Oxford University Press's Blog, page 389

March 21, 2017

10 facts about the origins of American deportation policy

One of the most important political, economic, legal, and ethical questions in the United States today is immigrant deportation policy. Where did the policy come from? When and why was it introduced in the United States? Who was the target of removal law? How were deportation laws enforced? In Expelling the Poor, historian Hidetaka Hirota, visiting assistant professor of history at the City University of New York-City College, answers these questions in revealing the roots of immigration restriction in the United States. Below he provides ten things to understand about the origins of American deportation policy.

Historians have long assumed that immigration to the United States was free from regulation until the federal government started restricting Chinese immigration in the late nineteenth century. This is a myth. In fact, local and state governments regulated immigration since the foundation of the nation in the eighteenth century. Immigration control is more deeply rooted in American history than it has been thought.

The roots of immigration control in America lay in the English poor law, which allowed each parish to banish transient beggars. English settlers in American colonies enacted similar laws to prohibit the landing of indigent passengers and deport the migrant poor back to their places of origin. After the American Revolution, Atlantic seaboard states built upon the colonial poor law to develop laws to restrict the immigration of destitute Europeans. American immigration control emerged as a measure to protect public treasuries from the expenses of supporting needy foreigners.

The large influx of the impoverished Irish in the mid-nineteenth century brought about significance changes in state immigration policy. Up to the 1840s, state governments had left the implementation of passenger law to municipal officials, and law enforcement had remained lax. Driven by strong anti-Irish nativism, two Atlantic seaboard states, New York and Massachusetts, tightened passenger regulation in the late 1840s by establishing state-run agencies charged with supervising immigration. Anti-Irish nativism played a decisive role in the formation of state-level immigration control.

[image error]Petition, Boston City Council Joint Committee on Alien Passengers Records. Used with permission of the City of Boston Archives.

Although New York and Massachusetts pioneered state-level immigration control, the two states’ policies were not identical. In Massachusetts, where anti-Irish nativism grew exceptionally intense due to the state’s strong Protestant and Anglo cultural traditions, immigration policy was entirely focused on reducing undesirable immigration through landing regulation and deportation. By contrast, New York only regulated foreigners’ admission and did not deport those already residing in the state for most of the nineteenth century due to the political power of immigrants. The duties of immigration officials in New York also had humanitarian dimensions, such as the protection of admitted newcomers from fraudsters.

State-level immigration control did not develop in other major seaboard states for various reasons. In Pennsylvania, divisions among nativist politicians impeded the growth of public policy for immigration control. In southern states, such as Maryland and Louisiana, legislators’ strong interests in securing white settlers checked any attempt to discourage European immigration. In California, legislators passed several laws to restrict Chinese immigration in the mid-nineteenth century, but the State Supreme Court repeatedly struck them down. California failed to establish sustainable systems of state-level immigration control.

Just as opponents of Muslim immigration today framed immigration restriction as a matter of national security, anti-Irish nativists in the nineteenth century viewed the immigration of destitute Catholic Irish as an economic, religious, and moral invasion of American society by the British government, which repeatedly financed the passage of Irish paupers to North America. Abbott Lawrence, a Massachusetts politician, reportedly declared that he would deport all Irish paupers “up the Thames to London, and land them opposite the Parliament House, under its very eaves, if possible, while Parliament was in session!”

The enforcement of deportation policy became extremely coercive in Massachusetts when nativist politician Know Nothings controlled the state legislature in the 1850s. Agents of the Know Nothings raided public almshouses, kidnapping Irish-born inmates and illegally shipping them to Europe without fulfilling procedural requirements. Deportees unlawfully expelled abroad included American citizens of Irish descent, such as native-born children of immigrants and naturalized adult immigrants.

The question of who deserved to be American in the nineteenth century was behind the aggressive enforcement of deportation law against the Irish poor. Economic self-sufficiency based on free, independent labor defined the quality of ideal Americans. Dependent on public charity, Irish paupers appeared to destabilize the integrity of American free labor society. Anti-Irish prejudice also critically strengthened their hopelessness as people who would not become productive citizens. Deeply entangled with economic ideals, state immigration policy determined who deserved to belong to America in the most literal sense by physically removing from the nation those deemed undeserving.

State deportation policy had significant transnational dimensions. Many Irish deportees were first sent to Liverpool. The British poor law provided for the forcible expulsion of the Irish poor to Ireland. Under this law, Irish paupers sent to Liverpool were further deported to Ireland. In Ireland, local poor-law officials almost refused to accommodate the returned paupers, who they believed no longer belonged to Ireland. Irish officials even considered sending the deportees back to the United States. American deportation policy was part of a wider system of pauper regulation in the Atlantic world, which in practice made the Irish migrant poor and stateless.

State immigration laws in New York and Massachusetts eventually developed into national immigration policy. In 1876, when the US Supreme Court declared state passenger law unconstitutional, officials in New York and Massachusetts launched a campaign to nationalize state laws. The campaign resulted in the passage of the federal Immigration Act of 1882, the first legislation to regulate general immigration at the national level. Modeled on existing state laws in New York and Massachusetts, the act prohibited the landing of paupers, lunatics, and criminals, setting the groundwork for subsequent federal laws for immigrant exclusion and deportation. The northeastern states’ laws laid the foundations for American immigration policy.

Featured image credit: “Ocean Sunset” by John Hilliard. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post 10 facts about the origins of American deportation policy appeared first on OUPblog.

[image error]

Society of Cinema and Media Studies: the 2017 conference guide

This March, the Oxford University Press cinema and media studies editorial and marketing team will see you in chilly Chicago for the SCMS annual conference. We’ve listed our favorite sessions below. And, don’t forget to test your film expertise with our film director quiz below.

Wednesday, 22 March

10:00 – 11:45 AM

Visual and Print Media: Adaptation, Influence, Intertextuality featuring Sarah Gleeson-White, Priyanjali Sen, Andrea Schmidt, and Philip Scepanski

Thursday, 23 March

1:00 – 2:45 PM

Documenting US History featuring Susan Courtney, Laura LaPlaca, Nicole Strobel, Michelle Kelley, and Ashley J. Smith

5:00 – 6:45 PM

Experiments in Feminine Poetics featuring Rebekah Rutkoff, Paige Sarlin, Noa Steimatsky, and Ara Osterweil

Friday, 24 March

12: 15 – 2:00 PM

Race in American: Nontheatrical Film Mining Archives, Expanding Canons featuring Marsha Gordon, Allyson Nadia Field, Colin Williamson, Noah Tsika, and Laura Isabel Serna

Sunday, 26 March

1:00 – 2:45 PM

Playing with the Archive: Memories of the Past in Contemporary Spanish Film and Television featuring Dean Allbritton, H. Rosi Song, Tom Whittaker, Sarah Thomas

While you’re around, take time to visit our Oxford University Press Booth. You’ll be able to browse new and featured books which will include an exclusive 20% conference discount. Stop by the booth the last two hours of every exhibit day for special flash sale offers. Pick up complimentary copies of journals which include Screen and Adaptation . You can also receive free access to our online resources including Oxford Handbooks Online, Very Short Introductions Online, and Oxford Reference.

Quiz background image: Alfred Hitchcock directing Family Plot inside Grace Cathedral, San Francisco, California by Stan Osborne. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image: Sony lens walimex camera. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Society of Cinema and Media Studies: the 2017 conference guide appeared first on OUPblog.

S. M. Lipset and the fragility of democracy

Seymour Martin Lipset passed away eleven years ago. If he had lived, he would have celebrated his 95th birthday on 18 March. Today, his prolific scholarship remains as timely and influential as when he was an actively engaged author. Google Scholar reports 13,808 citations between 2012 and the beginning of 2017. All of Lipset’s papers have been collected at the Library of Congress and soon will be available to researchers. One cannot think of other contemporary social scientists of his caliber who remain as relevant.

Two years before Lipset’s passing, the Seymour Martin Lipset Lecture called ‘Democracy in the World’ was jointly inaugurated by the National Endowment for Democracy and the Munk School of Public Affairs at the University of Toronto. The annual lecture, delivered in both the United States and Canada, is subsequently published in the Journal of Democracy. The 13 lectures delivered thus far reflect and extend Lipset’s concerns with the conditions needed for the emergence and sustaining of democracy, and do so by moving outside the Anglo-American and Eurocentric world to Russia, China, Latin America, and the Arab world (e.g., Pierre Hassner’s “Russia’s Transition to Autocracy” (2007), Abdou Filali-Ansary’s “The Languages of the Arab Revolution,” (2012), and Anthony J. Nathan’s “The Puzzle of the Chinese Middle Class.” (2016).

In all the discussions of the difficulty of establishing democratic governance and its fragility in newly democratized states, there had been little concern with anti-democratic drifts in Western Europe, the Anglo-American countries, and particularly the United States. But recently, new fears have arisen, as nationalist movements opposed to immigrants and globalization have grown in these countries. Larry Diamond, writing shortly before the outcome of the 2016 US election, discerned the growing decline in support for pluralism and democratic procedures. His discussion refers back to Lipset’s analysis, co-authored with Earl Rabb in 1978, of “procedural extremism,” where diverse perspectives become defined as illegitimate and their expression is shut down.

Political scientist: Seymour Martin Lipset by Hoover Institution. Fair Use by Wikimedia Commons.

Political scientist: Seymour Martin Lipset by Hoover Institution. Fair Use by Wikimedia Commons.Not only has Lipset been called on to explain current challenges to democracy, but his past writing has also been invoked to understand why particular population groups have been mobilized to support those challenges. Donald Trump’s rise to political power and election as President is now linked to Lipset’s concept of working class authoritarianism, published in Political Man (1960). From news analyses to empirical academic studies (presciently, Hetherington and Weiler 2009; MacWilliams 2016), authors attribute a considerable part of Trump’s attraction of working class voters to the latter’s authoritarian views.

Lipset’s affection for Canada and his use of that country as a contrast to the United States, thus illuminating critical characteristics of both countries, continues to inspire others to mine differences and similarities between the two and to test Lipset’s explanations for why differences continue to exist. For example, Moore et al. (2016) examine differences in attitudes toward crime and justice, and conclude from parallel surveys done on each side of the border that Lipset’s (1990) hypothesis about value differences has strong empirical support. Lipset’s model for the close study of two such similar countries remains inspirational and was recognized by the Canadian Politics Section of the American Political Science Association, beginning in 2011, when the Section inaugurated its book prize award and named it in his honor.

Lipset’s work on political parties and social stratification are additional areas that continue to provoke new questions and new research. Bornschier (2009) reviews work on the continuing relevance of the concept of cleavage to party formation in both old and new democracies. He concludes that, by putting “primary emphasis on the enduring character of collective political identifications resulting from large-scale societal transformations as the defining element of cleavages,” the concept retains its broad efficacy.

Similarly, Achterberg (2006) examines the continued relevance of social class in understanding voting behavior in 20 western countries. Using party manifestos and data from the World Values Surveys, he concludes, in an elaboration on Lipset, that societal changes and the emergence of new issues have not caused class voting to disappear but to undermine its dominance.

Happy birthday Marty—friend, mentor, inspiration. Rest in peace—your work lives on.

Featured image credit: Ottawa – ON – Parliament Hill by Wladyslaw, CC BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post S. M. Lipset and the fragility of democracy appeared first on OUPblog.

A conversation with clarinetist and author Albert Rice

Albert Rice, author of the recently released Notes for Clarinetists, sat down with Oxford University Press to answer a few questions about the clarinet and beyond. Besides playing music and writing books on the subject, Rice also works as an appraiser of musical instruments. In our talk with the multi-hyphenate, we touch upon loving music from an early age, his personal influences, his dedication to research on the history of the clarinet, and how a car accident and subsequent hospital stay ended up positively changing his music career.

Why did you become a musician, was your family musical?

Yes, my mother was an opera singer in southern California. I was exposed to music and concerts at an early age and my father was an opera buff.

Was the clarinet the first instrument that you played?

No, I played the piano a bit and had a few accordion lessons, but neither really interested me. My mother knew a clarinetist in the neighborhood and suggested that I try it. I was more formally introduced in elementary school at eleven, and soon, my parents engaged a good private teacher. I played in school bands through high school and college, as well as school and community orchestras. In 1970, I played in the Pasadena Rose Parade.

Who were your most influential clarinet teachers?

Kalman Bloch, principal clarinetist of the Los Angeles Symphony Orchestra; Mitchell Lurie, at the University of Southern California; and Rosario Mazzeo, in Carmel, California, formerly bass clarinetist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra. I also worked with Harold Wright, principal clarinetist of the Boston Symphony at the Tanglewood Music Festival in 1978. Working with these outstanding teachers and musicians and hearing them perform were major influences.

Who were other influential musicians that you worked with?

Charlotte Zelka was a very fine pianist who I worked with for many years in the Jugenstil Trio for piano, violin, and clarinet and in the Almont Ensemble for piano, clarinet violin, viola, and cello. We performed widely for years and recorded several works during the 1980s and 1990s. A number of clarinetists, violinists, violists, and cellists that I have worked with over the years have been influential, as well as hearing and meeting professional clarinetists at meetings of the National and International Clarinet Society, beginning in 1973.

“Clarinet” by Richard Revel, Public Domain via Pixabay.

“Clarinet” by Richard Revel, Public Domain via Pixabay.What started you on clarinet research?

In 1971, on my 20th birthday, I had a solo automobile accident that caused a compound broken femur. (I was fighting a spider and ran into the freeway center divider.) I was in traction for 30 days, and then 25 days to recuperate and do physical therapy. I was very bored and had previously read two books on the clarinet, F. Geoffrey Rendall’s The Clarinet: Some notes on its history, and Oskar Kroll’s, The Clarinet. I asked my mother to bring me these books to re-read while I was stuck in bed, and I thought about a lot of subjects and details in these books. I promised myself that I would re-check the research these authors had presented. That was the beginning of my obsession with clarinet research.

When did you start becoming interested in early clarinets?

This was in 1976 and 1977 when I researched and wrote my Master’s dissertation at Claremont Graduate School on Valentin Roeser’s 1764 Essai d’instruction. During the 1980s, as a graduate student, I saw the clarinets in the Curtis Janssen Collection at the Claremont Colleges and later was allowed to write a brief description of each of them for the curator. In 1987, after finishing a Ph.D. at Claremont Graduate School, I became the museum’s curator (half-time) and began compiling a computer based inventory of about 500 instruments in the Kenneth G. Fiske Museum, as it was then called. In addition, I attended annual conferences of the American Musical Instrument Society, a group of curators, restorers, enthusiasts, and collectors. During these trips, I was able to study instruments and clarinets at collections through the U.S. and Europe.

How did you become a professional appraiser of musical instruments?

A professional appraiser and restorer of mechanical musical instruments who had consulted at the Fiske Museum suggested that I learn the profession of musical instrument appraisal. I took classes and attended meetings of the American Association of Appraisers. Since 1990, I have prepared written appraisals for all types of musical instruments.

How many books have you written?

Five. The first three were on the history of the clarinet and partially based on my doctoral dissertation finished in 1987. They are The Baroque Clarinet (1992), The Clarinet in the Classical Period (2003), and From the Clarinet d’Amour to the Contra Bass: a History of Large Size Clarinets, 1740-1860 (2009), all published by Oxford University Press. In 2015, I wrote a catalog describing about 600 musical instruments of all types for my friend Marlowe A. Sigal, who lives close to Boston. His collection is the finest and most comprehensive in private hands, the title is Four Centuries of Musical Instruments: The Marlowe A. Sigal Collection, published by Schiffer Publications. The most recent book is Notes for Clarinetists: A Guide to the Repertoire published in 2017 by Oxford University Press. It is written for undergraduate college students and other clarinetists. It discusses 35 solo works by composers from Johann Stamitz to Karlheinz Stockhausen. A musical analysis is in each chapter with information on the composer.

Have you written articles and on what subjects?

I have written 75 articles, mostly on the the clarinet, its history, clarinet method books, and different types of instruments, including, contra bass clarinets, small sized clarinets, and a clarinet automaton. I have also written on brass instruments, the early saxophone and its dispersion through Europe and America, musical instrument makers, 35 reviews of books, and many encyclopedia articles.

Featured image credit: “Clarinet Music Melody” by Imaresz. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post A conversation with clarinetist and author Albert Rice appeared first on OUPblog.

The value of making connections at the ACDA Convention 2017

A group of OUP staff and composers have just returned from the biennial American Choral Directors’ National Convention. Representatives of every facet of the choral world were there: professional choirs, educators, college choirs, church musicians, and community choirs. The vibe across the US choral scene at the moment is undoubtedly positive: attendance at the convention was at a record high, and many spoke positively about the state of the sector.

As a European, the scale of an event like this is breath-taking – there are few music conferences in the UK that warrant their own app and that take over a city! The sheer number of delegates was deeply impressive, with some 5,000 choral directors, alongside 10,000 choral singers, converging on a bitterly cold Minneapolis for four days of seminars, concerts, and networking.

So what drives such impressive turnout at an event such as this? In part it’s down to the sheer size of the American population: five times that of the UK. There is also much greater focus in North America on attendance at conventions; perhaps the enormity of the geography means that those in the arts don’t so easily meet each other informally, and so attendance at events such as this is given a greater priority.

But a significant contributor to the success is the impressive level of participation in choral music. Current data on the number of people involved in collective singing is difficult to come by, in part because there are large sections of the choral sector that don’t fit any formal structure.

Alongside the established professional, church, school, and community choirs are huge swathes of informal groups that come and go under the radar. The last US research study I know of that attempted to quantify the size of the US choral market was undertaken by Chorus America in 2009. It reported that 18% of US households had one or more adults participating in a chorus, and almost 270,000 choruses across the country. Based on anecdotal evidence from last week’s convention, that number has almost certainly increased.

Paradoxically, despite the size of the choral population, everyone seems to know each other. We were proud to have many of our composers in attendance: established names in the choral music world, including Bob Chilcott, Will Todd, Sarah Quartel, Cecilia McDowell, Gabriel Jackson, and Alan Bullard alongside new US names Elaine Hagenberg, Howard Helvey, and Connor Koppin.

The opportunity for choral directors to meet and talk with the people behind the music they work on with their choirs was powerful. And the OUP reading session, which was filled to capacity, gave an opportunity for those composers to give the choral directors attending the conference a unique insight into the new music they have written.

Congratulations to ACDA on such an impressive event.

Staff, composers and delegates from ACDA 2017. Image copyright: Oxford University Press.

Staff, composers and delegates from ACDA 2017. Image copyright: Oxford University Press.Featured image credit: Picture of OUP stand. Copyright: Oxford University Press.

The post The value of making connections at the ACDA Convention 2017 appeared first on OUPblog.

March 20, 2017

Experiencing happiness versus appearing happy

Each year, the International Day of Happiness is celebrated on 20 March. First celebrated by the United Nations in 2013, this day is now celebrated by all member states of the United Nations General Assembly to recognize happiness and well-being as a “fundamental human goal.” Celebrations on this day in the past included ceremonies held by Ndaba Mandela and Chelsea Clinton, as well as the creation of the world’s first 24-hour music video with Pharrell Williams.

Actually experiencing happiness and appearing happy are two very different things though, as explained by Donna Freitas, author of the The Happiness Effect. In the age of social media, it’s easy (and oftentimes preferred) to curate personal posts to give others an impression that you’re constantly happy. This is the “fundamental human goal” after all. However, real-life repercussions of this may actually include sadness, envy, and frustration in spite of the online utopia that is created. We sat down with Donna to discuss the meaning of the phrase, “the happiness effect” and how it relates to the use of social media by young adults.

Featured image credit: Stuart Semple HappyClouds 2009. CC0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Experiencing happiness versus appearing happy appeared first on OUPblog.

Cicero’s On Life and Death [extract]

In this extract from the introduction to Cicero’s On Life and Death, Miriam T. Griffin describes the experiences of Cicero during the reign of the First Triumvirate, his increasing disillusionment with politics, and what led him toward writing about philosophy instead.

In 58 BC, Roman politics was paralyzed by the coalition of Pompey, Crassus, and Caesar, known as the First Triumvirate. Marcus Tullius Cicero, Rome’s greatest orator, who had successfully climbed the political ranks to reach the level of consul, struggled to maintain his independence while on occasion lending reluctant oratorical support to their projects and associates. He also started to put his excess energy, stylistic brilliance, and superabundant vocabulary into philosophy, a new domain for Latin literature. Cicero turned first to rhetorical and political theory, congenial subjects which would keep him before the public as a leading statesman. To this period we owe the monumental dialogues On the Orator and On the Republic. Cicero was to list them, in On Divination II, among his philosophical works, most of which, including those in On Life and Death, were written a decade later. Both dialogues were designed to emulate Plato, the former inspired by his Gorgias, the latter by his Republic. On the Laws, meant to recall another Platonic dialogue, was left incomplete a few years later. Despite their titles, both political works are distant from abstract Platonic thought, and On the Orator and On the Republic, though set in the past, are firmly rooted in contemporary concerns at Rome.

As the end of the fifties BC approached, the coalition that had been dominating political life began to crumble. Cicero did what he could to avert civil war, but when war came, he felt he must follow Pompey to the east. After the defeat at Pharsalus in August of 48 BC, Cicero abandoned an active role in the war. Although indifferent to Caesar’s reforms, believing that the Roman Republic was the perfect system of government, he was sufficiently moved by Caesar’s clemency towards his virulent opponent Marcus Claudius Marcellus, to speak appreciatively of the Dictator in autumn 46 before the senate. Combining flattery with advice and admonition, the later published speech On Behalf of Marcellus is the father of all the imperial panegyrics, starting with Seneca’s admonitory praise of Nero in De Clementia.

When news of Pompey’s death arrived, Caesar had been made dictator and could make peace and war on his own initiative. In retrospect, Cicero was to say that “once a single man came to dominate everything, there was no longer any room for consultation or for personal authority, and finally I lost my allies in preserving the republic, excellent men as they were.” He returned to philosophy, writing copious works in many of which he celebrated those excellent men.

“Bust of Cicero, Musei Capitolini, Rome, Half of 1st century AD” by Glauco92. Creative Commons via Wikimedia Commons.

“Bust of Cicero, Musei Capitolini, Rome, Half of 1st century AD” by Glauco92. Creative Commons via Wikimedia Commons.In his preface to the second book of On Divination, Cicero discusses his motives for writing about philosophy: the need for a substitute for political to the Republic, and the intellectual challenge of rendering Greek philosophy in elegant Latin. His response to these needs would lead him, he hoped, to increase the glory of Latin literature himself and to encourage contributions from others, as well as to develop a practical ethics for his peers, especially the young.

In the Tusculan Disputations, Cicero is more emphatic about his aims than elsewhere. If in On Divination he looked forward to the Roman people being independent of Greek writers in the study of philosophy, here he insists on Roman ability to excel the Greeks as they have in other branches of literature, defends the Latin language as an instrument for writing philosophy, and casts himself in the role of teacher of the young. There is, however, another motive which Cicero mentions in other works as well, but which dominates this work, albeit in a less explicit way. That is Cicero’s recent bereavement. In January of 45 his beloved only daughter Tullia gave birth to a son in Cicero’s house in Rome. She was then moved to his villa at Tusculum where, in the middle of February, she died, apparently of complications in the birth. Her child lived only a few months. Cicero felt that he had fought bravely against fortune in the past but was now wholly defeated: the attacks of his enemies, his humiliating exile, had been easier to bear than this. As he wrote to Atticus, “For a long time it has been my part to mourn our liberties and I did so, but less intensely because I had a source of comfort.” He read every work on consolation he and Atticus possessed, but the grief was stronger than any solace they could offer. And so, in the solitude of his villa at Astura, Cicero began writing his own Consolation to himself. He collected examples and other material throughout March “and threw them into one attempt at consolation; for my soul was in a bruised and swollen state, and I tried every means of curing its condition,” as he wrote later in the Tusculan Disputations. He knew that he was going against the advice of the Stoic Chrysippus, among others, not to try to apply remedies to fresh bruises. He found writing a distraction but was interrupted by fits of weeping. He insists to Atticus, who agreed with others that he should return to Rome and his old activities, that he is a changed person: “the things you liked in me are gone for good.” The Consolation “reduced the outward show of grief; grief itself I could not reduce, and would not if I could.”

Featured image credit: “Colosseum” by The_Double_A. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Cicero’s On Life and Death [extract] appeared first on OUPblog.

Trump in Wonderland

“Humpty Dumpty: When I use a word, it means just what I choose it to mean – neither more nor less.

Alice: The question is whether you can make words mean so many different things.

Humpty: The question is which is to be master – that’s all.

— Alice Through the Looking-Glass by Lewis Carroll

Four days after Donald Trump’s inauguration, an unlikely novel reached the top of Amazon’s bestseller list. It was not the latest potboiler by John Grisham, Stephen King, or any other likely suspect. Topping the list on 24 January was 1984, George Orwell’s 68-year-old masterpiece about a dystopian society in which the ruling authorities routinely alter the meanings of words and facts to suit their own purposes.

Trump is not to be confused with Orwell’s Big Brother. But he has perhaps moved in that direction by making and doubling down on easily refuted or unverifiable claims about topics ranging from the size of his inaugural crowds, to the extent of voter fraud in the 2016 election. Even more audaciously, Trump advisor Kellyanne Conway put forth the claim that actual facts could be refuted by “alternative facts.” All this is an extension of Trump’s longtime use of what he calls “truthful hyperbole,” which others might call a contradiction in terms. He also has a long history of relying on alternative facts on topics ranging from climate change to Barack Obama’s birthplace.

In addition, Trump has benefited from disinformation coming from fake news sites, which carried reports that Pope Francis and Denzel Washington had endorsed him, along with reports that the Clinton campaign was engaging in election fraud. Fake news is typically produced on websites aiming to make a higher return on ads by driving up traffic. But in 2016 they may have been intended to drive election returns as well.

A New York University study found that the average American could recall four times as many pro-Trump false news stories as pro-Clinton stories. Moreover, Trump has ensured that this phenomenon can only grow by inviting the fake news website Gateway Pundit (sample headline: “Exposed — Hillary Hitman Breaks Silence”) to take part in White House news briefings.

Illustration of Humpty Dumpty and Alice from Through the Looking Glass by John Tenniel, 1871. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Illustration of Humpty Dumpty and Alice from Through the Looking Glass by John Tenniel, 1871. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.In this political environment, all that stands between President Trump and a picture of reality more to his liking is the media. Although he reaped the benefits of heavy publicity as he moved from dark horse to front runner during the primaries, coverage of Trump’s personal traits and policies has been consistently – often brutally – negative. A Harvard study of general election news found that, among stories about Trump with a clear tone, 77% were negative. Data from previous studies suggest that this was the worst press endured by a presidential nominee in at least three decades. This critical coverage has been reflected in historically low public approval ratings for Trump, both as a party nominee and as president-elect.

So it’s little wonder why that Trump has pioneered the use of social media – preeminently Twitter — to provide an unmediated channel of communication to the electorate. In so doing he benefits from the ways people process information. It is a commonplace observation that increasing political polarization has affected the sources of information that people seek out, so that any new information they obtain tends to reinforce what they already believe. But less conscious process are at work as well. Various mechanisms related to selective perception lead people to unconsciously skew the information they are exposed to in the direction of what they already believe. And the phenomenon of cognitive misattribution leads people to forget the source of information they retain. Thus, they may not even be aware that their beliefs are based on sources that have low credibility.

But for Trump’s purposes, it is not enough to beat the media at its own game by putting the first rough draft of history out himself. It is also necessary to discredit his journalistic competitors, both by contradicting their version of reality and by luring them into an oppositional and adversarial stance that undermines their claim to be unbiased chroniclers of events. To this end, he has launched what he calls a “running war with the media,” which he regards as “the opposition party.” He has berated journalists as “the most dishonest human beings on earth” and complained about their “dishonesty, total deceit and deception.”

Trump’s greatest advantage in this enterprise is that journalists may help do his job for him. Because of their perceived partisan biases, negativism, sensationalism, and other sins, journalists have already come dangerously close to losing their claim to representing the public in speaking truth to power. A 2016 Gallup poll found that public trust in the media has sunk to its lowest level – only 32% – since Gallup began asking the question in 1972.

Even that number is likely to drop if journalists take Trump’s bait by tipping over into what New York Times columnist Ross Douthat calls “hysterical oppositionism.” The shrillness of such a response is illustrated by Washington Post media critic Margaret Sullivan’s column headlined “A hellscape of lies and distorted reality awaits journalists covering President Trump.” Similarly hyperbolic are stories and columns comparing Trump to Hitler or fascists more generally. The problem with such an in-your-face approach is that it turns journalists into partisans, bringing them down to Trump’s level. And like Br’er Rabbit’s encounter with the tar baby, the more they push back, the closer he’ll stick to them.

The best way for journalists to resolve this dilemma is to trust the public. That means respecting the line between fact-based and opinion journalism, tamping down the editorializing and the attitude, and putting out the facts for everyone to see. Yes, a proportion of readers and viewers will see a funhouse mirror image of the picture they paint. But this is hardly limited to news about Trump. And his poll ratings prove that his public image is not immune to bad press. In the end, Trump’s attempts to construct an alternative political reality will founder because his claims come down to the old Marx Brothers punchline: “Who you gonna believe? Me or your own eyes?”

Featured image credit: Donald and Melania Trump speak at the post-inauguration Armed Services Ball on January 20, 2017 by Sgt. Kalie Jones. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Trump in Wonderland appeared first on OUPblog.

Are you an expert on international organizations? [quiz]

With the upcoming publication of Oppenheim’s International Law: United Nations and the highly anticipated launch of Oxford International Organizations (OXIO), international law has never been more relevant.

Oppenheim’s International Law: United Nations is an authoritative and comprehensive study of the United Nations’ legal practice. The United Nations, whose specialized agencies were the subject of an Appendix to the 1958 edition of Oppenheim’s International Law: Peace, has expanded beyond all recognition since its founding in 1945. This volume represents a study that is entirely new, but prepared in the way that has become so familiar over succeeding editions of Oppenheim.

Oxford University Press and the Manchester International Law Centre (MILC) are developing a database of annotated documents pertaining to the law of international organizations (OXIO). This will include documents such as resolutions of international organizations, reports of legal advisers, judicial decisions, international agreements, or any act of legal relevance.

Along with Oppenheim and OXIO, Judicial Decisions on the Law of International Organizations and The Oxford Handbook of International Organizations offer a comprehensive analysis and commentary on the role of international organizations today and provides commentaries from leading experts in the field of international institutional law organised by legal category.

From the United Nations to UNICEF, this quiz will put your international law knowledge to the test.

Featured image credit: “Flag of United Nations”, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Are you an expert on international organizations? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

March 19, 2017

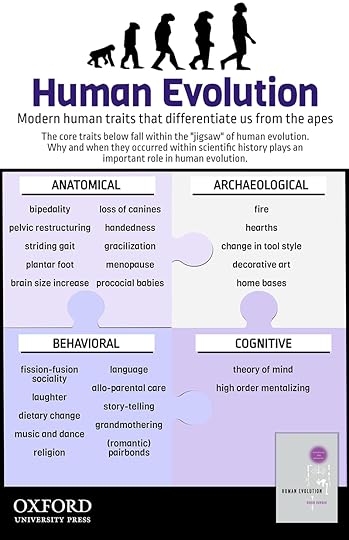

Human evolution: why we’re more than great apes

Palaeoanthropologists have used the anatomical signs of bipedalism to identify our earliest ancestors, demonstrating our shared genetic heritage with great apes. However, despite this shared history, human evolution set out on a trajectory that has led to significant distinctions from other primates.

In this shortened excerpt from Human Evolution: Our Brains and Our Behavior, evolutionary psychologist Robin Dunbar explains the link between culture and the human brain—and how that connection distinguishes us from other primates.

We share with the other great apes a long history, a largely common genetic heritage, a similar physiology, advanced cognitive abilities that permit cultural learning and exchange, and a gathering and hunting way of life. And yet we are not just great apes. There are some radical differences. The least interesting of these, although the ones that almost everyone has focused on, are the anatomical differences, and in particular our upright bipedal stance. In fact, most of these traits are just bits of early remodeling to allow a mode of travel that became a route out of certain extinction as the Miocene climate deteriorated and the tropical forests retreated. Much of the rest of the debate has hinged around instrumental behaviors like tool-making and tool use. But in reality these are cognitively relatively small beer – even crows make and use tools, with a brain that is a fraction the size of a chimpanzee’s. The substantive difference lies in our cognition, and what we can do inside our minds. It is this that has given us Culture with a capital ‘C’, culture that produces literature and art.

Over the last two decades, a great deal of research has been done – and even more ink spilled in learned journals – arguing the case for culture in animals, and especially in the great apes. The field has even coined a name for itself: panthropology, the anthropology of Pan, the chimpanzee. It should come as no surprise that behaviors and cognitive abilities that characterize modern humans are also found in some form in our nearest relatives. That is in the nature of evolutionary processes: traits seldom arise completely de novo out of the blue. In most cases, they arise as adaptations of existing traits, which become exaggerated or radically modified under the influence of novel selection pressures. We shall examine some of these later. For the moment, the important point to establish is that, yes, humans and chimpanzees share the ability to transmit behavioral patterns socially by cultural learning, and, yes, we can reasonably argue for culture in chimpanzees and other great apes, but the reality is that what apes do with their cultural abilities simply pales into insignificance by comparison with what humans do. This is not to belittle what monkeys and apes do, but rather to identify the substantive issue that seems to get overlooked in all the brouhaha and excitement: humans somehow raised the whole game by a great deal more than just a couple of notches. How did they do this, and why?

What differentiates humans from the apes?

What differentiates humans from the apes?There are probably two key aspects of culture that stand out as being uniquely human. One is religion and the other is story-telling. There is no other living species, whether ape or crow, that do either of these. They are entirely and genuinely unique to humans. We know they must be unique to humans because both require language for their performance and transmission, and only humans have language of sufficient quality to allow that. What is important about both is that they require us to live in a virtual world, the virtual world of our minds. In both cases, we have to be able to imagine that another world exists that is different to, and separate from, the world we experience on an everyday basis. We have to be able to detach ourselves from the physical world, and mentally step back from it. Only when we can do this are we able to wonder whether the world has to be the way it is and why, or imagine other parallel worlds that might exist, whether these are the fictional worlds of story-telling or para-fictional spirit worlds. These peculiar forms of cognitive activity are not trivial evolutionary by-products, but capacities that play – and have played – a fundamental role in human evolution.

What underpins all this cultural activity is, of course, our big brains, and this might ultimately be said to be what distinguishes us from the other great apes. Seen on the grand scale of the last six million years, hominin brain size has been on a steady upswing in which brains trebled in size from their ape-like beginnings among the australopithecines to the brains of modern humans. This seems to suggest that there has been continuous upwards pressure for bigger and bigger brains over time. However, this does not necessarily mean that the selection pressure for larger brains has been increasing steadily over time. In fact, the continuous increase over geological time is an illusion, created by pooling specimens from the different species together. Separating the species out gives a pattern that is more suggestive of punctuated equilibria: each new species generates something more akin to a rapid increase or phase shift in brain size when it first appears, and then brain size stabilizes across time.

To a large extent, the trajectory that defines our pathway over these 6–8 million years reflects the dramatic changes in brain size and organization that mark out the sequence of events that makes up this story – the speciations, the migrations, the extinctions, and the cultural novelties that litter the timeline of hominin evolution. Associated with these changes in brain size are a number of other core traits, some of which we can infer from the archaeological record and some of which we know reliably only from modern humans. Some are anatomical, some behavioral or cognitive, but all have to be fitted into a single seamless sequence against both the changes in brain size (and hence group size) and the constraints of time, as well as the archaeological record. It is this triangulation between the different sources of information that makes our task possible, since it allows us much less room for speculative maneuver than has hitherto been the case. We cannot assemble the pieces of the jigsaw in any random order and simply make up some plausible story for the particular pattern we happen to favor. Instead, our approach will allow us to provide principled reasons for assembling the pieces in a particular order – or at least arriving at a limited number of alternative possible ways of doing so.

Featured image credit: Gorilla sitting near grey rock wall by Jose Chomali. CCO public domain via Unsplash.

The post Human evolution: why we’re more than great apes appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers