Oxford University Press's Blog, page 377

April 19, 2017

Still sinning, part 2

Today I am beginning where I left off last week. As we have seen, Old Icelandic sannr meant both “true” and “guilty.” Also, the root of this word can be detected in the word for “being” (Latin sunt, etc.). Many ingenious explanations of this strange symbiosis exist. In what follows I will have to repeat some of the statements made a week ago.

Guiltless and not guilty.

Guiltless and not guilty.One thing is probably incontestable: we are dealing with legal, rather than philosophical, notions. What is truth and what is a lie? It has been noticed that in the Indo-European languages and even beyond, words for “truth” are always derived, while words for “lie” are not. English is no exception: truth is derived from true (-th is a suffix, as in length, width, and breadth), while lie is a simplex. I assume that lie denoted some basic concept, while truth was understood as the opposite of lie (a curious reversal of what seems natural to us). It may also not be a coincidence that the etymology of the words for “truth” is usually transparent, while the etymology of lie is often (and definitely so in Germanic) obscure or even impenetrable.

Engl. lie has easily recognizable cognates everywhere in Indo-European (similar form, similar meaning), but the words for “true” differ from language to language. It seems that they were coined or at least acquired their meaning later. For instance, the Latin for “true” is verus (compare Engl. very, verily, verification, etc.). The root of its Slavic congener, familiar from the female name Vera (“faith”) means “to believe.” Thus, in Slavic, “true” means “believable, credible, trustworthy.”

Even though words for “truth” and “lying” were initially legal terms, “legal” does not refer to litigation only. It describes the individual’s entire complex of relations to society. An illuminating example is pravda, the Russian word for “truth,” known to many from the name of the central newspaper of the Soviet era. In older Russian, it also meant “legal code.” But why did Old Icelandic sannr mean both “true” and “guilty”? Words tend to develop opposite or incompatible meanings, because ambiguity is inherent in a good deal of what we say. Thus, compromise refers to an agreement (“we reached a compromise”: everybody is happy), but, when you are compromised, the sense of compromise is negative. Gratuitous means “requiring no payment” (which is excellent: compare gratuitous medical assistance), but gratuitous cruelty is not such a good thing. There is no love lost between them used to mean “they are friends” (of course: no love has been lost between them!), but the idiom was misinterpreted (“so little love exists between them that there is nothing to lose: they are enemies”). Latin altus means both “high” and “deep”: everything depends on the direction of one’s gaze. Something along such lines must have happened in the history of sannr and its cognates. The defendant was guilty because he had to disprove the accusation of guilt. By successfully disproving it, he emerged as someone revealing the truth. The most important Icelandic verb related to sannr is synja “to deny.” “Able to deny” meant “true.”

No love lost between them.

No love lost between them.What then is a lie? This looks like another legal term. Perhaps the most revealing cognate of lie is Latvian lùgt “hidden.” But, in order to understand what a lie is, we should return to medieval Scandinavia. In one of the best-known mythological songs of The Poetic Edda (which is a collection of such songs), the great god Thor (Þórr) wakes up and discovers that his hammer has been stolen. Without the hammer the gods are defenseless and will be conquered by the giants. Loki, another god, flies to Giantland, the place where the hammer, most likely, will be found, and, when he returns home, Thor begs him to share the news while he is still in the air, because, as he explains, he who sits often forgets the story, and he who lies tends to deal in lies. In Icelandic, the pun on lies—lies, though less clear than in English, is also unmistakable. The implication of Thor’s request must be that, if the messenger waits too long, he will forget some details and the information will no longer be fully reliable. From one tale to another this sense of “lie” comes to the foreground with great regularity: lie means “unreliable or unproven information” or “the information shown to be false,” rather than deliberate deception.

This is Thor’s hammer Mjöllnir. It keeps the giants at bay. No lies about it can be tolerated.

This is Thor’s hammer Mjöllnir. It keeps the giants at bay. No lies about it can be tolerated.This then is the picture, as it emerges from the study of Old Germanic texts and institutions. Life looked like a gigantic court. The laws were numerous, and litigation was unceasing. In this respect, we are neither better nor worse off than those who inhabited the European continent a millennium ago. Everyone was a potential defendant. Accused of guilt, this person denied it and revealed the truth. That is why related words designated truth, guilt, and denial. Sometimes even the same word combined both meanings. Old Engl. syn, mentioned last week in the phrase syn and sacu, meant “fault, crime”; “denial” was one of its senses. Outside English, the cognates of the same noun syn, when coupled with the word for “need,” meant “an excuse for not appearing at the court proceedings.” After the conversion, the cognates of syn were chosen all over the Germanic-speaking world to designate “sin.” The new meaning ousted the previous ones. The original syn/sin came to an end.

What remains to be understood is where “being, existing” comes in. Such abstract notions as “being” are hardly ever initial. The older a language is, the more obviously it combines a highly complicated grammatical system (everything has to be differentiated: the singular from the plural, the plural from the dual; the first person from the third, and so forth) with the paucity of abstract notions. Its vocabulary may have numerous color words but no word for “color.” The branch of scholarship called anthropological linguistics studies exactly such things. In the remote past, “to be” also had a more concrete referent: it must have meant approximately “to answer for one’s actions.” At that time, no one would have coined the phrase the intolerable lightness of being.

We should not disregard a problem in this reconstruction. In its treatment of guilt and being, Latin presents a close analog of Germanic. Consequently, the terms we treat as Germanic might have acquired their meaning under the influence of Latin, because the medieval Germanic codes known to us are relatively late and often reflect the system learned from the Romans. But the picture will remain the same, regardless of the circumstances in which it came into “being.” According to an ingenious idea, the Latin-Germanic situation resembles a game, when people say to somebody: “You are It!” The result is both “you exist” and “you are guilty.” Perhaps there is no need to be so concrete.

As a postscript, I may add that in the Old English phrase syn and sacu, sacu means approximately the same as syn (“crime, contention”; its Icelandic cognate means “attack”—the whole is a typical alliterating tautological binomial of the safe and sound type). In the modern language, this word also acquired a much more general sense: for example, German Sache means “thing.” The only trace of sacu in English is sake, as in the phrase for the sake of, but even this phrase may be a borrowing from Scandinavian. And this is the end of the short series on living in and without sin.

Image credits: (1) “Guilty Eye Up Guy Look Baby Really Cute Sad” Public Domain via Max Pixel (2) “High School Boxing Match Oak Ridge” 4305 DOE photo by Ed Westcott, Public Domain via Flickr. (3) “Thor’s hammer, Bredsättra, Öland” by Unknown, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. Featured image credit: “The instance Sinodal`niy of Pravda Ruskaya page 1” by Греков Б.Д., Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Still sinning, part 2 appeared first on OUPblog.

The best of all possible worlds

Voltaire is known today for Candide, a short novel published in 1779. The young hero Candide travels the world in a tale littered with rape, murder, pestilence, enslavement, and natural catastrophe. Amidst this apocalyptic nightmare, Candide’s tutor Dr Pangloss maintains a philosophical detachment, arguing against all evidence to the contrary that we live in the best of all possible worlds. The purpose of this strange tale was to demolish a theological position held by the philosopher Leibniz caricatured as Dr Pangloss, and this objective was certainly achieved. So how did Leibniz come to be identified with such a world-view?

The story begins in antiquity with Hero of Alexandria, a brilliant engineer and mathematician in the days of the first Roman emperor Augustus. His works survive in scattered fragments that describe ingenious devices such as vending machines, wind-powered pipe-organs, and even a simple steam-powered gadget, the aeolipile, named after the Greek wind god Aeolus.

A scene from the opera Candide by Leonard Bernstein. (School of Music, The University of South Carolina.) Reposted with permission.

A scene from the opera Candide by Leonard Bernstein. (School of Music, The University of South Carolina.) Reposted with permission.Hero also wrote the Catoptrica (theory of mirrors) in which he attempted to explain why light rays follow straight lines. He proposed that a light ray travelling between two points takes the path that minimizes the time taken, and noted that if light travels at a constant speed, then the quickest route is also the shortest route – a straight line. In other words, any other path that the light ray might have followed would have taken longer than the actual path. Hero showed that this optimization principle would also explain why the angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection when an image is reflected from a mirror.

In 1662, Pierre de Fermat extended Hero’s idea to explain refraction. When passing between different media, such as air and water, the path of a light ray bends at the interface between the media. According to Fermat, this is because light travels slower in water than in air, so the quickest route is not perfectly straight; it has a longer straight segment in the faster medium and a shorter straight segment in the slower medium. Fermat used this argument to derive Snell’s law and explain how lenses work. In Fermat’s day, the speed of light had not been determined in any medium so his proposal was rather speculative, but it proved to be correct.

A laser beam fired from the top left into a tank of water. The beam is partially reflected from the surface of the water, with the angle of incidence equalling the angle of reflection, and the transmitted beam is refracted at an angle to the incoming beam. Image by Towert7 and reposted with permission.

A laser beam fired from the top left into a tank of water. The beam is partially reflected from the surface of the water, with the angle of incidence equalling the angle of reflection, and the transmitted beam is refracted at an angle to the incoming beam. Image by Towert7 and reposted with permission.Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz is credited with being the first to realise the wider significance of optimization in physics. Although this approach to mechanics was not perfected until the 19th century, Leibniz’ account survives in a letter from 1707.

The motion of a body such as a cannonball, subject to known forces, may be calculated using Newton’s laws of motion. This is often expressed in terms of changes in its kinetic energy K and potential energy V, where its total energy is E = K + V. The key to the alternative optimization approach to mechanics is the Lagrangian, L = K – V, defined as the difference between the kinetic and potential energy. Integrating the Lagrangian over a path produces a quantity known as the action. When this is calculated for the path that a body follows through space, it is smaller than for any other path the body might have taken. This is the principle of least action. It means that the trajectory of a material body can be predicted by finding the path that minimizes its action (It is worth noting that in some circumstances a trajectory is determined by maximization of the action rather than minimization, and also that the optimization of the action is local and not necessarily absolute. In other words, the trajectory optimizes the action compared to neighbouring paths).

Newton’s laws of motion can be derived from the principle of least action, so the optimization approach is completely equivalent to Newtonian methods. But the principle of least action is more fundamental with much wider application. For instance, Maxwell’s equations for electric and magnetic fields can be derived from an action principle, and so can the Einstein equation, which describes gravity as curved space-time. Indeed, the action lies at the heart of theoretical physics. It is essential when formulating the incredibly successful modern theories of elementary particles, such as the Standard Model, and even the more speculative and esoteric theories of strings.

This raises the question of why such optimization principles should hold. How does a beam of light know which route is quickest? How does a cannonball know that by tracing out a parabola it is minimizing its action? Leibniz thought that he knew the answer and saw it as firm evidence for God’s creative power.

Leibniz agreed with Thomas Aquinas and other philosophers that even an all-powerful God must be constrained by the laws of geometry and logic. It would therefore be impossible for God to create a world containing logical contradictions. But this necessarily means the world includes some bad as well as good. So, although the world cannot be flawless, it must be the best of all possible worlds. Leibniz saw the optimization principles of mechanics as clear evidence of God’s role in the optimization of the universe.

However, as Bertrand Russell pointed out, it is a short step from here to an argument claiming that this must be the worst of all possible worlds. If the world was created by a malevolent demiurge, perhaps humans were given consciousness to maximize awareness of their suffering. Leibniz was lampooned mercilessly by Voltaire and since Candide, rational arguments for God’s role in the world have lost much of their force.

It is remarkable that so much physics can be described in terms of optimization principles. We now have a far better understanding of the origin of the action principle, and it is all due to quantum mechanics.

A version of this post originally appeared on Quantum Waves Publishing.

Featured image credit: Laser by SD-Pictures. Public domain via Pixabay.

The post The best of all possible worlds appeared first on OUPblog.

Libraries: The unsung heroes in A Series of Unfortunate Events

This January, Lemony Snicket’s first four critically acclaimed novels of the A Series of Unfortunate Events were adapted as a Netflix original series, starring Neil Patrick Harris. Although famously known as a book series built upon three children’s misery and misfortune, the stories do contain one consistent factor on which the kids can always rely: the library. To stay consistent with the current season available on Netflix, here is how the libraries in these first four books are the unsung heroes in A Series of Unfortunate Events.

Libraries help the Baudelaires foil the evil Count Olaf’s plots

In the first book, The Bad Beginning, the Baudelaire children take advantage of their neighbor’s home library. The library provided them with necessary information to properly prepare a dinner for their at-the-time guardian, Count Olaf, and his acting troupe, and it was also the place that allowed them to find a way to nullify a marriage that would have changed their lives drastically. Had it not been for Klaus discovering a book on Nuptial Law, Violet Baudelaire would have been forced to marry Count Olaf and thereby give him all the rights needed to obtain the Baudelaire fortune.

Libraries offer the children an escape from their miserable reality

In the second book, The Reptile Room, the library takes the form of a reptile center where the kids are able to not only read about all of their uncle’s findings on reptiles, but also play and interact with them. It’s moments like these that offer a short respite from the relentless melancholy that has an unyielding grip on the Baudelaire children.

Libraries advance the plot

The third installment of the series, The Wide Window, is the first time the children acquire some clues that aid them in solving their parent’s murder. Inside their Aunt Josephine’s library, they find a picture where they see their parents and family friends standing outside of Lucky Smells Lumbermill. After successfully escaping, once again, from Count Olaf’s clutches, the children stow away on a truck in hopes of reaching the mill in the picture. The children are desperate for answers and are hopeful that the mill will have the information needed for them to finally solve the mystery behind the fire that killed their parents.

Libraries aid the children in discerning lies about their parents

In the fourth installment of the series, The Miserable Mill, the Baudelaire children arrive to Lucky Smell’s Lumbermill where they are told that their parents caused a massive fire that left the mill in its current, decaying state. Unwilling to accept that their parents were capable of such a horrible action, the children turned to books for more information. Using the landowner’s small, quaint library, Violet Baudelaire finds an untainted copy of the lumber mill’s history, where she reads that her parents were, in fact, saviors of the mill rather than arsonists. Thanks to this library, the Baudelaire children were able to acquire the trusted information needed in order to restore their family name.

Lemony Snicket’s libraries play a quintessential role in the lives of the Baudelaire children. They not only keep the children well-informed, but they also keep them safe and free from Count Olaf’s evil clutches. Without the libraries, this book series would have concluded after the first installment with the children succumbing to Count Olaf’s nefarious affairs. Thank you libraries for the various ways you help these children carry on with their despair-plagued lives!

Featured image credit: “Library” by Unsplash. CCo Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Libraries: The unsung heroes in A Series of Unfortunate Events appeared first on OUPblog.

Raiding religion, the new normal

The nineteenth of April 2017 is the twenty-fourth anniversary of the 1993 Branch Davidian tragedy in Waco, Texas. The disaster began three months earlier, however, with a botched effort by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms to serve a search warrant for weapons upon a small religious community. The raid resulted in fifteen casualties among federal agents, including four dead, and the deaths of six Branch Davidians.

After 51 days of negotiations between the FBI and the group, the late Attorney General Janet Reno authorized the use of force to end the stand-off. Police and military units using army tanks inserted CS gas into the building, destroying the walls behind which Davidians sought shelter. Reno had hoped the gas would encourage residents to leave the building and peacefully surrender, without loss of life. Instead, a fire broke, out and 76 Branch Davidian men, women, and children died.

While the militarization of police action against the Branch Davidians was shocking at the time, the use of such tactics has dramatically escalated in the intervening decades. Stuart Wright and Susan Palmer reported on this disturbing phenomenon, documenting 116 state raids occurring in 17 different countries over the last sixty years, with 77% occurring since 1990. Their study centered on incursions in North and South America, Australia, Israel, and Western Europe, although various human rights groups have chronicled this as a global phenomenon.

The problem of government assaults on religious groups persists to this day. The most recent raid was this past February, when Russian officials stormed Jehovah’s Witness headquarters and confiscated some 70,000 documents. Last November, German security forces combined to bust more than 190 homes, businesses, and mosques connected to the purportedly radical jihadist group True Religion. That same month, Turkish police arrested more than 70 academics who are members of Hizmet, the group which follows Imam Fetullah Gülen. This followed the July crack-down following an unsuccessful coup attempt in Turkey which led to the detention of 36,000 people who still await trial.

Closer to home, the Southern Poverty Law Center reported that the FBI and local police raided the headquarters of the Israelite Church of God in Jesus Christ late last year. The black supremacist group—part of the tradition of Hebrew Israelites—preaches an anti-white and antisemitic message. It was not clear why a search warrant was issued, though one news source claimed financial irregularities were involved.

News media frame these and other incidents as justifiable uses of force against criminal, rather than religious, organizations. And perhaps they are legitimate attempts to protect the public from dangerous groups and not from what are perceived to be dangerous beliefs.

Yet the trope of the dangerous cult continues to influence the actions of law enforcement and government officials. The Church of Scientology has experienced what can only be described as ongoing persecution in Germany. Thanks to the marriage of anticult groups to state power, France has launched four times as many raids as any other country studied—57 in France as compared to 14 in the United States—according to Wright and Palmer’s calculations. Chinese police routinely raid and arrest members of Christian house churches. Most notorious is the Chinese crackdown on the qigong group Falun Gong, with reports of arrests, detentions, torture, and organ-selling deemed credible.

In the United States, the tradition of religious freedom has acted as a brake on government actions against new religions. There are notable exceptions, however. In 1953, the Arizona National Guard raided a polygamist community in Short Creek and abducted more than 250 children. The 1984 attack at Island Pond, Vermont saw 99 state troopers, accompanied by social workers, snatch 112 children of members of the Twelve Tribes. Within hours, a judge ordered the immediate return of the children to their parents, citing lack of evidence on claims of child abuse—members of the Twelve Tribes spank their children.

In 2008, allegations of child abuse led Texas law enforcement authorities to raid the Yearning for Zion community of Fundamentalist Mormons near Eldorado, Texas. On that occasion 439 children were taken into state custody, the largest such detention of children in US history. As in Vermont two decades earlier, a Texas court ordered the return of the children, finding that their removal was not warranted.

In a post-9/11 world, most Americans seem willing to accept state-sanctioned actions against religions perceived as deviant or dangerous. This is already the case abroad. In Russia, Jehovah’s Witnesses are targeted; in India, Christians; in Iran, Bahai’s; in Myanmar, Muslims; in Eritrea, Pentecostals.

How do we deal with legitimate concerns about national security, child endangerment, and criminal activity in a democratic society, and at the same time protect constitutional rights to freedom of conscience and religion? In many respects this question has already been answered, as shown by the upsurge in government raids on religious groups around the world. Yet we would hope to learn from the past.

Today we could take a page from Janet Reno’s notebook and from the institutional memory of FBI agents involved in the Branch Davidian raid who now consider it a mistake. Although Reno defended the decision to use CS gas at the time, she did reflect upon it when she left office in 2000: “We’ll never know whether it was a mistake or not… But knowing now what I do, I would not do it again. I would try to figure another way.”

Featured image credit: The Church of Scientology “Big Blue” building in Los Angeles, California. CC-BY-SA-3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Raiding religion, the new normal appeared first on OUPblog.

April 18, 2017

Heligoland, 18 April 1947; how Britain carried out one of the biggest non-nuclear detonations

The following is an extract from Heligoland, Britain, Germany, and the Struggle for the North Sea by Jan Rüger. Today marks the 70th year anniversary of when British forces set off one of the largest non-nulcear detonations in history, on Heligoland in Germany.

‘Blow the bloody place up.’ There was nothing ambiguous about the instructions which Commander F. T. Woosnam had been given. Woosnam was the naval engineer in charge of preparing Heligoland for Operation ‘Big Bang’, the destruction of all Germany’s military installations on the small island. Sir Harold Walker, the commander of Britain’s naval forces in Germany, was sure that it would be ‘by far the biggest demolition ever carried out by the Royal Navy.’

Preparations began in August 1946 when the first British officers returned to Heligoland since its evacuation a year earlier. They had, Woosnam wrote, ‘little idea of how to tackle such a unique task.’ Experts from the UK were flown in to conduct tests. After extensive trials they decided to connect all the British and leftover German explosives through one gigantic network of wires. Led by Woosnam’s team, 120 German technicians and labourers worked on the project for eight months. By April 1947 they had wired up more than 6,700 tons of explosives, ready to be detonated simultaneously.

Operation ‘Big Bang’ was meant to solve a number of problems. A seemingly endless amount of ammunition and shells had been stored on the island, much of it now hidden under piles of debris. Demilitarizing the island involved technical problems that were ‘without precedent’, wrote the secretary of the Admiralty. Blowing the whole place up seemed by far the easiest solution. Yet symbolic considerations were just as important. The island’s demilitarization was not to be a cumbersome process involving international commissions and protracted negotiations with the Germans. That had been the approach after the First World War, when Balfour had explicitly dismissed plans to blow up Heligoland. Not so now, after another war in which the Germans had shown even greater military potential and expansionist ambition than in 1914. Their threat to Britain had to come to a conclusive end, once and for all. The very command—‘Blow the bloody place up’—seemed to carry the weight of generations of Anglo-German conflict, to be settled now in one symbolic act: ‘No more Heligolands.’

Map of Map of Heligoland, Germany, 1910 by The University of Texas at Austin. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Map of Map of Heligoland, Germany, 1910 by The University of Texas at Austin. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.To drive the point home, the navy made an unprecedented public spectacle of the operation. Charles Gardener, the BBC’s veteran war reporter, was given his own plane for a running radio commentary. A special transmitter was brought in to allow for live broadcasts. The Royal Navy’s headquarters in Berlin made sure that the press would be given a chance to take ‘before and after’ pictures of the island. Automatic cameras were set up on Sandy Island to capture the blast and the tidal wave caused by it. The vessel chosen for the reporters and cameramen was HMS Dunkirk, a detail that was not lost on British newspapers celebrating the operation as a thinly disguised act of vengeance. Britain’s top military brass in occupied Germany was keen to attend. ‘There is nothing I would like to do better’, wrote Air Marshal Sir Philip Wigglesworth. He had a tight schedule, but would make sure to ‘fly round at some safe distance and watch the upheaval from a Dakota’ together with General Sir Richard McCreery, the commander-in-chief of the British Army of the Rhine.

There were critics in Britain who objected to the planned detonation, billed as the biggest non-nuclear explosion in history…. but none of them washed with the British government. This was occupied territory, uninhabited and unsafe. The object of its demolition, the navy explained in a press release, ‘is not to destroy the island, but to dispose of the extensive fortifications, which have made Heligoland one of the most heavily defended places in the world.’

On 18 April 1947, on the fourth pip of the BBC’s 1 o’clock time signal, E. C. Jellis, Woosnam’s deputy, pressed the button. After a bright flash, pillars of debris and dust rose up ‘in almost frightening splendour’, as one reporter had it. The giant mushroom cloud reminded observers of a nuclear explosion. The shockwave was felt on the mainland, 70 km away.

The British press was jubilant. ‘Biggest Bang since Bikini’, ‘A very reasonable way of celebrating Hitler’s birthday’ (which was on 20 April), ‘Hitler’s pride and joy, heavily fortified Heligoland, enveloped in mass of flames’ were typical headlines… German reactions were predictably less enthusiastic. Most reports focused on the fact that the island seemed still intact. ‘Der rote Felsen steht noch’(‘the red cliffs are still standing’), ran one front-page headline—however many explosives the British threw at them, the cliffs would withstand them. The expectations of the Allies, one commentator wrote, had been bitterly disappointed. Heligoland was like the rest of Germany. It remained what it had been, ‘outwardly harmed and scarred by the visible marks of the detonations, but still in its erstwhile greatness and beauty.’

The narrative, adopted in countless articles and pamphlets that were to follow, was that the British had tried to eliminate the island. Yet the island had defied them…. The response to the demolition showed a marked willingness amongst Germans to portray themselves as victims…. Even if many Germans addressed the link between their own roles during the war and the destruction of Germany privately, this was rarely discussed in public. In most of the press, responsibility for the past remained dissociated from suffering in the present. Heligoland was part of a wider discourse which spoke eloquently about the ordeals of Germans and remained silent about the ordeals of others. The island was depicted as emblematic of the Heimat which so many Germans had lost: a small, peaceful community that had suffered a series of sudden, devastating blows towards the end of the war.

Featured image credit: Heliogland Deune by Louis-F. Stahl. CC BY-SA 3.0 DE via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Heligoland, 18 April 1947; how Britain carried out one of the biggest non-nuclear detonations appeared first on OUPblog.

Where did Darwin go on the Beagle?

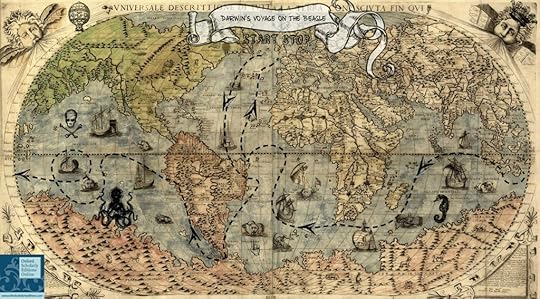

On 27 December 1831, Charles Darwin set off on a round-the-world survey expedition and adventure on the HMS Beagle. Captained by Robert FitzRoy, the trip (the second voyage of HMS Beagle) lasted until 2 October 1836 and saw the crew visit locations as varied as Brazil, Tierra del Fuego, South Africa, New Zealand, and the Azores. Aged just 22, Darwin was a young and promising naturalist, who dreamed of seeing wondrous tropical lands before heading home and joining the church. In his own words, Darwin’s notions of the inside of a ship “were about as indefinite as those of some men on the inside of a man, viz. a large cavity containing air, water, and food mingled in hopeless confusion.” By the time he returned to England however, he was a changed man; hardened to life on water as well as explorations on land, and celebrated as a pre-eminent geologist, naturalist, and fossil collector.

Darwin’s journals were published as The Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle, winning him instant recognition. They contain a curious mix of personal anecdote, religious belief, racial typecasts, as well as historical and scientific enquiry on topics as diverse as geology, zoology, and anthropology. The diaries also demonstrate the inquisitive beginnings that formed Darwin’s famed theory of Natural Selection. Not only do they provide a fascinating insight into the man himself, but they also provide a day by day record of the ship’s route. We’ve highlighted some of Darwin’s most intriguing stops (including tropical rainforests, volcanoes, elephant rides, and Napoleon’s tomb) on the interactive map below. Explore this astounding circumnavigation for yourself, or read the full text of Darwin’s first year on the Beagle.

Featured and map image credit: “Map of the world from 1565,” by Paolo Forlani. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post Where did Darwin go on the Beagle? appeared first on OUPblog.

The international protection of diplomatic and consular agents

On Monday 19 December 2016, President Vladimir Putin had made plans to attend Woe from Wit, a satirical comedy on post-Napoleonic Moscow. The play is a classic in Russian literature. It was written in 1823, six years before its author – poet and diplomat Alexander Griboyedov – was murdered by a crowd of Islamic religious fanatics, when Ambassador to Persia. President Putin never made it to the theatre. Just minutes before leaving, he received a call by Turkish President Erdoğan. As an oddly morbid coincidence, Erdoğan conveyed the message that the Russian Ambassador had been assassinated in an art gallery in Ankara. The news made international headlines; the explosive image taken at the scene – featuring the gunman shouting ‘Do not forget Aleppo!’ moments after he pulled the trigger – has in the meantime been named 2017 World Press Photo of the Year.

The incident serves as a reminder that diplomatic and consular agents still face significant occupational hazards. Being representatives of their home state in a foreign country, envoys are placed in vulnerable positions. Consequently, international law protects those exposing life and health for the greater good of the international office. Obligations to protect foreign envoys are among the longest-standing rules of diplomatic and consular law. Upon codification in the 1961 Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations (VCDR) and the 1963 Vienna Convention on Consular Relations (VCCR), personal inviolability was deemed so well established in customary international law that negotiators barely discussed its scope or formulation. The Conventions comprise, on the one hand, a special positive duty of protection and, on the other, a negative duty to abstain from exercising any enforcement right, in particular an arrest or detention of foreign envoys (Articles 29 VCDR and 40-41 VCCR). The obligations apply to state representatives on duty (e.g. the 2012 killing of the US Ambassador in Benghazi), in a private capacity (e.g. the 2016 crime of passion involving the Greek Ambassador to Brazil, his wife, and her lover), and even when it is unsure whether any violence has occurred (e.g. the discovery, on Election Day, of the lifeless body of a Russian consular attaché in his country’s consulate in New York and the sudden death of the Russian Ambassador to the UN after he had fallen ill behind his desk in the same city in February 2017).

Inviolability is to be respected, in the first place, by the receiving state’s authorities. Any attack upon the person, freedom, or dignity of a diplomatic agent is prohibited, which implies that no arrest, abuse, or strip-search by armed forces or police officers can occur. As for consular officers, an arrest or detention pending trial is possible in case of a grave crime and pursuant to a decision by a competent judicial authority. But when can a crime of a state agent be attributed to his state? The 2016 Ankara and Brazil killings both feature a local police officer as the prime suspect; yet since both were off-duty and seemingly not acting under governmental instructions, their acts are likely be judged ultra vires. In cases where wrongful conduct is directly attributable, the diplomatic context calls for soft reparation measures rather than hard sanctions; think of a voluntary compensation or admission of guilt.

J. Christopher Stevens — United States ambassador to Libya from June 7, 2012 until killed in an attack on the US consulate in Benghazi, on September 12, 2012 by unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

J. Christopher Stevens — United States ambassador to Libya from June 7, 2012 until killed in an attack on the US consulate in Benghazi, on September 12, 2012 by unknown. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.When, in 2013 a Russian diplomat was detained for abusing his children in The Netherlands, then Foreign Minister Frans Timmermans publicly apologized to President Putin. Complicity or ill will on the part of a receiving state may be hard to prove. When a sending state perceives a provocation, it will thus commonly only communicate grievances through diplomatic instruments. In 2015, after American diplomats were drugged in a bar in Saint Petersburg, the US addressed its concerns in a note verbale. On the margins of this incident, the State Department’s spokeswoman also publicly reported the apparent increase of ‘harassment and surveillance of diplomatic personnel in Moscow by security personnel and traffic police’.

A receiving state should not just abstain from harmful conduct; it also has to take preventive measures. This entails, as confirmed in the 2008 ICJ Djibouti v France Judgement (§174), the protection of envoys from attacks by individuals. The Vienna Conventions indicate that the precise content of this obligation depends on local circumstances and existing threats. For a long time, preventive and punitive measures largely differed across the globe. Following a sharp rise in (politically motivated) violence against diplomats, however, states adopted the 1973 UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Crimes against Internationally Protected Persons, including Diplomatic Agents, which celebrates the 40th anniversary of its coming into force in 2017. In the Convention, an astonishing number of state parties (180) commit to criminalise attacks against the person or liberty of envoys (including murder and kidnapping), as well as the threat with, attempt to, or participation in such an attack. Moreover, states undertake to adapt internal laws to ensure jurisdiction and extradition.

The 1973 Convention supplements the Vienna Conventions, so that states have to abide by diplomatic and consular law when preventing or prosecuting violence against envoys. Firstly, this necessitates that local authorities respect the inviolability of premises in which they wish to take investigative measures (22(1) VCDR/31(1) VCCR), which is pertinent in the case of the sudden deaths of Russian envoys in New York. Secondly, in the scenario of one internationally protected person attacking another, the Vienna Conventions remain relevant because the perpetrator will continue to enjoy inviolability and immunities preventing an arrest or trial (Article 32 VCDR; see the exceptions for consular officers in Articles 41(1)/45 VCCR). In the referred-to Brazilian crime of passion, an arrest was nevertheless made: as a Brazilian national, the Ambassador’s wife is not entitled to immunities in her home state (Article 37 VCDR).

Recent episodes of violence confirm that diplomatic and consular agents experience all sorts of threats. Because the jeopardising of the safety of envoys creates a danger to the maintenance of normal international relations, the international community unrelentingly speaks out against it. States have, for good reasons, translated concerns in legal instruments that allow for coordination and harmonisation of measures targeting violence against those enjoying a special status under international law. Such efforts aim not only to protect individuals, but also the very functioning of diplomatic and consular regimes.

Featured image credit: Meeting Vladimir Putin with Recep Tayyip Erdogan 2017-03-10 by Kremlin.ru. CC-BY-4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The post The international protection of diplomatic and consular agents appeared first on OUPblog.

Political intermediation for just sustainabilities

Present understanding of the relationship between environmental conservation and social justice – the two of the greatest challenges of our times – is fraught with multiple confusions, especially in the context of developing countries. UN agency reports blame deforestation on poor people’s “inappropriate use of wood and other resources for cooking, heating, housing and crafts” while ignoring the massively wasteful lifestyles of the rich, including those living within the poor countries in the global South. On the other hand, recent scholarly research indigenous land rights to successful environmental outcomes. Yet, these studies offer little guidance as to why the effectiveness of indigenous land rights statutes vary significantly across different countries.

How do societies negotiate the apparently competing agendas of environmental protection and social justice? Why do some countries perform much better than others on this front? The answer lies in the political intermediation mechanisms, that is, well-established processes and relationships that help citizen groups, civil society organizations, and social movement participants engage in political and policy processes that affect them directly. Noticeably, in the context of questions of environmental conservation and social justice, the strength of political intermediation mechanisms matters more than the formal institutions of democracy, which are vulnerable to majoritarian politics.

Consider the case of India, which has been celebrated for the integrity of its democratic institutions. Despite their many accomplishments, the country’s post-independence leadership failed to bring about transformative change in the status of its minorities, specifically, its over 100 million indigenous people. The persistence of colonial-era political and economic institutions, including the total control of forestland in the hands of government forestry agencies, is a major barrier against the social, economic, and political development of the indigenous groups. The first few years of the new millennium witnessed nation-wide mobilization to demand forest and land rights, the election of a left-of-center federal government, and the establishment of a National Advisory Council (NAC). The NAC – a semi-autonomous agency that integrated civil society actors into policy making processes – was instrumental in the enactment of a number of progressive laws to protect the social, political, and economic rights of poor citizens.

The goals of environmental conservation and social justice are not at odds. Instead, to a large extent, the political economy of forest control and uses determines whether national forestry regimes are socially just and environmentally sustainable.

One of these laws was the Forest Rights Act (FRA) 2006, which gave legal protection of household land rights and community-level forest rights of indigenous and other forest-dependent groups. National and international conservation groups lauded the FRA as one of the best efforts globally to reconcile the goals of environmental conservation and social justice. Yet, the deeply entrenched nature of the status-quo that vests too much discretion in the hands of government forestry officials undermined the realization of statutory intention in practice. As a result, forest-dependent groups who have successfully protected and utilized forests sustainably, cannot hold the government forestry agencies to account. Yet, the poor continued to be blamed for forest degradation, while the ineffective and corrupt forestry agencies continue to receive a lion’s share of national and international funding devoted to nature conservation. A very similar story unfolds in Tanzania even though there are some important differences in the institutional structure of Tanzania’s national forestry administration, which offers better opportunities for improving the accountability of forestry and wildlife agencies.

Contrast the Indian experience to the state of affairs in Mexico, which is home to the world’s most successful community forestry policies and programs. Mexico’s success is often attributed to the post-revolutionary land redistribution between 1935 and late 1960s, yet, this book shows that these redistributions were a result of persistent social and political mobilization of the peasants and indigenous groups, and inter-elite competition for power within the ruling PRI (the Institutional Revolutionary Party). For instance, the redistribution of nearly 70 percent of Mexico’s forestland to agrarian and indigenous communities was a result of the effort of the government to compensate for the failure to distribute good quality irrigated land owned by politically influential groups. To be sure, for Mexico’s environmental elites, the distribution of forestland to peasants raised the specter of a complete decimation of the country’s forests. The federal forestry service sought to bring forests under “scientific management” that would combine conservation and sustainable harvesting by commercial loggers. However, unlike their counterparts in India and Tanzania, Mexico’s peasants were both mobilized and sufficiently well-connected to the ruling party to thwart the plans for the development of an exclusionary forestry regime.

Political scientists often find Mexico’s form of peasant corporatism wanting in comparison to the ideal-type liberal democratic institutions of policy-making. Yet, instead of being the oppressive anti-democratic arrangements they are often made out to be, party-sponsored peasant organizations became part of a broader mechanism of political intermediation that afforded the peasant and indigenous groups significant leverage in the political and policy processes. As a result, in comparison to other countries, forestland rights of Mexico’s forest-dependent people are very secure – both in law and practice. Moreover, the well-established links between peasant groups, party machine, and the state agencies have made Mexico’s policy-making far more responsive and the forestry and wildlife agencies more accountable compared to their counterparts in India and Tanzania.

The available evidence that Mexico’s inclusionary forestland regime is far more effective than are India and Tanzania’s exclusionary forest policies at achieving nature conservation. The goals of environmental conservation and social justice are not at odds. Instead, to a large extent, the political economy of forest control and uses determines whether national forestry regimes are socially just and environmentally sustainable. International agencies and middle-class donors of environmental charities have an opportunity to ensure that conservation investments are redirected, from countries that fail to hold their government agencies to account, to the countries that have put in place effective institutional arrangements that promote accountability and share the benefits of forest conservation with forest-dependent groups.

Featured image credit: Landscapes San Miguel De Allende Mexico by marcoreyesgt. CC0 Public Domain via Pixabay.

The post Political intermediation for just sustainabilities appeared first on OUPblog.

April 17, 2017

How well do you know the Hollywood Western? [quiz]

In Hollywood Aesthetic: Pleasure in American Cinema, film studies professor Todd Berliner explains how Hollywood delivers aesthetic pleasure to mass audiences. The following quiz is based on information found in chapter 12, “Complexity and Experimentation in the Western.” The chapter explains the aesthetic value of increased complexity in genre filmmaking by examining filmmakers’ efforts to continually complicate the figure of the Western hero. It studies the appeal, for Western cinephiles, of Hollywood’s most complex Westerns of the studio era. It also demonstrates how more recent filmmakers have kept the Western alive by revitalizing outdated conventions and mining new material from the genre.

Quiz image: Wild West Show at High Chaparral. Photo by High Chaparral Sweden. CC-BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Featured image: “Warner Brothers television westerns stars 1959” Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The post How well do you know the Hollywood Western? [quiz] appeared first on OUPblog.

Is epigenomics the next breakthrough in precision medicine?

In the past few decades, the field of genomics has rapidly evolved. From the Human Genome Project to the Million Genomes Project, molecular insight into our own DNA has never been more attainable. These new insights can let us know when we might have cancer-causing alterations in our genes. Personal genomics tests may promise to integrate our unique genetic makeup into clinical decision making. However, there is more to our genome than what such tests can reveal. In addition to the DNA code, there is a hidden layer of regulation controlling the activity of genes. Have you thought about why identical twins can still be different? How it is possible that the lifestyle of our grandparents can affect our lives today? The hidden layer responsible for fine-tuning alongside our DNA is called epigenetics.

Epigenetics makes sense of chemical modifications that influence gene expression without altering the DNA sequence. In fact, our own cells use epigenetic chemical regulators to control gene activity. For example, environmental influences such as nutrition or cigarette smoke, as well as our own hormones, can have a strong epigenetic impact on how active our genes are.

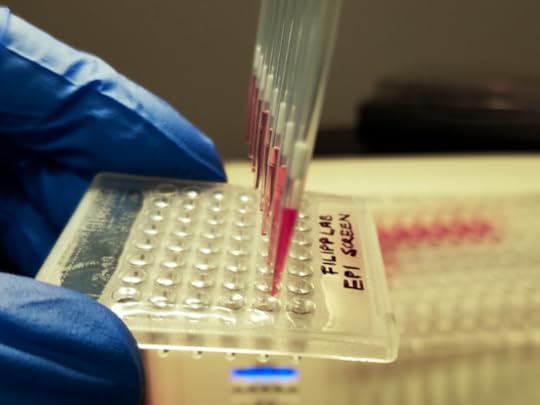

Epigenomics, an approach to studying epigenetic effects, thus holds a lot of promise for cancer treatments. However, there are a number of questions that need to be answered first. We need to understand how the epigenome of a healthy person looks, and if it changes as we age. From there, we can see how the epigenome of a sick person might differ. In the future, these important questions will be addressed by personalized epigenomics, which tries to extract information out of a comprehensive picture of a person’s epigenome.

“There is a hidden layer of regulation controlling the activity of genes”

You may ask: why can we not create a simple test that tells us if we have good genes but an unfavorable epigenome? Our epigenome is highly dynamic. Recently, the systems biology and cancer metabolism lab at UC Merced published discoveries about an epigenetic factor called “Jumonji”. This factor can affect how an entire network of cancer genes behaves, and takes on the role of a cancer gene to bring uncontrollable cell growth. Epigenomic regulators, including Jumonji, remove or add chemical marks allowing for transient gene read-outs while blocking it in the next minute. If such important regulators are mistuned and do not put the right marks on their target genes, altered metabolism triggers unlimited cellular growth and cancer can arise.

Is it too early for consumers to think about personalized tests? Is the information still too cryptic or too unreliable to draw conclusions?

High-throughput screening in combination with systems biology analysis identifies epigenomic master regulators in malignant melanoma. Photo by Systems Biology and Cancer Metabolism Laboratory, Fabian V. Filipp. Used with permission. CC BY-NC-SA.

High-throughput screening in combination with systems biology analysis identifies epigenomic master regulators in malignant melanoma. Photo by Systems Biology and Cancer Metabolism Laboratory, Fabian V. Filipp. Used with permission. CC BY-NC-SA.Personal gene tests for cancer exist but often do not take epigenetic factors into account. Actor Ben Stiller claims a simple genetic test for abnormally high levels of the prostate antigen saved his life. Abnormally high levels of the prostate specific antigen (PSA) in the blood can mean that a man has prostate cancer, but not always. This has led to substantial overdiagnosis of prostate tumors in the past and has resulted in much debate about whether PSA screenings are recommended.

Drugs that target the epigenome raise optimism as a viable direction of clinical research. It remains open to debate, however, whether epigenetics is a beneficial force since epigenetics was found in some cases to actually assist the cancer cells in manipulating the immune system and to evade the drug targeting approaches. Researchers have compared this delicate epigenetic homeostasis to Yin and Yang. Complementary forces keep each other in check but if one force overtakes the system, it is out of equilibrium. For the cells, this can mean unlimited growth, cancer, or death. The goal in precision medicine then, is to acquire a thorough understanding of epigenetic regulation so that drugs can be designed to counter-regulate these factors.

As seen in recent breakthroughs in melanoma research, a genetic mutation of an epigenetic player allowed for a drug to be created to stop the ability of cancer cells to hide from the immune system thus making the tumor vulnerable. For cancer patients with epigenetic activation, epigenetic drugs promise hope.

Featured image credit: Precision targeting and big data in cancer medicine. High-throughput screen of malignant melanoma cells using genomics, epigenomics, and metabolomics. Image by Systems Biology and Cancer Metabolism Laboratory, Fabian V. Filipp. Used with permission. CC BY-NC-SA.

The post Is epigenomics the next breakthrough in precision medicine? appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers