Oxford University Press's Blog, page 383

April 5, 2017

Closer to fiction: a look at the unreliability of autobiographies

How accurately do writers depict themselves? Through researching the life English writer Angela Carter, Edmund Gordon discovered an interesting difference between what biographies and autobiographies can provide.

In this excerpt from The Invention of Angela Carter, Gordon discusses the distinct purposes behind biographies and autobiographies.

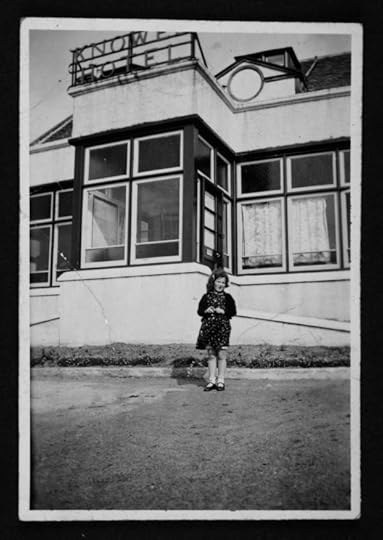

The way people look, how they speak, the quality and frequency of their laughter – all these things help shape our understanding of them, for if we invent ourselves, we also invent one another. Writer Angela Carter knew this. In 1969, she wrote: “I feel like Archimedes and have just made what seems to me a profound insight – that one’s personality is not a personal thing at all but an imaginative construct in the eye of the beholder.” Even so, she loathed it when people constructed her in ways that weren’t compatible with how she saw herself. Several witnesses recall the party at which an editor at a national newspaper–a woman who had idealised her as “a New Age role model, an earth mother”–asked her to write something on the summer solstice at Stonehenge. Angela looked “pityingly” at the woman and said: “You just haven’t got me, have you dear?”

Photo provided by the Angela Carter Estate.

Photo provided by the Angela Carter Estate.But writers continue to be invented and reinvented by their readers, long after their own last words on the matter. As Auden wrote of Yeats’s death: “he became his admirers.” Angela Carter has become hers in ways that have often ignored her wish not to be defined by her roles. Her obituaries demonstrated an impulse towards myth-making and sanctification. They emphasized her gentleness, her wisdom and her “magical” imagination, at the expense of her intellectual sharpness, her taste for violent and disturbing imagery, and her exuberant sensuality. “She had something of the Faerie Queene about her,” wrote the novelist and cultural critic Marina Warner in the Independent, “except that she was never wispy or fey.” That nod towards complexity was rare. In the New York Times, Salman Rushdie identified her straightforwardly with “the Fairy Queen,” adding that “English literature has lost its high sorceress, its benevolent white witch.” In the Sunday Times, her editor and confidante Carmen Callil described her as “the oracle we all consulted,” and her friends as “an enchanted circle.” The novelist Margaret Atwood, writing in the Observer, went even further in flattening this complicated modern writer into the shape of an age-old female archetype: “The amazing thing about her, for me, was that someone who looked so much like the Fairy Godmother…should actually be so much like the Fairy Godmother. She seemed always on the verge of bestowing something – some talisman, some magic token you’d need to get through the dark forest, some verbal formula useful for the opening of charmed doors.”

Sometimes this mythic version of Angela Carter has taken on a life of its own.

During the five years I’ve spent researching Angela Carter’s life, her closest friends have told me things that can’t be true. Fantasy has a habit of corrupting memory. This is something that biographers – who invent their subjects out of various kinds of evidence, including testimony – need to bear in mind. A further consideration in this case has been that Angela lived to an unusual extent (even by the standards of her profession) in her own fantasies. She wasn’t always a reliable witness to her own life. “I do exaggerate, you know…I exaggerate terribly,” she once admonished a friend who she feared had taken her too seriously. “I’m a born fabulist.” But she believed that even the most imaginatively sculpted confession could reveal truths about the confessor’s experience:

Autobiography is closer to fiction than biography. This is true both in method – the processes of memory are very like those of the imagination and the one sometimes gets inextricably mixed up with the other – and also in intention. “Life of” is, or ought to be, history: that is, “the life and times of.” But “my life” ought to be (though rarely is) a clarification of personal experience, in which it is less important (though only tactful) to get the dates right. You read so-and-so’s life of somebody to find out what actually happened to him or her. But so-and-so’s “my life” tells you what so-and-so thought about it all.

I’ve tended to rely on her account when I haven’t encountered anything that obviously undermines it. My guiding principle has been one of the last things she ever wrote: “the really important thing is narrative . . . We travel along the thread of narrative like high-wire artistes. That is our life.”

Featured image: Blur bookcase by Lum3n.com. Public Domain via Pexels.

The post Closer to fiction: a look at the unreliability of autobiographies appeared first on OUPblog.

The Honourable Members should resign

On 16 March, less than nine months after the public voted to leave the European Union (EU) in a hotly contested referendum, Britain enacted a law authorizing the government to begin the process of negotiating “Brexit,”— Britain’s withdrawal from the EU.

Despite the near unanimous conclusion of economists that Brexit would lead to a less prosperous Britain, concerns about stifling EU regulations, payments to Brussels, and the requirement of EU members to allow unfettered in-migration from the EU led voters to support Brexit by a margin of 52 to 48%.

And, in the words of Prime Minister Theresa May after the June vote, “Brexit means Brexit.”

Although there was much talk of “Bregret” following the referendum, recent polling suggests that British attitudes have not changed much since June. According to a December CNN/ComRes survey of 2048 voters, if asked to vote again, Brexit would still come out ahead, 47 to 45%. Further, by a margin of 53 to 35%, those polled felt that it is unnecessary to hold a second referendum to confirm the Brexit terms negotiated by the government. These results are particularly striking, since the same poll found, by a 44 to 24% margin, that respondents felt Brexit would make them personally worse off financially.

After Britain’s Supreme Court ruled that Parliament must ratify the Prime Minister’s request to invoke Article 50, the clause in the Treaty of Lisbon that will trigger the two-year period during which Britain will negotiate the terms of its exit from the European Union, Prime Minister May sought—and received—Parliamentary approval. I remain puzzled that, when faced with this decision, British voters deliberately voted for the option that will make them poorer. No, it won’t bankrupt the country and Britain will soldier on, but still, it will be poorer. And it will not be freed from EU regulations, fees, or migration. If Britain wants to continue to sell goods to the EU—the destination for the majority of its exports–it will be forced to abide by EU rules and pay EU-mandated fees for the privilege. And the negotiations between the UK and EU will probably not result in Britain maintaining full access to the EU’s market for goods and services without reciprocal concessions on immigration.

If you, as a Member of Parliament, represented to your constituents that you opposed Brexit, don’t you have a moral responsibility to give your constituents what you promised them?

I am similarly puzzled by Parliament’s vote to trigger Article 50. According to a head-count by the BBC prior to the June referendum, Remain was backed by 479 MPs, including 185 Conservatives, 218 Labourites, 54 Scottish Nationalists, and 8 Liberal Democrats. Brexit was supported by only 158, mostly Conservative MPs.

The Parliamentary vote to trigger Article 50 passed by a vote of 498-114, a distinct reversal of most members’ pre-referendum stances. Both the Labour and Conservative leaders urged their MPs to support the Brexit bill. Only 47 Labour MPs (several of whom resigned from Labour’s front bench) and one Conservative MP defied their leadership and voted against the bill. And, of course, all 20 members of May’s Cabinet—including the 15 that had opposed Brexit prior to the referendum (including May herself)—supported the bill. Further, as many as 117 MPs who represented constituencies where Remain was in the majority voted in favor of triggering Article 50.

This does not make sense to me. If you, as a Member of Parliament, represented to your constituents that you opposed Brexit, don’t you have a moral responsibility to give your constituents what you promised them? The counterargument—and it is not weak—is that Brexit was the will of the people and the will of the people is what democratic government is all about.

Still, MPs who opposed Brexit prior to the referendum had another option. They could have resigned from Parliament rather than support a law that they had promised to oppose. And they could have run for the seat that they had just vacated with the explicit commitment that they would oppose all legislative measures that would further Brexit.

Resigning, rather than voting to support a law with which they disagree, would have had the advantage of taking the debate to individual Parliamentary constituencies, where it likely would have had a full airing, rather than rely on the national Remain and Brexit campaigns, the latter of which became notorious for making fraudulent claims.

And, by putting principle above politics, it would have been the right thing to do.

Featured image credit: Houses of Parliament- Big Ben by Wilson Hui. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post The Honourable Members should resign appeared first on OUPblog.

What to do in New Orleans during the 2017 OAH annual meeting

The Organization of American Historians is just around the corner, and we know you’re excited to attend your panels, debate American history with your fellow historians, and dive into some amazing new books.

We also know you would love to explore the beautiful city of New Orleans when the conference is done for the day, or in between panels and conference activities. We’re here with a few suggestions on how to spend your leisure time. From delicious food, to beautiful architecture, this location is sure to offer something for everyone.

1. Rain or shine, you can always find some good food in New Orleans. Just a 5-minute walk from the Marriott, Criollo is lauded for its Creole food. Have a bowl of crawfish bisque or a baked stuffed Creole redfish. Or, if you’re in the mood for something sweet instead, order a basket of beignets with some extra napkins.

2. The conference venue is in the heart of the French Quarter, a perfect place to stroll when you are done for the evening or taking a break between panels. Some must-see sights include the Faulkner House, Jackson Square, Bourbon Street, and the Cabildo. But even if you don’t have time to see these locations, it’s worth a walk around the neighborhood just to check out the architecture.

“New Orleans: Front of the Cabildo on Jackson Square” by Infrogmation of New Orleans. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“New Orleans: Front of the Cabildo on Jackson Square” by Infrogmation of New Orleans. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.3. If you’re staying in New Orleans for longer than OAH, you need to take time to do a cemetery tour. Above ground to protect them from rising water levels, these ghostly cemeteries are replete with beautiful stonework and design. St Louis Cemeteries are among the most popular, home to the departed Marie Laveau, Dominique You, and many others. You can stroll through on your own or book a guided tour.

4. It may be on the opposite side of the city, but the Audubon Nature Institute is worth the 25-minute drive. Set in the heart of the large Audubon Park, this institute houses an aquarium, a zoo, an insectarium, a golf course, and an IMAX theater. It’s fun for the whole family.

5. Perched on the edge of the Mississippi River, Woldenberg Park is just a 10-minute walk from the conference site. The 16 acres feature sculptures, artwork, and a 90-foot linear water feature set in front of Audubon Aquarium of the Americas. Children can run through the water to cool off, or enjoy the light shows.

6. If you’re looking to shop, or just enjoy a scenic view along the river, check out the Riverwalk Marketplace, home to over 75 shops and restaurants. Pick up your trip souvenirs and enjoy the sparkling nighttime view.

Featured image credit: “Bourbon Street – New Orleans in the Early Morning” by Eric Gross. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post What to do in New Orleans during the 2017 OAH annual meeting appeared first on OUPblog.

The centenary of The Scofield Reference Bible

In the history of evangelical Protestant thought in America, few publications have been more influential, or more seminal, than The Scofield Reference Bible (first published in 1909, and thoroughly revised by the original author for publication in 1917). The Rev. Dr. C. I . Scofield labored for years to produce this annotated and cross-referenced edition of the King James Version Bible, in order to explicate for interested Christian believers an approach to understanding the deeper meaning of the Scriptures.

The “Dispensational” interpretation that the Scofield Bible presents – the doctrine that the relations between God and human beings have undergone changes through time, from the “Dispensation of Innocence” that characterized the life of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden to the “Kingdom Age” that will begin with the Second Coming of Jesus Christ and the establishment of the Kingdom of God on Earth – has been of immense significance. Millions of Christians in the United States have derived their understanding of their faith from this approach to the Bible. It has formed the basis of Biblical instruction in places such as Dallas Theological Seminary and the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago, as well as the Philadelphia College of Bible, where Dr. Scofield taught in his final years.

This branch of Christian thought has also found expression in popular publications such as Hal Lindsey’s The Late Great Planet Earth and the Left Behind series of futuristic novels.

No student of the history of Christianity in America can afford to neglect the importance of the Scofield Bible. But its influence has ranged far beyond the confines of conservative evangelical thought.

Before Dr. Scofield produced his Bible, the usual ways in which the Christian Bible was presented were either an unadorned text or a text with marginal references from one part of Scripture to another (“cross references”). Dr. Scofield added two elements that greatly expanded the options for biblical exposition. The first was a system of “chain references,” following great Biblical themes such as “Grace” through the Biblical text, linking them verse by verse and adding an explicatory note at a particularly important place. The second was a thorough set of introductions to each biblical book and page-by-page explanatory notes that helped the reader along with information at the exact place where it was most needed: while reading the text itself.

This format has been followed by increasing numbers of Bible publishers, who have expanded the “study Bible” format to reach many readers outside the orbit of the Scofield Bible itself. It has become one of the most prevalent and familiar forms in which Bibles are published today, used not only in churches or religious study groups, but in secular classrooms and by general readers of varying religious persuasion, or of no religion at all.

Featured image credit: Vitrail de la cathédrale américaine de la Sainte-Trinité de Paris, by GO69. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The centenary of The Scofield Reference Bible appeared first on OUPblog.

April 4, 2017

MPSA 2017: a conference and city guide

The Midwest Political Science Association will hold its annual conference from 6 April through 9 April in Chicago, IL at the Palmer House Hilton. This year marks the 75th anniversary of the MPSA conference. The conference is organized in more than 80 sections by topic, often interdisciplinary and providing new perspectives and research into the field. With a large variety of panels and events to attend, we’ve selected a few on our list to share, as well as what to check out during your free time in Chicago:

Wednesday, 5 April

MPSA Welcome Reception, 6:30-7:30pm

Thursday, 6 April

Panel: Explaining the Electoral Outcomes of Key 2016 US House Elections, 1:15 – 2:45pm; Discussion of key House Elections in 2016, including Iowa, Florida, and Texas.

Roundtable: HB2 and Transgender Rights, 3:00 – 4:00pm; What impact did HB2 have on North Carolina and on the fight for transgender rights more broadly?

Pi Sigma Alpha Lecture: What Life is like as a Scientist in Congress, 4:45 – 6:15pm; Congressman Bill Foster, scientist and businessman representing the 11th Congressional District of Illinois, gives a lecture on being a scientist and congressman.

Friday, 7 April

Paper Session: Flirting with Disaster: Politics, the Environment and Public Policy, 8:00 – 9:30am; A discussion of environmental politics and policy from crises to resources.

Roundtable: The Media and the 2016 Election: A View from the Campaign Trail, 1:15 – 2:45pm; Speakers include Nia-Malika Henderson from CNN, Steve Peoples from AP, and Molly Ball from The Atlantic.

Panel: Social Policy and Political Behavior Around the World, 4:45 – 6:15pm; Focusing on comparative political economy around the world.

Saturday, 8 April

Roundtable: The Women’s March on Washington, 1:15 – 2:45pm; Draws together discussions of women’s activism, intersectionality, interest groups, mobilization, connections to the presidential campaign, and prior instances of women’s activism.

Panel: The Refugee Crisis and its Impact on Politics, Policy, and State, 3:00 – 4:30pm; A panel about immigration and citizenship for refugees and the cause and effect around the world.

MPSA President’s Reception, 6:30 – 8:00pm

Sunday, 9 April

Paper presentation: Understanding the Success and Failure of Populism and the Radical Right in Europe, 9:45 – 11:15am; Studying the rise of the radical right in Europe.

Panel: Reexamining Political Philosophy: Rousseau and Nietzsche on the Nature and Status of Philosophy in the Modern World, 11:30am – 1:00pm; In depth looks at Rousseau and Nietzsche, focusing on virtue, freedom, and modernity.

Be sure to explore the Windy City itself when not at the conference. Whether it’s your first time or you’re a seasoned expert, seeing the sights along Magnificent Mile and at Millennium Park are a must, especially if the weather is in your favor. For some culture in addition to the mental stimulation of MPSA, explore Art Institute of Chicago or the Field Museum of Natural History. Finally, to wind down at night, check out Chicago’s variety of cuisine such as Big Jones for classic Southern comfort food, Joe’s Seafood for steak and seafood, or try a must-have Chicago deep dish pizza at Pizano’s Pizza.

While at MPSA, don’t forget to come by and visit the OUP booth – grab a journal and browse our selection of books at a discounted rate. We’ll be at booths 201, 203, and 205. Keep up with @OUPPolitics on Twitter for updates at MPSA. We’ll see you there!

Featured image credit: City with river in middle during cloudy day by Grzegorz Zdanowski. Public domain via Pexels.

The post MPSA 2017: a conference and city guide appeared first on OUPblog.

Reflections on the Teflon king, Charlemagne

Few historical figures have been as universally acclaimed as Charlemagne. Born on 2 April, probably in 748, he became sole king of the Franks in 771 and Emperor in 800. Charlemagne was always very careful to polish his own image. Official writing, like the Royal Frankish Annals, omits or misrepresents delicate events and glosses over military defeats. It is hardly odd that Einhard, a monk who had served at Charlemagne’s court and that of his son, wrote an admiring life in the 830s. Another monk, Notker produced a biography in the 880s which is shot through with wondrous stories about the great man, perhaps to contrast with the increasing chaos of his own age. In the Song of Roland, earliest of the great Chansons de Geste, written down about 1100, Charlemagne emerges as the champion of Christendom against the Muslims, although nothing supports the notion that his wars in Spain were ideologically inspired. French and German popular literature from the 12th century onwards created a vast mythology around the figure of the great king. Dante introduced him into the Divine Comedy as a warrior of the faith, and in the later middle ages he emerges as one of the nine worthies of all history. Such was his reputation that European aristocrats claimed descent, if not from the great man or his family, then at least from his paladins. In the 19th century French and German historians competed to claim him for their own nation. In the 20th he became the darling of the Eurocrats for whom his empire prefigures their vision of a united states of Europe. The European Union began, of course, in 1957 with the treaty of Rome of 1957, an earlier symbol of unity. But the key document governing its development was agreed at Maastricht in 1992, and that was an important Carolingian centre. The apparatus of European government commutes between Strasbourg and Brussels, effectively crossing Austrasia, the ancient Frankish realm which gave rise to the Carolingian house.

It is perhaps more surprising that he has received such considerate treatment by modern historians. The stock of great figures of the past commonly fluctuates. King John, once regarded as the worst English king, has been praised as a skilled administrator, while even in France Napoleon has his detractors. No such rise and fall marks the story of Charlemagne, he is indeed a blue-chip stock. The very titles of recent books about him (Charlemagne: Father of a Continent by Alessandro Barbero, “Europae Pater: Charlemagne and his Achievement in the Light of Recent Scholarship” by D.A. Bullough, and Charlemagne. The Formation of a European Identity by Rosamond McKitterick) are paeans of praise! It cannot be claimed that this roseate vision arises simply from the mythology enshrined in medieval stories and romances or from the subtly prejudiced products of the Carolingian court. Every shred of evidence has been scrutinised and reinterpreted. And every time the great king has emerged smelling of roses.

“Seen as equally impressive is Charlemagne’s cultivation of learning, patronage of scholars and promotion of reform in the Christian Church.”

Except once. The only genuinely critical academic study is that of H. Fichtenau (The Carolingian Empire) which was written in 1949, at a time when the idea of a strong man uniting the continent by force was perhaps less than welcome. Fichtenau’s take on a ramshackle empire inevitably reminds us of the chaos of the house that Hitler built under which this Austrian scholar lived for much of his life. But is this simply a product of its time, a sport, an exception that proves the rule of the glory of Charlemagne?

Historians have been impressed by his administration, and Fichtenau’s harsh comments are often seen as the inappropriate application of modern standards. But Charlemagne’s structure can fairly be compared with that of Byzantium. The emperors at Constantinople had to cope with aristocratic faction, but Charlemagne had to share his authority with an elite which he constantly consulted. Seen as equally impressive is Charlemagne’s cultivation of learning, patronage of scholars and promotion of reform in the Christian Church. This had the effect of creating a culture which looked back to Rome and its inheritance of law and justice. This cultural imperative was particularly evident from the 780s . But we need to consider why he was doing this? We might admire his administrative efficiency, promotion of the Christian Church, patronage of missionary activity, and promotion of cultural unity. The victims of the Verden massacre, all 4500 of them and their relatives and friends, might have had a different take on the great king. And year after year his armies visited fire and massacre upon the people of Saxony (and, indeed anywhere else where they went). This is not to judge him by modern standards of international law. It is to remember that the man was a soldier. That beneath the glory of empire and the praises of the court intellectuals was a reality of blood and iron. Charlemagne was first and foremost a soldier, and what he built was designed to bind his lands together to bolster his military power. Prestige, kudos, the praise of the learned the title of Emperor—all were contributions to this end. Charlemagne may have been a man of vision—or at least a man who developed a vision, but that served to underline his brute military power. He was man of his age, an age truly of iron when war was a norm and peace something exceptional.

Featured image credit: “Equestrian statue of Charlemagne” by Agostino Cornacchini, photo by Myrabella. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Reflections on the Teflon king, Charlemagne appeared first on OUPblog.

Wearable health trackers: a revolution in cancer care

Activity trackers, wearable electronics that collect data passively and can be worn on the body, infiltrated the world’s fitness market in the last decade. Those devices allowed consumers to track steps and heart rate. Next, wearable devices overtook the chronic illness market, giving patients the power to track health behavior and adherence to medication, which could be easily reported back to doctors. In the past year wearable trackers have stepped into what may be their most important passive monitoring role yet: cancer care.

Last summer, at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, 40 multiple myeloma patients joined a small trial using wearable devices to track activity and sleep, assessing those patients’ quality of life. At Cedars–Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, oncologists recently launched a similar study during which cancer patients will be given Fitbits, allowing oncologists to assess whether patients are active enough for chemotherapy. At the Dana–Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, researchers are using Fitbits to study how weight loss affects breast cancer recurrence. The list of other cancer centers launching studies of wearable devices goes on and on. Bloomberg reported that more than 300 clinical trials had incorporated the trackers into their design as of December 2015.

Wearable health trackers infiltrated the fitness market in 2009, the year Fitbit launched its first wristband. Initially, those devices were simple. Most came in wristband form, and they allowed consumers to track simple fitness behaviors, such as steps taken, floors climbed, and distance. Today, fitness trackers have advanced markedly, both in capability and in quantity. They now monitor, for example, steps, distance traveled, floors climbed, calories burned, minutes of activity, sleep time and quality, heart rate, and workout pace. Many other companies have since introduced other activity trackers. There are several popular brands. In December 2016, annual sales for wearable devices in the United States were expected to top $38 million, according to the Consumer Technology Association.

Fitbit Flex and accompanying wristband by MorePix. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Fitbit Flex and accompanying wristband by MorePix. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Clinical-grade wearable trackers are becoming more widespread, too. Most of those devices focus on chronic illnesses such as congestive heart failure, diabetes, hypertension, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The devices measure advanced behaviors beyond fitness, such as drug adherence, fertility, sun exposure, and health behaviors, continuously measuring people’s health status as they follow their daily routine.

Arvind Shinde, MD, a faculty physician at Cedars–Sinai, just launched a clinical trial to help his oncology patients live longer and better lives. Shinde and care providers like him are bringing wearable devices into more specialized areas of care, such as oncology, because they offer an enticing solution to a major problem. Right now, most cancer treatments involve expensive drug regimens meant to reduce the risk of relapse and extend patients’ lives. But growing evidence indicates that quality cancer treatment might be about more than just drugs; lifestyle choices matter, too. In a meta-analysis of 82 peer-reviewed studies about lifestyle interventions for cancer patients, physical activity had a small-to-moderate positive effect on cancer patients during treatment, including overall activity level, aerobic fitness, muscular strength, functional quality of life, anxiety, and self-esteem.

Shinde’s clinical trial at Cedars–Sinai, now in its final stages, used Fitbit Charge devices to assess whether 30 cancer patients were active enough to respond to chemotherapy. Shinde’s team asked patients to wear their Fitbits consistently for two weeks. The patients also completed questionnaires at two oncologist visits during the trial and will do so again at a six-month follow-up appointment. Using data from the trackers, Shinde plans to analyze his patients’ behaviors, including steps, stairs, heart rate, and sleep, as well as moments of peak activity and duration of sleep. He said that he hopes to use that information to tailor cancer treatments for each patient.

At Dana–Farber, medical oncologist Jennifer Ligibel, MD, runs a similar trial. Using Fitbits, Ligibel’s team will monitor 3,200 overweight and obese women with early-stage breast cancer for two years. Recruitment for the trial is just beginning, but all patients will participate remotely and be given a health coach to encourage them.

“We’ve known for a while that women who are heavier when they are diagnosed with breast cancer have a higher rate of breast cancer recurrence and mortality than thinner women. But we don’t know if reducing weight changes this,” Ligibel said. She said that she hopes her study can provide context for what oncologists already know about breast cancer treatments.

At Memorial Sloan Kettering, Neha Korde, MD, an assistant professor, focuses on multiple myeloma, a blood cancer in the bone marrow with no known cure. Korde oversees a forthcoming clinical trial that will monitor 40 recently diagnosed multiple myeloma patients for nine months, using Medidata activity trackers to gather data on sleep, activity, and self-reported quality of life. Steroids are a common treatment to reduce pain for myeloma, but Korde said that many of her patients find themselves unable to sleep once they take steroids. That loss of sleep can severely affect the body’s ability function and fight disease. By measuring sleep and activity data through wearable trackers, she could assess which patients respond best to certain treatment and course quickly for those who might be struggling.

“A personalized approach matters,” Korde said. “And we should be able to manage side effects and adverse events, taking a more tailored approach if a patient needs it.”

Most consumer-grade wearable trackers, like the Fitbit, are not yet validated for medical use. That is one reason why all those providers approach their trials with some skepticism. They aren’t sure what kind of data will turn up, and they’re hopeful, but not convinced, that patients will keep their trackers on for the duration of the studies.

However, those cancer trials Memorial Sloan Kettering, Cedars–Sinai, and Dana–Farber, and others like them, will potentially yield important data about how providers and scientists can best use wearable technology to collect important data. Shinde’s data look promising so far, he said, with strong insights emerging from the tracker data.

“People are really interested in this work,” Korde said. “Coming up with a cocktail of targeted drug agents is great. But if a patient falls apart, that alone isn’t going to work, so clinicians are interested in looking at what else is out there. Remote monitoring should be one of our most fundamental next reaches: If there is no cure, we must understand all the different aspects of helping a patient improve quality of life.”

A version of this article originally appeared in the Journal of the Nation Cancer Institute.

Featured image credit: Heart rate monitoring device by pearlsband. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Wearable health trackers: a revolution in cancer care appeared first on OUPblog.

What Orwell and Snowden overlooked

In response to the ‘Fake News’ and ‘Alternative Facts’ doctrine twittered so incoherently from the Trump White House, people have remembered George Orwell’s Doublethink and Newspeak, and sales of 1984 have boomed in the USA. No doubt we shall soon appreciate anew the Orwellian warning that Big Brother is Watching You. The revelations by Edward Snowden still linger in our consciousness as a reminder of the caution.

But I contend that Orwell and Snowden shared an oversight. Few people realize – the novelist John le Carré being one exception – that some of the most intrusive surveillance has been not governmental, but private. The Islington News made the point in 2007 when it commented on the CCTV installations within 200 yards of Orwell’s final residence: ‘far from being instruments of the state, the cameras – more than 30 of them – belong to private companies and well-to-do residents.’

Some of the twists and turns in the story of private surveillance will be familiar to the modern reader, even if they were mostly not to Orwell. The activities of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, with its motto ‘The Eye That Never Sleeps’, are an example. And it wasn’t just the Pinkertons. There was a mushroom growth in private detective agencies in late nineteenth century America. The spied on two targets were the principle source of their profit. The first were workers who tried to unionize or draw attention to unsafe working conditions. The second, with divorce booming by the 1920s, was the family bedroom and its adulterous extensions.

More of a surprise to me, when I looked at it, was the role that credit agencies played. Lewis Tappan, the anti-slavery radical who championed the Amistad case, was, less famously, a pioneer of the creditworthiness assessment industry. His firm listed and graded 800,000 US businessmen by the end of the nineteenth century, having subjected them and their habits – alcohol consumption, gambling, sexual behaviour – to surveillance by 10,000 professional informers.

Today, business surveillance manifests itself in shapes with which we are familiar, even if Orwell and Snowden ignored them. Do you have a supermarket credit card? It is watching you and bending your mind through targeted advertising.

Some of the most intrusive surveillance has been not governmental, but private.

Private surveillance is multi-faceted, and is with us to stay, particularly the unsavoury history of anti-labour surveillance. It took many forms, ranging from spying on bathroom visits to identifying activists and blacklisting them. Ralph Van Deman and ‘Blinker’ Hall, heroes of wartime military intelligence in America and Britain respectively, both set up private anti-labour spying units in the 1920s. Such surveillance continued into the twenty-first century, and now shows signs of reviving in Trump’s America and May’s UK, where The Consulting Association is the successor to Hall’s Economic League. Which of our major construction projects, ranging from Crossrail to the new Forth road bridge, has been free of surveillance-and-blacklisting controversy?

Attempts to curb government surveillance have yielded at least partial success, and have received media attention. In spite of the prevalence of blacklisting in our society and the phenomenon of merciless hacking and other intrusiveness by mass-circulation newspapers, less constructive attention has been paid in our two democracies to the excesses of private surveillance.

One reason for the strength of the headwind is that the press is privately owned, responsive to private business interests, and indisposed to report favourably on proposals for its own reform. When it does listen to surveillance grievances, they are those of the middle classes concerned with their own right to privacy. So how impartial has our ‘free’ and ‘truthful’ press been? I argue that Orwell and Snowden, with their blinkered ‘statist’ preconceptions, also carry a share of the responsibility. For whatever reason, we have not properly addressed some of the kinds of surveillance that have done the most harm.

Featured image credit: Cameras Traffic Watching Surveillance by PublicDomainPictures. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post What Orwell and Snowden overlooked appeared first on OUPblog.

Testamentary freedom vs claims by family members

Should a person be free to dispose of property as she wishes on death, or be forced to leave it to certain family members? This is one of the most fundamental questions in succession law. Some (particularly continental European) jurisdictions allocate compulsory portions to certain family members, irrespective of any will. England and Wales, however, has a default testamentary freedom principle combined with the Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Act 1975, allowing certain people to claim discretionary provision out of the estate in limited circumstances.

In Ilott v The Blue Cross (2017), its first judgment on the 1975 Act, the Supreme Court struck a blow for testamentary freedom and against forced family provision. Melita Jackson died in 2004, leaving a £486,000 estate. Her will divided most of it between the Blue Cross, RSPB, and RSPCA. Mrs Jackson wrote a letter explaining the exclusion of her only daughter, Heather, from her will. Heather had left home in 1978 at the age of 17, without her mother’s knowledge, to live with her future husband. Mrs Jackson disapproved of her daughter’s lifestyle. Heather and her husband had five children and lived in straitened financial circumstances, Heather choosing to stay at home after the first child’s birth. Heather never went on holiday and had many items that were old or second-hand. Despite attempted reconciliations, mother and daughter were estranged for some 26 years, and Heather was aware before Mrs Jackson’s death that she would be excluded from the will.

Heather claimed her mother’s will failed to make ‘reasonable financial provision’ for her maintenance under section 1 of the 1975 Act. The litigation had a long history. In 2007, District Judge Million agreed that the will failed to make such reasonable financial provision. That’s the first stage of the claim, and in the second stage the court must decide what provision the claimant should actually receive out of the estate. At both stages, the court must consider various factors from section 3. Judge Million awarded Heather £50,000.

The Court of Appeal upheld his conclusion on the first stage. Allowing Heather’s second appeal to it seeking greater provision in 2015, the Court of Appeal made two criticisms of Judge Million’s approach. Firstly, he stated that the award should be “limited” because of Heather’s lack of expectation of provision and ability to live within her current means but omitted to explain “what the award might otherwise have been and to what extent it was limited”. Secondly, he failed to verify his award’s effect on Heather’s state benefits.

Because of those errors, the Court of Appeal re-exercised the discretion, concluding that Heather should receive £143,000 to enable her to purchase the housing association property in which she and her family were living, in addition to the reasonable costs of the purchase. Heather was also given an option to claim up to £20,000 as a capital sum from the estate. The Charities appealed that 2015 decision. They had been refused permission to appeal the first stage decision to the Supreme Court in 2011, so Heather was guaranteed to receive something from the estate whatever happened in the Supreme Court.

The debate over the proper balance between testamentary freedom and provision for family members will continue

The Supreme Court allowed the charities’ appeal, reinstating Judge Million’s £50,000 award. Lord Hughes, with whom all six other justices agreed, held that Judge Million had made neither error alleged. In relation to the first, the Act required “a single assessment by the judge of what reasonable financial provision should be made in all the circumstances of the case”. Judge Million was said to be perfectly entitled to take into account the relationship between Mrs Jackson and Heather as he had. The two dominant factors in the case were the estrangement and Heather’s strained circumstances. The Court of Appeal’s order, by contrast, had given “little if any weight” to the length of the estrangement.

The Supreme Court was also concerned that the Court of Appeal had given “little if any weight” to Mrs Jackson’s clear wishes. It was incorrect to say that the charities’ lack of any expectation of benefit because Mrs Jackson hadn’t been involved with them during her life was equal with Heather’s lack of similar expectation. They were the will beneficiaries, and didn’t need to justify their claim via needs as Heather did. The Court of Appeal erred in suggesting that they were not prejudiced by a higher award to Heather. It was also held erroneous to suggest that the court didn’t need to give specific consideration to Mrs Jackson’s wishes because Parliament had limited claims to particular circumstances.

On the second suggested error, the Supreme Court held that Judge Million had addressed the impact on benefits, and that if Heather spent the £50,000 in a particular way that impact would be minimised. The £50,000 award met many of Heather’s needs, allowing her to “buy much needed household goods and have a family holiday”, and should be restored.

Lady Hale (with Lords Wilson and Kerr agreeing) gave a supplementary judgment. She criticised the law for giving no guidance on the factors to be considered in deciding “whether an adult child is deserving or undeserving of reasonable maintenance”, particularly given the range of public views, and expressed “regret” that the Law Commission didn’t consider the underlying principles in 2011.

The result will relieve the charities, who took a financial and reputational risk in bringing the case to the Supreme Court. It’ll also be welcomed by private client practitioners generally wanting to assure clients that wills will be implemented.

But the Supreme Court’s decision may be challengeable in some respects. Since courts are often reluctant to consider conduct regarding familial relationships, the acceptance that Heather’s claim should be quite so limited with reference to the relationship between mother and daughter might be surprising. That said, I’ve advocated recognition of positive caring contributions and conduct where relevant, so it’s difficult for me to criticise its reasoning on converse estrangement cases.

The debate over the proper balance between testamentary freedom and provision for family members will continue. The “testamentary freedom” camp seem in a stronger position than before the Supreme Court’s decision. But it should be remembered that Heather still went away with something, even if some similar future claimants may not.

Featured image credit: Legal document, by Aaron Burden. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Testamentary freedom vs claims by family members appeared first on OUPblog.

April 3, 2017

Ten facts about children’s literature

Most of us have a favourite story, or selection of stories, from our childhood. Perhaps they were read to us as we drifted off to sleep, or they were read aloud to the family in front of an open fire, or maybe we read them ourselves by the light of a torch when we were supposed to be sleeping. No matter where you read them, or who read them to you, the characters (and their stories) often stick with you forever.

To celebrate these stories we’ve discovered a selection of ten facts about children’s books, their authors, and their history. What fact would you add to this list?

Some of the earliest “books” that combined both words and pictures, and that were read by younger people, are the Japanese illustrated scrolls of the 12th and 13th centuries.

The final book in the Harry Potter series was the fastest-selling book of all time, with fifteen million copies sold in the first day alone. The series as a whole has sold an estimated 450 million copies worldwide, and the books have been translated into over sixty languages.

It is thought that the first example of a fantasy story, for children, was F. E. Paget’s The Hope of the Katzekopfs , published in 1844.

In the first draft of Peter Pan the character of Michael was called ‘Alexander’ and Tinker Bell was called “Tippy-Toe.”

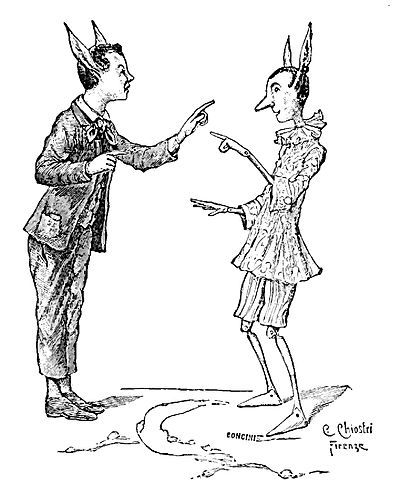

“Illustrations from ‘Le avventure di Pinocchio, storia di un burattino'” by Carlo Chiostri and A. Bongini. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

“Illustrations from ‘Le avventure di Pinocchio, storia di un burattino'” by Carlo Chiostri and A. Bongini. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Quentin Blake, well-known for his illustrations for Roald Dahl and (more recently) David Walliams, has more than 300 illustrated books to his name, including Zagazoo which has no words and tells the story just through his illustrations.

When Lewis Carroll (born Charles Lutwidge Dodgson), author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, was fourteen he began to produce a series of family magazines to amuse his ten brothers and sisters. These contained writings such as humorous poems, limericks, and contributions from other family members.

The original story of Pinocchio , arguably the most popular children’s book to come out of Italy, has the title character get in to many different scrapes that aren’t in the more well-known Disney version. This includes a fox and a cat trying to steal his money and Pinocchio being turned in to a donkey and sold to a circus.

The typical number of pages in picture books (illustrated books, usually for younger children) is just over thirty.

Before Enid Blyton became the famous author of the Famous Five stories her parents had wanted her to be a concert pianist. However she abandoned her musical studies to, train to be a teacher.

The first children’s annual, a yearly publication usually associated with a magazine, was printed in 1645 by the parents of Zurich. They made it in celebration of New Year, for the children to find in the city library, and it was a single sheet made up of an engraving and some verse.

Featured image credit: Photograph by Mi PHAM. Public Domain CC0 1.0 via Unsplash.

The post Ten facts about children’s literature appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers