Oxford University Press's Blog, page 382

April 7, 2017

A choice of St. John Passions

This is the time of year at which you are most likely to hear J. S. Bach’s St. John Passion, which tends to be performed in accordance with the Christian liturgical calendar even when it is programmed in a secular concert. If you do, you probably expect that the work will be recognizable and even predictable in its makeup, and consistent from presentation to presentation–that’s what makes it a “piece,” after all. But the passion is not so stable.

I don’t mean in the size and composition of vocal and instrumental forces, for which there are now several choices ranging from Bach’s own very small ensembles to large-scale modern renditions with chorus, soloists, and orchestra. Rather, performances can differ from one another in the words and notes that are sung and played–in the movements that make up the work. This is because the St. John Passion comes down to us in several versions. Their existence points both to features of eighteenth-century music making and to choices that we face today.

Bach composed the St. John Passion for Good Friday 1724, during his first Lent and Easter in Leipzig. He and an anonymous librettist created a work that presents John’s gospel narrative of the crucifixion, along with poetic commentary in the form of hymn stanzas and newly-written poetry set as instrumentally-accompanied recitatives and arias (including opening and near-closing poetic arias for chorus).

Bach was responsible for putting on a passion performance each year, alternating between the St. Thomas and St. Nicholas churches. Their congregations were distinct, but Bach nonetheless evidently felt obligated not to repeat a passion setting from year to year. But he did not compose a new setting in 1725, nor did he turn to the music of another composer, as he sometimes did. Instead he revised his St. John Passion, replacing several movements and adding one.

He substituted a new piece for the original opening chorus “Herr, unser Herrscher,” a setting of a poetic text based on Psalm 8. In its place he put a new setting of the first stanza of the hymn “O Mensch, bewein dein Sünde gross” (a piece he later used to conclude the first half of the St. Matthew Passion in its revised form). At the end, instead of the concluding chorale stanza “Ach Herr, lass dein lieb Engelein” he specified a setting of the German Agnus Dei, the movement “Christe, du Lamm Gottes” recycled from one of the cantatas he had performed at his Leipzig audition. In place of the aria “Ach, mein Sinn,” just after Peter’s denial of Jesus, he supplied a replacement, “Zerschmettert mich, ihr Felsen und ihr Hügel.” Just before that episode he added a new aria, “Himmel reisse, Welt erbebe,” creating a new moment of reflection and commentary. Instead of the accompanied recitative and aria “Betrachte, meine Seel” and “Erwäge, wie sein blutgefärbter Rücken” came a new aria, “Ach windet euch nicht so, geplagte Seelen.”

We know all this from the miraculous survival of the original performing parts–the very pieces of paper from which Bach’s musicians sang and played. They take some serious sorting out, but to the extent that we can establish the state of the parts in a given year, we can know which movements were performed.

Bach most likely made these changes to create, in some sense, a new passion setting. That might be difficult to understand because most of the words and music remained the same, including almost all the gospel narrative, which might seem to us to represent the most important element of the work. But the narration of the passion story according to one of the gospels was a fixture of the Good Friday observance; what changed from year to year–and what gave a musical passion setting its identity–were the commentary movements. So Bach’s revisions, substituting opening and closing movements and replacing or adding arias, arguably made the 1725 St. John Passion a new work.

It’s a work with a different theological perspective of the passion story. The first version, in the language of its commentary movements, emphasizes the question of Jesus’s identity and his paradoxical glorification through the abasement of the crucifixion. Most of the 1725 movements focus on a view of humankind as sinful; this is reflected, for example, in the new opening chorale (“O humankind, consider your great sins”) and closing movement (“Christ, lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world . . .”). The new arias are mostly on this theme as well.

So we have two versions of the St. John Passion, from 1724 and 1725. That is not the end of the story, though, because we have evidence of yet another version Bach performed in the early 1730s. In that performance he restored most of the original movements and removed the 1725 substitutes. He did add one new aria and an instrumental sinfonia, but those two movements are now lost because in 1749, possibly the last year he directed a passion performance, Bach revised the work once again, mostly restoring the 1724 sequence of movements, though with some revised poetic texts. In doing so he set aside the pages that contained the new aria and sinfonia from the 1730s, and they have not survived.

We thus appear to have four versions of the St. John Passion, where a “version” is defined as the form in which Bach presented the work. Two (1725 and 1749) survive almost intact; there are gaps in the others, particularly the one from the 1730s.

But there is another complication. In the late 1730s, Bach began a neat copy of the work made from his presumably messy composing score of 1724, but didn’t finish. After about 10 numbers he abandoned the project; we know neither why he started nor why he stopped. Some 10 years later an assistant completed the copy, presumably working from the same composing score. (The result is the only original score that survives.) The copyist faithfully reproduced what was in his model, but in his portion Bach was not content to leave his music alone. making numerous revisions to vocal and instrumental lines.

Is this a version? Certainly it’s not a complete one, because Bach did not get past the first 10 movements. The question is even knottier because even this partial revision doesn’t fit our definition of a “version”–a form of the piece heard in performance. That is because the revised readings never found their way into Bach’s performing material; recall that we have the original parts, including from 1749, and they reflect the same music that had been heard in Leipzig since 1724, give or take a few other minor changes. So the status of the partial score “version” might well be different.

It used to be that performances of the St. John Passion typically did not pay much attention to this history. What has tended to be heard is a version published in 1973 in the complete edition of Bach’s music. That edition is a pastiche, using the revised score for the first 10 numbers, but presenting the rest of the piece in the version from the 1749 parts–minus the textual changes made in that year. There were some good reasons to present the work this way, but you can see that it does not represent any of the versions heard under Bach.

Things have changed, to a degree: Performances, recordings and musical editions today often specify what version of the piece they are presenting. Those from 1725 and 1749 can be performed intact; there are gaps in the 1724 and 1730s versions–which is one reason the modern pastiche is still heard so often.

We thus have a choice of four or five St. John Passions, and this richness is a reminder that this was practical working repertory for Bach–a tool for fulfilling the musical obligations of his job. That meant revising and adapting his compositions as needed. We probably need to free ourselves from the idea that there is one abstract, ideal St. John Passion, recognizing instead that it represents a family of versions, not a fixed text.

Which one will you choose?

Featured image: Pages from the original “Soprano concert[ante]” part for Bach’s St. John Passion BWV 245 showing revisions connected with various versions of the work. Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin/Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Musikabteilung mit Mendelssohn-Archiv, Mus. ms. autogr. Bach St 111. CC by 4.0 via Bach Digital.

The post A choice of St. John Passions appeared first on OUPblog.

How has Mexico influenced the United States economically?

While the current US administration is re-examining the North American Free Trade Agreement and finding issues with the trade deficit, it is worth considering the impact of trade between the United States and Mexico and examining the history between these two neighboring nations.

In the following excerpt from the forthcoming 2nd edition of Mexico: What Everyone Needs to Know, Roderic Ai Camp explores how Mexico has contributed to the US economy in recent years. The crucial role Mexico has played in the US economy is carefully analyzed, focusing not only on the country as a whole, but the impact Mexican trade has had on individual states.

Mexico has played a significant role in the rapid expansion of US exports in the 1990s and 2000s. Mexico has alternated between being the second and third most important trade partner of the United States in the past decade. In 2014, the United States exported a total of $240 billion worth of goods to Mexico, the most important of these products coming from the computers and electronics, transportation, petroleum, and machinery sectors. Canada purchased $312 billion of our exports in 2014. China purchased only $124 billion of US exports. Exports to Mexico accounted for approximately 1,344,000 jobs in the United States in 2014.

California alone, boasting the eighth-largest economy in the world, exported more than 15% of its products to Mexico in 2014, exceeding what it trades with Canada, Japan, or China. As of 2014, Mexico’s purchases of California exports supported nearly 200,000 jobs in the state.

In fact, 17% of all export-supported jobs in California, which account for a fifth of all individuals employed in the state, are linked to the state’s economic relationship with Mexico. More than half of those export-related positions can be traced to the North American Free Trade Agreement.

“As of 2014, Mexico’s purchases of California exports supported nearly 200,000 jobs in the state.”

California and Texas, the two largest economies in the United States, which are two of the three largest state/provincial economies in the world, are significantly influenced economically by Mexico. Six states, in 2014, Arizona (41%), New Mexico (41%), Texas (36%), New Hampshire (25%), South Dakota (23%), and Nebraska (23%), depended heavily on Mexico to purchase their exports. The GDP of the United States and Mexican border states accounts for a fourth of the national economy of both countries combined, exceeding the GDP of all the countries in the world except for the United States, Japan, China, and Germany.

The United States provides the largest amount of direct foreign investment in Mexico, but Mexican entrepreneurs and venture capitalists invest in the United Sates. By 2013, Mexico had invested $33 billion, the only emerging economy among the top 15 countries with direct foreign investments in the United States. In 2015, Pemex, the government oil company, opened the first retail gasoline station in the United States, in Houston, and plans on opening four more in that city.

This is a pilot project to test the American market nationally. OXXO, another Mexican firm, has opened two convenience stores in Texas, and plans on investing $850 million to open 900 stores in the United States. Finally, Mexico also influences the US economy through tourism in the same way that US tourists play a central role in Mexico’s economy. In 2014, fully 75 million foreigners visited the United States, generating $221 billion. Canada accounts for the largest number of visitors each year, followed by Mexico, whose 17 million tourists in 2014 spent $19 billion. Along the border, at the end of the decade, Mexican visitors generated some $8 billion to $9 billion in sales and supported approximately 150,000 jobs.

Featured image credit: “Ciudad Mexico City” by Alejandro Islas. CC BY 2.0 via Flickr.

The post How has Mexico influenced the United States economically? appeared first on OUPblog.

Preventing misdiagnosis of intracranial pressure disorders on diagnostic imaging

The bony cranium defines the intracranial space and contains three major components: the brain, vasculature, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The relative amounts of these three components must be in equilibrium; otherwise, the pressure inside the head (intracranial pressure, ICP) will become excessively high or low and result in undesirable clinical manifestations. A variety of important disease processes can abnormally increase ICP including space-occupying masses, venous sinus thrombosis, and hydrocephalus. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH, previously known as “pseudotumor cerebri”) is an additional condition that results in abnormal elevated ICP without any such identifiable cause. Conditions that cause abnormally decreased ICP typically result from leakage of CSF through defects in the skull base or the contiguous spinal canal, termed “spontaneous intracranial hypotension” (SIH) when there is no known inciting cause.

Symptoms such as headache that are commonly seen in the setting of ICP disorders are frequently nonspecific, extremely common in the general population, and most often unrelated to underlying structural intracranial pathologies. The initial step in a diagnostic workup is eliciting symptoms and evaluating clinical signs of abnormally increased or decreased ICP. Imaging with computed tomography (CT), or more commonly magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is frequently performed as part of this diagnostic workup. While imaging was traditionally obtained to exclude key important diagnoses (such as brain tumor and hydrocephalus), numerous recent studies have shown that there are a variety of imaging findings that have high associations with chronically elevated or decreased ICP.

Imaging findings in the orbits, skull base, dural venous sinuses, posterior fossa, and spine are commonly seen in association with abnormal ICP. Increased familiarity with these imaging findings by radiologists and clinical specialists results in the potential for improved diagnosis, but also the potential for misdiagnosis and over-diagnosis. While some patients with primary headache disorders may have undiagnosed ICP disorders with findings visible on MRI, there is also high potential for isolated imaging findings, particularly when taken out of appropriate clinical context, to result in subsequent over-testing and over-diagnosis. Two imaging findings that can be seen in the setting of high ICP are a CSF-filled “empty” sella and cerebellar tonsillar ectopia.

“Imaging findings in the orbits, skull base, dural venous sinuses, posterior fossa, and spine are commonly seen in association with abnormal ICP.”

The finding of an expanded, CSF-filled “empty” sella is generally abnormal in younger patients but becomes much less useful as patients enter their 40s and 50s, and transmission of normal ICP over time through innate weaknesses in the diaphragm sella expand the sella turcica. The presence of additional imaging findings in the orbit, skull base, and venous sinuses can provide credence to the suspicion of elevated ICP in the setting of an “empty” sella but an isolated finding has far less significance.

A second problematic imaging finding is that of cerebellar tonsillar ectopia. This appearance of the cerebellar tonsils extending further below the foramen magnum than expected may be due to a variety of innate, congenitally abnormal, or ICP-related conditions. It is important to keep in mind that there is variability in the appearance of nearly all anatomic structures, and that in some people the cerebellar tonsils may have simply developed lower than usual, if they maintain a normal rounded morphology. This is to be distinguished from a Chiari 1 malformation where the tonsils are low-lying and “peg-like” in morphology and may be associated with other findings such as a spinal cord syrinx. IIH can also result in cerebellar tonsillar ectopia presumably due to the increased ICP pushing brain structures downward, as can SIH due to loss of the buoyancy from CSF causing a “sagging” appearance of the brain. It is critically important to differentiate each of these diagnoses, as the management is substantially different.

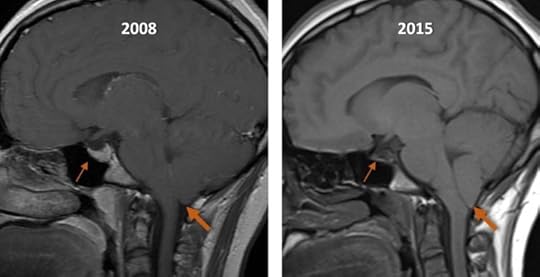

As an example, the figure below shows a patient with undiagnosed IIH imaged in 2008 (left image) whose chronically elevated ICP on re-imaging in 2015 (right image) resulted in increasing tonsillar ectopia (large arrow) as well as an increasingly “empty” sella turcica (small arrows). The appearance in 2015 could have easily been misdiagnosed as a Chiari 1 malformation.

Images provided by the author and used with permission.

Images provided by the author and used with permission.A few guiding principles are helpful in preventing the misdiagnosis of ICP disorders on imaging. First, the imaging findings should never be interpreted in a vacuum – the asymptomatic patient with an isolated nonspecific imaging finding is unlikely to have an ICP disorder. Any finding or constellation of imaging findings must be correlated with and fit within the context of the overall clinical picture. Second, the presence of multiple associated imaging findings associated with a disorder of ICP is more helpful than a single finding. Imaging can build a stronger case for a specific diagnosis when several findings associated with that condition are present, making it important for those interpreting the images to be aware of the full scope of imaging findings in each ICP disorder. Finally, open and constructive communication between radiologists and clinical specialists is key to correct diagnosis, starting with appropriate clinical information and ending with an appreciation by the radiologist of the clinical impact and context of the imaging diagnosis.

Featured image credit: progress, clinic, medical by sasint. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Preventing misdiagnosis of intracranial pressure disorders on diagnostic imaging appeared first on OUPblog.

Congregational singing in works written for Holy Week

The tradition of congregational singing in the Church stretches back centuries, and is still an integral part of any church service. However, congregations have historically been limited to only singing hymns and worship songs during a service, with any supplementary music performed by the choir.

Settings of music intended to be sung during Holy Week – the ‘Passions’, are no different; it is fairly unlikely that the famous Bach ‘Chorales’ were sung by the congregation. In light of this, it is interesting to consider and compare three works written for Holy Week – Alan Bullard’s Wondrous Cross, Bob Chilcott’s St John Passion, and Matthew Owens’ St Matthew Passion. Each of these works, to varying degrees, specifically make a point of including the congregation as part of the performance whether in a church service or a concert hall.

It is evident that although the approach of these three composers to composition and structure is individual, there are many similarities to their settings, perhaps influenced by the centuries of tradition preceding them. In particular, they all use well-known hymns and texts in the English Church tradition, including ‘There is a green hill far away’ and ‘When I survey the Wondrous Cross’.

Bullard’s Wondrous Cross is ‘A meditation on the traditional ‘Seven Last Words’ of Jesus Christ’, and uses words from the gospels of John, Luke, and Matthew, settings of ‘Ave verum corpus’ and William Leighton’s ‘In the departure of the Lord’, as well as including arrangements of well-known hymns for the congregation to sing when performed liturgically. Bullard also includes an arrangement of the American folk hymn ‘Were you there?’ where the congregation joins in the first and final verses (from a seated position):

‘Were you there when they crucified my Lord?

Were you there when they crucified my Lord?

Oh, sometimes it causes me to tremble,

Were you there when they crucified my Lord?’

The overall reflective character of this hymn arrangement allows the simplicity of the melody to shine through, especially as in the first verse all voices are in unison with only the organ providing harmony. The final verse also has voices in unison, but with a sympathetic descant line sung by the sopranos at first declaring ‘O were you there?’ after each line and then onwards from ‘it causes me to tremble’ harmonises with the rest of the voices.

Bob Chilcott also intersperses congregational singing throughout his St John Passion. The hymns are all settings of well-known Passiontide hymn texts: ‘It is a thing most wonderful’, ‘Drop, drop, slow tears’, Jesu, grant me this I pray’, ‘There is a green hill far away’, and ‘When I survey the Wondrous Cross’.

The texts and melodies of these hymns are intended to be included in services or programme notes for audience/congregational participation, which is especially helpful as Chilcott has composed elegant new melodies for each one.

The contemplative ‘Drop, drop, slow tears’ (Phineas Fletcher (1582-1650)) continues the imagery of crying from the previous movement ‘Meditation: Miserere, my Maker’ in which the choir sings:

‘And strengthen me now

In this, my ceaseless crying

Miserere, I am dying.’

‘Drop, drop, slow tears’ fittingly ends Part 1 of Chilcott’s St John Passion. During this hymn, the congregation sing the melody throughout but the choir accompaniment differs. In the last verse, instead of the usual descant in the sopranos, Chilcott uses a melody by Orlando Gibbons (1583-1625) to create an ‘inverted descant’ in the basses. With the congregation, upper voices, and tenors singing the hymn melody, this creates a more subtle (but very effective) change in the music.

‘Drop, drop, slow tears,

And bathe those beauteous feet,

Which brought from heav’n

The news and Prince of Peace.

Cease not, wet eyes,

His mercies to entreat;

To cry for vengeance

Sin doth never cease.

In your deep floods

Drown all my faults and fears;

Nor let his eye

See sin, but through my tears.’

Matthew Owens’ St Matthew Passion is the shortest of the three works, and contains just one congregational hymn, ‘When I survey the wondrous cross’ (Isaac Watts (1674-1748)). However, Owens splits the hymn across the piece: the first two verses are sung after the Evangelist sings:

‘Then he released for them Barabbas, and having scourged Jesus, delivered him to be crucified.’

The other three verses (including the usually omitted verse ‘His dying crimson like a robe…’) are sung at the end, building in voices with each verse:

Verse 3: Unaccompanied choir

Verse 4: Congregation, choir, and organ

Verse 5: Congregation and unison, with descant, and organ

Each time the congregation is required to sing, Owens attentively ensures the choir sing a verse before the congregation join in, allowing those not familiar, or unsure, of the tune to hear it first.

‘When I survey the Wondrous Cross,

On which the Prince of glory died,

My richest gain I count but loss,

And pour contempt on all my pride.

Forbid it, Lord, that I should boast,

Save in the death of Christ my God;

All the vain things that charm me most,

I sacrifice them to his blood.

See from his head, his hands, his feet,

Sorrow and love flow mingled down,

Did e’er such love and sorrow meet,

Or thorns compose so rich a crown?

His dying crimson like a robe,

Spreads o’er his body on the tree;

Then am I dead to all the globe,

And all the globe is dead to me.

Were the whole realm of nature mine,

That were a present far too small;

Love so amazing, so divine,

Demands my soul, my life, my all.’

In fact, all three composers use ‘When I survey the wondrous cross’ as the finale to their works, all including participation by the congregation, although Bullard and Chilcott both use the more widely-used four-stanza version.

This hymn text contains many personal pronouns, creating that individual connection whilst singing within a large group. The choice to end with this hymn, often heard on Good Friday, and inviting the congregation to join in with for the finale of the works allows a deeper connection between the words, the music, and even with the people in that space (be it a church or a concert hall), creating a shared experience you could not have on your own.

It is not surprising all these works use their settings of words and combined with the music, and all voices, in the final verses reach a triumphant and celebratory end of their telling of the Passion story.

Featured image credit: ‘Cross’. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Congregational singing in works written for Holy Week appeared first on OUPblog.

Marvellous murmurations

The following is an extract from Animal Behaviour: A Very Short Introduction by Tristram D. Wyatt and explains in detail how mumurations occur.

Shortly before sunset, especially in winter from October to February, flocks of tens of thousands of European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) fly in aerobatic displays called murmurations. The flocks swirl and morph, transforming from, for example, a teardrop shape into a vortex, and then into a long rope. The spontaneous synchronised flock turns as if of one mind. An early 20th century British bird watcher and author Edmund Selous was mystified how such big flocks could be so beautifully coordinated.

We now know that this kind of collective animal behaviour can emerge from relatively simple individual behaviours by each animal. This can produce complex, emergent behaviours larger than the parts.

The collective motion of flocks of birds (and other animals such as fish) can be modelled as a flock of self-propelled agents. The coordinated formations do not require ‘leaders.’ Each agent (animal) bases its own movement decisions on the positions, orientations, motion (or change in motion) of a few near neighbours. Using this local information, each agent follows simple rules to keep close but not too close, and align with and match the velocity of neighbours. While each agent reacts only with its neighbours, these interact in turn with their own neighbours, so a change in movement by an agent on one edge of the flock can ripple across it. The resulting simulated ‘flocks’ behave convincingly like real ones, changing shape, dividing and reforming.

A murmuration of starlings (3) by Adam. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.

A murmuration of starlings (3) by Adam. CC-BY-2.0 via Flickr.As murmurations of up to a million starlings form in the skies above Rome, featured in the BBC’s Planet Earth II, it’s proved to be a good place to test the theories. Andrea Cavagna and colleagues used stereoscopic photography and digital image processing to reconstruct the positions, tracks, and velocities of individual birds. The results have supported the theoretical idea that local interactions between birds can explain the flock’s movement, but surprisingly the real shape of the flocks is more like a sheet rather than the bulbous shapes we see them as from the ground. Another unexpected finding is that the flocks are densest towards the edges, and that flocks can differ more than two-fold in their density. This has lead researchers to propose that the birds respond to the nearest 6 or 7 neighbours, rather than only neighbours within a certain radius as models had often assumed before.

The speed and orientation of the starlings are highly correlated across the flock, no matter how big the flock, which accounts for the flock’s synchronized movements. When birds in one part of the flock are disturbed (by seeing a predator such as a hawk, for example), their individual response in change of direction and/or speed transmits as a wave across the flock, amplifying the change of direction by just a few individuals initially. Transmission of information in this way creates an effective sensory range for the flock far greater than the perception of any individual.

Featured image credit: Flock of Birds, Pigeons, Starlings by YvonneH. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post Marvellous murmurations appeared first on OUPblog.

April 6, 2017

April 1917: the end of American neutrality in WWI

Despite President Woodrow Wilson’s efforts to remain neutral, the United States declared war on Germany on 6 April 1917. Initially, the American public largely supported neutrality. But by 1917, many Americans strongly supported the war, believing that it was the responsibility of the United States to protect the right to freedom and democracy around the world.

In this excerpt from The Path to War: How the First World War Created Modern America, historian Michael S. Neiberg captures the American public’s opinion on WWI through the lens of writer Mary Roberts Rinehart. Often referred to as the “American Agatha Christie,” Rinehart was well-known for her mystery novels and regular contributions to The Saturday Evening Post. Using the magazine as a platform, Rinehart shared why she—as a mother and an American—supported America’s entry into WWI.

Mary Roberts Rinehart’s journey since 1914 perhaps best represents the mood and the moment of April 1917. She had been one of the first Americans to urge a more assertive posture toward the war. Two years earlier, Rinehart had written that although she supported the United States taking a more active pro-Allied stance in the wake of the Lusitania tragedy, she was glad that her sons were then too young to fight if it came to war. She had hoped then that the war would end before she had to face the prospect of a son going off to fight the war that she had advocated.

Now, in 1917, her older son was old enough to fight, and Rinehart took to the pages of the Saturday Evening Post to explain not just her support for a war that nevertheless terrified her, but why she would not want her son to try to evade the military service that might kill him. “If in this war we allow the few to fight for us, then as a nation we have died and our ideals have died with us,” she wrote. “Though we win, if we all have not borne this burden alike, then do we all lose.”

Although her article was ostensibly about the roles of citizens and motherhood in time of war, it highlighted many of the themes that had been running through American thoughts on the war since 1914. Writing in late March 1917 she told her readers, “We are virtually at war. By the time this is published perhaps the declaration will have been made.” America, she believed, was “the last stand of the humanities on earth, the realization of a dream and the fulfillment of an ideal.”

Mary Roberts Rinehart circa 1914 by Theodore C. Marceau. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Mary Roberts Rinehart circa 1914 by Theodore C. Marceau. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.Britain and France both shared parts of that ideal and had had a foundational role in creating it. Since 1914, they had been fighting for “the ideal on which my country was founded.” Under the domination of the Prussians, imperial Germany now threatened those values, not only in Europe but in America itself, for it “had broken loose something terrible, something that must be killed or the world dies.”

America should have awakened to these realities in 1915, but it did not. Now it had to face them under far more adverse conditions, having lost two precious years to get ready. Since the sinking of the Lusitania, the American people, she noted, had gone to church on Sundays and given thanks to God that “we were out of it” when they should have been listening to the warnings of those saying that the United States had to get ready for the looming crisis on the horizon. Instead, Congress had “refused to listen to talk of preparation” and the American people had refused to force them to do so. As a result, millions of young men, including her own son, would now go into history’s most devastating war without the training and equipment that they needed.

Rinehart concluded with two more observations based in America’s experiences since 1914. In the first she reiterated her belief from her tour of the Western Front that the United States must make war on the German government, not the German people. “There is no great hatred of the enemy, however much we abominate the things the German government has driven an acquiescent people into doing.” The United States should therefore not fight to destroy Germany, but to liberate it from the brutality of a regime that threatened to destroy civilization itself. Second, she wrote that she had no worries at all about the loyalties of the Germans living inside the United States. German-Americans “are not Huns or Vandals. The German we know has come here to escape the very thing that has wrecked the Old World…In coming to this Land of the Free he has followed an ideal as steadily as back in the Fatherland his kindred are following the false gods of Hate and War.” The war itself, however, would put such views to the test.

No one put the American experience of 1914–17 into sharper focus than Rinehart had, perhaps not even President Wilson in his eloquent declaration of war speech on April 2. As millions of Rinehart’s fellow Americans understood, the United States had drifted to “the verge of war, in an uncertain attitude” that was neither enthusiasm nor resignation. It was rather the acknowledgment that they no longer had a better choice and that by failing for so long to confront reality they had put themselves in an even more dangerous position. Noble impulses like charity, neutrality, and mediation had all run their course and war stood as the only option remaining. What Samuel Price called “the beastly passions for blood” would now put an end to the indescribable interval of uncertainty. The nation, and the world, would never be the same.

Featured image credit:”The American Army in France during the First World War” released by the Imperial War Museum. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post April 1917: the end of American neutrality in WWI appeared first on OUPblog.

Understanding stress and anxiety

Almost everybody experiences some stress and associated anxiety on a regular basis. While not particularly comfortable, these reactions can be valuable in alerting us to pay extra attention when we perform important tasks or find ourselves in high-risk situations. Sometimes, however, the stress response is triggered too easily or too intensely, causing unnecessary discomfort. In these cases, it helps to learn techniques to regulate the stress response.

As part of a blog series on managing stress during this April for Stress Awareness Month, we begin with this brief explanation of what stress is, how it is caused, how it can be recognized, and how it is related to anxiety.

What is Stress?

Stress occurs when the demands we place on ourselves, or others place on us, exceed our ability to comfortably meet them.

Much of the stress we experience is useful, and even enjoyable, in that it energizes us, challenges us, and helps us grow stronger. Think, for example, of a runner pushing herself to go a little faster than is comfortable or a retiree going back to school.

While short-term or mild-intensity stress can be good for us, prolonged or intense stress is generally not. In fact, such stress is known to impair health, happiness, and productivity.

Researchers have shown, for example, that this type of stress can disrupt the immune system and contribute to cardiovascular disease. Stress can impair brain functions such as memory. In persons with chronic pain, stress tends to increase suffering. Stress makes it harder to resist addictive urges. Intense or prolonged stress can also reduce our ability to work efficiently and decrease our sense of well-being.

How to recognize stress

Stressed by caio_triana. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.

Stressed by caio_triana. CC0 public domain via Pixabay.Change is generally a source of stress, so be on the lookout when your circumstances change in some way. Be especially on the lookout when the changes aren’t under your control. Unwanted changes, such as illness or injury, are easily recognized as sources of stress. However, even desired changes, such as a promotion at work or a new relationship, can be stressful.

Common sources of stress include:

Injury, illness, or chronic pain

Loss of a job or other important role

Loss of a loved one

Relationship breakup or conflict

Work and family demands

Money problems

Traffic, long lines, and other hassles

Responses to stress

In response to increased stress, many symptoms can occur, including:

Feeling overwhelmed

Feeling anxious

Having mood swings

Feeling irritable and/or having anger outbursts

Feeling run down and tired

Experiencing reduced sexual desire

Developing muscle tension, headaches, stomach aches, back pain, or neck pain

Having problems with attention and memory

While stress sometimes leads to irritability or depressed mood, anxiety is the most common emotional response to intense or prolonged stress. In fact, stress and anxiety so often occur together that some people use these terms interchangeably. Anxiety can be experienced in various ways, including:

Worrisome thoughts

Feelings of fear, unease, or dread

Desire to avoid what is feared

Distressing dreams associated with the fear

Trouble falling asleep

Difficulty concentrating

Physical reactions such as muscle tension, sweating, trembling, and changes in breathing and heart rate

Unhealthy behaviors often increase in times of stress. Some of these unhealthy behaviors are performed to suppress anxiety or other uncomfortable emotions that accompany stress:

Overeating

Smoking

Consuming alcohol or other substances excessively

Sleeping too much

Other unhealthy behaviors occur because stress-producing life demands leave less time, energy, and willpower for healthy self-care:

Unhealthy eating or not eating

Not exercising

Not sleeping or resting enough

Using excessive amounts of caffeinated beverages to compensate for lack of sleep

Some stress is good for us; prolonged or intense stress is not. By becoming better at recognizing causes, signs, and symptoms of stress and associated anxiety, we can be more prepared to use the coping skills presented in the next three posts in this blog series.

Featured image credit: 24 hours sleep stress by Edu Lauton. Public domain via Unsplash.

The post Understanding stress and anxiety appeared first on OUPblog.

What if Peter Pan’s arch-enemy was a woman?

J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan; or The Boy Who Would Not Grow Up has exercised the popular imagination since its first performance in 1904. Yet not everyone is aware of Peter Pan’s stage history or the darker currents that underlie the apparently escapist story of Wendy Darling and her brothers flying away from their nursery to the “Never Land”, a fantasy world of make-believe and adventures with Captain Hook and his pirates, mermaids, and other characters drawn from children’s games. Sally Cookson’s production at London’s National Theatre in the winter season 2016-17 returns to the darker roots of Peter Pan, reaching back beyond its first performance to Barrie’s earliest notes towards the play, where he imagined Captain Hook, Peter’s arch-enemy, being played by a woman.

Captain Hook is traditionally played by the same actor who played Mr. Darling, Wendy’s father. This adds an extra layer to the children’s “escape” to Never Land, and underlines the idea that they are acting out roles and relationships from the “real” world. The villainous pirate captain doubling the father who works in a bank may suggest that the children are revolting against the prospect of a nine-to-five job and a programmed adult existence. As Peter says towards the end of the play: “Would you send me to school? … And then to an office? … I don’t want to go to school and learn solemn things. No one is going to catch me, lady, and make me a man. I want always to be a little boy and to have fun!” In early performances these lines would cause young men in the audience to cheer and stamp their feet. But it is far from clear how the flamboyant Captain Hook incarnates the bourgeois values that Peter rejects.

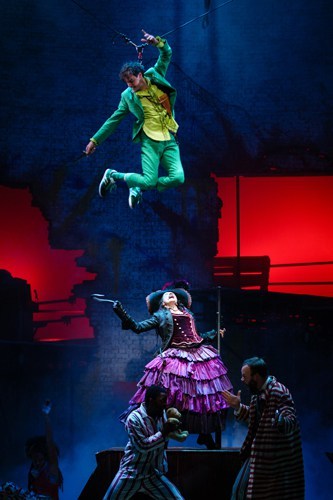

In her National Theatre production (first performed at the Bristol Old Vic in 2012), Sally Cookson digs into Peter Pan’s textual history to stage a different kind of doubling for Captain Hook, and a different symbolic interpretation of the antagonism between Hook and Peter. In Barrie’s original notes towards the play he jotted: “Pirate Captain — Miss Dorothea Baird (‘See how he scowls,’) His awful ugliness much insisted on.” Dorothea Baird played Mrs. Darling in the first run of Peter Pan but Barrie never acted on the idea of having her double with the role of the pirate captain, even though the play has a long history of cross-dressed roles: until quite recently, the character of Peter Pan himself was always played by a woman.

Peter Pan at the National Theatre, a co-production with Bristol Old Vic © Steve Tanner. Used with permission

Peter Pan at the National Theatre, a co-production with Bristol Old Vic © Steve Tanner. Used with permissionThe idea of Mrs. Darling doubling as Captain Hook seems to tie in, as Andrew Birkin has commented, with another relic from the developmental stages of the play. Peter Pan had many different titles in its draft stages, and at one point its full title was Peter Pan; or The Boy Who Hated Mothers. Peter’s hatred of mothers is still evident in two scenes of the play as we know it. Wendy and her brothers, having flown out of their nursery window to arrive in Never Land, finally decide to go home after Wendy tells a story that imagines their return. The story ends: “‘See dear brothers,’ says Wendy, pointing upward, ‘there is the window standing open.’ So up they flew to their loving parents, and pen cannot describe the happy scene over which we draw a veil.” But Peter counters this projected happy ending with a chilling story of his own: “Wendy, you are wrong about mothers. I thought like you about the window… and then I flew back, but the window was barred, for my mother had forgotten all about me and there was another little boy sleeping in my bed.”

Peter’s version establishes the mother as an enemy whose actions are to be feared. What’s more, Peter seems to be engaged in a battle with Mrs. Darling for the affections of Wendy and the others. After Wendy’s story, the children fly back to London, but Peter flies faster and gets there first. The nursery window is open but Peter rushes to close it, saying, “Now when Wendy comes she will think her mother has barred her out, and she will have to come back to me!” Confronted by Mrs. Darling’s tears he observes, “she is awfully fond of Wendy. I am fond of her too. We can’t both have her, lady! Come on, Tinkerbell; we don’t want any silly mothers!”

If Captain Hook is played by the same actor as Mrs. Darling, the struggle between Peter and Wendy’s mother for possession of Wendy becomes central to the play. Sally Cookson’s casting gives scope for all sorts of potential interpretations. She perhaps misses a trick by making Hook a female pirate captain rather than playing with the cross-dressing suggested in Barrie’s original note. But she brings to life a layer of the play that has been hidden since its pre-history, and gives the (female) actor playing Hook a much richer character to work with.

Featured image credit: Scene from Peter Pan where Peter (Mary Martin) shows the Darling children he can fly by Rothschild, Los Angeles. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post What if Peter Pan’s arch-enemy was a woman? appeared first on OUPblog.

National Beer Day – who said what? [quiz]

National Beer Day is celebrated every year in the United States, on 7 April. It marks the day that the Cullen-Harrison Act came into force, after being signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on 22 March 1933. The law meant that the American population were once again able to buy, sell and drink beer (of up to 3.2%), in states that had passed their own legislation allowing such deals. Predictably, there were great celebrations across the country, with people congregating outside breweries all through the night, ready to imbibe their first taste of the hops. Although this wasn’t the official end of prohibition, a staggering 1.5 million barrels of beer were consumed on that first day alone – inspiring the eponymous holiday.

On signing the legislation, Roosevelt made his famous remark “I think this would be a good time for a beer”. With Roosevelt’s words ringing in our ears, we thought this would be a good time to test your knowledge of beer quotes. Do you know which company coined the slogan “I’m only here for the beer”, or who described prohibition as making you “want to cry into your beer” whilst denying you “the beer to cry into”?

Quiz and featured Image Credit: ‘Cheers, Beverage, Drink’ by Unsplash, CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post National Beer Day – who said what? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

April 5, 2017

Beating about an etymological bush: the story of the word “carouse”

In a way, this is the continuation of the previous week’s gleanings, because I owe today’s subject to a question from a student of Old English. Although I cannot say anything new about carouse, the story is mildly instructive.

Greeting formulas have probably existed in all societies at all times. Theoretically, since salutations used at presenting a drink to a guest are predictable and formulaic, they should be more or less the same all over the world, but they are not. One formula, recorded already in Old English, has given rise to the word wassail (from “be whole,” that is, “be healthy”; Middle Engl. wassayl). Some such phrases are astoundingly obscure (for instance, mud in your eye); others, even when they look transparent, may defy an easy explanation: here is how and Italian chin-chin are among them. Only your health! needs no etymology: it means what it says. Bottoms up and no heeltaps also tell their story quite clearly.

Mud in your eye, or chin-chin.

Mud in your eye, or chin-chin.In English, carouse became known at the end of the sixteenth century, just in time for the authors of our first etymological dictionaries—Minsheu (1617) and Skinner (1671)—to include it. Both gave the correct origin of what appears to have been a relatively recent word: they traced it to German garaus, that is, gar aus, as used in the phrase garaus trinken “to drink, quaff completely, to the bottom.” A similar formula made its way into French. Rabelais knew it. He wrote voir (= boire) carous et alluz. All out, with the adverb out corresponding to German aus, has also been recorded in English. Some researchers believe that the German phrase reached England from France. This is possible but cannot be proved “beyond reasonable doubt.” The famous philologist Gilles Ménage offered the same derivation of carous in his etymological dictionary of French (1650) that we find in Minsheu. Whatever the source of the English word (German or German via French), such a formula must have been borrowed orally, rather than from books. For a while, even the form garaus, with initial g-, had some currency in English. There were enough tipsy Germans all over the continent to make their “wassail cry” widely known. An additional proof of the popularity of German drinking formulas is the existence of Italian brindisi “health, pledge, toast,” from German bring dir’s (= bring dir es), literally, “(I am) bring(ing) it to you.”

The rest of the story is curious only in that it shows the workings of an erratic human mind and how people suffer from self-inflicted wounds. Unfortunately, later etymologists did not believe Minsheu, Ménage, and Skinner. Perhaps some of them had no access to the early dictionaries, but I doubt it, for Skinner and Ménage circulated widely, and, unlike what happens today, reference works were extremely few. Also, at that time, etymological entries often contained nothing but the opinions of the author’s predecessors.

Noah Webster brought out his dictionary in 1828. He wrote: “I know not the real origin of this word. In Persian karoz signifies hilarity, singing, dancing. In German rauschen to rush, fuddle. In Irish craosal is drunkenness, from craos excess, reveling.” Webster taught himself numerous languages but missed the birth of modern philology; hence this aimless wandering all over the world in search of look-alikes.

The word rouse, which early dictionary makers knew from Shakespeare, means “bumper, large drinking glass,” and there were attempts to derive carouse from rouse. The origin of this rouse is not quite clear. It may be a so-called aphetic form of carouse. (An aphetic form is the product of clipping: fend, as in to fend for oneself, from defend; mend from amend; ‘cause from because; lone from alone; cute, from acute, and the like.) As can be seen, the lost part is usually a prefix. Carouse has no prefix, but words resembling caboose and caboodle, with final stress, perhaps existed even at the time, and in r-less dialects, the likes of curmudgeon and kerfuffle sounded, as though they began with ca-. Thus, carouse perhaps did yield rouse, but the movement in the opposite direction, from rouse to carouse, is improbable.

This is a bumper. See the etymology of bumper in the post for 12 December 2012.

This is a bumper. See the etymology of bumper in the post for 12 December 2012.The greatest of the old English etymologists was Franciscus Junius (1599-1677). His dictionary, edited by Edward Lye, appeared posthumously, in 1743. Junius, a native speaker of Dutch, made numerous astute remarks, while connecting English and Dutch words. In his discussion of carouse (naturally, in Latin), he cited Engl. ruse, which he traced to Dutch ruyschen (modern spelling: ruisen) “to make a roaring noise.” Lye added German Reuse “fish trap” to the list. In the story of rouse and carouse, ruse and Reuse can be ignored as certainly irrelevant. But the German cognate of Dutch ruisen is rauschen (the same meaning), and from this verb the noun Rausch “intoxication” has been formed. The verb’s origin is unknown (sound-imitative?); some authorities compare Engl. rush “to dash forward” with it. Carousing and intoxication go together quite well.

Several ideas, mentioned above, are clever, even though we know the answer and realize that carouse has a different origin. Their most obvious weakness is that they do not account for the first syllable of carouse, but it is curious how the vocabulary of conviviality absorbed such similar-sounding words as German Rausch, Engl. rouse, and Engl. carouse; roaring (Dutch ruisen) belongs with that group quite naturally. One could even risk the hypothesis that during the interminable wars of the Early Modern period (think of the Thirty Years’ War, 1618-1648), European mercenaries used some sort of lingua franca, understood in taverns all over Europe, but that would have been a secondary development.

![An ideal place for developing the [premodern] lingua franca of good life.](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491486288i/22415278._SX540_.jpg) An ideal place for developing the [premodern] lingua franca of good life.

An ideal place for developing the [premodern] lingua franca of good life.A few more futile attempts to derive carouse from some noun are known. In the late eighteen-forties, Hensleigh Wedgwood, the main etymologist of the pre-Skeat era, traced carouse to Dutch kroes “cup,” still another word that aligns itself perfectly with carouse, rouse, and the rest. We find this suggestion in the first edition of his dictionary (1859), but he soon saw the light (under the influence of Mahn? See below) and in the three subsequent editions made a statement that his early derivation of carouse had been wrong. I was unable to discover under what circumstances Webster’s reference to Irish craos “excess, revelry” (apparently, a word borrowed from English) reemerged in another form. One respectable dictionary after another (Worchester, Chambers, and Stormonth) cited Irish craos “large mouth; revelry” as the etymon of carouse. The last to do so was Charles Mackay, who wrote good poetry and studied Shakespeare’s language and Scots with great profit, but one day decided that most words of English and other European languages go back to Irish Gaelic, the language he knew very well. The result of his delusion was a dictionary full of useful surveys and crazy ideas. He, not unexpectedly, also fell for the craos – carouse connection.

Has it been an instructive or a disheartening travel? The solution lay in full view already on Day One. There was no sphynx, no riddle, but scholars made wide circles around the obvious, deviating farther and farther from the right answer. Although Webster-Mahn adopted the correct etymology as early as 1864, this fact did not deter many learned people from roaming in the gloaming. The truth is rather simple (“all out with it”), while the guesses have been audacious and brilliant. Truth often suffers from excessive zeal, for it may look modest in comparison with the glitter of false hypotheses.

Roaming in the gloaming.

Roaming in the gloaming.I also meant to say something about carousal and carousel, but this is a different story. Carouse alone is a tough customer.

Image credits: Featured image & (1) “Glasses, sparkling wine” by Holger Detje, Public Domain via Pixabay (2) “Beer” by Alexandra, Public Domain via Pixabay. (3) “Soldiers playing dice in a tavern” by Adriaen Brouwer, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. (4) “Silhouettes” by skeeze, Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Beating about an etymological bush: the story of the word “carouse” appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers