Oxford University Press's Blog, page 396

March 6, 2017

What happens after the Women’s March? Gender and immigrant/refugee rights

On the morning of President Trump’s inauguration, women stood back to back, with their hair braided to each other, on the Paso del Norte Bridge, which connects El Paso, Texas and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. As activist Xochitl R. Nicholson explained, the gesture of braiding, one often performed by women, symbolized women’s solidarity in the face of anti-immigrant discrimination. Participants marched in El Paso the next day during the nation-wide women’s marches, as a part of a new coalition called “Boundless Across Borders.”

The website for the 21 January Women’s March on Washington names “immigrant rights” as one of its “unity principles”:

[W]e believe in immigrant and refugee rights regardless of status or country of origin. It is our moral duty to keep families together and empower all aspiring Americans to fully participate in, and contribute to, our economy and society. We reject mass deportation, family detention, violations of due process and violence against queer and trans migrants. Immigration reform must establish a roadmap to citizenship, and provide equal opportunities and workplace protections for all. We recognize that the call to action to love our neighbor is not limited to the United States, because there is a global migration crisis. We believe migration is a human right and that no human being is illegal.

How might participants in the women’s marches respond to this unity principle?

1) Listen to the experiences of immigrants and refugees.

At the El Paso march, participants talked about the fears undocumented women face about being torn apart from their children, the possibility of deportation if they report domestic violence, or the possibility of being denied asylum. Queer and trans migrants often escape countries that see them as “deviants” only to encounter violence and bigotry at the hands of immigration officials or in detention centers. Smugglers take advantage of desperate migrants by stealing their money or raping and assaulting them. The lived realities of immigrants and refugees are more complex than the classifications governments may impose on them.

2) Recognize when gender is missing from key policies, laws, and political conversations regarding immigrant/refugee rights.

Take for example that gender is missing in refugee law. A refugee is someone who has received asylum, or legal protection from deportation due to fear of or experiences of persecution due to religion, race, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a social group. Gender is not on the list of accepted “grounds” of persecution in the 1951 United Nations Refugee Convention or the 1980 United States Refugee Act. But gendered persecution exists, comprising violence against people who have not lived up to gendered expectations; sexual violence used to punish or discipline women and men; and attacks on people with non-conforming gender identities and sexual orientation. Asylum seekers who have experienced gendered persecution must convincingly present the legitimacy of their claims to immigration officials and judges who may have different theories about what counts as gender violence and who counts as a victim.

Inquire further if gender is missing when it shouldn’t be. Dig deeper when it seems as if gender violence is being addressed to see who is being counted as a victim and who is not.

President Trump’s executive order on border security increases the power of asylum officers and immigration agents to decide which asylum seekers should proceed to immigration courts, where judges may be more equipped to understand the nuances of asylum claims. Immigration lawyers predict that officials will deny an increasing number of asylum claims, and these migrants will end up in detention centers and eventually deported. Some may avoid the risk of applying for asylum and instead live as undocumented migrants. The impact might be even more profound for gender claims, given the difficulty of proving a type of persecution not included in refugee law.

3) Be curious when gender is present in key policies, laws, and political conversations regarding immigrant/refugee rights.

Trump surrogates recently praised the president’s alleged crackdown on sex traffickers in his first weeks in office. They also drew attention to a meeting President Trump held at his daughter Ivanka’s behest with anti-trafficking organizations, including those with a focus on violence against women and children. Despite the administration’s hardline approach to keeping out and deporting certain immigrants and refugees, will there be an exception for foreign trafficking victims, who have historically received T visas to protect them from deportation? Is the Trump administration, per the executive order on trafficking, concerned about “murders, rapes, and other barbaric acts”?

Rather than accept this focus on trafficking at face value, let’s look at the context. Since the early 2000s, Christian evangelical groups, due to their moral panic about sexual immorality, have pushed US Congressional members to give victims legal protection from deportation and to empower law enforcement to address sex trafficking. Most of these groups are anti-prostitution, are far more concerned about sex trafficking than labor trafficking even though the latter is more prevalent, and have sought to increasingly inject their worldviews into US politics. This background is key when exploring how governmental officials proclaim to protect trafficking victims but criminalize sex workers, even those who have been trafficked. Also, governmental investigations prioritize sex traffickers over labor traffickers, because addressing violence against smuggled migrants and exploited migrant workers would ostensibly legitimize the rights of undocumented migrants. Given this history as well as the presence of the evangelical International Justice Mission at Trump’s meeting, I suspect that as we track future anti-trafficking efforts, these trends will continue.

The Women’s March on Washington occurred against the backdrop of heated debates about the inclusion of marginalized communities who did not feel that their voices were heard in the planning stages. If the unity principles are to be implemented, particularly regarding immigrant and refugee rights, then those inspired and galvanized by the March must become feminist detectives. Inquire further if gender is missing when it shouldn’t be. Dig deeper when it seems as if gender violence is being addressed to see who is being counted as a victim and who is not. Go to Paso del Norte Bridge to learn how some communities have always known about the connection between gender and immigrant/refugee rights.

Featured image credit: Women’s March on Washington by Mobilus In Mobili. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What happens after the Women’s March? Gender and immigrant/refugee rights appeared first on OUPblog.

Brexit, Shakespeare, and International Law

How to make sense of the Brexit vote and its aftermath? To where can we look if we are to learn more, and to learn more deeply, of the agonistic parts played by principle and pragmatism in human decision-making where self, sovereignty and economic well-being are concerned? In this short blog I will argue that King John – Shakespeare’s English history play with the earliest setting of all – casts the longest and, perhaps the strongest, light. The dramatic premise of the play is King John’s dispute with the King of France regarding the sovereignty of England. It is agreed that their dispute should be handed over to a plebiscite of the people, in this case, the citizens of Angiers who look down on the rival kings from the walls of their town. In this respect the play rehearses The EU referendum, in which the British public were raised to the castle walls and empowered to pass judgment on competitors for the sovereignty of their nation.

In the event, King John and King Philip of France make a peace based on a form of exchange or trade, only for their bargain to be forcibly broken off by the intervention of a Pan-European central authority – the Pope, represented in the play by his legate Pandulph. Nowadays the most celebrated event in King John’s reign is the sealing of Magna Carta. Shakespeare’s play reflects the fact that for his early modern contemporaries the most significant event was the surrender of the crown to the papal legate and King John’s receiving it back as a vassal of Pope Innocent III.

The “Brexit” vote has been labelled, somewhat dismissively, as a protest vote. This it may have been, but there is a long British tradition of protest against Pan-European authority. Julius Caesar felt it, the Nazi’s felt it and the Roman Catholic Church felt it. Let me pose a controversial possibility. Could it be that a predominantly Roman Catholic EU is still modelled along essentially Papal lines or still espouses the same federal, even feudal, ambitions? Was the Roman Catholic communion of nations the template for the European Community? Even if the answer is ‘no’, might it still seem so to the English from the perspective of their national history? A Eurobarometer poll of 2012 found that 48% of EU citizens describe themselves as Roman Catholics, which is four times times more than those who call themselves Protestants. Even more striking is that the UK is the only country, outside the Nordic nations, in which the number of respondents describing themselves as “Protestant” outnumbered those describing themselves as “Catholic”.

The death of King John, in an 1865 production of the play at the Drury Lane Theatre, London. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The death of King John, in an 1865 production of the play at the Drury Lane Theatre, London. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.In Shakespeare’s play, the Papal legate promises King John that “by the lawful power that I have, / Thou shalt stand cursed and excommunicate” (3.1.172-3). Can we hear this echoed in the threats levelled by the “remain” camp against the rebellious English in the lead-up to the referendum? When, in Shakespeare’s play the Papal legate compels France to withdraw from its bilateral pact with England, are there not clear parallels in the EU’s expectation that individual Member States should not enter into free-standing bilateral trade agreements with the UK post-Brexit? In Shakespeare’s play, the Papal legate threatens France with excommunication: “What canst thou say but will perplex thee more, / If thou stand excommunicate and cursed?” (3.1.232-3) and the Dauphin counsels his father to comply:

Bethink you, father; for the difference

Is purchase of a heavy curse from Rome,

Or the light loss of England for a friend (3.1.204-7)

Who should we say has played the part of the Papal legate, or the Pope, in the debate surrounding the UK’s EU referendum? It is hard to look beyond the President of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker. A lawyer, as Pope Innocent III was, Juncker, Pandulph-like, fanned the flames that the UK’s leave campaigners had lit. If a Member State were now to say to Herr Juncker, as King Philip of France said to Cardinal Pandulph “Out of your grace, devise, ordain, impose / Some gentle order, and then we shall be blessed / To do your pleasure and continue friends [with England]” (3.1.250-252), would we be surprised if Herr Juncker replied, as Cardinal Pandulph replied, “All form is formless, order orderless, / Save what is opposite to England’s love” (3.1.253-4). Pandulph’s words in response to King John’s defiance express the same sentiments we would expect to hear Herr Juncker direct to those in the UK who voted “leave”. The argument that the people of the UK made a mistake and will lose more than they gain is heard in Pandulph’s “‘Tis strange to think how much King John hath lost / In this which he accounts so clearly won” (3.4.121-122). The claim that the fight to take the UK out of Europe will be followed by a fight to keep the UK united within its own borders, is an echo of Pandulph’s “A sceptre snatched with an unruly hand / Must be as boisterously maintain’d as gained” (3.4.135-6). The prediction that the people of the UK will repent recalls Pandulph’s, “This act, so evilly borne, shall cool the hearts / Of all his people, and freeze up their zeal” (3.4.149-150).

The most attractive character in the play is the Bastard son of Richard the Lionheart. He stands throughout as a chorus or everyman, inviting the audience to share his critical commentary on the mischief of the ruling powers. The Bastard acknowledges that amongst King John’s forces raised against the French there are, along with those of noble and gentle birth, “Some bastards too!” (2.1.279). He has in mind the many common folk of England who lack formally legitimate social status, but we are all too aware nowadays that there are bastards of a baser sort – nationalists who default to racism or violence. It is dangerous to speculate on the opinions of Shakespeare the man, but we can suppose that Shakespeare was a friend to foreign refugees. We know that around 1604 Shakespeare lodged with Protestant (Huguenot) immigrants in London and it is around this time that Shakespeare contributed to the play Sir Thomas More in which he sets out “the strangers’ case” in a speech that Jonathan Bate and Dora Thornton have have called an “extraordinarily sympathetic evocation of Huguenot asylum seekers” [p15]. On the world stage post-Brexit, we might conclude, as Shakespeare’s King John concludes, that “Nought shall make us rue, / If England to itself do rest but true!” (5.6.110-118), but we should remember that England is true to itself when it protects the weak and protests against power.

Featured image credit: EU flag. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Brexit, Shakespeare, and International Law appeared first on OUPblog.

March 5, 2017

In defense of mathematics [excerpt]

Once reframed in its historical context, mathematics quickly loses its intimidating status. As a subject innately tied to culture, art, and philosophy, the study of mathematics leads to a clearer understanding of human culture and the world in which we live. In this shortened excerpt from A Brief History of Mathematical Thought, Luke Heaton discusses the reputation of mathematics and its significance to human life.

Mathematics is often praised (or ignored) on the grounds that it is far removed from the lives of ordinary people, but that assessment of the subject is utterly mistaken. As G. H. Hardy observed in A Mathematician’s Apology:

Most people have some appreciation of mathematics, just as most people can enjoy a pleasant tune; and there are probably more people really interested in mathematics than in music. Appearances suggest the contrary, but there are easy explanations. Music can be used to stimulate mass emotion, while mathematics cannot; and musical incapacity is recognized (no doubt rightly) as mildly discreditable, whereas most people are so frightened of the name of mathematics that they are ready, quite unaffectedly, to exaggerate their own mathematical stupidity.

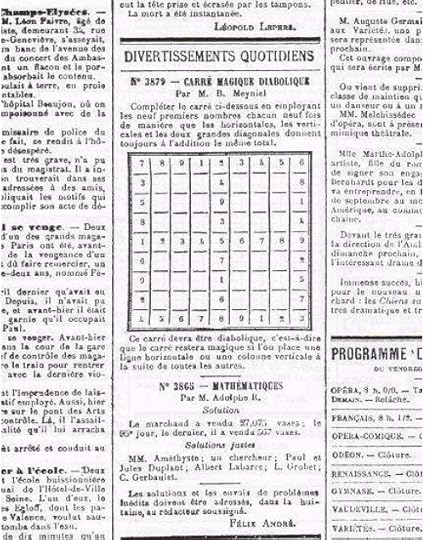

A 9×9 magic square from 1895 which also appears to be one of the earliest known sudokus. Credit: B. Meyniel, La France newspaper, dated 6 July 1895. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

A 9×9 magic square from 1895 which also appears to be one of the earliest known sudokus. Credit: B. Meyniel, La France newspaper, dated 6 July 1895. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.The considerable popularity of sudoku is a case in point. These puzzles require nothing but the application of mathematical logic, and yet to avoid scaring people off, they often carry the disclaimer “no mathematical knowledge required!” The mathematics that we know shapes the way we see the world, not least because mathematics serves as “the handmaiden of the sciences.” For example, an economist, an engineer, or a biologist might measure something several times, and then summarize their measurements by finding the mean or average value. Because we have developed the symbolic techniques for calculating mean values, we can formulate the useful but highly abstract concept of “the mean value.” We can only do this because we have a mathematical system of symbols. Without those symbols we could not record our data, let alone define the mean.

Mathematicians are interested in concepts and patterns, not just computation. Nevertheless, it should be clear to everyone that computational techniques have been of vital importance for many millennia. For example, most forms of trade are literally inconceivable without the concept of number, and without mathematics you could not organize an empire, or develop modern science. More generally, mathematical ideas are not just practically important: the conceptual tools that we have at our disposal shape the way we approach the world. As the psychologist Abraham Maslow famously remarked, “If the only tool you have is a hammer, you tend to treat everything as if it were a nail.” Although our ability to count, calculate, and measure things in the world is practically and psychologically critical, it is important to emphasize that mathematicians do not spend their time making calculations.

The great edifice of mathematical theorems has a crystalline perfection, and it can seem far removed from the messy and contingent realities of the everyday world. Nevertheless, mathematics is a product of human culture, which has co-evolved with our attempts to comprehend the world. Rather than picturing mathematics as the study of “abstract” objects, we can describe it as a poetry of patterns, in which our language brings about the truth that it proclaims. The idea that mathematicians bring about the truths that they proclaim may sound rather mysterious, but as a simple example, just think about the game of chess. By describing the rules we can call the game of chess into being, complete with truths that we did not think of when we first invented it. For example, whether or not anyone has ever actually played the game, we can prove that you cannot force a competent player into checkmate if the only pieces at your disposal are a king and a pair of knights. Chess is clearly a human invention, but this fact about chess must be true in any world where the rules of chess are the same, and we cannot imagine a world where we could not decide to keep our familiar rules in place.

“Checkmate” by Alan Light. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“Checkmate” by Alan Light. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Mathematical language and methodology present and represent structures that we can study, and those structures or patterns are as much a human invention as the game of chess. However, mathematics as a whole is much more than an arbitrary game, as the linguistic technologies that we have developed are genuinely fit for human purpose. For example, people (and other animals) mentally gather objects into groups, and we have found that the process of counting really does elucidate the plurality of those groups. Furthermore, the many different branches of mathematics are profoundly interconnected, to art, science, and the rest of mathematics.

In short, mathematics is a language and while we may be astounded that the universe is at all comprehensible, we should not be surprised that science is mathematical. Scientists need to be able to communicate their theories and when we have a rule-governed understanding, the instructions that a student can follow draw out patterns or structures that the mathematician can then study. When you understand it properly, the purely mathematical is not a distant abstraction – it is as close as the sense that we make of the world: what is seen right there in front of us. In my view, math is not abstract because it has to be, right from the word go. It actually begins with linguistic practice of the simplest and most sensible kind. We only pursue greater levels of abstraction because doing so is a necessary step in achieving the noble goals of modern mathematicians.

In particular, making our mathematical language more abstract means that our conclusions hold more generally, as when children realize that it makes no difference whether they are counting apples, pears, or people. From generation to generation, people have found that numbers and other formal systems are deeply compelling: they can shape our imagination, and what is more, they can enable comprehension.

Featured image credit: Image by Lum3n.com – Snufkin. CC0 public domain via Pexels.

The post In defense of mathematics [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

The culture of nastiness and the paradox of civility

Headlines are by their very nature designed to catch the eye, but Teddy Wayne’s ‘The Culture of Nastiness’ (New York Times, 18 February 2017) certainly caught my attention. Why? Because increasing survey evidence and datasets have identified growing social concerns about declining levels of civility. In the United States, for example, a recent poll found that 75% of those members of public surveyed believe that incivility has risen to crisis levels, 60% expect civility to get worse in the next few years. Politics, it would seem, has become raw, rude, direct, divisive… and don’t just think Trump… the rise of nationalist populism across the globe seems to have shifted the civic culture in ways that we really don’t understand or know how to deal with. The problem is that no one seems to know whom to blame. There are lots of culprits in the firing line for public condemnation (politicians, activists, bloggers, tweeters, journalists, shock jocks, etc.) but I cannot help but think that the challenge goes beyond the ‘usual suspects’ and raises far deeper issues of social interaction, social learning, and social capital.

In terms of understanding the emergence of this ‘culture of nastiness’ or – more specifically – the perception that levels of civility have or are being eroded, might begin from three positions. The first emphasizing ‘the vortex’, the second, ‘the vacum’, and third, ‘the twist.’

‘The vortex’ is rather obvious and highlights the manner in which being rude to an individual, organisation, or community generally provokes similarly bad-mannered responses that set in motion a sequence of increasingly unfriendly and discourteous interactions. Can you think of an occasion when being rude actually served a positive end? It’s possible that comedy and satire can use insolence and vulgarity to good effect but this is the exception rather then the rule. Meryl Streep was therefore onto something when she used her Golden Globes speech to suggest that ‘disrespect invites disrespect.’ The problem is, however, is that without someone brave enough or diplomatic enough (ideally both) to break this self-sustaining negative dynamic, all we end up with is yaa-boo playground politics.

Politics, it would seem, has become raw, rude, direct, divisive… and don’t just think Trump.

‘The vacum’ focuses on how hard it is to break out of incivility exactly because it demands a politician or party with the energy and ambition to recalibrate politics. This is a critical point. If the political system was a computer you’d probably switch it off at the wall and re-boot, you might even download some new software or anti-virus protection. The problem is that constitutional re-engineering is more difficult because those with the capacity to ‘reboot’ have little incentive to push the button. There is no clear alternative model of civil politics to transfer to and all the risks rests with those who dare to adopt a different style of politics. What’s more, the whole nature of the ‘culture of nastiness’ rests upon the destruction and havoc it casts upon those souls who do attempt to compromise, listen, accommodate, etc. These are the core values of democratic politics – the oil that stops the system grinding to a halt – and yet for ‘nasty people’ these traits are defined and dismissed as weakness. One of the saddest things about the murder of the British politician Jo Cox in June 2016 was the manner in which the initial period of open social reflection about the emergence of a culture of nastiness was so short-lived. After briefly doffing their caps media and main political parties quickly reverted to politics as normal.

And then there is ‘the twist’ (‘hook’ or ‘barb’). The contemporary analysis of the problem with democracy seems increasingly focused upon the unintended consequences of what is often termed ‘political correctness’. The ‘paradox of civility’ is therefore the manner in which the emergence of a culture shift that explicitly embraced social civility and understanding is now blamed for fuelling a culture of nastiness. Let me put this slightly differently, a set of social mores that became popularly embedded for around twenty years in an attempt to avoid words, terms, or behaviour that might exclude or offend certain sections of society has now been highlighted as a cause of the increase in behaviour that is explicitly designed to discriminate. To some extent this is not as novel – as twisty – as you might have thought. Right-wingers have attacked the ‘PC brigade’ for decades but the contemporary situation is quite different; it has, to some extent, been legitimated by the electoral success of those candidates and parties who claim to express the long-standing frustrations of the politically disillusioned and disenfranchised.

There is a certain repressive Freudian logic at play: individuals must be free to vent their emotional beliefs – no matter how irrational or hurtful they may be – in order to ensure a healthy open discussion of a full range of social concerns. Indeed, so the logic goes, the problem with the liberal elite that populists seek to displace is that they put political correctness above common sense. Large sections of the public could not voice their concerns about immigration, crime, or equality for fear of being immediately labelled as racist or bigoted…populist nationalism therefore provided exactly the lightning rod that allowed such frustrations to be vented. And vented they have done and continue to do…we are trapped in a vortex… a spiral of cynicism that – without the emergence of a new politics of civility – risks making political failure and further disillusionment almost inevitable.

Featured image credit: Megaphon by floeschie. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post The culture of nastiness and the paradox of civility appeared first on OUPblog.

Bastards and thrones in Medieval Europe

Today we use the term “bastard” as an insult, or to describe children born to non-marital unions. Being born to unmarried parents is largely free of the kind of stigma and legal incapacities once attached to it in Western cultures. Nevertheless, it still has associations of shame and sin. This disparagement of children born outside of marriage is widely assumed to be a legacy of Medieval Christian Europe, with its emphasis on compliance with Catholic marriage law.

Yet in fact, prior to the thirteenth century, legitimate marriage or its absence was not the key factor in determining quality of birth. Instead, what mattered was the social status of the parents, that of the mother as well as that of the father. It was being born to the right parents, regardless of whether they were married according to the strictures of the Church, that made a child seem more or less worthy of inheriting parents’ lands, properties, and titles. Consider, for example, the case of William the Conqueror. Born to Robert, Duke of Normandy and a woman most clearly not his wife, Herleva, William was nevertheless recognized by his father as his heir. Despite his youth and questionable birth, William managed to conquer and rule first Normandy and then England, and to pass his kingdom and titles on to his children.

We find this William called “bastardus” or “bastart” in medieval sources, but we also find him called “nothus,” an Ancient Greek term used to indicate birth to anything other than two Athenian citizens. Other “bastards” might be called “spurius,” an Ancient Latin term for a child born to illicit sex, or to an unknown father. In medieval usage “spurius” was a term typically associated with serious kinds of illicit or illegal sex, such as the child of a nun or priest, or the child of adultery or incest. But medieval authors did not use the term spurius for William. The relationship of the bachelor Duke Robert and his concubine Herleva, if not a formal marriage, did not offend on these grounds. Nor, evidently, did anyone at the time question Herleva’s sexual honor, or, as a result, William’s paternity.

Portrait of William the Conqueror by an unknown artist, circa 1620. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of William the Conqueror by an unknown artist, circa 1620. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Why then, was William called “the Bastard”? Writing about William in the twelfth century, chronicler Orderic Vitalis called him “nothus.” What might Orderic have meant by this? The only elaboration he offered, in a famous passage, suggests a concern not with William’s mother’s marital status but rather with his maternal lineage. During William’s siege of Alençon in the 1050s, as Orderic wrote, the people gathered on the battlements taunted William not about the fact that his father had not married his mother, but about his mother Herleva’s paternity, as the daughter of either a tanner or an undertaker. In other words, they objected not to his birth out of wedlock, but to his mother’s low status. That sense of what made a birth illegitimate matches the definition of nothus often found in early medieval sources. As one late eleventh century chronicler declared, the French called William bastard because of his mixed parentage: He bore both noble and ignoble blood, “obliquo sanguine.”

William’s success, despite his dubious birth, is not unique. Kings before and after him, and even queens, successfully inherited and reigned despite allegations of illegitimacy. We find many cases in which the children of illegal marriages, including even the children of monks and nuns, inherited noble and royal title throughout the twelfth century. Children born to a high status couple could inherit from those parents, even if their union violated contemporary prohibitions on marrying close kin, marrying those already married to other living spouses, or marrying those sworn to celibacy. Indeed we find little evidence that anyone challenged the rights of such children as heirs.

Why then have scholars believed that children born to something other than legitimate marriage were excluded? What scholars interpret as evidence of the exclusion of “bastards” in the modern sense is really evidence of parents’ freedom to bestow what lands and titles they possessed upon their offspring as they saw fit. Inheritance practices, while firmly rooted in an idea of family, operated with fluidity and flexibility as late as the twelfth century, and even, in some places, into the thirteenth century. Fathers could choose one child rather than another as heir, favoring on occasion younger sons and also daughters over their eldest sons.

To be sure, marrying legitimately certainly received a good deal of lip service throughout the Middle Ages. Nevertheless, in this pre-thirteenth-century world the most intense attention was paid not to the formation of legitimate marriages, but to the lineage and respectability of mothers. Only beginning in the second half of the twelfth century did birth outside of lawful marriage begin to render a child illegitimate, and as such potentially ineligible to inherit noble or royal title. In the thirteenth century both “bastard” and “spurius” came to signify a child born to anything other than a legitimate marriage, as defined by the canon law of the Catholic Church.

Understanding this helps us to better understand the history of illegitimacy, but also helps us arrive at a clearer picture of the workings and priorities of medieval western cultures before the thirteenth century. Status and lineage, not compliance with marriage law, determined a child’s prospects. Medieval society did not operate subject to rigid Christian canon law rules. Instead, it measured the value of its leaders based on their claims to celebrated ancestry, and the power attached to that kind of legitimacy.

Featured image credit: Bayeux Tapestry, Scene 44—Duke William and his two half-brothers: to his right, Bishop Odo of Bayeux and to his left, Count Robert of Mortain. Photo by Myrabella. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Bastards and thrones in Medieval Europe appeared first on OUPblog.

Philosopher of the Month: Socrates

This March, the OUP Philosophy team honors Socrates (470-399 BC) as their Philosopher of the Month. As elusive as he is a groundbreaking figure in the history of philosophy, this Athenian thinker is perhaps best known as the mentor of Plato and the developer of the Socratic method. Although Socrates wrote nothing himself and thus remains to some degree mysterious, sources including Plato, Xenophon, and a comedy by Aristophanes in which Socrates is a central character, inform our modern understanding of his life and work.

Socrates was born in Athens, where he spent most of his life. His parents were Sophroniscus, a stonemason, and Phaenarete, a midwife. With his wife, Xanthippe, Socrates had three sons. While little is known of the first half of his life, Socrates grew to become a recognizable public figure, appearing in several popular plays and poems as an eccentric character with a loquacious persona who is often seen walking barefoot. Socrates was known to have served with distinction as a heavy infantryman in the Peloponnesian War, and Plato reports that he was present at the siege of Potidaea on the Aegean coast. Noted for his endurance, Socrates reportedly stood for 24 hours in motionless contemplation. In 400 or 399 BC, Socrates was arrested in Athens and charged with corrupting the youth, not recognizing the gods of the city, and introducing new divinities. With no record of the trial, it is impossible to infer on what grounds the accusations were made, and to what conduct on the part of Socrates they refer. After a trial produced a guilty verdict, Socrates was sentenced to death by suicide.

Because Socrates left no written record of his philosophy behind, it is challenging to ascertain which doctrines, if any, he actually held—a question which has been the source of scholarly deliberation for centuries. What is known of his actual beliefs comes to us through representations (the historical accuracy of which is a matter of debate) of the character of Socrates in the works of Plato and Xenophon. Both represent Socrates as having an interest in inductive reasoning and general definitions, and both attribute to him the idea that virtue is knowledge or wisdom. According to Plato, Socrates denies possession either, but does in some dialogues offer moral insight.

Scholar Peter Adamson, in his podcast series, History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps, devotes an entire episode on separating Socratic fact from fiction with his colleague, Rapahel Woolf.

https://blog.oup.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/HoP-017-Raphael-Woolf-on-Socrates.mp3

Absent the influence of Socrates, it is possible that Plato would have become a statesman rather than a philosopher—inconceivably altering the landscape of western philosophy. Successive generations of thinkers have shaped their own unique portrayals of him, from the asceticism of the Cynics, to the Enlightenment’s image of Socrates the rationalistic martyr. And so, in the spirit of the Socratic method, we invite you to answer: who was Socrates? Let us know in the comments below, or on Twitter using the hashtag #philsopherotm.

Featured image: David – The Death of Socrates. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Philosopher of the Month: Socrates appeared first on OUPblog.

March 4, 2017

What is artificial intelligence?

What is artificial intelligence? It’s an easy question to ask and a hard one to answer—for two reasons. First, there’s little agreement about what intelligence is. Second, there’s scant reason to believe that machine intelligence bears much relationship to human intelligence, at least so far.

There are many proposed definitions of artificial intelligence (AI), each with its own slant, but most are roughly aligned around the concept of creating computer programs or machines capable of behavior we would regard as intelligent if exhibited by humans. John McCarthy, a founding father of the discipline, described the process in 1955 as “that of making a machine behave in ways that would be called intelligent if a human were so behaving.”

But this seemingly sensible approach to characterizing AI is deeply flawed. Consider, for instance, the difficulty of defining, much less measuring, human intelligence. Our cultural predilection for reducing things to numeric measurements that facilitate direct comparison often creates a false patina of objectivity and precision, and attempts to quantify something as subjective and abstract as intelligence is clearly in this category. Young Sally’s IQ is seven points higher than Johnny’s? Please—find some fairer way to decide who gets that precious last slot in kindergarten. For just one example of attempts to tease this oversimplification apart, consider the controversial framework of developmental psychologist Howard Gardner, who proposes an eight-dimensional theory of intelligence ranging from “musical–rhythmic” through “bodily–kinesthetic” to “naturalistic.”

Nonetheless, it’s meaningful to say that one person is smarter than another, at least within many contexts. And there are certain markers of intelligence that are widely accepted and highly correlated with other indicators. For instance, how quickly and accurately students can add and subtract lists of numbers is extensively used as a measure of logical and quantitative abilities, not to mention attention to detail. But does it make any sense to apply this standard to a machine? A $1 calculator will beat any human being at this task hands down, even without hands. Prior to World War II, a “calculator” was a skilled professional. So is speed of calculation an indicator that machines possess superior intelligence? Of course not.

Tic tac toe by Symode09. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Tic tac toe by Symode09. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Complicating the task of comparing human and machine intelligence is that most AI researchers would agree that how you approach the problem is as important as whether you solve it. To understand why, consider a simple computer program that plays the game of tic-tac-toe (you may know this as noughts and crosses), where players alternate placing X’s and O’s on a three-by-three grid until one player completes three in a row, column, or diagonal (or all spaces are filled, in which case the game is a draw).

There are exactly 255,168 unique games of tic-tac-toe, and in today’s world of computers, it’s a fairly simple matter to generate all possible game sequences, mark the ones that are wins, and play a perfect game just by looking up each move in a table. But most people wouldn’t accept such a trivial program as artificially intelligent. Now imagine a different approach: a computer program with no preconceived notion of what the rules are, that observes humans playing the game and learns not only what it means to win but what strategies are most successful. For instance, it might learn that after one player gets two in a row, the other player should always make a blocking move, or that occupying three corners with blanks between them frequently results in a win. Most people would credit the program with AI, particularly since it was able to acquire the needed expertise without any guidance or instruction.

So what is artificial intelligence? The truth is, it’s not a science in the common sense of the word. Rather, it’s an aspirational concept that doesn’t quite fit today’s realities. Modern artificial intelligence is a grab bag of computational tools for dealing with a variety of problems that people approach using their native intelligence. But that doesn’t mean the problems require intelligence to solve or that the machines are “intelligent”– it simply means that there may be other ways to solve these problems.

Featured image credit: “Hand, Robot, Human, Machine” by geralt. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post What is artificial intelligence? appeared first on OUPblog.

Co-living: Utopia 2.0?

Eight months on from its opening, in May 2016, the London-based co-living enterprise known as The Collective Old Oak is still going strong. The residential concept, situated between North Acton and Wilesden Junction, now boasts 546 residents. The project has piqued the interest of locals and the media alike. Aimed predominantly at a generation of millennials locked into the notoriously prohibitive and uninspiring rental market, The Collective seeks to change the way people live in urban centres. Residents pay rent on small private bedrooms, but gain access to a range of spaces and facilities, including kitchens, dinning rooms, and lounges. There is also a communal library, cinema, sports bar, restaurant, games room, laundrette, gym, spa, and rooftop terrace, as well as regular community events. As much as anything, residents are offered a “fulfilling lifestyle” and a sense of community.

Co-living is a trend that emerged in America during the opening decade of the 21st century, starting in the “hacker mansions” of San Francisco, offering affordable accommodation to young techies drawn to the area by the various app startups taking root there. By 2013, attempts were made to formalize and expand the provision of co-living. Tom Currier dropped out of Stanford to establish a real estate startup called Campus, which purchased San Francisco property, equipped them with hot tubs and other shared facilities designed to promote a fun, but more affordable lifestyle, and then sold co-living “memberships.” Before long, co-living ventures spread to New York and other cosmopolitan centres. Campus eventually ran up too much debt and folded in 2015, but others have picked up where it left off.

The organization behind The Collective was conceived in 2010, in the LSE Library, by Reza Merchant, a student who thought it was possible to provide something other than the low quality, overpriced accommodation suffered by many young people in London. Initially providing serviced accommodation with some shared facilities on a relatively small scale, Reza made the jump to full-blown co-living provider in 2015. The Collective is now the largest complex of its type in the world. And there are plans to build more.

The Games Room, The Collective Old Oak. Used with permission.

The Games Room, The Collective Old Oak. Used with permission.So is this a new utopia? Utopia 2.0 for the millennial generation, where shared spaces, Facebook groups, and synced event calendars offer a new sense of community?

Certainly, co-living providers have appropriated the language of radical utopia. Residences are referred to as “the collective” or “the commune”; they provide an “intentional way of living,” a rational “design to life,” and they accent the formation of new types of “community.” This language emerged out of the visionary projects of the early utopian socialists, Henri Saint-Simon, Robert Owen, and Charles Fourier, each of whom sought to design vanguard communities that would harmonise human relations at the start of the nineteenth century. And as recent scholarly insights into utopia have revealed, we should not assume that utopian projects were divorced from reality—that “utopia” is just a pejorative term, signifying the unrealistic. Where the socialist utopias of the nineteenth century arose in response to the challenges of the nascent modern world, so co-living for millennials has emerged against a backdrop of expensive housing, crony landlords, and an impenetrable housing market.

The cooperative communities Owen established in New Lanark and New Harmony represented an attempt to mitigate the hardships of early capitalism and laissez-faire economics. Community and capitalism were harmonised, as residents formed a jointly owned venture that supported and provided for members. And while the communities themselves did not become a template for wider society, Owen’s vision of jointly owned enterprises gave rise to the hugely significant cooperative movement. As Vincent Geoghegan has noted, “the very greatest of the philosophers of the past […] used utopianism to puncture the complacency of their contemporaries.” Maybe the latest trend for co-living will help to solve the challenges of urban housing in the twenty-first century. Co-living providers are expressly targeting a generation of young professionals who want to experience city life, but feel aggrieved at the prohibitive reality of places like London and San Francisco. Those promoting co-living also cite growing concerns about a “loneliness epidemic,” as the modern world continues to limit our social interaction. Co-living promises community and shared experiences with like-minded people.

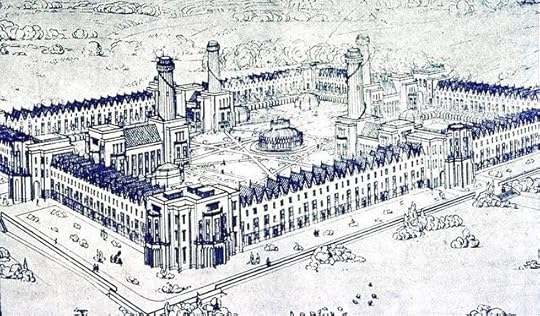

Robert Owen’s plans for New Harmony. Public Domain by ArtMechanic via Wikimedia Commons.

Robert Owen’s plans for New Harmony. Public Domain by ArtMechanic via Wikimedia Commons.But, lest it need stating, the latest trend for co-living lacks the holistic vision of “the very greatest of […] philosophers.” Co-living borrows from a long tradition of collective designs for life, from the Owenite communities and Fourier phalanxes of the early nineteenth century, to the urban communes and constructivist housing that emerged out of the Russian Revolution, and on to the hippie groups of the 1960s. But in its current incarnation, co-living is devoid of ideology. It’s postmodern: it is, in part, a response to the problems of a modern world, but it doesn’t share modernity’s conviction that the world can be perfected. It’s not necessarily a bad thing to avoid the arrogance of some utopian thinkers; the idea that progress can be made by ripping apart the past and starting afresh prevented men such as Owen from realising the shortfalls of their visions. Yet, given the genuine challenges co-living promises to tackle, a broader perspective, and input from the municipal or government level surely wouldn’t go amiss.

And we should be aware of some potential pitfalls. One clear limitation to co-living is that there is no collective ownership or viable long-term provision. It doesn’t solve the housing problem more broadly; it offers a temporary solution for young professionals who want to enjoy urban life and partake in, as New Yorker columnist Lizzie Widdicome put it, an “extended adolescence.” And, with this, there is the danger that transient young people will tend to occupy The Collective and other such co-living ventures. This has prompted concern over the wider impact that co-living residences might have on pre-existing communities.

Will co-living prompt a different attitude or approach to housing? Will housing “experience” really become a commodity, as the latest co-living startups suggest? Time will tell.

Featured image credit: The Collective Old Oak, London. Used with permission.

The post Co-living: Utopia 2.0? appeared first on OUPblog.

2017 Oscars represent a shift, but Hollywood is still disproportionately white

In 2017, the winners of two of the four Oscars given to actors were African Americans. This represents a remarkable turn in the history of the Oscars. It is not, however, a historical accident. Instead, it is due to social media campaigns and activism.

In 2015, an activist named April Reign started the hashtag #OscarsSoWhite in response to the overwhelmingly white Oscar nominees that year. When the Academy of Motion Pictures announced its 2016 Oscar nominees, the acting categories were again entirely white. In response, activists took to social media again with the hashtag. In 2016, the hashtag went viral and caught the attention of Hollywood. Filmmaker Spike Lee, actress Jada Pinkett- Smith, and others boycotted the 2016 Oscars over the striking lack of diversity in the nominees.

In June 2016, the Academy decided to do something about the racial imbalances in Oscar nominees. When the Academy extended 683 new membership invitations last year, 41% of them went to people of color. Changing the racial composition of the Academy has translated into a more balanced set of Oscar winners.

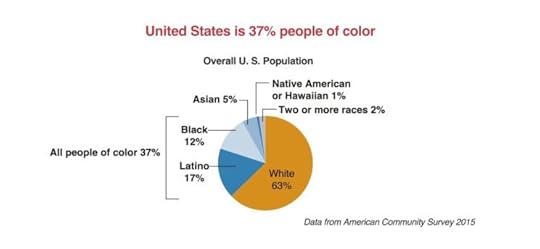

Racial breakdown of US population in 2015 by Tanya Golash-Boza. Data taken from American Community Survey 2015. Used with permission.

Racial breakdown of US population in 2015 by Tanya Golash-Boza. Data taken from American Community Survey 2015. Used with permission.In 2017, each of the four acting categories featured at least one nominee of color. As a result, half of the winners were black. African American actors Mahershala Ali and Viola Davis both took home Oscars, alongside white actors Casey Affleck and Emma Stone.

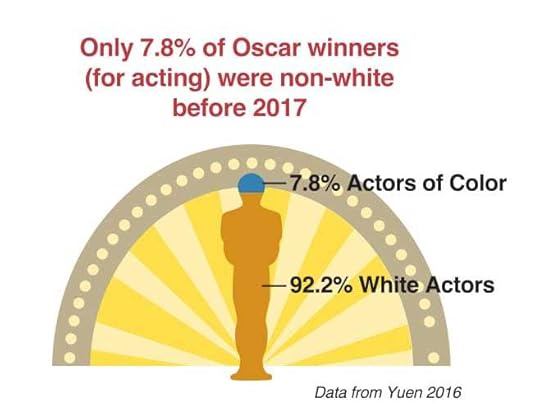

Graph 2 by Tanya Golash-Boza. Used with permission. Data taken from Reel Inequality by Nancy Yuen.

Graph 2 by Tanya Golash-Boza. Used with permission. Data taken from Reel Inequality by Nancy Yuen. Graph 3 by Tanya Golash-Boza. Used with permission. Data taken from Reel Inequality by Nancy Yuen.

Graph 3 by Tanya Golash-Boza. Used with permission. Data taken from Reel Inequality by Nancy Yuen.The presence of people of color as nominees and winners in the top categories represents a welcome shift for the Oscars. Notably, Dev Patel was the first actor of Indian descent to be nominated in 13 years and Mahershali Ali was the first Muslim actor to ever win an Oscar. However, no actor of indigenous, Latino/a, or Asian descent has won an Oscar in the past 16 years (Yuen 2016). Issues of representation of people of color in the media persist, and more work needs to be done.

According to a recent report on diversity in entertainment, only a quarter of all speaking roles for actors in films released in 2014 and prime-time first run television series were non-white, even though non-whites make up 37.9% of the US population.

Latino actors are the most underrepresented – only 5.8% of the speaking characters in 2014 were Latino, even though Latinos make up 17% of the US population. In 2013, there was not a single Latino with a leading role in the top ten movies of the year and scripted network TV shows. There were no Latinos among the top ten television show creators, and Latinos constituted just 1.1% of producers, 2% of writers, and 4.1% of directors in 2013. Finally, only one Latina ranked among the top 53 television, radio, and studio executives.

A 2016 study by Nancy Yuen found that even though whites make up 62.6% of the population, they constitute 74.1% of all speaking roles in film, 80.7% of all cable TV leads, 83.3% of all film leads, and 93.5% of all broadcast TV leads. Whites also account for 81% of all directors and 96% of all television network and studio heads.

The fact that two out of the four actors who won Oscars this year are African American is a remarkable milestone. It also teaches us a lesson about how greater diversity can be achieved in any arena. If you want to see more people of color in coveted positions, there needs to me diversity among the people who make the selections. Additionally, the pool of candidates from which you are choosing should be diverse.

Two African Americans won Oscars for their acting roles this year not just because they are excellent actors, but also because the Academy itself is more diverse than ever before, and the pool of nominees was the most diverse in history.

Featured image credit: 81st Academy Awards Ceremony by BDS2006. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Graph 2 and 3 credits: The Award of Merit statuette, fair use © A.M.P.A.S.®.

The post 2017 Oscars represent a shift, but Hollywood is still disproportionately white appeared first on OUPblog.

Learning the language of music: is it child’s play?

The Italian Reggio Emilia approach is now considered the most progressive and desirable early-childhood educational approach in the world. These schools value children’s innate abilities and nurture artistic and creative intelligences through play-based emersion in the “poetic languages” such as visual arts, music, poetry, dance, drama or photography. But how might a particular language, such as music, be taught in playful and natural ways that honor a child’s inborn abilities for language learning?

Careful observation of children’s musical development has shown that it is never too early for musical learning. Musical aptitude may actually begin in the womb. According to music psychologist Donald Hodges there may be specific genetic instructions in the brain that make the mind and body predisposed to be musical, “Just as we are born with the means to be linguistic, to learn the language of our culture, so we are born with the means to be responsive to the music of our culture.” Neuroscientists even have claimed evidence that babies are wired for music from birth. This “wiring” forms as the fetus responds to outside voices, music, and sounds from deep within the womb. These neurological mechanisms may also have an embedded relationship with language.

Careful observation of children’s musical development has shown that it is never too early for musical learning. Musical aptitude may actually begin in the womb.

During the child study movement of the early 20th century, the Pillsbury studies were the first long-term observational studies of children’s free music exploration. This classic study followed children from two to eight years of age and explored music activities, such as spontaneous improvisation on instruments, with very little adult intervention. Based on their observations, Moorhead and Pond found that: 1) all children had the ability and interest to experiment both with instruments and their voices to create music; 2) there was a strong relationship between the use of rhythm and speech; and 3) children naturally use movement and dramatization to embody their music-making. The Pillsbury studies were groundbreaking in the field of music education because they revealed that even without formal instruction, children were able to improvise and create semi-structured musical pieces.

More recently, a study was conducted involving children ages ten to thirty months where children were left alone to play with a variety of instruments. Video analysis revealed that children took great pleasure in producing sounds, displayed particular styles of performing, and used repetition and variations during improvised performances. Children’s music engagement, without adult intervention in everyday settings such as the playground or at home, has been found to contain complex expressions of children’s understandings of the world around them. These studies make it quite evident that children’s innate musical potential is often underestimated.

Musical play has been studied in music education research and has been found to be a natural way of engaging with music learning. Musical play has also been shown to increase overall auditory discrimination and attention as well as heighten musical skill development. When adults participate alongside children in musical play, the benefits are increased even further.

Adults might best support children’s music play by not considering themselves as authoritative holders of knowledge but as co-learners who are actively open and attentive to the interests of the children. For example, if some children expressed interest and curiosity in rain puddles, because a recent downpour just occurred that week, an adult might suggest playing with imaginary musical rain puddles made out of circles of string. Once such a scenario begins, children might then imagine that they are stepping around puddles and then play around with ideas for sound effects to accompany their puddle adventure. Some children might choose to walk around the puddle to the sound of the woodblock (sounding like footsteps), while others might choose to splash into the puddle with the sound of the cymbal. Some children might choose to sit down in the puddle to the glissando of a slide whistle, while others might imagine splashing their hands in the puddle with the accompaniment of a shaker sound. Together, both children and adults, play with musical sounds in playful and creative ways.

The Reggio approach emphasizes children’s innate abilities for developing “over a hundred languages.” Schools “inspired” by the Reggio approach employ arts specialists to work with children to provide high quality and intensive artistic experiences that allow children to build an artistic “alphabet” and eventually an artistic language for personal expression. One language in particular, music, is a natural fit for play-based, artistic learning. Does Mozart make you smarter or is there a little Mozart within? The answer may be both are true but the key is active engagement with music through playing and interacting musically with others. It appears that developing the language of music may, indeed, be considered, “child’s play.”

Featured image credit: “Piano Musical Instrument” by b1-foto. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Learning the language of music: is it child’s play? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers