Oxford University Press's Blog, page 395

March 8, 2017

Ernestine Rose and the Women’s March

If she were alive today, Ernestine Rose, a 19th century radical, would have participated in the 21 January 2017 Women’s March. The mass protest spawned sister rallies around the globe and drew more than a million participants who brandished signs proclaiming desires for equal rights, not just for women, but for all people. These tenets were integral to Rose’s life, and she fought for them throughout her life.

In the 1850s, Ernestine Rose was one of the most famous women in the United States—far better known than her co-workers, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. An outstanding orator in an era when women seldom spoke publicly, she had an international as well as a national reputation. “Her eloquence is irresistible,” a British socialist wrote, “It shakes, it awes, it thrills, it melts—it fills you with horror, it drowns you with tears.” In the early US women’s movement, audiences cried out for her when bored. “I was infinitely relieved when Mrs Ernestine L. Rose took the floor,” a female journalist wrote in 1860. She continued:

A good delivery, a forcible voice, the most uncommon good sense, a delightful terseness of style, and a rare talent for humor are the qualifications which so well fit this lady for a public speaker. In about two minutes she managed to infect her two-thousand-fold audience with a spirit of interest—an audience which mere dry morals and reason had succeeded in reducing to a comatose state.

Ernestine Rose in a pink pussy hat. Used with permission from the Jewish Book Council.

Ernestine Rose in a pink pussy hat. Used with permission from the Jewish Book Council.Rose believed in fighting for her beliefs. “‘Agitate! agitate!’ Ought to be the motto of every reformer,” she proclaimed. “Agitation is the opposite of stagnation—the one is life, the other death.” She supported three main causes: women’s rights, antislavery, and free thought. All were unpopular in her day. She faced angry mobs, hostile threats, and insulting put-downs. “We know of no object more deserving of contempt, loathing, and abhorrence than a female atheist,” a clergyman wrote about her before she gave an antislavery speech in Portland, Maine. “We hold the vilest strumpet from the stews to be by comparison respectable.” But nothing stopped her. From her arrival in New York City in 1836, she worked for women’s equal rights, carrying a petition around lower Manhattan so wives could possess their own property (the law then held that everything a wife earned or owned belonged to her husband). Within a few months, she began debating with other freethinkers at Tammany Hall. By the 1840s, she lectured against slavery, first in South Carolina. A member of her audience threatened to give her “a coat of tar and feathers” and a friend later wrote that “it required considerable influence to get her safely out of the city.”

Her efforts for women’s rights, free thought, and abolition are all the more remarkable because she had traveled so far to become an American radical. She was born the only child of a Polish rabbi. She lost her faith in her early teens, so to “bind her more closely to the bosom of the synagogue,” her father betrothed her against her will. The marriage contract held that if she did not go through with the wedding, her fiancé would receive the inheritance left her by her mother. At 17, the girl went by sleigh to a Polish court, pleaded her own case, and won. She then left her family, Poland, and Judaism forever. Living in Berlin and then Paris, she spent five years in London, where she became a follower of the radical industrialist Robert Owen and met her husband, the silversmith William Rose. They moved to New York and lived there until 1869, when they returned to London. Until illness overcame her in her early 70s, she agitated for her beliefs. The only one she lived to see enacted was the abolition of slavery.

In many ways, her values were the opposite of Donald Trump’s. Always called a “foreigner,” she believed in the rights of immigrants like herself. She consistently held that all people, “black and white, men and women,” were equal and so should have equal rights. “White men are a minority in this country,” she declared. “White women, black men and black women compose the large majority.” Trump and his father refused to rent to blacks into the 1970s. Rose defended prostitutes as victims of male desire; Trump justified men’s sexual attacks on women. Rose argued that all people, “the Christian, the Mahomatan, the Jew, the Deist and the Atheist” can “reform the laws so as to have perfect freedom of conscience.” Trump’s campaign denigrated Muslims, Mexicans, immigrants, and the disabled.

Rose never ceased “agitating” for her beliefs. So I am sure that if she were alive today, she would have marched. Her example inspires us to both remember her legacy and follow it, to battle together for our rights and the rights of others. It is the only way we can reform the world.

Featured image credit: DC Women’s March by Liz Lemon. Public Domain via Flickr.

The post Ernestine Rose and the Women’s March appeared first on OUPblog.

March 7, 2017

What not to expect when you’re expecting

Writing in 1990 about her experience attending antenatal classes in the 1950s, British mother and childbirth activist Heda Borton recalled her husband squirming as he watched a film of a baby being born in their antenatal education class: “My husband came to the evening under protest, and sat blowing his nose and hiding behind his handkerchief.” In 2009, American artist Jessica Clements described what she hoped to get out of watching a film in her childbirth preparation course: “I could not envision giving birth. The idea of my vagina stretching wide enough for an infant’s head seemed impossible and horrific.”

Across thousands of miles and nearly six decades, these two mothers had something in common. Like millions of other expectant parents across Western Europe and North America, they watched a live birth on film to prepare for their own upcoming experience.

Birth films became a ubiquitous and indispensable component of prenatal classes, a veritable rite of passage to parenthood. They helped to teach women and their partners what to expect when expecting, but also what was expected of them—how they should comport themselves in labour and birth. These images and the narratives that accompanied them became a lens through which parents could make sense and meaning of their own journey into parenthood.

In the late 1940s and 1950s, many middle-class white women, especially in the United States, sought alleviation of labour pain using “twilight sleep”—a combination of the amnesic scopolamine and morphine. Through a haze of semi-consciousness, they thrashed about and wailed as they suffered through incompletely managed pain and confusion.

Childbirth education classes and the films used as teaching tools in them gained prominence as women sought a greater satisfaction and “dignity” in birth. With their husbands by their sides, they wanted to be “awake and aware.” They turned to various approaches to so-called natural childbirth to manage pain without resort to drugs. These techniques differed in detail but shared a belief that prenatal preparation was essential for women to experience labour free from fear and better equipped to cope.

Produced in the 1950s and 1960s to support preparation in natural childbirth, the first generation of childbirth films reflected women’s desires to give birth with quiet calm. Typical of this era, the 24-minute, black-and-white film The Psychoprophylactic Method of Painless Childbirth (c. early 1960s) lays out the historical roots of what is popularly known as the Lamaze method, explains how it works, and provides advice on diet and exercise in pregnancy.

To highlight the drama and significance of the live birth sequence, the film switches to colour. The woman bears down and is clearly making an effort, but does not seem strained by it. Suggestive of an active, engaged role in her own birth experience, the mother reaches between her legs as the baby is emerging and practically catches her herself. Despite his marginalisation in the final moment, the obstetrician had been front and centre throughout the birth, offering exuberant and constant direction. There is no doubt that he was in charge.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, the tone of childbirth preparation films began to change with the times. The rise of second wave feminism and the mainstreaming of countercultural values transformed what women sought in childbirth. The goal of dignity in birth gave way to the aspiration for an empowering and deeply embodied experience, even as the (usually male) obstetrician retained authority and control. The popular and critically acclaimed The Story of Eric (1971) follows the birth experience of Wendy and Rich Johnson, a hip, mellow California couple. Working together “as a team” with her doctor, Wendy insists that, aided by her Lamaze training, “the pregnant woman feels more of an assistant to her doctor than a patient.” For certain the labouring woman was no passive recipient of the doctor’s aid, but nor is she in the lead.

Beginning in the 1980s and continuing today, natural childbirth’s popularity waned as women embraced epidural anaesthesia, which offered the chance to be both physically comfortable and fully conscious, something twilight sleep had not provided. Natural childbirth advocates continue to plead their case and win adherents. Natural childbirth might take more effort than birth with epidural anaesthesia, its partisans argue, but the psychological and physical reward to the mother, the couple, and the baby are ample. Tantalising claims of orgasmic birth add to natural childbirth’s continuing allure.

The films that women and their partners watched not only reflected changing aspiration but conditioned their expectations and became a yardstick against which they judged their experiences. On a 1985 television broadcast, one UK mother drew a straight line between the birth film she saw in her antenatal preparation class and her own disappointing experience. “I thought, ‘Right. This is for me.’” But then “there I was waiting for this sexual experience. I mean this orgasmic experience. If that’s an orgasm, god help us!”

Irrespective of when they were made, childbirth films over the last sixty years rarely align with women’s first-hand experiences. Whether touting dignity, empowerment, or something still more elusive, the historical record suggests that claim that these films prepare women for childbirth certainly merits skepticism.

Featured Image Credit: Havering Branch: antenatal class photograph by NCT/Wellcome Library, London. Public domain via Flickr.

The post What not to expect when you’re expecting appeared first on OUPblog.

Anglo-Saxon law, social networks, and terrorism

How would the Anglo-Saxons react to the threat of terrorism if they had access to Facebook? It’s a bizarre question, I admit, but I’ve been immersed in England’s pre-Norman Conquest legal system for over a decade now, and it’s been playing on my mind. The answer makes me uncomfortable.

Supposing the brutal persecution of minority groups was impractical (which it actually wasn’t), how would the Anglo-Saxons have reacted if they knew that there were among their number people who secretly rejected their core values and plotted to cause them harm? What would they have done if, even though the authorities thought they knew who some of these threatening individuals were, it was impossible to convict them on any charge without actually catching them in the act of wrongdoing?

The Anglo-Saxon ruling elite wrestled with essentially this problem across the tenth century. The public enemy that worried them was the thief. Men who openly seized others’ property weren’t thieves. Thieves were cowards who hid their responsibility; they were liars, willing to perjure themselves to avoid detection, and their anonymity meant they could be anyone at all. Unsolved thefts could sow suspicion among friends and neighbours, damaging the very fabric of community. Thieves were a menace to society; they provoked a legislative fervour bordering on obsession.

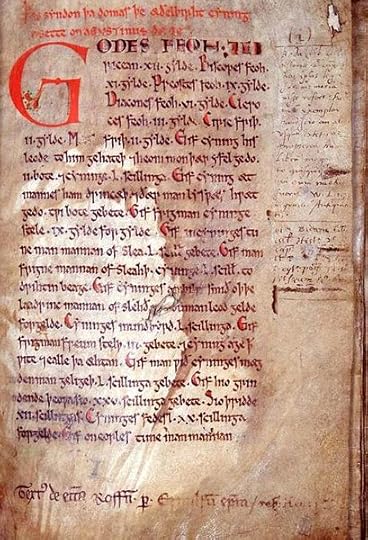

Opening page of the 7th century Law of Æthelberht, by Ernulf bishop of Rochester. Courtesy of Rochester Cathedral Library. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Opening page of the 7th century Law of Æthelberht, by Ernulf bishop of Rochester. Courtesy of Rochester Cathedral Library. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.So why not just round up suspected thieves and hang them? This is the approach most people today would expect of medieval justice, but for Anglo-Saxon legislators this was unthinkable. The legally free had inviolable civil liberties. Unless he had been caught in the act, a free man with no record of dishonesty had the right to deny any charge by swearing that he was innocent. Providing he was able to persuade a number of other free people (11 may have been conventional) to swear that his oath was “clean and unperjured,” that was it: he was proven innocent. The willingness of thieves and their families to take advantage of this entitlement, brazenly perjuring themselves, infuriated some kings, but they never openly undermined it.

Rather, they made ingenious efforts to get around it. Their most far-reaching reform involved suretyship. Free Anglo-Saxons had always been expected to have sureties: locally based guarantors for any financial liabilities they might leave behind if they suddenly disappeared. Under King Edgar (957–75), however, suretyship rules changed dramatically. Henceforth every free man was to have sureties who were financially responsible not only for any damage he did (as was traditional) but also for any punishments he incurred. If a thief fled, his sureties would now not only have to recompense his victim, but pay a very large fine. Men who could persuade nobody to stand surety for them were untrustworthy by definition; they faced execution.

The underlying idea was to make use of social networks—to tap into people’s knowledge of one another’s characters. Upstanding, economically rational men would only stand surety for people they trusted; they would judge the risk of backing more dubious characters to be too high. If personal or familial loyalties in practice trumped assessments of financial risk, then so be it: groups which knowingly shielded wicked individuals deserved the ruinous fines this system would heap on them.

In practice, the system appears not to have worked well. By the early thirteenth century, when we can see it in operation, it seems people weren’t actually making choices based on trust, but were essentially forced to act as sureties for their neighbors. Perhaps this was inevitable. Networks of personal trust may simply have been too complex and fluid to be effectively integrated into medieval legal machinery.

We, though, live in the age of social media. Imagine for a moment: a new law demands that every citizen find ten other citizens willing to accept liability for a £50,000 fine if he or she commits mass murder. The government provides an online system in which you register your suretyship obligations; you can log on and make changes at any time but if you are without a full set of sureties for too long you face penalties of some sort—perhaps you have to pay to be fitted with an electronic tag. The security services monitor the system closely, hoping to detect terror cells from unusual patterns in suretyship networks.

It’s the plausibility of this scenario I find unsettling. Yes, it’s a dystopian vision of state intrusion, of a legal order which denies civil liberties to the socially isolated. But if such a system generated data that actually prevented atrocities, how much weight would our societies place on the rights of a small minority—a minority not defined in ethnic or religious terms?

Now that we have the technology to do so in complex and populous societies, will we choose once again to embed law in social networks? I fear we may, and that the moral world of early medieval law is rather less distant and alien than we might smugly assume.

Featured image credit: Replica of the helmet from the Sutton Hoo ship burial. Photo by IH (40), CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Anglo-Saxon law, social networks, and terrorism appeared first on OUPblog.

Reducing risk of suicide in cancer patients

Cancer patients experience substantial psychological effects from facing death, financial issues, emotional problems with friends and family, and adverse medical outcomes from treatment. The psychological effects are so severe that some patients consider suicide.

Depression is more common in people with cancer than in the general population, said Kelly Trevino, PhD, from the Center for Research on End-of-Life Care at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York. “The prevalence of depression in this population runs between 12% and 17%, compared to approximately 7% in the general population.”

The risk of suicide also is higher among cancer patients: twice that of the general population. That higher rate is troubling for health professionals. In an effort to intervene earlier, researchers are developing a list of risk factors for depression among cancer patients. Among cancer patients, factors such as a family or personal history of depression or suicidal tendencies, drug or alcohol abuse, the recent death of someone close, and having few friends or social supports are common. Moreover, several risk factors are related to the disease itself.

People with breast, lung, head and neck, and stomach cancers have higher levels of depression than those who suffer from other cancers, probably because those cancers (or their treatments) are disfiguring and more aggressive and deadly.

“I think differences in presentation of depression are related to symptoms being the result of many different pathways,” said Kevin Patterson, MD, director of psycho-oncology at the University of Pittsburgh. “One possibility relates to the neurovegetative symptoms that constitute physical depression. These are exhibited by low energy and low motivation as well as sleep and appetite changes.”

He noted that some cancers and cancer treatments result in low energy or motivation independent of mood symptoms. Often when your body is depressed physically for a long time, that depression can become mood-based as well.

Researchers also are looking into whether chemical pathways in cancer may have a role. Certain chemicals, especially the cytokines, span the immune, endocrine, and nervous systems. The chemicals can affect all domains.

“The prevalence of depression in this population runs between 12% and 17%, compared to approximately 7% in the general population.”

“The likelihood that there exists a chemical pathway able to depress the nervous system is very high,” Patterson said. Although several studies support that supposition, “nothing has been shown to be the singular explanation—probably because you are seeing various combinations of these and other pathways.”

Over the last five years or so, the already extensive research into that area has intensified. One of the drivers is the distress-related screening and treatment protocols required for Cancer Center certification from the American College of Surgeons’ Commission on Cancer.

To address some of those issues, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) published an adapted guideline for screening, assessing, and caring for anxiety and depression in adults with cancer. In the Journal of Clinical Oncology, ASCO suggested evaluating symptom presence throughout the time of care by using validated scales and procedures.

ASCO recommends that doctors use the Personal Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) for screening purposes. That nine-question instrument is used to screen, diagnose, monitor, and measure the severity of depression. The first two questions are used for screening and ask about a patient’s level of interest or pleasure in doing things and whether the patient is feeling down, depressed, or hopeless. If the answer to either question is yes, ASCO recommends that patients fill out the rest of the questionnaire. The final questions of the PHQ-9 concern the length and severity of symptoms and are used in diagnosis and monitoring. Those questions ask about symptoms of depression such as sleep disturbances, eating habits, and concentration problems. One question assesses the possibility of suicidal thoughts or actions.

The guidelines suggest periodic screening throughout cancer treatment. Researchers agree that increased vigilance is important at specific times, such as within the first two or three visits and at transition points such as those outlined earlier.

“I don’t know that we have any good data on how often to screen,” said Dale Theobald, MD, PhD, who has been senior medical director for palliative, hospice, and home health care at Community Health Network in Indianapolis. “Certainly you don’t want to pester a patient with big checklists at every appointment. [But] I think an important part of any office visit is asking about how they are feeling, their energy level, and their current mood.”

The results of those questions could then be used to guide the provider’s decision on whether to follow up with a more structured and formal evaluation. And although completing screening tools is important, other considerations depend on the instincts of the provider.

“Most practitioners get to know their patients, and if they think there is an additional risk of depression or suicide they should pay special attention,” Massie said. “Clinicians contact me all the time asking me if I can see their patient sooner rather than later. Something just doesn’t feel right and they are worried.”

Although large facilities may have adequate staff to help, those concerns are worse at the community level where most patients are treated. Addressing that gap would require the large centers and their smaller counterparts to work together.

“When we studied oncologists’ ability to recognize depression in their patients, we realized it is hard to distinguish depressive symptoms from other cancer treatment and cancer disease–related symptoms—such as fatigue,” Theobald said. “We realized the importance of using valid screening processes to make treatment of depression in cancer patients more effective. In later trials we documented that careful use of standard antidepressants is an effective way to treat this common illness.”

“Overall there is great hope,” Theobald said. “Depression associated with cancer can be treated effectively.”

A version of this blog post first appeared in Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Featured image credit: CAT scan May 2015 by liz west. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Reducing risk of suicide in cancer patients appeared first on OUPblog.

International Women’s Day: a reading list

To celebrate International Women’s Day, we’ve put together a reading list of biographies that capture the lives of influential women throughout history. If you have any reading suggestions for International Women’s Day, please share in the comments below.

The Invention of Angela Carter: A Biography by Edmund Gordon

The Invention of Angela Carter: A Biography by Edmund Gordon

Structured in succinct, briskly moving chapters that make the biography read like an absorbing novel, The Invention of Angela Carter offers the first full account of Carter’s amazing life and enduring work through previously untold anecdotes of her youth, marriages, professional struggles, and her painful battle with cancer.

The Rabbi’s Atheist Daughter: Ernestine Rose, International Feminist Pioneer by Bonnie S. Anderson

Written by a senior scholar of women’s history, The Rabbi’s Atheist Daughter recovers Ernestine Rose’s career as a feminist, freethinker, and abolitionist to the pantheon of 19th century history, and looks at the role of an atheist during Christian reform movements.

Women in the World of Frederick Douglass by Leigh Fought

A readable biographical study of the life of the great abolitionist, Women in the World of Frederick Douglass highlights Douglass’s complicated relationships with family and a range of female activists, friends, admirers, and adversaries. Fought fleshes out female figures in Douglass’s life—including his grandmother Betsey, mother Harriet, wives Anna Murray and Helen Pitts—despite there being few records in their own words.

Jane Crow: The Life of Pauli Murray by Rosalind Rosenberg

Jane Crow: The Life of Pauli Murray by Rosalind Rosenberg

A definitive biography of a key figure in the civil rights and women’s movements, Jane Crow explores the life of Pauli Murray, a black person who identified at birth as female and believed she was male—all before the term “transgender” existed.

Just Another Southern Town: Mary Church Terrell and the Struggle for Racial Justice in the Nation’s Capital by Joan Quigley

In this book on District of Columbia v. John R. Thompson Co., Inc., a landmark case in the earliest days of the civil rights movement, author Joan Quigley brings attention to the indomitable Mary Church Terrell, a frequently overlooked civil rights figure. After being refused service at a DC restaurant due to her race, Terrell, a former suffragette and one of the country’s first college-educated African American women, took the matter to court.

Restless Ambition: Grace Hartigan, Painter by Cathy Curtis

By drawing on the Hartigan’s emotionally revealing journal and candid interviews, author Cathy Curtis traces the artist’s rise from virtually self-taught painter to art-world. Restless Ambition, the first biography of Grace Hartigan, places her in context of other Abstract Expressionists, including Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline, and Helen Frankenthaler.

Marie von Clausewitz: The Woman Behind the Making of On War by Vanya Eftimova Bellinger

In this biography of Marie von Clausewitz, author Vanya Eftimova Bellinger offers the first comprehensive and compelling look at the woman behind the composition of On War. Bellinger discusses the social and cultural climate of Clausewitz’s time, and includes her analysis on newly discovered correspondence that sheds light on Clausewitz’s influence over her husband’s work.

The Book of Margery Kempe by Margery Kempe, translated by Anthony Bale

The Book of Margery Kempe by Margery Kempe, translated by Anthony Bale

Known as the earliest autobiography written in the English language, Kempe’s Book describes the dramatic transformation of its heroine from failed businesswoman and lustful young wife, to devout and chaste pilgrim. The introduction by Bale discusses Kempe and her status as a woman writer and proto-feminist, the historical context, medieval pilgrimage and travel, audience and reception.

American Women’s History: A Very Short Introduction by Susan Ware

This offers concise introduction to American women’s history emphasizes the diversity of American women’s experiences. Drawing on her four decades of experience researching and teaching, author Susan Ware discusses the factors that have shaped American women throughout history, including race, class, religion, geographical location, age, and sexual orientation

Featured image credit: Untitled by Lia Leslie. CCO via Pexels.

The post International Women’s Day: a reading list appeared first on OUPblog.

Getting to know Antonina in music marketing

Our Cary office has welcomed a new assistant. Antonina Javier joined the marketing team in November 2016 after moving to North Carolina from Hawaii. We sat down with her to talk about publishing, books, and the outdoors. She is always ready for an adventure and is eager to share what she has seen.

When did you start working at OUP?

I started in November of 2016.

What’s the most surprising thing you’ve found about working at OUP?

When I started working here, I didn’t realize how interconnected the organization is. I thought I’d only be interacting with colleagues in Cary. However, on a daily basis I’m speaking with people from all over the globe.

What’s the least surprising?

There is always something to read. I’m a huge fan of reading our blog posts, but there are endless amounts of interesting books and journals to flip through as well.

What is your typical day like at OUP?

As a marketing assistant, I get to be involved with various activities. I don’t think I’ve established a typical routine yet. I’m still fairly new and am experiencing a wide range of programs and practices. So far, the only consistent thing I do is learn, which is really exciting.

What’s the most enjoyable part of your day?

It’s kind of silly, but at the end of the day I enjoy crossing off items on my to-do list. It’s extremely satisfying.

What was your first job in publishing?

I worked for my school newspaper in college. I was a features writer and columnist.

What’s your favourite book?

Travels with Charlie by John Steinbeck. It’s the book that inspired me to take a cross-country road trip. I also love Steinbeck’s writing style. It’s humorous, approachable, but also has depth.

If you didn’t work in publishing, what would you be doing?

I’d be an adventure photographer. I spend a lot of my free time outdoors and taking photos.

What’s the first thing you do when you get to work in the morning?

Make a cup of tea and dig into my emails.

Antonina Javier

Antonina JavierWho inspires you most in the publishing industry and why?

Alpinist Magazine. The magazine is made up of amazing storytellers who expertly combine writing, art, and adventure. I hold it in such high regard because every piece motivates me to take my own adventures and create my own life story.

How would you sum your job up in three words?

Multifaceted, challenging, and fulfilling.

What are the biggest changes you’ve seen in the publishing industry since working at OUP?

Technology is something that is always on our minds. Right now our team focuses a lot on how we can move away from print and utilize different ways to reach users.

What is in your desk drawer?

My desk drawer serves as my in-office pantry. I have various teas and a collection of snacks.

What is your most obscure talent or hobby?

My main hobby is rock climbing and through that I’ve learned how to tie over 30 different knots.

What is your favorite animal?

Bison. I love how deeply rooted they are to North America’s land, culture, and history. They are beautiful creatures.

Featured image: Yosemite Valley by Lubomir Mihalik. CC0 via Pixabay

The post Getting to know Antonina in music marketing appeared first on OUPblog.

My life as a police officer: a Q&A

Ahead of tomorrow’s International Women’s Day, we asked a female police officer about her experience of working in a police force in the UK. She talks about her motivations for joining the police, some of the challenges facing officers today, and shares some advice for aspiring officers.

What attracted you to a career in the police?

I’ve always been interested in the police. When I was applying for 6th form, I remember being asked what I wanted to do for a career and I said that I’d like to join the police, but I wanted to complete my A-Levels in order to give me other career opportunities. When I finished my A-Levels the police force had a five year recruitment ban still in place so I went to university, but a year after I finished studying, the police force was recruiting, so as it had always been a dream of mine, I applied. After a year long process, I was successful.

Is there anything that surprised you about the job?

It is largely how I expected it to be, although I did expect more physical paperwork, but we have work tablets so everything’s online, saving time and resources, and reducing the need to copy the same information onto several pieces of paper.

When I joined I was surprised at some of the jobs we get called to as response officers, even members of the public can be confused as to why we are there sometimes, but it is part of the job and each call is important in its own way. One of the things that surprised me most when I first started was that a verbal argument between family members or partners is recorded. Many would probably consider an argument as something fairly minor, often not needing police attendance, however if police have been called, it will be recorded.

I was also pleasantly surprised at how well all the emergency services work together as a team when it’s needed.

Can you tell us a bit about what you might do in a ‘typical day’?

When I first started, a typical shift pattern would be either five days working and three days off, or four days working and two days off, with no real pattern to the hours, but we’ve moved to working four days on and four days off with 2 splits on each of the teams. I find this pattern a lot better, you always know when you’re working, and it’s more sociable so you get to see more of your friends and family.

No two days are the same but you do get patterns in day and night shifts. It’s quite common for a Road Traffic Collision to come in during the morning rush hour, likewise it’s common that a missing person will come in during the evening shift, but obviously this isn’t always the case.

What would be your top tips for an aspiring police officer?

I think the most important thing is for people to do their research and have a long hard think if it’s right for them. This job requires a lot of dedication, you can’t just leave at the end of the shift because you’re timetabled to go home if you are in the middle of a job, and it can at times be very antisocial. If you put the effort in, ask for help when you need it, and always strive to do your best, people can’t ask for more.

I believe you have to really want to do this as a career because at the end of the day, police officers deal with things that members of the public couldn’t imagine. You see things first hand that other people certainly wouldn’t see on a day to day basis, and it can at times be taxing on your emotions. Also you have to deal with a lot of people who don’t like the police and you have to spend a lot of time with those people to try and show them that you want to help them and try to break down the barriers that might be there.

Feeling that you know you have helped someone is so satisfying and drives you during your next job.

What are the best things about your job?

Feeling that you know you have helped someone is so satisfying and drives you during your next job. I love working with people, even if they don’t want me there, and I love going into work and knowing what the day has in store for me.

What do you think are some of the major challenges being faced in policing today?

I think one of the major issues faced by police today is public perception. Mistakes have been made in the past and as a result of that, many members of the public have lost faith in the police. I think we should strive to rebuild that trust and I sincerely hope that in the future there will be less of a divide. I believe first impressions last for a lifetime, so I treat everyone with respect and do my utmost to help them in what ever way I can.

Another important issue I’ve learned about recently is to do with domestic violence. Studies have shown that many individuals undergo several incidents of domestic violence before calling the police. It’s such a tragedy that this happens, people should feel that they can call the police whenever they need to, that they’ll be treated with respect, and that the officers who attend will be pro-active. I know a lot of forces in England have made this their priority and I hope that in the near future people will contact the police straight away.

Can you describe your job in three words?

Rewarding/Hard/Unpredictable (but in a good way!)

Are there any women who inspire you?

The one person I look up to and can always count on is my mum. Like many other women in this world she has been a single mum trying to bring up 3 children. I think she has done a remarkable job, she is so strong and I know I can always count on her no matter what, no matter when. If I can be half of the person she is, I will be very happy indeed.

Featured image credit: Officers on patrol by West Midlands Police. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post My life as a police officer: a Q&A appeared first on OUPblog.

March 6, 2017

The right way to amend the Johnson Amendment

President Trump, reiterating the position he took during the presidential campaign, has reaffirmed his pledge to “get rid of and totally destroy the Johnson Amendment.”

The Johnson Amendment is the portion of Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code which prohibits tax-exempt institutions from participating in political campaigns. Reflecting the President’s perspective, Representative Walter B. Jones, Jr. of North Carolina has introduced legislation to repeal the Johnson Amendment in its entirety.

Rather than the blanket repeal of the Johnson Amendment proposed by President Trump and Representative Jones, I argue for a more limited statutory safe harbor for the internal communications of churches. Under such a modification of the Johnson Amendment, churches, along with other religious and secular tax-exempt institutions, would otherwise remain subject to the Code’s bar on campaigning.

First Amendment considerations counsel greater protection than current law provides for speech within churches. However, Section 501(c)(3)’s bar on political campaigning by eleemosynary institutions properly deters the diversion of income tax-deductible resources to political campaigns. A more targeted reform of the Johnson Amendment limited to internal church communications addresses the legitimate concerns of churches about their First Amendment rights, while preventing the tax-exempt sector from becoming a conduit for tax-deductible campaign contributions.

Critics of the status quo occupy their strongest ground when they seek to protect internal discussions within congregations. In troubling fashion, current law entangles church and state, as the Code now requires the IRS to monitor and evaluate discussions within congregations to ascertain if those discussions constitute as campaigning. This entanglement is deeply problematic from a First Amendment perspective. Had the Johnson ban on campaigning been aggressively enforced in the past, American life would have been diminished. Such causes as abolitionism and civil rights were deeply anchored in America’s churches.

Rev. Rul. 2007-41 is the IRS’s current administrative interpretation of the Johnson Amendment. Under that ruling, a church’s “issue advocacy” can constitute “campaign intervention” and thus cost the church its tax-exempt status under Section 501(c)(3) of the Code. Whether such issue advocacy is permitted is a fact-based determination with all of the uncertainties that it implies. Among the relevant considerations identified by the IRS is whether the issue being addressed by the 501(c)(3) entity “is a prominent issue in a campaign that distinguishes the candidates.” Under this fact-based standard, a minister’s sermon could jeopardize her church’s tax-exempt status if, on the Sunday before an election, the minister supports or opposes abortion rights, same-sex marriage, gun control, the death penalty, or the Confederate flag should the IRS determine this subject to be “a prominent issue” in a current electoral campaign.

This entangles the IRS and churches in a troubling fashion and thus raises legitimate First Amendment concerns about the internal autonomy of churches.

However, the proponents of the Johnson Amendment score points when they raise the prospect of tax-deductible resource diversion. Without some restraints, nonprofit entities tax-exempt under Code Section 501(c)(3) could become conduits for funneling income tax deductible resources into political campaigns. This is an outcome no one should favor.

Since the compelling problem is untoward government intrusion into churches’ internal communications, the solution should be targeted to the protection of such church communications. Congress need not repeal the Johnson Amendment in its entirety. Tax-exempt organizations should generally be barred from political campaigning. Congress should adopt a more limited statutory safe harbor for internal church communications. Amending the Johnson amendment in this narrower fashion is the appropriate solution which better balances churches’ legitimate First Amendment concerns about their internal communications with the need to prevent the diversion of tax-deductible resources to political campaigns.

Featured image credit: church boston usa america by strecosa. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The right way to amend the Johnson Amendment appeared first on OUPblog.

Eating fruits and vegetables can make you more attractive

Carotenoids are yellow, orange, and red pigments synthesized by plants and algae. They are responsible for the colours in fruits and vegetables, like the redness in tomatoes. When consumed, these pigments are used by many animals to produce brightly coloured displays. Examples range from the orange patches on guppies, the pink feathers of flamingos, the yellow-orange underside of common lizards, to the orange exterior of ladybird beetles.

In many species, carotenoid colouration is used by females to select their mating partners. Early studies on guppies for example, showed that females preferred to mate with males with bright carotenoid colouration. Similar results have since been found in other fishes and various birds and reptiles.

James’s Flamingo mating ritual

James’s Flamingo mating ritual by Pedros Szekely. CC by 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Wild male and female guppies

Wild male and female guppies by Per Harald Olsen. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Coccinella transversalis, elytra in the open position

Transverse Ladybird (Coccinella transversalis), Austins Ferry, Tasmania, Australia by JJ Harrison. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Evolutionary theories suggest that carotenoid colouration is attractive because it signals good health. Besides influencing colour, carotenoids are thought to support health as antioxidants. Carotenoids cannot be synthesized in the body, and can only be obtained through carotenoid rich foods. Healthier individuals require less carotenoids to support health. Therefore, they can devote more carotenoids to colouration, thus signalling their superior health. However, the hypothesis that carotenoids support health has received mixed support in animal studies. While some studies found that carotenoids reduce oxidative stress, enhance immune function, and increase male reproductive function, others have found null results.

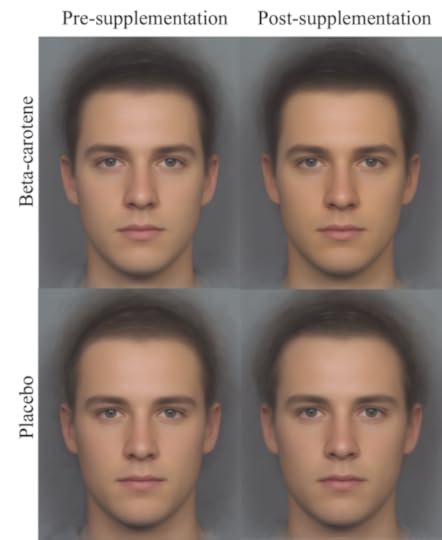

Average pre- and post-supplementation faces of individuals in each treatment group illustrating the facial colour changes in response to beta-carotene supplementation. Photo by Y. Z. Foo. Used with permission

Average pre- and post-supplementation faces of individuals in each treatment group illustrating the facial colour changes in response to beta-carotene supplementation. Photo by Y. Z. Foo. Used with permissionRecent studies suggest that carotenoid colouration may also function as an attractive signal of health in humans. It has been shown that individuals prefer faces that are yellower and redder. To examine the causal effect of carotenoids on facial appearance and health in humans, we conducted an experimental dietary supplementation study. Men were given a 12-week dose of either the carotenoid beta-carotene or placebo. We took photographs of each man’s face before and after supplementation. Skin colour was measured from the photographs. A separate group of women was then asked to select the more attractive face out of the before and after photos for each man. We also took a number of health measures, including oxidative stress, immune function, and semen quality prior to, and after the 12-week study.

So did beta-carotene positively affect the health and appearance of the men in the study? Our results support the idea that carotenoid colouration affects human attractiveness. Beta-carotene consumption enhanced the yellowness and redness in the men’s faces and when women were asked to rate faces for attractiveness they found those of carotene supplemented men more attractive.

While beta-carotene seemed to have made the men look more attractive, it did not have an effect on three measures of health; immune function, oxidative stress, and semen quality. The null health findings suggest that carotenoid colour might not be a signal of health in humans. However, it is worth noting that the male participants in the study were all relatively healthy and young individuals. Therefore, it is possible that they did not need additional carotenoids to support their health and were able to use all of the supplemented beta-carotene to enhance skin colour. Also, our study focused only on one specific carotenoid: beta-carotene. It is possible that beta-carotene affects health only when it is coupled with other nutrients.

Overall, our results suggest that a healthy diet of carotenoid rich fruit and veggies can improve our attractiveness by enhancing our skin colour. But how much fruits and veggies do we have to eat? A previous study by Whitehead and colleagues using psychophysical methods to determine the minimum amount of fruits-and-vegetables associated colour change required to make our skin look more attractive estimated that we would need to eat three extra portions of fruits and veggies a day. In short, time to start eating your fruits and veggies.

Featured image credit: Fruits Vegetables by Domokus. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Eating fruits and vegetables can make you more attractive appeared first on OUPblog.

Reality check: the dangers of confirmation bias

A professional hazard that nearly all experts must learn to overcome is “confirmation bias,” the tendency to favor and recall information that confirms their hypothesis.

In this excerpt from The Death of Expertise, Tom Nichols discusses a 2014 study on public attitudes towards gay marriage to illustrate the dangers of confirmation bias.

“Confirmation bias” is the most common—and easily the most irritating—obstacle to productive conversation, and not just between experts and laypeople. The term refers to the tendency to look for information that only confirms what we believe, to accept facts that only strengthen our preferred explanations, and to dismiss data that challenge what we already accept as truth. We all do it, and you can be certain that you and I and everyone who’s ever had an argument with anyone about anything has infuriated someone else with it.

Scientists and researchers tussle with confirmation bias all the time as a professional hazard. They, too, have to make assumptions in order to set up experiments or explain puzzles, which in turn means they’re already bringing some baggage to their projects. They have to make guesses and use intuition, just like the rest of us, since it would waste a lot of time for every research program to begin from the assumption that no one knows anything and nothing ever happened before today. “Doing before knowing” is a common problem in setting up any kind of careful investigation: after all, how do we know what we’re looking for if we haven’t found it yet?

Even though every researcher is told that “a negative result is still a result,” no one really wants to discover that their initial assumptions went up in smoke.

Researchers learn to recognize this dilemma early in their training, and they don’t always succeed in defeating it. Confirmation bias can lead even the most experienced experts astray. Doctors, for example, will sometimes get attached to a diagnosis and then look for evidence of the symptoms they suspect already exist in a patient while ignoring markers of another disease or injury.

Even though every researcher is told that “a negative result is still a result,” no one really wants to discover that their initial assumptions went up in smoke.

This is how, for example, a 2014 study of public attitudes about gay marriage went terribly wrong. A graduate student claimed he’d found statistically unassailable proof that if opponents of gay marriage talked about the issue with someone who was actually gay, they were likelier to change their minds. His findings were endorsed by a senior faculty member at Columbia University who had signed on as a coauthor of the study. It was a remarkable finding that basically amounted to proof that reasonable people can actually be talked out of homophobia.

The only problem was that the ambitious young researcher had falsified the data. The discussions he claimed he was analyzing never took place. When others outside the study reviewed it and raised alarms, the Columbia professor pulled the article.

Why didn’t the faculty and reviewers who should have been keeping tabs on the student find the fraud right at the start? Because of confirmation bias. As the journalist Maria Konnikova later reported in The New Yorker, the student’s supervisor admitted that he wanted to believe in its findings. He and other scholars wanted the results to be true, and so they were less likely to question the methods that produced their preferred answer. “In short, confirmation bias—which is especially powerful when we think about social issues—may have made the study’s shakiness easier to overlook,” Konnikova wrote in a review of the whole business. Indeed, it was “enthusiasm about the study that led to its exposure,” because other scholars, hoping to build on the results, found the fraud only when they delved into the details of research they thought had already reached the conclusion they preferred.

This is why scientists, when possible, run experiments over and over and then submit their results to other people in a process called “peer review.” This process—when it works—calls upon an expert’s colleagues (his or her peers) to act as well-intentioned but rigorous devil’s advocates. This usually takes place in a “double- blind” process, meaning that the researcher and the referees are not identified to each other, the better to prevent personal or institutional biases from influencing the review.

This is an invaluable process. Even the most honest and self-aware scholar or researcher needs a reality check from someone less personally invested in the outcome of a project.

Featured image credit: Untitled by Pixabay. CC0 via Pexels.

The post Reality check: the dangers of confirmation bias appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers