Oxford University Press's Blog, page 380

April 12, 2017

The role of smugglers in the European Migrant Crisis

Media coverage of the European migrant crisis often focuses on the migrants themselves—capturing their stories as millions escape violent conflicts and crushing poverty.

In Migrant, Refugee, Smuggler, Savior, Peter Tinti and Tuesday Reitano consider the smugglers involved in transporting migrants throughout Europe. Although many smugglers are viewed as saviors, others give little regard to the human rights issues. The excerpt below addresses how European policies limit asylum-seekers and lead them to depend on dangerous underground smuggling networks.

Europe is currently experiencing the biggest mass migration since the Second World War in what has come to be known as the “migrant crisis.” There is a natural impulse—among scholars, journalists, politicians, activists, and concerned citizens—to frame their stories within a broader human rights narrative. They remind us of the unfairness of the world and the injustice of global inequality. What we want to focus on are the smugglers, traffickers, and networks of criminals that make their narratives possible.

These networks, tens of thousands of people strong, are facilitating an unprecedented surge of migration from Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia, and South Asia into Europe. Although the drivers of the current “crisis” are many—including but not limited to the concentric phenomena of conflict, climate change, global inequality, political persecution, and globalization—the actualization of the crisis is enabled and actively encouraged by an increasingly professional set of criminal groups and opportunistic individuals that is generating profits in the billions.

“Syrian and Iraqi refugees arrive from Turkey to Skala Sykamias, Lesbos island, Greece” by Ggia. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“Syrian and Iraqi refugees arrive from Turkey to Skala Sykamias, Lesbos island, Greece” by Ggia. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.Some smugglers are revered by the people they transport, hailed as saviors due to their willingness to deliver men, women, and children to safety and opportunity when no legal alternatives will offer them either. In a neoliberal world where the fates of individuals are couched in anodyne policy-speak, it is often the criminals who help the most desperate among us escape the inadequacy, hypocrisy, and immorality that run through our current international system. It is certainly true that smugglers profit from the desperation of others, but it is also true that in many cases smugglers save lives, create possibilities, and redress global inequalities.

Other smugglers carry out their activities without any regard for human rights, treating the lives of those they smuggle as disposable commodities in a broader quest to maximize profits. For all too many migrants and refugees, smugglers prove unable to deliver, exposing their clients to serious injury or even death. Even worse, some smugglers turn out to be traffickers, who, after luring unsuspecting clients with false promises of a better life, subject them to exploitation and abuse.

Meanwhile, efforts by European policymakers and their allies to stem the flow of migrants into Europe are pushing smuggling networks deeper underground and putting migrants more at risk, while at the same time doing little to address the root causes of mass migration. In lieu of safe, legal paths to seeking refuge and opportunity, new barriers are forcing migrants to pursue more dangerous journeys and seek the services of more established mafias and criminal organizations. These groups have developed expertise in trafficking drugs, weapons, stolen goods, and people, and were uniquely qualified to add migrant smuggling to their business portfolios.

The result has been a manifold increase in human insecurity, not only in the Mediterranean and Aegean Sea crossings, which have received considerable attention in the international media, but also along the overland smuggling routes that cross the Sahara and the Central Asian Silk Road, penetrate deep into the Balkans, and continue into the grimiest corners of Europe’s trendiest capitals.

“A line of Syrian refugees crossing the border of Hungary and Austria on their way to Germany” by Mstyslav Chernov. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

“A line of Syrian refugees crossing the border of Hungary and Austria on their way to Germany” by Mstyslav Chernov. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.What was once a loose network of freelancers and ad hoc facilitators has blossomed into professional, transnational organized criminal networks devoted to migrant smuggling. The size and scope of their operations is unprecedented. Shadowy new figures have emerged, existing crime syndicates have moved in, and a range of enterprising opportunists have come forward, together forming a dynamic, multi-level criminal industry that has shown an extraordinary ability to innovate and adapt.

What we are witnessing is not just the story of traditional migrant smuggling on a larger scale. Rather, we are witnessing a paradigm shift in which the unprecedented profits associated with migrant smuggling are altering long-standing political arrangements, transforming economies and challenging security structures in ways that could potentially have a profound impact on global order.

Furthermore, the consolidation and codification of these networks also means that smuggling networks now seek to create contexts in which demand for their services will thrive. They have become a vector for global migration, quick to identify loopholes, exploit new areas of insecurity, and target vulnerable populations whom they see as prospective clients. They no longer simply respond to demand for smuggler services: they actively generate it.

In order for governments, aid groups, and organizations to better understand how to help refugees, we must get beyond the facile and counterproductive narratives of villains and victims, and we must start by examining smugglers dispassionately for what they are: service providers in an era of unprecedented demand.

Featured image credit: “Refugees on a boat crossing the Mediterranean sea” by Mstyslav Chernov. CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The role of smugglers in the European Migrant Crisis appeared first on OUPblog.

The four college hookup cultures

In their survey of research on hookup culture, Caroline Heldman and Lisa Wade noted that:

“Examining how institutional factors facilitate or inhibit hook-up culture, or nurture alternative sexual cultures, promises to be a rich direction for research. We still know very little about how hook-up culture varies from campus to campus…”

In my research, I attended different campus cultures and their supporting institutional structures, attempting to understand how their differences might affect hooking up. When I did, I found not “a” hookup culture but four different ones.

First, there is a stereotypical hookup culture.

Stereotypical hookup culture is what most students and researchers assume to be the norm on all college campuses. It does exist. There are people who hookup without expectations of anything afterwards, and they do so frequently. The issue is that they are, in fact, a minority of students on a campus. In their “A New Perspective on Hooking Up Among College Students,” Megan Manthos, Jesse Own, and Frank Finchman found that about 30% of students accounted for almost 75% of hookups on campuses. Heldman and Wade estimated that only around 20% of students hooked up ten times or more. In my work, only 23% of students hooked up more than five times in the course of a year, and only 12% hooked up more than 10 times a year. Moreover, this minority of students shared similar traits: white, wealthy, and come from fraternities and sororities at elite schools.

Second, there is a relationship hookup culture.

While hooking up is not supposed to include any subsequent expectations, many people use it as a way into relationships. In “Sexual Hookup Culture”, Justin Garcia and his fellow authors found that not only did most people hope for a relationships—65% of women and 45% of men—many people even talked about it—51% of women and 42% of men. This hope for relationships partially helps to explain that hooking up is rarely anonymous or random.Almost 70% of hookups are between people who know each other, almost 50% of people assume that hooking up happens between people who know each other, and more people hookup with the same person than hookup with a person only once. This culture, which seems to encompass the largest percentage of students, tended to operate on campuses where there was lots of homogeneity in the student body, places like small, regional colleges.

Third, there is an anti-hookup culture.

While it might seem strange to name not hooking up a hookup culture, it is a culture that exists in opposition to the assumed norm of stereotypical hookup culture, a reality seen by the fact that those who don’t hookup are often pushed to the fringes of campus social life. They tend to be racial minorities, those of the lower economic class,members of the LGBTQ community, and those who are highly religiously committed. These are not the majority of students, but they are a substantive minority, large enough to be a factor on most campuses. While the typical campus with an anti-hookup culture is one that emphasizes and promotes its religious identity, places like Harvard University had 24% of students who did not have sex while there, and 21% who never had a relationship.

Finally, there is a coercive hookup culture.

Coercive hookup culture takes stereotypical hookup culture and attempts to legitimize the use of force in sexual activity. This is done in various ways. Some utilize gender stereotypes and cultural norms to legitimize coercion. Others rely on beliefs about masculinity or rape to rationalize their actions. Alcohol can make force seem more acceptable, while pornography can make coercion seem normal. Whether through one of these means or some other, perpetrators’ legitimization of the violence enables the rampant sexual assault on college campuses, a coercive hookup culture. According to the Center for Disease Control, around 20% of dating relationships have non-sexual violence, and 20% of women in college experience completed or attempted rape. 85% percent of these assailants are known, usually boyfriends, ex-boyfriends, or classmates. Even though these sexual assault numbers have been practically unchanged since 2007, only recently have colleges and universities started to wrestle with them, and then only after the Department of Education’s began investigating several institutions of higher education for Title IX violations in early 2014. While there is some evidence that this culture is more pervasive amongst male student athletes, this just adds further supports to the research that this coercive culture exists on most campuses.

Attending to the distinctive aspects of campuses helps researchers to see variations in hookup culture. Colleges differ in size, geographic location, mission, and student demographics, just to name a few factors that inevitably affect students. I examined Catholic campuses, and, even within these institutions, I found variations in their Catholic identity that led to variations in their hookup cultures. Thus, as the topic is studied, researchers should be attentive to the context in order to accurately understand what is occurring.

This diversity of hookup cultures can also be useful for students. Knowledge of different hookup cultures can help to identify coercion and assault by distinguishing it from other types of hooking up and, in doing so, facilitate better means for stopping it. In addition, knowledge that stereotypical hookup culture is just an assumed norm and not a statistical one means that those who want something other than a stereotypical hookup are not alone. In fact, they are probably the majority. As such, they can be more vocal about and comfortable with pursuing alternatives. There need not be a banishment of stereotypical hooking up but rather a greater tolerance for those who want something else.

Featured image credit: Georgetown Jesuit Residence, by Patrickneil. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The four college hookup cultures appeared first on OUPblog.

April 11, 2017

23 treaties of Utrecht that changed European history forever

11 April marks the 304th anniversary of the signing of the Peace of Utrecht by most of the representatives at the congress that convened to negotiate the terms that would end the War of the Spanish Succession. Or perhaps it should be 12 April. A few contemporaries alleged that the documents were backdated so that the ceremony would not fall on 1 April, or Fools’ Day, according to the old calendar. At that time, England and most of Protestant Europe had still not accepted the Gregorian calendar reform of 1582, so countries that followed the old style were, by the eighteenth century, 11 days behind those who had accepted the new style. Purportedly, the representatives of the Netherlands either deliberately signed after midnight or refused to backdate the agreement, thinking 1 April (that is, April Fools’ Day) a fitting date for such a treaty.

The pacification of Utrecht ended more than 13 years of war that had been fought in both the old and new worlds. The War of the Spanish Succession had broken out after the death of Carlos II (dubbed Carlos the Bewitched), who had bequeathed his empire to a Bourbon heir. Fear of French hegemony united the allies: England, the United Provinces, Austria, most of the Holy Roman Empire, many of the Italian princes, Portugal, and Savoy against France, the elector of Bavaria, the archbishop of Cologne, and a few other minor powers. As the struggle continued, the domestic landscape shifted with the Tories ending the Whig domination in Great Britain in 1710 and beginning secret negotiations with France. Those negotiations settled most of the points of contention before the “conferences” at Utrecht convened.

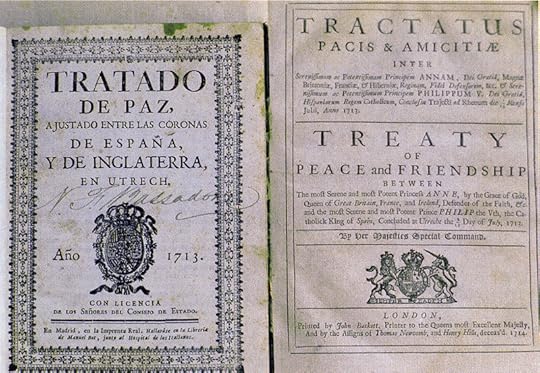

A first edition of the Treaty of Utrecht, 1713, in Spanish (left), and a copy printed in 1714 in Latin and English (right). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

A first edition of the Treaty of Utrecht, 1713, in Spanish (left), and a copy printed in 1714 in Latin and English (right). Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.15 months after the negotiations had begun in the picturesque town of Utrecht, the peace with France was signed by Britain, Savoy, Portugal, and the United Provinces. Between 1713 and 1715, 23 separate treaties and conventions were signed (Spain and Austria did not come to final terms until 1725), and together were referred to as the “Peace of Utrecht.” Missing from the signatories were the representatives of the Holy Roman Empire. Faced with escalating demands from France, the German representatives had balked and withdrawn. For them, the war with France continued until the Treaty of Rastatt settled the conflict between France and the Austrian Emperor in March of 1714, and the treaty of Baden reconciled France and the Holy Roman Empire in September of 1714. Frederick William I signed the treaty as king in Prussia, but fought on as elector of Brandenburg.

As in many treaties, the most powerful players determined the outcome. After the scrabble for territory, the empire of Carlos II was partitioned with Philip V the Bourbon gaining Spain and Spanish America, and with the Habsburgs acquiring the Spanish Netherlands and Italian territories, both bulwarks against French aggression. The Dutch and the Savoyards were given lands that served as barriers against the French. The Dutch received a barrier of fortresses in the Southern Netherlands that proved ineffective; Savoy received the island of Sicily with its royal title, some Milanese territory, and a defensible Alpine border against France. Brandenburg-Prussia gained some minor territories and the acknowledgment of the elector’s kingship in Prussia, a recognition of that state’s growing power. Despite significant losses, France kept the boundaries of 1697 as did the Holy Roman Empire with the exception of Landau. Portugal’s alliance with Britain ultimately won the country concessions in the new world. The major role of the British was recognized when the nation brokered the peace and gained the “asiento”: the right to send an annual ship to Spanish America and territories in the new world. The cession of Gibraltar and Minorca ensured British naval supremacy in the western Mediterranean.

After the “Peace of Utrecht,” the international order was dominated by five great powers: France, Britain, Spain, the Habsburg Empire, and Russia. Some of the issues purportedly settled with the treaty continued to haunt Europe, such as the port of Dunkirk, a haven for pirates and privateers that plagued British trade; the problem of Acadia, which became the tragedy of Acadia in the eighteenth century; the “French shore,” the right to use the Newfoundland shore to dry fish, which lasted until 1972, and Gibraltar, which the Spanish still claim today. A Bourbon reigns today in Spain, but Catalonia, which fought on the losing side, continues to claim its rights.

Featured image credit: “Allegory of the Peace of Utrecht (1713)” by Antoine Rivalz. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post 23 treaties of Utrecht that changed European history forever appeared first on OUPblog.

APA Pacific 2017: a conference guide

The Oxford Philosophy team is excited to see you in Seattle for the upcoming 2017 American Philosophical Association Pacific Division Meeting! We have some suggestions on sights to see during your time in Washington, as well as our favorite sessions to attend at the conference.

No matter what you’re interested in, Seattle is full of exciting things to do. Get lost in the Washington Park Arboretum on the shore of Lake Washington, or take a stroll around Pioneer Square. If views of the skyline are what you’re after, take them in via water taxi or from atop the famous Space Needle. Runners and walkers alike will enjoy the beaches and 3.2 miles of trails through Golden Gardens Park, and art lovers can spend hours in the Seattle Art Museum. And what trip to Seattle would be complete without a visit to Pike Place Market?

Pike Place Market Entrance. Photo by Mtaylor444. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Pike Place Market Entrance. Photo by Mtaylor444. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.While at the conference, be sure to keep an eye out for these sessions that we’re excited about:

Wednesday, April 12th 9:00 a.m.–Noon.

Book Symposium: Mark Siderits, Studies in Buddhist Philosophy.

Wednesday, April 12th 1:00–4:00 P.M.

Book Symposium: Gila Sher, Epistemic Friction: An Essay on Knowledge, Truth, and Logic.

Wednesday, April 12th 4:00–6:00 P.M.

APA Committee Session: Creolizing Hegel.

Arranged by the APA Committee on the Status of Black Philosophers and the APA Committee on Hispanics. Featuring speakers Carlos Alberto Sánchez, Shannon Mussett, and Michael J. Monahan.

Thursday, April 13th 9:00 A.M.–Noon.

Invited Symposium: Race.

Chaired by Cynthia Stark and featuring speakers Quayshawn Spencer, Ron Mallon, and Jeanine Schroer.

Thursday, April 13th 1:00–4:00 P.M.

Book Symposium: Diana Tietjens Meyers, Victims Stories and the Advancement of Human Rights.

Thursday, April 13th 4:00–6:00 P.M.

Invited Symposium: Sensory Transformation and Disability.

Chaired by Noel Martin and featuring speakers Marina Bedny, Casey O’Callaghan, L. A. Paul, and commentator Eric Brown.

Thursday, April 13th 6:00–9:00 P.M.

Society for Women in Philosophy Informal mini-conference on issues of inclusion and diversity in philosophy. Arranged by the APA Committee on Inclusiveness and the University of Washington Department of Philosophy Climate Committee, co-sponsored by the APA Committees on the Status of Black Philosophers, Hispanics, the Status of Women in Philosophy, Teaching Philosophy, and Pre-college Instruction in Philosophy, and the Pacific Division of the Society for Women in Philosophy. Topic: Issues of Inclusion and Diversity in Hiring Practices featuring speakers Linda Martín Alcoff, Naomi Zack, and Carolyn Dicey Jennings.

Friday, April 14th 9:00 A.M.–Noon.

Book Symposium: Rivka Weinberg, The Risk of a Lifetime: How, When, and Why Procreation May Be Permissible.

Friday, April 14th 1:00–4:00 P.M.

Book Symposium: Brian Epstein, The Ant Trap: Rebuilding the Foundations of the Social Sciences.

Friday, April 14th 4:00–6:00 P.M.

Invited Symposium: Faith, Belief, and Evidence.

Chaired by Daniel Howard-Snyder and featuring speakers Robert Audi, Brian Ballard, Beth Rath, George Tsai, and Frances Howard-Snyder.

Saturday, April 15th 9:00 A.M.–Noon.

Book Symposium: Jenann Ismael, How Physics Makes Us Free.

Saturday, April 15th 1:00–4:00 P.M.

Invited Symposium: Videogame Aesthetics.

Chaired by Dominic McIver Lopes and featuring speakers Gwen Bradford, Christopher Thi Nguyen, Stephanie Patridge, and commentator: Mark Silcox.

Don’t forget to visit the Oxford University Press Booth! Take advantage of an exclusive conference discount on new and featured books, including daily flash sales at 2 P.M. Pick up complimentary copies of our philosophy journals which include Mind, Monist, Philosophical Quarterly, Analysis, and more. Receive free access to our online resources including Oxford Handbooks Online, Very Short Introductions, Oxford Reference, and more. And, of course, stop by to say hi!

Featured image: Seattle from Kerry Park. Photo by X-Weinzar. CC-BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post APA Pacific 2017: a conference guide appeared first on OUPblog.

Could your glasses pay for themselves?

Could your glasses pay for themselves? In a manner of speaking, the World Surf League (WSL) and Visa would say yes. As part of the credit card company’s new official partnership with WSL’s Quiksilver and Roxy Pro Gold Coast (the first stop on the WSL Championship Tour), Visa is piloting payment-enabled sun glasses that “feature contactless payment capability and (eliminate) the need to carry cash or cards on the beach.”

This partnership is beneficial to both the WSL and Visa in several ways. First, it does potentially solve a problem that any beach goer (this author included) has faced when going to the beach. It can be difficult to carry around a wallet in a bathing suit without worrying about it getting it wet and/or possibly damaging one’s credit card(s). Eliminating much of the need for a wallet with something most people need on the beach anyway (sunglasses) elegantly solves this problem.

Second, this partnership does generate positive brand awareness and brand perception for both WSL and Visa. For the WSL, increasing brand awareness in an incredibly crowded sports marketplace is critical. This differentiated partnership demonstrates to companies and fans the unique ways the WSL activates its corporate partnerships. As an increasing number of younger consumers test out novel payment methods (think Venmo or Bitcoin), the use of more traditional credit cards could decline in the future. Visa partnering with the WSL and using novel technology should attract significant interest from the sport’s core demographic to the company.

What is arguably the most interesting part about this partnership, however, is how it effectively leverages new technology to drive new revenue for a corporate partner. It is clear that the growth of sports technology has been massive, particularly over the last five years. What is less clear is how to monetize technology, particularly when it comes to wearables. Technology-enabled glasses have been a focus for companies both inside and outside of the sports industry. Google Glass became an infamous flop for the search engine giant while Snap Inc. has made a bet that its potential new glasses will entice advertisers using its unique filters.

The WSL and Visa, however, have a sure thing when it comes to their glasses partnership and revenue generation. The WSL has provided a way for Visa to either attract new, younger customers or retain customers it already has. Visa makes money by charging a processing payment fee to merchants every time someone uses its products. Glasses make it as easy as possible for someone, particularly younger demographics, to make a payment. A customer just needs to have his/her glasses on when purchasing products. This also creates a switching cost for customers to move to a new payment provider. Why switch to a MasterCard, Venmo, Paypal, or Bitcoin if Visa makes my life easier, particularly when I am at the beach and/or on vacation?

A version of this post originally appeared on Block Six Analytics.

Featured image credit: beach sand sunglasses red by Alexandra_Koch. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Could your glasses pay for themselves? appeared first on OUPblog.

The end of scholarship?

What exactly is ‘scholarship’? According to a widely-used definition attributed to the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), research is ‘creative work undertaken on a systematic basis in order to increase the stock of knowledge’. But there seems to be no OECD definition of ‘scholarship’. Wikipedia’s article under that heading is about scholarship(s) as ‘a form of financial aid’, with cross references to ‘The Scholar Ship’ (an early 21st-century international education programme conducted on a passenger liner), and a warning against potential confusion with either ‘Scholarism’ or ‘Scholasticism’.

In Australian and perhaps other academic parlance, ‘scholarship’ sometimes means intellectual work in the humanities and social sciences, as distinct from the natural sciences, pure and applied; this presumably reflects the OED’s definition of ‘scholar’ as ‘a learned person, esp. in language, literature, etc’. At my own university ‘research and scholarship’ was once a standard formula encompassing what all academics were supposed to do when neither teaching nor engaged in administration. In recent years, however, this use of the term ‘scholarship’ has ceased. We are all now ‘researchers’, even those who don’t frequent laboratories clad in white coats.

We are all now ‘researchers’, even those who don’t frequent laboratories clad in white coats.

This semantic shift might scarcely matter, if the OECD definition of research were more inclusive. But some additions to the existing body of knowledge are easier to demonstrate than others, especially those related to the natural world with which scientists deal, as distinct from the individual and social worlds of human beings studied by humanists and social sciences. Discovering a hitherto unknown organism or property of some compound fits the OECD bill much more readily than reinterpreting a work of art or literature or the causes of World War I.

That difference is reflected in bureaucratic conventions applied to the assessment of academic performance. Thus every named author of a multi-author paper published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal can expect some institutional recognition, usually in the form of brownie points counting towards tenure, promotion or eligibility for sabbatical leave — whatever the length of the paper or number of individuals contributing to its publication. No such credit is available for book reviews commissioned by the editors of scholarly journals in the humanities and social sciences.

The assumption may be that such reviews merely express a subjective opinion about the merits of the work reviewed, hence cannot constitute research, because not augmenting the sum of knowledge (regarded as comprising objective ‘facts’). This would ignore the likelihood of a reviewer’s critique revealing aspects of a monograph, or its subject area, not otherwise apparent to the book’s readers, or even its author. But then book reviewing is an uncommon activity for STEM-discipline practitioners, where the paper, not the monograph, is king, although it has long been a vital element of intellectual exchange across most of the humanities and social sciences.

Similar reluctance applies to scholarly contributions to works of reference. Yet while many encyclopaedic reference works, especially in the STEM subjects, purport to be no more than compilations of established knowledge, others—like the ODNB or Australian Dictionary of Biography—represent the fruits of original scholarship (or research, if you prefer). By the same token, editing either a text, or a published volume of essays, is an increasingly ‘pointless’ activity. Yet in the latter case recognizing an intellectual gap best filled by group effort, identifying and commissioning contributors and peer-reviewers, working with authors to ensure their pieces reach a minimum quality threshold and fit together in coherent fashion, so the eventual whole is greater than the sum of its parts—these are hardly mere mechanical processes, distinct from the knowledge-augmenting creativity of the genuine researcher.

Not necessarily imposed on the humanities and social sciences by a philistine managerial-scientist alliance, such discrimination may also be self-inflicted by rule-makers who find it politic to go with whatever they regard as the prevailing tide. But perhaps none of this matters very much in the greater scheme of things. Portents of the impending demise of scholarship—if that is what they are—might even be cheered in some quarters, as the triumph of useful innovation over irrelevant, self-indulgent antiquarianism. In any event, much scholarly activity is already supported by institutions and patrons other than universities, and universities are not all of a piece.

Yet in increasingly complex and uncertain times, the benefits of old knowledge, its preservation and re-assessment, should not be undervalued by default. Even the proto-modernist Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) admitted the possibility that some acquaintance with past errors might help avoid their repetition in the future he and his followers sought to construct according to utilitarian principles. The tensions between Bentham’s single-minded philosophical radicalism and the gradualist, pragmatic, liberal-conservative William Blackstone (1723-1780), his Oxford lecturer and life-long bête noire, still resonate; their differences over history, law, politics, religion, and society continue to intrigue modern readers. The texts being edited by the Bentham project at University College London, and the new Oxford edition of Blackstone’s Commentaries, now provide unprecedented opportunities to explore these two seminally divergent ways of knowing and understanding their world, and our own.

Featured image credit: “Scholarly Discovery” courtesy of Marie Larsen, Barr Smith Library, The University of Adelaide. Used with permission.

The post The end of scholarship? appeared first on OUPblog.

April 10, 2017

How simple, rural products changed Argentina’s history

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, global trade forged new economic alliances and contributed to the emergence of modern ways of life. Emerging from the backwater as one of the world’s major agricultural producers, Argentina’s export-oriented agricultural sector, producing simple products like beef, wool, soybeans, and wheat, propelled its economy and established the nation as the third largest economy in Latin America.

With globalization and industrialization came both freedom and dependency, as Argentina shed the persistent stereotype that the country was simply a collection of farms and ranches. The “Golden Age” ushered in a surge of immigration from southern Europe and elsewhere between 1875 and 1913, while at the same time, the average real per capita incomes grew by 40% and consumption within the nation is estimated to have increased as high as 900%. Rural and urban life blurred into a hybrid culture that thrived on export commodities and domestic consumption.

To further illustrate how the urbanization of simple rural products shaped the culture and history of Argentina, we compiled facts from Eduardo Elena’s article “” that help demonstrate how globalization had such an impact on Argentina from the end of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th.

1. While Argentina’s relatively simple raw products, such as cattle hides, grease and tallow, salted meats, and sheep’s wool may seem crude, these materials were coveted by the most advanced manufacturing sectors of England, northern Europe, and the United States. Greater mechanization and mass production there created demand for imports such as animal skins, which could now be transformed on an unimagined scale into goods like leather shoes.

2. Globalization and industrialization led to selective husbandry of specific species of animals. Nature was transformed to keep up with changes in foreign demand: sheep breeds valued primarily for their wool gave way to stock more suited for their meat; “rangy” criollo cattle were replaced by “improved” pedigree breeds to supply the types of beef coveted by European consumers; and even the grasses of the plains were made over, either into fields of alfalfa for more refined animals or into massive grain farms.

3. Despite their seeming invisibility to most consumers (especially those located abroad), temperate staples became referents in political disputes over consumption and related aspects of economic distribution, social inequality, and national development. The fact that a given ton of wool or wheat came from Argentina may have mattered a great deal to importers and factory owners, who were attuned to differences in quality and price. But customers who purchased finished goods were typically unaware of the origins of the fibers in their clothes or the wheat in the bread purchased at the corner bakery. Moreover, in the European markets where demand was greatest for Argentine commodities, temperate staples were considered so familiar that they were hardly noticed. Imported animals and plants were considered widely “European”—not “Argentine” (or “Canadian” or “Australian,” for that matter).

4. While having a strong reputation as a producer of rural commodities in the twentieth century, Argentina was one of the most urbanized societies in the world at the time. The explanations behind this seeming contradiction lie partly in the characteristics of modern commodity production. The sheer scale of ranching and farming, coupled with greater uses of mechanization and steam-age transportation, ensured that fewer and fewer people were required to generate an enormous surplus of tradable goods.

[image error]“Sembrado de soja en Argentina” by Alfonso. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

5. Efforts to define a shared national identity through food were one way Argentinians addressed the culture tension between the rural and urban in exporting commodities and consuming products domestically. Cultural efforts to mediate these changes were exemplified by the “asado” (a feast of grilled meats, especially beef, similar to a barbeque). Although this custom has centuries-old roots in the region, the asado became reworked during the first half of the 20th century in keeping with new ideas of national identity, or “argentinidad”. The act of grilling meat took on as the masculine figure of the mythic gaucho was reborn in his white male descendant, the “asador”.

A closer look, however, reveals that the “asado,” as practiced by an increasing majority of Argentinians, was more a reflection of an urban, industrializing society than timeless rural customs. The updated version depended on a distinctly modern-day separation between work and leisure and related habits of sociability. The cut of meat that became the centerpiece of the ritual—the “asado de tira” (short rib)—was itself an artifact of the industrial age: only electrical saws adopted in the 1900s could easily cut meat in this fashion, and the meat came from more tender “improved” breeds of cattle. Nevertheless, these realities were disregarded: instead, the “asado” became a way that residents of the modern city and countryside could celebrate their shared ties to a distant, romanticized rural past, one that now defined what it meant to be authentically Argentinian.

6. With global trade, country names became consumer brands. Members of landowner organizations such as the Sociedad Rural Argentina nervously strategized about how to beat competitors, who began using marketing slogans like “New Zealand Lamb, Best in the World.”

7. While industrialization has greatly contributed to wealth in Argentina, the process of deindustrialization that started during the 1970s has also contributed substantially to the nation’s economy. Deindustrialization made commodity exports more valuable as a source of foreign exchange and taxable state revenue.

New export goods such as Malbec wine and apples destined for markets in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere have created additional riches from the 1990s onward.

Featured image credit: “Countryside of Argentina” by Douglas Scortegagna. CC BY-SA 2.0 via Flickr.

The post How simple, rural products changed Argentina’s history appeared first on OUPblog.

Remains of ancient “mini planets” in Mars’s orbit

The planet Mars shares its orbit with a few small asteroids called “Trojans”. Recently, an international team of astronomers have found that most of these objects share a common composition and are likely the remains of a mini-planet that was destroyed by a collision long ago.

Trojan asteroids move in orbits with the same average distance from the Sun as a planet, trapped within gravitational “safe havens” 60 degrees in front of and behind the planet. The significance of these locations was worked out by 18th-century French mathematician Joseph-Louis Lagrange. In his honour, these locations are now known as “Lagrange points”. The point leading the planet is L4; that trailing the planet is L5.

About 6000 such Trojans have been found at the orbit of Jupiter and about ten have been found at Neptune’s. They are believed to date from the solar system’s earliest times when the distribution of planets, asteroids, and comets was very different than the one we observe today.

Although many Trojans are known to exist, Mars is currently the only terrestrial planet known to have Trojan asteroids in stable orbits. The first Mars Trojan was discovered over 25 years ago and named “Eureka” in reference to Archimedes’ famous exclamation. So far, the number of known Trojans in Mars’s orbit is nine, a factor of 600 fewer than Jupiter Trojans; however, this relatively small sample reveals an interesting structure not seen elsewhere in the solar system.

All the Trojans, save one, are trailing Mars at its L5 Lagrange point. What’s more, the orbits of all but one of the eight L5 Trojans group up around Eureka itself. The reason for the uneven distribution of these objects is unclear, though there are a couple of possibilities. In one scenario, a collision broke up a precursor asteroid at the L5 point, the fragments making up the group we observe today. Another possibility is that a process called “rotational fission” caused Eureka to spin up, eventually spawning off small pieces of itself in heliocentric orbit. Whatever the cause, the grouping strongly suggests that the asteroids in this “Eureka family” were once part of a single object or a progenitor body, and circumstantial evidence for this hypothesis is strong. By obtaining the colour spectrum of sunlight reflected off the asteroid’s surface, this hypothesis can be tested.

Mineral Olivino by Luis Miguel Bugallo Sánchez. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Mineral Olivino by Luis Miguel Bugallo Sánchez. CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.For this purpose, an international team of astronomers, led by Apostolos Christou and Galin Borisov, recorded the spectra of two asteroids that belong to the Eureka family using the X-SHOOTER spectrograph mounted on the Unit 2 telescope of the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope facility in Chile. Analysing the spectra, they found that both objects had very similar compositions to that of Eureka, thus confirming the genetic relationship between family asteroids. The finding also marks a significant “first” for asteroid studies; the spectra show that these asteroids are predominantly composed of olivine, a mineral that typically forms within much larger objects under conditions of high pressure and temperature. The implication is that these asteroids are likely relict mantle material from within mini-planets or “planetesimals” which, like the Earth, developed a crust, mantle, and core through the process of differentiation but have long since been destroyed by collisions.

Many other families exist in the Asteroid Belt between Mars and Jupiter, but such olivine-dominated asteroids are unique. This is related to the so-called missing-mantle problem: if one adds up the mass of different minerals in the asteroid belt and particularly those thought to be pieces of broken up, differentiated asteroids, there is a deficit of mantle material compared to rocky crust and metallic core material.

Although the discovery of this olivine-dominated family does not provide a final solution to the missing mantle problem, it does show that mantle material was present near Mars early in the solar system’s history. This suggests that such material has participated in the formation of Mars and perhaps its planetary neighbour, our own Earth.

Featured image credit: ‘mars-land-planet-cosmos-stars’ by Aynur_zakirov. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Remains of ancient “mini planets” in Mars’s orbit appeared first on OUPblog.

H. G. Wells and science

The Island of Doctor Moreau is unquestionably a shocking novel. It is also a serious, and highly knowledgeable, philosophical engagement with Wells’ times–with their climate of scientific openness and advancement, but also their anxieties about the ethical nature of scientific discoveries, and their implications for religion. Listen to Professor Darryl Jones, editor of the Oxford World’s Classics edition of The Island of Doctor Moreau, discuss H. G. Wells’ connections to science and the themes of scientific ethics and conflict in his great scientific romance.

Featured image credit: Featured image credit: “Surgery, Medical Science, The Surgeon’s Knife…” by Prylarer. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post H. G. Wells and science appeared first on OUPblog.

The face of today’s elder caregiver

Elder care requires an intergenerational partnership. The duty to care for an aging parent is often grounded in an understanding of reciprocity; the parental hands that once held ours during childhood now require our supportive presence in old age or during an illness.

How does this caregiving expectation of reciprocity apply to the approximately 76 million Baby Boomers in the United States whose aging will dominate the next few decades? The Baby Boomers’ high rates of divorce, remarriage, single parenthood, decreased birthrate, and their geographic mobility signal profound changes in the traditional elder care script. More than 40% of adults in America include a step-relative in their family. Many Baby Boomers now count grown stepchildren as a part of their families that they did not care for, let alone know, during the stepchildren’s childhood. Elder care can no longer be based on a presumption of generational reciprocity. And yet, family caregiving, in contrast to paid professional care, remains the backbone of our society’s approach to caring for its aging elders, especially those with chronic or terminal illness.

To learn more about the experiences of today’s caregivers, we interviewed respondents aged 28 to 49 years old who had played an integral role in caring for their now deceased parent or stepparent. Our sample reflected current Baby Boomer family demographics: one-third of the parents were still married to their first spouse at the time of their death, one-third were single parents (many as a result of divorce), and one-third had separated from their first spouse or partner and remarried since having kids.

Kendra, one of our respondents, is one face of the new normal in family elder care. She was the primary caregiver for her ex-stepfather in his final months. Throughout her life, Kendra has known several stepfathers, but she recalled that she and Jimmy just clicked. They stayed in touch even after he and her mother divorced. They both enjoyed working outside and fixing up the house together. When she was in between jobs, he helped support her financially and connected her to his professional network.

Kendra prided herself on her reliability and loyalty. As her ex-stepfather faced decisions about downsizing and moving to an assisted living center, she helped fix up his house to ready it for sale. She explained that she “was the one who showed up when called.” Her presence created some conflict with her three stepsisters, especially when they decided not to come to the assisted living center the night Jimmy died.

Kendra is one example of today’s family caregiver, and our interviews with other family caregivers, especially in blended families, showed us that resilient family systems tend to share these attributes in relationship to the caregiving and loss experience:

The parental hands that once held ours during childhood now require our supportive presence in old age or during an illness.

Understandable. The grown child understood the implicit and explicit rules and expectations of his or her family system. If the parent became incapacitated or died the interviewee understood the values and wishes of the parent figures.

Manageable. The grown child felt a sense of control within the caregiving, medical decision-making, and funeral planning process. The grown child was able to contribute money, time, effort, or emotional support during the experience.

Meaningful. The grown child felt that providing care was worthwhile. They incorporated the experience of support and loss into their sense of self and their family story.

An expectation of ongoing relationship. The family members, narrowly or broadly defined, remain in contact a year after the death.

Almost half of those interviewed could be considered to have all four elements. More than half of those with all four elements of resiliency came from married parent families because a life-long history of shared norms contributed to the ease of making the care experience understandable, manageable, and meaningful–and a surviving parent who served as the symbol of those norms helped in managing the loss of the other parent. For single parent and remarried parent-led families with all four elements, several factors helped compensate if there was a low level of shared norms:

close geographical proximity to the parents, with many grown children living with the parent during the care window;

a high level of family norm coherence such as a history of family rituals: celebrating holidays or significant family events together, including special foods, preparation routines, anticipated and expected traditions, and family identity defining memories shared by all members;

the ability of the grown child to contribute to the care of the ill parent through money, action, or presence;

a history of financial and emotional support between the grown child and parents/stepparents;

shared religious beliefs and practices; and

in remarried families, the ability of the grown child to empathize with the parent’s spouse or significant other and see the surviving stepparent through the eyes of the parent and value that stepparent as a human being.

Kendra brought to the interview a stuffed bear the hospice volunteers had made for her from Jimmy’s shirts. With tears in her eyes she confessed, “I considered him my dad.” She tried to stay connected to her stepsisters in the year since his death, but her attempts were largely one-sided. Hence, she grieved both him and them. As Kendra’s story shows, although caregiving continues, changing family structures change the caregiving–and caring–experience.

Featured image credit: The Beauty of Old Age by Vinoth Chandar. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

The post The face of today’s elder caregiver appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers