Oxford University Press's Blog, page 384

April 3, 2017

Filling Supreme Court vacancies: political credentials vs. judicial philosophy

In the current, hyper-partisan environment, relatively few individuals publicly supported the confirmations to the US Supreme Court of both Justice Samuel A. Alito, Jr., and Justice Sonia Sotomayor. I know because I am one of these lonely souls. Now, the same considerations which led me to support their confirmations lead me to support the confirmation to the Court of Judge Neil Gorsuch.

To the many who view the Supreme Court in purely partisan or ideological terms, this pattern is inconsistent, if not bizarre. For those who prize the rule of law in our deeply polarized society, this pattern is compelling.

The US Supreme Court serves two institutional roles, ultimately in tension with each other. The Court is literally the third branch of government. Article III of the US Constitution commands that “[t]he Judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one Supreme Court” whose “Judges…shall hold their Offices during good Behavior.” Article II provides that these “Judges” of the Supreme Court shall be appointed by the nation’s politician-in-chief, the President, and confirmed (or not) by the politicians who sit in the US Senate.

Reflecting its political nature, the Court has often played a controversial role in the nation’s affairs. The Court’s ‘Dred Scott’ decision, for example, exacerbated the regional tensions which culminated in Abraham Lincoln’s election to the Presidency and the Civil War.

But the Court is also the repository of our deeply-held commitment to the rule of law. As I explained when I supported the confirmation of the Democratic liberal Sotomayor after favoring the confirmation of the Republican conservative Alito:

Courts are where Americans go for the fair, principled application of law administered by a judge who is guided, not by the identity of the parties, but by legal norms and standards. All too often, the reality falls short of this ideal. Nevertheless, this ideal is an important part of America’s self-image and of our success as a nation: We believe in the rule of law. Our judges should thus be more than partisans. They should be legal professionals in the best sense of that term, knowledgeable, hardworking craftsmen who seek to administer the law in a fair and principled fashion. This commitment to professionalism should start with the judges at the pinnacle of the legal system.

This was true when President Obama appointed then-judge Sotomayor to the nation’s highest court. It is if anything, even more true today.

The relevant question in such an environment is whether the president has selected a nominee of professional distinction, one whose credentials and demeanor reinforce the rule of law.

Given the political role of the Court, a President and Senate of the same party will appoint and confirm a justice acceptable to the main interests of that party. Thus, when President Obama served with a Democratic Senate and President Bush served with a Republican Senate, their nominees to the Court were going to be compatible to the major elements of their respective parties. So too today, President Trump with a Republican Senate will place on the Supreme Court a justice acceptable to important Republican interest groups.

In such an environment, rule-of-law considerations come to the fore and the relevant question becomes the professional credentials of the nominee. Judge Gorsuch’s credentials comfortably qualify him to sit on the nation’s highest court.

This does not mean that I agree with every decision Judge Gorsuch has made or is likely to make – just as I have not agreed with every decision of Justices Sotomayor and Alito. In light of their ideological differences, it would not be possible (or desirable) to agree with every decision of these two justices with different judicial philosophies.

The question today is whether, from the group of politically realistic nominees, Judge Gorsuch brings to the Court the professional qualifications which reinforce the rule of law. He does, as did then-judges Alito and Sotomayor.

Many distinguished observers find this emphasis on professional credentials, rather than judicial philosophy, unpersuasive. Indeed, these observers would suggest that my focus on professional credentials is naive.

I suggest that it is these observers who are naive. A Republican president with a Republican Senate is going to place on the Court a conservative nominee, just as President Obama and a Democratic Senate placed on the Court two liberals, Justices Sotomayor and Kagan. The relevant question in such an environment is whether, from among the pool of politically realistic nominees, the president has selected a nominee of professional distinction, one whose credentials and demeanor reinforce the rule of law. Judge Gorsuch – like Justices Sotomayor, Alito and Kagan – passes that test, and thus should be confirmed to the Supreme Court.

Featured image credit: The inside of the United States Supreme Court by Phil Roeder. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Filling Supreme Court vacancies: political credentials vs. judicial philosophy appeared first on OUPblog.

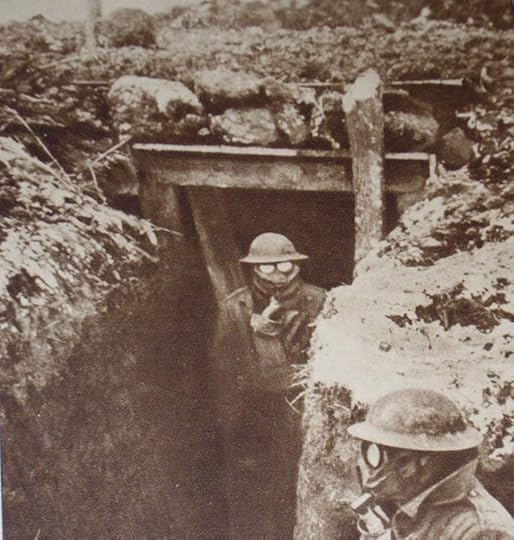

Speaking truth to power: poetry of the First World War [extract]

The well-worn argument that poets underwent a journey from idealism to bitterness as the War progressed is supported by [poet and veteran David] Jones, who remembered a “change” around the start of the Battle of the Somme (July 1916) as the War “hardened into a more relentless, mechanical affair.” Many poets experienced this fall, out of a world where gallantry and decency might still be possible and into an inferno of technological slaughter. Yet the complexity of individual cases reveals just as many exceptions. Elizabeth Vandiver has noted that the majority of soldiers, as well as civilians, “continued to write in unironic terms about duty, glory, and honour throughout the war and afterwards.” Neither Georgianism nor the Somme cured every soldier of grandiose sentiment. The poet Arthur Graeme West expressed his bewilderment at the mismatch between the sight and stench of the dead, “hung in the rusting wire,” and the ornate idiom with which even those “young cheerful men” who had “been to France” continued to describe their experiences. Gilbert Frankau’s “The Other Side” made the point even more bluntly by attacking “warbooks, war-verse, all the eye-wash stuff | That seems to please the idiots at home.” “Something’s the matter,” Frankau’s speaker tells one of these naïve versifiers: “either you can’t see, | Or else you see, and cannot write.”

The soldier–poets who were capable of seeing and writing are often credited with having been “anti-war,” and their works are routinely recruited for propaganda by campaigners opposed to later conflicts. In accounts of the War and the art that it inspired, futility has defeated glory as the appropriate response, and Wilfred Owen has become the antidote to Rupert Brooke (who, it is often argued, would have come round to the right way of thinking if he had lived long enough). This risks damaging the achievements of the soldier–poets, because it neglects the extent to which their writings struggle with contradictory reactions to the War. Owen’s description of himself as “a conscientious objector with a very seared conscience” captures the internal divisions of the pacifist who fights, or the officer who (like Owen) acknowledges both the horrors of the War and the undeniable exhilaration and “exultation” that battle occasionally inspires. Even in his most anthologized poem, “Dulce et Decorum Est,” Owen does not subscribe to an anti-war manifesto. Like Frankau and West, he writes what can be more accurately labelled as anti-pro-war poetry, reminding civilians that the “high zest” with which they convey their martial enthusiasms is based on ignorance of the terrible realities: “dulce et decorum” it is certainly not , to die in a gas attack with blood “gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs.” Most soldier–poets—like most soldiers—believed the War to be necessary, but wanted the costs acknowledged and the truths told.

Image credit: “Americans wearing gas masks during World War I” by William E. Moore. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: “Americans wearing gas masks during World War I” by William E. Moore. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.How to tell truths to those in whose name they fought continued to be a vexed question. Having already disapproved of Sassoon’s Declaration against the War, Graves advised Owen: “For God’s sake cheer up and write more optimistically—The war’s not ended yet but a poet should have a spirit above wars.” But on one issue, at least, the surviving veterans could agree: their experiences had set them apart from non-combatants. As Richard Aldington reported, “there are two kinds of men, those who have been to the front and those who haven’t.” Whatever truths the soldier–poets brought back from the battle zone, they laid claim to a knowledge beyond the reach of civilians. A literate army drawn from all social classes was at last empowered to speak for itself with a fluency of which no previous army had been capable. Fortified with his new authority, the soldier–poet profoundly disrupted long debates about the nature and efficacy of poetry itself. Plato wanted to banish poets from his ideal republic because they were liars, lacking knowledge and deceiving with artful language. The figure of the soldier–poet reunited art and ethics, and undertook new obligations by speaking the truth to and about power. When Owen insisted, “Above all, I am not concerned with Poetry,” he artfully rebuked the artful language that Plato condemningly ascribed to poets. “The true poet,” Owen went on to explain, “must be truthful,” not least because the official language of the state and its media had become untrustworthy.

Featured image credit: “Wire” by Dimitris Vetsikas. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Speaking truth to power: poetry of the First World War [extract] appeared first on OUPblog.

Giving up on (indirect) Discrimination Law

Some readers might be surprised if told that one of the most significant cases on discrimination law generally, and race discrimination in particular, is likely to be decided by the Supreme Court before long. The UKSC heard the appeal against the Court of Appeal’s ruling in Home Office v Essop (2015) in December 2016. It is still to deliver its judgment. Readers can look up doctrinal niceties in a note on this case [132 Law Quarterly Review (2016) 35]. In this post, I wish to discuss its broader policy implications.

These are the facts: the Home Office administered a generic (i.e. not tailored to the actual job) Core Skills Assessment (CSA) as a first step towards determining its staff’s eligibility for promotion. The CSA selection rate for non-white candidates was 40.3% of the rate for white candidates, and there was a 0.1% likelihood that this could happen by chance. The selection rate of over-35 year olds was 37.4% of the selection rate for under-35 year olds, and again there was only a 0.1% risk that this could happen by chance (at [6]-[7]). Given these findings, there must have been some non-random explanation for the disproportionate impact of the CSA on non-white and older staff. However, neither the Home Office nor the claimants knew what this explanation was. The existence of an explanation was almost (99.9%) certain, what was lacking was the knowledge of what that explanation was. If one is permitted some jargon, the problem was epistemological rather than ontological: or, if you prefer, the Court of Appeal (CA) was confronted with a ‘known-unknown’. Could the claimants establish prima facie indirect discrimination in this case without showing what the explanation was? Sir Colin Rimer, writing for the CA, held that they couldn’t.

If affirmed, this outcome could reverse a significant turn in Anglo-American discrimination law that started with the decision of the US Supreme Court in Griggs v Duke Power Company (1971). In that case, an employer’s requirement of a graduation degree for a job—whose satisfactory performance bore no relation to one’s being a graduate, but one that had the effect of excluding most black candidates (disparate impact)—was deemed unlawful under the Civil Rights Act 1964. The concept of disparate impact was imported into the UK Sex Discrimination Act 1975 and Race Relations Act 1976 as ‘indirect discrimination’ (Hepple, p 608-9).

Ever since Griggs, claimants have only borne the burden of establishing disparate impact caused by the policy, practice or criterion in question, never the burden of also explaining that the disadvantaged suffered was because of their race. Sure, courts have often taken judicial notice of plausible factors associated with race, such as poverty, inadequate access to education, living in an under-achieving neighbourhood, absence of role-models, lack of friends and relatives who can pass on the cultural capital necessary for success etc. But they don’t ask claimants to establish that they failed because of their race, or a factor associated with race, rather than for other reasons (such as laziness, incompetence, lack of intelligence, failure to turn up on time for the exam and so on). After the claimant has made a prima facie case by showing disparate impact, the burden shifts to the defendant, who can still defend the policy by showing that it is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim. The CA, in Essop, changes this long-established doctrine by placing the burden not only of causation, but also of explanation, on the claimant. It does so by appealing to the ostensible conceptual impossibility of proving causation without explanation [59], even though this is very much possible: popping an aspirin causes my headache to go away, whether or not I can explain precisely why that happens; asbestos is a known carcinogen, even though scientists cannot quite explain how it causes mesothelioma.

If confirmed, this judgment could have very serious consequences for the future of indirect discrimination law

If confirmed, this judgment could have very serious consequences for the future of indirect discrimination law, whose entire point is to unearth and redress discrimination that is typically harder to detect, let alone explain. In indirect discrimination litigation, given the aggregate nature of the claims, it is hard enough for information-poor claimants to establish causation. The burden of explanation will all but kill the chances of a successful litigation in most cases, except those where an explanation is obvious (women and inflexible working hours, Sikh men and a turban ban etc). This is especially pernicious in the context of race (and, no doubt, other grounds) where indirect discrimination mainly occurs due to existing socio-cultural, political, and material disadvantages faced by a group. These disadvantage-based factors tend to be multiple, diffused, and affect everything we do, but in subtle ways: they include the postcode we live in, the schools and universities that we (and our parents) go to (if we/they do), the monthly income of our families, the social networks we have, the material and cultural capital we inherit and so on.

The move beyond what is still commonly understood by many laypersons as discrimination—direct, prejudicial, motivated—to indirect, structural, unconscious impacts on disadvantaged groups marked a remarkable shift in the legal meaning of discrimination (Khaitan, 2015, pp 1-4). In particular, this was a shift from conceptualising discrimination as something that happens in the mind of the discriminator to thinking of the phenomenon as experienced by its victims. The law moved away from a strict corrective justice model of reacting to wrongdoing, towards a hybrid-model, where a corrective justice structure was retained to serve broader distributive justice ends (Khaitan and Steel forthcoming). This move towards a hybrid model for indirect discrimination was reinforced by including a broad justification defence, making the possibility of damages exceedingly rare, and allowing the regulator to bring a claim.

The CA’s judgment in Essop seeks to turn the clock back on this development. By requiring the claimants to provide an explanation for their failure, it seeks to reimagine indirect discrimination in the image of direct discrimination: discrimination as bad for bad reasons rather than for its bad effects. Going back to this older, narrower, meaning would be a significant reversal of hard-won gains.

This article was originally published on the UK Constitutional Law Blog, 13th March 2017.

Featured image credit: ‘Ball-round-alone-different’ by SplitShire. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Giving up on (indirect) Discrimination Law appeared first on OUPblog.

April 2, 2017

Trump’s “America first” foreign policy and its impact on the Liberal Order

Where will he take the United States? That is Donald J Trump – now 45th President of the United States. And will the Liberal Order, a product of all his predecessors, survive the Age of Trump? For over seventy years US Presidents and foreign policy officials of numerous American administrations have led – for better and for worse – the Liberal Order. One of the key chroniclers of this Liberal Order has been John Ikenberry. For Ikenberry, and other IR scholars, the evolving Liberal Order was first an international system, at least in the West, led by the its most powerful state, the United States. And then after the fall of the Soviet Union it was a single encompassing global order led by the surviving superpower, the United States. As one of Ikenberry’s close colleagues, Daniel Deudney, examining Ikenberry’s most well-known treatise on the Liberal Order, titled Liberal Leviathan described the book this way:

Across the twentieth century, and particularly after World War II, the United States pursued a foreign policy that played a central role in the creation of an international order based on rules, the consent of the governed, and capitalist economic expansion. While certainly not encompassing all the states of the global international system, this liberal international order has been immensely successful in advancing peace, prosperity, and freedom, to the great benefit of much of humankind.

From President Bill Clinton, through several recent presidents and numerous US foreign policy makers, the United States stood out in the international order as the ‘indispensable nation’, but Donald Trump has brought that to a screeching halt with his ‘America First’ rhetoric. Today, America’s foreign policy appears to be built on highly nationalist, even populist prescriptions. So, the global leader, indeed the primary mover of the Liberal Order, the United States has become potentially the destroyer of the Order it built.

The open question therefore in these early days of the Age of Trump is whether the Liberal Order is just being challenged but likely fixable and sustainable, or is it about to ‘topple over’? And if it does crumble, what replaces the Liberal Order? Tom Wright examining the Trump Administration in its earliest foreign policy efforts concludes: “The bottom line is that the president is an ideological radical who would like to revolutionize US foreign policy but he is largely alone in his intention. He faces opposition from almost all quarters.”

Trump foreign policy is difficult to determine. Rhetorically it is often nationalist and certainly aggressive; yet at other times, it is more reassuring and traditional. In still other statements the ‘America First’ approach is very ‘hands off’ and at arms-length, especially to America’s allies. Stewart Patrick of the Council on Foreign Relations recently sketched out a series of alternatives to the current Liberal Order. The approaches he describes range from the potentially collaborative though ad hoc, through a return to highly nationalist spheres of interest approach, or even more isolationist architectures. Indeed, given the President’s ‘America First’ rhetoric, it appears that the only consistent aspect is its nationalist character. A unilateralist and nationalist architecture of some form is likely to emerge. Indeed, Niall Ferguson the recent biographer of Henry Kissinger has suggested in The American Interest that the Trump Administration may well resurrect, the foreign policy behavior of an earlier Republican President, Theodore Roosevelt:

The open question therefore in these early days of the Age of Trump is whether the Liberal Order is just being challenged but likely fixable and sustainable, or is it about to ‘topple over’? And if it does crumble, what replaces the Liberal Order?

It seems clear that, like Theodore Roosevelt, Trump conceives of an international order no longer predicated on Wilsonian notions of collective security, and no longer expensively underwritten by the United States. Instead, like Roosevelt, Trump wants a world run by regional great powers with strong men in command, all of whom understand that any lasting international order must be based on the balance of power. In short, Trump already has more than he knows in common with Roosevelt. … “In a world regulated by power,” Kissinger argued, “Roosevelt believed that the natural order of things was reflected in the concept of ‘spheres of influence,’ which assigned preponderant influence over large regions to specific powers.”

Whether such an approach is congenial for President Trump and his close advisors, or whether it even accurately represents Roosevelt foreign policy, the reality of the global order architecture is apparently going to be quite distinct from the recent past.

Take but one example – the G20. Under the G20 umbrella the largest established and emerging market states meet annually. Leaders continue to gather to address the challenges of the global economy and consensus has been built around free trade, open markets, and the rule of law, all ideas long central to the Liberal Order that the US built. Writing on 13 March in Project Syndicate, the German Finance Minister, Wolfgang Schäuble suggested the key role for the G20:

In my view, the G20 is the best forum for increased and inclusive cooperation. Of course, the G20 is not perfect, but it is the best institution we now have for achieving a form of globalization that works for everyone. Through it, the world’s main industrialized and emerging countries have worked together toward constructing a shared global order that can deliver increasing prosperity. Indeed, the G20 is the political backbone of the global financial architecture that secures open markets, orderly capital flows, and a safety net for countries in difficulty.

And yet very recently, following the first meeting of President Trump and Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel and the G20 finance ministers and central bankers in Baden-Baden Germany, the US blocked a simple statement “to resist all forms of protectionism”, which up until this gathering was a standard principle of the G20 and the Liberal Order. The only certainty today: the future of the Liberal Order is very uncertain.

Featured image credit: “President Trump” by oriana.italy. Public Domain via Flickr.

The post Trump’s “America first” foreign policy and its impact on the Liberal Order appeared first on OUPblog.

April 1, 2017

What has happened to environmental protection?

Something unsettling has happened to environmental protection in the United States. It has lost its status as a value deep enough to power political consensus. Compare the early days of political action on the environment with today: in 1970, Richard Nixon—an astute politician, but not an environmentalist—said in his State of the Union Address:

“We still think of the air as free. But clean air is not free, and neither is clean water […] Through our years of past carelessness we incurred a debt to nature and now that debt is being called.”

That year he established the Environmental Protection Agency. In the same year, the Senate passed the monumental Clean Air Act by a vote of 73 to 0, and the country celebrated its first Earth Day.

Fast forward to 2017: with a few possible exceptions, Congress hasn’t addressed any significant environmental problems for over a quarter century and has blocked important environmental legislation; President Trump has promised to gut the EPA; and its new administrator, Scott Pruitt, as Attorney General of Oklahoma, sued the Agency over and over again to kill major environmental regulations.

At first blush, the political shift may seem baffling. For one thing, a majority of the American public identifies environmental protection as a societal value. For another, health statistics gathered over many years show that the improved air and water quality Americans now enjoy is a result of the environmental laws enacted in the 1970s. They are widely credited with greatly reducing asthma, drinking water contamination, and a host of other costly health consequences of a previously underregulated environment.

Why did this turnabout happen? Although there are many reasons, two stand out and they are ironic: first, the success of the environmental laws (a good thing), which enabled complacency; and second, on the subject of climate change—the single most important environmental threat of this century—the dogged insistence by the press on balanced reporting. This is also generally a good thing, except that it can create confusion in the public’s thinking and enable manipulation by parties benefitting economically when they are not required to limit the pollution causing rising global temperatures. Let’s unpack these.

“We still think of the air as free. But clean air is not free, and neither is clean water […] Through our years of past carelessness we incurred a debt to nature and now that debt is being called.”

Complacency: in 1969, Ohio’s Cayuga River caught fire because of all the garbage and industrial waste dumped into it. Los Angeles regularly had smog alerts as automobile exhaust sat in the city’s air basin. These and other obvious and alarming symptoms of pollution (with help from Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring a few years earlier) propelled the environmental movement and the bipartisan legislation that poured out of Congress in the 1970s. Not just the Clean Air Act, but also the Clean Water Act, the Safe Drinking Water Act, the Endangered Species Act, and other blockbuster laws were passed without serious congressional opposition. Their success was real. The Endangered Species Act brought back the bald eagle. The Clean Water Act made Boston Harbor clean enough to swim in again. The Safe Drinking Water Act made American public water supplies among the safest in the world. Having experienced few shocking environmental problems since the passage of these laws, Americans today by and large take the environment for granted. This has allowed politicians to hunker down on behalf of powerful corporate voices, rather than maintain legislative vigilance.

But this complacency ignores two facts. First, the environmental challenges we face today are largely imperceptible. We don’t fear them as we do a river on fire or air so dirty you can’t see the building across from your balcony. The greenhouse gases responsible for climate change are usually odorless, tasteless, and invisible. The same holds for nanopollutants in cosmetics and waste pharmaceuticals from medicine cabinets (or eliminated in our urine). Second, environmental protection is not a one-time job. It requires the oversight and monitoring of state and federal regulatory agencies, starting with the Environmental Protection Agency, and occasional intervention by Congress to meet new or newly discovered challenges. An example is hydrofracking, which was on no one’s radar in 1970. The environmental problems it can create, such as contamination of groundwater and drinking water, aren’t easily addressed in existing environmental laws. But efforts to amend the Safe Drinking Water Act for that purpose have been stymied in Congress by the petrochemical industry.

Balanced reporting: a hallmark of democracy is a free and probing press. But a responsible press also needs to protect the public from points of view that skew important issues, or worse, are designed to manipulate public opinion. Reporting on climate change has too often shirked this responsibility. There is near-universal agreement among the scientific community that climate change, caused largely by carbon dioxide emissions, is occurring and creating an existential threat to the planet. And yet the media often present contrary views by climate deniers and a tiny minority of scientists that leave readers and listeners with an inaccurate takeaway about the urgency of the problem. Politicians thus get cover for shying away from legislative fixes that might anger their corporate backers. And Administrator Pruitt is enabled to say about carbon dioxide, “I think that measuring with precision human activity on the climate is something very challenging to do, and there’s tremendous disagreement about the degree of impact, so no, I would not agree that it’s a primary contributor to the global warming that we see.”

Let’s hope it doesn’t take a full-blown catastrophe to cut through public complacency and provide the press with a disaster story so scientifically unambiguous that it can’t be denied, and Congress with a mandate it can’t dodge. But we shouldn’t need a 21st century version of a river on fire—a city under water?—to speak and act responsibly on behalf of the environment.

Featured image credit: “Earth, Globe, Water” by geralt. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post What has happened to environmental protection? appeared first on OUPblog.

Diverse books in school libraries

Diversity continues to be a huge topic in the media. Each year seems to spark new debates about everything from the racial makeup of award nominee lists, to the people who are allowed into different countries. The wave of popularity surrounding this subject impacts upon every sphere of life and culture, including books and libraries.

Campaigns have sprung up like #WeNeedDiverseBooks, aiming to highlight a perceived lack of diverse books—books that reflect a wide range of backgrounds and experiences, including class, race, culture, sexuality, ability, etc. or that are written by people from these backgrounds—currently being published. Many of these campaigns also discuss the ways in which people can get hold of diverse books through bookshops, schools, e-stores, and through libraries.

In the last few months I’ve spoken to over 100 UK school librarians for a research project. The project aimed to establish the value of diverse books for young people, the impact their presence in libraries can have, and the barriers librarians face when they want to stock these books.

The value of diverse books

There is plenty of academic evidence, both research-based and anecdotal, to support the importance of diverse books, but the best illustration I found came from an interview I conducted with a secondary school librarian, who told me how she introduced one student to a book about a young, black girl.

I remember two years ago…there was this girl, she came with an English teacher in language skills, and she had to read but she didn’t really want to. And I found this book and she loved it…I was so pleased because I’ve found a way of showing [her] that books could be fantastic, and sometimes teenagers need to identify, so why not start with these sorts of books?

This was echoed by other school librarians. One respondent talked about a student from an Irish background who liked the Irish authors in the library, and also mentioned that a girl whose brother has autism had thanked her for stocking books about disabled characters.

Of 106 people who responded to a survey I conducted, 77% said they always or often considered whether the books they selected for their library represented diverse groups. Many of those that only sometimes or rarely considered diversity when selecting books, cited barriers including lack of appropriate material, and limited time, and budget.

The impact of diverse books in libraries

As authoritative, trusted, respectable establishments, libraries are an important venue for featuring diverse books. When libraries include diverse books on their shelves and promote these books to their members, they are doing three very important things.

First, they are giving visibility to diverse books and the communities they represent, something that academics like Vygotsky agree can positively influence people’s self-identity or perceptions of others, especially while they’re young.

Second, as the American Library Association explains, they can give legitimacy by including substantial collections of material about different cultures, which helps to frame discussions, provides a basis for factually accurate debates, and demonstrates that diverse groups are complex and influential within society.

“Librarians still struggle to find the range, quality, and availability of books they want.”

Third, libraries make books accessible to all people, including those who might not normally be able to read, but would benefit from diverse literature. This expands the demographic that can be exposed to diverse books, and to the benefits of education and legitimacy mentioned above.

The barriers facing librarians

The idea of having a wide range of diverse books available in every library, especially in light of the positive impacts they can have, is a desirable one, but it is also easier said than done.

Availability

The first barrier is finding diverse books. One librarian showed me a list of diverse books that a student had requested, and said: “It was really hard. I have not got everything on this list from my supplier…They just didn’t have them.”

In the past, publishing in this area was very limited, and although this has improved recently with the popularity of authors like Juno Dawson and Malorie Blackman, librarians still struggle to find the range, quality, and availability of books they want. This hasn’t been helped by recent cases of diverse books failing to gain recognition in the prestigious prize lists that librarians often rely on when choosing stock.

Interference and complaints

The second barrier is the perception of these books by gatekeepers like parents and governing bodies. 11% of school librarians surveyed, reported complaints about books from staff members or parents. A popular response was to debate with complainers, and to refer them to selection policies. Having robust policies in place, especially when approved by school governors, provides a solid point of defense, and gives an official backing to any stance on selection.

Issues with interference are less easily solvable. A couple of librarians reported books being stolen from their libraries, or defaced. One pointed out that this “may mean that a student who does not want to openly borrow these books has found them useful, but it would be useful to be able to quantify this.” When viewed from this perspective, books disappearing may not be a wholly negative thing; however it does impact on budget, especially if titles need repeated replacement. None of the respondents had found a solution to this issue.

Budget and time

The third barrier facing librarians is constraint of time and budget, which only exacerbates the above problems. When books are difficult to find, librarians may not have time to hunt them down, and if books are defaced or stolen, money that could have been spent expanding the collection is spent replacing them. Some librarians also mentioned that lack of time to read books in their entirety led to incorrect categorization and complaints, and others simply wished they had more time to run events promoting the books.

These constraints aren’t specific to diverse books, but since these books are already underrepresented, and need more work and support, the constraints have a proportionally greater adverse effect. With other books and resources to devote time and money to, there’s a delicate balancing act between the many worthwhile things going on within library walls.

Solutions?

It’s difficult to know where to start tackling these various problems. There are websites and bits of advice scattered across the internet, and plenty of organisations run schemes and campaigns to get more diverse books into libraries, but that can only help so much.

The only thing that’s clear is that having diverse books in libraries helps to expand horizons, educate people, and promote more positive perceptions of diverse groups. CILIP (the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals) says: “Librarians have one of the best possible tools to educate and inform young people: books! But unless diverse books are published, purchased by library services and promoted to young people, this is not going to happen.”

This statement applies not just to young people, but to everyone. Books don’t exist in a vacuum; they have an impact on the world around them; they shape lives. The question is, how can the expanding sphere of diverse literature be brought into libraries, and how can it be ensured that everyone knows they’re there? How can they be effectively supported, promoted, and championed on a budget and under time-pressure? I don’t know the answer, I’m not sure anyone does. I think it’s something for everyone—publishers, librarians, and readers—to work out together.

Featured image Credit: “Library” by Stewart Butterfield. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Diverse books in school libraries appeared first on OUPblog.

Arguments about (paradoxical) arguments

As regular readers know, I understand paradoxes to be a particular type of argument. In particular, a paradox is an argument:

That begins with apparently true premises

That proceeds via apparently truth-preserving reasoning

That arrives at an apparently false (or otherwise unacceptable) conclusion.

[An argument is truth-preserving if and only if there is no way for the premises to be true and the conclusion to be false.]

Solving a paradox, then, proceeds either by arguing that one of these three appearances is illusory (i.e. a premise is not true, the reasoning is not truth-preserving, or the conclusion is not false), or by arguing that some concept involved in the argument is faulty.

There is another way that logicians sometime define paradoxes. On this alternative understanding, a paradox an argument:

That begins with true premises

That proceeds via truth-preserving reasoning

That arrives at a false conclusion.

This kind of definition, which I shall call the alternative definition, will likely be especially attractive to dialetheists – those philosophers who believe that at least some sentences, including those central to many familiar paradoxes, are both true and false (and hence, as a corollary, they believe that some contradictions are true). The reason is simple: on this definition we can prove very easily that the conclusion to any paradoxical argument is both true and false.

Given the first two clauses in the second definition of paradoxes given above, it follows that the conclusion of every paradoxical argument is true: After all, any paradoxical argument begins with true premises, and proceeds via truth-preserving reasoning. Hence, the conclusion must be true. But the definition also entails, via the third clause, that the conclusion of any paradoxical argument is false. Hence, either no paradoxes exist, or the conclusion to any paradoxical argument is both true and false.

For present purposes, we can assume that paradoxes do, in fact, exist (after all, I have been writing this column on paradoxes since late 2014, and it would seem like a silly waste of time if I was writing about something that doesn’t exist). Hence, on the alternative understanding of what it is to be a paradox, dialetheism must be correct.

Now, the non-dialetheists in the room (or staring at the screen) might just take this to be an argument that the first definition – the one involving three occurrences of the word “apparently” – is a better definition of the phenomenon in question. And I wholeheartedly agree with this assessment. But that doesn’t mean that it isn’t worth exploring the alternative definition a bit more to see what additional puzzles we can concoct.

It’s worth noting that what follows is carried out informally – as a result, and as is to be expected, many of the inferential moves made will be rejected on various non-classical solutions to the semantic paradoxes (especially dialethic solutions!)

One question we might ask is whether we can construct paradoxical arguments in terms of this alternative understanding of the term “paradox”. Similar questions have been raised by logicians since at least the Middle Ages. One well-known example, called the pseudo-Scotus paradox, proceeds via reasoning about whether the very argument in question is truth-preserving:

Premise: This argument is truth-preserving.

Conclusion: Santa Claus exists.

Assume, for reductio, that this argument is not truth-preserving. Then there must be some way for the premise to be true and the conclusion to be false. But if the premise is true, then given what it says (i.e. that the argument is truth-preserving), the conclusion must also be true as well. So there is no way for the premise to be true and the conclusion to be false. Contradiction. Hence, the argument is, in fact, truth-preserving. But that is just what the premise says. So the argument has a true premise and is truth-preserving. Hence, the conclusion must be true as well.

Of course, this is an absurd way to prove that Santa Clause exists, and the argument will likely feel familiar to many readers, since it is a version of the Curry paradox carried out at the level of arguments (this general pattern is called the V-Curry in the technical literature).

Of course, once we have seen the general idea, we can construct all sorts of variants. Of particular interest are variants that involve our alternative notion of paradoxicality. For example, consider:

Premise: This argument is truth-preserving but not paradoxical.

Conclusion: This argument is paradoxical.

We can easily show that this argument must be paradoxical: Assume, again for reductio, that the argument is not truth-preserving. Then there must be some way for the premise to be true and the conclusion to be false. Thus, it is possible that the argument is truth-preserving (since this is required by the truth of the premise) and not paradoxical (since this is required by both the truth of the premise and by the falsity of the conclusion). But in such a scenario, the premise would also be true (since it just says it is truth-preserving and not paradoxical). Hence, since in this scenario we have a true premise in a truth-preserving argument, the conclusion must also be true. Contradiction. Thus, the argument is truth-preserving. Now, assume (again, for reduction) that the argument is not paradoxical. But then the premise would be true. Hence, since we have already shown the argument to be truth-preserving, the conclusion must be true as well. Contradiction. So the argument is paradoxical.

This argument is already troubling enough: We have shown that an argument that (i) begins with a premise claiming that the very argument in question is in the best logical standing (truth-preserving but not paradoxical) and (ii) ends with a conclusion claiming that the argument in question is in very bad standing (paradoxical), is not invalid or unsound as we might expect, but is instead paradoxical.

But things seem even more puzzling. According to the alternative definition of paradox, a paradox is supposed to have true premises, be truth-preserving, and have a false conclusion. But the reasoning above shows that the argument in question has a false premise (since the argument is, in fact, paradoxical) and a true conclusion! Clearly, something has gone dreadfully wrong!

[Josh Parsons pointed out the alternative definition of paradoxes, which led me to thinking about the issues raised in this post.]

Featured image: Kandinsky, Jaune Rouge Bleu. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Arguments about (paradoxical) arguments appeared first on OUPblog.

March 31, 2017

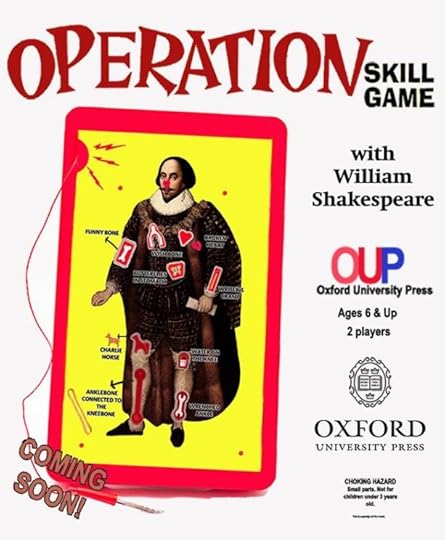

The OUPblog team have created literary board-games

Every year, on 1 April, the OUPblog team rack their brains for inspiration. We try to figure out if there is something else we should be doing, other than providing academic insights for the thinking world and daily commentary on nearly every subject under the sun. One sunny afternoon, while staring into the eyes of William Shakespeare, it came to us. We should be creating new board-games based on famed literary figures.

A few cups of coffee later and we had brainstormed several ideas for board-games that we hoped would appeal to our subscribers. First, we thought about rehashing Hungry Hungry Hippos and making an Oliver Twist version of the game. But the prototype we built proved to be too messy, with gruel a poor substitute for plastic marbles. Next we experimented on a new Monopoly board, turning the stops into the different locations in Wonderland. However, we kept falling down the rabbit hole, unable to go pass “Go”, and unable to collect $200.

Then we cracked it. Inspired by the 400th anniversary celebrations last year, we decided to create a new version of Operation based entirely on the playwright William Shakespeare. Critics have dissected Shakespeare’s texts for centuries; now they have the opportunity to dissect the man himself. Just don’t butcher the Bard!

Another idea we had was for an Oxford World’s Classics adaptation of the board-game Guess Who?. Does the literary figure you’re trying to track down wear a Western hat, a bonnet, or a deerstalker? Find out by playing the game. We’ve included some of the most famous figures from classic literature, from Anna Karenina to Othello, so you’ll have to channel your inner Sherlock Holmes in order to guess which card we’ve selected…

What do you think? Which board-game would you want to play the most? Let us know in the comments section below or via Twitter, Facebook, or Tumblr.

Image credits: All images produced by Nicole Piendel for Oxford University Press and in the spirit of April Fools’ Day. Do not re-use without permission.

The post The OUPblog team have created literary board-games appeared first on OUPblog.

César Chávez would oppose Trump’s border policies

Donald Trump ran for the US presidency on the backs of undocumented immigrants, particularly those from Mexico, calling them criminals and promising to build a border wall across the entire length of the United States-Mexico border to keep them out. As Trump issues executive orders and unveils his Congressional proposals for immigration enforcement as an integral part of his initial “100-day action plan,” that timeline intersects with what would have been the 90th birthday of labor rights champion César Chávez on 31 March 2017. As have some staunch opponents of undocumented immigration, such as Lou Dobbs, I anticipate in the coming policy battles that Trump might draw on Chávez’s legacy to support his restrictive proposals to deny immigrant entry. Dobbs, for example, contended that Chávez objected to “illegal immigration with all of his heart and all of his energy.” These immigration opponents might point to Chávez’s union members having patrolled the border at times in the late 1960s and early 1970s during borderlands labor strikes to confront undocumented Mexican workers crossing to serve complicit US employers as strikebreakers. Might the Chávez UFW union legacy be appropriated to argue that Mexican workers must be stopped by any means from crossing the border to come here and “steal” jobs?

Such a revisionist history would misconstrue what was a far more complicated and evolving posture of César Chávez on the subject of Mexican undocumented immigration. The UFW union members who confronted and discouraged entering strikebreakers in the borderlands did so against the backdrop of a far less policed border that predated the obsessive securitization that President Bill Clinton oversaw and others continued. Strikebreakers could once readily cross the border on roads that connected Mexico and the United States in populated areas to replace the striking union workers in nearby fields. Crossing the border then was not a deadly gauntlet of entry that Trump proposes to make even more treacherous with longer and higher walls and more border officers.

César Chávez speaking at a United Farm Workers rally in Delano, CA, in 1972 by Joel Levine. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

César Chávez speaking at a United Farm Workers rally in Delano, CA, in 1972 by Joel Levine. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Moreover, as UFW co-founder Dolores Huerta explained to me in 2007, “The whole thing is we wanted people not to break the strike, period. We’re not against people who are undocumented. We just don’t want them to break our strike.” Chávez recognized the hypocrisy of INS immigration officials, who would look the other way to protect farmers when they employed undocumented workers as labor strikebreakers, but would deport the workers once the crops were picked or if they joined the UFW strike. Chávez alleged the Nixon administration and the growers conspired to limit immigration enforcement in the fields, so long as the migrants were useful to the growers, in the ongoing cycle of the invitation and exile of Mexican workers seen by too many US employers as implements rather than as humans.

Chávez recognized the precarity of the undocumented worker as exactly suiting the needs of employers hoping to suppress unionization in their workforce. An undocumented worker, actively recruited as a strikebreaker, would be unlikely to defect to the union side or complain about workplace injustices, and if the worker did, the employer could count on immigration officials to oust the worker at its urging. Chávez and the UFW accordingly championed amnesty for undocumented workers, as well as easing restrictive immigration limits and hurdles for those future entrants seeking status as lawful permanent residents or ultimately as US citizens. In contrast, Trump has called for the ouster of the current undocumented population and cranked up internal immigration raids, while not suggesting any expansion of lawful migration. Rather, he appears to support a downsizing of lawful immigration limits, particularly for refugees and those who come with little education or economic status. Nor is Trump any friend of unions or labor.

On the subject of mass deportation, Chávez wrote in a 1974 editorial of the San Francisco Examiner that the UFW opposed the mass deportation of undocumented immigrants, most of them from Mexico. Rather, Chávez advocated amnesty and supported immigrant efforts to obtain lawful status and equal rights, including the right to unionize. While resisting their use as strikebreakers—who the union opposed regardless of their migration or citizenship status, Chávez urged federal immigration reform to allow current undocumented migrants to gain protection as legal residents in their employment and everyday lives.

As immigrant advocates prepare for the tempest ahead under Trump, we should celebrate the vision of César Chávez, who fought for the dignity of all workers, rather than warp his legacy to turn it against the most vulnerable of laborers—undocumented immigrants. With the volume of hostility toward immigrants, particularly those from Mexico, increasing after Chávez’s death, we have devolved from a “nation of immigrants” to one that betrays the ideal of equality of opportunity for migrants to seek lawful status in their road away from precarity and toward dignity and the American Dream. Richard Chávez, César’s brother, once told me that César, if still alive, would be “right in the middle of it” today fighting for the rights of undocumented immigrants. We should fight that battle for him.

Feliz cumpleaños, César, on the occasion of your 90th.

Featured image credit: “A Wall with a Mission” mural of César Chávez in San Fernando, CA. Chris English. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post César Chávez would oppose Trump’s border policies appeared first on OUPblog.

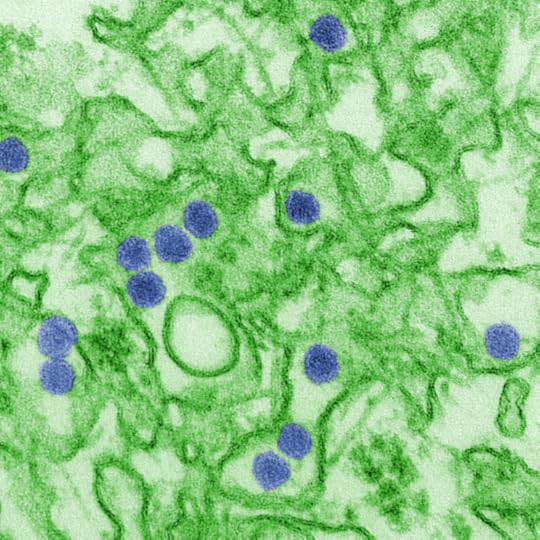

Bugs don’t recognize nationality

Science matters. In a moment in which facts can apparently have factual and alternative flavors, it feels important to state that unequivocally. We recognize that in an era of growing insularity and retrenchment, it may seem strange to argue for more global health investments and cooperation. But, we hope that, regardless of individual or even national views on the larger debate of insularity or openness, consensus exists – or at least could emerge – that cooperation is necessary in global health. Microbes have not yet met an ocean, wall, or national border they could not permeate. Zika once again has demonstrated that large and small countries, relatively wealthy and relatively poorer countries all are dependent on a larger infrastructure for their national health security – even the United States cannot rely solely on itself to fight an outbreak or protect itself and Americans from the next outbreak.

While Zika is off the front pages now, it continues to pose a serious threat to communities across our hemisphere. It was not eradicated from any country where it appeared – including the United States – and Zika has now expanded its geography to include additional countries in the Pacific and Southeast Asia. Between November and January alone, the US Centers for Disease Control counted close to 4,000 new cases in the United States alone (Puerto Rico, the US Virgin Islands, American Samoa, and the continental US plus Hawaii).

Huge research gaps continue to persist around Zika, ones that would be best addressed through cooperation rather than competition. We need to know more quickly the number of cases emerging across the world, where such cases are developing, which vectors can carry the virus, what epidemiological evidence exists along routes of transmission (mosquitos, sex, saliva?), how likely an outbreak is to spread based on the above, what risks the virus poses to pregnant women and their babies (the relative risks of microcephaly and other neurological and non-neurological developmental disorders by trimester), and whether co-infections such as with dengue affect risk. The good news is that more of this incomplete list is happening than was true even a couple of months ago – and there are now close to a dozen Zika vaccine trials underway and at least one is moving into early phase human studies.

This is a digitally-colorized transmission electron micrograph (TEM) of Zika virus, which is a member of the family Flaviviridae. Photo by CDC/ Cynthia Goldsmith. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

This is a digitally-colorized transmission electron micrograph (TEM) of Zika virus, which is a member of the family Flaviviridae. Photo by CDC/ Cynthia Goldsmith. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.To do the activities above requires money, including continuing the vaccine trials. The world stands at a crucial point in terms of Zika funding. As Zika continues to spread while funding fails to be delivered, we worry it is both a warning sign and a proof point of the world entering a period of ‘disease appeasement’ – a reality where outbreaks, lives affected, and babies lost are the new normal. What is most surprising is that the United States. is failing to generate domestic funding to manage an outbreak, which contrasts with the role that it has played over the past two decades as a major leader in global initiatives to tackle HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, and vaccine-preventable diseases. The frustrations of short-term domestic politics points to the crucial role international agencies and a larger health security infrastructure can play in ensuring health challenges are confronted with sustained long-term vision.

At the global level, the World Health Organization is the key agency to lead on this with a constitutional mandate from its 194 member states to address health emergencies. But given its fumbling of Ebola in which the agency was harshly criticized for its slow initial response, little trust exists to fund and ultimately empower the WHO. We share this frustration but after much deliberation our only hope is to use the dreaded R word and for member states to push through key reforms of the agency to be able to do this important work. Only through successfully managing such crises will the WHO be able to reestablish its credibility.

The upcoming Director-General election in May 2017 provides an opportunity for governments across the world to support a strong leader with a clear vision for the agency’s future. We tend to forget that across centuries, controlling infectious diseases has continued to bring countries together. Ultimately outbreaks are about humans – regardless of nationality, religion, or skin colour – versus microbes, and the only way to defeat them is to work together.

A version of this post was originally published on the Global Health Governance Programme blog.

Featured image credit: This female mosquito (Aedes aegypti) is just starting to feed on a person’s arm on May 23, 2012. USDA photo by Stephen Ausmus. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Bugs don’t recognize nationality appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers