Oxford University Press's Blog, page 399

February 28, 2017

Why queer history?

Fifteen years ago, as a junior scholar, I was advised not to publish my first book on the persecution of gay men in Germany. And now, one of the major journals in the field has devoted an entire special issue to the theme of queering German history. We have come a long way in recognising the merits of the history of sexuality–and same-sex sexuality by extension–as integral to the study of family, community, citizenship, and human rights. LGBT History Month provides a moment of reflection about struggles past and present affecting the LGBT communities. But it also allows us a moment to think collectively, as a discipline, about the methods and practices of history-making that have opened space to new lines of inquiry, rendering new historical actors visible in the process. In asking the question “why queer history? ” not only do we think about how we got here and the merits of doing this kind of work, but we question, too, whether such recuperative approaches always lead to more expansive, inclusive history. In other words, to queer history is not just to add more people to the historical record, it is a methodological engagement with how knowledge over the past is generated in the first place.

The great social movements of the 20th century created conditions for new kinds of historical claims making as working and indigenous people, women, and people of colour demanded that their stories be told. Social history, and later the cultural turn, provided the tools for the job. Guided by a politics of inclusivity, this first wave of analyses by scholars like the extraordinary John Boswell searched out evidence of a historical gay and lesbian identity–even marriage–in the early modern and medieval period. Michel Foucault’s History of Sexuality vol. 3 would fundamentally alter the playing field, as he questioned the veracity of such quests, arguing that it said far more about our contemporary need for redress than about history itself. Modern homosexual identity–he instructed historians –first emerged in the 19th century through the rise of modern medical and legal mechanisms of regulation and control. The discipline was turned on its head. Instead of detail-rich studies of friendship, “marriage”, and kinship a whole new subfield emerged focused around the penal code, policing, and deviance. In the process of unmasking the mechanisms of power that circumscribed the life of the homosexual, lost from view was the history of pleasure, of love, and even of lust. Although providing a much-needed critique of homophobic institutions, the result was a disproportionate concentration on the coercive modernity of the contemporary age.

And yet, despite these pitfalls, the Foucauldian turn introduced much-needed interdisciplinarity into historical analyses of same-sex practices. Of those who took up the challenge of a critical history of sexuality that sidestepped the pitfalls of finding a fully formed pre-modern identity were medievalists and early modernists keen on questions of periodization and temporality, basically how people in past societies held distinct ways of knowing and being what it meant to live outside the norm. If Foucault had fundamentally destabilised how we understood normalcy and deviance, these scholars wanted to take the discussion further still, to interrogate how the experience of time itself reflected the presumptions and experiences of the heteronormative life course.

Instead of a history of gays and lesbians, what was needed was a self-consciously queered history, one which took seriously how our own assumptions guide how we see the past.

By queering history, we move beyond what Laura Doan has called out as the field’s genealogical mooring towards a methodology that might even be used to study non-sexuality topics because of the emphasis on self-reflexivity and critique of overly simplistic, often binary, analyses. A queered history questions claims to a singular, linear march of time and universal experience and points out the unconscious ways in which progressive narrative arcs often seep into our analyses. To queer the past is to view it skeptically, to pull apart its constitutive pieces and analyse them from a variety of perspectives, taking nothing for granted.

This special issue on “Queering German History” picks up here. Keenly attuned to how power manifests as a subject of study in its own right as well as something we reproduce despite our best intentions to right past wrongs, a queer methodology emphasises overlap, contingency, competing forces, and complexity. It asks us to linger over our own assumptions and interrogate the role they play in the past we seek out and recreate in our own writing. To queer history, then, is to think about how even our best efforts of historical restitution might inadvertently circumscribe what is, in fact, discernible in the past despite attempts to make visible alternative ways of being in the world in the present.

Such concerns have profound implications for how we write our histories going forward. Whereas it was once difficult to countenance that LGBT lives might take their rightful place in the canon, the question we still have to account for is whose lives remain obscure while others acquire much-needed attention? While we celebrate how far we’ve come–and it is a huge victory, to be sure–let us not forget there still remains much work to be done.

Featured Image Credit: Arguments at the United States Supreme Court for Same-Sex Marriage on April 28, 2015 by Ted Eytan Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Why queer history? appeared first on OUPblog.

A librarian’s journey: from America to Saudi Arabia

King Abdullah University of Science Technology (KAUST) is based in Thuwal, Saudi Arabia, on the east shore of the Red Sea. It was founded by King Abdullah and opened its doors in 2009, with the vision of being a destination for scientific and technological education and research, to inspire discoveries that address global challenges, and striving to be a beacon of knowledge that bridges peoples and culture for the betterment of humanity.

In the middle of the KAUST campus sits the university library, an American Institute of Architects (AIA) award-winning piece of architecture with stunning views of the Red Sea. Recently we spoke with Janis Tyhurst, a librarian from the United States who works at KAUST, to find out about her career and what it’s like to work at this unique institution.

What is your first memory of the library at KAUST?

I remember walking upstairs to where the office is, and looking out at the Red Sea, at all those Mediterranean colours, the blues and aquas. You can see the KAUST beacon, which is the symbol of the university, through that window too. When you look out at the Red Sea with the KAUST Beacon in the foreground, it’s incredibly beautiful. That view is my first memory of the library.

The view over the Red Sea from the window of KAUST’s library. Used with permission of KAUST.

The view over the Red Sea from the window of KAUST’s library. Used with permission of KAUST.What makes KAUST different to other universities in Saudi?

It’s the late King’s legacy gift to the nation. The King was very visionary; he realized the country couldn’t depend on oil wealth forever. He already had this idea of a university in mind, and when he became King, he charged some of his people to build this university. It’s a graduate-level only research institution, and the idea is that it will be like Oxford or MIT or Stanford: a university where research focusing on national and global challenges would be done and promoted, as well as being a technology incubator generating new companies and employment opportunities for the benefit of the country.

It’s different from other Saudi universities because it’s a Western-style institution. The language is English only, and it’s the only campus in the country which is gender-mixed. We have students from around the world. The idea is to recruit the brightest minds to come and contribute. The largest section of the student population is Saudi, but there are people from around the world studying and working here.

You were Associate Reference Librarian at George Fox for many years before you started working at KAUST. Can you tell us some of the common challenges at both universities, and then about some of the new challenges you’ve faced at KAUST?

The common thing when you’re dealing with students and faculty is they think they know everything until they can’t find what they need! Focusing on the students at KAUST, many think that they can just Google everything. Faculty think the students should know how to do research before they arrive at the university. Our work as librarians is to build relationships where we can work collaboratively with students and faculty to raise awareness of the resources and services available to them.

Having said that, at KAUST there are a lot of unique advantages. The library is phenomenal. It’s probably the most fully resourced Science and Technology library in the world, and up to 98% of it is electronic. If a faculty member realizes they need a resource, we can get it; we don’t have to cancel something else.

Can you tell us about some of the projects you’re working on at the moment?

We’re working very hard on the issues of Article Processing Charges (APCs) and Open Access (OA). Faculty will often ask to pay to have their articles Open Access to get their research out there while the library is subscribing to the same content. We’re an OA campus, so we’re working on APC and OA language for our licensing.

What’s nearest and dearest to my heart, though, is developing an intellectual property (IP) awareness programme. We need to raise IP awareness, and we need to discuss how you go about turning research into IP. So far we have over 150 patents, including a solar panel cleaning technology called NOMADD, but we want to equip our researchers to effectively and efficiently navigate the process from research to patent.

What are you most proud of in your career as a librarian?

At my old institution they were going to phase out the information literacy programme, and it needed to be vastly improved and revamped. After a lot of work on the redesign of the programme, I managed to turn it around. But then it was made optional, which is often the kiss of death for these sorts of programmes. So for the next two years I worked really hard at marketing the program to faculty to get their buy-in, and at the end of that time it became an obligatory part of Orientation. I’m definitely most proud of saving the programme, and I want to build something similar with the IP awareness programme at KAUST, because it’s so important.

KAUST library exterior at night. Used with permission of KAUST.

KAUST library exterior at night. Used with permission of KAUST.Tell us about some of your hobbies—did you work on a lot of art shows in your library at George Fox?

Yes, I worked with the George Fox University Art department, which has an excellent programme and talented students. The art department didn’t have enough exhibit space to put on all the shows they wanted to produce and we had a lot of wall space in the library that was just blank. So in collaboration with the art department faculty, we set up a programme to host art shows in the library.

I think it brought more people into the library, and different sorts of people too. And what’s interesting is that when the engineering department heard what we were doing, they started helping out with hosting the art exhibitions in their building. The art exhibits started spreading out across campus.

The library at KAUST does similar things, not just art exhibitions alone, we host sessions like science cafes, where faculty and researchers come to talk about their research, and we lend our facilities to our annual winter enrichment programmes. All the graduation receptions happen here in the library building. It’s the perfect place, because when the sun goes down and you have all the lights on the horizon, it’s really quite a beautiful view.

What’s the most rewarding part of your job?

Working with so many different people. I have good colleagues, and I also really enjoy working with the faculty, who are doing some very interesting things, and the students, who come from all around the world, from Kazakhstan to Uruguay. It’s the people who really make or break it. We do the job because we love books and information, but it’s an even better job when we’re doing it with people we like.

Featured image credit: KAUST Library exterior at night. Used with permission of KAUST.

The post A librarian’s journey: from America to Saudi Arabia appeared first on OUPblog.

Why many wrongs make a right in the health sciences

Stories that link diseases to their possible causes are popular, and often generate humour, bemusement, and skepticism. Readers assume that today’s health hazards will be tomorrow’s health saviours. Rod Liddle’s headline in the Sunday Times is an example: “Toasties get you laid, fat prevents dementia and I’m a sex god.” Liddle starts with some fun statistics showing that those who ate cheese toasties had more enjoyable sex than those who did not. He then moves to a serious study showing that being overweight was associated with a lower risk of dementia. His contention, that it is hard to take such research seriously when contradictory results are so common, rings true. One of the latest controversies is that saturated fats, and particularly dairy fats, may have been undeservedly targeted in nutrition guidelines.

Other controversies in recent years include the role of hormone replacement therapy in women for the avoidance of cancers and heart disease, testosterone use in men, statins’ side effects, whether alcohol is good or bad for the heart, and the use of vitamin supplements, most recently around vitamin D. Alongside these, however, we should recall many similar settled issues that went through equally turbulent times, such as the effects of smoking including passive exposure, the laying of infants on their backs to prevent cot death, and the use of seat belts to reduce death and injury from road traffic accidents.

So why do medical sciences get it wrong so often? And what is the distinguishing feature of ideas that turn out to be right? Fundamentally, we get it wrong for three reasons. First, the causes of diseases are complex and so are the effects of factors that cause disease. Second, the scientific process is based on getting it wrong most of the time. Third, often our concepts and methods are incomplete and too blunt for the challenge.

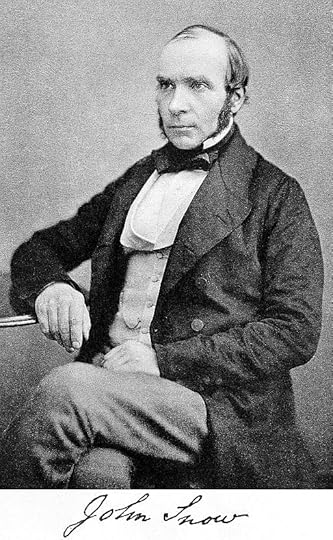

Dr. John Snow (1813-1858), British physician by the original uploader Rsabbatini at English Wikipedia. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Dr. John Snow (1813-1858), British physician by the original uploader Rsabbatini at English Wikipedia. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The causes of diseases are usually mysterious, and mysteries generate many explanations. The cause of cholera epidemics was a mystery in the mid-19th century and the founder of epidemiology, Dr John Snow, died long before his evidence that the causal route involved drinking contaminated water was accepted. It seems incredible that Snow’s evidence was rejected in favour of the discredited miasma theory. There was, however, a key concept missing at the time: the germ theory of disease. Without a proper understanding of microbes, people found it hard to understand how apparently clean water could cause diseases.

A triumph of 20th century medical science was proving the epidemic of lung cancer was primarily attributable to smoking tobacco. Now that we all agree, the controversies are forgotten. When large-scale investigations started in the 1940s and 1950s the cast of causal suspects was large and traffic-related pollution, including tar on roads, were amongst the leading explanations. There were decades of intense controversy before the evidence, mostly epidemiological, was accepted. The concepts underpinning the causal interpretation of data showing statistical associations between the risk factor (smoking) and outcome (lung cancer) were rudimentary and had to be articulated and agreed before we could resolve the controversies.

Science requires imagination and speculation in articulating a hypothesis, which is a succinct potential explanation of a phenomenon. The most recent hypothesis that my colleagues and I have published postulates that cooking at high heat (>150⁰ C) might be the reason why South Asians are highly susceptible to coronary heart disease including heart attacks, especially as compared to Chinese people. I will have no regrets if the hypothesis is wrong, especially as I am keen on Indian cuisine! Being wrong is part of the scientific process.

Often, our concepts and methods are insufficient for tackling unsolved problems. If not, we would solve the problems. Epidemiology usually kick-starts understanding. Epidemiology studies the differing patterns of diseases in subgroups of populations and explores the reasons for them. The evidence for differences is measured using incidence rates often expressed as the ratio of the incidence in one population compared to another (called relative risk or rate). For example, the incidence rate of CHD might be 300 per 100,000 in men per year and 150/100,000 in women per year meaning that men have twice the risk in women (relative risk = 2). This needs explanation and the starting point would be a hypothesis. Making such measurements in populations is hard and numerous errors arise because of faulty underlying data e.g. underestimated number of cases, wrong population size etc. Even if the data were accurate the explanation could be far from obvious.

Epidemiology usually kick-starts understanding.

Epidemiologists have evolved a tool-kit of study designs and data analysis methods. Of these, only one method is agreed to provide truly causal evidence – the perfect experiment, or as this is called in human research, the perfect trial. However, the ethical opportunity to test causal hypotheses in humans is rare. We could do this on animals but we’ll not be sure we can extrapolate the results to humans. Epidemiology, therefore, works mostly on non-experimental methods. This is a great strength of the discipline but it has its limitations. The biggest problem arising is called confounding. This arises when the populations being compared differ in ways relevant to the causation of the disease and not only in the way we are studying. Analysing data from observational studies to achieve causal understanding is seriously demanding. The concepts and techniques for causal interpretation of observational data have been evolving quite fast in the last 50 years but they remain insufficient. Currently, human judgement is a major ingredient in the causal path. In future, perhaps computers will help more, by objectively evaluating the evidence and setting out causal probabilities.

Meanwhile, scientists and the public, alike, will have to accept that in judging controversies such as whether eating fat prevents dementia, we will be wrong more often than right. When we are right, the benefits are usually huge. In medical sciences, many wrongs tend to eventually make a right!

Featured image credit: Cheese Toastie by Asnim Asnim. CC BY 2.0 via Unsplash.

The post Why many wrongs make a right in the health sciences appeared first on OUPblog.

Inter-professional practice: conflict and collaboration

The mission of the Association of Baccalaureate Program Directors is to promote excellence in the education of bachelor of social work students. Between 1 March and 5 March, 2017, over 600 social work educators and 120 students will gather in New Orleans for its annual conference. The theme of this year’s conference is, “BPD for the Future: Social Work Educations, Allied Professionals, and Students.” This theme highlights the importance of social workers being able to work effectively with allied professionals, such as physicians, nurses, educators, attorneys, psychologists, and other mental health professionals. The conference theme also builds on the Council on Social Work Education’s 2015 policies and standards which state, “Social workers value the importance of inter-professional teamwork and communication in interventions, recognizing that beneficial outcomes may require interdisciplinary, inter-professional, and inter-organizational collaboration.” The days of clearly delineated professional roles and independent responsibilities are fading. Whether social workers and other professionals are working in health care, addictions, criminal justice, education, community organizing, child welfare, or policy development, they need to understand how to work together as a cohesive team. In response to the need for greater collaboration between professionals, colleges and universities have been offering more and more forms of inter-professional education, including inter-professional courses, dual-degree programs, and field work experiences comprised of professionals from different backgrounds.

One of the most valuable competencies for fostering inter-professional collaboration is conflict resolution. Although social work shares many values and interests with other professions, there are many instances in which practitioners from different professions experience conflict. Consider an inter-professional team in a hospice, working with a patient who requests assistance with terminating her life. End-of-life-decision making may raise heated conflicts, not only between professionals, but also between, clients and family members. Some conflicts may arise due to differences in beliefs and values. Other conflicts may arise because of differences in the roles that each professional, client, and family member play or due to miscommunications.

Conflict resolution theory and research offer social workers and their colleagues evidence-based methods of assessing the nature of conflict, and determining what type of strategies may be best in managing the conflict. Thus, for managing miscommunications, the professionals may employ active listening and clarification skills, or they may engage the assistance of a mediator who specializes in facilitating communication. For role-related conflicts, professionals may use interest-based conflict resolution, exploring where they have joint interests and common ground, and generating options that meet the needs, concerns, and interests of all stakeholders. For value-related conflicts, the parties may never be able to reach consensus. For instance, the client may value autonomy and the ability to choose withdrawal of life supports, while the spouse may value life and reject the patient’s desire to remove the life supports. In this type of conflict, a transformative approach to conflict resolution may be desirable; that is, an approach which focuses on the quality of the interaction between the parties, allowing them to engage in a constructive conversation about the issues, regardless of whether they can reach agreement.

Chess figure game play by Devanath. Public domain via Pixabay.

Chess figure game play by Devanath. Public domain via Pixabay.Although some people assume that conflict is bad and should therefore be avoided, conflict resolution education teaches professionals to embrace conflict in a constructive manner. Conflict is a natural phenomenon within any social interaction, including interactions between practitioners from different backgrounds. Conflict may be a positive reflection of diverse cultures and points of view. Conflict may also be used to stimulate beneficial changes in policies and practices—as long as people are responding to conflict in a constructive manner. Research suggests that medical errors and malpractice are often associated with problems in communication or dysfunctional relationships between professionals. Having effective conflict resolution skills not only leads to better care and better outcomes for clients, but also more positive work relationships and environments. When people feel understood and supported by their co-workers and supervisors, they are happier and more likely to stay with their jobs.

Conflict resolution education does not aim to eliminate conflict between professionals. Rather, it teaches professionals how to manage intense emotions, how to respond to difficult problems, and how to treat people with respect despite significant differences in values, views, and interests. Not every conflict can be resolved in a perfect manner. Still, professionals can use conflict resolution strategies and skills to focus their energies on the needs and interests of the people they serve. “We may not be best of friends or think exactly alike, but we can work with each other in a respectful and collaborative manner.”

If you are an educator, what types of theories, skills, and strategies are you teaching students so they can engage effectively with co-workers and clients? If you are a student or professional, what type of conflicts do you think that educators should cover in their courses? What types of conflict resolution strategies and approaches do you think are most important in promoting effective inter-professional practice?

And if you are going to the BPD conference, I’m presenting on conflict resolution and restorative justice, as well as the new national Practice Standards on Social Work and Technology. I look forward to seeing you.

Featured image credit: Mardi Gras colors by Brett_Hondo. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Inter-professional practice: conflict and collaboration appeared first on OUPblog.

Alban Berg on the web and in social media

The date 9 February 2017 marked 132 years since the Viennese composer Alban Berg’s (1885-1935) birth. Despite this advanced age, Berg nonetheless maintains an active profile in social media. But before we review Berg’s current online profile, let’s take a moment to explore the “social media” of his time — the newspapers and magazines, coffee houses, and the “picture postcards” circulating around Vienna that kept members of the intellectual and artistic community in the loop and caused many to “friend” their fellows holding sympathetic views and also to “unfollow” those they found disagreeable.

The social center of Vienna in Berg’s time was the coffeehouse, in particular locales like the Café Central and the Café Impérial. Here, in a contemporary version of today’s Twitter, people congregated to catch up on the latest rumors, gossip, scandal, concert reviews, and political news, and to argue and debate the issues of the day with friends and trolls alike. A devoted aficionado of this world was Richard Engländer (1859-1919), who renamed himself Peter Altenberg, in an act somewhat like changing one’s social media account name today. Altenberg wrote aphoristic poems on “picture postcards” and then mailed them to friends — in particular to women who he admired. His coterie of admirees included Berg’s soon-to-be-wife Helene, who received several of his postcards. Berg, in turn, set five of these poems in his orchestral songs, the Opus 4 Altenberg Lieder. The notorious first performance of two of these songs in March 1913 caused precisely the kind of scandal that was the currency of the coffeehouse, as fist fights broke out in the Musikverein where the Skandalkonzert took place. It was not until 1952 that the Altenberg Lieder was performed in its entirety.

Another central feature of social life of the time were the newspapers and journals that fueled the polemics. Throughout his life, Berg was a great admirer of Karl Kraus (1874-1936), a savage critic of the hypocrisy and propaganda he found in the journalism of the time. Kraus, who may be described as a combination of two writers found much referenced in present-day social media, David Brooks of the New York Times and Andy Borowitz of the New Yorker, in that he provided intellectual satire and socio-political commentary for his devoted readers, produced his own publication, Die Fackel (The Torch) from 1899-1936. In this journal, Kraus attacked the establishment writings in the leading newspapers, including Neue Freie Presse, noting their promotion of attitudes against freedom in personal behavior and war-like attitudes around the time of WWI. Berg referenced Kraus multiple times in his correspondence with his mentor Arnold Schoenberg, and Die Fackel was required reading in his circle of friends and was passed around like shared posts on Facebook. But Kraus also had a much more profound influence on Berg’s music: it was Kraus’s speech at a performance of Wedekind’s Die Büchse der Pandora (Pandora’s Box) in 1905 which eventually motivated Berg’s use of multiple roles in his second opera Lulu, where the three husbands she victimized in Act I return as Lulu the prostitute’s three murderous clients at the end.

The coffeehouses and journals of Berg’s time, essential for those in his circle to stay abreast of the issues of the time, and to separate “false” news (opinion) from fact based on personality and personal loyalty, find their contemporary counterparts in the online world of social media. While the OUP online Bibliography sites are essential for serious research and documentation, in order to stay abreast of the latest news on composers such as Berg, one must venture into the interactive online world. Information found in these venues is difficult to catalog or find in traditional online search engines, and it changes constantly and requires verification. However, here we can find the latest recordings and reviews, conversations and issues, and get a sense of the “currency” of Berg’s music in the concert scene of today. The following includes some listings of what you can find related to Alban Berg and his music in the best-known social media and online sites.

Bust of Alban Berg in Austria. Photo: Johan Jaritz, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Bust of Alban Berg in Austria. Photo: Johan Jaritz, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The “Alban Berg” group on Facebook is a closed community (new members must be approved) of some 555 members. Such groups on this platform allow for enthusiasts to exchange information and promote news of their favorite issues and pieces. Recent posts include videos of Berg music performances, both live and studio recordings, as well as the following items of interest, which attest to the continued lively interest in the music of Berg and its place in the culture of the contemporary concert milieu:

1) A fascinating audio-only first-person account, by Theodore W. Adorno, containing reminiscences of Berg as a person, musician, and teacher. This clip supplements the incisive chapter “Ton” from Adorno’s book on Alban Berg.

2) A review of the recent production of Berg’s opera Lulu at the English National Opera in November of 2016 by William Hartson. Also posted are unpublished reviews; for instance, here is a review I wrote as a Facebook post in December of 2015, after viewing the same production given at the Metropolitan Opera in New York — I experienced the opera at a local movie theater as part of the Met’s broadcast schedule of performances. A DVD and Blueray recording of this production has been released by Nonesuch.

3) A review of a recently released recording of Berg’s Opus 1 Piano Sonata by Vincent Larderet (Ars Produktion ARS38217 SACD) released July 2016. Also in the news is a transcription of the Berg Piano Sonata for guitar, by Christopher Dejour, and a video post of Glenn Gould discussing the Piano Sonata, from the Facebook site devoted to Arnold Schoenberg.

4) A new DVD release of Lulu from the Salzburg Festival, as part of a three-opera release, also including Die Gezeichneten (Les Stigmatisés) of Franz Schreker and Die Soldaten (Les Soldats) of Bernd Aloïs Zimmermann.

Berg also has a presence at other social media sites: for instance, at Instagram, there are photos. Berg has a Twitter feed full of photos and links to performances, and even a Tumblr page, with items such as manuscript pages from the Lyric Suite, and a Myspace page, which has only photos.

An important resource for posts on social media sits is the mammoth holdings of YouTube — which contain many valuable resources related to Berg and his music. For instance, we can reference recordings with a scrolling score (the Opus 3 String Quartet and the Violin Concerto), listen to personal impressions of Berg from Schoenberg, and view a documentary on Berg by Misha Orenstein, as well as a four-part documentary on “The Secret Life of Alban Berg” by Claudio Dutra, concerning the secret programs in Berg’s final works, relating to his affair with Hanna Fuchs Robettin: Part I, Part II, Part III, and Part IV. For Berg scores, more of which are becoming available by the year due to the expiration of copyright dates, go to the Berg page of the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP) site. This amazing site supplies PDFs, MP3s, and other information on composers and their music, and is freely available (with some copyright restrictions depending on the country of the user’s origin).

By visiting and using these social media sites, and adding comments, posts, and likes, we can engage with other Berg aficionados from around the world. In this way, we recreate a virtual version of the Vienna coffeehouse of Berg’s time. I’ll take that post with a café espresso, bitte.

Featured Image credit: sheet music from Vier Stücke, a piece by Alban Berg. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Alban Berg on the web and in social media appeared first on OUPblog.

The Liberation Panther Movement and political activism

Throughout the 1990s, a radical and militant organisation in Tamil Nadu called the Liberation Panther Movement (Viduthalai Chiruthaigal Iyyakkam) engaged in an electoral boycott. In successive elections, committed cadres went to the polls and spoiled their ballots with slogans such as ‘none of you are honest, so none shall have our votes’, and ‘we lack the basic right to life, what use the political right to vote?’ Movement leaders spoke boldly of retaliating against caste violence and of returning a ‘hit for a hit’ in impassioned speeches that inspired a generation of young Dalits to challenge caste norms.

Scholars of protest and social movements argue that voicing a vocabulary of resistance, challenging taken-for-granted assumptions, and mapping out how things could be different are as important a part of the revolution as building the barricades and engaging in armed struggle. They invest the audience with a sense of the possibilities for change and encourage them to contest age old inequities. Certainly in 1999, villagers and townsfolk would quote examples or passages from Panther leader Thirumavalavan’s speeches to make a point or to explain their refusal to abide by caste practices. The rousing rhetoric of the Panthers, thus, played a prominent role in the Dalit politics of resistance.

Emboldened and inspired by Panther activism, Dalits fought back against overt practices of untouchability such as the use of separate tumblers in tea-shops and refused to perform menial tasks. The electoral boycott was an integral part of this upsurge and was designed to highlight the illegitimacy of existing political parties and emphasise that Dalits did not feel represented by the democratic process. Time and again movement leaders condemned state inaction against those responsible for caste atrocities. Were the police to arrest those setting light to Dalit homes, raping Dalit women, or exploiting Dalit labourers – activists insisted – then there would be no call for them to take to the streets or threaten to take the law into their own hands.

Electoral boycotts are potent symbols of disenfranchisement, and powerful indictments of processes of representation.

Electoral boycotts are potent symbols of disenfranchisement, and powerful indictments of processes of representation. They undermine politician’s claims to speak on behalf of the electorate and represent the diversity of the population. In so doing they delegitimise the process and question the inclusivity of the polity. In this instance the Panthers raised questions about the electoral process – noting that booths were often sited in dominant caste areas where Dalits could be intimidated – and the Hobson’s choice available – in that no party took meaningful action to address caste-based inequalities or discrimination.

In a study for Brookings Institute, Matthew Frankel outlines how widespread the practice of boycotting election is in noting that ten elections were boycotted each year between 1995-2004. He argues that threatening to boycott elections has been effective, especially when regimes are sensitive to issues of legitimacy and representation. He argues that actual boycotts generally end in failure and further marginalise those engaged in the protest. In 1999, the Liberation Panthers appeared to accept this logic and took the momentous decision to abandon extra-institutional protests and contest elections.

They formed the Liberation Panther Party (Viduthalai Chiruthaigal Katchi – VCK) and contested elections as part of a Third front of parties led by the Tamil State Congress. In justifying the move to political participation, Thirumavalavan argued that the boycott benefitted opponents, denied them a say in parliament, and enabled authorities to depict them as anti-democratic extremists. Entering the political fray meant, at the least, that other parties had to acknowledge them and consider how to appeal to Dalit voters.

Activists at the time feared that the move to politics would result in compromise. “If you rear a calf with pigs”, an activist once told me, “the calf too will eat shit”. Given their track-record of speaking truth to power and the close ties between leaders and people at the grassroots, however, several cadre and commentators felt that the Viduthalai Chiruthaigal had the potential to render parliamentary institutions more democratic and accountable. Time after time, however, radical challengers and inspiring protest leaders have disappointed their followers on attaining office. So universal is this finding, that there is a whole theory of ‘institutionalisation’ explaining how movements tend to lose their radicalism and become more bureaucratic upon entering institutions.

Whilst an autonomous Dalit party could potentially secure new gains and advantages for their constituents, there was always the risk that Dalits would lose a powerful advocate to the machinations of ‘normal politics’. In the decades since this point, the VCK have wrung some concessions from Tamil political institutions but have increasingly been cast as divorced from their core constituents. In order to win elections they have had to reach out to members of other castes and have diluted their radicalism and shifted their focus beyond Dalit concerns as a result. Electoral boycotts may be counter-productive, in other words, but political participation may also come at a cost.

Featured image credit: Marakkanam Salt Pans in Tamil Nadu, by Sandip Dey. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The Liberation Panther Movement and political activism appeared first on OUPblog.

February 27, 2017

Did Margaret Thatcher say that?

Margaret Thatcher, the first female Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, was a fearless leader who became of one of the most notable figures of 20th century British politics. She arguably had the greatest enduring influence of any of Britain’s post-war Prime Ministers. She is remembered for her extraordinary political impact, but also for her memorable turns of phrase.

Many of Thatchers one-liners swiftly became famous: “The Lady’s Not for Turning,” “There is no such thing as society,” “In politics if you want anything said, ask a man. If you want anything done, ask a woman.” To test your knowledge of political rhetoric, see if you can tell which of the following were not her words?

Quiz image credit: “Thatcher receives the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Bush, 1991” courtesy George Bush Presidential Library. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image credit: Margaret Thatcher visiting Salford. CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Did Margaret Thatcher say that? appeared first on OUPblog.

Quantum fields

Some say everything is made of atoms, but this is far from true. Light, radio, and other radiations aren’t made of atoms. Protons, neutrons, and electrons aren’t made of atoms, although atoms are made of them. Most importantly, 95% of the universe’s energy comes in the form of dark matter and dark energy, and these aren’t made of atoms.

The central message of our most fundamental physical theory, namely quantum physics, is that everything is made of quantized fields. To see what this means, we need to understand two things: fields, and quantization.

Everybody should play with magnets. Michael Faraday, in the mid-19th century, was impressed with the way magnets reach out across “mere space,” as he put it, to pull on iron objects and push or pull on other magnets. He conceived the modern field idea. His view, still held by scientists, was that a magnet alters the very nature of the space around the magnet. We call this alteration a “magnetic field.” You have probably also noticed electric fields, for instance in the clinging behavior of cloth being removed from a clothes dryer. Faraday and others learned that electric and magnetic fields are aspects of a single “electromagnetic (EM) field,” that all EM fields arise from “electrically charged” matter such as electrons, and that shaking an electrically charged object back-and-forth sends waves of EM field outward in all directions through space. Examples of such EM waves include light waves and radio waves.

Fields are physically real. Suppose, for example, you send a radio wave from Earth to Mars. On Mars, this wave shakes electrons in a radio receiver. Such shaking requires energy, and implies the radio wave has energy—energy that must have been carried to Mars by the EM field. So fields contain energy and for most physicists, energy is definitely something real.

Early in the 20th century, experiments showed that a light beam shining on a metal plate can eject electrons from the metal surface. Analysis showed this was possible only if the light beam was made of small bundles of energy, each capable of dislodging an electron from an atom in the metal. Today we say the EM field is “quantized” into small but space-filling bundles called “photons.”

In 1923, Louis de Broglie proposed the germ of an idea that became the quantum revolution’s key notion: perhaps not only EM radiation, but also matter (stuff that has mass and moves slower than light) such as protons, neutrons, and electrons is also a quantized field. This seems odd: how can these presumed “particles” be fields?

Here’s how. As we saw in a previous blog, when electrons pass through a double-slit experiment, the results imply that each electron comes through both slits, implying it is a spatially extended object, and it then “collapses” to atomic dimensions upon impacting a viewing screen. Quantum physics was invented during the 1920s to make sense of such phenomena. Electrons, as well as protons, neutrons, atoms, and molecules, are not particles. Electrons are spatially extended bundles of field energy, quite similar to photons, but photons are bundles of EM field energy while electrons are energy bundles of a new kind of field, a quantized material field called the “electron-positron field” (e-p field).

The world’s most powerful particle collider, used to discover the Higgs boson. “Large Hadron Collider dipole magnets” by alpinethread – Flickr. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The world’s most powerful particle collider, used to discover the Higgs boson. “Large Hadron Collider dipole magnets” by alpinethread – Flickr. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Moving to a larger perspective, the central notion of quantum physics is that the universe is made of about 20 fundamental types of “quantized fields,” all of them similar to the EM and e-p fields. Each fills the entire universe, and each is packaged into “quanta”: highly unified spatially extended bundles of field energy. The EM field and e-p field are examples. The former has quanta called “photons” that are massless and move at light speed, while the latter has quanta called “electrons” and “positrons” that have mass and move slower than light speed. There are also six types of quark fields, three kinds of neutrino fields, two other kinds of electron-like fields, and other fundamental fields including the recently-discovered Higgs field whose quantum is the Higgs boson. It’s thought that a “theory of everything” will eventually emerge that will unite all these fields in a single unified quantum field theory analogously to the way the EM field unites the electric and magnetic fields.

Dark matter is probably a quantized field whose quanta have not yet been discovered because they don’t emit or interact with light or with most normal matter. Dark energy is even more mysterious and might be an expression of the quantum vacuum (see below).

How do atoms and molecules fit into this picture? These are composite quanta, made of proton and neutron fields (which are themselves made of quark fields) and e-p fields. Atoms and molecules are highly “entangled” objects, causing them to act in many ways like single quanta.

An important new principle arises when we ask the simple question: what happens when we remove all the quanta from some region of space? Will that region simply be empty of all fields? The answer is that it cannot be empty. In fact, if any one of the quantum fields were entirely absent from some region, the strength of that field in that region would have to be zero. But this value, zero, is precise and has no uncertainty, so it violates a core quantum principle called the “uncertainty principle.” Thus all quantum fields must have a minimum or “vacuum” value even when there are no quanta at all. The quantum vacuum field must be present everywhere in the universe. In fact, photons and other quanta are best visualized as disturbances, or waves, in this universal vacuum field.

A region of space that lacked even the primeval vacuum field would have to vanish altogether. Empty space simply cannot exist. This is perhaps the closest physics can come to explaining why there is something rather than nothing.

Featured image credit: Particles by geralt. CC0 Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Quantum fields appeared first on OUPblog.

Cicero’s Defence Speeches: an audio guide

In this audio guide to Cicero’s Defence Speeches, Dominic Berry, senior lecturer in the School of History, Classics and Archaeology at Edinburgh University and the translator of this volume, introduces Cicero and his world. Berry discusses oratory in Ancient Rome, Cicero’s background and career, the Roman legal system – and how he selected the speeches for this book.

Cicero (106-43 BC) was the greatest orator of the ancient world: he dominated the Roman courts, usually appearing for the defence. His speeches are masterpieces of persuasion: compellingly written, emotionally powerful, and sometimes hilariously funny.

Cicero’s clients were rarely whiter-than-white, but so seductive is his rhetoric that the reader cannot help taking his side. In this audio guide, we are plunged into some of the most exciting courtroom dramas of all time. Listen to this audio guide to learn more.

Featured image credit: “Italy” by DomyD. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Cicero’s Defence Speeches: an audio guide appeared first on OUPblog.

Trump versus Guterres; will the new president destroy the United Nations?

With the exception of Hillary Clinton, few would have been more dismayed by Donald Trump’s surprise victory in the US presidential election than António Guterres, the former Portuguese prime minister who took over the UN Secretariat in January 2017. Other than starting a high profile job at the same time, the two share little in terms of personality or job description. Unpredictable, self-centered, and confrontational, Mr Trump who wants to put “America first“; spent his first day in office picking fights with the media about the size of the crowds attending his inauguration; and even contradicted weather reports to highlight the supposedly preternatural nature of that event.

Compare this with the self-effacing, soft-spoken, and conciliatory Mr Guterres, who in his first day at work called global peace “our goal and guide;” extolled the virtues of international cooperation; and scolded a reporter for calling him “Excellency.” While Mr Trump spent his life on corporate jets and in gold-plated towers, Mr Guterres used to take time off to teach in Lisbon’s slums. In Trump and Guterres, the nemesis of tact and finesse meets the ultimate diplomat and humanitarian. Yet while the first was handed the nuclear codes of the world’s most powerful nation, the second was put in charge of a sprawling bureaucracy and given the daunting task of preventing global conflict.

Change

Several developments—of which the US presidential election is the most significant—indicate that global order may be in the process of being undermined. Those developments include Mr Trump’s dismissal of NATO as “obsolete”; his eulogy of Brexit and his desire to see the EU breaking up; a protectionist approach to economic relations; a decision to build a ‘wall’ with Mexico; an order denying entry to Muslims while welcoming people of “Christian origins”; and statements that “torture absolutely works” and that water-boarding doesn’t go far enough. This, in Mr Trump’s first week in office.

His approach to the UN seems just as abrasive. Mr Trump has complained of the “burdensome” US commitment to the UN, has announced a 40% reduction in contributions to international organizations, and is pondering a withdrawal from the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), as well as from the Convention on the Rights of the Child. In January 2017, the American Sovereignty Restoration Act was introduced to Congress with the aim of withdrawing the US from the UN, ending all financial contributions to it, and moving the UN Headquarters out of the US.

António Guterres 2012 by Eric Bridiers. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

António Guterres 2012 by Eric Bridiers. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Continuity

These are significant developments, but are they systemic? In many ways the US has been there before: for its presidents, America has always ‘come first.’ Their multilateralism — even at its peak, with Clinton and Obama — has always been instrumental to US foreign policy and proposals to “get the US out of the UN and the UN out of the US” go back to the founding of the UN. Despite George Washington’s caveat to “steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world,” most of his successors have realized that, far from being a liability, global engagement is the most efficient way to protect (and to project) US interests. No nation benefits from the current international system more than the US — even Mr Trump’s new ambassador to the UN has conceded as much. Although the UN has changed since 1945, the US is still its most influential member and the former remains a ‘child’ of the latter, though admittedly an increasingly rebellious one.

The ambiguity of US attitudes towards multilateral organizations is another element of continuity. On the one hand, US policymakers have long understood that multilateralism — whether of Clinton’s ‘assertive’ variety or Bush Jr.’s ‘hard-headed’ one — expands rather than constrains US interests. On the other, American hegemony has often made it tempting for Washington to act unilaterally. The result is that successive US administrations have been caught between a desire to alter the international order to mould it in the US’s image, and the recognition that one country— even the most powerful — cannot change it. That the current uni-polar system of international relations might be turning into a multi-polar one as a result of the rise of other powers is as significant as Mr Trump’s win. Great powers, like great empires, don’t like to decline and rarely do it in orderly fashion. Since war in the 21st century can well turn into a nuclear Armageddon, it is the convergence of these systemic factors, with Mr Trump’s short fuse and nuclear codes, that arguably represent the gravest threat to the current international system.

The Future

History has not been kind to Mr Guterres’ predecessors, and there is no reason to think that it will be kind to him. Mr Trump’s unique blend of inexperience, aggressiveness, and populism makes him a risk to the very system that the US has contributed to build. He won’t be able to change it alone, though judging from his first week in office, he can certainly undermine his country’s reputation around the world. Just as significant as Mr Trump, however, are the factors that elevated him in the first instance, including nationalism, white nativism, and xenophobia. The fact that these are also the factors which made Brexit possible is hardly a coincidence; they threaten the very values which Mr Guterres—a former High Commissioner for Refugees—is supposed to defend. In business one can afford to slam the door and walk away. International crises of the nuclear sort make that approach more difficult — and dangerous.

Featured image credit: United Nations Flag by Etereuti. Public Domain via Pixabay

The post Trump versus Guterres; will the new president destroy the United Nations? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers