Oxford University Press's Blog, page 393

March 12, 2017

Perfection, positivity, and social media [excerpt]

Facebook can often be described as a “24/7 news cycle of who’s cool, who’s not.” This image highlights a major change in how young people analyze their social statuses: although previous generations certainly compared themselves to their peers, they didn’t have a digital system in place to capture exactly where they fell in the social rankings. In this shortened excerpt from The Happiness Effect, Donna Freitas analyzes the emphasis that university students place on “likes” when determining their level of social media success.

We don’t need social media to compare ourselves to other people or to worry about others’ responses to what we say or do. Engaging in status competitions is nothing new. It’s common, especially when we’re young (though adults are certainly not exempt). We compare our looks, our hairstyles, our opportunities, our friends, our successes and failures, where we’ve traveled (or haven’t), where we’ve gone to school, where we’re from, our clothes, and all sorts of material objects. The list goes on and on. We seek approval and affirmation all the time.

The difference with social media is that it seems expressly designed for this purpose of showing off, for bragging and boasting of all that one is, has, and does, as well as for others to judge these things. Facebook is the CNN of envy, a kind of 24/7 news cycle of who’s cool, who’s not, who’s up, and who’s down. In the process of showing off our successes and proving how happy we are, we are exposing ourselves to others’ highlight reels, too, and to the possibility of rejection. Unless you have rock- solid self- esteem, are impervious to jealousy, or have an extraordinarily rational capacity to remind yourself exactly what everyone is doing when they post their glories on social media, it’s difficult not to care.

The title of the actress and comedian Mindy Kaling’s first memoir, Is Everybody Hanging Out Without Me? (And Other Concerns), not only reflects her trademark humor, but it aptly captures this common pain, so much so that I borrowed it for this chapter. There is even a special acronym to capture the phenomenon of so much comparing ourselves to others today: FOMO (Fear of Missing Out), a kind of suffering that comes from witnessing the amazing times other people are having without you, and perhaps have intentionally not invited you to join. Some of us are really good at protecting ourselves from such comparisons, or at least being ambivalent about them, but many of us are vulnerable to this particular suffering, and social media exacerbates and escalates it to levels that most of us have never before experienced, nor have the emotional resources to withstand— at least not so consistently and constantly.

Photo by Priscilla Yu for Oxford University Press.

Photo by Priscilla Yu for Oxford University Press.There are benefits to this, though. All those “likes” and “retweets” and “shares” can make us feel like mini-celebrities, at least for a moment.

Before social media, we may have sat in a classroom admiring someone’s stylish outfit, or wishing we had a cute boyfriend, too, or that we had gotten to go to that fun party on Friday night. But there was only so much we could see and hear about. With social media, people can log on again and again, stare and envy and obsess as long as they like, and not only know that someone has a cute boyfriend but peruse all the gorgeous pictures of him, not only hear there was a party on Friday but see the hundreds of photos of people having a blast without them.

In the online survey, students were asked to respond either “yes,” “no,” or “not applicable” to a series of statements about how they feel/ are/ act/ what they do when they go onto social media. One of those statements was “I find myself comparing myself to others a lot.” Of the students who responded, 55% said yes and 43% said no (2% answered not applicable). Well over half do this type of comparing regularly, but when it came to responding to the statement “It’s important that others see me as having a good time,” only 35% of these same respondents said yes, and a whopping 60% answered no…

Only fifty students (16%) claimed that they’d never compared themselves to others or felt left out. Even those who said “I used to do it, but not anymore” talked about how they “got themselves over” this tendency, as though they’d healed themselves of a terrible habit, a kind of sickness that comes with social media. Some students suffer far worse than others. When students talk about feeling inferior on social media—even if only rarely or in their past—they discuss it as if it is an affliction, one that comes with the territory. And a number of students commented on how comparing oneself to others and having feelings of being left out are simply human tendencies that have been heightened to an unhealthy degree by social media.

As much as so many students try not to succumb, the phenomenon of comparing oneself to others— and the feelings of missing out that come with this behavior—seems to be one of the most common experiences of being on social media. Getting “likes” (and “retweets” and “shares”) is a central part of the performance of perfection and positivity. Not only does it prove that you “are,” as Rob might put it, but it also is a quantifiable mark of success and affirmation (part and parcel of that “popularity principle” that Van Dijck talks about)—it confirms that you are performing your social media duties well. On the flip side, the inability to obtain quantifiable public approval is a source of shame. It shows everyone not only that you are irrelevant, but also that you are performing poorly in the endeavor to showcase only your best efforts, your greatest successes, your most attractive traits, both physical and personal—that even when you are making your best effort, you still can’t measure up to the competition.

Featured image credit: Image by Tookapic. CC0 Public Domain via Pexels.

The post Perfection, positivity, and social media [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

The polls aren’t skewed, media coverage is

The perceived failures of election forecasting in 2016 have caused many to suggest the polls are broken. However, scholars are quick to point out that more than polling failure this election has demonstrated that people have a hard time thinking probabilistically about election outcomes. Our research suggests skewed media coverage of polls may also be to blame: News media are likely to cover the most newsworthy polls, distorting viewers’ perception of the race.

Game of Polls

News outlets are incentivized to cover polls because they are newsworthy. Poll coverage – much like stories on the horse race – are timely, novel, and conflict-ridden, meeting standards of newsworthiness. Viewers prefer the more exciting results, polls that show a close race or a candidate’s unexpected surge. Polls that show a consistent race, on the other hand, are less likely to get air time. The consequences of this cherry-picking is reflected in the nightly news, where coverage that emphasizes more exciting poll results may bias perceptions of candidate standings.

This selection process, or gatekeeping, affects the news we see and thus, represents a sort of media bias that can be difficult to study. This is in part because the only way to study this process is by examining the stories which make it past the proverbial chopping block, such as coverage of the 2008 US presidential election between Obama and McCain.

We collected data on primetime television poll coverage on major television networks (ABC, CBS, NBC, CNN, Fox News, and MSMBC) during the last five months of the 2008 presidential campaign, which suggested that media coverage reflects a different version of the race than actual polls.

When comparing the polls that made it to the air versus all polling data that was available for coverage, our findings show that news coverage reported on closer polls.

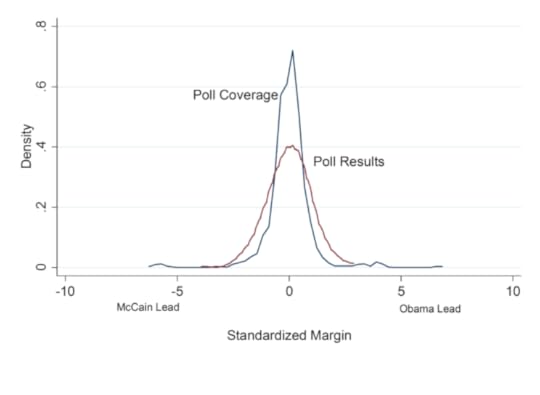

The graph below converts the reported margins between Obama and McCain in the 2008 US presidential election to standard-deviation units. The red line shows actual poll margins, and the blue line shows the poll margins covered on the news. At first glance, the two distributions are different, suggesting that media coverage of polls reflect a different version of the race than actual polls. Specifically, the actual poll distribution is more normally distributed whereas the coverage of polls distribution has a more dramatic spike clustered between -1 and +1. This suggests that news coverage reported on closer polls.

Comparing Poll Results to Poll Coverage in the 2008 Presidential Campaign by Kathleen Searles, Martha Humphries Ginn, and Jonathan Nickens. Used with permission.

Comparing Poll Results to Poll Coverage in the 2008 Presidential Campaign by Kathleen Searles, Martha Humphries Ginn, and Jonathan Nickens. Used with permission.More drama, more attention

Not only does media poll coverage vary from reality, but the coverage is not even accurately capturing the polls selected. In the 2008 election, polls suggested that Obama consistently held the lead over McCain.

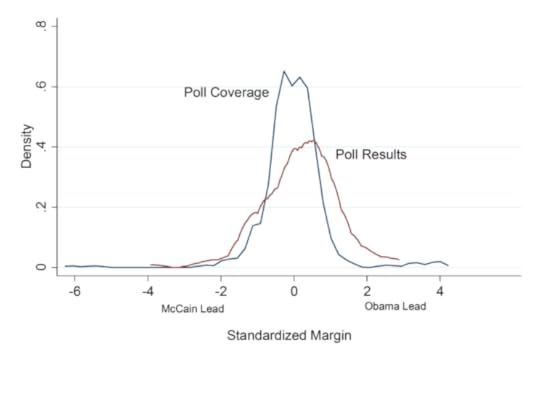

In the graph below, the red line reflects the reported polls and shows that Obama consistently held the lead. The blue line shows which of these polls got the most air time. On average, viewers were more likely to hear about a close race than about the polls that showed Obama in the lead.

Distribution of Standardized Margins for Matched Polls and Poll Coverage by Kathleen Searles, Martha Humphries Ginn, and Jonathan Nickens. Used with permission.

Distribution of Standardized Margins for Matched Polls and Poll Coverage by Kathleen Searles, Martha Humphries Ginn, and Jonathan Nickens. Used with permission.When we look at the characteristics of the polls that do air on television, we find that changes in poll margins (as measured using a moving average of the last four margins) predict the total number of times a poll aired. In other words, significant changes in poll margins make it more likely that a poll will air.

For whom the poll airs

While much discussion following the 2016 Presidential Election has focused on the “broken” public opinion polling industry, there is a need for a discussion about how to properly cover polls. It may be helpful if news outlets were to decide upon a set of standards for how polls are covered, including qualifications for covering in-house polls versus outside poll firms, and share these standards with the public so as to make at least some of these processes less cloaked.

As the marketing value of polls has become more obvious, routines and norms of the newsroom are likely to be influenced. We suggest that a way to make sure these changes are positive is to reinvigorate discussion on better reporting of polls and increase the transparency of poll selection.

Our two pieces of advice: consider the source, and be wary of poll coverage.

Featured image credit: Politics & Pizza: Watching the U.S. Midterm Election Results by US Embassy Canada. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post The polls aren’t skewed, media coverage is appeared first on OUPblog.

[image error]

George Eliot and second lives

The Victorian novelist Margaret Oliphant knew she was second-rate in comparison, “No one even will mention me in the same breath with George Eliot. And that is just.” But, she added, “It is a little justification to myself to think how much better off she was – no trouble in her life as far as appears…” Mrs Oliphant was left, aged 30, a widow with 3 children, £1000 in debt, and a hard-pressed living to make out of her writing. In comparison, she thought, George Eliot lived luxuriously in “a mental greenhouse” protected by her bohemian common-law husband, George Henry Lewes, “a caretaker and a worshipper.” She did not have to try to live any more: in her second life, on becoming a writer at 37 in 1856, she could simply write, with all the unearned gifts of a genius.

It was only half true. True that Marian Evans who became George Eliot suffered no great tragedy. But what she did suffer disproportionately was the inability to live well: over-intelligent, over-emotional, this young woman who felt herself ugly and ego-bound, was humiliated by clumsy attempts to find adult love, unable to replace her first family with anything like a second, or her religious background with a secure secular equivalent. “What shall I be without my Father?” she wrote at his death in 1849, even after their quarrels, “It will seem as if a part of my moral nature were gone. I had a horrid vision of myself last night becoming earthly sensual and devilish…” She had begun a series of rather desperately clumsy love-affairs with older teachers, married men, intellectuals, and female-substitutes. For years she seemed messily unable to put together any number of desired two-somes: intellect and emotion, life and work, psychology and morality, the conflict of needs between sexual love and conscience. Mrs Oliphant was right: the woman who became George Eliot could not live as an ordinary woman; but then Mrs Oliphant was also wrong: George Eliot used not being able to live for the sake of those “experiments in life” she called her novels. As she was to write of herself as Maggie Tulliver: “The great problem of the shifting relation between passion and duty is clear to no man who is capable of apprehending it…We have no master-key that will fit all cases”

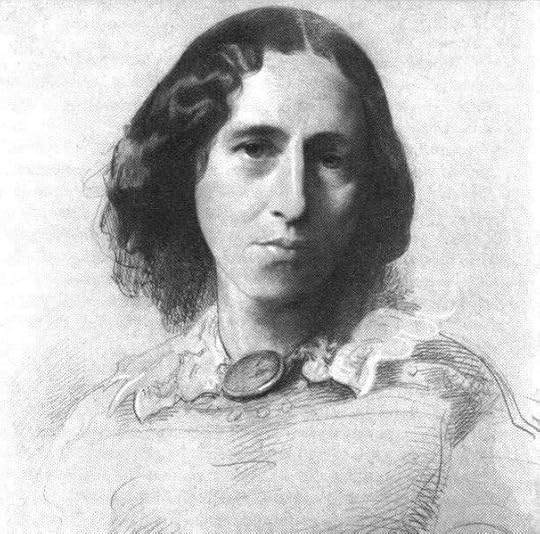

Image credit: George Eliot at 30 by François D’Albert Durade. Public domain by Wikimedia Commons

Image credit: George Eliot at 30 by François D’Albert Durade. Public domain by Wikimedia CommonsAll people of broad, strong sense have an instinctive repugnance to the men of maxims; because such people early discern that the mysterious complexity of our life is not to be embraced by maxims, and that to lace ourselves up in formulas of that sort is to repress all the divine promptings and inspirations that spring from growing insight and sympathy. And the man of maxims is the popular representative of the minds that are guided in their moral judgment solely by general rules, thinking that these will lead them to justice by a ready-made patent method, without the trouble of exerting patience, discrimination, impartiality,– without any care to assure themselves whether they have the insight that comes from a hardly earned estimate of temptation, or from a life vivid and intense enough to have created a wide fellow-feeling with all that is human.

(The Mill on the Floss, book 7 chapter 2)

What she could not solve in her first life went into her second life as a realist novelist. There the realist novel became a creative holding ground for the human predicament of those who, without ready-made maxims, systems and formulas, knew that everything depended upon an intensely individual working out of the relation of the general and the particular. Hence the complication of George Eliot’s long, serious sentences in the struggle for integration, to try to hold together two-or-more competing and conflicting thoughts in one mentally syntactic relationship. That is still the deep use of the psychological novel which George Eliot re-founded, especially for those who did not know how to live in the first place; who needed what William James said religion had once stood for in the history of human feeling: “help! help! The first condition of human goodness is something to love.” (“Janet’s Repentance,” chapter 10).

Portrait of George Eliot by Samuel Laurence, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of George Eliot by Samuel Laurence, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.The later nineteenth century she represents is not an historical period we have simply left behind. What it stands for psychologically, again and again, for sundry lost individuals is the arena of transition from a religious to a modern secular life: an in-between world of seriousness that many people still do not, cannot or will not wholly get over. The Victorian critic John Morley said that reading George Eliot was like inadvertently entering a confessional. There, within her characters and in relation to them, she could see your secret thoughts and needs, your stupidity and your struggling value. In her books she upped the demand made upon human beings till it was almost like “hearing the grass grow and the squirrel’s heart beat” in an almost unbearable hyper-reality that was still ordinary life. Like her characters, her readers know what she called the terror of morality and yet the necessity of it, the fear of being judged and yet the need to be understood. It is not by being a woman of maxims but by her radical experiments in art, that “George Eliot” embodies what it means to work between fiction and life, to make books reach out of themselves even from within their very own midst.

Featured image credit: California Countryside Rural Farm Ranch Landscape by tpsdave. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post George Eliot and second lives appeared first on OUPblog.

Finding career success through authenticity

“Knowledge workers,” or people who think for a living, continue to be major players in the global economy. In today’s competitive job market, creating a successful career in a knowledge work field takes more than a college degree. One of the keys to success is authenticity: understanding yourself so that you can take charge of your own work.

We’ve gathered advice from An Intelligent Career: Taking Ownership of Your Work and Your Life for the following infographic on how knowledge workers can improve their careers by employing authenticity.

Download the infographic as a PDF or JPEG.

Fea tured image credit: Untitled by rawpixel.com. CC0 via Pexels.

The post Finding career success through authenticity appeared first on OUPblog.

March 11, 2017

Liar, liar, pants on fire: alternative facts

“Well, who you gonna believe, me or your own eyes?” [Chico Marx, as Groucho Marx’s character in Duck Soup.]

Truth is highly significant to our culture but sometimes it’s hard to pin down what exactly constitutes truth. Let’s start with the Oxford Dictionary’s definition:

1.1 That which is true or in accordance with fact or reality.

That hardly covers all cases. To clarify a bit, let’s put truth into a context by looking at the scientific method:

Observation – certain specific happenings of physical reality are sensed.

Hypothesis – a general idea of the nature of all such events is created.

Prediction – presuming the hypothesis to be true, some similar happening is forecasted.

Experiment – a test is conducted to see if the predicted outcome actually occurs.

The experimental result is then compared to the prediction.

The observation step deals directly with physical reality. Measurements of real occurrences are made by trained experimenters. If their results don’t agree with each other, the experiments must be repeated to resolve disagreements. The truth of observations is thus strongly supported by abundant data. This fits the Oxford definition of truth nicely.

[image error]Liar by Lena. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The hypothesis step is a different story. A hypothesis is formed by generalizing observational results inductively to apply to all similar cases. The hypothesis applies generally, and is expressed in the form of a theory, possibly stated as a mathematical equation. So, does the hypothesis satisfy the Oxford definition of truth? Nope. The definition implies that truth must be universal. The hypothesis has been arrived at by inductive logic, so it might not be universally true. For example, Newton’s Law of Gravitation has lots of experimental support, but does it apply everywhere in the universe, at all times in the past, and will it apply at all future times? Not necessarily. The truth contained in a scientific hypothesis is tentative.

The prediction step is derived deductively from the hypothesis, so it contains as much truth as the hypothesis.

Just as in the observation step, the experiment step provides physical evidence, which matches the Oxford “truth” definition. The experimental result is compared to the prediction. If reality doesn’t match prediction, the hypothesis is faulty and must be adjusted or changed totally. If they do match, the hypothesis is supported but not confirmed absolutely since a general hypothesis requires all cases to be tested.

This demonstrates the different forms of scientific truth. But there is still a lot more to the story.

A further definition from Oxford states that truth is:

1.2 A fact or belief that is accepted as true.

This needs a closer look. Science has facts, but there were no beliefs. Back to the dictionary.

Oxford lists several definitions of belief, but here is a paraphrase of their meanings: something one accepts as true or real; a firmly held opinion; a religious conviction; trust, faith, or confidence in something or someone. How do truths believed by individuals or groups compare with scientific truths? On the face of it, scientific observations and experiments are backed by physical evidence, repeated in many settings, by many independent observers around the world. Beliefs require no such evidence.

On the other hand, scientific hypotheses are tentative truths, and require experimental evidence for support. The provisional nature of hypotheses sometimes leads to the cry: “that’s only a theory.” True enough, but the quality and quantity of experimental support for the theory must be examined before judgment of its truth is rendered.

Pseudoscience may also fit into the belief portion of the Oxford “truth” definition, since ESP or astrology may be accepted as true. By contrast with science, however, pseudoscience often lacks general hypotheses and broad experimental support, so science’s truth seems preferable.

However, here’s yet another wrinkle. The Oxford definition also says that accepted facts are regarded to be true. Suppose two different observers see the same event but report different results. According to science, observations made by large numbers of trained people are preferred, but pseudosciences accept anecdotal reports made by untrained observers.

Another approach would be to accept different versions of the same fact as being both true. In early 2017, different estimates of crowd sizes at large events have been made by different viewers, leading to the concept of “alternative facts,” as if all observations are equally valid.

This confusing and potentially divisive state of affairs has led the Oxford Dictionary to award the Word of the Year for 2016 to “post-truth” – an adjective defined as “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.”

So, have we arrived at the philosophy of nihilism that says nothing in the world has any real existence? Or are we closer to Rabbi Shimon bar Yohai, a Palestinian rabbi from the second century CE, who taught: “[There once was] the case of men on a ship, one of whom took a hand drill and began boring a hole beneath his own seat. His fellow travellers said to him: ‘What are you doing?’ Said he to them: ‘What does that matter to you, am I not boring under my own place?”

From the perspective that we all live on the same planet, perhaps we should take Chico Marx’s advice and examine the truth of everything, however challenging the critical thinking may become.

A trouser conflagration can indeed have devastating effects.

Featured image credit: Truth by GDJ. CC0 Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Liar, liar, pants on fire: alternative facts appeared first on OUPblog.

[image error]

The foundation of American liberalism [excerpt]

In 1912, a group of ambitious young men congregated in a 19th Street row house in Washington, DC. Disillusioned by the Taft administration, they shifted from a firm belief in progressivism—the belief that the government should protect its workers and regulate monopolies—into what is now called “liberalism,” or the belief that government can improve citizens’ lives without abridging their civil liberties and, eventually, civil rights.

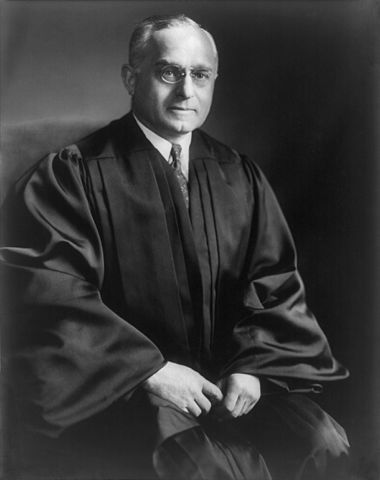

In this shortened excerpt from The House of Truth: A Washington Political Salon and the Foundations of American Liberalism, Brad Snyder explains how these friends, among whom included Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter and journalistic giant Walter Lippmann, laid the foundations of American liberalism.

In 1918, a small group of friends gathered for dinner at a row house near Washington’s Dupont Circle: a young lawyer named Felix Frankfurter; a 77-year-old Supreme Court justice, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr, and his wife, Fanny; and perhaps the most unlikely guest, the sculptor Gutzon Borglum. As they sat around the dining room table, Borglum described his latest idea for a sculpture. He wanted, he explained to the other guests, to carve monumentally large images of Confederate war heroes into the side of Stone Mountain, Georgia. Justice Holmes, a Union army veteran who had always admired his Confederate foes, expressed interest in Borglum’s idea. Yet he could not fully grasp the sculptor’s vision.

Portrait of Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter of the United States Supreme Court, circa 12 July 1918. Author: Harris & Ewing. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter of the United States Supreme Court, circa 12 July 1918. Author: Harris & Ewing. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Borglum, a Westerner whose cowboy hat, bushy mustache, and stocky frame reflected his frontier beginnings, pushed the plates to the center of the table and began drawing on the white tablecloth. He depicted three men in the foreground, all of them on horseback: Robert E. Lee on his legendary horse, Traveller; Stonewall Jackson, slightly in front of Lee; and Jefferson Davis closely behind them. There were clusters of cavalrymen in the background. The desired effect, Borglum explained, was to march the Confederate army across the 800-by-1,500-foot face of the mountain. Holmes was delighted and astonished. Frankfurter never forgot the encounter.

As it turned out, Borglum never finished his Confederate memorial (mainly because of a dispute with the Ku Klux Klan, an organization he had embraced). Nonetheless, his first attempt at mountain carving led to what became the major work of his lifetime: memorializing four American presidents in the Black Hills of South Dakota at Mount Rushmore.

By the time Frankfurter, Holmes, and Borglum dined there that night, they had eaten many meals together at this narrow, three-story, red-brick row house that its residents self-mockingly but fondly referred to as the “House of Truth.” The name was inspired by debates between Holmes and its residents about the search for truth. During these discussions, Frankfurter and other Taft and Wilson administration officials who lived there from 1912 to 1919 turned the House into one of the city’s foremost political salons. They threw dinner parties, discussed political events of the day, and wooed young women and high government officials with equal fervor. Ambassadors, generals, journalists, artists, lawyers, Supreme Court justices, cabinet members, and even a future US president dined there. “How or why I can’t recapture,” Frankfurter recalled, “but almost everybody who was interesting in Washington sooner or later passed through that house.”

For Frankfurter and his friends, the House was a place to gather information, to influence policy, and to try out new ideas. In 1912, many of them wanted Theodore Roosevelt once again in the White House and supported his third-party presidential run. Two years later, they founded the New Republic as an outlet for their political point of view. Above all, the House of Truth helped them created an influential network of American liberals.

Portrait of journalist Walter Lippmann by the photographer Pirie MacDonald, published in 1914. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of journalist Walter Lippmann by the photographer Pirie MacDonald, published in 1914. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Before the First World War, one institution had stood in the way of their political goals—the Supreme Court. The Court struck down state minimum wage and maximum hour laws, limited the enforcement of antitrust laws and the rights of organized labor, and curbed congressional power. Part of the attraction of Theodore Roosevelt for the House of Truth crowd was his willingness to put “the fear of God into judges.”

After the 1919 Red Scare prosecution and deportation of radical immigrants and the Red Summer of racial violence, Frankfurter and his allies began to change their view of the Court. They looked to the Court, and especially to Holmes and Louis D. Brandeis, to protect free speech and fair criminal trials. During the Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover administrations of the 1920s and early 1930s, Frankfurter, Lippmann, and their liberal friends found themselves out of political power. They never lost faith in the democratic political process, but they turned to the judiciary when the political process failed them.

The story of the House begins with the friendship and professional aspirations of its three original residents: Frankfurter, Winfred T. Denison, and Robert G. Valentine. Together with Frankfurter, they stood out in the Taft administration as three of the most fervent supporters of Theodore Roosevelt. Though Denison and Valentine have been forgotten by history, all three men played central roles in the formation of the House of Truth.

The House broke up as a political salon in 1919 after its residents fell out of political power. Yet their faith in government and their old friendships never waned. In the years to come, they argued about which presidential candidates to support in the New Republic. They lobbied for and against Introduction

Supreme Court nominees. They took sides in 1927 on the efforts to save Italian anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti from the electric chair. They repeatedly celebrated the career milestones and opinions of Justice Holmes. And in 1932, they helped to elect a president and another Roosevelt.

In its own way, nothing captured the House of Truth’s belief in government better than Borglum and his monument at Mount Rushmore, a mountain carving inspired by the Confederate memorial he had started to draw on the tablecloth that night in 1918. His desire to create a “shrine to democracy” began after Theodore Roosevelt’s defeat in 1912. That election galvanized Borglum, just as it did the group of young men, beginning with an Austrian-Jewish immigrant who ascended through the ranks of the federal government of his adopted country.

Featured image credit: “Supreme Court of the United States” by Daderot. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The foundation of American liberalism [excerpt] appeared first on OUPblog.

Aleppo: the key to conflict resolution in the Syrian civil war?

The international community started having a different view of the ongoing tragedy in the Syrian civil war after a 7-year-old girl, Bana Alabed, who used to live in Aleppo, started posting messages, asking for help, from a twitter account beginning September 2016. Whether these messages were authentic or not, they provided renewed insights into the conflict and paved the way for a change in the existing stalemate in Aleppo and Syrian civil war in general. Finally, just a couple months ahead of the sixth year’s end in the conflict, an agreement has been reached in Astana, Kazakhstan on 24 January, 2016 by the participation of the major domestic and international state and nonstate actors, who had stake in the conflict. Why is Aleppo significant? Why are there external states supporting various rebel groups? And, why did the conflict in Syria take so long to resolve?

Aleppo represents the complexity of the Syrian conflict. Two dimensions of this complexity are striking: (i) the multi-ethnic and multi-religious structure of the Syrian population and (ii) the intervention by outside actors and their conflicting interests. The major opposition to the Syrian government has included the pro-Kurdish groups and moderate Sunni Arabs. After the onset of conflict in March 2011, US, Western states, and Turkey stood by the side of the rebels, which they considered moderate Sunni opposition against the Alawite, but secular, authoritarian regime of Syria. Once the fighting spread to Aleppo in mid-2012, which was the largest city and financial and industrial center of Syria, it quickly turned into a stalemate between government and opposition groups. The Western part was controlled by pro-Assad (Syrian government) forces and the Eastern part of the city was controlled by rebel groups, mostly consisting of moderate Sunni Arabs. The stalemate continued till mid-2016, when Syrian government forces cut the supply routes to rebels in the Eastern part of the city.

The enduring conflict in Aleppo mostly stemmed from two factors related to both internalities and externalities of Syrian conflict. First, the opposing rebel groups were never able to unify against the Assad regime during the initial phase of rebellion and provide credible signals to the international community that they can replace the regime. Second, there were several outside interveners in the conflict both on the side of the rebels and the government. US and Turkey got involved from the beginning in training, arming, and funding the opposition, while Hezbollah, Iran, and Russia have interfered through diplomatic and military means on the side of the Syrian government. The existing research on external intervention in civil wars finds that the presence of outside interveners supporting different sides of a given conflict is a major factor prolonging civil wars rather than resolving them. The figure provides a picture of the actors involved in Syrian war in 2015.

Actors involved in Syrian War in 2015 by Belgin San-Akca. Used with permission.

Actors involved in Syrian War in 2015 by Belgin San-Akca. Used with permission.Regional balance of power

As the conflict endured, the number of external state and nonstate actors who intervened in Syria increased as well. Especially, the presence of US financial and military aid created a competition among the rebels and contributed to the fractionalization of the opposition. The rise of ISIS (Islamic State of Iraq and Syria) in early 2014 provided additional proof that the power vacuum in collapsing states, such as Syria, Afghanistan, and Somalia, are easily filled with extremist radical movements.

A turning point both in the stalemate over Aleppo and Syrian conflict in general was the intervention by Russia in September 2015. The US had already been complaining about the Sunni Arab opposition in Syria and its inability to present an alternative regime against Assad for a while at the time. The rise of ISIS made the US and Western alliance more suspicious of a policy designed to empower the Islamist-rooted groups. Russian intervention came at a point when the US was shifting policy from toppling Assad to fighting against ISIS. In order to achieve this, the US announced that it would continue supporting the pro-Kurdish groups, i.e. PYD (Democratic Union Party) and YPG (People’s Defense Units). Both of these groups are located under the umbrella of the Kurdistan Communities Union (KCK) with Kurdistan’s Workers’ Party (PKK). PKK is considered to be a terrorist organization by the US, the EU, and Turkey. Unable to convince the US officials about the organic links between PKK, PYD, and YPG, Turkey turned to Russia as a major change of policy in years since the conflict began. Of course, the developments at home contributed to this policy change. Both ISIS and PKK started attacks within the borders of Turkey in the mid-2015. By the summer of 2016, Turkish authorities were convinced that the fight against terrorism should be taken to the strongholds of these groups within the borders of Syria.

Turkey’s policy change played a significant role in starting communication between the Assad regime and the opposition. It is not only that Turkey is unwilling to border a Northern Syria, which might turn into a hotbed of terrorism populated by PKK-PYD-YPG militants, but also it does not want to fight a new wave of terrorism by a religious-rooted fundamentalist group like ISIS. The humanitarian crisis in Aleppo gave Turkey an opportunity to review its policy vis-à-vis its support of moderate opposition. By the same token, the Syrian conflict gave Russia an opportunity to balance against the US at least in the region, and Aleppo gave Russia an upper hand in terms of signaling to states, such as Turkey, a long-term NATO member, that Russia can be an equally trusted long-term ally like US, if not more.

Supporting rebels as a legitimate foreign policy strategy

Historical data between 1945 and 2010 shows that almost half of rebel groups, which seek to topple an existing leadership, manage to acquire an external state supporter and almost 70% of rebels, which fight for regime change, manage to receive external state supporters. From this historical perspective, the situation in Syria was not unique. Outside rivals of states, which go through internal turmoil, see an opportunity by the upsurge of rebellion in their rivals’ territories and start backing them to compel their rival to do something that they would not otherwise do. There are several specific aspects of the Syrian experience: (i) the number of not only state but also nonstate actors involved, (ii) external actors were equally motivated by ideational drives as much as material and strategic drives. The intervention by Hezbollah and Iran was ideationally driven to support Alawite-oriented Assad regime in comparison to Russian and US involvement, and (iii) it gave birth to a new legitimate foreign policy tool; supporting rebels on the ground to achieve specific objectives against the undesired governments. This was a long-standing instrument in the toolkit of states, yet frequently it was used covertly, rather than overtly as we have witnessed in recent years. It seems from the remarks of Theresa May that this policy is not there to stay for too long, either.

Featured image credit: Aleppo by watchsmart. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Aleppo: the key to conflict resolution in the Syrian civil war? appeared first on OUPblog.

March 10, 2017

The role of the death-mother in film

Hitchcock’s famous Psycho (1960) has an enduring legacy in the slasher-horror genre. Its impact on this genre is an enduring one, as suggested by the A&E series Bates Motel, culminating with Rihanna cast in Janet Leigh’s indelible role. Perhaps its most striking contribution, however, is its thematization of a figure I call the death-mother. This figure emerges from the diegetic world of the film, but exceeds it; she is born from abstraction, remoteness, distance. She emerges from the fusion of narrative concerns, embodied by the mysterious unseen persona of Mrs. Bates/Mother, and the heightened aesthetics of the genre artist.

Psycho expands on a work that anticipates some of its central themes of an overpowering female presence. Currently revisited in a revival of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s musical starring Glenn Close, Billy Wilder’s great 1950 film Sunset Boulevard charts the comeback of the fictional silent movie star Norma Desmond, played by the real silent movie star Gloria Swanson. Wilder’s movie, which he co-wrote with Charles Brackett, explores the tortured relationship between Norma, who verges on the brink of madness, and a down-on-his-luck screenwriter, Joe Gillis (William Holden), whom she hires to polish up her comeback vehicle (she has written a screenplay that defies logic).

Glenn Close as Norma Desmond in the current revival of the musical version of Sunset Boulevard. By Angelalitt CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Glenn Close as Norma Desmond in the current revival of the musical version of Sunset Boulevard. By Angelalitt CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The film famously begins with a shot of a man, who turns out to be Joe, floating dead in a swimming pool. He narrates the film in voice-over, in good film noir fashion, albeit from the dead. Joe floating in the pool: this shot returns the male subject, horrifyingly, to the womb and origins. Much of the film proceeds from this basis. Norma, in fierce, Kabuki-like make-up and dress that exaggerate her femininity and suggest a drag performance, alternately seduces and repels Joe.

There is an especially chilling, femme fatale moment in which Joe, comforting Norma after a suicide attempt, falls into her outstretched arms. Norma, a death’s-head smile on her face, enfolds Joe into her bosom, a fusion of the femme fatale and the mother of death. This moment anticipates the scene in which Norma literally kills Joe, shooting him and leaving him floating dead in her vast swimming pool, a grotesquely reabsorbed fetus.

What links Sunset Boulevard to Psycho are the associations of Norma and death and the level of aesthetic sublimity they achieve by the end of the film. Having fallen off the brink of sanity and become truly mad, Norma stands at the top of her decaying mansion’s long central staircase, believing, in her madness, that the television crews and the gossip columnist Hedda Hopper (playing herself), assembled at Norma’s home to document her arrest for murder, are all there to herald her triumphant comeback. “Max,” the cryptic, bald servant who looks after “Madame,” and is in actuality her former husband and film director (played by the real-life film director Erich von Stroheim), “directs” this scene of Norma descending the stairs.

As Norma descends the stairs, grandiose and melodramatic music (by Franz Waxman, who scored several Hitchcock films, most notably Rebecca, another film about an overpowering female presence) harrowingly ironizes Norma’s “big moment,” as she regally proceeds towards the cameras, gives a speech thanking all of those “wonderful people out there in the dark,” and says, to the director she once worked with and hopes will direct her comeback, “Mr. De Mille, I am ready for my close-up!”

Norma’s big moment. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Norma’s big moment. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.Two key aspects of the representation relate to the death-mother. As Norma, with antic, intensifying theatrical energy, makes her way down the stairs, the various reporters assembled, at different points, on the staircase stand stock still. This creates an exquisite tableau of life-in-deathness, which informs several Hitchcock films. It is as if Norma had entered the world of the dead, or re-entered the world while herself being dead, Hollywood as a carnival of souls.

Then, once Norma announces her readiness for her close-up, the music rises up again. As Norma, again with theatrical fervor, undulates toward the camera, something strange occurs. Or, to put it another way, an aesthetic choice is made. Her face does not come into greater definition (close-ups being crucial to this film, in which Norma says of her silent movie era, “We didn’t need voices then—we had faces.”) Rather, her image recedes into a misty, evanescent, smoky obscurity, and with it representation itself.

Both Wilder and Hitchcock find recourse in Surrealistic film technique, in which the film medium itself—the image itself—undergoes a profound distortion. The death-mother emerges from the concatenation of multiple effects—consistent motifs, associations, et al.—that then recombine in order to produce the effect, through an intense stylization and a series of concomitant aesthetic choices, that we have entered the world of death, one that is tinged with and indissociable from images and associations with the mother, grotesquely inverted as the mother who brings forth death, not life. Such occurs at the climax of Psycho, when the Mother’s skull-face is superimposed over Norman Bates’ face, and this image dissolves into one of a car being dragged out by a metal chain from a swamp.

Norman’s face fuses with Mother’s. Fair use via Blogspot.

Norman’s face fuses with Mother’s. Fair use via Blogspot.Psycho and Sunset Boulevard both reveal that a particular relationship exists between works that seek to thematize the terrors of gendered identity and sexual desire, specifically the relationship to the mother’s body and female sexuality, while also seeking an especially calibrated, considered aesthetic effect. The death-mother may suggest a great deal about the dread of the mother in culture and the misogynistic dimensions of this dread. Perhaps as resonantly, it reveals, as a fantasy but also an aesthetic preoccupation, that a profound and troubling linkage exists between the dread of a death-associated femininity and the zeal to create dazzling art.

Featured image credit: Norman Bates house from Pyscho. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The role of the death-mother in film appeared first on OUPblog.

To understand the evolution of the economy, track its DNA

How much would we understand about human evolution if we had never discovered genetics or DNA? How would we track the development of the human species without taking into account the universal code of life? Yes, we could study ancient trash heaps to estimate people’s average caloric intake over time. Or we might seek clues in burial mounds regarding population growth rates and changes in our physical characteristics over time. But without access to the fundamental unit of analysis of human evolution, our understanding would be fragmentary and incomplete at best.

Such is the plight of the social scientist seeking to understand the past, present, and likely future of the economy without an appreciation of code. Code is the DNA of economy. It is how ideas become things. The evolution of code is the story of the progress of human society from simplicity to complexity over the period of millennia. We can track GDP over time or measure employment rates. But without access to the fundamental unit of analysis of economic evolution, our understanding would be fragmentary and incomplete at best.

If you hear the word “code” you’re likely to think of computer code. That is one form. But consider the word code more broadly. The word “code” derives from the Latin codex, meaning “a system of laws.” Today code is used in various distinct contexts beyond computing—genetic code, cryptologic code (i.e., ciphers such as Morse code), ethical code, building code, and so forth—each of which has a common feature: it contains instructions that require a process in order to reach its intended end. Computer code requires the action of a compiler, energy, and (usually) inputs in order to become a useful program. Genetic code requires expression through the selective action of enzymes to produce proteins or RNA, ultimately producing a unique phenotype. Cryptologic code requires decryption in order to be converted into a usable message. Ethical codes, legal codes, and building codes all require processes of interpretation in order to be converted into action.

“The evolution of code is the story of the progress of human society from simplicity to complexity over the period of millennia.”

Code can include instructions we follow consciously and purposively, and those we follow unconsciously and intuitively. Code can be understood tacitly, it can be written, or it can be embedded in hardware. Code can be stored, transmitted, received, and modified. Code captures the algorithmic nature of instructions as well as their evolutionary character.

Code as I intend the word here incorporates elements of computer code, genetic code, cryptologic code, and other forms as well. But you will also see that it stands alone as its own concept—the instructions and algorithms that guide production in the economy—for which no adequate word yet exists. To convey the intuitive meaning of the concept I intend to communicate with the word “code,” as well as its breadth, I use two specific and carefully selected words interchangeably with code: recipe and technology.

The culinary recipe is not merely a metaphor for the how of production; the recipe is, rather, the most literal and direct example of code as I use the word. There has been code in production since the first time a human being prepared food. Indeed, if we restrict “production” to mean the preparation of food for consumption, we can start by imagining every single meal consumed by the roughly 100 billion people who have lived since we human beings cooked our first meal about 400,000 years ago: approximately four quadrillion prepared meals have been consumed throughout human history. Each of those meals was in fact (not in theory) associated with some method by which the meal was produced—which is to say, the code for producing that meal.

“Code can include instructions we follow consciously and purposively, and those we follow unconsciously and intuitively.”

For most of the first 400,000 years that humans prepared meals we were not a numerous species and the code we used to prepare meals was relatively rudimentary. Therefore, the early volumes of an imaginary “Global Compendium of All Recipes” dedicated to prehistory would be quite slim. However, in the past two millennia, and particularly in the past 200 years, both the size of the human population and the complexity of our culinary preparations have taken off. As a result, the size of the volumes in our “Global Compendium” would have grown exponentially.

Let’s now go beyond the preparation of meals to consider the code involved in every good or service we humans have ever produced, for our own use or for exchange, from the earliest obsidian spear point to the most recent smartphone. When I talk about the evolution of code, I am referring to the contents of the global compendium containing all of those production recipes. They are numerous.

This brings me to the second word I use interchangeably with code: technology. If we have technological gizmos in mind, then the leap from recipes to technology seems big. However, the leap seems smaller if we consider the Greek origin of the word “technology.” The first half derives from techné (τέχνη), which signifies “art, craft, or trade.” The second half derives from the word logos (λόγος), which signifies an “ordered account” or “reasoned discourse.” Thus technology literally means “an ordered account of art, craft, or trade”— in other words, broadly speaking, a recipe.

Substantial anthropological research suggests that culinary recipes were the earliest and among the most transformative technologies employed by humans. We have understood for some time that cooking accelerated human evolution by substantially increasing the nutrients absorbed in the stomach and small intestine. However, recent research suggests that human ancestors were using recipes to prepare food to dramatic effect as early as two million years ago—even before we learned to control fire and began cooking, which occurred about 400,000 years ago. Simply slicing meats and pounding tubers (such as yams), as was done by our earliest ancestors, turns out to yield digestive advantages that are comparable to those realized by cooking. Cooked or raw, increased nutrient intake enabled us to evolve smaller teeth and chewing muscles and even a smaller gut than our ancestors or primate cousins. These evolutionary adaptations in turn supported the development of humans’ larger, energy-hungry brain.

Featured image credit: Untitled by Pixabay. CC0 via Pexels.

The post To understand the evolution of the economy, track its DNA appeared first on OUPblog.

Reproductive rights and equality under challenge in the US

For the over 40 years since the US Supreme Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade that people have a constitutionally protected interest in deciding whether or not to reproduce, reproductive rights have been a persistent flashpoint of controversy in the United States. The controversy has been characterized by more heat than light, however. It features little attention to why pregnancies occur, how unwanted pregnancies might successfully be prevented, and what supports women’s need for healthy pregnancies and care for their children.

First there was the Hyde Amendment prohibiting the expenditure of federal Medicaid funds for abortions. The Amendment has been renewed every year since 1977, softened only to permit funding when the women’s life is endangered or the pregnancy resulted from rape or incest. The current Congress plans to make it “permanent” in the sense that it will continue without annual renewal. The Amendment’s reach now extends to health care coverage provided for federal employees, for people serving in the military and their families, for Native Americans and Alaskan Natives, and for inmates in federal prisons.

Then, there was the so-called “Mexico City” policy forbidding family planning services world-wide from furthering abortions in any way—even telling patients about the option—if they accept funding from the US government. According to a World Health Organization study, this policy may have had the perverse effect of actually increasing abortions, if family planning agencies forego US funding because they cannot make the required assurances—and thus have fewer resources available for pregnancy prevention. Critics claim that the study is based on flawed data, however. All Republican presidents since President Reagan in 1980 have ordered implementation of the policy; all Democratic presidents have rescinded it. One of President Trump’s first executive orders reinstated the policy but went far further: it now will apply to any health agency receiving US funding, including those providing HIV treatment.

Women’s March on Washington by Mobilus In Mobili. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Women’s March on Washington by Mobilus In Mobili. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Most recently, there’s been the Affordable Care Act’s inclusion of contraceptive coverage as a required essential health benefit. Churches and other religious institutions were exempted from the requirement on the basis of the constitutional protection of the free exercise of religion. This included religiously owned institutions such as schools and universities, hospitals, and nursing homes. The Supreme Court’s Hobby Lobby decision expanded this free exercise reasoning to cover closely held for-profit corporations whose owners had faith-based opposition to contraception. Anyone working for these employers who wishes contraceptive coverage will need to get it from a third party rather than their employer.

All along, the courts have been at the center of efforts to undo Roe v. Wade. Social conservatives have been galvanized to support or oppose potential nominees to the bench based on their likely views about reproductive rights. Neil Gorsuch, President Trump’s nominee for the US Supreme Court, voted in favor of exempting religious employers from the contraceptive mandate. In the Tenth Circuit’s decision in the Hobby Lobby case, he wrote that religious owners of for-profit businesses should be protected from what they regarded as complicity in an immoral act, that of providing their employees with insurance coverage for contraception. Judge Gorsuch has never ruled in an abortion case, so his views on that must be extrapolated from his other opinions and writings, including his well-known opposition to physician aid in dying.

If all of the other US Supreme Court justices remain on the bench and don’t change their views, it will take a second appointment to the Court to change the balance to opposition to Roe v. Wade itself. Just last term, the Court ruled 5-3 against Texas’s statutes requiring abortion clinics to be fully equipped as surgery centers and to have physicians with admitting privileges at hospitals within thirty miles. In this Whole Women’s Health decision, the majority reasoned that the restrictions placed a substantial burden on women’s reproductive rights but that Texas had no record evidence that the restrictions were needed to protect women’s health.

If the Trump administration and the current Congress have their way, however, state restrictions on abortion are likely to flourish and may ultimately prevail. Far less likely, however, is careful ethical consideration of what these changes may mean. Even now, many US women find abortion beyond their reach either economically or geographically. These women and their children face what may be life-limiting challenges. The US lacks paid family leave; any job protection for unpaid family leave is limited both in time and by the size of the employer. Housing subsidies are difficult to obtain and many families pay more than half of their income for substandard housing. Child care workers are underpaid; good child care is difficult to find and very expensive. In states that have not expanded Medicaid, healthy women who do not earn enough to qualify for subsidies on the health insurance exchanges may have no insurance at all. If proposals to repeal the Affordable Care Act move forward, many other women may lack access to health insurance and the means to pay for contraception or other forms of health care. Mental health and substance abuse treatment may become increasingly unavailable, potentially increasing the risks of unwanted and unhealthy pregnancies. Proposals to move Medicaid and the related program for children, CHIP, to block grants may significantly reduce the funding for care that is now available.

In the myopia of single-issue politics about abortion, the life prospects of women and children have been marginalized. Justice Ginsburg’s insistence that reproductive rights are fundamental to equality has not drawn the attention it deserves. Without attention to why abortion and contraception matter, we may expect inequality in the United States only to deepen over the next few years.

Featured Image Credit: DC Women’s March by Liz Lemon. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Reproductive rights and equality under challenge in the US appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers