent developments in the United States and elsewhere have revealed just how misplaced any complacency about reproductive rights truly is.

Recent developments in the United States and elsewhere have revealed just how misplaced any complacency about reproductive rights truly is.

It is, in truth, hardly surprising that abortion compromise is so precarious when one considers the nature of dissent to abortion practice. If one side of that debate really believes—as many claim to—that abortion is murder, akin to infanticide, then it is hard to see how they can ever truly accept legal abortion merely on the strength of its democratic pedigree. Against such a belief, rehearsing the familiar pro-choice mantras about women’s rights and bodily autonomy is a bit like shooting arrows at a Chinook helicopter. For what strength does control over one’s body and reproductive destiny really have when measured against the intentional inflicting of death on another?

Of course, if ideological opponents of abortion rights really believe that abortion amounts to murder, it may be hard to make sense of some of the traditional exceptions they themselves have defended, in circumstances, for example, of rape or incest, or where the pregnancy endangers the very life of the pregnant woman. If killing the fetus is no less than homicide, then how can it be justified even in these dire conditions? We certainly do not permit the out and out killing of born human beings for comparable reasons. This may be an indication that opponents of abortion who make such concessions do not truly, deeply, believe the claim that killing an embryo or fetus is like killing a child. Alternatively, it may just suggest that such concessions are rarely ever authentic, but adopted merely as a matter of political strategizing, to avoid losing moderate support in the wider conflict. If that were true, it would be unsurprising to see those traditional concessions gradually withdrawn as opponents of abortion become emboldened by increasing success.

For what strength does control over one’s body and reproductive destiny really have when measured against the intentional inflicting of death on another?

Either way, defenders of abortion rights have a constant decision to make about how to respond to attacks on reproductive freedom and the denunciation of abortion as a moral horror. The approach most traditionally favoured, at least in public spheres, is to simply ignore all talk about abortion being murder and try to refocus attention on women’s stakes in abortion freedoms. As the Mad Men character Don Draper always quipped, “If you don’t like what’s being said, change the conversation”. This strategy can have its uses, but also its drawbacks. Most importantly, whilst reminding everyone of what women stand to lose through abortion prohibition is likely to strengthen the resolve of those sympathetic to abortion rights, it does nothing to address the consternation of those that are genuinely conflicted about the issue – who are not sure that abortion isn’t murder. As an effort to persuade avowed opponents of abortion rights to think again, it is even more pointless. For those who decry abortion as unjustified homicide do not usually need to be convinced that women can be hugely benefited by it, and harmed by its outlawing. That is not where their main ground of opposition ever lay.

It is for this reason that I think any effective defense of abortion rights must meet that opposition on its own terms, and confront the claims that abortion is homicide and the fetus the moral equivalent of a child. The task can seem daunting; how does one even begin to argue about whether or not unborn human lives have exactly the same right to life as mature human beings? But there are many reflections one can bring to bear on that question, and especially on the question whether, when examining our own or others’ beliefs, we are really committed to the claim that embryos are equal in moral value to human children. For one thing, as some philosophers have pointed out, if we really believed that claim, we may have to ask why infinitely more resources are not devoted to the prevention of natural miscarriage, which, it would follow, is the single biggest cause of child mortality – far greater than famine, disease, or war. At any rate, if defenders of reproductive freedoms do not concern themselves with the fundamental questions of abortion ethics, they are in danger of being left with little effective argument if and when the fragile settlements that have held for some decades threaten true collapse.

Featured image credit: ‘Question-mark-1495858’ by Qimono. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Abortion: conflict and compromise appeared first on OUPblog.

March 27, 2017

A hitch-hiker’s guide to post-Brexit trade negotiations

The UK has yet to decide what relationship with the EU it will seek following Brexit. But whatever option it pursues, the government’s ability to achieve its goals will depend on the success of its negotiating strategy. To design a successful negotiating strategy, it is first necessary to understand the purpose of trade agreements. When a country sets trade policy unilaterally, it does not account for how its choices affect the rest of the world. But because countries are interdependent, the effects of trade policy do not stop at national borders. In the language of economics, trade policy generates international ‘externalities’. And frequently these externalities lead to ‘beggar-my-neighbour’ effects, which make other countries worse off by lowering their terms of trade or reducing inward investment.

By negotiating trade agreements, countries can internalise the externalities resulting from international interdependencies, avoid damaging trade wars and improve welfare. Importantly, this is true regardless of whether policy goals are motivated by the desire to maximise economic output, the wish to protect particular groups of workers and firms, or the pursuit of other social objectives. Whenever policies have international spillovers that governments fail to internalise, there is scope for international agreements to make all countries better off.

To obtain these gains from international coordination, trade agreements require countries to give up unilateral control over some policies in exchange for other countries doing the same. For example, members of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) give up the right to use import quotas and production subsidies and agree limits on the tariffs that each country can charge on imports from other members.

Trade negotiations are not about countries identifying a common objective and working together to achieve it. They are not a cooperative endeavour. Instead, trade negotiations are a bargain between countries with competing objectives. Each country must give up something it values in order to obtain concessions from other countries. This observation leads to four principles the UK should adopt to guide its trade negotiation strategy:

1. You get what you give

To reap the benefits of trade agreements, the UK must be willing to give its trading partners something they value. In general, the more countries are willing to concede and the more policy control they give up, the bigger are the potential gains from reaching an agreement.

An important question the UK faces is what concessions it is willing to make in return for the EU allowing UK services firms to participate in the Single Market. Unless the UK makes a sufficiently attractive offer, the EU will take the opportunity Brexit presents to impose new barriers on UK services exports.

The fact that free trade agreements are based on mutual concessions also makes unilateral tariff liberalisation a less attractive policy because it would involve the UK giving away a potentially important bargaining chip.

An important question the UK faces is what concessions it is willing to make in return for the EU allowing UK services firms to participate in the Single Market.

2. Where negotiations start from matters

The outcome of any bargaining game depends on where negotiations start from. Trade agreements are no exception. The policies each country will adopt if no agreement is reached provide a reference point – or ‘threat point’ – for the negotiations. Countries make concessions starting from this reference point.

It is unclear whether the reference point for UK-EU negotiations will be the status quo where the UK is a member of the Single Market, or trade under WTO rules. Starting from the status quo, the UK would have to negotiate the right to impose restrictions on immigration from the EU. Starting from WTO rules, the UK would not need to negotiate immigration restrictions, but would need to bargain for access to the Single Market.

Before any trade negotiations between the UK and the EU take place, there will have to be an understanding reached on what the reference point is. The UK should seek a reference point that helps in achieving its post-Brexit objectives.

3. Bargain from a position of power

Bargaining power affects the outcome of trade negotiations. Countries that have little bargaining power are less likely to achieve their objectives. Unfortunately, the UK is starting from a weaker position than the EU. Because UK-EU trade accounts for a much larger share of the UK’s economy than the EU’s economy, the UK needs a deal more than the EU does.

The weakness of the UK’s position is exacerbated by the two-year time limit on exit negotiations under Article 50. As the two-year limit approaches, the UK will become increasingly desperate to obtain an agreement. There are two steps that the UK should take to improve its bargaining position. First, delay triggering Article 50 until the government has decided its post-Brexit objectives and EU leaders are ready to start negotiations. Theresa May’s decision to invoke Article 50 in early 2017 before the French and German elections weakens the UK’s position, because the EU will not be able to participate in meaningful negotiations until after these elections.

Second, the UK’s immediate objective after invoking Article 50 should be to neutralise the two-year time limit by agreeing a transition arrangement to govern UK-EU trade relations during the period between when the UK leaves the EU and when a longer-term agreement is concluded. Returning to the principle that you only get what you give, the UK needs to decide what it is willing to offer the EU in return for a transition agreement.

4. Invest in negotiating capacity

Trade agreements involve many simultaneous policy changes making it difficult to analyse their economic consequences. Smart negotiators use this uncertainty to their advantage by ensuring they are better informed than their opponents about who stands to gain and who stands to lose from any policy proposal.

Having not participated in trade negotiations for the past 40 years, the UK currently has very little negotiating capacity. To become a smart negotiator, the UK needs to invest heavily in four areas of expertise: trade lawyers to conduct negotiations; diplomats to provide information on the objectives and strategies of its negotiating partners; business intelligence to understand how firms will be affected by different policies; and trade economists to quantify the welfare effects of proposed trade agreements.

Since the UK joined the EU in 1973, trade policy has played a minor role in UK politics. Now it’s back. Much has and will continue to be written about what the objectives of post-Brexit UK trade policy should be. But whether the UK is able to achieve the objectives it eventually chooses, will depend on the success of its negotiating strategy. By adopting these four principles the government can ensure it makes the best of a bad hand.

A version of this post was originally published on the LSE blog.

Featured image credit: architecture banking building by PublicDomainPictures. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post A hitch-hiker’s guide to post-Brexit trade negotiations appeared first on OUPblog.

Birds’ eye views – a question of reality

“Bird’s eye views” are everywhere; they really are two-a-penny. At the click of a mouse we can view any location on the globe from an aerial perspective. A news story is not complete without looking down on the scene from a helicopter or satellite; a bird’s eye view is now considered essential for putting everything in context.

A finger on a touch pad can glide us across the globe; we can casually sweep from the view that an albatross apparently gets as it flies to its nest site in South Georgia, to what a vulture apparently sees when looking for carrion in Tanzania’s Ngorongoro Crater. The notion that these really are bird’s eye views is deeply engrained. When we use the term “bird’s eye view”, we actually think that this is how the world looks to a bird.

A recent advertising stunt for a new miniature video camera used a tame white-tailed eagle. From a camera strapped to its back, the scene below was filmed as the bird was released from the Eiffel Tower. The strap line read, “The 100% authentic eagle eye view”.

But what did this eagle actually see? Was the video really giving us a glimpse of what the eagle saw? Would a dove, a vulture, or an albatross see the same thing as the eagle? Would any of them see the same thing as the digitised images in the advert?

The key question is do birds, whether on the ground or in flight, see the world through the same eyes as us? Do any other animals see the world as we do? Is our eye view unique?

It is a rather old and fundamental question. First raised by the Greek philosopher Epicurus, it cuts straight to that troublesome idea of “reality”. Pondering how the world appears to other animals asks the most uncomfortable of questions, “what can we actually know about the world?”

Eagle view from Eiffel Tower. Image by Sony/SWNS from Chapter 1 of The Sensory Ecology of Birds. Used with permission from Graham R. Martin.

Eagle view from Eiffel Tower. Image by Sony/SWNS from Chapter 1 of The Sensory Ecology of Birds. Used with permission from Graham R. Martin.Philosophers and artists, and now social media discussions, have regularly pondered the nature of reality. However, these musings are nearly always couched in the terms of stripping away personal and cultural biases. Such stripping will allow us to see things “as they really are”. The assumption is that we need to see things fresh, not how we have been trained to see them. For many people who ponder such questions, the ultimate aim is to experience an epiphany, “to see things through new eyes”. It is the touchstone of every aspiring artist. For some people the quest for new ways of seeing can be achieved with a little help from meditation or drugs. But to me those are likely to obscure rather than reveal.

While the idea that culture and learning poses limits on ways of seeing is important, there is a much broader perspective on reality: one which sees us embedded in our evolutionary history. This perspective sees us as just one type of animal that, like all others, has evolved to gather only certain information from the world about them, information that natural selection has honed to become crucial for the survival and reproduction of each particular species. Crucially, that information is always partial with respect to all that the world offers; it is never comprehensive.

Thus, try as we might to achieve that epiphany, we are trapped in a particular reality that is the product of our evolutionary history. This history has produced a unique suite of muscles and bones which a palaeontologist uses to define us as a species, but that same history has also produced a unique suit of senses that extract, or filter, particular information from the world about us. It is information which ensures sufficient control of our body for our survival and reproductive success.

Modern explorations of the senses of other animals, including my own work investigating the senses of more than 50 birds species, now show us just how specialised our own view of the world is. Reality becomes a very flexible concept when we start to compare the information that we have available through our senses, with what is available to other species. The bird’s eye view soon evaporates into just a lazy metaphor. A camera strapped to an eagle’s back shows us just a view of the world as seen from a camera strapped to an eagle’s back; it does not give us an eagle’s eye view.

The sensory worlds of birds are particularly intriguing because it is so easy to think that what we see, they also see. It is easy to assume that birds see the world as we do; the only difference is they see it from a different location. We are seduced into believing birds apparently share the same world with us. After all they live alongside us and have the same sensible habit of completing activities in day light. When birds are active at night this is seen as something strange or quirky, needing special explanations.

These similarities between us and birds are seen as so obvious that we readily anthropomorphise them. Nearly every TV wildlife documentary portrays birds’ lives as exemplars of human challenges and dilemmas. We should forget these metaphors and try to understand what real birds’ eye views are. It then becomes clear that the information available to every species, including ourselves, is different. Each species defines its own reality based upon sensory information that is both highly filtered and partial.

Featured image credit: Images in photo montage provided by the author and used with permission.

The post Birds’ eye views – a question of reality appeared first on OUPblog.

Orlando: An audio guide

In honor of Virginia Woolf’s death (March 28, 1941), listen to Dr Michael Whitworth, editor of the Oxford edition of Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, introduce the novel, and discuss Woolf’s life and times in this Oxford World’s Classics audio guide.

“I feel the need of an escapade after these serious poetic experimental books…I want to kick up my heels and be off.”

Orlando tells the tale of an extraordinary individual who lives through history first as a man, then as a woman. At its heart is the figure of Woolf’s friend and lover, Vita Sackville-West, and Knole, the historic home of the Sackvilles. Orlando mocks the conventions of biography and history and wryly examines sexual double standards.

Listen to this audio guide to learn more about Virginia Woolf’s private life; her relationship with Vita Sackville-West, and mental health, her place in the modernist movement, and why writing Orlando was so important to this pioneering author.

Featured image credit: Featured image credit: “Istanbu, church…” by waldomiguez. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Orlando: An audio guide appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers