Oxford University Press's Blog, page 390

March 19, 2017

The divide – France, Germany, and political NATO

Europe’s unity is under threat, and if France and Germany cannot muster the will to rescue the European project of integration and cooperation, then all bets are really off. Those who imagine that the EU could falter to no great effect are being naïve. A failed EU would pull down NATO and other vestiges of Western unity, and we would be returning to a 19th century balance of power diplomacy. It is a prospect we should dread.

We should look to Berlin and Paris to inject a degree of sanity into Western diplomacy, but we should also be mindful of historical constraints on their security cooperation. As the NATO Harmel Doctrine illustrates, which turns 50 this year, France and Germany are divided on political vision. They thus fail to mobilize support for a European vision. In effect, NATO’s role, cemented by the Harmel Doctrine, has been to serve as the bedrock for European experiments. The question is whether France and Germany will work with and not in opposition to this condition.

The Harmel Doctrine was NATO’s answer to the challenge of providing for both military defence and political unity. NATO’s military defence role was easily understood from day one, in April 1949. However, Soviet overtures for détente in the 1960s threatened NATO’s political cohesion by invoking the prospect of German neutrality, an “alliance de revers” between France and the Soviet Union, and a Soviet-US marriage of convenience to the detriment of the allies.

The Harmel Doctrine was a hard-fought collective answer to this political challenge. Critically, it established NATO’s political primacy: important changes to Europe’s security architecture, the allies declared, cannot happen in opposition to NATO. Moreover, to maintain a vibrant alliance and avoid strategic surprises, such as the Suez debacle of 1956, the allies recommitted to coordinating key national security decisions inside NATO.

France was not happy with the Harmel Doctrine, having preferred a slimmed down NATO as a military baseline for a new and wider Europe of strong nation-states. France was alone, though, and its failure to mobilize support for its vision led it into the Harmel fold. West Germany was of two minds, favouring a degree of political integration in NATO but fearing a piecemeal approach to détente that might trade German sovereignty for stable East-West relations. West Germany was not alone but it was insecure, and it sought security in tying as many allies as possible to its vision of peace through strength.

Although these outlooks still linger today, France has warmed to NATO. However, the EU are concerned with its large ambitions, especially as the slow pace of EU integration is a source of French frustrations. Moreover, political candidates for the 2017 presidential elections are reviving their distinct versions of Franco-Russian cooperation—as a modernized policy of détente. Germany remains of two minds. This is not only a result of grand coalitions but of a strategic preference for peace through dual strength—in NATO as well as the EU.

Those who imagine that the EU could falter to no great effect are being naïve. A failed EU would pull down NATO and other vestiges of Western unity, and we would be returning to a 19th century balance of power diplomacy.

Harmel NATO outlived the Cold War and became a precondition for continental change in the 1990s and beyond, not least because the United States wanted it so. It led to NATO’s partnerships out East, its enlargement beginning in 1997-1999, its operational engagement in out-of-area operations, and eventually its continuation as the bedrock of 21st century European security. And this is the rub: “Harmel NATO” lives on, providing a red line for geopolitical initiatives that allies should cross only with the greatest of trepidation.

The irony is that the Trump administration appears ignorant of the red line—of Harmel NATO—or at least of its implications. If the Trump administration does not take NATO seriously and offers allies meaningful consultations that confirm NATO’s bedrock role in European security affairs, then Harmel NATO is finished. And this could happen simply by the ignorance of the Trump administration.

The extent to which this could free up France and Germany for joint European leadership is uncertain at best. France carries a legacy of low trust among Atlanticist Europeans. Moreover, going by the historical record, it is not clear that Germany will bow to French military leadership. It did bow to the United States but also had no choice; the history and correlation of forces inside Europe is different. Meanwhile, France seems far from ready to Europeanize its nuclear deterrent, which some argue is the precondition for a more autonomous Europe in the age of Trump. Nor is it easy to imagine French backing for a German nuclear deterrent. For as long as it is unclear whether the two big Europeans will follow one another, it will be difficult for them to ask other Europeans to follow them.

At such a moment of distress we might look to history for guidance. When it was fresh, Harmel NATO got ignored by the United States. This happened as President Nixon pursued great power policy—sidelining allies to appeal to rival powers while pushing them to spend more on defence. It was a moment of great allied distress, and the parallel to the Trump presidency is unmistakable.

The upside of this is that President Nixon did not last and had to resign. The downside is that he did have notable staying power and got re-elected. By implication, the best option for France, Germany, and other allies is to push for sustained and meaningful consultations inside Harmel NATO, effectively calling President Trump’s bluff. It may revive NATO and its support for the EU, and if does not, then a degree of European unity for new action will have been achieved.

Featured image credit: The flag of NATO by Sergeant Paul Shaw LBIPP (Army). OGL v 1 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The divide – France, Germany, and political NATO appeared first on OUPblog.

Celebrating and learning from Philip Roth’s America

On 19 March, Philip Roth will celebrate his 84th birthday. Although Roth retired from publishing new writing as of late 2012 (and retired from all interviews and public appearances in May 2014), the legacy of his more than fifty-year career remains vibrant and vital. And indeed, celebrating Roth’s works and achievements can also remind us of the many lessons his literary vision of America has to offer our 21st century national community and future.

There are many aspects of Roth’s literary career that deserve celebration. His productivity: between 1959’s Goodbye, Columbus and 2010’s Nemesis Roth published twenty-seven works of fiction, averaging more than a book every two years (a productivity that more closely parallels genre writers like Stephen King than frequent Nobel Prize nominees). The originality and diversity of those books, as exemplified by three within three early 1970s years: Our Gang (1971), a political satire of the Nixon administration; the Kafka-esque psychological novel The Breast (1972), in which protagonist David Kepesh metamorphoses into a giant breast; and The Great American Novel (1973), a sprawling and ambitious epic of baseball and America. His willingness to reflect and talk at great length and with humor and nuance about that career, both in his many interviews and in his semi-fictional autobiography The Facts (1988).

Yet I would highlight one particular element of Roth’s career as especially impressive. Like his fellow American titans William Faulkner and Louise Erdrich, Roth has consistently returned across numerous works to the same characters and communities, has worked to create multiple layers of a worldbuilding within his fictional universe. In Roth’s case, that universe is centered on Newark, New Jersey, a historic and troubled and vital American city that might be far too easily forgotten or overlooked were it not for his works. And, even more influentially, Roth’s focal characters, families, and narratives have represented many different generations and experiences, identities and themes, voices and stories within the Jewish American community. Although neither he nor they are solely defined or limited by their Jewish identities, that central thread has made Roth an unquestioned literary exemplar of the Jewish American experience.

In a moment when the American Nazi movement has returned to public prominence in deeply troubling ways, when Jewish Community Centers around the country have had to close due to bomb threats, and when anti-Semitic slurs and hate crimes have become all-too common in our news stories, we all could benefit from reading and engaging with a Jewish American literary titan. And that’s only one of a number of 21st century American lessons we can take away from both individual Roth books and the overall arc of his career.

First edition of The Great American Novel, 1973. Holt, Rinehart & Winston, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

First edition of The Great American Novel, 1973. Holt, Rinehart & Winston, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Of all Roth’s books, by far the most overtly salient to our current moment is The Plot Against America (2004). Inspired in part by Sinclair Lewis’ political satire It Can’t Happen Here (1935), Roth’s novel posits an alternative history in which Franklin Roosevelt is defeated in the 1940 election by Charles Lindbergh, who brings a fascist, anti-Semitic, and pro-Nazi regime to the presidency and the nation. By making his protagonist a youthful Philip Roth, Roth blurs the lines between history, alternative history, autobiography, and fiction yet further, producing as a result a novel that raises a number of vital and relevant questions (about culture and nation, politics and community, social identity and resistance, and more) for 2017 America.

Other Roth books from the final decades of his career, when he turned his literary attention most fully to overarching American themes and questions, can likewise help us engage with vital contemporary questions. The Human Stain (2000), the story of a Jewish college professor who is accused of racism and gradually revealed to be an African American who has passed for much of his life and career, reminds us that race and ethnicity are not the clear-cut dividing lines we too often imagine them to be. American Pastoral (1997), in which the American Dream of Seymour “Swede” Levov and his family is destroyed by his daughter Merry’s 1960s domestic terrorism, asks hard questions about the arc of the 20th century and whether a unified national community is still possible in the early 21st. Nemesis (2010), Roth’s final novel, uses a fictional 1944 polio epidemic to engage with how communities respond to crises and tragedies, from the most negative forms of fear and paranoia and witch-hunting to the possibility of inspiring shared efforts and futures.

Finally, and most broadly, Roth’s career and body of work help remind us of the crucial role that art can play in our culture and society. All of the works and themes I’ve highlighted are connected to that, but so too is Roth’s consistent and exemplary use of humor in all its forms: from satire and sarcasm to wry and ironic self-reflection, slapstick and silliness to the unsettling laughs that come from confronting our hardest truths (like mortality, a central topic of Roth’s final few books). Like all of our greatest comic artists, Roth uses humor to make us think, about ourselves in the most intimate ways and our society in the most sweeping ones. Now more than ever, for that reason among many others, we should return to his books.

Featured Image credit: Newark, NJ, skyline as seen across the Passaic River from Harrison. King of Hearts, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Celebrating and learning from Philip Roth’s America appeared first on OUPblog.

How much do you know about Socrates [quiz]

This March, the OUP Philosophy team honors Socrates (470-399 BC) as their Philosopher of the Month. As elusive as was a groundbreaking figure in the history of philosophy, this ancient thinker is perhaps best known as the mentor of Plato and the developer of the Socratic method. While Socrates remains to some degree mysterious, several ancient sources inform our modern understanding of his life and work.

How much do you know about Socrates? Test your knowledge with our quiz below!

Quiz image: David, The Death of Socrates. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image: Vincent, Alcibiade recevant les leçons de Socrate. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How much do you know about Socrates [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

March 18, 2017

It’s time we talked about transport of the critically ill

Ever stopped at the scene of an accident on a dark night? Treated a heart attack on a remote island? Coordinated the transfer of a critically ill baby with a heart defect?

Were you prepared? Did you have the right toolkit? You need a cool head to perform critical clinical interventions while simultaneously planning the transfer to definitive care.

Almost all patients have a transport phase: whether it’s from the scene of an accident to the hospital (pre-hospital care) or from a small health facility to a larger one (inter-hospital transfer.) It may follow a mass casualty incident (civilian or military) or a serious illness or injury overseas (international retrieval). Transport phases may arise from problems during pregnancy and the neonatal period, through childhood and risk-taking adolescence, to old age and complex multisystem disease. All these patients need skilled coordinated transport care.

While we may not all don a uniform and operate on the front line with emergency services or the military, transport care is everyone’s business. Bodies of water, desert, or mountains separate some patients from the medical facilities they require. At other times it is a stretch of road. Whether you are the isolated rural practitioner with a critically unwell child, a junior doctor phoning a trauma centre, a midwife, or nurse practitioner with an obstetric emergency, you are often unprepared and ill equipped for the transport phase.

Make sure you familiarize yourself with everything you have at your disposable. Image: Ambulans, inuti, Renault Master, Stockholm by Stefan Lindström. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Make sure you familiarize yourself with everything you have at your disposable. Image: Ambulans, inuti, Renault Master, Stockholm by Stefan Lindström. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.You need to prepare the patient for transport. You need to anticipate the likely complications. You may have to accompany the patient by road, air, or sea—or wait to handover to a highly skilled transport team. You may be a member of that transport team, first day, new job. For the unaccustomed, critical care transport is scary. Whether you are just starting out in retrieval medicine or a seasoned veteran, here are ten top tips to always keep in mind.

Look after yourself. Exercise, sleep, and keep museli/granola bars in every pocket. Shifts can be long and work is often intense. Breaks can be few and far between, so rest when you can. Stay hydrated.

Get good with equipment. Examine everything. Push every button, twist every knob. Learn to troubleshoot alarms. You don’t want to be caught out by something while on call.

Be obsessive about battery life, oxygen, and drugs. Take enough in case you are stranded somewhere for a few hours. Bad weather will do this.

Be flexible. You need to be prepared to collect any patient with any disease at any time. You may be tasked to one job and diverted to another. Consider how you will manage multiple patients, and what compromises you can and cannot make.

Use your cognitive simulator. Run through potential problems that may arise with your team while en-route. Be prepared for the worst.

Practice your crew/crisis resource management skills. You will need them. Good communication and diplomacy are vital if you wish to succeed. Making it happen in austere environments is no walk in the park. Remember to thank the referring staff/emergency services at the scene and your team.

Share the load. Discuss cases with colleagues and other professionals. Listen. Examine all solutions. Get feedback. Engage in active case review.

Breathe. Too much adrenaline does not enhance performance. Develop strategies to calm the mind and steady the hand. Yoga and meditation help.

Don’t become arrogant. Pride comes before a fall. Don’t wear your underpants on the outside of your flight suit.

Smile. You have the best job in the world.

Featured Image Credit: Agusta A109K2 of Air – Transport Europe performing a medical evacuation in the western Tatra mountains in Slovakia by Tatransky. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post It’s time we talked about transport of the critically ill appeared first on OUPblog.

Throw out the dog: are pets expendable?

Little Tiger, big enthusiastic Buddy, and laid-back Smokey are some of the furry individuals who share our living rooms, our kitchens, and sometimes our beds. Most people consider their companion animals—their “pets”—to be friends or members of the family.

Despite the depth of many people’s relationships with the cats and dogs who share their lives, many people also assume that these animals are in certain ways expendable: that it matters less that an animal dies than that a human being dies, and that the death of an animal is not as bad as the death of a human being.

Philosopher David DeGrazia, for example, imagines the following scenario: “If a lifeboat is sinking with several normal human beings and a dog aboard, where it is clear that all will drown unless someone is thrown overboard, nearly everyone agrees that it is morally right to sacrifice the dog.” This is because, he says, animals have very little, if any, self-awareness. They lack psychological unity—a connection to themselves in the future—and their mental life is not sustained over time. A dog cares only about the present moment, or just the immediate future. So the death of a dog is not as bad as the death of a human being.

Martha and Millie Image credit: Photo by Sophie Alinton of Martha Kane with Millie. Used with permission of photographer.

Martha and Millie Image credit: Photo by Sophie Alinton of Martha Kane with Millie. Used with permission of photographer.Can that view be philosophically justified? I have my doubts.

The problem is, the criterion of psychological unity and continuity, which is intended to distinguish nonhuman animals from human ones, seems to justify our first throwing overboard the dogs, then throwing out the infants, and then, in order, the one-year-olds, two-year-olds, and three-year-olds, along with those of any age who are severely cognitively disabled. Even a six-year-old, compared to an adult, will have a smaller proportion of mental life sustained over her lifetime, and will have fewer memories and intentions with regard to the future.

Nonetheless, DeGrazia believes that the lifeboat case reflects “our considered judgments about the harm of death.” But who exactly are the people who are giving “our considered judgments”? It is suspiciously convenient that those who are to be sacrificed are precisely those who have no input into the lifeboat decision about whom to sacrifice. These ideas are extraordinarily opportune for any human beings who might well prefer to throw the dog out of the lifeboat rather than to jump out themselves, and are pleased with the notion that animals can, despite—or maybe because of—their innocence, be sacrificed for human benefit.

DeGrazia claims that an extraterrestrial would share his judgment about the expendability of the dog, thus suggesting that there is a god’s-eye or objective view of what is true in the lifeboat situation. But it is inappropriate for the badness of death for nonhuman animals to be assessed solely by reference to a criterion that has little or no connection to their lives. While dogs may have a low degree—if any—of psychological investment in and unity with their own futures, they do have capacities for enjoying their lives and forging connections with human beings and other animals. It is the termination of these capacities that makes death bad for them.

Setting aside extraterrestrials, the “considered judgments” about whom to toss from the lifeboat are in fact not likely to be unanimous. First, it seems unlikely that beings who do not fall into the category of “normal human beings” would accept DeGrazia’s “considered judgment.” I imagine if a puppy were to be thrown overboard, and his canine mother witnessed the act, she would oppose it. Also, I’m not sure that children would favor discarding the dog.

Bella in a Boat. Image Credit: Photo by Peter Renders of Bella. Used with permission of photographer.

Bella in a Boat. Image Credit: Photo by Peter Renders of Bella. Used with permission of photographer.Even among adults, most people don’t use psychological unity and continuity to ground their judgments about the expendability of individual lives and the badness of death. They are more likely to decide based on their concern for or relationship to the individuals involved. Some people will have a stronger connection to and concern for the dog than any of the people in the boat. writes, “People like to make fun of those who love their dogs ‘excessively,’ but who decides how much love is too much? Why can’t we let ourselves take dog love too seriously?”.

Speaking for myself, although I am, presumably, a member of the category of “normal human being,” I don’t accept DeGrazia’s considered judgment. I regard all the potential deaths in the lifeboat case with horror, and would be unwilling to throw out any of the passengers—including the dog. I only hope if I were ever in those circumstances that I could find the personal strength to volunteer to jump overboard myself.

If we are going to regard Tiger, Buddy, and Smokey as friends or family members, then we need to consider the ethical meanings and implications of our relationships with them. A dog is not necessarily expendable in the way that the lifeboat case seems to imply. Or if he is, a stronger argument is needed before we can justifiably throw him out.

Featured image credit: “Puppy” by Karen Warfel, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Throw out the dog: are pets expendable? appeared first on OUPblog.

March 17, 2017

Today’s Great Crossings: a historian’s view on Trump’s travel ban

Drawing parallels between Jackson’s era and our own is, according to President Trump, “really appropriate” for “certain obvious reasons.” Indeed, both are eras of rapid change characterized by anxieties over race, immigration, citizenship, and America’s destiny.

In the Jacksonian era, the United States, within the span of a few decades, transformed from an East Coast nation into a transcontinental empire. As it grew, the United States confronted diverse populations—dozens of Native American nations as well as settlers of former French and Spanish colonies. Meanwhile, immigrants from around the world poured into American port cities. The young nation, still debating its identity, fractured over how to deal with such diversity. Some favored extending the democracy born of the American Revolution to immigrants and people of color, while others argued that these groups lacked the qualifications for citizenship.

A progressive vision of the future prevailed at Great Crossings, a village in Kentucky where Indians, settlers, and slaves came together and tried to carve paths to the future. Great Crossings was the site of the first federally controlled Indian boarding school, Choctaw Academy. Initially a collaboration with the Choctaw Nation, the school eventually hosted over 600 students from 17 different Indian nations. Part of the US government’s “Civilization Policy,” whereby the United States sought to assimilate Indians, Choctaw Academy sought to transform foreign nationals into US citizens. Though ethnocentric, policymakers assumed that Native Americans’ intellects equaled those of whites. Unlike most Indian boarding schools, Choctaw Academy was voluntary, and Native peoples had their own reasons for attending. As the United States had become increasingly aggressive in its territorial ambitions, Indians desperately wanted new solutions for peaceful cohabitation, including more effective mediators. Some students believed that one day they would hold dual citizenship in the United States and their own Indian nation.

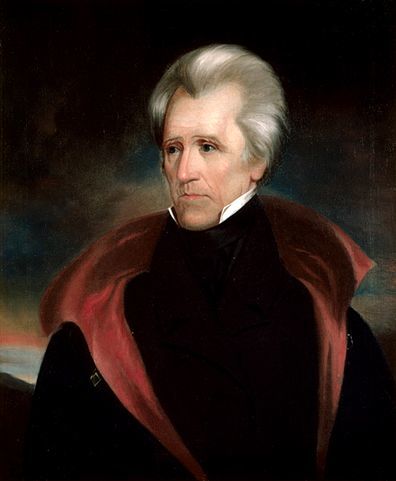

Portrait of Andrew Jackson, the seventh president of the United States by Ralph Eleaser Whiteside Earl. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Portrait of Andrew Jackson, the seventh president of the United States by Ralph Eleaser Whiteside Earl. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Great Crossings was chosen as the school site because it was home to Richard Mentor Johnson, a famous politician who eventually became vice president. Johnson’s plantation was also home to dozens of enslaved African-Americans including Julia Chinn, who was Johnson’s lover and the mother of his two children. Johnson upheld a unified vision of humanity, claiming that only social inventions—namely, slavery and prejudice—divided people. Meanwhile, Chinn embraced American middle-class values as a path to inclusion. In preparation for emancipation, the couple’s daughters and several other Chinn family members were covertly educated at Choctaw Academy. “Amalgamation,” as it was then called, was considered the most radical path to integration, but other progressive movements were popular: Kentucky was home to the South’s largest emancipation crusade, and most northern states had completely abolished slavery.

The election of 1828 signaled a change. By the 1820s, most states had dropped property requirements for voters, a move that empowered common white men. In the election of 1828, these men overwhelmingly supported Andrew Jackson, an anti-establishment figure. Jackson was a zealous warrior, leading a series of bloody campaigns against Indian and imperial rivals who challenged US domination of the continent. Jackson’s military victories allowed the United States to expand into the deep South, opening up hundreds of millions of acres to land-hungry whites. While many Americans lauded Jackson as a success story, others have questioned his methods and temperament.

During the Red Stick War of 1813–1814, Jackson led US troops against a faction of the Muscogee Creek Nation. Jackson gave little quarter to Creek non-combatants, a move reminiscent of Trump’s pledge to “take out” the families of terrorists. During the 1813 Battle of Tallushatchee, US troops burned the village, killing 186, many of them women and children. When some attempted to flee, Jackson’s troops “shot them like dogs,” as one solider recalled. Jackson’s behavior alarmed many, including Thomas Jefferson, who explained, “He is one of the most unfit men I know of for such a place. He has very little respect for laws and constitutions.”

Jefferson hoped that Jackson’s “passions” might cool if he ascended to the presidency. On the contrary, Jackson made good on his campaign promises. Chief among these promises was Indian removal. Jackson, like Trump, targeted minorities, depicting them as internal enemies who threatened national security and economic prosperity. US treaties with Indian nations, many of which Jackson had personally negotiated decades earlier, guaranteed them perpetual rights to land and self-government. Yet Jackson called such treaties “an absurdity,” a relic of an earlier era during which the United States had been too weak to dominate Indians. In defiance of an 1832 Supreme Court decision that upheld Native treaty rights, Jackson used executive power and his party’s Congressional majorities to force Indian removal. Although the Trail of Tears is typically associated with the Cherokees, whose nation captured the media’s attention, Indian removal was actually a blanket policy aimed at forcing all Indians west of the Mississippi River.

Monument on New Echota Historic Site honoring the Cherokees who died on the Trail of Tears uploaded by Cculber007. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Monument on New Echota Historic Site honoring the Cherokees who died on the Trail of Tears uploaded by Cculber007. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Ultimately, 100,000 Native Americans marched the Trail of Tears; 20% died because of violence, disease, or starvation. Indian removal paved the way for slavery’s expansion. Nearly one million African-Americans were forced south and west to the notoriously harsh slavery of the expanding cotton frontier. Contrary to the expectations of many, slavery grew in both scope and scale in the decades before the Civil War. Meanwhile, in both the North and South, new restrictions on free people of color reversed the gains of the Revolutionary generation. Jackson could not even deliver on his promises to non-elite white men: the best Indian land was seized by land speculators and wealthy planters. Amid these pressures, the progressive experiment at Great Crossings fell apart, and its people fractured, trying to survive in an increasingly racist society.

Today, we confront our own great crossing: How should we treat marginalized people who are intimately connected to the United States but lack citizenship? Whose rights should be sacrificed in the name of national security? Will the United States fulfill treaty obligations with Native nations? Can the United States persist in a project, pursued by fits and starts since the Revolution, to fully extend the rights of citizenship to people of color, women, and persecuted minority groups? Americans like to believe that time inevitably brings progress. But history reminds us that progress is hard-won and must be actively cultivated to survive.

Featured image credit: “President Donald J. Trump and Vice President Mike Pence at the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., Jan. 27, 2017” by James Mattis. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Today’s Great Crossings: a historian’s view on Trump’s travel ban appeared first on OUPblog.

The life of Saint Patrick [part two]

Saint Patrick’s Day was made an official Christian feast day in the early 17th century, and continues to be recognized today. It commemorates the death of Saint Patrick, the introduction of Christianity into Irish culture, as well as Irish nationalism.

To celebrate, we’ve pulled a two-part excerpt from Celtic Mythology: Tales of Gods, Goddesses, and Heroes in which Philip Freeman tells the story of Saint Patrick.

When we last left Patrick, Lucet Máel had challenged him to a duel of miracles. By blessing the plain and causing the snow to melt, Patrick invoked the anger of Lucet Máel called down darkness onto the land. When urged by the crowd, the druid was unable to bring back the light. But Patrick prayed to God, bringing back the sun.

Part two continues below.

After these contests the king told both Patrick and the druids to throw their books into the water to test whether they would be damaged. Patrick agreed to do this, but the chief of the druids said he did not want to be judged by water, for water was sacred to the holy man—for he had heard that Patrick baptized in water.

“Then throw your books into fire,” the kings said.

Patrick agreed, but again the druid said he would not, for fire was also sacred to the Christian.

“This is not true,” said Patrick to the druid. “I challenge you to go into an enclosed house along with one of my young followers. You wear my robe while my boy wears yours. Then set the house on fire and be judged by the Most High.”

The druid agreed to this, so that a house was filled wet and dry wood. Holy Patrick sent his young disciple Benignus into the part of the house with dry wood wearing the robe of the druid. The druid entered the half with wet wood wearing Patrick’s robe. The building was then sealed and set on fire while all the people watched.

Stained glass window at Saint Patrick Catholic Church in Columbus, Ohio depicting St. Patrick baptizing the king. “Saint Patrick Catholic Church” by Nheyob. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Stained glass window at Saint Patrick Catholic Church in Columbus, Ohio depicting St. Patrick baptizing the king. “Saint Patrick Catholic Church” by Nheyob. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Through the prayers of Patrick, the flames completely consumed the druid and the house, but left Benignus untouched. The robe of Patrick however was not harmed, while the garment of the druid burned away.

The king was very angry, but Patrick spoke to him:

“Unless you believe now, you will die. For the fury of the Lord has fallen upon your head.”

King Lóegaire then called together his counselors to ask what he should do.

“It is better to believe than die,” they told him.

So the king came reluctantly to Patrick to be baptized.

“You come to me now,” said Patrick to Lóegaire,” but it would have been better for you if you had believed me right away. You shall remain as king, but because of your disbelief your descendants will not rule after you.”

Patrick then went forth and preached the gospel across Ireland, baptizing all who believed in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and confirming the power of the Lord with miracles and wonders.

Her parents did not know what to do with her, so when they heard of Patrick and his wondrous work in Ireland, they journeyed there with her to speak with him.

“Do you believe in God?” Patrick asked Monesan.

“I do with all my heart,” she said.

Then Patrick baptized her with water and the Holy Spirit.

Immediately she fell down dead.

She was buried there in Ireland where she died. 20 years later her remains were carried with honor to a nearby chapel, where her relics are adored to this day.

During these days there was a wicked British king named Corotic who was a great persecutor and murderer of Christians. Patrick wrote to him to urge him to follow the way of truth, but Corotic only laughed at him.

When this was told to Patrick, the holy man asked the Lord to expel the king from his presence then and forever more.

One day not long after this, Corotic heard the sound of music and a voice singing to him that it was time for him to leave his throne. Then all of his family and followers burst into the same song. Suddenly, in the midst of them all, Corotic was changed into a fox and ran out of his palace. After that he was never seen again.

In these days there lived in Ulster a wicked, murderous pagan named Macc Cuill moccu Graccae who was so savage he was called the Cyclops. One day he was sitting on a hill looking for travelers to rob and kill when he saw Patrick coming down the road. Macc Cuill recognized the holy man and decided to test him before slaying him. He had one of his men pretend to be gravely ill and brought the man before Patrick to be healed.

“If he had truly been sick,” Patrick said, “then you wouldn’t be surprised by his current condition.”

Macc Cuill pulled back the sheet covering the man and saw that he was dead. The outlaw was struck with sorrow and guilt over what he had done.

“Forgive me, Patrick” he said. “I confess my wickedness and submit myself to the judgment of your God.”

Patrick baptized him and told him that to be forgiven by the Lord he must go down to the sea and cast himself from shore in a small boat with no food, water, or oars. He must let God take him where he would, whether to death or life.

Reputed burial site of Saint Patrick in Downpatrick, Northern Ireland. “Saint Patrick’s grave Downpatrick” by Man vyi. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Reputed burial site of Saint Patrick in Downpatrick, Northern Ireland. “Saint Patrick’s grave Downpatrick” by Man vyi. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.“I will do as you have said,” replied Macc Cuill.

He went down to the sea and fettered his feet in chains and threw away the key. Then he set out to sea as he had been told. The north wind blew him for days until he came to an island. There he found two righteous priests who trained him in the way of the faith. He spent the rest of his life on that island and in time became a bishop famous for his holiness and wisdom.

One day Patrick was preaching by the sea on a Sunday when he was troubled by the noise of some pagans digging a ditch around a fort. He ordered them not to work on the Lord’s day, but they ignored him.

“Mudebroth!” he shouted. “You will gain nothing from your labor.”

The next day a great storm arose and destroyed all the work the pagans had done, just as Patrick had said.

When the time came for Patrick to die, an angel came to him and told him that God would grant him four petitions that he had sought.

The first was that his authority would ever after be in the city of Armagh. The second was that whoever sang his hymn would have the penance for their sins decided by him. The third was that the descendants of Díchu, who had first welcomed him to Ireland, would be granted mercy and would not perish. And the final petition was that all of the Irish would be judged by him at the end of the world.

And so on 17 March, in the 120th year of his life, Patrick passed from this life into the hands of God.

Featured image credit: “Clover” by damesophie. CCO Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The life of Saint Patrick [part two] appeared first on OUPblog.

Test your general knowledge about sleep

Sleep is defined as “a periodic state of muscular relaxation, reduced metabolic rate, and suspended consciousness in which a person is largely unresponsive to events in the environment”. It comes easily to some, and much harder (sometimes impossible) to others, but we all need it in order to function day-to-day.

Not only is it required to stay healthy, it also allows a space for our brains to think out problems whilst we doze. As John Steinbeck once said, “It is a common experience that a problem difficult at night is resolved in the morning after the committee of sleep has worked on it”.

We’ve created a quiz to test your knowledge on a few different aspects of sleep – how much do you know?

Quiz image credit: Photograph by nomao saeki. CC0 1.0 Public Domain via Unsplash.

Featured image credit: ‘Soft Comforts’ by Alexander Possingham. CC0 1.0 Public Domain via Unsplash.

The post Test your general knowledge about sleep appeared first on OUPblog.

Down at the crossroads: the intersection of organizing and oral history

In the last few weeks, we have explored the possibilities oral historians have for using their work to create and promote changes in the world around us. Joshua Burford explained how listening to activists of the past helps locate hope and direction in the present. Holland Hall and Alexandra Weis shared their experiences at the Women’s March on Washington, and the power of listening for creating change. Today, Daniel Horowitz Garcia asks where oral history and organizing come together, and how focusing on public engagement can change the structure and value of oral history.

The crossroads, in Southern folklore, represents a place where worlds meet. It is a place where realities collide and deals can be made. Since the 2016 election I have experienced colliding realities on an almost daily basis. Until then my 20 years’ experience as an organizer and my 10 years’ experience in oral history overlapped in areas and at times but for the most part seemed separate. After the November election that is no longer the case.

Within weeks of the election I was interviewing members Project South, a southern-based, movement-building organization I worked for 12 years ago. By the end November 2016 I launched Feeling Political, a podcast about politics, emotions, and action. My original plan was to produce five or six episodes by talking to thinkers and organizers about how they felt about politics and what we should be doing. Instead I produced 11 shows, one bonus episode, and will start the second season this summer.

The premise of the podcast is that not everyone gave up hope because Trump won. In fact, there are many people who did not fundamentally change their basic political strategy because of the presidential election. These people’s optimism and hope about the future is not connected to the electoral process. Of course work adjusts based on different election results, but a Democrat’s loss or a Republican’s win does not alter how marginalized people must approach politics to survive. A fish swims even though there are sharks about, but she learns to swim well. I thought the shock of a Trump presidency was a good time to talk to some of these folks. I asked them three questions: how do they wish to be identified, how do they feel in this political moment, and what’s their advice to someone about what should be done. In addition, I asked anyone who wished to use their phone and email me a voice memo answering the same questions.

The premise of the podcast is that not everyone gave up hope because Trump won.

Asking people how they felt after the election was a powerful question. Through the podcast I found that talking with people affiliated with an organization, such as Project South, was an efficient way to gather interviews but also a collective learning process. I asked past and present board members and staff of Project South my three questions. The audio, ranging from five to eight minutes, will form the basis for a collaboration on political education curriculum incorporating emotions and politics. The goal is to help participants analyze and strategize about their work. This type of partnership will be, hopefully, the frame of the podcast in each season. I am not pretending that a podcast is an organizing or an oral history project. But I have learned from this experience that there is overlap in the skill sets.

Dan Kerr’s 2016 article for the Oral History Review, as well as the accompanying presentation at the OHA 2016 conference, argued there are methods of oral history that do not owe allegiance to Allan Nevins and the Columbia School. Furthermore, Kerr argued that oral history of or in service to an activist project does and should pursue a different methodology than the Nevins school. I thought about that argument when I heard a participant at the OHA conference argue that oral history and organizing do not share a skill set. I believe the participant is objectively wrong, and I think Kerr’s observation about different methodologies explains why someone would make that mistake. Simply put, oral history aimed at improving organizing or facilitating a victory may no longer look like oral history, at least not the academic kind. This doesn’t necessarily make things easier. If the organizing centered, then what happens to oral history standards? The field has spent decades struggling to develop guidelines that protect participants. Protections must exist whether or not Nevins can recognize the project. This is just a single example of complications of combining scholarship with activism. At the crossroads the future is uncertain, so if you show up be ready to make a deal.

Simply put, oral history aimed at improving organizing or facilitating a victory may no longer look like oral history, at least not the academic kind.

Society is changing all the time. Making social change a goal, therefore, does not seem useful. How are people engaging, or not, in change? To what end? These are good questions for the organizer or the oral historian. How do we engage with people and to what end are even better. I haven’t identified as an organizer for years, but the goal of the podcast is to move people to action. The deal I’ve made is that oral history skills, like listening and amplifying people’s voices, is enough to make that happen.

Forgive the Hegelian overtones, but when two realities collide don’t they make something new? Presently, I sit at the crossroads. My realities are colliding, and I am making deals.

Featured image credit: “2017.02.04 No Muslim Ban 2, Washington, DC USA 00521” by Ted Eytan, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post Down at the crossroads: the intersection of organizing and oral history appeared first on OUPblog.

Celebrating Samuel Barber and his Adagio for Strings

Last week, we celebrated what would have been American composer Samuel Barber’s 107th birthday. Upon the composer’s death in 1981, New York Times music critic Donal Henahan, penned an obituary that asserted “probably no other American composer has ever enjoyed such early, such persistent and such long-lasting acclaim.” Despite Barber’s great popularity with audiences, performers, and many critics, there is an unusually small amount of scholarly literature on his life and music, with scholars often casting Barber as a relatively insignificant, neo-Romantic composer.

There is perhaps no better reflection of Barber’s impact on American music culture than the legacy of his Adagio for Strings. In a 2004 BBC radio survey, the Adagio earned itself the title “the saddest song ever written” and has been utilized in several contexts that would support its new moniker. The Adagio was originally written as the middle movement of Barber’s first string quartet, op. 11 (1936) but exists today in myriad re-imaginations, some by the composer himself, some by close confidants of Barber, and still others that Barber likely would never have been able to imagine.

Barber created a five-part version of the Adagio for string orchestra that was premiered by Arturo Toscanini in 1938 and is the version most commonly heard today. This arrangement exploded into the American consciousness in 1945 when it was broadcast alongside a radio announcement of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s death. Musicologist Luke Howard argues that this event marked the beginning of a process through which the Adagio garnered its connotation of sadness and mourning. The piece continued to be imbued with melancholy when it became the foundation to the media soundtrack during coverage of President John F. Kennedy’s funeral in 1963. Writer and director Oliver Stone utilized the piece in his 1986 film Platoon, which depicts the horrors of the Vietnam war, and continued the semiotic association of the Adagio. Most recently, in the aftermath of the September 11 terrorist attack, the Adagio became an integral part of the musical soundscape of a nation in mourning. American conductor and the BBC Symphony Orchestra’s chief conductor Leonard Slatkin, for example, conducted the final night of the 2001 BBC Proms with a tribute to the United States centered around the finale of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony and Barber’s Adagio.

John F. Kennedy’s funeral procession leaves the White House on 25 November, 1963. Abbie Rowe, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

John F. Kennedy’s funeral procession leaves the White House on 25 November, 1963. Abbie Rowe, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.But it would be shortsighted to view the Adagio as merely a piece of sad music. It’s music of reflection; music of peace. This can be seen in Barber’s own 1967 arrangement of the piece for chorus using the Agnus Dei text of the mass.

The piece has also made its way into electronic dance music (EDM) where it became a staple at raves, and a hugely popular song in the realm of trance after DJ Tiësto created his own arrangement in 2004. And just as Barber’s original Adagio was voted “the saddest song ever written,” Tiësto’s version was voted the second greatest dance track of all time by Mixmag readers in a 2013 survey.

The Adagio’s ability to reach the zenith in both the category of sadness and dance is perhaps the greatest indication of the diverse impact that this piece has had in the past 80 years both in the United States and around the world. It has been featured in television shows (The Simpsons, South Park, and How I Met Your Mother), films (The Elephant Man, Lorenzo’s Oil, Platoon), and in video games (Homeworld). The impact of this single piece alone cements Barber’s legacy not only in American art-music culture, but also popular culture as well.

Featured Image credit: Samuel Barber’s transcription of Claude Debussy’s Syrinx, 1960. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Celebrating Samuel Barber and his Adagio for Strings appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers