Oxford University Press's Blog, page 379

April 14, 2017

The modern marvel of medicine

The art and science of general anaesthesia remains a relative mystery to the general public. In an age where instant access to information is the norm through smartphones and tablets, the critically important role of these lynchpin clinicians in so many facets of hospital medicine goes unpublished and unnoticed. It is usually the surgeon or emergency physician, so often popularised through television or film media, who fulfils the public’s desire for medical heroes. Yet, astonishing techniques are being quietly used every day to facilitate safe surgery, for example the administration of drugs to render temporary unconsciousness, cessation, or removal of pain, and the ‘numbing’ of body parts with regional anaesthetic nerve blocks to allow awake surgery.

The term ‘anaesthesia’ was first used by Wendell Holmes (1809─94) and is derived from the Greek ἀναισθησία (anaisthēsía), from ἀν– (an-, “not,” or “without”) with αἴσθησις (aísthēsis, “sensation”). The first use of herbal substances to treat pain and facilitate surgery can be traced back many thousands of years ago to the Mesopotamia era. Remarkably, the most popular ancient remedies of alcohol, cannabis, and the opium poppy remain useful pharmacological adjuncts in modern medicine. Nitrous oxide (or “laughing gas”) was discovered in the 18th century by Joseph Priestley (1733─1804); however, it was Humphrey Davy (1778─1829) who first hypothesised that, when inhaled, it may be useful as a painkiller during surgery.

Following experimentation with diethyl ether by William T G Morton (1819─68) and William Edward Clarke (1819─98), the first inhaled general anaesthesia for surgery was administered by Clarke for dental extraction in 1842. Crawford W Long (1815─78) utilised the properties of inhaled ether for more extensive surgery, such as amputations. Concurrently, Horace Wells (1815─48) had started to use inhaled nitrous oxide regularly for his dental patients. By the mid-19th century, ether became established as the first mainstream general anaesthetic drug. The second half of the 19th century witnessed the introduction of chloroform for general anaesthetic purposes, first demonstrated in 1842 by James Young Simpson (1811─70) whilst self-experimenting with friends.

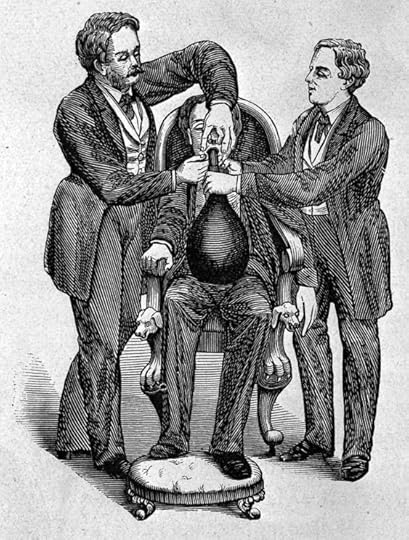

‘Adminsitration of nitrous oxide’ by Wellcome Images. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

‘Adminsitration of nitrous oxide’ by Wellcome Images. CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.The ability to render a part of the body insensate to allow surgical procedures without general anaesthesia is a truly phenomenal concept. It is documented that the Incas in Ancient Peru first used the leaves of the coca plant for its local anaesthetic properties. Following extraction from the plant, cocaine was used by Karl Koller (1857─1944) to topically anaesthetise his eye in 1884. However, considerable side effects and addiction encouraged the synthesis of alternative local anaesthetics, for example the development of procaine towards the beginning of the 20th century.

Often described as the forefather of regional anaesthesia, August Bier (1861─1949) was the first to describe and perform spinal blocks and intravenous regional anaesthesia – self-demonstration of the former leaving him with the first post-dural puncture headache. Faster-acting local anaesthetic agents with fewer side effects, coupled with more modern techniques such as the use of ultrasound to locate nerve bundles, have improved the safety profile of modern regional anaesthesia. There now even exists an ‘antidote’ to local anaesthetic overdose in the form of lipid emulsion therapy.

In 1934, the first intravenous anaesthetic agent, sodium thiopental, was synthesized. This heralded a major breakthrough in the induction of general anaesthesia. Although superseded by other intravenous agents such as propofol, etomidate, and ketamine, it still has medical uses today in obstetric anaesthesia and neurointensive care. Of interest, it is also the predominant ingredient used in euthanasia and in the execution of prisoners by lethal injection. A lesser-known fact is its use in smaller doses as ‘truth serum’ during interrogation scenes, popularised by films, television, and fiction novels. The supposed mechanism of action is by reduction of higher brain function coupled with the theory that lying is a more complex neurological action than telling the truth. In reality, there is little scientific evidence that can substantiate the reliability of this technique.

As the 20th century progressed, so did the advancement and discovery of newer anaesthetic drugs. These included opioids to treat pain, for example fentanyl, and muscle relaxants such as atracurium, to aid endotracheal intubation and abdominal surgery. Most notably, the introduction of inhalational volatile agents (such as halothane and sevoflurane) to maintain general anaesthesia provided superior conditions for surgery and prevented accidental awareness, so often associated with exclusive use of nitrous oxide.

So, where does the future lie in the specialty of anaesthesia? Equipment and monitoring will become more sophisticated with the ultimate aim to minimise harm to patients. It is likely that robotics will be integrated within the patient’s surgical pathway to reduce human error and optimise efficiency of care. Newer drugs will be synthesized with fewer adverse effects and complications. Indeed, xenon, a noble gas already used in headlamps and lasers, has been found to possess many of the properties of an ideal inhalational anaesthetic agent, albeit prohibitively expensive in cost at the time of writing. The most elusive code to crack has been the answer to a very simple question: ‘how do general anaesthetics work?’ Initial hypotheses like the Meyer-Overton correlation, were thought to be too simplistic and more recent work points towards the involvement of more specific central nervous system protein receptors, such as GABAA and NMDA. Once more is discovered about the mechanism of general anaesthesia at a cellular level, new anaesthetic drugs could be synthesized with safer therapeutic profiles and, perhaps, even targeted to individual patients according to need.

Featured image credit: ‘The device hospital surgery’ by sasint. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post The modern marvel of medicine appeared first on OUPblog.

Tending the roots: a response to Daniel Kerr

Here at the OHR blog we love a good origin story, where we get to hear firsthand how one of our colleagues fell in love with oral history, and how they use their own backgrounds and experiences to inform their practice. Sometimes, the people we hear from are drawn to oral history because it’s a place “where history really matters.” Sometimes oral history sits at an interesting intersection, a good place from which to hope. Other times, oral history is a way to build something meaningful from a disaster. Today we hear from Allison Corbett, who explains her own radical roots and why it’s important to acknowledge the diverse experiences that enable us to listen to each other.

As a young person, I spent several hours a week learning with a group of immigrants who did maintenance work at a local golf course in Virginia. Supposedly, I was helping them learn English. I did do some of that. A lot of what I did, though, was learn. Their lives, which transpired alongside my own upper middle class white existence in my hometown, were composed of realities about which I had no idea before.

Shortly after I started to get to know these workers the local professor who was facilitating this experience introduced me to the work of Paulo Freire. Freire’s work shifted my understanding of the work that I was doing, and transformed my understanding of exchange across power differences. It taught me that any sound analysis of social in/justice and vision for lasting change must come from those directly affected.

When I went to college I continued to run adult English classes, and also began to volunteer as a community interpreter. Years later, when I began to do oral history work, I did so with these foundational experiences in mind. Freire’s approach to popular education, which I contemplated through my weekly sessions in college, and later as a facilitator at a neighborhood community center in Chicago, greatly influenced my framework for working with people in oppressed communities. It helped fuel my own curiosity about what other people made of their lives and realities, and it gave me a critical lens with which to view so much of the “helping work” I saw around me.

The popular education center where I worked in Chicago had roots in Freirian philosophy, but was also founded by Myles Horton’s daughter, Amy Horton, and so was infused by the learning circles of the Highlander Folk School. I eventually left the world of adult education, but I did so to pursue the same principles and ethics that grounded my work there: a belief that people’s stories matter, and that when people are given space and encouraged to tell their stories and analyze them together, community transformation can be possible.

My work now straddles the worlds of interpreting and oral history. Both are specialized forms of listening and transmitting stories across difference. Both have the power to support self-determination and societal transformation. The current incarnation of this dual practice for me is The Language of Justice, an oral history project documenting the stories of interpreters who facilitate multilingual movement building across the country, a practice and ethic known as “language justice.”

These interviews have also brought me full circle back to popular education. One of the first places in the US to intentionally create multilingual grassroots spaces and train social justice interpreters was in fact the Highlander Center for Research and Education, formerly known as the Highlander Folk School.

While conducting interviews for the Language of Justice, I traveled to Highlander for the first time and met with others who now facilitate language justice circles in Western North Carolina. I was humbled and honored to be reminded of the traditions that originally sent me off in the direction of oral history as well as the deep listening that these practitioners were engaging in as part of their work.

He also reminded me that as I and others seek to engage with communities beyond the archive, and often wring our hands about what good it can do to “just” stimulate dialogue in the pursuit of some abstract embodiment of “empathy,” there are generations of folks out there who have been using storytelling and listening as the basis for deep-rooted community change, to whom we can turn to for example.

Shortly after returning from my visit to Highlander, I sat down to read Daniel Kerr’s article: “Allan Nevins is Not My Grandfather: Radical Roots of Oral History Practice in the United States.” I was already pondering the roots of popular education in my own oral history work, but the article helped demonstrate that these roots were critical to the development of the radical oral history practice that I aspire to.

Kerr affirmed what I felt to be true in my own path to oral history. He also reminded me that as I and others seek to engage with communities beyond the archive, and often wring our hands about what good it can do to “just” stimulate dialogue in the pursuit of some abstract embodiment of “empathy,” there are generations of folks out there who have been using storytelling and listening as the basis for deep-rooted community change, to whom we can turn to for example.

By acknowledging this history, we allow ourselves to make connections with valuable alternatives to the archival, university-focused model that Nevins embodies.

Featured image credit: Photo by Allison Corbett, unidentified artist, La Estación Vieja, La Plata, Argentina, 2014.

The post Tending the roots: a response to Daniel Kerr appeared first on OUPblog.

The contemporary significance of the dead sea scrolls

Many people have heard of the Dead Sea Scrolls, but few know what they are or the significance they have for people today. This year marks the 70th anniversary of the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, and it gives us an opportunity to ask what are these scrolls and why they should matter to anyone.

The Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered in 1947 and consist of 900 plus copies of Jewish manuscripts of biblical books, sectarian compositions, and other writings. Several of these scrolls are thought to belong to a Jewish sect or school of philosophy called the “Essenes” who lived two thousand years ago. Some of these Essenes once resided at the site now called the ruins of (khirbet) Qumran, close to the location of the eleven caves where scrolls were found. Recently, there was an announcement of the discovery of the “12th Dead Sea Scrolls cave”, but the evidence of an uninscribed scroll fragment, linen wrappings, and pottery shards found in the cave is insufficient to support the claim.

The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls has often been hailed as “the greatest manuscript discovery” for the scholar, but what significance do they have for the public? When the scrolls were first discovered, public interest was particularly piqued when it came to the light that the scrolls might shed on the origins of Christianity. Theories that posited a direct connection of the scrolls to Christianity, especially the messianic belief in Jesus, grabbed the headlines.

These sensationalist claims, however, turned out to be unpersuasive and highly speculative. It is now widely recognized that the communities reflected in the scrolls and the earliest followers of Jesus belonged to a subset of ancient Jewish society that shared ideas, cited the same biblical texts, and used the same terminology, all the while giving them different meanings. They are various groups that belonged to the sectarian matrix of late Second Temple Judaism.

More recent scrolls scholarship has also emphasized the Jewishness of these manuscript finds. They show that legal and interpretative traditions found in later Rabbinic Judaism were already present in Jewish writings before the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple by the Romans in 70 CE.

The contemporary significance of the Dead Sea Scrolls, however, lies not in the association to early Christianity and Rabbinic Judaism, but to the Bible. The Old Testament or Hebrew Bible is the canon of sacred scriptures of Jews and Christians alike, and it is also highly respected by Muslims.

There are some 220 biblical Dead Sea Scrolls that give us unprecedented insight into what “The Bible” was like two thousand years ago, and underscore the point that the writing, transmission, and selection of the books of the canon was a thoroughly human activity. Despite the claim of divine inspiration by communities of believers, then and now, the Bible did not drop down from heaven, nor is it inerrant as assumed by fundamentalists of different faiths. The composition of each book of the Bible grew over centuries as it was revised and transmitted by groups of anonymous scribes.

The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls has often been hailed as “the greatest manuscript discovery” for the scholar, but what significance do they have for the public?

Before the first century CE, the biblical books were characterized by textual fluidity. There were different versions of a particular book. For instance, there were two versions of the same prophecy of Jeremiah, differing by as much as 14% with varying internal arrangements of the oracles. Other examples include the addition or absence of phrases and clauses, large and small, in the corresponding biblical texts.

The sectarian communities reflected in the scrolls were not troubled by the textual variants of their biblical texts. They saw different readings of the same biblical text to be indicative of the many meanings of scriptures that they considered authoritative.

The sectarians also did not have a clear delineation of the boundary between “biblical” and “non-biblical” books. For them, authoritative scriptures consist of the traditional biblical books, but also other ones that were left out of the Protestant and Jewish canons, but included in the Catholic and Orthodox canons (e.g. book of Jubilees, book of Enoch). Moreover, there were other scriptures, not included in any contemporary canon, that they considered authoritative.

Featured image credit: Dead Sea Scroll Bible Qumran Israel by Windhaven1077. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The contemporary significance of the dead sea scrolls appeared first on OUPblog.

April 13, 2017

Louder isn’t better, it’s just louder: what eighteenth-century performance practice teaches about dynamics

To the modern player, when dynamic indications are found in the score, the typical reaction is to think in terms of changes in volume. Not entirely true for the eighteenth-century musician – dynamic indications mean much more than loud or soft. Volume shift was only part of the story and was a rather new and novel concept that took hold with the advent of the fortepiano and its ability to quickly alternate from loud to soft. According to the Harvard Dictionary of Music, the use of abbreviations to indicate dynamics appeared as late as 1638. Notated dynamic markings came into their own during the rise of the fortepiano and its expanded capabilities.

From early Haydn to late Beethoven we see the frequency of use increase and more varieties of indications come into play. Crescendo and diminuendo were developed and exploited at the renowned Mannheim School and modern use notation appeared later, in 1739.

Interestingly, C. P. E. Bach and D. G. Türk speak very little about dynamics in their tutors. Bach writes about only three terms: p, mf, and f. Türk defines ff, f, mf, p, and pp. What they do speak to at great length is affekt, the foundational pillar for eighteenth-century style. Affekt is the ability of music to stir emotions. It was achieved through attention to detail and proper execution, including execution of dynamics.

The novelty of the fortepiano wasn’t the extreme range of volume as we know today, but its ability to quickly alternate and facilitate finesse. Forte and piano are associated with a deeper meaning behind the marking. Consider forte to possibly portray heavy, wide, broad, angry, anxious, big, or strong; piano to portray light, sweet, pleading, sorrowful, or melancholy. The make-up of the fortepiano allows these characters to be expressed beautifully. When this understanding is applied to the repertoire, the results become quite exciting:

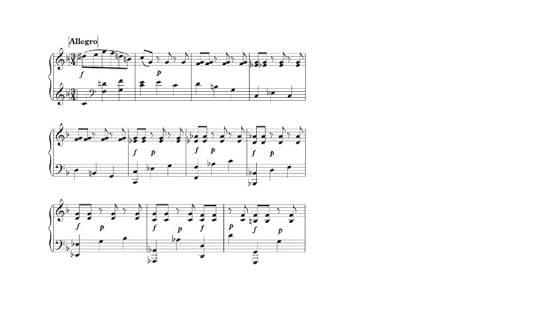

Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 332/I, mm. 55-65 (Henle)

Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 332/I, mm. 55-65 (Henle)Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 332/I, mm. 55-65 (Henle)

It can be achieved effectively on the modern piano when appropriate adjustments are made:

Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 332/I, mm. 55-65 (Henle)

Forte and piano are the backbone, indicating more and less rather than an absolute extreme loud or soft. It provides the means to shading and nuance. And it should be done in good taste, which requires further understanding of proper practices of the time.

Forte followed by piano is not necessarily an absolute direction for the notes specifically under the marking until the next change, but serves as a guide for dynamic direction from one marking to the next based on melodic, harmonic, and contextual clues. In the example below, direction is from forte to piano rather than an absolute forte on beat 1 that continues until piano on beat 2. The performer should start forte and arrive at piano by beat 2.

Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 309/II, mm. 17-19 (Henle)

Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 309/II, mm. 17-19 (Henle)Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 309/II, mm. 17-19 (Henle)

Forte directly followed by piano is often declarative in nature. The breadth is determined by affekt. We turn again to Mozart for clarification. The marking may be expressive:

Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 280/III, mm. 55-59 (Henle)

Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 280/III, mm. 55-59 (Henle) Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 280/III, mm. 55-59 (Henle)

Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 280/III, mm. 55-59 (Henle)Or it may give direction for a terraced crescendo or diminuendo. Here, the line builds bit by bit, leading up to the forte at the peak of the line.Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 280/III, mm. 55-59 (Henle)

Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 309/I, mm. 48-51(Henle)

Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 309/I, mm. 48-51(Henle)

Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 309/I, mm. 48-51(Henle)As understood practices are incorporated it is important to remember that the overriding goal is to express affekt and dynamic markings are one of many notational clues provided by the composer to guide the performer in achieving the desired affekt. Once the clues are uncovered and adjustments are made in translating the affekt from fortepiano to modern piano, the musical message can be carried quite effectively. From the context of the piece, determine how and to what extent the dynamic marking(s) will best describe the affekt the composer is portraying.Mozart, Piano Sonata, K. 309/I, mm. 48-51(Henle)

Listen carefully to make artistic adjustments. Guard against playing loudly simply because there is an f in the score. When considering extreme f or p, remember the volume capabilities available on the fortepiano. As Malcolm Bilson suggests, playing “as if” the modern piano is a fortepiano will go a long way in achieving the goal. Making appropriate adjustments on the modern piano will bring authenticity to the performance. The modern piano requires time for the tone to develop. Listen with a discerning ear to avoid cutting the sound off too quickly and creating a choppy, undesirable effect.

Continually consider the intended affekt, how the piece was probably performed on the period instrument, and how that intention can be best realized on this instrument. In doing so, playing will no longer simply be loud or soft, but an organic, living expression of the soul.

Featured image: “Piano, Hands, Music, Instrument” by Clint Post. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Louder isn’t better, it’s just louder: what eighteenth-century performance practice teaches about dynamics appeared first on OUPblog.

Managing stress: perspective

Stress and anxiety are often partly a result of your perspective, or how you tend to think about challenging situations you face. You can learn to regulate stress and anxiety by changing the way you think. This is because excess worry and stress often come from overestimating the danger in a situation.

This overestimation is referred to by psychologists as “catastrophizing” and can take one of two forms:

Thinking the likelihood of the feared event actually happening is greater than it really is, or

Thinking the feared event will be worse than it really is.

To catastrophize less, stop and answer these questions in more realistic ways:

Q: What’s the likelihood of this feared event actually happening?

A: The odds of this plane (car) crashing on this particular flight (trip) are less than one in a million, so why waste time worrying?

“If the feared event actually happens, how terrible will it really be?”

Q: If the feared event actually happens, how terrible will it really be?

A: If I fail at this task, it will seem important today, but in the big picture it’s really not that important. In a year or two, this will probably be just a distant memory.

A: If this person doesn’t like or respect me, it’s not the end of the world. No one is liked and respected by everyone.

As these examples show, the thoughts you choose to focus on can lower the intensity of your worry and stress.

Focusing on positive coping statements instead of adopting a helpless attitude can reduce worry and stress. Here are some more examples of helpful, stress-reducing thoughts:

I’ve survived many tough situations, and each one has made me tougher. I’ll get through this one and end up even stronger.

Even though I’m not perfect, I still love and respect myself. Perfection is an unrealistic and unhealthy goal.

There are many possible explanations for this symptom. I’ll get it checked out, but in the meantime, I won’t catastrophize about it. It’s normal to feel fear in this situation; I’ll just practice some relaxation techniques to stay a little calmer.

Fear is just an emotion that will pass.

Avoiding fearful situations will make my fears stronger, but facing my fears will eventually reduce their power over me.

Shifting your perspective can also be helpful when you are faced with a seemingly overwhelming set of responsibilities. If you feel overburdened by responsibilities at work or at home, take some time to prioritize goals and consult with your supervisor or family members to set more realistic expectations.

Also examine your goals to see which of them could be delegated to someone else. Is there anyone kind enough to help you out if you ask them? Can you afford to pay for help? If you just didn’t do something, would someone else step in and take care of it?

In addition to prioritizing goals and delegating or eliminating some that are not essential, it’s also smart to manage stress by subdividing big goals into smaller ones. Breaking bigger goals into smaller steps can help you feel a sense of accomplishment as you complete each step. Making “to-do” lists can also help to organize and manage your responsibilities.

There are several ways to better manage stress and anxiety. One of the most effective ways is to change your perspective, or the way you tend to think about situations. Be on the lookout for a tendency to catastrophize and practice talking to yourself in more realistic ways. Frequently, stress is the result of taking on more tasks than you have the time or other resources to accomplish. Stress management therefore requires careful examination and prioritization of goals. Goals towards the bottom of the priority list may need to be let go, delegated, or put on hold.

Featured image credit: Home by Mysticsartdesign. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

The post Managing stress: perspective appeared first on OUPblog.

French hovels, slave cabins, and the limits of Jefferson’s eyes

Thomas Jefferson was a deliberate man and nothing escaped his attention. Jefferson‘s eyes were powerful, lively, and penetrating. Testimonies swore that his eyes were nothing short of “the eye of an eagle.” He wore spectacles occasionally, especially for reading, but his eyes stood the test of time despite physiological decline. “My own health is quite broken down,” he wrote on 3 March 1826 to Robert Mills, the architect who designed the obelisk for the Bunker Hill monument. Mostly confined in the house, Jefferson proclaimed, “my faculties, sight excepted are very much impaired.”

Jefferson’s powerful eyes constantly dissected and analyzed: especially for scientific reasons, Jefferson spied on people’s lives. He always wanted to see, and to see firsthand. During his famous tour of southern France and northern Italy in the spring of 1787, he saw examples of misery and wretchedness—especially where lower classes were concerned. He had entered the shacks of French peasants incognito. To peep into people’s dwellings was for Jefferson the best method to assess their identity and evaluate their circumstances. “You must ferret the people out of their hovels as I have done,” Jefferson wrote to his friend Lafayette, “look into their kettles, eat their bread, loll on their beds under pretence of resting yourself, but in fact to find if they are soft.”

Most likely, this Jeffersonian method of spying did more than just provide reliable sociological data: it enhanced his empathy. Reading this letter to Lafayette, the reader gets the impression that Jefferson drew himself closer to these hapless human beings, pitying them and caring for their conditions, seeing them for who they actually were. But in other ways, Jefferson’s eyes were blind: did he ever actually see his slaves’ cabins? Did he ever ferret slaves out of their shackles to observe and meditate about their condition?

Jefferson Memorial in Washington D.C. with excerpts from the Declaration of Independence in background by Rudulph Evans, photo by Prisonblues. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Jefferson Memorial in Washington D.C. with excerpts from the Declaration of Independence in background by Rudulph Evans, photo by Prisonblues. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Most of Jefferson’s slaves were confined in cramped living quarters, leading lives undoubtedly worse than those led by French peasants. But there is no clear trace of empathy on the part of Jefferson for his slaves. His correspondence, his memorandum books, and especially his farm book show us how Jefferson consistently saw his slaves—at least the huge majority of them. Black bodies are usually crouched to perform vile doings; they are dirty, their faces often bear a hideous grin, and their countenance is disfigured by hard labor. By and large, Jefferson covered black bodies in “negro cloth,” rough osnaburgs, coarse duffels, or bristly mixtures of hemp and cotton.

In respect to African-American slaves, Jefferson’s eyes were myopic at best. Perhaps this was a personal fault, or perhaps this eighteenth-century man was simply hindered by the peculiar institution in which he was reared. But some slaves at Monticello led deliberate lives and exerted a lot of effort to appear different. In the slave cabins on Mulberry Row, especially those occupied by the large Hemings family, we catch a glimpse of what kind of differentiated selves Jefferson’s luckier “servants” were trying to preserve.

Jefferson’s last great-grandchild, Martha Jefferson Trist Burke, was impressed by just that kind of self-making when she visited John and Priscilla Hemings‘s cabin. Little Martha was less than three years old when she saw what her great-grandfather’s eyes had probably never noticed—that African-American slaves obviously liked cleanness, tidiness, and little comforts. Amid the oppression and relative material deprivation of their situation, many slaves succeeded in performances of dignity. Whenever possible, they stepped outside of spaces in which they were forced to perform utilitarian functions, such as kitchens, laundries, and privies, and moved on a private stage of their own choice, with character, decorum, and full-fledged humanity. “I remember the appearance of the interior of that cabin,” Martha wrote in her journal, “the position of the bed with it’s [sic] white counterpane and ruffled pillow cases and of the little table with it’s [sic] clean white cloth, and a shelf over it, on which stood an old fashioned band box with wall paper covering, representing dogs running, this box excited my admiration and probably fixed the whole scene in my mind.”

Did Jefferson ever see such intimate details of the lives of his slaves? Realizing the immense symbolic and existential power represented by the decorative objects and cleanliness Martha saw would have emotionally devastated him. Peeping into the coziness and dignity of the Hemings’ cabin might have provided Jefferson with extra reason to amend his racial hierarchies. Some black bodies, within Jefferson’s own plantation, created their own backgrounds of white clean cloth and improvised petit bourgeois coziness, delicacy, and “femininity.” It’s doubtful that Jefferson ever enlarged his observations of these ill-fated persons, discovering the wider dimensions of African-American corporeal and spiritual identity.

Again, we have no conclusive evidence of Thomas Jefferson using his keen eyes to empathize with the oppressed people who immediately surrounded him. A big chapter on the “negro” fashion, their style and taste, seems to be missing from Jefferson’s records. We will never know if Jefferson’s eyes ever grasped the liberating, creative power couched in simple pillows, white counterpanes, clean white tablecloths, and boxes covered with paper on which decorative dogs ran.

Featured image credit: Monticello from the west lawn by YF12s. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post French hovels, slave cabins, and the limits of Jefferson’s eyes appeared first on OUPblog.

French politics at the crossroads

The outcome of France’s upcoming presidential elections may be the most difficult to predict in many years. The name of the anticipated winner has changed several times over the past few months. The conservative party’s primary election ejected several seemingly credible candidates from the race. The far-right populist party Front National has become the leading party in terms of vote share at the regional elections of 2015, and its president Marine Le Pen is more popular than ever. The Socialist Party, which was bound to experience a humiliating defeat in 2015 has suddenly started hoping again. And the former Minister of the economy, Emmanuel Macron, though not supported by any major party, has looked more and more like a credible contender. In the light of such uncertainty, media pundits have been refraining from making any further guesses in recent days.

Whatever the result, this election is likely to profoundly reshape the French political landscape. The current party system looks poised for a forceful reorganization. The steady progress of the Front National and the decline of traditional government parties are increasingly clear, probably questioning the very foundations of the French 5th Republic. A rethinking of the current institutional setup may be necessary.

An open electoral race

Several major issues or stakes have dominated the news in the first few months of the campaign. First, the conservative party, Les Républicains (LR), organized open primaries for the first time at the end of November. Former Prime minister François Fillon’s large victory over initially more popular candidates came as a surprise. However, a series of controversies, especially regarding the alleged fictitious employment of his wife and two of his children have weakened his bid – maybe fatally. He remains nonetheless one of the most credible contenders for the time being.

On the left, for a long time the major question was whether François Hollande would stand for re-election. When he announced on December 1st that he would not – a first in the 5th Republic – a new race started, culminating in the equally surprising victory of party left-winger, Benoît Hamon in the Socialist primaries at the end of January. He will be up against Jean-Luc Mélenchon, who is supported by the Communist Party and the Parti de Gauche, who is likely to maintain his presidential bid nonetheless.

Finally, the main players of this presidential election may be none of the above. Marine Le Pen is widely expected to top the poll at the first round of the presidential election in late April, though a victory at the second ballot remains unlikely – so far. The real question is who will be facing her.

At the time of writing (mid-February), it looks as though newcomer Emmanuel Macron stands a serious chance of taking up that role. As the dynamics of primaries have pushed left-wing and right-wing candidates towards the extremes, his economically and socially liberal positions have won the support of large sections of middle-class center-left and center-right voters. In the event of a run-off between him and Marine Le Pen, there is little doubt that he would obtain an overwhelming victory.

Whatever the result, this election is likely to profoundly reshape the French political landscape.

A changing party system

Beyond those short-term considerations, these elections illustrate several long-term trends. France is facing a series of major challenges regarding the future of its economy, but also its welfare state. In this context, successive governments’ stances with regard to European integration have become more and more erratic, as they have in other areas, too. It is probably the contradiction between the tradition of “grand politics” and the reality of ever greater international interdependence that is today challenging classical political parties.

This is visible in the evolution of the party system and, more generally, political representation in France. New issues are dominating political competition and are profoundly affecting electoral dynamics. Issues such as the impact of globalization and Europe are playing an ever greater role in the domestic political debate, fueling the importance of identity-politics.

The outcome of the upcoming presidential and legislative elections may thus completely upset the political status quo. The danger is great for the two historical political blocks to be dramatically weakened and to enter a period of profound crisis.

The need for rethinking French political institutions

Looking at the elections and related political trends may not be enough however. We have shown elsewhere that France is engaged in a vicious circle of political alternation and subsequent disappointment that has been ongoing for decades now. It is the results from of an institutional setup that creates a very powerful, but politically irresponsible president. The latter dominates a Parliament which -despite some recent improvements – remains politically weak. Expectations are exceedingly high among voters, fueled by candidates who do not hesitate to make spectacular, albeit unrealistic pledges. The institutionalization of primaries has added further complexity to an already complex game. Even if the 2017 elections end up maintaining a fragile status quo – e.g. by leading to the election of a socialist or, more likely, a conservative (i.e. Republican) candidate – there is clearly a need to rethink the underlying logic of French political institutions. A move towards a more consensual political system should dampen expectations, create less frustration and reduce the appeal of populist solutions. But it may take a profound crisis to raise awareness about these problems. 2017 may become a crucial year in the history of French democracy.

Featured image credits: LEWEB 2014 conference in conversation with Emmanuel Macron by Offical LEWEB photos. CC-BY-2.0 via Wikimedia Commons; François Fillon at the UMP launch rally of the 2010 French regional elections campaign in Paris by Marie-Lan Nguyen. CC-BY-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons; Marine Le Pen by Foto-AG Gymnasium Melle. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post French politics at the crossroads appeared first on OUPblog.

Public attitudes to the police

What do the public think of their police? This is a rather more complicated question than it appears. When public opinion polling was in its infancy, people were asked how they felt about ‘the police’, but it was realised that this tapped only very general attitudes towards the police institution and not necessarily opinions about the behaviour of officers. The intervening period has witnessed an increasingly specific focus on how people feel about officers and their behaviour. But, whether someone is satisfied or not with how officers have behaved is not necessarily because of how they were treated: might it reveal a perceptual bias of the individual member of the public, or perhaps the peculiar circumstances under which they encountered the police?

This uncertainty can only be resolved by burrowing down to how people at large view what cops do when dealing with an incident. We aimed to answer this question by presenting 34 focus groups with video–clips lasting, on average five minutes, showing encounters between police and members of the public. These encounters involved officers acting in their law enforcement role: investigating an alleged robbery of an elderly man by a knife–wielding intruder into the man’s home; an officer dealing with a situation where three young men were breaking into a car in a supermarket car park, claiming that this was at the behest of the owner; the arrest of the young driver of what officers believed was a stolen car; and the forceful arrest of an ‘aggressive man’ outside a nightclub late at night. We played each clip in turn and invited those present to freely discuss their assessments.

Focus groups represented a broad range of interests and purposes and were drawn from throughout the ‘Black Country’ region of the West Midlands; an area of deprivation and ethnic diversity. They had no inhibitions in expressing and defending their opinions, which seemed not to fall into any of the neat categories of ethnicity, class, age, gender, etc. Indeed, within any discussion of a particular video–clip, our participants were as likely to express both positive and negative evaluations. The only topics on which our focus groups agreed were the topics that aroused controversy.

The only topics on which our focus groups agreed were the topics that aroused controversy

Those flashpoints of controversy were dominated by two themes: suspicion and use of force. Did our participants feel that officers were entitled to be suspicious of the member of the public? Did our participants feel that they used force necessarily and proportionately? Our focus groups were divided on these questions, often not only because of what they had witnessed from the video–clip, but what they imagined had happened, was happening and was likely to happen in future. Surprisingly, four focus groups of police officers (of all ranks) were just as divided as those they policed and agreed on the issues raised.

So what did we glean from our experience? The obvious conclusion was that policing arouses intense controversy. Such controversy was not aroused by incidental features of the police role, but goes to the heart of police powers — forming suspicions and using force. There was little evidence that particular groups were instinctively ‘pro’ or ‘anti’ the police. In the vast majority of groups people approved of some aspects, but not others. How they formed judgements often relied on imagination as much as upon anything the officer did or did not do.

This has profound implications for the police and the wider criminal justice system. There is no simple template that the police can follow to ensure public acceptability. There is no stable constituency who approve of what they do, nor a hard core of those who disapprove. Doing their duty is as likely to provoke animosity in some and praise in others. Instead of trying to achieve the elusive prize of increased public acceptance, police need to recognise that policing is inherently controversial, and manage it. This requires engagement and talk, which requires that police embrace the contradictions and dilemmas of policing openly and honestly. For instance, police should be more aware that investigation is never a morally neutral exercise, since police must regard an allegation of wrongdoing as sufficiently credible as to warrant investigation. ‘He must have done something to attract police attention’. Likewise, using force is rarely a clinical exercise: it is physically arduous to subdue even minimally resistant people and the struggle that often ensues often becomes an unseemly spectacle. As police focus groups agreed, ‘It doesn’t look good!’ Perhaps training could make it look better, but that takes officers off the streets where the public demands to see them. To engage with controversy could, at least, elevate public debate.

Featured image credit: London October 19 2013 078 Police BX59CHG by David Holt. CC-BY-SA-2.0 via Flickr.

The post Public attitudes to the police appeared first on OUPblog.

April 12, 2017

The sins of my etymological past and other people’s sins: Part 1

This blog was launched on 1 March 2006, four or even five editors ago (to paraphrase Kurt Vonnegut’s statement about his wives), and is now in the twelfth year of its existence. It has been appearing every Wednesday since that date, and today’s number is 587. At the beginning (perhaps I should even say in the beginning), the format of the essays was not clear to me (or to anyone), and the initial agreement was to limit the text to one computer page. Later, the standard length of the installment doubled, and still later illustrations appeared. (Hardly anyone ever comments on our picture gallery, and yet finding them is a full time job for me and the editors.) Quite a few posts I wrote in 2006 and 2007 I would very much like to rewrite, partly because of the journalistic experience I have gained and partly because today I usually know more about the subjects I chose at that time. On 8 March 2006, I discussed the origin of the word sin. Since 2006, in connection with my research into the origin of Icelandic sagas and the working of the medieval mind, I have read hundreds of pages about truth and lie in old and medieval societies and, no longer limited by approximately 600 words, would like to return to that subject. All of us are sinners, so that the topic may interest not only those who care about etymology and historical linguistics.

The word sin is old in English, but its present day sense “transgression against divine law, offense against God” appeared only with Christianity. Since literacy came to the “barbarians” with the conversion, the extant texts have most instances of sin only in its now familiar context, but the old state of affairs is not entirely lost. In the Old English poem Beowulf, the alliterating phrase synn and sacu “wrongdoing and strife” appears, and it has analogs elsewhere in Germanic. “Sin,” it appears has always meant “offensive act, crime,” though in the secular rather than religious sense. The cognates of sin have d or its reflex (continuation), as evidenced by German Sünde, but this d was not part of the root. Especially characteristic is Old Icelandic syn or synn, usually believed to be a borrowing from West Germanic. The word was feminine and meant “denial,” not “crime.” Its plural meant “trouble.”

Syn and sacu.

Syn and sacu.In the thirteenth century, an Icelandic book called Edda appeared. (This is the so-called Prose Edda, different from the Poetic Edda, a collection of mythological and heroic songs, also produced in the thirteenth century.) The Prose Edda is traditionally attributed to the great historian and politician Snorri Sturluson. Part One of the book contains the main pagan myths of medieval Scandinavia. One chapter offers a short catalog of female divinities. It looks odd to the modern reader. The impression is that Snorri derived some words of his language from the names of the goddesses, rather than going in the opposite direction. The passage that interests us runs as follows: “The eleventh [goddess] is Syn; she guards the door of the hall and shuts it against those who are not to enter. She is also appointed defending counsel at trials in cases she wishes to refute; hence the saying ‘Syn is brought forward’ when anyone denies accusation.”

To us Syn is a personified abstraction. To Snorri she was the “begetter” of the abstraction. However, his attitude need not bother us. The relevant fact is that syn means “denial of an accusation,” rather than “crime, transgression.” This reversal is of paramount importance. First, we notice that sin (and the same holds for its cognates) is a legal term. Second, we look around and find the least expected cognates of sin, syn, and the rest. One of them is Engl. sooth, as in forsooth, soothsayer, etc. (The word sooth means “truth).” At one time, the root had –an– in the middle. Later, n was lost, a was lengthened, to compensate for this loss, and ā [long a)] changed to ō [long o]. Hence the spelling oo in sooth; the value of the present day vowel is due to the Great Vowel Shift, as in school, moon, and others. The verb soothe likewise meant “declare to be true; confirm, encourage; please or flatter, gloss over,” and, only beginning with the seventeenth century, “mollify”; still later, the modern meaning “to assuage” became the usual one.

Old Icelandic sanna also meant “assert, prove”; the closest cognate of sooth was Icelandic sannr. Gothic sunja (possibly a noun), recorded once in the feminine, meant the same. (The Gothic Bible was written in the fourth century.) We feel totally confused: How can the words for “true, truth” be related to sin? The plot thickens when we learn that Icelandic sannr meant both “true” and “guilty.” But the crushing blow comes with the discovery of Latin sunt, the third person plural of the word “to be”; German sind is close enough. Our least trouble is the vowel alternation: a in sannr and u in sunt (y in syn is ü, that is, the umlaut of u; the sound that caused umlaut is no longer present in this form). The vowels a and u alternate by ablaut, the process referred to and even discussed more than once in this blog; see, for example, the gleanings of January 2017).

Thus, we confront the knot: “being, existent,” “true,” and “guilty.” Etymologists have been trying to unravel this knot for nearly two centuries, and, on the whole, they were successful (or let us say, not quite unsuccessful). I will report on their endeavors next week, but a few preliminary remarks are due today. We look upon truth as a set of facts or statements corresponding to reality. In the remote past, this view of truth must, naturally, also have existed, but the concept of being was inextricably connected with the idea of proving one’s innocence, or denying guilt (“sin”). The same root s + a vowel + n(t) served the purpose of uniting “existence,” “truth,” and “guilt” very well.

Stick, stock, and stuck. Nothing illustrates ablaut better than stock photos.

Stick, stock, and stuck. Nothing illustrates ablaut better than stock photos.Ablaut took care of differentiation, as it did in all other cases. The “real” root was snt. It is hard to show the workings of the extremely efficient mechanism of ablaut in English, where mainly verbs follow its model, as in rise—rose—risen, bind—bound, come—came, and in pairs like sit—set and lie—lay. Late sound changes have so disfigured most words’ initial shape that the original scheme is hard to follow. However, stick and stock are an example of the same mechanism (the nouns are related by ablaut). I am almost tempted to write stick—stock—stuck. In German, the picture is clearer. Take the verb trinken “to drink.” Its principal parts are trinken—trank—(ge)trunken. Each form represents a certain grade of ablaut, here i, a, and u, and from the last two we have nouns meaning “a drink”: Trank and Trunk. Engl. drunk and the full participle drunken resemble getrunken. Especially elegant is the so-called zero grade: compare Engl. ken and Latin gnostic. There is no vowel between g and n: this is zero in all its beauty. The Indo-Europeans fought for their innocence with the sound complex snt. Next week we’ll see how they progressed from “sinning” to being (without quotes).

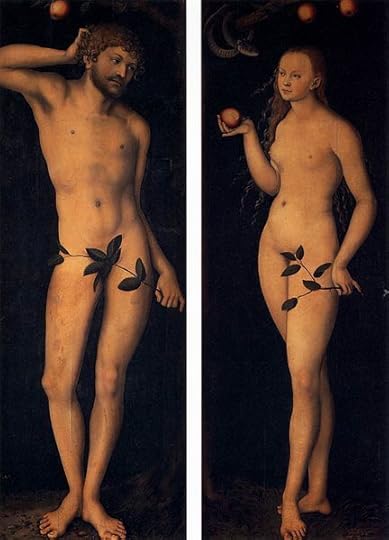

The original sin. But the forbidden fruit is unlikely to have been an apple.

The original sin. But the forbidden fruit is unlikely to have been an apple.Image credits: (1) “Playful Tussle” by Ritesh Man Tamrakar, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr. (2) “Walking Stick” by Wellcome Images, CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (3) “Matthiola longipetala” by E rulez, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. (4) “stuck in the mud” by devra, CC BY 2.0 via Flickr. (4) “Adam and Eve” by Lucas Cranach the Elder, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. Featured image credit: “God admonishing Adam and Eve” by Domenichino, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The sins of my etymological past and other people’s sins: Part 1 appeared first on OUPblog.

Ignorance as an excuse

Despite unequivocal scientific evidence for anthropogenic climate change, many people are skeptical that climate change is man-made, or even real. For instance, lawmakers in North-Carolina passed a bill requiring local planning agencies’ to ignore the latest climate science to predict sea level rise in several coastal counties, while the Energy Department’s climate office bans the use of the words climate change.

They say that ignorance is bliss, but why would we not want to know useful information? One important reason is that knowledge can be threatening if it pits our selfish impulses against a greater social good. This is because our actions are a window through which we can observe and judge ourselves. Armed with a complete picture of the consequences of our actions, we might have to trade off liking what we see with getting what we want. Ignorance, on the other hand, provides a nice excuse to avoid such conflict. As a case in point, people report the “fear of being a bad person” as a reason to avoid knowing about difficult tradeoffs associated with climate change.

The usefulness of ignorance turns up not only in the context of climate change, but anytime we suspect there might be a conflict between our selfish impulses and a broader social benefit. We suspect that there are drawbacks to the consumption of cheap meat for the environment and animal welfare, but because we like to eat meat and do not want to pay too much, we look the other way. The financial crisis of 2008 was partly the result of similar tendencies. The movie The Big Short (2016) shows how bankers and investors happily avoided deeper investigation of dodgy mortgages in order to benefit from their trades, while consumers were eager to sign contracts that were too good to be true.

Willful ignorance in the lab

Evidence from the laboratory provides further proof that financial incentives may lead to “willful ignorance.” An experiment by Dana, Weber, and Kuang (2007) illustrated the stark contrast between how we behave when we are well informed about the consequences of our actions and how we behave when the link between action and consequences is less clear, as well as our willingness to avoid opportunities to become better informed.

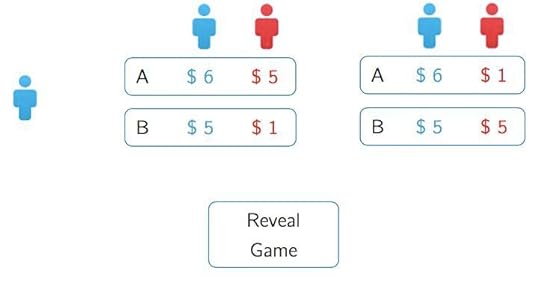

A participant (shown in blue in the figure below) had to divide money between himself and another passive participant (in red). In the situation on the left, the choice is simple: Option A provides both participants with more money than option B. In the situation on the right, the choice harder: Option B is fairer, but requires the blue player to sacrifice a dollar. If subjects were simply told that they were in this situation, about three quarters of the blue players chose to make that sacrifice.

Figure: Schematic representation of the experiment by Jason Dana and co-authors by Zachary Grossman and Joël J. van der Weele . Used with permission.

Figure: Schematic representation of the experiment by Jason Dana and co-authors by Zachary Grossman and Joël J. van der Weele . Used with permission.The crux of the experiment came in a different condition, in which the investigators did not tell subjects which situation they were in. However, the BLUE player was told that she could find out with a mouse click on the “Reveal Game” button. An easy choice one would think, since when fully informed, a large majority of participants made different choices in the two situations. But not so: almost half of the participants remained ignorant, and then chose the option best for themselves (A), with predictably bad consequences for the red participant. The experiment thus shows that although some people would use the information if was given to them, they decided not to acquire it of their own accord, even though it was free.

People are not only imperfectly informed, but also choose their information in a way that best manages their image.

The self-image value of ignorance

But how can ignorance be valid as an excuse when it was chosen deliberately? Willful ignorance is generally considered to be an act of bad faith. In a recent publication, we used an analysis based on a so-called signaling model, to show that opting for ignorance certainly does not send a particularly good signal about yourself. However, the ignorant can plausibly maintain that they would have done the right thing, if only they had known the consequences of their actions. Indeed, as the experiment demonstrates, some people would act pro-socially with full knowledge of the bad consequences if they had information.

The usual analysis of signaling considers interaction between people. However, in this experiment, there was no external audience present to observe whether or not the blue player was informed. Instead, willful ignorance demonstrates the value people place on the image they have of themselves, and the excuse serves to ease one’s own conscience. One way to think about this is that we try to impress a future version of ourselves, and soften its judgment of our own past choices.

Testing the self-image value of ignorance

To test self-image maintenance as the source of ignorance, we did some follow-up experiments. We first replicated the original results, and found an ignorance rate of about 60%. We then tested whether people indeed ascribe actual value to ignorance, by attaching a small monetary reward to the “Reveal Game” button. We found that even in this condition, 46% of our participants remained ignorant. In other words, they were willing to pay to know less.

In another condition, we forced people to show their true colors, so that ignorance could no longer serve the purpose of obfuscating their true preferences. To do so, we asked a group of participants to make a choice for both situations in the experiment. Only then could they press the “Reveal Game” button. Although in this condition information was entirely useless, more than three quarters of participants now pressed the button. In other words, people wanted more information about the choices they had already made, than the choices they had yet to make, a sharp contrast with standard economic theories of rational choice.

All of this paints a rather bleak picture of humanity. To protect our self-image, we leave unwelcome information about the victims of our actions under the carpet. People are not only imperfectly informed, but also choose their information in a way that best manages their image. This helps explain why it is so difficult to wean ourselves off our nasty habits such as the consumption of fossil fuels, cheap meat, and risky mortgages, and why issues like climate change become so polarized. Just establishing a scientific fact is one thing. To make these facts matter, scientists and policy makers will have to grapple with the realities of human psychology.

Featured image credit: three wise monkeys by Robphoto. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Ignorance as an excuse appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers