Oxford University Press's Blog, page 391

March 17, 2017

A cross-section of the Earth

“In every outthrust headland, in every curving beach, in every grain of sand there is a story of the earth.” – Rachel Carson (American zoologist), 1907–1964

We now know that the Earth is many billions of years old, and that it has changed an unimaginably number of times over millennia. But before the mid-eighteenth century we believed that the Earth was only a few thousand years old.

Then scientists (who we now call geologists) began to explore the Earth’s layers and found fossils, suggesting it was much, much older than they first thought. In the nineteenth century scientists started to study seismology, and so our knowledge of the deep Earth took shape. We also began to look up, exploring the skies, the atmosphere, and eventually we made it in to space itself.

But what are these layers made up of? How many are there and what is their impact on the whole?

We have collected together a brief summary of the different layers of the Earth to create the below infographic, to help start you off on your journey of discovery.

Download the graphic as a PDF or JPG.

Featured image credit: Mountains by Victor Filippov. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post A cross-section of the Earth appeared first on OUPblog.

March 16, 2017

The hygge of psychoanalytic psychotherapy

The Danish concept of ‘hygge’ has captivated the British imagination. Pronounced runner-up word of the year, it seems a fitting counterpoint to the word ‘post-truth’ in first place: an apt response to the seismic political shifts of 2016. Hygge is difficult to translate: it is not a concrete entity, but something akin to a cozy, warm, and homely feeling, a sense of familiarity, a state of mind in which all psychological needs are in balance. The antonym of ‘hygge’ is ‘uhyggelig’, something that unsettles, disturbs, and hints at darker undercurrents that undermine the status quo.

We may think of psychoanalysis as uhyggelig: its exploration of the mind reveal unconscious beliefs, wishes, motivations, and feelings associated with sexual and aggressive impulses that are unacceptable to the conscious mind. Yet, although they disturb, these feelings evoke a strange sense of familiarity, that somehow they have been previously known. Freud captured this paradox in his 1919 essay The Uncanny translated from the German word ‘unheimlich’. Unheimlich is the opposite of ‘heimlich’, which means what is familiar and agreeable – something perhaps similar to hygge. Freud proposes that the uncanny’s power to disturb is precisely because “it is in reality nothing new or foreign, but something familiar and old”. For what is uncanny has in fact been always known: it is the projection of repressed infantile beliefs, fantasies, and impulses that have remained hidden in the unconscious but now come to light.

The paradox of psychoanalytic therapy is that its effectiveness lies in its ability to create anxiety as a necessary impetus for psychic change, yet at the same not destabilize the patient to the extent that he is rendered defenseless and incapacitated. The psychoanalytic process is one of careful titration – the person must be gradually introduced to the contents of his mind so that its previously unconscious parts may in time be integrated.

Hygge by Jovi Waqa. CC0 public domain via Unsplash.

Hygge by Jovi Waqa. CC0 public domain via Unsplash.Psychoanalysis – its hygge and uhyggelig – perhaps explains why it remains at the edge of medicine and psychiatry as a therapeutic method. The realm of the unconscious is fundamentally inaccessible and only revealed to us through its derivatives: dreams, slips of the tongue, mannerisms, and symptoms. Its mysterious and ephemeral nature is at odds with the positivism of medical science where the course of illness can be detected, diagnosed, and treated by measuring concrete changes in the body’s living matter.

The psychoanalytic approach, by contrast, is focused on subjective experience, exploring the vagaries and vicissitudes of the human mind. As we are reminded by ‘hygge’, feelings are more difficult to put into words, they cannot be seen and are difficult to quantify, yet may be associated with hidden meanings, childhood traumas, and unconscious fantasies, which underlie the symptoms for which patients come for help. The nature of the psychoanalytic instrument, unlike the surgeon’s scalpel, is the same as the object of its treatment: one mind interacting with another, the emotional receptivity of the therapist containing the emotional distress of the patient, one unconscious listening to the other talking.

Medical psychotherapy is a small branch of psychiatry whose specialist practitioners are triple trained as doctors, consultant psychiatrists, and psychotherapists – doctors of the brain, body, and mind.

Psychoanalytic thinking, however, has not been completely lost from medicine. Medical psychotherapy is a small branch of psychiatry whose specialist practitioners are triple trained as doctors, consultant psychiatrists, and psychotherapists – doctors of the brain, body, and mind – to have the skills and expertise to integrate the physical and the psychological, the latest neuroscientific findings with unconscious psychodynamic processes, and the evidence base of psychological therapies with quotidian therapeutic patient contact. Promoting the central therapeutic value of relationships and a developmental perspective of mental health and illness, they offer meaningful psychological interventions for the complexities and comorbidities of serious mental illnesses and personality disorders that cannot be reduced to biochemical mechanisms. Or at least, this is the ideal.

Medical psychotherapy is paradoxically situated at the edges of psychiatry whilst also at its core. Consultant Medical Psychotherapists may offer expertise in the management and treatment of complex cases, but also provide ‘cradle to grave’ training in the psychotherapeutic approach for all stages of professional development – from medical student to junior doctor to consultant psychiatrist. This enables doctors of all specialisms – not just psychiatrists – to progress from how to ‘do’ the curriculum-mandated whole person medicine, empathy, and communication skills, into how to ‘be’.

Freud was a neurologist, not a psychiatrist, and hoped that psychoanalysis would eventually be integrated within a scientific medical and neurobiological framework. He would surely, therefore, be pleased with the rapidly expanding field of neuropsychoanalysis and the growing evidence base for the effectiveness of psychoanalytic psychotherapy. But he might also agree that the psychoanalytic endeavor will never be mainstream or acceptable to all, will continue to evoke bewilderment or ridicule, and that its subversive power stems from the uncanny tension between its hygge and uhyggelig.

Featured image credit: Hygge by Worthy Of Elegance. CC0 public domain via Unsplash.

The post The hygge of psychoanalytic psychotherapy appeared first on OUPblog.

Why we should care about Singapore [excerpt]

Contemporary Singapore has transformed into a “global city,” and remains an important player in international affairs. One of the original “Four Asian Tigers,” Singapore’s economy has grown into one of the most competitive and dynamic economies in the world. However, Singapore faced great adversity on its journey towards modern power.

In this shortened excerpt from Singapore: Unlikely Power, author John Curtis Perry sheds light on the importance of Singapore as a symbol of courage and strength.

As a long-time student of Pacific Asian civilizations, my interest in Singapore rises out of the distant depths of childhood, as a small boy remembering the pleasing tactile sensation of running my fingers across the satiny wooden surface of a small model boat, lacking its sail but with the stub of a mast. I liked carrying it around and embodied it with people sailing aboard who were, I imagined, somehow secreted in the solid space below the deck. My parents told me it was a prau (proa, prahu), a Malayan boat from the “Far East,” a place vastly remote geographically and in any other way from my hometown of Maplewood, New Jersey. In the 1930s, that town served as a bedroom of New York City, a conventional middle-class suburb, insular in experience and attitude, like much of America in those difficult years. While the Great Depression raged, the grownups tried to hide their anxieties from the children. Bankrupt companies were dismissing their workers. Itinerant homeless men, so-called tramps, often came to the kitchen door asking for a meal. With so many others, including people like us, clinging desperately to economic survival, the world beyond America seemed an alien irrelevance.

“In its wildly implausible story of survival, growth, and prosperity, Singapore exemplifies this great transformation and illustrates the power of the maritime world in making it happen”

Today’s traveler arriving in the city by air sees first a great aggregation of ships laid out in the harbor below, vividly illustrating the city’s primary position among world seaports. In the soft freshness of tropical dawn, driving downtown along a parkway lined with flowering greenery, the many towers of the city gleam in their newness, reminding one how stunningly recent has been the global economic shift from Atlantic primacy to the Pacific as world center of explosive economic growth. In its wildly implausible story of survival, growth, and prosperity, Singapore exemplifies this great transformation and illustrates the power of the maritime world in making it happen. Singapore is a survival tale of overcoming periodic, even life-threatening crises. Highly competent and ambitious leadership, fired by nervous anxiety and committed to success, has provided the program and pulse for what Singapore is today: an economic dynamo, a miracle of well-crafted institutional design achieved with remarkable speed…

Britons can assuage memories of World War II’s catastrophic defeat in Singapore by recognizing the contributions of their imperial rule to independent Singapore’s accomplishments; and although most Americans scarcely know where it is, we have substantial interests in Singapore, both monetary and military. We have twice as much money invested in that tiny place than in all of China. With these heavy corporate stakes, Americans not only have a big economic interest but also, having long ago replaced Britain as guardian of the global seas, we have a strong strategic interest in ensuring open passage through the straits.

Americans can be grateful that Singapore provides a strategic asset to the United States Navy, now that we no longer hold our great base at Subic Bay in the Philippines. Our fleet has found Singapore a receptive host where the largest American aircraft carriers can be accommodated, and where the navy stations several of its new littoral combat ships. Singapore thereby provides support for a forward American naval presence in Southeast Asia no longer available elsewhere. This carries special importance because of our proclaimed “Pivot to Asia.” As nation-states falter in efficiency, Singapore demonstrates that cities may be the salvation of humankind. That this city-state can thrive now leads some to suggest that smallness could even be the wave of the future, that cities as global actors may become more important than nations, at least in some spheres, environmentalism being one example. Cities themselves have traditionally functioned as centers for generating ideas and turning out products. In America, large cities produce the great bulk of the national economy.

“Although no utopia, the achievements of contemporary Singapore are inspiring. We can admire the courage with which it has faced and overcome adversity.”

In May 1995, the then Singaporean minister George Yeo gave a prescient speech in Tokyo talking about the future of cities, suggesting “in the next century, the most relevant unit of economic production, social organization and knowledge generation will be the city or city-region…a little like the situation in Europe before the era of nation-states,” the time, he might have added, when maritime city-states like Venice, Genoa, or Amsterdam conspicuously flourished. Singapore now aggressively markets itself as a global city, aspiring to be more than a regional center for international commerce, perhaps even to become a world maritime capital, “the new London.”

Although no utopia, the achievements of contemporary Singapore are inspiring. We can admire the courage with which it has faced and overcome adversity. Many criticize its authoritarianism yet accept the substantive accomplishments of its leaders in advancing human welfare, opening society to new opportunities and ideas while sheltering it from those perceived as threatening social harmony. But, as in that ancient city-state Athens, the government believes that the good of the community must supersede the interests of the individual. And many outsiders would now agree.

Featured image credit: Untitled by Unsplash. CCO via Pexels.

The post Why we should care about Singapore [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

[image error]

Selected extra-musical benefits of music education for children with autism spectrum disorder

In advocating for music education for children on the autism spectrum it is imperative that teachers recognize the ways in which learning through music helps these students. An overview of extra-musical benefits for music education is provided in three areas: 1. Social Interaction; 2. Sense of Self, and; 3. Psychomotor Facility.

1. Social Interaction

Music education provides students with avenues to interact with others without verbal communication. For example, through music children with autism spectrum disorder follow the leader’s directions by imitating movements that accompany songs: for example, children may engage with a song such as The farmer in the dell by clapping their hands or stomping their feet to the beat of the music. After students are familiar with the song, they may dramatize the story. As students continue to gain experience through music, they display social awareness of cooperative play by singing, dancing, and playing instruments with teachers, educational assistants, and peers. Through continued experiences they are increasingly motivated to interact with others.

2. Sense of Self

Most, if not all, people are capable of self-expression through music. While a child on the autism spectrum may not be able to explain these contributions of music to their quality of life verbally, caregivers may observe increasing self-awareness, self-confidence, and self-esteem in the child’s behaviors. For example, music is known to produce a calming effect on children with autism spectrum disorder (see Eren, Deniz, & Duzkantar, 2013). Over time educators may notice a decrease in stereotypical behaviors such as hand flapping or rocking as students increasingly engage with music.

Successful interactions in music may lead to the child’s growing willingness to control his behaviors in relation to others by listening to and following the leader’s directions. In this case, success leads to success. For example, after a period of struggle, a child with limited speaking ability sings his name. The others in the room cheer this success. The child smiles with pleasure to indicate an emergence of self-esteem as he realizes this success. This may lead to increased self-confidence as his accomplishments in music continue.

3. Psychomotor Facility

Varied experiences in music-based activities provide students with opportunities to develop and practice gross motor skills by moving in place (non-locomotor) and space (locomotor). In addition, while moving through space students provide motor responses to a leader’s directions such as to start or stop, to move quickly or slowly, or to move loudly (large movements) or quietly (small movements). Students engage in musical problem solving when they devise movements to accompany listening experiences. For example, students move like birds to accompany bird-like sounds that the teacher improvises with a piano, recorder, xylophone.

Many children on the autism spectrum experience difficulties with taken-for-granted competencies employed by peers in typical play environments. For example, playing tag or hide-and-seek requires that children are able to move freely through space; play activities, such as throwing a ball, requires that students can control objects through space. Musical games, such as passing a ball to a partner, provide students with opportunities to learn and practice skills that transfer to other contexts. Thus, proficiency in motor tasks increases both the frequency and quality of social interactions for children with autism spectrum disorder (Bhat, Landa, & Galloway, 2011).

Music provides avenues for students with autism spectrum disorder to interact with teachers and peers in spontaneous and creative play. Multiple relationships are established, including those with the music and the physical space within which these activities take place. Interpersonal communications occur among children with autism spectrum disorder, adult guides and other children in the room. Within this context, music education provides students with opportunities to learn and to practice psychomotor skills. Students gain an increased sense of self and of self esteem through these positive interactions with others.

Featured Image Credit: “Music, Hand, Playing Musical Instrument” by James Darlong. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Selected extra-musical benefits of music education for children with autism spectrum disorder appeared first on OUPblog.

March 15, 2017

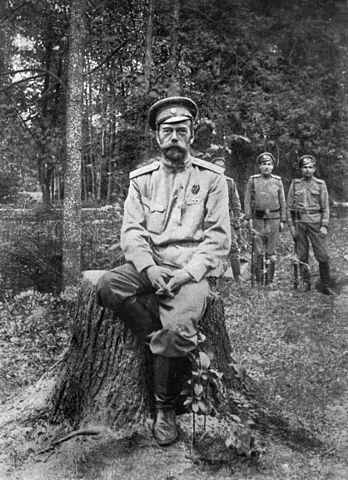

“Freedom! Freedom!”: 100 years since the fall of the Tsar

As midnight approached on 15 March 1917 (2 March on the Russian calendar), Tsar Nicholas II signed his manifesto of abdication, ending centuries of autocratic monarchical rule in Russia. Nicholas accepted the situation with his typical mixture of resignation and faith: “The Lord God saw fit to send down upon Russia a new harsh ordeal…During these decisive days for the life of Russia, We considered it a duty of conscience to facilitate Our people’s close unity…In agreement with the State Duma, We consider it to be for the good to abdicate from the Throne of the Russian State… May the Lord God help Russia.”

When the news broke, masses of people took to the streets to rejoice. The mood had more than a tinge of religious fervor. A newspaper reporter tried to capture this mood:

The dazzling sun appeared. Foul mists were dispersed. Great Russia stirred! The long-suffering people arose. The nightmare yoke fell. Freedom and happiness—forward. “Hurrah! Hurrah! Hurrah!” People look about and gather in large crowds, share impressions of the new and the unexpected. Many embrace, kiss, congratulate one another, and throw themselves greedily at the distributed proclamations. They read loudly, abruptly, agitatedly. From mouth to mouth passes the long-awaited joyous news: “Freedom! Freedom! Freedom!” Tears glisten in the eyes of many. Uncontainable, wild joy.

— The Daily Kopeck Gazette, 6/19 March 1917.

The revolution seemed to be, others wrote, a “miracle,” “resurrection,” “salvation.” These first days of freedom reminded many of “Easter,” the most sacred and joyous holiday. And when actual Easter came in April, people associated this festival of resurrection and promised redemption with Russia’s revolution.

Everyone was talking about “freedom.” It seemed, as the liberal feminist Maria Pokrovskaia wrote on the day after the abdication, that “Russia has suddenly turned a new page in her history and inscribed on it: Freedom!” Looking back across a hundred years, we know that this page, as it were, would be torn out of the book of Russian history or at least overwritten. But a deeper and more revealing story—especially as the world (though Russia least of all) marks this centenary with various projects of remembrance—is less the history of failure and disappointment, though real and important to remember, than the history of how people imagined possibility at that moment, including how they experienced, understood, and embraced this vague and protean word “freedom.”

Photograph of Tsar Nicholas II after his abdication, March 1917. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Photograph of Tsar Nicholas II after his abdication, March 1917. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.For many, it was enough that the Tsar was gone and the new government had declared freedom of the press, speech, assembly, and religion. Vladimir Lenin himself, on returning from exile in April, concluded that Russia was now “the freest of all the belligerent countries in the world.” But many insisted that this negative freedom—freedom from constraints, broken shackles (another common metaphor in the revolution)—was not enough.

First, there was the dark face of liberty: crime and violence unleashed by the collapse of the institutions of police, courts, and prisons but also by the atmosphere of unbridled license, by the widespread attitude of grab what you can while it lasts. Elites on both the left and the right warned that liberty unrestrained by reason or morality was not true freedom but its enemy. At best, this was the confused thinking of “mutinous slaves.” Real freedom, they countered, was inseparable from order, morality, and respect for others.

But there was also, voiced and practiced from below, a positive definition of freedom as active and transforming. In the language of the time, freedom must bring “happiness” and “a new life.” Freedom is incompatible, they declared (and acted on their declarations), with the inequality that kept people hungry and poor and thus unable to enjoy the fruits of liberty. A non-Bolshevik socialist reported how freedom was defined at a mass meeting he attended in May: people who had “only recently been slaves” were dreaming of a world without rich and poor, without human suffering, and without war—naive dreams, in his view, mixed with desires for “harsh and merciless vengeance” against those who stood in the way of these dreams.

Liberal political philosophers would later warn that it was wrong and dangerous to confuse “liberty with her sisters, equality, and fraternity,” to conflate freedom to pursue happiness with freedom that promotes happiness itself by transforming society. But most lower-class Russians would ask what sort of freedom could there be without prosperity for all, peace for all, happiness for all? If they were making a definitional mistake, this mattered little compared to the truth they found in this positive notion of freedom as richer than negative liberty.

A half-century later, the philosopher Hannah Arendt described freedom as a miraculous “new beginning,” as an “infinite improbability” breaking into a world where “the scales are weighted in favor of disaster.” And yet, she insisted, such improbable miracles are real facts throughout history, nurtured by our very nature and experience as human beings. The “unforeseeable and unpredictable” is not the impossible.

The world a century ago was surely tilted into disaster—not only the devastating World War but a long history of popular deprivation and lack of freedom. The events in Russia in early March were embraced as a miraculous “new beginning.” Yes, we know the history that followed. But it would be arrogant to claim we know that this was the only possible outcome. History is not only a story of disappointed hopes (though that is surely a major theme), but also a story of the unexpected and even the infinitely improbable becoming real.

At the very least, the Russian revolution was one of those moments in human history, when people, in the face of darkness and disaster, embrace the possibility of what might be, if for no other reason than it must be. Who are we, knowing only what turned out, to say that their dreams of freedom and a new life were in vain?

Featured image credit: A demonstration of workers from the Putilov plant in Petrograd (modern day St. Petersburg), Russia, during the February Revolution. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post “Freedom! Freedom!”: 100 years since the fall of the Tsar appeared first on OUPblog.

Why bother?

Yes, there is every reason to bother. Read the following: “One of the most common expressions in everyday life, and one which is generally used by all classes, is the expression ‘Don’t bother me!’ and the origin of the word bother has so frequently bothered me that I have spent some time in tracing its etymology. I was surprised to discover that, like a number of other words in our language, bother is a corruption of two words, viz., both ears; the original meaning of the word being ‘Do not annoy me at both ears’—id est, don’t deafen me with your noise.” This note appeared under the signature Scio in a popular Manchester journal in 1884. Who enlightened Mr. Scio after he “spent some time in tracing the origin” of the troublesome word, used by all classes? And where did he find such nonsense? By 1884 many dictionaries had been published, including Skeat’s, to say nothing of other works educated people used (Johnson and Webster among others). No one suggested anything like bother = both ears, but the motif of deafening will reemerge later in our story.

Even one of such ears is a great bother, to say nothing of both.

Even one of such ears is a great bother, to say nothing of both.Bother is a late eighteenth-century addition to the vocabulary of English. It first surfaced in Anglo-Irish authors: Sheridan, Swift, and Sterne. Even later it was known so little that most dictionaries compiled in the first quarter of the nineteenth century did not include it, while those few that did called it slang. Three schools exist: according to one, the etymology of bother is unknown or uncertain (the latter is a genteelism for “unknown”); another school derives it directly from Irish; the third connects it with Engl. pother, though it admits that bother might be the Irish pronunciation of pother or at least influenced by pother. The first school has a noticeable advantage over the other two, but we will still have a look at the unsafe conjectures, before we flee from the battlefield.

To begin with, we may ask: “What is pother?” It means “choking smoke or dusty atmosphere; fuss, commotion.” If I am not mistaken, the first sense is “literary” and so archaic that hardly anyone remembers it. Pother appeared in English in the sixteenth century. At that time, it rhymed with mother, other, and the like. And the like is a tiny group. Mother, other, and brother have their present day root vowel from ō (long o), but a reconstructed form like *pōther leads nowhere (in historical studies, an asterisk before a form means that it has not been found in texts). That is what one can read in The Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (ODEE).

With regard to words like mother, other, and brother, I can think only of smother that rhymes with them. It goes back to smorðer, later smoþer (ð = th in Modern Engl. this, and þ = th in Modern Engl. thin). As far as we can judge, the loss of r did not affect the pronunciation of o before it. Consequently, the vowel in pother did not have to go back to long o: there could have been other scenarios. Unfortunately, the word’s history has not been discovered (however, see below). The ODEE says: “…no source is known; perhaps influenced by bother.” Thus, bother was possibly influenced by pother, and pother by bother. It is no wonder that few people are happy about this etymology. Words for “suffocating smoke” are often troublesome: see the post on qualm (August 13, 2014).

Skeat did risk offering a conjecture about the origin of pother. In his opinion, pother is the same word as podder, from pudder, which is a variant of the verb potter. Putter (around), potter (about), pudder, and podder are indeed variants of the same verb. In addition, we find Scots put or putt “to shove, throw, hurl,” familiar from golf, where putter is both a club and a person who putts. Finally, put ~ putt may be the same verb as Engl. put (in put in, put off, and so forth), even though one rhymes with shut and the other with soot. Apparently, pother can be related to that group if its sense “confusion” (“pottering about”) is primary and “choking smoke” secondary. But this is unlikely: the concrete sense (“smoke”) must have preceded the derivative one (again compare the history of qualm). Therefore, I think Skeat did not guess well. The origin of pother remains unknown and, for this reason, can tell us nothing about bother, another word whose history is obscure. The difference between dd to ð (podder versus pother) is not a problem: the two sounds often alternate before r, and there are certain regularities in the development of this group: compare father (from fæder) and udder, from ūder). Swift also used the form bodder, and note how Sam Weller pronounced farthing at the beginning of the previous post.

Jonathan Swift did not like to be boddered.

Jonathan Swift did not like to be boddered.We are now coming to the hypothesis that bother is a direct borrowing from Irish. Since the first authors to use bother were from Ireland, this hypothesis looks reasonable. The Irish words cited in connection with bother are buaidhrim “I vex” and the like. Since one of them means “deaf,” it is often said that the original sense of the alleged Irish source of Engl. bother and of Engl. bother was not just “vex,” but “to deafen, bewilder with noise.” I am not sure that this premise is so obvious. The sentences are: “With the din of which tube my head you so bother” and “Lord, I was boddererd t’other day with that prating fool Tom.” Two citations do not go far, the similarity of the contexts could be due to a coincidence, and the gloss “irritate, vex, bewilder” (without reference to noise) suits both situations, especially the second, to a T. I would prefer to stay away from “noise” and “deaf(en)” as the semantic nucleus of bother.

However, the greatest stumbling block in this reconstruction, which “bothered” all serious etymologists from the start, is the fact that buaidhrim and several related Irish words are not pronounced according to the image their spelling evokes: dh is mute, and one hears only a diphthong before r. The disappearance of any semblance of th in them goes back to the thirteenth century, while bother surfaced in English about five hundred years later. The distinguished scholar Alan J. Bliss made a heroic effort to prove that this chronological gap in Anglo-Irish can be explained away. Those who are interested in the technicalities are welcome to read his articles in Notes and Queries for 1968 (pp. 285-286) and for 1978 (pp. 539-540). I am not sure Bliss succeeded in deriving bother directly from some Irish word, but this is of course a matter of opinion.

Yet, as has been noted, since bother turned up first in the works of Irish authors, it may indeed have an Irish etymology, especially because no other source has been found. So those who disagree with Bliss suggested that bother is Irish pother “confusion” (whatever the origin of pother), pronounced with b instead of p. It is also a shaky etymology but perhaps a tiny bit more convincing than the one Bliss defended. Bother may have appeared in English as a noun (“vexation,” “confusion”). Today we have a noun (too much bother, I don’t want to put you to such bother) and a verb (don’t bother me).

This is both a pother and a bother.

This is both a pother and a bother.Thus, the origin of bother remains half-solved at best. Some of our recent dictionaries hesitatingly repeat Bliss’s etymology (which, incidentally, was flaunted as indubitable in the same periodical Notes and Queries as early as 1875), others say nothing, and still others stick to the pother/ bother idea. Bother was slang, apparently, Anglo-Irish slang, “a low word,” as Samuel Johnson would have called it (in his 1775 dictionary, he passed it over; nor was it mentioned in the multi-volume revision by Henry Todd, 1818). In dealing with slang, one has to be especially careful. The less dogmatic one is in handling such material, the better, but being sent way with the verdict “origin unknown” is unjust and bothersome.

Image credits: (1) Elephant by Benjamin Vaughn, Public Domain via Pixabay (2) “Jonathan Swift” by Francis Bindon, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) Ashes eruption by Pexels, Public Domain via Pixabay. Featured image credit: “1771 Bonne Map of Ireland” by Rigobert Bonne, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Why bother? appeared first on OUPblog.

The life of Saint Patrick [part one]

Saint Patrick’s Day is a religious festival held on the traditional death date of Saint Patrick. Largely modernized and often viewed as a cultural celebration, Saint Patrick’s Day is recognized in more countries than any other national festival. His association with Christianity and Irish nationalism have allowed Saint Patrick to remain a cultural figure today.

To celebrate, we’ve pulled a two-part excerpt from Celtic Mythology: Tales of Gods, Goddesses, and Heroes, in which Philip Freeman tells the story of Saint Patrick. It is a tale of courage, survival, and deep faith. Remember to check back on 17 March for the second part of “The Life of Saint Patrick.”

Patrick was born in Britain, across the sea from the shores of Ireland. When he was 16 years old, he was kidnapped from his family’s villa by Irish pirates and taken to Ireland to be sold as a slave. He was bought by a druid named Miliucc and set to work tending his sheep in hunger, cold, and rain. When he had nowhere else to turn, he found again his childhood faith and the spirit burned inside him. He prayed a hundred times each day and the same again each night asking God to save him.

One night after six years of captivity, Patrick heard a voice telling him to flee from his master and make his way to a ship that was waiting for him. Patrick listened to the voice and ran away. They sailed for three days and three nights on the sea and landed in a wilderness with nothing to eat or drink. Like the children of Israel, Patrick and the crew wandered through the deserted land. Finally Patrick prayed to God for deliverance—and the Lord heard his prayer. A herd of wild pigs came near them and the crew killed and ate them.

Patrick returned at last to his family in Britain and was received with joy. While he was back in his home, he had many visions telling him to return to Ireland and preach the gospel. Thus he determined to train as a priest and return to the land where he had been enslaved.

Now at this time in Ireland a great and mighty pagan king named Lóegaire ruled at Tara. He surrounded himself with druids and sorcerers who were masters of every sort of evil. There were two druids among his counselors named Lochru and Lucet Máel who were able to see the future by the dark arts of the devil. They had predicted to the king that one day a man would arrive from across the sea who would destroy his kingdom and the gods themselves if he allowed it. Many times they proclaimed:

There will come a man with a shaved head

And a stick curved at the top.

He will chant evil words

From a table at the front of his house.

And his people will say: “Amen, let it be so.”

Slemish, County Antrim where St Patrick is reputed to have shepherded as a slave. “Slemish mountain County Antrim” by Man vyi. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Slemish, County Antrim where St Patrick is reputed to have shepherded as a slave. “Slemish mountain County Antrim” by Man vyi. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.This Lóegaire was ruling at Tara as king when Patrick arrived on the shore of Ireland at Inber Dee in Leinster. He then sailed north along the coast to Inber Sláne near the Boyne River and hid his boat there. He wanted to find his former master Miliucc and buy his freedom, for under Irish law he was still a slave.

A swine-herd found Patrick and his men near their boat and went to tell his master Díchu. This man thought they were thieves or pirates and set out to kill them, but he was a man of natural goodness and the Lord turned his heart when he saw Patrick. The new bishop of Ireland preached to Díchu and won him to the faith, the first of his many converts in Ireland.

Patrick then travelled across the land to the mountain of Slíab Míss where he had once been a slave. But when Miliucc heard that Patrick was on his way, he was prompted by the devil to kill himself lest he be ruled over by a man who had once served him. Miliucc gathered together all his possessions in his house and set the structure on fire with himself inside.

Patrick saw the smoke in the distance and knew what Miliucc had done. He stood there for hours watching in silence while he wept…Patrick left the lands of Miliucc and traveled around the nearby plain preaching the gospel. It was there the faith began to grow.

Now at that time Easter was drawing near and Patrick talked with his companions about where they might celebrate the holy festival in that land for the first time. He decide at last that they should celebrate Easter in the plain of Brega near Tara, for this place was the center of paganism and idolatry in Ireland.

At the same time the heathens of the island were celebrating their own pagan festival with incantations, demonic rites, and idolatrous superstitions. Nobles and druids of the land had gathered at Tara to light a sacred fire. For it was an unbreakable law that no one could kindle a fire before the king had lit the holy fire on that night. But that evening Patrick kindled his fire before the king in full view of the hill of Tara. The king called his druids together and demanded to know who had lit a fire before him. He ordered that the man be hunted down and killed at once. The druids declared that they did not know whose fire it was, but they warned the king that unless he extinguished the fire that very night that it would grow and outshine all the fires of Ireland, driving away the gods of the land and seducing all the people of his realm forever.

When Lóegaire heard these things he was greatly troubled and all of Tara with him. He declared that he would find the man responsible for the forbidden fire and slay him. He ordered his warriors to prepare their chariots for battle and follow him out of his fortress.

They found Patrick nearby and summoned him before the king. His chief druid Lochru mocked the holy man and the faith he taught, but Patrick looked him in the eye and prayed to heaven that he might pay for his impiety. The druid was then lifted up into the air and cast down on a rock, splitting his skull into pieces.

The pagans were all angry and afraid, so that the king ordered his men to seize Patrick. But darkness suddenly fell on them all and an earthquake struck the warriors. The horses were driven into the plain and all the men died except for the king, his wife, and two of his men.

“I beseech you,” said the queen to Patrick, “do not kill my husband. He will fall before you on bended knee.”

Lóegaire was furious and still planned to kill Patrick, but he knelt before him to save his life. Patrick however knew what was in the heart of Lóegaire. Before he could gather more warriors, he turned himself into deer and went into the forest. The king then returned to Tara with his few followers who had survived.

The next day King Lóegaire and his men were in his feasting hall at Tara brooding about what had happened the evening before. Suddenly holy Patrick and his followers appeared in the midst of them even though the doors were closed. The king and his men were astonished. Lóegaire invited Patrick to sit and eat with them so that he might test him. Patrick, knowing what was about to happen, did not refuse.

Stained glass window in Carlow Cathedral of the Assumption showing St Patrick Preaching to the Kings by Andreas F. Borchert. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Stained glass window in Carlow Cathedral of the Assumption showing St Patrick Preaching to the Kings by Andreas F. Borchert. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.While they were eating, the druid Lucet Máel placed a drop of poison in Patrick’s cup while the holy man’s eyes were turned. Patrick took the cup and blessed it, so that the liquid froze like ice. He then turned the cup upside down and the drop of poison fell out. Patrick blessed the cup again and the wine turned to liquid once more.

After dinner, the druid challenged Patrick to a duel of miracles on the plain before Tara.

“What kind of miracle would you like me to do?” asked Patrick.

“Let us call down snow on the land,” the sorcerer replied.

“I do not wish to do anything contrary to God and nature,” said Patrick.

“You are afraid you will fail,” exclaimed Lucet Máel. “But I can do it.”

The druid uttered magic spells and called down snow from the sky so that it covered the whole plain up to the depth of a man’s waist.

“We have seen what harm you can do,” said Patrick. “Now make the snow disappear.”

“I do not have the power to remove it until tomorrow,” said Lucet Máel.

Patrick then raised his hands and blessed the whole plain so that the snow disappeared in an instant.

The crowd was amazed and cheered for the holy man. But the druids were very angry.

Next the druid invoked his evil gods and called down darkness on the whole land. The people were frightened and begged him to bring back the light, but he could not. But Patrick prayed to God and straightaway the sun shone forth and all the people shouted with joy.

Featured image credit: “Tourmakeady” by Christian_Birkholz. CCO Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The life of Saint Patrick [part one] appeared first on OUPblog.

Why social work is essential

March is Social Work Month in the United States. Social workers stand up every day for human rights and social justice to help strengthen our communities. They can be the voice for people who aren’t being heard, and they tackle serious social issues in order to “forge solutions that help people reach their full potential and make our nation a better place to live.” There are over 600,000 social workers in the US alone, yet all too often their work goes unnoticed in society. To better articulate why social work is so important, we interviewed some social workers who have dedicated their lives to practice and research in the field. Their thoughts and experiences make it clear why social work is so critical to society.

* * * * *

Thoughts on passion in the field of social work

“Social work helps the arc of the moral universe bend toward justice, to paraphrase the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.”

—Miriam Potocky, a specialist on refugees, human rights, and international social work

“I believe that there is always hope even in times of despair. I have witnessed people experiencing darkness that seems inescapable and I have seen these persons find hope in the hope of others. As I have often stated to a few clients—’I will hold the hope for you even when you cannot.’ This leads me to believe that support is key to making a huge difference in someone’s life. I also believe that people can change, and that as social workers we often are in the position to guide and to facilitate these changes in someone’s life, when they are ready to undertake this work. I hold the conversations, narratives, and stories of those in need as sacred and precious. I remind myself that of all the people in the world they could be sharing this story with, that I have the honor of bearing witness to their experiences, and I am humbled by these opportunities. These beliefs keep me going, feed my soul, and contribute significantly to my passion about social work.”

—Sandra A. López, a key leader in calling attention to the essential practice of self-care within the profession of social work

“My passion for the field of social work emanates from the desire to advocate for others that may need a voice within society. I believe strongly that it is our profession’s role to promote social justice for all marginalized populations and groups, as well as it is our responsibility to teach generations of social work students, practitioners, and researchers to do the same. This passion to advocate for others has become infinitely clear to me in my practice efforts over the years whether working with the HIV/AIDS community, LGBTQ youth, older adults, or the disability community, among many others. In the same regard, with the recent increase of hate speech and incidents related to xenophobia, racism, and anti-Semitism, my passion for the field of social work has been further confirmed and is often reignited.”

—Michael P. Dentato, author of “Queer Communities (Competency and Positionality)” in the Encyclopedia of Social Work.

Pieta House by Joe Houghton. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

Pieta House by Joe Houghton. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.* * * * *

The important roles of social workers

“We are champions of human rights and social justice.”

—Miriam Potocky

“Social work is a profession that is quite broad, diverse, and offers a variety of settings, roles, and services to those who share one common value of helping those in need. As biased as this may sound, I really don’t know of any other profession that is as involved in addressing the needs of human beings, across the life cycle, and in so many diverse ways. From birth to death, social workers are there to provide the critical support one may need at any moment in time. In addition, we play so many roles; from therapist or clinician, to administrator, to policymaker across settings like healthcare, schools, community centers, juvenile probation, hospice, behavioral health, and early childhood development to name a few. Although our roles and settings may be different, the cardinal values of social work bring us together in a powerful fashion.”

—Sandra A. López

* * * * *

Common myths and misconceptions about social work

“Some common myths and misconceptions about social work and social workers pertain to minimizing the vital role that we play, and the impact that we can have serving diverse populations within various settings. As a huge fan of promoting interprofessional practice, I often tell my students it is important to integrate themselves into teams in which social workers are vitally needed, and to ensure our voice is always ‘at the table’ all the time as we are trained in a much different way than others across the health and social sciences. Such training points to the manner in which we use a person-in-environment perspective during assessments and interventions to determine the most affirming and/or evidence based model(s), appropriate theory or theories, and level of care to best meet the needs of our clients at all times.”

—Michael P. Dentato

* * * * *

Why is social work still important?

“I often wish people would ask me why the field of social work remains so important today. My response would be that the field of social work is vitally important today more so than ever, as we continue to promote a person-centered, empowering approach to our practice at all times, as well as we compliment and strengthen the roles of others across diverse professions. Lastly, that our history provides evidence of the critical ongoing need for social workers to advocate and lend a voice for all marginalized and oppressed groups.”

—Michael P. Dentato

“Why do you keep trying to learn and make a difference? A rolling stone gathers no moss.”

—Rosalyn M. Bertram, a lead researcher for several national initiatives engaged in systems transformation.

* * * * *

Featured image credit: teamwork co-workers office by pmbbun. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Why social work is essential appeared first on OUPblog.

Sui Sin Far’s “The Land of the Free” in the era of Trump

Facing President Trump’s controversial travel ban, hastily issued on 27 January and revised on 6 March, that temporarily halted immigrants from six Muslim majority countries, I was wondering what Sui Sin Far (Edith Eaton), a mixed-race Asian North American writer at the turn of the twentieth century, would say about the issue. She probably would point out how the travel ban appealed to a similar rhetoric of difference that justified the exclusion of Chinese immigrants in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

At the peak of anti-Chinese sentiment in the second half of the nineteenth century, the rhetoric of difference conceptualizing the Chinese was popular in public speeches, political cartoons, state and Congressional hearings and debates, journalistic reports, literary work, and legal documents, contributing predominantly to contemporary’s racial knowledge of the Chinese. Chinese immigrants were represented as yellow peril, slaves, barbarous, canny, heathen, immoral, inferior, a threat to white workers and to stability of family structure, and hence ineligible for naturalization and justifiably excludible. The policing of the body of Chinese immigrants reflected the exercises of economic, political, and legal apparatus. For example, the Foreign Miners’ Tax of 1850 and 1852 and the Chinese Police Tax of 1862 used financial incentives to restrict Chinese immigrants. Two California state laws, the Anti-Kidnapping Act of 1870 and the Anti-Coolie Act of 1870, portrayed Chinese and Japanese women as presumptive “lewd and debauched” and Chinese immigrants as “criminal and malefactors,” consequently leading to later federal legislations: the Page Law of 1875 that literally banned Chinese and Japanese women and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 that effectively halted Chinese immigration for ten years and prohibited Chinese from becoming US citizens.

Sui Sin Far would tell us that we are repeating history. What was said about the Chinese is conveniently applicable to, with slight alterations, other “undesirable” immigrants: the Japanese, the Asian immigrants, the Jewish, the East European immigrants, the Mexican, the refugees, and now immigrants practicing different beliefs.

The eldest daughter of an English father and a Chinese mother, Sui Sin Far lived in Britain, the United States, Canada, and the Caribbean, exposed to and influenced by her cosmopolitan experiences. Subject to racial gaze herself and witnessing injustice done to the Chinese, Sui Sin Far decided early to redress the distorted image of the Chinese in her journalistic writing and literary work. She created vividly a wide range of fictive characters, from Chinese merchants, their wives, maids, servants, laborers, to American feminists and citizens who were capable of judgment and feelings in her short stories, most of which were collected in Mrs Spring Fragrance in 1912. She was especially concerned about the impact of immigration regulations and restrictions on families. One of her short stories entitled “In the Land of the Free” resonates with the fate of some immigrant families and travelers affected by the executive order of 13769.

Editorial cartoon from 1912 Puck magazine. L. M. Glackens, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Editorial cartoon from 1912 Puck magazine. L. M. Glackens, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Set up in the exclusion era of 1900s, the story opens with a scene of family reunion in the San Francisco port. Lae Choo, who went back to China to give birth to their baby there at her husband’s suggestion, returns to the United States with their two-year-old boy, the Little One. Hom Hing is excited to meet his son for the first time. The customs officers, however, do not allow the boy to go ashore because he does not have a certificate. Hing explains that when the travel documents were issued the baby was not born yet. He protests, “But he is my son.” The officers shrug their shoulders, “We have no proof, and even if so we cannot let him pass without orders from the Government.” The child is thus taken away from his parents and sent to a missionary school, while the parents have to go through an unexpected, expensive ten-month struggle to get an important piece of paper from Washington to restore their son. When Lae Choo is finally allowed to reclaim her son after a complicated legal process, she opens her arms in anticipation and cries, “Little One, ah, my Little One!” However, the boy, now renamed as “little Kim” by the missionary woman, avoids his mother and hides behind the women’s skirt. The story ends with the boy’s biding his mother to leave, “Go’way, go’way!” (101) In the end, the land of the free that the mother eagerly points to the Little One at the beginning of the short story turns out to be a land of suffering and separation. The reformation of “little Kim” was the inevitable outcome of “purging” undesirable elements of immigrants. However, no matter how fluent his English might be or how upright a citizen he would become (if he was allowed to be naturalized), the Little One/little Kim could hardly escape the fate of his parents if racism and hate crimes were normalized or even legalized. The internment of Japanese Americans during the World War II was but another example of demonizing and racializing immigrants and Americans of Japanese descent.

Of course, an identical scene depicted “In the Land of the Free” rarely happened in the airports; nevertheless, the Department of Homeland Security’s proposal to separate children from their parents caught crossing borders indicates that such a scene of horror and separation will soon reappear. It is not coincidental that the executive order, reflecting the same rhetoric of exclusion that banned Chinese immigrants and incarcerated Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans, depicts immigrants and refugees as dangerous and “terrorists,” dehumanizing them and reducing them to a few negative labels. On 6 February, the Association for Asian American Studies, among other organizations and groups, called out the nature of the travel ban:

The order, notwithstanding declarations otherwise, is guided by, and more importantly furthers, an overt anti-refugee, anti-Muslim, and anti-immigrant agenda. Such an agenda is bigoted in scope, Islamophobic in nature, and—as Asian American history has repeatedly shown—represents a “dark moment for the nation.”

— AAAS Statement Regarding the Executive Order

In a dark moment like this, how do we keep the promise that this land is your land and my land, made for you and me?

I believe, at the time of the 152nd anniversary of Sui Sin Far’s birth this March, her advice in an earlier 1896 article, “A Plea for the Chinaman” (we could replace the subject with many other words, such as immigrants and refugees ) rings particularly true:

Human nature is the same all the world over, and the Chinaman is as much a human being as those who now presume to judge him; and if he is a human being, he must be treated like one…We should be broad-minded. What does it matter whether a man be a Chinaman, an Irishman, and Englishman, or an American. Individuality is more than nationality.

Featured image credit: Japanese-Americans in 1942 boarding a train to an internment camp. Russell Lee, Library of Congress, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Sui Sin Far’s “The Land of the Free” in the era of Trump appeared first on OUPblog.

Can art save us from fundamentalism?

London, rain, and Rothko—each was foreign to the missionary encampment on the Navajo reservation where Jakob grew up, in the 1980s. Back then, he seized every opportunity to share the gospel with his Native American friends, even as they played endless games of cowboys and Indians in the deserts of Arizona: “The Navajo kids always wanted to be the cowboys, because the cowboys always win, they said.” Into his early twenties, Jakob assumed that he would follow in the footsteps of his Pentecostal parents, attend Bible school, and enter into full-time ministry. He nearly did. “But then, one day” he tells me,

“I came into a room that was dimly lit. The space had the feel of a small chapel. [. . .] Tall dark paintings stretched from floor to ceiling. I sat with them for hours, soaking in the lines and colors, venturing into the empty spaces, and the spaces beyond them… I’d later learn that Mark Rothko said, ‘those who weep before my paintings are having the same religious experience that I had in painting them.’ That’s what was happening to me, and it was like no religious experience I’d had before. I can say with confidence, looking back 20 years later, there never would have been an undoing of my conservative evangelical worldview without this encounter with the transcendent work of Rothko on that rainy afternoon in London’s Tate Modern. Indeed, if it weren’t for the arts—Rothko, Bob Dylan, Hemingway, Kerouac, to name a few—I am not sure there would have been an unsettling of my religious certainties. Sometimes gradually and sometimes with immediate effect, aesthetic experiences burst the evangelical Christian bubble that was my world.”

Each line in this brief account is fascinating and instructive. But I want to focus on Jakob’s phrase, “aesthetic experiences burst the evangelical Christian bubble.” Whether he knew it or not, Jakob was restating a concept that it is ubiquitous in modern aesthetic theory. Philosophers from Kant and Schiller to Adorno and Zizek have waxed persuasive about art’s unique ability to unsettle and rework our most deeply rooted concepts, categories, and presuppositions. It was exactly this theory—of art’s disruptive capacities—that inspired me to track down hundreds of former evangelicals who, like Jakob, had left the fold through the intervention of the arts.

Tate Modern, London, 2001, by Hans Peter Schaefer CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Tate Modern, London, 2001, by Hans Peter Schaefer CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia CommonsI began this ethnographic project as a doctoral student at Harvard Divinity School, where I had undertaken a course of study in religion and the arts. As I immersed myself in modern aesthetic theory I became aware of an almost obsessive fascination with art’s disruptive capacities. If philosophers in previous eras have waxed poetic about the soothing and elevating qualities of the beautiful, the modern aesthetic theorist tends to emphasize art’s capacity to destabilize our certainties and disfigure our selves. With due respect to the philosophers, I wanted to test for myself the limits of these claims through ethnographic study: would the theory hold up to the lived experience of actual human beings? Could art disrupt the beliefs and practices of, for example, people who had been steeped—for a lifetime—in a particular religious community? What about a person who had been raised in the more conservative strains of 20th Century American evangelicalism? Could art disrupt even that?

Formulating the general idea for the study was easy enough, but how would I actually find these former evangelicals? I landed upon two extraordinary field sites. The first is The Oregon Extension, a semester study-away program in the southern Oregon Cascades, which was founded in 1975 by a small crew of renegade professors from evangelical Trinity College in Illinois. Each fall semester this small school draws between twenty-five and forty students from conservative evangelical Christian colleges and challenges them—through fiction and poetry—to ask difficult questions of their faith. Many Oregon Extension alumni look back on their time in the program (even 20 years later) as the moment in which they disavowed the “fundamentalist side of evangelical Christianity,” as one alumnus puts it. The arts are often at the very center of the stories they tell.

My second field site is the Bob Jones University School of Fine Arts. This dynamic art school, founded in 1947, is housed at the self-described “fundamentalist” Christian university in Greenville, South Carolina. It has the largest faculty of any of the University’s schools, and it is famed for its world-class Shakespeare productions, operas, museums, and galleries. For many Bob Jones students and alumni, the arts go hand in hand with their faith, even if certain aesthetic experiences challenge them to revise aspects of their religious heritage. As one devout alumnus and now faculty member of the School of Fine Arts recalls: “The arts at Bob Jones were a key part of my break with the fundamentalism of my upbringing… Hamlet, Goethe’s Faust, and many more… deepened and enriched my evangelical faith.” But for other Bob Jones alumnae, an anguish of irreconcilability between Bob Jones–style religion and the experience of certain aesthetic masterworks sent fissures through their evangelical identity—sometimes a wrecking ball.

Hundreds of alumni from the Oregon Extension and the Bob Jones School of Fine Arts agreed to participate in my study; almost one hundred of them wrote memoirs for the project and underwent a series of interviews with me. As I got deep into the weeds of their experience, I found some answers to my questions about the extent of art’s unsettling effects on deeply ingrained religious belief. Virtually every participant in the study provided vivid examples of the ways that art unsettled at least two particular aspects of what they call “a fundamentalist mindset”:

1) Art unsettled their felt need for “absolute certainty” in matters of religious belief.

Holly S., for example, contributed a detailed account of the process by which she went from being a 20 year old street evangelist—who preached about the love of God and fires of Hell without a flicker of doubt in her mind—to being a post-Christian artist. Right after her twenty-first birthday, a professor at the Oregon Extension put a thick book of Russian fiction in her hand. “The characters in The Brothers Karamazov began to feel like family to me,” she recounts, “and the doubts of Ivan Karamazov slowly saturated my soul.”

2) Art unsettled their hardline of division between insiders and outsiders, between “real” (evangelical) Christians and non-Christians.

Barry S., for example, provided a stirring account of how the films of David Lynch, Krzysztof Kieslowski, and Ingmar Bergman “made me tremble with recognition that the full range of human needs, wants, fears, and longings were as intimately woven into my being as they were into anyone else’s—Christian or non-Christian. I could no longer deny it. And I didn’t want to.” The stony wall of division between himself and all nonevangelicals “came tumbling down.”

I’ve given you just a few real life examples here, but I could have given you hundreds. The modern aesthetics theorists were clearly on to something. Of course we need to steer clear of claims that modern aesthetic experience has universalizable effect. So much depends on context and reception. And yet the accounts of the men and women in my study lay bare the staggering power of the arts to unsettle and rework deeply ingrained beliefs and practices.

As much as my ethnographic work has convinced me of the great extent of art’s disruptive capacities, they have also taught me something else about art. The very same post-evangelicals who emphasize the unsettling effects of aesthetic experience will often describe the arts as a source of great “comfort.” The arts, they say, lent a comforting and pliable form to the perceived formlessness of belief and identity that accompanied their initial forays out of evangelicalism and into the disquieting realms of questions and doubts. The arts, they suggest, become a different way of knowing and unknowing that generated and intensified the experience of uncertainty, while rendering it habitable by increasing their capacity to dwell in mystery and half-knowledge.

If this is true for these former evangelicals, it may be true for any one of us human beings. The participants in this study have thus taught me to keep my eyes pealed for the many ways that the arts save each of us—each and everyday—from what these Oregon Extension and Bob Jones alumni refer to as a “fundamentalist mindset”—religious or otherwise. In this sense, yes, art can save us from fundamentalism.

Featured image credit: The Starry Night by Vincent Van Gogh. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Can art save us from fundamentalism? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers