Oxford University Press's Blog, page 403

February 20, 2017

New Grub Street and the starving artist

Sitting alone in front of a computer screen, a writer sometimes feels like screaming at the machine to make the words appear. When inspiration finally strikes, the result may be far from satisfying—but when your next meal is at stake, it hardly matters.

The plight of the author hasn’t changed much since George Gissing wrote about this dilemma in his novel New Grub Street. Written in 1890 and loosely based on Gissing’s own experiences, it features a struggling writer named Edwin Reardon. Reardon must decide between writing long-form literary novels to satisfy his soul or “selling out” and writing shorter commercial fiction to provide for his wife and child.

His livelihood, reputation, and marriage all hang by a thread, dependent upon the weight of his next review. His health suffers, as does his sanity. He envies his colleagues their success, particularly the journalist Jasper Milvain, who encourages Reardon to write more commercially viable content. Despite his own near poverty, Milvain maintains the reputation of a “man about town” and finds success through his social connections writing for a magazine The Current. He vows never to write anything of solid literary value, as it would interfere with his ambition for wealth.

Gissing lets us inside a London not unlike any modern day metropolitan city. Intellectualism is respected but kept at arm’s length, while mainstream commercialism is embraced. Writers sell their possessions both prized such as books and unnecessary like clothing to keep themselves afloat. Some take up side jobs as clerks and tutors to pay the bills. At one point, Reardon muses with fellow down-and-out writer Harold Biffen that suicide may be preferable to their poor existence.

The situation in New Grub Street certainly feels familiar given that bodice rippers and celebrity self-help books frequently outsell novels destined for the Nobel or Man Booker Prize. At one point, Milvain proposes writing a book to fit a catchy title (he suggests The Weird Sisters as an example), rather than naming it after completion, but this idea fills Reardon with misery. Sensible as it seems, it would go against every principle he has.

The only difference I find between Gissing’s London and the world we live in today is the power of the critic. In Reardon’s quest for financial success, one bad review can put everything in jeopardy. Whether the book is truly a poor read is immaterial, and the risk of a bad review is high, as he has no friends among the journalists.

“Henry Welby, a notable recluse in Grub Street.” Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Henry Welby, a notable recluse in Grub Street.” Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Critics hold power in Milvain’s life as well, though for a different reason: Milvain’s plans to marry his neighbor Marian Yule and gain access to her substantial inheritance are thwarted by her father Alfred Yule because Yule, a critic himself, was slighted decades earlier by Milvain’s employer, the editor of The Current, causing a lifelong vendetta.

These days, on the other hand, a harsh review does not automatically result in commercial failure. A novel well received in The New York Times can suffer from lack of exposure on Twitter and Goodreads. However, a handful of five star reviews on Amazon can propel a critical failure into a best seller.

As Milvain flourishes, Reardon’s world crumbles. The former finds success and happiness through calculated design while the latter feels his soul ache every time he abandons his principles. Therein lies the truth that Gissing understood all too well. Pouring your heart out into pages may or may not lead to a comfortable lifestyle. Those who know the system, rub shoulders with influential people, and write with the purpose of raking in cash tend to succeed more readily.

Even today the coffee houses and tenement buildings of cities like New York, Los Angeles, and London are teeming with starving artists. Authors, screenwriters, actors, painters, dancers, musicians, etc., it always comes down to the same set of quandaries, “sell out,” or give up and get a different job, and eat well. Or, keep making the art you believe in. Because despite all the hardships, at the end of the day, it’s the one thing you can rely on to bring you fulfillment.

Featured image: “Old newspaper” by Pexels. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post New Grub Street and the starving artist appeared first on OUPblog.

A basic income for all: crazy or essential?

Shouldn’t society provide a safety net for all in modern society? The radical idea of ensuring a regular stream of cash payments to all members of society, irrespective of their willingness to work, has attracted increasing attention in recent years. Following the mobilization of a citizens’ initiative, the world’s first national referendum on basic income was held in Switzerland in 2016. While the outcome was a clear ‘no’ verdict, the debate contributed greatly to spread public awareness and discussion of the idea worldwide. Different proposals for unconditional income support have been advanced by politicians from all across the left-right spectrum. Benoît Hamon, the candidate of the socialist party in France’s 2017 presidential election, embraced basic income as one of his central proposals in the recent primaries. Finland’s centre-right government launched an ambitious two-year basic income experiment —the first of its kind in Europe— in January. There are currently plans for many other pilot projects around the world to examine the effects of unconditional forms of income support, including experiments in Canada, the Netherlands, and Kenya. Basic income is even widely supported by many libertarians as an alternative to the current welfare system in the United States.

Why? Growing socio-economic inequalities, automatization, and the precarization of labour markets, with a larger proportion of workers depending on more temporary and insecure forms of employment have provided fertile soil for basic income initiatives. In the context of mature welfare states, a universal basic income offers a potential solution to many problems—including bureaucracy traps, the exclusion of many vulnerable persons from traditional safety nets, as well as behavioural conditions and confiscatory marginal tax rates in social assistance programs that create obstacles for productive participation (in the labour market and elsewhere). By providing a firm economic foundation to which incomes from other sources can be freely added, a basic income may be particularly suitable for supporting entrepreneurship and facilitating transitions in an economy where self-employment is common, and where people are expected to be able to move in and out of jobs in flexible ways. Extending eligibility for basic income security to all, thereby avoiding any procedures or conditions that may be perceived as intrusive or stigmatizing, is a straightforward strategy to reach all persons in need and consistently prevent exploitable dependency.

The basic income proposal has a long history, with Thomas Paine’s proposal for a basic unconditional endowment in 1797 as an important forerunner to contemporary debates. However, while earlier explorations of this idea were often individual and disconnected initiatives, the growing continuity and coordination of scholarly debates on the topic have recently paved the way for a more cumulative, international research effort to shed light on this proposal. There is every reason to pay close attention to these developments. When people lack a secure foundation for independence in relation to employers, partners, or other citizens, they are vulnerable to poverty and abuse. The absence of a robust exit option makes it hard to articulate or express one’s own views with strength and confidence; it can become impossible to reject poor work conditions, protect one’s interests in personal relationships and, more broadly, interact as an equal citizen in political life.

Basic Income Performance in Bern, Oct 2013 by Stefan N Bohrer. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Basic Income Performance in Bern, Oct 2013 by Stefan N Bohrer. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Yet, basic income remains a controversial idea. Moral objections about free-riding and exploitation are legitimate political and philosophical concerns. Isn’t it unfair to provide people with something for nothing, even when they are capable of working and may be able to support themselves?

While this debate is far from settled, one of the most important replies is based on the idea that people’s life prospects should not depend fundamentally on circumstances that are entirely (or mostly) beyond their control, such as their place of birth, family background, or social connections. Following Philippe Van Parijs’s important work on this topic, the problem about the growing concentration of wealth in the hands of a few is not, perhaps, that people receive assets without any clear or deep connection to what they have done or plan to do. Rather, the problem is that these undeserved “gifts” – such as the value of natural resources, inherited capital, and, more broadly, the economic returns to the social and technological infrastructure passed on from past generations – are distributed so very unequally. From this point of view, the basic income must not be seen as an exploitative redistribution of some people’s hard-earned work income. Instead, it is a way to address the unfair distribution of resources that nobody has done anything to deserve, and to prevent that only some are allowed to reap the massive productivity gains of society’s technical progress.

Still, even if the intentions behind basic income may be justified as an effort to support equality, and provide all with their fair share, there are other important questions and objections that are more practically oriented. Is such a reform economically affordable and politically sustainable? Does it work in practice? There is an egalitarian concern that it may fail to boost the prospects of the least advantaged and, instead, erode the power of vulnerable groups and long-term political support for an ambitious welfare state. Such reservations are particularly relevant when a low basic income is advanced as a replacement (rather than a foundation) for earnings-related social insurance and measures to support the collective voice and bargaining power of disadvantaged groups. Indeed, an objective among some basic income advocates is to offer a lean, non-bureaucratic alternative to the welfare state that would allow de-regulated, competitive labour markets where state intervention and unions would play a much more limited role. However, as exemplified by Hamon’s presidential candidacy and union veteran Andy Stern’s widely discussed book Raising the Floor (2016), there has also been an increasing enthusiasm for basic income in the wider Left and labour unions lately. It seems clear that the potential of such a policy to sustainably reduce inequalities over time depends greatly on how basic income and collective strategies for empowering vulnerable workers may be fruitfully combined.

At the same time, the current wave of basic income experiments represents an empirical turn in basic income research, with a shift of emphasis from philosophical justification to concrete issues of policy design and practical evaluation. While the outcome of this maturing discussion is uncertain, any compelling response to the question of how welfare states should advance freedom and security in our rapidly changing labour markets needs to take a close look at the basic income proposal.

Featured image credit: Bank Note Euro Bills by martaposemucke. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post A basic income for all: crazy or essential? appeared first on OUPblog.

New frontiers in international law: The Asian paradox

Just over three hundred years ago, William Pitt Amherst arrived in China as Britain’s putative ambassador. A quarter century after his predecessor, Lord Macartney, had refused to kowtow to the Emperor, Amherst also made clear that he would not prostrate himself in the manner demanded by Chinese custom. Macartney at least met the Emperor; Amherst went home without even an audience.

The new frontier that China presented remained closed until it was opened by force of arms, solemnized in treaties denounced by China as unequal and marking the beginning of a century of humiliation. In other parts of Asia, international law facilitated and legitimized the colonial enterprise to expand international law and commerce to other frontiers. There were exceptions, to be sure, such as the relative acceptance of Japan as a near-equal. This appears to have been linked to its capacity to coerce other “uncivilized” states. As one Japanese diplomat was said to have observed in the early twentieth century to a European counterpart: “We show ourselves at least your equals in scientific butchery, and at once we are admitted to your council tables as civilized men.

Today, it is seen as a paradox of the international order that Asia – the most populous and economically dynamic region on the planet – arguably benefits most from the security and economic dividends provided by international law and institutions and yet is the wariest about embracing those rules and structures. Asian states are the least likely of any regional grouping to be party to most international obligations or to have representation reflecting their number and size in international organizations. There is no regional framework comparable to the African Union, the Organization of American States, or the European Union; in the United Nations, the Asia-Pacific Group of 53 states rarely adopts common positions on issues and discusses only candidacies for international posts. Such sub-regional groupings that exist within Asia have tended to coalesce around narrowly shared national interests rather than a shared identity or aspirations.

Great Wall of China by MemoryCatcher. CC0 Public Domain by Pixabay.

Great Wall of China by MemoryCatcher. CC0 Public Domain by Pixabay.In part this is due to the diversity of the continent. Indeed, the very concept of “Asia” derives from a term used in Ancient Greece rather than any indigenous political or historic roots. Regional cohesion is further complicated by the need to accommodate the great power interests of India, China, and Japan. But the limited nature of regional bodies is also consistent with a general wariness of delegating sovereignty. Asian countries, for example, have by far the lowest rate of acceptance of the compulsory jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and membership of the International Criminal Court (ICC); they are also least likely to have signed conventions such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) or the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), or to have joined the World Trade Organization (WTO). The proportion of Asian states that are contracting parties to the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) is also the lowest of any region – though on that they are tied with Latin America.

Asia’s history offers a partial explanation of the current situation, but ongoing ambivalence towards international law and institutions can also be attributed the absence of “push” factors driving greater integration or organization.

There is some evidence that this is changing, but breathless talk of a new “Eastphalian” order seems overblown. Though the status quo appears unsustainable, the major powers of Asia have made clear that their preference is for evolution rather than revolution. China’s claims in the South China Sea and the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) might suggest a desire to set up new, parallel regimes — yet closer inspection reveals that China’s claims are more traditional than first feared, and that the AIIB is clearly modeled on other international financial institutions (though with China garnering similar special privileges to the US and Europe in the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund respectively).

Asia’s rise is not, therefore, a “new frontier” in the strict sense of either word. Yet the growing importance of Asian states is suggesting the need for systemic change because the most populous and (soon) powerful region on the planet currently has the least stake in it.

Featured image credit: The Reception, by James Gillray. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post New frontiers in international law: The Asian paradox appeared first on OUPblog.

February 19, 2017

Schrödinger’s cat, aka quantum measurement problem

It’s been 116 years since Max Planck introduced the quantum idea, yet experts still disagree about quantum fundamentals. My previous post on the wave-particle duality problem argued the universe is made of fields, not particles, and that photons, electrons, and other quanta are extended bundles of field energy that often act in particle-like ways.

Here, I am proposing a solution to the measurement problem. To avoid getting lost in abstractions, I’ll illustrate it with the double-slit example. When many photons pass one at a time through the slits, the overall pattern made on the screen by the many tiny impacts is an interference pattern, implying each photon is an extended field passing through both slits.

Suppose we place a “which-slit detector” at the slits: a device that detects each photon as it comes through the slits. Such a device always detects the photon coming through just one, not both, slits. The macroscopic read-out of the detector always indicates either “slit 1” or “slit 2,” not both. This read-out is a “quantum measurement,” meaning “any process in which a quantum phenomenon (the photon coming through the slits) causes a macroscopic response (the detector registering slit 1 or 2).” The detection process causes a new pattern on the screen: rather than an interference pattern, the screen shows a simple “sum” of two single-slit patterns; each single-slit pattern is a scatter-shot distribution of individual impacts, centered directly behind one slit and falling off in intensity on both sides.

Therefore, a which-slit detector causes each photon to “collapse” from a state of going through both slits to a state of going through one or the other slit. In fact, if a which-slit detector suddenly switches on while a stream of photons passes through the slits, the screen shows a sudden transition — a quantum jump — from the two-slit interference pattern to the sum of two single-slit patterns precisely when the detector switches on.

Standard quantum theory predicts the which-slit detector causes the photon’s quantum state to “entangle” with the detector’s quantum state. Such an entangled state is subtle. Most quantum physicists interpret it as follows:

“Photon comes through slit 1 and detector reads slit 1” superposed with “photon comes through slit 2 and detector reads slit 2.”

The term “superposed with” means both situations occur simultaneously. Above, we saw a simpler example of superposition: a single photon coming through both slits with no which-slit detector present is a superposition of two states, namely “photon comes through slit 1” and “photon comes through slit 2.”

Erwin Schrödinger (1933) by the Nobel Foundation. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Erwin Schrödinger (1933) by the Nobel Foundation. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.The entangled state is odd. Erwin Schrödinger dramatized this in his famous example: A cat is connected to a Geiger counter (which detects individual radioactive decays of a nucleus) which is connected to a radioactive nucleus in such a way that, if the nucleus decays (a quantum process) the Geiger counter triggers a mechanism that kills the cat (a macroscopic response). This is a quantum measurement; theoretically, its result is the following entangled state:

“Nucleus doesn’t decay and cat lives” superposed with “nucleus decays and cat dies.”

This describes a cat that is both alive and dead! That’s impossible. This is the measurement problem.

The solution: physicists have misread entangled states. These states were poorly understood in Schrodinger’s day, but theory and experiments since 1964 have carefully dissected them. The experiments typically work with entangled photon pairs rather than a macroscopic detector such as a cat. The beauty of these experiments is that photons are easier to manipulate than cats. The experiments can manipulate each photon’s so-called “phase angle” (I won’t try to define this term here), something that’s impossible with cats.

In these experiments, each photon (call them “A” and “B”) makes a random choice between two states (call them “1” and “2”). Thus there are four possible two-photon states: (A1, B1), (A1, B2), (A2, B1), (A2, B2). It turns out that, with both phase angles set at zero, quantum theory predicts (A1, B1) is superposed with (A2, B2). If we regard A as a radioactive nucleus and B as a cat, this superposition is just the dead-and-alive cat dilemma.

But when experimenters vary the photon’s phases, something new appears: surprisingly, the states of the photons don’t vary. However, the correlations between the photons do vary. For example, suppose we set A’s phase at zero and then vary B’s phase smoothly from zero to all the way around to 180 degrees. The following table gives selected outcomes:

Phase of B (degrees)

Correlation between A and B

0

100% same, 0% different

45

71% same, 29% different

90

50% same, 50% different

135

29% same, 71% different

180

0% same, 100% different

For example, when B’s phase is 45 degrees, 71% of the outcomes are the same (both 1 or both 2) and 29% are different (if one photon is in state 1, the other is in state 2).

The table demonstrates an interference effect. Just as the simple double-slit experiment shows smooth variation from “constructive” to “destructive” as we scan across the viewing screen, the photon pair shows smooth variation from “correlated” to “anti-correlated” as we proceed from 0 to 180 degrees. This is interference, but of a different sort than in the simple double-slit experiment. It’s only the correlations between the states, not the states themselves, that are interfering. Thus neither photon is superposed. Only the correlations between the photons are superposed.

Returning to Schrodinger’s cat: the experiments show this seemingly paradoxical state is merely a superposition of different correlations between the nucleus and the cat, not a superposition of the nucleus or of the cat. The Schrodinger’s cat state should be read this way:

“An undecayed nucleus is 100% correlated with a live cat” and “a decayed nucleus is 100% correlated with a dead cat.”

Think about this. It’s totally equivalent to “the cat is alive if the nucleus is undecayed, and the cat is dead if the nucleus is decayed.” That’s not paradoxical. It’s exactly what we want. Problem solved.

Featured image credit: Brush by geralt. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Schrödinger’s cat, aka quantum measurement problem appeared first on OUPblog.

Brexit: the first many EU-exits to come?

Having made a remarkable run from the 1950s to the early 2000s, the project of European unification suddenly appears in danger of falling apart. After Brexit, the surprise British vote of June 2016 to leave the European Union, will there be other EU Exits was well?

A Grexit nearly took place in the summer of 2015—avoided only after weeks of acrimonious negotiations between Greek and EU leaders. In the end, the heavily indebted Greeks received a new package of loans, but at a steep economic and political price: a leftwing Greek government that had vowed never to accept new austerity measures did just that. The Grexit drama is far from over.

Meanwhile, a potential Frexit looms. Marine Le Pen, the leader of France’s far-right National Front, is likely to be one of the two candidates competing the final round of the presidential election this spring. If she is elected President of the Republic, a distinct possibility in this season of populist success, she could lead France out of the European Union. (Le Pen was photographed at Trump Tower in mid-January.) According to a recent Pew Research poll, more than 60% of the French people have negative views of the EU.

Elsewhere, other Eurosceptic parties are on the march. They’re fueled by opposition to immigration—especially from Muslim countries—by a persistent economic malaise, and by the uneven effects of globalization and Europeanization, which have cost blue-collar jobs. Although the Netherlands has no explicitly anti-EU party, the extremist Party of Freedom could exploit the strong EU skepticism of the Dutch public, more than half of which have expressed the desire for a referendum on a potential Nethexit.

In Austria, the extreme rightwing, anti-EU Norbert Hofer came within 0.6% of winning the presidential election in April 2016. The result was so close and the vote-counting so sloppy that the courts ordered the election to be re-run. This time (December 2016), Alexander Van der Bellen, the pro-EU candidate, won decisively. It’s not impossible that the election of Donald Trump a month earlier had helped put Van der Bellen over the top. Austria’s mainstream electorate saw from the American election just how successful hard-edge populism could be and voted in larger numbers this time. Still, Hofer received 46% of the vote, having won just under 50% the previous April. Neither result bodes well for the EU’s future: an Austrexit could be on the horizon.

Virginia Raggi after the first round of Rome local elections in June 2016 by Movimento 5 Stelle. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikmedia Commons.

Virginia Raggi after the first round of Rome local elections in June 2016 by Movimento 5 Stelle. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikmedia Commons.The country that has raised the most immediate Exit concerns is Italy, where the centrist coalition government lost a December 2016 referendum intended to make Italy’s political system more functional. Although the referendum didn’t explicitly refer to the EU, the strong negative vote was widely seen as a rejection of a political establishment closely identified with the European project, of which Italy was a founding member.

Anti-establishment the election may have been, but it seems unlikely to produce an Itexit—or is it Italexit? Prime Minister Metteo Renzi’s opponents on the right and left saw the referendum as a power grab by Italy’s central government, an attempt to deprive Italy’s traditionally important regions of their authority. Members of Italy’s two houses of parliament understood the vote in similar terms. But these sentiments, powerful as they are, don’t translate into a widespread desire in Italy to leave the EU. The far-right Northern League, with just 12% of the vote, stands alone among Italy’s major parties in calling for an Itexit.

Italy’s second biggest vote-getter, the anti-establishment Five Star Movement (M5S), founded in 2009 by a comedian and an IT guru, is skeptical of the EU but expresses no intention to lead Italy out the door. The EU, says the M5S, is corrupt and undemocratic, and it has failed to nurture the Italian economy. But the movement’s goal seems to be to reform the EU, not to abolish it. It may, however, seek to dismiss the euro in favor of the lira, Italy’s traditional currency. The M5S now has the support of about 30% of Italy’s voters, and most of them say in opinion polls that they want to remain in Europe. Italians seem less enamored of the Eurozone, which deprives member states of control over their monetary policy and thus straitjackets them in the face of economic recession.

Although the M5S has won recent mayoral elections in Rome and Turin, long a stronghold of the left, it’s by no means a given that it can win a national election; Rome’s M5S mayor Virginia Raggi has made a hash of her tenure so far. But if her party ultimately succeeds at the national level, it could put some salutary pressure on the EU, which needs to reform its sclerotic bureaucracy and address the economic needs of southern European countries struggling with soaring debt, high unemployment, and low growth. Brexit has done little for EU reform and perhaps has made it less likely. Eurosceptics in Italy could have a more positive effect.

Featured image credit: leuchtkasten shield output by geralt. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Brexit: the first many EU-exits to come? appeared first on OUPblog.

The many voices of Dickens

Charles Dickens’s reputation as a novelist and as the creator of Ebenezer Scrooge, one of the most globally recognized Christmas miser figures, has secured him what looks to be a permanent place in the established literary canon. Students, scholars, and fans of Dickens may be surprised to learn that the voice many Victorians knew as “Dickens,” especially at Christmastime, was also the voice of nearly forty other people. Over an eighteen-year span at the height of his career, Dickens was a collaborator whose creative voice was in conversation with a host of others.

From 1850-1867, Dickens produced special issues, or numbers, of his journals Household Words and All the Year Round that were released shortly before Christmas. For each one, Dickens collected mostly fictional prose and verse from colleagues, and for most, he wove the pieces into a frame concept or story he devised (only the first two collections lacked a frame concept or narrative). As the “Conductor” of each issue, Dickens not only led the talented artists he assembled but also relied on them for a successful finished project. Sometimes, he provided contributors with parameters for the stories, but those letters were usually broad in scope and did not specify subjects or themes. Most of the writers who sent in stories did not meet in person with the others, although the contributors who lived in London or worked at Dickens’s journals, like Wilkie Collins or Dickens’s co-editor W.H. Wills, would have been in contact with him and with each other regularly. The resulting Christmas collections are far flung in scope, topic, and tone, and they rarely focus on Christmas itself. Instead, they feature ghost stories, tales of murder, and travel adventures with narrative voices and protagonists mixing together in complicated storytelling webs. The “Dickens” of the Christmas numbers existed as a multiplicity of voices, resulting in a highly variable authorial presence and a Dickens who was much more flexible than most people presume.

For A Round of Stories by the Christmas Fire (1852), W. H. Wills appears to have decided on the final ordering of the stories, which impacts how each one relates to the others and to the frame apparatus. For Another Round of Stories by the Christmas Fire (1853), Dickens’s letters indicate that he again trusted Wills to tend to the ordering of the number and other important editorial matters. In these collections, Dickens’s voice at times mixes with the narrative and authorial voices of writers like Elizabeth Gaskell, whose “The Old Nurse’s Story” became a highly anthologized example of the Gothic mode; George Augustus Sala, who also wrote pornography; Wilkie Collins, an innovator of detective fiction and the author with whom Dickens collaborated most closely; and Eliza Griffiths, an almost anonymous contributor whose biographical details remain a mystery.

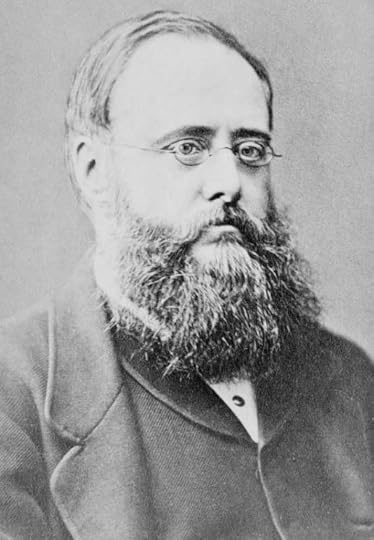

Portrait of British writer Wilkie Collins, 1871. Elliott and Fry, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of British writer Wilkie Collins, 1871. Elliott and Fry, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.In this aspect of his editorial and authorial life, Dickens was often less autocratic and bullying than scholar have recognized. He wrote less than a full third of the total amount of prose and verse in the Christmas numbers, and he often didn’t get his way. Dickens printed endings he did not like under his own name, asked another person to co-write more than one frame story, allowed yet another person to decide upon the ordering of stories, and included a poem that approves of cannibalism in stark contrast to his own other published work on the subject. As often as Dickens is defensive or controlling, he is playful and self-conscious about the collaborative dynamics between himself and his contributors. In the case of The Perils of Certain English Prisoners, Dickens and Wilkie Collins simultaneously occupy the positions of male writers, the woman writer who is the scribe for the story, and the illiterate man who speaks the story. Comfortably leaving the position of individual writer and agent, these two highly successful (and famous) novel writers move together into a much more ambiguous authorial role. Tom Tiddler’s Ground (1861) is based on an excursion that blurs the boundary between Dickens’s real and fictional personas, as does the some of the editor/contributor ribbing in The Haunted House (1859). In A Message From the Sea (1860) and Tom Tiddler’s Ground (1861), the value of storytelling itself is even up for debate, threatening to undermine the whole project.

The Victorians navigated these unstable, challenging concepts of authorship quite deftly. Victorian readers would know that Dickens wrote some but not all of the pieces in the collections he “Conducted,” and they were perhaps less preoccupied with modern investments in the myth of the lone genius than present-day readers. Rediscovering the Christmas numbers in their entireties, reading all of the stories together instead of isolating the ones by Dickens, leads to a multi-layered, multi-voiced experience of Dickens that revitalizes the textual conversations he sparked with other impressive writers. As the 205th anniversary of Dickens’s birth approaches and we continue to consider his body of work, we will do well to remember that some of his most intriguing collections were not his alone.

Featured image credit: title page from the first edition of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, 1843. Illustration by John Leech, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The many voices of Dickens appeared first on OUPblog.

The real National Treasure: US presidential libraries

I’ve watched the film National Treasure twenty more times than I probably needed to, but I can’t ignore my fascination with the history of the US presidents. In the movie, the directors place a strong emphasis on the importance of historical documents and artifacts, and a working knowledge of the importance and content of these items, to help the main protagonists complete a centuries-long treasure hunt. And it led me to wonder: where are these documents now? Who has access to them, and what is the public allowed, and not allowed, to see?

For queries of this kind, I inevitably turned to the one place with all the answers: the library. But not just any library. In honor of Presidents’ Day on 20 February, I interviewed Melissa Giller, Chief Marketing Officer for the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Institute in Simi Valley, California, and Alan Lowe, Executive Director of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, Illinois, to learn more about these institutions’ contents, purpose, and significance in the library community.

Who actually builds them?

“So it’s a bit different based on each library,” explained Alan Lowe. Most presidential libraries constructed from Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s time in office to the upcoming Barack Obama Presidential Library in Chicago are built and run by the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

But other libraries, such as the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, are sometimes created by the state—in this case, the state of Illinois—and often begin as historical state libraries or museums that combine with or expand into presidential libraries. Such is the case with the Lincoln library. Additionally, some are run by other institutions, such as the Ulysses S. Grant Presidential Library in Mississippi, run by Mississippi State University.

Plans to build the library begin about two years prior to the president leaving office. With more recent libraries, the president for whom the library is built involves himself heavily in the planning, design, and curation of the building. This was especially true for George H. W. Bush’s library, where both he and Mrs Bush played an active role in the creation of the library. “They were on site a lot,” says Lowe, who worked at the George H. W. Bush Presidential Library in Dallas, Texas before coming to the Lincoln library, “and it was extraordinarily helpful. Who wouldn’t want the former president to be there when designing the library dedicated to him and his time in office?”

Though Abraham Lincoln was obviously not present for the creation of his library, built a little over 11 years ago, the library strives to preserve his memory in both form and function.

Photo of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. “Museum Night (2)” photo by Hannah Ross. Used with permission.

Photo of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. “Museum Night (2)” photo by Hannah Ross. Used with permission.Why are they built?

“The presidency is an important institution in this country and to the rest of the world, and we need to tell the story of the men who occupied that office,” says Lowe.

These libraries not only preserve the raw materials that constitute our nation’s history, but also teach those who visit about the tumultuous course our nation and its people have endured. Presidential libraries engage patrons by offering educational speakers and programs at the library, and positioning themselves as active cultural institutions that become part of the local community.

And their wealth of knowledge extends far beyond the reign of any one president. “The Library and Museum are a reflection of the president’s life,” Giller tells me, “not just the presidency, but their whole life.”

The Ronald Reagan Library showcases several large, special exhibits—at least two per year—that bring visitors into the library. “We do this to be a resource for our community—to be more than a presidential library,” Giller notes. “For example, we have brought in exhibitions on Abraham Lincoln, the Cold War, the Vatican, and even baseball.”

What’s really inside these libraries?

“A presidential library is actually two things,” Giller describes. “It’s a museum that anyone can come and visit and tour through…and it is a library.” The library is, more often than not, the private side of the establishment, where the archives are held. The curation is for the actual museum. The museum covers the president’s life before becoming president, his time during office, post-administration, and if the president is deceased, then any history related to him after his death.

At the Abraham Lincoln Library and Museum, one might be so lucky to catch a glimpse of certain famous historical artifacts, such as a handwritten copy of the Gettysburg address in Lincoln’s handwriting, an original printing of the Emancipation Proclamation signed by Lincoln, a copy of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, the bloody gloves Lincoln wore the night he was assassinated, and the stove pipe hat he wore, “where you can still see the thumb print on it from when he would tip his hat to people,” Lowe informs me.

“So in terms of what goes into our library versus a private library…you can’t compare,” Giller says of the Ronald Reagan President Library. “We don’t have books on display.”

At Lincoln, they have a permanent exhibit and special exhibit, and it takes time to determine which artifacts to show in each section. Since many of their pieces no longer contain information that could be a threat to national security, their primary concern with these items is conservation and the ability to streamline the research process for those using these artifacts as evidential or study materials.

“My main goal since I got here,” Lowe declared, “is making sure we have the right research rooms set up to help researchers and educators to get the most out of their time here.”

Photo of the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library. Photo “reagan campus6” courtesy of The Reagan Foundation. Used with permission.

Photo of the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library. Photo “reagan campus6” courtesy of The Reagan Foundation. Used with permission.Who can access this content, who cannot, and why?

Several documents are closed for national security, but as a researcher, an individual can still say he or she wants to see a certain document due to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), and then an archivist takes document and determines who has interest in classification status of document. This person then makes an appointment with the archives department to visit the Research Library, and if the documents get cleared for use, the author would sit in the research room and the archivist would bring them the papers, documents, or photos they needed to see.

Any person, whether a United States citizen or not, can make a FOIA request, but just because the request is made does not mean it will be granted.

There are exceptions to this rule, however. Highly classified documents or artifacts may not be accessed even after the individual exercises their right to the FOIA, due to matters of national security, or if the documents are deemed classified by certain organizations, such as the CIA.

Otherwise, the artifacts and documents on display for the general public are available for anyone to view on a trip to the library and museum.

Why do we need presidential libraries?

“Presidential libraries become a part of history,” Giller explains, “It’s a way for visitors to see items from the various presidencies up close—to learn more about the person behind the president.”

Lowe agrees, adding that “it’s all in the eye of the beholder, how you classify a presidential library, and why you need them,” Lowe says, “but I like to classify them by three categories: do they have the museum component, do they have educational and public programs, and do they have collections?”

There is also an economic impact created by these institutions. They are a great provider of jobs and income, Lowe informs me, and many cities report having a positive economic impact when presidential library built.

“These institutions are so unique,” Lowe emphasizes, “and each institution takes on the flavor of its community and of its president.”

If you house all these documents in a warehouse in some central location, say Washington DC, he says, you lose half of the educational component to the libraries. At the Lincoln library, because it resides where Lincoln himself once did, anyone can read a document about his house, and then walk right to where Lincoln lived in no time. “It feels like Lincoln is still walking the streets here because the library is so centric to the city.”

Presidential libraries serve to encapsulate the historic, economic, and potentially personal impact each president has made on the United States as a nation and the people who call it home. Without these libraries, a piece of history might be lost, or even worse, forgotten.

Featured image credit: Photo “NationalTreasureFilmSet (1)” by Sean Devine. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The real National Treasure: US presidential libraries appeared first on OUPblog.

Graphs and paradoxes

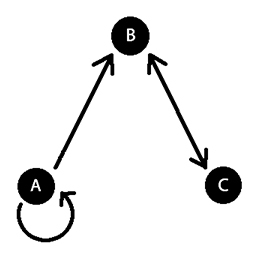

A directed graph is a pair <N, E> where N is any collection or set of objects (the nodes of the graph) and E is a relation on N (the edges). Intuitively speaking, we can think of a directed graph in terms of a dot-and-arrow diagram, where the nodes are represented as dots, and the edges are represented as arrows. For example, in the following figure we have a graph that consists of three nodes–A, B, and C, and four edges: one from A to A, one from A to B, one from B to C, and one from C to B.

Image courtesy of author.

Image courtesy of author.Note that with directed graphs we distinguish between those cases where a node has an arrow from itself to itself and those cases where it does not, and we also take into account the direction of the edge–that is, the edge from B to C is distinct from the edge from C to B (we do, however, represent cases where we have arrows going in both directions with a single line with two “arrowheads”).

In the diagram above, the nodes might represent Alice, Betty, and Carla, and the relation E might be “loves.” Thus, the diagram represents Alice loving both herself and Betty (and no one else), Betty loving Carla (and no one else), and Carla loving Betty (and no one else).

Assume we have a collection of objects N (our nodes) and a relation E such that for any two objects in N, the relation E might or might not hold of them, and in particular, E might or might not hold between an object in N and itself. Now, consider the graph where the collection of nodes is N and the collection of edges (which we will also call E) contains an edge between two nodes n1 and n2 just in case the relation E holds between n1 and n2 (in that order). Now, given any such structure, we can arrive at our puzzle by considering the following question:

Given such a situation, modelled by a directed graph <N, E>, can we construct a new directed graph <N*, E*> where N* = N È {r} (where r is not already in N) and, for any n1, n2 in N*, there is an edge in E between n1 and n2 if and only if:

n1, n2 are in N and there is an edge in E between n1 and n2.

n1 = r and there is no edge between n2 and itself.

In other words, given any directed graph, can we add a single additional node to the graph, and some additional edges to the graph, such that there is an edge between the new node r and any node n in N* if and only if there is no edge from n to itself?

The answer, of course, is no. If we were successful, then we would have a directed graph <N*, E*> where:

For any n in N*, there is an edge in E*from r to n if and only if there is no edge in E* from n to n.

Substituting r for n gives us a contradiction, however:

There is an edge in E* from r to r if and only if there is no edge in E* from r to r.

This pattern is a general one underlying a number of paradoxes – some familiar, some less so. For example:

The Barber Paradox:

N = the collection of men and there is an edge between two nodes n1 and n2 if and only if n1 shaves n2. The new node r is the barber who shaves all and only those who do not shave themselves.

The Russell Paradox:

N = the collection of sets and there is an edge between two nodes n1 and n2 if and only if n2 is a member of n1. The new node r is the set of all sets that are not members of themselves.

The Impossible Painting Paradox:

N = the collection of painting and there is an edge between two nodes n1 and n2 if and only if n1 is a painting that depicts n2. The new node r is the painting that depicts all and only those paintings that do not depict themselves.

The Hyperlink Paradox:

N = the collection of websites and there is an edge between two nodes n1 and n2 if and only if n1 hyperlinks to n2. The new node r is the website that links to all and only those websites that do not link to themselves.

The Lover of Self-loathers Paradox:

N = the collection of people and there is an edge between two nodes n1 and n2 if and only if n1 loves n2. The new node r is the lover of self-loathers – a person who loves all and only those people who do not love themselves.

The Anti-Cannibalism Predator Paradox:

N = the collection of species, there is an edge between two nodes n1 and n2 if and only if members of species n1 eat members of n2. The new node r is the anti-cannibal predator species, members of which eat all and only members of those species that don’t eat members of their own species.

The Hyperlink Paradox is, as far as I can tell, due to Øystein Linnebo, and the Lover of Self-Loathers Paradox and the Anti-Cannibalism Predator Paradox are new. Now that you’ve seen the pattern, you can have fun constructing your own paradoxical notions!

Featured image: Partial view of the Mandelbrot set by Wolfgang Beyer. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Graphs and paradoxes appeared first on OUPblog.

February 18, 2017

Alan Turing’s lost notebook

Alan Turing’s personal mathematical notebook went on display a few days ago at Bletchley Park near London, the European headquarters of the Allied codebreaking operation in World War II. Until now, the notebook has been seen by few — not even scholars specializing in Turing’s work. It is on loan from its current owner, who acquired it in 2015 at a New York auction for over one million dollars.

The yellowing notebook — from Metcalfe and Son, just along the street from Turing’s rooms at King’s College in Cambridge — contains 39 pages in his handwriting. The auction catalogue (which inconsequentially inflated the page count) gave this description:

“Hitherto unknown wartime manuscript of the utmost rarity, consisting of 56 pages of mathematical notes by Alan Turing, likely the only extensive holograph manuscript by him in existence.”

A question uppermost in the minds of Turing fans will be whether the notebook gives new information about his famous code-cracking breakthroughs at Bletchley Park, or about the speech-enciphering device named “Delilah” that he invented later in the war at nearby Hanslope Park. The answer may disappoint. Although most probably written during the war, the notebook has no significant connection with Turing’s work for military intelligence. Nevertheless it makes fascinating reading: Turing titled it “Notes on Notations” and it consists of his commentaries on the symbolisms advocated by leading figures of twentieth century mathematics.

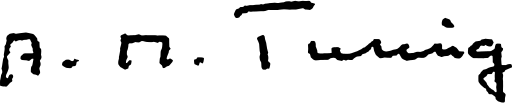

Alan Turing’s signature. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Alan Turing’s signature. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.My interest in the notebook was first piqued more than 20 years ago. This was during a visit to Turing’s friend Robin Gandy, an amiable and irreverent mathematical logician. In 1944-5 Gandy and Turing had worked in the same Nissen hut at Hanslope Park. Gandy remembered thinking Turing austere at first, but soon found him enchanting — he discovered that Turing liked parties and was a little vain about his clothes and appearance. As we sat chatting in his house in Oxford, Gandy mentioned that upstairs he had one of Turing’s notebooks. For a moment I thought he was going to show it to me, but he added mysteriously that it contained some private notes of his own.

In his will Turing left all his mathematical papers to Gandy, who eventually passed them on to King’s College library — but not the notebook, which he kept with him up till his death in 1995. Subsequently the notebook passed into unknown hands, until its reappearance in 2015. Gandy’s private notes turned out to be a dream diary. During the summer and autumn of 1956, two years after Turing’s death, he had filled 33 blank pages in the center of the notebook with his own handwriting. What he said there was indeed personal.

Only a few years before Gandy wrote down these dreams and his autobiographical notes relating to them, Turing had been put on trial for being gay. Gandy began his concealed dream diary: “It seems a suitable disguise to write in between these notes of Alan’s on notation; but possibly a little sinister; a dead father figure and some of his thoughts which I most completely inherited.”

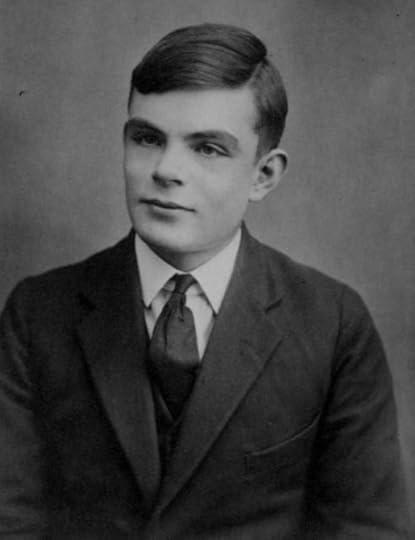

Alan Turing, aged 16 by unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Alan Turing, aged 16 by unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Mathematical reformer

Turing’s own writings in the notebook are entirely mathematical, forming a critical commentary on the notational practices of a number of famous mathematicians, including Courant, Eisenhart, Hilbert, Peano, Titchmarsh, Weyl, and others. Notation is an important matter to mathematicians. As Alfred North Whitehead — one of the founders of modern mathematical logic — said in his 1911 essay “The Symbolism of Mathematics”, a good notation “represents an analysis of the ideas of the subject and an almost pictorial representation of their relations to each other”. “By relieving the brain of all unnecessary work”, Whitehead remarked, “a good notation sets it free to concentrate on more advanced problems”. In a wartime typescript titled “The Reform of Mathematical Notation and Phraseology” Turing said that an ill-considered notation was a “handicap” that could create “trouble”; it could even lead to “a most unfortunate psychological effect”, namely a tendency “to suspect the soundness of our [mathematical] arguments all the time”.

This typescript, which according to Gandy was written at Hanslope Park in 1944 or 1945, provides a context for Turing’s notebook. In the typescript Turing proposed what he called a “programme” for “the reform of mathematical notation”. Based on mathematical logic, his programme would, he said, “help the mathematicians to improve their notations and phraseology, which are at present exceedingly unsystematic”. Turing’s programme called for “An extensive examination of current mathematical … books and papers with a view to listing all commonly used forms of notation”, together with an “[e]xamination of these notations to discover what they really mean”. His “Notes on Notations” formed part of this extensive investigation.

Key to Turing’s proposed reforms was what mathematical logicians call the “theory of types”. This reflects the commonsensical idea that numbers and bananas, for example, are entities of different types: there are things which makes sense to say about a number — e.g. that it has a unique prime factorization — that cannot meaningfully be said of a banana. In emphasizing the importance of type theory for day-to-day mathematics, Turing was as usual ahead of his time. Today, virtually every computer programming language incorporates type-based distinctions.

Link to the real Turing

Turing never displayed much respect for status and — despite the eminence of the mathematicians whose notations he was discussing — his tone in “Notes on Notations” is far from deferential. “I don’t like this” he wrote at one point, and at another “this is too subtle and makes an inconvenient definition”. His criticisms bristle with phrases like “there is obscurity”, “rather abortive”, “ugly”, “confusing”, and “somewhat to be deplored”. There is nothing quite like this blunt candor to be found elsewhere in Turing’s writings; and with these phrases we perhaps get a sense of what it would have been like to sit in his Cambridge study listening to him. This scruffy notebook gives us the plain unvarnished Turing.

Featured image credit: Enigma by Tomasz_Mikolajczyk. CC0 Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Alan Turing’s lost notebook appeared first on OUPblog.

[image error]

Reckoning with the addict and the US “War on Drugs”

In 2015, nearly 1.25 million people in the United States were arrested for the simple possession of drugs. Moreover, America’s “War on Drugs” has led to unprecedented violence and instability in Mexico and other drug-producing nations. Yet in spite of billions of dollars spent and thousands of lives lost, drug abuse has not decreased.

The stigma of the addict has remained tried-and-true for decades, even centuries, and it affects every proposed solution to eliminating drug abuse and the drug trade, from treatment models to aggressive drug enforcement measures. With the solidification of the punitive drug control system in the 1970s and 1980s, years of stigmatizing individuals’ dependencies to substances like cocaine, derivatives of the poppy plant, and alcohol reached its logical conclusion: the addict was cast as a criminal. But if the stigma of the addict were removed altogether, many fear that drug addiction would increase to the overall detriment of society.

With the drug war concept growing increasingly unpopular, treatment policies have been touted as the next frontier in reducing drug abuse and crippling the drug trade. However, the success of treatment policies is more than simply discarding the “War on Drugs”. It’s reckoning with the addict. If the treatment approach is to achieve widespread success, we must minimize our stigma of the addict in conjunction with creating more viable rehabilitative options that can successfully displace punitive drug control measures.

A look at how American society has stigmatized the addict over the last 100 years reveals how much work remains to be done.

Drug addicts have gone to great lengths—monetarily, physically, emotionally, etc.—to cure themselves of myriad addictions. In the 1930s, an experimental treatment known as the “serum cure” used heat plasters to raise blisters on the addict’s skin. Upon withdrawing the serum from the blisters, the administers of the treatment then re-injected the serum directly into the addict’s muscles multiple times over the course of the week that followed. “Remarkable results” were claimed from the serum cure.

Other “miracle cures” included horse blood injections, the infamous Keeley Cure, which introduced a substance into the body that allegedly contained gold, and placing the excrement of animals into substances like alcohol to induce aversion to them.

The question now is not whether we can fund more treatment programs to reduce drug addiction and move past the “War on Drugs,” but whether or not we discard the stigma of the addict, which undergirds any solution to drug abuse in our society.

Those who did not turn to vogue, experimental treatments often resorted to substituting one substance addiction for another: cocaine for morphine or morphine for alcohol. It all depended upon which substance society deemed the more undesirable at the time.

At one point, the stigmatization of the addict proved so intense that some resorted to sterilization, especially in the age of eugenics. Addicts, as it went, did not have the right to pass on their undesirable addictions to their offspring or to society at large.

While the personal cost of such remedies was high for the addict, it was by no means as costly as enduring the sense of shame that came with being an addict in US society.

While today’s addict is more likely to undergo a stay in a treatment facility, a prison, or on the street rather than an unusual, experimental cure, the stigma of the addict remains as sharp as ever, so much so that it prevents treatment resources from being made available to a greater portion of the population. It discourages addicts from seeking the help they need.

According to the most recent National Survey on Drug Use and Health, only 14% of people struggling with drug dependency seek treatment. Treatment implies accepting the status as addict in the path to recovery, a step that for some is too gruesome to endure.

Contrary to popular belief, many of the architects of the US “War on Drugs” were politicians to drug abuse. The US anti-drug campaign was not initially intended to be a “war” per se, but instead an incredible mobilization of US resources to target widespread drug use in the 1960s and 1970s, a period wracked by civil unrest and opposition to authority figures.

But ultimately the desire to minimize crime overtook an increased focus on treatment. Mistakenly, drug control came to be associated with increasing numbers of non-white, lower class drug addicts—already undesirables. Soon the larger umbrella of crime prevention subsumed drug addicts, many who might have been successfully rehabilitated if the conditions proved more favorable. Tackling addiction then grew increasingly intertwined with making US cities and towns safer.

In time, leaders would mobilize supply control measures domestically and abroad, and soon an entire bureaucracy formed around criminalized drug control where the addict was the criminal. Those who advocated genuine treatment options from the 1970s onward fought a losing battle. This made sense given longer traditions of stigmatizing addicts and the intense pressures addicts faced to overcome their dependencies.

The question now is not whether we can fund more treatment programs to reduce drug addiction and move past the “War on Drugs,” but whether or not we discard the stigma of the addict, which undergirds any solution to drug abuse in our society. With drug control in the United States an inherently racialized, class-based phenomenon, it’s easier to stigmatize and blame than it is to rehabilitate.

While increasingly sophisticated treatment options and facilities have developed over time, our society is not yet in a position where we embrace our addicts, especially those of lower classes, races, and ethnicities. Although blacks and Latinos use and sell drugs at similar or lower rates to whites, they comprise nearly 60% of those being held for drug offenses at state prisons. “Nothing has contributed more to the systematic mass incarceration of people of color in the United States than the War on Drugs,” according to Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow.

As it stands, drug control fluctuates between two extremes: “addiction as crime” versus “addiction as disease.” For most of our recent history, we have subscribed to the former position. Treatment programs on a mass scale should be carefully constructed so that they promote the recuperating addict and his or her recovery post-addiction in a less stigmatizing environment. We must give addicts a second chance to be full citizens in our society capable of making a fresh start.

Perhaps the first step involves supporting campaigns that popularize the notion of seeing addiction as a disease through events and social media, such as National Recovery Month each September. Supporters of this cause offer support to addicts and their families and celebrate recovery. Could such awareness, if it grows powerful enough, then serve to inspire more aggressive political action?

In whatever direction we proceed, we must find a way to reckon with the stigma of the addict, an effort that has to be more powerful than the inclination to see the addict as a criminal.

Featured image credit: “Chainlink” by Unsplash. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Reckoning with the addict and the US “War on Drugs” appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers