Oxford University Press's Blog, page 397

March 4, 2017

Paul Feyerabend and the debate over the philosophy of science

Paul Feyerabend (born 13 January 1924, died 11 February 1994) is best-known for his contributions to the philosophy of science, which is somewhat ironic because, I suspect, he wouldn’t have thought of himself as a philosopher of science. I don’t just mean he wouldn’t have thought of himself as just a philosopher of science. No, I mean that he thought of himself as a thinker for whom disciplinary boundaries meant absolutely nothing. In his later years, he even denied being a philosopher. But right from the time when he really found his feet as an independent thinker (independent of those philosophers under whom he had studied and worked), Feyerabend’s tendency was to range over enormous swathes of human thought, without regard to their supposed differences and boundary-lines. This is partly why in his books and articles one encounters not only the usual philosophical suspects, but a huge range of thinkers including scientists of every persuasion (of course), the Church fathers, the authors of the Malleus Maleficarum, historians, playwrights, poets, political thinkers, anthropologists, and astrologers. (It’s this quality of enormously wide intellectual range, I have to say, which first attracted me to his works). One of the reasons Feyerabend came to despise contemporary philosophy was undoubtedly that it no longer features, and perhaps can no longer really feature, the sorts of figures he most admired, such as his fellow boundary-striders Ludwig Boltzmann, Ernst Mach and Albert Einstein, for whom the expression ‘philosopher-physicists’ was invented.

It’s also ironic because although Feyerabend was a fervent admirer of certain scientists, he also supplied, or canonised, a perspective on knowledge which gives science no special or privileged place. This was cemented fairly early on in the book which made his name, Against Method (1975), in which he put forward the idea that there is no scientific method, partly because the greatest scientists have been nimble, opportunistic thinkers who, despite pretending to follow the kind of methodological rules that philosophers and science textbooks posit, were always prepared to cast them aside when they got in the way. Although Feyerabend had some influence on important figures within the philosophy of science, such as Bas van Fraassen, Ronald Giere, and John Dupré, the real impact he made was outside philosophy, since he became known in other disciplines as an ‘epistemological anarchist’, and the idea that a philosopher of science could have that reputation gave impetus to relativistic tendencies of many different kinds outside philosophy, for example in archaeology.

Paul Feyerabend enjoying a stroll in Rome, Italy. Attributed to Grazia Borrini-Feyerabend via Wikimedia Commons.

Paul Feyerabend enjoying a stroll in Rome, Italy. Attributed to Grazia Borrini-Feyerabend via Wikimedia Commons.This reputation itself gave rise to the accusation that Feyerabend was ‘the worst enemy of science’ (Theocharis, T. & Psimopoulos, M., “Where Science Has Gone Wrong”, Nature, 1987, p.596). He certainly didn’t mean to be that, and his fans have enthusiastically sought to defend him from this accusation. One can see where the critics are coming from, though. For the way in which Feyerabend envisages evaluating science is somewhat unusual. His work seems to disallow, or at least discourage, any attempt to evaluate different approaches, including science, in genuinely epistemic terms. That is, he was deeply sceptical of any attempt to say that one approach, or theory, constituted knowledge where another was mere opinion. And this scepticism extended, I believe, even to much more qualified terms of epistemic appraisal, such as claims that one approach or theory was better epistemically justified than, or more probably true than, or even just closer to the truth than, another. However, this doesn’t mean that Feyerabend envisaged no way of evaluating approaches. Rather, he encouraged us to evaluate approaches, including science, in terms of their contribution to human happiness. I worry that although one might apply this suggestion at a very general level, to the comparative evaluation of world-views, it doesn’t really tell us anything about how to evaluate different theories within science.

I also worry that as well as being too hard on science (since some people will inevitably reject science on its basis), Feyerabend’s suggestion is also too soft on it. Feyerabend was, especially in later works such as The Tyranny of Science (2011) a foe of ‘scientism’, the belief that science has the resources to answer all significant human questions. But because of his marked allergy to disciplinary boundaries, he didn’t have one of the main planks of what I think of as the most plausible case against scientism, the idea that there are very different kinds of questions, and thus that considerations from one field can’t always be used to address questions in another field. Those of the scientistic persuasion, though, can quite well argue that, having plumped for the scientific world-view on the basis of its contribution to human happiness, they not only accept it in its entirety but also that they find this world-view capable of answering all meaningful questions. In other words, scientism seems to be able to legitimise itself in terms of Feyerabend’s suggestions.

Thus, I find myself torn between admiration for Feyerabend, and the feeling that his philosophy can’t really supply ammunition against those who, like some leading contemporary advocates of the most militant kind of scientism and atheism, think there are no real questions outside science or against those who, like Steven Hawking, think philosophy has been superseded by science.

Featured Image credit: Title page of Malleus Maleficarum (Hammer of Witches) by H. Institutoris, a widely-read medieval text on the extermination of witches. Wellcome Images, CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Paul Feyerabend and the debate over the philosophy of science appeared first on OUPblog.

March 3, 2017

Michelangelo’s uncelebrated birthday and uncertain death

We will scarcely acknowledge, much less celebrate, the unremarkable 502nd anniversary of Michelangelo Buonarroti’s birth. Nor would Michelangelo. While the aristocratic artist was alert to the precise time and date of his birth, he paid absolutely no attention to any of his subsequent birthdays.

Michelangelo was born on 6 March 1475. According to the Florentine calendar which recognized March 25 (Annunciation to the Virgin) as the beginning of a new year, Michelangelo was born in 1474, some three weeks shy of 1475. The discrepancies between calendars—the one observed by Florentines and the reformed calendar of Pope Gregory XIII which began the New Year on January 1—spawned long-time confusion. An example is the fact that there are four slightly varying accounts of Michelangelo’s birth date. Thanks to the careful work of scholars we have a reasonable explanation for these discrepancies. It’s still true, as astrologer Don Riggs has demonstrated, that Michelangelo may have abetted the confusion. The artist was not born under Saturn, the astrological sign most associated with creative individuals, but under a mediocre configuration of planets, dominated by Mars. Through his biographer, Ascanio Condivi, Michelangelo encouraged the belief that he was born with a more favorable natal chart, which better predicted the course of his brilliant career. In this, Michelangelo was behaving like many of his famous contemporaries. For example, Marsilio Ficino and Lorenzo de’ Medici both made certain that astrology retrospectively predicted their illustrious lives.

Statue of Michelangelo in Florence, Italy. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Statue of Michelangelo in Florence, Italy. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.But other than manipulating his natal chart, Michelangelo remained uninterested in birthdays. Of the more than 1600 extant letters to and from the artist over the course of some 70 years, as well as more than 300 miscellaneous records (ricordi), not one makes reference to the fact of his birthday. But was a birthday important? In Renaissance society, the feast day of one’s namesake saint might be an occasion for public and/or personal celebration. Michelangelo was born on March 6, the feast day of an obscure Bishop of Tortona, San Marziano, who was martyred in the second century CE. Marziano is of little importance—then and now—to persons outside the parochial ambiance of Alessandria in northwestern Italy. Michelangelo may have been born on San Marziano’s feast day, but he was named after the Archangel Michael, whose feast day is 29 September. There is no evidence that Michelangelo celebrated either his birthday saint or his namesake’s feast day. Indeed, he and his contemporaries proved remarkably inattentive to birthdays and often erred in declaring their age. In 1560, Leone Leoni cast a medal of Michelangelo with an inscription claiming the artist to be 88 years old: he was 85. When the Frenchman Blais de Vignère visited Michelangelo in Rome in 1549, he recorded that the artist was “more than 60 years old”; in fact, he was 74.

Michelangelo and his contemporaries may have manipulated the facts of birth and proved careless regarding age and birthdays, but they had scant control over death’s inexorable finality. Yet here too, death could be elusive. When still in his thirties Michelangelo, who equaled Mark Twain in possessing a dry wit, began a letter to his father: “I learn from your last that it is said in Florence that I am dead. It is a matter of little importance, because I am still alive.” Nonetheless, from about this time, Michelangelo began expecting to die and continued in this expectation for the next half century. When it finally arrived, his death was carefully noted, but variously. Despite the Renaissance penchant for record keeping, the length of Michelangelo’s life and the date of his death were confusingly reported, even by those who cared most.

Shortly after Michelangelo’s death, his nephew, Lionardo Buonarroti, noted that on Friday, 18 February, his uncle “died in Rome, having lived 88 years, 11 months, and 14 days.” However, this is an inherently contradictory statement. If Michelangelo died on 18 February, then he had lived 88 years, 11 months, and 12 days. If, on the other hand, he lived 14 days then this would suggest that he actually died on 20 February. Giorgio Vasari records that Michelangelo died at the twenty-third hour of 17 February 1563, which, according to the Roman reckoning, would be the afternoon of 18 February 1564, the date that most scholars accept. However, the inscription on Michelangelo’s tomb states that he lived 88 years, 11 months, and 15 days, which would indicate that the great man had died on 21 February. These discrepancies are not terribly significant and probably can be logically explained; nonetheless, they reveal something of Renaissance notions of historical accuracy. The real surprise is that Michelangelo’s closest living relative, his biographer, and his tomb inscription all state slightly different “facts” with seemingly unassailable precision.

Given such attitudes, Galileo Galilei had no compunction in claiming that he was born on the day of Michelangelo’s death, thus reinforcing a pervasive contemporary belief that genius never dies but passes from one brilliant individual to the next. The conjunction between the two geniuses was enshrined in stone when the monument to Galileo was erected directly opposite that of his predecessor in the basilica of Sta. Croce in Florence. When next in Florence, pay homage to these two Florentine geniuses, but do not worry much about their birth and death dates.

Featured image credit: Michelangelo’s Creation of Adam on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Michelangelo’s uncelebrated birthday and uncertain death appeared first on OUPblog.

The critical role of China in global tobacco control

Many might think that the best way to reduce the global tobacco epidemic is by health education and banning sales to minors – policies well-liked by teachers, parents, and governments. But these are ineffective means of reducing smoking prevalence. Surprisingly, it is a fiscal measure that is the critical and easily the most important means of improving public health, as by raising the price, cigarettes become less affordable, especially to the young.

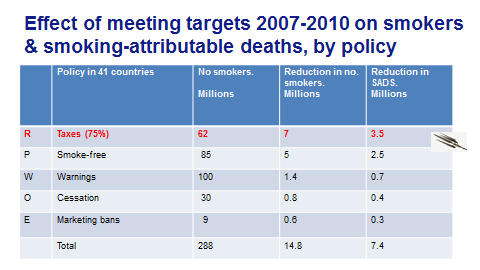

In a 41 country study by David Levy et al, tobacco taxation headed the list as the best way of reducing the numbers of smokers and hence reduction of smoking deaths. Second was the creation of smoke-free areas, third: pack warnings, fourth: offering help to quit tobacco, and fifth: bans on tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship.

‘Effect of meeting targets 2007-2010 on smokers & smoking-attributable deaths, by policy table’. Used with Author’s permission.

‘Effect of meeting targets 2007-2010 on smokers & smoking-attributable deaths, by policy table’. Used with Author’s permission.This is confirmed by the tobacco industry ‘Scream Test’: the industry will ‘scream’ by undermining, attacking, obstructing, and intimidating governments with legal and trade threats for any measure likely to be effective (such as tax, smoke-free, plain packaging, large graphic warnings). It is telling that they positively support schools education and a ban on sales to minors – indicating that these are indeed the least effective measures.

How does this knowledge apply to tobacco control in China, the world’s largest producer and consumer of tobacco? It is staggering to think that one in every three cigarettes smoked in the world today is smoked in China. Certainly no improvement in the global tobacco epidemic can ignore what is happening in China.

Although knowledge and action on tobacco began in the 1980s with the first national prevalence survey and a conference on tobacco held in Tianjin, followed by dozens of research papers, conferences, and exhortations to action from both within and outside China, the key action areas of tax, smoke-free areas, and warnings have not been implemented in any effective way. Tobacco tax remains extremely low; there is no national smoke-free law (a draft is still languishing between various government bodies, although promised in 2017), and China is extraordinarily reluctant to introduce any graphic pack warnings, claiming these would be insulting to the beautiful pictures of China that appear on many of the packs!

This is in spite of the fact that over a decade ago, China ratified the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC), and is therefore under international obligation to introduce tobacco control measures.

HKsmoking5000fine. Own work. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

HKsmoking5000fine. Own work. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Given the enormity of the epidemic, the ill-health, the more than one million annual deaths caused by tobacco already evident in China, and tobacco being a huge economic burden on the economy, why is this?

The biggest tobacco company in the world is the Chinese government, and the state-owned tobacco industry remains a major obstacle to tobacco control. It is not only responsible for the tobacco industry, but the WHO FCTC mechanism in China is still led by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, which also oversees the China Tobacco Monopoly Administration. This represents a major conflict of interest within the Ministry, which thus far has been extremely detrimental to tobacco control.

The monopoly has increasingly adopted a more aggressive stance on obstructing tobacco control, much like the tactics of the transnational tobacco companies, as shown by the World Health Organization in 2012.

However, there are glimmerings of hope. In the last few years, tobacco control efforts have begun to accelerate beyond expectations. The triggering event was the publication on tobacco by the Chinese Central Party School, the ideological think tank of the Communist Party, followed by a spate of activity: directives to government officials; regulations issued by the Ministry of Education, the People’s Liberation Army, and the Healthy City Standards; tobacco clauses in national advertising and philanthropy laws; the creation of a Smoke-free Beijing (and Shanghai in March 2017); a modest increase in tobacco taxation; and the national smoke-free law currently in draft.

To contribute to the global movement in tobacco control, there is a crucial need for China to build upon these recent developments in accepting the economic research evidence of the debit of tobacco to the economy. China should recognize the studies that show farmers can earn more by switching to other crops. The central government must implement robust, comprehensive legislation as well as increasing cigarette price through taxation. Most challenging of all, China must work to tackle the power and influence of the state tobacco monopoly over tobacco control.

Featured image credit: ‘Smoking’ by Олег Жилко. CC0 Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post The critical role of China in global tobacco control appeared first on OUPblog.

Oral history and empathy at the Women’s March on Washington

Today we continue our series on oral history and social change by turning to our friends at the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program (SPOHP) at the University of Florida. A group of SPOHP students and staff traveled to the Women’s March on Washington this January as part of an experiential learning project. Their recordings captured a snapshot of a divided America, and the project aims to use oral history to encourage empathy. Check out the reflections from two members of the project below, and enjoy their special podcast from the march below.

Holland Hall:

One of the most spontaneous interactions I experienced during our three-day fieldwork trip to Washington, D.C., to document the Women’s March on Washington occurred in the lobby of our hotel in Arlington, Virginia. On the night of President Trump’s inauguration, while we were discussing our fieldwork strategies for the following day in our hotel lobby, a woman stuck her head in our circle to ask, “Are you all protesting tomorrow?” Enthused by her interest in our group and feeling her excitement for the Women’s March on Washington the following day, I greeted the woman, Alyson Aleman, and informed her that we were a research group from the University of Florida. After hearing that we were in Washington to document the inauguration and Women’s March, she told me about her family and how extraordinary of a moment this was for her parents specifically.

Her parents had been divorced for over two decades, and her family’s trip to the Women’s March on Washington was the first time they were coming together as a family for an extended period since separating. Meeting this family and hearing their story not only hinted at how momentous of an event the march was going to be, but this introduction also beautifully displayed the oftentimes whimsical nature of oral history research. We were able to sit with three generations of this Connecticut family to gather their thoughts regarding the overall 2016-election cycle and why they were compelled to attend the Women’s March on Washington in response to the election of Donald Trump.

What made this interview so enjoyable for me to conduct as a researcher was creating this recording with a family during such a momentous time for not only the nation, but for their family. Ms. Aleman also brought her young daughter along to the march to instill in her that she is able to own her voice and to express her opinions freely. Another striking point Ms. Aleman brought up during our interview was the importance of the work we were doing as a research team, and how such material can be used to inspire the primary ingredient for social change: empathy.

While the family discussed the many ways empathy can be encouraged, Ms. Aleman’s husband, Karl Odden, actually highlighted where oral history comes in to play in the process of building empathy for others. Mr. Odden spoke about needing to walk in someone else’s shoes in order to gain authentic empathy for others from different walks of life. He noted that self-educating on the lived experiences of others is the most effective way to gain the understanding necessary to be able to empathize with others. Our research team sought to collect diverse perspectives from a broad spectrum of identities in the hopes that this digital material can be used to educate and inspire, as well as assist in the collective goal to build more empathy for one another as a nation.

It was 19 January, and my group had just finished our first day of fieldwork in Washington, DC. As the streets began to darken, we stumbled, sore and tired, into a food court next to the National Press Club. We’d passed a few people dressed up in prom attire – “They’re celebrating the inauguration, they’re holding parties,” my colleague Marcela explained – but hadn’t quite realized that we were directly next to the largest inaugural ball event in the city. When we emerged from the food court, we stepped into the protest burgeoning outside of the “DeploraBall.”

Alexandra Weis:

Frantically, we sprang into action, trying to capture as much footage as possible. We filmed as protesters used a floodlight to project the words: “Impeach the Predatory President! Bragging About Grabbing a Woman’s Genitals” on the otherwise pristine and sculpted face of the National Press Club. Nearby, someone inflated a giant white elephant labeled “RACISM.” The energy in the crowd of hundreds was urgent – people were palpably frightened, outraged, and desperate. We spoke to several members of an anti-fascist group shouting ill omens of the inauguration day to come. We interviewed a queer transgender woman who defiantly held up a trans pride flag against religious extremist counter-protesters. Amid the chaos, the interviewees made their concerns known: Trump and Pence are illegitimate, they emphasized over and over. Protect marginalized folks, they insisted. They were people for whom these issues were undeniably real; their lives were political not because they sought out politics, but because for them, there was no alternative to social justice.

For me, this was not only the first day of fieldwork for our trip, but the first day of fieldwork ever. As a graduate student in Gender Studies with a background in psychology, I had little experience doing hands-on research. I was passionate about social justice in my everyday life, but struggled to incorporate it into my academic practice. This first day threw me headfirst into the oral history process. People were struggling to be heard, crying out about the ways they were hurting. When I asked what brought them to the protests, people told me repeatedly and almost unanimously: they were scared for themselves, but also for their neighbors and their country. Given a platform, they were eager to explain their perspectives. As Audre Lorde wrote in her poem A Litany For Survival: “When we speak we are afraid our words will not be heard, nor welcomed. But when we are silent, we are still afraid.” The act of speaking out can be revolutionary, but it is our job as scholars to openly listen and welcome the raw honesty, turmoil, and complexity that accompanies the moment in social movement history.

These reflections and recordings are part of the larger Women’s March on Washington Archives project, run by the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program and others at the University of Florida. For more from SPOHP, find them on Facebook, Twitter, or their homepage. To submit your own piece on oral history and social change, check out our CFP.

Featured image credit: “Alex and Celina” by Holland Hall, from the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program at the University of Florida, used with permission.

The post Oral history and empathy at the Women’s March on Washington appeared first on OUPblog.

Do you need to “unplug” from social media? [quiz]

“Unplugging” from social media does not necessarily equate to quitting. As The Happiness Effect author Donna Freitas found out, the decision to temporarily quit social media is a common among university students. Some students quit because they feel “too obsessed” or “addicted,” while others cite online drama as their reason to take a break.

“I went to bed on Instagram, I woke up on Instagram, and I most likely went to the bathroom looking at my Instagram. That’s why it had to stop. No object or person should have that type of stronghold on you” —Zooey, first year, evangelical Christian college

To celebrate National Day of Unplugging, we’ve put together a quiz that answers the question: Do you need to “unplug” from social media?

Featured image credit: Untitled by TeroVesalainen. CCO via Pixabay.

The post Do you need to “unplug” from social media? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

10 things you should know about weather

From the devastating effects of tornadoes and typhoons to deciding the best day for a picnic, the weather impacts our lives on a daily basis. Despite new techniques and technologies that allow us to forecast the weather with increasing accuracy, most of us do not realise the vast global movements and forces which result in their day-to-day weather. Storm Dunlop tells us ten things we should know about weather in its most dramatic and ordinary forms.

1. Tornadoes

Reports on TV, radio, and the newspapers often describe British ‘tornadoes’ that cause extensive damage. But these are not true tornadoes, which are much stronger and exceptionally rare in Britain. These events are more properly called ‘landspouts’, a term introduced because the phenomena are closely related to waterspouts – waterspouts become landspouts if they come ashore.

These whirls arise when there are powerful updraughts and downdraughts within moderately common clouds. True tornadoes form differently within vast thunderstorm systems that are organised into giant rotating columns of air.

2. Ozone hole

Ozone (O3) is a harmful gas, unwanted at ground level, but forms naturally in the high atmosphere, where it protects the surface from dangerous ultraviolet radiation from the Sun. Certain man-made chemicals destroy the ozone layer and produce ozone ‘holes’ Luckily, international agreement (the Montreal Protocol) governs the elimination of the harmful chemicals and there are signs that the ozone holes are decreasing.

3. Polar vortex

A polar vortex is a system of high-speed winds that surrounds the pole in each hemisphere, and isolates the polar region from air closer to the equator. The southern polar vortex is particularly strong, and is the main reason for the large size of the southern ozone hole. Warm air from middle latitudes cannot penetrate into the polar region. (In the north, the polar vortex is more variable, and any ozone hole is less pronounced.)

When the northern polar vortex is strong, cold air is confined to the polar region. When the winds weaken, the location of the northern polar jet stream becomes greatly variable, with waves extending to lower latitudes, so frigid arctic air spreads down to temperate regions.

4. Greenhouse effect

People sometimes regard the greenhouse effect as a ‘bad thing’, but without the greenhouse effect we would not be here. The atmosphere acts as a giant ‘blanket’, keeping the Earth warm with an average surface temperature of about 14°C. Without the atmosphere, the surface temperature would be around -18°C, much too cold for life.

5. Butterfly Effect

The Butterfly Effect is often quoted (wrongly) as illustrating how small events may have far-reaching consequences. The famous phrase ‘Does the flap of a butterfly’s wings in Brazil set off a tornado in Texas?’ was chosen by a conference organiser. The author, Edward Lorenz, actually discussed the impossibility of being absolutely certain of the outcome of any calculations about the weather: that there are limits to predictability. The technical term is ‘Sensitive-dependence on initial conditioning’ and the effect applies to many other areas of science. That original title could have been ‘Predictability: does the flap of a butterfly’s wings in Brazil prevent a tornado in Texas?’

NASA Rapid Response System September 04, 2003 Low off iceland by NASA. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

NASA Rapid Response System September 04, 2003 Low off iceland by NASA. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.6. Jet streams

Jet streams are narrow currents of high-speed winds in the upper atmosphere at altitudes of about 10 km, thousands of kilometres long, hundreds of kilometres wide, and a few kilometres deep. They have significant effects on depressions at the surface, which they may intensify or weaken. Waves in the jet streams greatly affect the weather at the surface and may occasionally lead to ‘blocking’ situations, where high- or low-pressure systems (and the accompanying weather) remain stationary over an area for a long time.

7. Atmospheric rivers

Streams of very warm, humid air, called ‘atmospheric rivers’ transport vast quantities of warmth and moisture from tropical regions towards temperate zones. When atmospheric rivers strike mountainous regions they may produce vast quantities of rain. It was an atmospheric river that caused the downpour and flooding in Cumbria in 2009, and another has caused the recent flooding in California.

8. Bombs

The pressure in the centre of a depression occasionally drops dramatically. If it decreases by more than one hectopascal (one millibar) per hour for 24 hours, the system is known as a ‘bomb.’ One bomb occurred on 8 January 1993. By 10 January, it was the deepest depression ever recorded over the North Atlantic. The weather forecast that day remains unique, with the words: ‘Rockall, Malin, Hebrides, Bailey. South-west Hurricane Force 12 or more.’

The wind and waves from this storm completely ruptured the tanker Braer, driven ashore on Mainland, the largest island in the Shetlands, by an earlier storm. The oil caused an environmental disaster. The violent system is now known as the ‘Braer Storm.’

9. Centres of action

Nearly everyone is familiar with the terms ‘Azores High’ and ‘Icelandic Low.’ Technically, these are ‘centres of action’ in that they are semi-permanent areas of high or low pressure that are important features in the global circulation of air.

The Azores High is nearly always present, and often extends ridges high pressure outwards, usually bringing fine weather to Britain and western Europe. The Icelandic Low (rather like the corresponding North Pacific Low) is not so permanent, but gains its name from the fact that low-pressure systems (depressions) frequently pass across the area.

10. Hurricanes

When Bernard Shaw’s play Pygmalion was turned into a film, a language exercise for Eliza Doolittle was ‘In Hampshire, Hereford, and Hertford, hurricanes hardly ever happen.’ But hurricanes never happen in Britain. The reason? Simple: the sea is too cold. For hurricanes to form, the sea-surface temperature needs to be at least 27°C. That only happens in the tropics. The technical term for hurricane, typhoon, and cyclone is ‘tropical cyclone.’

Featured image credit: Supercell Chaparral New Mexico by tpsdave. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post 10 things you should know about weather appeared first on OUPblog.

March 2, 2017

Where your mind goes, you go? (Part 2)

If your brain, along with your memories and personality, is transplanted into another human body, would you now inhabit that new body? If someone was in a car accident and suffered amnesia, can we still consider that to be the same person? On 23 February, Michelle Maiese shared her ideas about the connection between the psychological and biological self. Below, Michelle continues a deeper exploration into human existence and questions which factors make up our personal identities.

The dominant approach to personal identity says that a person persists over time by virtue of facts about psychological continuity. However, this approach faces a so-called duplication problem: a single person can be psychologically continuous with two or more persons. Derek Parfit’s solution is to suppose that what we care about in survival is psychological continuity and connectedness, which is a form of continued existence that does not imply identity through time. Even when psychological continuity is lacking, though, we still might regard someone as the same person in a moral and legal sense, due to the persistence of their living body, suggesting that our perception of survival is both biological and psychological.

Is there some other way to resolve the duplication problem that acknowledges this insight? Remember that according to Parfit, we all agree that if my brain is transplanted into someone else’s brainless body, and the resulting person has my character and apparent memories, then this resulting person is me. But should we agree, or do these intuitions rest on questionable assumptions?

It is worth noting that the very way in which the thought experiment is framed presupposes that an individual’s psychology can come apart from her body and that psychological continuity is separable from the continuity of the living body. This assumption is evident again in Parfit’s later work when he discusses the surviving head case: imagine that your head and cerebrum are detached from your body, attached to an artificial support system, and then later grafted onto another human body. Parfit maintains that you, the very same conscious being, would exist throughout; it’s just that you would switch from being the thinking, controlling part of one human animal to being the thinking, controlling part of a different human animal. Here Parfit identifies the person as the part of the animal that does the thinking, namely the part whose physical basis is the cerebrum.

Image credit: Brain by FotoEmotions. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

Image credit: Brain by FotoEmotions. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.But can our psychological profiles truly be prized apart from our bodies, and is it true that “the body below the neck is not an essential part of us”? Like so many philosophers, Parfit seems committed to what Andy Clark has labelled “a BRAINBOUND view of the mind“. The working assumption of BRAINBOUND is that mind and cognition are disembodied computational processes taking place in the brain. While the non-neural body does act as the sensor and effector system of the brain and central nervous system, neural activity is only ‘instrumentally dependent’ on human bodily activity. Cognition, on this view, is simply a matter of computing information according to the brain’s internal rules that then instruct the body how to act. According to BRAINBOUND, where your brain goes, you go.

However, recent work on embodied cognition challenges this prevailing view that mentality is a purely neural phenomenon. To claim that mindedness is fully embodied is to suppose that the capacity for consciousness and cognition are spread throughout our living bodies, and also shaped and structured by the fact of our embodiment. But if mind and consciousness are fully bound up with bodily dynamics, and the mind is not simply a set of contents that can be transferred from one brain to another, then it is not possible, as so many theorists have supposed, that one could undergo a sudden body transplant and still count as oneself. Nor would it be possible for one’s stream of consciousness to continue smoothly, its subjective character remaining much the same, if it were housed in a succession of distinct bodies.

Obviously, this is not to deny that the brain plays a crucial role in one’s mental life! However, it would be a mistake to suppose that one’s brain “stores” one’s memories and character traits, or that the brain can be isolated as the source of all of someone’s cognitive achievements. If the mind is fully embodied, then there simply is no way to extract your mind, implant it in a different body, and have you persist as one and the same person. To acquire a whole new living body would be to acquire a new set of operative neurobiological dynamics, which would so radically change the nature of consciousness that it’s unclear such a being could be just like you, psychologically speaking.

Such considerations suggest that what matters in survival is both psychological and biological, and that understanding personal identity across time requires that we appreciate how the psychological aspect of existence is fully bound up with our whole living bodies.

Featured image credit: Spirit by Josh Marshall. CC0 Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post Where your mind goes, you go? (Part 2) appeared first on OUPblog.

A paradoxical stroll down Harlem’s memory lane

“It’s a big leap from working class, to Ivy League schools, to being a tenured professor. And a part of that leap and apart from its specificities are the sense and awareness of precarity; the precarities of the afterlives […] the ongoing disaster of the ruptures of chattel slavery.”

— Christina Sharpe, from In the Wake: On Blackness and Being

“What happens to a dream deferred? […] Does it explode?”

— Langston Hughes, from his poem “Harlem”

It has been nearly nine years since I moved to Southern California, after a lifetime in New York City as the adopted daughter and granddaughter of a Harlem-born and raised black family whose “roots” were in Richmond, Virginia (by way of the Middle Passage from, as author Dionne Brand describes it in A Map to the Door of No Return, “the door of no return”). I visit the city a couple of times a year, to check in with loved ones and to do research. One particular visit there not long ago brought with it a riveting encounter. I took the subway up to Harlem for a visit to the late Dr Barbara Ann Teer’s National Black Theatre. When I ascended from the subway, I stood outside, noting the dramatic changes that had taken place on 125th Street and Lenox Avenue (renamed Malcolm X Blvd in 1987) since I’d left New York, and certainly, since my family members had been born and raised there shortly after the turn of the twentieth century. Most notably, Starbucks loomed large, along with an array of higher-end clothing stores and boutiques, which seemed to have replaced many of the affordable bargain basement clothing stores and bodegas that had peppered 125th Street for years. The shock of gentrification’s encroachment must have registered loudly on my face, for a young man walking toward me said, “Yeah…we’re handlin’ it,” as he continued past me. My initial reflex was to laugh out loud; it was such a New York moment. But there was something else subtending the encounter. His was a studied critique of a change in progress that he knew was not for or about him, a black resident of Harlem who had to endure its inevitable unfolding.

Portrait of poet Langston Hughes in 1942 by Jack Delano. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of poet Langston Hughes in 1942 by Jack Delano. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.My (adoptive) maternal grandfather worked for the Department of Sanitation when the garbage “trucks” were still horse-drawn carts. After my diabetic grandmother’s death in childbirth, my grandfather and his surviving six children were forced from one Harlem brownstone flat to another—by untenable vermin infestation, or by immigrant landlords who were selling their properties out from under my and other black families, treading the current of white flight out of Harlem because blacks were increasingly seeking affordable refuge and a semblance of community there.

My grandfather’s municipal job enabled my family to stay a paycheck beyond poverty’s crushing grip. There was one point in time during which such a feat appeared even more Herculean: it was during the Great Depression, when middle and upper-class white Europeans experienced, by dint of an economic anomaly, the destitution that was but one facet of the perennial reality of black life. That my grandfather was a civil servant became the saving grace of not only his, but several neighboring black families for whose children he was able to provide a meal or two a couple of times a week. His steady paycheck (courtesy of the fact that, no matter how out of tilt the fallen stock market had rendered the nation, the trash had to be picked up) afforded him bread, milk, salad greens, and soup stock. These, along with the block of surplus processed cheese and canned meat that the government supplied to all (many swore it was horse meat), could feed a modest crowd.

But my grandfather’s presence in civil service also nearly got him killed. His was a fair complexion, such that he was often mistaken for an “ethnic” white—from the Mediterranean, perhaps. He didn’t try to pass, so much as non-black people took him for what they assumed, or needed, him to be. Black folks knew, without need of much discussion, that our array of hues tells a deeply complicated tale. But some of his coworkers became suspicious—of a certain something in his walk, in his cadence—and followed him to Harlem on a couple of occasions, to discover a wife who was anything but fair, and children who split the difference. One day, several of those European immigrants and immigrant-descended coworkers beat my grandfather unmercifully, and left him in an alleyway to die. He did not; at least, not then. But I imagine his brush with death by coworker for the “crime” of being gainfully employed while black steeled him to two harsh realities: (1) blackness did not enjoy the privilege—the dream—of an immigrant work ethic that incorporates one into the American project; and (2) blacks may have worked just as hard as, if not harder than, anyone else, but their labor was part of a continuum constituted by slavery’s marking—the precarity of slave descent to which Christina Sharpe alludes.

As Harlem continues along its gentrification trajectory in this new era, its faces increasingly whiter, middle-class and higher—mirroring the neo-bohemian influx that is currently proliferating in Detroit—the advent of #BlackLivesMatter continues to soar across urban centers around the nation, including Harlem. These protests against anti-black violence, most notably by the police state, pique an urgent question: what exactly is the dream that animates the gentrification projects of today? I would venture to say it is not Dr Martin Luther King, Jr’s dream, but rather, its antagonist. For his dream is precisely that upon which Langston Hughes’s poem, “Harlem” meditates. Hughes’ first line, “What happens to a dream deferred?” prompts us to examine what such deferral really means, and anticipates Sharpe’s formulation of rupture and its persistence in and to black life, regardless of our station. And so, the memory of that young man will stay with me always, for he remains there, in Harlem, ever vulnerable, yet taking notes, vigilant, critiquing, and rendering his fugitive commentary amidst the precarity of gentrification’s overwriting.

Featured image credit: Night view of the Apollo Theater marquee in the late 1940s by William P. Gottlieb. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post A paradoxical stroll down Harlem’s memory lane appeared first on OUPblog.

Transformative social work education: the time is now

In the first week of March, hundreds of social work educators from across the US will come together in New Orleans to discuss the future of social work education at the Association of Baccalaureate Social Work Program Directors (BPD) conference. It is clear that the stakes for social work education are higher now than ever before. For my students who are working in field placements in health, education, and social services sectors, there is a growing sense of dissonance between the values of human rights and human services on the one hand, and bottom-line, outcome-driven work environments, on the other. This dissonance is exacerbated by the current toxic political discourse and demoralizing regressive social policymaking, coupled with the excitement of heightened grassroots social movement resistance. For me, the salient question is — how can we provide students not only with the critical thinking skills to de-construct the contradictions before them, but to invite them to bring their whole selves, such that they can be more resilient, and ultimately be personally and collectively empowered to effect change?

In order to face the challenges of the 21st century, we must invite our students into an opportunity to change the existing paradigm and to co-produce real solutions. The challenges we face are indeed daunting – the human fallout of hypercapitalism, racism and xenophobia, privatization of public services, environmental devastation, digital age stress, and health disparities. It is our job as educators to tap into human strengths, including our capacities for presence, intuition, empathy, critical analysis, and persistent action, in ways that have the potential to transform individuals, communities, and systems. This means that educators must craft experiential learning opportunities that help students understand and reflect on their own relationships to these issues and all of their complexity, in addition to imagining and embodying new solutions in the classroom and field. It is clear that social work practice and education in the 21st century demand new innovations, actions, and risk-taking.

We can draw inspiration from a global movement of educators who believe these transformational processes can be nurtured in the classroom through deliberate cultivation of deeper levels of mindfulness, discourse, and human connection. This necessitates participation of the whole self in relation to other whole selves in the context of the environments we inhabit. Such processes and practices require the creation of trusting, compassionate relationships within the classroom community so that students feel safe enough to get uncomfortable. These processes are necessarily visceral as we help students to cultivate a connection with a felt sense of the body-mind-spirit across differences. By engaging holistically in the classroom, student social workers can take their new insights and skills into the community.

Educators need supportive communities of their own to learn from, be motivated by, and to lean on.

This transformative work asks us to be in an ongoing critical conversation with the current social work and educational environment, particularly the impacts of globalization, the commodification of social services and social work education, diversity and growing awareness of non-western cultural and healing practices, as well as the causes and consequences of maladaptive coping. To sustain this conversation in the classroom and the community, we need skills for nurturing our relationships and ourselves. Based on my experiences working with social workers and activists both in the community and in the classroom, I believe we need to develop a sustainable and integrative capability to be responsive in real time, inviting learning and growth throughout one’s career. Such a capability can be cultivated by teaching mindfulness, conscious communication, self-care, and empathy across differences.

In my collaborative work with educators from around the world, I’ve met inspiring social workers who are drawing from the works of Paulo Freire and Augusto Boal, and employing modalities such as theater of the oppressed, mindfulness, t’ai chi, and integrative mind-body-spirit social work to move students toward greater self-awareness, wellbeing, and group empowerment. These educators are also addressing the institutional barriers they have faced in implementing such pedagogies in institutions that are arguably set up to perpetuate patriarchy, positivism, and disembodied “diagnose and treat” interventions.

Our students are hungry for authentic and radical human connection, as they learn to hold complexity en route to effective change making. To be able to do this work, educators need supportive communities of their own to learn from, be motivated by, and to lean on. We can do this by convening skill shares, reflective communities of practice, and conferences like BPD, poising social work educators to revolutionize social work education and to actualize our shared visions for social justice.

Come and visit Oxford University Press at BPD at booth 206!

Featured image credit: full frame shot of stadium by johnyksslr. Public domain via Pexels.

The post Transformative social work education: the time is now appeared first on OUPblog.

In praise of teaching with Skype

For the past six or seven years I’ve been giving music lessons online, using Skype or FaceTime (Apple’s proprietary alternative to Skype). My students include children, college students, adult amateurs, and concert artists. Some of them take occasional lessons, others hew to the traditional once-a-week lesson schedule. I’ve had face-to-face encounters with some of them, but not all of them.

Here are some of my recent students:

A young singer in Israel who has taken regular lessons over a year and a half.

Another young singer based in Melbourne who has taken dozens of Skype lessons, in addition to a large number of face-to-face lessons when she lived in Paris (where I make my home).

A professional cellist who I’ve known for fifteen years, currently living in Minnesota.

A flutist, also from Minnesota, preparing an audition for a big-time opera theater.

A professionally trained violist who makes a living as a doctor in Connecticut.

A professional flutist in Kentucky.

A college student in upstate New York, studying the double-bass.

A jazz pianist in Nashville.

A child-prodigy singer, violinist, pianist, and composer, currently living in New York City.

The online medium creates its own pedagogical possibilities, which flow logically from the medium’s constraints. How to place yourself when you’re trying to demonstrate something at the piano or the double-bass? If you give a full-view of your posture, you’ll be relatively far from the screen and the mike, possibly rendering dialogue difficult. Re-arranging positions in the middle of the lesson can be bothersome. These constraints might drive you crazy…or “drive you smart,” to coin an expression. Generally speaking, constraints are beneficial to your creativity. As Nadia Boulanger liked saying, “Great art likes chains.” Rather than fighting or resenting the constraints, embrace them and exercise your creativity to work within them.

Internet connections can be unreliable. You might be interrupted, often and unpredictably. Some of my lessons over Skype had so many interruptions that the subject matter of the lesson became “how to deal with interruptions”—that is, how to deal with distractions, challenges, difficulties, and disagreeable moments. It’s an endlessly valuable life lesson, potentially allowing you to develop intellectual and musical continuity in a discontinuous situation. As with other constraints, it helps if instead of resenting the interruptions you embrace them.

Music and music-making seem to be at the core of a music lesson, and sound and sound-making at the core of music. If so, online lessons aren’t ideal, since what your student plays or sings is inevitably filtered and distorted before it reaches your ears. But I think music and sound are comparatively secondary, even in a music lesson. I believe what is primary is the overall individuality of both the teacher and the student, manifested in perception and intention, habit and preconception, discourse and reaction, thought and gesture. This means that some music lessons might not even entail music-making at all, but a constructive dialogue that helps both the teacher and the student clarify their ends and means.

A music lesson might involve discussing rehearsal strategies, practice habits, music history, theory, analysis, ear-training, and many other activities for which a very precise dimension of sound making and listening isn’t essential. At any rate, online technology allows for a degree of sonic appreciation and discernment. You can tell that two interpretations are different—flowing or blocked, structured or improvised, alert or distracted, shout-y or whisper-y—even if you can’t pinpoint issues of timbre, dynamics, harmonics and partials, and so on.

Sonically, Skype is obviously a filter. The sounds I hear at home are definitely not like the sounds that the musician is making across the continents. But this, too, is a plus. First, it encourages both teacher and student to become better aware of the filtering process, which happens nonstop anyway and quite independently of technology. Your personality, aesthetics, habits, likes, and dislikes are also a sonic filter, predetermining some of your reactions when you hear a musician playing or singing right in front of you.

Second, it encourages the listener to acknowledge some uncertainty. “I don’t know exactly how you’re singing or playing. But from where I’m sitting here, it seems to me that…” Ultimately, this shifts the responsibility of listening closely and making aesthetic choices to the student. In the long term, it’s the best possible outcome.

Online lessons challenge a teacher to think in new and different ways. Skype is a kind of mirror: it lets you know what are your pedagogical strengths and weaknesses. Then it’s up to you to find new ways of observing, talking, listening, demonstrating, and so on.

Why would you take a music lesson from a disembodied teacher who’s sitting at a computer a continent away from you, rather than a talented and devoted individual whom you can meet in your own neighborhood? I can think of three reasons.

First, the relationship between a teacher and a student is by no means banal. Like all human beings, both the teacher and the student have unique, complex needs and wants. There must be some sort of match between the teacher and the students. For some of my students, I’m the absolute best teacher in the whole world; what I have to offer corresponds to what they need. But some people have taken a single lesson from me, never to return; I consider it obvious that what I had to offer didn’t correspond to what they needed. There doesn’t exist “a good teacher” or “a good student,” but only a good match between a teacher and a student. You might have to travel far in order to find your match. Skype is a very cost-effective travel mechanism!

Second, the very nature of a disembodied teacher can be a plus. The physical distance may be helpful, reassuring, or comfortable, depending on the student and the teacher. Face-to-face interactions have potential drawbacks. Back in my youth, for instance, one of my teachers was a chain smoker who kept his teaching room’s windows permanently closed. To take lessons with him was to smoke with him. It was a manageable difficulty, but a difficulty nevertheless.

Finally, people have always communicated in multiple ways, using a variety of media from smoke signals to telegrams to megaphones. Talking to a computer screen that talks back to you is just another way to communicate, a tool with its merits and demerits. Young people take computers for granted, but for some of us the existence of Skype is fantastically exciting, like something from science fiction, the unimaginable made concrete. It’s a wonderful toy to play with.

Featured image: “46/365 My Computer Floats” by Mike Poresky. CC by 2.0 via Flickr.

The post In praise of teaching with Skype appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers