Oxford University Press's Blog, page 387

March 27, 2017

Preparing for the American Society of International Law Annual Meeting of 2017

As the first buds of cherry blossom start to bloom around the Tidal Basin and throughout East Potomac Park in Washington D.C., the international law community prepares to descend on the nation’s capital for the largest annual event in the PIL calendar.

The American Society of International Law’s 111th Annual Meeting will take place in Washington, D.C., at the Hyatt Regency Capitol Hill, from 12 April to 15 April, 2017. Sandra Day O’Connor once observed, “There is no shortage of lawyers in Washington, DC. In fact, there may be more lawyers than people.” With a city motto like Justitia Omnibus (Justice for All), it is a fitting location for a law conference. This year’s theme challenges delegates to consider ‘What International Law Values’, exploring the normative basis of international law and evaluating the success of realizing these goals in practice. Does international law reflect the values of the international community? Do democracy and development have a place as international law values? How do these values affect the practice and theory of international law? Through the panels and events of the 2017 Annual Meeting, leading and emerging voices in international legal scholarship, policy, and practice will attempt to answer these important questions.

To help you get a head start on the panel discussions, Oxford Journals have created a specially curated ASIL conference collection of free articles from across our international law journals, which explore the conference theme.

Those familiar with the conference can attest to the jam-packed schedule, full of more than 40 substantive panel discussions on a wide variety of international law topics, not to mention numerous networking and social events to enjoy. This year’s sessions focus on an extensive assortment of topics from law of the sea, space, and climate change, to use of force, cyberwarfare, human rights, and migration. With a vast array of fascinating panels on offer, and an impressive list of participants there is something for academics, attorneys, judges, and students alike.

Here are some of the program highlights:

Wednesday, 12 April, 2017 2017

Grotius Lecture: Civil War Time: From Grotius to the Global War on Terror (4:30-6:00 p.m.): Join David Armitage, Lloyd C. Blankfein Professor of History, at Harvard University, for this year’s highly anticipated lecture.

Thursday, 13 April, 2017

International Law and the Trump Administration: National & International Security (9:00-10:30 a.m.): This panel brings together leading experts in the field to discuss this hot button topic. In advance of this panel, explore our reading list of 10 Questions of International and Constitutional Law and the Trump Administration.

Reddit IAmA…with David Armitage (10:00 a.m. -11:00 a.m.): Join Oxford University Press and author, historian, and keynote speaker David Armitage for an online question and answer (or AMA) through Reddit.

TPP, BREXIT, and After (11:00-12:30 p.m.): This highly topical panel explores the uneasy future of deep economic agreements in the wake of Brexit. Check out our Brexit Debate Map, to learn more about the legal consequences of the Brexit.

Under Pressure: The Global Refugee Crisis and International Law (11:00-12:30 p.m.): Syria’s civil war has created the worst humanitarian crisis of our time, but how do we determine who is a refugee? Furthermore, what rights do refugees have under international law? This panel aims to delve into these important and difficult issues. Explore our resources on refugee law, for expert analysis on the essential questions.

Foreign Affairs Federalism: A Comparative Perspective (3:00-4:30 p.m.): This panel brings together world experts, to explore the power divide between national and sub-national governments and discuss the unique challenges in international obligations and compliance. Panelist David L. Sloss, winner of the ASIL 2017 Certificate of Merit in Creative Scholarship joins the debate. Why not check out a chapter of his award-winning book.

ASIL Annual Assembly (4:45p.m.-6:30 p.m.): Remarks from the ASIL President, and the presentation of the Deák Prize! Friday, April 14, 2017 International Law and the Trump Administration: International Trade (9:00-10:30 a.m.): This timely discussion will tackle the new administration’s approach to international trade, and the role that international law plays in current events.

Friday, 14 April, 2017

International Law and the Trump Administration: International Trade (9:00-10:30 a.m.): This timely discussion will tackle the new administration’s approach to international trade, and the role that international law plays in current events.

The Regime of Islands in the Aftermath of the South China Sea Arbitration (9:00-10:30 a.m.): On July 12, 2016 the PCA ruled in favor of the Philippines in this landmark case. However, the court would not “rule on any question of sovereignty over land territory and would not delimit any maritime boundary between the Parties“. Both China and Taiwan have rejected the ruling. What does this mean for islands in region, and the future of territory disputes globally? For more in the subject, take a look at our “Disputes in the South and East China Seas Debate Map”.

Claims against the U.N.: From Within and Without (9:00-10:30 a.m.): Simon Chesterman, National University of Singapore Faculty of Law, and Patricia Galvao-Teles, United Nations International Law Commission explore questions relating to the UN’s accountability, its privileges and immunities, and how it responds to claims brought against it. Examine some high-profile UN failures and abuses, by reading this chapter on Accountability in Practice.

Should the International Criminal Court Privilege Global or Local Justice Goals? (11:00-12:30 p.m.): What should take precedent, local values or global vision? This exciting panel discusses the justice goals and global limitations of the ICC.

The Value(s) of International Dispute Resolution (11:00-12:30 p.m.): Yuval Shany, Hebrew University of Jerusalem Faculty of Law and a host of experts discuss the values of international courts. This panel looks at historical and current practices across international courts to identify and analyze the normative values these courts represent and advance. For related reading, here is Yuval Shany’s chapter on The Goals of International Courts.

Fifth Annual Charles N. Brower Lecture on International Dispute Resolution (3:00-4:30 p.m.): Join David Caron, Professor of International Law at King’s College London, and Judge with the Iran – US Claims Tribunal in The Hague, for expert insight on all things ADR. Read his chapter on Regulating Opacity to learn more about the issue of transparency in international arbitration.

Keynote Address (5:00-6:30 p.m.): Do not miss this year’s keynote speaker Sandie Okoro, Senior Vice President and General Counsel of the World Bank Group.

Saturday, 15 April, 2017

Valuing Women in International Adjudication (9:00-10:30 a.m.): To what extent does international law value the participation of women in international adjudication? Are women equally represented on the benches of the world’s international courts? Learn how women are shattering the glass ceiling and what more needs to be done for women’s equality in the international legal arena.

If you are wondering what to do when you are not attending sessions, you can check out these local offerings:

Visit the America’s Presidents exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, for a chance to view the nation’s only complete collection of presidential portraits outside the White House. Also, don’t miss Nelson Shanks’s The Four Justices, a tribute to the four female justices who have served on the U.S. Supreme Court.

Visit the Smithsonian’s National Zoo’s most famous residents, giant pandas Tian Tian, Mei Xiang, Bao Bao, and baby cub Bei Bei. Online visitors can catch a glimpse on the Panda Cam.

National Cherry Blossom Festival Parade – Saturday, 8 April Nothing epitomizes spring like cherry blossom. If you happen to be in town early, this world-renowned annual festival is worth checking out.

Southwest Waterfront Fireworks Festival – Saturday, 15 April The perfect way to end your ASIL experience. While there will be many vantage points, the Waterfront Park is an ideal location to take in this show stopping spectacular.

Feeling hungry? Head over to Union Market, the epicenter of culinary creativity in D.C., with over 40 local vendors and much more.

Need a reason return? A new exhibition at the Library of Congress, “Drawing Justice: The Art of Courtroom Illustrations,” will feature original art that captures the drama of high-profile court cases in the last 50 years. Opens 27 April through 28 October, 2017.

If you are lucky enough to be joining us in D.C., don’t forget to visit the Oxford University Press booth, where you can browse our award-winning books, and take advantage of the 25% conference discount. Stop by to enter our prize draw for a chance to win $150 worth of OUP books, pick up a free access password to our collection of online law resources, and browse our international law journals. If you’re feeling interactive, we will have speech bubbles for attendees to fill with their international law values to post online with #MyInternationalLawValuesAre.

To follow the latest updates about the 111th ASIL Annual Meeting as it happens, follow us on Twitter @OUPIntLaw, and on Facebook, using the conference hashtag #ASILAM.

We look forward to seeing you in D.C.!

Featured image credit: “White House”, by tpsdave. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Preparing for the American Society of International Law Annual Meeting of 2017 appeared first on OUPblog.

March 26, 2017

Is privacy the price of precision medicine?

Personalized medicine promises much. New initiatives aim to harness technology and genomics to create bespoke medicine, customizing your healthcare like your Facebook profile. Instead of relying on generic practice guidelines, your doctors may one day use these new analytic tools to find the ideal treatment for you. Big data will make this precision possible: patterns that emerge from the DNA and medical records of millions can predict which treatments work best for which patients. Fewer mistakes, lower costs, and more effective care may result.

But this precision has a price that science and medicine don’t acknowledge. Personalized medicine demands that we all contribute our medical histories and genomes to the big data research pool. The science works only if the numbers are very large; so large that some envision every patient as a subject whose medical data will be shared for research. As this future unfolds, you will, of course, be assured of your privacy. Unfortunately, that’s a promise science cannot honestly make and you should not believe.

A growing number of experts, particularly re-identification scientists, believe it simply isn’t possible to de-identify the genomic data and medical information needed for precision medicine. To be useful, such information can’t be modified or stripped of identifiers to the point where there’s no real risk that the data could be linked back to a patient.

This realization is colliding with research norms that permit the relatively free exchange of patients’ medical information. Research and medical privacy regulations, as currently interpreted, allow review boards to waive patient consent, and even allow researchers to call DNA sequences “de-identified,” data, a category without oversight or privacy protection. Newly-announced changes to federal research regulations simply broaden the scope of these practices.

Is your genome being shared for research? It’s impossible to know for sure. In some states, doctors need your consent to test your blood for your medical care, but it is perfectly legal for a researcher to obtain blood no longer needed for your care, then sequence your genome and place your information in a research database, all without your consent or even your knowledge. Federal medical privacy and research laws permit this on the misguided assumption that there’s no re-identification risk.

Regulators have been slow to acknowledge re-identification risks, though it is known that genome sequences might be re-identified through comparison to a database of identified genomes (such as those held by law enforcement consumer genetic testing companies), through the use of demographic information provided along with the sequence data, or even, potentially, through new technologies that may enable prediction of an individual’s face from genomic data.

Technology by Medill DC. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

Technology by Medill DC. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.Security is essential to protect privacy, yet few specific regulatory standards protect the security of the sensitive health data needed for precision medicine research. What exists is outdated and insufficient. For example, while your fingerprint, long known to be useful for re-identification, was protected under the 2003 federal HIPAA Privacy and Security rules as a “biometric identifier,” your genome was not—and today, 14 years and millions of genotypes later, still is not.

Millions of Americans have seen their medical data compromised by cyberattacks on data stored at hospitals, insurers, and clinical laboratories. Electronic health records (EHRs) are favorite targets; once these records link to the genomic data needed for precision medicine, the privacy impact of cyberattacks will increase exponentially. Unlike a medical record number or credit card number, genome sequences, unique and permanent, can’t be replaced when compromised, and sequence data are a wellspring of information about health risks, ancestry, and sometimes, unexpected parenthood.

Databases containing genomes and medical histories are multiplying, sometimes populated with the data of unwitting participants who don’t know researchers have sequenced their genomes and placed the data in research databases operated by public entities (such as the NIH) or private drug companies. Data from these databases is shared with researchers world-wide, typically under a “data use agreement” that offers no recourse to data subjects if their information is misused or compromised.

We became interested in this issue when we realized that the biggest database of all – the increasingly networked EHRs of hospitals and physician practices nationwide – might one day include genomic data from everyone, as gene sequencing becomes common in healthcare.

Typically patients aren’t notified when their medical records are shared for research, or with whom. An increase in funding for biomedical data research has grown the number of studies obtaining EHR data on a large scale; almost always, these studies are conducted without informed consent. And researchers aren’t held to specific, uniform legal requirements for protecting the security of genomic and health data they receive for research.

This isn’t right. Researchers should never lead participants to believe that no one could re-identify their genomic data – re-identification is always a risk. Patients should always know who is receiving their genomes and medical records for research, so they can demand better security oversight of the privacy risks.

Ethical guidelines for research, including data research, stress the importance of respect for persons. Informed patients are respected persons who can help hold researchers accountable for data security. Better security is possible—for example, researchers are exploring new techniques to encrypt genomes without making them useless for research— but if patients remain unaware and regulators are reluctant to question the status quo, they’ll be few incentives for improvement. Unless we raise the bar on research data security, however, patients, though they may benefit from better care, will assume unreasonable and unnecessary privacy risks as their data is shared in the pursuit of precision medicine.

Featured image credit: Security by TheDigitalWay. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Is privacy the price of precision medicine? appeared first on OUPblog.

Falling in love with the national security state

Romantic comedies help me get through long international flights. On a recent trip to Hong Kong, however, I decided to take a risk by departing from my standard viewing practice to watch Oliver Stone’s Snowden, a political thriller about the whistleblower who pulled back the curtain of the surveillance state by exposing how the NSA threatens the privacy of just about everyone. Would this movie set me on edge, making me fearful and paranoid for the remainder of the flight?

I need not have worried at all, since the film is essentially shot as a love story. To the extent that Snowden is a romance, it mistakes the true nature of surveillance and intelligence gathering by representing matters of national security as affairs of the heart.

The pivotal issue of Snowden is not whether the NSA is scooping up phone records. The audience already knows that story from the headlines that grabbed international attention in 2013 and 2014. Instead, the question raised by Stone’s script is whether a shy young man with off-the-charts computing skills will disclose his most private feelings to the free-spirited woman who enters his life. The true revelations are not about illegal government surveillance but the surprising charms of Joseph Gordon-Levitt, who, in all his nerdy vulnerability, plays the private security contractor who leaked the secrets of the NSA.

Will Joseph end up with Shailene Woodley, his love interest in the film? Will Shailene learn to trust a man who possesses and is possessed by so many secrets that he can’t really open up, either emotionally or practically, in the way women in movies today expect? (If using the actors’ first names seems catty, it’s rather that each is so personable and friendly.)

By the time that the real Edward Snowden makes a cameo in the film, his appearance seems gratuitous, since the script has already suggested that the drama transpiring between Joseph and Shailene is far more interesting and significant than anything happening between the national security state and its citizens.

For the economy-class traveler, trapped on a 14-hour flight across the international dateline, Snowden comes tantalizing close to a satisfying experience. Were it not for Snowden’s cameo in the final scenes, one might readily enjoy the film as the romantic comedy it was never meant to be.

Nonetheless, Joseph and Shailene’s characters are clearly meant to be together. The only thing standing in their way is the NSA. A close-up shot of a laptop camera, innocently left open in the bedroom, implies that the US government is getting its jollies by snooping on moments of private intimacy. Where Darcy and Elizabeth in Pride and Prejudice only had to contend with the hauteur of Lady Catherine de Bourgh, the romantic couple in Snowden has to withstand the invasion of privacy perpetrated by shadowy, but all-powerful government agencies.

In the end, then, it is not love but the right to privacy that conquers all. At this level, our telegenic lovers fade into the background and the true hero emerges: the Fourth Amendment to the US Constitution, which guarantees people the right to be secure in their “houses, papers, and effects,” and, we might add, their e-mails, web searches, and viewing habits. This emphasis upon privacy centers on single entities, not collective ones, which is perfectly consistent with the reliance on a single individual—Snowden—to encapsulate a complex set of issues involving national security and surveillance.

Ordinarily, entertainment allows us to take pleasure in the subject of a biopic who stands in for events of broad historical significance. Surely, Stone has had success with Nixon, JFK, and The Doors in commenting on American history by focusing on individuals who are both representative of and exceptional to their eras. But the electronic eavesdropping of all phone calls, or the ability record the subjects of all web searches, are hardly ordinary.

National security at this level entails the compilation and storage of aggregate data. No one is specifically targeted because under mass surveillance everyone is already suspected.

When it comes to understanding the intricacies of national security, a romance about two people can be seductive. It allows us to enjoy the feeling that the big, bad security state, with its unimaginable capacity to intrude on our most private moments, is the principal villain that individual citizens like us face. Equally, if not more concerning, is that surveillance and security depend on indiscriminate power– that is, power that does not discriminate among individuals but instead, in the words of the NSA mandate, endeavors to “collect it all.”

Featured image credit: Snowden © Open Road Films. Used with permission from Open Road Films.

The post Falling in love with the national security state appeared first on OUPblog.

His shadow, her doubt: The feminine versus the queer in Hitchcock

Alfred Hitchcock’s films foreground a conflict that I call “the feminine versus the queer.” The heterosexual heroine, fighting for love and often for her own survival, finds a surprising rival in a queer character, who simultaneously understands and thwarts her. (see Figures 1 and 2)

Figure 1. Bruno Anthony stalks the unsuspecting Miriam in Strangers on a Train.

Figure 1. Bruno Anthony stalks the unsuspecting Miriam in Strangers on a Train. Figure 2: The heroine Eve Kendall cries out when she sees the villainous henchman Leonard in North by Northwest.

Figure 2: The heroine Eve Kendall cries out when she sees the villainous henchman Leonard in North by Northwest.Hitchcock’s American career commences with Rebecca (1940), which features a near-explicit lesbian character, Mrs. Danvers (Judith Anderson), the head housekeeper of Manderley, the stately home of Maxim de Winter (Laurence Olivier). Danvers torments the fragile, awkward heroine, the second Mrs. de Winter (Joan Fontaine) in several sadomasochistic scenes. Scholars such as Patricia White, Rhonda Bernstein, and Tania Modleski have eloquently explored their sexual significance. (see Figure 3)

Figure 3: “Why don’t you?” Mrs. Danvers tempts the heroine, with death and desire.

Figure 3: “Why don’t you?” Mrs. Danvers tempts the heroine, with death and desire.Mrs. Danvers remains closely allied to the first Mrs. de Winter, the now-dead Rebecca, who perished in a suspect seafaring accident yet still wields considerable power over the sprawling English mansion. The second Mrs. de Winter wanders about the vast patriarchal home, dwarfed by looming door-frames and adrift in enormous rooms. Every room seems to contain physical remnants of her predecessor, such as the stationary and pillowcases emblazoned with the bold majuscule “R.” The dead woman carves her initial on the heroine’s psyche, imprints her artistic signature on Hitchcock’s authorship.

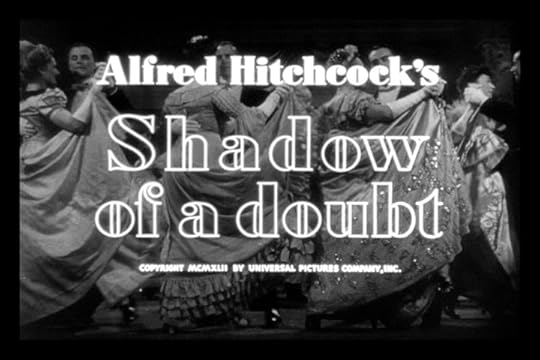

Lesbian threat is an important dimension of Hitchcock’s work—see especially Stage Fright (1950), The Birds (1963), and Marnie (1964). The feminine/queer conflict will most often occur, however, between the woman and a queer male. Films such as Shadow of a Doubt (1943), Spellbound (1943), Notorious (1946), Rope (1948), Strangers on a Train (1951), The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956), North by Northwest (1959), and Psycho (1960) exemplify this intimate crisis. (see Figure 4)

Figure 4: Sparks fly between Marlene Dietrich and Jane Wyman’s women in Stage Fright.

Figure 4: Sparks fly between Marlene Dietrich and Jane Wyman’s women in Stage Fright.Shadow of a Doubt depicts the feminine versus the queer as a fatal struggle between the heroine and her sexually ambiguous uncle. This suspense film, as so many of Hitchcock’s most significant do, intersects with the woman’s film genre that had its heyday from the 1930s to the 1950s. In woman’s film fashion, anxieties over the singular heroine’s romantic future loom. While the film does, if rather wanly, offer the possibility of a romance for her with Jack Graham (Macdonald Carey), one of the detectives on her uncle’s trail, the focus is much more intently placed on Charlie’s maturation. It’s a dark coming of age; her exposure to Charles’ evil and the discovery of her own potential for retributive wrath change her indelibly. (see Figure 5)

Figure 5: The opening credits ironize the image of happy heterosexual couples

Figure 5: The opening credits ironize the image of happy heterosexual couplesCharlie, luminously played by Teresa Wright, longs for excitement, the precondition for the arrival of chaos in the Hitchcock film (The Lady Vanishes, Rear Window, Psycho, The Birds). Charlie abhors the conformity of her small-town life. For this reason, she is overjoyed to hear that her dapper, well-traveled Uncle Charlie (Joseph Cotten, in his finest performance), is coming to visit. Little does Charlie or her family suspect that Charles is a serial killer known as “The Merry Widow Killer,” given his murders of rich widows. (see Figure 6)

Figure 6: Dark doubles: Charlie and her uncle Charles in the ‘Til Two bar.

Figure 6: Dark doubles: Charlie and her uncle Charles in the ‘Til Two bar.A brief montage introduces somnolent Santa Rosa, California, where the restless Charlie lives with her much-loved but frustrating family. We are shown a series of attractive sun-dappled house fronts. But their thin veneer of normalcy has an ominous air, given the unmasked Charles’s confrontational line to Charlie: “Do you know if you ripped the fronts off houses, you’d find swine?”

Hitchcock uses visual parallels between uncle and niece to convey emotional ones. Eager for change, Charlie rejects her father’s comforting words as she lies brooding on her bed. Charles, when introduced, lies pensively in the same position on a bed in a boarding house as a motherly landlady speaks to him. Suddenly, Charlie gets the idea to go to the Telegraphy office to ask Uncle Charlie to visit them; once there, she discovers that he has sent a telegraph to her and her family announcing his imminent visit! The pattern of doubling continues throughout, reinforcing the idea that Charlie and her uncle remain closely linked even when her role as his comeuppance emerges.

It is significant that the image of the proto-married couple in the closing moments—Charlie and Graham standing in front of the church as Charles’ funeral mass occurs inside—is inextricable from death and fallen knowledge. The hollow words of praise for the dead killer, heard only as sincere eulogies by the unsuspecting crowd, painfully contrast with Charlie’s somber reflections about her uncle’s philosophy: “He thought the world was a horrible place. He couldn’t have been very happy, ever. He didn’t trust people. Seemed to hate them. He hated the whole world. You know, he said people like us had no idea what the world was really like.”

The heterosexual couple is haunted by the specter of a threatening queerness that has been ambiguously reincorporated into the normative social order. Charlie comes of age when she defends herself against her uncle’s murderous advances, pushing him off the train before he can do the same to her. Sexual doppelgangers, the heroine, standing apart from unsuspecting society, and the socially inassimilable queer male double one another, giving resonance to the idea that one’s double augurs one’s death. Shadow of a Doubt prefigures Psycho, a film that takes the feminine versus the queer conflict to a new level of murderous intensity.

Image credits: (1) “Strangers on a Train – Bruno in line” Directed by Alfred Hitchcock, distributed by Warner Bros., Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (2) “North by Northwest movie trailer screenshot” Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (3) “Rebecca trailer” Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (4) “Marlene Dietrich Stage Fright Trailer” Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (5) “Shadow of a Doubt (1943)” CC BY-SA 2.0, via Flickr. (6) “Teresa Wright and Joseph Cotten in Shadow of a Doubt trailer” Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. Featured image credit: “Multiple exposure of Alfred Hitchcock 1942” by user kristine. CC by 2.0 via Pixabay.

The post His shadow, her doubt: The feminine versus the queer in Hitchcock appeared first on OUPblog.

J. L. Austin, “Other Minds,” and the goldfinch

J. L. Austin was born on 26 March 1911. He was twenty-eight when the Second World War began, and served in the British Intelligence Corps. It has been said by G. Warnock that, “he more than anybody was responsible for the life-saving accuracy of the D-Day intelligence”. He was honoured for his intelligence work with an Order of the British Empire, the French Croix de Guerre, and the U.S. Officer of the Legion of Merit.

Austin returned from service with the conviction that philosophy might be organised so as to replicate the successes of the Intelligence Corps. He hoped that if philosophers focused on specific examples, and the precise, but ordinary, characterisation of those examples, then they might work together to furnish philosophy with a set of agreed starting points. The first fruits of this model of philosophical activity were the reflections on knowledge contained in Austin’s essay, “Other Minds.”

The essay comprises a wealth of observations on our ordinary play with the notion of knowledge, together with attempts to connect those observations with the higher-falutin concerns of traditional philosophy. Austin invites us to consider our ordinary ways of treating someone’s claim that a goldfinch is nearby. Typically, we will accept their claim to know only if they are able to provide an appropriate answer to the question, “How do you know?” and we will sometimes challenge the adequacy of their particular answers, If you have asked, “How do you know it’s a goldfinch?” then I may reply “From its behaviour,” “By its markings,” or, in more detail, “By its red head,” “From its eating thistles” You may object, “But that’s not enough. Plenty of other birds have red heads.”

Philosophy takes flight by iterating such challenges. The upward path leads to questions about how one knows that seeing is a way of knowing, that one isn’t dreaming, and so forth. We become breathless, unable to answer. Philosophers have taken such incapacity to suggest that we don’t know. Austin argues that our ordinary practice doesn’t support the philosopher’s ascent: “(b) Enough is enough: it doesn’t mean everything. Enough means enough to show that (within reason, and for presents intents and purposes) it ‘can’t’ be anything else, there is no room for an alternative, competing, description of it. It does not mean, e.g., enough to show it isn’t a stuffed goldfinch.”

Austin’s thought is that although someone who claims to know that there is a goldfinch should be able to say something about how they know, they needn’t be able to rule out every imaginable alternative. Let’s consider Austin’s thought more closely.

Austin focuses on a case in which we accept:

I. You know that there’s a goldfinch.

He allows that our practice of asking how someone knows supports:

II. If you know that there’s a goldfinch, then you can show that there’s a goldfinch.

And he thinks that one can meet that requirement, even though one can’t meet others:

III. You can’t show that what’s there isn’t stuffed.

It’s at this point that the traditional philosopher seizes their chance. They will point out that parity with II supports IV:

IV. If you know that what’s there isn’t stuffed, then you can show that what’s there isn’t stuffed.

And III and IV then entail V:

V. You don’t know that what’s there isn’t stuffed.

The Thinker by Auguste Rodin. Picture by Frank Kovalchek, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The Thinker by Auguste Rodin. Picture by Frank Kovalchek, CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.But the philosopher then notes that:

VI. You know that if there’s a goldfinch, then what’s there isn’t stuffed.

But one can exploit that knowledge in order competently to deduce, and so come to know, further conclusions:

VII. If you know that there’s a goldfinch, and you know that if there’s a goldfinch, then what’s there isn’t stuffed, then you can competently deduce, and so come to know, that what’s there isn’t stuffed.

Thus, given I, VI, and VII:

VIII. You know that what’s there isn’t stuffed.

But V contradicts VIII. At least one of the claims must be rejected.

Austin isn’t explicit about which of these claims he rejects, and the question is contested. One suggestion is that Austin would reject VII: although deduction is often a way of extending knowledge, perhaps it isn’t in this case. An alternative is that Austin invites us to reconsider the general claim that if you know, you can show. I, VI, and VII indicate a way in which one can use knowledge that there’s a goldfinch in order to know that what’s there isn’t stuffed. Ostensibly, one might use such considerations in order to show that what’s there isn’t stuffed. But that suggests that Austin has something more specific in mind in denying that one can show that what’s there isn’t stuffed. Perhaps what he has in mind is that one can’t show that in a way that doesn’t beg the question, by presupposing that there is a goldfinch — something that, by nature, isn’t stuffed. Austin’s proposal would be that it isn’t invariably true that someone who knows that such-and-such can show that such-and-such in a way that doesn’t presuppose that such-and-such.

Although it’s hard to be sure what precisely Austin took to be the consequences of his reflections for traditional philosophy, we can begin to see how there might be such consequences. Austin sought to bring very general philosophical claims into contact with the more secure array of data provided by our ordinary judgments about specific cases. His hope was that philosophers working together on the collection and analysis of such data might achieve the same sort of progress as his wartime intelligence operations.

Featured Image credit: A European goldfinch sits on a fence in Sardinia, Italy. Francesco Canu, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post J. L. Austin, “Other Minds,” and the goldfinch appeared first on OUPblog.

March 25, 2017

For want of a comma

The Oxford Comma, so named because it first appeared in the 1905 Oxford University Press Style Guide, is the comma that comes before the word and in a series of three or more listed items. Also known as the serial comma, it’s the often ironic rallying cry of a certain type of language aficionado. And it’s in the news after a federal appeals court mentioned it in a court decision recently.

The court case was O’Connor v. Oakhurst Dairy, a lawsuit filed by truck drivers seeking overtime pay that they had been denied under a Maine law. Maine labor law requires time-and-a-half for overtime, but makes some exceptions, specifically for workers involved in:

The canning, processing, preserving, freezing, drying, marketing, storing, packing for shipment or distribution of:

(1) Agricultural produce;

(2) Meat and fish products; and

(3) Perishable foods.

“Oakhurst Dairy, Portland Maine” by John Phelan. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“Oakhurst Dairy, Portland Maine” by John Phelan. CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Here is the question. Were the truckers at the dairy involved in compound task of “packing for distribution or shipping” of perishable goods. Or were they just involved in “the distribution” of perishable goods.

Since the truck drivers don’t actually pack the goods, one could argue that the exemption doesn’t apply to them, only to workers who do “packing for shipment and distribution” of perishable foods. But under the other interpretation, where distribution is a separate serial item, the truckers would be exempt since they are involved in distribution.

The judges opened their opinion by noting that “For want of a comma, we have this case.” The overtime pay—for 75 workers over four years by the way—came to a $10 million, so this was an expensive comma.

But while the serial comma may have captured the attention of the media and the Oxford Comma fans, the decision was not just about punctuation. The judges noted that the Maine Legislative Drafting Manual say “when drafting Maine law or rules, don’t use a comma between the penultimate and the last item of a series,” though elsewhere the manual warns against ambiguous lists. Maybe the writers of the law should have used a comma, and maybe not.

With that in mind, the judges looked at a wide range of language issues: parallelism, the semantics of the words distribution and shipping, the lack of an and before packing. In the end, they found merit in both the arguments of the drivers and the dairy. The judges concluded that “The text has, to be candid, not gotten us very far.” A comma would have broken the tie.

In the end, the judges decided the case based on a precedent that laws match their purposes together with public policy goals of the state. The truck drivers got paid, and we have a tale of the Oxford comma, law and grammar.

Featured image credit: “Oxford snow scene” by Jun. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post For want of a comma appeared first on OUPblog.

What is social justice?

Using a social justice lens helps organizations to reframe issues generally viewed as individual in origin to include broader social, political, economic, and cultural understandings. In the following excerpt from the Encyclopedia of Social Work, Janet L. Finn and Maxine Jacobson explore the meanings and principles of social justice—a term which at times can be rather elusive and unclear in its applications.

How do those individuals, whose work is centrally guided by the values of social justice, think about the concept? How does Western philosophy and political theory influence our understandings of social justice?

The meanings of social justice are far reaching and ambiguous; translation into concrete practice is fraught with challenges. Social justice is a contextually bound and historically driven concept. Political theorists, philosophers, and social workers alike have explored what it means to be in the “right relationship” between and among persons, communities, states, and nations. As researcher Patrick McCormick has said, “There is not even agreement about whether liberty, equality, solidarity or the common good is the primary cornerstone on which the edifice of justice is to be constructed.”

Understandings of social justice in US social work are largely derived from Western philosophy and political theory and Judeo-Christian religious tradition. Conceptions of justice are abstract ideals that overlap with beliefs about what is right, good, desirable, and moral. Notions of social justice generally embrace values such as the equal worth of all citizens, their equal right to meet their basic needs, the need to spread opportunity and life chances as widely as possible, and finally, the requirement that we reduce and, where possible, eliminate unjustified inequalities. As Caputo (2002) remarks, the concept of social justice invoked by social work has largely been one steeped in liberalism, which may serve to maintain the status quo. However, Caputo also contends that social justice remains relevant as a value and goal of social work.

Some students of social justice consider its meaning in terms of the tensions between individual liberty and common social good, arguing that social justice is promoted to the degree that we can promote collective good without infringing upon basic individual freedoms. Some argue that social justice reflects a concept of fairness in the assignment of fundamental rights and duties, economic opportunities, and social conditions.

“Some argue that social justice reflects a concept of fairness in the assignment of fundamental rights and duties, economic opportunities, and social conditions.”

Others frame the concept in terms of three components—legal justice, which is concerned with what people owe society; commutative justice, which addresses what people owe each other; and distributive justice, or what society owes the person. From a distributive perspective, the one most often referenced by social workers, social justice entails not only approaches to societal choices regarding the distribution of goods and resources, but also consideration of the structuring of societal institutions to guarantee human rights and dignity and ensure opportunities for free and meaningful social participation.

Discussions of social justice in the context of social work generally address the differing philosophical approaches used to inform societal decisions about the distribution or allocation of resources. These discussions refer to three dominant theories of resource distribution: Utilitarian, libertarian, and egalitarian.

Utilitarian theories emphasize actions that bring about the greatest good and least harm for the greatest number. From this perspective, individual rights can be infringed upon if doing so helps meet the interests and needs of the majority.

Libertarian theories reject obligations for equal and equitable distribution of resources, contending instead that each individual is entitled to any and all resources that he or she has legally acquired. They emphasize individual autonomy and the fundamental right to choose; they seek to protect individual freedom from encroachment by others. Proponents support minimal state responsibility for protecting the security of individuals pursuing their own separate interests.

Egalitarian theories contend that every member of society should be guaranteed the same rights, opportunities, and access to goods and resources. From this theoretical perspective the redistribution of societal resources should be to the advantage of the most vulnerable members of society. Thus, redistribution is a moral imperative to ensure that unmet needs are redressed (Rawls, 1971). However, as researcher Elisabeth Reichert notes, the idea of social justice, expressed variously in these theories, remains elusive, especially in terms of concrete applicability to practice.

A number of social workers concerned about questions of social justice have turned to the work of the political philosopher John Rawls, whose theory of justice is grounded in the egalitarian approach addressed above.

Drawing from liberal thought, Rawls critiqued utilitarian and libertarian conceptualizations of social justice for their justification of personal hardships in lieu of a greater common good. Rawls’ theory asks, what would be the characteristics of a just society in which basic human needs are met, unnecessary stress is reduced, the competence of each person is maximized, and threats to well-being are minimized? For Rawls, distributive justice denotes “the value of each person getting a fair share of the benefits and burdens resulting from social cooperation,” both in terms of material goods and services and also in terms of nonmaterial social goods, such as opportunity and power.

In Justice as Fairness: A Restatement, Rawls provides two basic principles of social justice, modified from his earlier work:

Each person has the same indefeasible claim to a fully adequate scheme of equal basic liberties, which scheme is compatible with the same scheme of liberties for all; and

Social and economic inequalities are to satisfy two conditions: First, they are to be attached to offices and positions open to all under conditions of fair equality of opportunity, and second, they are to be to the greatest benefit of the least-advantaged members of society (the difference principle).

Jerome Wakefield (1988) argues that Rawls’ notion of distributive justice is the organizing value of social work. He proposes that a Rawlsian perspective helps social work integrate its micro and macro practice divide and that it contains “the power to make sense of the social work profession and its disparate activities.” Michael Reisch draws on Rawls’ principle of “redress,” that is, to compensate for inequalities and to shift the balance of contingencies in the direction of equality. He argues that a social justice framework for social work and social welfare policy would “hold the most vulnerable populations harmless in the distribution of societal resources, particularly when those resources are finite. Unequal distribution of resources would be justified only if it served to advance the least advantaged groups in the community” (Reisch, 1998).

Featured image credit: “‘Equal rights for all, special privileges for none’ Thomas Jefferson” by Kate Ter Haar. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post What is social justice? appeared first on OUPblog.

March 24, 2017

America’s relationship with alcohol [Timeline]

Alcohol has been present in the United States since before it became a country. In that time, the people’s relationship with the substance has been multifaceted. From local watering holes marking the stirring of resistance against the British Empire, to the rise of speakeasies during Prohibition, to the proliferation of American cocktails abroad, alcohol is as much a part of American history as the stars and stripes. And the relationship has not always been an easy one.

Toasting became illegal in Massachusetts in 1663, temperance groups advocated against its consumption, and anarchy was associated with alcohol after the assassination of President McKinley. The debate around Americans and booze continues to this day. The “stroller bans” from 2008 sparked conversations around the place of parents and their children in bars. The debate isn’t over, and the United States’ relationship with alcohol is sure to continue to change in the coming centuries.

Featured image credit: “Beer” by Martin Garrido. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post America’s relationship with alcohol [Timeline] appeared first on OUPblog.

Mitochondrial replacement techniques and Mexico

The birth of the the first child after a mitochondrial replacement technique has raised questions about the legality of such procedure. In this post we explore some of the legal issues surrounding this case.

Mitochondria are cellular organelles that generate the energy cells need to work properly. Two interesting features of mitochondria are that they are solely inherited via the maternal line and that they possess their own DNA. This means that in human cells there is the nuclear DNA and mitochondrial DNA. Mitochondrial DNA, with its 37 genes, accounts for 0.1% of the total human DNA. Disorders caused by mitochondria not working properly have been named ‘mitochondrial diseases’. Mitochondrial diseases, as stated by the Nuffield Council on Bioethics, “can be caused by either problems in the genes in the nucleus affecting mitochondrial function, or by problems in genes within the mitochondria themselves”.

Scientists have recently devised two techniques that would allow women affected by mitochondrial DNA diseases to have genetically related children free from disease. These techniques have been called mitochondrial replacement technique (MRTs), although some object to this name. Both techniques consist in rehousing the intending parent(s)’s nuclear DNA into a previously enucleated cell that has healthy mitochondria. In one of the techniques, Maternal Spindle Transfer (MST), the nuclear DNA that is rehoused is that of an unfertilised egg. In the other technique, Pronuclear Transfer (PNT), the nuclear DNA that is rehoused is that of a zygote.

Now, the birth of the first child after an MRT, MST in this case, took the world by surprise. While everyone was expecting for this to happen in the United Kingdom, the only country in the world with explicit legislation regarding these techniques, Dr. John Zhang, from New Hope Fertility Center, beat everyone to the punch. In September 2016, New Scientist broke the news that the first MRT-conceived baby had been born on 6 April 2016. The boy, who seems to be healthy, was born to a Jordanian couple who had previously lost two children to a mitochondrial DNA disease.

This remarkable accomplishment was met with both awe and criticism. As Nature puts it, “In interviews and at meetings, researchers and experts raised vague doubts about whether the New Hope team had properly informed their patients, or whether it had broken laws”. We think that this criticism was accentuated by the fact that Zhang was quoted saying that they went to Mexico because “there are no rules” there (although it is reasonable to suppose that Zhang was talking about the fact that in Mexico there are no specific rules governing MRTs).

The arrow states where MST was carried out. Purple, states where human life is protected from the moment of conception (i.e. implantation). Green, states where PNT is prohibited because human life is protected from the moment of fertilization. Orange, state where PNT is prohibited if the would-be-enucleated embryo is first created for a non-reproductive purpose. Image provided by the author and used with permission.

The arrow states where MST was carried out. Purple, states where human life is protected from the moment of conception (i.e. implantation). Green, states where PNT is prohibited because human life is protected from the moment of fertilization. Orange, state where PNT is prohibited if the would-be-enucleated embryo is first created for a non-reproductive purpose. Image provided by the author and used with permission.In order to address some of the issues we decided to explore the legality of MRTs in Mexico. We reached the conclusion (according to how we interpreted the law and with the available information about the case) that Zhang’s team broke Mexican federal regulations, specifically the Regulations of the General Health Law on Health Research. Before saying why we think this is the case, here is a brief overview of some of the Mexican laws that relate to MRTs.

There is no explicit federal law in Mexico that protects human life from the moment of fertilization or conception, and the Mexican Supreme Court’s latest ruling on an abortion case has asserted that at the federal level there is no recognised right to life from the moment of conception or fertilization either. This entails that PNT is, in principle, not outlawed at the federal level.

The only Mexican federal law concerning genetically modified organisms, the 2005 Law on the Biosafety of Genetically Modified Organisms, explicitly excludes in its Article 6, section V, the human genome and the modification of human germ cells from its oversight. And it defines GMOs, in Article 3 section XXI, as:

Any living organism, with the exception of human beings [emphasis added], that has acquired a novel genetic combination, generated through the specific use of techniques of modern biotechnology […]

This means that at the federal level neither MST nor PNT are in principle outlawed. At state level, however, things are different. Mexico is a federal republic composed of 32 states; each state has its own constitution. Of those 32 states, nine have laws that protect human life from the point of fertilisation, and nine have laws that protect human life from conception. According to a ruling of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, that applies to Mexico, conception should be understood as the moment at which implantation occurs. This means that in those states with laws protecting human life from the moment of fertilization, PNT is prohibited given that it intentionally destroys a human embryo for the benefit of another one.

Zhang’s team broke the Regulations of the General Health Law on Health Research, according to how we interpreted the law and with the available information about the case, because they did not aim at solving a sterility problem. Article 56 of such regulations state that:

Research on assisted fertilization will only be admissible when it is applied to solve sterility problems that cannot be solved otherwise [emphasis added], respecting the couple’s moral, cultural, and social points of view, even if these differ from those of the researcher.

Sterility is defined as the failure to achieve a clinical pregnancy after 12 months of regular unprotected sexual intercourse. If research on MST is used to solve sterility problems that cannot be solved otherwise then it would not violate Article 56; if research on MRTs is not used to solve sterility problems that cannot be otherwise solved then it would violate Article 56. In Zhang’s team’s case their research included a woman who could get pregnant and deliver a live baby and thus violated Article 56 of the Regulations of the General Health Law on Health Research.

Featured image credit: IVF by DrKontogianniIVF. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Mitochondrial replacement techniques and Mexico appeared first on OUPblog.

To ‘Ave’ or to hold: why certain music is banned from the civil marriage ceremony

The phone rings one Monday morning and, on the other end of the line, an anxious Bride-to-be is desperate for help. Having meticulously planned her civil marriage ceremony she has hit an unexpected obstacle with only days to go before the big day. She imagines gliding down the aisle towards her Groom whilst a choir sings a beautiful choral arrangement of Schubert’s famous Ave Maria, but there’s a hitch: the Registrar has just been in touch to point out that the text of the Ave Maria is religious and, therefore, not permitted in a civil ceremony.

As a supplier of professional choirs for weddings this scenario is all too familiar. So, why isn’t religious music allowed at a civil marriage ceremony and what can be done to give the anxious Bride a musical experience befitting the ‘best day’ of her life?

Before civil marriage was introduced on 17 August 1836, couples could only marry legally in a Church of England ceremony. The revolutionary new ‘Act for Marriages in England’ meant that a marriage could take place in any licensed venue (religious or not) with no restrictions on the choice of music.

This sounds like the type of progressive attitude to marriage you’d expect to still see represented in law today. However, just twenty years later ‘The Marriage and Registration Act 1856’ was introduced, requiring that under no circumstances ‘shall any Religious Service be used’.

Nearly 150 years later, a further Parliamentary Act has relaxed these restrictions slightly, but the wording is still ambiguous, stating that ‘proceedings may include readings, songs, or music that contain an incidental reference to a god or deity in an essentially non-religious context’. The Registrar has the authority to either approve or reject the musical content of a ceremony at their discretion, and interpretations of this latest Act can vary significantly.

On rare occasions religious music slips through the net, and choirs have been surprised to find themselves at Registry Offices performing J.S.Bach’s Lobet den Herrn, alle Heiden (Praise the Lord, all ye nations), or the Adagio for Strings by Samuel Barber in his version for choir that uses the text of the Agnus Dei from the Latin Mass. However, this is highly unusual and most Registrars would quickly reject these songs.

‘Wedding flowers’. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

‘Wedding flowers’. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.So nowadays, as it was in 1856, if you want to walk down the aisle to Schubert’s Ave Maria or Mozart’s beautiful Laudate Dominum (Praise the Lord) then your best option is still to have a church wedding. However, when Classic FM invited me to provide a choir to sing both these pieces at the civil marriage of their Chairman, Lord Allen of Kensington, I was curious as to how they had managed to secure the Registrar’s agreement to including these pieces in the ceremony.

The answer lay in some careful planning and creative thinking. Lord Allen had determined with his Registrar exactly when the ‘Proceedings’ would begin and end; a typical civil marriage at a Registry Office can last just fifteen minutes with ceremonies scheduled back to back throughout the day. Lord Allen’s ceremony was at Kensington Palace, one of thousands of alternative licensed venues in the UK, which can often offer the flexibility of planning an extended civil ceremony, rarely available at a Registry Office unless a couple books a ‘double’ ceremony slot. At Lord Allen’s wedding, after the ‘Signing of the Register’ which marks the official end of the civil ceremony, the Registrar promptly left the venue so the newly married couple and their guests (still seated inside) could enjoy a ‘religious’ continuation of their celebration without any restrictions.

So, what advice is there for couples wanting a choir at their Registry Office ceremony where only non-religious music will do?

Whilst Registry Offices usually have an audio system installed for playing recorded music they are not in the business of providing live musicians and, unlike many churches, won’t have a dedicated Musical Director to answer queries and help with finding the right choir. Online Wedding Directories don’t tend to list choirs either but, for those who know what they’re looking for, there are some helpful choral directories. Two of the most popular, British Choirs on the Net and Gerontius, list choirs geographically; the latter even has a dedicated page for wedding choirs who can be hired.

This won’t be a straightforward approach for everyone and, for those needing more advice, contacting a Music Agency could be a better option. Most agencies can organise bookings very quickly and they are experienced in asking all of the right questions to make sure things run smoothly on the day, for example; how many singers will be needed and will there be room for them in the venue? Will a keyboard be required, or any amplification? Will the choir be able to sound-check in the venue ahead of the ceremony?

It’s a good idea to request sample recordings before booking, to be sure of getting a quality performance and to ensure that the choir are aware of any non-religious music choices. Not every choir will have a repertoire of appropriate songs, and they may need time to source the music and rehearse it. I advise clients to choose their music as soon as possible and to keep the Registrar regularly updated to avoid disappointment, which proposes another challenge: where can you find suggestions of choral music for civil marriages?

A few years ago I decided to build a library of appropriate songs that would be routinely approved for civil ceremonies. I had a small collection already, including Weddings for Choirs. Further online research revealed plenty of suggestions for non-religious solo voice songs and instrumental pieces listed on wedding music websites, but virtually nothing for choirs. A search for ‘Wedding CD’s’ uncovered only a single piece of unaccompanied non-religious choral music: C.V. Stanford’s beautiful setting of The Blue Bird, a poem by Mary Elizabeth Coleridge. In my view the repertoire needed expanding.

With advice from Registrars I started building a list of the most requested songs for civil ceremonies (Kissing You by Des’ree, from the movie Romeo & Juliet, topping the list) and hunted for choral versions of them, commissioning arrangements for any I couldn’t find already published. I also reached out to composers, seeking recommendations from their catalogues, and soon a lot of new music began to arrive in my in-tray.

The result was an extensive list of non-religious music appropriate for civil ceremonies, which was accompanied shortly after by an album of highlights from the list, entitled My Promise – Music for All Weddings (playlist available below), accompanied by helpful notes to aid couples making their music selections.

Similar to a church wedding, there are three main opportunities to have music during a civil marriage ceremony:

The Entrance

The Signing of the Register

The Exit

Registry Offices are generally much smaller than most churches, and so it’s important to programme something reasonably short for the Entrance music. I once arranged a choral version of Pachelbel’s Canon for a wedding at Hampton Court. It had a flexible middle section that could be extended if the Bride needed more time at the door for photos. Having carefully rehearsed her walking pace, we were all taken aback when she raced to her waiting Groom before we’d even reached the end of the opening line. More shocking was the Registrar’s reaction, which was to frantically signal the universal hand gesture for ‘cut’!

During the Signing of the Register some music to entertain the guests can help to avoid uncomfortable silences. Whilst the couple concentrate on their paperwork, something reflective and calming can work well here, or perhaps two contrasting pieces if the Registrar allows the time.

The exit music is another chance for a couple to put a musical stamp on their celebration, with a send-off that is both personal and uplifting. Apparently one of the most requested Exit songs for civil ceremonies is At Last!, made famous by Etta James in the 1960’s; a fitting sentiment for many couples as they set off into their married future together.

So let’s return to that desperate phone call from the anxious Bride who really can’t get married without hearing Schubert’s Ave Maria as she enters the Registry Office. It may still be possible to persuade her Registrar to allow it as having only “an incidental reference to a god or deity in a non-religious context”, so long as it be performed as originally conceived. It is actually a misconception that Schubert set it with the sacred text of the Ave Maria. In fact, it was as part of a song cycle published in 1826 and took its text from a poem by Sir Walter Scott called The Lady of the Lake. Schubert’s song, entitled Ellens dritter Gesang (Ellen’s third song) characterises Ellen Douglas, a frightened girl in hiding who makes a prayer to the Virgin Mary for help.

Featured image credit: Image by James Davey. Used with permission.

The post To ‘Ave’ or to hold: why certain music is banned from the civil marriage ceremony appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers