Oxford University Press's Blog, page 401

February 24, 2017

A library in letters: the Bodleian

Libraries by their very nature are keepers and extollers of the written word. They contain books, letters, and manuscripts, signifying unending possibilities and limitless stores of knowledge waiting to be explored. But aside from the texts and stories kept within libraries’ walls, they also have a long and fascinating story in their own right. In light of this contrast between the physical store of narratives, and the generally hidden life and narrative(s) of the library itself—what can letters about libraries tell us about the ways these spaces are used, and what makes them so special?

We’ve delved into private correspondence on our very own Bodleian Library here in Oxford, to find out why it’s inspired so many generations of academics, students, and writers. From the inspirational and the aspirational, with discussions of bequests, royalty, and scandals, to the mundane but ever-necessary issues of building work and heating—discover a library in letters…

First opened in 1602, the Bodleian is one of the oldest and most respected libraries in Europe. Reflecting the high esteem in which its collections were held, in 1703 John Locke (one of the most influential Enlightenment thinkers) wrote to John Hudson (librarian from 1701 to 1719) offering to donate his works in the hope that his texts would “have a place among their betters”:

Since the high opinion you express of my writings above what they deserve, and your demand of them for the Bodleian library will now authorise that vanity in me, it is my intention if the booksellers fail in sending them to make a present of them to the University myself and put them into your hands to that purpose since you are so favourable to them as to think them fit to have a place among their betters.

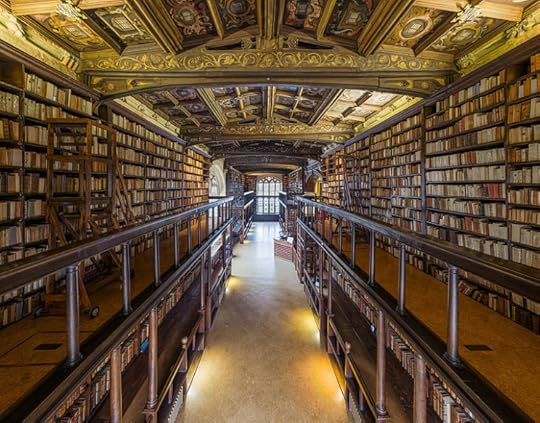

“The interior of Duke Humphrey’s Library, the oldest reading room of the Bodleian Library in the University of Oxford” by David Iliff, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“The interior of Duke Humphrey’s Library, the oldest reading room of the Bodleian Library in the University of Oxford” by David Iliff, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Not everyone was as enamoured with the Bodleian as John Locke, however. In 1766, Thomas Warton (an English poet and historian) wrote to Jackson’s Oxford Journal, complaining that his Oxfordian ancestors “seem to have had very little notion of elegance, convenience, and propriety” when it came to architectural beauty. The library did not escape his notice, suggesting that:

The pinnacles on the top of the schools, those superfluous and cumbersome remains of an ignorant age, were taken and down, and replaced by Roman urns: which, besides the effect they would have on the whole building, would add a more fashionable and airy appearance to that one side of the Radclivian area.

Aside from the architecture, Warton also complained in 1785 of being too cold to work: “The weather has been too severe for writing in the Bodleian Library, where no fire is allowed.”

Libraries were unheated in the eighteenth century because fires were so hazardous. Even today, the oath which all scholars have to take promises “not to bring into the Library, or kindle therein, any fire or flame, and not to smoke in the Library.” Despite the often chilly conditions, the Bodleian hosted the highest echelons of royalty, with Hester Lynch Piozzi (a diarist and patron of the arts) recalling a near-disastrous visit of King Louis XVIII:

Our Bishop Cleaver was the man appointed to show Oxford to Louis XVIII of France: he commends the King’s scholarship and good breeding extremely; but how odd it was, that when they opened a Virgil in the Bodleian, the first line presenting itself should be, ‘Quæ regio in terris, nostri non plena laboris’ (‘Is there a land in the world not steeped in our troubles and sorrow?’) ‘Ah! monseigneur,’ cried Louis Dixhuit, ‘fermons vite, j’ai eu assez de ça‘ (‘Close it now, I’ve had enough of that’). “Why, my lord,” said I, “were you seeking the Sortes Virgilianæ on purpose?” “No,” replied he, “nor ever thought of it.”

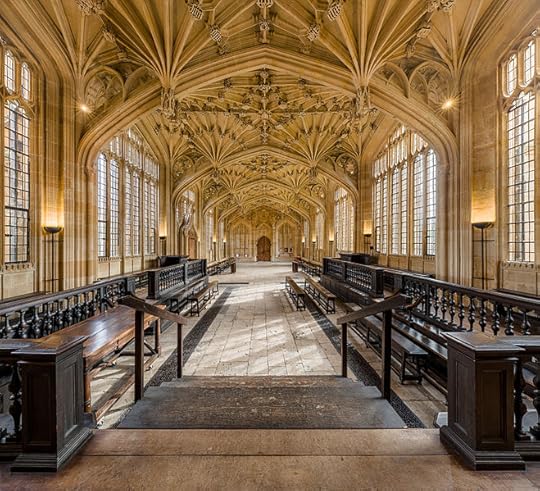

“Looking east in the interior of the Divinity School in the Bodleian Library” by David Iliff, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“Looking east in the interior of the Divinity School in the Bodleian Library” by David Iliff, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Piozzi herself was also “entertained” by the enormous stores within the library’s walls, writing to her daughter on the arrival of a shipment of one thousand pounds of “Modern Books” that: “I thought myself transported by Magic from the Bodleian Library where Mr Gray had entertained me for whole Hours and Days, and whence I came to my Maid all covered with Dust.”

Despite the seeming tranquility of the Bodleian’s books, the library was no stranger to scandals, with Charles Clairmont (a member of the Shelley-Byron circle) noting how he followed in the footsteps of Thomas Jefferson Hogg and Percy Bysshe Shelley, who were expelled from the University in 1811 for their role in printing and distributing Shelley’s pamphlet The Necessity of Atheism:

We visited the very rooms where the two noted Infidels Shelley and Hogg […] poured with the incessant and unwearied application of an Alchemyst over the artificial and natural boundaries of human knowledge; brooded over the perceptions which were the offspring of their villainous and impudent penetration and even dared to threaten the World with the horrid and diabolical project of telling mankind to open its eye.

Whether it’s outrage, scandal, passion, or down-right dissatisfaction, plainly evident in all these letters is the crucial importance of the library, its building, books, and opportunities, to all who used and continue to use it. Long live the library, and its letters!

Featured image credit: “Oxford University, Radcliffe Camera, a Reading room of Bodleian library” by Tejvan Pettinger, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A library in letters: the Bodleian appeared first on OUPblog.

Conscious unity, split perception

We take it for granted that our entire brain only produces one conscious agent, despite the fact that the brain actually consists of many different, more or less independent modules. But how is this possible?

The classic answer to this riddle is cortical connectivity. Separate brain regions only give rise to one conscious agent because the different parts continuously exchange massive amounts of information. This serves as the cornerstone of two current leading theories on consciousness: the Global Workspace Theory, and the Information Integration Theory. Both theories assert that once cortical connectivity between brain parts breaks down, the brain no longer gives rise to only one conscious agent. On the contrary, the theories assert that in such a scenario, each part would create an independent conscious agent.

This is an interesting philosophical thought experiment, but obviously it is hard to conduct experiments in real life where cortical connectivity is severely disrupted just to test our ideas about consciousness. However, starting in the 1940s, some patients suffering from intractable epileptic seizures have been treated by surgically severing the corpus callosum. As a result, communication between the left and the right cerebral hemisphere ground to a halt (and seizures had less chance to propagate through the brain). These split-brain patients provide the ideal testing ground for the role of cortical connectivity in consciousness. If cortical connectivity is the key, then conscious unity should break down in split-brain patients, resulting in two independent conscious agents (one per cerebral hemisphere). Indeed, numerous reports have confirmed this. Although the patients feel normal, and behave normally in social settings, controlled lab tests reveal the following: when an image is presented to the left visual field, the patient indicates verbally, and with his right hand, that he saw nothing. Yet, with his left hand he indicates that he did see the object! Conversely, if a stimulus appears in his right visual field, he will indicate awareness of this stimulus when he responds verbally or with his right, yet with his left hand he will report that he saw nothing. This exactly fits the notion that in a split-brain patient the two separated hemispheres each become an independent conscious agent. The left hemisphere perceives the right visual field, controls language and the right side of the body. The right hemisphere experiences the left visual field and controls the left hand. This, and other discoveries on split-brain patients, earned Roger Sperry the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1981.

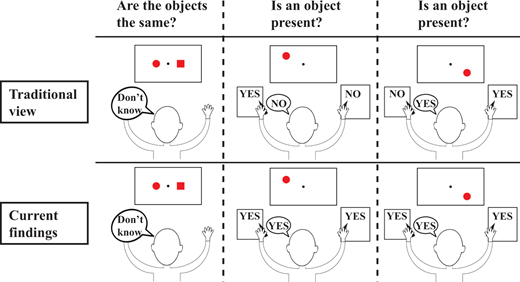

A depiction of the traditional view of the split brain syndrome (top) versus what was actually found in two split-brain patients across a wide variety of tasks (bottom). Image by Yair Pinto et al. Used with permission.

A depiction of the traditional view of the split brain syndrome (top) versus what was actually found in two split-brain patients across a wide variety of tasks (bottom). Image by Yair Pinto et al. Used with permission.Thus, case closed. The two major theories of consciousness are correct: Without cortical connectivity, different brain parts can no longer create one conscious agent. Instead each part creates its own independent conscious agent.

There is only one slight problem: there are split-brain patients who do not show this pattern of results. Pinto and colleagues re-investigated the fundamental question of conscious unity in split-brain patients. They noticed that even in the existing literature on split-brain patients, the results are much more complicated than the clear-cut picture presented in reviews and textbooks. Moreover, no research had quantified exactly how much the location of stimulus presentation (and thus the hemisphere with which the stimulus was perceived) influenced the ability of the split brain patient to respond with their left hand, right hand, or verbally. The existing literature only stated, based on qualitative observations that split-brain patients indicated awareness with the left hand only to the left visual field, and with the right hand/verbally to the right visual field. Based on these observations, it is impossible to determine whether this effect was absolute, indicating the presence of two independent conscious agents, or a large but not absolute effect, which would indicate that separating cortical connections does not result in completely independent conscious agents.

Pinto and colleagues investigated this question in two split-brain patients. To their surprise, the canonical claims were not replicated. In both patients, across many tasks, there was no response type to visual field interaction. Both patients indicated awareness of stimuli throughout the entire visual field (left and right) irrespective of response type. So even if a patient responded with the left hand, he had no problem indicating the presence of a stimulus in the right visual field, and vice versa. Yet, the patients did differ from healthy controls, in the sense that they could not compare stimuli across visual fields (although they could make this comparison within a visual field).

This finding turns the previously neat picture upside down. Not only do split-brain patients behave normally, and introspectively feel normal, careful tests actually show that conscious unity is preserved: even though there is no cortical connection between the two hemispheres, there seems to be one conscious agent, that is in control of the entire body and who can respond to stimuli everywhere in the visual field. Thus, the lesson learned from split-brain patients is opposite to the previous conclusions: it suggests that cortical connectivity is not needed for conscious unity.

Instead, the authors suggest that the best way to think of split-brain patients is in terms of conscious unity, but split perception. One agent perceives the entire visual field and controls the entire body, but the streams from the left and right visual field remain unintegrated (and hence the patient cannot compare stimuli across the visual fields). This does mean that consciousness remains a mystery. If conscious unity does not depend on cortical connectivity, what then are its essential requirements? Whatever the explanation, it seems clear that these new split-brain findings pose a serious challenge for the currently leading theories on consciousness.

Featured image credit: “Right brain” by Allan Ajifo. CC BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Conscious unity, split perception appeared first on OUPblog.

La La Land and the Hollywood film musical

Say what you will about the strong fan base of La La Land and its probable domination of the upcoming Oscars after sweeping so many of the guild awards, not to mention the critical backlash against it that I have seen in the press and among scholars on Facebook, but Damien Chazelle certainly knows the history of the Hollywood film musical. The allusions to An American in Paris, Singin’ in the Rain, Funny Face, and Sweet Charity are pretty apparent, as is the homage to the French homage to Hollywood, Young Girls of Rochefort.

I am surely not the first person to note this, but La La Land is also a formal throwback to the great Fred Astaire-Ginger Rogers musicals of the 1930s. Consider the numbers in Top Hat: “No Strings,” Astaire’s solo in which he loudly disclaims romance but then dances softly on the floor above in order to lull an angry Rogers to sleep; “Isn’t This a Lovely Day (to be Caught in the Rain)?,” a challenge dance between the two stars, which awakens her feelings for him; the title tune, a show number for Astaire to display his expertise and masculinity; “Cheek to Cheek,” a waltz that clinches the couples’ romance and metaphorically expresses sexual consummation; and “The Piccolino,” a communal song and dance celebrating the couple, which is also reprised at the end as the two stars dance away together. The numbers direct the progress of the narrative, with the boy-meets-girl plot pushed forward by the musical elements, which is also to say that the numbers are where the substance of the film resides, not the plot. The numbers are its flagship sequences.

La La Land works the same way, with its numbers structuring the romance of Seb (Ryan Gosling) and Mia (Emma Stone). La La Land opens rather than closes with the communal number, “Another Day of the Sun,” and then shifts the film’s viewpoint to Mia. She gets the equivalent of Astaire’s “No Strings” number as her roommates lure her into singing and dancing with them in “Someone in the Crowd.” After Mia meets Seb again at the pool party and they leave together, their challenge dance, “A Lovely Night,” awakens their mutual attraction even while the lyrics deny it. Their subsequent dance among the stars in “Planetarium,” the metaphoric expression of their sexual consummation, and their singing of “City of Stars” doubly perform the same function as “Cheek to Cheek” to celebrate the pair’s chemistry as a romantic couple. The final song is Mia’s show number, “The Audition,” which lands her the part in the film that makes her a movie star. The fantasy finale or “Epilogue,” which picks up the earlier “Another Day of the Sun” for one of its main musical themes, then closes La La Land somewhat like the reprise of “The Piccolino” in Top Hat.

I realize that “Epilogue” is more complex than that Top Hat reprise, that the plaintive melody of “City of Stars” belies its lyrics to focus attention on Seb’s opening and closing question, and that I have knowingly left out in my summary John Legend’s show number, “Start a Fire,” which is the sellout by Seb that eventually breaks up the couple. Nonetheless, it is clear that Chazelle more or less follows the Astaire-Rogers template for his romantic couple in order for their similarity and differences from the famous team — and what they still personify for musicals as the epitome of romanticized heterosexual coupling — to stand out more forcefully, again in musical terms.

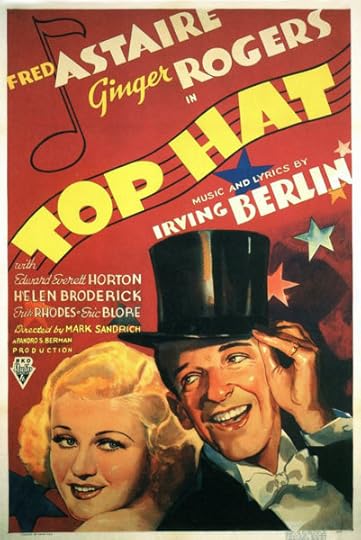

Movie poster for the 1935 musical Top Hat, starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Movie poster for the 1935 musical Top Hat, starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.I have heard both praise and criticism of Stone’s and Gosling’s singing and dancing, in contrast with the expertise of the old stars like Astaire and Rogers, or Gene Kelly and Judy Garland, who once populated the genre. I think the ordinary quality of the singing may be intentional since Stone’s and Gosling’s voices do not seem amplified at a higher aural register, as it would have been at MGM, say: despite Stone’s and Gosling’s stardom, these are ordinary people with unrealistic dreams who enter a musical where dreaming is possible. Their dreaming is then given form and expression by the numbers, which set up a counterpoint to the predictability of the narrative. The opening number–when traffic stops on the freeway, and everyone but Seb and Mia get out of their cars to sing, dance, and do their specialty bits–tells us right away that musicals express a utopian sensibility–not as an escape from but as an escape to a stylized kind of experience that is more vital and energizing, more imaginative and fulfilling, than everyday life, where one is inevitably stuck. The utopian “Epilogue,” which then revises the narrative entirely in musical terms, doing so in ways that make the genre’s history seem fully present, contrasts with the “real” world in which Mia has a great career, a husband she loves, and a child she adores, while Seb has his club, preserving what he considers to be the purity of jazz.

I don’t think what either character specifically dreams is as important as that they are dreamers. After all, in “City of Stars” Seb states his dreams have come true from his being in love, but he still asks if the city shines so brightly only for him. In the golden age of Hollywood musicals, the romance and professional plots always coincided before the end credits rolled; the couple is the show, and the show is the couple, as the end of The Band Wagon explicitly announced. With its fantasy epilogue, however, La La Land closes by effectively and permanently disaggregating the show from the couple; the epilogue recognizes the utopian pleasures of the musical while the framing of the fantasy registers the impossibility of sustaining that utopian spirit in “real” life.

Featured Image credit: Oscar statues in 2012 by Ivan Bandura, CC By 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post La La Land and the Hollywood film musical appeared first on OUPblog.

Preparing your choir to sing

In a culture where people sing all the time, every day, or in a profession or context where you sing regularly, then your voice is pretty much ‘warmed up’ all the time, and if you have sufficient body awareness, you will be loose, relaxed, and limbered up in any case. But when working with ‘civilians’ who sing in a choir just once a week, or who come to a singing workshop every few months, a vocal warm up is both important and necessary for many sensible reasons that any good choir director will be familiar with. However, if you need any more convincing, here are some less obvious reasons of why preparing to sing should always be incorporated into a choir’s rehearsal plan:

Transition from the everyday

Many choirs are run on weekday evenings and their members have usually come from a hard day’s work and a multitude of demands in their personal lives. The atmosphere we are trying to create in rehearsal is one of relaxed informality, of focus and concentration, of silliness and imagination, of creativity and beauty, of timelessness and joy. Most of these elements are missing from our everyday lives, so in a warm-up, we have to allow a period of transition for people to settle into a different world: a world of music-making and collaboration.

Relax and release tension

Having sat all day at a PC, driven for half an hour, and rushed to get to choir on time, it’s no wonder people are rather tense and a little stressed. Their shoulders are up by their ears, their pelvises are locked, their jaws are clenched, their brows furrowed. We need to coax and persuade people to relax, release, stretch, let go and be free in their bodies (and minds!).

Connect body, breath, voice

Warm-ups help us to re-connect three vital components of singing – body, breath, and voice, and remember how they are inextricably linked. Gone are the days of the clenched buttocks, feet in second position, and formally held hands of the posh recital. We need to get back to the cotton fields, the chain gangs, and the weaving looms, and sing with our bodies, breathe with our imagination, and dance with our mouths.

Engage imagination and creativity

Image by Africa Rising, via Shutterstock.

Image by Africa Rising, via Shutterstock.If we just go through the motions of familiar technical exercises it soon gets boring and we don’t put ourselves fully into the work. However, if we can engage our imaginations then we become totally engaged in the exercises and get the maximum benefit from them. So rather than asking someone to simply stretch upwards, ask them to reach for the stars; rather than asking for short, sharp breaths from the belly, ask them to pretend to be a steam train.

Hone listening skills

We have become a visual society. We are constantly bombarded with visual imagery through advertising, TV, cinema, the internet, etc. There is such a cacophony of visual noise in our everyday lives that it is important to switch this off and re-connect with the world of sound, re-engage with our ears, hone our listening skills. Warm-ups are one of the ways to do this.

Develop sense of timing and rhythm

In Western culture, this is perhaps one of the hardest challenges, especially if we are learning songs from the ‘world music’ repertoire, e.g. from Africa or the Balkans. Ours is predominantly a culture where music is melodic rather than rhythmic. Our songs, if we can dance to them at all, tend to be in strict 4/4 or 3/4 time. In our warm-up sessions we can practice off beats, all coming in at the same time, strange dances to 7/8 beats, clapping in time, stepping in time, and so on. This will all feed back into those songs that have a rhythmic basis, it will also help the choir engage their bodies with their voices.

Be conscious of working with others

Your choir members have chosen to come out to sing with others, but when singing in unison, we need to be conscious of everyone else in the choir in order to sing at the same time, to get be singing the same melody and to articulate the vowels similarly to enable vocal blending. In harmony singing this is even more important. There is a tendency when running warm-ups to simply give out a series of individual exercises, but it is also important to introduce exercises that help people work with and off others to enable them to develop a greater awareness of the rest of the choir around them.

Ultimately, time spent on developing the voice, body, and mind through fun and imaginative warm-up exercises will result in a relaxed, centred, focused, and engaged choir and a more effective and productive rehearsal.

An expanded version of this article was first published on 1 February 2009, written by Chris Rowbury.

Featured image credit: “Choir” by Enterlinedesign, via Shutterstock.

The post Preparing your choir to sing appeared first on OUPblog.

Accelerated ageing and mental health

The accelerated ageing of the populations of developed countries is being matched in the developing world. In fact, in 2017, for the first time in history, the number of persons aged 65 and over will outstrip those aged 5 and under. This population trend is not just a temporary blip, not just due to a short-term outcome of the baby boomer generation. What we are seeing is the increasing lifespan of older persons and the decreasing number of births (but also better survival rates of infants and young children) worldwide, leading to greater equality in the numbers of these two groups over time. The World Bank estimates that in 2015, approximately 8.3% of persons globally were over 65, and this will only increase in the coming decades. Currently the USA is at 15% of persons over age 65, a great percentage of Europe stands at 16+%, with Japan, the oldest nation as a whole, at 26%. By 2050, more than 20% of the population of many nations will be over 65.

While most older adults are content with their circumstances, in the face of increasing years of living, both mid-aged and older persons are concerned with having the ability to pursue their goals and have high quality of life as they age. Health plays a large role in being able to lead the life you want to, particularly after retirement.

People can act to lower the risk of many age-related illnesses, including dementia. Lifestyle modification, and in particular exercise, are important factors here. Most people know that increasing physical activity and keeping mentally active help with ageing well, but being engaged with others is also vitally important. Older adults with adequate social relationships are 50% more likely to survive than those with insufficient social support, an effect comparable with quitting smoking and of greater benefit than avoiding obesity and lack of exercise.

And the benefits of maintaining physical, mental, and social activities extend to mental well-being in later life. It’s a myth that older people are more likely to be depressed and anxious than younger people. Actually, the reverse is true, and this is a global phenomenon not simply a cohort effect. But among those who are older and experiencing poor mental health, the unfortunate fact is that they are more likely to either have their mental health inadequately assessed or treated, or to be reflexively referred for pharmacological treatment rather than psychosocial treatments. For persons with dementia or those already on multiple medications, such empirically sound non-pharmacological treatments can offer real hope. In fact, many studies suggest that older people would rather seek talking therapies for mental health issues.

In 2017, for the first time in history, the number of persons aged 65 and over will outstrip those aged 5 and under.

Key risk factors for depression in later life include: disability; newly diagnosed medical illness; poor health status; poor self-perceived health; prior depression; and bereavement. Protective factors include greater perceived social support, regular physical exercise, and higher socioeconomic status. Anxiety is actually more common later in life when compared to the incidence of depression, and many risk factors are the same for both anxiety and depression. Key risk factors for anxiety in older persons include poor self-rated general health status, and physical or sexual abuse in childhood. Protective factors include greater perceived social support, regular physical exercise, and higher level of education. Persons who are migrants, particularly those over 65, are at greater risk of mental health issues than non-migrants, and are a particular group of concern in a more globally-connected world.

One common experience across cultures is that of feeling younger than one’s chronological age, which has been demonstrated in several studies internationally. Also, the older one is, the greater the gap between one’s actual age and how old one feels. Typically, after 65, people generally feel about ten years younger than their chronological age.

Despite varying contexts and circumstances, largely individual factors—particularly physical and mental well-being, both objective and subjective—contribute to one’s subjectively imagined age. A longitudinal study found that the higher the person’s subjective age the higher their chance of experiencing poor health and higher mortality, even after adjusting for multiple potential contributing factors. In other words, the closer our perceived and actual ages are, the worse off we are likely to be.

As older adults themselves take increasing interest in pursuing strategies for optimizing physical, cognitive, and emotional health, research in a range of fields will be needed to provide a solid empirical base to guide both consumers as well as health care providers, governments, and policy makers. If the potential of those entering later life is to be realised, understanding the process of aging is important for individuals, but also for societies and nations.

Featured image credit: Hand Age Time by Celiosilveira. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Accelerated ageing and mental health appeared first on OUPblog.

February 23, 2017

Where your mind goes, you go? (Part 1)

What does it take for you to persist across time? What sorts of changes could you survive, and what sorts of changes would bring your existence to an end? The dominant approach to personal identity says that a person persists over time by virtue of facts about psychological continuity (e.g. continuity of memory, character, or mental capacities). Various puzzle cases have been presented to support this view. In John Locke’s famous story, for example, we are asked to imagine that the consciousness of a prince and the consciousness of a cobbler switch bodies. Locke found it intuitively obvious that the cobbler would be the person with the cobbling consciousness and the princely body (rather than the person with the princely consciousness and the cobbling body).

In contemporary versions of the “transplant case,” you are asked to suppose that a surgeon removes your cerebrum, implants it into another head, and connects its nerves and blood vessels with the corresponding nerves and tissues of the skull of another human being. Your cerebrum grows together with the inside of that skull and comes to be connected to the rest of that human being in just the way that it was once connected to you. What is more, it is assumed that because the cerebrum is responsible for reasoning and memory capacity, this being can remember your past and act on your intentions. Although this being will be very different from you, physically speaking, most people share the intuition that you are the being who inherits your psychological profile.

…we can say that you survive as two different people without implying that you are (are identical to) these people.

Because this psychological approach to personal identity characterizes persons as moral agents that persist through time, it fits well with some of our important practical and moral concerns. In acting and making plans for the future, we assume that we will exist at a later time; and socially, we relate to others as persons with ongoing histories who can act intentionally and be held accountable for their past actions.

However, this account faces a so-called “duplication problem”: suppose that we surgically divide your brain, and then transplant each of your cerebral hemispheres into a different head and body, producing two people with your mental capacities, apparent memories, and character. It seems reasonable to suppose that you would survive if your brain were successfully transplanted into one body. But now, if both halves (which are exactly similar) are transplanted, will you survive as two people? If “survive” implies identity, then this makes no sense: you (a single entity) cannot be identical to two people. However, it is implausible to suppose that you don’t survive, and arbitrary to insist that you survive as one person but not the other. The fact that a single person could be psychologically continuous with two or more persons seems to pose serious difficulties for the psychological approach.

The way out of this puzzle, Derek Parfit famously maintains, is to give up the language of identity: we can say that you survive as two different people without implying that you are (are identical to) these people. Important questions about memories, character, intentions, and responsibility should be prized apart from the question about identity; and this is because while identity is a one-to-one relation, what matters in survival need not be one-to-one. What we care about in survival, according to Parfit, is psychological continuity and connectedness, which is a form of continued existence that does not imply identity through time. Your relationship to the two new people contains everything that matters, namely a continuity of memories, character, and dispositions, and thus you survive as both of them.

Derek Parfit by Anna Riedl. CC0 Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Derek Parfit by Anna Riedl. CC0 Public Domain via Wikimedia CommonsBut is it true that psychological continuity is all that interests us when it comes to questions surrounding survival? Imagine that Kate gets into a car accident and sustains a head injury. As a result, she suffers from amnesia: although her memory of many basic facts remains intact, her autobiographical memory is erased. In addition, her personality is radically altered, and she no longer has the same intentions and goals for the future as she once did. Although she retains very basic skills, such as the ability to tie her shoes, she loses much of her prior knowledge about topics that once were of great interest her (e.g. cooking, baseball statistics, and art history). There is a sense, then, in which Kate no longer exists. Instead, an individual who calls herself Katherine, and whose psychological profile differs dramatically from Kate’s, has come into existence.

And yet even though Kate does not survive in a psychological sense, there are important questions here that do center on the question of identity. For example, there are questions about whether Kate’s family has obligations to Katherine, whether Katherine is obligated to pay off certain debts that Kate has incurred, and whether Katherine has duties to care for the child that Kate chose to adopt five years ago. Even though psychological continuity is lacking, I suspect that many of us will answer these questions in the affirmative; and this likely is because we still have a sense that Katherine and Kate are one and the same individual.

In cases where a loved one suffers from amnesia or dementia, or undergoes a radical shift in personality, we still tend to think it is them in some deep sense, due to the persistence of their living body. This suggests that what matters to us in survival is both psychological and biological.

Featured image credit: Time by Niklas Rhoser. CC0 Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post Where your mind goes, you go? (Part 1) appeared first on OUPblog.

What chocolate chip cookies can teach us about code [excerpt]

What is “code”? Although “code” can be applied to a variety of areas—including, but not limited to computer code, genetic code, and ethical code—each distinct type of code has an important similarity. Essentially, all code contains instructions that lead to an intended end. Philip E. Auerswald, author of The Code Economy, argues that code drives human history. Humanity’s constant effort to create and improve allows concepts to actualize and processes to develop.

In the shortened excerpt below, Auerswald discusses “code in action,” explaining not only the what, but the how behind modern innovation.

You are baking chocolate chip cookies. You have arrayed before you the required ingredients: 1 cup of butter, 1 cup of white sugar, 1 cup of brown sugar, 2 eggs, 1 teaspoon of baking soda, 2 teaspoons of hot water, 1/2 teaspoon of salt, and (importantly) 2 cups of chocolate chips. These items, 30 minutes of your own labor, and access to the oven, bowls, and other durable equipment you employ constitute the inputs into your production process. The work will yield 24 servings of two cookies each, which constitute your output.

The essential idea is that the “what” of output cannot exist without the “how” by which it’s produced. In other words, production is not possible without process.”

From the perspective of standard microeconomic theory, we have fully described the production of chocolate chip cookies: capital, labor, and raw material inputs combine to yield an output. However, as is obvious to even the least experienced baker, simply listing ingredients and stating the output does not constitute a complete recipe. Something important is missing: the directions—how you make the cookies.

The “how” goes by many names: recipes, processes, routines, algorithms, and programs, among others.

The essential idea is that the “what” of output cannot exist without the “how” by which it’s produced. In other words, production is not possible without process. These processes evolve according to both their own logic and the path of human decision-making. This has always been true: the economy has always been at least as much about the evolution of code as about the choice of inputs and the consumption of output. Code economics is as old as the first recipe and the earliest systematically produced tool, and it is as integral to the unfolding of human history as every king, queen, general, prime minister, and president combined.

We cannot understand the dynamics of the economy—its past or its future—without understanding code.

The word “code” derives from the Latin codex, meaning “a system of laws.” Today code is used in various distinct contexts—computer code, genetic code, cryptologic code (i.e., ciphers such as Morse code), ethical code, building code, and so forth—each of which has a common feature: it contains instructions that require a process in order to reach its intended end. Computer code requires the action of a compiler, energy, and (usually) inputs in order to become a useful program. Genetic code requires expression through the selective action of enzymes to produce proteins or RNA, ultimately producing a unique phenotype. Cryptologic code requires decryption in order to be converted into a usable message.

To convey the intuitive meaning of the concept I intend to communicate with the word “code,” as well as its breadth, I use two specific and carefully selected words interchangeably with code: recipe and technology.

My motivation for using “recipe” is evident from the chocolate chip cookie example I gave above. However, I do not intend the culinary recipe to be only a metaphor for the how of production; the recipe is, rather, the most literal and direct example of code as I use the word. There has been code in production since the first time a human being prepared food. Indeed, if we restrict “production” to mean the preparation of food for consumption, we can start by imagining every single meal consumed by the roughly 100 billion people who have lived since we human beings cooked our first meal about 400,000 years ago: approximately four quadrillion prepared meals have been consumed throughout human history.

Each of those meals was in fact (not in theory) associated with some method by which the meal was produced—which is to say, the code for producing that meal. For most of the first 400,000 years that humans prepared meals we were not a numerous species and the code we used to prepare meals was relatively rudimentary. Therefore, the early volumes of an imaginary “Global Compendium of All Recipes” dedicated to prehistory would be quite slim. However, in the past two millennia, and particularly in the past two hundred years, both the size of the human population and the complexity of our culinary preparations have taken off. As a result, the size of the volumes in our “Global Compendium” would have grown exponentially.

“We cannot understand the dynamics of the economy—its past or its future—without understanding code.”

Let’s now go beyond the preparation of meals to consider the code involved in every good or service we humans have ever produced, for our own use or for exchange, from the earliest obsidian spear point to the most recent smartphone. When I talk about the evolution of code, I am referring to the contents of the global compendium containing all of those production recipes. They are numerous.

This brings me to the second word I use interchangeably with code: technology. If we have technological gizmos in mind, then the leap from recipes to technology seems big. However, the leap seems smaller if we consider the Greek origin of the word “technology.” The first half derives from techné (τέχνη), which signifies “art, craft, or trade.” The second half derives from the word logos (λόγος), which signifies an “ordered account” or “reasoned discourse.” Thus technology literally means “an ordered account of art, craft, or trade”—in other words, broadly speaking, a recipe.

Substantial anthropological research suggests that culinary recipes were the earliest and among the most transformative technologies employed by humans. We have understood for some time that cooking accelerated human evolution by substantially increasing the nutrients absorbed in the stomach and small intestine. However, recent research suggests that human ancestors were using recipes to prepare food to dramatic effect as early as two million years ago—even before we learned to control fire and began cooking, which occurred about 400,000 years ago.

Simply slicing meats and pounding tubers (such as yams), as was done by our earliest ancestors, turns out to yield digestive advantages that are comparable to those realized by cooking. Cooked or raw, increased nutrient intake enabled us to evolve smaller teeth and chewing muscles and even a smaller gut than our ancestors or primate cousins. These evolutionary adaptations in turn supported the development of humans’ larger, energy-hungry brain.

The first recipes—code at work—literally made humans what we are today.

Featured image credit: “Macro Photography of Pile of 3 Cookie” by Lisa Fotios. Public Domain via Pexels.

The post What chocolate chip cookies can teach us about code [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

Research interview approaches in International Relations

‘You do realise that they’ll talk differently to you because you’re British?’ I thought about this advice a lot. It came from a Zimbabwean who I met as I began research for my book about Zimbabwe’s International Relations. I planned to interview Zimbabweans to find out how they saw the world, and how they understood themselves in relation to it. The problem was that quite a large part of the story of Zimbabwe, and the world, would be about its relationship with Britain, the former colonial power and Robert Mugabe’s favourite bogeyman.

I began to think about what might happen if I saw the interviews themselves – between a Zimbabwean and a Brit – as part of the empirical material. Could I examine the dynamics of the meeting, the ways in which my interlocutors treated me and my own reactions and responses, as another way to understand the broader relationship?

There are many ways to conduct research interviews. A classic approach is to try as far as possible to be neutral, so as not to affect the outcomes and to make it possible for another researcher to replicate your findings. I have never believed in this approach – I don’t think it’s possible to remove yourself from the research process and it’s better to be thoughtful about biases than pretend that you can get rid of them. In this case, as has already been pointed out, the interview dynamics would be shaped profoundly from the very beginning by the fact of my Britishness. Another approach might be to try to establish empathy with the people I was interviewing – to try to get as much as possible inside their perspective. But this made me uncomfortable too: the search for apparently ‘common ground’ is often built on superficial perceptions on both sides, and can limit understandings of profound difference. If you jump too quickly to a position of ‘understanding’, you lose the insights you can get from sticky or problematic misunderstanding – on both sides of the encounter.

In my own field of International Relations this can be a particularly bit problem. Researchers are often reluctant to engage with the real world, to put themselves in it, preferring to remain overly theoretical, or where they do conduct empirical work, to concentrate on elites and state-level analysis. In trying to understand IR in a bottom-up way – and from an African perspective to boot – I was entering into what might look like particularly murky waters.

In the end, I decided that there was value in jumping into the murky waters. My implication in the story of Anglo-Zimbabwean relations and my relationships with the people I was interviewing would become part of the research. In particular, I would need to allow myself to explore my own feelings of empathy and warmth, fear and rejection, confusion and dislike during interviews, and to think about how their dynamics reflected on the broader questions I was asking about Zimbabwe’s international relationships.

I conducted nearly 200 interviews, with people from many different walks of life, up and down Zimbabwe. Many of these meetings were warm and friendly. One example was with ‘Rose’, a 64-year-old woman from a poor area of Harare. Rose described a miserable life under a terrible government. She thought life under British rule had been better. She wanted me to encourage the extension of British sanctions against Mugabe and the ruling party, and she described me as a ‘gift from God.’ Others were uncomfortable or downright hostile. In one encounter with a group of elderly men in Bulawayo I was challenged over sanctions and asked why I wanted to hurt Zimbabweans, to ‘kill the child coming from the womb.’ And in a meeting with two young men I found myself being attacked for being out of touch, selfish, and patronising.

Beyond the content of what was actually said – which revealed things about attitudes towards sanctions, the importance of the historical relationship, expectations of British attitudes towards the Zimbabwean government – I also learned from the emotional aspects of the interviews. Rose’s trust and assumption that as a white British woman I would ‘understand’, and my own sense of ease at slotting into this role, revealed a lot about the mutual idealisation that is a significant aspect of the Anglo-Zimbabwean relationship. This was badly shaken by more aggressive encounters in which the British role in Zimbabwe was made clear. Here I was forced to own the painful brutality and racism of colonialism and the patronising elements of the post-colonial relationship. I confronted people’s feelings of anger, alienation, and my own feelings of fear, guilt, or distaste.

The whole process was at times deeply uncomfortable, even disturbing. Rather than imagining that I could maintain the objectivity and distance of a researcher, or put myself on the side of Zimbabweans, I was plunged deeply into the mess, forced to examine my own preconceptions, and to absorb the ways in which the people I met projected theirs into me. But, emerging from this kind of messiness were layers of insight into what makes the Anglo-Zimbabwe relationship tick. I understand more about Zimbabwe, more about Britain, and more about myself, as a result.

Featured image credit: book research by João Silas. Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post Research interview approaches in International Relations appeared first on OUPblog.

Wilson Pickett and the “Ballad of Stackalee”

On the night of 27 December 1895, at the Bill Curtis Saloon in St. Louis, Missouri, two black men, “Stag” Lee Sheldon and Billy Lyons, got into an argument. They were, supposedly, friends and drinking partners, but politics was about to come fatally between them: Sheldon, reputedly a pimp on the side, was an organizer for the Democrats, seeking to win over the black vote that had traditionally gone to the Republicans, for whom Billy Lyons recruited. At some point during an increasingly drunken debate, Lyons seized Sheldon’s Stetson hat; when he refused to return it, Sheldon took out his revolver, shot Lyons in the stomach, picked up his hat and calmly walked out; Lyons later died from his injuries.

As one of five murders reported in St. Louis that day, Lyons’ death might not have made much more than the local headlines—but for the fact that ragtime had recently arrived on the musical scene as a new means by which to tell a sordid musical story, and that events unfolded to make the “Stag-O-Lee” case a source of constant attention. Sheldon was arrested, indicted, bailed (to everyone’s surprise), defended in court by a white lawyer in front of a jury that then failed to reach a verdict, subsequently retried just a few weeks after that lawyer died from a drinking binge, found guilty, imprisoned, pardoned by the Governor a decade later, arrested for another shooting murder less than two years after that, and finally, died in prison hospital of tuberculosis, in 1912. By then, the rag-time song about the case had turned into “the Ballad of Stackalee”—in which the anti-hero, after being hung for the murder, kicks the Devil off his throne and takes over Hell.

In other words (and there were to be many more of them), “Stagger Lee” had become part of folklore, ripe for constant reinvention, retelling and revamping. The advent of recording did nothing to slow down that process, even when, in 1928, Mississippi John Hurt released a version widely considered as “definitive.” After literally dozens more interpretations, a euphoric 1950 “Stack A Lee” by New Orleans pianist Archibald held court for a while; in Korea, his fellow Louisiana native Lloyd Price adapted it for a play he put on while in the military, added an introduction, and upon return to America and his career, recorded it for release.

“Come 1967, and there were plenty people out there saw Wilson Pickett as ‘Stagger Lee’ incarnate.” Image courtesy of the Wilson Pickett, Jr. Legacy LLC.

“Come 1967, and there were plenty people out there saw Wilson Pickett as ‘Stagger Lee’ incarnate.” Image courtesy of the Wilson Pickett, Jr. Legacy LLC.By this point, little remained of the original incident: rather than debating politics, the two men were playing dice outdoors after dark, Billy falsely calling seven on a roll of eight and taking Stagger Lee’s money, the latter going home to get his .44, finding Billy in a bar-room, and then shooting “that poor boy so bad” that the bullet went through Billy and broke “the bartender’s glass.” Placed on the back of a single more conventionally entitled “You Need Love,” Price’s “Stagger Lee” was so rhythmically addictive that disc jockeys couldn’t help but flip it, and although Dick Clark cited the song as too violent for American Bandstand, that didn’t stop it from spending the whole of February 1959 at number one. As typical with folk songs that date back beyond copyright protection, Price and his partner Harold Logan were able to claim the songwriting credits.

Come 1967, and there were plenty people out there saw Wilson Pickett as “Stagger Lee” incarnate. Pickett was a compulsive dice player in a black music community that was full of them. Backstage at the Apollo, up in the headlining artist’s dressing room, it wasn’t uncommon for the star and his entourage – which would suddenly consist of any number of renowned dice hustlers drawn by the very prospect – to engage in a $20,000 freeze-out. If you bet that sum of money and lost it, you were done; no going back to the bank. Then again, depending how many were in the game, you could be in to win $100,000 on one roll of the dice. One particular night backstage with Curtis Mayfield and Clyde “C.B.” Atkins, Sarah Vaughn’s ex-husband whose gambling habits left her heavily in debt, became seared strongly in the memories of those who could only stand back and watch, and those freeze-out stakes would only increase over the years as Pickett got richer.

“He was a very lucky guy with dice,” said bass player Earnest Smith of his employer. “I used to see him backstage at the Apollo, I’d see all the hustlers come by and he would break them. Dice is a game of chance but you can’t get scared. Scared money don’t win.”

Wilson Pickett pictured in front of the Howard Theater. Image courtesy of the Wilson Pickett, Jr. Legacy LLC.

Wilson Pickett pictured in front of the Howard Theater. Image courtesy of the Wilson Pickett, Jr. Legacy LLC.Pickett was seen throwing at least one person who accused him of cheating at dice straight out the dressing room door, and it’s worth noting that, without even referencing “Stagger Lee,” his former band-leader Eddie Jacobs offered the following justification for why Pickett and crew (including himself) packed heat on the road:

“Guys shooting dice… a lot of them carry a gun. And sometimes you get guys who are sore losers and want to retaliate and you wanted a fair chance.”

Add in the fact that there was always something of the Mack Daddy about Pickett, a man of whom pimping rumors abounded and of whom criminal charges often failed to stick, and it was hardly surprising that he would be encouraged to claim “Stagger Lee” for himself at some point. He recorded the song during that first session at American, where the well-mannered “Memphis Boys” (as they would come to be known) put down a fiery backing track. Gene Chrisman never sounded more energized in Pickett’s company than with his rapid-fire snare drum intro; Tommy Cogbill employed a machine-gun bass line throughout, and the brass section offered enough musical ricochets as to render the listener exceedingly nervous. Pickett’s lyrics were not a complete copy of the Lloyd Price version: he swapped out Stagger-Lee’s “Stetson hat” for a Cadillac, and rapped at the start of an extensive coda about how Billy’s example ought to “teach the rest of you gamblers a lesson,” a personal warning perhaps to those who’d be looking to roll their crooked dice on him somewhere on the road.

In an additional move almost designed to repeat history, Pickett’s version was released on the flip of the “I’m In Love” single. While both tracks performed well at R&B, pop DJs uniformly made “Stagger Lee” their preference, and it became another substantial hit for “the Wicked” at the end of 1967. The singer had, in fact, dodged a bullet of his own when James Brown’s rendition was released first, but only on the Cold Sweat LP and not as a single; the two versions, heard side by side, serve to confirm the substantial differences in rhythmic approach and audio standards between two of the era’s leading soul men.

Featured image credit: Courtesy of the Wilson Pickett, Jr. Legacy LLC.

The post Wilson Pickett and the “Ballad of Stackalee” appeared first on OUPblog.

The civil rights movement, religion, and resistance

In the following excerpt from the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion, Paul Harvey explores how the Civil Rights Movement might not have been successful without the spiritual empowerment that arose from the culture developed over two centuries of black American Christianity. In other words, religious impulses derived from black religious traditions made the movement actually move.

In the civil rights movement of the mid-20th century, black Christian thought helped to undermine the white supremacist racial system that had governed America for centuries. The civil rights revolution in American history was, to a considerable degree, a religious revolution, one whose social and spiritual impact inspired numerous other movements around the world. Key to the work was a transformation of American religious thought and practice in ways that deftly combined the social gospel and black church traditions, infused with Gandhian notions of active resistance and “soul force,” as well as secular ideas of hardheaded political organizing and the kinds of legal maneuverings that led to the seminal court case of Brown v. Board of Education.

The civil rights movement had legislative aims; it was, to that extent, a political movement. But it was also a religious movement, sustained by the religious power unlocked within southern black churches. The historically racist grounding of whiteness as dominant and blackness as inferior was radically overturned in part through a reimagination of the same Christian thought that was part of creating it in the first place. As one female sharecropper and civil rights activist in Mississippi explained in regard to her conversion to the movement, “Something hit me like a new religion.” In similar ways, the Mexican-American farmworkers’ movement drew on the mystic Catholic spirituality of Cesar Chavez and brought to national consciousness the lives and aspirations of an oppressed agricultural proletariat that lacked the most elementary rights of American citizens.

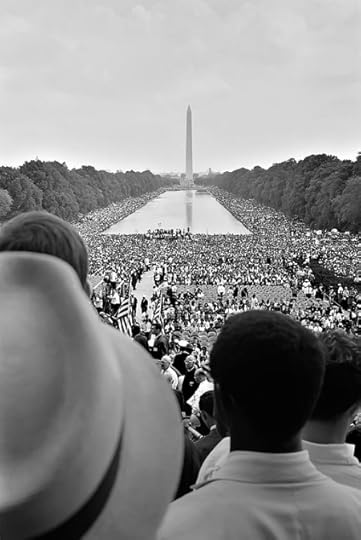

“Civil rights march on Wash[ington], D.C.” by Warren K. Leffler. Public Domain via Library of Congress.

“Civil rights march on Wash[ington], D.C.” by Warren K. Leffler. Public Domain via Library of Congress.In the mid-20th century, visionary social activists set out to instill in a mass movement a faith in nonviolence as the most powerful form of active resistance to injustice. The ideas of nonviolent civil disobedience first had to make their way from the confines of radical and pacifist thought into African American religious culture. This was the work of the generation before the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s. A legacy of radical ideas stirred women and men from Pauli Murray and Ella Baker to Walter White, Charles Johnson, and Bayard Rustin. Black humanists, atheists, freethinkers, and skeptics transmitted ideas of nonviolent civil disobedience to a skeptical audience of gun-toting churchgoers and blasted the ways in which conventional southern Protestantism stultified social movements for change.

Because of the prominence of Martin Luther King Jr. and other ministers, many have interpreted the freedom struggle as a religious movement at its core. More recently, scholars have highlighted the politically radical and secular roots of the struggle in the political black left (especially the Communist Party) of the Depression. Moreover, the argument goes, the movement’s Christian morality and dependence on dramatizing the immorality of segregation through acts of nonviolent civil disobedience fell short when forced to confront deeper and more structurally built-in inequalities in American society. To those stuck in poverty, the right to eat a hamburger at a lunch counter was not particularly meaningful. Further, as the 1960s progressed more rhetorically radical leaders emerged. Often, they distrusted black Christian institutions, seeing them as too complicit with larger power structures.

Nonetheless, it remains impossible to conceive of the civil rights movement without placing black Christianity at its center, for that is what empowered the rank and file who made the movement move. And when it moved, major legal and legislative changes occurred. King’s deep vision of justice, moreover, increasingly moved toward addressing issues of structural racial inequality. As the 1960s progressed, his moral critique of economic stratification, white colonialism, and the Vietnam War drew harsh criticism from many whites. It also made him the target of a relentless surveillance apparatus at federal, state, and local levels.

Activists in the 1960s held a more chastened view about religion’s role. For example, the institutional conservatism of Martin Luther King Jr.’s own denomination, the National Baptist Convention, forced King and a splinter group of followers to form the Progressive National Baptist Convention, a denomination more avowedly tied to civil rights. At local levels, indifference, theological conservatism, economic coercion, and sometimes threats of violence repressed the majority of black churches. Student volunteers from across the country, often coming with their own forms of religious skepticism, witnessed how often churches hindered rather than motivated a southern revolution. Further, activists often encountered the view that humans could do little to move the forces of history.

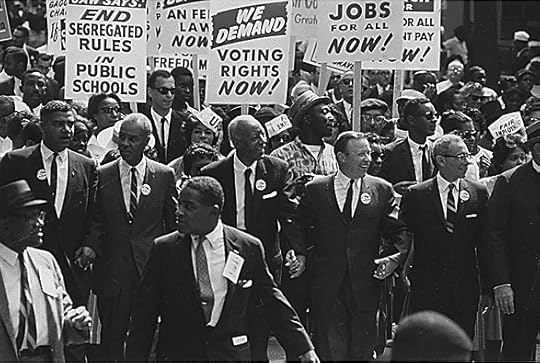

“Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C.” by Rowland Scherman for USIA. Public Domain via National Archives Catalogue.

“Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C.” by Rowland Scherman for USIA. Public Domain via National Archives Catalogue.There was nothing inherent in “religion” in the South that either justified or blocked social justice struggles. The southern freedom struggle redefined how the central images and metaphors of black southern religious history could be deployed most effectively to mobilize a mass democratic movement. It also vividly illustrated the emotionally compelling power latent in the oral and musical artistry developed over centuries of religious expression, from spirituals and the gospel to sermonic and communal storytelling traditions.

To transform the region so dramatically, southern activists wove a version of their own history of social justice struggles out of a complicated tangle of threads. To do so, they engaged in narrative acts that allowed people to see themselves as part of a long-running tradition of protest. They revivified part of the history of black southern Christianity. They did not have to invent a tradition, but they needed to make it a coherent narrative.

Nothing else could have kept the mass movement going through years of state-sponsored coercion, constant harassment, and acts of terrorism. The historically racist grounding of whiteness as dominant and blackness as inferior was radically overturned in part through a reimagination of the same Christian thought that was part of creating it in the first place. Many perceived it as a miraculous moment in time and sanctified its heroes. But that moment arose slowly and only after decades of preparation and struggle.

Featured image credit: Martin Luther King Jr. addresses a crowd from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial where he delivered his famous, “I Have a Dream,” speech during the Aug. 28, 1963, march on Washington, D.C. via the US Marines. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The civil rights movement, religion, and resistance appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers