Oxford University Press's Blog, page 394

March 10, 2017

The role of the death-mother in film

Hitchcock’s famous Psycho (1960) has an enduring legacy in the slasher-horror genre. Its impact on this genre is an enduring one, as suggested by the A&E series Bates Motel, culminating with Rihanna cast in Janet Leigh’s indelible role. Perhaps its most striking contribution, however, is its thematization of a figure I call the death-mother. This figure emerges from the diegetic world of the film, but exceeds it; she is born from abstraction, remoteness, distance. She emerges from the fusion of narrative concerns, embodied by the mysterious unseen persona of Mrs. Bates/Mother, and the heightened aesthetics of the genre artist.

Psycho expands on a work that anticipates some of its central themes of an overpowering female presence. Currently revisited in a revival of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s musical starring Glenn Close, Billy Wilder’s great 1950 film Sunset Boulevard charts the comeback of the fictional silent movie star Norma Desmond, played by the real silent movie star Gloria Swanson. Wilder’s movie, which he co-wrote with Charles Brackett, explores the tortured relationship between Norma, who verges on the brink of madness, and a down-on-his-luck screenwriter, Joe Gillis (William Holden), whom she hires to polish up her comeback vehicle (she has written a screenplay that defies logic).

Glenn Close as Norma Desmond in the current revival of the musical version of Sunset Boulevard. By Angelalitt CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Glenn Close as Norma Desmond in the current revival of the musical version of Sunset Boulevard. By Angelalitt CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The film famously begins with a shot of a man, who turns out to be Joe, floating dead in a swimming pool. He narrates the film in voice-over, in good film noir fashion, albeit from the dead. Joe floating in the pool: this shot returns the male subject, horrifyingly, to the womb and origins. Much of the film proceeds from this basis. Norma, in fierce, Kabuki-like make-up and dress that exaggerate her femininity and suggest a drag performance, alternately seduces and repels Joe.

There is an especially chilling, femme fatale moment in which Joe, comforting Norma after a suicide attempt, falls into her outstretched arms. Norma, a death’s-head smile on her face, enfolds Joe into her bosom, a fusion of the femme fatale and the mother of death. This moment anticipates the scene in which Norma literally kills Joe, shooting him and leaving him floating dead in her vast swimming pool, a grotesquely reabsorbed fetus.

What links Sunset Boulevard to Psycho are the associations of Norma and death and the level of aesthetic sublimity they achieve by the end of the film. Having fallen off the brink of sanity and become truly mad, Norma stands at the top of her decaying mansion’s long central staircase, believing, in her madness, that the television crews and the gossip columnist Hedda Hopper (playing herself), assembled at Norma’s home to document her arrest for murder, are all there to herald her triumphant comeback. “Max,” the cryptic, bald servant who looks after “Madame,” and is in actuality her former husband and film director (played by the real-life film director Erich von Stroheim), “directs” this scene of Norma descending the stairs.

As Norma descends the stairs, grandiose and melodramatic music (by Franz Waxman, who scored several Hitchcock films, most notably Rebecca, another film about an overpowering female presence) harrowingly ironizes Norma’s “big moment,” as she regally proceeds towards the cameras, gives a speech thanking all of those “wonderful people out there in the dark,” and says, to the director she once worked with and hopes will direct her comeback, “Mr. De Mille, I am ready for my close-up!”

Norma’s big moment. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Norma’s big moment. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Two key aspects of the representation relate to the death-mother. As Norma, with antic, intensifying theatrical energy, makes her way down the stairs, the various reporters assembled, at different points, on the staircase stand stock still. This creates an exquisite tableau of life-in-deathness, which informs several Hitchcock films. It is as if Norma had entered the world of the dead, or re-entered the world while herself being dead, Hollywood as a carnival of souls.

Then, once Norma announces her readiness for her close-up, the music rises up again. As Norma, again with theatrical fervor, undulates toward the camera, something strange occurs. Or, to put it another way, an aesthetic choice is made. Her face does not come into greater definition (close-ups being crucial to this film, in which Norma says of her silent movie era, “We didn’t need voices then—we had faces.”) Rather, her image recedes into a misty, evanescent, smoky obscurity, and with it representation itself.

Both Wilder and Hitchcock find recourse in Surrealistic film technique, in which the film medium itself—the image itself—undergoes a profound distortion. The death-mother emerges from the concatenation of multiple effects—consistent motifs, associations, et al.—that then recombine in order to produce the effect, through an intense stylization and a series of concomitant aesthetic choices, that we have entered the world of death, one that is tinged with and indissociable from images and associations with the mother, grotesquely inverted as the mother who brings forth death, not life. Such occurs at the climax of Psycho, when the Mother’s skull-face is superimposed over Norman Bates’ face, and this image dissolves into one of a car being dragged out by a metal chain from a swamp.

Norman’s face fuses with Mother’s. Fair use via Blogspot.

Norman’s face fuses with Mother’s. Fair use via Blogspot.Psycho and Sunset Boulevard both reveal that a particular relationship exists between works that seek to thematize the terrors of gendered identity and sexual desire, specifically the relationship to the mother’s body and female sexuality, while also seeking an especially calibrated, considered aesthetic effect. The death-mother may suggest a great deal about the dread of the mother in culture and the misogynistic dimensions of this dread. Perhaps as resonantly, it reveals, as a fantasy but also an aesthetic preoccupation, that a profound and troubling linkage exists between the dread of a death-associated femininity and the zeal to create dazzling art.

Featured image credit: Norman Bates house from Pyscho. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The role of the death-mother in film appeared first on OUPblog.

To understand the evolution of the economy, track its DNA

How much would we understand about human evolution if we had never discovered genetics or DNA? How would we track the development of the human species without taking into account the universal code of life? Yes, we could study ancient trash heaps to estimate people’s average caloric intake over time. Or we might seek clues in burial mounds regarding population growth rates and changes in our physical characteristics over time. But without access to the fundamental unit of analysis of human evolution, our understanding would be fragmentary and incomplete at best.

Such is the plight of the social scientist seeking to understand the past, present, and likely future of the economy without an appreciation of code. Code is the DNA of economy. It is how ideas become things. The evolution of code is the story of the progress of human society from simplicity to complexity over the period of millennia. We can track GDP over time or measure employment rates. But without access to the fundamental unit of analysis of economic evolution, our understanding would be fragmentary and incomplete at best.

If you hear the word “code” you’re likely to think of computer code. That is one form. But consider the word code more broadly. The word “code” derives from the Latin codex, meaning “a system of laws.” Today code is used in various distinct contexts beyond computing—genetic code, cryptologic code (i.e., ciphers such as Morse code), ethical code, building code, and so forth—each of which has a common feature: it contains instructions that require a process in order to reach its intended end. Computer code requires the action of a compiler, energy, and (usually) inputs in order to become a useful program. Genetic code requires expression through the selective action of enzymes to produce proteins or RNA, ultimately producing a unique phenotype. Cryptologic code requires decryption in order to be converted into a usable message. Ethical codes, legal codes, and building codes all require processes of interpretation in order to be converted into action.

“The evolution of code is the story of the progress of human society from simplicity to complexity over the period of millennia.”

Code can include instructions we follow consciously and purposively, and those we follow unconsciously and intuitively. Code can be understood tacitly, it can be written, or it can be embedded in hardware. Code can be stored, transmitted, received, and modified. Code captures the algorithmic nature of instructions as well as their evolutionary character.

Code as I intend the word here incorporates elements of computer code, genetic code, cryptologic code, and other forms as well. But you will also see that it stands alone as its own concept—the instructions and algorithms that guide production in the economy—for which no adequate word yet exists. To convey the intuitive meaning of the concept I intend to communicate with the word “code,” as well as its breadth, I use two specific and carefully selected words interchangeably with code: recipe and technology.

The culinary recipe is not merely a metaphor for the how of production; the recipe is, rather, the most literal and direct example of code as I use the word. There has been code in production since the first time a human being prepared food. Indeed, if we restrict “production” to mean the preparation of food for consumption, we can start by imagining every single meal consumed by the roughly 100 billion people who have lived since we human beings cooked our first meal about 400,000 years ago: approximately four quadrillion prepared meals have been consumed throughout human history. Each of those meals was in fact (not in theory) associated with some method by which the meal was produced—which is to say, the code for producing that meal.

“Code can include instructions we follow consciously and purposively, and those we follow unconsciously and intuitively.”

For most of the first 400,000 years that humans prepared meals we were not a numerous species and the code we used to prepare meals was relatively rudimentary. Therefore, the early volumes of an imaginary “Global Compendium of All Recipes” dedicated to prehistory would be quite slim. However, in the past two millennia, and particularly in the past 200 years, both the size of the human population and the complexity of our culinary preparations have taken off. As a result, the size of the volumes in our “Global Compendium” would have grown exponentially.

Let’s now go beyond the preparation of meals to consider the code involved in every good or service we humans have ever produced, for our own use or for exchange, from the earliest obsidian spear point to the most recent smartphone. When I talk about the evolution of code, I am referring to the contents of the global compendium containing all of those production recipes. They are numerous.

This brings me to the second word I use interchangeably with code: technology. If we have technological gizmos in mind, then the leap from recipes to technology seems big. However, the leap seems smaller if we consider the Greek origin of the word “technology.” The first half derives from techné (τέχνη), which signifies “art, craft, or trade.” The second half derives from the word logos (λόγος), which signifies an “ordered account” or “reasoned discourse.” Thus technology literally means “an ordered account of art, craft, or trade”— in other words, broadly speaking, a recipe.

Substantial anthropological research suggests that culinary recipes were the earliest and among the most transformative technologies employed by humans. We have understood for some time that cooking accelerated human evolution by substantially increasing the nutrients absorbed in the stomach and small intestine. However, recent research suggests that human ancestors were using recipes to prepare food to dramatic effect as early as two million years ago—even before we learned to control fire and began cooking, which occurred about 400,000 years ago. Simply slicing meats and pounding tubers (such as yams), as was done by our earliest ancestors, turns out to yield digestive advantages that are comparable to those realized by cooking. Cooked or raw, increased nutrient intake enabled us to evolve smaller teeth and chewing muscles and even a smaller gut than our ancestors or primate cousins. These evolutionary adaptations in turn supported the development of humans’ larger, energy-hungry brain.

Featured image credit: Untitled by Pixabay. CC0 via Pexels.

The post To understand the evolution of the economy, track its DNA appeared first on OUPblog.

Reproductive rights and equality under challenge in the US

For the over 40 years since the US Supreme Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade that people have a constitutionally protected interest in deciding whether or not to reproduce, reproductive rights have been a persistent flashpoint of controversy in the United States. The controversy has been characterized by more heat than light, however. It features little attention to why pregnancies occur, how unwanted pregnancies might successfully be prevented, and what supports women’s need for healthy pregnancies and care for their children.

First there was the Hyde Amendment prohibiting the expenditure of federal Medicaid funds for abortions. The Amendment has been renewed every year since 1977, softened only to permit funding when the women’s life is endangered or the pregnancy resulted from rape or incest. The current Congress plans to make it “permanent” in the sense that it will continue without annual renewal. The Amendment’s reach now extends to health care coverage provided for federal employees, for people serving in the military and their families, for Native Americans and Alaskan Natives, and for inmates in federal prisons.

Then, there was the so-called “Mexico City” policy forbidding family planning services world-wide from furthering abortions in any way—even telling patients about the option—if they accept funding from the US government. According to a World Health Organization study, this policy may have had the perverse effect of actually increasing abortions, if family planning agencies forego US funding because they cannot make the required assurances—and thus have fewer resources available for pregnancy prevention. Critics claim that the study is based on flawed data, however. All Republican presidents since President Reagan in 1980 have ordered implementation of the policy; all Democratic presidents have rescinded it. One of President Trump’s first executive orders reinstated the policy but went far further: it now will apply to any health agency receiving US funding, including those providing HIV treatment.

Women’s March on Washington by Mobilus In Mobili. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Women’s March on Washington by Mobilus In Mobili. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Most recently, there’s been the Affordable Care Act’s inclusion of contraceptive coverage as a required essential health benefit. Churches and other religious institutions were exempted from the requirement on the basis of the constitutional protection of the free exercise of religion. This included religiously owned institutions such as schools and universities, hospitals, and nursing homes. The Supreme Court’s Hobby Lobby decision expanded this free exercise reasoning to cover closely held for-profit corporations whose owners had faith-based opposition to contraception. Anyone working for these employers who wishes contraceptive coverage will need to get it from a third party rather than their employer.

All along, the courts have been at the center of efforts to undo Roe v. Wade. Social conservatives have been galvanized to support or oppose potential nominees to the bench based on their likely views about reproductive rights. Neil Gorsuch, President Trump’s nominee for the US Supreme Court, voted in favor of exempting religious employers from the contraceptive mandate. In the Tenth Circuit’s decision in the Hobby Lobby case, he wrote that religious owners of for-profit businesses should be protected from what they regarded as complicity in an immoral act, that of providing their employees with insurance coverage for contraception. Judge Gorsuch has never ruled in an abortion case, so his views on that must be extrapolated from his other opinions and writings, including his well-known opposition to physician aid in dying.

If all of the other US Supreme Court justices remain on the bench and don’t change their views, it will take a second appointment to the Court to change the balance to opposition to Roe v. Wade itself. Just last term, the Court ruled 5-3 against Texas’s statutes requiring abortion clinics to be fully equipped as surgery centers and to have physicians with admitting privileges at hospitals within thirty miles. In this Whole Women’s Health decision, the majority reasoned that the restrictions placed a substantial burden on women’s reproductive rights but that Texas had no record evidence that the restrictions were needed to protect women’s health.

If the Trump administration and the current Congress have their way, however, state restrictions on abortion are likely to flourish and may ultimately prevail. Far less likely, however, is careful ethical consideration of what these changes may mean. Even now, many US women find abortion beyond their reach either economically or geographically. These women and their children face what may be life-limiting challenges. The US lacks paid family leave; any job protection for unpaid family leave is limited both in time and by the size of the employer. Housing subsidies are difficult to obtain and many families pay more than half of their income for substandard housing. Child care workers are underpaid; good child care is difficult to find and very expensive. In states that have not expanded Medicaid, healthy women who do not earn enough to qualify for subsidies on the health insurance exchanges may have no insurance at all. If proposals to repeal the Affordable Care Act move forward, many other women may lack access to health insurance and the means to pay for contraception or other forms of health care. Mental health and substance abuse treatment may become increasingly unavailable, potentially increasing the risks of unwanted and unhealthy pregnancies. Proposals to move Medicaid and the related program for children, CHIP, to block grants may significantly reduce the funding for care that is now available.

In the myopia of single-issue politics about abortion, the life prospects of women and children have been marginalized. Justice Ginsburg’s insistence that reproductive rights are fundamental to equality has not drawn the attention it deserves. Without attention to why abortion and contraception matter, we may expect inequality in the United States only to deepen over the next few years.

Featured Image Credit: DC Women’s March by Liz Lemon. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Reproductive rights and equality under challenge in the US appeared first on OUPblog.

Fighting for Athens: the Battle of Marathon [excerpt]

The Battle of Marathon (490 BC) was the height of Persia’s first attempt to subjugate Greece. Athenian soldiers met Spartan ships near the town of Marathon, and—despite being outnumbered—drove Persia’s army out of Greece for ten years.

In this excerpt from The Plague of War: Athens, Sparta, and the Struggle for Ancient Greece, Jennifer Roberts describes what it was like to fight in the Battle of Marathon.

It was [the democratic state of Athens] that confronted the full wrath of Darius [the king of the Persian Empire] on the plain of Marathon. It was also an Athens filled with the same brand of trained soldiers to be found elsewhere in Greece: the hoplite. Starting with the rise of the polis, the Greeks— not just the Athenians— developed a fighting formation known as the hoplite phalanx. The fully evolved phalanx was customarily eight rows deep and ideally contained soldiers fitted out with the full hoplite panoply, each standing several feet from the next; of course, some less affluent soldiers could not afford a full panoply and were not as well armed offensively or defensively as their comrades. Customarily a hoplite soldier would carry a spear, usually about seven to nine feet long— maybe as much as ten— and a short slashing sword with a blade of some two feet, encased in a wooden scabbard covered in leather. He was well protected against the sharp points aimed at him by unfriendly soldiers on the opposing side.

His name came from his hoplon, a round concave shield about three feet in diameter made of wood faced with bronze and frequently emblazoned with vivid designs, sometimes from myth— though Spartans had their shields marked with the letter lambda, the first letter in Lacedaemon (the official name for the Spartan state). Because of its size, the hoplon was often quite heavy, sometimes nearly twenty pounds, and some soldiers even added a leather flap to the bottom to protect their legs, increasing the weight of the panoply still further. Additional weight was added by a cuirass, greaves, and helmet, all designed to be strong and to cover large areas of the body.

Reenactors at the Battle of Marathon reenactment, September 2011, Marathon, Greece. “Marathon’s Best” by Phokion. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Reenactors at the Battle of Marathon reenactment, September 2011, Marathon, Greece. “Marathon’s Best” by Phokion. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Helmets varied widely in design and often had horsehair plumes, which made the soldier look not only more imposing but literally taller; both Greeks and Romans, neither of them a tall race, regularly wore headgear in battle to compensate for their shortness of stature (not that the plumes made them any taller than their enemies, who were generally short men in tall plumes as well). As the armor was not customarily government issue, however, quality of defensive armor varied in proportion to the financial circumstances of the individual soldier; some cuirasses were made not of metal but of various layers of linen or canvas, and for many men a horsehair helmet was out of the question. The full panoply in all its glory probably cost as much as a mid- price automobile today.

Most important to this style of fighting was the hoplon, for since the soldier gripped it with his left arm only, each hoplite would have every incentive to stick close by the soldier to his right and not cut and run. It was the design of the hoplite shield that made the phalanx, and in many ways the phalanx shaped the evolving middle class in the many city- states of Greece: it required solidarity, and it was open only to those who could afford the weaponry. Though Sparta, with its unique social structure, did not have a middle class, it certainly had hoplites in abundance, and to these men the state probably provided arms and armor. With the Persians bearing down on them, the Athenians indeed sent to the Spartans for aid. But the Spartans, an exceptionally religious people, were celebrating the festival of the Carnea in honor of Apollo and responded that their army could not march until the full moon. So the Athenians faced the Persians at Marathon with only a small contingent from their nearby ally Plataea to back them up. While the Persian force was more versatile, with its cavalry and archers, the Greek hoplites fought in heavy armor and disciplined formation in defense of their own land. According to Herodotus, of their ten generals it was Miltiades who convinced the Athenians after several days of waiting in a strong position on a hill, looking down at the Persians who outnumbered them mightily, that they had best not wait any longer, since there was disaffection in the city and any further delay might induce many back in Athens to go over to the Persians. A relative of Thucydides, the persuasive Miltiades went down in history as the hero of this great battle.

Hoplite battle was terrifying under the best of circumstances— the difficulty of seeing through the helmet, the insufferable heat inside the armor (quite possibly complicated by the hot urine and excrement of the petrified soldier), the clanging of weapons, the slippery ground soaked with blood, the choking dust everywhere, the groans of the dead and the dying. And with such a slim chance of victory…. Yet in the end, those Greeks who were convinced that they were literally throwing themselves into the valley of death were mistaken. Knowing they were outnumbered, their commanders had intentionally left their center thin, concentrating all their strength on the wings. Their heavier armor and longer spears stood them in good stead, and though the Persians broke through their center as expected, the Greeks succeeded in routing them on their wings. Fleeing to their ships, many of the Persians drowned flailing about in the marshes. It would be hard to say who was more surprised by the Greek triumph, the Greeks or the Persians.

Featured image credit: Image extracted from page 060 of volume 2 of Herodotus. The text of Canon Rawlinson’s translation, with the notes abridged by A. J. Grant, Historian. Original held and digitized by the British Library. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Fighting for Athens: the Battle of Marathon [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

10 things you may not know about the making of the OED (Part 2)

In the first part of this article you may have learned various unexpected pieces of information about the history of the Oxford English Dictionary, such as the fact that it came close to being the Cambridge English Dictionary, or that one of the first lexicographers to work on it ended up being sacked for industrial espionage. Read on for more interesting episodes in the extraordinary history of this great project.

6. One OED assistant who fought in the First World War corrected some Dictionary proofs in a captured German dugout.

George Watson was taken on as a member of the OED’s editorial staff by William Craigie, the Dictionary’s third Editor, in 1907 and became his most trusted assistant. In 1917, he left Oxford to join the Devonshire Regiment, and he was soon on active service in France; but he had not left his lexicography behind. He corrected Dictionary proofs at the front, and on one occasion he took this work into a captured dugout—with a pencil in one hand and a candle in the other which frequently had to be blown out for fear of attracting the attention of German aeroplanes: an illustration of just how seriously some of the Dictionary’s staff took their work!

7. J.R.R. Tolkien composed a creation myth for “Middle-earth” while working as an editorial assistant on the Dictionary.

In early 1919, a new face appeared among the Dictionary staff: that of J.R.R. Tolkien, who had studied with Craigie while an undergraduate at Oxford. As the First World War came to an end, he wrote to his former tutor to ask whether he might have any work for him; he was duly taken on, working not for Craigie, but for his colleague Henry Bradley, who at that time was tackling the many difficult words beginning with W, many of which required particular expertise in Old and Middle English—expertise which Tolkien had in abundance. He had also begun to create his vast imagined world of “Middle-earth,” and to populate it with languages and legends. One of the legends, which he is known to have written during his time working on the OED, is “The Music of the Ainur”: a strikingly original creation myth, in which a creator God sings the universe into existence.

Signature of J.R.R. Tolkien from Heritage Auction Galleries. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Signature of J.R.R. Tolkien from Heritage Auction Galleries. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.8. Hundreds of thousands of the quotation slips originally collected for the Dictionary are now in America.

As the first edition of the Dictionary neared completion, it was proposed by William Craigie that there should be a family of dictionaries which each concentrated on a particular period of English, or a particular regional variety of the language, in greater detail. For each of these dictionaries, it was necessary to start afresh the process of collecting evidence, by the same method of reading and excerpting texts on which the OED itself had depended. It was realized, however, that each of these projects would be saved a lot of effort if they could use the quotations for the relevant period or variety that had been collected for the OED itself (after full use had been made of them). Accordingly, in 1927—a few months before the completion of the last section of the first edition of the Dictionary—quotation slips began to be extracted for the various other dictionaries. Ultimately, five projects received significant quantities of slips from the OED’s files, contributing to the compilation of dictionaries of Middle English, Early Modern English, American English, and early and later Scots, although one of these, the Early Modern English Dictionary, was eventually abandoned. The dictionaries of Middle English and American English were both compiled in America, at Ann Arbor, Michigan, and Chicago, respectively—the latter largely under the editorship of Craigie himself, who moved to Chicago to work on this and several other projects. The Middle English Dictionary was completed in 2001, and the project’s archive—including the hundreds of thousands of quotation slips contributed by the OED—is now housed in the Bentley Historical Library at the University of Michigan. Similarly, the editorial archive of the Dictionary of American English is preserved at the University of Chicago; however, after the dictionary was completed in 1944, the American lexicographer Clarence Barnhart bought the unused OED slips for American words in the project’s files; these subsequently became part of the “Barnhart Dictionary Archive,” which was recently acquired by the Lilly Library at Indiana University. (The quotation slips for the abortive Early Modern English Dictionary project were returned to Oxford in the 1990s so that they could be made use of in the OED’s own ongoing revision programme.)

9. William Chester Minor was not the only inmate of Broadmoor to contribute to the OED.

Dr Minor, the profoundly disturbed American surgeon and Civil War veteran who contributed so many thousands of quotations to the OED from inside the walls of Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum, must be one of the most well-known contributors to the first edition of the Dictionary. What is less well known is that at least two other inmates of what is now known as Broadmoor Hospital have contributed to the OED. In 1958, one Arthur Graham Bell, who had been sent to Broadmoor following the attempted murder of his father and two other men, began to send in contributions to Robert Burchfield, who had recently been appointed to edit the Supplement to the OED. He continued to send in contributions until 1966. Less is known about the other inmate, J.B.T. Norris, who began to send in quotations in 1972; his contributions were sufficiently useful that, to his delight, Burchfield sent him a copy of Volume 1 of the Supplement as a thank-you present: a gift which he described as “the nicest thing that has happened to me in the ten years which I have had to spend in this government establishment.” He continued to contribute for over a decade. He was eventually discharged from Broadmoor, and died in 2005.

10. One of the people doing consultancy for the OED today has been contributing to the Dictionary for nearly 60 years.

In fact many people have a record of contributing to the Dictionary continuing over 30 years or more. One early veteran was Frederick Furnivall, who was still sending in quotations half a century after he had helped to launch the Dictionary in the first place; he eventually died in 1910, having clocked up 53 years of contributions. The record for durability may be held by Henry Rope, who was engaged by Murray as an assistant in 1903 (just after he had graduated from Oxford), and who later also worked for Craigie; he left the staff in 1910, and subsequently became a Catholic priest, but he continued to contribute quotations to the Dictionary until 1976, by which time he was well into his tenth decade (he died in 1978). Roland Hall’s involvement with the Dictionary began in 1958, when—like so many others—he responded to an appeal to the public for quotation evidence. He was soon not only contributing quotations, but also acting as a consultant on entries relating to philosophy and psychology (he was a philosophy lecturer at the Universities of St Andrews and, later, York); and he is still a valued philosophy consultant today, nearly 60 years after his first contact with the project.

Feature image credit: “Oxford English Dictionary” by mrpolyonymous. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post 10 things you may not know about the making of the OED (Part 2) appeared first on OUPblog.

Voltaire and the one-liner

As we mark Voltaire’s 323rd birthday – though the date of 20 February is problematic, – what significance does the great Enlightenment writer have for us now? If I had to be very very short, I’d say that Voltaire lives on as a master of the one-liner. He presents us with a paradox. Voltaire wrote a huge amount – the definitive edition of his Complete works being produced by the Voltaire Foundation in Oxford will soon be finished, in around 200 volumes. And yet he is really famous for his short sentences. He likes being brief, though as a critic once remarked, “Voltaire is interminably brief.”

Voltaire’s most famous work, Candide, is full of telling phrases. “If this is the best of all possible worlds, what are the others?” asks Candide in Chapter 6. The expression “best of all possible worlds” comes originally from the philosopher Leibniz, but it is Voltaire’s repeated use of the phrase in Candide that has made it instantly familiar today. Another saying from the novel was an instant hit with French readers: in Chapter 16, Candide and his manservant Cacambo, travelling in the New World dressed as Jesuits, fall into the hands of cannibals who exclaim triumphantly: “Mangeons du jésuite” (“Let’s eat some Jesuit”): the Jesuits were highly unpopular in France at this time, and the expression instantly became a catch-phrase.

One French expression from Candide has even become proverbial in English. In 1756, the British lost Minorca to the French, as a result of which Admiral Byng was court-martialled and executed. Voltaire has fun with this in Chapter 23:

‘And why kill this admiral?’

‘Because he didn’t kill enough people,’ Candide was told. ‘He gave battle to a French admiral, and it has been found that he wasn’t close enough.’

‘But,’ said Candide, ‘the French admiral was just as far away from the English admiral as he was from him!’

‘Unquestionably,’ came the reply. ‘But in this country it is considered a good thing to kill an admiral from time to time, pour encourager les autres.’

Voltaire’s other writings are equally full of pithy and memorable short sentences, which often help him drive home a point, such as this, from his Questions sur l’Encyclopédie: “L’espèce humaine est la seule qui sache qu’elle doit mourir” (“The human species is unique in knowing it must die”).

Other lines, like this one from his poem about luxury, Le Mondain, “Le superflu, chose très nécessaire” (“The superfluous, a very necessary thing”) are all the more memorable for being in verse. Voltaire’s facility for producing snappy phrases is even there in his private correspondence, as this letter to his friend Damilaville (1 April 1766): “Quand la populace se mêle de raisonner, tout est perdu”(“When the masses get involved in reasoning, everything is lost”).

And one phrase that still resonates with us comes from a private notebook that Voltaire surely never intended to publish: “Dieu n’est pas pour les gros bataillons, mais pour ceux qui tirent le mieux” (“God is on the side not of the heavy battalions, but of the best shots”).

Then there are the ones that got away, the one-liners he never actually said – ‘misquotations’ in the parlance of the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations. Hardly a week passes without a newspaper quoting “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.”

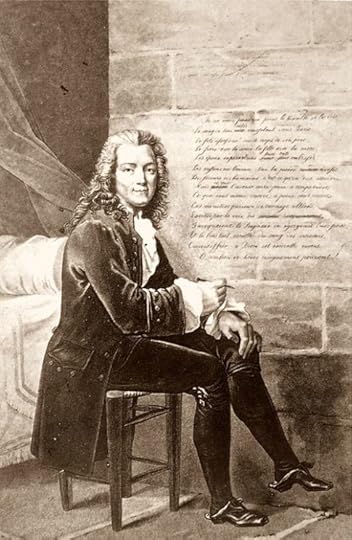

Voltaire.. After a painting, by Bouchot No. 539. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Voltaire.. After a painting, by Bouchot No. 539. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Voltaire’s rallying cry of free speech is central to our modern liberal agenda, so it’s a bit awkward that he never actually said it. The expression was made up in 1906 by an English woman, biographer E. B. Hall. But she meant well, and we have collectively decided that Voltaire should have said it. Another advantage of Voltaire’s one-liners is that they provide great marketing copy, and a quick search on the web reveals that many of them are for sale, on t-shirts, shopping-bags, and mugs. “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it” is especially popular, in French as well as English – which explains my favourite t-shirt: “Je me battrai jusqu’à ma mort pour que vous puissiez citer erronément Voltaire” (“I will fight to my death so that you can quote Voltaire incorrectly”).

Luckily, wit is contagious. There is a famous one-liner in Beaumarchais’ The Marriage of Figaro, when the servant Figaro imagines addressing his aristocratic master: “Vous vous êtes donné la peine de naître, et rien de plus” (“You took the trouble to be born, and nothing more”). This has become so celebrated that we have forgotten that Beaumarchais was only improving on a less snappy one-liner he had found in one of Voltaire’s more obscure comedies. George Bernard Shaw, a self-styled follower of Voltaire, has fun with misattributed sayings in Man and Superman:

Tanner: Let me remind you that Voltaire said that what was too silly to be said could be sung.

Straker: It wasn’t Voltaire. It was Bow Mar Shay.

Tanner: I stand corrected: Beaumarchais of course.

And so we go on inventing Voltaire. Another dictum that has recently gained wide currency on the web is this: “To learn who rules over you, simply find out who you are not allowed to criticize.”

Now regularly attributed to Voltaire, this saying seems to originate with something written in 1993 by Kevin Alfred Strom, an American neo-Nazi Holocaust denier, and not a man who obviously exudes Voltairean wit and irony. But once you become an authority, it seems, all sides have a claim on you.

The one-liner can seem a good way of encapsulating a truth: “Si Dieu n’existait pas, il faudrait l’inventer” (“If God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him”).

Voltaire knew he was on to a winner with this line, from a poem of 1768 (the Epître à l’auteur du livre des trois imposteurs), and he re-used it often in later works. Another much-repeated phrase occurs at the end of Candide. When the characters finally come together, after umpteen trials and tribulations, all argument is silenced with the words “Il faut cultiver notre jardin” (“We must cultivate our garden”). Is this a precious nugget of wisdom, neatly encapsulated? Or is it just another “Brexit means Brexit”, a trite phrase meaning anything and nothing? But that, of course, is another use of the one-liner: to maintain suspense, while bringing down the curtain at the end….

Featured image credit: Assassination of Henry IV by Gaspar Bouttats. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Voltaire and the one-liner appeared first on OUPblog.

March 9, 2017

How does acupuncture work? The role of S1 remapping

Acupuncture is a medical therapy that originated in China several thousand years ago and is rooted in a complex practice ritual based on a philosophy that predates our current understanding of physiology. Despite its long history, though, the intervention itself, particularly when coupled with electrical stimulation, significantly overlaps with many conventional peripherally-focused neuromodulatory therapies. A large body of clinical research has explored acupuncture for chronic pain disorders, demonstrating that acupuncture may be marginally better than sham acupuncture (e.g., non-inserted needles) in reducing pain ratings, but with small effect size. Still, several questions remain: how exactly does acupuncture work? Is acupuncture any better at improving physiological (i.e., objective) outcomes for chronic pain?

Even after so much clinical research, controversy persists as to whether or not acupuncture differs from placebo. Sham (non-inserted needle) acupuncture, which certainly sends inputs to the brain via skin receptors, is a sham device coupled with specific ritual and may thus produce a stronger placebo effect than, for example, a placebo pill. However, such symptom improvements may occur due to completely different physiological mechanisms compared to real acupuncture, whose mechanisms may more specifically target pathophysiology.

Most chronic pain disorders lack established biomarkers or objective outcomes. However, for carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS), a neuropathic pain disorder, local peripheral nerve-based outcomes are well established. These outcomes reflect physiology of the median nerve, which suffers from ischemia and fibrosis due to CTS, an entrapment neuropathy. Moreover, it’s not just the nerve in the wrist that’s affected in CTS. Research has clearly demonstrated that the brain, and particularly the primary somatosensory cortex (S1), is re-mapped by CTS. Following up on our pilot acupuncture neuroimaging study, our recent study is the first sham-controlled neuroimaging acupuncture study for CTS. Our results demonstrated that both real and sham acupuncture improved CTS symptoms. However, objective/physiological outcomes (both at the wrist and in the brain) showed specific improvement for acupuncture, compared to sham acupuncture, and were linked to long-term improvement in CTS symptoms.

Basic Acupuncture by Kyle Hunter. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Basic Acupuncture by Kyle Hunter. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Our results are analogous to a recent sham-controlled study of albuterol inhaler for asthma, which demonstrated that, while sham acupuncture and placebo inhaler was as effective as an albuterol inhaler in terms of symptom reduction, objective physiological outcomes (i.e., spirometry to assess forced expiratory volume) demonstrated significant improvement only for albuterol. Hence, sham acupuncture may “work” by modulating known placebo circuitry in the brain. In contrast, real acupuncture may improve symptoms by re-wiring the primary somatosensory cortex, in addition to modulating local blood flow to the peripheral nerve in the wrist. In other words, both peripheral and central neurophysiological changes in CTS may be halted or even reversed by electro-acupuncture interventions that provide more prolonged (compared to sham acupuncture) and regulated input to the brain – something that future longer-term neuroimaging studies should explore.

Interestingly, in S1, different body areas are represented in spatially distinct cortical regions. In fact, this body-specific map may serve as the basis for a crude form of “acupoint specificity” for acupuncture – a controversial topic, for sure. In the current study, we evaluated this speculative hypothesis by also comparing acupuncture local to the most-affected wrist with acupuncture targeting the opposite ankle. Our results suggested that both local and distal acupuncture improve median nerve function, and that neuroplasticity in S1 subregions specifically targeted by these local and distal acupuncture interventions (i.e. wrist and leg S1 cortical representations, respectively) were linked to improvements in median nerve function at the wrist following therapy.

While our research is an important step toward understanding how acupuncture works, more research linking objective/physiological and subjective/psychological outcomes for acupuncture analgesia needs to be performed. Once we better understand how acupuncture works to relieve pain, we can better optimize this therapy to provide effective, non-pharmacological care for chronic pain patients.

Featured image: 20100928 AlphaCityAcupunks-8 by Marnie Joyce. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post How does acupuncture work? The role of S1 remapping appeared first on OUPblog.

10 things you may not know about the making of the OED (Part 1)

The Oxford English Dictionary is recognized the world over, but much of its history isn’t so widely known: as with a respected professor or an admired parent, it’s all too easy simply to make use of its wisdom and authority without giving much thought to how it was acquired. Read on for some interesting nuggets of information about the history of this extraordinary project that you may not have encountered elsewhere.

1. The project which eventually became the OED was launched in Somerset House in 1857.

2017 marks the 160th anniversary of the decision by the Philological Society of London to establish a “Committee to collect unregistered words in English.” The Philological Society had been founded in 1842 with the declared objects of “the investigation of the Structure, the Affinities, and the History of Languages; and the Philological Illustration of the Classical Writers of Greece and Rome,” but from its earliest years, it had taken a particular interest in the study of the English language. Initially, its meetings took place in the London Library in St James’s Square, but they later moved to the rooms occupied by the Royal Astronomical Society at Somerset House in the Strand; and it was here, in June 1857, that it was announced that the Society’s Council had appointed the aforementioned Committee, consisting of Herbert Coleridge, Frederick Furnivall, and Richard Chenevix Trench. The Committee’s original aim was to collect evidence only for words which were not already “registered” in two of the most important dictionaries of English then available—the latest edition of Samuel Johnson’s famous dictionary, and a more recent dictionary compiled by Charles Richardson—so that these “unregistered” words could be covered in a new supplementary dictionary; but a few months later, the Society resolved to expand the remit of the project to embrace the compilation of a fully comprehensive dictionary of the language.

2. The Dictionary could have become known as the Cambridge English Dictionary, had it not been turned down by Cambridge.

During the project’s early years, the right to publish the Dictionary was offered to various publishers, including—in 1876—Cambridge University Press, who were approached by Frederick Furnivall (himself a Cambridge graduate) with an invitation to “take up a big thing that’ll ultimately bring you a lot of profit and do you great credit.” The proposal was swiftly rejected by Cambridge, who seem to have been suspicious of the rather eccentric Furnivall, and a few months later, Oxford University Press were approached with a similar proposal, which—after nearly two years of negotiations—led to the signing of contracts between the Press, the Philological Society, and the Dictionary’s first Editor, James Murray. In fact, the Dictionary never did bring “a lot of profit” to OUP—one estimate from 1928, the year when the first edition was finally completed, put the total costs at £400,000—but it did certainly bring “great credit.”

3. The first person to be employed as an editorial assistant on the OED had to be sacked for industrial espionage.

The first person to work alongside James Murray after he became Editor of the Dictionary was his brother-in-law, Fred Ruthven, but he was engaged mainly in secretarial and clerical work. He also fitted out the purpose—built shed where the Dictionary was to be compiled—which became known as the “Scriptorium”—with shelves and pigeonholes, in order to store the two million-odd quotation slips that had been collected. He was soon joined by Sidney Herrtage, a former civil engineer and amateur literary scholar who had been recommended to Murray by Furnivall as capable of assisting him with editorial work, and who did indeed proved to be a capable assistant, drafting Dictionary entries for Murray to review. However, in 1882 he was horrified to discover that Herrtage had begun to work for a rival dictionary project—the Encyclopedic Dictionary, published by Cassells under the editorship of Robert Hunter—and, even worse, was secretly making use of the materials in the Scriptorium in his work for Hunter’s dictionary. Such a betrayal of trust left Murray with little option but to dismiss him. Herrtage—who was also discovered to have “borrowed” some valuable books from the Scriptorium—went on to write most of the definitions in the Encyclopedic Dictionary. His place in the Scriptorium was taken by Alfred Erlebach, whom Murray knew from teaching alongside him at Mill Hill School; he proved to be a much more reliable assistant (and was soon joined by many others).

The Strand front of Somerset House and St Mary-le-Strand church. Print published by Ackermann and Co in 1836. Artist unknown via Wikimedia Commons.

The Strand front of Somerset House and St Mary-le-Strand church. Print published by Ackermann and Co in 1836. Artist unknown via Wikimedia Commons.4. Working conditions in the Scriptorium were once described as “pestilential almost beyond endurance.”

After six years at Mill Hill, where Murray combined school teaching with his work on the Dictionary, it was decided that the project should be moved to Oxford, with the aim of allowing Murray to concentrate entirely on lexicography (and therefore make better progress: only one section of the Dictionary, extending as far as the word ant, had so far been published). His new house in Oxford needed a new Scriptorium; but it was intimated to Murray that his new neighbour, an Oxford professor called Albert Venn Dicey, did not wish to have the view from his house spoilt by the new building. Accordingly, Murray’s Oxford Scriptorium was sunk more than two feet into the ground. In consequence it suffered permanently from damp, and in winter was extremely cold. Murray is reported to have sometimes sat at his desk in a thick overcoat with his feet in a box to keep out droughts. Several of his assistants were less hardy, and in fact found conditions in the Scriptorium so bad that they had to give up their work. It was the assistant Arthur Strong who, in 1888—only a few months after starting work—described the atmosphere as “pestilential almost beyond endurance”; he resigned the following spring.

5. The OED was pioneering in its employment of female editorial staff.

The first women to be employed on the OED were two “young women of fair education,” Miss Scott and Miss Skipper, who were taken on in 1879 to help with the massive task of sorting the accumulated quotation slips into alphabetical order. However, at this point in the 19th century, it was unusual for women to be employed to do anything more intellectually demanding than this; so that when, in 1889, Murray floated the idea of “engaging a little feminine assistance” among his regular staff, he knew that he was making a bold suggestion. In fact, the proposal met with a favourable response from OUP. Philip Lyttelton Gell, the man in charge of the Press at this time, commented: “I wish we could enlist a few thoroughly competent and qualified women in the work. There are many philologists among them nowadays.” Although in the event it was not until 1895 that he took on his first academically qualified female assistant: Mary Dormer Harris, who had studied English at Lady Margaret Hall in Oxford. She only stayed for six months—in fact she went on to work on another important lexicographical project, Joseph Wright’s English Dialect Dictionary—but she was soon followed by other women. And of course we should not overlook the female members of Murray’s own family: his wife Ada helped with the project from the beginning, and his daughters joined in (along with their brothers) as soon as they were old enough. Eleanor Bradley, the daughter of the Dictionary’s second Editor Henry Bradley, also worked alongside her father for many years.

Feature image credit: “Oxford English Dictionary” by mrpolyonymous. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post 10 things you may not know about the making of the OED (Part 1) appeared first on OUPblog.

In war, the earth matters

Many factors influence the outcome of war. But what has soil got to do with war? I suspect few have given much thought to the influence of soil on war, or, conversely, how war influences the soil. But the role of soil in warfare can be considerable, as can the impact of war on soil, which can often leave it unusable.

The most dramatic and emotive examples of the role of soil in war comes from the First World War, and the battles that occurred along the Western Front.

The Battle of Verdun, for example, was fought in 1916 in one of the wettest regions of France on heavy clay soils, which were turned into a sticky quagmire by the prolonged artillery bombardments; this not only hampered attacks, but also it led to many soldiers drowning in the very mud and craters that their own sides created. A similar picture emerged at the Battle of Passchendaele, 1917, commemorated later this year, which took place around Ypres on reclaimed marshland underlain with heavy clay, which became extremely sodden when wet. The battle started with intense bombardment, designed to weaken and demoralize the Germans. But it also served to destroy drains and churn the clayey land into a crater filled quagmire. And as if things couldn’t get worse, the rain began to fall as the Allied infantry attacked, turning the soil into liquid mud.

The mud caused havoc. It clogged rifles and swallowed up tanks and trenches, and hampered rescue operations as stretcher-bearers had to struggle through sucking mud. Soldiers and horses got trapped in the mud, and many drowned in it, and it created so much anxiety and disillusionment among soldiers that they considered it to be even worse than the shelling. As written in the front line newspaper Le Bochophage: “Hell is not fire, that would not be the ultimate in suffering. Hell is mud.”

By Ed Reynolds: directly inspired by Soil and War in R. Bardgett’s Earth Matters, and realized in the project Belowground Vision of Life: Soil makes Art, funded by the Leverhulme Trust and hosted by Dr Tancredi Caruso, Queen’s University of Belfast. Used with permission.

By Ed Reynolds: directly inspired by Soil and War in R. Bardgett’s Earth Matters, and realized in the project Belowground Vision of Life: Soil makes Art, funded by the Leverhulme Trust and hosted by Dr Tancredi Caruso, Queen’s University of Belfast. Used with permission.Soil conditions are also of paramount importance for tunneling, which has been part of warfare for centuries as a means of attacking enemy forces without having to warn or hide from the enemy. Essentially the best soils for tunneling are those that are easy to worked and excavated, but different soils pose different challenges. During the First World War, for example, the heavy clay soils around Ypres were ideally suited to tunneling being plastic and easy to excavate. But the clay expanded when wet, which placed considerable pressure on timber supports, and in some cases made them snap. Another problem was that the underlying geology around Ypres wasn’t uniform, being overlain in places by sediments of sand and silt, which created a complex and unpredictable soil to tunnel.

To the south, the underlying geology of the Western Front was chalk, which is soft and porous, and easy to dig. It is also very stable and dry, so tunnels were more self-supporting than at Flanders. But the chalk also created problems. Being very hard, the action of digging couldn’t be done in silence, as could be done in the clays of Flanders; as such, the element of secrecy was difficult to control. On top of this, the spoil from tunnels gleamed brilliant white in sunshine, so it was an obvious target for aerial observers. Another problem was that the water table fluctuated greatly in this region, so tunnels often flooded and surface soils became waterlogged and turned to mud.

Tunnels also played a major role in the Vietnam War, where they were used by the Viet Cong to launch surprise attacks on the Americans, and to shelter from American bombs and artillery. In some places, such as the Cu Chi district of South Vietnam, the tunnels created an extensive underground world, with living areas, hospitals, storage depots, and military headquarters, and also connected villages, districts, and even provinces. As noted by General Westmorland, who commanded the American forces in Vietnam from 1964 to 1968, “…the Viet Cong; they were human moles.”

A key reason why the tunnels of Cu Chi were so effective was the soil. The soils of this area are mostly lateritic clays, which are very deep weathered, rusty red soils that they are very hard, porous. And, unlike the heavy clays of Flanders, they are stable when wet. On top of this, the water table is very deep, allowing tunneling to depth, and extensive root systems of the forest helped to stabilize the tunnels. Put simply, the soils were ideal for tunneling and allowed the Viet Cong to go underground, causing much frustration for the Americans.

But as elsewhere, the soil created problems for the Viet Cong, the biggest being how to dispose of masses of soil in a way that it didn’t reveal the presence of tunnels to the Americans. To get around this, the Viet Cong came up with some ingenious ways of soil disposal. Excavated soil was poured into streams and craters left by American B-52 bombing raids, it was used to make furrows for potatoes and banks for combat trenches, and it was secretly transported away from tunnels in crocks, which were small pots used by women to carry fish sauce.

As already mentioned, warfare and all its horror can also scar the soil, and the scale of these scars can be astonishing. For example, artillery bombardments of unimaginable scale left soils pulverized during the first World War, and the legacy of this soil obliteration can still be seen today; the use of Agent Orange in Vietnam has left a lingering and deadly fingerprint on the soil, and in some cases soils have been left so toxic that they are unusable; and the nuclear age has left its radioactive signature on soils across the world. Soils have also been contaminated with oil, such as during the Gulf War, and with heavy metals from fragments of shells during the First World War.

Given the many and varied ways that warfare can impact soil, and the amount of land that has been, or is, currently affected by war, it could be argued that warfare is one of the most dramatic, but under appreciated ways that humans can affect the soil.

Featured image credit: The War The Military Defense by Jarmoluk. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post In war, the earth matters appeared first on OUPblog.

Bob Dylan’s complicated relationship with fame [excerpt]

Bob Dylan’s complicated relationship with fame—evident in the fall of 2016, when he took weeks to acknowledge that he had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature—is nothing new. In this extract from Light Come Shining: The Transformations of Bob Dylan, author Andrew McCarron discusses Dylan’s complicated relationship with the press and explains how and why Dylan has created such a distorted, fragmented public image for himself.

Bob Dylan’s playful and at times antagonistic relationship with the press dates back to his early years on the folk scene in New York. When asked about his identity by straight- laced reporters with buzz cuts and sport coats, he frequently answered sarcastically: “a trapeze artist,” “a song and dance man,” “an ashtray bender,” and “a rabbit catcher.” Some of the more memorable moments from D. A. Pennebaker’s 1967 documentary Dont Look Back, which chronicles Dylan’s 1965 tour of England, involve Q&A sessions with reporters that elicit responses that range from absurdist to downright hostile. Dylan, ever- performing for Pennebaker’s camera, comes across as a bratty hipster. An entourage surrounds him at all times like a hive of spastic bees. His dark sunglasses, unruly hair, incessant cigarette smoking, and spitfire verbosity present the portrait of an amphetamine- fed young virtuoso trying to manage his considerable talent and fame. One stratagem was to lie to the press. Dylan explains during one interview that journalists were to be toyed with or ignored. “They ask the wrong questions,” he said, “like, What did you have for breakfast, What’s your favorite color, stuff like that. Newspaper reporters, man, they’re just hung up writers. … They got all these preconceived ideas about me, so I just play up to them.” The sardonic lyrics to his classic 1965 song “Ballad of a Thin Man” reflect the reality of an artist actively resisting the reductionisms of a journalist infamously named Mister Jones. The memorable first verse goes:

You walk into the room

With your pencil in your hand

You see somebody naked

And you say, “Who is that man?”

You try so hard

But you don’t understand

Just what you’ll say

When you get home

In Chronicles, Dylan writes about the public theater he engaged in to throw off the paparazzi, journalists, and fans who kept him from settling into a normal life after his retreat from the limelight in Woodstock. He traveled to Jerusalem and got himself photographed at the Western Wall wearing a skullcap, and he leaked a story to the press that he planned to give up songwriting altogether and attend the Rhode Island School of Design. He was besieged by sensational stories published by people he’d never met. Some claimed that he was on an eternal search for meaning or in great inner torment. “The press?” Dylan writes in his memoir. “I figured you lie to it. For the public eye, I went into the bucolic and mundane as far as possible.” He was trying to protect his wife and children from the intrusions of celebrity, not to mention his sense of sanity. And compared to others artists who were quite literally killed by it— Ernest Hemingway, Jack Kerouac, Kurt Cobain, and Amy Winehouse, for example— Dylan fared reasonably well. A big part of his relative success required deflecting the identities and projections that were hurled in his direction. But many of these projections became so entwined with his image that they were impossible to shake, turning him into a palimpsest of claims and counterclaims that distorted and fragmented the living and breathing man into a web of contested meanings.

President Barack Obama presents American musician Bob Dylan with a Medal of Freedom, Tuesday, May 29, 2012, during a ceremony at the White House in Washington. “President Barack Obama presents American musician Bob Dylan with a Medal of Freedom” by Bill Ingalls. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

President Barack Obama presents American musician Bob Dylan with a Medal of Freedom, Tuesday, May 29, 2012, during a ceremony at the White House in Washington. “President Barack Obama presents American musician Bob Dylan with a Medal of Freedom” by Bill Ingalls. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Consequently, from an outsider’s perspective, it’s hard to know where Dylan ends and the rumor mill of celebrity culture begins. There have been rumors of all types: secret marriages and births, sleazy womanizing, palimony suits, unflattering memoirs (the majority of which Dylan’s lawyers have successfully barred from publication), tabloid tell- all’s, creative nadirs and zeniths, drunken concert appearances, drug addiction, and frighteningly obsessive fans who have tried to forcibly remove his mask. Take, for example, Alan Jules Weberman. Described by Robert Shelton as “a would- be anarchist star, a wheeler- dealer of the freaked- out New Left,” Weberman spent several years in the late Sixties and early Seventies harassing Dylan by repeatedly digging through his garbage, phoning him at all hours of the day and night, and leading agitated mobs to his Greenwich Village home to demand that he stop shirking his duties as the conscience of a generation. Such incursions have become a fact of life. Dylan’s personal attorney, David Braun, is quoted by Clinton Heylin as saying, “In my twenty- two years’ experience of representing famous personages no other personality has attracted such attention, nor created such a demand for information about his personal affairs.”

Dylan’s identity as a shape- changing performance artist also makes him hard to pin down. Long captivated by the figure of the American minstrel, his musical identities have channeled the identities of a dustbowl Oakie, a Beat poet, a Nashville cat, a Civil War general, a Born Again evangelist, a delta bluesman, and— rather curiously— previous versions of himself. Albums like Love and Theft (2001) do as Dylan has always done: lifting liberally from traditional American music. Lyrics and melodies from the 1950s, 1940s, 1930s, and much earlier, flow through his songs like a Biblical deluge. Arguably Dylan’s greatest artistic contribution has been his ability to appropriate and synthesize American traditions— folk, bluegrass, rock, gospel, etc.— and assume the real and imagined personae that accompany them.

As I suggested at the onset of this chapter, these musical and lyrical quotations aren’t only a form of postmodern blackface. Although there’s little doubt that some of his masks are the calculated stunts and tricks of a wily performance artist, his appropriations are important expressions of his deeper sense of self and identity. Identity (whether artistic or personal), after all, isn’t a discrete entity that seamlessly develops as we travel through life but is instead an amalgamation of perceptions, feelings, memories, symbols, and narratives in a dynamic state of flux and reinvention. In the words of Sam Shepard, who chronicled Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue in 1975: “Dylan has … made himself up from scratch. That is, from the things he had around him and inside him. Dylan is an invention of his own mind.”

Featured image credit: Image by NikolayFrolochkin. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Bob Dylan’s complicated relationship with fame [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers