Oxford University Press's Blog, page 388

March 24, 2017

The historian and the longitude

If a social conversation turns to the history of navigation – a turn that is not so unusual as once it was – the most likely episode to be mentioned is the search for a longitude method in the 18th century and the story of John Harrison. The extraordinary success of the book by Dava Sobel has popularised a view of Harrison as a doughty and virtuous fighter, unfairly disadvantaged by the scientific establishment; they failed to recognise, in the words of her title, “a lone genius who solved the greatest scientific problem of his time.” Does a broader history of navigation justify the common assent to this account, reinforced through film and television (not to mention BAFTA awards)?

When Harrison arrived in London in the 1730s with ambitions to build a successful longitude timepiece, he was supported and encouraged by Fellows of the Royal Society, who occasioned the very first meeting of the Board of Longitude (formed some 20 years previously), at which a clock presented by Harrison was the only item of business. He requested, and was granted, the very considerable sum of £500 to work on a second timepiece, to be finished in two years (the annual salary of the Astronomer Royal was £100). This was the first of a series of grants that had amounted to £4,000 by the time Harrison announced in 1760 that his third timepiece was ready for testing. It had taken 19 years to complete and the Board were, not unreasonably, becoming doubtful whether this was the route to a practical solution to the problem. To say that such a sum was inadequate is to ignore completely the simple fact that this was the 18th century, long before the accepted notion of government grants for research and development, but this is just one example of where a historian becomes frustrated with the popular narrative.

In the event, Harrison asked for a fourth timepiece – quite unlike the first three – to be given the statutory test of keeping time on a voyage to the West Indies. Many difficulties and arguments had to be overcome before a satisfactory test was completed in 1764, when everyone agreed that ‘the watch’ had kept time within the limits required for the maximum award of £20,000. It was now that the Board’s difficulties began in earnest. Faced with the real prospect of parting with their major award, they needed to know that the longitude problem really had been solved – anything less would have been a very public failure to fulfilling their central responsibility. The original Act of Parliament of 1714 offered the reward for a method that was ‘Practicable and Useful at Sea’, while stipulating that the test was to be a single voyage. The Board were troubled over whether these two criteria were compatible, and such doubts were being aired in the popular press. Was the legislation itself inadequate?

So far the Board had not been given a detailed account of the watch’s manufacture and operation, and they wanted to know what principles or manufacturing procedures had resulted in its outstanding performance. Could these be explained and communicated to other makers? Could such watches be manufactured in numbers, in a reasonable time, at a reasonable cost, by moderately competent makers? Might the success of Harrison’s watch have been a matter of chance in a single instance? Had it depended on the achievement of a wholly exceptional, individual talent? All of these considerations were relevant to the question of a ‘practicable and useful’ method, notwithstanding the recent performance of the watch.

John Harrison ship chronometer, between 1761 and 1800. Great Brittain. Technical Museum, Oslo, Norway by Bjoertvedt. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

John Harrison ship chronometer, between 1761 and 1800. Great Brittain. Technical Museum, Oslo, Norway by Bjoertvedt. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The Board decided to separate the components of the legislation by granting Harrison half the full reward, once he had explained the watch and its operation, while retaining the other half until it could be proved that watches of this type could go into routine production. Harrison did ‘discover’ his watch, as it was said (that is, literally, he removed the cover and explained its working), and so was granted £10,000, but gave up on the Board and appealed to Parliament and the King for the remainder.

In many ways the Board were left, as they had feared, without a practical solution. Harrison’s watch did not go into regular production. He had shown that a timepiece could keep time as required, but the design of the successful marine chronometer, as it emerged towards the end of the century, was quite different from his work. Other makers, in France for example, had been making independent advances, and two English makers, John Arnold and Thomas Earnshaw, brought the chronometer to a manageable and successful format. It is difficult to claim without important qualification that Harrison solved the longitude problem in a practical sense. In the broad sweep of the history of navigation, Harrison was not a major contributor.

The Harrison story seems to attract challenge and controversy. The longitude exhibition at the National Maritime Museum in 2014 was an attempt to offer a more balanced account than has been in vogue recently. The Astronomer Royal Nevil Maskelyne, for example, has been maligned without justification. A recent article in The Horological Journal takes a contrary view and offers ‘An Antidote to John Harrison’, and we seem set for another round of disputation. From a historian’s point of view, one of the casualties of the enthusiasm of recent years has been an appreciation of the context of the whole affair, while a degree of partisanship has obscured the legitimate positions of many of the characters involved. There is a much richer and more interesting story to be written than the one-dimensional tale of virtue and villainy.

Featured image credit: Pocket watch time of Sand by annca. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The historian and the longitude appeared first on OUPblog.

March 23, 2017

Self-portraits of the playwright as a young man [part one]

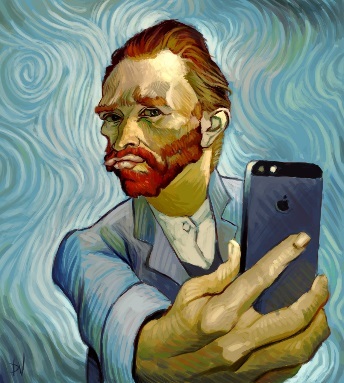

Are today’s selfies simply yesterday’s self-portraits? Is there really that vast of an epistemological chasm between Kim Kardashian’s photos of herself on a bloated Instagram account and the numerous self-portraits of Rembrandt or Van Gogh hanging in art museums and galleries around the world? Aren’t they all really just products of their respective eras’ “Je selfie, donc je suis” culture, with perhaps only technological advances (and, admittedly, talent) separating them?

The debate is surely a lively one, but one of the most significant differences noted by art bloggers between selfies and self-portraits is the conversation that they both generate. Selfies are external surface recordings, from the here and meant for the now, that are intended to speak essentially to those who know (or admire) their subject. Self-portraits, on the other hand, are artfully wrought introspections, made in the now but meant for the future, that hope to speak to and for the self and all of humanity. Technology has seemingly little to do with the debate, since there as many selfie paintings as there are smartphone self-portraits.

Few people are aware that the talents of arguably America’s greatest playwright, Tennessee Williams, extended from the pen to the paintbrush, and yet he produced almost as many paintings during his lifetime, including several self-portraits, as he had one-act and full-length plays. More than just a leisure activity or a medium to dabble in when his career in the American theater was suffering, painting was a means for Williams to both express his creative vision and experiment with form, movement, color, and composition, four elements that were central to his dramatic theory on the plastic theater. Williams was no dilettante with a paintbrush, and many of his paintings shed light on the development of his theater, just as his plays speak to the canvases he was painting at the time.

“The Art of the Selfie” 2015 by Dylan Verleul. Used with permission.

“The Art of the Selfie” 2015 by Dylan Verleul. Used with permission.Whether composing a poem, developing a short story, or sketching a character for a play, Williams drew extensively from his lived experiences and put them onstage or on the page for all to see or read. In his essay “The Past, the Present, and the Perhaps” (1957), Williams admitted that “nothing is more precious to anybody than the emotional record of his youth, and you will find the trail of my sleeve-worn heart” carved into each of his works. And while audiences might have first adored the “sleeve-worn heart” of the younger Tennessee Williams, those guilt-ridden romantic Tom Wingfields of the early plays like The Glass Menagerie (1945), they soon grew tired of it and later bemoaned the older Tennessee Williams, those bitter, self-indulgent Augusts of his late plays like Something Cloudy, Something Clear (1981). Perhaps over-familiarity and the passage of time define the moment when self-portraits became selfies. I mean, do we really think Kim Kardashian will have as many Instagram followers in, say, thirty years, if she keeps on posting daily selfies? Time may prove me wrong, but I doubt it. She is a product, or more precisely a brand, of her time. The fact that Williams was still posting “self-portraits” of himself onstage well into his seventies had more to do with the artist’s need to study his self through time than it did with the man’s need to brand that self for instant viewer gratification. Williams sought more than anything the audience and critical approval that had eluded him from the late sixties till his death in 1983, but the fact that he kept putting himself out there onstage, time and time again, showed more his deep yearning for self-study and, perhaps, even self-atonement, than it did for a few likes or thumbs up. Tennessee Williams’s plays, then, are self-portraits in words, not selfies.

Featured image credit: Artistic take on Jan Vermeer’s The Girl with the Pearl Earring by Mitchell Grafton. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Self-portraits of the playwright as a young man [part one] appeared first on OUPblog.

Winnicott on creativity and living creatively

Donald Winnicott (1896–1971) is one the most original and creative thinkers in the history of psychoanalysis after Freud. His theories about the early interaction between the infant and its environment, transitional objects and phenomena, true and false self, the relation between the analysand and the analyst, and many other topics have been of great importance for psychoanalysts, psychotherapists, social workers, teachers, and others all over the world.

Winnicott’s influence continues to be powerful more than 40 years after his death, as can be seen by a quick look at the PEP Psychoanalytic Literature Search: the three most read journal articles today are written by Winnicott.

What is it about Winnicott’s texts that so attract readers? I think it is the personal, living quality of his way of writing. There is in it a mixture of depth, density, and lightness. Not all psychoanalytic writers have a personal style of their own. Winnicott possessed it to a high degree; you can sense his presence and his intelligence in the text. He had both a light and distinct hand, as well as a special ability to use ordinary words to say extraordinary things.

Winnicott does not teach or instruct the reader. He communicates and you feel yourself involved in a creative exchange that reaches and resonates in different levels of the mind. He often gives one an experience of having previously known or sensed what he is expressing but of not having thought or formulated it, and yet, at the same time his writing gives a feeling of surprise and discovery.

87 Chester Square London – Belgravia. pediatrist & psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott lived there (1951-1971). Photo by Pierrette13. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

87 Chester Square London – Belgravia. pediatrist & psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott lived there (1951-1971). Photo by Pierrette13. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.One basis for this experience is Winnicott’s tolerance of paradoxes, which implies an appreciation of unconscious thinking and of dream-life. Throughout Winnicott’s writings the issue of creativity and of living creatively is essential. His theories on this subject are linked to his ideas about the “potential space” and the transitional object (a concept originating from him) with its paradoxical quality of being both found and created, coming both from inner reality, fantasy and dreaming and from outer reality. In his introduction to Playing and Reality (1971) he writes:

“I am drawing attention to the paradox involved in the use by the infant of what I have called the transitional object. My contribution is to ask for a paradox to be accepted and tolerated and respected, and for it not to be resolved. By flight to split-off intellectual functioning it is possible to resolve the paradox, but the price of this is the loss of the value of the paradox itself.”

Winnicott sees the origin of a “potential space” in the early reliable relationship between the infant and the mother (or other caretaker). From the original unit mother/infant there develops a subtly increased distance between them, and in this “intermediate area” the infant intuitively selects a transitional object (a blanket, a piece of wool, a teddy-bear) which for the infant has the paradoxical quality of being both found and created by the infant. As the child grows, the transitional object will lose its importance, but this way of experiencing is preserved in the child’s playing and becomes spread out between “inner psychic reality” and “the external world”.

The potential space is the space for experiencing life creatively, be it a landscape, a theatrical or musical performance, a poem, or another individual and it is here that meaningful psychotherapy takes place. Winnicott writes:

“I have tried to draw attention to the importance both in theory and in practice of a third area, that of play, which expands into creative living and into the whole cultural life of man… [this] intermediate area of experiencing is an area that exists as a resting-place for the individual engaged in the perpetual human task of keeping inner and outer reality separate yet interrelated… it can be looked upon as sacred to the individual in that it is here that the individual experiences creative living.”

Winnicott insisted on the uniqueness of each individual and the right to, and importance of, discovering the world in a personal, creative way. This of course also applies to psychoanalysts and to psychoanalytic theory, and for that matter to any other field. In a paper given to the British Psycho-Analytical Society in 1948, he asks “… has due recognition been given to the need for everything to discovered afresh by every individual analyst?”

Featured image credit: Art by Pexels. CC0 Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Winnicott on creativity and living creatively appeared first on OUPblog.

How new is “fake news”?

President Donald Trump’s administration is accused of disseminating “fake news” to the shock of the media, tens of millions of Americans, and to many others around the world. So many people think this is a new, ugly turn of events in American politics. What does American history have to say about this?

When George Washington announced that he did not want to serve as president for a third term, Thomas Jefferson let it be known that he was interested in the job. That was in 1796. Vice President John Adams, too, wanted it, and eventually became the second president with Jefferson as vice president. During Adams’ term, Jefferson encouraged the president’s political enemies to speak ill of him so in 1800, when Jefferson again wanted to try for the presidency, a hostile political environment existed. That election is considered to be the first in which “fake news” became part of the American political scene.

A newspaper critical of Jefferson assured readers that he suffered, “great and intrinsic defects in his character,” information an anonymous source close to the vice president had leaked to the press. Jefferson’s supporters let it be known that Adams wanted to be king of the United States by trying to marry off one of his sons to a daughter of English King George III, a move blocked by George Washington who intervened just in time to stop it, or so the story goes. The political conversation remained riddled with false facts, with newspapers reporting, for example, that if Jefferson were president, “Murder, robbery, rape, adultery, and incest will be openly taught and practiced,” that the country would be “soaked with blood, and the nation black with crimes.” Political parties owned newspapers in those days. There was no independent media. In the eighteenth and nineteenth century it was more like FOX and MSNBC—heavily partisan.

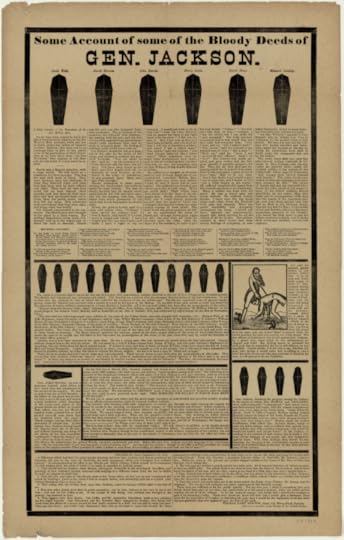

The presidential election of 1828 is considered one of the nastiest in American history. War of 1812 military hero General Andrew Jackson was running against John Quincy Adams, son of John Adams. Jackson’s rivals accused him of murdering prisoners during a military campaign in 1815. The truth was actually that Jackson had ordered their execution after the men’s officers concluded they had deserted their posts, which was against military law. Their execution was the punishment provided by law.

Some account of the bloody deeds of General Andrew Jackson, circa 1828 by Unknown. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Some account of the bloody deeds of General Andrew Jackson, circa 1828 by Unknown. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Jackson had married a teenager, Rachel, while she was still married to her first husband, the couple thinking that her divorce was final; eventually it was resolved and he remarried her in 1794 to make it legal. But his opponents ignored all that and instead accused him of adultery, she of bigamy. Jackson’s supporters reported that Adams, while ambassador to Russia, procured for the czar a young girl for sex, along with other women, to explain why he had been a successful diplomat in Moscow. The press also reported another falsehood: that he had the government pay for a billiards table in the White House, which, in fact, he paid for. And so it went.

Things calmed down a bit in American politics during the second half of the 1800s, although periodically in the first half of the next century more “fake news” occasionally floated around. The calmest period came in the post-World War II era, which is why, perhaps, Americans and Europeans have been so shocked by recent events. Forgotten by all, however, is that in state elections all through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries fake news always circulated as facts.

What history teaches us is that American politics seemed to generate more fake news than almost any other activity of the nation, with false advertising coming in at a close second. That reality may help account for why Americans and Europeans are so critical of the dishonesty of politicians. In the United States, politicians have always been considered ethically challenged and too often untruthful, far more than most other professions. Combined with a perception that “Washington never gets anything done,” especially with respect to the US Congress, and we begin to see where “fake news” fits in.

Over the course of two centuries, Americans came to expect politicians and their allies to disseminate fake news, but there were also enough voters who accepted these false facts as true to affect election results. For them, the validity of facts was in the eye of the beholder. “Alternative facts” have been a feature of the American landscape for a long time. Politicians were not alone in using them.

Cigarette manufacturers announced their “scientific research” showed smoking was harmless, while chemical companies proclaimed that DDT was harmless to people. Facebook, run by young executives with understandably little grasp of history, are learning that fake news has always been around and—to their credit—are taking steps to figure out how to winnow them out of their website. It is a mission that generations of news reporters attempted to achieve. In both politics and advertising, enough people accepted “fake news” to justify the practice of misleading political commentary and what had already been dubbed “false advertising” decades ago. So, welcome to a new round of “fake news.”

Featured image credit: “President’s Levee, or all Creation going to the White House From Library of Congress” by Robert Cruickshank as an illustration in the The Playfair papers. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How new is “fake news”? appeared first on OUPblog.

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and differences across cultures

Geert Hofstede, in his pioneer study looking at differences in culture across modern nations, identified four dimensions of cultural values: individualism-collectivism, power distance, uncertainty avoidance, and masculinity-femininity. Working with researcher Michael Bond, Hofstede later added a fifth dimension with called dynamic Confucianism, or long-term orientation. According to Hofstede’s research, people, in individualistic societies, are expected to care for themselves and their immediate families only; while in collectivist cultures, people view themselves as members of larger groups, including extended family members, and are expected to take responsibility in caring for each other. With regards to power distance, different countries have varying levels of accepting the distribution of unequal power. Uncertainty avoidance takes into consideration that the “extent to which a society feels threatened by uncertain and ambiguous situations.” Then, masculinity-femininity examines the dominant values of a culture and determines where these values land on a spectrum in which “masculine” is associated with assertiveness, the acquisition of money and things, as well as not caring for others. Finally, long-term orientation looks at the extent to which a society considers respect for tradition and fulfilling social obligations; some future-oriented values are persistence and thrift.

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions have formed a fundamental framework for viewing others. International business people, psychologists, communications researchers, and diplomats all benefit from Hofstede’s work, as well as everyone else. Utilizing these interpretative frameworks leads to a greater understanding of ourselves and others.

To see differences across cultures more clearly, we compiled a list of illustrations of Hofstede’s concepts in action.

People in collectivistic societies, such as most of Latin American, African, and Asian countries, and the Middle East, emphasize the obligations they have toward their ingroup members, and are willing to sacrifice their individual needs and desires for the benefits of the group. Collectivists emphasize fitting in; they value a sense of belonging, harmony, and conformity, and are more likely to exercise self-control over their words and actions because they consider it immature or imprudent to freely express one’s thoughts, opinions, or emotions without taking into account their impact on others. They care about their relationships with ingroups, often by treating them differently than strangers or outgroup members, which is also known as particularism.

“Sierra Leone” by Annie Spratt. Public Domain via Unsplash.

In high power distance societies, such as many Latin American countries, most of African and Asian counties, and most counties in the Mediterranean area, people generally accept power as an integral part of the society. Hierarchy and power inequality are considered appropriate and beneficial. The superiors are expected to take care of the subordinates, and in exchange for that, the subordinates owe obedience, loyalty, and deference to them, much like the culture in the military. It is quite common in these cultures that the seniors or the superiors take precedence in seating, eating, walking, and speaking, whereas the juniors or the subordinates must wait and follow them to show proper respect. The juniors and subordinates refrain from freely expressing their thoughts, opinions, and emotions, particularly negative ones, such as disagreements, doubts, anger, and so on. Most high power distance societies are also collectivistic societies, aside from a few exceptions such as France.

In low power distance countries such as Israel, Denmark, and Ireland, people value equality and seek to minimize or eliminate various kinds of social and class inequalities. They value democracy, and juniors and subordinates are free to question or challenge authority. Most low power distance cultures are also individualistic societies.

People from high uncertainty avoidance cultures, such as many Latin American cultures, Mediterranean cultures, and some European (e.g., Germany, Poland) and Asian cultures (e.g., Japan, Pakistan) tend to have greater need for formal rules, standards, and structures. Deviation from these rules and standards is considered disruptive and undesirable. They also tend to avoid conflict, seek consensus, and take fewer risks.

“Xi’an Bell Tower, Xi’an, China” by Lin Qiang. Public Domain via Unsplash.

In low uncertainty avoidance cultures, such as China, Jamaica, and the United Kingdom, people are more comfortable with unstructured situations. Uncertainty and ambiguity are considered natural and necessary. They value creativity and individual choice, and are free to take risks.

In masculine cultures, such as Mexico, Italy, Japan, and Australia, tough values – such as achievements, ambition, power, and assertiveness – are preferred over tender values – such as quality of life and compassion for the weak. Additionally, gender roles are generally distinct and complementary, which means that men and women place separate roles in the society and are expected to differ in embracing these values. For instance, men are expected to be assertive, tough, and focus on material success, whereas women are expected to be modest and tender, and focus on improving the quality of life for the family.

In feminine cultures, such as most of Scandinavian cultures, genders roles are fluid and flexible: Men and women do not necessarily have separate roles, and they can switch their jobs while taking care of the family. Not only do feminine societies care more about quality of life, service, and nurturance, but such tender values are embraced by both men and women in the society.

Based on the teachings of Confucius, long-term orientation deals with a society’s search for virtues. Societies with a long-term orientation, such as most East Asian societies, embrace future-oriented virtues such as thrift, persistence, and perseverance, ordering relationships by status, and cultivating a sense of shame for falling short of collective expectations.

Societies with a short-term orientation foster more present- or past-oriented virtues such as personal steadiness and stability, respect for tradition, and reciprocation of greetings, favors, and gifts. Countries with a short-term orientation include Norway, the United Kingdom, and Kenya.

Featured image credit: “Mexico, Puebla, Cuetzalan” by CrismarPerez. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and differences across cultures appeared first on OUPblog.

March 22, 2017

Spelling and knowhow: the oddest English spellings, part 23

We are so used to the horrors of English spelling that experience no inconvenience at reading the word knowhow. Why don’t know and how rhyme if they look so similar? Because such is life. In addition to the ignominious bow, as in low bow, one can have two strings to one’s bow, and I witnessed an incident at a hockey game, when a certain Mr. Prow kicked up a row, complaining of an inconvenient row, but the crowd pacified him, and, as a result, he had to eat crow. By the way, the man’s family name Prow, as he later told me, is pronounced with the vowel of grow, not of prowess or proud. In return, I explained to him that prow (a ship’s forepart) rhymed with grow for centuries and then changed its pronunciation, perhaps to align itself with bow (which bow? Its synonym of course) or for another equally obscure reason (see below). Such changes are trivial. More surprising is the fact that millions of people who are ready to protest anything on the slightest provocation tolerate English spelling and sometimes even defend it for sentimental reasons. Since when have we become so docile and conservative on both sides of the Atlantic? Answer: Since roughly the late Middle Ages.

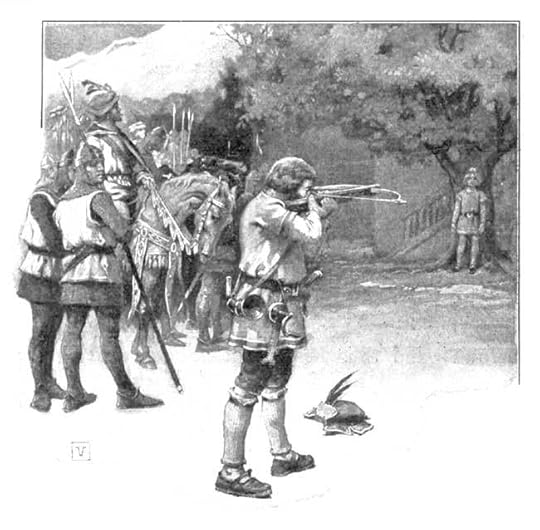

You see William Tell, the unbowed Swiss hero. He had another arrow to his bow, but, fortunately, it was not needed.

You see William Tell, the unbowed Swiss hero. He had another arrow to his bow, but, fortunately, it was not needed.The digraph ou is not very common, but it does occur in soul, foul, ghoul, and Ouida, for example (decades ago, Ouida was one of my favorite authors, and I, naturally, mispronounced her name), and has a different value in each (of course!). Although the number of words with ou is relatively small, it is amusing to compare them with sole, fowl, and mewl (let us pity Ouida and leave her pseudonym mix with rouille or among other weeds in the flowering wilderness of English place and proper names). By contrast, ow is very common and is one of the most confusing orthographic symbols in English. By the same token, the diphthong [ou] can be spelled in several ways. (Signs in brackets designate sounds.) Sometimes all is clear: so, no, ho ho (or just ho: I am sorry)—perfect words in an imperfect world. But then come sow (which sow? Try to guess), oh, hoe, soul ~ sole, bowl, coal, role ~ roll, toll ~ extol, sold, troth (by the way, bowl is one of the most often mispronounced words by foreigners: they associate it with owl and howl—poor benighted foreigners: they are welcome, even though they cannot realize that no English word should ever be pronounced without consulting its transcription in a good dictionary).

Rouille is a kind of French sauce. Have you ever tasted it? Ouida might have liked it.

Rouille is a kind of French sauce. Have you ever tasted it? Ouida might have liked it.In so far as this is an etymological blog, we may look at the history of a few words with ow. To begin with, Middle English had two o-vowels: open and closed. This type of difference is easy to observe: compare open [e] in Modern Engl. man and closed [e] in men; even half-open [e] can be heard at the beginning of the word air. But the two o’s merged rather early in the history of English, and, as a result, groan, for instance (with the historically open o) became indistinguishable from grown (which had closed o). The same merger happened in moan ~ mown and quite a few other words.

The Old English for bow “to bend” sounded as būgan; g was a fricative, or a spirant, that is, the voiced counterpart of ch in Scottish loch. After a, o, and u, this fricative became w. This leap needn’t surprise us; g is articulated in the back of the mouth, and w needs the lips; both are “peripheral,” as opposed to t, d, etc., which are “central.” Peripheral consonants tend to exchange hostages, and būgan yielded būwan. Later, long u (ū) became a diphthong by the Great Vowel Shift, as in now, how; hence bow “to bend.” Bow “an archer’s weapon” goes back to Old Engl. boga. I’ll skip the details, but a look at the pair būgan/ boga makes it clear that the stressed vowels in them were different, as their reflexes still are, and it is a misfortune that today both are designated by ow.

When we see a Modern English word with ow, its phonetic history will usually resemble either bow “to bend” or bow “a weapon.” But there is a chapter that can be called “Spelling strikes back.” The Old English form of low “not high” was lāh (with the inflected form lāge), while low “to moo” was hlōwan. Today they should not have been homophones, but they are, seemingly under the influence of the verb’s written image. At the end of the eighteenth century, many people still rhymed low “to moo” with how. Prowl rhymed with role. Here, [au] is pronounced instead of the expected [ou]. Moult ~ molt has a crystal-clear etymology: it goes back to Latin mūtare “to change,” whose long u was expected to become the same diphthong as in now and how. Even its l is partly mysterious, but it won’t concern us today. Incidentally, the infamous bowl should also have ended up with the diphthong [au], but this did not happen, perhaps for no weightier reason than to bewilder foreigners. Mow “to cut down grass,” from Old Engl. māwan, has only one pronunciation, but mow “grimace,” possibly from French, has two. The variation prow [ou] ~ prow [au] has already been noted. Why this word’s pronunciation changed some two centuries ago is anybody’s guess.

Above, troth turned up in a list of words with the diphthong [ou]. This noun has the suffix –th, as in length, breadth, width. The related verb is trow, now archaic (I trow “I believe, I suppose”). Its pronunciation vacillated for quite some time, so that the word rhymed alternately with now and with no. In the rare cases in which troth still occurs, it rhymes with oath. Sloth has a similar history; it is, naturally, akin to slow. Dictionaries compiled around the middle of the twentieth century were unanimous: British sloth rhymes with oath, American sloth rhymes with cloth (if pronounced with a short vowel). Though all the modern sources give two variants for the American word, it seems that one of them predominates. Troth and sloth should have been spelled trowth and slowth, but who expects logic in this business?

This is a sewer, a proper image for modern English spelling.

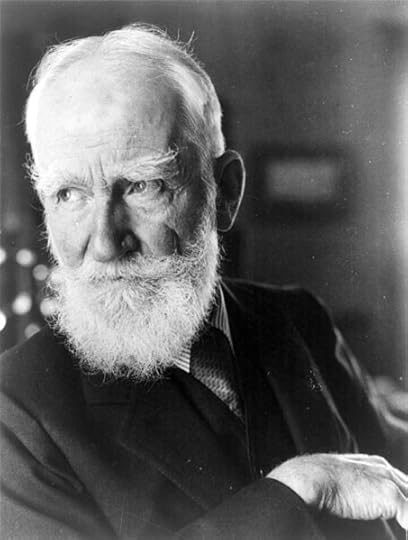

This is a sewer, a proper image for modern English spelling.Many of us must have seen the spelling shew for show. George B. Shaw, for instance, used only the variant shew, and so did Skeat. I have no idea how they pronounced this word. Perhaps an explanation is in order. The Old English verb scēawian belonged to the class in which stress alternated between ē and the following vowel, so that scéawian coexisted with sceáwian. One variant yielded shew (still common in British dialects), while the other became show. The variant shew is misleading for most speakers of Standard English (if such a variety of English exists). Much less common than shew is strow for strew, but then, unlike show, strew goes back to the form with éo. The difference between show and shew is mirrored by the etymological doublets troth and truth. Finally, let us not miss the horror of sew and sewer. Unlike shew, which strikes most as exotic, sew (“to stitch together”) is the only spelling we have, even though it rhymes with sow (the verb sow “to scatter seed,” not the noun sow “female swine”).

We just wanted to shew you a familiar face.

We just wanted to shew you a familiar face.When we look at the Old and Middle English forms of the words, discussed in this post, a reasonable explanation for their spelling usually (not always) emerges, but the picture history handed down to us is frightening: different ways of designating the same vowel and different vowels designated by the same letters or digraphs. Weepers of the world unite!

Image credits: (1) William Tell, Public Domain via Project Gutenberg (2 and Featured image) “Almogrote2” by sao mai, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons (3) “sewer” by Greg Hayter, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr. (4) “George Bernard Shaw” by Davart Company, New York City, USA, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Spelling and knowhow: the oddest English spellings, part 23 appeared first on OUPblog.

Facts about sanitation and wastewater management

After oxygen, fresh, clean water is the most basic requirement for the majority of life on Earth in order to survive. However, this is a true luxury that isn’t accessible for many millions of people around the world.

The importance of properly dealing with wastewater from human endeavours is obvious, as dirty water can contain infectious diseases such as cholera, typhoid, dysentery, trachoma, and others. Today hundreds of thousands of people die every year from these types of waterborne diseases, and even though these numbers are declining there is still work to be done.

Below is a brief introduction on what sanitation is and why it’s important:

Are you interested in learning more about this topic? We’ve discovered some facts that will help to illuminate some of the terms and processes around sanitation and wastewater management, which allows authorities to provide people with access to clean, and safe, water sources.

There are two different types of wastewater – when it has come from domestic baths, kitchens, and laundries it is called gray water, and when the wastewater contains animal, human, or food waste it is referred to as black water.

There are generally two approaches, and two types of technologies, for disposing of these types of waste: the decentralized system and the centralized system.

The decentralized system is where waste is simply deposited in nearby water sources (such as streams or rivers), or dumped in to a cesspit. This system is archaic and not healthy for humans or the environment.

View of the Aquafin waste water treatment plant of Antwerpen-Zuid by Annabel. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

View of the Aquafin waste water treatment plant of Antwerpen-Zuid by Annabel. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia CommonsThe centralized system, which involves the use of self-cleansing sewers, is the safer and healthier option. However it isn’t a modern idea, dating back to around 2,500 BC where a version of it was used in the small cities of the Indus Valley civilization.

Romans are very well known for their sophisticated water supply systems, and by the third century BC they were using three hundred litres of water, per capita, per day, just to use in the baths.

In today’s centralized systems wastewater is placed through a number of processes. The initial, or primary, treatment is where the solids and liquids are separated using screening and sedimentation (the resulting matter is called sludge).

The next, or secondary, treatment is where bacteria are introduced to consume any organic matter that is still in the water.

Then the water is placed through an advanced, or tertiary, treatment using processes that might include adsorption, where activated carbon removes more organic matter.

Oxygen might then be dissolved in to the final water to make sure that the waterbodies (and environments) that receive it have adequate levels of dissolved oxygen.

The waste products from all of these treatment stages are not wasted, in a process called wastewater reclamation. For example, the sludge from the first stage is made available as fertilizer for agricultural use.

Sadly, at a global scale over 2 billion people are without access to improved sanitation, which includes over 1 billion who have no facilities at all.

Featured image credit: black faucet kitchen sink by kaboompics. Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Facts about sanitation and wastewater management appeared first on OUPblog.

A brief history of the European Union [timeline]

Japan and Germany’s surrender in 1945 brings World War Two to an end. Bearing on this, Winston Churchill calls for a “United State of Europe” to bring all the European nations together and called for a creation of a Council of Europe. Since its beginnings after World War Two, the European Union (EU) has grown and evolved over the many years to what it is now: a political and economic union consisting of 28 states that are all located within Europe.

With the United Kingdom’s recent decision of leaving the EU, the future of the European Union and its actions are as timely as ever. In this timeline we have traced a very concise history of the European Union noting key events and economic milestones, from The Spaak Committee to the Eurozone, and leading all the way to Brexit.

Featured image credit: europe flag star european by GregMontani. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post A brief history of the European Union [timeline] appeared first on OUPblog.

Enlightened nation: a look at the Choctaw education system

Peter Pitchlynn, or “The Snapping Turtle,” was a Choctaw chief and, in 1845, the appointed delegate to Washington DC from the Choctaw Nation. Pitchlynn worked diligently to improve the lives of the Choctaw people—a Native American people originally from the southeastern United States. He strongly believed in the importance of education, and served as the superintendent of the Choctaw Academy in 1840.

In the shortened excerpt below, Christina Snyder, author of Great Crossings: Indians, Settlers, and Slaves in the Age of Jackson describes the education system set up by the Choctaw General Council, and its emphasis on equal education opportunities.

On 29 November 1842, ten years after a group of weary emigrants built their first schoolhouse at Wheelock, the Choctaw General Council passed an education bill that would revolutionize Indian schooling. Pitchlynn had returned to Indian Territory triumphant, having rescued Choctaw students from their namesake academy and Choctaw money from Richard Mentor Johnson. Taking control of their education funds, which then amounted to about $28,500 annually, the Choctaw General Council created one of the most extensive public school systems in North America, which would serve over 12,000 Choctaws. New Superintendent of Schools Peter Pitchlynn declared to fellow Choctaws, “In this let us be united; In this let us be ambitious.”

The Choctaws demanded that they should control their own schools. To the General Council, Peter Pitchlynn argued, “The Choctaws now have intelligence enough among them to manage their own institutions without the advice and council of whitemen.” As the first superintendent, Pitchlynn was the ex-officio president of the four-member board of trustees, which included the Choctaws’ federal agent plus one member appointed by each of the three districts. The trustees created policies, set salaries, hired and fired teachers, attended annual examinations, and reviewed all expenses associated with the schools. A separate Building Committee, consisting of members of the General Council, evaluated bids from Choctaw contractors, then oversaw the construction of the new schools. The General Council members who wrote the Schools Act of 1842, mostly graduates of Choctaw Academy, sought to prevent the greed, corruption, and cronyism they saw in the management of their alma matter.

The board of trustees tried, first, to hire Choctaws as teachers and principals, but quickly found that they did not have enough personnel resources to support their planned school system. Peter Pitchlynn waged an uphill battle when he suggested that the Choctaw Nation might turn, once again, to missionaries. Distrust of missionaries was widespread in Indian Territory because many Indians believed that these outsiders had colluded with the federal government to implement removal. Pitchlynn countered by pointing out that only a minority of missionaries had supported removal, while many had defended Indian rights, going so far as to “follo[w] us to our new homes,” where “they have again established churches and schools among us…notwithstanding they have received no aid from our school funds in this country nor from the government of the United States.” Ultimately, the General Council decided to contract out the staffing of several schools, so long as the societies agreed to pay the teachers’ salaries and, more importantly, abide by the regulations set forth in the Schools Act of 1842. The General Council selected several different mission societies—one for each of the selected schools—so that no one society would dominate. Still, Choctaws were wary. Pitchlynn’s cousin Israel Folsom, a fellow member of the General Council, wrote, “Peter, let us be cautious.” Referring to the aftermath of the Panic of 1837, the first US depression, Folsom continued, “Times are hard among the whites and they are aching for the money—we will find a great many are wolves in sheep’s clothing who have bit more often than we.”

“Peter perkins pitchlynn” by George Catlin. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Peter perkins pitchlynn” by George Catlin. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Choctaws took the risk because they wanted to dramatically expand schooling, to create a comprehensive educational system that would serve nearly every member of their nation.

Most Choctaws went to local schools, which came in two varieties. The first, called “neighborhood schools,” ran five days a week, while “weekend schools” served adults and children who worked during the week. Typically located in one-or two-room log cabins, these schools were built by local community members, who petitioned the General Council for funding. Soon, every town and most small villages had local schools, which focused mostly on the basics—reading, writing, and arithmetic—but, unlike white common schools or the new Choctaw academies, the teachers were nearly all Choctaw, and they instructed students mostly in their native language. Lavinia Pitchlynn, Peter’s eldest child, became a schoolteacher, presiding over both neighborhood and weekend schools near their family home at Eagletown. At the neighborhood school, Lavinia’s pupils included her brother Lycurgus and other youngsters bound for the academies as well as local children who would return to their family farms after mastering the basics. Even more diverse were weekend schools. There, 30-year-olds sat next to small children, helping each other through spelling exercises. Because local schools were widespread and offered instruction in Choctaw, they were particularly instrumental in democratizing education.

With their new school system, c. As Israel Folsom argued to fellow members of the General Council, “Our Nation have been mistaken in thinking to improve and civilize the people by educating the boys only.” The “female school,” Folsom argued, “is more necessary for the Nation than the boys—because the girls have been neglected so long.” While the old mission system admitted girls, advanced female students had no opportunity to pursue higher education. The General Council, eager to remedy this mistake, overwhelmingly voted in favor of a resolution to offer girls and women equal access to co- educational neighborhood and weekend schools and to create three female academies, a number equivalent to those for males. In part, the Choctaws were influenced by American notions of republican motherhood. In his conversations with the secretary of war, Peter Pitchlynn echoed US rhetoric regarding education for women: “Intelligent mothers rear up enlightened and intelligent children, they are the first to plant good seed in the minds of the young, and make impressions the most indelible.” Choctaw leaders believed that female education was key to maintaining their status as a “civilized” and “enlightened” nation. But the empowerment of women also resonated with traditional Choctaw values, which helps explain the popularity of female schooling even among cultural conservatives. Since time out of mind, Choctaw women had been heads of household, clan mothers, farmers, political advisers, and bearers of culture. To a matrilineal people, educating women simply made sense.

Featured image credit: “Choctaw Group” by unknown author. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Enlightened nation: a look at the Choctaw education system appeared first on OUPblog.

Tropes vs. autism in Religious Studies

“Why are autistic people different in just the way they are?” asks Uta Frith, a pioneer of autism research. “I put the blame on an absent Self.” Indeed, the absent self theory is the prevailing account of autism among developmental psychologists. Because autistic people lack conscious self-awareness, so the theory goes, they can’t organize their experiences into a meaningful story. They have trouble reflecting on their own intentions and anticipating their own actions. They fail to ascribe mental states to other people. They miss the forest for the trees.

You might think that the sheer number of autie-biographies—autistic-authored personal narratives—would inspire proponents of the absent self theory to reconsider their claim that autistic people lack a sense of self. On the contrary, researchers sustain the theory in the face of such apparent counter-examples by casting doubt on the authenticity of autistic self-expression: if an autistic person shares her memories or describes her feelings, they warn, it might seem like she’s consciously reliving a personal experience (or displaying what they call “episodic” memory), but she’s really just reporting what she’s heard about herself secondhand (or relying on what they call “semantic” memory). Which is to say, she’s “hacking.” In short, the absent self theory “denies autistic agency, denies autistic voice, denies autistic personhood,” to quote Melanie Yergeau, a scholar of rhetoric and an autistic self-advocate. It treats autie-biographers as “the ultimate unreliable narrator.”

But no one has unmediated access to another person’s conscious self-experience. To gather fine-grained information about someone else’s conscious self-experience, then, we typically listen to them speak about themselves, or we read their personal narratives. And in the interest of learning from the speaker/writer, we interpret their statements with a principle of charity. That is, we don’t assume ahead of time that everything they say/write will be an error or a lie, for such an assumption would impede our goal of learning from them.

The trouble with the absent self theory is that it holds water only if we refuse to extend the same principle of charity to an autistic speaker/writer that we would to a non-autistic one. This makes the theory essentially unfalsifiable: evidence that would call the theory into question isn’t allowed to count against it.

What’s more, accepting the unfalsifiable and dehumanizing thesis that autistic self-representation amounts to mere mimicry—rather than an accurate first-person report of the felt character of autistic experience—makes learning from actually autistic people all but impossible. It closes non-autistic people off from a different way of being and knowing, one that “colors every […] thought, emotion, and encounter,” as Jim Sinclair, a founder of the autism-rights movement, puts it. And it thus impoverishes non-autistic people’s perception of the world.

Take the following (imaginary) scenario as an analogy:

Oona and Beth—two women without a language in common—are the only survivors of a plane crash on an uninhabited Pacific atoll. Beth finds Oona’s behavior odd: rather than help Beth search the wreckage for antibiotics or packaged food, Oona paces the shore, staring absently into the forest. “She’s in shock,” Beth thinks. “I can’t rely on her.” Then Oona disappears behind a brightly colored thicket. She returns a short while later with two large orange pine cones (Pandanus fruit), which she breaks into bite-sized pieces, and an armful of pink flowers (firecracker hibiscus), which she arranges into two salad-sized heaps. Oona eats a few flowers and gesticulates at Beth enthusiastically. If, in the face of such countervailing evidence, Beth clings willfully to her belief that Oona is merely in shock, Beth will miss out: Oona, an ethnobotanist, knows the atoll’s edible and medicinal plants.

Now consider the following (all too real) state of affairs:

The absent self theory of autism has obtruded into my multi-disciplinary home field of religious studies. Well-intentioned philosophers, theologians, and anthropologists—scholars who in other respects advocate for disability rights—have taken the theory for granted. Recently, some philosophers of religion have defined faith in a personal god or gods by contrasting it with the supposed inability of autistic persons to attune themselves to other’s mental states. These philosophers have used autism as a trope to explain the difference between “lifeless faith,” or mere (autistic) knowledge, and “living faith,” or heartfelt (non-autistic) devotion. Such accounts define autistic theists out of existence. Theologians, too, have recycled the popular autism-as-living-death trope to how apophatic theology works and to illustrate the “death of the author” thesis. Meanwhile, after interviewing autistic theists, some anthropologists of religion have doubled down on the absent self theory: they wager that autistic theists use the received cultural scripts of their religion to compensate for their lack of a self. In other words, autistic people of faith are merely “hacking.”

What will we miss out on if we cling to the absent self theory?

For one thing, we’ll have a hard time learning from critiques that autistic theists aim at their own faith traditions. Daniel Salomon’s Confessions of an Autistic Theologian is a powerful example. Salomon, a self-described “mystic” who converted from Judaism to Christianity, decries the discrimination he’s faced in “Christian and Jewish groups” that exclude their autistic members from lay leadership and holy orders. In place of ableist theologies that equate autism with postlapsarian brokenness, he constructs an “autistic liberation theology” that sees autism as a “charism.” “We are not ‘others,’” Salomon insists. “We are not ‘curiosities.’ We are not ‘cute childlike characters.’ We are not ‘tragedies.’ We are not ‘marginal cases.’ We are not ‘complicated machines.’ We are full human beings with desires and feelings” and a “spiritually meaningful inner life.”

Featured image credit: Colors, via Andrew John. CC0 Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Tropes vs. autism in Religious Studies appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers