Oxford University Press's Blog, page 400

February 27, 2017

From hostage to fortune to prisoner of war

On 10 August 1678, France and the Republic of the United Provinces of the Northern Netherlands signed a peace treaty at Nijmegen [Nimeguen]. The treaty, which was one of several between the members of opposing coalitions, ended the war which had started with the nearly successful surprise attack by the French King Louis XIV (1638–1715) on the Dutch Republic in 1672.

In its Article 11, the treaty stipulated:

“All prisoners of war will be freed by one side and the other, without any distinction or reserve, and without paying any ransom.”

This clause was exceptional for its time because of its brevity and the broadness of its sweep as it set no conditions or restrictions to the general release of prisoners of war by the former belligerents. It was a precedent to what would become general practice during the 18th century. Peace treaties of the 16th and 17th centuries mostly set one or two restrictions. One restriction, which largely disappeared during the early 17th century, was that an exception was made for those captives of war who had already reached agreement with their captors over the payment of ransom. The other, which remained current throughout much of the 17th century, stipulated that the prisoners of war were liable for the payment of their living costs during captivity. Article 21 of the Peace Treaty of Vervins between France and Spain of 2 May 1598 contained both exceptions. The Franco-Spanish Peace Treaty of Rijswijk [Ryswick] of 20 September 1697, in its article 14, only retained the second condition, exempting, however, those captives who had been put to work on galleys from repaying their living expenses.

The release of prisoners of war through peace treaties at the end of war became standard practice in European peace-making between the 16th and early 18th centuries, with some earlier examples from Italy. It constituted a break from late-medieval practices and the laws and customs which regulated late-medieval warfare. Under these laws, the individual warrior who captured an enemy warrior acquired a personal right over his captive allowing him to hold him for ransom. Much like in the case of loot, title to this ransom pertained in principle to the individual captor and not to the king, prince, or commander under whom he served. The regulation of captivity and ransom was one of the most crucial and sophisticated aspects of the so-called code of chivalry, the collective name which is given to the customary rules which regulated warfare among knights and found scholarly exposition in some legal treatises, such as those of Giovanni da Legnano (died 1383) and Honoré Bonet (c. 1340–c. 1410).

‘King Louis XIV of France’ by

‘King Louis XIV of France’ byJustus van Egmont. CC via Wikimedia Commons.

The status, release, and ransom of captives of war were thus largely subject to private contracting. Nevertheless, there were also numerous instances of interferences by kings, princes, and military commanders. These could take various forms and were based on different motivations. One common practice was for military commanders to forbid plundering or taking prisoners for ransom as long as the battle was not decided. Such rulings were obviously dictated by military expediency. From studies from the Hundred Years War (1337–1453) between France and England, there are numerous examples of royal interference with private settlement. Kings often claimed and exercised a right to appropriate the control over certain captives and take them from their individual captors, although they did generally provide financial compensation. The major reasons for doing so were to secure the captivity of an important enemy, to facilitate exchange for important captives from one’s own side, or, more generally, to assert royal authority.

Exchange of captives during and after the war became more generalised and standardised in Italy over the 15th century. The rise of mercenary armies and military entrepreneurship led to an enhanced disciplinary control of military commanders, condottieri, and their employers over their troops. With this came also an enhanced responsibility on the part of these captains for the fate of their soldiers. The gradual growth of public control over armed forces during the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries further strengthened top-down disciplining and financial control by governments and their commanders over officers, soldiers, and sailors. This did not extinguish all rights of individual officers and soldiers to partake in the profits of plunder but it gradually led to the demise of private control over captives of war. Rather than a source of private income, capturing enemy personnel came to be seen as a way to ensure the military weakening of the enemy while governments at the same time took greater responsibility for ensuring the release of their own soldiers.

To attain this, two types of international legal instruments were deployed. One was a capitulation or cartel between military commanders or governments during the war whereby the conditions for the mutual exchange or release of captives were set between warring parties or their armies. Such capitulations or cartels became a standard feature of European warfare over the 16th and 17th centuries. In principle, these cartels, like the one made between France and the Dutch Republic at Maastricht on 21 May 1675, provided that prisoners would be exchanged for prisoners of the same worth, or be ransomed. To avoid discussions about the balance of exchange, tariffs of ransoms were set per rank and office.

The second relevant type of instrument was a peace treaty. As the 16th century drew to a close and the 17th century commenced, an increasing number of peace treaties included a clause stipulating the release of all prisoners of war. With their agreement to such clauses, governments usurped the rights of their own soldiers to exact ransom. In this case, no compensation was offered to the captors for the loss of their right.

Over the course of the 17th century, the exception for captives who had already agreed on their ransom with their ‘master’ disappeared from peace treaty practice. Just like amnesty clauses, whereby princes signed away the claims of their subjects to compensation for wartime damage, this shift fell within the emerging logic that war and peace were an affair of state, to which private interests were subject.

Featured image credit: ‘Peace of Nijmegen’, by Henri Gascar. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post From hostage to fortune to prisoner of war appeared first on OUPblog.

February 26, 2017

Telling (fairy) tales

Fairy tales have been passed down through communities for many hundreds, if not thousands, of years, and have existed in almost all cultures in one form or another. These narratives, often set in the distant past, allow us to escape to a world very unlike our own. They usually follow a hero or heroine who comes up against some sort of obstacle (or obstacles) – from witches and ogres, to dwarves and (as the name suggests) fairies.

In the beginning, before writing and printing, these stories were passed down by storytellers across the ages using the oral tradition. Written versions started to appear before the modern systematic collection of tales we know today, meaning that the oral and literary have intermingled for generations. However, the genre of fairy tales still holds characteristics and legacies that come from oral transmission.

We’ve dug out some interesting facts about fairy tales and their oral tradition – how many of these will you pass along?

There are three main, specifically oral, prose genres of folklore. Fairy tales are one, and the others are myth and legend. Myths are believed to be true stories about gods or magical beings that can teach a moral lesson, whereas legends report extraordinary things happening to ordinary people (generally reported as true, but with some reservations on behalf of the audience and/or narrator).

Paradoxically, until the middle of the 20th century people that researched the oral tradition of fairy tales actually studied them in text-form.

Because of their oral tradition, fairy tales have crossed borders freely, with some of the same stories appearing across many different cultures. For example, the earliest recorded version of Cinderella was found in a mid-9th century Chinese book of folk tales.

Image Credit: ‘Mother Goose reading written fairy tales’ by Gustave Doré. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image Credit: ‘Mother Goose reading written fairy tales’ by Gustave Doré. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The roots of German literary fairy tales go as far back as ancient Egypt and the Graeco-Roman period, as well as the pagan Nordic and Slavic traditions.

One of the earliest references to a British fairy story is in the work of Giraldus Cambrensis in 1188, when he describes being told a story as he travelled through Wales. In this story fairies invite a boy to go with them to their country. He travels between the two worlds freely, until his mother asks him to steal some fairy gold, which he does. The fairies chase him and he falls, loses his gold, and can never find his way back to the fairy world again.

The romantic idea that the Brothers Grimm travelled across the German countryside collecting fairy tales directly from the mouths of the people that spoke them is, unfortunately, not exactly true. Instead, people who were familiar with printed fairy-tale editions went to the Grimms’ home and recited their stories, whilst others were sent in the post.

It is likely that the story of Little Red Riding Hood came from the oral tradition of sewing societies in southern France and northern Italy.

The Grimm’s (sentimental) ending to the story of Rapunzel (where the Prince’s blinded eyes are magically restored after Rapunzel’s tears land on them) cannot be found in the oral tradition of this tale.

The tales in The Arabian Nights can be traced back to three ancient oral cultures: Indian, Persian, and Arab. Scholars think that they probably circulated by word of mouth for hundreds of years before they were ever written down (which was at some point between the 9th and 15th centuries).

Featured image credit: ‘Bled, Slovenia’ by Ales Krivec. CC0 1.0 via Unsplash.

The post Telling (fairy) tales appeared first on OUPblog.

Dermatology on the wards

What should you know about skin diseases when you start your medical career as a Foundation Doctor or are trying to keep abreast of the work as a Core Medical Trainee? Does skin matter? Are you likely to need any dermatological knowledge?

Skin does indeed matter and you are sure to come across dermatological challenges perhaps as a result of treatment such as adverse drug reactions or opportunistic skin infections in immunosuppressed patients; or as a result of care during admission, for example asteatotic eczema caused by over-zealous washing or ulcers caused by trauma. You may have to address issues such as deteriorating psoriasis or you may notice an unusual pigmented lesion – is it a malignant melanoma, a pigmented basal cell carcinoma, or just an irritated seborrhoeic wart? You are in the prime position to detect a potentially life-threatening skin cancer such as malignant melanoma when you are clerking a patient. What about that chronic “leg ulcer” under the dressing? Take a look— could this be an ulcerated skin cancer, a deep fungal infection, or pyoderma gangrenosum? Skin problems such as vasculitis may indicate an underlying systemic disease. Do you need to ask for the help of a dermatologist?

Superficial spreading malignant melanoma with asymmetry in colour and outline. This melanoma did arise in a melanocytic naevus. Image provided by the author and used with permission.

Superficial spreading malignant melanoma with asymmetry in colour and outline. This melanoma did arise in a melanocytic naevus. Image provided by the author and used with permission.Remember to ask about problems such as itching or mucosal ulcers. Do not forget topical treatments when you explore the drug history. When you perform a physical examination, do not look through the skin but at it and examine all the skin, including mucous membranes, hair, and nails. Remember to take a skin scrape from asymmetrical scaly rashes if you wish to exclude fungal infections. Above all, record your findings accurately.

Cutaneous adverse drug reactions are common: 2-3% of hospitalized patients experience these reactions. Most are morbilliform and settle quickly when the drug is stopped. When should you worry? A banal looking rash may progress to a life-threatening problem such as toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) or drug rash, eosinophilia, systemic symptoms (DRESS). Red flags that indicate the patient may have a serious problem include skin tenderness, pain or a burning sensation, systemic symptoms (fever, arthralgia), mucosal ulcers, purpura, erosions or blisters, lymphadenopathy, eosinophilia, lymphocytosis, or abnormal liver function. Call for help sooner rather than later.

It will be very satisfying when you have the confidence to manage skin problems such as asteatotic eczema: remarkably common in older people admitted to hospital. An emollient that can be used as a soap substitute should be prescribed in sufficient quantity—think tubs (500g) not tubes—and avoid aqueous cream which damages the skin barrier. Ensure your topical treatment is actually being applied and is not just sitting on top of the locker. Familiarise yourself with a few topical corticosteroids that might be used to treat inflammatory dermatoses such as eczema. A mild corticosteroid is safe but pretty ineffective if you are dealing with a “good going” inflammatory rash. Moderate corticosteroids are safe and a reasonable choice for mild eczema. Use potent corticosteroids for short periods. Specify ointment or cream on your prescription. I suggest that you leave the ultra-potent class to the dermatologist unless you are quite sure of the diagnosis and management.

Dermatological knowledge and skills will help you and the patients you are managing. But if you ever need further assistance, your local dermatologists would be delighted to respond to a call for help – good luck!

Featured image credit: Dermatology by PracticalCures.com. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Dermatology on the wards appeared first on OUPblog.

Women in war – what is being done?

Women experience conflict differently to men, with its various and multiple implications, as refugees, internally displaced persons, combatants, victims of sexual violence, and political and peace activists. Their mobility and ability to protect themselves are often limited during and after conflict, while their ability to take part in peace processes is frequently restricted. But what is being done to change this? How can we better understand women’s roles and experiences, and what is being done to help protect and involve women in conflict zones?

The women, peace, and security agenda (WPS) is one such mission, consisting of eight United Nations Security Council resolutions that inject a gender perspective into various peace and security fora. This perspective calls for women’s participation in preventing armed conflict and in peacebuilding, as well as for the protection of women and girls in conflict. Discover more about the development of the WPS agenda, its development, resolutions, and progress – with the infographic below, with facts and analysis taken from the SIPRI Yearbook.

Download the infographic as a PDF or JPEG.

Featured image credit: The Life of Female Field Intelligence Combat Soldiers by Israel Defense Forces. CC-BY -SA-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Women in war – what is being done? appeared first on OUPblog.

Can hypnosis improve the functioning of injured brains?

Think about a situation in the past few years where your mind was at its very best. A situation where you felt immune to distractions, thinking was easy and non-strenuous, and you did not feel information-overloaded. If you take a moment, you can probably recall one such situation. As you think about it, you may even experience it actively right now and get a sense that you could be in that state again.

You have just read a suggestion. A suggestion is a piece of information that guides your thought in a particular direction. In the above, you thought about your past and then the present. You could have thought about ice cream or the US election, but you did not.

Hypnotic suggestion is a particular kind of suggestion, usually involving a heightened response to the suggestion itself, some degree of involuntariness, and a deviance from reality. Hypnotic suggestion can change our thinking in very fundamental ways, e.g. by de-automatizing psychological processes that were hitherto thought to be automatic. For this reason, neuroscience has recently seen a surge in interest in hypnosis, e.g. following the finding that the brain can be made indifferent to pain stimulation (analgesia) and that this effect can be reversed as well: that pain processing in the brain can be induced in the absence of stimulation. Hypnosis research seems to push the boundary for what processes can be moderated by top-down processing.

For this reason, researchers have been quite creative in their use of hypnosis, particularly in the early days of hypnosis research. A 1964 study by Fromm and colleagues suggested to healthy participants that they had suffered an organic brain injury. These “brain injured” participants were then subjected to a blinded neuropsychological assessment and a group of observing neuropsychologists were asked to rate, for each participant, whether they were brain-injured. The “brain injured” participants had a much higher organicity rating than non-hypnotized controls. Fromm concluded by speculating that this effect could be reversed: that brain-injured patients could be hypnotized to believe that they were not brain injured and that they should perform better under such conditions.

Now, 53 years later, this study has been carried out to specifically target working memory, the impairment of which is one of the most prevalent and invalidating sequelae following acquired brain injury across a wide range of lesion sites, severities, and durations since incidence. An impaired working memory probably feels the opposite of the situation you thought of in the beginning of this article. Such a feeling of distractibility, that thinking is unreliable and strenuous is well known to many of us at times, but many brain injured persons experience it chronically and to such a degree that work and social relationships cannot be maintained. Unfortunately, working memory has hitherto proven quite resistant to training and rehabilitation efforts so these sequelae are regarded as chronic.

As expected, patients scored much lower than the healthy population at baseline on two measures of working memory. However, after four sessions of hypnosis, they improved on both outcome measures to slightly above the population mean. In other words, as a group, they did not behave like brain injured patients anymore – at least not on these outcome measures.

Using active and a passive control groups as well as a cross-over, we identify that a large portion of this effect can be attributed to the contents of the suggestion rather than other factors involved, including hypnosis per se, retest effects, expectation effects, an unequal sampling of groups, spontaneous recovery, etc. That is, it makes a difference what suggestions are delivered. Also, the improvement in working memory performance did not deteriorate during a seven-week break, suggesting that it is long-lasting. Finally, the magnitude of the patient’s improvement was not affected by their age, type of injury, time since injury (1-48 years), educational level, and other factors. In other words, the data implies that hypnotic suggestion works equally well for everybody with an acquired brain injury.

These are obvious reasons for excitement. But, more importantly, there are many reasons to be skeptical. I have presented what can be concluded and what cannot be concluded from the paper itself elsewhere. With respect to clinical significance, the experiment only indirectly suggests that the effect is clinically relevant outside the laboratory, i.e. in everyday life. This remains to be shown directly.

With respect to belief, the theoretically deducted probability is very low that hypnotic suggestion improves working memory in a lesioned brain in just four weeks given our knowledge about brain injuries, neural plasticity, and the fact that many studies have used suggestion-like interventions in neurorehabilitation without observing this magnitude improvement. The effect of this low prior probability can be quantified. If you thought that the chance of success was one in a thousand (which could be justified), the experiment changes that belief to between one in three, and one in 25. In other words, if you were a very strong pessimist, you would not be convinced now. Extraordinary claims do, after all, require extraordinary evidence. But you may now be more curious and hopeful. If you were less skeptical a priori, you may feel more convinced by now. More data from replications and extensions will determine whether pessimism or optimism holds out in the long run.

The potential implications are large. Brain injuries constitute the second and third largest health care costs in the world, a large portion of which can be attributed to cognitive impairments. Furthermore, the results suggest that “chronic” cognitive impairment following acquired brain injury, although very real, is not as fixed as the name implies.

The post Can hypnosis improve the functioning of injured brains? appeared first on OUPblog.

“Nevertheless she persisted.”

Recently, we saw a male US senator silence his female colleague on the floor of the United States Senate. In theory, gender has nothing to do with the rules governing the conduct of US senators during a debate. The reality seems rather different.

The silencing of women ordinarily entitled to speak has often been the case during times of deep political acrimony. In March 415, a mob in the Egyptian city of Alexandria attacked and brutally murdered the female pagan philosopher Hypatia. Their grievance was a simple one. Hypatia had inserted herself into a conflict between Cyril, the bishop of Alexandria, and Orestes, the Roman governor in charge of the region, that had degenerated into city-wide violence. Hypatia was working with Orestes to resolve this incredibly tense and dangerous situation. To Orestes, collaboration with the philosopher Hypatia was a prudent step consistent with longstanding Roman tradition. To Orestes’s detractors, however, Hypatia’s gender and religion marked her as an outsider. She had intruded into a public controversy where she did not belong. Her voice needed to be silenced.

This murderous anger erupted against Hypatia despite the fact that Roman philosophers had been involved in moderating public disputes for centuries. The Roman world had long respected the wisdom and rationality of these figures. Since the late first century AD, everyone from Roman emperors to local city councilors accorded philosophers the freedom to give uncensored advice on public matters. Many philosophical schools came to expect that philosophers would be actively involved in guiding their home cities and fellow citizens. Hypatia herself had long played this role. She had hosted many Roman governors, Alexandrian city councilors, and important visitors at her home. She had also regularly given advice to these men in public.

Image Credit: Capitol-Senate, 25 May 2007 by Scrumshus. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Image Credit: Capitol-Senate, 25 May 2007 by Scrumshus. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.No other woman in early fifth century Alexandria had earned such access to power. Male authors were quick to explain that Hypatia’s influence resulted from her temperance and self-discipline, virtues they felt a woman who interacted regularly with such prominent men must possess. These men spoke at length about Hypatia’s virginity, even repeating a rumor that Hypatia once warded off a prospective suitor by showing him a used menstrual napkin. They clearly understood that Hypatia had to surrender some of her privacy in exchange for this extraordinary level of access.

Hypatia had earned this influence, but her position was fragile. It depended on a group of men continuing to agree that a woman should be given the sort of authority usually reserved for them. Hypatia might expect this recognition to endure during times of relative calm, but the tensions of 415 had produced toxic political dysfunction. Neither the bishop nor the governor trusted one another—and their supporters looked for someone to blame. For Cyril’s partisans, Hypatia was the perfect choice. She was a powerful outsider who suddenly seemed to exercise influence that far exceeded what a woman should. As tensions increased, discussion of why exactly a woman played so prominent a role started to emerge. Rumors spread that Hypatia’s influence with the governor came from sorcery not philosophy. Soon it was said that she had caused the entire conflict with the bishop by bewitching him. It was a short leap from there to the decision by Peter, a devoted follower of Cyril, to assemble a mob to silence Hypatia. While Peter likely planned only to use the threat of violence to intimidate Hypatia into silence, mobs are not easily controlled. When they found Hypatia unprotected, their anger became murderous.

Thousands of Roman philosophers, both famous and forgotten, played the same sort of public role as Hypatia in the first five centuries of Roman imperial rule. Only Hypatia was killed by a mob. It is impossible to say what role her gender played in her fate, but it is also difficult to deny that being a woman made her a target.

This points to a crucial and uncomfortable truth. It is far easier for societies to acknowledge and honor the achievements of prominent women during times of political calm, although, even then, publicly-engaged women endure scrutiny their male counterparts do not. During times of social stress these female leaders are often targeted in ways men are not. And yet, whether in fifth century Alexandria or twenty-first century Washington, these women do not stop speaking. Hypatia was undeterred by the slanders that made their way through Alexandria in the winter of 415. She continued playing the public role her philosophical convictions demanded. Her heroism in doing so stands unacknowledged by her male contemporaries. But this does not make it any less real. Hypatia had been warned repeatedly that her influence could be challenged, perhaps violently. Nevertheless, she persisted.

Featured Image Credit: Mort de la philosophe Hypatie, 1865. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post “Nevertheless she persisted.” appeared first on OUPblog.

APA Eastern 2017 annual conference wrap-up

Thanks to everyone who joined us at the annual meeting of the American Philosophical Association Eastern Division. We had a great time in Baltimore attending sessions and interacting with customers, authors, and philosophers. We’re looking forward to seeing you next year!

At the OUP booth we asked conference goers to tell us why philosophy matters to them, and we’ve included a few of their answers in the slideshow below along with photos from the conference.

Editor Robert Miller and Assistant Editor Alyssa Palazzo relax at the OUP booth.

Editor Lucy Randall and Assistant Editor Alyssa Palazzo chat with conference-goers.

Editor Robert Miller speaks with Steve Cahn at a panel about their 20 year collaboration on 17 philosophy texts.

Editor Robert Miller speaks with Steve Cahn at a panel about their 20 year collaboration on 17 philosophy texts.

"Why not?"

"In the age of Trump critical thinkers are needed now more than ever."

"To be able to distinguish true from false."

"How else could you criticize the foundations of your own civilization?"

"How else can we explore the world in which we live in?"

"What is the point of living? Of civilization? Not just for watching TV and other frivolous pursuits...what are we here for? Let's think about that together."

Featured image: Baltimore National Aquarium. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post APA Eastern 2017 annual conference wrap-up appeared first on OUPblog.

February 25, 2017

Facebook Cleanup: appearing professional on social media

With so much information available online, it’s easier than ever for employers to spot potential red-flags on social media profiles. In this shortened excerpt from The Happiness Effect, author Donna Freitas explains the “Facebook Cleanup,” and how university students are designing their profiles with future employers in mind.

The notion that we are using social media to police, spy upon, and subsequently judge our children, students, and future employees (however well-intentioned we might be in doing so) is rather chilling. In It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens, danah boyd alludes to a generational conflict around the idea of privacy, and that even posts that teens make in public forums like Facebook deserve to remain private from certain constituencies (namely parents), much like the diaries of old that teens kept to record their most secret thoughts and feelings. The widely accepted notion that all young adults today over-share and therefore don’t care about privacy is wrong according to boyd, and she argues passionately that we’ve misunderstood teens’ relationship to privacy—they do desire it, intensely so, and believe that it is inappropriate for “parents, teachers, and other immediate authority figures” to surveil them on social media.

But the college students I interviewed seem to have given up on the idea of retaining any semblance of privacy on social media forums attached to their names. They’ve accepted the notion that nothing they post is sacred and everything is fair game for evaluation by anyone with even the littlest bit of power over them—that these are simply the cards their generation has been dealt.

“For college students, the highlight reel is a social media résumé, usually posted to Facebook, which chronicles a person’s best moments, and only the best moments”

Hence, the Facebook Cleanup that so many of the students talked about at length has sprung up in response to the situation that young adults find themselves in today. A Facebook Cleanup involves going back through one’s timeline and deleting any posts that do the following:

Show negative emotion (from back when you didn’t know any better)

Are mean or picked fights

Express opinions about politics and/or religion

Include potentially inappropriate photos (bikini pictures, ugly or embarrassing photos, pictures showing drinking or drugs)

Make you seem silly or even boring

Reveal that you are irrelevant and unpopular because they have zero “likes”

Students who aren’t quite sure what to keep or delete can consult numerous news articles for advice. The term “Facebook Cleanup” is apt, since students’ fears are very much focused on Facebook rather than other social media sites. Facebook is so ubiquitous among people of all ages, that students consider it the go-to app for employers. As a result, it’s the social network where they feel they need to be most careful, and the professionalization of Facebook where they believe the creation of what they refer to as the “highlight reel” is most essential. For college students, the highlight reel is a social media résumé, usually posted to Facebook, which chronicles a person’s best moments, and only the best moments: the graduation pictures, sports victories, college acceptances, the news about the coveted, prestigious internship you just got. Students often organize their Facebook timelines to showcase only these achievements and use other platforms for their real socializing.

In The App Generation, Howard Gardner and Katie Davis briefly remark on the notion of a “polished,” “shined- up,” “glammed- up” profile, “the packaged self that will meet the approval of college admissions officers and prospective employers.” Students are indeed seeking control of public perception in a sphere where loss of control is so common and so punishing. Gardner and Davis worry that young adults’ belief that they can “package” the self leads to a subsequent belief that they can “map out” everything, to the point where they suffer from the “delusion” that “if they make careful practical plans, they will face no future challenges or obstacles to success.” This makes everyone disproportionately outcome-focused and overly pragmatic, especially in terms of careers, and less likely to be dreamers.

The students I interviewed and surveyed certainly are outcome-focused in their online behavior when it comes to pleasing future employers. But rather than giving the students a false sense of control, which Gardner and Davis find so worrisome, this focus seems instead to make them feel incredibly insecure.

And who can blame them?

“If they are completely absent from social media, this might seem suspicious, too—a future employer might assume the worst about them”

They are acutely aware of the precariousness of their reputations and the potential that their lives could be ruined in an instant. The students I spoke to clearly understand that they lack control because of the way they’re constantly being monitored online. This knowledge was central to nearly every conversation I had…

Appearing happy and positive in order to please potential employers was also of central concern to students. In the online survey, students were asked to reply yes or no to the following statement:

I worry about how negative posts might look to future employers.

Seventy-eight percent of the respondents answered yes. And, when asked about the dos and don’ts of social media, 30 percent said that the main advice they’ve received about social media was related to employment.

Most students feel that they are in a “damned if you do, damned if you don’t” situation. They worry about whether future employers might find an offending photo or post attached to their names. But many of them also worry about what happens if they have no social media presence at all for their future employers to scrutinize and dissect. If they are completely absent from social media, this might seem suspicious, too—a future employer might assume the worst about them (i.e., their photos and posts are so vulgar and unbecoming that they’ve hidden everything from the public). As a result, many students keep their Facebook pages updated with the highlight reel—a G-rated social media résumé that employers are welcome to peruse. As long as employers can find something, and that something is good, students believe they’ve done their social media homework.

Featured image credit: Image by Unsplash. CC0 via Pexels.

The post Facebook Cleanup: appearing professional on social media appeared first on OUPblog.

The globalization of the Hollywood war film

For a long time, people in other countries had to watch American war films; now they are making their own. In recent years, Russia and Germany have produced dueling filmic visions of their great contest on World War II’s Eastern Front.

Paid for with about $30 million in state money, Stalingrad, directed by Feder Bondarchuk grossed around $50 million within weeks of hitting Russian screens in October, 2013. Earlier that year, Our Mothers, Our Fathers was shown as a three part miniseries on German and Austrian television in 2014. On its final night 7.6 million Germans, 24% of all viewers, watched it.

The duty of the classic Hollywood war film is to make war meaningful. It orders events in a satisfying narrative, with the message that it was all worthwhile. Private Ryan had to be saved, so that America could live on and prosper after the war. War films like this try to shape public memory of the nation and its wars in particular kinds of ways. The idea is to reproduce in the future a conservative vision of the country and its patriotic values. Soldiers of the past, and their wartime sacrifices, are made to embody this vision.

To perform their function, and make for good entertainment, such films have to deliver up fantastical accounts of wartime events. While US filmmakers now go in for the hyperrealism of Band of Brothers and The Pacific, this is not so in Germany and Russia. In their quest to be ordinary today, these countries have to make the Eastern Front into something other than a monstrous catastrophe, at least on film. In doing so, what is most revealing is the violence these films do to wartime events.

Stalingrad starts off by turning the war into a disaster movie, as if it were out of human hands. Incongruously, the film opens with Russian aid workers rescuing German teenagers from a Tsunami-hit Japanese city. This move recoups in imagination some Russian pride from a far more economically advanced Germany. Sergei Bondarchuk viscerally connects his present day viewers to the battle of Stalingrad: one of the aid workers was conceived during the battle, and becomes the film’s narrator. Through this crudely literal but compelling cinematic maneuver, the battle is turned into the womb of the contemporary Russian nation.

As always with war films, gender is key. In the situation Stalingrad’s screenwriters set up, the role of the women is to sleep with the right men. Only in this way can the battle give birth to people of good character.

Fedor Bondarchuk on filming of Stalingrad by Art Pictures Studio. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Fedor Bondarchuk on filming of Stalingrad by Art Pictures Studio. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Stalingrad is loosely based on the defense of Pavlov’s House, a stout four story building which stood between German lines and a stretch of the bank of the Volga in the fall of 1942. Mostly under the leadership of Sergeant Yakov Pavlov, a platoon held out in the building for nearly two months before relief by counterattacking Red Army troops. One of the civilians, Mariya Ulyanova, played an active role in the fighting. In the film the Ulyanova character’s main job is to be protected by the men, in two senses. She must of course physically survive, but also her virtue must be guarded, at least until the appropriate moment.

For Bondarchuk, Sgt. Pavlov’s successful defense of his position was not sufficient cinematic grist. In a climax reminiscent of Saving Private Ryan, the final, apparently unstoppable German tank attack is defeated by the godlike intervention of air power (at least as rendered in English subtitles; the filmmakers may have intended artillery). Unseen Soviet planes (or guns) bomb the building and its environs into oblivion, killing all the film’s remaining characters in a 3-D sacrificial fete, but for Ulyanova.

A soldier in love with Ulyanova carries her to safety where they consummate the business necessary to the plot, before returning to sacrifice his life usefully in the final combat. In this morally sanctioned moment, Ulyanova survives, passing her values on to her son, the film’s narrator.

Our Mothers, Our Fathers also seeks to make death in war meaningful by meting it out according to scales of virtue. The brave officer brother who fights well until he turns against the war’s insanity survives. The sensitive, cowardly brother who later becomes a brutal killer chooses suicide. This tidily excuses viewers from apportioning responsibility for the character’s all too human acts.

The innocent and enthusiastic nurse, who makes a tragic mistake but later feels appropriately guilty, survives to marry the conscientiously objecting ex-officer. They are the upstanding national couple who, as in Stalingrad, go on to give birth to today’s citizens/viewers, the good Germans. The vivacious nightclub singer who takes up with a Nazi in order to save her Jewish lover is executed, not unlike Ulyanova’s counterpart.

Meanwhile, in a swipe at Germany’s eastern neighbor, the main purpose of the film’s Jewish character seems to be to show up Polish partisans as anti-Semitic. German death camps are nowhere to be seen in the film. The Anglo-Americans are almost entirely excused from their favored form of the delivery of mass death, for the film makes hardly any reference to the bombing campaigns that flattened and burned Germany’s cities.

Real war is capricious and democratic in the way it hands out suffering and death; there is no rhyme or reason as to why some die and others survive. This is why survivors are often tortured with inconsolable guilt.

On film, death in war is part of a rational and moral order. The bad guys mostly die, and if the good ones do too, their sacrifice is purposeful and worthwhile, not random. Only in this way can the war film become a vehicle to tell stories about the nation, about its purpose and meaning in the world.

Featured image credit: Infantry, Soldier, World War II by WikiImages. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The globalization of the Hollywood war film appeared first on OUPblog.

The poverty of American film

Some decades ago, British film scholar Laura Mulvey showed us that movies possessed a male gaze. That is, the viewer was assumed to be a man — a straight, white one — and films were created by men to entertain men like them.

We’ve made some progress. Among this year’s Academy Award nominees are eighteen African Americans, five Asian Americans, and one native-born Hispanic American. Three of the nine Best Picture 2017 nominees put African Americans at the center of their narratives (Fences, Moonlight, and Hidden Figures), as do three in the Documentary category (OJ: Made in America, I Am Not Your Negro, and 13th). One third of the Best Picture bracket have female leads (Hidden Figures, Arrival, and La La Land), and one (Moonlight) is concerned with matters of sexual orientation.

There’s still a long way to go, but this heightened attention to race (thanks in part to last year’s #OscarsSoWhite campaign) and gender (aided by ongoing research from the Geena Davis Institute) is all to the good. Yet while Hollywood has begun to confront its straight, white male gaze, it has yet to acknowledge its propertied gaze: While it’s still unusual to find big studio films about people of color, gays and lesbians, and women, it is even rarer to find ones that offer perspectives on the lives of poor and homeless people.

This is a long-standing problem. By my count, in the history of American cinema there are perhaps 300 films that deal centrally with those issues — even though the majority of us will be poor at least once over the course of our lives. Only two films even passably about poverty — My Fair Lady and Lady and the Tramp — can be counted among the 100 highest grossing US films, which offers one possible explanation for why more movies about people in need are not made: Perhaps that’s not what audiences want.

But it’s not just quantity that’s a problem, but quality, too, for even when filmmakers are trying to offer insight — even when they seem to mean well — they often wind up reinforcing pernicious myths and relying on clichés and tattered narrative tropes.

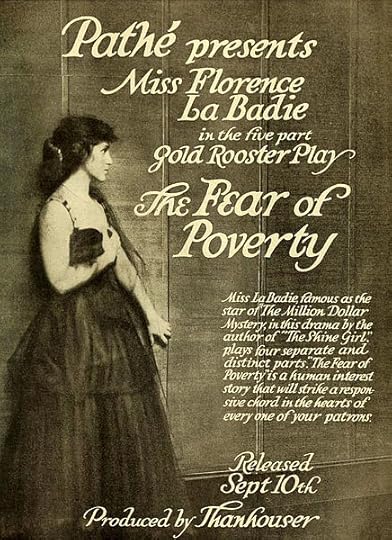

Advertisement in Moving Picture World for the American film The Fear of Poverty (1916) by Thanhouser Film Corporation. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Advertisement in Moving Picture World for the American film The Fear of Poverty (1916) by Thanhouser Film Corporation. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.2009 Best Picture contender, Precious, is a useful example. Its director, Lee Daniels, only the second black Best Director nominee at the time, nonetheless gave us a film that trafficked in the ugliest stereotypes of poor, African American communities, and the people in them. His nomination reflected not a recognition of diverse viewpoints and original storytelling, but a reward for conforming to age-old supremacist ideology. Perhaps it is no surprise that Daniels has disassociated himself from #OscarsSoWhite.

Even when films seem interested in these marginalized populations, they turn out not really to care much about them. Take The Soloist. Despite its marketing, this was not a story about the homeless musician played by Jamie Foxx, but one about how far the reporter played by Robert Downey, Jr. will go to rescue the poor man, and how the reporter is made better for having done so. When they are not tools to be used for others’ redemption, poor and homeless Americans are objects of fear (villains who will destroy the social order — Hobo with a Shotgun is an extreme recent case) or objects of pity (passive, pathetic souls with little agency — think of Robert DeNiro’s character in 2012’s Being Flynn). They are typically not mad about their condition, however, and the audience is not meant to be, either. We may feel sympathy, or even gratitude (there but for the grace of God go I), but seldom are we called upon to react with anger or indignation.

When a character is poor or homeless, that is ordinarily the most important thing about them, and when movies try to explain why people are in such a state, the causes are rooted in individual failure or a dramatic, tragic event. There is almost never a sense of the political and economic forces that create poverty and make it a common occurrence. Blaming people for their poverty serves a function, obviating the need for policy change or a reallocation of resources. It relieves us, the viewer, of the obligation to press public institutions to operate more equitably. It reassures us that the world is as it is for a reason, and even if things are grim for some, it’s ultimately their own fault or the hand of God. There is, either way, nothing to be done.

While Hollywood valorizes those who must undertake heroic efforts just to survive (think of Will Smith in Pursuit of Happyness), in reality, hard work and “grit” do not necessarily lead to improved circumstances. Most Americans in poverty don’t triumph against the odds – they succumb to them.

There are exceptions to these patterns in cinema of course, and one of this year’s Best Pictures, Moonlight, is among them. While young Chiron lives in public housing, his greatest challenge isn’t poverty, but his mother’s addiction and coming to terms with becoming a man and being gay. There’s no prurient gaze, no judgment. Hell or High Water, another Best Picture nominee, is among the few movies concerned with the effects of the recent economic crisis. The Great Recession hums in the background here (“Closing Down” “Debt Relief” “In Debt?” “Fast Cash When You Need It,” are among the roadside signs we see throughout) but the problems are deeper and older — these are folks who have been struggling for generations. So, when Toby (Chris Pine) robs banks, it is a small gesture toward balancing the scales: Banks have been robbing Americans like him forever, after all, and they are poor not for lack of effort but because the forces arrayed against them are so great.

The success of these films tells us that there is an audience for them. We should celebrate that, and encourage more filmmakers to follow their lead. And next year during Oscar season, when we ask how well women, sexual minorities, and people of color are represented, we should also ask how many fully realized poor and homeless people we find on the screen.

Featured image credit: film 8mm low light 15299. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The poverty of American film appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers