Oxford University Press's Blog, page 385

March 31, 2017

Where we rise: LGBT oral history in the Midwest and beyond

In early March, ABC released a much-anticipated mini-series that followed a group of activists who played important roles in the emergence of LGBTQ political movements. The show, When We Rise, was based in large part on a memoir by veteran activist Cleve Jones. While the series tells a compelling story, it is necessarily limited by its 8 hour runtime, focusing predominantly on the work of people in and around the San Francisco Bay Area. Yet, as we have noted on the blog before, queer history happens everywhere, and oral historians are working to make this history visible. Today we continue our series on oral history and social change by highlighting the diversity of queer life and activism, exploring oral history projects from around the U.S.

The Midwest may not have had moments that grabbed national headlines like Stonewall or the rise of Harvey Milk, but it is home to pioneering moments of activism and community building. When Kathy Kozachenko was elected to Ann Arbor’s city council in 1974, she became the first out LGBTQ person elected to public office in the United States. The Bentley Historical Library at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor holds oral histories and archival collections of local queer life throughout the 20th century, as well as the records of the Human Rights Party, the organization that sponsored Kozachenko’s historic candidacy.

In Madison, Judy Greenspan ran for school board in 1973, the same year as Harvey Milk first began his political career. Neither Greenspan nor Milk won their campaign, but both would help to shape the progression of LGBTQ politics. The University of Wisconsin-Madison holds interviews with and ephemera from Greenspan, as well as an archival collection that spans nearly a century of queer life. The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee’s Transgender Oral History Project and the Milwaukee LGBT History Project document even more of Wisconsin’s LGBTQ past.

The Twin Cities GLBT Oral History Project, at the University of Minnesota, used its recordings to produce a book that explores a wide variety of queer histories. The book calls into question many assumptions about the story of LGBTQ activism as it has been told on the coasts, asking what this history looks like when it adopts an alternative geographic focus. Last year we spoke with Jason Ruiz, one of the project’s collaborators, about both the project and an article he had co-written for the OHR which asked what makes queer oral history different.

Chicago has its own unique queer history, and the Closeted/Out in the Quadrangles project holds more than 90 interviews on LGBTQ life at the University of Chicago. Both the Leather Archives & Museum and Chicago Gay History provide additional oral histories, along with videos, that document the lives of a wide variety of LGBTQ Chicagoans.

Outside of these northern cities, universities and community groups have mapped out an even more complicated landscape of queer life. The Ozarks Lesbian and Gay Archives at Missouri State contains both oral histories and archival collections. The Queer Appalachia Oral History Project at the University of Kentucky, the University of Kansas’ Under the Rainbow: Oral Histories of Gay, Lesbian, Transgender, Intersex and Queer People in Kansas, and the Queer Oral History Project at the University of Illinois all provide invaluable oral history collections that depict the lives and struggles of queer people around the South and Midwest. The Brooks Fund History Project, at the Nashville Public Library, focuses on Middle Tennessee, exploring the contours of queer life before the Stonewall Riots of 1969. The geographically disparate Country Queers project includes stories from rural communities across the country, from the deep south to the mountain west.

AIDS activism dominates one entire episode of ABC’s miniseries, and is a major focus of many LGBTQ oral history projects. The New York City focused ACT UP Oral History Project provides a rich history of an organization that has been at the forefront of HIV/AIDS activism, and its recordings were the basis for the 2012 documentary, United in Anger. Both the National Institutes of Health and the University of California San Francisco have documented the experiences of medical professionals who played key roles, especially in the beginning of the epidemic. The oH Project: Oral Histories of HIV/AIDS in Houston, Harris County, and Southeast Texas has a growing collection of recordings about the local response to AIDS and the experiences of Texans. The African American AIDS History Project includes an oral history project on AIDS activism, as well as a sprawling collection of materials about AIDS in African American communities.

Moving outside the U.S., the LGBT Oral History Digital Collaboratory, located at the University of Toronto, is working to create a hub for queer oral history collections across the world, providing researchers and community members easy access to a wealth of information. In 2015 we spoke to Elspeth Brown from the Collaboratory, on the importance of working together in preserving queer history.

This short list is by no means a comprehensive overview of LGBTQ oral history projects, but it provides a taste of the diversity of stories that define this history. Queer history continues to happen everywhere, and the growing number of projects that document and preserve this history will enable the creation of new, more complex version of the vast queer past.

Chime into the discussion in the comments below or on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, or Google+.

People from Madison, WI at the 1979 March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights. Image courtesy of the UW-Madison Archives.

The post Where we rise: LGBT oral history in the Midwest and beyond appeared first on OUPblog.

Getting to know James Grainger

The eighteenth-century Scottish poet James Grainger has enjoyed a resurgence of scholarly attention during the last two decades. He was a fascinatingly globalized, well-rounded, idiosyncratic author: an Edinburgh-trained physician; regular writer for the Monthly Review; the first English translator of the Roman poet Tibullus; author of both a pioneering neoclassical poem on Caribbean agriculture, The Sugar-Cane (1764), and the first English treatise on West-Indian disease; and the friend and correspondent of a number of well-remembered literati and arbiters of culture in his day, including Samuel Johnson, James Boswell, Joshua Reynolds, and Thomas Percy. Although he got his literary start in London, Grainger married into a prominent planter family while on a long trip to the West Indies. He eventually settled in St. Kitts, where he practiced as a physician on sugar plantations, wrote and studied during his free moments, and died before his time (at around age 44, his biographer estimates). This makes Grainger a compellingly transatlantic, well-connected, somewhat mysterious figure. His major works, The Sugar-Cane in particular, addressed the enormous territorial expansion of the British Empire at the end of the Seven Years’ War, and his vexing presentation of West-Indian slavery in The Sugar-Cane first appeared in print about a decade before formal agitations began against the slave trade in England.

In recognition of this topicality, The Sugar-Cane saw its first modern edition in 1999: Thomas Krise’s Caribbeana: An Anthology of English Literature of the West Indies, 1657-1777. The following year, John Gilmore’s indispensable critical edition of The Sugar-Cane laid the groundwork for future generations of scholarship, with its ample editorial notes and an authorial biography that gathers together virtually all of what is now known about Grainger’s life and lifework. Since then, there has been a steady stream of new scholarly articles and book chapters dedicated to Grainger—largely on The Sugar-Cane, his major work—and he is swiftly becoming a fixture in college literature courses on the rise of empire in the eighteenth century and the problem of slavery at the center of British and American national identity.

This meteoric rise into critical consciousness represents a real paradigm shift. For much of the last century, most eighteenth-century specialists treated Grainger as a writer who was not worth knowing. The Sugar-Cane’s highly ornamented style was at odds with sleek, modernist ideals for poetry; its uncomfortable subject matter further compromised its appeal for those audiences. Wyndham Lewis and Charles Lee included excerpts of The Sugar-Cane in The Stuffed Owl: An Anthology of Bad Verse (1930). Critics spoke of Grainger as a rightfully “Neglected Poet” and derided him for “verbal felicity married to mental imbecility” and his insistence on applying Virgilian poetic ornaments to an unruly tropical setting: “[W]hile the Mantuan reaps corn Grainger hoes yams, while the Mantuan treads grapes Grainger must peel bananas,” snarled Ronald Knox in 1958, wondering disparagingly at Grainger’s reliance on “local colour,” and the fact that “the human labour involved [in sugarcane cultivation] is not that of jolly Apulian swains but that of negroes looted from the Gold Coast, whose presence has begun to need some explanation, even to the easy conscience of the eighteenth century” (Knox). In short, scholars in the age of high modernism barely read the poem (in which peeled bananas do not, in fact, appear). Only in the 1970s did a smattering of more earnest (often brief) scholarly comments on Grainger begin to appear in print. As a result, the gradual process of accumulated knowledge and familiarity that characterized the reverential reception of other famous eighteenth-century writers—the tracing of allusions, the description of textual patterns, the hashing out of critical debates—did not really happen in Grainger’s case, despite his continuing, shadowy presence as an exemplar of bad taste.

In other words, there may still be much that we don’t know about Grainger. I was struck by this during the course of my own research on The Sugar-Cane when I traveled to the library of Trinity College Dublin to track down an important “known unknown” in the poem’s textual history: a series of aborted political references, mentioned briefly in the notes to Gilmore’s edition, but whose significance had yet to be analyzed. I had at the time been studying The Sugar-Cane for years, and my week in Dublin did indeed give me a number of leads, particularly as related to Grainger’s appraisal of the posture of the West India Interest during the Seven Years’ War. The experience of handling the physical object of the manuscript also predictably provoked a number of mundane, material questions about Grainger’s life and social networks, from wondering about his personal acquaintance with local planters such as Lord Romney and Samuel Martin (whose portrayal Grainger altered during the course of composition) to probing the manuscript’s provenance. (Was this the manuscript that made its way to England for that legendary reading of a draft of the poem at the house of Joshua Reynolds? It’s unclear.)

In other words, there may still be much that we don’t know about Grainger.

Yet, even as I began to follow up on these sometimes-inconclusive speculations, I was unprepared for a plain revelation that came to me surprisingly late, some months after returning home from Dublin. One day, it finally occurred to me that the “Mr Smith” that I had seen scrawled on the back of a page of The Sugar-Cane’s manuscript was a reference to the “Mr Smith”—Adam Smith, the Scottish Enlightenment moral philosopher and economist. A simple Google search of “Smith” and “sordid master” (a distinctive phrase in the note) had identified The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) as the text in question; a query to my favorite eighteenth-century listserv corroborated the identification. In the nearly page-long comment, which appears near a draft of the versified portrait of “the good Montano,” Grainger challenges Smith’s categorical condemnation of slave owners as “sordid masters,” incapable of full moral feeling. He describes his portraits of Montano and Christopher Columbus as “characters” who will “vindicate” the planter against Smith’s deprecation. As I began to sharpen my transcription and explore the allusion further, I was unprepared for the way this manuscript evidence would gradually alter my own understanding of Grainger’s intellectual ambition, composition process, and coherence as a writer.

The most surprising thing about this finding may have been the way it helped me to recognize Grainger as an intensely bookish creature, bent on grappling with the cutting-edge moral philosophy of his day, even in the harsh environment of the colonial tropics. It was stunning to reflect that, in 1759 or soon thereafter, while Grainger was traveling to or perhaps already living in the West Indies, he went out of his way to obtain Smith’s moral philosophical treatise, then hot off the press. He must also have actively sought out a 1760 philosophical work by George Wallace, A System of the Principles of the Laws of Scotland, for he meditates at length on its radical anti-slavery chapter elsewhere in the manuscript (a comment cited and partially quoted in Gilmore’s edition). Both treatises develop serious philosophical appraisals of the harmfulness of slavery as an institution and its ill effects on masters and slaves alike. This was Grainger’s leisure reading, while newly married into the plantocracy and in the process of establishing his business as a plantation physician? What prior intellectual investments and personal connections led him to seek out this high level of self-critique? Did he and Smith cross paths while Grainger was pursuing his medical degree at the University of Edinburgh? What prior relationship did Grainger have with the great Scottish Enlightenment patron Lord Kames, whom Grainger presented with a copy ofThe Sugar-Cane?

In the last century, readers were often disinclined to think of Grainger as athinker—as a philosophical or systematic writer deliberately engaged with the hard ethical questions of his day. In the “stuffed owl” era, Grainger appeared as an overzealous classicizer, mechanically imitating Virgil in his Carribeanization of the georgic to the detriment of true poetry and good sense. Recent scholarship, in a variation on this view, has often seen in Grainger a clumsy, somewhat passive mouthpiece of planter interests and self-contradictory imperial ideologies that he didn’t fully understand. But Grainger’s manuscript points us toward a different way of knowing Grainger: unearthing the Enlightenment anti-slavery discourse that motivated his study. In the writing of The Sugar-Cane Grainger understood himself to be borrowing and extending Enlightenment methods for discerning cultural patterns and analyzing their relationship to the development of moral sentiment. The cramped, nearly page-long comment on Smith that survives in The Sugar-Cane’s manuscript spells out the logic behind these arguments.

The smallest details of Grainger’s verse portraits in The Sugar-Cane make sense in light of these philosophical concerns; and even Grainger’s patterns of editing in the manuscript can be explained as applications of Enlightenment ideals of “impartiality” in the handling of divisive topics. We have not been inclined to see The Sugar-Cane as a vehicle for philosophical discussion and debate in this way, but this is where the most recent evidentiary revelations lead us.

Featured image credit: The New and Universal System of Geography by G H Millar. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Getting to know James Grainger appeared first on OUPblog.

Global future challenges, twists, and surprises

From time immemorial, humans have yearned to know what lies ahead.

Setting the context is a three thousand year romp through the ‘history of the future’ illustrating how our forebears tried to influence, foretell, or predict it. Examples extend from the prophets and sibyls, to Plato and Cicero, from the Renaissance to the European Enlightenment. By the Second World War scientific attempts to predict the future were being developed by the US military-industrial complex. By the mid-20th century, future methods were mostly concerned with State planning and war scenarios in the USA, the USSR, and Germany, extending into the Cold War period.

However, the traditional belief in a single predetermined, and thus predictable, future was challenged in the 20th century, first by quantum physicists, then by systems scientists and sociologists. A new breed of humanistic futurists began from the 1960s to apply future-thinking to all manner of human challenges, raising this key question: “What if there is not one future to colonize, predict, and control, but many possible alternative futures that we can imagine, design, and co-create?”

Anyone who thinks deeply and looks beyond their own personal interests will see a large number of global challenges, as volatile, unpredictable futures rush towards us. The twelve clusters of issues span three interdisciplinary domains: environmental, geo-political, and socio-cultural. A mind-map includes current trends likely to create major problems for the futures of humanity. A second mind-map details numerous alternative futures we can create. These counter-trends, twists, and surprises offer enormous potential to mitigate, disrupt, or reverse the dominant trends. They enable readers to imagine and create alternatives to the disturbing trends being forecast and broadcast.

For brevity this piece prioritises the environmental domain, as it is fundamental to human existence on this planet. We have known for decades that the entire ecosystem of the earth is under severe strain. Our ecosystem, energy systems, and climate crisis are clearly interconnected. Health is integral because healthy human futures are so reliant on how we deal with the future of our earth, its atmosphere, biosphere, climate, plants, oceans, and other sentient beings.

Although there are widespread concerns about food and water security for an expected global population of 9 billion by 2040, there are some weak signals that citizens want to take back control over their food and water security. Cities seeking to creative sustainable solutions are experimenting successfully with vertical gardens, bush food forests, and urban farms, as part of the post-industrial, creative, and eco-city movements designed to deal with food security.

Disturbing energy trends include peak oil and the crisis of fossil fuels, nuclear waste disposal, and overall resource depletion. Some welcome counter-trends include the divestment in carbon fuels and upsurge in renewable energy, the growing awareness of the global need to reuse, recycle, and up-cycle, particularly among young people.

In the health domain, new and resistant diseases are emerging, some threatening to reach pandemic proportions. The World Bank and WHO claim there is a global epidemic of depression. Mental health problems such as anxiety and suicide are increasing, especially among youth. Counterpoints to these alarming trends include a renewed focus on healthy communities, futures visioning work with young people, alternative and traditional medicines to complement antibiotics, better sanitation in countries most in need, and, last but not least, global educational transformation.

There are three grand global challenges: growing urbanization, lack of (or inadequate) education, and the climate crisis. Although these challenges may seem insurmountable, we have the power to deal with them constructively if we choose to meet them with clarity, imagination, and courage. However, if we choose to keep our heads in the sand, we have chosen not to care about our common human futures. We do so at our peril.

Featured image credit: Fractal grid design by PeteLinforth. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Global future challenges, twists, and surprises appeared first on OUPblog.

March 30, 2017

Self-portraits of the playwright as an aging man [part three]

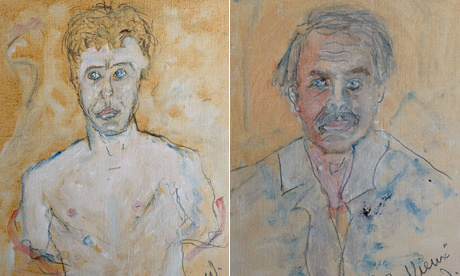

In the late 1970s, Tennessee Williams frequently visited London, feeling that European stages were more catholic than New York’s and thus open to producing his plays at a time when America was growing less tolerant of his brand of theatre. While in London, Williams would often visit celebrity painter Michael Garady and swap writing for painting lessons. In an interview with The Guardian, Garady recounts those days when Williams painted his portrait (below left) and another self-portrait (below right), which Williams entitled Le Vieux TW (Williams nearly always gave his paintings French titles, perhaps to lend them gravitas). The wild, drugged-out look of 1972 is now gone, but wrinkles clearly mark the brow, and he appears to have one eye looking straight at the viewer and one slightly askance. Although this was an accurate portrayal of his wonky eyes—Williams suffered from chronic eye-problems, the crooked gaze he captures here no doubt served another purpose.

Metaphorically speaking, the bifurcated gaze in this last self-portrait perfectly captures Williams’s sense of his divided self as he approached the eighties. He was equally nostalgic for the salad days that allowed him to write and experiment freely with art forms and hungry for the Cinderella comeback that would silence the naysayers and reaffirm his status as America’s greatest living playwright. It is only fitting, then, that Williams revisited an older one-act play of his, The Parade, to fuse past and present. He had begun writing the play as early as 1940, during his first visit to Provincetown, where he would befriend Hans Hoffmann. Hoffman’s abstract expressionism would greatly influence Williams’s theory of the plastic theatre. The Parade eventually became the full-length play Something Cloudy, Something Clear, a title that could be readily affixed to any of his self-portraits. Figuratively and literally recalling the way he saw the world, Something Cloudy, Something Clear also represents the “two sides of my nature,” as he confided to Dotson Rader in 1981: “The side that was obsessively homosexual, compulsively interested in sexuality. And the side that in those days was gentle and understanding and contemplative.” Selfies rarely, if ever, capture anything more than a one-dimensional figure in two-dimensional space.

Le Vieux TW (Tennessee Williams, self-portrait), n.d. (ca. 1978/1979). Courtesy of Michael Garady. Used with permission.

Le Vieux TW (Tennessee Williams, self-portrait), n.d. (ca. 1978/1979). Courtesy of Michael Garady. Used with permission.Their artistic merits notwithstanding, all of Williams’s several self-portraits discussed in these three blogs evince a playwright who took his painting seriously. Never formally trained, and certainly more dabbler than master, Williams nonetheless called many of the world’s most celebrated artists his friends, and each imparted his or her wisdom or knowledge to the eager student: Adelaide Parrott, a WPA art instructor who gave Williams informal lessons during his California road-trip in 1939; New Orleans painters Fritz Bultman and Olive Leonhardt, who would be immortalized as Moise in Williams’s 1975 novel, Moise and the World of Reason; sculptor Tony Smith, who had studied with Bultman at the New Bauhaus in Chicago; abstract expressionist Jackson Pollock, whose death inspired Williams’s play In the Bar of the Tokyo Hotel (1969); southern painter Henry Faulkner, who often painted with Williams in Key West or in Italy; Australian artist Michael Garady, who tutored Williams in the late seventies whenever he was in London; and Vassilis Voglis, a Greek painter who remained one of Williams’s closest friends at the end of his life. Simply put, Williams’s rolodex held as many painters’ names as it did theatre directors’ or Broadway producers’; so it should come as no surprise that his paintings meant a lot to him and to his creative oeuvre.

When asked once if he had kept souvenirs from his past, Williams quipped about having collected memories, not mementoes, throughout his life. Arguably, self-portraits are Williams’s memories, subjective representations of a moment frozen in time yet unfettered by historicity and susceptible to change over the years; whereas selfies are his mementos, objectified reproductions of a frozen moment in time duly framed by its history and tethered to a unique recollection. A self-portrait aspires and inspires; a selfie captures and recalls. Williams, I believe, preferred the self-portrait, be it in image or in words, because it spoke about the individual but to the universal. One question, though, still begs: were he alive today and in possession of a smartphone, would Williams take a selfie? I have my serious doubts.

Featured image credit: Tennessee Williams star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame by E. Coman. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Self-portraits of the playwright as an aging man [part three] appeared first on OUPblog.

The unintended effect of calling out “fake news”

CNN’s Don Lemon recently pushed back when Paris Dennard, a conservative pundit, insisted on calling a story they were covering (the cost to the taxpayer of President Trump’s frequent visits to Florida) “fake news.” As Lemon said, “Fake news is when you put out a story to intentionally deceive someone and you know that it is wrong.” Lemon provided an excellent definition for fake news, but it’s also a great definition for “propaganda”.

Words matter, and those of us who care about our environment (and the people in it) need to choose our words carefully. Trump and his supporters are good at staying on-message and using specific phrases over and over again, familiarizing the public with their rhetoric; on the other hand, the loose confederation of environmental scholars, researchers, activists, and concerned citizens in the environmental community is not nearly as disciplined. I don’t think that’s a bad thing—we have a diverse set of backgrounds, concerns, and worldviews, and that diversity can be a real strength—but we need to carefully consider how we’re going to give voice to our concerns. Not calling it propaganda—but instead decrying “alternative facts,” or worse, pointing a finger back at them and saying that they’re the ones promoting fake news—won’t serve us nearly as well as stating plainly that the Trump administration is disseminating propaganda.

Simply re-framing the debate alone won’t solve everything, of course. But not doing so could cause more damage in the future. By saying that they don’t do fake news, Lemon runs the risk of reinforcing the idea that CNN and other reputable news outlets promote fake news. A researcher named Ian Skurnik and his associates explored this concept from a public health perspective by giving undergraduate students one of two flyers about the flu vaccination: one created by the CDC, and one created by the researchers. The CDC flyer listed three facts and three myths about the flu, while the new flyer listed only facts. For example, the CDC flyer listed the myth that the side effects of the vaccine are worse than the flu itself, labeled it as a myth, and then provided clarifying information about that statement. The new flyer was identical except that it contained only facts (so, “any side effects beat getting the flu”). After the students read the flyers, they were questioned about what they had read.

It turns out that a 30-minute delay was enough to get significant numbers of students who had read the CDC flyer to misremember the myths as facts. The authors concluded that “repeating misinformation in order to discredit it can enhance its perceived truth.” Other research demonstrated similar findings in older adults: if a claim was familiar to them, then re-stating the claim in order to discredit it only served to make it more likely that people would believe the claim to be true.

Testing suspected hazardous site for chemical and biological agents by USEPA, Eric Vance. Public domain via Flickr.

Testing suspected hazardous site for chemical and biological agents by USEPA, Eric Vance. Public domain via Flickr.All of this has direct implications for the environmental community. Let’s take the example of the EPA. Conservatives have consistently told us that regulation is bad for business. We haven’t made much progress arguing that regulations aren’t all bad for business, because we’re still parroting their words back to them: “regulation” and “business”. It’s no wonder that some people come away believing the initial claim, the one they’re most familiar with: i.e., regulation is bad for business, which is bad for me, and the EPA is all about regulation… therefore, the EPA is bad for me.

However, the agency is called the Environmental Protection Agency, not the Environmental Regulation Agency. And who disagrees with protections? We all want to protect our families, our communities, and ourselves from harm. This takes control of the rhetoric by stating that it’s important to protect people from environmental ills, and perhaps more importantly it breaks up the cycle of using the business vs. regulation rhetoric. The perspective we bring to a subject and the words we use—the framing of an issue—matters in all sorts of environmental contexts, including my own research in human-wildlife conflict. The side that effectively frames the issue in many ways has the upper hand.

To take a marine example, severe budget cuts have been proposed for NOAA, the US Federal Agency in charge of most of our climate and marine work. It’s housed in the Department of Commerce, which could give it a leg-up when it comes to arguing against steep budget cuts: its parent agency has “commerce” right there in the name. Setting aside the argument that climate research itself is vital for business, NOAA provides many services directly instrumental to the economy, from weather forecasting, to sustaining fisheries, to providing essential resources and services to coastal communities. By using the positive framing that NOAA is good for our economy—a strong NOAA is good for business—we steer the message away from regulations, climate change, and ocean conservation and directly towards some of the core concerns that prompted many to vote for Trump.

There are legitimate arguments that the intrinsic value of nature should also be stressed, and not just what nature can do for us, when it comes to convincing people that conservation is important. However, we are in triage-mode now, and there’s so much at stake. Changing people’s orientation to the environment is long and slow work (albeit vital in the long-run, and work we need to continue). Meeting people where they are now, and focusing on what’s important to them (protecting their families, making a living, increasing their quality of life) is a way of translating our own concerns about the world to their worldviews (and we, of course, share these concerns with them as well). So remember, it’s not fake news; rather, calling legitimate news stories fake news is propaganda (and so is spreading “alternative facts”). It’s not about loosening regulations so businesses can prosper; it’s about safeguarding our communities and economies.

Featured image credit: July 26, 2010 Stunning wetlands by USEPA Environmental-Protection-Agency. Public domain via Flickr.

The post The unintended effect of calling out “fake news” appeared first on OUPblog.

The United States of America: a land of speculation [excerpt]

Is speculation ingrained into American culture? Economists dating back to as early as John McVickar have analyzed the American enthusiasm directed toward speculation. History indicates that the American approach to enterprise has differed from its European counterparts since its inception.

In this shortened excerpt from Speculation: A History of the Fine Line between Gambling and Investing, author Stuart Banner discusses the economic risks taken in early American history, and the cultural significance of speculation in the United States today.

Foreign visitors to the United States often remarked on Americans’ passion for speculation. “An American merchant is an enthusiast who seems to delight in enterprise in proportion as it is connected with danger,” declared the German journalist Francis Grund. “He ventures his fortune with the same heroism with which the sailor risks his life; and is as ready to embark on a new speculation after the failure of a favorite project, as the mariner is to navigate a new ship, after his own has become a wreck.” In Chicago, the English writer Harriet Martineau reported that “the streets were crowded with land speculators, hurrying from one sale to another,” to the point where “it seemed as if some prevalent mania infected the whole people.” The French economist Michel Chevalier found the same atmosphere in Pennsylvania. “Every body is speculating, and every thing has become an object of speculation,” he observed. “The most daring enterprises find encouragement; all projects find subscribers.” For an American, insisted the English missionary Isaac Fidler, trading “upon speculation and credit” was simply “the custom of his country.”

“The primary commodity in which early Americans speculated was land.”

Were Americans more prone to speculation than Europeans? The economist John McVickar thought so. “We observe in our country,” he reasoned, “the greater frequency of individual failures and of general commercial revolutions, than is exhibited in most of the older countries of Europe, where something like the slow pulse of age seems to render comparatively innoxious those seeds of disease, which in our own warmer temperament, run out into unsound and feverish speculation.” The Bankers’ Magazine thought so too. “The English might teach us Americans a wholesome lesson,” it reflected. “It seldom happens that an English merchant, tradesman, or banker abandons his rightful trade or calling to engage in any thing like doubtful speculation.” A missionary journal agreed that “in no other country has this rage for speculation been more fully shown than in the United States.” But this was hardly a universal view. James Kent, one of the leading judges of the early republic, recalled that there was no shortage of speculation in Europe either. “The dreams and the madness of speculation,” he concluded, “is a disease which has prevailed on each side of the Atlantic.”

The primary commodity in which early Americans speculated was land. There was plenty of it; it came in all kinds, from small parcels of developed land in eastern cities to vast and scarcely populated western territories; and its prices fluctuated, sometimes quite sharply. As Charles Francis Adams complained, “the great object of domestic speculation in America is undoubtedly land.” When lots were sold in the new capital city of Washington, according to Justice Hugh Henry Brackenridge of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, most of the initial purchases “were on the speculation of an under sale to others, before the money was paid” by the ostensible buyer. Up in Maine, reported the promoter Moses Greenleaf, many of the landholders were nonresident speculators, who “purchased with a view of retaining the land for a time, in expectation of immense profits from the sale, when the country about them should become improved, and peopled by the exertions of others, without any trouble of their own.” Affluent and prominent Americans pooled their capital to form land companies, some of the largest business enterprises of the era, to buy enormous swaths of land in the West in the hope that future settlement would make the land more valuable. Land was simply a smart investment, advised the French lawyer J.P. Brissot de Warville, who took a close look at the land market while touring the new nation in 1788. Rather than putting money in a bank to provide for one’s children, Brissot suggested, “nothing appears to me better to answer this wise precaution, than to place such money on the cultivated soil of the United States.”

Contemporaries had little doubt that the United States was very different from Europe in this regard. “In Europe the value of real estate is in general comparatively stationary,” explained the chemist Robert Hare, “but here it is always an article of speculation; and as a large portion, while unproductive, is still held with a view to its future value, the estimate put upon that value is liable to great changes.” In Britain, noted Massachusetts Chief Justice Isaac Parker, no one owned sections of forest far away from their homes. “In this country, on the contrary,” he observed, “there are many large tracts of uncultivated territory owned by individuals who have no intention of reducing them to a state of improvement, but consider them rather as subjects of speculation and sale.” It was because of “the unrestrained spirit of speculation,” agreed William Tilghman, the chief justice of Pennsylvania’s Supreme Court, that “we see freehold estates pass in rapid circulation from owner to owner.”

Financial assets soon became a second big area of speculation, first with the issuance of state and national public debt securities to finance the American Revolution, then with the sale of US debt securities in the early 1790s, and finally with the steady expansion, all through the early republic, of the market for shares in banks and other business corporations. “Stockjobbing drowns every other subject,” James Madison complained in 1791, shortly after shares of the Bank of the United States were first sold to the public. In New York, he reported, “the Coffee House is in an eternal buzz with the gamblers.” Henry Lee traveled from Philadelphia to Alexandria, Virginia, around the same time and discovered that “my whole rout(e) presented to me one continued scene of stock gambling; agriculture commerce and even the fair sex relinquished, to make way for unremitted exertion in this favourite pursuit.” As shares of government debt and shares of business corporations became more widely traded, flurries of financial speculation would become regular features of American commercial life. By 1822, Chief Justice Tilghman could already deplore how quickly his fellow citizens threw their money into all these new corporations. “There has prevailed among us, to an unfortunate degree, a pestilent spirit of speculation, which has induced some, without means of payment, to subscribe to projects of all kinds, with a hope to selling out to advantage, as soon as the stock has risen,” Tilghman lamented. “These speculative subscriptions have many bad consequences.”

Featured image credit: Untitled by Unsplash. CCO via Pexels.

The post The United States of America: a land of speculation [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

In or out of Britain?: the big question for Scotland

The 2014 Independence referendum was an important moment in British constitutional history. With the Scottish Parliament’s decision to ask for a second vote, it also provides useful lessons for the future. The referendum of 2014 divided Scotland into two camps, a division that has now become the principal dividing line in the nation’s politics. Yet it has not created a social or ethnic divide such as we see in Northern Ireland. One reason for this is that the referendum did not hinge on radically different visions of society, but on different paths to the same destination. The debate was largely about what political scientists call ‘valence’ issues, where the argument is about which side can best realize the same shared goals.

The first issue was about Scotland, identity, and who could best encapsulate a vision of the nation. The nationalists may have a natural advantage here, but unionists also ‘own’ Scotland, and see themselves as equally patriotic, believing that the nation is best realized through union (and not, for example, through assimilation). Since the turn of the century however, the unionists have lost the ability to articulate a vision of union as anything more than ‘Britishness.’

The second issue is about union, which might seem the natural property of unionists. Yet the nationalists appropriated the language of union, even speaking of the six unions to which Scotland belongs (political, monarchical, monetary, defence, European, and social) and proposing to withdraw only from the political one.

Third is the economy, where everyone shares the aspiration to a more prosperous future. On this issue, the two sides managed to argue each other to a standstill, with a blizzard of statistics and projections based on contestable assumptions. Ignoring the caution of economists, they took economic models for predictions and produced exact figures, which the citizens rightly took with a large pinch of salt. The uncertainty and risk around these helped the ‘No’ side, which merely had to warn of possible consequences, while the ‘Yes’ side had to provide assurance.

Fourth is social welfare. While in other contexts, we might expect a clash between pro-welfare and neo-liberal visions, the Scottish debate revolved around shared visions of social democracy. ‘No’ warned that the union was needed to sustain sharing and provide resources. ‘Yes’ claimed that the welfare settlement was threatened by a right-wing government in London and could be saved only through independence.

The debating chamber of the Scottish Parliament Building by Colin. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The debating chamber of the Scottish Parliament Building by Colin. CC-BY-SA-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.This left the constitution as the main area of disagreement, but even here there was convergence. The Scottish Government’s proposals envisaged an attenuated form of independence (which some dubbed ‘indy-lite’), with a currency union, leading to harmonization of fiscal policies, shared institutions, the monarchy, and cooperation in defence. Both Scotland and the UK would remain in the European Union. For their part the ‘No’ side promised more devolution, notably in the last-minute ‘vow’ to make the Scottish Parliament the most powerful devolved legislature in the world. Both sides knew that the public clustered in the middle ground of ‘devo-max’ or ‘indy-lite’ and sought to get as close to it as possible.

In the aftermath of the referendum, all the parties were able to agree on further devolution, without the nationalists renouncing their long-term goal of independence.

This all confirms what some of us have been arguing for years:, that independence in the modern world is not what it used to be. No state is sovereign in the sense of being able to do whatever it wants. Rather, they are all entwined in webs of interdependency in a ‘post-sovereign’ order. The United Kingdom has gone through successive phases of constitutional change without worrying too much about doctrinal issues or the end point.

In this respect, the UK resembles the European Union itself. It has never rested upon the notion of a single people or a singular interpretation of its constitutional order. It has no defined end point but has evolved over time. It shares sovereignty with its member states, only occasionally worrying about where the ultimate authority lies. The EU provides such a good fit for the UK constitution that both sides in the referendum debate promised to keep it, while each threatened that a victory for the other side would put EU membership in jeopardy.

This is why Brexit poses such a challenge to our evolving constitution. The demand to take back sovereignty requires us to say where it comes back to –London or Edinburgh? While Brexit politicians in England insist on sovereignty being all in one place, most people in Scotland are quite happy with it being divided. Scotland’s relationship with the UK can evolve over time, as powers are gradually devolved and the balance shifts. The EU is another matter; one is either in or out.

In 2014 Scots voted to remain in the UK. In 2016 they voted to remain in the EU. These decisions were entirely consistent with a post-sovereign vision. Now it seems that they cannot be in both. There is a search for a new middle ground, with proposals for Scotland to stay close to the EU, but that middle ground is proving difficult to find. The case of Northern Ireland illustrates the point even more vividly. Although few people in London realised it, the EU was one of the few remaining things holding the UK together.

Featured image credit: Edinburgh Scotland City by Ant2506. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post In or out of Britain?: the big question for Scotland appeared first on OUPblog.

Ten facts about the harp

The harp is an ancient instrument found in a wide variety of sizes, shapes, and tunings in musical cultures throughout the world. In the West, the harp has been used to accompany singing in religious rituals and court music. It even appears as a solo instrument in jazz and popular music and with symphony orchestras. The harp has long held a special place in the music of Ireland, where the instrument serves as a national symbol and important component of traditional music, so in the month that includes the feast of Ireland’s patron Saint Patrick, we celebrate the harp by sharing some facts about the instrument:

1. The word “harp” originated with Venantius Fortunatus, Bishop of Poitiers.

2. The word “harpa” was first used to describe a plucked string instrument around 600 AD.

3. Between the 8th and the 18th centuries in Europe, harps were made out of single pieces of wood, some carved from the front and covered with leather, and then strung using animal parts, metal, and other materials. These harps often had a narrower range than the typical human voice.

4. Shōsōin Repository in Nara, Japan has the last two surviving angular Chinese harps, which were collected in the 9th century, but made centuries earlier.

5. Almost 150 African music cultures incorporate harps, making Africa the continent with the largest variety of harps.

Image credit: David Playing the Harp 1670 by Jan de Bray (1627-1697). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image credit: David Playing the Harp 1670 by Jan de Bray (1627-1697). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.6. The oldest Irish harp, now at Trinity College, Dublin, had legendary associations with Brian Boroimhe (926-1014), but dates back to the 14th century. It is low-headed: the upper end of its forepillar meets the neck at a point only slightly higher than the joint between the treble end of the neck and the resonator.

7. The earliest surviving Renaissance harp, now held in Eisenach, was made possibly in the 15th century in the Tyrol. It has 26 strings, stands 104 cm high, and has a delicate inlaid geometrical decoration.

8. In the West, most public harp performances were given by men until the late 19th century; beginning in the 17th century women played the harp domestically. Nevertheless, by the 19th century, the harp came to be associated with women and the first women to join symphony orchestras were harpists.

9. By the 1940s, harps began to play a part in jazz and pop music. One of the early pioneers in the United States was Robert Maxwell, graduate of the Julliard School of Music, whose original compositions and arrangements were first published around 1946.

10. Judit Kadar and Cheryl Ann Fulton held the first Historical Harp Conference Workshop, now an annual convention held in the United States, so that harp players, builders, and researchers could come together and discuss the instrument and its influence.

The above are only ten facts from the extensive entries in Grove Music Online. Did we leave out any interesting facts about the harp?

Featured image credit: Alizbar by Medunizza. CC BY – SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Ten facts about the harp appeared first on OUPblog.

On the physicality of racism

This piece is adapted from Ta-Nehisi Coates’s address at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s “Sharing Knowledge to Build a Culture of Health” conference in 2016, which is featured in the new book Knowledge to Action: Accelerating Progress in Health, Well-Being, and Equity. It has been edited for length.

When I woke up in the morning as a kid who lived in Baltimore City, I wasn’t thinking about whether I had finished my homework. I wasn’t thinking about whether I had my assignments in order. I wasn’t thinking about playing basketball after school.

I was thinking about how I was going to dress. I was thinking about how I was going to cock my hat. I was thinking about which jacket I was going to wear, and what colors were going to be on that jacket. I was thinking about how I was going to carry my book bag. I was thinking about how many young boys I was going to walk to school with. I was thinking about where those young boys were from. I was thinking about what path we were going to take to school.

When I got to school, I was thinking about who I had problems with in my classroom. I was thinking about where I was going to sit during lunchtime, whether I was going to go to lunch at all.

After school, I was thinking about when I was going to leave school, at what point and at what time. Who was going to be walking with me, where were they from, which path we were going to take home?

Each of these decisions were part of my attempt to secure the safety of my body. For kids who lived where I lived, there was a dawning awareness of the world in which we lived. And that world was violent. And that world was a world where our bodies could be threatened, where things could be done to us, and we couldn’t depend on any sort of authority figure, any sort of force within society to protect us. Our personal safety was up to us.

Conversations about race are filled with words and euphemisms to describe the impact of racism on people and communities

The summer when I was nine, my older brother and I were outside waiting for a ride when we were jumped by a group of boys we didn’t know. It never occurred to me that they would be violent towards us, but when one of them punched my brother in the face, my brother took off running; he immediately grasped the situation. I was punched too, and my brother was chased and hit some more. And as I stood under the awning of Lexington Market in Baltimore, I saw waves of young black boys coming down the street, jumping and beating on whoever might be unlucky enough to go past.

Later that summer, my 13-year-old brother bought a gun. In hindsight this fact is not as extraordinary as the fact that, for me, knowing he had a gun felt un-extraordinary. I was ultimately accountable for my own protection; I was ultimately accountable for my own physical health.

When you talk about how the young boys that I grew up around walked through the world, when you talk about the fact that my brother had made a decision at 13 that he was going to carry a handgun, when you talk about the fact that that wasn’t even unusual, you are talking about the physical safety, the danger, the very health of the body.

Conversations about race are filled with words and euphemisms to describe the impact of racism on people and communities. These ideas—about affirmative action, about job discrimination, and housing discrimination, about racial justice—all cycle back to this physicality of racism, its impact on the actual body. When we talk about racism, inequity in health is ultimately what we are talking about.

I am not confident that these conversations will change because people acquire knowledge or willpower or are spiritually moved. I think conversations change because a previous conversation becomes too expensive and unsupportable.

Featured image credit: ‘Streets of West Baltimore’, by Peeter Viisimaa, (c) iStock Photo.

The post On the physicality of racism appeared first on OUPblog.

March 29, 2017

Self-portraits of the playwright as a middle-aged man [part two]

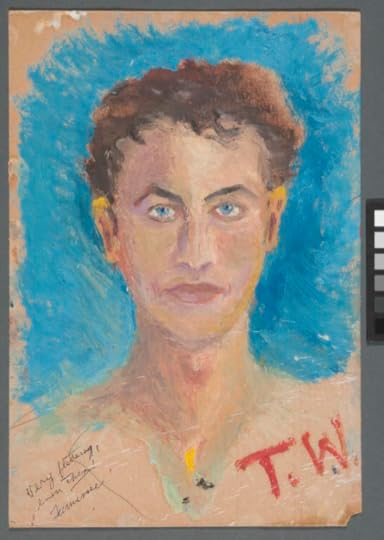

When Tennessee Williams swapped his pen for a paintbrush, his tendency to use his lived experiences as source material did not alter much. He often painted places he’d seen, people he knew, or compositions he conjured up in the limekiln of his imagination. Although Williams painted more frequently later in life, precisely as a creative outlet when his brand of theatre was no longer in vogue, he had started sketching and painting from a very early age. To follow his career as a painter is, to a large extent, to trace his life’s alterations, physically, of course, but also emotionally. As a young man in his late teens and early twenties, he painted the great outdoors. He was shy and not yet fully aware of his homosexuality, so only nature, via the various landscapes or still-lifes he produced, was allowed the privilege of returning his gaze. In college, he would eventually emerge from his shell, and by the time he graduated from Iowa and first arrived in New Orleans in the winter of 1938, he was ready to embrace life and all that it had to offer.

His paintings at this time reflect this liberated youth: he abandoned landscapes for the most part and turned to painting portraits of the people he met, knew or loved, just like his character Nightingale in the nostalgic play Vieux Carré (1977), about his first trip to the French Quarter. And one of the people there whom he first met, came to know, and finally love was—himself. Not in any narcissistic way often attributed to selfies, but in an almost Wildean, Dorian Gray sort of way. Even in this first extant self-portrait, most likely painted in 1939 when he was road-tripping with his friend Jim Parrot to California, we find the elder Williams’s self-mockery of his youthful pretensions in the phrase added in ink on the bottom left: “Very flattering, even then!” Williams would often reread entries in his youthful diaries—another form of self(ie)-expression—years later and add self-reflexive comments such as this one.

Tennessee Williams, self-portrait, oil on paperboard. Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin. Used with permission.

Tennessee Williams, self-portrait, oil on paperboard. Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin. Used with permission.In another self-portrait, this one painted circa 1947, just before the success of A Streetcar Named Desire would confirm his sense of self-worth to an endearing public, Williams displays an honest self-awareness of the realities of aging. The disheveled hair and the stylish Clark Gable mustache are visual signs of the era and proof that nearly a decade had passed since his last self-portrait. More important, thought, is the gaze, the fact that Williams can no longer look the viewer straight in the eyes. Isn’t the selfie defined by its direct eye contact with the camera lens and, by extension, the viewer? And doesn’t this direct gaze precisely draw that viewer—or voyeur—through the megabytes of internet space that separate the subject from the viewer? Here, Williams’s refusal to directly confront our gaze recalls several other self-portraits, notably Van Gogh’s, whose subject equally deflects eye contact and, consequently, elicits discomfort among its viewers. Consider the woman (Wood’s sister, in reality) in Grant Wood’s American Gothic, and all the ink spilled over her deflected gaze. Or, perhaps, in distinguishing a self-portrait from a selfies, it is not the eyes at all here that matter, but rather the mouth. Williams’s pout, or even sneer, in this painting is a far cry from the ubiquitous, 75-watt smile that defines a selfie.

When Williams’s literary career began its decline from the mid-sixties onward, he turned to drugs. His briefly sketched self-portrait from circa 1972, more a self-caricature really, captures beautifully his transition from the hell of the sixties to the purgatory of the seventies (he was, after all, Catholic now, since his brother had coerced him to convert following Williams’s brief stint in a psychiatric ward in St. Louis). Not only can he not hold the view’s gaze here, but he can barely hold his own. This self-portrait, unlike the painting from 1939, is now indeed “flattering,” and that wry smile of his owes as much to the rye he consumed as it does to the euphoria he must have felt in finally completing the manuscript of his Memoirs (published in 1975)—a book that is arguably more selfie than self-portrait.

A second self-caricature sketched a couple years later in 1974 portrays a “No Neck Monster” Williams (an allusion to Maggie’s disparagement of Mae’s children in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof) seemingly more in control of himself physically than emotionally; his depression here is rather obvious, countered, as it often was around this time, by black humour and the self-recognition that his plays were only going to be produced “off-off-off-off-off B’way,” if they were going to be produced at all.

The older Williams grew, the fewer the portraits he painted. He still painted friends, lovers and acquaintances, but the subjects of these works no longer occupy the same space on the canvas as they did in the portraits he had painted 20 years previously. The subject of these portraits is now part of a larger mise-en-scène, a composition, usually abstract or expressionistic, that deals more with a theme and less with a person: beauty (male, yes, but also androgynous), sex (often but not exclusively homoerotic), or love and immutability (physical and spiritual alike). Aware that he, too, was becoming the fanned magnolia that was Blanche DuBois in his masterpiece for the American stage, Williams nonetheless still found the inner strength and the will to paint his self-portrait.

Featured image credit: “Which Sea Gull?” (Manuscript draft of Memoirs), ink on typing paper, n.d. (ca. 1972). Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library. Used with permission.

The post Self-portraits of the playwright as a middle-aged man [part two] appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers